This article was downloaded by: [Uniwersytet Warszawski]

On: 22 January 2014, At: 05:18

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Medieval History

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rmed20

Scandinavians swearing oaths in

tenth-century Russia: Pagans and

Christians

Martina Stein-Wilkeshuis

a

a

Walstraat 91, 7411GK Deventer, The Netherlands

Published online: 03 Jan 2012.

To cite this article: Martina Stein-Wilkeshuis (2002) Scandinavians swearing oaths in tenth-

century Russia: Pagans and Christians, Journal of Medieval History, 28:2, 155-168, DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4181(02)00003-9

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information

(the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor

& Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties

whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and

views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The

accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently

verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable

for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages,

and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in

connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

www.elsevier.com/locate/jmedhist

Scandinavians swearing oaths in tenth-century

Russia: Pagans and Christians

Martina Stein-Wilkeshuis

Walstraat 91, 7411GK Deventer, The Netherlands

Abstract

The Old Russian Primary Chronicle reports on four tenth-century treaties concluded on oath

between unchristianised merchants coming from Scandinavia and the Greek emperor, describ-

ing the oaths and ceremonies, the objects used, and the gods invoked. This article presents an

investigation into the oaths and the formalities performed on those occasions. The opportunity

is given for a comparison with fragmentary data elsewhere in the Scandinavian area of the

time, and for a clarification of the portrayal of the oath in its pre-Christian form. As the

agreements were concluded on the eve of Russian’s official Christianisation, interesting

encounters between pagans and Christians are signalised.

2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All

rights reserved.

Keywords: Scandinavia; Rus; Byzantium; Oath-taking; Trade

In times when Western Europe suffered from Viking raids, and indeed before that

period, journeys from the North were undertaken by boat along the Russian rivers

Lovat, Volkhov, Volga and Dnieper. Colourful groups of professional or occasional

merchants with their wares of hides, amber, weapons and slaves, and also political

refugees, outlaws and adventurers, travelled in a southerly direction to try their luck

by trading and robbing. Some went as far as Constantinople (Old Norse Miklagar

ðr,

the Great City), and the Arab world.

1

They were unbaptised and their name was

E-mail address: steinwil@xs4all.nl (M. Stein-Wilkeshuis).

1

For the early history of Rus, see Simon Franklin and Jonathan Shepard, The emergence of Rus 750–

1200 (New York, 1996), part I; on early trading relations: P. Sawyer, ‘Ottar og vikingetidens handel’,

Ottar og Wulfstan, to rejsebeskrivelser fra vikingetiden (Roskilde, 1983); J. Callmer, ‘Verbindungen zwi-

schen Ostskandinavien, Finnland und dem Baltikum vor der Wikingerzeit und das Rus-Problem’, Jahr-

bu¨cher fu¨r Geschichte Osteuropas, 34 (1986), 357–62; S.H. Cross, ‘The Scandinavian infiltration into

early Russia’ Speculum, 21 (1946), 505–15.

0304-4181/02/$ - see front matter

2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 3 0 4 - 4 1 8 1 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 0 0 3 - 9

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

156

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

Rus. Runic inscriptions, evidence from the Codex Bertiniani,

2

De administrando

imperio,

3

and Arab travel reports, leave no room for doubt that the majority of the

travellers were Scandinavians, coming from Sweden for the greater part. Staraja

Ladoga, Novgorod, Gorodishche near Lake Ilmen, Smolensk, and Kiev among

others, were set up as trading posts that developed into political centres in the course

of time. Archaeological research has shown the Scandinavian origin of numerous

objects and building structures.

4

Results of onomastic investigation into the names

of merchants and envoys involved in the negotiations for treaties with the Greek,

and the geographical names of several Dnieper falls point in the same direction.

5

In

addition, prescriptions were incorporated in two of four treaties under discussion in

this article, for settling disputes between the merchants among themselves and

between Rus and Greek. Conclusive evidence was found that the legal system with

articles on the procedure, killing, injuries and theft was closely akin to Scandinav-

ian law.

6

Their journeys brought the Rus into contact with many tribes, and their friendly

and other relations with the Greeks are of special interest. In the course of the tenth-

century four treaties between Rus and the Byzantine emperors were concluded and

confirmed on oath, the texts of which have survived. The oaths, the people involved

and the accompanying ceremony form the focus of this article. Thereby a double

aim is served; first, to give a clearer insight into contemporary oath ceremonies

elsewhere in North-west Europe, and, secondly, to observe relations between pagans

and Christians when swearing. So far, no special study has been devoted to the

subject.

1. The oath, its function and development

The early oath was a ritual guarantee of someone’s own words, by way of a

conditional self-curse, entrusted to an object invoked solemnly. Originally natural

2

The Annals of St Bertin, trans. J. Nelson (Manchester and New York, 1991), 44.

3

Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De administrando imperio, ed. and tr. Gy Moravcsik and R.J.H. Jenkins

(Washington D.C., 1967), 57f.

4

B. Malmer, ‘What does coinage tell us about Scandinavian society in the late Viking age?’ From

the Baltic to the Black Sea. Studies in medieval archaeology, ed. D. Austin and L. Alcock (London,

1990), 157–67; The archaeology of Novgorod, Russia. Recent results from the town and its hinterland,

The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph Series 13, ed. M.A. Brisbane (Lincoln, 1992);

J.Callmer, ‘The archaeology of Kiev’, Les pays du Nord et Byzance (Actes du colloque nordique et

international de byzantinologie tenue a` Upsal 20–22 avril 1979, Uppsala, 1981); I. Jansson and E.N.

