C

LASSIFICATION BY

M

C

K

ENZIE

M

ECHANICAL

S

YNDROMES:

A S

URVEY OF

M

C

K

ENZIE-

T

RAINED

F

ACULTY

Stephen May, MSc

a

A

BSTRACT

O

bjective

:

The purpose of this survey was to identify the percentage of patients with spine pain who can be classified by

McKenzie-trained faculty as having one of either derangement, dysfunction, or postural syndromes.

M

ethods

:

McKenzie Institute International faculty members in 20 countries, who are highly trained and are experienced

users of the classification system, recorded details on 15 consecutively discharged patients.

R

esults

:

Responses were received from 57 therapists in 18 countries (89% of potential sample), and details were

collected on 607 patients with spine pain. Eighty-three percent were classified in one of the mechanical syndromes;

derangement was the most common syndrome. Therapists recorded a mechanical classification in a mean of 82%

(SD, 15.1; range, 44%-100%) of their patients with spine pain.

C

onclusions

:

For this study, the McKenzie mechanical syndromes were commonly diagnosed in a large consecutive

group of patients at multiple sites by experienced therapists. This classification system may have valuable clinical use in

managing patients with spine pain. (J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006;29:637-642)

K

ey Indexing Terms: Pain; Classification; Prevalence; Back pain

I

n patients with low back pain, the terms dnonspecificT

or dmechanicalT back pain are used to describe an entity

whose pathoanatomical etiology is unknown.

experts argue that specific structural pathology can be

diagnosed using intra-articular or disk-stimulating injec-

tions

; however, such interventions require specialist clini-

cians and facilities and cannot realistically be made

available to all. Although some recent studies suggest that

specific structural pathology can sometimes be diagnosed

by physical examination in some patients,

such reports are

unusual. In general, attempts to search for the specific causal

mechanism for back pain have been largely inconclusive.

As a consequence, most classification systems do not use

specific pathological subgroups. Of 32 classification sys-

tems identified by a systematic review, 15 were classified by

clinical features, 7 by psychological features, 1 by work

status, 4 by health status, and only 6 by pathoanatomy.

general, the critical appraisal found the pathoanatomical

classification systems to be among the weaker systems

according to the criteria used.

A number of classification systems for spinal problems

have been described.

Classification systems provide

several advantages.

They help in making clinical

decisions; they may help in establishing prognosis and are

likely to lead to more effective treatment if patients are

treated with regard to classification. There is initial evidence

that has begun to show that patients treated in accordance

with their classification have better outcomes than patients

who are treated with what is considered best practice

according to contemporary guidelines

dence for the value of the McKenzie classification system.

Classification systems also aid in communication between

clinicians; they could improve our understanding of differ-

ent subgroups and should be used in the conduct of audit

and research. Unfortunately, there exist a wide variety of

spinal pain classifications from which to choose,

more systems continue to appear. Discussion about the

strengths and weaknesses of different types of classification

systems is provided in these reviews.

For a classification system to be of clinical use, it must

have certain characteristics.

First, different clinicians must

be able to reliably classify patients into the different

subgroups so that we can be certain that they actually

exist. Second, it must be verified that the classification

system has clinical application in a significant proportion

of the patient population. Finally, the value of the

classification system needs to be determined by under-

taking efficacy studies with and without classification. The

first stage requires reliability studies; the second stage,

cross-sectional prevalence studies; and the third stage,

637

a

Faculty of Health and Wellbeing, Sheffield Hallam University,

Collegiate Crescent Campus, Sheffield, UK.

Submit requests for reprints to: Stephen May, MSc, Faculty of

Health and Wellbeing, Sheffield Hallam University, Collegiate

Crescent Campus, S10 2BP Sheffield, UK

(e-mail: s.may@shu.ac.uk).

Paper submitted November 24, 2005; in revised form April 21,

2006; accepted June 11, 2006.

0161-4754/$32.00

Copyright

D 2006 by National University of Health Sciences.

doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.08.003

randomized controlled trials. Reliability is necessary to

ensure consistent identification between clinicians. How-

ever, if reliability were perfect but the classification system

only applied to a small proportion of all potential patients,

its clinical use would be limited. For a system to be

clinically useful, it must be able to incorporate a substantial

proportion of all potential patients.

first described a classification system as it

applied to the lumbar spine, then related the same

classification system to the cervical and thoracic spines,

and finally to extremity musculoskeletal problems.

lowing wide usage, minor modifications were made to

the classification system,

which included further detail

on nonmechanical problems that did not fit one of the

mechanical syndromes. The McKenzie classification of

Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy is now commonly used,

as documented from the United Kingdom and the United

States.

