1

Abstract

This paper focuses on the important status that is often

ascribed to metalworking and critically questions whether

this reflects a prehistoric reality. Following from this it also

questions the role of metalworking with regards to the pres-

ence of elites. It is argued that explaining metalworking as

a ‘ritual’ craft does not lead to a better understanding of the

organisation of metalworking in the Bronze Age. Finally a

suggestion is made for a different approach towards met-

alworking technology, in which the choices, made by the

prehistoric metalworker and recorded in the objects them-

selves, are the main focus.

Introduction

Since the Three-Age classification by Thomsen

bronze is set apart from stone and seen as one step

higher in an evolutionistic process of advancing so-

cieties and technology. Moreover, metalworking

technology is often regarded as an active agent that

dictated the course of social development (cf. Childe

1944 “archaeological ages as technological stages”).

More often than not, metalworking is put on a pedes-

tal and seen as the most important craft and driving

force of the Bronze Age. In other words, it is taken

out of its context and dealt with as a technology that

is self evidently more advanced and carries inherent

important status, advancement, confined knowledge,

rituals and the capability to change society. Follow-

ing, a close relationship between skilled metalwork-

ers and elites is often argued for.

1

My concern is that

this technological determinism is a too simplistic

explanation for the acceptance of bronze technol-

ogy and the effect of this technology on societies in

the Bronze Age. Technological determinism does not

take into account the social context in which metal-

working was taken up and metal objects found their

place. Only rarely is it questioned whether bronze re-

ally dominated the life of prehistoric people (Bradley

2007: 31; Kienlin 2007: 7) and in what way (Needham

1 E. g. Kristiansen 1987; Budd/Taylor 1995; Winghart 1998;

Vandkilde 2010.

2007). Recently, Bartelheim (2009) made an interest-

ing case that there are no pressing reasons to ascribe

an important economic role to metallurgy. Instead,

he advocates, agriculture appears to be the primary

mover and agricultural based prosperity stimulated

the development of metal production in Early Bronze

Age Central Europe. Hereby arguing against the idea

that metal “made the world go round” (cf. Pare 2000).

This example foremost reminds us of the possibility

that metallurgy may not necessarily be a condicio sine

qua non

for the changes that we witness during the

Early Bronze Age. Nonetheless, the focus of this pa-

per will not be on the debate whether there are other

forms of either wealth or stable finance that might

have brought elites to power (see Vandkilde 2010 for

a discussion). Instead, it critically assesses some of

the argumentation used to associate metalworking

with the ruling class.

Whilst the exclusiveness of each society is seen

as a decisive factor in the configuration of each so-

ciotechnical-system (Pfaffenberger 1992: 500) inter-

pretations on the organisation and importance of

metalworking still lean towards descriptive grand

narratives, generalizing the image for large parts of

Europe. Furthermore, the (unaware) transposition

of our present-day sensibilities of what constitutes

technology leads to a biased approach towards met-

alworking. Cartesian dichotomies such as ritual-pro-

fane, mind-body and commodity-gift can easily be

noticed in the interpretation of this prehistoric tech-

nology (WASP’s according to Martinón-Torres 2002:

36). They are more often than not used to advocate

the special status of metalworking. Interpretations

following from these dichotomies tie in with assump-

tions about the organisation of societies, power struc-

tures and hence the link between metalworking and

elites. I will critically assess some of the dichotomies

and see whether they are helpful in achieving a better

understanding of the role of metalworking in Bronze

Age societies. Furthermore, studies of the technology

itself appear to conceive a formal engagement with

the material, building on discursive knowledge only.

In this article it is advocated that the effects and im-

portance of metalworking can only be understood if

the technological process itself – as a whole – is stud-

ied, and not only its outcome (i. e. the objects).

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Metalworking

Technology

Maikel H. G. Kuijpers

2

Maikel H. G. Kuijpers

Scrutinizing the literature, two questions seem to

be of paramount importance, which tend to become

intertwined. Why was metalworking taken up? and What

was the role of metalworking in Bronze Age societies?

This

article will mainly focus on the latter. I will argue that

to answer this question we need to achieve a deeper

understanding of the organisation of the craft of met-

alworking, through its technology and its producers.

This may also indirectly help to explain the first ques-

tion.

How do we look at metalworking

technology?

“If craft objects are to be central in interpretations

of social and political relationships, an effort must be

made to determine who made them so as to under-

stand the perspective being communicated” (Costin

2001: 279). Nonetheless the ‘smith’ or metalworker

is still an elusive person. The importance of his/her

craft is mainly deduced from the numerous finished

objects found deposited all over Europe. Extrapolated

from their perceived socio-economic significance is

the idea that metalworking technology is a highly

specialised craft and hence that the people involved

must be skilful (ritual) specialists. However, as Dobres

(2010: 105) mentions, “the material remains of an-

cients life ways do not necessarily preserve in direct

proportion to their evolutionary or sociocultural sig-

nificance”. Hence, we must be aware of the potential

bias being created by the archaeological record, both

in terms of preservation but also the fact that most

of the metalwork found are intentionally deposited

objects. One could question whether these objects,

which have come to us through selective deposition,

are representative of the metalwork actually in use

and circulating in the Bronze Age, i. e. the life-assem-

blage

(Needham 2007). Furthermore, deposition does

not tell us how the object was produced, used, traded

or recycled. It tells us how the object was perceived

when it was deposited which does not need to be the

same when it was used. For ‘normally’ used tools and

objects, the most common end of their cultural biog-

raphy may have been re-melting (see Fontijn 2002:

247–249; Kuijpers 2008: 22–23). Hence, deposited ob-

jects do not give a representative image of what was

produced and used. Following from the ‘archaeologi-

cal record bias’ is the (unavoidable) preoccupation

of archaeologists with (the production of) special

classes of artefacts. The work of Helms (1993) is of-

ten cited to support interpretations on the ritual na-

ture and importance of metalworking, but her work

primarily deals with the production of items that

serve non-utilitarian functions and were empowered

with strong political and ideological meanings. It is

debatable whether these interpretations also apply

for the production of simple tools and implements

(fig. 1). In line with Costin’s (2001: 303) observation

that “assumptions about how local production is or-

ganized (and how it will ‘look’ like archaeologically)

are based on the general types of objects under study

(e. g. prestige goods as opposed to utilitarian tools)

and whether there were many or few in use” we may

be overemphasizing a particular part of metalwork

production at the expense of ‘simple’ metal tools,

but also at the expense of other crafts. For instance,

glass and faience production, also a Bronze Age in-

novation and a technology that has much in common

with metalworking (pyrotechnics, ‘alloying’ of cer-

tain ingredients), is assumed to be widely available

(Harding 2000: 266). The argument is that, although

complex, once mastered there “is no reason why the

technology should not have become widely available”

