Topics in Medicine and Surgery

Topics in Medicine and Surgery

Clinical Approaches to Analgesia in Ferrets

and Rabbits

Matthew S. Johnston, VMD, DABVP (Avian)

Abstract

Pet rabbits and ferrets are increasingly presented to veterinarians, and new de-

mands are placed on veterinarians to manage pain in these species. Relatively little

data exist regarding the efficacy of analgesics in these animals. Rabbits and ferrets

exhibit different behavioral and physiological responses to pain, and an under-

standing of the normal behavior of these species is critical to pain assessment.

Although acute pain is relatively easy to identify, signs of chronic pain may be more

subtle. Occasionally, simple husbandry corrections can help alleviate painful

chronic conditions. The prevention of pain by minimizing tissue trauma with a

gentle surgical technique and preemptive analgesia is critical when dealing with

rabbits and ferrets in the clinical setting. Many of the same analgesic techniques

and drugs used in dogs and cats can be extrapolated to rabbits and ferrets, though

some of the drugs have specific indications and contraindications. Discussions of

the clinical use of opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, local anesthetics,

ketamine, and tramadol in rabbits and ferrets are presented. Reference to the

current literature is made where possible. In addition, insights gained from the

author’s experience with the clinical use of these drugs in rabbits and ferrets are

presented. Copyright 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Key words: Rabbit; ferret; pain; analgesia; opioids; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs); ketamine; tramadol

O

ver the past 10 to 15 years, the standard of

care for the treatment of small and exotic

mammals has increased. Parallel to this has

been a significant increase in attention to veterinary

pain management in both the clinical and research

arenas. Unfortunately, there are a limited number of

publications addressing pain management strategies

in pet small mammals, such as rabbits and ferrets.

Much of the literature addressing pain and its man-

agement in rabbits and ferrets originates from the

realm of laboratory animal medicine. However, as

rabbit and ferret ownership increases, veterinarians

are being asked to provide the quality of care af-

forded to more traditional pet species.

There are several excellent reviews on analgesia in

small mammals.

However, none of these reviews

focus on rabbits and ferrets, and none are written

from the standpoint of these animals as pet species.

The goal of this article is to present a clinical ap-

proach to pain management in ferrets and rabbits.

From the James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Colorado

State University, 300 West Drake Road, Fort Collins, CO 80523

USA

Address correspondence to: Matthew S. Johnston, VMD,

DABVP (Avian), Assistant Professor of Zoological Medicine,

James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Colorado State Uni-

versity, 300 West Drake Road, Fort Collins, CO 80523 USA.

E-mail: msjohn@lamar.colostate.edu

© 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1055-937X/05/1404-$30.00

doi:10.1053/j.saep.2005.09.003

Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine, Vol 14, No 4 (October), 2005: pp 229 –235

229

Wherever possible, reference to the published liter-

ature will be presented; however, because of the

paucity of such information, much of the informa-

tion presented here will be drawn from the author’s

own experience in treating pain in rabbits and fer-

rets.

Recognition of Pain

In some circumstances, it is not difficult to recognize

when a rabbit or ferret is in pain. Stimuli, such as

surgery or tissue trauma, that cause pain in other

animals are assumed to cause pain in these species as

well. Though this concept seems simple, in a survey

of British veterinarians published in 1999, only 22%

of veterinarians administered some form of analge-

sia to small mammals in the perioperative period.

Additionally, veterinary surgeons were more likely to

administer analgesics to rabbits than to ferrets.

Though surgical pain should be easy to identify,

some stimuli that cause pain in ferrets and rabbits

are more difficult to recognize, and an understand-

ing of the unique physiology and behaviors is impor-

tant. Adequate pain management is complicated by

the fact that many veterinarians who are presented

only occasionally with rabbits or ferrets are unfamil-

iar with the behavioral subtleties of these animals.

Ferrets and rabbits could not be any more differ-

ent from a physiological and behavioral standpoint.

