225

Eating Disorders, 17:225–241, 2009

Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 1064-0266 print/1532-530X online

DOI: 10.1080/10640260902848576

UEDI

1064-0266

1532-530X

Eating Disorders, Vol. 17, No. 3, March 2009: pp. 1–31

Eating Disorders

Differential Treatment Response for Eating

Disordered Patients With and Without

a Comorbid Borderline Personality

Diagnosis Using a Dialectical Behavior

Therapy (DBT)-Informed Approach

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

DENISE D. BEN-PORATH

Department of Psychology, John Carroll University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

LUCENE WISNIEWSKI and MARK WARREN

Cleveland Center for Eating Disorders, Beachwood, Ohio, USA

Studies have reported conflicting findings regarding the impact on

treatment for eating disorder patients comorbidly diagnosed with

borderline personality disorder. The current investigation sought

to investigate whether individuals diagnosed with an eating disor-

der vs. those comorbidly diagnosed with an eating disorder and

borderline personality disorder differ on measures of eating disor-

ders symptoms and/or general distress over the course of treatment.

In light of the success of DBT in treating individuals diagnosed

with borderline personality disorder, a group known to have con-

siderable difficulties in regulating affect, the current study also

sought to examine whether these two groups would differ on

expectancies to regulate affect over the course of DBT-informed

treatment. Results indicated that while a comorbid diagnosis of

borderline personality disorder did not impact eating disorder

treatment outcomes, those comorbidly diagnosed did present over-

all with higher levels of general distress and psychological distur-

bance. With respect to affect regulation, results indicated that at

the beginning of treatment, eating disordered individuals who

carried a comorbid diagnosis of BPD were significantly less able to

This project was funded by a research fellowship from John Carroll University.

The authors would like to thank the clients and their therapists for participation in this study.

Address correspondence to Denise D. Ben-Porath, Department of Psychology, John

Carroll University, 20700 North Park Blvd., University Heights, OH 44118. E-mail: dbenporath@

jcu.edu

226

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

regulate affect than patients without a comorbid borderline diag-

nosis. However, at the end of treatment there was no statistically

significant difference between the two groups. The role of affect

regulation in treating eating disordered individuals with a comor-

bid borderline personality disorder diagnosis is discussed.

Studies investigating the prevalence of borderline personality disorder

(BPD) in women being treated for an eating disorder (ED) have produced

varying estimates ranging from as little as 2% to as high as 44% (Gwirtsman,

Roy-Byrne, Yager, & Gerner, 1983; Levin & Hyler, 1986; Pope, Frankenburg,

Hudson, Jonas, & Yurgelun-Todd, 1987; Wonderlich & Mitchell, 1997),

While estimates of prevalence rates vary, most clinicians agree that ED

patients who present with comorbid BPD (ED-BPD) are one of the most

challenging subtypes of ED individuals to treat (Johnson, Tobin, & Enright,

1989). Although the difficulties in treating those with an ED and a border-

line diagnosis are well documented (Fahy, Eisler, & Rusell, 1993; Herzog,

Keller, Lavori, Kenny, & Sacks, 1992; Johnson, Tobin, & Dennis, 1989), only

a handful of studies have specifically examined BPD comorbidity and its

impact on the course of treatment for those with eating disorders.

Johnson, Tobin and Dennis (1990) examined treatment outcomes in ED

patients with and without comorbid borderline personality 1 year after treat-

ment completion. While both groups presented initially with high levels of

ED symptoms at the initial assessment, approximately 90% of ED patients

achieved a significant reduction in ED symptoms whereas only 58% of those

diagnosed with ED-BPD achieved a significant reduction in ED symptoms.

Johnson et al. (1990) also found that ED patients with comorbid BPD pre-

sented with a more severe clinical picture at the beginning of treatment as

measured by the BDI and the SCL-90-R. While both groups reduced their

psychiatric symptomatology at similar rates over the course of treatment,

scores for the borderline patients remained at clinically significant levels

whereas the non-BPD group was largely asymptomatic.

While Steinberg, Tobin, and Johnson (1990) found that those with a

comorbid BPD diagnosis enter treatment with comparable symptom severity

on ED measures, other authors have found that ED individuals with comor-

bid borderline pathology enter treatment with a more severe clinical pic-

ture, both in terms of eating pathology and general distress. For example,

Wonderlich, Fullerton, Swift, and Kelin (1994) found that individuals diag-

nosed with ED-BPD reported a greater number of ED symptoms and higher

levels of general distress at intake. Although groups did not differ in the

amount of symptomatic change over time, symptoms in the individuals

comorbidly diagnosed remained more severe throughout treatment. Similar

to these previous findings, Zeeck et al. (2007) found that ED-BPD patients

as compared to ED-only patients reported more ED pathology as measured

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

227

by the EDI-2 and more general psychiatric symptomatology at the begin-

ning of treatment. Neither group differed in the amount of symptomatic

change on ED pathology, although scores on the EDI-2 remained consis-

tently more severe in the BPD group over the course of treatment. A similar

pattern was found on the SCL-90-R with one exception. There was a signifi-

cant interaction between time and diagnosis on the anxiety subscale of the

SCL-90-R. ED-BPD individuals had higher levels of anxiety in comparison to

the ED-only group at the beginning of treatment. However, at the end of

treatment no differences emerged.

What impact BPD has on the course of treatment for those diagnosed

with an ED remains unclear. In spite of these conflicting findings, most

researchers agree that those with BPD present with a more complicated

clinical picture, and thus, often require different levels and types of inter-

vention. Sansone, Fine and Sansone (1994) report that effective treatment

for individuals diagnosed with ED-BPD must entail an integrated and

comprehensive approach that extends to the therapeutic milieu and incor-

porates individual/group psychotherapy and consultation. Zeeck and col-

leagues (2007) suggest that borderline patients being treated for an ED

require therapies that focus not only on the ED symptoms, but also on

deficits in the areas of interpersonal skills, affect regulation, and impulse

control.

DIALECTICAL BEHAVIOR THERAPY APPLIED

TO EATING DISORDERS

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), is a multi-disciplinary treatment

approach that uses multiple treatment modes (e.g., individual therapy,

group skills training, telephone coaching, team consultation) to address def-

icits in interpersonal relationships, affect regulation and impulse control.

Therefore, this treatment holds considerable promise for ED individuals

diagnosed with comorbid BPD. Johnson et al. (1990) have speculated that

the one-third of patients who typically do not respond to treatment are

likely ED individuals who are also comorbidly diagnosed with BPD. This

lack of treatment response is thought, in part, to be due to the failure of

traditional cognitive behavioral interventions in addressing the affect dys-

regulation and impulsivity that accompanies ED-BPD clients.

