Eduardo D. Faingold

The Development of

Grammar in Spanish and

the Romance Languages

The Development of Grammar in Spanish and the

Romance Languages

The Development of

Grammar in Spanish and

the Romance Languages

Eduardo D. Faingold

University of Tulsa

© Eduardo D. Faingold 2003

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this

publication may be made without written permission.

No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted

save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence

permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency,

90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP.

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication

may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author has asserted his right to be identified

as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published 2003 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010

Companies and representatives throughout the world

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave

Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom

and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European

Union and other countries.

ISBN 1–4039–0052–3 hardback

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully

managed and sustained forest sources.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Faingold, Eduardo D.

The development of grammar in Spanish and the Romance languages /

Eduardo D. Faingold.

p.

cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1–4039–0052–3

1. Language acquisition.

2. Creole dialects.

3. Historical linguistics.

4. Romance languages—Grammar, Historical.

I. Title.

P118.F354 2003

401

′.93—dc21

2003040544

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

12

11

10

09

08

07

06

05

04

03

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne

Magistro meo Carolo Iacobo hunc librum dono

vii

Contents

List of Figure and Tables

ix

Acknowledgements

xii

1

Introduction

1

1.1

Theoretical background and assumptions

1

1.2

Aims of the book

2

1.3

Research procedures

3

1.4

A model of markedness

3

1.5

Outline for the book

8

2

Articles: A Result of Natural Morphological Processes

in First Language Acquisition, Creolization, and

Language History

10

2.1

Introduction

10

2.2

Sources of data

16

2.3

The acquisition, creolization, and history of

the article system

18

2.4

The natural development of the article system

31

2.5

Summary and conclusions

37

3

Demonstrative Pronouns: A Source of Definite

Articles in History

39

3.1

Introduction

39

3.2

The data: from classical Latin to the

Romance languages

40

3.3

Demonstratives and indefinite articles in

Latin and the Romance languages

41

3.4

The grammaticalization of the definite

article from Latin

48

3.5

Summary and conclusions

52

4

Prepositions and Adverbs: Similar Development

Patterns in First and Second Language Acquisition

54

4.1

Introduction

54

4.2

Applying a developmental model of markedness

54

4.3

Sources of data

57

4.4

Spatial prepositions and temporal adverbs

in first and second language acquisition

59

4.5

Spatial prepositions and temporal adverbs

in developmental morphology

66

4.6

Summary and conclusions

68

5

Subjunctive Verbs: A Result of Natural Grammatical

Processes in First Language Acquisition, Second Language

Learning, Language Variation, and Language History

70

5.1

Introduction

70

5.2

Applying the developmental model of markedness

70

5.3

Sources of data

71

5.4

The acquisition, learning, variation, and

history of mood

72

5.5

The development of mood

84

5.6

Summary and conclusions

90

6

The Mental Representation of Linguistic Markedness:

Cognitive Aspects of the Spanish Subjunctive

91

6.1

Introduction

91

6.2

The Spanish present and past subjunctive:

cognitive aspects of markedness

95

6.3

The future subjunctive in Spanish: cognitive

aspects of markedness

107

6.4

Summary and conclusions

117

7

Summary and Conclusion

119

Appendices

125

References

138

Index

145

viii

Contents

ix

List of Figure and Tables

Figure

6.1

The future subjunctive in the Argentine Civil Code

(before 1884) and its Appendix (after 1884)

116

Tables

1.1

A developmental model of markedness

5

2.1

English-based creoles: articles in Hawaiian creole

14

2.2

English-based creoles: articles in Sranan

15

2.3

A developmental typology of linguistic systems

18

2.4

A revised developmental typology of

linguistic systems

18

2.5

Errors of segmentation by English-speaking children

20

2.6

Errors of segmentation by Spanish- and

Portuguese-speaking children

20

2.7

Speaker-specific and listener-specific errors

21

2.8

English-speaking children aged 3: speaker

specific and listener non-specific

22

2.9

French-speaking children aged 3 to 9:

speaker specific and listener non-specific

22

2.10

Romance-based creoles

24

2.11

History: articles in the Romance languages

29

2.12

Spanish/Portuguese-based koines: articles in

Judeo-Ibero-Romance

30

2.13

Spanish/Portuguese-based fusion: articles

in Fronterizo

32

2.14

Fusion in the article system of Fronterizo

32

2.15

The article system in child language, creolization,

and language history

33

2.16

A typology of article systems

34

2.17

Hierarchy of markedness for article systems

34

2.18

A hierarchy of article systems

35

2.19

Markedness criteria

35

3.1

Criteria for establishing correspondences between

Latin demonstratives and Romance articles

42

3.2

Nominatives, accusatives, and innovations in

Egeria’s Peregrinatio ad Loca Santa (Vulgar Latin,

4th to 6th century)

44

3.3

Nominatives and accusatives in Chrodegangus’

De Vestimenta Clericorum (Vulgar Latin,

mid-8th century)

45

3.4

Demonstratives in Classical Latin

46

3.5

Demonstratives functioning as articles in Vulgar Latin

46

3.6

The definite article in Spanish, Portuguese,

and Rumanian

47

3.7

The development of the definite article

48

3.8

The emergence of the definite article in Egeria’s

Peregrinatio ad Loca Santa

49

3.9

The emergence of the definite article in

Chrodegangus’ De Vestimenta Clericorum

51

3.10

The emergence of the definite article in

a Spanish document (12th century):

a real estate transaction

52

4.1

Spatial prepositions in child language

60

4.2

Spatial prepositions in second language acquisition

64

5.1

The subjunctive in modern Spanish

73

5.2

The subjunctive in modern French

74

5.3

Language acquisition: subjunctive in

French-speaking children aged 3, 4 and 5

74

5.4

Language acquisition: subjunctive in

Spanish-speaking children aged 4 to 12

75

5.5

Subjunctive neutralization in 2nd language

learning: English speakers learning Spanish

76

5.6

Language variation: subjunctive

neutralization in French

77

5.7

Language variation: subjunctive neutralization

in modern Latin American and Iberian Spanish

79

5.8

Subjunctive neutralization in modern Latin

American and Iberian Spanish

80

5.9

Subjunctive neutralization in Argentine Spanish

82

5.10

Language history: subjunctive neutralization

in medieval Spanish

83

x

List of Figure and Tables

5.11

Language history: subjunctive neutralization

in 17th century French

84

5.12

Markedness rules for mood in child language,

second language learning, language variation,

and language history

85

5.13

A hierarchy of markedness rules

86

5.14

Markedness criteria for ranking markedness

rules of mood in Spanish and French

86

6.1

Present subjunctive in subordinate clauses

introduced by que

96

6.2

Present subjunctive after subordinators

99

6.3

Other uses of the present subjunctive

100

6.4

Past subjunctive in subordinate clauses

introduced by que

102

6.5

Past subjunctive after subordinators

104

6.6

Other uses of the past subjunctive

106

6.7

Future subjunctive in early modern Spanish

108

6.8

Future subjunctive in modern Spanish

109

6.9

The future subjunctive in the Argentine

Civil Code before 1884

111

6.10

The future subjunctive in the Appendix

of the Argentine Civil Code after 1884

115

6.11

The future subjunctive in the Argentine

Civil Code (before 1884) and its Appendix

(after 1884). Normalization of cases of the

future subjunctive per one-hundred pages

117

List of Figure and Tables

xi

Acknowledgements

Much of this research was supported by five University of Tulsa Faculty

Research Grants in 1999 (#13-2-1010115), 2000 (#20-2-1010124,

#20-2-1010114) and 2001 (#20-2-101115). I am grateful to the

University of Hawaii at Manoa, Oxford University, and the University

of Paris, Sorbonne for appointing me as Visiting Professor in 1999,

2000, and 2001 respectively and for providing library services. I am

grateful to the East–West Center at the University of Hawaii at Manoa

for offering very comfortable housing in paradise in the summers of

1999 and 2000. I am also grateful to Prof. C.-J. N. Bailey who

welcomed me to his home in Hilo, Hawaii and offered invaluable

advice and comments on all the chapters in this book in the summers

of 1999 and 2000. I am grateful to Prof. Bernard Comrie and Prof.

Michael Tomasello at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary

Anthropology, Leipzig for appointing me as Visiting Scientist in the

summer of 2002. I am indebted to the Deutscher Akademischer

Austauschdients (DAAD) for a Study Visit Grant (#A/02/15036) to visit

the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig in

the summer of 2002.

Revisions of the chapters in this book have benefitted from com-

ments by the audiences at the LSA conference in Los Angeles, January

1993, the WECOL conference at the University of Washington,

Seattle, October 1993, the LSA conference in Boston, January 1994,

the 1st Lisbon Meeting on Child Language at the University of

Lisbon, Portugal, June 1994, the AATSP conference in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, August 1994, the ILA meeting at Georgetown

University, Washington D.C., March 1995, the Second Language

Research Forum at Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan,

October 1997, the LASSO conference at the University of Texas,

San Antonio, Texas, October 1999, the Sociolinguistics Symposium

at the University of West England, Bristol, UK, April 2000, the LASSO

conference at the Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico, October

2000, and the conference Towards a Unified Framework in Develop-

mental Linguistics at the University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma, April

2001. All the chapters in this book have benefitted greatly from

xii

comments by Prof. C.-J. N. Bailey. Revisions of Chapter 6 has bene-

fitted from comments by Prof. Almeida Jacqueline Toribio from

PennState University, Prof. Michel DeGraff from MIT, and Dr. Sonia

Hocherman.

