Great expectations: Waterfront

redevelopment and the Hamilton

Harbour Waterfront Trail

Sarah Wakefield

*

Department of Geography, Centre for Urban Health Initiatives, University of Toronto,

100 St. George St. (5th floor), Toronto, Ont., Canada M5S 3G3

Received 15 July 2006; received in revised form 24 October 2006; accepted 5 November 2006

Available online 21 February 2007

This paper examines waterfront revitalization in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Unlike many con-

temporary North American cities, heavy industry continues to dominate the local economy, and

the physical manifestations of this industry (mills, smokestacks, and industrial air and water pol-

lution) remain visible along Hamilton’s harbourfront. Within the last three decades, major

investments in improving the city’s environment – and reputation – have been undertaken within

the city, including the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail, opened to the public in 2000. This

paper uses newspapers and municipal documents to track the development of the Trail, from

the initial planning of the Trail until the present day. These sources suggest that the proposal

and subsequent development of the waterfront trail are linked to broader discourses of environ-

mental and economic revitalization within and beyond the city. In addition, issues of access and

inclusiveness are highlighted. These results draw attention to the ways that waterfront develop-

ment is both locally situated and moulded by broader discourses and trends.

Ó 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Waterfront, harbour redevelopment, urban revitalization, environmental remediation

Introduction: Waterfront redevelopment in

Hamilton, Canada

Throughout the industrial era, the presence of indus-

try in a community was a source of pride, indicating

prosperity and progress (

). To-

day, it is more likely to evoke negative connotations:

To call a city ‘industrial’ in the present period...is to

associate it with a set of negative images: a declining

economic base, pollution, a city on the downward

slide... Industrial cities are associated with the past

and the old, work, pollution and the world of pro-

duction. . . Cities with a more positive imagery are

associated with the post-industrial era. . . the new,

the

future,

the

unpolluted,

consumption

and

exchange, the worlds of leisure as opposed to work

(

)

This transition, grounded in broader economic and

social transformations, has left many industrial cities

scrambling to redefine themselves in order to main-

tain positive local identities (

) and attract investment capital to the city

Hall and Hubbard, 1996, 1998; Short and Kim,

). In an attempt to respond to this

perceived need, city planners and promoters have

increasingly turned to waterfront revitalization pro-

jects (

Harvey, 1989b; Wood and Handley, 1999; Sand-

ercock and Dovey, 2002; Desfor and Jorgensen, 2004

The City of Hamilton, an urban centre of approx-

imately 500,000 people, is located on the shores of

Hamilton Harbour and Lake Ontario only 100 km

from Toronto, Canada. Unlike many other cities in

North America, heavy industry – specifically steel

– continues to play a prominent role in Hamilton’s

economy (

City of Hamilton, 2000; City of Hamil-

), and the mills of the two largest steel

manufacturers, Stelco and Dofasco, are conspicuous

*

Tel.: +1-416-978-3653; e-mail:

Cities, Vol. 24, No. 4, p. 298–310, 2007

Ó 2006 Elsevier Ltd.

All rights reserved.

0264-2751/$ - see front matter

www.elsevier.com/locate/cities

doi:10.1016/j.cities.2006.11.001

298

landmarks on the shores of Hamilton Harbour

(

–

). This ‘‘famously

ugly industrial wasteland’’ (

) developed

between 1800 and 1960, as the original undulating

shoreline was infilled to create new space for indus-

trial development

. This, along with serious water

pollution problems, reduced resident access to –

and interest in – the waterfront (

). In recent decades, pol-

lution control and cleanup efforts have improved

harbour water quality considerably, although the

Harbour remains listed as an ‘‘area of concern’’ un-

der the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (

rup, 1996; Remedial Action Plan for Hamilton

Harbour, 2006a

). The central-east harbour remains

highly industrialised, but by the late 1980’s some

properties in the west harbourfront area were con-

sidered ‘‘underused’’ (

) and

ripe for revitalization.

In 1990, less than five percent of the city’s

waterfront was available for public use. By 2006,

one quarter of that shoreline had been made

accessible to the public, mostly in the western sec-

tion of the harbour (

). One key component

of this increase has been the development of the

Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail. This 3.4 km

long multi-use trail runs along the shoreline be-

tween Cootes Paradise (a nature preserve owned

by the Royal Botanical Gardens) and Bayfront

Park, a large, grassy open space constructed from

a former landfill site for construction waste in

1993 (

–

). The Trail

has recently been extended to connect with other

waterfront attractions, including Pier 4 (another

park) and Pier 8 (home to the new Marine Discov-

ery Centre, a federal museum and interpretive cen-

tre).

There

has,

however,

been

little

new

commercial or residential activity on the water-

front, in marked contrast to many waterfront rede-

velopments described in the literature. There has

also been little change in the low-income character

of the adjacent community.

Despite this lack of private investment on the

waterfront, the new Waterfront Trail has captured

the public imagination. According to one local news-

paper columnist, The Waterfront Trail

. . .

raises people’s hopes and expectations for positive

change. It not only signifies a break with the past, it

represents a fresh start for a city that for too long has

let things slide and settled for second best. (

)

The Waterfront Trail, then, is seen as an icon of the

‘new’ City of Hamilton, allowing ‘‘residents and vis-

itors alike to appreciate our past and look to the fu-

ture as the City and its partners continue working on

the principles of sustainability and enhancing our

overall quality of life’’ (

More specifically, the Trail is seen as a key element

in the transformation of Hamilton from a dirty steel

town to a green and healthy city with ample opportu-

nities for recreation and encounters with nature.