In an effort to explore the treatment effectiveness of DBT with comor-

bidly diagnosed ED clients, Palmer and colleagues (2003), in an uncon-

trolled clinical trial, applied the DBT treatment model to seven individuals

diagnosed with an ED and BPD. Results indicated that there was a reduc-

tion in self harm as well as ED behavior. Given the treatment focus of DBT

in the area of affect regulation and reduction in self injury, this treatment

would seem highly appropriate for this comorbidly diagnosed group.

228

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

Moreover, several researchers have stated that DBT may also be indi-

cated in the treatment of those with an ED who present without Axis II

pathology. Some theorists have argued that ED symptoms represent a mal-

adaptive method to regulate negative affect (Heatherton & Baumeister,

1991; Safer, Telch, & Agras, 2001; Telch, Agras, & Linehan, 1990, 2001). In

fact, several studies have demonstrated that negative mood states are

reduced in women after a binge eating episode (see Polivy & Herman, 1993

for a review of these studies).

To date, a handful of studies have investigated the effectiveness of DBT

and explored the role of affect regulation in treatment outcomes in those with

an ED. Telch, Agras, and Linehan (1999) conducted an uncontrolled clinical

trial on 11 women who underwent group DBT skills treatment modified for

their BED. At the end of treatment, 82% reported being abstinent from binge

eating. Furthermore, patients’ scores on the NMR scale significantly improved,

indicating that these women held stronger self expectancies for regulation of

negative mood states post-treatment as compared to pre treatment.

Following up on these findings, Telch, Agras, and Linehan (2001) con-

ducted a clinically controlled trial in which 44 women diagnosed with BED

were randomly assigned to group DBT skills modified for BED or a wait-list

control group. Results indicated that 89% of the participants in the DBT

skills group condition were abstinent from binge eating as compared with

only 12.5% in the control condition. However, no differences emerged

between the two groups on the NMR Scale, suggesting that the wait list

control did not differ significantly from the DBT group in expectancies to

regulate negative mood states.

More recently, Safer, Telch, and Agras (2001) have applied DBT treat-

ment to individuals diagnosed with binge/purge behaviors. At the end of

treatment, 28.6% in the DBT condition were abstinent from binge eating/

purging behaviors as compared with no participants in the wait-list control

condition. With respect to NMR scores, at the beginning of therapy ED indi-

viduals in the DBT condition reported significantly less expectancy to regu-

late affect as compared to ED individuals in the wait list condition.

However, at the end of treatment, there was no difference between the two

groups (Safer, Telch, & Agras, 2001).

To date, several studies have investigated the impact of a comorbid BPD

diagnosis in the treatment outcome of those diagnosed with an ED. These

studies have produced conflicting results with some suggesting that BPD has

no impact on ED symptoms (Steinberg et al., 1990) whereas other authors

have found that ED-BPD individuals enter treatment with a more severe clin-

ical picture, both in terms of eating pathology and general distress (Wonder-

lich, et al., 1994; Zeeck et al., 2007). Thus, the first goal of this study was to

investigate whether individuals diagnosed with an ED vs. those comorbidly

diagnosed with an ED and BPD differ on measures of eating disorders symp-

toms and/or general distress over the course of treatment.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

229

A second, but equally important goal of this study was to explore the

role of affect regulation in DBT-informed treatment in individuals diagnosed

with ED vs. those diagnosed with ED-BPD. Because the previous literature

suggests that ED-BPD individuals enter treatment with higher levels of gen-

eral distress, it was predicted that those ED individuals comorbidly diag-

nosed with BPD would report lower expectancies to regulate negative affect

pre treatment as compared to their nonborderline peers. However, because

difficulties in affect regulation are central to BPD and DBT treatment specif-

ically targets affect dysregulation (Linehan, 1993), it was hypothesized that

no difference would be present in expectancies to regulate affect between

these two groups post-treatment.

METHOD

Participants

Participants in the current study were recruited over an 18-month period.

Participants were excluded from the study if they were under 18 years of

age, had been treated previously at the facility, were actively homicidal/

suicidal or met criteria for substance abuse/dependence. Additionally, indi-

viduals meeting criteria for BED did not meet the admissions criteria for par-

tial hospitalization. Therefore, they were not eligible to participate in the

current study, but rather were referred to a once-weekly outpatient group.

The initial sample consisted of 71 participants, all of whom were admit-

ted to the outpatient partial hospitalization program specializing in the treat-

ment of eating disorders. Of those, 21% (5 with a borderline diagnosis and

10 without a borderline diagnosis) dropped out of treatment prematurely

due to treatment non-compliance and an additional 16 (23%) did not have

discharge data available due to administrative error. Several one-way

ANOVAs were conducted comparing these three groups (e.g., those who

had discharge data available vs. those who dropped out of treatment pre-

maturely and did not have discharge data available, vs. those who were not

given discharge assessments due to administrative error) on the following

variables of interest: pre-treatment body mass index, age, Beck Depression

Inventory-2 (BDI-2), Beck Anxiety Inventory-2 (BAI-2), and the Eating

Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q). No statistically significant dif-

ferences were found on pre-treatment measures or the variables of age and

body mass index between the three groups.

The remaining sample in the current study consisted of 40 outpa-

tients (one man and 39 women) who participated in a 30 hour per week

partial hospitalization program designed specifically to treat eating disor-

ders. The mean age of the sample was 26.03 (SD = 7.92) years. The mean

body mass index for the sample at the time of admission was 21.96 (SD =

4.77). The average length of stay in the program was 73.16 (SD = 40.88) days.

230

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

Sixteen (40%) individuals met DSM-IV-TR criteria for an ED and BPD. The

ED diagnosis was determined by a semi-structured interview by a

licensed clinician. The borderline diagnosis was determined through a

combination of the PDQ-4 and clinician confirmation of a borderline

diagnosis post discharge. Based upon these criteria, 24 (60%) individuals

met DSM-IV-R diagnostic criteria for an ED, but not BPD. Patients who

were actively psychotic, suicidal, or substance dependent were excluded

from the partial hospitalization treatment program. Table 1 presents addi-

tional demographic information for this sample, including additional Axis

I diagnoses.

Program Description

Individuals seeking treatment for an ED at this hospital clinic underwent a

2-hour assessment by a licensed mental health worker to determine

whether they met criteria for an ED according to DSM-IV-TR, and to deter-

mine if their symptoms warranted a partial hospitalization level of care (e.g.,

30 hours of treatment per week). Consistent with the practice guidelines put

forth by the American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Eating Disor-

ders (2006), admission to a partial hospitalization program (PHP) requires

that a patient be greater than 75% of their ideal body weight, be medically

stable, exhibit partial motivation to recover, require structured treatment,

and have limited social support.