(Harding 2000: 266). Hence, no special role is attrib-

uted to its producers. In contrast, the argument that

the role of the metalworker is important is simply a

“given” (Harding 2005: 240–241). These assumptions

arose from the idea that metalworking has a ration-

al and scientific nature in contrast to “unscientific”

crafts (Budd/Taylor 1995: 134). There appears to be

a clear emphasis on discursive (rational and scien-

tific) knowledge, yet scholars often mention the skill

of the metalworker (e. g. Earle 2004: 161; Kristiansen/

Larsson 2005: 51–61; Vandkilde 2010) to argue for the

specialised nature of metalworking. Skill nonethe-

less has much more to do with technique (sensu In-

gold 1990: 7) and is acquired by the repeated bodily

engagement with the material, which can be seen as

non-discursive (see Kuijpers in prep. for a more thor-

ough discussion). In regard to these issues, on what

(archaeological) grounds, besides the vast amount of

bronze objects found, is metalworking to be consid-

ered a more special and confined craft?

Another bias is the androcentric attitude towards

metalworking (but see: Sørensen 1996). Even though

ethnography tells us metalworking is predominantly

practiced by males, there is very little to go on in the

archaeological record. We simply do not know. Ongoing

research on possible metalworkers’ burials will surely

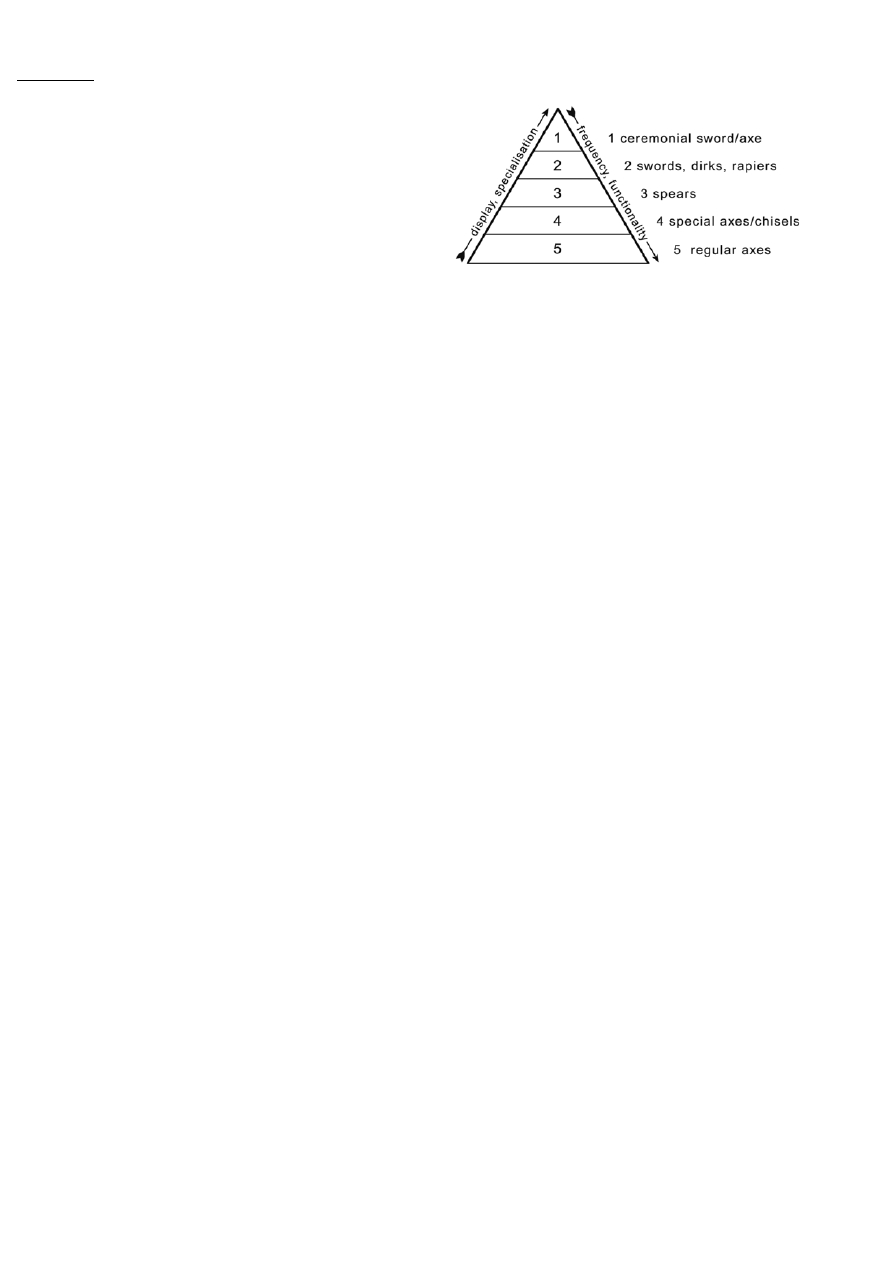

Fig. 1: Structure of the Bronze Age metalwork repertoire. Special-

ist metalworking only forms the top of the pyramid. The current

explanatory and analytical frameworks somewhat neglect the

producers of group 4 and 5 items, the bulk of the metalwork rep-

ertoire. We might even add a sixth group here; simple tools (figure

taken from Fontijn 2002).

3

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Metalworking Technology

solve the biological sex issue. From the perspective of

gender, the issue, however, is more challenging, as en-

gendering of technology can be very complicated (cf.

Dobres 1999: 132–134).

Let us turn to some of the specific arguments that

have been made to explain the inherent more diffi-

cult nature of metalworking over other technologies.