I am grateful for having studied and worked with Prof. Itzhak

Schlesinger and Moshe Chayen at the Hebrew University of

Jerusalem, Prof. Ruth Berman at Tel-Aviv University, Prof. C.-J. N.

Bailey at the Technische Universitat Berlin, Prof. Roger W. Andersen

at the University of California Los Angeles, Prof. Mark Aronoff and

Prof. Robert Hoberman at the State University of New York at Stony

Brook, and Prof. Lydie Meunier at the University of Tulsa.

Acknowledgements

xiii

1

Introduction

This study investigates possible correspondences in the grammatical

development of first languages, adult second languages, creoles, and

historical linguistics (Baron 1977; Bickerton 1981; DeGraff 1999;

Faingold 1996b). I aim to shed light on the theoretical implications

of the relationship among child language, diachronic linguistics, and

creolization, with the goal of providing a unified means to account

for biological, psychological, and social aspects of grammatical

development in these domains. This study attempts to explain the

direction of morphological acquisition and change (Bailey 1996;

Dressler 1985; Mayerthaler 1988; Wurzel 1989).

1.1

Theoretical background and assumptions

By taking into account data from such varied linguistic areas as child

language, adult language learning, language history, and creolization,

the research adopts an integrative perspective to study biological,

psychological, and social constraints on language development

(Baron 1977; Faingold 1996b). The aim of this research is to reveal

universals of language and stipulate constraints on variation and

mechanisms of language change. This study assumes that there exists

a range of permissible realizations of linguistic structures and that

this range can be gradually extended. I further assume that such

extensions are unidirectional and that they are natural in the

following senses: they are resistant to change; they occur with high

frequency in many languages and in language ontogeny; they tend

to be the basis of neutralization and analogical change; they are

1

usually less subject to speech errors; and they are acquired early by

children (Faingold 1996b).

In early developmental stages, speakers are constrained to select

the lowest common denominator or simplest forms approximating

the structure of a universal base. Thus, this study’s approach assumes

that child language, foreign language learning, and creoles are

areas that most closely manifest language universals. Researchers

have suggested that certain similarities in these areas, such as the

preference for less-marked structures, can be explained by an innate

program based on biological and cognitive capacities (Bickerton 1981).

Others have concluded that some developments are explained better

by hierarchies of complexity, which in turn depend on a dynamic

theory of markedness (Bailey 1996; Edmondson 1985; Faingold 1996b;

Mayerthaler 1988). This latter theory explains possible changes as

reflections of natural language processes; and thus, the theory is

relevant for constructing implicational hierarchies. Implicational

hierarchies can be used to test the hypothesis that, all other things

being equal, less-marked structures chronologically antecede, co-occur

with (Hawkins 1987), and subsequently replace, more marked struc-

tures in child language, foreign language learning, language history,

and creolization. In certain cases, the direction of change is reversed

by quite general sociocommunicational processes or by a specific set

of natural rules (e.g. constructional iconicity, markedness-reversal,

fusion, decreolization, etc.).

1.2

Aims of the book

Many linguists have noted the closeness of historical change and

creolization. This book broadens the study of processes of language

contact and change by including not only historical linguistics

and creolistics but also first and second language acquisition (see

Faingold 1996b). This book does for grammar what a previous book

(Faingold 1996b) did for phonology: it applies Bailey’s (1996) and

Mayerthaler’s (1988) seminal work on linguistic naturalness and

markedness (developmental linguistics) in English and German to

the study of language development in children, foreign-language

learners, creoles, and language history in Spanish and the Romance

languages (Portuguese, French, Italian, Rumanian), including the

so-called ‘daughter languages’ of Spanish, Papiamentu creole (spoken

2

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

in the Dutch West Indies), and Palenquero creole (Colombia), Judeo-

Spanish (Romania, Greece, Macedonia, Turkey, and Chile); Fronterizo

(Uruguay); and U.S. Spanish (Los Angeles, New York). Examples from

other languages are considered as well when relevant. In addition,

this work uncovers mechanisms of markedness, implicational uni-

versals, and linguistic variation across linguistic fields. The reader is

given a substantial and original account of a unique corpus of data

in a variety of settings. The study offers a systematic analysis of

a wide range of grammatical structures, including articles, demon-

strative pronouns, prepositions, adverbs, and verbs.

1.3

Research procedures

The linguistic analysis proceeds in the following steps (Baron 1977:

5–13; Faingold 1996b):

1. Selection of child grammatical structures for which exist compar-

able structures in foreign language learners, language history, and

creoles.

2. Description and evaluation of the relevant stages through which

the grammatical structures under analysis might have passed, and

of how the developments occurred.

3. Description and evaluation of the knowledge a child or an adult

requires in order to use a certain grammatical construction is

determined by reference to linguistic structures in the languages

under study. The child and adult data are analyzed to explain the

chronological order in which speakers might acquire particular

grammatical structures and to reveal the constraints and strategies

needed to master the grammatical systems.

1.4

A model of markedness

This study adopts Bailey’s (1982, 1996) formal characterization of

markedness, as stated in (1) below:

(1) a

⬎m : ⬍m (the more-marked changes to less-marked)

b

⬎m 傻 ⬍m (the presence of the more-marked implicates the

presence of the less-marked)

Introduction

3

Principle (1)a states that if x changes to y, x is more-marked than y,

and y is less-marked than x. Principle (1)b defines the natural implica-

tional patterns of the system. These principles, however, can be

overruled by the borrowing of prestige structures and other sociocom-

municational developments, as well as by higher-level developments;

for instance, reversals in marked categories or environments – fusion,

violations to the principle of constructional iconicity, markedness-

reversal, and so forth (see, e.g. Faingold 1991, 1995b).

This study adopts Faingold’s (e.g. 1991, 1995a, 1995b, 1996a,

1996b, 1996c, 1998a, 1998b, 1998c) model of markedness, which is

based on Bailey’s (1982, 1996) and Mayerthaler’s (1988) theory of

dynamic-developmental linguistics (see also Dressler 1985; Wurzel

1989). The model of markedness reveals universal mechanisms of

language development as well as biological, psychological, and socio-

communicational constraints on language change. The approach

takes into account language acquisition and language learning, as

well as pidgins, creoles, history, koinés, and so on the assumption

that these are linguistic areas that reflect universals of markedness

most closely. This version of markedness theory explains possible

changes as reflections of natural processes and is relevant for

constructing implicational hierarchies. These hierarchies are used

to test the hypothesis that less-marked linguistic structures replace

more-marked structures in the development of linguistic systems. In

certain cases, the direction of change is reversed for sociocommuni-

cational reasons (e.g. borrowing, decreolization, morphologization,

markedness-reversal, etc.). In this framework, the assignment of

markedness values is not arbitrary but the result of logically-

independent, empirically-based tests that capture significant relation-

ships between phenomena that would otherwise be unrelated. The

model of markedness in Table 1.1 is adapted from Faingold (1996b)

for the study of grammatical development, and displays relevant

areas and mechanisms of syntactic markedness.

Here is an explanation of the model.

(1) Identification of marked structures

(a) System-internal areas

(i) Child language

This measure concerns the early avail-

ability of linguistic forms to the child. Markedness theory

4

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

states that children select less-marked forms and omit

or replace more-marked with less-marked forms (see

examples in Chapters 2, 4, 5).

(ii) Second language acquisition

Less-marked structures are

learned before more-marked forms by adults in a natural

environment (see examples in Chapters 4, 5).

(iii) Second language learning

Less-marked structures are

learned before more-marked forms by adults in the

classroom (see examples in Chapter 5).

(b) System-external areas

(i) Language history

Less-marked structures substitute for

more-marked structures and not vice-versa in the history

of a language (see examples in Chapters 2, 3, 5). The

directionality of change can be reversed by borrowing,

fusion, markedness-reversal, and so on.

