1

T

HE

D

ATING AND

D

ATABILITY OF

B

EOWULF IN AN

H

ISTORICAL AND

E

SCHATOLOGICAL

C

ONTEXT

2

Erica Steiner

Centre for Medieval Studies

University of Sydney

Thesis submitted to fulfill requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours),

University of Sydney, 2008.

1

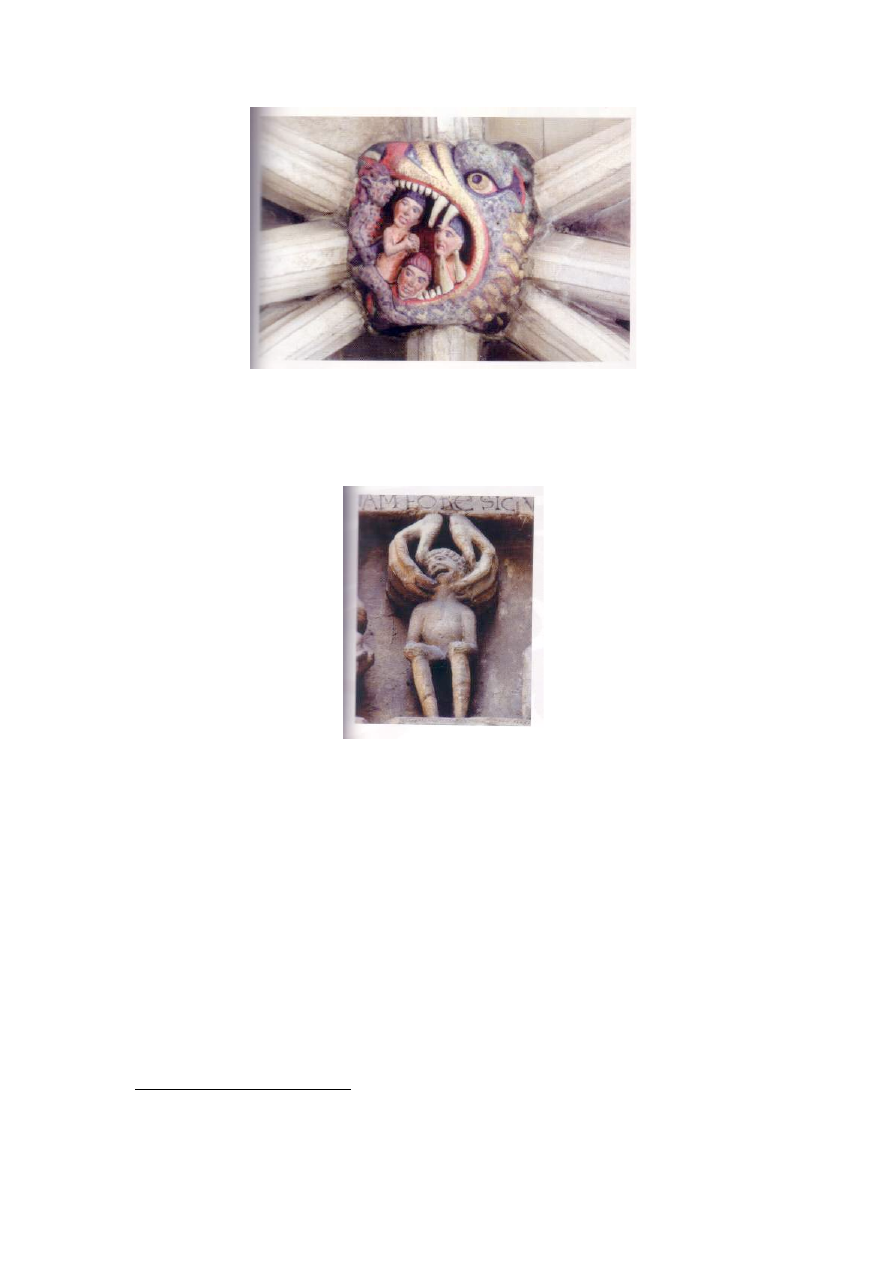

Roof Boss from Norwich Cathedral, c. 1145; Laura Ward & Will Steeds, Demons: Visions of Evil in

Art; Carlton Books, Ltd., 2007, p. 95.