This paper seeks to understand how the Hamil-

ton Harbour Waterfront Trail and connected local

Kilometers

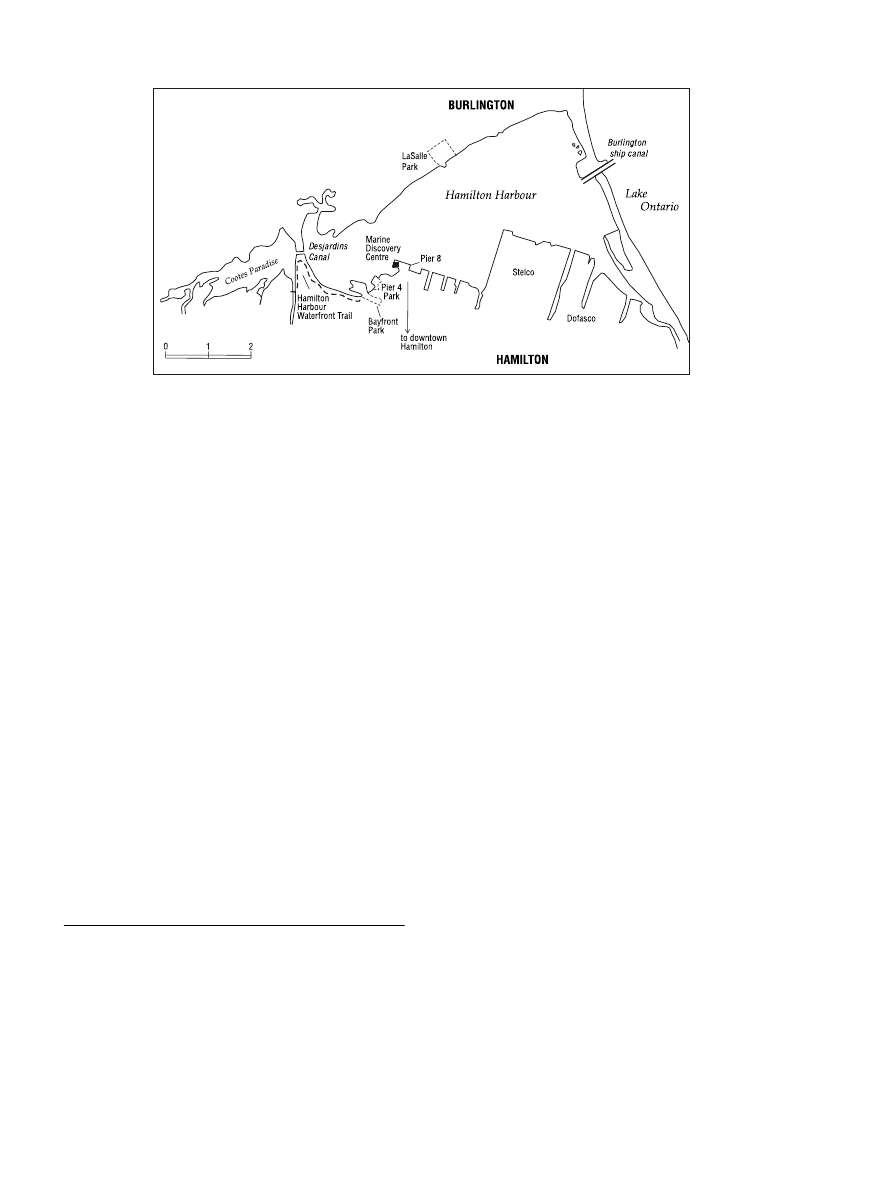

Figure 1

Map of Hamilton Harbour.

1

It should be noted that this infilling and industrial development

has been essentially limited to the Southern shore of the Harbour

(see

). The northern harbourfront, in contrast, is primarily

residential and much of it remains forested due to the hilly terrain.

The northern harbourfront is also part of the City of Burlington in

the Region of Halton, and so falls under a different jurisdiction.

Due to these differences, the paper focuses exclusively on the

southern harbourfront, and primarily on the southwestern har-

bourfront where the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail is

located.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

299

initiatives have shaped a very different waterfront

than many other cities. In so doing, it explores

the extent to which local contexts and/or broader

dynamics are implicated in the development of

Hamilton’s waterfront. The paper begins by outlin-

ing some of the key issues expressed in the water-

front revitalization literature. Results are then

presented, using key themes found in the literature

to focus the analysis. The paper concludes by

assessing how Hamilton’s waterfront redevelop-

ment informs our understanding of revitalization

projects and how they are structured by both local

and global circumstances.

Understanding waterfront revitalization:

Themes and issues

In recent years, waterfront revitalization (and urban

regeneration projects more generally) have been the

subject of considerable academic inquiry. Water-

front revitalization is by no means a new phenome-

non – ports have historically served as the principal

drivers of city economies, and as cities have grown

and changed over the centuries, so too have their

waterfronts.

However,

recent

(1960-present)

changes have led to an unprecedented transforma-

tion of many urban waterfronts. In the 19th and

20th centuries, the dominance of shipping gave

way to rail and road transport, and subsequent

changes to the shipping industry over the past few

decades led to the relocation of many harbour activ-

ities (

Hall, 1991; Van der Knaap and Pinder, 1992;

). This has rendered many existing

waterfront land uses obsolete, allowing for the

wholesale redevelopment of large tracts of land in

close proximity to city centres. Still, as

notes, the underlying forces that shape

waterfront revitalization are the same as those driv-

ing urban development more generally – that is, the

economic and political intentions of planners and

developers and the conditions under which these

activities are undertaken are central in all forms of

urban development.

Much of the existing literature views waterfront

revitalization as a means to increase the economic

vitality of localities, create new public spaces, and in-

crease access to valued cultural and natural ameni-

ties. Waterfront revitalization has been seen by

many cities as a mechanism to create and promote

a more positive image, thus securing growth and

capital investment in a competitive global market

(

). Second- and third-tier cities

in regional urban hierarchies (such as Hamilton)

may be especially anxious to attract ‘footloose capi-

tal’ that will help them make the transition from

industrial to post-industrial economies (

).

In recent years the focus has shifted to negative

aspects of waterfront revitalization, such as: an

emphasis on recreation and leisure at the expense

of ‘real’ work (see also

the exclusion of local (often working-class) people;

insufficient attention to ecological concerns; and lim-

ited public involvement in decision-making. The fo-

cus in much waterfront regeneration on ‘prestige

projects’ (

Cowell and Thomas, 2002; Loftman and

) and place marketing (

) has also been challenged, suggesting that the

‘‘delightful urban scenes’’ (

) created through regeneration are primarily

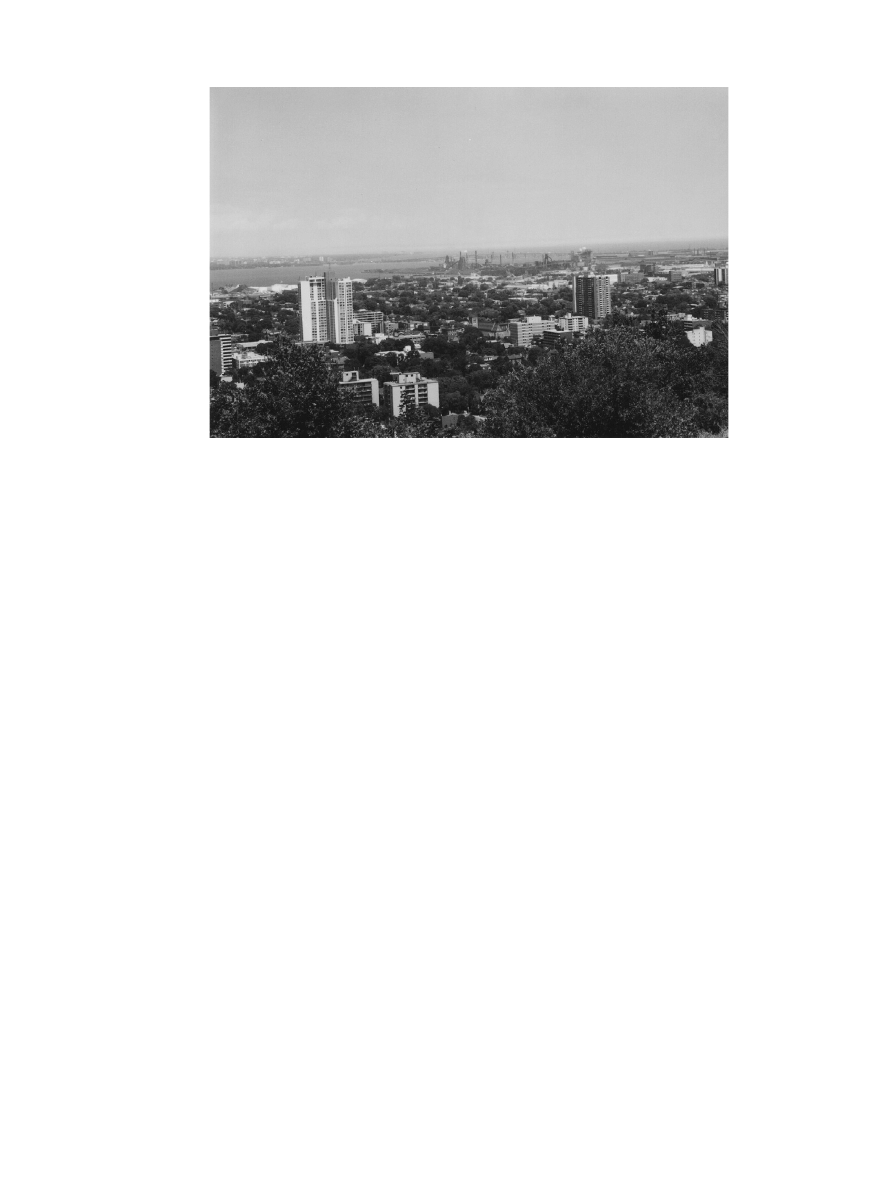

Plate 1

Hamilton’s steel mills snd eastern Harbourfront.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