Ferrets are strict carnivores and predators. They are

often boisterous and gregarious, even when in an

unfamiliar environment such as a veterinary hospi-

tal. Rabbits, on the other hand, are a strictly herbiv-

orous prey species. Behaviorally, they are generally

quiet, reserved, and can be quite anxious when in an

unfamiliar territory. Familiarity with the normal be-

haviors of ferrets and rabbits will help the practitio-

ner gain insight into the abnormal behaviors associ-

ated with pain. It is important to note that some of

behavioral abnormalities associated with pain states

may not be specific for pain. Rather, they may also be

observed with other disease processes and should be

used as part of the clinical assessment of an animal,

rather than being used as sole indicators of pain.

Pain-related behaviors in ferrets include prefer-

ring inactivity, staying curled in a ball, and exhibiting

aggressive biting behavior or teeth-bearing when dis-

turbed. Ferrets with visceral pain may have a de-

creased appetite and may demonstrate bruxism

when presented with food. Inadequate postoperative

analgesia in a ferret may be associated with shivering

in the presence of a normal body temperature.

Other signs of pain in ferrets include a bristling of

the tail fur, so that the tail resembles a pipe cleaner,

half-closed eyelids, focal muscle fasciculations, high

pitched-vocalization or grunting when handled,

lameness, and general malaise.

The most easily identified behavioral indicator of

pain in rabbits is anorexia. Rabbits are normally

grazing animals that eat continuously. In the pres-

ence of pain, this behavior ceases. Painful rabbits will

also grind their teeth, especially when visceral or

dental pain is present. Though most rabbits in pain

will choose to sit motionless in a far corner of a cage,

some may demonstrate periods of rapid and uncon-

trolled locomotion and struggling when handled.

Painful rabbits may vocalize or exhibit a decreased

respiratory rate that is characterized by a pro-

nounced nasal flare and deep breathing pattern.

This is in contrast to the very rapid respiratory pat-

tern, characterized by short, shallow breaths seen in

nonpainful rabbits. The painful rabbit appears un-

kempt because of a lack of grooming and may avoid

rearing up on its hind legs to accept treat items, if

this is part of its normal behavioral repertoire. Epi-

phora and serous nasal discharge are sometimes

present in rabbits that are experiencing severe, acute

pain.

Acute and Chronic Pain

As with individual animals of more common pet

species, it is generally easier to recognize the signs of

acute, rather than chronic, pain in ferrets and rab-

bits. It is important to note that acute pain can arise

in conditions that do not involve surgical or trau-

matic pain. Thus, attention to the need for analgesia

should be provided in these cases. As an example,

otitis interna is an acute infectious/inflammatory

medical condition that is common in rabbits. This

condition is associated with significant inflammation

and, as such, is likely responsible for clinically signif-

icant pain. Although some may ignore the analgesic

needs of rabbits with this condition, it is the author’s

experience that rabbits with this condition benefit

clinically from the administration of analgesic drugs,

specifically nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs). In rabbits, ileus leads to gastric and cecal

dilation, which activates nociceptive fibers associated

with the stretch receptors in the gastrointestinal

tract. A similar pain pathophysiology occurs in fer-

rets with gastrointestinal foreign bodies or tricho-

bezoars. Both conditions lead to acute abdominal

pain, and appropriate treatment is indicated when

these conditions are diagnosed. In rabbits, several

opioids decrease painful behaviors after colorectal

distention,

suggesting that drugs of this class are

useful for managing pain associated with disease

230

Johnston

processes that involved distension of the gastrointes-

tinal tract.

Conditions that lead to chronic pain are more

difficult to recognize in ferrets and rabbits. Behav-

ioral changes indicative of chronic pain can be ob-

tained from a thorough history provided by the care-

taker. Neoplasia, arthritis, and dental problems are

three very common causes of chronic pain in ferrets

and rabbits. Though some of these conditions can-

not be cured, the quality of life of the pet can be

greatly increased when analgesia is provided. The

alleviation of pain can often be provided by correct-

ing inappropriate husbandry, making pharmaco-

logic intervention unnecessary. For example, geriat-

ric rabbits with stifle and coxofemoral arthritis may

benefit from a heavily bedded cage, whereas ferrets

with chronic periodontitis may be kept comfortable

when eating soft, as opposed to hard, solid food.