Once clients were evaluated and determined to meet American Psychi-

atric Association (APA) criteria for a partial hospitalization level of care, they

were oriented to a DBT-informed treatment model adapted to eating disor-

ders (see Wisniewski & Kelly, 2003). All patients participated in twice

weekly DBT group skills training during which mindfulness, emotion regu-

lation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness skills were taught

and practiced. Additional groups which incorporated DBT concepts

included a weekly group that focused on motivation and commitment, a

goal setting group, and a behavior chain analysis group. In the behavior

chain analysis group, clients provided a detailed written account of the

events, emotions, cognitions, and physical sensations leading up to, during,

and after ED behavior and/or life threatening behaviors. In addition to

behavior chain analysis, patients completed daily diary cards that were

modified to target ED behaviors as well as self injurious/suicidal behaviors.

Clients also participated in a “DBT in-action” group (a group in which par-

ticipants practiced DBT skills in order to promote generalization outside of

treatment) as well as a weekly yoga group which incorporated elements of

mindfulness to movement. The nutrition module taught patients about

healthy eating and meal planning. Lastly, in vivo exposure to food in which

clients ate healthy meals together (e.g., exposure therapy) was also part of

the DBT-informed program.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

231

Consistent with the approach offered in standard DBT, ED clients were

offered after-hours telephone consultation to promote skills generalization

and to reduce self injurious and suicidal behaviors. However, clients were

also encouraged to call their therapist to assist in resisting urges to engage

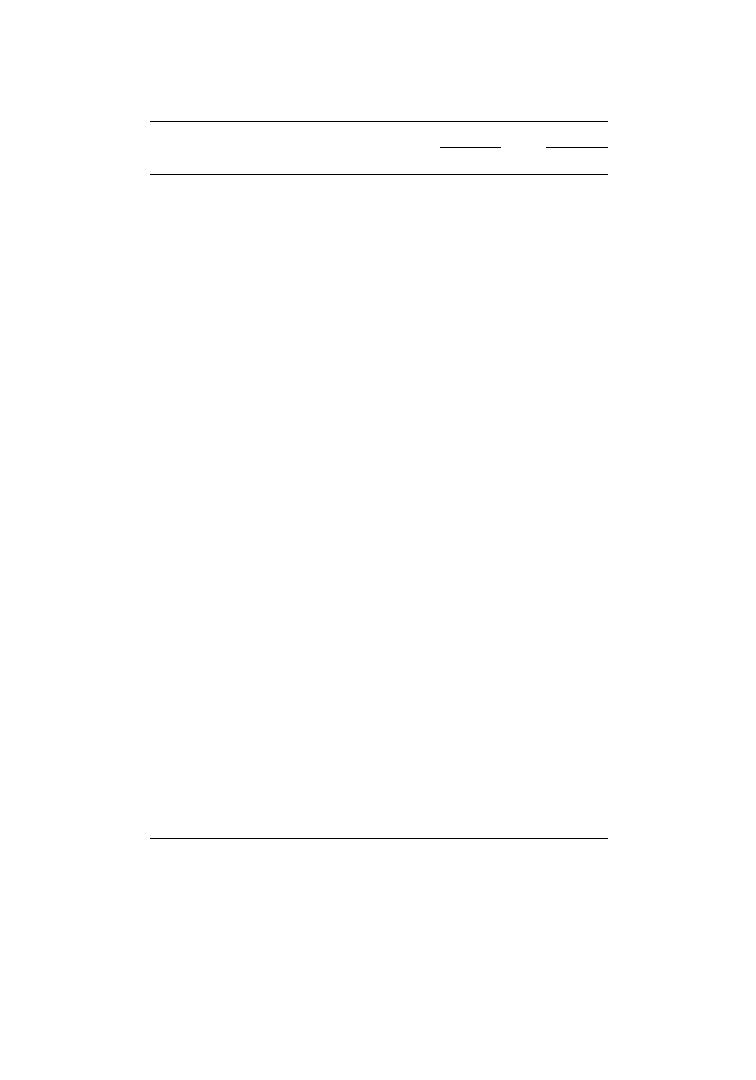

TABLE 1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants by Diagnosis

ED-BPD

ED

Characteristic

n (%)

n (%)

Gender

Female

15 (94%)

24 (0%)

Male

1 (6.3%)

0 (100%)

Marital Status

Never Married

12 (86%)

16 (66.7%)

Married

1 (7.1%)

5 (20.8%)

Divorced

1 (7.1%)

2 (8.3%)

Widowed

0 (0%)

1 (4.2%)

Race

Caucasian

14 (100%)

22 (91.7%)

Hispanic

0 (0%)

2 (8.3%)

Level of Education

Some Graduate Training

2 (14.3%)

2 (8.3%)

Some College Education

5 (35.7%)

10 (41.7%)

High School/GED

6 (50%)

12 (50%)

Current Employment

Employed Full Time

6 (42.9%)

6 (27.3%)

Employed Part Time

1 (7.1%)

4 (18.2%)

Unemployed

3 (21.4%)

4 (18.2%)

Disabled

4 (28.6%)

7 (31.8%)

Retired

0 (0%)

1 (4.5%)

Eating Disorder Diagnosis

Anorexia Nervosa

1 (7.1%)

6 (25%)

Bulimia Nervosa

9 (64.3%)

7 (29.2%)

Eating Disorder, NOS

4 (28.6%)

11 (45.8%)

Additional Axis I Diagnosis

Depression/Dysthymia

5 (55.5%)

12 (85.7%)

Anxiety

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

1 (11.1%)

1 (7.1%)

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

1 (11.1%)

1 (7.1%)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

Panic Disorder

1 (11.1%)

0 (0%)

Bipolar Disorder

1 (11.1%)

0 (0%)

Medications Prescribed

Anxiolytics

1 (8%)

0 (0%)

Antipsychotics

1 (8%)

3 (13%)

Mood stabilizers

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

Antidepressants

9 (69%)

10 (42%)

Note: Due to missing data, numbers may not total 40.

232

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

in ED behaviors (see Wisniewski & Ben-Porath, 2005 for a complete

description of the DBT telephone protocol adapted to ED patients). A team

of professionals (e.g., psychologist, psychiatrist, nutritionist, social worker,

and milieu therapists) comprised the DBT consultation team. The team met

on a weekly basis to consult on cases within a DBT framework.