300

intended for and ‘‘enjoyed mostly by those who are

benefiting from the new economy’’ (

), at the expense of those who

are not. For example, the literature is replete with

examples of how redevelopment can isolate – and

in some cases replace – working-class neighbour-

hoods (

Cowell and Thomas, 2002; Wyly and

). Conversely, com-

mitment to the provision of affordable housing in

waterfront redevelopment initiatives has been extre-

mely weak (e.g.,

In relation to environmental concerns, waterfront

redevelopment has often occurred in ways that do

little to enhance – and often further damage – the

benign integration of urban areas into natural sys-

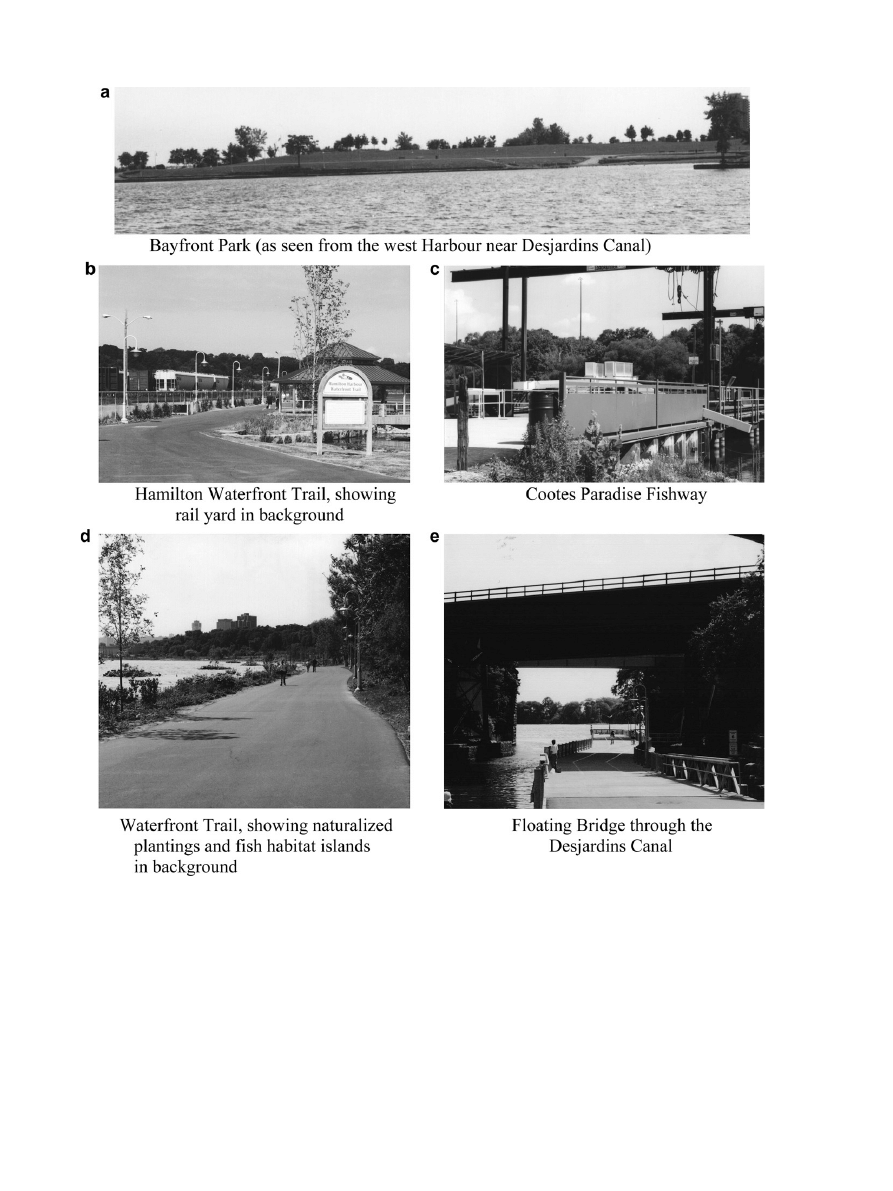

Plate 2

Sights along the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

301

tems. That is, while access to nature and greenspace

have become central to contemporary conceptions

of community well-being (

), ‘nat-

ure’ is inserted into urban planning in ways that dif-

fer by locality (

) but that

generally fail to reduce the city’s impact on the local

physical environment in key areas such as water and

air quality, habitat protection, and biodiversity. As

note, this kind of selective incor-

poration of ecological goals into urban governance is

one characteristic of ‘ecological modernization’.

Ecological modernization is an approach to environ-

mental degradation that attempts to reconcile capi-

talist growth with ecological integrity through the

development of technological solutions and the use

of market-based initiatives (

2000; Davidson and Frickel, 2004

), both of which

are common currency in waterfront redevelopment

initiatives.

Waterfront regeneration projects often serve as a

focal point for the creation of public–private, mul-

ti-stakeholder partnerships to facilitate particular

projects as part of a larger entrepreneurial agenda

(

Bassett et al., 2002; Desfor and Jorgensen, 2004;

). Some studies have found that these

partnerships replace broader public consultation,

with community involvement seen as an obstruction

to progress (

Sandercock and Dovey, 2002; Jacobs,

). Relatedly,

observes that mul-

ti-stakeholder partnerships are grounded in an

assumption that ‘‘confrontational and oppositional

behaviours are ultimately an anathema to collabora-

tion’’ (p. 19), leading to the exclusion of oppositional

voices.

This paper explores one particular case of water-

front revitalization, in order to see how these themes

play out in one locality, in order to add to our under-

standing of the processes at work and how they are

shaped by and in particular places. As

notes,

The accumulation process. . . occur[s] within a (geo-

graphically) constituted field of limits and possibili-

ties that varies greatly. . . At the level of form, the

variety of possibilities cannot be over-emphasized.

(p. 182)

Again, it is important to note that while water-

front revitalization perhaps offers an unprecedented

opportunity for developers and cities to remake

large swaths of territory, the processes through

which these changes occur are common to all urban

development.

suggests that:

Given that the waterfront may be invaded by com-

mon land uses and conventional development inter-

ests, individual projects may reflect changes in the

structure of the development industry, such as the

balance of commercial and institutional developers,

or the relative distribution of local, national, and

international interests. [. . .] The form of any indi-

vidual development reflects an underlying mix of

economic and political intentions and the condi-

tions for planning and development.’’ (

)

This paper explores how these intentions and con-

ditions are manifested in one particular case study,

using newspapers and municipal documents to sup-

ply evidence of the transformation of the waterfront

and the way that this transformation has been both

envisioned and described. The paper focuses on

the development of the Hamilton Harbour Water-

front Trail, as a geographic and temporal microcosm

within which to explore broader issues related to the

redevelopment of waterfronts in Hamilton and else-

where. In turn, this exploration sheds light on the

forces at play in the changing landscapes of indus-

trial cities.

On the waterfront: results from the Hamilton

case study

Places of work, places of leisure

The continuing visibility of industry on the southeast

shores (

) emphasizes the importance of Ham-

ilton Harbour as a place of work. While the eastern

harbourfront is used exclusively by heavy industry,

the west harbour is mixed-use – industry and trans-

portation-related activities remain prominent, but

these are interspersed with housing and other uses.

The continuing viability of heavy industry sepa-

rates Hamilton from many other examples in the lit-

erature, where the decline of traditional port

activities has opened up large areas for redevelop-

ment. At the same time, Hamilton has pursued a

similar agenda to many of these cities in terms of

its waterfront redevelopment, planning the west har-

bourfront, at least, as a place for recreation and lei-

sure. The Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail, for

example, is designed to encourage waterside recrea-

tion. Local commentators see the trail as a welcome

alteration

of

the

industrial

character

of

the

waterfront:

The value of a waterfront pathway in reclaiming the

west harbour as a place for people was evident. [. . .]