Introduction

5

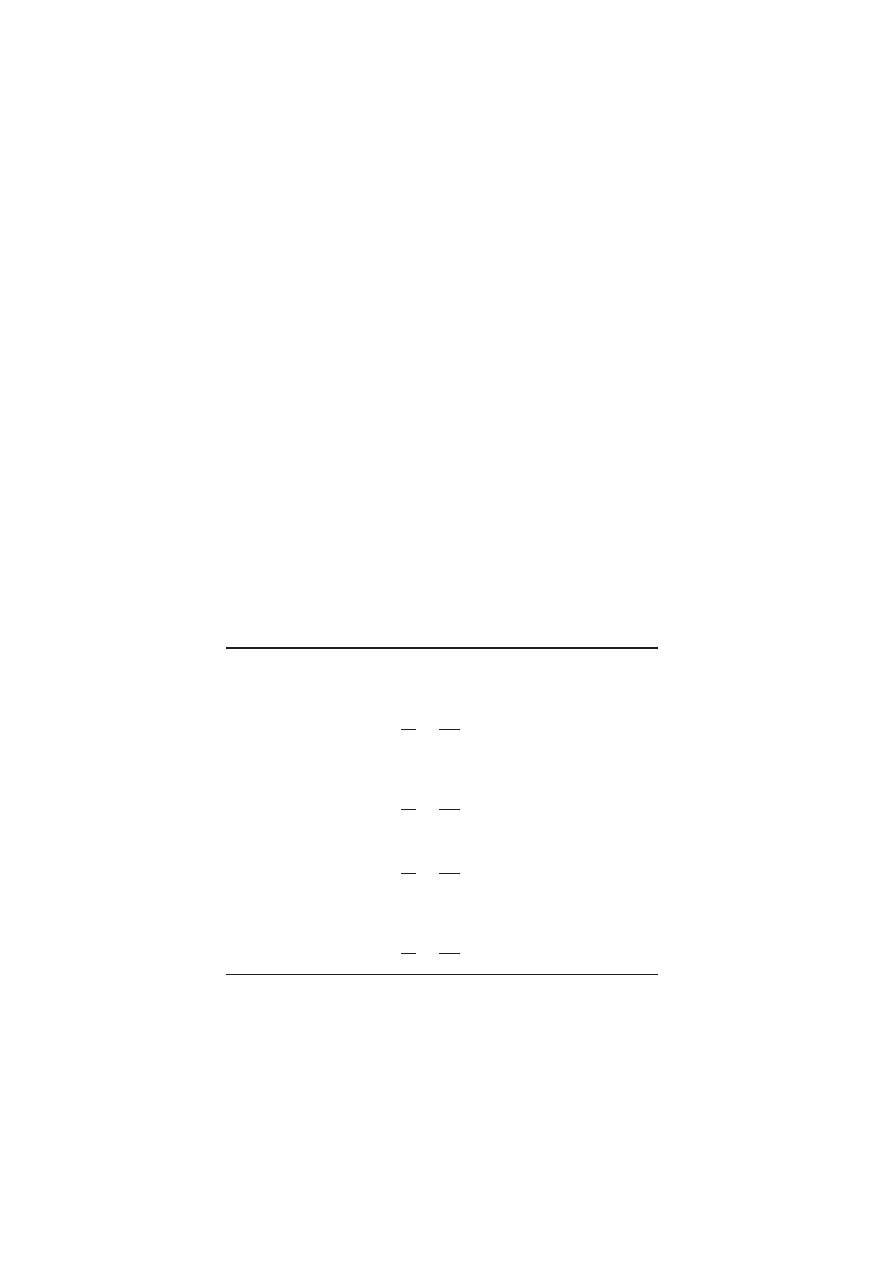

Table 1.1

A developmental model of markedness (Faingold 1996: 23)

1. Identification of marked structures

(a) System-internal areas

(i) Child language

(ii) Second language acquisition

(iii) Second language learning

(b) System-external areas

(i) Language history

(ii) Language variation

(iii) Crossfield correspondences

(iv) Crosslinguistic correspondences

(v) Neutralization

(vi) Frequency

(vii) Constructional iconicity

2. Mechanisms of development

(a) Biological mechanisms

(i) Psycho-semantic constraints

(ii) Child cognitive limitations

(iii) Naturalness

(b) Sociocommunicational mechanisms

(i) Borrowing

(ii) Access to variation principles

(iii) Compartmentalization

(ii) Language variation

Less-marked structures usually sub-

stitute for more-marked structures here as well (see

examples in Chapter 5).

(iii) Crossfield correspondences

The study of language in

all its aspects yields useful insights for an empirical

definition of markedness, as well as for the identifica-

tion of markedness values. If correspondences are found

between implicational relationships and linguistic areas,

it makes sense to seek a common explanation to

account for developments in all domains (see examples

in Chapters 2, 4, 5).

(iv) Crosslinguistic correspondences

The study of crosslinguis-

tic universals and variation yields useful insights for the

identification of markedness values. If correspondences,

as well as the widespread use of less-marked structures,

are found across diverse languages and linguistic systems,

it makes sense to seek common explanations to account

for universal principles of development (see examples in

Chapters 3–5).

(v) Neutralization

A distinction can be lost in a particular

environment; the less-marked form survives. For example,

as Chapter 5 will discuss, children fail to acquire, and

adults neutralize, the distinction between the indicative

and the subjunctive mood; the least-marked indicatives

survive. (See further examples in Chapters 2–5.)

(vi) Frequency

Statistics are used as a discovery procedure,

rather than as a conclusive test for marked values.

Unmarked forms are usually more widely distributed

or frequent than marked forms both within and across

languages. However, because certain languages contain

widely distributed marked forms, statistics can conflict

with markedness values (see examples in Chapter 4).

(vii) Constructional iconicity

Marked structures are usually

‘markered’ by an overt additional form. The most natural

of all linguistic structures are iconically markered; that is

a linguistic complex showing degrees of structural com-

plexity in markering (mark bearing) corresponds to the

degree of markedness, for example ‘here’ vs ‘there by

you’, singular ‘boy’ vs plural ‘boys’. Thus, following the

6

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

principle of constructional iconicity, the words ‘here’

and ‘boy’ are both less marked and less markered than

the complex ‘there by you’ and plural ‘boys’. This is

because of the developmental criterion – more-marked

forms occur later in language development – and the

markeredness criteria – less markered forms are struc-

turally simpler, that is they contain less ‘grammatical

material’. Violations to the principle of constructional

iconicity are few but not unknown (e.g. ‘foot’ vs ‘feet’,

‘mouse’ vs ‘mice’).

(2) Mechanisms of development

(a) Biological mechanisms

(i) Psychological and semantic constraints

These concern

language-specific as well as cognitive difficulties in

the acquisition and learning of structures, showing a

strong bias toward less-marked forms (see examples in

Chapter 5).

(ii) Child cognitive limitations

These concern Piagetian

maturational limitations of cognitive development in

the child (see examples in Chapters 2, 4).

(iii) Naturalness

The natural patterns of a system are char-

acterized formally by Bailey (1982, 1996). Less-marked

structures are more natural than more-marked structures

(see constructional iconicity discussion above and

examples in Chapter 4). Furthermore, the most natural

of all linguistic structures are iconically markered, that

is a linguistic complex showing degrees of complexity in

markering (mark bearing) corresponds to the degree of

markedness. Compare ‘here’ vs ‘there by you’, monoph-

thongs vs diphthongs, and single consonants vs

affricates; the word ‘here’, monophthongs, and single

consonants are less marked and less markered than the

expression ‘there by you’, diphthongs, and affricates.

(b) Sociocommunicational mechanisms

(i) Borrowing

Prestigious elements are borrowed in lan-

guage history and creolization. These can be either more

marked or less marked (see examples in Chapter 2).

Introduction

7

(ii) Access to variation principles

Reduced access to more

formal principles and varieties of a language can lead

to variation and loss of more-marked structures (see

examples in Chapter 5).

(iii) Compartmentalization

Compartmentalization yields

more-marked linguistic systems because neutralization

does not occur. More-marked structures derived from

one lexifier language co-exist with forms derived from

another language (see examples in Chapter 2).

1.5

Outline for the book

Chapter 1 introduces the topic and theoretical assumptions of the

book and presents an articulated model of markedness.

Chapter 2 demonstrates natural morphological processes in the

emergence of the article system in first-language acquisition, cre-

olization, and language history, and examines these developments

in light of Bickerton’s bioprogram. The chapter reveals possible

correspondences in the acquisition, creolization, and history of the

definite as well as the (specific and non-specific) indefinite articles in

Spanish, Portuguese, French, Rumanian, Spanish- and Portuguese-

based creoles (e.g. Papiamentu, Palenquero), koines (e.g. Judeo-Ibero-

Romance), and fusion (e.g. Fronterizo), with some references to other

languages. These developments are explained by a universal hierarchy

of markedness that reflects natural morphological processes.

Chapter 3 examines the emergence of the definite article in language

history from Classical Latin to Vulgar Latin, Spanish, Portuguese, and

Rumanian. Definite articles are created anew from nominative and

accusative demonstratives in the Romance languages. The use of

demonstratives as a source for definite articles has been commonly

characterized as a universal of language, since most languages seem

to prefer this pathway of development. The development of the def-

inite article is explained in terms of factors such as the function of

demonstratives in discourse analysis and grammaticalization theory.

Chapter 4 presents a study of the development of spatial prepos-

itions (e.g. in, on, between, etc.) and temporal adverbs (e.g. yet, again,

no longer, etc.) in first and second language acquisition. It reveals that

these phenomena exhibit similar developmental patterns in English,

French, German, and Spanish, as well as in a number of other

8

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

languages. The developmental path of these phenomena are

explained in terms of universals of markedness because in a natural

environment, less-marked spatial prepositions and temporal adverbs

are acquired earlier by both young children and adult immigrants.