Nosov, ‘La route de l’Est’, Les Vikings. Les Scandinaves et l’Europe 800–1200 (Paris, 1992), 74–83.

5

V.P.L.Thomsen, The relations between ancient Russia and Scandinavia and the origin of the Russian

state (Oxford, 1965), Lectures 2 and 3, and Appendix.

6

M.W. Stein-Wilkeshuis, ‘A Viking-age treaty between Constantinople and northern merchants, with

its provisions on theft and robbery’, Scando-Slavica, 37 (1991), 35–47; idem, ‘Legal prescriptions on

manslaughter and injury in a Viking-age treaty between Constantinople and northern merchants’, Scandi-

navian Journal of History, 19 (1994), 1–16; idem, ‘Scandinavian waw in a Rus–Greek Commercial Trea-

ty?’, in: The community, the family and the saint. Patterns of power in early medieval Europe, ed. J. Hill

and M. Swan (Turnhout, 1998), 311–22.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

157

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

elements like a stone or a stream were called forth, as also a ship or weapons, the

latter being the favourite in the Germanic area. Perjury was believed to provoke the

gods’ vengeance. For the perjurer it meant the loss of, or a decrease in, personal

rights.

Under the influence of Christianity, pagan formulae were eliminated, and the oath

by God and the Saints, was sworn on the Cross, the Gospel or the relics. Although

with perjury an indirect revenge by the power invoked remained possible, violation

of one’s oath was gradually considered a sin. We find the Christian oath in medieval

West European documents, with few traces, or none at all, left of its pre-Christian

past. Contemporary Scandinavians however, including also Icelanders, being late

converts and relatively early writers, preserve some evidence of the early culture.

In medieval Scandinavia, as in all Germanic societies, oaths formed an important

element of the legal system. Well known was the oath of denial, sworn by the defend-

ant, often with the help of so-called oath-helpers. An oath of reconciliation was

sworn at the end of disputes and feuds, and by the oath of equality the receiver of

a compensation for an injury promised to be satisfied with a compensation too

(instead of taking revenge), if ever in similar circumstances as his opponent. Entering

into contracts was always accompanied by taking an oath.

Tenth-century Byzantium also knew the oath: it was sworn on an ‘oath-book’, or

to the Holy Sepulchre. The eighth-century emperor, Leo IV, for instance, demanded

that military commanders, citizens and craftsmen swore a so-called collective oath

on the Cross and signed the documents. Next, the people had to proceed to the

church of St Sophia and put the documents on the altar.

7

.

2. Sources

The main source for this investigation is the Russian Povest’ vremennykh let, or

Tales of past times. The chronicle, a late eleventh or early twelfth-century record of

Russia’s earliest history, is known under the title Primary Chronicle.

.8

The name

Nestor Chronicle is also used, after the monk Nestor who, according to legend,

would have composed it in the Kievan Cave monastery. It was transmitted in two

fourteenth- and fifteenth-century manuscripts in the Church Slavonic language. This

rich and colourful source has in many ways proved to be remarkably reliable.

9

In

the chronicle the texts of the treaties concluded between Rus and Greek in 907, 911,

944 (probably) and 971 respectively, have been included. Generally, scholars who

7

Lexikon des Mittelalters (Mu¨nchen und Zu¨rich, 1980–99), article ‘Eid’; J. de Vries, Altgermanische

Religionsgeschichte (Berlin, 1956–7), 300–4; Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (Berlin,

1989), IV, 537–42; K. von Amira and K.A. Eckhardt, Germanisches Recht (Berlin, 1960), II, chap. VII.

8

Povest’ vremennykh let, ed. D. C

ˇ izˇevskij (Tschizˇewskij) under the title Die Nestorchronik

(Slavistische Studienbu¨cher 6, Wiesbaden, 1969); the chronicle has been translated into many modern

European languages. For this article use was made of The Russian primary chronicle. Laurentian text,

tr. S.H. Cross and O.P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor (Cambridge, MA, 1953), henceforward known as PC.

9

Franklin and Shepard, Emergence of Rus, XVII–XXI.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

158

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

have studied different aspects of the treaties, do not seriously doubt their credibility.

Page, for instance, points out that the treaties, when including provisions on criminal

law, shipping law and slave trade are closely akin to an agreement concluded by

King Alfred and the Danish King Guthrum, probably after 886, and another one of

991 by King Æthelred and the Viking army. And Franklin and Shepard remark:

‘There is no serious doubt that they derive from actual charters or treaties, even if

the editors of the chronicle omitted or embellished passages. The dates provided for

the documents are very plausible’.

10

Our knowledge of the early oath within the North European area is based on a

handful of sources. Most Scandinavian legal articles were written down in the twelfth

or thirteenth century and betray Christian influences,

11

the oath being sworn on the

Holy Cross, the Gospel or the relics, and God being invoked as a witness to the

oath. This material therefore, does not generally serve our purpose. Only the Old

Icelandic lawbook Gra´ga´s,

12

and probably also the Swedish A

¨ ldre Va¨stgo¨talagen,

13

preserve a few formulae used with oath ceremonies that seem to have stood the

ravages of time.

Medieval Frisian law, also, devotes attention to patching up quarrels by way of

an oath and preserves some ancient formulae.