Unlike standard DBT treatment, individual therapy was not offered.

Third party payers are often unwilling to reimburse for individual treatment

while a patient is in higher levels of care. In an effort to compensate for this

limitation, each patient in the treatment protocol was assigned to a therapist

who met with the patient at a minimum of once weekly for 30 minutes.

During these sessions, the diary cards and behavior chain analyses were

reviewed and therapy-interfering behaviors were addressed. The assigned

therapist also validated the clients’ responses and difficulties in treatment

while also assisting them in replacing maladaptive behaviors with more

skillful behaviors. Thus, the current program employed all four modes of

standard DBT treatment. However, the time allocated to each client for indi-

vidual therapy was reduced and components of the group material were

adapted for an ED population.

Measures

E

ATING

D

ISORDER

E

XAMINATION

-Q

UESTIONNAIRE

(EDE-Q)

The EDE-Q is a questionnaire that provides information about the fre-

quency of ED behaviors over a period of the last 28 days. Questions reflect

the DSM-IV criteria for eating disorders. The EDE-Q yields four subscales.

These include dietary restraint, eating concerns, weight concerns, and shape

concerns subscales. Subscale scores can range from 0 to 6 with higher

scores indicating greater ED disturbance. The EDE-global score consists of

the four subscales. The EDE-Q has been shown to have acceptable internal

consistency with Cronbach alphas ranging from 0.78 to 0.93. Test-retest reli-

ability of the EDE-Q subscales over a two-week period yielded Pearson r

coefficients ranging from 0.81 to 0.94 (Luce & Crowther, 1999).

N

EGATIVE

M

OOD

R

EGULATION

(NMR)

SCALE

Consistent with previous research in this area, the NMR Scale was used

(Safer et al., 2001; Telch et al., 1999, 2000). The NMR is a 30-item self-report

questionnaire that assesses an individual’s expectancy to successfully regu-

late negative mood states. This measure utilizes a 5-point Likert scale format

ranging from 30 to 150 with higher scores indicating a greater expectancy

that one can regulate negative mood. The NMR demonstrated adequate tem-

poral stability of 0.74 over a 3–4 week period, adequate discriminant validity

from other measures such as the BDI, and adequate internal consistency

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

233

with alphas ranging from 0.86 to 0.92 (Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990). The NMR

yields the following three scales: (1) NMR-General which measures an indi-

vidual’s general ability to regulate mood (e.g.,” I can find a way to relax”),

(2) NMR-Cognitive which measures an individual’s ability to regulate mood

via cognitive strategies (e.g., “Planning how I’ll deal with things will help.”),

and (3) NMR-Behavioral which measures an individual’s ability to regulate

mood via behavioral strategies (e.g., “Going out with friends will help.”).

T

HE

B

ECK

D

EPRESSION

I

NVENTORY

-2 (BDI-2)

Consistent with previous research in this area, the BDI-2 was used (Safer,

et al., 2001; Telch et al. 1999, 2000). The Beck Depression Inventory-2 is a

21-item scale self-report instrument used for measuring depressive symp-

toms corresponding to the criteria for major depressive disorder found in

DSM-IV (1994). Higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symp-

tomatology. The instrument has well documented reliability and validity.

The coefficient alpha of the BDI-II for an outpatient sample was 0.92 (Beck,

Steer, & Brown, 1996).

T

HE

B

ECK

A

NXIETY

I

NVENTORY

-2 (BAI-2)

Consistent with previous research in this area, the BAI-2 was used (Safer et al.,

2001; Telch et al., 1999, 2000). The Beck Anxiety Inventory-2 is a 21-item

scale that measures severity of anxiety, with higher scores indicating greater

anxiety. The instrument has well documented reliability with Cronbach

coefficient alpha in the range of 0.92. Test retest reliability with a one week

interval was 0.75 (Beck & Steer, 1990).

P

ERSONALITY

D

ISORDER

Q

UESTIONNAIRE

-4 (PDQ-4)

The PDQ-4 is a 100-item self report, true/false questionnaire that yields

diagnoses consistent with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for Axis II person-

ality disorders. The PDQ-4 was selected because of its adaptability to a

clinical setting and brevity (Sansone & Levitt, 2005). Test-retest reliability for

the PDQ-4 was adequate and compared favorably with the interrater reli-

ability of a DSM-III-oriented clinical interview and the Diagnostic Interview

for Borderline Patients (DIB) (Hyler, Skodol, Kellman, Oldham & Rosnick,

1990). Levin and Hyler (1986) achieved excellent agreement for their inter-

view diagnoses with kappa coefficients of 0.92 for BPD. Based upon the

recommendations by Sansone and Levitt (2005) only individuals whose bor-

derline diagnoses were confirmed post discharge by the treating clinician

and received a score indicative of borderline personality disorder were

included in the BPD category.

234

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

Procedure

Clients who met criteria for an ED and whose symptoms warranted the level

of care of partial hospitalization were included in the protocol. At the time

of admission and again at discharge, all participants completed the

measures above. In order to assess for borderline personality features, all

participants were administered the PDQ-4 at the time of admission.

RESULTS

A series of 2 (ED vs. ED-BPD)

× 2 (time of testing) mixed factor analyses of

variance (ANOVA) was conducted with diagnosis as a between factor and

time of testing as a within subjects factor. Scores on the NMR, BDI-II, BAI-II,

and the EDE-Q served as the dependent variables. Pre and post-treatment

means and standard deviations and significance levels for the ED and

ED-BPD groups are listed in Table 2.

Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire

In an effort to decrease the possibility of type 1 error, subscales for the EDE-Q

were not analyzed separately. Rather the composite scale, the EDE-global was

used. On the EDE-global scale, there was a significant main effect for time

[F (1, 37) = p = .001] with participants reporting a reduction in ED symp-

toms from Time 1 (M=, SD=) to Time 2 (M=, SD=). No significant main

effect for diagnosis or significant interaction between time and diagnosis was

found on the EDE global scale.