Prevention of Pain

Attention to gentle surgical technique can lead to a

reduction in tissue trauma and associated inflamma-

tion that will result in reduced activation of the

nociceptive (pain) pathways. The physiologic pro-

cesses underlying nociception are initiated with tis-

sue damage regardless of whether an animal is anes-

thetized. General anesthesia does not eliminate the

neuronal processes in the peripheral and central

nervous systems (CNS) responsible for pain. Nox-

ious surgical stimulation can lead to CNS changes

that are exhibited as painful behaviors on recovery

from anesthesia.

In general, the “preemptive” administration of

analgesics is associated with more successful pain

management than administration of analgesics in

response to pain.

In addition, the preemptive or

presurgical administration of analgesics generally re-

duces requirements for general anesthesia during

the surgical procedure. For these reasons, preemp-

tive analgesia should be a part of the anesthetic

regimen for all rabbits and ferrets undergoing pro-

cedures that may lead to postoperative pain.

Analgesics and Their Application in

Ferrets and Rabbits

presents a summary of the dosages of anal-

gesics used in rabbits and ferrets.

Opioids

The use of opioids remains a major component of

analgesic therapy, particularly in the treatment of

moderate to severe acute, postsurgical, or traumatic

pain. Opioids exert their effect by inhibiting the

transmission of nociceptive (pain) stimulation in the

dorsal horn of the spinal cord, activating descending

inhibitory pathways, inhibiting supraspinal afferents,

and causing a decrease in the release of neurotrans-

mitters in the spinal cord.

Opioids commonly used

in ferrets and rabbits include butorphanol, bu-

prenorphine, morphine, hydromorphone, oxymor-

phone, and fentanyl.

Although some practitioners are wary of adminis-

tering this class of drugs because of the potential for

adverse side effects such as sedation, respiratory de-

pression, and ileus, the beneficial analgesic proper-

ties of these drugs, in the majority of cases, far out-

weigh the potential for the development of these

adverse effects. In the author’s experience, ferrets

are especially sensitive to the sedative and respiratory

depressant effects of opioids, which suggest that the

lower end of dosage ranges and careful monitoring

be used with this species when administering opi-

oids. Opioid-induced ileus in rabbits is of particular

concern; however, pain-induced ileus is much more

difficult to treat than that associated with the admin-

istration of opioids. Usually, the institution of force

feedings and adequate fluid therapy is enough to

counteract the reduction in motility that is observed

after the administration of an opioid. In addition,

different opioids have differing effects on gastroin-

testinal motility, providing the practitioner with the

option of selecting an opioid that carries with it a low

risk of producing ileus, should this be of concern.

Opioids are classified as mixed agonist-antago-

nists, partial agonists, pure agonists, and pure antag-

onists. Pure antagonists will not be discussed here,

because they are used primarily to reverse agonist

activity and have no inherent analgesic properties.

Three different classes of opioid receptors are rec-

ognized:

, , ␦. The receptors are further subdi-

vided into

-1, -2, and -3 subgroups. In mammals,

-1 and receptors are the primary receptors re-

sponsible for analgesia.

The most commonly used mixed agonist-antago-

nists are butorphanol and buprenorphine. Butor-

phanol has agonistic effects mainly at

receptors,

with minimal to no

effects, hence its classification

as a

The pharmacokinetics of butor-

phanol in rabbits has been described. A 0.5 mg/kg

dosage administered intravenously is associated with

a half-life of elimination of 1.5 hours. The same

dosage administered subcutaneously has a half-life of

elimination of just over 3 hours.

The pharmacoki-

netics of butorphanol in ferrets have not been de-

termined. Butorphanol is suitable for the treatment

Analgesia in Ferrets and Rabbits

231

of mild to moderate pain in rabbits, but the fre-

quency of administration makes it impractical for

many situations. The author uses this drug primarily

for its sedative effects in ferrets, because the analge-

sic effects seem limited in this species.