Bridgeford, for instance, argues that more special-

ised knowledge is needed for metalworking because

the completed object has to be fully conceptualised

by its maker in the first stages of production (when

producing the mould). This, in contrast to flint, stone,

wood and bone, which are gradually changed from

the unworked shape to that of the final object (Bridg-

eford 2002: 124). Although she is right that the pro-

duction process is profoundly different, she takes the

argument much too far, as her reasoning implies that

craftsmen working with other materials than metal

would not have been working from a fully precon-

ceived conceptualised idea. However, the difference,

I would argue, is not in the conceptualisation, but in

the technology and techniques used and subsequent-

ly the ideas attached to them (see below).

A second example can be found in Kristiansen and

Larsson (2005: 53): “The rise of the smith and of metal-

lurgy is accompanied by a new specialised knowledge

of firing and pyrotechniques, which could be used for

other purposes as well. They included improved firing

techniques for pottery production, new skills in glass

and bead production, but also new fire rituals and new

traditions in cooking and chiefly cuisine.” Again, the

argument, in my opinion, is taken too far as it implies

only one-way traffic of techniques (from the ‘better’

technology towards the more mundane). Yet, pyro-

technical knowledge for instance, mainly for the pro-

duction of pottery, had been around for thousands of

years and the assumption that this knowledge facili-

tated metalworking technology in the first place could

be equally valid. The exact relationship and manner

in which indigenous pyrotechnology was adapted to

facilitate smelting is still a matter of debate (Roberts

2009: 133–134). We do not yet have answers to these

question and most likely influences and technological

knowledge between crafts went both ways. As mould-

ing is such an important aspect of metalworking and

moulds are often made from clay, there is an obvious

and important link with pottery. Possibly, we need to

think of metalworking as a composite technology and

question whether we can even draw a line between

potters and metalworkers (Heeb 2009: 418). This con-

cept of technical relationships was also recently ad-

dressed by Sofaer (2006) who sees the exchange of

techniques in a social network of craftsmen. Both as-

sumptions discussed above on metalworking technol-

ogy are by no means evident from the archaeological

record but seem to stem from the aspiration to ad-

dress metalworking as an esoteric craft set apart from

more ‘mundane’ crafts such as basketry, pottery, tex-

tiles, stone or woodworking. The argument made by

Kristiansen and Larsson (2005) indirectly also clearly

implies progress, with metallurgy giving way to new

specialised knowledge. Technology, however, is not

simply about progress or improvement. Analyses of,

for instance, Early Bronze Age axes in Central Europe

show that the best method of production was con-

sciously not always followed (Kienlin 2008: 133–136;

2010). Furthermore, it has long since become clear

that especially the early copper and bronze objects

were not necessarily made with functionality in mind.

But what choices were made then and why? Which

characteristics of metalworking were regarded as

important? Hardness, colour, maybe even sound (cf.

Pearce 2007; Hosler 1995)? Clearly, archaeometallurgy

is not only about understanding the scientific analysis

of metal objects (discursive) and it is not only about

theorizing on metalworking as human behaviour.

It is the dialectic between these two, resulting in ar-

chaeologically and scientifically founded theories and

a technology with a human face (cf. Ottaway 2001;

Thornton 2009). “Without attention to the hows and

whys of everyday technical agency and the social con-

texts of those activities, descriptions will be little more

that static (albeit sequential) rather than dynamic ac-

counts of anthropological processes played out in and

on the ancient material world.” (Dobres 1999: 126). If

we truly want to understand metalworking technol-

ogy, we should perceive it as a process, not as static

finished artefacts, nor solely as a discursive technol-

ogy and devoid of any human agency.

It is here that I wish to address the long under-

stood, yet underused concept of technology as a total

social phenomenon

(Mauss 2002; Pfaffenberger 1988:

244). Technology is a product of human choices and

social processes (Dobres/Hoffman 1994; Dobres 1999;

Pfaffenberger 1988; 1992) and hence understanding

technology goes beyond mere practicalities. Although

clearly a social constructionist approach (cf. Killick

2004), this is not an attempt to discredit the scientific

approach. The latter provides the framework within

the possibilities, and thus choices, have to be made.

It is these choices, visible in the objects and made by

the prehistoric metalworker, that might tell us more

about the people involved and the organization of the

craft. Hence, instead of studying the products of this

technology as a goal in themselves and extrapolating

interpretations backwards onto the technology and

producers, the objects are better studied as a means

to understand the (technological) process from the

perspective of the prehistoric metalworkers. What

were their interest? (cf. Kienlin 2008) and how did

they go about their craft? In a sense, it is exploring

what it means to become a metalworker (cf. Budden/

Sofaer 2009). I am making the assumption here that

from the choices and skill involved we may postulate

what was created by whom, because you are what you

make (Marx/Engels 1970: 42). Following, if we have a

4

Maikel H. G. Kuijpers

better understanding of who crafted this in turn also

leads to a better understanding of the perspective

communicated and hence a reassessment of the im-

portance of metal.

Ritualizing metalworking, mystify-

ing understanding?

Recently, Dobres (2010) discussed two of the ‘main-

stream’ approaches towards technology to which she

refers as the “practical” and the “cultural” reason

ontology.

2

The former of which “employs a methodo-

logical and epistemological hierarchy cautioning ar-

chaeologists first to indentify and hold constant the

material (and hence knowable) aspects of the tech-

noenvironmental dyad before addressing the ‘softer’

aspect of ancient technology, such as social relations

or beliefs” (Dobres 2010: 105). Her analysis appears to

apply well to the metallurgical discourse. Although

Childe already mentioned the importance of the so-

cial aspects of technology, metallurgical research in

the second half of the twentieth century has empha-

sized the knowable or ‘hard’ aspect of metallurgy.

3

In

the wake of post-processualism, this was followed by

a sudden and passionate focus on ritual and symbolic

(‘soft’) aspects. Scholars convincingly argued that the

‘industrial model’ was not a satisfactory explanation

(notably Budd/Taylor 1995) and shifted the focus to-

wards the ‘soft’ aspect of metalworking technology;

rituals, magic, symbolic meaning and the control over

esoteric knowledge. What Budd and Taylor effective-

ly did in their pivotal paper was discredit the biased

‘industrial model’ (which they saw as an anachronis-

tic back-projection of the modern notion of techno-

logical change) only to replace it with a ‘ritual model’

that can be seen as equally biased. Even though they

argue that the ‘industrial model’ is not supported by

archaeological data, they themselves too fail to sup-

port their idea of ritual metalworking with empirical

data and base the whole argument on ethnographic

analogies and folklore. Even today the supposed rit-

ual dimension of metalworking is seldom corrobo-

rated by archaeological data. Instead, arguments are

usually rooted in uncritically applied ethnographical

analogies (Roberts 2008: 357).