The bay is far too valuable to be used predominantly

for heavy industry and cargo shipping. Residents and

visitors want the waterfront to be an inviting natural

oasis, where they can rest or enjoy strolling, boating,

fishing, and even swimming. (Hamilton

)

Walkers, cyclists, in-line skaters and many other

users have discovered the solace of the waterfront

recreational trail. . . [F]rom the west end, the steel

mills that dominate the vista are reduced to rusty

smokestacks in the distant background, but it’s the

water and sky that fill the view. [. . .] The trail pro-

vides an escape from the city without actually having

to leave the city. (

)

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

302

As the above quote suggests, the trail is seen not

just as a place for recreation, but also as an escape

from city life. The quotes also suggest a certain level

of discomfort with the industrial character of the

city, seeing it as something to hide or get away from.

To date, waterfront redevelopment has empha-

sized the creation of open space and outdoor recre-

ational activities (such as walking the Trail). At the

same time, there are many operating businesses in

the area. The eastern harbourfront remains exclu-

sively industrial; in the west, the Trail runs on nar-

row band of land along the shoreline, adjacent to

an active rail yard (

b). While parts of Piers

4, 8, and the landfill that is now Bayfront Park have

been redeveloped for recreational and cultural uses,

many land uses on the waterfront have not been fun-

damentally altered, including two working marinas.

Walking in the area offers a compelling picture of

a working harbour, with boat, train, and warehouse

activity occurring adjacent to the Trail.

However, future plans for the waterfront empha-

sise the gradual removal of industry from the west

harbourfront. Central to waterfront planning since

the early stages has been the acquisition of the rail-

way yards adjacent to the Waterfront Trail (

b):

A key aspect of this concept plan is the relocation of

the CN marshalling yard on Stuart St. . . While two

lines will remain, the removal of the marshalling yard

will provide up to 40.5 hectares (100 acres) of water-

front land for redevelopment. Industrial lands next to

the marshalling yard are also included in the concept

plan and contribute to the acreage for redevelop-

ment. (

Early concept plans (e.g.,

used the ‘reclaimed’ rail yard (as well as adjacent

industrial lands not owned by the railway) as the

centrepiece for a massive transformation of the West

Harbourfront district: with the existing industries re-

moved, a massive leisure park was envisioned,

including expansive public gardens, an open-air

amphitheatre, and areas for ‘special attractions’

(such as a sports complex and an Imax theatre) as

well as shops and restaurants. This plan, like water-

front redevelopment schemes in other jurisdictions,

presented the potential for a ‘‘dramatic spectacle

of perpetual carnival’’ (

) along the harbourfront. It also called for the

complete removal of work-related activities in the

west harbourfront (except for work in shops and

restaurants).

The most recent harbourfront plan (

) has toned down the magnitude of the

proposed waterfront spectacle considerably. While

the relocation of the rail yard remains a major com-

ponent of future planning, the new plan includes res-

idential development and lays out fewer ‘special

attractions’ (although the planning maps include

several blank spaces that are possible sites for such

attractions). The gradual removal of industry, how-

ever, remains central to the plans for the district:

The City of Hamilton acknowledges the importance

of industry to the regional economy. Nevertheless,

it is a central principle of this Plan that the decline

of heavy industrial activity in the West Harbour is

expected. . . in keeping with City’s objective to have

industrial uses in the West Harbour relocated to a

more suitable area of the City, where it will be more

compatible with surrounding uses, existing and

planned. (

)

These ‘more suitable’ areas for industry, while not

clearly defined in the plan, are presumably found in

the eastern harbour district, or in the city’s suburban

industrial parks.

These plans are currently on hold, as the railway

company is reluctant to relocate its marshalling

yards, and the city has insufficient resources (finan-

cial and political) to encourage them to do so (

). Thus, while the Waterfront Trail was

proposed in initial concept documents as a small

component of the overall transformation of the west

harbour – a path along the water at the edge of a

new waterfront district – the Trail and the adjoining

parks are currently the primary manifestation of the

planned west harbour transformation.

At the same time, Waterfront Trail development

has irritated – although not relocated – other local

business actors. The Leander Boat Club, Royal

Hamilton Yacht Club and MacDonald Marina all ac-

tively opposed the extension of the trail between

Bayfront Park and Pier 8, as the Trail follows the

most direct route between these two points, which

is through their marinas and storage yards. Access

to these properties were previously limited to marina

and club clients – although the land is City of Hamil-

ton property, the clubs/marinas have held long-term

leases with the City. Thus, while marinas are granted

explicit exemptions from the gradual removal of

industry outlined in the most recent waterfront plan

– on the grounds that they improve the ambience of

the area (

), rather than be-

cause of their commercial function – their activities

are still being impinged upon in waterfront planning.

The relative lack of voice of these actors in trail plan-

ning will be discussed later in the paper.

Whose waterfront? Issues of access and social justice

In Hamilton, increasing public access to the water-

front has been central to planning – both the 1996

and 2005 planning documents had increasing accessi-

bility as central tenets, and many local organizations

have spoken out to ensure that public access is a key

component of any redevelopment. Some local observ-

ers have seen the development of the waterfront trail

an issue of social justice, with the good of the average

citizen set in contrast to the desires of big business:

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

303

There’s no underestimating what the Waterfront

Trail brings to Hamilton in terms of civic pride. It

rights a long-standing wrong by finally letting the lit-

tle people share the harbour with big industry. (

Since its opening July 1, 2000, it is estimated that as

many as 10,000 people per week use the Hamilton

Harbour Waterfront Trail during good weather (

), so the goal of enhancing access

to the waterfront has been supported by Trail devel-

opment. However, more limited attention has been

paid to issues of equity in access to the Trail, although

the Trail was explicitly designed to facilitate access, at

least by accommodating wheelchairs and strollers.

City documents suggest that Trail users include west

harbourfront residents, as well as residents of other

parts of the city who come down to the trail for ‘out-

ings’, but these accounts are anecdotal. One potential

concern in terms of equity is that the waterfront trail

may be most beneficial to affluent city residents from

the western suburbs of the city (which abut Cootes

Paradise –

Figure 1), who now have easier access to

While access to recreational amenities (such as the

Trail) has improved significantly in the west har-

bourfront in the last two decades, the neighbour-

hoods

themselves

remain

predominantly

low-

income (

Social Planning and Research Council of

). Indeed, the west harbourfront area

is one of the poorest in Hamilton, which itself has

the highest poverty rate in Ontario – almost 20%

of Hamiltonians live on incomes below the poverty

line (

Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction,

). Low income households in the census tracts

adjacent to the Waterfront Trail range from 24%

to 64% of total households (

search Council of Hamilton, 2004

). Some gentrifica-

tion has occurred, but this has – to date – been

limited to a small number of houses that have an

unobstructed water view. However, the potential

for the displacement of low-income households

looms large. In a newspaper article celebrating the

opening of the waterfront trail, a local writer notes,

The trail and parks have great potential as keys to an

even more exciting future for the harbour . . . the reju-

venated harbour [could be] a catalyst to the renais-

sance of surrounding neighbourhoods in the North

End. . . (

)

The question that needs to be asked (following

) is, ‘renaissance’ for whom?

The 1996 West Harbourfront Development Study

(

) does not mention afford-

able housing, and, surprisingly, neither does the

2004 land use plan for downtown Hamilton. Rather,

the emphasis is on ‘‘identifying opportunities for a

range of housing types catering to a variety of in-

come levels and household characteristics’’ (

). Given the low-income character

of the central city, this can be read as a euphemism

for developing more high-end housing. The recent

Setting Sail planning report does suggest that afford-

able housing should be a component of subsequent

development of the harbourfront (

). However, this issue is raised only briefly, and

the language is weak, suggesting that Hamilton, like

many other cities, could see an erosion of this com-

mitment in practice. As the redevelopment of the

waterfront continues to enhance the area’s attrac-

tiveness as a residential location, failure to provide

adequate affordable housing could result in the dis-

placement of existing low-income residents.