Buprenorphine is classified as a partial

agonist

and

antagonist. It binds strongly to the receptors

and, because of this, can be difficult to reverse.

For

this reason, the author does not like to use bu-

prenorphine preoperatively. Buprenorphine, like

butorphanol, is suitable for management of mild to

moderate pain. Unlike butorphanol, the analgesic

effects of buprenorphine seem to last quite a bit

longer, though the pharmacokinetics in ferrets or

rabbits are not known. Clinically, the analgesic ef-

fects appear to persist for 6 to 10 hours after subcu-

taneous administration to both rabbits and ferrets. It

has been suggested that behaviors attributed to pain

in rabbits are not diminished after the administra-

tion of buprenorphine.

Transmucosal absorption of

buprenorphine occurs in cats,

and the author has

successfully used this route of administration in fer-

rets. Transmucosal absorption of buprenorphine de-

pends on the pH of the saliva, suggesting that ani-

mals with similar digestive physiologies (cats and

ferrets), and hence oral pH, should respond simi-

larly.

Morphine is the prototypic opioid to which all other

opioids are compared. It is very inexpensive and is

often the sole opioid administered in veterinary prac-

tices.

The author rarely administers morphine system-

ically, other than as a premedicant to rabbits and fer-

rets. This is largely because of the large array of poten-

tial side effects, especially respiratory depression in

ferrets and induction of ileus in rabbits. However, epi-

durally administered morphine can be an excellent

way to provide analgesia for abdominal and hind limb

procedures in both species. Epidural or spinal mor-

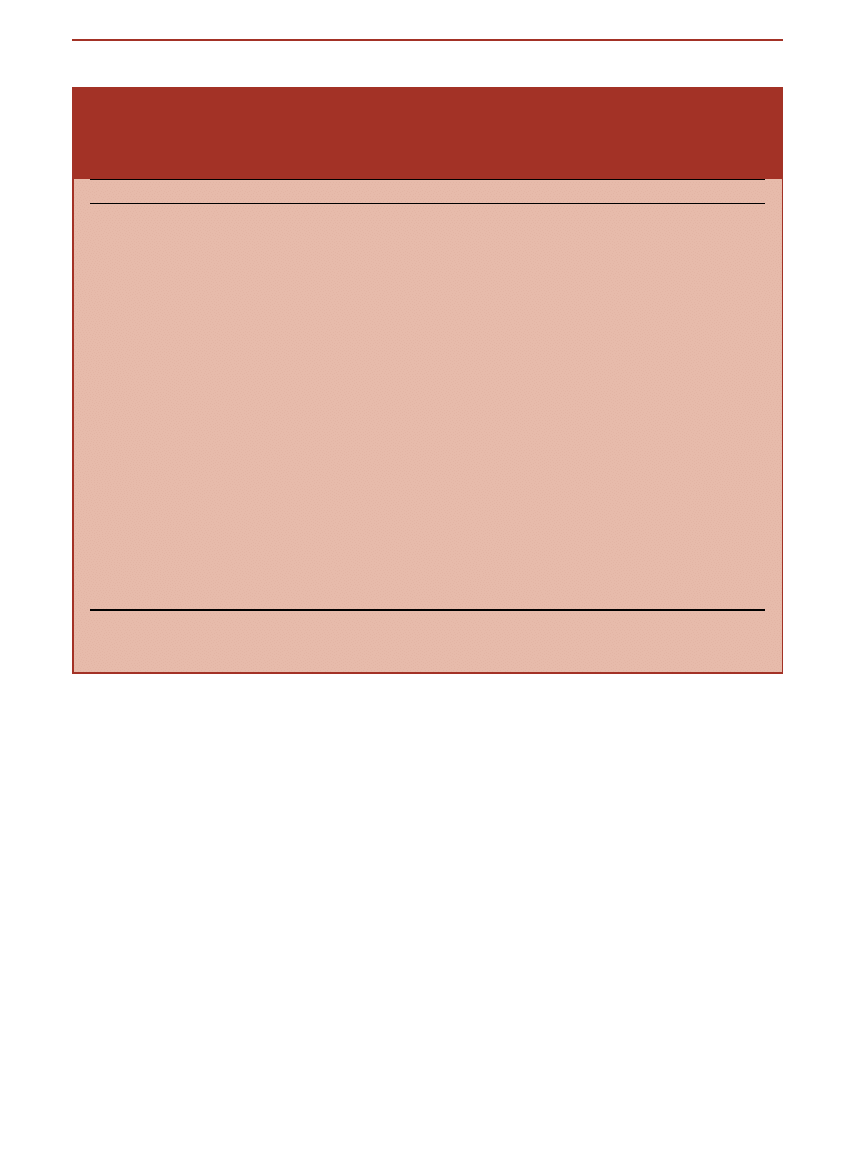

Table 1. Dosages of Analgesic Drugs for Ferrets and Rabbits. (Note that many of these

dosages are based on clinical experience and extrapolation of published dosages for other

species. It is the responsibility of the attending veterinarian to monitor for adverse effects

associated with administration of these drugs.)

Drug

Ferret

Rabbit

Butorphanol

0.1-0.4 mg/kg q2-4h IV, IM, SC

0.5 mg/kg q2-4h IV, SC

0.1-0.2 mg/kg/hr IV CRI*

Buprenorphine

0.01-0.03 mg/kg q6-10h IV, SC, TM†

0.01-0.05 mg/kg q 6-10h IV, SC

Morphine

0.2-2 mg/kg IM single dose