The sparse available archaeological evidence that

is used to argue in favour of a ritual explanation can

generally be placed in two groups. (1) Metalwork-

ing debris and/or equipment that is found in a non-

domestic context such as burials, caves, ponds or the

2 Practical reason ontologies are explicitly materialists and

focus on the artefact itself and the universality of artefact

physics, while the cultural reason ontologies approach

ancient technology “as if people mattered” (Dobres 2010:

104–105).

3 E. g. Coghlan 1975; Craddock 1995; Ottaway 1994; Tylecote

1987 and the SAM series.

deliberate deposition of metalworking related arte-

facts.

4

(2) Metalworking debris and/or equipment in

a domestic context, but treated in a ‘ritual manner’

(the carefully deposited debris in a certain part of the

settlement).

5

Besides the ambiguous nature of some

of these finds there are two theoretical issues I wish

to address.

6

First of all, there is the well-known and intensely

discussed problem that interpreting finds as ‘ritual’

remains a precarious task. Identifying ritual as such

is often based on the fact that it is regarded as an irra-

tional, non-functional act. In this manner, finds such

as the depositions from Springfield (Needham 1993)

or Norton Fitzwarren (Ellis 1989) may then be used as

evidence for the ritual dimension of metalworking.

However, it is our definition of the term ‘ritual’ that

makes this find stand out rather than its actual mean-

ing, which we do not know exactly.

7

It is our defini-

tion of ritual that dictates our ability to find ritual

in the archaeological record. In this manner ‘ritual’

becomes an analytical tool, because these a priori def-

initions of ritual create the conditions by which to

recognise ritual practices in the archaeological data.

By no means, however, can we be sure that these con-

ditions also applied in prehistoric time. More impor-

tantly, are we really advancing our understanding of

the craft when we work with these preconditioned

ideas on ritual? How does labelling these finds ‘rit-

ual’ in contrast to ‘mundane’ help us understand the

organisation and importance of the craft? As Goody

(1961: 160–161) argued, “because the elucidation of

these relationships is given explanatory force, there

is a tendency to assume the presence of such con-

cepts on evidence of a rather slender kind”. What ex-

actly it explains is questionably vague. ‘Ritual’ is not a

proper explanation of why the depositions are there,

it simply acknowledges the anomaly. More impor-

tantly, this should not be extrapolated to explain the

role of metalworking. Therefore, I would argue that

we have to be cautious about using these exceptional

cases to argue for the importance or special nature

of metalworking in the Bronze Age. We do not know

whether the people who deposited these artefacts

saw this action as a non-functional or indeed ritual

(cf. Bell 1992; Brück 1999).

4 E. g. metalworking evidence found amongst cairns at Dain-

ton, Devon, UK (Needham 1980); or a ceremonial site (The

King’s stables, County Armagh, Northern Ireland) (Lynn

1977).

5 E. g. clay refractories deposited in a ditch at Springfield

Lyons, Essex, UK (Buckley/Hedges 1987; Needham 1993). A

deposition of a pot filled with clay mould fragments in a pit

at Norton Fitzwarren, Somerset, UK (Ellis 1989).

6 For a more thorough discussion on the problems of the

‘ritual’ evidence see Kuijpers (2008: 27–30, 58–66).

7 Interpretation for the Norton Fitzwarren deposit vary from

being a foundation deposit (Ellis 1989), the representation of

fertility rituals (Brück 2001) or referring to everyday society

and economy (Bradley 2005).

5

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Metalworking Technology

This brings us to the second point. Several au-

thors have recently argued that clear distinctions

like ‘gift – commodity’ or ‘ritual – profane’ do not re-

ally exist.

8

One way to deal with this problem is to

work from the archaeological record and look for

categories made by the people being studied. This

emic

approach involves trying to recognize specific

practices of social action that are distinguished from

other activities as a separate ‘field of discourse’ by

the people involved (Fontijn 2002: 21). Fontijn’s work

on depositions follows such an approach. He is in-

terested in patterns that occur in the deposition of

bronzes, without taking a pre-determined stance in

the ritual debate. In his concluding chapter on depo-

sitions, he writes that these depositions are ‘ritual-

ised’, but explicitly notes that there is no evidence

that this reflects the profane-ritual dichotomy in

which ritual is a meaningless, traditional behaviour,

nor to the theory that ritual permeates all fields of

life (Fontijn 2002: 276–277). Hence, the title of his

book: selective deposition (personal communication

Fontijn, October 2009).

Coming back to metalworking; neither when ad-

hering to the traditional evidence (i. e. the evidence

we deem non-functional) nor in the vein of Fontijn’s

emic approach, a strong case can be made for ritual

metalworking (Kuijpers 2008: 60–66; Sørensen 1996:

49; contra: Meurkens 2004). At present no clear pat-

tern can be discerned from the evidence related to

metalworking, although Jantzen’s work in Northern

Germany and South Scandinavia shows that there is

the possibility of metalworking production deliber-

ately being practiced at the foot of burials mounds

(Jantzen 2008: 311). Furthermore, as mentioned

above, it raises other questions. Even if we assume

that rituals were an important aspect of metalwork-

ing, does this help us understand the organisation of

the craft of metalworking? It appears to be a blind al-

ley as assuming ritual often stops further explanation

and examination of the available evidence.