2

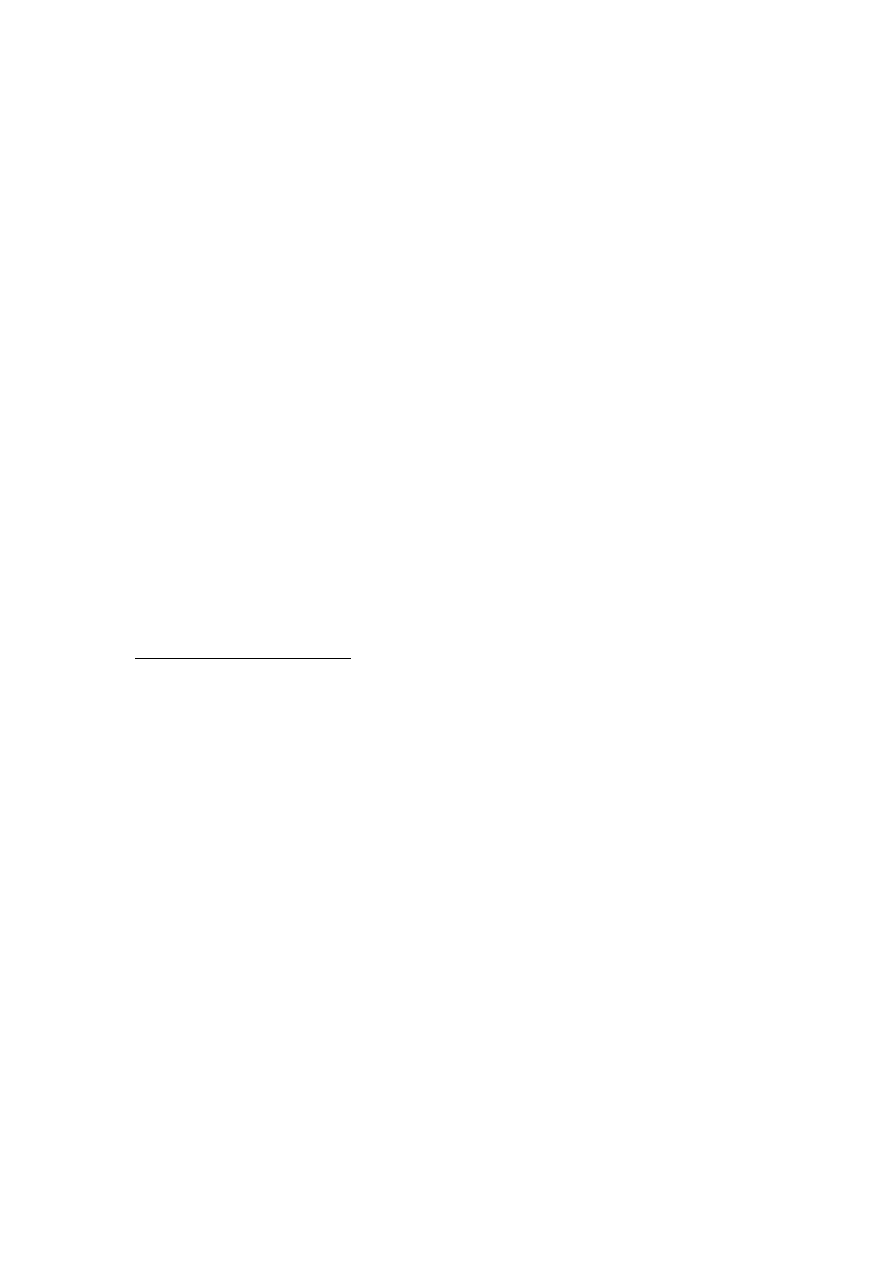

Scene from ‘The Last Judgement’ on the tympanum of the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun, France,

c. 1130-40; ibid, p. 131.

2

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

:

I am sincerely thankful for the endless patience of both my supervisor, Daniel

Anlezark, and course co-ordinator, John Pryor; the love and support of my parents

Karl and Katarina; and the eyes and ears of Michelle and Vicki, and all of my friends

– without whom this thesis would not have been the work it is.

*

*

*

For all the Old English texts used the source of the Old English was the

Dictionary of Old English Corpus in Electronic Form, (ed.) Antoinette di Paolo

Healey; Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto, 2005; except for Beowulf

which is taken from Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg, (ed.) Fr. Klaeber; D.C.