preoperatively

0.5-5 mg/kg IM single dose preoperatively

0.1 mg/kg epidurally

0.1 mg/kg epidurally

Hydromorphone

0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q6-8h

0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q6-8h

Oxymorphone

0.05-0.2 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q6-8h

0.05-0.2 mg/kg IV, IM, SC q6-8h

Fentanyl

20-30

g/kg/hr IV CRI* during

anesthesia to reduce volatile

inhalant concentrations

Not recommended because of induction of

severe ileus

1-4

g/kg/hr IV CRI* for analgesia

Meloxicam

0.1-0.2 mg/kg SC, PO q24h

0.1-0.5 mg/kg q12-24h SC, PO

Lidocaine

⬍2 mg/kg SC

⬍2 mg/kg SC

4.4 mg/kg epidurally

Bupivicaine

⬍1.5 mg/kg SC

⬍1.5 mg/kg SC

1.1 mg/kg epidurally

Ketamine (analgesic)

0.5 mg/kg IV before surgery

0.5 mg/kg IV before surgery

10

g/kg/min IV CRI* during surgery

10

g/kg/min IV CRI* during surgery

2

g/kg/min IV CRI* for 24 hours

postoperatively‡

2

g/kg/min IV CRI* for 24 hours

postoperatively‡

Tramadol

No dose available

10 mg/kg PO q24h

*Constant rate infusion.

†Transmucosally—administer directly into space between molars and buccal mucosa.

‡Must be combined with an additional analgesic agent such as an opioid to provide adequate analgesia.

232

Johnston

phine is known to attenuate postoperative pain re-

sponses in ferrets and rabbits.

For more complete

and immediate analgesia, a local anesthetic such as

lidocaine or bupivicaine may be combined with the

morphine and administered epidurally. The analgesic

effects of epidurally administered morphine last ap-

proximately 12 to 24 hours. The dosage of morphine

administered epidurally is much lower than the dose

required for systemic administration. Thus, the adverse

effects associated with systemic administration are vir-

tually eliminated.

The procedure for lumbosacral epidural punc-

ture in ferrets and rabbits is similar to that described

for dogs and cats,

except that there is rarely a

definitive “popping” sensation when the interverte-

bral ligaments are punctured and the epidural space

is entered. In rabbits, the spinal cord continues cau-

dally into the sacral vertebrae, so the potential for

accidental puncture of both the dura and arachnoid

membranes during lumbosacral epidural injection is

higher.