Ethno-archaeological and anthropo-

logical informed interpretation

With the lack of conclusive archaeological data on

metalworking, archaeologists have turned after an-

thropological and ethnographic examples. In our

modern-day world, where science and technology

could not be further away from ritual and myths, this

might help us understand the unfamiliar concept of

societies where ‘science’ and technology have not yet

witnessed a break from the sacred (e. g. the concept

alchemy). It should, however, not lead to the uncriti-

cal use of just any ethnographic or anthropological

analogy. We very much run the risk of applying ex-

8 E. g. Bazelmans 1999; Brück 1999; Fontijn 2002; Bradley 2005.

amples from cultural contexts that have little in com-

mon with the Bronze Age. Both Rowlands (1971) and

Herbert (1984: 33) noticed that the way in which the

metalworker is perceived differs considerately per

society. The status given to metalworkers varies from

awe and respect to fear and contempt. Furthermore,

by highlighting only the craft of metalworking and

certain ritual aspects of that craft, we de-contextu-

alise it at the same time; effectively denying its links

with other crafts and aspects of society. Whilst the

plethora of myths and rituals, ranging from singing

to human sacrifice in the furnace, strongly suggests

that metalworking is a ritualized practise in many

societies,

9

it cannot tell us anything more (besides ar-

chaeologically unfounded suggestions), about rituals,

the importance, or the organisation of metalworking

in the Bronze Age. Additionally, technology in small-

scale societies is often regulated with rituals, taboos

and regulation, which are an integral part of the tech-

nological process. Rituals help co-ordinate labour and

impose a framework of organization (Gell 1988: 3–4,

Pfaffenberger 1992: 501). To the people involved, rit-

uals are thus often as functional as the actual work

itself. However, even if people believe that one ac-

tion, for instance mining, cannot take place without

the slaughtering of a white sheep

10

and see both as

equally important, the observant anthropologists

and ethno-archaeologists may distinguish between

the functional actions and non-functional (ritual) ac-

tions taken. Thus a decision has to be made by the

researcher for either an emic or etic approach. Inter-

pretations coming from both approaches are legiti-

mate but produce conclusions that are partly reveal-

ing, partly concealing. Singling-out a ritual act might

reveal an intriguing action, but at the same time de-

contextualises the act and hence conceals the wider

framework of processes and societal organisation in

which it should be placed, losing the “thick descrip-

tion” (Geertz 1973) and hence deeper understanding

of the act. Trying to describe process from an emic

perspective may reveal the enormous complexity

of social actions (of which technology is one), but

does not necessarily make it more comprehensible

for researchers with a Cartesian background. Ethno-

archaeologists already have so much trouble under-

standing production practices from an emic view

and in this regard Roberts makes a depressing, yet

fair, point when he mentions that: “Archaeologists

will never be able to observe metal production or

deposition being performed in its social setting while

painstaking experimental reconstructions based on

archaeological, archaeometallurgical and even (eth-

no) historical data will never be as immediately illu-

9 E. g. Barndon 2004; Bekeart 1998; Childs 2000; Haaland 2004;

Herbert 1984.

10 The slaughtering of a white sheep is necessary to ensure that

the ore in the mine would not die (Childs 2000: 205).

6

Maikel H. G. Kuijpers

interpretations.

11

To put it simply, for the “complex”

society we postulate in the Bronze Age, the emphasis

on bronze is surprising. In our contemporary society

it would be hard not to see the importance of plastic,

yet one would agree that any interpretation of West-

ern society based too much on plastic artefacts only,

would not lead to a very balanced interpretation.

Conversely to the arguments given above, my inten-

tion is not necessarily to downplay the importance of

metalworking, but rather to put it in its proper con-

text, together with other crafts.

With regards to the introduction of metallurgy,

I advocate that it did not create its own necessity, it

simply brought a new set of possibilities to a situation,

which had to be negotiated and bargained for (cf. So-

faer/Sørensen in press). Or, as argued by Roberts et.

al. (2009: 1012), people did not need metal, they wanted

metal. And why they wanted metal cannot simply be

explained by a supposed superiority of metal over

other materials and technologies or its assumed eco-

nomical importance. It is questionable whether tech-

nology carries with it any necessary or consequent

pattern of social and cultural evolution (Costin 2001:

288–289; Pfaffenberger 1988: 240).

12

In line with this

we have to be careful that the argument for metallur-

gy as the driving factor behind complexity, individu-

ality, and a basis for power, wealth and elites, is not

reduced to a simple post hoc ergo propter hoc.

A final argument against the link between elites

and metal would be the circular reasoning which is

identifiable in the discourse. Metalworking is seen

as a high status, specialist job and consequently ritu-

als and magic must be attached to it. Or, ritual met-

alworking is surmised, as suggested by ethnographic

examples, and consequently Bronze Age metalwork-

ing must either be the work of specialist, chiefs or

other high-status, powerful persons (cf. Budd/Taylor

1995).

Conclusion

In this article I have explored and discussed the

two important questions that have been the focus

of research for several decades. Why was metalwork-

ing adopted?

And what was the role of metalworking in

Bronze Age societies (how important was bronze)?

The

latter question involves understanding the organisa-

tion and meaning of the craft. I have argued that this

can be best done by means of a thorough study of

its technology and especially its producers in order

11 For instance, in Harding’s (2000) “European Societies in

the Bronze Age”, there is a whole chapter devoted to metal

(ch. 6) and one chapter for all the other crafts (ch. 7: “Other

Crafts”). Sofaer (2006: 139) also points at the inconsistent

ranking of Bronze Age crafts given the links that she sees

between them.

12 Pfaffenberger even considers it as fundamentally wrong.

minating as actual observation.” (Roberts 2008: 357).

The opportunities for archaeologist to understand

social perspectives of a technology then seem rather

bleak. Ethnographical and anthropological analogies

are therefore a very welcome source of information,

providing us with different ideas and possibilities in

the manner in which metalworking may function in a

society. Yet, we should be aware not to simply ‘copy’

only the interpretation we are interested in. Moreo-

ver, in line with the emic-etic approach, archaeomet-

allurgists should ask themselves; are we trying to

understand Bronze Age metalworking technology on

our terms or theirs?

