Porgy and Bess Page 1

Porgy and Bess

Opera in three acts

Music

by

George Gershwin

Libretto by DuBose Heyward,

adapted from his novel, Porgy (1925)

Lyrics by

DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin

Premiere: Boston, September 1935

Adapted from the

Opera Journeys Lecture Series

by

Burton D. Fisher

Story Synopsis

Page 2

Principal Characters in the Opera Page 3

Story Narrative with Music Highlights Page 3

Gershwin and Porgy and Bess

Page 11

the

Opera Journeys Mini Guide Series

Published and Copywritten by

Opera Journeys

www.operajourneys.com

Porgy and Bess Page 2

Story Synopsis

The story of Porgy and Bess takes place in the

1920 s in Catfish Row, a racially isolated slum

neighborhood near Charleston, South Carolina.

Bess is a prostitute; her lover is Crown, a stevedore

prone to ferocious violence. Crown kills Robbins after

a dispute during the tensions of a crap game: Crown

flees after the murder. Porgy, a cripple, shows kindness

and humility to the beautiful but dissolute Bess, and

shelters her. Porgy and Bess fall in love: he protects

her against community reproach and the temptations

offered by Sportin’ Life, the local dope peddler.

Porgy urges Bess to attend a picnic with the

townsfolk at Kittiwah Island. Unbeknownst to her,

Crown has been hiding on the island. Despite her

genuine love for Porgy, Crown overcomes her

resistance, and she surrenders to him, and remains with

him on the island. Bess returns to Catfish Row,

trembling, sick, and delirious. Porgy intuitively knows

that Bess betrayed him, but he forgives her, reaffirms

his love for her, and nurses her back to health.

A hurricane erupts while Catfish Row fishermen

are at sea. Crown reappears and offers to brave the

storm to save the fishermen, at the same time, mocking

Porgy as a feeble and weak man. Crown survives the

storm and returns to reclaim Bess. When he arrives,

Porgy kills him.

The police find Crown’s body and arrest Porgy as

a suspect. A week later, Porgy is released and

reappears triumphantly on Catfish Row. He turns to

despair when he learns that Bess fled to New York

with Sportin’ Life. Even though Bess betrayed him,

Porgy loves her deeply: he mounts his goat cart and

leaves Catfish Row in search of Bess.

Porgy and Bess Page 3

Principal Characters in the Opera

Porgy, a cripple

Baritone

Crown, a stevedore, Bess’s lover

Bass

Bess, Crown’s girlfriend

Soprano

Robbins, a crap player

Baritone

Serena, Robbins’s wife

Soprano

Jake, a fisherman

Baritone

Clara, Jake’s wife

Soprano

Sportin’ Life, a dope peddler

Tenor

Peter, the honey man

Tenor

Lily, Peter’s wife

Mezzo-soprano

Frazier, a lawyer

Baritone

Residents of Catfish Row, Strawberry woman, the

crab man, Jim the cottonpicker, undertaker,

fishermen, children, stevedores, hucksters,

policeman, a coroner, detectives, and bystanders

TIME:1920s

PLACE: Catfish Row, a slum neighborhood near

Charleston, South Carolina

Story Narrative with Music Highlights

ACT I – Scene 1: Catfish Row

Catfish Row was formerly an upscale suburb

of Charleston, but it is now a slum neighborhood

inhabited by black African-Americans.

The Jasbo Brown Blues is heard as folks

indulge in impromptu dancing in the street.

Clara sings a lullaby to her baby, Summertime,

while in the background, a heated dice game is

in progress.

Jake, Clara’s husband, sings to the baby about

the guiles and wiles of women.

A Woman is a Sometime Thing

Porgy and Bess Page 4

Porgy, a cripple, arrives on his goat-cart. The

folks immediately tease him about his physical

disability, but he protests, assuring them that

he is a man with pride and self-respect: When

Gawd make him a cripple, He mean him to be

lonely.

Crown, a stevedore, arrives: he is drunk and

accompanied by his ostentatiously-dressed

girlfriend, the prostitute, Bess. Crown joins the

crap game, loses very quickly, and immediately

erupts into rage. He quarrels with Robbins,

accuses him of cheating, attacks him, and then

kills him with a cotton hook. Bess gives Crown

money: he flees and goes into hiding.

Sportin’ Life, the neighborhood dope

peddler with a devil-may-care philosophy, tries

to tempt the lonely Bess to go to New York with

him, but she refuses.

Police whistles are heard, and in fear, Bess

desperately seeks refuge. Neighbors spurn her,

but Porgy generously offers to share his room

with her.

ACT I – Scene 2: Serena’s room

The Catfish Row neighbors gather in

Serena’s room where her husband Robbins’s

body lies: there is a saucer on his chest to

collect donations for burial expenses; all sing

spirituals to mourn their friend and comfort his

widow.

Porgy arrives with Bess. He places money

in the saucer, and exhorts the others to do the

same: Overflow, overflow.

Two white detectives arrive, searching for a

suspect in Robbins’ smurder: they apprehend

the half-deaf old Peter as their “material

witness.” They also advise Serena that according

to law, Robbins’s body must be buried the next

day: the sympathetic undertaker, realizing that

not enough money has been collected for the

burial, agrees to bury Robbins and to wait for

the balance. Sorrowfully, Serena laments the

Porgy and Bess Page 5

loss of her husband.

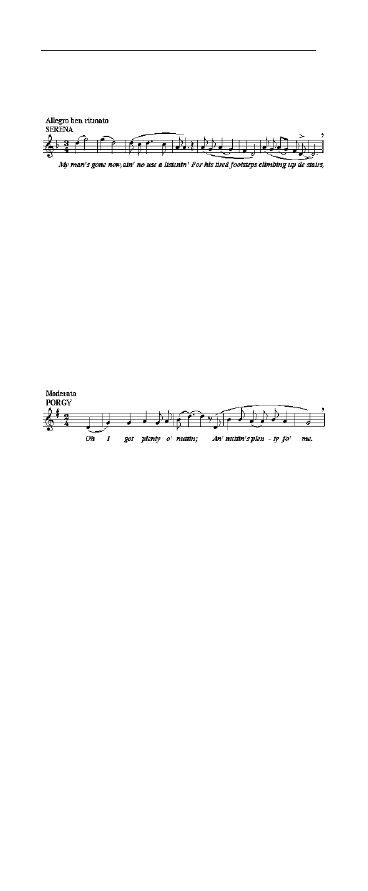

My Man’s Gone Now

ACT II – Scene 1: Catfish Row in the morning

Jake and fisherman repair their fishing nets

and prepare to go to sea despite warnings about

impending September storms.