14

Two historical events have been

included in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: on the edge of the Scandinavian world King

Alfred and plundering Vikings concluded two peace treaties that were confirmed

on oath.

15

With Old Icelandic literary sources the investigator sets foot on historically less

reliable ground, as the events described often had experienced a lengthy oral trans-

mission. Thereby, it is not always possible to determine their authenticity with cer-

tainty. This applies to Landna´mabo´k, or Book of Settlements, a record of Iceland’s

discovery. One of its redactions relates the introduction of the first laws in the new

country around the year 930, the so-called U

´ lfljo´ts law, with instructions for taking

10

R. I. Page, Chronicles of the Vikings. Records, memorials and myths (London, 1995), 98; Franklin

and Shepard, Emergence of Rus, 103; I. Sorlin, ‘Les traite´s de Byzance avec la Russie au Xe sie`cle’,

Cahiers du Monde Russie et Sovie´tique II (1961), 313–60 and 447–75; M. Hellmann, ‘Die Handelsvertra¨ge

des 10. Jahrhunderts zwischen Kiev und Byzanz’, Untersuchungen zu Handel und Verkehr der Vor- und

Fru¨hgeschichtlichen Zeit in Mittel- und Nordeuropa IV, Der Handel der Karolingen und Wikingerzeit,

ed. K. Du¨wel, H. Jahnkuhn, H. Siems and D. Timpe, Abhandlungen der Akademie von Wissenschaften

in Go¨ttingen, Philologisch-historische Klasse, 3. Folge, 156 (Go¨ttingen, 1987) 643–66; S. Mikucki,

‘Etudes sur la diplomatique Russe la plus ancienne’, Acade´mie polonaise des sciences et des lettres

(Cracovie, 1953); J. Malingoudi, Die Russisch–Byzantinischen Vertra¨ge des 10. Jahrhunderts aus diplo-

matischer Sicht (Thessaloniki, 1994).

11

‘Edsformular’, ‘Rettergang’, Kulturhistorisk Leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder (København, 1980),

vol. 3 and 14.

12

Gra´ga´s Konungsbo´k and Gra´ga´s Sta

ðarho´lsbo´k ed. V. Finsen (København, 1852 and 1879); Laws

of early Iceland I, tr. A. Dennis, P. Foote and R. Perkins (Winnipeg, 1980).

13

A

¨ ldre Va¨stgo¨talagen, ed. C.J. Schlyter, Sammling af Sweriges gamla Lagar I (Stockholm, 1827),

1–74.

14

Altfriesische Rechtsquellen. Texte und U

¨ bersetzungen, ed. and tr. W. J. Buma and W. Ebel (Go¨ttingen,

1963–77), II.

15

Two (of the) Saxon Chronicles I, ed. J. Earle and C. Plummer (Oxford, 1892), 74.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

159

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

an oath. This uncertainty also concerns the Icelandic sagas,

16

family histories of

people who settled in Iceland, and their descendants. Several oath ceremonies have

been included herein. Finally, the Old Icelandic poetic Edda, a collection of poems,

many of which have a mythological character, is an important source of information

on early Scandinavian religious belief and way of thinking. Its pre-Christian origin

has been established with more certainty, but still the Edda must be used with some

caution. It has several descriptions of oaths.

17

3. The Rus swear oaths

We take up the thread with the Rus on their hazardous travels, and the four treaties

they concluded with the Greeks. The first agreement was confirmed in 907 between

Oleg, Prince of Rus, with five delegates on one side, and the Emperors Leo VI and

Alexander on the other. Probably it was concluded after an attack by the northerners

on Constantinople, which was bought off by payment of a tribute.

18

The text is in

a fragmentary form and the treaty is supposed to be preliminary to the fuller text

of the next agreement (911). Practical arrangements were laid down for the Rus

accommodation and maintenance in Constantinople. They had to live in St Mamas,

outside the city walls. Rus, coming as merchants, were to receive supplies for 6

months, including bread, wine, meat, fish and fruit, and baths would be prepared for

them. For their return home they would receive food, anchors, cordage and sails.

They were allowed to do business without paying taxes. Rus arriving without mer-

chandise had to have their names written down, and enter the city through one gate

only, unarmed and fifty at a time, escorted by an imperial officer. The treaty was

confirmed on oath:

19

Thus the Emperors Leo and Alexander made peace with Oleg, and after agreeing

upon the tribute and mutually binding themselves by oath, they kissed the cross,

and invited Oleg and his men to swear an oath likewise. According to the religion

of the Russes, the latter swore by their weapons and by their god Perun, as well

as by Volos, the god of cattle, and thus confirmed the treaty.

20

The next treaty was concluded in 911 between Oleg, Prince of Rus, with 15 del-

egates, among them the five men of the previous treaty, and the Emperors Leo,

Alexander and Constantine. The agreement is a confirmation of the previous one,

with the same practical arrangements. This time, rules of procedure were added,

16

Icelandic sagas are from the series Islendinga so¨gur (henceforward IS), 12 vols., ed. Gu

ðni Jo´nsson

(Reykjavı´k, 1953).

17

Edda, die Lieder des Codex Regius nebst verwandten Denkma¨lern, ed. G.Neckel (Heidelberg, 1927).

18

On the reason for the 907 agreement, and its record in the PC, see G. Ostrogorsky, ‘L’expe´dition

du Prince Oleg contre Constantinople en 907’, Annales d’Institut Kondakov XI (1939), 47–62.