Metal and elites

There is no doubt that bronze played an important

role in the prehistory of Europe as new types of ob-

jects appear, especially weapons, and metal becomes

a widely used material, which implies that much of

Europe had to be involved in trade networks and

adapted to the ‘consequences’ of metallurgy (i. e. cop-

per and tin supply, charcoal production, production

of refractory materials etc.). Metalworking undoubt-

edly had a (disrupting) effect on society, challenging

familiar constitutions of society (Sofaer/Sørensen

in press), but possibly also changing the prehistoric

conceptions of production and time. The production

of bronze involves a period in which the process can-

not be interrupted without resulting in a failed prod-

uct (i. e. the casting). On the other hand, the inher-

ent qualities of bronze lend themselves to re-melting,

rendering the idea of the irreversible of former pro-

duction processes (e. g. stone, pottery after baking)

obsolete. Concepts of temporality may thus have

changed during the inception of Bronze Age tech-

nology. Furthermore, this technology opened up the

possibility of repetition as the same mould can be

used to cast multiple objects. All in all, we may as-

sume that this new technology could have lead to

whole new epistemologies (personal communication

T. F. Sørensen, February 2011). However, this does not

mean that metallurgy inevitable had to be adopted

and lead to the emergence of socio-political elites and

a more complex society. As mentioned before, there

are two distinct lines of questioning at play here. The

impact of metallurgy on Early Bronze Age societies

has been used to explain cultural and social change

and has been overtly painted in terms of elites, which

can be traced back to the rich graves of Varna but

is more problematic outside this site (Kienlin 2010).

This causal link between powerful elites and metal

fits in rather well with the notions of Bronze Age

complexity and advancing societies, but is far less ev-

ident from the archaeological record. There is more

to the Bronze Age than only metal, yet other crafts

literarily seem to have to fight for their place in our

7

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Metalworking Technology

to understand the perspective being communicated.

Metalworking is often regarded as a highly special-

ized and ritual craft for which the skilfully made ob-

jects are used to argue for the control over esoteric

knowledge. In this paper I have advocated that these

assumptions should not yet be taken for granted.

In contrast to the discursive knowledge needed for

metalworking, the non-discursive aspects are under-

studied and hence the perceived link between skill

and confined knowledge is questionable. Further-

more, the postulated ritual aspects are problematic.

Nonetheless, this article has not been an attempt to

dismiss the ritual or symbolic interpretations, nor to

delve into the discussion of how to recognize ritual.

Rather, I hope to have highlighted that in under-

standing the craft of metalworking and its impor-

tance in Bronze Age societies we must be aware not

to overplay the term ‘ritual’. This interpretation may

not be helpful at all as it is seen as an explanation

in itself and thus prevents further explanation and

examination of the available evidence. The assump-

tion that the technological act of metalworking is a

very skilful one does not provide the necessary evi-

dence to set it apart as a separate practice or indeed

ritual. The organisation of metalworking may well

be accessed through a very thorough understanding

of the technology itself both on a scientific as well

as a theoretical level. Hence, following other lines of

questioning, such as investigating the choices made

by the prehistoric metalworker and recorded in the

objects (i. e. their experience with the material), may

provide a more fruitful approach to achieve a deep-

er understanding of metalworking technology and

what role it played in Bronze Age societies.

References

Barndon 2004

R. Barndon, A Discussion of Magic and Medicines in East

African Iron Working: Actors and Artefacts in Technology.

Norwegian Archaeological Review 37, 2004, 21–39.

Bartelheim 2009

M. Bartelheim, Elites and metals in the Central European

Early Bronze Age. In: T. L. Kienlin/B. W. Roberts (eds.),

Metals and Societies. Studies in honour of Barbara S. Ot-

taway. Bonn: Habelt 2009.

Bazelmans 1999

J. Bazelmans, By weapons made worthy. Lords, retainers

and their relationship in Beowulf. Amsterdam: Amsterdam

University Press 1999.

Bekeart 1998

S. Bekeart, Multiple levels of meaning and the tension of

consciousness. How to interpret iron technology in Bantu

Africa. Archaeological Dialogues 5, 1998, 6–29.

Bell 1992

C. Bell, Ritual theory, Ritual practice. New York: Oxford

University Press 1992.

Bisson 2000

M. S. Bisson, Precolonial Copper Metallurgy: Sociopolitical

Context. In: J. O. Vogel (ed.), Ancient African Metallurgy.

The Sociocultural Context. New York: Altamira Press 2000,

83–147.

Bradley 1990

R. Bradley, The passage of arms. An archaeological analy-

sis of prehistoric hoards and votive deposits. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press 1990.

Bradley 2005

R. Bradley, Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe.

Londen: Routledge 2005.

Bradley 2007

R. Bradley, The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press 2007.

Bridgeford 2002

S. D. Bridgeford, Bronze and the First Arms Race – Cause,

Effect or Coincidence? In: B. S. Ottaway/E. C. Wager (eds.),

Metals and Society. Papers from a session held at the Euro-

pean Association of Archaeologists Sixth Annual Meeting

in Lisbon 2000. Oxford: Archaeopress 2002, 123–133.

Brück 1999

J. Brück, Ritual and Rationality: some problems of inter-

pretation in European Archaeology. European Journal of

Archaeology 2, 1999, 313–344.

Brück 2001

J. Brück, Body metaphors and technologies of transforma-

tion in the English Middle and Late Bronze Age. In: J. Brück

(ed.), Bronze Age landscapes, tradition and transforma-

tion. Oxford: Oxbow, 2001, 149–60.

Buckley/Hedges 1987

D. G. Buckley/J. D. Hedges, The Bronze Age and Saxon settle-

ments at Springfield Lyons, Essex: an interim report. County

Council Archaeology Section Occasional Paper 5, 1987.

Budd/Taylor 1995

P. Budd/T. Taylor, The faerie smith meets the bronze indus-

try: magic versus science in the interpretation of prehis-

toric metal-making. World Archaeology 27, 1995, 133–143.

Budden/Sofaer 2009

S. Budden/J. Sofaer, Non-Discursive Knowledge and the

Construction of Identity. Potters, Potting and Performance

at the Bronze Age Tell of Százhalombatta, Hungary. Cam-

bridge Archaeological Journal 19, 2009, 203–220.

Childe 1944

V. G. Childe, Archaeological Ages as Technological Stages.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 74, 1944,

7–24.

Childs 2000

S. T. Childs, Traditional Iron Working: A Narrated Ethnoar-

chaeological Example. In: J. O. Vogel (ed.), Ancient African

Metallurgy. The Sociocultural context. New York: Altamira

Press 2000, 199–253.

Coghlan 1975

H. H. Coghlan, Notes on the prehistoric metallurgy of cop-

per and bronze in the Old World. Oxford: Oxford Univer-

sity Press 1975.