Porgy appears at a window and expresses

his contentment and happiness since Bess has

come to live with him.

Oh I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’

Sportin’ Life struts by, peddling dope. When

he blows white powder from his hand, Maria,

the cook, protests, admonishing him that

“nobody ain’ goin’ peddle happy dust roun’ my

shop”: she threatens him with a knife and he

flees.

Frazier, the lawyer, finds Porgy and offers

to sell him a divorce for Bess, pointing out that

it is much more difficult to divorce someone

who has never been married. Mr. Archdale

appears and offers to provide bond for the still-

jailed Peter. A buzzard is seen flying overhead,

and everyone becomes filled with premonitions

of evil: it would be bad luck if the bird should

alight near them: the Buzzard Song.

Sportin’ Life reappears, finds Bess, and

suggests that she leave Catfish Row and go to

New York with him. Bess, now content with

Porgy, declines his offer. Porgy warns Sportin’

Life to stay away from Bess: although a cripple,

Porgy is a powerful man; he frightens the dope

Porgy and Bess Page 6

peddler, who flees in terror.

Porgy and Bess become enraptured in their

new-found love: the sorrows of their past lives

have ended, and together, happiness has just

begun; they vow eternal love.

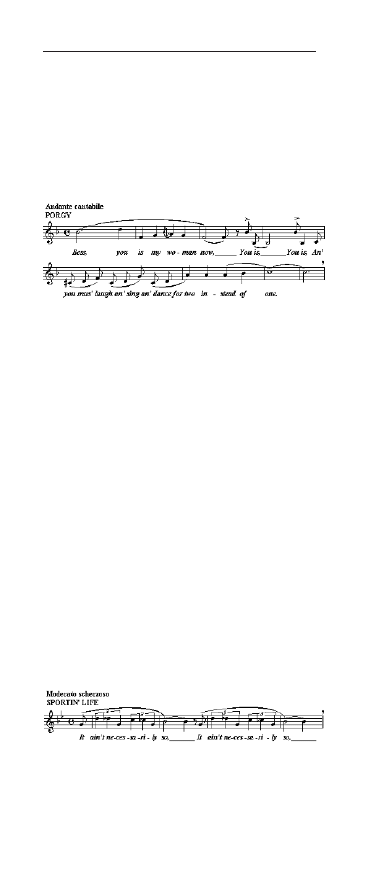

Bess You is My Woman Now

A jazz band heralds the Catfish Row

residents to a picnic on Kittiwah Island. Bess

tells Porgy that she wants to stay home with

him, but Porgy insists that she join the

picnickers and have a good time. As all the

Catfish Row residents start on their way to the

picnic, Porgy again celebrates his new-found

happiness with Bess: I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’.

ACT II – Scene 2: Kittwah Island that evening

All the picnickers sing and dance: I ain’t got

no shame.

Sportin’ Life delivers an amusing, skeptical,

and cynical sermon about the credibility of Bible

teachings.

It Ain’t Necessarily So

Serena denounces everyone as sinners:

Shame on all you sinners, further reminding

them that they must hurry to catch the boat or

Porgy and Bess Page 7

they will all be left behind on the island.

As Bess lingers, Crown, who had been

hiding on the island after he murdered Robbins,

suddenly appears to tell her that he will soon

return to Catfish Row for her. Bess pleads with

him to find another woman and let her remain

with Porgy and live a decent life. Crown berates

Bess, advising her that her living arrangements

with Porgy are temporary: they will cease the

moment he returns.

Nevertheless, Crown possesses a seductive

power over Bess: he reminds her that she is

his woman; Bess is unable to resist him and

surrenders to his wishes. The boat leaves the

island, and Bess remains with Crown.

ACT II – Scene 3: Catfish Row

It is dawn about a week later. Jake and the

fishermen prepare to go out on their boats

despite threatening storms.

Bess returned from Kittiwah Island, but

since then, she has been ill: her delirious voice

is heard from Porgy’s room. Serena, Porgy, and

others pray for her recovery: All right now. Dr.

Jesus done take de case.

In the background, Catfish Row comes to

life as morning cries are heard from the

strawberry woman, the honeyman, and the crab

man.

As Bess recovers, she calls for Porgy. Bess

admits she surrendered to Crown in fear for her

life. Porgy forgives her for betraying their love,

and tells her he will care for her: if Crown

returns again, he promises to protect her from

him.

Porgy and Bess Page 8

I Loves You Porgy

As the storm approaches, Clara watches the

sea anxiously. Suddenly, the fearful sound of

the hurricane bell is heard.

ACT II – Scene 4: Serena’s room

As the terrible storm rages outside, the

fishermen’s wives pray, fearing that Nature’s

anger has brought them to Judgment Day.

Crown arrives to reclaim Bess. He forces

his way into the room, taunts Porgy, calling him

a weak cripple, and then brutally pushes him

down.

Clara peers through the window and

becomes horrified: she sees her husband Jake’s

fishing boat floating upside down. She gives her

baby to Bess and rushes out. Only Crown

volunteers to help, and as he leaves, promises

Bess that he will return for her shortly.

ACT III – Scene 1: Catfish Row

The women mourn, fearing that Clara, Jake,

and Crown, have all been lost in the storm.

Sportin’ Life wanders in to report that Crown

has survived. Bess sings a lullaby to Clara’s baby:

Summertime

Crown appears, badly hurt, but stealthily

moving towards Porgy’s room where he expects

to find Bess. As he approaches the window,

Porgy and Bess Page 9

Porgy’s powerful arm extends, and seizes Crown

by the throat: Porgy plunges a knife into Crown

and kills him.