Heath & Co., 3

rd

ed., 1950, and the prose Guthlac, which is taken from Felix, Life of

Saint Guthlac, (trans.) Bertram Colgrave; Cambridge University Press, 1956, and the

poetic Guthlac, which is taken from The Guthlac Poems of the Exeter Book, (ed.) Jane

Roberts; Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press, 1979. All translations from the

Old English, where in single quotation marks, are my own, and where in double

quotation marks, are from Anglo-Saxon Poetry, (trans., ed.) S.A.J. Bradley;

Everyman’s Library, 2004; except for Beowulf, which is taken from Beowulf: A new

verse translation, (trans.) R.M. Liuzza; Broadview Literary Texts, 2000, unless other

wise specified, and the Riddles, taken from The Exeter Book Riddles, (trans.) Kevin

Crossley-Holland; Penguin Books, revised ed., 1993. The dictionary used was An

Anglo-Saxon Dictionary based on the manuscript collections of the late Joseph

Bosworth, (ed.) T. Northcote Toller; Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press, 1898;

http://beowulf.engl.uky.edu/~kiernan/BT/ Bosworth-Toller.htm.

For Old Norse texts, all translations are from the edition cited, and the

dictionary consulted throughout was Richard Cleasby & Gudbrand Vigfusson, An

Icelandic-English Dictionary, http://www.northvegr.org/vigfusson/index.php.

For Latin texts, translations given in single quotation marks are my own, and

in double quotation marks, from the edition cited. The dictionary consulted

throughout was Charlton T. Lewis & Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary; Oxford

University Press, Clarendon Press, 1958.

3

The Modern English dictionary consulted throughout was The Oxford English

Dictionary; http://www.dictionary.oed.com.

Regarding places referred to in England; the etymology was provided by The

Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names, Based on the collections of the

English Place-Name Society, (eds.) Victor Watts, John Insley, Margaret Gelling;

Cambridge University Press, 2004; the charters referred to are all taken from Sawyer,

P.H., Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated list and Bibliography; Offices of the

Royal Historical Society, London, 1968, and their contents from the Dictionary of Old

English Corpus in Electronic Form, (ed.) Antoinette di Paolo Healey; Centre for

Medieval Studies, University of Toronto, 2005.

4

T

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

:

Acknowledgements:

2

Introduction:

5

Chapter One: The Historical Context of Beowulf:

8

The Date of the Manuscript:

8

Scandinavian Influences:

11

Historical Concordances:

17

Chapter Two: The Religious Context of Beowulf:

22

Datable Aspects of Christianity and Heathenism in Beowulf:

23

Funeral Rites in Beowulf:

30

Chapter Three: The Eschatological Context of Beowulf:

40

The Barrow-Dweller:

43

The Draugar:

48

Removal of the Draugar:

71.

Conclusion:

77

Bibliography:

79

Primary Sources:

79

Secondary Sources:

84

5

I

NTRODUCTION

“The greater the distance between the date of the Beowulf

manuscript...and the posited date of the poem as we have it

now, the heavier the element of hypothesis.”

3

Almost every period of Anglo-Saxon history has been used to provide a

context for the date of the composition of Beowulf; but from the available evidence,

the date of highest probability may be whittled down to two periods: the middle third

of the eighth century and the first third of the tenth. In line with Eric Stanley’s

cautionary reminder, quoted above, Chapter One, will examine the physical evidence

of the manuscript that may help to locate a most likely date of composition for the

poem, which I believe, lies in the abovementioned latter period of the early tenth

century. Secondly, the historical realities of this period being one of close linguistic,

literary, and human relationships between the Scandinavians who had migrated to and

settled in parts of England, and the Anglo-Saxons, will be put forth as the historical

and social context of the poem. In Chapter Two, the religious scenery used in Beowulf

will be placed in the historical context of the transition from heathenism to

Christianity in Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Scandinavian England. Finally, Chapter

Three will be a case-study of the themes of cross-cultural interaction and borrowing

between Anglo-Saxons and (Anglo)-Scandinavians in an eschatological context

through the identification of a specific type of supernatural being, the barrow-dweller,

who through the influence of Christianity was transformed into a malevolent version

of its former self, the draugr. The barrow-dweller was a human who remained alive,

or was reanimated, within their grave that almost invariably was a barrow; while the

demonised characterisation of the draugr depends on the conception of not just the

barrow-dweller, but also giants, witches, demons and devils. The draugar may be

found in Beowulf, in the figures of Grendel and his mother, while the possibility that

Beowulf was perceived to have become a barrow-dweller will be briefly introduced.