Costin 2001

C. L. Costin, Craft Production Systems. In: G. M. Feinman/D.

Price (eds.), Archaeology at the millenium A sourcebook.

New York: Kluwer 2001, 273–329.

Craddock 1995

P. T. Craddock, Early Metal Mining and Production. Edin-

burgh: Edinburgh University Press 1995.

Dobres 1999

M.-A. Dobres, Technology‘s Links and Chaînes: The Proc-

essual Unfolding of Technique and Technician. In: M-A.

Dobres/C.R. Hoffman (eds.), The Social Dynamics of Tech-

nology: Practice, Politics, and World Views. Washington

D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press 1999.

Dobres 2010

M.-A. Dobres, Archaeologies of technology. Cambridge

Journal of Economics, 34, 2010, 103–14.

8

Maikel H. G. Kuijpers

Dobres/Hoffman 1994

M.-A. Dobres/C. R. Hoffman, Social agency and the dynam-

ics of prehistoric technology. Journal of Archaeological

Method and Theory 1, 1994, 211–256.

Earle 2004

T. Earle, Culture Matters: Why Symbolic Objects Change.

In: E. DeMarrais/C. Gosden/C. Renfrew (eds.), Rethinking

materiality. The engagement of mind with the material

world. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological

Research 2004, 153–167.

Ellis 1989

P. Ellis, Norton Fitzwarren hillfort: a report on the exca-

vations by Nancy and Philip Longmaid between 1968 and

1971. Somerset Archaeology and Natural History 133, 1989,

1–74

Fontijn 2002

D. R. Fontijn, Sacrificial landscapes. Cultural biographies of

persons, objects and ‘natural’ places in the Bronze Age of

the Southern Netherlands, c. 2300–600 BC. Analecta Prae-

historia Leidensia 33/34, 2002.

Geertz 1973

C. Geertz, The interpretation of cultures; selected essays.

New York: Basic Books 1973.

Gell 1988

A. Gell, Technology and Magic. Anthropology Today 4,

1988, 6–9.

Goody 1961

J. Goody, Religion and Ritual: The Definitional Problem.

British Journal of Sociology, 12, 1961, 142–64.

Haaland 2004

R. Haaland, Technology, transformation and symbolism:

ethnographic perspectives on European iron working.

Norwegian Archaeological Review 37, 2004, 1–19.

Harding 2000

A. F. Harding, European societies in the Bronze Age. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press 2000.

Heeb 2009

J. Heeb, Thinking Through Technology – An Experimental

Approach to the Copper Axes from Southeastern Europe.

In: T. L. Kienlin/B. W. Roberts (eds.), Metals and Societies.

Studies in honour of Barbara S. Ottaway. Bonn: Habelt

2009, 415–420.

Helms 1993

M. W. Helms, Craft and the Kingly Ideal. Art, trade, and

power. Austin: University of Texas Press 1993.

Herbert 1984

E. G. Herbert, Red gold of Africa. Copper in Precolonial His-

tory and Culture. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin

Press 1984.

Hosler 1995

D. Hosler, The Sounds and Colors of Power: The Sacred

Metallurgical Technology of Ancient West Mexico. World

Archaeology 27, 1995, 100–115.

Ingold 1990

T. Ingold, Society, nature and the concept of technology

Archaeological Review from Cambridge 9, 1990, 5–17.

Jantzen 2008

D. Jantzen, Quellen zur Metallverarbeitung im nordischen

kreis der Bronzezeit. Prähistorische Bronzefunde XIX,2.

Stuttgart: Franz Steiner 2008.

Kienlin 2007

T. L. Kienlin, Von den Schmieden der Beile: Zu Verbreitung

und Angleichung metallurgischen Wissens im Verlauf der

Frühbronzezeit. Prähistorische Zeitschrift 82, 2007, 1–22.

Kienlin 2008

T. L Kienlin, Frühes Metall im Nordalpinen Raum. Eine Un-

tersuchung zu technologischen und kognitiven Aspekten

früher Metallurgie anhand der Gefüge frühbronzezeitli-

cher Beile. Bonn: Habelt 2008.

Kienlin 2010

T. L. Kienlin, Traditions and Transformations: Approaches

to Eneolithic (Copper Age) and Bronze Age Metalworking

and Society in Eastern Central Europe and the Carpathian

Basin. BAR International Series 2184. Oxford: Archaeo-

press 2010.

Killick 2004

D. Killick, Social Constructionist Approaches to the Study

of Technology. World Archaeology 36, 2004, 571–578.

Kristiansen 1987

K. Kristiansen, From stone to bronze – the evolution of so-

cial complexity in Northern Europe, 2300–1200 BC. In: E.

M. Brumfield/T. Earle (eds.), Specialization, exchange and

complex societies. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press

1987, 30–51.

Kristiansen/Larsson 2005

K. Kristiansen/B. Larsson, The rise of Bronze Age society.

Travels, Transmissions and Transformations. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press 2005.

Kuijpers 2008

M. H. G. Kuijpers, Bronze Age metalworking in the Nether-

lands (c. 2000–800BC). A research into the preservation of

metallurgy related artefacts and the social position of the

smith. Leiden: Sidestone Press 2008.

Kuijpers in prep.

M. H. G. Kuijpers, Sound of fire, smell of copper, feel of

bronze, colours of the cast – sensory aspects of metal-

working technology. In: M. L. S. Sørensen/K. Rebay/L. B.

Jørgensen/J. Hughes (eds.), Embodied Knowledge: Histori-

cal Perspectives on Technology and Belief.

Lynn 1977

C. J. Lynn, Trial excavations at the King’s stables, Tray

Twonland, County Armargh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology

40, 1977, 42–62.

Martinón-Torres 2002

P. M. Martinón-Torres, Chaîne Opératoire: The concept and

its applications within the study of technology. Gallaecia

21, 2002, 29–43.

Marx/Engels 1970

K. Marx/F. Engels. The German ideology. In: C. J. Arthur

(ed.), The German ideology. London: Lawrence and Wishart

1970.

Mauss 2002

M. Mauss, The Gift. The form and reason for exchange in

archaic societies. London: Routledge 2002.