In triumph, Porgy proudly proclaims: “Bess,

you got a man now. You got Porgy.”

ACT III – Scene 2: Catfish Row.

The police arrive to investigate Crown’s

death, but find no clues to his murder. Serena

tells them that she was ill and knows nothing of

the death of the man, who, as everyone in Catfish

Row will swear, killed her husband Robbins.

The police suspect that Porgy knows

something about Crown’s murder: he is dragged

away to identify Crown’s body. Porgy protests,

telling them that he refuses to look at the dead

Crown; his apprehension was inflamed by

Sportin’ Life who told him that Crown’s wound

will begin to bleed when the man who killed

him comes near the body. As Porgy leaves, Bess

reprises Serena’s doleful lament when her

husband Jake died: My Man’s Gone Now.

Bess, in confusion and despair, believes that

Porgy is gone forever. Sportin’ Life exploits

her sorrow and loneliness and offers her some

“happy dust” to relieve her anxiety. Again,

Sportin” Life tries to persuade her to escape

with him to New York: There’s a Boat That’s

Leaving Soon for New York. As Sportin’ Life

departs, he leaves a package of dope on a step.

Bess, unable to control her will power, yields

to temptation, takes the package, and carries it

with her to her room.

ACT III – Scene 3: A week later.

Life in Catfish Rows seems to have returned

to normal: children dance and sing in the street

as people greet one another cordially.

Porgy returns in high spirits: he had refused

Porgy and Bess Page 10

to look at Crown’s body, was cited for contempt,

and was ordered to spend one week in jail. Porgy

brings presents for all his friends, his sudden

wealth the result of successful crap-shooting

while in jail.

Porgy calls for Bess, but she does not

answer. He pleads for information as to her

whereabouts and learns that Sportin’ Life finally

seduced Bess: She fled with him to New York.

Porgy is heartbroken and yearns for Bess:

Serena condemns her, but Maria excuses her.

Porgy inquires about New York, and learns

that it is thousands of miles away. Undaunted,

he mounts his goat cart: Porgy is determined

and resolved to find Bess wherever she may be:

when he finds her, he will bring her back to

Catfish Row.

All the neighbors, sharing Porgy’s hope and

optimism, help speed him on his journey to find

Bess: Oh, Lawd, I’m on My Way.

Porgy and Bess Page 11

Gershwin………………..and Porgy and Bess

T

he American composer, George Gershwin,

1898 – 1937, nee Jacob

Gershovitz, was the son of Russian-Jewish

immigrants who settled in New York in the

1890s. At the age of 12, the young Gershwin

exhibited exceptional musical talents at the

piano: he immediately pursued studies with

teachers who astutely recognized his potential,

and encouraged and exposed him to classical

music and the concert stage. Gershwin

eventually became an accomplished and skilled

pianist, at the same time, continuing intensive

studies in musical theory and harmony.

However, Gershwin was drawn to American

popular music, particularly inspired by the

songs of those early icons flourishing in the

early 20

th

century: Jerome Kern and Irving

Berlin. In 1914, just short of his 16th birthday,

he followed his muse and left high school to

work as a song promoter for the Tin Pan Alley

music-publishing firm of Joseph Remick. Two

years later, he published his first song, When

You Want ‘Em You Can’t Get ‘Em. Although the

song was unsuccessful, it demonstrated his

creative talent, attracting the attention of the

operetta composer Sigmund Romberg who

included one of his songs in his Broadway show,

The Passing Show of 1916. During those early

years, Gershwin eked out a living as a rehearsal

pianist, but religiously continued his studies of

piano, harmony, theory, and orchestration.

In 1918, at the age of 20, Gershwin became

a staff composer at T. B. Harms, the leading

publisher of music for the Broadway stage.

Before long, he composed his first hit song,

Porgy and Bess Page 12

Swanee (1918), performed by Al Jolson in the

Broadway show, Sinbad. Shortly thereafter, he

composed his first full Broadway score, La, La

Lucille (1919). Those early successes led to a

contract with the producer George White to

compose music for the George White’s

Scandals of 1920; thereafter, Scandals became

an annual revue that included dozens of

Gershwin songs.

In 1922, Gershwin composed Blue

Monday, a 20-minute opera written in the

African-American music style: it became part

of George White’s Scandals of 1922, later re-

titled 135

th

Street. The work attracted the

attention of the Scandals’ conductor, Paul

Whiteman, who commissioned him to

compose a symphonic, jazz-style work:

Rhapsody in Blue (1924).

Throughout the flourishing Broadway era of

the 1920s and 1930s, Gershwin became one of

Broadway’s leading lights, eventually

composing the scores for 22 successful shows,

among them Lady, Be Good! (1924), containing

the songs Fascinating Rhythm, Oh, Lady, Be

Good!, and The Man I Love, the latter written

for the original production but not included.

In 1924, Gershwin began his collaboration

with his brother, Ira, (1896–1983), and together

they created Tip Toes (1925), Oh, Kay! (1926),

Strike Up the Band (1927), Funny Face (1927),

and Girl Crazy (1930). Their most successful

show, Of Thee I Sing (1931), a satire about the

American political system, became the first

musical to win a Pulitzer prize in drama.

Gershwin songs also appeared in the motion

pictures Delicious (1931), Shall We Dance

(1937), A Damsel in Distress (1937), and the

Goldwyn Follies (1938).

A

s a teenager, Gershwin was inspired by

African-American music, its very

distinctive ragtime, stride, and blues genres

becoming a musical vocabulary that he would

later incorporate in many of his compositions.

Porgy and Bess Page 13

The blues musical genre evolved from the

expressive folk music of African-Americans:

it developed after the Civil War, largely based

on the songs of agricultural field workers. As

the blues genre developed in the early 20

th

century, its poignant lyricism became combined

with music expressing emotional sadness and

melancholy, all embellished with melodic

ornamentation, and syncopation.

The jazz musical genre was also developed

by African-Americans, but it was strongly

influenced by European harmonic structures

which were combined with African rhythmic

structures. Jazz, as a musical art form, is

virtually impossible to define: for most of jazz

history, it has been generally accepted that it is

a style of music in which the performer plays

melodic variations based on specific harmonies

against a regular rhythmic pulse. Nevertheless,

like all music, jazz has evolved and transformed,

thus precluding an absolute definition. As such,

there are a host of jazz styles such as avante-

garde, modernist, progressive, traditional,

classical, and many others.