19

The Old Russian text normally uses rota for oath and has twice the more modern kljatva.

20

PC, 65.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

160

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

compensations to be paid to victims of injuries and of theft, and prescriptions on

when and how revenge was to be taken. Regulations for runaway slaves and for

cases of shipwreck were also included. A ceremonial oath was taken on the confir-

mation, and the Rus declared:

Our serenity, (…) deemed it proper to publish and confirm this amity not merely

in words but also in writing and under a firm oath sworn upon our weapons

according to our religion and our law. (…) to maintain as irrevocable and immu-

table henceforth and forever the amity thus proclaimed by our agreement with

you Greeks and ratified by signature and oath.

21

In the meantime, journeys along the river Dnieper in a southerly direction became

more frequent. Archaeological investigations demonstrated that the Kievan quarter

Podol, which means ‘in the valley’, close to the river was probably the spot where

many Rus settled. Rich chamber-graves near neighbouring settlements witness to a

dominant upper layer in society, and a prosperous commercial development,

presenting the picture of a kind of military-political structure in the area. Kiev had

a heterogenous population consisting of Slavs, Khazars and Rus and since around

930 it was Igor, Prince of Rus, reportedly of Oleg’s kin, who ruled it as a president

with the consultation of the people.

It was under his leadership that the Rus attacked Constantinople in 941. But they

were frightened by Greek fire and, supposing that the Greeks had in their possession

the lightning from heaven, retired. A delegation consisting of 50 persons set out for

Constantinople and started negotiations with the Greek emperors. Conditions for a

new agreement were laid on the table. This treaty too, was to be confirmed on oath,

and the preliminary negotiations emphasised the establishing of bonds of friendship

‘henceforth and forever, as long as the sun shines and the world stands fixed’. A

Christian violator was to be cursed by God ‘forevermore’, and the unbaptised Rus

‘be killed with his own weapons and not be protected by God or Perun’.

22

Although the treaty claims to be a continuation of the 911 agreement, several

developments, most of them explicable as adaptations to altered circumstances, are

demonstrable. Different from its predecessor, the new treaty focuses on slave trade,

and the legal prescriptions, though still related to Scandinavian law, are less detailed,

conditions for customs and the purchase of silk are not as favourable as they were

before, and a restriction of access to the city and of accomodation facilities may

reflect the fear of new surprise attacks; in addition the emperor distances himself

from Rus law, postulating that Greek subjects be submitted to imperial law only.

The Rus promised that the Christians among them would go to the church of St

Elias and swear upon the Holy Cross and upon the parchment.

21

PC, 66.

22

PC, 74.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

161

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

The unbaptised Russes shall lay down their shields, their naked swords, their

armlets,

23

and their other weapons, and shall swear to all that is inscribed upon

this parchment, to be faithfully observed forever by Igor and his boyars, and all

the people from the land of Rus. If any of the princes or any Russian subject,

whether Christian or non-Christian, violates the terms of this instrument, he shall

merit death by his own weapons, and be accursed of God and of Perun because

he violated this oath. So be it good that the Great Prince Igor shall rightly maintain

these friendly relations that they may never be interrupted, as long as the sun

shines and the world endures henceforth and forevermore.

24

The emissaries of Rus returned with the imperial delegates declaring that the

emperor would be pleased to maintain peace, and receive the oath of Igor and his

followers, in exchange for his pledge.

In the morning, Igor summoned the envoys, and went to a hill on which there

was a statue of Perun. The Russes laid down their weapons, their shields and

their gold ornaments, and Igor and his people took oath (at least such as were

pagans), while the Christian Russes took oath in the church of St Elias, which is

above the creek, in the vicinity of the Pasy¨ncha square and the quarter of the

Khazars. This was, in fact, a parish church, since many of the Varangians were

Christians.

25

After the regency of his mother Princess Olga, Sviatoslav, son of Igor, took over

the government in Kiev. His excentric appearance and behaviour drew the attention

of several chroniclers. He rejected Christianity, his mother’s faith, and stayed a con-

firmed devotee of paganism. At the end of the 960s he led a campaign against the

Bulgars on the river Danube. His main object was the creation of a more convenient

shipping-route to the Black Sea along this river, since the river Dnieper with its falls

and predatory Pechenegs posed many obstacles. Thereby his troops invaded Byzan-

tine territory, and came to blows with Tzimiskes’ soldiers. In spite of the emperor’s

superior strength, Sviatoslav succeeded in concluding a treaty on reasonably favour-

able conditions regarding commerce and safe conduct. It was concluded at Dristra

in 971, and confirmed on a ceremonial oath. The PC reports:

I, Svyatoslav (…) confirm by oath upon this covenant that I desire to preserve

peace and perfect amity with each of the great emperors, (…) until the end of

the world.(…) But if we fail in the observance of any of the aforesaid stipulations,

(…) may we be accursed of the god in whom we believe, namely, of Perun and

Volos, the god of flocks, and we become yellow as gold, and be slain with our

23

H.G.Lunt, Concise dictionary of Old Russian (11th–17th centuries) translates ‘obru¨cˇ’ as ‘armlet, part

of a military equipment’.

24

PC, 74.

25

PC, 77.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

162

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

own weapons. Regard as truth what we have now covenanted (…), as it is

inscribed upon this parchment and sealed with our seals.

26

4. Summary and interpretation

On the basis of these descriptions a surprisingly detailed picture can be formed.