(Re)constructed nature: environmental remediation

on the waterfront

In Hamilton, waterfront redevelopment has been

accompanied by a massive ‘rehabilitation’ of the

area’s natural environment. Evidence of this can

be found along the length of the Waterfront Trail,

starting at its western terminus at Cootes Paradise.

As described in the City’s interpretive material for

the Trail,

Cootes Paradise Marsh is part of the Royal Botanical

Gardens (RBG). This area was once an extensive cat-

tail marsh, and the RBG, in conjunction with part-

ners

including

the

Fish

&

Wildlife

Habitat

Restoration Project, the Bay Area Restoration Coun-

cil, McMaster University, and the Department of

Fisheries and Oceans, are working to restore this

sanctuary. (

)

The restoration of the marsh has been extensive,

including large-scale replanting of native species,

reconstruction of shoreline habitat, and a variety of

measures to reduce the damage caused by non-

native fish species, particularly carp. The crowning

glory of the program is the Cootes Paradise Fishway

(

c), located adjacent to the Harbour Water-

front Trail. The Fishway, essentially a series of

underwater fences and traps, captures fish trying to

enter Cootes Paradise. Staff then sort and release

the fish – native species into the marsh, non-native

species back into the harbour (

). These activities are often performed for an

audience of Trail users.

Environmental restoration projects were also inte-

grated into the building of the Waterfront Trail itself,

including structures to maximize fish habitat and

‘naturalized’ landscaping with native plants (

–

d). Overall, trail design

and construction were planned with the specific in-

tent of minimizing negative environmental impacts,

and habitat maintenance and improvement objec-

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

304

tives were weighted heavily, even against concerns

about aesthetics and cost. For example, the $1.2M

(Cdn) floating walkway through the Desjardins canal

(

e) allowed the trail to be constructed without

any filling of the existing channel, and the ‘natural-

ized’ water edge along most of the Trail maximizes

the potential for shoreline habitat at the expense of

additional trail width and consistent water views.

According to the local newspaper, these efforts have

been quite successful at attracting wildlife:

Ducks nest and rear their young in this area and fish-

eating birds such as the black-crowned night heron

and the belted kingfisher use the shoreline trees as

launching pads for fishing expeditions. On the

ground, snapping turtles use the sandy slopes to lay

their eggs. (

This ‘wildness’ is also evident at Bayfront Park, at

the eastern end of the Trail. As was mentioned ear-

lier, the park was originally an industrial landfill site;

prior to its use as a park, the site had to be signifi-

cantly remediated. The waste on the site was con-

tained using armour rock (to withstand wave

action) and a soil cap. While early plans by the origi-

nal property owner and the city had included new

residential and commercial development on the site,

it was subsequently deemed unsuitable for building.

The site was therefore given entirely over to park-

land. It includes some large mown lawns for special

events, and a manicured sand beach. Other than

these areas, the peninsula has been planted with na-

tive grasses and shrubs and allowed to grow without

intervention.

Hamilton’s waterfront thus has a ‘wilder’, more

natural character than most. This quality is en-

hanced by the pronounced lack of buildings as part

of the redevelopment thus far. This represents a sub-

stantial departure from ‘bricks-and-mortar’ visions

of the waterfront (

). At the same

time, the development of this new and/or revitalized

‘wilderness’ required substantial physical transfor-

mation of the landscape. The emphasis on techno-

logical

intervention

to

mediate

environmental

damage reveals the project’s origins in a paradigm

of ecological modernization. While not all environ-

mental remediation can be seen as ecological mod-

ernization, projects which emphasize technological

solutions to environmental problems – and exhibit

a certain level of hubris accompanying these inter-

ventions (see

) – serve to embed a top-

down, reactive approach to environmental damage

that is consistent with ecological modernization.

The City of Hamilton’s selective incorporation of

ecological goals into urban governance is also con-

sistent with ecological modernization as a driving

paradigm. While the city has taken a pro-environ-

ment stance with respect to the remediation of the

harbour and the development of the Waterfront

Trail, it also decided to construct the Red Hill Creek

Expressway – an urban highway/ring road that runs

through the last remaining natural river valley in

the city – in the face of considerable opposition from

environmentalists and the federal government. The

City has also been criticised for encouraging low-

density, automobile-dependent development in the

periphery. This suburban development could impair

the ecological renewal of the harbour:

While the sediment entering the harbour is now clea-

ner, the Royal Botanical Gardens has reported very

turbid conditions on the Ancaster Creek entering

the Cootes Paradise Marsh. The turbid conditions,

which severely affect the integrity of the marsh habi-

tat, are caused by the erosion of soil from subdivision

construction. (

Remedial Action Plan for Hamilton

)

In Hamilton, then, it cannot be said that ‘the

growth imperative’ has taken a back seat to ecolog-

ical priorities. Rather, these two priorities have been

balanced in different ways in different locales within

the city, and indeed, they have come to be seen as

deeply intertwined – an idea that will be discussed

in more depth in the next section.

‘Selling the city’: the waterfront as an engine of local

economic development

Hamilton’s waterfront redevelopment, with the

Waterfront Trail as its focal point, has thus far been

low-key, emphasising natural landscapes and out-

door recreation. Interestingly, this approach has

been reconciled with the vision of the waterfront

as a growth engine by emphasizing the importance

of visible manifestations of Hamilton’s ecological

integrity in overcoming negative stereotypes. For

example, one newspaper editorial suggests that:

. . .

a trail system will improve the image of a city that

has struggled with unfair, unflattering portrayals in

the national media. We hate to count the times Ham-

ilton has been labeled an ugly, blue collar town

because of the steel plants along the bayfront. . . [A]

trail system, linking the significant natural resources

on the city’s doorstep, can work wonders in overcom-

ing negative stereotyping. (Hamilton

)

A local quasi-governmental organization goes fur-

ther, stating that:

The economic prosperity of Hamilton, Burlington,

and the Bay Area is directly related to the environ-

mental health and status of the Hamilton Harbour

ecosystem. A positive image, the attraction of tour-

ists and new residents, and private and public invest-

ment in this vital area all become more likely if. . . the

harbour and its watershed are restored. (

Environmental and economic health are thus inter-

twined in the public imagination, in ways that echo

observation that environmental

remediation within an ecological modernization

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

305

paradigm does not challenge the dominance of entre-

preneurial, growth-focused approaches to redevelop-

ment, but in fact may offer support for them.

The City of Hamilton has also adopted some rela-

tively traditional strategies for attracting growth

through waterfront redevelopment, such as the pur-

suit of anchor attractions (e.g., the new Marine Dis-

covery Centre on Pier 8) and the loosening of

development restrictions to stimulate investment.

Indeed, the City has publicly stated its willingness

to ‘expedite’ residential and commercial develop-

ment in the waterfront:

The City of Hamilton is the facilitator of the pro-

posed development and is responsible for steering

its course towards a single, viable plan. Its continuing

role is to help streamline the inquiry and administra-

tive process while coordinating the needs of landown-

ers, senior government, and future investors. (

[The City] recently announced the creation of the

Invest in Hamilton Team, in order to fast track

approvals and immediately make decisions to expe-

dite development in the City of Hamilton (

These attempts to spur further waterfront devel-

opment have yet to bear significant fruit, the new

Marine Museum notwithstanding. Interestingly, the

focus within Hamilton has recently shifted away

from the waterfront, concurrent with a change in

municipal government. The new government has

prioritised development around the Hamilton Inter-

national Airport, located at the urban fringe.