Jazz began to flourish in the early 1920s

when its inherent structural techniques were

steadily becoming proficient, sophisticated, and

harmonically more daring. In an orthodox

approach to music, the artist fundamentally

expresses the creative wishes of the composer:

in jazz, the performer is an improviser, or his

own composer. In the 1920s and 1930s, George

Gershwin, obsessed with the genre, had many

prominent jazz and blues masters to emulate

and learn from: Fats Waller, Duke Ellington,

Louis Armstrong, and Fatha Hines.

Gershwin explicitly identified himself as a

“jazz” composer, and in the process, profoundly

influenced the destiny of American music:

Gershwin, through his compositions, became a

powerful force in nourishing and revitalizing

the idiom. His first successful instrumental

work, the Rhapsody in Blue (1924), introduced

Porgy and Bess Page 14

jazz into the concert hall. Its premiere was

conducted by Paul Whiteman, and was billed as

“An Experiment in Modern Music,”its

purported intent, to demonstrate that jazz, then

considered a form of rhythmic dance music that

was anathema to most “serious” musicians and

critics, could indeed be sophisticated, refined,

and a serious form of music when transformed

into a symphonic context.

G

ershwin composed in two musical

languages: popular music, and

classical concert music; in both instances, he

was a trailblazer, innovator, and pioneer.

Gershwin’s primary successes were in the

Broadway musical for which he became a master

of all the popular song idioms, among the many

styles, the striding one-step, and the more

contemplative ballad. But of equal importance

were his “serious” compositions in which he

blended classical music forms and techniques

with the stylistic nuances of popular music and

the jazz idiom. As a result, his musical

eclecticism has perplexed critics who search

for a specific “Gershwin identity” or “native

style.” Nevertheless, no matter the idiom, his

captivating music never ceases to mesmerize

the American public who seem to always find it

fresh and ravishing. Europeans, seemingly

unimpeded by the need to identify between

“high” or “low” artistic genres, have long

considered Gershwin one of greatest song-

writers of the 20

th

century: ardent fans have

included prominent classical composers such

as Francis Poulenc, Arnold Schoenerg, the

creator of the 12 tone and serial musical

techniques, and Maurice Ravel, who modeled

his Piano Concerto in G on Gershwin idioms.

Beginning in 1924, together with his

brother Ira, now his permanent lyricist and

artistic collaborator, they created hundreds of

songs for dozens of Broadway shows: their

songs were about romance and love. Ira provided

lyrics with his trademark verbal ingenuity and a

Porgy and Bess Page 15

profoundly sensuous yearning. George

composed music with beauty, warmth, and

tenderness, much of which combined the

rhythms and harmonies from the rich African-

American musical styles of blues and jazz.

Nevertheless, it was specifically after the

success of the Rhapsody in Blue that new

patterns emerged in Gershwin’s composing life.

He never lost his touch and continued to

compose prolifically for both Broadway and

Hollywood, but he devoted unbridled energy to

his more serious compositions in the classical

vein: the Piano Concerto in F for piano and

orchestra (1925), the Preludes for Piano

(1926), the tone poem An American in Paris

(1928), and the Cuban Overture (1932).

Although African-American music was indeed

the major source of his inspiration, his music

shows strong influences from Igor Stravinsky,

Claude DeBussy, Piotr Tchaikovsky, and even

from the anguish and suffering so prevalent in

Jewish chants: in 1929 he contracted to

compose a “Jewish opera,” The Dybbuk, for

the Metropolitan Opera, but he never fulfilled

that commission.

Few events in the history of American music

were more shocking and unexpected than

Gershwin’s sudden death: he was still youthful,

vibrant, vigorous, and on the threshold of so

many new musical achievements. During 1937,

although he had been experiencing discomfort,

dizziness, and emotional despondency, he

continued to work. Inspired by the string

quartets of Arnold Schoenberg, his Hollywood

neighbor and sometime tennis partner, he

considered writing a quartet as well as a ballet

for RKO’s Goldwyn Follies to be called Swing

Symphony. But in July he fell into a coma. A

brain tumor was diagnosed and emergency

surgery performed. On the morning of July 11,

1937, George Gershwin died at the age of 38,

another musical genius, like Mozart, Schubert,

and Chopin, whose early, premature death, left

the music world mourning, wondering what

Porgy and Bess Page 16

other musical treasures could have been added

to his already monumental legacy.

A

bout eighty years ago, in New York, a group

of writers and intellectuals,

self-proclaimed “modernists,” were embarking

on an experiment whose purpose was to integrate

the rich fabric of American Negro culture into

the arts. Carl Van Vechten, a novelist, music and

drama critic, became their chief architect,

enthusiastically calling upon African-American

artists to celebrate the priceless treasures of black

Americana in the arts: “The squalor of Negro

life, the vice of Negro life, offer a wealth of novel,

exotic, picturesque material to the artist.”

Additionally, he questioned if “Negro writers

were going to write about this exotic material

while it is still fresh or will they continue to make

a free gift of it to white authors who will exploit it

until not a drop of vitality remains?” Their

adventure became known as the “Harlem

Renaissance”: it incited controversy and

argument, nevertheless, it became a springboard

and inspiration for many contemporary writers

to adjust their focus toward the rich treasures

within African-American culture: Sherwood

Anderson’s Dark Laughter (1925), Van Vechten’s

Nigger Heaven (1926), and from the same era,

Edwin DuBose Heyward’s Porgy (1925).

Edwin DuBose Heyward, 1885-1940, a native

of Charleston, South Carolina, grew up as the

poorly educated scion of a family whose

fortunes had been reversed by the Civil War and

its ensuing depression.

At the age of 17, he worked for a cotton

factory on the Carolina waterfront where he

keenly observed the plight of black stevedores

and fishermen. Likewise, in Charleston, he

witnessed its exotic mix of racial life where

former slaves and former owners lived within a

dynamic geographic proximity, yet were

separated by racial and social restrictions,

impasses, and divides; in the downtown

Porgy and Bess Page 17

neighborhoods African-American domestics and

doctors lived side-by-side with those same

aristocratic families who formerly commanded

their lives and their labor.