The system involves the use of 3 mechanical

syndromes that are distinguished by their different symptom

and mechanical responses to repeated end-range movement

or sustained postures: derangement, dysfunction, and

postural syndromes.

Derangement is identified by a report of centralization,

abolition, or decrease of symptoms and an increase in range

of movement in response to repeated movements or

sustained postures. Dysfunction is identified by intermittent

pain consistently produced at a restricted end-range with no

rapid change of symptoms or range. Adherent nerve root is a

particular type of dysfunction following a history of

radicular pain, with intermittent pain in the limb. Postural

syndrome is identified by intermittent pain produced only

by sustained sitting, which is abolished by posture

correction, with the rest of the physical examination being

normal.

Patients that do not show responses that permit

classification in one of the mechanical syndromes are

classified as dotherT or nonmechanical syndrome. This

includes patients with the following problems: chronic pain

state, mechanically inconclusive, stenosis, trauma, sacroiliac

joint, dred flagT pathology, and after surgery.

Regarding the clinical use of the system, a number of

studies involving patients with lumbar and cervical spine

problems have established the reliability of categorization or

components of categorization, such as centralization.

Education and familiarity with the system may be important

in the therapists’ ability to use the system reliably. Separate

studies have shown those who have limited exposure to

Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy show no or moderate

reliability,

whereas well-trained therapists show good

to excellent reliability.

However, this has not been di-

rectly investigated.

The extent to which the classification system is

applicable to patient populations can be indirectly deter-

mined from cohort and reliability studies. Centralization,

which is only found in derangement syndrome, has been

commonly described in patients with back pain, reported in

70% of 731 patients with subacute back pain and in 52% of

325 patients with chronic back pain across 9 studies.

derangement syndrome is described as the most common of

the mechanical syndromes.

A directional preference,

found in the derangement syndrome, has been elicited in

74% of subjects in a randomized controlled trial.

reliability studies, the proportion of patients that could be

classified in one of the mechanical syndromes has varied in

different studies but has been generally high: 68%,

Only one study has directly

looked at the question; it attempted to classify a cohort of

patients with back pain into the McKenzie categories.

522 new patients referred, 307 (58%) were classified into

McKenzie syndromes, whereas 215 (42%) were not.

Consequently, it seemed valuable to determine the

number of patients who can be categorized within the

McKenzie mechanical syndromes and to do this with

therapists who are trained and are familiar with the

system. Therefore, a survey of mechanical and nonmechan-

ical diagnoses was made of the McKenzie teaching faculty,

all who have passed the diploma exam, which is the

highest attainment within the McKenzie educational pro-

gram. Classification is used to guide treatment and is stable

once made; however, at the initial appointment, a provi-

sional classification is made, which is confirmed on

subsequent visits. Therefore, the information was collected

at discharge. The aim of the study was to identify the

percentage of patients with spine pain that can be classified

by McKenzie-trained faculty as having one of the mechan-

ical syndromes.

M

ETHODS

Therapists

Only faculty members of the McKenzie Institute Interna-

tional were recruited for the survey. This group was

experienced with the system of mechanical diagnosis and

therapy, and all had achieved a diploma in mechanical

diagnosis and therapy, which is the highest award in the

educational system. This group was chosen because the

literature suggested that reliability of assessment would be

high in this group.

At the time the survey was conducted, the international

teaching faculty numbered 70 individuals in 20 countries.

Up to 3 repeat e-mailings were conducted over a 6-month

period between October 2003 and March 2004. There was

failure of delivery (3), change of status (3), or unclear results

(2) in 8 individuals and no data from 5 individuals.

Responses were received from 57 faculty members in 18

countries—81% of total population and 89% of potential

population who could be contacted and were still working

as part of McKenzie Institute International. The details

about therapists’ age, sex, experience, practice setting, and

patient referral pattern are provided in

.

638

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

May

October 2006

McKenzie Classification

Data

Anonymity of patient data was retained at all times, as

participating therapists extracted data from their patient

notes on to the data collection sheets at discharge, with the

researcher never having access to individual patients’ notes.