In this situation, cerebrospinal fluid is seen

in the hub of the needle, and half of the volume of

drug that was intended for epidural administration

should be administered. This reduction in the

amount of administered drug reflects the need for a

larger dosage of drug during epidural administra-

tion because of the significant uptake of drug from

the epidural space before it diffuses into the sub-

arachnoid space. This has not been a clinical prob-

lem in the author’s experience with ferret epidural

injections (

Hydromorphone and oxymorphone are very sim-

ilar opioids. Currently, hydromorphone is signifi-

cantly less expensive than oxymorphone, so it is used

more frequently in veterinary practice. The analgesic

effects of both are similar to morphine, but both

have the advantage of fewer negative side effects.

Both drugs have been used extensively by the author

in both ferrets and rabbits, with few negative side

effects. With the exception of anecdotal clinic re-

ports, there are no data describing the pharmacoki-

netics of either drug in either species.

Both hydromorphone and oxymorphone can be

used as premedicants to provide preemptive analge-

sia, postoperatively to manage moderate to severe

pain, or as primary analgesics after trauma or in the

treatment of painful medical conditions. In ferrets,

both drugs do cause profound sedation, making as-

sessment of analgesia difficult. In both ferrets and

rabbits, subcutaneous injection appears to provide

approximately 6 hours of analgesia.

Fentanyl is a very short-acting, potent pure

ag-

onist with analgesic effects similar to morphine. The

effects of fentanyl last less than 30 minutes after a

single intravenous injection.

Fentanyl is used in fer-

rets by the author both intraoperatively as a constant

rate infusion (CRI) to decrease the requirement for

inhaled anesthetics and as a CRI to provide analgesia

for moderate to severe pain. A fentanyl CRI is the

author’s treatment of choice in the provision of

postoperative analgesia in ferrets. Fentanyl can also

be administered with a transdermal delivery system

(fentanyl patch). This mode of delivery has been

evaluated in rabbits. Although therapeutic plasma

concentrations are obtained with a 25-

g/hour

patch, loss of body weight does occur.

This obser-

vation correlates with the author’s experience with

either transdermal or intravenous administration of

fentanyl in rabbits. Rabbits receiving fentanyl have a

severely decreased appetite, and the management of

fentanyl-induced ileus is challenging. For these rea-

sons, the use of fentanyl in rabbits cannot be recom-

mended.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs have anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anti-

pyretic effects. Because they are effective for both

acute and chronic pain and have relatively few side

effects, NSAIDs are the most commonly used anal-

gesics in veterinary medicine. NSAIDs exert their

analgesic effects by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxy-

genase, leading to a reduction in tissue inflamma-

tion and an increase in the threshold of activation of

peripheral nociceptors.

It should be noted that

no safety or efficacy studies are available for any

NSAIDs in either rabbits or ferrets, so most of our

knowledge of these drugs is based on clinical expe-

rience and extrapolation of knowledge gained from

other species. NSAIDs are contraindicated in ferrets

or rabbits that are pregnant, have hepatic or renal

Figure 1.

Epidural injection in a ferret. Note the flexed position of

the hind legs which allows for maximal opening of the lumbosacral

space.

Analgesia in Ferrets and Rabbits

233

dysfunction, have known gastrointestinal ulceration,

or are in shock or have other conditions limiting

organ perfusion.

Many NSAIDs have been used in rabbits and fer-

rets throughout the past 10 to 15 years. Today, the

most commonly used NSAID for analgesia in rabbits

or ferrets is meloxicam. This increase in the use of

meloxicam is primarily a result of its relative safety,

ease of administration, and apparent effectiveness.

Meloxicam is a cyclooxygenase-2 selective NSAID.

Cyclooxygenase-2 selective NSAIDs have fewer side

effects that are usually gastrointestinal in origin

when they are observed. It is available as a palatable

liquid 1.5-mg/mL solution (Metacam; Boehringer

Ingelheim, St. Joseph, MO) that is readily accepted

by ferrets and rabbits. Owing to the apparent sensi-

tivity of ferrets to certain NSAIDs, caution should be

used with long-term administration of meloxicam.