Chapter 5 studies natural morphological processes in the develop-

ment of mood in child language, second language learning, language

variation, and historical change. Correspondences are examined in

the development of mood in Spanish (as spoken in Latin America,

the United States, Spain) and French (Belgium, France). The more-

marked subjunctive appears late in child language; similarly, the

subjunctive is very difficult to learn in second language acquisition,

and it tends to be the subject of neutralization.

Chapter 6 studies cognitive aspects of the Spanish subjunctive. The

uses of the present and past subjunctives are derived from a formula

that captures the mental representation of these tenses. This chapter

also develops a cognitive rule explaining the retention of frequently

used irregular future subjunctives in Spanish legalese. The uses of the

Spanish subjunctive are handled by such cognitive formula and lin-

guistic mechanisms of language use in interaction with markedness

principles.

Chapter 7 summarizes and concludes the text with a review of

each chapter.

Introduction

9

2

Articles: A Result of Natural

Morphological Processes

in First Language Acquisition,

Creolization, and Language

History

2.1

Introduction

This chapter studies natural morphological processes in the emergence

of the article system in first-language acquisition, creolization, and

language history, and examines these developments in light of

Bickerton’s (1981) predictions for specificity in his bioprogram. The

present study reveals that these phenomena exhibit similar develop-

mental patterns for both the definite and the (specific and non-specific)

indefinite articles. The developmental paths of these phenomena are

explained in terms of a universal hierarchy of markedness that

reflects natural morphological processes: less-marked, that is more

natural, structures are acquired earlier by children; they also result

from creolization processes and tend to be the basis of neutralization

and analogical change.

The issues discussed in this chapter with reference to acquisition,

creolization, and language history will be presented first. The article

system will be investigated in various linguistic conditions, including

Spanish, Portuguese, French, Rumanian, Spanish- and Portuguese-

based creoles (e.g. Papiamentu, Palenquero), koines (e.g. Judeo-Ibero-

Romance), and fusion (e.g. Fronterizo), and a number of other

languages. This data is then used to provide evidence supporting

10

the model of markedness in Chapter 1 to account for the natural

morphological developments discussed.

2.1.1

Markedness and the article system

The model of markedness employed here is based on the theory of

markedness developed by Bailey (1996) and Mayerthaler (1988) (see

also Dressler 1985; Faingold 1996b; Wurzel 1989). Below, the identi-

fication of marked structures and the mechanisms of morphological

development in this chapter follow from Table 1.1 in Chapter 1:

(1) Identification of marked structures

(a) System-internal areas

(i) Child language As noted in Chapter 1, markedness theory

states that children select unmarked forms and omit or

replace marked with unmarked structures. It assigns

the feature marked to structures acquired later by chil-

dren, for example indefinite articles corresponding to the

first cardinal number in an earlier stage, while the forms

acquired earlier are unmarked, for example definite articles

corresponding to a demonstrative pronoun.

(b) System-external areas

(i) Language history

As noted in Chapter 1, less-marked

structures substitute for more-marked structures in lan-

guage history.

(ii) Crossfield correspondences

As discussed in Chapter 1,

crossfield correspondences are useful for the identifica-

tion of markedness values. In fact, the search for cross-

field correspondences often reveals general principles,

such as that marked elements are less stable and usually

change before unmarked ones, and that unmarked

structures occur earlier in child language, creolization,

and historical change. For example, to illustrate the latter

principle, less-marked (0)indef (zero indefinite article)

occurs earlier in child language Stage 1 and Rumanian

than more-marked (card)indef (indefinite article corres-

ponding to the first cardinal number in an earlier stage)

in child language Stage 2 and Spanish, Portuguese, and

French.

Articles

11

(iii) Neutralization

As noted in Chapter 1, given a particular

environment, a distinction can be lost, and the unmarked

form survives. For example, children neutralize the dis-

tinction between definite and indefinite article, and the

less-marked definite article survives.

(iv) Frequency

Unmarked forms are in some instances more

widely distributed or frequent than marked terms both

within and across languages. Statistics can conflict with

markedness values. Statistics are used as a discovery pro-

cedure, rather than as a conclusive test of markedness

values.

(v) Constructional iconicity

These are instances of Mayer-

thaler’s (1988) principle of constructional iconicity – the

addition of a mark-bearing element to the simpler

form. The more-marked form bears the marker and is

said to be markered. An overt additional form is present.

The more-marked indefinite article is markered in

English, Spanish, French, Child Language Stage 2, and so

on by a form resembling the first cardinal number, while

other less-marked systems, such as Rumanian and Child

Language Stage 1, have zero forms.

(2) Mechanisms of development

(a) Biological mechanisms

(i) Child cognitive limitations

Young three- and four-year-

olds fail to take into account the cognitive needs of

the listener; they speak from their own point of view,

showing a strong bias toward less-marked definite

articles (Piaget 1953).

(ii) Naturalness

Structures are considered more natural if

they are less marked, and conversely, less natural if they

are more marked.

(b) Sociocommunicational mechanisms

(i) Borrowing As discussed in Chapter 1, borrowed elements

can be either more or less marked. For instance, in decre-

olization, a creole borrows and integrates elements from

its lexifier languages. For example, in Palenquero and

Hawaiian, decreolization processes recently might have

12

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

changed from (0)nonsp (zero non-specific indefinite

article) into more European-like (card)nonsp (nonspecific

article corresponding to the first cardinal number).

(ii) Compartmentalization

As Chapter 1 notes, in compart-

mentalization, neutralization does not occur. More-

marked structures co-exist with less-marked forms

derived from another language.

2.1.2

Definiteness and specificity

In his review of Brown’s (1973) and Maratsos’ (1976) earlier research

on the acquisition of the article system, Bickerton (1981) concludes

that English-speaking children acquire the definite/non-definite, as

well as the specific/non-specific, distinction effortlessly, error-free,

and at a very early age because they are preprogrammed by an innate

bioprogram to do so (rather than learning by means of linguistic data

or experience). Sentences (1)–(3) below illustrate these distinctions

(So called generic NPs are beyond the scope of this study [e.g. ‘the/a

car is a means of transportation’]).

(1) I saw the car (definite/specific)

(2) I saw a car (indefinite/specific)

(3) I can’t buy a car (indefinite/non-specific)

In sentence (1) the NP followed by the definite article the is

presumably known to the listener; in (2) the indefinite article a

marks an indefinite NP, presumably unknown to the listener. Yet in

(2) and (3), because both NPs use the indefinite article a as a marker

of specificity vs non-specificity, the distinction between specific

and non-specific NPs is not systematically distinguished. A closer

analysis of Brown’s (1973), Maratsos’ (1976), Bresson et al.’s (1970),

and Karmiloff-Smith’s (1979) data on the acquisition of the article

system in English and French reveals that children do make signifi-

cant errors, and that these errors are systematic in the sense that they

are the result of both natural morphological constraints affecting

children’s grammars and other linguistic domains.

Bickerton (1981) explains the development of the definite/

indefinite, as well as the specific/non-specific, distinction in terms

of his bioprogram. Accordingly, the emergence of the article system

in, for example, Hawaiian creole does not follow that of its lexifier

Articles

13

languages. This creole is an unusual combination of European

(mainly English, but also Portuguese), Polynesian, Asian, and Pidgin

languages, located on the tropical islands of Hawaii, 2000 miles west

of California and 4000 miles east of Japan. Only one-third of its

about one million speakers are of European descent (see further,

Holm 1988). Table 2.1 displays the article system of Hawaiian creole;

sentences (4)–(6) illustrate these distinctions (Bickerton 1981).