All four treaties were concluded in order to make, or confirm peace. An important

issue was the trading conditions that depended on the political position of the Rus.

In this respect, the 944 treaty, concluded after the unsuccessful attack on Constantin-

ople was less favourable than both previous agreements. Other issues were the juridi-

cal position of the merchants among themselves and towards the Greek (in 911, and

less detailed in 944), runaway slaves and shipping law.

At least three treaties appear to have existed in written form as well: ‘…not merely

in words, but also in writing’ (911) and ‘…upon this parchment’ (944 and 971). The

use of parchment, signature and seals seems to reach back to Byzantine initiative,

for the Rus at that time, though not illiterate, still carved runes.

The number of participants in the oath ceremony seems to have been larger on

the Rus than on the Greek side. In the company of the Prince of Rus, five, 15, and

50 persons showed up in 907, 911 and 944, respectively, and an unknown number

of ‘companions’ in 971, whereas the emperors do not seem to have been

accompanied by any fellow swearers. We may find here a reflection of administrative

structure, which in the northern area gave room to the people’s participation. Novgo-

rod and Kiev for instance, had their Veche, a gathering of townspeople with political

influence.

27

Another possible explanation for these large numbers of participants is

that collective oaths also featured in eighth-century Byzantium, as we saw, so that

there might be a question of Byzantine initiative: the emperors would have demanded

a large number of participants, in order to make the oath more binding. However,

the agreements concluded by King Alfred of Wessex with ‘the host’ were confirmed

by collective oaths too, so that we must be careful with conclusions in this respect.

With regard to the status of the members of the company of Rus, we assume that

in 907 and 911 most were merchants. The delegation of 944 consisted of 25 emissar-

ies for Igor himself, his wife and nephews and other prominent people, and 26 mer-

chants.

Regarding the participants’ religion, there seems to be an important Byzantine

influence. The 907 treaty puts the pagan Rus opposite the Christian Greek. The 911

text makes modest room for God among Rus (‘through God’s help’), whereas the

oath itself is sworn on the weapons ‘according to our religion and law’. The 944

treaty shows a remarkable mixture of paganism and Christianity, placing ‘baptised’

and ‘unbaptised’ Rus next to one another and stating that the number of baptised

26

PC, 89–90.

27

On the veche, see D.H. Kaiser and G. Marker, Reinterpreting Russian history. Readings 860–1860

(Oxford, 1994), especially ch. I.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

163

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

Rus was significant: ‘many of the Varangians were Christians’. The 971 treaty finally

seems to be a completely pagan affair as far as the Rus were concerned.

For the confirmation ceremony the unbaptised Rus proceeded to a place where

Perun was worshipped and where his statue stood. As a matter of fact, Perun, god

of weather, lightning and power, was worshipped by Slavs and Balts, but adopted by

Rus as the local equivalent of the Scandinavian god o´rr. According to archaeological

evidence Perun’s statue mentioned in the 944 text probably was on Starokievskaja

hill, near Kiev. For the year 980 the PC has an interesting description of Perun’s

looks: the statue was made of wood, had a silver head and golden moustaches, and

it stood there in all its glory in the company of other idols. A little south of the

present Novgorod, near a village called Peryn, the god Perun was worshipped too;

according to the third Novgorod chronicle his wooden statue was on a hill opposite

Gorodishche, overlooking the outflow of the river Volkhov from lake Ilmen. In 988,

after the official acceptance of Christianity it was cut down and thrown into the

river, and replaced by a church with the somewhat bizarre name Mary Nativity

of Peryn.

With the first three treaties it is stated that at the sanctuary weapons, shields, naked

swords, and in 944 also rings (armlets) and gold ornaments were put down when

the oath was sworn. The words ‘according to their religion’ suggest that putting

down these objects was a pagan custom. Taking an oath on weapons is known from

several Germanic tribes, and is also mentioned in the Edda on the edge of a shield

or the point of a sword.

28

Among the objects put down there were also rings. Scandinavians in a similar

situation elsewhere used them, as well. The first of the two short entries in the Anglo-

Saxon chronicle on the treaties between King Alfred and the Vikings states (876):

‘And afterwards the king made peace with the host, and they swore him oaths on

the sacred ring, which they had never done before for any people.’

29

The record of the Old Icelandic U

´ lfljo´t’s law, too, shows the use of a ring, the

so-called stallahringr:

A ring of two ounces or more should lie on the altar of every main temple. (…).

Every man who needed to perform legal acts before the court must first swear an

oath on this ring and mention two or more witnesses. ‘I name witnesses’ he must

say, ‘that I swear the oath on the ring, a lawful oath. So help me Freyr and Njo¨r

ðr

and the Almighty a´ss…’

30

28

‘Vo¨lundarkvi

ða’, Edda, str.33.

29

Saxon Chronicles, I, 74.

30

IS I, Landna´mabo´k Hauksbo´k,190; similar descriptions in

o´r

ðar saga hreðu, IS VI, k.1, orsteins

saga uxafo´ts, IS X, k. 1 and Eyrbyggja saga, IS III, k. 4; more rings in Eyrbyggja saga, IS III, k. 16,

Vı´ga-Glu´ms saga, IS VIII, k. 25 and Droplaugarsonar saga, IS X, k. 6.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

164

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

In one of the Edda poems the treacherous god O

´ ðinn swears a ring-oath: ‘Who will

believe his word?’ And elsewhere Atli swears on the ring of the god Ullr.