Clinical experience suggests that meloxicam is safe

to use for short-term administration. Any ferret or

rabbit on a long-term NSAID regimen should have

plasma liver enzymes, blood urea nitrogen, and cre-

atinine levels monitored periodically to ensure that

toxicosis is not occurring. Rabbits seem to tolerate

NSAIDs and meloxicam, in particular, very well. The

author has personally used meloxicam in numerous

rabbits with chronic painful conditions (dental root

overgrowth, arthritis, neoplasia) for long periods of

time at doses higher than that for dogs with apparent

clinical efficacy and no changes in plasma biochem-

istry values or gastrointestinal signs. However, until

further studies on safety and efficacy are performed,

it remains prudent to use the lowest possible clini-

cally effective dose.

Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics such as lidocaine and bupivicaine

are also commonly used in veterinary practice. Local

anesthetics provide regional anesthesia by reversibly

blocking the transmission of nociceptive stimulation

from nerve endings or fibers. Local anesthetics can

be used topically, via direct infiltration into soft tis-

sue containing nerve endings, intra-articularly (not

practical in ferrets or rabbits), intravenously, or epi-

durally.

Care must be taken to avoid the adminis-

tration of toxic dosages of these drugs when they are

used to treat small animals such as rabbits or ferrets.

During subcutaneous administration of a local anes-

thetic, one should always aspirate to ensure that the

drug will not be accidentally administered intrave-

nously. Practically, for bupivicaine and lidocaine, the

author always administers less than 1.5 and 2 mg/kg

respectively, to avoid toxicosis. When used epi-

durally, bupivicaine may lead to motor weakness in

the hind limbs for up to 12 hours postinjection. This

motor weakness can be agitating to rabbits and may

lead to increased postoperative morbidity. For this

reason, the author uses bupivicaine epidurally in

ferrets only. One of the author’s preferred uses for

local anesthetics is as a line block before surgical

incisions. For abdominal procedures, a 2.5-in, 22-

gauge spinal needle with the stylet removed is used

to infiltrate the subcutaneous tissue with lidocaine

before incision. Care should be taken not to acci-

dentally puncture the abdominal wall and viscera

when performing this technique.

Ketamine

Ketamine is known primarily for its sedative proper-

ties. Ketamine is used frequently by the author in

both ferrets and rabbits as a premedication. Re-

cently, the administration of a ketamine CRI has

been used to augment intraoperative and postoper-

ative analgesia. Ketamine has been shown to act as

an analgesic by antagonism of the excitatory N-

methyl-D-aspartate receptors in the CNS. N-methyl-

D-aspartate stimulation has been shown to mediate

central sensitization of the CNS.

This activity of

ketamine has not been confirmed in either rabbits

or ferrets, suggesting that ketamine alone is not an

acceptable analgesic in most instances. However, a

ketamine CRI may allow a lower dosage of an opioid

or other analgesic to be administered.

Tramadol

Tramadol has recently become popular in veterinary

medicine as an analgesic agent for treatment of mild

to severe chronic pain. Its popularity stems from the

fact that it is efficacious in certain circumstances, is

not controlled, and is very cost-effective. The mech-

anisms of action of tramadol are not completely

understood, but it does appear to have both opioid-

like properties as well as serotonin and norepineph-

rine reuptake inhibition.

Though its use in ferrets

and rabbits is not described in the published litera-

ture, the author has used tramadol with apparent

clinical efficacy in rabbits with osteoarthritis for

which NSAIDs are not a good option. It should be

noted, however, that tramadol is extremely unpalat-

able when compounded, so strong flavoring agents

should be used to maximize acceptance of the drug.

Ideally, practicing veterinarians should work with a

licensed compounding pharmacist to find the flavor

combination that works well. The author has had

good luck with suspension of crushed tablets in an

oral compounding agent flavored with nonalcoholic

piña colada mix. The use of tramadol in ferrets has

not been reported or evaluated.

234

Johnston

Conclusions

Clearly, much work remains to assess the efficacy of

existing analgesics in rabbits and ferrets. Some of the

impetus for this work will come as rabbit and ferret

ownership increases and veterinarians are called on to

consider the analgesic requirements of individual ani-

mals placed in their care. Until this species-specific

knowledge is obtained, the practicing veterinarian is

encouraged to pay heed to the treatment of pain in

these species, attend to behavioral signs of pain, and

use the knowledge we have gained from other species

in the establishment of pain management strategies.