14

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

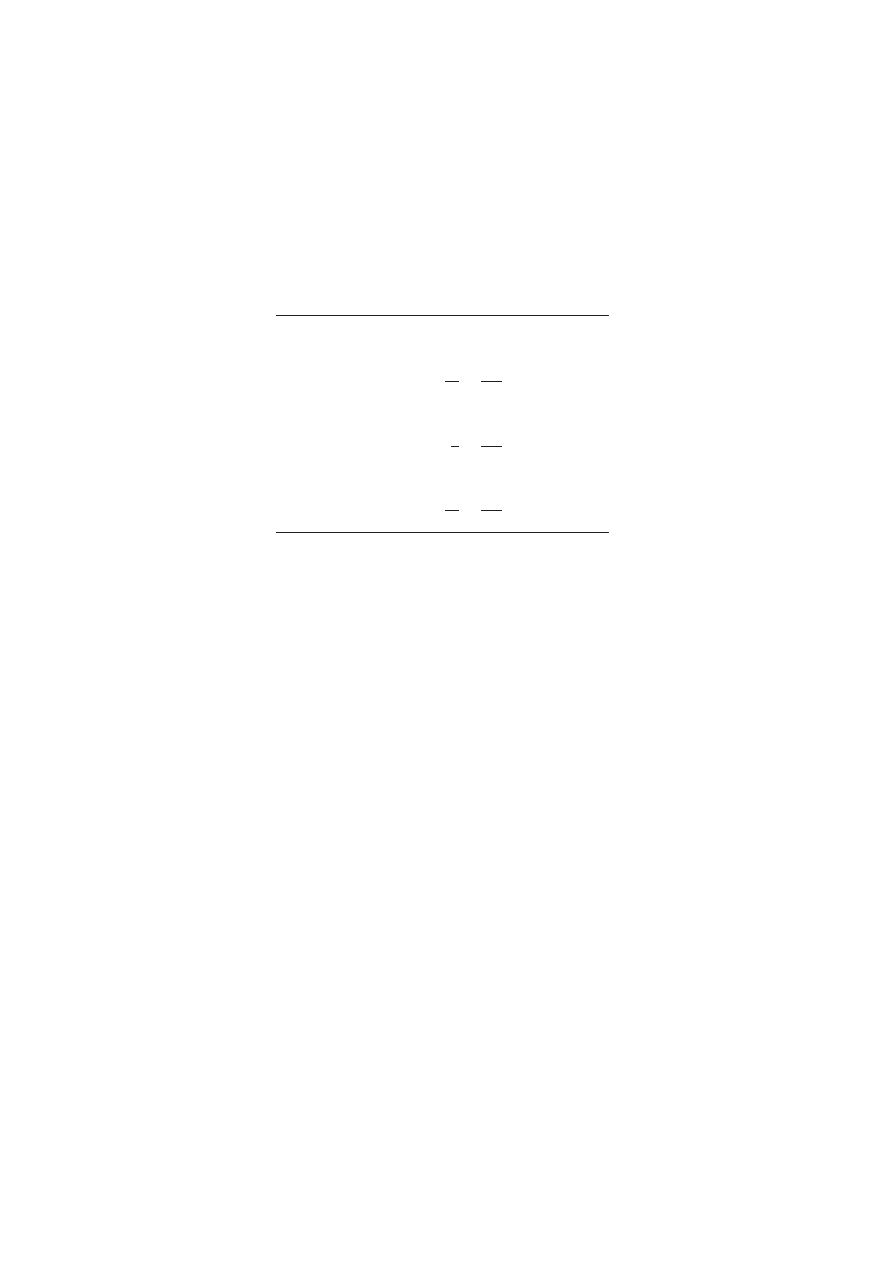

Table 2.1

English-based creoles: articles

in Hawaiian creole (Bickerton 1981)

Definite

Indefinite

Specific

sing.

da

sing.

wan

pl.

da

pl.

0

Non-specific

sing.

0

pl.

0

(4) aefta da boi, da wan jink, daet milk, awl da maut soa.

‘Afterward, the mouth of the boy who had drunk that milk was

all sore’ (definite/specific)

(5) hi get wan blak buk

‘he has a black book’ (indefinite/specific)

(6) bat nobadi gon get ø jab

‘But nobody will get a job’ (indefinite/non-specific)

In sentence (4) the definite article da marks all NPs presumably

known to the listener; in (5) the indefinite article wan marks an

NP presumably unknown to the listener. The specific/non-specific

distinction is systematically marked by wan in (5), compared to

a zero article in (6).

A study of the article system in 18th century Sranan by Bruyn

(1993) does not provide support for Bickerton’s bioprogram. Sranan

is the English-based creole spoken in Surinam (South America,

population 400,000), and the native language of a third of its inhab-

itants, the creoles, and a second language to the rest of the popula-

tion (see further, Bruyn 1993; Holm 1988). Bruyn concludes that

the primary function of determiners in early Sranan is to mark not

specificity but definiteness, since the indefinite marker wan is used

as a marker for both specific as well as non-specific NPs. Table 2.2

displays the article system in 18th century Sranan; sentences (7)–(9)

illustrate these distinctions (see Bruyn 1993 for more examples).

Articles

15

Table 2.2

English-based creoles: articles in Sranan

(Bruyn 1993; Holm 1988)

Definite

Indefinite

Specific

sing.

da – a – 0

sing.

wan – 0

pl.

den – dem – 0

pl.

0

Non-specific

sing.

0

pl.

0

(7) dem putti Jesus na inni da grebbi

‘They put Jesus in the grave’ (definite/specific)

(8) gi mi wan pleti

‘Give me one plate’ (indefinite/specific)

(9) no, mi no wanni wan bigi pleti, gi mi wan pikinwan

‘No I don’t want a big plate, give me a small one’ (indefinite/

non-specific)

As with Hawaiian creole, in (7) the definite article da marks NPs pre-

sumably known to the listener; similarly, in (8) the indefinite article

wan marks an NP presumably unknown to the listener. In contrast,

however, the specific/non-specific distinction is not systematically

marked in 18th century Sranan, since both (8) and (9) can use wan

as a marker of specificity as well as non-specificity. It should be

noted that under certain pragmatic conditions, zero article may

serve as a marker of specificity in Sranan (see further, Bruyn 1993).

In Section 2.3.2 of this chapter, I discuss further the definite/

non-definite as well as the specific/non-specific distinctions with

special reference to the Romance languages; in Section 2.4.1, I show

that the article system in a variety of creoles can be systematically

derived from the theory of natural morphology adopted in this

study.

In creolization (e.g. English that

⬎ Hawaiian, Sranan da ‘the’;

English one

⬎ Hawaiian, Sranan wan ‘a’), as well as in language

history (e.g. Old English se, seo,

ðæt ‘that’ ⬎ English the), definite and

indefinite articles are not derived from their lexifier languages.

Rather, the demonstrative pronoun and the first cardinal number

serve as the source of the definite and indefinite articles respectively

(see Faingold 1996c). In other languages, while the definite article is

markered by a definite structure, indefinite forms are markered by

zero article. For example, (10) below (from Glinert 1989) illustrates

this distinction between the definite and indefinite articles in Hebrew.

(10) hasefer ‘the book’ (definite)

sefer ‘a book’ (indefinite)

Example (10) as well as those examples discussed later in Section

2.3.3.1 are cases of diffusion (Markey 1981). This term is roughly

equivalent to Thomason & Kaufman’s (1988) ‘normal transmission.’

2.2

Sources of data

The database for this paper covers five types of linguistic systems:

early child language, creoles, koines, fusion, and diffusion.

2.2.1

Early child language

Data from child-language case studies are based on several sources

reported in the literature, as follows:

• Brown’s (1973) naturalistic study (spontaneous speech) of the

acquisition of grammatical morphemes by three English-speaking

children, Adam, Eve, and Sarah;

• Maratsos’ (1976) experimental study of the use of definite and

indefinite reference by 40 English-speaking children;

• Karmiloff-Smith’s (1979) experimental study of the acquisition of

articles by French-speaking children aged 3 to 9, living in Geneva,

Switzerland;

• Warden’s (1976) extensive developmental study of children aged

3 to 9 and adults using the indefinite article to introduce new

referents in discourse and the definite article in already identified

referents;

16

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

• Bresson et al.’s (1970) study of the ability of four- and five-year-old

French-speaking children to use the definite and indefinite article;

and

• Faingold’s (1996b) naturalistic study of the phonological and

lexical acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese (see Appendix 3).

2.2.2

Creoles

Data regarding creoles are derived from published research, as follows:

• Holm’s (1988) study of Atlantic creoles, including Portuguese-

based Principe (spoken in West Africa) and French-based Haitian

creoles;

• Ellis’ (1985) study of referentiality and definiteness in Papiamentu;

Faingold’s (1994) study of the article system in creoles and history,

including Spanish/Portuguese-based Papiamentu (in Netherland

Antilles) and Palenquero (in San Basilio, Colombia); Friedmann &

Patino Rosselli’s (1983) and Megenney’s (1986) detailed studies of

Palenquero;

• Bickerton’s (1981) work on Hawaiian and other English-based

creoles; and

• Bruyn’s (1993) study on the article system in 18th century Sranan.

2.2.3

Koines

Faingold’s (1994) study of the article system in creoles and history,

including Judeo-Ibero-Romance, the language of the Spanish and

Portuguese Jews in the Turkish Empire (see further, Faingold 1989,

1996b), provides the data about koines in this study.

2.2.4

Fusion

Fusion data are taken from Faingold’s (1994) study of the article

system in creoles and history, including Fronterizo, the Spanish/

Portuguese-based interlanguage spoken in the Brazilian/Uruguayan

border (see further, Elizaincin et al. 1987; Faingold 1989, 1996b).

2.2.5

Diffusion

Data about diffusion are derived from published research and

grammars of Spanish and Portuguese (Faingold 1994, 1996c), French

(Harris & Vincent 1988), Rumanian (Harris & Vincent 1988), and

English (Hawkins 1978).

Articles

17

2.3

The acquisition, creolization, and history

of the article system

This section discusses developments in the acquisition, creolization,

and history of the article system to provide evidence for the hier-

archy of natural morphological markedness presented later in this

chapter. The extensive amount of data employed in the present study

will be referred to in the discussion of the relevant phenomena. This

chapter covers diffusion, fusion, and creoles (Markey 1981), as well

as other developmental domains such as child language and koines.

Tables 2.3 and 2.4 display the linguistic domains relevant for the

study of natural morphological (as well as phonological, syntactic, and

semantic) processes. Child language, diffusion, koine, fusion, and

creole form a hierarchy of categories of change; salient properties of

this hierarchy are the number of input languages, degrees of access

to the language and culture of the lexifier languages, and degrees of

relexification.