Much of the evidence which may be used to date Beowulf lies outside of the

spatial limitations of this study; and of the majority of that which has been examined,

no more than a brief treatment was possible. Some of the evidence not examined

3

E.G. Stanley, ‘The Date of Beowulf: Some Doubts and No Conclusions’, The Dating of Beowulf, (ed.)

Colin Chase; University of Toronto Press, 1981, p.197.

6

includes the interesting approach of Jennifer Neville, who has looked at the

descriptions of horses in the poem, and shown them to be not in line with standards

of horses in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

4

In Roberta Frank’s study of the

similarities between the genre of the eulogy in Old English and Old Norse, she

concludes that the earliest examples of the former which date from the tenth century

may have been a direct result of the influence of the latter;

5

and Walter Goffart’s

identification of the Hugas, used as a by-name for the Franks in Beowulf, with the

followers and inhabitants of the lands of the Frankish ‘Hughs’,

6

rulers of Neustria

from the later ninth to mid-tenth century, brings him to conclude that “the poem was

written no earlier than in the second quarter of the tenth century...near the year 923

[CE].”

7

Others have noted the choice of the Geatas as the heroic race in the poem, to

point to the reign of Alfred, when an ancestry including the Geatas seemed to be

ideologically important to the West Saxons.

8

The form in which the personal and

tribal names have been preserved in the poem, has usually been taken to show that it

is an early composition,

9

and yet there also exists the strong likelihood that the

original spelling of Beowulf’s name was in fact Biowulf, which would accord with an

Anglo-Scandinavian dialect pronunciation according to Kevin Kiernan.

10

4

This may be explained by the disruptions to the breeding practices and stock over the course of the

Vikings’ depredations across England; or as a genuine unadulterated preservation of pre-ninth, or even

pre-seventh century conditions; or as a depiction of the Scandinavian horse breed akin to the modern

Norwegian Fjord Pony, (especially, p. 139-42, 152-3, and n. 49, the latter which states that c. 930 CE,

horses from this time on were ‘definitely’ unlike that in Beowulf); Jennifer Neville, ‘Hrothgar’s horses:

feral or thoroughbred?’, Anglo-Saxon England, v. 35, 2006, p. 131-57.

5

Robert E. Bjork & Anita Obermeier, ‘Date, Provenance, Author, Audiences’, A Beowulf Handbook,

(eds.) Robert E. Bjork & John D. Niles; University of Exeter Press, 1997, p. 23.

6

Hugh the Abbot, fl. 866-880’s CE, and Hugh the Great, 923-56 CE, the latter also married a sister of

King Æthelstan of Wessex in 926 CE.

7

Walter Goffart, ‘Hetware and Hugas: Datable Anachronisms in Beowulf’, The Dating of Beowulf,

(ed.) Colin Chase; University of Toronto Press, 1981, p. 100.

8

Jane Acomb Leake, The Geats of Beowulf: A Study in the Geographical Mythology of the Middle

Ages; University of Wisconsin Press, 1967, p. 12, is willing to place the writing of Beowulf either

“before the Viking incursions began on a large scale, or after the Danes had been settled in the

Danelaw and the process of assimilation had begun”; Craig R. Davis, ‘An Ethic Dating of Beowulf’,

Anglo-Saxon England, v. 35, 2006, p. 120-5, and John D. Niles, Old English Heroic Poems and the

Social Life of Texts; Brepols, 2007, p. 39-48, both place the generation of the myth of the West Saxons’

heroic ancestry from the Geatas in Alfred’s reign, and the latter also adds that the inclusion of the

character of Wiglaf into the poem must date from after the death of his grandson, Wihstan son of

Wigmund (the name of Wiglaf’s father in Beowulf is Weohstan/Wigstan, son of Wægmund) in the late

ninth century, ibid., p. 38.