Heyward observed African-Americans

folklore and culture with a passionate curiosity

that served to kindle his literary inspiration and

imagination. Ultimately, his literary objectives

became lofty and ambitious, as he explained in

an essay titled The New Note in Southern

Literature:

“In the well-bred southern drawing room of

a decade ago, the ‘Negro Problem’ was never

mentioned. And so the authors who undertook

to interpret Negro life divided themselves into

two general classes: those who deal altogether

delightfully with the Negro of the past, and

those who took the Negro’s sense of humor as

a keynote, caricatured it beyond recognition,

and produced a comedian so detached from life

that he could be laughed at heartily without the

least disloyalty to the taboo. Now the task that

confronts the South today is simply this: to

readjust its standards of good taste in manners,

if you will. But for art, its own code of good

taste, based upon a fearless and veracious

moulding of the raw human material that lies

beneath its hand.”

Heyward was searching for a truth in the

African-American experience, rather than a

stereotype. His mission was lofty and noble:

he intended to expand “the standards of good

taste” in Southern drawing rooms, and make “a

fearless and veracious molding of . . . raw human

material.” Heyward strove for that “truth” he

was seeking which materialized in his first

novel, Porgy (1925).

Porgy became a literary triumph for

Heyward, but immediately, the novel was thrust

into broiling and indignant controversy. Porgy

was considered an unflattering portrait of an

American ethnic group who were living under

the worst possible circumstances, poor and

struggling victims of the social structure whose

Porgy and Bess Page 18

cast of characters, for the most part, were

portrayed as dissolute, dishonest, and vicious.

To its antagonists, Porgy portrayed stereotypes

and was considered a failure, neglecting to

address positive elements within the ethnic

group: those proud heirs of ambitious, aspiring,

and motivated pre-war free black elites, or the

successful descendants from Reconstruction-

era politicians and businessmen.

However, there were critics who felt that

Heyward had created a truthful work of art full

of complex meanings that was irresistibly

appealing to both white and black audiences

through its penetrating insight into certain

realities of African-American life.

Nevertheless, by its very nature, Heyward’s

Porgy was provocative, and some naturally

considered it an evocation, or an invocation, of

racial fears and fantasies, perceiving its

caricatures and stereotypes offensive and

affronting.

In general, contemporary reviews from the

national press were lavish in their praise:

Langston Hughes, a black poet and writer who

was one of the foremost interpreters to the

world of the black experience, called Heyward

one who saw, “with his white eyes, wonderful,

poetic qualities in the inhabitants of Catfish Row

that makes them come alive…”; the Baltimore

Sun noted that “With Porgy Heyward took the

first rank. The humble crippled Negro (sic)

beggar was a figure made utterly real to

Heyward’s readers . . . ‘Porgy’ . . . is, in the most

satisfying way, a . . . story written with a skill -

no, mastery - that give the reader a sense of

fullness, richness, and life”; the New York

Evening Post called Porgy “a series of

throbbing moments, a ghost of Africa stalking

on American soil,”; the Pulitzer Prize-winning

American novelist, Ellen Glasgow, noted it was

“born a classic. Nothing finer has occurred in

American literature since Uncle Remus.”; the

Nation found it “a fresh and finished picture of

the simple Southern Negro. And because he

Porgy and Bess Page 19

writes with poetry and penetration his story is

a moving one; because he writes with

detachment and tenderness . . . a fusion of

comedy and tragedy is delicately achieved.”

When Heyward died in 1940. The New York

Times hailed him as the foremost chronicler

of the “strange, various, primitive and

passionate world” of the Negro.

H

eyward was inspired to the Porgy story by

a newspaper crime report (in either 1918

or 1923, depending on the source) about a

murder of passion committed by a maimed and

crippled black man, a well-known local

character called “Goat Cart Sam,” or “Goat

Sammy,” a man who could not stand upright,

and was forced to travel around in a goat-drawn

cart.

Heyward took literary license in his

transformation of “Goat Cart Sam” into his

central character, Porgy. The real Sam

apparently bore little resemblance to

Heyward’s saintly Porgy: the real Sam is reputed

to have been a drunk and a gambler; there was

no Bess in his life but he was known to have

had plenty of girlfriends who he was always

beating with his goat whip; and children were

so scared of him that they anointed him the

“bad” man.

Heyward’s was a literary master: his Porgy

novel is saturated with colorful, provocative

prose. He opens with a profoundly romantic

portrait of Catfish Row:

...not a row at all, but a great brick

structure that lifted its three stories about the

three sides of a court. The fourth side was

partly closed by a high wall, surmounted by

jagged edges of broken glass set firmly in old

lime plaster, and pierced in its center by a

wide entrance-way. Over the entrance there

still remained a massive grill of Italian

Porgy and Bess Page 20

wrought iron, and a battered capital of marble

surmounted each of the lofty gate-posts. The

court itself was paved with large flag-stones,

which even beneath the accumulated grime

of a century, glimmered with faint and varying

shades in the sunlight.

And of Charleston, a city bordering on

decadence and ruin:

Porgy lived in the Golden Age. Not the

Golden Age of a remote and legendary past;

nor yet the chimerical era treasured by every

man past middle life, that never existed except

in the heart of youth; but an age when men,

not yet old, were boys in an ancient, beautiful

city that time had forgotten before it destroyed.

And of Sportin’ Life, the vain and deceitful

trickster, the dangerous and destructive force

to the Catfish Row social order who invokes

all of his evil to seduce Bess:

Sportin’ Life lifted his elegant trousers, so

that the knees would not bag, and squatted

on the flags at [Bess’s] side. He removed his

stiff straw hat, with its bright band, and spun

it between his hands. The moonlight was full

upon his face, with its sinister, sensuous

smile....He poured a little pile of white powder

into [her hand]. There it lay in the moonlight,

very clean and white on her dark skin.

“Happy dus!” she said, and her voice was like

a gasp.