Table 2.4 is an expansion of Markey’s developmental typology

in Table 2.3 and displays linguistic domains relevant to the study

of natural linguistic processes. As indicated in the table, (1) child

language involves the acquisition of one (or more) language(s),

18

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

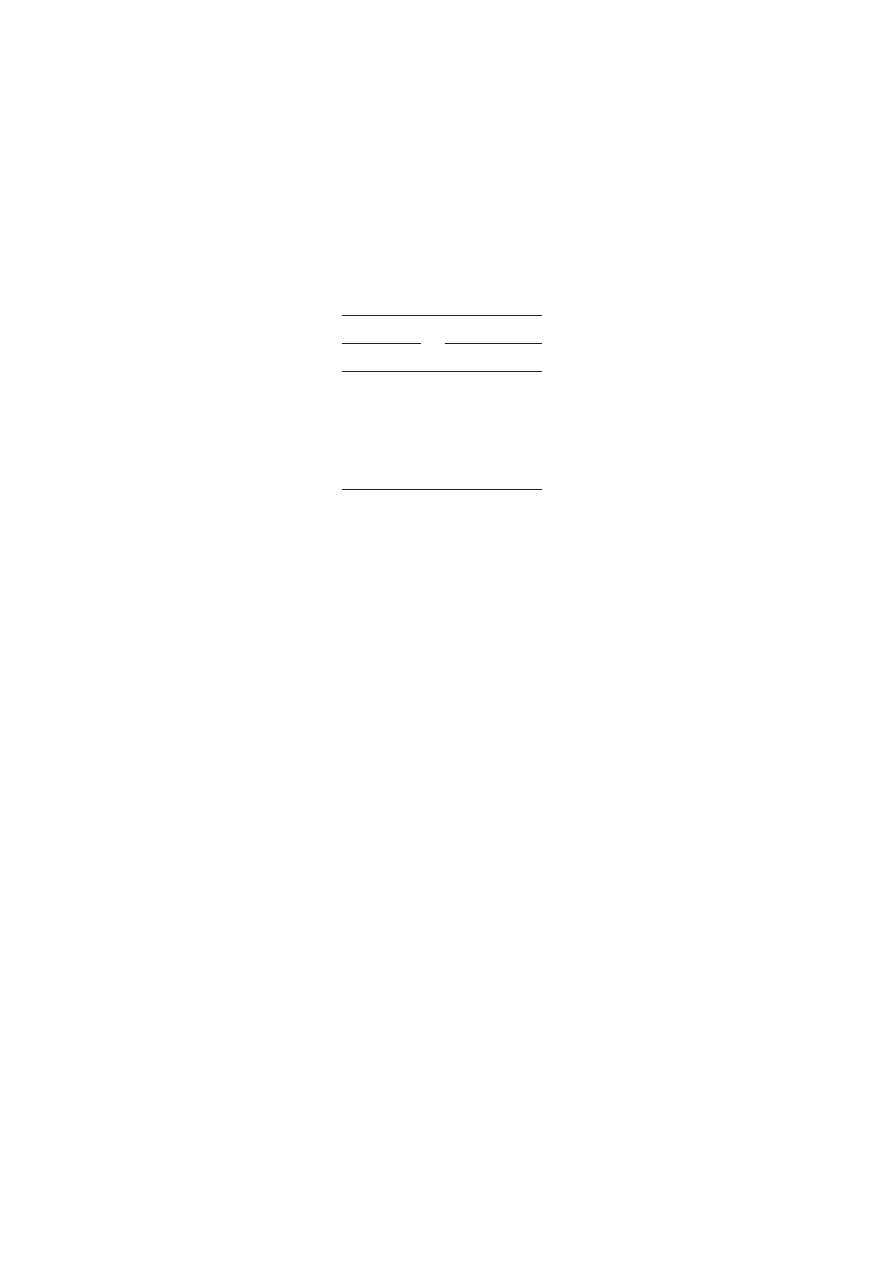

Table 2.3

A developmental typology of linguistic systems (Markey 1981)

Inputs

Continuity

Relexification

(1) Diffusion

1 L

⫹ continuity

⫺ relexification

(2) Fusion

2

⫹ L’s

␣ continuity

relexification

(3) Pidgins/creoles

3

⫹ L’s

⫺ continuity

⫹ relexification

Table 2.4

A revised developmental typology of linguistic systems

Inputs

Continuity

Relexification

(1) Child language

1

⫹ L’s

⫹ continuity

⫺ relexification

(2) Diffusion

1 L

⫹ continuity

⫺ relexification

(3) Koines

2

⫹ D’s or L’s

⫹ continuity

⫺ relexification

(4) Fusion

2 L’s

␣ continuity

relexification

(5) Creoles

3

⫹ L’s

⫺ continuity

⫹ relexification

continuity in language transmission, and no relexification; (2) dif-

fusion includes cases of normal transmission (Thomason &

Kaufman 1988) involving one main lexifier language, and as with

child language acquisition, continuity of transmission and no

relexification. Items (3) koinization and (4) fusion involve two or

more main lexifier languages or dialects, continuity in transmis-

sion and no relexification in the former language, and some (weak)

continuity and relexification in the latter. Usually, (5) creolization

involves three or more main lexifier languages, an abrupt break-

down in language transmission, and extensive relexification.

2.3.1

The article in child language

Although the main topic of this section is the errors children make

in the acquisition of the definite/indefinite, the specific/non-specific

distinction is touched upon as well (see Bresson et al. 1970; Brown

1973; Faingold 1996b; Karmiloff-Smith 1979; Maratsos 1976; Warden

1976). I discuss three types of errors: (1) errors of segmentation, (2)

speaker non-specific and listener specific errors, and (3) speaker spe-

cific and listener non-specific errors. Types (1) and (2) occur sporadic-

ally in child language or are not as well documented in the literature

as type (3), and are explained in terms of intralanguage constraints

affecting the mapping of form and function in the acquisition of the

article system. Type (3) proves to be crucial for my study because

errors of this type are much more widespread and systematic across

subjects as well as crosslinguistically, as a result of both intralanguage

processes and natural morphological constraints explained in terms

of Piaget’s (1953) ‘egocentrism.’

2.3.1.1

Errors of segmentation

The gradual acquisition of the article system starts with errors of

segmentation. For instance, in learning English, Spanish, and

Portuguese, children add an article-like element to nouns. Tables 2.5

and 2.6 display errors of segmentation in English, Spanish, and

Brazilian Portuguese (see Appendix 3).

Data on the acquisition of the article system have been gleaned

from Brown’s (1973) comprehensive study of the acquisition of

fourteen grammatical morphemes by three English-speaking chil-

dren (prepositions in and on, possessive s, plural s, articles a and the,

irregular and regular past tense, irregular and regular third person

Articles

19

pronouns, present progressive, contractible and uncontractible be

auxiliary, and contractible and uncontractible be copula). This is

a longitudinal study of naturalistic (spontaneous) speech covering

a period of years from the time the children were two years old. The

children were tape-recorded every two weeks or less in interaction

with their mothers.

Data on the acquisition of the article system have also been

gleaned from Maratsos’ (1976) experimental study of 40 children

ranging in age from 32 to 60 months who were learning Spanish or

Brazilian Portuguese. Each child was told several stories designed to

elicit either definite or indefinite articles.

In Table 2.5, items (1) and (2), the English-speaking children

studied by Brown (1973) add the indefinite article a, sometimes

uttered as schwa, to common names; similarly in (3), a child adds the

indefinite article a to a proper name (Uncle Clyde). In (4), children

add the definite article the to verbs ending with t or d. Similarly,

in Table 2.6, items (5)–(10), the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking

children add the Spanish-like forms la, e, l and Portuguese-like o, a to

common nouns. Yet, in (11) and (12), the child adds the article-like

forms to Portuguese proper names as well, reflecting the use of the

definite article with proper names by Brazilian-Portuguese speakers

20

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

Table 2.5 Errors of segmentation by English-speaking children (Brown 1973)

(1) that a dog

(2) that a book

(3) that a Uncle Clyde

(4) the is inserted after verb ending in /t/ or /d/.

Table 2.6

Errors of segmentation by Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking

children (Faingold 1996b)

(5) lalu ‘the light’ [Sp. la lus]

(6) ebabi ‘the bambi’ [Sp. el bambi]

(7) loso ‘the bear’ [Sp. el oso]

(8) okokolat ‘the chocolate’ [Port. o sokolat]

(9) apala ‘the ball’ [Port. a bola]

(10) adadis ‘the nose’ [Port. or Sp. a naris or la naris]

(11) akatia ‘the Katia’ [Port. a Katia]

(12) exuti ‘the Ruth’ [Port. a Ruti]

(see Faingold 1996b and Appendix 3). The addition of the article-like

form solves an intralinguistic problem facing the child, the distinction

of common and proper names in English and Spanish. In Brazilian

Portuguese, however, the child faces a more difficult task, since the

input to the child contains articles attached to both proper and com-

mon nouns. In Portuguese, the child must learn to distinguish between

proper and common nouns. This distinction is transparent in Spanish

and English, languages where only common names take articles.