9

Bjork & Obermeier, p. 27; there is also Unfer∂, whose name Robert Fulk dates to being a form

preserved from prior to 700 CE, R.D. Fulk, ‘Unferth and his Name’, Modern Philology, v. 85:2. Nov.

1987, p. 121-2.

10

However, it is confined to Scribe B, who has a marked preference for using the -io- spelling, more

than twenty times more likely to use it than Scribe A who prefers the -eo- spelling – this may point to

Scribe B having a preference for an Anglo-Scandinavian dialect; but Judith, also transcribed by Scribe

B contains no such -io- spellings, though this may be due to the large portion of Judith which has been

7

In Kiernan’s controversial study of Beowulf, one of his major points was that

Scribe B was in fact the author of Beowulf as it stands, who melded “two distinct

poems ... combined for the first time in our extant MS.”

11

This long-outdated theory

has been proven to be false, notably by Janet Bately, who has shown that the use of

the conjunction siþþan is consistent in its syntactical positioning to a degree that

cannot warrant multiple authorship of the poem.

12

This thesis hinges on a number of a priori assumptions, about the author and

the audience of Beowulf, and therefore about the text. That there are some, but not a

great number of Nordicisms in the poem, and only two possible Old Norse loan-

words, against the late, ‘classical’ West Saxon of the poem, and the Old English

metre, means Beowulf can only be an Old English product. Christianity is ever-

present in the poem in a subtle way; God is continually praised, invoked and thanked

by the ‘narrator’ and the characters of the poem, and the word god itself is by far the

most common one used of God, occurring in over a third of all the references to God,

as almost frequently as the three next most popular by-names, metod, wealdend and

dryhten put together. Christianity brought Latin literacy to heathen Anglo-Saxon

England, but it did not oust orality;

13

instead the two remained the accepted modes of

information communication along side one another, as the vocabulary of literacy may

indicate,

14

alongside the example of Aldhelm who apparently mastered the art of

composition in both oral and written registers.

15

Thus Beowulf is a product of an

Anglo-Saxon, Christian, elite, well-versed in both the oral and literate modes of their

culture.

lost; Kevin Kiernan, Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript; University of Michigan Press, 1996, xxvi;

Peter J. Lucas, ‘The Place of Judith in the Beowulf-Manuscript’, The Review of English Studies, v. 41,

new series, no. 164, 1990, p. 473-4. 9.

11

Kiernan, 1996, p. 171.

12

Janet Bately, ‘Linguistic Evidence as a Guide to the Authorship of Old English Verse: A

Reappraisal, with Special Reference to Beowulf’, Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England,

(ed.) Michael Lapidge & Helmut Gnuess; Cambridge University Press, 1985, p. 421-2, 431.

13

Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, Visible Song: Transitional Literacy in Old English Verse; Cambridge

University Press, 1990, p. 9-11. 77.

14

Christine Fell, ‘Introduction to Anglo-Saxon Letters and Letter-Writers’, Lastworda Betst, (eds.)

Carole Hough & Kathryn A. Lowe; Shaun Tyas, 2002, p. 282, 284-6.

15

O’Brien O’Keeffe, p. 8.

8

C

HAPTER

O

NE

:

T

HE

H

ISTORICAL

C

ONTEXT OF

B

EOWULF

In any examination of the origins of Beowulf, the first consideration must be to

construct the broadest possible borders within which it could have been created, and

for this the terminus post quem must be provided by the events, episodes and

characters in Beowulf that can be verified in historical sources outside of the poem.

The other limit for the date of Beowulf, the terminus ante quem, is of course the date

of the manuscript itself, the only copy of which is contained within the early eleventh

century Nowell Codex; a composite manuscript containing three prose texts – an

acephalous Passion of St. Christopher, an illustrated Wonders of the East; and

Alexander’s Letter to Aristotle – and two verse texts – Beowulf and a fragmentary

Judith; itself bound with the unrelated twelfth century Southwell Codex at an

unknown later date into the manuscript B.L. Cotton Vitellius A XV.

THE DATE OF THE MANUSCRIPT:

The Nowell Codex was written in two different handwriting styles that each

offer separate date-ranges for their usage: Scribe A used a variation of early English

Vernacular minuscule, while Scribe B wrote in late Anglo-Saxon Square minuscule.

The latter script had its origins in the early tenth century, which, by the second

quarter, had superseded earlier styles of Insular minuscule, remaining in favour for

roughly fifty years.