Dubbed the ‘aerotropolis’, the City envisions a

planned community with links to road corridors

and large scale commercial/spin-off development

(

). This new initiative seems

to have taken precedence over waterfront redevel-

opment, with the City calling the airport the ‘‘eco-

nomic engine’’ of its future.

Public and private interests in waterfront

redevelopment

In Hamilton, the current shape of waterfront devel-

opment can be explained, to a significant degree, by

the involvement – or lack thereof – of particular ac-

tors in Hamilton’s socio-political context. For

example, a wide range of ‘partners’ were involved

in the development of the Waterfront Trail. The

Waterfront Trail website publicly acknowledges

many for-profit and non-profit organizations for

providing financial and in-kind support for the trail

(

– see

for a list of

organizations). However, the most important actors

in the development of the Trail had a seat on the

West Waterfront Trail Project Advisory Group

(with the ungainly acronym of WWTPAG), respon-

sible for the planning and implementation of the

trail project.

A look at the list of WWTPAG members provides

a potential explanation for the foregrounding of

environmental issues in Hamilton’s waterfront revi-

talization. One third of the members of WWTPAG

were governmental and non-governmental organiza-

tions whose primary mandate is the protection and

enhancement of the natural environment. Key play-

ers included the Regional Conservation Authorities

of both Hamilton and Halton (which has jurisdiction

over the northern shores of the harbour), the federal

and provincial ministries of environment, the Fish &

Wildlife Habitat Restoration Project (responsible

for the Cootes Paradise marsh remediation), the

Royal Botanical Gardens (which owns the forests

and wetlands at the western end of the harbour,

including Cootes Paradise) and the Bay Area Resto-

ration Council.

The Bay Area Restoration Council (BARC) de-

serves additional attention in this context. BARC

is a non-profit charitable organization that oversees

the implementation of the Hamilton Harbour Reme-

dial Action Plan (HHRAP). Hamilton Harbour is

currently listed as an ‘area of concern’ under the

Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between

Canada and the United States (

). Under

the terms of the agreement, the two federal govern-

ments must implement programs and report on their

progress in restoring, preserving, and protecting the

Great Lakes (

). The

development of a Remedial Action Plan (RAP) by

quasi-governmental committees is a central compo-

nent of this implementation, and each RAP is ex-

pected to draw on local community involvement in

each area of concern to develop strategies to remedi-

ate local ecosystems and improve water quality. In

this context, the HHRAP lays out a plan to improve

harbour water quality, and BARC serves as the

organization responsible for implementing that plan.

BARC is itself a multi-stakeholder partnership, as

most BARC members represent organizations

‘‘from the agricultural, industrial, recreational, gov-

ernmental, institutional, and environmental sectors’’

(

). Many of the key actors

in WWTPAG had therefore been working together

for some time through BARC, as part of the

HHRAP development and implementation. This en-

abled better collaboration and coordination among

these partners than might otherwise be the case. It

also embedded the goals and values of the HHRAP

(including environmental remediation and enhanced

public access to the waterfront) into the Trail plan-

ning process.

Interestingly, WWTPAG did not include local

business representatives beyond those directly im-

pacted by the trail (i.e., the Canadian National

Railway and the Leander Boat Club). This may

be due to the focus of this particular re-develop-

ment project: given that there was little opportunity

for business development as part of the trail, busi-

ness leaders may not have been interested in direct

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

306

involvement at this stage. Whatever the rationale

for WWTPAG membership, the relationship be-

tween local businesses and the other members of

WWTPAG was occasionally rocky. Unlike other

WWTPAG members, the Canadian National Rail-

way (CNR) and the Leander Boat Club (and in

more recent discussions, the Royal Hamilton Yacht

Club and the MacDonald Marina) have objected to

key portions of the planned Trail development.

CNR, by refusing to move its railyard to another

location, was able to shape the trail in a particular

way. By contrast, Leander and the other marinas

were in a more tenuous situation, renting rather

than owning their properties, and thus were forced

to compromise in Trail planning and allow the

Trail to be routed through their marinas and stor-

age yards.

Beyond the most local actors, the involvement of

the business community in waterfront revitalization

more generally has been noticeably absent. This is

potentially an indicator of a ‘‘relative thinness of

business activism’’ in Hamilton (a situation observed

in Bristol, England, by

). Hamil-

ton’s business community is a mix of large, estab-

lished industrial and institutional players (e.g., the

big steel mills, the university, and the hospitals)

and smaller local businesses that may feed into these

sectors (e.g., steel machining shops and independent

laboratories) or may operate entirely outside them

(e.g., local independent retailers). Within this com-

plex landscape, there is as much potential for conflict

as consensus around the economic future of Hamil-

ton, and thus it may be difficult to organize a sec-

toral response to local policy developments (see

). Furthermore, few venture capitalists

have been stepping up to contribute to the City’s lar-

ger vision of the waterfront (i.e., a place with not

only naturalized areas, but also new attractions,

housing, and stores and restaurants). This may be a

function of a relative lack of access to venture capi-

tal within Hamilton itself, given its status as a ‘sec-

ond-tier’ city in regional hierarchies. ‘Offshore’

developers have also not been attracted to invest

(despite significant efforts by the City’s economic

development department), perhaps because of Ham-

ilton’s lingering reputation as a polluted example of

the old industrial economy.

Discussion and conclusion

The Hamilton Waterfront Trail and other related ini-

tiatives have shaped a very different waterfront than

in many cases explored in the literature. It has not

been the purpose of this paper to expand on the vir-

tues of Hamilton’s waterfront, nor to denigrate its

weaknesses. Indeed, the very characteristics that

some may consider the Hamilton waterfront’s

greatest strengths may be seen by others as its most

Table 1

Hamilton Waterfront Trail ‘Partner’ organizations

Organization name

Organization type

Bay Area Restoration Council

Non-governmental organization

Berminghammer Foundation Equipment

Industry

Canada Millennium Partnership Program

Foundation (funder)

Canadian Coast Guard

Quasi-governmental organization

Canadian National Railway

Industry (Crown corporation)

Canusa Games – Hamilton Branch

Non-governmental organization

City of Hamilton

Local government

Columbian Chemicals

Industry

Department of Fisheries and Oceans

National government

Dofasco Inc.

Industry

Environment Canada

National government

Fish and Wildlife Habitat Restoration Project

Non-governmental organization

Halton Region Conservation Authority

Quasi-governmental organization

Hamilton Harbour Commissioners

Quasi-governmental organization

Hamilton Naturalists’ Club

Non-governmental organization

Hamilton Region Conservation Authority

Quasi-governmental organization

Hamilton-Wentworth Land Stewardship Council

Non-governmental organization

Leander Boat Club

Small business

Ministry of Environment

Provincial government

Ministry of Transportation

Provincial government

‘‘Public at large’’

No organizational affiliation

Rail Link

Quasi-governmental organization

Regional Tree Planting Program

Quasi-governmental organization

Royal Botanical Gardens

Non-governmental organization

Waterfront Regeneration Trust

Quasi-governmental organization

Source: Adopted from

, accessed January 2006, and minutes from the West Harbourfront Trail Project Advisory Group meeting of December 9, 1998.

a

Held seat(s) on the West Waterfront Trail Project Advisory Group.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