31

Rings of different sizes have been excavated by archaeologists. It is not known

what exactly their function was, and whether they were ornaments, symbols of dig-

nity, oath rings or part of the military equipment. The well-known Swedish Forsa-

ring with its runic inscription seems to support the written evidence for the use of

rings with an oath ceremony. Its runes have recently been redated to the early Viking

period, and interpreted as a legal article, so that the object has in all probability

been used for legal acts.

32

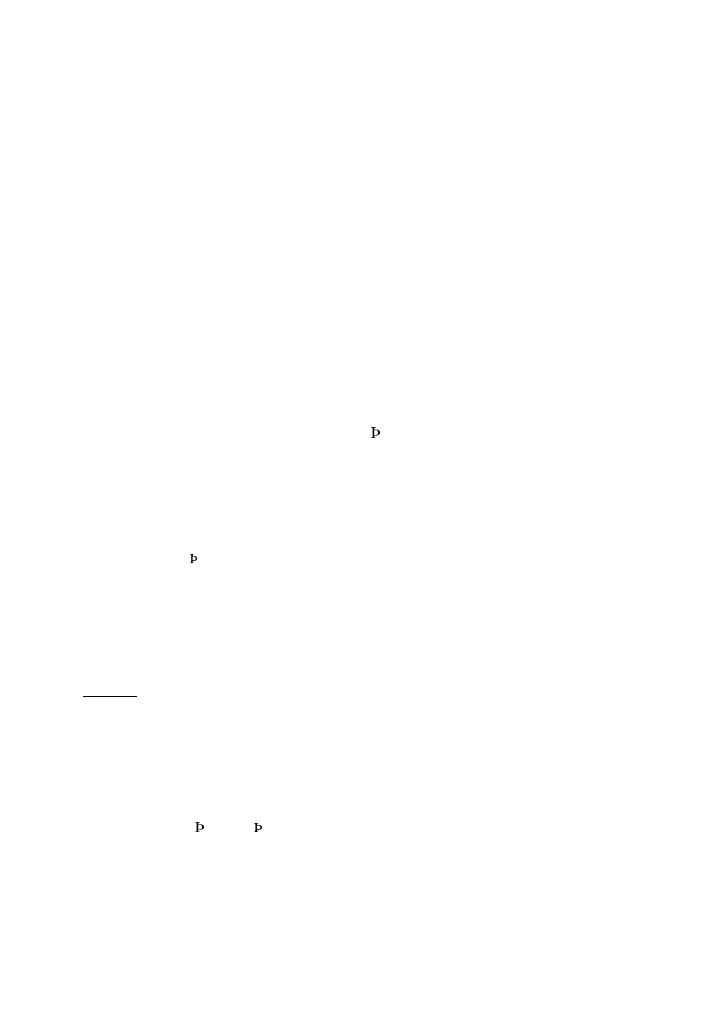

Individuals with rings are portrayed on an eighth-century

Gotlandic picture stone from Ta¨ngelga˚rda (Fig. 1), and on a relief in the doorway

of Fardhem church, Gotland (Fig. 2). Obviously, the rings here too may represent

symbols of dignity as well as oath rings.

33

The official character of the oath was emphasised by pronouncing a formula for

the invocation of Perun and Volos, god of cattle in 907, ‘God’s help’ in 911, the

almighty God and Perun in 944, and Perun and Volos in 971. There are some points

in common with the Icelandic U

´ lfljo´t’s law formula quoted above ‘so help me Freyr

and Njo¨r

ðr and the Almighty a´ss’. The identity of ‘the Almighty a´ss’ has been the

subject of scholarly discussion, with O

´ ðinn, o´rr and Ull as candidates. Olaf Olsen

did not assign any historical value to the formula, interpreting it as a forgery from

the Christian era.

34

More convincing is Pa´ll Sigur

ðsson’s suggestion on the basis of

choice of words that in alma´ttki a´ss stands for the allmighty God, the formula

presenting a mixture of religions on the eve of the official adoption of Christianity

in the year 1000.

35

In the Edda the gods O

´ ðinn and U´llr are associated with oaths

as we have seen.

36

Linguistic investigations, finally, bring Leffler to the conclusion

that the word gu in the Va¨stgo¨talagen oath formula is a neuter plural standing for

‘gods’ rather than for ‘God’.

37

The invocation of the gods was accompanied by a pledge for everlasting peace.

The formula quoted above (944) ‘as long as the sun shines and the world stands

fixed’, alliterating even in Church Slavonic dondezˇe sujaeti solnce i besi miru stoit,

38

is characteristic. At the same time the oath taker would pronounce a self-curse: in

31

‘Ha´vama´l’, Edda, str. 110; ‘Atlakvi

ða’, Edda, str. 30; A. Holtsmark, ‘Kong Atles eder’, Maal og

minne. norske studier, (1941), 1–10; A. Kabell, ‘Baugi und der Ringeid’, Arkiv fo¨r nordisk filologi, 90

(1975), 30

⫺40.

32

F.P. Magoun, ‘On the Old-Germanic altar- or oath-ring (Stallahringr)’, Acta Philologica Scandinav-

ica 20 (1949), 277–91; S. Brink, ‘Forsaringen – Nordens a¨ldsta lagbud’, Beretning fra femtende tværfag-

lige vikingesymposium, ed. E.Roesdahl og P.Meulengracht Sørensen (Aarhus 1996), 27–55.