The McKenzie assessment sheet allows for recording of the

items requested; hence, data extraction was straightforward.

Participants were instructed to provide data on the next 15

consecutive patients discharged from receipt of request for

data. The importance of capturing all consecutive patients

was stressed to all participants. They were asked for the

following information:

! Information about therapist (

)

! Demographic information about patients (

)

! Site of symptoms

! Mechanical or nonmechanical diagnosis

Data collection forms were provided to clarify the type of

data that was required.

Participants were asked to provide basic demographic

data about the patients: age, sex, work status, acuity/

chronicity. Four respondents failed to provide these data;

consequently, the numbers for demographic details are less

than diagnostic information. Mechanical or nonmechanical

diagnosis was collected on a sheet that allowed classifica-

tion to be matched with the site of problem. The end-result

matched site and mechanical or nonmechanical syndrome

(eg, back/derangement, indicating that the patient had back

pain and was classified mechanically and treated as a

derangement). Not all participants returned details on

15 patients. There were data on 849 patients, of which

607 had spinal pain and 242 did not. This article describes

only the consecutive patients with spinal pain.

The operational definitions and descriptions for the

mechanical and nonmechanical disorders have been pub-

lished in work that was familiar to all participants.

Up to 3

reminders were sent to maximize responses. Mailing was

done in batches, and data collection continued over a period

of 6 months. The mean time it took therapists to collect the

data was 3.4 weeks (SD, 1.5; range, 1-8). The collected data

were entered on an Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash,

USA) spreadsheet and presented as descriptive data. The

Sheffield Hallam University ethics committee approved the

study before data collection commenced.