307

significant failings. However, regardless of the rela-

tive success or failure of Hamilton’s waterfront rede-

velopment, it cannot be argued that the regeneration

of Hamilton’s waterfront has been guided by a funda-

mentally different set of values than those espoused in

other places. Rather, the evidence suggests that many

of the attitudes exhibited in other locales are also

present in Hamilton, such as:

discomfort with the historic character of the city as

a place for heavy industry (

),

most noticeable in calls for the removal of all

industry from the western harbourfront;

lack of consistent attention to social inequality,

particularly with respect to the need for affordable

housing (

);

an ecological modernist approach to environmen-

tal remediation (

), evident in the

connections drawn between ecological and eco-

nomic vitality;

an overriding concern with image enhancement as

part of a larger desire to attract economic invest-

ment (

); and,

a demonstrated willingness to bend existing plan-

ning restrictions to facilitate that economic invest-

ment (

However, waterfront redevelopment, like other

urban revitalization, occurs within ‘‘historically con-

tingent ensembles of complementary economic and

extra-economic mechanisms and practices’’ (

). As

notes, the potential for varia-

tion in form among different sites of investment

and development is immense, and the unique char-

acter of Hamilton’s waterfront can be at least par-

tially attributed to this ‘local contingency’. In this

case, waterfront development was shaped by spe-

cific environmental conditions, as well as by exist-

ing networks between institutions. At the city

level, Hamilton’s legacy of environmental contami-

nation as a result of the city’s industrial heritage fo-

cussed efforts on the need for environmental

improvements as part of a waterfront redevelop-

ment strategy; at the site level, specific biophysical

conditions (such as the unsuitability of the Bayfront

Park property for building construction) have con-

strained the choices that can be made by local ac-

tors. In addition, local actors are bound together

in a variety of strong and weak networks that have

evolved over time. In particular, the prior involve-

ment of many local stakeholders in the develop-

ment of the Remedial Action Plan through the

Bay Area Restoration Council has given a particu-

lar shape and focus to the subsequent waterfront

planning.

However, many ‘local’ constraints and opportu-

nities were themselves structured by macro-scale

trends within the economy and government. For

example, waterfront redevelopment in Hamilton

occurred in relation to extra-local policy arrange-

ments that privileged environmental concerns over

economic and social ones. That is, broader na-

tional and international imperatives – in particular

the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement –

shaped waterfront redevelopment through the pro-

vision of resources for environmental remediation,

and through the purposeful development of local

institutional networks around that remediation.

Thus, the new partnership arrangements created

on the waterfront were shaped by broader socio-

political contexts in ways that impacted on the

eventual

redevelopment

program

(see

). Other broad trends, such as the relative po-

sition of Hamilton within global and national ur-

ban hierarchies (i.e., as a second-tier city) and

the prevalence of particular growth discourses

(e.g., of the importance of ‘city selling’), also help

to explain the character of the Hamilton water-

front. In particular, Hamilton’s national reputation

as a polluted industrial city stimulated a waterfront

development designed, at least in part, to refute

that reputation in order to stimulate investor inter-

est in the city.

Hamilton’s waterfront thus emerged from a mix of

global pressures and local exigencies rather than by

intent. This leaves it vulnerable to future develop-

ment that could compromise its current character.

For example, by promoting the waterfront as a site

for other, more commercially-focused attractions,

the City runs the risk of ‘serial reproduction’ (

). That is, while image-focused develop-

ment relies on the creation of a unique appeal,

development initiatives that attempt to purposefully

create uniqueness end up looking alike (

). In addition, a failure to explicitly

address issues that might compromise the water-

front’s social and ecological integrity (e.g., loss of

employment, gentrification, upstream ecological

degradation) could undermine past initiatives.

This account does not tell the full story of water-

front redevelopment in Hamilton. The focus on pub-

lic documents and newspaper accounts means that

the nuances of the development process remain opa-

que. For example, the views of and personal rela-

tionships between key actors are inadequately

captured. In addition, the focus on the Hamilton

Harbour Waterfront Trail as a case study means that

other aspects of Hamilton’s waterfront change are

not fully explored. However, the data sources used

in this paper help to generate a better understanding

of the dominant viewpoints expressed on Hamilton’s

waterfront, and give a sense of the broad dynamics

at work, at least in terms of the development of

the Trail. This paper contributes to our understand-

ing of the local and extra-local factors that shape

waterfront development, and begins to elucidate

how the local and extra-local are connected through

networks of actors, patterns of economic investment

and/or decline, and perhaps most importantly, by

globalized growth discourses that are re-interpreted

at the local level.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

308

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the support

provided by a Social Sciences and Humanities Re-

search Council of Canada (SSHRC) research grant

(#456228). In addition, the author wishes to recog-

nize the hard work of two research assistants, Vivian

Ng and Julie Fleming.

References

Atkinson, R (2000) The hidden costs of gentrification: displace-

ment in central London. Journal of Housing and the Built

Environment 15(4), 307–326.

BARC, (nd). Bringing Back the Bay [pamphlet]. Bay Area

Restoration Council. Hamilton, Ont., Canada.

BARC (2004) Hamilton/Burlington Bay Area Access Map [pam-

phlet]. Bay Area Restoration Council, Hamilton, Ont.,

Canada.

Bassett, K, Griffiths, R and Smith, I (2002) Testing governance:

partnerships, planning, and conflict in waterfront regeneration.

Urban Studies 39(10), 1757–1775.

Breen, A and Rigby, D (1985) CAUTION: Working Waterfront.

The Waterfront Press, Washington, DC.

Browne, D R and Keil, R (2000) Planning ecology: the discourse

of environmental policy-making in Los Angeles. Organization

and Environment 13(2), 158–205.

City of Hamilton (n/d) West Harbourfront in Southern Ontario,

Canada [Economic Development Brochure]. City of Hamil-

ton, Planning and Economic Development Department.

City of Hamilton (1995) A Vision for the Future: The West

Harbourfront Development Study Final Report. City of Ham-

ilton Planning Department.

City of Hamilton (2000) Hamilton Steel Sector Profile. City of

Hamilton Economic Development Department, Hamilton,

Ont. Available online at

http://www.myhamilton.ca/nr/rdonly-

res/f3d401f9-bd8c-4339-8113c24699eb76a3/0/gh106steelprofile-

spreads2.pdf

, accessed January 2006.

City of Hamilton (2004a) Hamilton Economic Development

Review, 2004. Available online at

NR/rdonlyres/5782A965-6617-449F-A098-C906E6D31E64/0/

ecdevreview04.pdf

, accessed January 2006.

City of Hamilton (2004b) Putting People First: The New Land Use

Plan for Downtown Hamilton. City of Hamilton Economic

Development Department, Hamilton Ont.

City of Hamilton (2005a) Setting Sail: The Hamilton West

Harbour Planning Area Study. City of Hamilton Planning

and Economic Development Department. Hamilton, Ont.

City of Hamilton (2005b) Invest in Hamilton 2005. Perspective

Marketing, Hamilton, Ont.

City of Hamilton (2005c) Economic Development Strategy.

Available online at

http://www.myhamilton.ca/NR/rdonlyres/

ED4F0E97-34B2-4374-AD24-DB034885ECB5/0/EcDevStrat-

egyFinal2005.pdf

; accessed April 2006.

City of Hamilton (2006a) Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail.

Available online at:

http://www.myhamilton.ca/myhamilton/

cityandgovernment/citydepartments/publicworks/parks/public

trails/trailslist.htm

, accessed February 2006.

City of Hamilton (2006b) Friends of the Waterfront Trail.

Available online at

http://www.myhamilton.ca/myhamilton/

cityandgovernment/citydepartments/publicworks/parks/progra

ms/friendswaterfronttrail.htm

; accessed April 2006.

Cruikshank, K and Bouchier, N B (2004) Blighted areas and

obnoxious industries: constructing environmental inequality on

an industrial waterfront, Hamilton, Ontario, 1890–1960. Envi-

ronmental History 9(3), 464–496.

Cox, K R (2004) Globalization and the politics of local and

regional development: the question of convergence. Trans-

actions of the Institute of British Geographers 29, 179–

194.