33

E. Nylen and J.P. Lamm, Bildstenar (Va¨rnamo, 1987), 66–7.

34

O.Olsen, Hørg, Hov og Kirke (København, 1966), 48–54.

35

Pa´ll Sigur

ðsson, ro´unn og y´ðing eiðs og heitvinningar ı´ re´ttarfari, (Reykjavı´k, 1978), 189–229;

on the discussion on the translation of ‘hinn allma´ttki a´ss’, see p. 194.

36

Edda, ‘Ha´vama´l’, str. 110, and ‘Atlakvi

ða’, str. 30.

37

A

¨ ldre Va¨stgo¨talagen, ‘Af Mandrapi’ I; L.F. Leffler, ‘Hedniska edsformula¨r i a¨ldre Vestgo¨talagen’,

Antiqvarisk Tidskrift fo¨r Sverige, 5 (1895), 149–59.

38

The transliteration follows the system of H.G. Lunt, Old Church Slavonic gramma, (The Hague-

Paris, 1974), 16.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

165

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

Fig. 1.

Eighth-century picture stone from Ta¨ngelga˚rda, La¨rbrosn, Gotland, SHM4373. Present height

207 cm. From top to bottom: scene of battle; procession and octopod horse; individuals with rings; sailing

ship. Photograph, Statens historiska museum, Stockholm.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

166

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

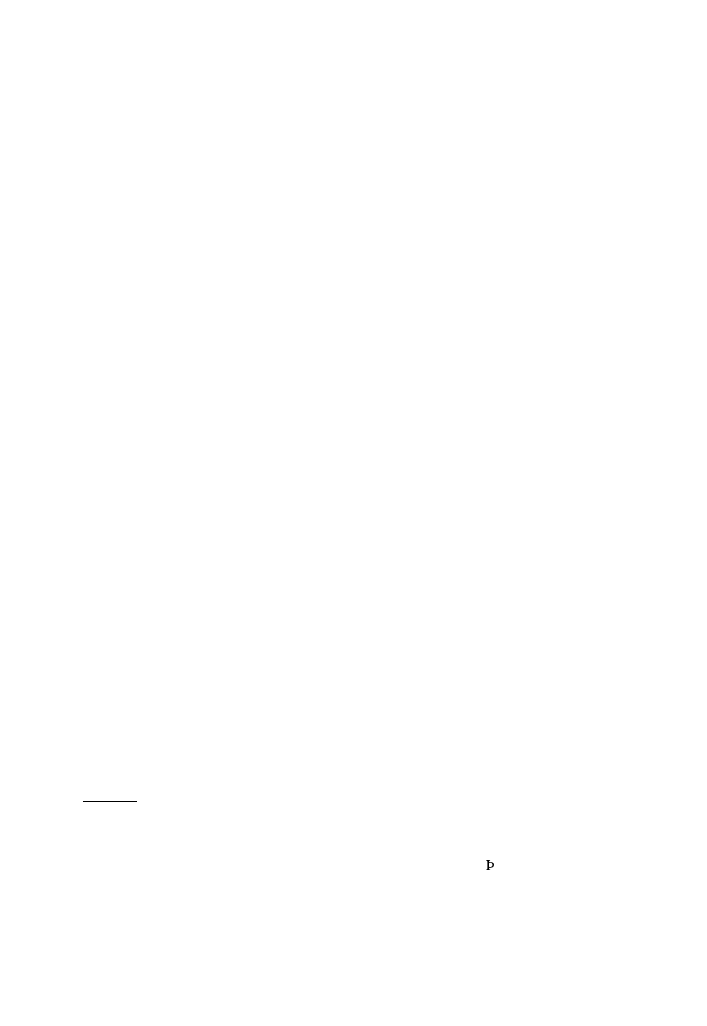

Fig. 2.

A rider with rings. Twelfth-century relief in the choir portal of Fardhem church, Gotland. Photo-

graph by the author.

case he broke his word and violated the everlasting pledge, he would bring the anger

of the gods upon himself, be killed by his own weapons, and be a slave or an outlaw

forever and everywhere. Similar formulae are found all over the North European

area, the concepts ‘everlasting’, ‘forever’ and ‘everywhere’ being given a magic

dimension by picturesque formulae consisting of short, alliterating sentences in coor-

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

167

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

dination. The Old Icelandic lawbook Gra´ga´s for instance, has in its Tryg

ðama´l, or

Peace Guarantee Speech, this formula for settling disputes:

‘But the one of you who tramples on treaties made or smites at sureties given,

he shall be a wolf and be driven off as far and wide as ever men drive wolves

off, Christians come to church, heathens hallow temples, fire flames, ground

grows, son calls mother, mother bears son, men make fires, ship glides, shields

flash, sun shines, snow drifts, Finn skis, fir tree grows, falcon flies a spring-long

day with a fair wind beneath both wings’, and so on.

39

Medieval Frisian Law, too, devoted attention to settling disputes by way of an oath,

as was mentioned. Parties had to swear that their reconciliation would last ‘as long

as the wind blows from the clouds, grass grows, trees flower, the sun rises and

the world exists’.

40

The oath was sworn on objects supposed to have a magic or

symbolic power.