R

ESULTS

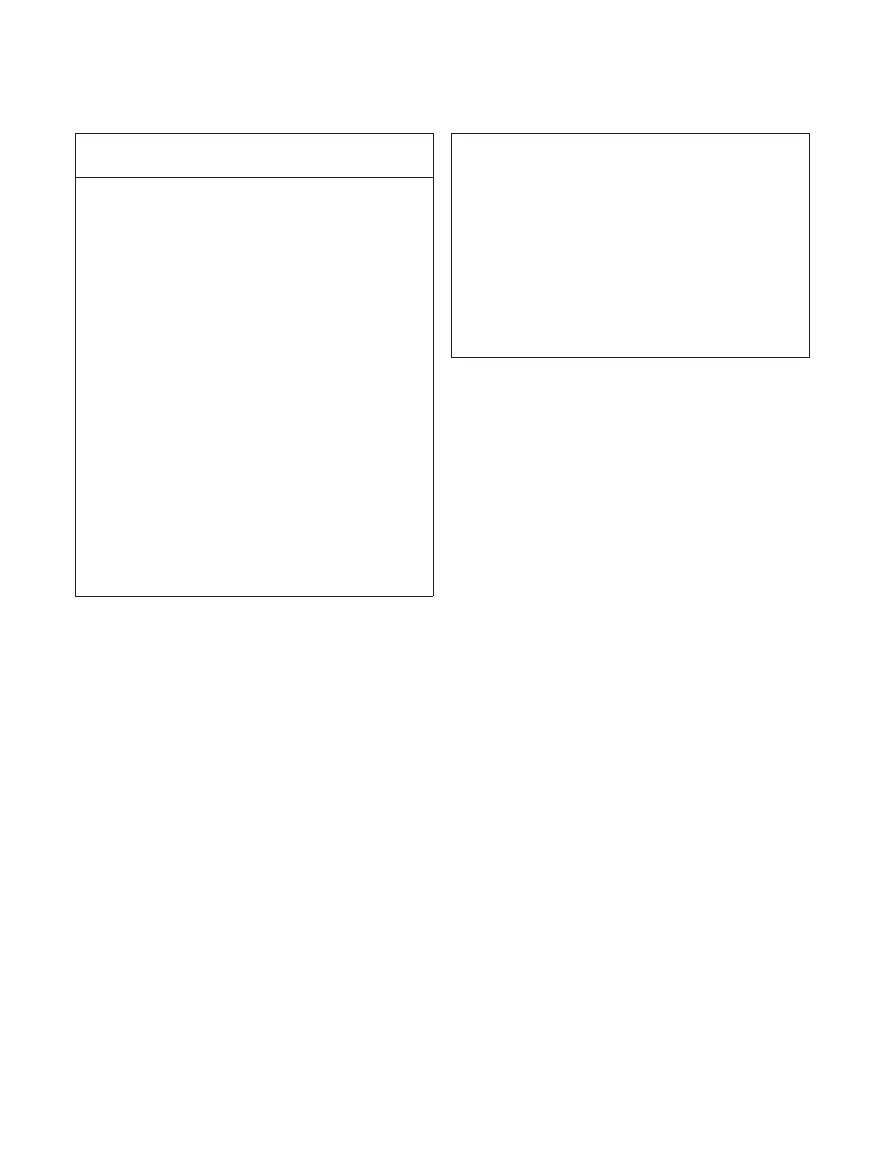

Therapist details are provided in

. Demographic

data were available on 578 patients with spine pain (

and syndrome classification was available for 607 patients

with spine pain. Therapists saw a mean of 11 patients with

spine pain (SD, 3.3; range, 4-17). Therapists recorded a spinal

mechanical classification (derangement, dysfunction, pos-

tural syndrome) in a mean of 9 patients (SD, 3.8; range, 3-17),

a spinal nonmechanical classification in a mean of 2 patients

(SD, 1.5; range, 0-5), and a nonspinal problem in a mean of

4 patients (SD, 3.2; range, 0-11). In patients with spine pain

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical details on 578

a

spinal patients

Sex, n (%)

Male

257 (44)

Female

321 (56)

Age, mean (SD)

43.2 years (13.4)

Symptom duration, n (%)

Acute (b7 d)

86 (15)

Subacute (b7 wk)

174 (30)

Chronic (N7 wk)

318 (55)

Work status, n (%)

Working

378 (65)

Working, sick

80 (14)

Retired

75 (13)

House person/student

45 (8)

Total

578

a

Missing data = 29.

Table 1.

Therapist details

Responders

(n = 57)

Nonresponders

(n = 13)

a

P

b

Sex, n (%)

Male

38 (67)

7 (64)

.445

Female

19 (33)

4 (36)

Age, mean (SD)

45 (6)

44 (7)

.473

Years since

qualification

c

,

mean (SD)

21 (7)

16 (7)

.016

Years since joining

MII faculty

c

,

mean (SD)

8 (5)

9 (7)

.770

No. of countries

d

18

7

Type of practice,

n (%)

.499

Private clinic

37 (65)

6 (55)

GP practice

2 (4)

1 (9)

Hospital outpatients

7 (12)

1 (9)

Specialist clinic

8 (14)

2 (18)

Rehabilitation center

3 (5)

Pain management

clinic

1 (9)

Main referral base

(%)

.115

Self-referral

33

18

GP

51

45

Orthopedics

10

18

Rheumatology

2

Other

4

18

MII, McKenzie Institute International; GP, general practitioner.

a

Missing data = 2.

b

Differences between responders and nonresponders tested with Mann-

Whitney U test or v

2

as appropriate.

c

At 2004.

d

Not tested for significance.

May

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

McKenzie Classification

Volume 29, Number 8

639

only, therapists recorded a mechanical classification in a

mean of 82% of their patients (SD, 15.1; range, 44%-100%).

Five hundred four (83%) of all spinal patients were

classified in 1 of the mechanical syndromes. Derangement

was by far the commonest mechanical classification (78% of

all patients); far fewer patients were classified with dysfunc-

tion (3%), adherent nerve root (1%), or postural syndromes

(1%). Seventeen percent of all spinal patients were given a

nonmechanical classification. These 101 patients were given

the following other classifications: mechanically inconclu-

sive (6% of all patients), chronic pain state (b4%), red flags

(b1%), stenosis (N1%), sacroiliac joint (1%), trauma (N1%),

spondylolisthesis (b1%), and after surgery (b2%).

D

ISCUSSION

The principal finding of this survey of the use of the

McKenzie classification system was the high prevalence of

mechanical syndromes in the population studied; patients

that did not fit one of the mechanical syndromes were

readily classified under one of the other specific or

nonspecific categories. Extensive use of the classification

system was reflected in the overall percentage and in the

individual therapists’ use of the system. Classification of

derangement was by far the commonest classification made.

The data were collected from 57 participants in primary

care clinics and hospitals from 18 countries, ensuring

widespread and varied collection sites. There was a good

participant response and data gathered from 600 patients.