16

Imported Caroline minuscule was first used in England for the

transcription of Latin texts from the middle of the tenth century, and by the end of its

last quarter, it had effectively replaced Square minuscule for that purpose, “no

specimen of [which] is datable later than ... after AD 1000”.

17

English Vernacular

minuscule (an Insular script strongly influenced by Caroline minuscule), whose

origins are in the ‘small print’ of the dual-language charters from the last decades of

the tenth century,

18

is conversely found no earlier than the first decade of the eleventh

century.

19

This provides a remarkably slender window of the years around the turn of

16

David N. Dumville, ‘Beowulf come lately: Some Notes on the Paleography of the Nowell Codex’,

Archiv für das Studium der neuren Sprachen und Literaturen, v. 225:1, 1988, p. 51-2.

17

ibid., p. 52-4.

18

ibid., p. 53.

19

ibid., p. 54.

9

the millennium within which the Nowell Codex may be placed. Moreover, the fact

that Scribe B’s portion sequentially and continuously follows Scribe A’s work,

support the conclusion that the Nowell Codex is “a product of the quarter-century

interval [centred on] the turn of the millennium.”

20

The other application of paleography to the dating of Beowulf, recently

championed by Michael Lapidge, examines the type of errors made by the scribes

with a view to postulating the script style of the exemplar. Concentrating on the

confusion of five sets of letter-forms (a/u, r/n, p/þ, c/t and d/ð) Lapidge concludes that

the exemplar was written in a script unfamiliar to the scribes.

21

To one unfamiliar

with Cursive, or Current minuscule, the open ‘a’, was virtually indistinguishable from

an ‘u’ and a confusion between ‘et’ and ‘ec’ ligatures, both point to a cursive style

script;

22

but, since the ‘r’s’ and ‘n’s’ are also confused, the exemplar cannot have

been entirely written in Cursive or Current minuscule.

23

The confusion of the runic þ

with ‘p’ seems to be universal in the copying all Anglo-Saxon scripts.

24

Concerning

the last letter-set, however, Lapidge dates the beginning of the process of the

consistent application of ð “to distinguish the interdental fricative from the aveolar

stop” (‘d’) to the second half of the eighth century, thus dating the Beowulf exemplar

prior to the mid eighth century.

25

Yet it is actually very clear from the examples

chosen for his article that the forms ‘d’ and ð are quite impossible to confuse in

Anglo-Saxon Set minuscule (the script he proposes the exemplar to have been written

in), and thus he fails in his purpose of using ‘literal’ scribal errors to theorise a date

for the exemplar of the Nowell Codex. Furthermore, in his desire to date the

exemplar to the early eighth century, he does not dwell on the fact that features of Set

minuscule and Cursive/Current can be found in datable texts up to the early years of

the tenth century.

26

This semi-formal or informal script, which was designed for

speed and not for clarity, peppered with contractions and abbreviations, was used for

“when scholars wrote for their own purposes ... and, so long as they themselves could

20

Francis Leneghan, ‘Making Sense of Ker’s Dates: The Origins of Beowulf and the Paleographers’,

Proceedings of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies Postgraduate Conference, 1, 2005, p.

7.

21

Michael Lapidge, ‘The archetype of Beowulf’, Anglo-Saxon England, v. 29, 2000, p. 7.

22

Lapidge, 2000, p. 17-9, 27-8.

23

ibid., p. 22-3.

24

Leneghan, p. 4.

25

Lapidge, p. 34.

26

ibid., p. 34-5, n. 86.

10

read what they had written, were not greatly concerned with legibility.”

27

It seems

then, that the exemplar of Beowulf (perhaps even the entire Nowell Codex) was

essentially written in an Anglo-Saxon shorthand – though one not influenced by

Caroline minuscule. Thus the conclusion of the paleographic evidence is that the

exemplar could have been written at any time after c.700 CE, but before the tenth

century got underway.

Some metrical theories have also been used to support an early eighth century

date for the exemplar, as with Kuhn’s laws; which, governing the position of half-

lines in poetry and therefore the order in which the sense of a passage was related to

the audience, “preserved archaic features of primitive Germanic after those features

had more or less disappeared from the language of everyday speech”

28

– a

phenomenon which whose end-point be dated to no later than the mid eighth century.