2.3.1.2

Speaker non-specific and listener specific errors

In this section I discuss types of errors occurring when the adult’s and

the child’s knowledge do not converge. The child substitutes the

indefinite for the definite form. According to Maratsos (1976), this

type of error occurs very infrequently. Table 2.7 displays some early

substitutions in the acquisition of the article system.

In items (13)–(17) in Table 2.7, children substitute the indefinite

for the definite article in references already specified by previous

utterances, where a definite article is required or obligatory. The

reason, according to Maratsos, is that children occasionally fail to

keep track of previous unspecified referents and is not that children

are generally ignorant of the definite/indefinite and specific/non-

specific distinctions. Items (18) a heel (of a particular sock) and (19)

a chin (in naming features of a face), rather than the required definite

forms the heel and the chin, are errors of entailment, ascribed to the

child’s lack of knowledge of part-whole assemblages (Maratsos 1976).

Articles

21

Table 2.7

Speaker-specific and listener-specific errors (Brown 1973; Maratsos

1976)

(i) Errors of tracking Children aged 3 (Brown 1973)

(13) I don’t like a crust

(14) Let me see you ride a bike

(15) We saw them in a zoo

Children aged 3 (Maratsos 1976)

(16) He’s a witch

(17) It’s a gun

(ii) Errors of entailment

(18) Where’s a heel?

(19) [That’s] a chin

2.3.1.3

Speaker specific and listener non-specific errors

As in 2.3.1.2, this is a type of error that occurs when the child’s and

the adult’s knowledge do not converge. In 2.3.1.3, however, the child

substitutes the definite for the indefinite article. As I show below, this

type of error has been documented extensively and appears to be

very widespread cross-linguistically. Tables 2.8 and 2.9 display some

early substitutions in the acquisition of the article system.

22

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

Table 2.8

English-speaking children aged 3: speaker specific and listener

non-specific (Brown 1973; Maratsos 1976)

Children aged 3 (Brown 1973)

(20) Child:

The cat’s dead

Mother:

What cat?

(21) Child:

And the monkey hit the leopard

And that the bowl

Mother:

What bowl?

(22) Child:

Where’s the stool?

Mother:

There’s one over there

Children aged 3 (Maratsos 1976)

(23) The monkey jumped into the car

Table 2.9

French-speaking children aged 3 to 9: speaker specific and listener

non-specific (Bresson et al. 1970; Karmiloff-Smith 1979)

Children aged 3 to 9 (Karmiloff-Smith 1979)

(24) la fille a poussé X

‘the girl pushed X’

(25) la fille a poussé X aussi

‘the girl pushed the X also’

(26) la fille a poussé la même X

‘the girl pushed the same X’

Children aged 4 to 5 (Bresson et al. 1970)

(27) Experimenter:

Qui est parti?

‘Who went away?’

Child:

les moutons

‘the sheep’

(28) Experimenter:

Qui est restes?

‘Who stayed?’

Child:

les cochons

‘the pigs’

Again, data include Brown’s (1973) and Maratsos’ (1976) studies of

English-speaking children aged 3. Data were gleaned also from

Karmiloff-Smith’s (1979) large cross-sectional experimental study of

the functional acquisition of the article system by Swiss French-

speaking children aged 3 to 9, and from Bresson et al.’s study of

4- and 5-year-old French-speaking children’s ability to produce defin-

ite and indefinite articles in a limited set of contexts.

In Tables 2.8 and 2.9, items (20)–(28), English- and French-speaking

children substitute the definite (English the, and French la, les) for

the indefinite (English a, and French une, des). These errors have

been extensively documented by researchers who propose a less

error-prone type of acquisition (e.g. Brown 1973; Maratsos 1976; see

also, Bickerton 1981), as well as by those claiming that the article

system is not fully acquired as late as age 9 (e.g. Karmiloff-Smith

1979; Warden 1976). In addition, Zur (1983) reports the tendency of

Hebrew-speaking children to overuse the Hebrew definite article ha

(see Berman 1985).

Karmiloff-Smith (1979), Bresson et al. (1970), Brown (1973) and

Maratsos (1976) suggest that the errors discussed in Section 3.1 of

this chapter are a result of the child’s failure to take into account the

cognitive needs of the listener; instead, children speak from their

own point of view, what Piaget (1953) terms ‘egocentrism.’

Thus, a very substantial amount of evidence indicates inadequate

learning of the article system in early child language, showing a

strong bias toward definite references. The studies reviewed show

that young children do not reliably map form and function in

the acquisition of the article system. The errors of acquisition dis-

cussed in Section 2.3.1.3 substantiate a hierarchy of morphological

markedness applying not only to child language but also to other

linguistic domains; these errors reveal constraints on neutralization

processes affecting the direction as well as the order of acquisition of

less-marked and more-marked morphological structures.

2.3.2

The article in creolization

As with English-based Hawaiian and Sranan creole, the article systems

of Romance-based creoles such as Haitian, Principe, Papiamentu, and

Palenquero do not follow their lexifier languages. Table 2.10 displays

the article systems of Haitian, Principe, Papiamentu, and Palenquero

creoles.

Articles

23

2.3.2.1

Haitian creole

French-based Haitian creole is spoken by more than five million

people on the island of Hispaniola, which Haiti shares with the

Dominican Republic. The island was first settled by a mixture of

French, English, and African bucaneers (pirates). Over the next

century, Haiti was settled by the French, who brought African slaves

to grow indigo and sugar cane under the protection of the French

West Indian Company and the French Crown (see further, Holm

1988).

In Table 2.10(a) the definite article a – la in Haitian creole seems to

correspond to French demonstrative la ‘there’. Note that the definite

article is located after (rather than before) the NP, as illustrated in

examples (14) and (15) below (from Holm 1988).

(14a) istwa a ‘the story’

(14b) istwa la ‘the story’

(15) istwa ‘a story’

24

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

Table 2.10

Romance-based creoles

Specific

Non-specific

Definite article

Indefinite article

(a) French-based creoles: articles

in Haitian creole (Holm 1988)

sing.

a – la

sing.

0

sing.

0

pl.

a – la

pl.

0

pl.

0

(b) Portuguese-based creoles: articles

in Principe creole (Holm 1988)

sing.

se

sing.

0

sing.

0

pl.

se

pl.

0

pl.

0

(c) Spanish/Portuguese-based creoles:

articles in Papiamentu

(Faingold 1994)

sing.

e

sing.

un

sing.

0

pl.

e

pl.

0

pl.

0

(d) Spanish/Portuguese-based creoles:

articles in Palenquero

(Faingold 1994)

sing.

0 – e

sing.

un – ma

sing.

0

pl.

ma

pl.

un ma – um ma pl.

0

According to Holm (1988), this is the effect of the Yoruba (West

Africa) substratum on Haitian creole, since the definite article in

Yoruba is post-nominal as well. Similarly, in Table 2.10(a), zero is

grammaticalized as a marker of the indefinite article (rather than

the first cardinal number); according to Holm this is also a reflex of

the Yoruba substratum. Recall that, in contrast, both English-based

Hawaiian and Sranan grammaticalize the first cardinal number into

the indefinite article; and, as I show below, both Spanish/Portuguese-

based Papiamentu and Palenquero present an indefinite article based

on the first cardinal number. Examples (16) and (17) (from Holm

1988) illustrate the definite article in Yoruba.

(16) okunrin naa ‘the man’

(17) okunrin ‘a man’

2.3.2.2

Principe creole

Principe is a Portuguese-based creole spoken in the island of the

same name, 100 miles north of the island of Sao Tome (West Africa).

Principe was settled in the 16th century by the Portuguese who

brought slaves from Guinea, Gabon, and Angola, as well as

Portuguese settlers (mostly peasants, Jews, and convicts) to grow sugar

cane and, later in the 19th century, coffee and cacao (see further,

Holm 1988).

The article system in Principe closely parallels that of Haitian

creole. As with Haitian, in Table 2.10(b) the definite article se in

Principe seems to correspond to the Portuguese demonstrative esse

‘that’; the definite article is also post-nominal, and the indefinite

article is zero. Examples (18) and (19) (from Holm 1988) illustrate the

definite/non-definite distinction in Principe.

(18) mi se ‘the man’

(19) mi ‘a man’

According to Holm (1988), post-nominal definite and zero indefin-

ite articles are a reflex of the Yoruba substratum.

In both Haitian and Principe creole, the input to the definite article

is the demonstrative pronoun (rather than French or Portuguese

definite articles); this is the result of presumably universal processes

affecting the grammaticalization of articles in discourse (see further,

Faingold 1994, 1996a).

Articles

25

Tables 2.10(a) and 2.10(b) do not lend support to Bickerton’s

bioprogram because the specific/non-specific distinction is not

systematically marked in Haitian and Principe creole: the indefinite

article zero is used to mark both specific as well as non-specific NPs.

Recall that, similarly, in English-based Sranan, the specific/non-

specific distinction is not systematically marked because Sranan uses

the indefinite marker wan for both specific and non-specific NPs.