Patient data were collected at point of discharge rather than

at initial evaluation as symptom responses; therefore,

mechanical syndrome classification, if uncertain, initially

can become clear with further testing.

A classification

system has value in deciding management at initial assess-

ment, and this is the purpose of the McKenzie classification

system. However, as the initial classification is provisional

and is confirmed on subsequent visits, data were collected

retrospectively. Participants were all highly trained and

experienced in mechanical diagnosis and therapy with the

intention of ensuring the highest level of recognition of

mechanical syndromes. This level of experience of therapist

has been shown to have good reliability in classifying and

identifying key aspects of the mechanical syndromes in

patients with back

There are, however, several limitations to the survey.

Although therapists gathered data on the demographics of

the patients, these were not linked to individual patient

classifications. It is not possible, therefore, to match any

particular patient characteristics, such as age, duration of

symptoms, or sex, with particular mechanical syndromes.

Although response rates were good for this kind of survey,

there were still a number of nonresponders.

Data were gathered retrospectively at the time of dis-

charge of patients. Thus, only patients who had completed

treatment were included, which may be a source of bias.

However, details were recorded on consecutively discharged

patients, which included 101 patients who had not received

mechanical classification. So, not all discharged patients

were those who were assumed to have responded well.

The level of experience of the participating therapists

means that a direct comparison cannot be made with those

who are less familiar or experienced with the McKenzie

classification system. Years of training, experience, and

everyday use of a classification system are bound to

facilitate recognition of the classification items, a skill not

available to those less trained and experienced. Furthermore,

it should be noted that previous reliability studies relate to

the original description of the McKenzie classification

system,

whereas this survey used the revised system.

However, the revised system provides clear operational

definitions for the mechanical syndromes that make

interpretation of the system easier.

As specialist clinicians with a teaching role at post-

graduate level, it might be questioned if the patient

population is representative of normal practice. However,

although some therapists had a specialized clinic with

predominantly referrals from specialists, this was not the

case in every instance. The therapists reported that on

average, approximately 67% of their patients were self-

referred or referred from their GP, patients had a range of

symptom duration, and most were working. The practice

setting of the therapists was principally in private practice.

In the only directly comparable study of 522 patients

with back pain, 307 (58%) were classified in one of

McKenzie mechanical syndromes after one visit.

Those

not classified in one of the mechanical syndromes had

experienced back pain for a significantly longer period.

Various significant differences were found between the

classified and unclassified group in pain and disability

scores, time off work, and general health scores. Similar

data were not gathered in the present study; hence,

comparisons cannot be made. The study has several

limitations: it is only published as an abstract; the clinician

involved had not completed the full McKenzie educational

program (only parts A-D), and his experience with the

system was unknown; and diagnosis was made on day 1

when, in fact, several sessions may be necessary to generate

a clear symptom response, especially in patients with chronic

pain. These factors may account for the lower prevalence of

mechanical syndromes.

Numerous classification systems for back problems

exist.

Some of these are in various stages of

development, with reliability and validation studies available,

whereas others are simply described. Sikorski

reported on

142 patients with back pain seen by one therapist, of which

82% were classified into 1 of 3 categories depending on

symptom response. No reliability or other studies appear to

have been performed on this classification system. Wilson

et al

reported on the reliability of a spinal classification

640

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

May

October 2006

McKenzie Classification

system, which also used symptom response and symptom

location to categorize patients. Two hundred four patients

were classified according to the system; however, it

was unclear if patients were consecutive, and they were

mostly acute. The Quebec Task Force classification system

was designed so that it would be inclusive of all patients

with back pain, but some of its categories involve response

to imaging studies and treatment. Some studies have

evaluated the first 4 Quebec Task Force categories only,

which relate to area of symptoms, and not surprisingly, all

104 patients could be classified.

This classification

system does not direct management as the McKenzie system

does. Other recent classification systems

do not as yet

appear to have had validation studies, although reliability

studies have been conducted,

and one of these gives

positive agreements about classification on a consecutive

sample of patients.

This system is, in part, derived from

the McKenzie classification system, but only 45% of

their patients were classified in directly comparable mechan-

ical syndromes; however, it involves far more classifica-

tion categories.

The present study shows the wide applicability of the

McKenzie classification system to a varied patient popula-

tion among specialist McKenzie practitioners. This suggests

the system has clinical use but needs further exploration

among other patient and therapist populations. Some

preliminary studies suggest that there are effective and

ineffective methods to manage patients who are given

mechanical classifications and then randomized to different

treatments.