Crown is the monstrous villain whose

killing rage threatens the stability of the Catfish

Row community. Crown is described as a man

possessing overwhelming physical power, and

capable of brutal savagery: his aggression

mesmerizes the Catfish Row residents to

incomprehensible fear. Heyward describes

Crown’s brutal murder of Robbins:

Porgy and Bess Page 21

With a low snarl, straight from his crouching

position, Crown hurled his tremendous weight

forward, shattering the lamp, and bowling

Robbins against the wall . . . The oil from the

broken lamp . . . blazed up ruddily. Crown was

crouched for a second spring, with lips drawn

from gleaming teeth. The light fell strong upon

thrusting jaw, and threw the sloping brow into

shadow. One hand touched the ground lightly,

balancing the massive torso. The other arm

held the cotton-hook forward, ready, like a

prehensile claw . . . A heady, bestial stench

absorbed all other odors. A fringe of shadowy

watchers crept from cavernous doorways,

sensed it [the scent], and commenced to wail

eerily.

The women of Catfish Row are either the

stereotypical mammy type, like the devout

Serena Robbins, whose husband boasted “Dat

lady ob mine is a born white-folks nigger,” or

the imposing Maria, who puts the fear of god

into Sportin’ Life, or they are prostitutes like

the ill-fated Bess.

When Bess first appears, she is drunk. Maria

serves her food and comments that her eyes

have “the acid of utter degradation.” Bess is

dissolute, and initially tries to play Porgy for

“the good money he gits fum the w’ite folks”:

it is later that Porgy’s love tames the wild beast

lurking in her soul. Nevertheless, Bess cannot

resist the lure of Sportin Life’s “happy dus,” or

Crown’s “hot hands.” Heyward’s description of

their meeting on Kittiwah Island leaves no doubt

that Bess, as well as Crown, are creatures of

instinct rather than of reason. Crown says “I

know yuh ain’t change. With yuh an’ me it always

goin’ tuh be de same. See?” And then he grabs

her body with such force that her breath is forced

from her.

Heyward portrays Catfish Row as a strong,

bonded community: the spirituals sung at

Robbins’s funeral have an almost familial

earnestness, and the resident’s virtual silence

Porgy and Bess Page 22

to the questioning of the racist police officers

represents a form of communal resistance, but

also a perceptive awareness of their unfortunate

status.

The real threats to the Catfish community

were the terrifying hurricane that devastated the

“Mosquito Fleet” of fishermen, an actual

historical event, and the community’s villainous

characters: the trickster Sportin” Life, and the

murderer, Crown. Those threats are neutralized

by the “mammie” figures of Serena and Maria

who unite against Sportin’ Life, as well as of

Porgy himself, whose seeming weakness

transforms into incredible strength: the crippled

man lies in wait for Crown, exploits every iota

of his energy, overpowers him, and destroys the

threat.

A

fter Dorothy Kuhns married DuBose

Heyward in 1923, she persuaded him

to abandon his insurance business and devote

his full-time to writing. At the time, she had

become a celebrated playwright in her own right,

and later adapted his novels for the Broadway

stage: Porgy in 1927, and Mamba’s Daughters

in 1929. Al Jolson approached Heyward to buy

the rights to Porgy for a musical in which he

would play the lead in blackface, but Heyward

rejected his proposal.

The idea of writing a full-length opera based

on Heyward’s Porgy first occurred to Gershwin

when he read the book in 1926. In 1933, after

many years of contemplation and

correspondence, Heyward and the Gershwin

brothers finally contracted to collaborate and

transform Porgy into an opera: the libretto

would be written by Heyward and Ira Gershwin,

and the lyrics by Ira and George Gershwin.

Heyward himself later contributed the lyrics for

Summertime and My Man’s Gone Now.

Gershwin vowed to be thoroughly

meticulous and faithful to Heyward’s story. In

preparation for his new challenge, he spent a

Porgy and Bess Page 23

summer absorbing the local atmosphere near

Charleston where he observed residents who

would become the prototypes for his Catfish

Row residents. Ultimately, Porgy and Bess

became the composer’s most ambitious work,

its score containing 700 pages of recitatives and

orchestration. According to David Ewen,

Gershwin’s first biographer, Gershwin adored

the work and it possessed him: he “never quite

ceased to wonder at the miracle that he had been

its composer. He never stopped loving each and

every bar, never wavered in the conviction that

he had produced a work of art.”

By early 1935 the composition of Porgy

and Bess was completed. In order to assure

more performances, Gershwin chose to have

the work performed at the Alvin Theater on

Broadway rather than as a full operatic

production. Porgy and Bess opened in New

York in September 1935, its premiere

supposedly disappointing yet its initial run

included 124 performances. Nevertheless, its

Broadway run, together with a subsequent tour,

failed to earn enough to recoup the original

financial investment. In spite of Gershwin’s

vaunted record of previous successes, his last

and most ambitious work for the stage was

financially unsuccessful.

By and large, the African-American

community, then and now, has steadfastly

refused to embrace Porgy and Bess,

traditionally staying away from it in droves, and

considering it a tasteless image of African-

American life. Duke Ellington despised the

opera version, and condemned Gershwin as a

plagiarizer of African-American music. The

renowned music critic, Virgil Thomson,

concurred, noting that it was a “libretto that

never should have been accepted on a subject

that never should have been chosen [by] a man

who should never have attempted it . . . Folk-

lore subjects recounted by an outsider are only

valid as long as the folk in question is unable to

speak for itself, which is certainly not true of

Porgy and Bess Page 24

the Negro in 1935.”

Other critics questioned Gershwin’s

credentials and technical ability to compose a

full-fledged opera. But more importantly, just

like the agitated condemnation of Heyward’s

novel ten years earlier, the opera was rejected

for its portrayal of African-American hardships

long after slavery and emancipation, its racial

stereotyping, and in its characterizations, the

irresponsible lifestyles, and the predisposition

for violence: Porgy and Bess was viewed in

some quarters as yet another hindrance to the

quest of black Americans for social respect.