But this law may conversely be used to support the existence of a ‘dual literary

register’, since the lexicons of poetry and prose appear to have been governed by two

separate sets of rules throughout the Anglo-Saxon period. Another metrical test uses

Kaluza’s law, which “asserts that ... short endings are prone to metrical resolution,

while...long endings resist resolution;”

29

therefore a poem’s strong adherence to this

law suggests that it was composed prior to the “shortening of long vowels in

unstressed syllables.”

30

The processes behind both laws had already concluded by the

end of the first quarter of the eighth century.

31

Robert Fulk and Seiichi Suzuki have

both used Kaluza’s law to date the composition of Beowulf (if geographically located

in ‘Southumbria’) prior to 725 CE. However, in Bellender Hutcheson’s application of

Kaluza’s law to poems datable to the tenth century, he found that in a number of

instances “the late poetry actually adheres to Kaluza’s law better than Beowulf,”

32

and

since the basis of the law cannot be applied to the linguistic conditions present in the

tenth century, he concludes that Old English poetry preserved the integrity of the

ancient form of the traditional oral-formulaic units, to a very high degree.

33

Beowulf

27

ibid., p. 16-7.

28

Calvin B. Kendall, ‘The Metrical Grammar of Beowulf: Displacement’, Speculum, v. 58:1, 1983, p.

5.

29

B.R., Hutcheson, ‘Kaluza’s Law, The Dating of Beowulf, and the Old English Poetic Tradition’,

Journal of English and Germanic Philology, v. 103, 2004, p. 297.

30

(quoting Suzuki) ibid, p. 298.

31

ibid., p. 297.

32

ibid., p. 309.

33

ibid., p. 318-9.

11

therefore, “can either be very early, or heavily influenced by an oral-formulaic

tradition, or both, but it cannot be neither.”

34

Finally, the spelling preferences of the poet may provide some support to a

late date of composition since, on the one hand some words, such as hoe whose form

“does not occur in prose until the reign of Edgar in the late tenth century, and is never

found in verse,”

35

and the occasional use of the late case-ending –an for –um, may be

found in the poem;

36

while on the other, no very early forms of words may be

identified.

37

However, this is more likely to indicate the spelling norms at the time of

the manuscript’s transcription c. 1000 CE. Other aspects of the spelling that are likely

to be genuine indications of a late date, is the fact that where the poet was able to, he

did not use the early genitive plural which contains an ‘i’ in the case ending.

38

SCANDINAVIAN INFLUENCES:

It is to the poet’s mode of expression and turn of phrase, illustrated by the

prevalence of litotes and the overall restrained tone of the poem, as well as his

frequent use mod and its compounds, which indicate that the poem’s intended

audience is an elite Anglo-Saxon one.

39

But, as shown above, Beowulf is likely to

have originated (in the Nowell Codex version) in the first decades of the tenth

century, a date traditionally rejected due to the idea that an Anglo-Saxon poem

concerned with heroic Danes could not have been in circulation at a time when Danes

were engaged in the harrying and settlement of England.

40

And yet, the manuscript

itself was transcribed in such a period of renewed Scandinavian aggression in the

reign of Æthelred Unræd. Among the West Saxon kings of the ninth to eleventh

34

ibid., p. 320.

35

Roberta Frank, ‘Beowulf and Sutton: The Odd Couple’, The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England:

Basic Readings, (ed.) Catherine E. Karkov; Garland Publishing, 1999, p. 328.

36

In ahlæcan, l. 646b, Alfred Bammesberger, ‘Eight Notes on the Beowulf Text’, Inside Old English:

Essays in Honour of Bruce Mitchell, (ed.) John Walmsey, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, p. 29.

37

Wundini is no longer considered a genuinely early form, Kiernan, ’96, p. 31-2.

38

Stanley, p. 209; R.D. Fulk, A History of Old English Meter; University of Pennsylvania Press,

Philadelphia, 1992, §279-81, p. 243-5.

39

Roberta Frank, ‘The Incomparable Wryness of Old English Poetry’, Inside Old English: Essays in

Honur of Bruce Mitchell, (ed.) John Walmsey, Blackwell Publishing, 2006, p. 63-5; mod is a shorthand

expression for something like ‘inner aristocratic warrior nature’ that is found all throughout Beowulf to

denote the thought patterns and actions of the elite person, John Highfield, ‘Mod in the Old English

‘Secular’ Poetry: An indicator of aristocratic class, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of

Manchester, v. 79:3, 1997, p. 85-8.