Meurkens 2004

L. Meurkens, A matter of Elites, Specialists and Ritual?

Social and symbolic dimension of metalworking in the

North-west European Bronze Age. Unpublished Master

Thesis. Leiden: University of Leiden 2004.

Needham 1980

S. P. Needham, An assemblage of Late Bronze Age metal-

working debris from Dainton, Devon. Proceedings of the

Prehistoric Society 46, 1980, 177–215.

Needham 1993

S. P. Needham. The structure of settlement and ritual

in the Late Bronze Age of south-eastern Britain. In: C.

Mordant/A. Richard (eds.), L’Habitat et l’Occupation du

Sol à l’Age du Bronze en Europe. Paris. Comité des Travaux

Historiques et Scientifiques. Documents Préhistoriques 4,

1993, 49–69.

Needham 2007

S. P. Needham, Bronze Makes a Bronze Age? Considering

the Systemics of Bronze Age Metal Use and the Implica-

tions of Selective Deposition. In: C. Burgess/P. Topping/F.

Lynch (eds.), Beyond Stonehenge. Essays on the Bronze

Age in honour of Colin Burgess. Oxford: Oxbow 2007, 278–

287.

Ottaway 1994

B. S. Ottaway, Prähistorische Archäometallurgie. Espel-

kamp: Verlag Marie Leidorf, 1994.

Ottaway 2001

B. S. Ottaway, Innovation, production and specialisation in

early prehistoric copper metallurgy. European Journal of

Archaeology 4, 2001, 87–112.

9

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Metalworking Technology

Pare 2000

C. F. E. Pare, Bronze and the Bronze Age. In: C. F. E. Pare

(ed.), Metals make the world go round. The supply and cir-

culation of metals in Bronze Age Europe. Oxford: Oxbow

2000, 1–38.

Pearce 2007

M. Pearce, Bright Blades and Red Metal. Essays on North

Italian Prehistoric Metalwork. Accordia Specialist Studies

on Italy 14. London: Accordia Research Institute 2007.

Pfaffenberger 1988

B. Pfaffenberger, Fetishised Objects and Humanised Na-

ture: Towards an Anthropology of Technology. Man 23,

1988, 236–252.

Pfaffenberger 1992

B. Pfaffenberger, Social anthropology of Technology. An-

nual Review of Anthropology 21, 1994, 491–516.

Roberts 2008

B. Roberts, Creating traditions and shaping technologies:

understanding the earliest metal objects and metal pro-

duction in Western Europe. World Archaeology 40, 2008,

354 – 372.

Roberts 2009

B. Roberts, Production Networks and Consumer Choice in

the Earliest Metal of Western Europe.

Journal of World Pre-

history

22, 2009, 461–481.

Roberts/Thornton/Pigott 2009

B. W. Roberts/C. P. Thornton/V. C. Pigott, Development of

metallurgy in Eurasia. Antiquity 83, 2009, 1012–1022.

Rowlands 1971

M. J. Rowlands, The archaeological interpretation of pre-

historic metalworking. World Archaeology 3, 1971, 210–

223.

Sofaer 2006

J. R. Sofaer, Pots, Houses and Metal: Technological relations

at the Bronze Age tell at Százhalombatta, Hungary. Oxford

Journal of Archaeology 25, 2006, 127–147.

Sofaer/Sørensen in press

J. Sofaer/M. L. S. Sørensen, Technological change as so-

cial change: the introduction of metal in Europe. In: M.

Bartelheim/V. Heyd (eds.), Continuity – Discontinuity:

Transition Periods in European Prehistory. Forschungen

zur Archäometrie und Altertumwissenschaft.

Sørensen 1996

M. L. S. Sørensen, Women as/and metalworking. In: B.

Devonshire/B. Wood (eds.), Women in industry and tech-

nology from prehistory to the present day. Current Re-

search and the Museum Experience Proceedings from the

1994 WHAM conference. London: Museum of London 1996.

Thornton 2009

C. P. Thornton, Archaeometallurgy: Evidence of a Para-

digm Shift? In: T. L. Kienlin/B.W. Roberts (eds.), Metals and

Societies. Studies in honour of Barbara S. Ottaway. Bonn:

Habelt 2009, 25–33.

Tylecote 1987

R. F. Tylecote, The early history of metallurgy in Europe.

London: Longman 1987.

Vandkilde 2010

H. Vandkilde, Metallurgy, Inequality and Globalization in

the Bronze Age – a commentary on the papers in the met-

allurgy session. In: H. Meller/F. Bertemes (eds.), Der Griff

nach den Sternen. Wie Europas Eliten zu Macht und Reich-

tum kamen. Halle: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Ar-

chäologie Sachsen-Anhalt 2010, 903–910.

Winghart 1998

S. Winghart, Produktion, Verarbeitung und Distribution –

Zur Rolle spätbronzezeitlichen Eliten im Alpenvorland. In:

B. Hänsel (ed.), Mensch und Umwelt in der Bronzezeit Eu-

ropas. Man and environment in European Bronze Age. Kiel:

Oetker-Voges 1998, 261–264.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Towards an understanding of the distinctive nature of translation studies

(Trading) Paul Counsel Towards An Understanding Of The Psychology Of Risk And Succes

DISTILLING KNOWLEDGE new histories of science, technology, and medicine

Drilling Fluid Yield Stress Measurement Techniques for Improved understanding of critical fluid p

Eric Racine Pragmatic Neuroethics Improving Treatment and Understanding of the Mind Brain Basic Bioe

Towards a Unified Theory of Cryptographic Agents

towards a chicago school of youth organizing

Dehaene & Nacchache Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness

Beardsworth Towards a Critical Culture of the Image

9[1] G Reid, Improved Understanding of

Salvation and Creativity Two Understandings of Christianity

perkins feminist understanding of productivity

Junco, Merson The Effect of Gender, Ethnicity, and Income on College Students’ Use of Communication

Bowser B J Toward an Archaeology of Place

Towards a re conceptualisation of embeddedness

DISTILLING KNOWLEDGE new histories of science, technology, and medicine

AGISA Towards Automatic Generation of Infection Signatures

Clive Grey TOWARDS AN OVERVIEW OF WORK ON GENDER AND LANGUAGE VARIATION htm(1)

więcej podobnych podstron