Cowell, R and Thomas, H (2002) Managing nature and narratives

of dispossession: reclaiming territory in Cardiff Bay. Urban

Studies 39(7), 1241–1260.

de Vries, S, Verheij, R A, Groenewegen, P P and Spreeu-

wenberg, P (2003) Natural environments – healthy environ-

ments? An exploratory analysis of the relationship between

greenspace and health. Environment and Planning A 35,

1717–1731.

Davidson, D J and Frickel, S (2004) Understanding environmental

governance: a critical review. Organization and Environment

17(4), 471–492.

Desfor, G and Jorgensen, J (2004) Flexible urban governance: the

case of Copenhagen’s recent waterfront development. Euro-

pean Planning Studies 12(4), 479–496.

Donald, B (2005) The politics of local economic development in

Canada’s city regions: new dependencies, new deals, and a new

politics of scale. Space and Polity 9(3), 261–281.

Dreschel, A (2000) Waterfront Trail rights a longstanding fault.

Hamilton Spectator 10(July), A3.

Dunphy, B (2000) CN shunts harbour jewel away; Railway’s 20-

year deal ties up waterfront. Hamilton Spectator 30(October),

A1.

Environment Canada (2006) Great Lakes Water Quality Agree-

ment. Available online at

http://www.on.ec.gc.ca/greatlakes/

default.asp?lang=En&n=FD65DFE5-1

, accessed September

2006.

Evans, L (1970) Hamilton, the Story of a City. Ryerson Press,

Toronto.

Eyles, J and Peace, W (1990) Signs and symbols in Hamilton: an

iconology of Steeltown. Geografiska Annaler B 72, 73–88.

Gold, J and Ward, S (eds.) (1994) Place Promotion: The Use of

Publicity and Marketing to Sell Towns and Regions. Wiley,

Chichester.

Jacobs, K (2004) Waterfront redevelopment: a critical discourse

analysis of the policy-making process within the Chatham

maritime project. Urban Studies 41(4), 817–832.

Judd, D R and Fainstein, S (1999) The Tourist City. Yale

University Press, New York.

Hall, P., 1991. Waterfronts: A New Urban Frontier. University of

California Institute of Urban and Regional Development,

Berkeley CA. Working Paper 538 (May).

Hall, T and Hubbard, P (1996) The entrepreneurial city: new urban

politics, new urban geographies? Progress in Human Geogra-

phy 20(2), 153–174.

Hall, T and Hubbard, P (eds.) (1998) The Entrepreneurial City.

Wiley, Chichester.

Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction (2005) Roundtable

for Poverty Reduction Takes Community Approach [press

release]. Available online at

http://www.myhamilton.ca/myha-

milton/CityandGovernment/NewsandPublications/NewsRe-

leases/2005News/May/05-05-13b.htm

; accessed April 2006.

Spectator, Hamilto (1999) Taking back our waterfront. [Editorial].

Hamilton Spectator 13(July), A8.

Harvey, D (1989a) The Urban Experience. Blackwell, Oxford.

Harvey, D (1989b) The Condition of Postmodernity. Blackwell,

Cambridge, MA.

Higgs, E S (2003) Nature by Design: People, Natural Process, and

Ecological Restoration. MIT Press, Boston.

Hoyle, S B, Pinder, D and Husain, M S (1988) Revitalising the

Waterfront: International Dimensions of Dockland Redevelop-

ment. Belhaven Press, London.

Hughes, R (1999) Neighbourhood under siege: Northeast residents

face the worst of industry, traffic and smelly regional opera-

tions. Hamilton Spectator(December 15), A1.

Jessop, B (1997) The entrepreneurial city: re-imaging localities,

redesigning economic governance or restructuring capital. In

Transforming Cities: Contested Governance and New Spatial

Divisions, N Jewson and S MacGregor (eds.), pp. 8–41.

Routledge, London.

Loftman, P and Nevin, B (1996) Going for growth: prestige

projects in three British cities. Urban Studies 33, 991–1019.

Malone, P (1996) Introduction. In City, Capital and Water, P

Malone. City, Capital and Water. Routledge, London.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

309

McCarthy, J (2004) Tourism-related waterfront development in

historic cities: Malta’s Cottonera project. International Plan-

ning Studies 9(1), 43–64.

McNulty, G (2000) Waterfront trail opening is cause for accolades.

Hamilton Spectator(July 4), A12.

Poncelet, E C (2001) ‘A kiss here and a kiss there’: conflict and

collaboration in environmental partnerships. Environmental

Management 27(1), 13–25.

Raco, M (2003) The social relations of business representation and

devolved governance in the United Kingdom. Environment and

Planning A 35, 1853–1876.

Raco, M (2002) The social relations of organizational activity and

the new local governance in the UK. Urban Studies 39(3), 437–

456.

Remedial Action Plan for Hamilton Harbour (2006a) Accom-

plishments and Challenges. Available online at

www.hamiltonharbour.ca/rap/accomplishments.htm

; accessed

May 2006.

Remedial Action Plan for Hamilton Harbour (2006b) Hamilton

Harbour Remedial Action Plan 2000–2005 Highlights and

Summary. January 16.

Sandercock, L and Dovey, K (2002) Pleasure, politics, and the

‘public interest’: Melbourne’s riverscape revitalization. APA

Journal 68(2), 151–164.

Short, J R and Kim, Y H (1999) Globalization and the City.

Addison-Wesley/Longman, Essex.

Short, J R, Benton, L M, Luce, W B and Walton, J (1993)

Reconstructing the image of an industrial city. Annals of the

Association of American Geographers 83(2), 207–224.

Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton (2004)

Incomes and Poverty in Hamilton. Available online at

www.sprc.hamilton.on.ca/Reports/povincsum04.pdf

; accessed

April 2006.

Stirrup, M (1996) Implementation of Hamilton–Wentworth

Region’s pollution control plan. Water Quality Research

Journal of Canada 31(3), 453–472.

Van der Knaap, B and Pinder, D A (1992) Revitalising the

European Waterfront: policy evolution and planning issues. In

European Port Cities in Transition, B S Hoyle and D A Pinder

(eds.), pp. 55–175. Belhaven Press, London.

Wakefield, S and McMullan, C (2005) Healing in places of decline:

(re)imagining everyday landscapes in Hamilton, Ontario.

Health and Place 11(4), 299–312.

Wells, J (2000) Welcome to the best city on the planet. Hamilton

Spectator(January 26), B1.

While, A, Jonas, A E G and Gibbs, D (2004) The environment and

the entrepreneurial city: searching for the urban sustainability

fix in Manchester and Leeds. International Journal of Urban

and Regional Research 28(3), 549–569.

Wood, R and Handley, J (1999) Urban waterfront regener-

ation in the Mersey Basin, North West England. Journal

of Environmental Planning and Management 42(4), 565–

580.

Wyly, E and Hammel, D (1999) Islands of decay in seas of

renewal: housing policy and the resurgence of gentrification.

Housing Policy Debate 10(4), 711–769.

Zimonjic, P (2001) Harbour trail a scenic escape. Hamilton

Spectator(August 21), A6.

Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail: S Wakefield

310

Document Outline

- Great expectations: Waterfront redevelopment and the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

great expectations summary

Great Expectations Powerful Themes in the Novel

great expectations

Great Expectations key?cts

Ch Dickens, Great Expectations

Dickens Great Expectations

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Great Expectations study questions

Great Expectations Comparison to Oliver Twist doc

Great Expectations

Great expectations

ebooksclub org Charles Dickens Great Expectations Bloom 039 s Guides

Great Expectations The importance of Mrs Joe doc

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Charles Dickens GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Dickens Charles Great expectations

History of Great Britain exam requirements

Introduction to Lagrangian and Hamiltonian Mechanics BRIZARD, A J

how to write great essays id 20 Nieznany

więcej podobnych podstron