The Christian oath ceremony apparently was nothing special to the chronicler and

his intended readers, so he described it in a few words only: in 907 the Greek

emperors kissed the cross, and in 911 it deserved no mention at all. In 944 the

situation was different: there was an increasing influence of the new religion, ‘since

many of the Varangians were Christians’, and this was worth a more elaborate

description: the Christians among Rus went to the church of St Elias a parish church

near Pasy¨ncha square in the vicinity of the quarter where the Khazars lived. Here

the Holy Cross was placed before them and they kissed it, invoking God. The person

who would violate the oath was to expect punishment from Almighty God, and be

condemned and destroyed, be a slave forever and perish by his own weapons. We

may assume that the spread of Christianity, and churchgoing were the result of con-

tacts with the Greeks.

5. Conclusion

The detailed description in the PC of oaths sworn by Rus sheds light on the

portrayal of the early oath and its development, and makes a closer interpretation

possible of the fragmentary and sometimes controversial data preserved in the North

European sources. With an oath local pagan gods were invoked. Formulae were

pronounced that stressed everlasting peace, or eternal damnation for the one who

39

Gra´ga´s Konungsbo´k, k.115; Laws of early Iceland I, 184–5; similar provisions in Gra´ga´s Sta

ðar-

ho´lsbo´k, k. 387 and 388. The alliteration is shown better in the original text: cristnir menn kirkior søkia.

heidnir menn hof blo´ta. elldr upp brenr. ior

ð grør. mo¨gr moðor callar. oc mo ir mo¨g fo¨ðir. alldir ellda

kinda. scip scri

ðr. scildir blicia. sol scı´n snæ legr. fiðr fura vex. valr flygr va´rlangan dag. stendr honom

byr bein vndir ba´da vængi (…). A similar formula in Grettis saga, IS VI, k. 72 and Hei

ðarvı´ga saga,

IS VII, k. 33.

40

Altfriesische Rechtsquellen,vol. II, art. XLI. The original words are: alsoe langhe, soe di wynd fan

dae vlkenum wayth ende ghers groyt ende baem bloyt ende dio sonne optijocht ende dyo wrald steed.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

168

M. Stein-Wilkeshuis / Journal of Medieval History 28 (2002) 155–168

broke his pledge. The oath was sworn on objects that were probably more or less

dependent on the situation, in the present case, the weapons at the end of an armed

conflict. It looks as though the ring, by its shape a symbol of perpetuity, was an

important attribute. There is no cause to question the correctness of the communi-

cation in the Anglo-Saxon source, or to explain the ring as a bishop’s ring.

41

The

descriptions of oath ceremonies in Landna´mabo´k and the Icelandic sagas deserve a

new analysis rather than to be brushed aside as falsifications.

At the same time, an impression was given of early Christian influences on the

eve of the ‘official’ Christianisation of Rus by Valdemar in the 980s. The treaties

of 907, 911 and 944 show that Byzantine influence in this respect among Rus was

increasing. Svyatoslav’s completely pagan oath in 971 may reflect a temporary

relapse. In the process of transition God simply took his seat next to Perun and

Volos, and the church of St Elias was as suitable for swearing as was the hill with

Perun’s statue; for the Holy Cross, room was made next to the ring, the weapons

and the other objects. In Iceland the situation seems to have been similar: baptised

and unbaptised freely visited their church and temple respectively, according to the

Gra´ga´s formula, and possibly Almighty God appeared in the company of Njo¨r

ðr

and Freyr.

This flexibility is remarkable, as it shows the mutual tolerance of both paganism

and Christianity, and a natural acceptance of one another’s belief. Both religions

seem to have been in peaceful coexistence in this early stage. Elsewhere in the

northern area more examples are found of this attitude: in Lithuania, the Grand Duke

Vytautas, himself still unbaptised as late as around 1400, ordered a church to be

built for Christians living in Kaunas, and in Vilnius the Church of St Nicholas,

predating the official adoption of Christianity, was built to serve the German mer-

chants and artisans living in the city. In general, this changed after the official accept-

ance of Christianity when clerical authorities supported by leaders and their followers

began to establish a church organisation and to abandon the old cults,

42

for instance,

by throwing Perun’s statue into the river Volkhov.

Martina Stein-Wilkeshuis, Dr Phil, studied Dutch language and literature and specialised in Old Germanic

languages. Her doctoral thesis, entitled ‘Het kind in de Oudijslandese samenleving’, was gained at

Utrecht/Groningen in 1970. She has several publications in the field of medieval Scandinavian law, history

and culture, and has been active in teaching.

41

Kabell, ‘Baugi und der Ringeid’, 38.

42

See also B. and P.Sawyer, Medieval Scandinavia, from conversion to reformation, circa 800–1500

(Minneapolis, 1995), chap. 5.

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:18 22 January 2014

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Lotte Hedeager Scandinavian ‘Central Places’ in a Cosmological Setting

Stein Wilkeshuis M A Viking age Treaty Between Constantinople and Northern Merchants, With its Provi

e christanse scandinavian in eastern europe

Studies in Scandinavian Sea Borne Expansion review

Clunies Ross, Royal Ideology in Early Scandinavia A Theory Versus the Texts

Tarat, Personal Jesus Adam of Bremen and ‘Private’ Churches in Scandinavia

Education in Poland

Participation in international trade

in w4

Metaphor Examples in Literature

Die Baudenkmale in Deutschland

Han, Z H & Odlin, T Studies of Fossilization in Second Language Acquisition

2002 4 JUL Topics in feline surgery

Midi IN OUT

Neural networks in non Euclidean metric spaces

więcej podobnych podstron