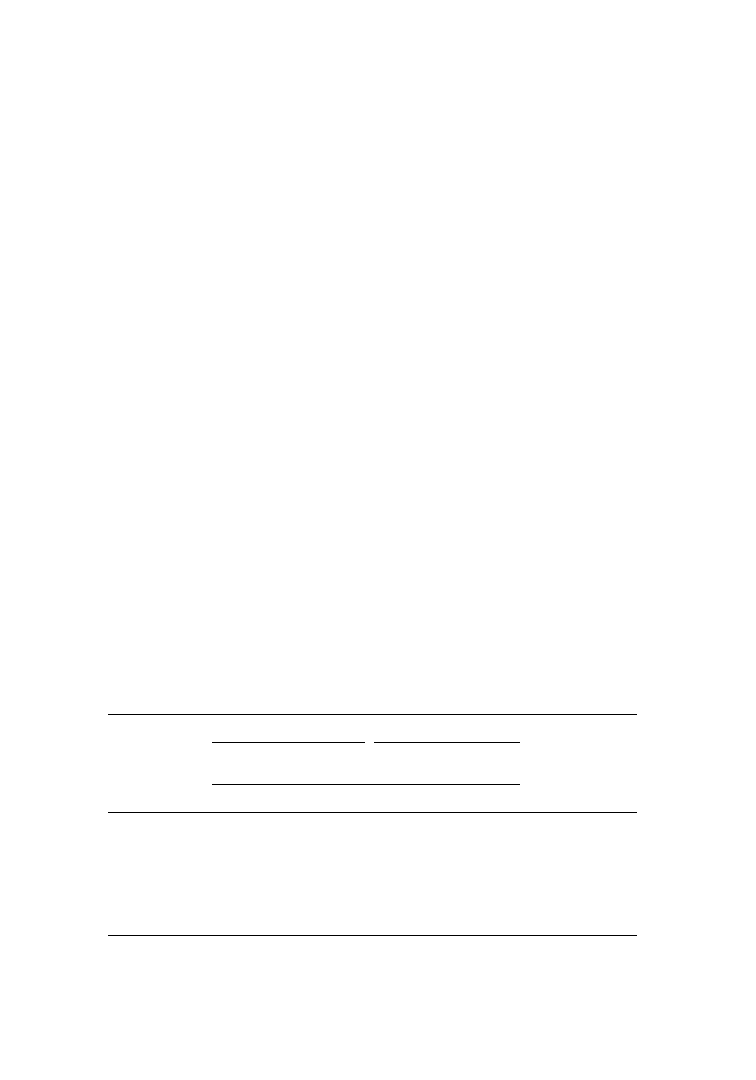

TABLE 2 Pre and Post-Treatment Means and Standard Deviations for Individuals Diagnosed

with an Eating Disorder and for Individuals Comorbidly Diagnosed with an Eating Disorder

and Borderline Personality Disorder

ED

ED-BPD

Pre-

treatment

Post-

treatment

Pre-

treatment

Post-

treatment

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

M (SD)

F

(df)

p

EDE-Q Global

Score

4.29 (.24)

3.35 (.293)

4.91 (.32)

3.66 (.39)

.314 1, 34 .579

BDI-2

24.71 (2.34) 13.80 (2.74)

37.39 (3.05) 21.15 (3.57)

1.17 1, 30 .287

BAI-2

18.09 (1.72) 13.49 (2.09)

25.79 (2.20) 15.93 (2.68)

2.17 1, 35 .15

NMR-General

31.65 (1.69) 32.45 (1.84)

23.08 (2.18) 32.79 (2.37)

7.98 1, 30 .008

NMR-Behavioral 34.35 (1.25) 35.23 (1.29)

26.00 (1.62) 32.92 (1.66) 10.56 1, 30 .003

NMR-Cognitive

31.75 (1.48) 32.85 (1.171) 22.00 (1.92) 32.67 (1.51) 11.21 1, 30 .002

Note. Due to missing data numbers may not total 40.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

235

Beck Depression and Beck Anxiety Inventories

On the BDI-II, there was a significant main effect for time with participants

reporting a reduction in depression from Time 1 (M = 28.41, SD = 12.60) to

Time 2 (M = 16.49, SD = 13.75) [F (1, 37) = 26.03, p = .001]. In addition,

there was a main effect for diagnosis [F (1, 37) = 8.09 p = .007] with ED

individuals with a comorbid borderline diagnosis (M = 28.25, SD = 2.62)

presenting overall with more depression as compared to those with only

an ED diagnosis (M = 18.67, SD = 2.12). No interaction between diagnosis

and time was found on the BDI-II. Results for the BAI-2 followed the same

pattern.