Further work needs to be done to substan-

tiate the classification-management link, as the ultimate

justification for any classification system must be the proof

that it improves patient management.

C

ONCLUSION

In a consecutive discharged patient population, McKenzie

mechanical syndromes were used to classify 83% of 607

spinal patients. These decisions were made by highly trained

and experienced McKenzie therapists over a 1-month period.

Although this shows common usage of the mechanical

syndromes by therapists who are expert in the McKenzie

method, external validity is limited by the specialized nature

of the participating therapists.

R

EFERENCES

1. Clinical Standards Advisory Group. Report on back pain.

London7 Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1994.

2. Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al. Acute low back problems

in adults. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14. AHCPR

Publication No. 95-0642. Rockville (Md)7 Agency for Health

Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services; 1994 [Available

from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=

hstat6.chapter.25870].

3. Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of LBP. Reaching a specific

diagnosis is often impossible. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:

1444-8.

4. Bogduk N, Derby R, Aprill C, Lord S, Schwarzer A.

Precision diagnosis of spinal pain. In: Campbell JN, editor.

Pain 1996—an updated review; refresher course syllabus.

Seattle7 International Association for the Study of Pain Press;

1996. p. 313-22.

5. Laslett M, Young SB, Aprill CN, McDonald B. Diagnosing

painful sacroiliac joints: a validity study of the McKenzie

evaluation and sacroiliac provocation tests. Aust J Physiother

2003;49:89-97.

6. Young S, Aprill C, Laslett M. Correlation of clinical

examination characteristics with three sources of low back

pain. Spine J 2003;19:460-5.

7. Leboeuf-Yde C, Lauritsen JM, Lauritzen T. What has the

search for causes of low back pain largely been nonconclusive.

Spine 1997;22:877-81.

8. McCarthy CJ, Arnall FA, Strimpakos N, Freemont A,

Oldham JA. The biopsychosocial classification of non-

specific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther

Rev 2004;9:17-30.

9. Fairbank JCT, Pynsent PB. Syndromes of back pain and their

classification. In: Jayson MIV, editor. The lumbar spine and

back pain. 4th ed. Edinburgh7 Churchill Livingstone; 1992.

10. Riddle DL. Classification and low back pain: a review of the

literature and critical analysis of selected syndromes. Phys

Ther 1998;78:708-37.

11. Petersen T, Thorsen H, Manniche C, Ekdahl C. Classification

of non-specific low back pain: a review of the literature on

classification systems relevant to physiotherapy. Phys Ther

Rev 1999;4:265-81.

12. Spitzer WO, LeBlanc FE, Dupuis M, et al. Scientific approach

to the activity assessment and management of activity-related

spinal disorders. Spine 1987;12:S1-S55.

13. Delitto A, Erhard RE, Bowling RW. A treatment-based

classification approach to low back syndrome: identifying

and staging patients for conservative treatment. Phys Ther

1995;75:470-89.

14. Long A, Donelson R, Fung A. Does it matter which exercise?

A multi-centred RCT of low back pain subgroups. Spine

2004;29:2592-602.

15. Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. A systematic review of

efficacy of McKenzie therapy for spinal pain. Aust J

Physiother 2004;50:209-16.

16. McKenzie RA. The lumbar spine. Mechanical diagnosis and

therapy. Waikanae (New Zealand)7 Spinal Publications; 1981.

17. McKenzie RA. The cervical and thoracic spine. Mechanical

diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae (New Zealand)7 Spinal

Publications; 1990.

18. McKenzie R, May S. The human extremities mechanical diag-

nosis and therapy. Waikanae (New Zealand)7 Spinal Publica-

tions; 2000.

19. McKenzie R, May S. The lumbar spine mechanical diagnosis

and therapy. Waikanae (New Zealand)7 Spinal Publications;

2003.

20. Battie MC, Cherkin DC, Dunn R, Ciol MA, Wheeler KJ.

Managing low back pain: attitudes and treatment preferences

of physical therapists. Phys Ther 1994;74:219-26.

21. Foster NE, Thompson KA, Baxter GD, Allen JM. Management

of nonspecific low back pain by physiotherapists in Britain and

Ireland. A descriptive questionnaire of current clinical practice.