2.3.2.3

Papiamentu and Palenquero creoles

Papiamentu is a Spanish/Portuguese-based creole spoken by over

200,000 people in the islands of Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire (Nether-

land Antilles). The Dutch conquered and took over from Spain the

islands in the 17th century and used Curaçao as a storehouse for the

distribution of slaves to the American mainland. Over the next two

centuries, a mixture of Iberian languages and other European and

African languages arose as the result of contact between the Dutch,

Portuguese-speaking Sephardic Jews, African slaves, and more

recently, Spanish-speaking South Americans and English-speaking

Americans (see Faingold 1996b).

Palenquero is a Spanish/Portuguese-based creole spoken mostly by

old people in the village of Palenque de San Basilio (in Colombia).

Like other palenques, or fortified villages, in the area, San Basilio was

built by fugitive slaves called maroons. In the 17th century, the

Spanish gave the Palenqueros the right to self-government in

exchange for an end to the raids on the colonists and giving shelter

to other escaped slaves. Palenquero is thus the result of contact

between speakers of African and Portuguese pidgin with speakers of

South American Spanish (see Faingold 1996b; Schwegler 1998).

In Tables 2.10(c) and 2.10(d), the definite article e in Papiamentu

and Palenquero seems to correspond to Spanish and/or Portuguese

demonstratives ese and esse ‘that’. In Palenquero, the definite singular

e is in variation with zero and plural ma, from Spanish mas and/or

Portuguese mais ‘more’. Sentences (20)–(24) illustrate the use of the

definite article in Papiamentu and Palenquero (see Faingold 1994;

Maduro 1987).

Papiamentu

(20) i e pasashi kuantu e ta?

‘. . . and how much does the ticket cost?’

26

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

(21) e hombernan ta bai hasi un desastre kune

‘The men make a disaster’

Palenquero

(22) i pasaje kuanto jue?

‘How much does the ticket cost?’

(23) e dia y a ase

‘The day that I did . . .’

(24) ma ombre aselo desastre

‘The men make a disaster’

In Papiamentu and Palenquero, as predicted by Bickerton’s biopro-

gram, the specific/non-specific distinction is systematically markered

by the use of zero specific marker for non-specific NPs, compared

to the first cardinal number for specific NPs. Sentences (25)–(30)

illustrate the use of the indefinite article as well as the specific/non-

specific distinction in Papiamentu and Palenquero (see Faingold

1994; Maduro 1987).

Papiamentu

(25) el a sali ku un pieda

‘He went with a stone’ (indefinite/specific)

(26) mi tin kata

‘I have letters’ (non-markered/specific plural)

(27) nabes ma kada preguntante tin chens

‘One more time each questioner has a chance’ (non-markered/

non-specific)

Palenquero

(28) el a se sali ku un piega

‘He went with a stone’ (indefinite/specific singular)

(29) i a tene un ma kata

‘I had letters’ (indefinite/specific plural)

(30) ni me a mandao kata

‘He did not send a letter’ (non-markered/non-specific)

Certain studies on Palenquero (e.g. Megenney 1986) have found

that the specific/non-specific distinction in this creole works as in

standard Spanish; that is it is not systematically markered by zero

Articles

27

non-specific vs first cardinal specific. This is probably the result of

decreolization processes, which might have recently changed non-

specific zero into a more Spanish-like structure for certain speakers

of Palenquero. Similarly wan can now be non-specific for modern

speakers of Hawaiian creole (Bailey personal communication). Other

studies of Palenquero (e.g. Friedmann & Patino Rosselli 1983;

Schwegler n.d.) seem to confirm the bioprogramatic distinction

between specific and non-specific NPs.

2.3.2.4

Neutralization in creole article systems

Another feature of the bioprogram affecting the article system of all

creole languages is neutralization of gender and number markers.

Compare French definite articles le, la, les, Spanish el, la, los, las, and

Portuguese o, a, os, as with Haitian a – la, Papiamentu e, Palenquero

zero – e – ma, and Principe se; and French indefinite un, une, des,

Spanish un, una, unos, unas, and Portuguese um, uma, uns, umas with

Haitian zero, Papiamentu un, zero, Palenquero un, ma, un ma, and

Principe zero (see Table 2.10).

2.3.3

The article in language history

This section details the developments in the history of the article

system, including cases of diffusion, koinization, and fusion in lan-

guages such as French, Rumanian, Spanish, and Portuguese, as well

as in more modern daughter languages of Spanish and Portuguese,

such as Judeo-Ibero-Romance and Fronterizo.

Judeo-Ibero-Romance and Fronterizo have been characterized as

koines, which are the result of slow and gradual contact between

mutually-intelligible varieties of closely-related languages or dialects

of more or less equal prestige, and which show loss of marked and

minority forms (Crews 1930; Sala 1971; Trudgill 1986; Wagner 1930).

However, as I have shown in earlier work (Faingold 1989, 1996b),

certain dialects of Judeo-Ibero-Romance from the Balkans and the

Eastern Turkish Empire (Istanbul, Salonika, and Bitola) are charac-

terized as examples of fusion phenomenon, which refers to a

linguistic system that is derived from at least two source languages

and that shows compartmentalization and retention of marked and

minority forms. Yet the Bitola dialect of Judeo-Ibero-Romance,

spoken in Macedonia, Yugoslavia, is better characterized as a case of

28

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

morphological koinization because more-marked and invariant

structures do not occur in the development of its article system. In

contrast, Fronterizo represents a case of morphological fusion

because its article system shows compartmentalization, as well as

retention of more-marked forms derived from its source languages,

Spanish and Portuguese.

2.3.3.1

Diffusion

These are cases of normal transmission (see Thomason & Kaufman

1988). The bioprogram does not appear to be as active in language

history as it is in creolization. In language history, there is less

neutralization of gender and number, and non-specific zero markers

do not emerge. Table 2.11 displays the article systems in Rumanian,

French, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Articles

29

Table 2.11

History: articles in the Romance languages

Definite article

Indefinite article

(a) Articles in Rumanian (Harris & Vincent 1988)

masc. sing.

ul – le

masc. sing.

0

masc. pl.

i

masc. pl.

0

fem. sing.

ua – a

fem. sing.

0

fem. pl.

le

fem. pl.

0

(b) Articles in French (Harris & Vincent 1988)

masc. sing.

le

masc. sing.

un

masc. pl.

les

masc. pl.

des

fem. sing.

la

fem. sing.

une

fem. pl.

les

fem. pl.

des

(c) Articles in Spanish (Faingold 1994)

masc. sing.

el

masc. sing.

un

masc. pl.

los

masc. pl.

unos

fem. sing.

la

fem. sing.

una

fem. pl.

las

fem. pl.

unas

(d) Articles in Portuguese (Faingold 1994)

masc. sing.

o

masc. sing.

um

masc. pl.

os

masc. pl.

uns

fem. sing.

a

fem. sing.

uma

fem. pl.

as

fem. pl.

umas

In contrast with the creole languages discussed in Section 2.3.2,

in Table 2.11, the article systems of Rumanian, French, Spanish,

and Portuguese are more marked because neutralization does

not occur. Similarly, the specific/non-specific distinction in

French, Spanish, and Portuguese is not markered with zero article

but with a copy of the indefinite article (see further, Faingold

1994).

2.3.3.2

Koinization

Judeo-Ibero-Romance is the language spoken by Iberian Jews

who settled in Europe (particularly in the Turkish Empire, the

Balkans, Italy, and Holland), South and North America, North

Africa, and the Middle East, after the expulsions from Spain in

1492 and Portugal in 1496. This section deals with the dialect of

Judeo-Ibero-Romance spoken in Bitola (Macedonia, Yugoslavia),

which is a mixture of Portuguese and Castilian Spanish as

well as non-Castilian dialects of Spanish (see further, Faingold

1996b). This linguistic system represents a case of koinization,

as defined above. Table 2.12 displays the article system of Judeo-

Ibero-Romance.

In Table 2.12, neutralization of gender and number fails to occur

in Bitola Judeo-Ibero-Romance. Notice, however, that as a result of

koinization processes, the article system of Judeo-Ibero-Romance

suffers phonological neutralization: the more-marked Spanish mid-

vowels [e], [o] change to less-marked [i], [u] in il, lus, unus (see

further, Faingold 1996b). The non-specific article is a copy of the

indefinite forms un, unus, une, unes.

30

Grammar in Spanish and Romance Languages

Table 2.12

Spanish/Portuguese-based koines: articles in

Judeo-Ibero-Romance (Faingold 1994)

Definite article

Indefinite article

masc. sing.

il

masc. sing.

un

masc. pl.

lus

masc. pl.

unus

fem. sing.

la

fem. sing.

une

fem. pl.

las

fem. pl.

unes

2.3.3.3

Fusion

Fronterizo is a somewhat stable variety (or varieties) of Spanish in

contact with Portuguese and is spoken in the Brazilian/Uruguayan

border by people who tend to have some knowledge of both

Spanish and Portuguese. In much of this area, the Spanish of the

Portuguese-speaking Brazilians is weaker than the Portuguese of the

Uruguayans (see further, Faingold 1996b; Elizaincin et al. 1987;