Negative Mood Regulation Scale

Because there is no composite score on the NMR, each scale was analyzed

separately. Thus, a bonferroni correction was done to control for multiple

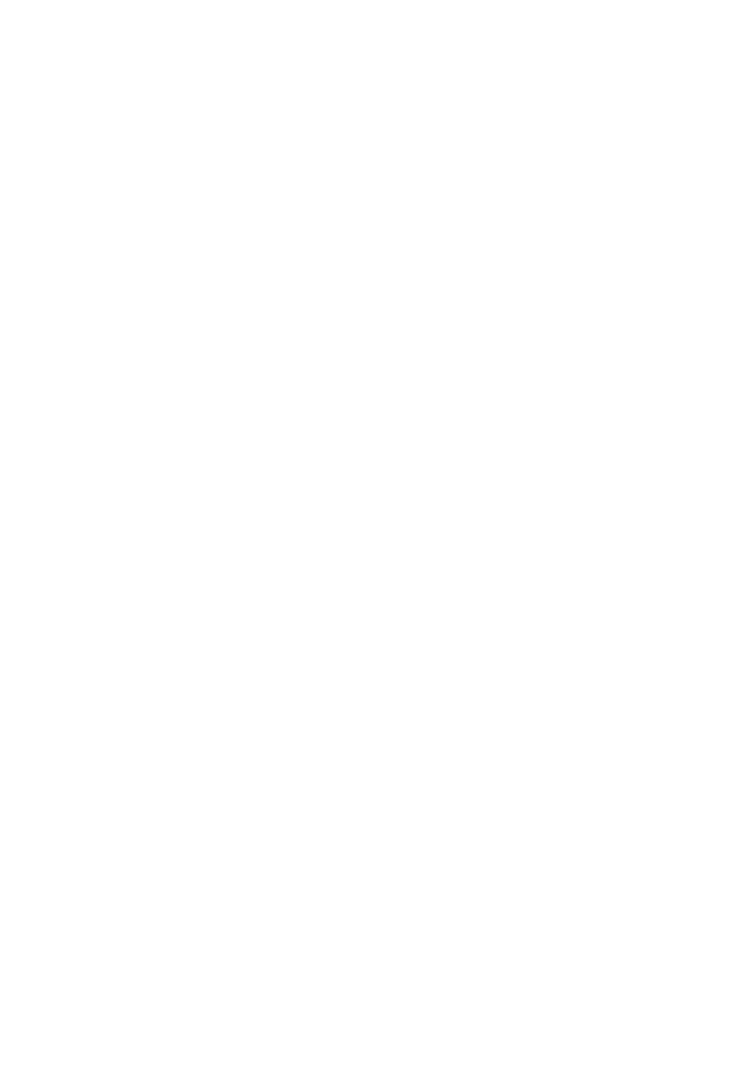

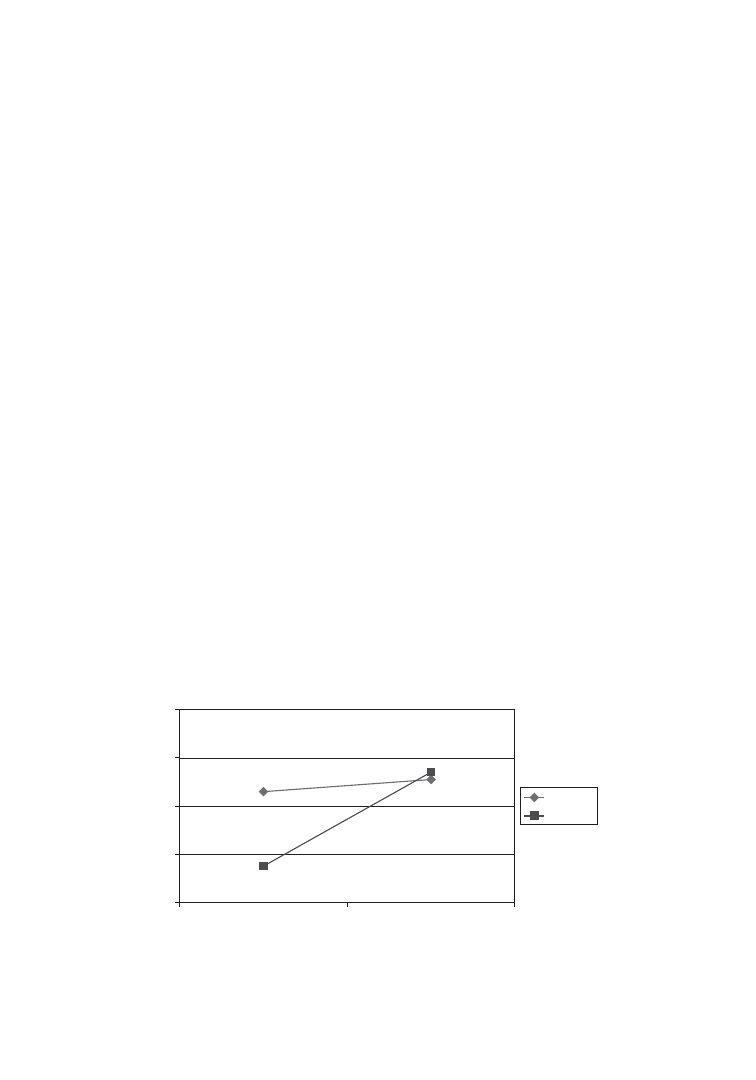

comparisons with alpha being set at 0.016 As can be seen in Figure 1, on

the NMR-general scale there was a significant main effect for time [F (1, 33) =

14.33, p = .001] but not diagnosis. This main effect must be interpreted in

light of a significant interaction [F (1, 33) = 8.43, p = .007]. At the beginning

of treatment ED individuals who carried a comorbid diagnosis of BPD

reported significantly less ability to regulate affect on the NMR-general

scale (M = 23.79, SD = 4.71) than patients without a comorbid borderline

diagnosis (M = 31.48, SD = 8.62). However, at the end of treatment there

was no difference between the ED-BPD (M = 33.54, SD = 6.91) and

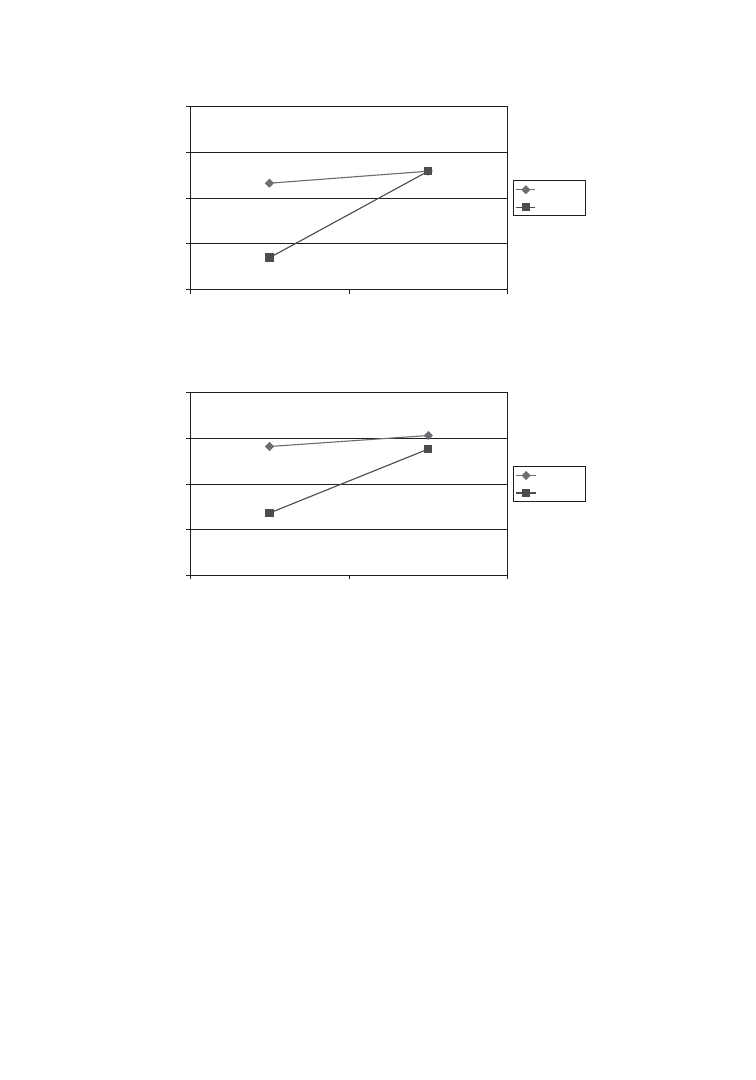

ED-only (M = 32.76, SD = 8.71) groups. As can be seen in Figures 2 and 3,

results for the NMR-cognitive and NMR-behavior scale followed the same

pattern.

FIGURE 1 NMR-General scores for ED and ED/BPD patients pre and post-treatment.