Spine 1999;24:1332-42.

22. Gracey JH, McDonough SM, Baxter GD. Physiotherapy

management of low back pain. A survey of current practice

in Northern Ireland. Spine 2002;27:406-11.

May

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

McKenzie Classification

Volume 29, Number 8

641

23. Fritz JM, Delitto A, Vignovic M, Busse RG. Interrater

reliability of judgements of the centralisation phenomenon

and status change during movement testing in patients with

low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:57-61.

24. Kilby J, Stigant M, Roberts A. The reliability of back pain

assessment by physiotherapists, using a dMcKenzie algorithmT.

Physiotherapy 1990;76:579-83.

25. Kilpikoski S, Airaksinen O, Kankaanpaa M, Leminen P,

Videman T, Alen M. Interexaminer reliability of low back

pain assessment using the McKenzie method. Spine 2002;

27:E207-14.

26. Razmjou H, Kramer JF, Yamada R. Intertester reliability of the

McKenzie evaluation in assessing patients with mechanical

low-back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2000;30:368-89.

27. Werneke M, Hart DL, Cook D. A descriptive study of the

centralisation phenomenon. A prospective analysis. Spine

1999;24:676-83.

28. Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. Reliability of McKenzie

classification of patients with cervical or lumbar pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005;28:122-7.

29. Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. Reliability of the McKenzie

spinal pain classification using patient assessment forms.

Physiotherapy 2004;90:114-9.

30. Dionne C, Bybee R. Interrater reliability of McKenzie assess-

ment of patients with cervical pain. Proceedings of the

McKenzie Institute 8th International Conference; 2003 Sept;

Rome. Waikanae (New Zealand)7 Spinal Publications; 2003.

31. Riddle DL, Rothstein JM. Intertester reliability of McKenzie’s

classification of the type of the syndrome types present in

patients with low back pain. Spine 1993;18:1333-44.

32. Aina A, May S, Clare H. The centralization phenomenon

of spinal symptoms—a systematic review. Man Ther 2004;9:

134-43.

33. Pinnington MA, Miller JS, Rose MJ, Stanley IM, Rose GM.

New episodes of back pain: how many patients can be

classified into McKenzie syndromes? J Bone Joint Surg

2000;82B(Supp III):211-2.

34. Werneke M, Hart DL. Discriminant validity and relative

precision for classifying patients with non-specific neck and

back pain by anatomic pain patterns. Spine 2003;28:161-6.

35. Binkley J, Finch E, Hall J, Black T, Gowland C. Diagnostic

classification of patients with low back pain: report on a survey

of physical therapy experts. Phys Ther 1993;73:138-55.

36. Sikorski JM. A rationalised approach to physiotherapy for low-

back pain. Spine 1985;10:571-9.

37. Wilson L, Hall H, McIntosh G, Melles T. Intertester reliabi-

lity of a low back pain classification system. Spine 1999;24:

248-54.

38. Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ. Movement system

impairment-based categories for low back pain: stage 1

validation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2003;33:126-42.

39. Petersen T, Laslett M, Thorsen H, et al. Diagnostic classi-

fication of non-specific low back pain. A new system

integrating patho-anatomical and clinical categories. Physi-

other Theory Pract 2003;19:213-37.

40. Loisel P, Vachon B, Lemaire J, et al. Discriminative and

predictive validity assessment of the Quebec Task Force

classification. Spine 2002;27:851-7.

41. Petersen T, Olsen S, Laslett M, et al. Inter-tester reliability of a

new diagnostic classification system for patients with non-

specific low back pain. Aust J Physiother 2004;50:85-91.

42. Van Dillen LR, Sahrmann SA, Norton BJ, et al. Reliability of

physical examination items used for classification of patients

with low back pain. Phys Ther 1998;78:979-88.

43. Fritz JM, George S. The use of a classification approach to

identify subgroups of patients with acute low back pain. Spine

2000;25:106-14.

44. Heiss DG, Fitch DS, Fritz JM, et al. The interrater reliability

among physical therapists newly trained in a classification

system for acute low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther

2004;34:430-9.

45. Schenk RJ, Jozefczyk C, Kopf A. A randomised trial

comparing interventions in patients with lumbar posterior

derangement. J Man Manip Ther 2003;11:95-1102.

642

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

May

October 2006

McKenzie Classification

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

więcej podobnych podstron