Ironically, in the story’s transformation into

an opera, controversies over segregation

prevented it from coming to the city that

inspired it until the Charleston Tricentennial

festivities in 1970. MGM made a film of the

opera in 1959, but it was a total failure even

with its all-star cast that included Pearl Bailey,

Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier, Sammy

Davis Jr., and a young Diahann Carroll, all of

whom had deep feelings of ambivalence over

the film. Contributing to the film’s failure,

controversies over segregated seating in the

South prompted an exasperated Goldwyn to

cancel all Southern engagements.

Perhaps the keenest of the ironies

surrounding Heyward’s Porgy and its later

incarnation into an opera is the fact that it has

given employment and opportunity to so many

blacks in the entertainment field, although in

its 1927 stage adaptation, periodic revolts from

cast members was the rule rather than the

exception.

Nevertheless, Porgy and Bess has become

synonymous with Charleston, and today, its

tourist-minded city fathers have exploited it

with nightspots that have become legendary:

tourists clamor to see Catfish Row, even though

it is fictional and nonexistent. Meanwhile, in

Vienna, the old Jugenstil bar of the

“Fledermaus” night club has been renamed

Porgy & Bess, now a center for jazz outside of

Porgy and Bess Page 25

the mainstream, and there is a Porgy en Bess jazz

bar in Amsterdam

Most of Porgy’s songs achieved immediate

popularity, but the work earned its real approval

and favor only after the 1940 Theater Guild

presentation of a slightly revised version. For

years it was performed more frequently in

Europe than in America where it was considered

a true American opera. More recently, Porgy

and Bess received its first uncut production in

Houston in 1976 to great acclaim, and its first

production at the Metropolitan Opera took

place in the 1980s.

I

ra Gershwin once described his brother’s

imagination as “the reservoir

of musical inventiveness, resourcefulness, and

craftsmanship”: George Gershwin continually

dipped into that “reservoir,” and the result

became a prodigious flow of musical

inventiveness and inspiration.

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess bears a unique

companionship with the Jerome Kern-Oscar

Hammerstein Broadway phenomenon, Show

Boat (1927): together, they represent an integral

part of the history of modern musical theater.

Show Boat, adapted from the Edna Ferber novel,

was innovative, fresh, and daring: it portrayed

themes of racism, marital strife, and

psychological destruction. Its songs and music

evolve magnificently from character and plot,

and the entire musical revolves around the

metaphor of the Mississippi River: the river

stands for time and possesses the power to heal

the characters’ wounds.

As a music drama, Porgy and Bess contains

sweep and power. Its music is infused with

remarkable melodic variety: some of its songs

have become engraved into our collective

memories; the lullaby Summertime, Serena’s

lament My man’s gone now, Porgy’s I got

plenty o’ nuttin, and the love duet Bess, you is

Porgy and Bess Page 26

my woman. And if tension and conflict define

the essence of dramatic opera, Gershwin

provides music drama in the battle between

Crown and Robbins, their savage fight

underscored by a portentous fugue. These

musical creations stand alone in their sheer

beauty, but make a more profound impact when

heard in their full dramatic context on the opera

stage.

Gershwin identifies the Catfish Row

community with a rich musical portrait: there

are no plagiarized “spirituals,” but rather,

original creations that seem authentic: the

lyrical exaltation of Leavin the Promised Land,

the consolation of Clara, Clara, the stark

desolation of Gone, gone, gone, and the prayer

Oh, Doctor Jesus.

In the Kittiwah Island scene, the amoral

Sportin’ Life sermonizes the community who

have been softened up by a day of aimless

carousing: they join him as he mocks bible

teaching with cynicism, all sung in a gospel-

like interplay that is deeply imbedded with a

traditional blues musical vocabulary, It ain’t

necessarily so.

Catfish Row’s uninhibited social mores and

values are glimpsed in the opening ragtime of

the Jazzbo Brown scene, the fisherman Jake’s

bemused commentary on femininity, A woman

is a sometime thing, and the seemingly barbaric

episode complete with vocal outbursts and

tom-tom rhythms during the Kittiwah Island

picnic: I ain’ got no shame.

Finally, Gershwin tapped his reservoir of

genius in the dramatic passages in the Bess-

Crown confrontation on Kittiwah Island. Bess,

on the edge of desperation, pleads with Crown

to take another lover and allow her to return to

Porgy. Bess, wanton, dissolute, and lacking a

true moral compass, stands in conflict: she

cannot resolve her love for the upright Porgy

with her lust for the formidable Crown: a subtle

friction of reason and emotion. And when

Porgy and Bess Page 27

Bess’s good intentions collapse, her defeat is

expressed in her confession, the opera’s most

anguished music: What you want wid Bess?

P

orgy and Bess has been haunted from

its very beginnings by critics

and public alike who have been searching to

provide the work with a musical theater

pedigree: it is a continuing argument that has

made the work contentious and controversial;

Is Porgy and Bess an opera?

Is Porgy and Bess a Broadway musical?

From the very beginning, Gershwin himself

fed the controversy and invited the hounds.

During its composition, a news release from

Charleston reported that Gershwin had labeled

his new Porgy and Bess a “folk opera,” and

promised that if the opera turned out as he

hoped, it would “resemble a combination of the

drama and romance of Carmen, and the beauty

of Meistersinger, if you can imagine that.”

The word opera has its etymological roots

in Latin: it designates an art form that

incorporates words and music to drive its story.

Opera is a “sung play”: it can be dramatic when

it contains conflict and tension, or when it is

comic or lighter in theme; it is opera buffa,

comic opera, operetta, or musical comedy.

When words and music are presented without a

story continuity, they are generally considered

“revues” or “vaudeville.”

“Serious” opera, in its ultimate

manifestation has become idealized as “music

drama,” implying a perfect integration and

organic unity of text and music. The composer

of opera, or “music drama,” through his music,

becomes the “dramatist” and “narrator” of the

story, similar to the role of the cinema director

with his camera, or the choreographer in ballet;

composer, movie director, and choreographer

are all the dramatists of their story.