20

25

30

35

40

Time1

Time2

ED

ED/BPD

236

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

DISCUSSION

The first goal of this study was to attempt to resolve the contradictory find-

ings in the literature pertaining to the impact of a borderline diagnosis on

treatment outcomes for those with an ED. On the EDE-Q global subscale no

differences emerged between individuals diagnosed with ED vs. those diag-

nosed with ED-BPD over the course of treatment. While the ED-BPD group

was somewhat more symptomatic pre-treatment, these differences were not

significant and there were no differences post-treatment on the EDE-Q.

These findings are consistent with former studies that suggest that a comor-

bid diagnosis of BPD has minimal impact on ED outcomes (Wonderlich

et al., 1994; Zeeck et al., 2007).

With respect to general psychopathology, findings from the current study

were consistent with past research (Johnson et al., 1990; Wonderlich, et al., 1994;

FIGURE 2 NMR-Cognitive scores for ED and ED/BPD patients pre and post treatment.

20

25

30

35

40

Time1

Time2

ED

ED/BPD

FIGURE 3 NMR-Behavioral scores for ED and ED/BPD patients pre and post treatment.

20

25

30

35

40

Time1

Time2

ED

ED/BPD

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

237

Zeeck et al., 2007). In the current investigation, the ED-BPD group demon-

strated higher levels of depression and anxiety at the beginning and end of

treatment as compared to the ED group. However, both groups made simi-

lar reductions in depressive and anxious symptomatology over the course

of treatment, suggesting that individuals with ED-BPD enter and leave treat-

ment with higher levels of distress as compared to those diagnosed with ED

alone. In sum, these findings appear to support those described by Zeeck

et al. (2007), which state that individuals with ED-BPD do not appear to dif-

fer dramatically in ED symptomatology as compared to the their ED-only

peers. However, ED-BPD clients do appear to enter and leave treatment

with higher levels of general psychopathology as compared to their ED-only

counterparts.

The second major finding in the current investigation was that while

ED individuals comorbidly diagnosed with BPD reported lower expectan-

cies in their ability to regulate affect at the outset of treatment in comparison

to the ED-only patients, there were no statistically significant differences

between the two groups on the NMR scale at the end of treatment. These

findings are consistent with the Safer, Telch, and Agras (2001) study where

ED clients who were treated with DBT reported lower expectancies to regu-

late negative mood states on the NMR at the beginning of treatment in com-

parison to a wait list control group. However, the DBT group reported an

increase in expectancy to regulate affect such that no differences were

present post-treatment between the DBT group and the wait list control

group. Together these findings suggest that DBT treatment may play an

important role in increasing expectancies around affect regulation and may

be particularly helpful in increasing expectancies in affect regulation for

those ED patients who are comorbidly diagnosed with BPD.

While it could be argued that regression to the mean is responsible for

these findings it is unlikely. First, both the ED-BPD and the ED groups, began

with extremely low scores. For example, both groups had scores that were

more than five standard deviations from the mean of the normal sample.

However, at the end of DBT informed treatment, only the ED-BPD group

showed a statistically significant improvement in ability to regulate affect. The

score on the NMR scale for the ED group remained virtually unchanged. This

finding was consistent across all three scales of the NMR and was highly sig-

nificant even when the stringent criteria of a bonferroni correct was applied.

The findings from this study have several clinical implications. First,

with respect to affect regulation, the current investigation suggests that DBT

treatment may play a critical role in increasing ED-BPD clients expectancies

around their ability to regulate affect. While increasing and promoting cog-

nition about affect regulation does not guarantee a compatible behavioral

response, it is a necessary first step. If an individual does not have the belief

structure in place that they can indeed modulate their affective states the

behavioral response is unlikely to follow.

238

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

Furthermore, the ability to regulate affect plays a crucial role in learn-

ing skillful behavior in DBT treatment. Baddeley (2007) has contended that

the ability to regulate affect is essential and necessary in order to process

new information. He proposes that when an individuals’ affective state

becomes overly aroused, working memory is disrupted thereby reducing

processing capacity for the task at hand. In short, the ability to learn and

process new information is impaired when emotions are highly aroused.

While more recent models of treatment (e.g., Cooper, 2005; Fairburn,

Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991) have begun to

focus on the role that affect dysregulation may play in the development and

maintenance of eating disorders, it is equally important to recognize the role

that affect dysregulation may play in treatment failure. If individuals are

unable to regulate their affect sufficiently then it becomes more difficult for

them to attend to, process and subsequently utilize interventions taught in

treatment. For the ED-BPD client who exhibits considerable difficulties reg-

ulating affect, information taught in groups and individual therapy may be

impossible to process until their emotions are better managed. Because

DBT treatment has a primary focus on affect regulation, this treatment may

be particularly well suited for those with ED-BPD diagnoses.

An additional clinical implication to these findings is that they provide

direction for clinicians treating those with an ED-BPD diagnosis. It has long

been understood that those with ED-BPD present with a more complicated

clinical picture. These findings suggest that a large part of the complexity in

treating these individuals comes from higher disturbances in general psy-

chopathology (depression, anxiety, impulse control, and affect dysregula-

tion) rather than severity of ED symptoms. Therefore, treating clinicians

must be cognizant to treat symptoms of general distress in addition to the

ED pathology in those ED patients comorbidly diagnosed with BPD.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, because the

study was conducted in an applied clinical setting it was limited by practical

and ethical considerations. Although a control/wait list group would have

been desirable to determine whether changes in both groups were due to

treatment or other non-specific factors (e.g., passage of time, attention, etc.),

this was not possible due to the severity of the illness in these patients.

Recall that all patients admitted to the program met APA (2006) criteria for

partial hospitalization level of care. Thus, due to the severity of their symp-

toms and the need for immediate treatment, all patients were admitted to

the program within a week. An additional limitation of this study is the self

report measure of mood regulation. The NMR is a measure of an individ-

ual’s expectancy to regulate negative mood. While this measure was

employed so that comparisons across previous ED studies could be made

(Telch et al., 1999, 2000), it is important that studies investigate not only

perceived but actual ability to regulate affect in this population. Therefore,

future studies should employ physiological measures of affect regulation

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

239

and palm pilot methodology so that participants can rate mood states in the

moment. In addition, due to the time constraints involved in a clinical care

setting, diagnoses for borderline personality disorder were made from a self

report measures rather than a structured or semi-structured interview such

as the SCID. Finally, the current study utilized a modified DBT protocol for

eating disorders. Thus, comparisons between this study and the original

study conducted by Linehan et al. (1993) cannot be made.