References

1.

Flecknell PA: Analgesia of small mammals. Vet Clin

North Am Exot Anim Pract 4:47-56, 2001

2.

Flecknell PA: Analgesia in small mammals. Semin

Avian Exot Pet Med 7:41-47, 1998

3.

Flecknell PA: Pain relief in laboratory animals. Lab

Anim 18:147-160, 1984

4.

Lascelles BDX, Capner CA, Waterman-Pearson AE:

Current British veterinary attitudes to perioperative

analgesia for cats and small mammals. Vet Rec 145:

601-604, 1999

5.

Borgbjerg FM, Frigast C, Madsen JB, et al: The effect

of intrathecal opioid-receptor agonists on visceral

noxious stimulation in rabbits. Gastroenterology 110:

139-146, 1996

6.

Muir WW: Physiology and pathophysiology of pain,

in Gaynor JS, Muir WW (eds): Handbook of Veteri-

nary Pain Management. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp

13-45

7.

Wagner AE: Opioids, in Gaynor JS, Muir WW (eds):

Handbook of Veterinary Pain Management. St.

Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp 164-183

8.

Portnoy LG, Hustead DR: Pharmacokinetics of bu-

torphanol tartrate in rabbits. Am J Vet Res 53:541-

543, 1992

9.

Robinson AJ, Muller WJ, Braid AL, et al: The effect of

buprenorphine on the course of disease in labora-

tory rabbits infected with myxoma virus. Lab Anim

33:252-257, 1999

10.

Robertson SA, Taylor PM, Sear JW: Systemic uptake

of buprenorphine by cats after oral mucosal admin-

istration. Vet Rec 152:675-678, 2003

11.

Sladky KK, Horne WA, Goodrowe KL, et al: Evalua-

tion of epidural morphine for postoperative analge-

sia in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Contemp Top in

Lab Anim Sci 39:33-38, 2000

12.

Kero P, Thomasson B, Soppi AM: Spinal anaesthesia

in the rabbit. Lab Anim 15:347-348, 1981

13.

Gaynor JS, Mama KR: Local and regional anesthetic

techniques for alleviation of perioperative pain, in

Gaynor JS, Muir WW (eds): Handbook of Veterinary

Pain Management. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp

261-280

14.

Greenaway JB, Partlow GD, Gonsholt NL, et al: Anat-

omy of the lumbosacral spinal cord of rabbits. J Am

Anim Hosp Assoc 37:27-34, 2001

15.

Foley PL, Henderson AL, Bissonette EA, et al: Eval-

uation of fentanyl transdermal patches in rabbits:

blood concentrations and physiologic response.

Comp Med 51:239-244, 2001

16.

Budsberg S: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, in

Gaynor JS, Muir WW (eds): Handbook of Veterinary

Pain Management. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp

184-198

17.

Richardson JA, Balabuzsko RA: Ibuprofen ingestion

in ferrets: 43 cases. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 11:53–39,

2001

18.

Mama KR: Local anesthetics, in Gaynor JS, Muir WW

(eds): Handbook of Veterinary Pain Management.

St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp 221-239

19.

Gaynor JS: Other drugs used to treat pain, in Gaynor

JS, Muir WW (eds): Handbook of Veterinary Pain

Management. St. Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp 251-260

Analgesia in Ferrets and Rabbits

235

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Tully Jr 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

[first author] 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

Nevarez 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

[first author] 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 4

Pokras 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

Gunkel 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

Myers 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

Pettifer 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

[first author] 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 1

Mosley 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine

[first author] 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 2

[first author] 2005 Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 3

Suture Materials and Suture Selection for Use in Exotic Pet Surgical

2005 Diet and Age Affect Intestinal Morphology and Large Bowel Fermentative End Product Concentratio

Estimation of Dietary Pb and Cd Intake from Pb and Cd in blood and urine

automating with step 7 in lad and fbd simatic (1)

więcej podobnych podstron