Porgy and Bess is opera: it is indeed a fully

sung play whose structure incorporates opera’s

inherent techniques such as song, or arias, duets

Porgy and Bess Page 28

and ensembles, sung recitatives that provide

action and link its songs, and leitmotif themes

that provide reminiscence, or identify ideas or

characters. In Porgy and Bess, the lullaby,

Summertime, appears almost as a leitmotif that

ironically seems to presage violence: it appears

during the crap game that ends with Crown

killing Jake Robbins; during the hurricane that

ends with the deaths of the baby’s father and

mother “with Daddy an’ Mammy standin’ by,”;

and by Bess when she sings to the orphaned baby

just before Porgy kills Crown.

“Folk,” by definition, refers to a specific

group of people within a culture, society, or

region. Gershwin originally called Porgy and

Bess a “folk opera,” but later, after much

criticism and reaction, he carefully avoided that

designation. Nevertheless, he had invoked the

“folk” label amid the Great Depression, years

when there arose a growing social awareness

and consciousness of different cultures within

the great American “melting pot,” and the

economically disadvantaged were recognized:

Porgy and Bess was composed during the

1930s when American social experiments were

beginning.

Gershwin, the creator of a “folk” work,

placed himself in the line of fire: he was

vulnerable, and was even deemed presumptuous.

The creative team was questioned and their

credentials were doubted: this was a story about

underprivileged southern blacks that was written

by a white novelist, and set to music by a New

York-based Jewish songwriter-lyricist team;

they were all considered “outsiders” who had

neither the right, insight, nor understanding to

bring this story to the public with authenticity.

Nevertheless, Gershwin intuitively understood

the African-American experience: he was

articulate in expressing their culture within the

framework of his musical vocabulary.

Ironically, Porgy contains no folk tunes, and

perhaps the only “folksiness” remains a few

street cries from the “honeyman,” “strawberry

Porgy and Bess Page 29

girl,” and residents of Catfish Row.

Is Porgy and Bess an opera or a musical? It

did premiere on Broadway rather than at an

opera house, but that fact does not contribute

to determining its specific genre.

By 1935, Gershwin had become the

supreme master of the American popular song.

He composed during the “Golden Age” of

American popular songs, a specific style of song

that had begun in 1914 with Jerome Kern, Irving

Berlin, Harold Arlen, Cole Porter, and

flourished for some 50 years afterwards with

the music of Richard Rodgers, Leonard

Bernstein, and Frank Loesser.

The American popular song of that era

possessed a very special “musicality”: it had its

own unique character, powerful lyrics, and

poignant music that was always intimate,

sophisticated, and graceful in its expression of

emotion and sentiment. Generally, those early

20

th

century songs broke with the earlier

traditions of Stephen Foster and the extravagant

opera/operetta traditions inherited from

Europe. American songs did not seek climax in

vocal virtuosity: their musical lines usually

inhabited a one-octave range whereas the vocal

lines of opera and operetta generally would

reach two or more octaves to achieve emotional

climax. And with rare exceptions, American

songs always followed a 32-bar structure in

which tension is heightened when the main

theme is repeated after the bridge.

The American musical theater – the

“Broadway musical” - developed from its own

indigenous character and not from European

styles. There were revues and vaudevilles, but

as the Broadway musical developed from the

1880s to the 1920s, it used a diversity of its

own American elements, song styles, and

performing traditions: melodrama, minstrel,

Negro spiritual, ballad, ragtime, and jazz. Many

of them became worthy of the operatic stage,

like the Kern-Hammerstein Show Boat (1927),

Porgy and Bess Page 30

Broadway’s first attempt to tell a profound and

complex story with music that dramatized racial

inequalities on the American stage.

Gershwin was a master of that particular

American song style. His outpouring of songs

for Porgy and Bess contain what American

songs do best: they are fine melodies,

ingeniously harmonized, orchestrated with great

skill, and their strength lies in the dramatic

effectiveness of their direct communication of

emotion: all of Gershwin’s music is typically

American; it is indigenous music.

Porgy and Bess portrays a very human

drama: all of its characters are multi-

dimensional and convey a profound depth of

feeling. Whether Porgy and Bess is “sung

drama,” “opera,” or “Broadway musical,” it is,

nevertheless, a sensitive story about human lives

with its music adding that special emotive power

to its text.

Words have the power to stimulate thought:

music has the power to make one feel. Porgy

and Bess, a music drama, or drama with music,

portrays the conflicts and tensions of in the

human drama for survival. Gershwin portrays

this heartfelt drama with musical radiance:

Porgy is American, an earthy drama which glows

with the rich colors of American life. And, the

score contains that special Gershwin trademark

of “singable” and “hummable” melodies:

American music that appeals strongly to the

“man in the street,” composed in that very

specific American musical idiom.

Gershwin’s entire music career was marked

by a substantial stake in African-American

music: Porgy became his destiny: his ultimate

musical vision. He devoted the better part of

two years to this single work, the fulfillment

of which was his own idea. In the end, it became

his magnum opus, the work he was aspiring to,

and yearning to create throughout his entire

career.

Folk opera? Opera? Broadway musical?

Porgy and Bess represents great American

Porgy and Bess Page 31

musical theater: it is a drama about human

suffering, about hope and aspirations, the

yearning for love, and the fulfillment of love.

The underlying conflicts and tensions within its

story represent the struggles of all humanity,

irrespective of race, culture, or ethnicity.

Gershwin, the dramatist of this story, narrates

its poignancy through the emotive power of his

wondrous musical inventions.

Porgy and Bess Page 32

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

(L)Nuty George Gershwin Summertime (Piano & Voice Porgy And Bess)

340 George Gershwin Bess You Is My Woman

339 George Gershwin I Loves You Porgy

George Gershwin I Loves You Porgy

I got rhythm (George Gershwin) G

george gershwin summertime

The Dragon and the George Gordon R Dickson

Gordon Dickson Dragon 01 The Dragon and the George (v1 3)

342 George Gershwin It Aint Necessarily So

George Gershwin Summertime

George Gershwin It Aint Necessarily So

George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue

George Gershwin Promenade

George Gershwin Summertime

From MajorJordan s Diaries The Truth About The US And USSR George R Jordan & Richard L Stokes

George Gershwin I Got Plenty O Nuttin

341 George Gershwin I Got Plenty O Nuttin

george gershwin

więcej podobnych podstron