In sum, the rates of comorbid BPD have been reported to be as high as

44% in those diagnosed with eating disorders (Gwirtsman et al., 1983). Thus,

there is a compelling need for therapies that address the treatment chal-

lenges associated with this subgroup. While these findings may not general-

ize to less severe ED populations, results from the current study hold out

promise by providing an effective treatment alternative for a subgroup of ED

patients that have traditionally been difficult to treat. Given the known diffi-

culties in affect regulation, increased levels of general psychiatric symptoms,

and poor therapy response in those diagnosed with ED-BPD, treatment

approaches such as DBT that address deficits in affect regulation, may be

critical to treatment success in ED clients comorbidly diagnosed with BPD.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (2006). Practice guideline for the treatment of

patients with eating disorders. APA Practice Guidelines, 3, 1–128.

Baddeley, A. (2007). Human memory: Theory and practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon

Beck, A. T. & Steer, R. A. (1990). Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory-II.

San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression

Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Catanzaro, S. J., & Mearns, J. (1990). Measuring generalized expectancies for nega-

tive mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications, Journal of

Personality Assessment, 54, 546–563.

Cooper, M. (2005). A developmental vulnerability-stress model of eating disorders:

A cognitive approach. In B. L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of

psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective (pp. 328–354). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fahy, T., Eisler, I., & Rusell, G. (1993). Personality and treatment response in

bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 765–770.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z. & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for

eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research

and Therapy, 41, 509–528.

Gwirtsman, H. E., Roy-Byrne, P., Yager, J., & Gerner, R. H. (1983). Neuroendocrine

abnormalities in bulimia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 559–563.

Heatherton, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-

awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 86–108.

240

D. D. Ben-Porath et al.

Herzog, D., Keller, M., Lavori, P., Kenny, G., & Sacks, N. (1992). The prevalence of

personality disorders in 210 women with eating disorders. Journal of Clinical

Psychiatry, 53, 147–152.

Hyler, S. E., Skodol, A .E., Kellman, H. D., Oldham, J. M., & Rosnick, L. (1990).

Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised: Comparison with

two structured interviews. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1043–1048.

Johnson, C., Tobin, D., & Dennis, A. B. (1990). Differences in treatment outcome

between borderline and nonborderline bulimics at one year follow-up.

International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 617–628.

Johnson, C., Tobin, D., & Enright, A. (1989). Prevalence and clinical characteristics

of borderline patients in eating-disordered population. Journal of Clinical

Psychiatry, 50, 9–15.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality

disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Levin, A. P., & Hyler, S. E. (1986). DSM-III personality diagnosis in bulimia.

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 27, 47–53.

Luce, K. H., & Crowther, J. H. (1999). The reliability of the Eating Disorder Exami-

nation-Self-Report Questionnaire Version (EDE-Q). International Journal of

Eating Disorders, 25, 349–351.

Palmer, R. L., Birchall, H., Damani, S., Gatward, N., McGrain, L., & Parker, L. (2003). A

dialectical behavior therapy program for people with an eating disorder and bor-

derline personality disorder—Description and outcome. International Journal of

Eating Disorders, 33, 281–286.

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (1993). Etiology of binge eating: Psychological mechanisms.

Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

Pope, H. G., Frankenburg, F. R., Hudson, J. I., Jonas, J. M., & Yurgelun-Todd, D.

(1987). Is bulimia associated with borderline personality disorder? A controlled

study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 48, 181–184.

Safer, D. L., Telch, C. F., & Agras, W. S. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy for

bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 632–634.

Sansone, R. A., Fine, M. A., & Sansone, L. A. (1994). An integrated psychotherapy

approach to the management of self-destructive behavior in eating disorder

patients with borderline personality disorder. Eating Disorders, 2, 251–260.

Sansone, R. A., & Levitt, J. L. (2005). Borderline personality and eating disorders.

Eating Disorders, 13, 71–83.

Steinberg, S., Tobin, D. L., & Johnson, C. (1990). The role of bulimic behaviors in affect

regulation: Different functions for different patient subgroups? International Journal

of Eating Disorders

, 9, 51–55.

Telch, C. F., Agras, W. S., & Linehan, M. M. (2000). Group dialectical behavior

therapy for binge-eating disorder: A preliminary, uncontrolled trial. Behavior

Therapy, 31, 569–582.

Telch, C. F., Agras, W. S., & Linehan, M. M. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy for

binge eating disorder. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 69,

1061–1065.

Wisniewski, L., & Ben-Porath, D. D. (2005). Telephone skill-coaching with eating

disordered clients: Clinical guidelines using a DBT framework. European

Eating Disorders Review, 13, 344–350.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders

241

Wisniewski, L., & Kelly, E. (2003). The application of dialectical behavior therapy to

the treatment of eating disorders. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10, 131–138.

Wonderlich, S. A., Fullerton, D., Swift, W. J., & Klein, M. H. (1994). Five-year out-

come from eating disorders: Relevance of personality disorders. International

Journal of Eating Disorders, 15, 233–243.

Wonderlich, S. A., & Mitchell, J. E. (1992). The comorbidity of personality disorders

in the eating disorders. In J. Yager (Ed.), Special problems in managing eating

disorders (pp. 51–86). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press.

Zeeck, A., Birindelli, E., Sandholz, A., Joos, A., Herzog, T., & Hartmann, A. (2007).

Symptom severity and treatment course of bulimic patients with and without

borderline personality disorder. European Eating Disorders Review, 15, 430–438.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Contrasting Clients in Dialectical Behavior Therapy for BPD Marie and Dean , Two Caseswith Diffe

Changes in Negative Affect Following Pain (vs Nonpainful) Stimulation in Individuals With and Withou

Making Contact with the Self Injurious Adolescent BPD, Gestalt Therapy and Dialectical Behavioral T

Stages of change in dialectical behaviour therapy for BPD

Brief Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Suicidal Behaviour and NSSI

Dialectical Behavior Therapy for BPD A Meta Analysis Using Mixed Effects Modeling

APA practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder

Nutrition?re for Patients With Chronic Renal?ilure

Drug and Clinical Treatments for Bipolar Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Patient Treatment Manual

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Patient Treatment Manual

Makówka, Agnieszka i inni Treatment of chronic hemodialysis patients with low dose fenofibrate effe

Differences between the gut microflora of children with autistic spectrum disorders and that of heal

A Proton MRSI Study of Brain N Acetylaspartate Level After 12 Weeks of Citalopram Treatment in Drug

Antisocial Personality Disorder A Practitioner s Guide to Comparative Treatments (Comparative Treatm

Inne zaburzenia odżywiania - Eating Disorder Not OtherWise Specified, PSYCHOLOGIA, PSYCHODIETETYKA

więcej podobnych podstron