40

This theory may be swiftly dismissed simply by acknowledging that the portrayal of the Danes in

Beowulf was not heroic, since they were unable to prevent the depredations of Grendel, and

furthermore were engaged, at least sometimes, in the heathen worship of idols.

12

centuries alone, the contacts with Scandianvians and Anglo-Scandinavians can be

seen to be both strong and deep.

Æthelred Unræd, king of England at the time of the manuscript’s production,

spent the majority of his reign staving off the attacks of the Danes under chiefly led

by Swein Forkbeard. And yet in the middle of his reign, he contracted his second

marriage to Emma, daughter of Richard I of Normandy, a family whose sympathies to

those same Vikings harrying England were widely known.

41

The pair had been

married for only six months when Æthelred ordered the massacre of ‘foreign’ Danes

in England on St. Brice’s Day, but it was during the same winter of 1002, that he

“enrolled northern warlords and their followers in his military forces” and patronised

the Icelandic court poet Gunnlaugr Ormstunga.

42

Æthelred’s father, Edgar the

Peaceable, had himself been raised in Æthelstan the ‘Half-King’s’ household

(ealdorman of Danish Mercia and East Anglia),

43

and was said to have “loved bad

foreign habits, and brought heathen customs too fast into this land.”

44

Edgar’s uncle,

king Æthelstan was foster-father to Harald Fairhair of Norway’s son, Haakon the

Good, and it is possible that when the latter returned to take the throne of Norway in

934 CE, he brought with him the first Anglo-Saxon (or perhaps Anglo-Scandinavian)

missionaries to that country.

45

The court of Æthelstan’s grandfather, Alfred, was

noted for the “Franks, Frisians, Gauls, Vikings, Welshmen, Irishmen and Bretons

[who] subjected themselves willingly to his lordship, nobles and commoners alike.”

46

Frisians were involved in Alfred’s naval attacks on the Danes, three of them

mentioned by name in the Chronicle,

47

and of course the Old English Orosius was

translated at Alfred’s court, incorporating the testimony of Ohthere the Norwegian

and Wulfstan the Frisian.

48

41

Mike Ashley, The Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens; Carroll & Graf Publishers Inc., New

York, 1998, p. 483.

42

M.K. Lawson, Cnut: The Danes in England in the Early Eleventh Century; Longman, 1993, p. 6.

43

Ashley, p. 478.

44

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, ( trans., ed.) Michael Swanton; Phoenix Press, 2003, under year 959

CE; Alexander Callander Murray, ‘Beowulf, the Danish Invasions, and Royal Genealogy’, The Dating

of Beowulf, (ed.) Colin Chase; University of Toronto Press, 1981, p. 110.

45

Fridjov Birkeli, ‘The Earliest Missionary Activities from England to Norway’, Nottingham Medieval

Studies, v. 15, 1971, passim.

46

Asser, Life of King Alfred, (trans.) Simon Keynes & Michael Lapidge, Penguin Books, 2004, §76, p.

91.

47

Wulfheard, Æbbe and Æthelhere; Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, under year 897 CE.

48

The Old English Orosius, (ed.) Janet Bately; Oxford University Press, 1980; lxxi-ii.

13

“By the second quarter of the tenth century there was clearly a well-

established Anglo-Scandinavian society in the Danelaw,”

49

but one that was

comprised of migrant populations of Scandinavian elites whose numbers were more

likely to have been in the hundreds rather than the thousands,

50

and yet who were able

to lay such a lasting impression on the northern and eastern regions in which they had

settled that it was felt for centuries after their total integration into English society had

been accomplished. With regard to the linguistic repercussions of the permanent

settlements of Scandinavians in England from the last quarter of the ninth century,

Old Norse and Old English speakers in the tenth century were thought to have

developed a sort of Anglo-Scandinavian Creole in the north of England;

51

apparent in

the use of dialect words in Olaf’s speech in the Battle of Maldon;

52

and Wulfstan’s

sermons, which, when Bishop of York, included more Scandinavian loan-words than

his speeches and sermons dating from his tenure as Bishop of London.

53

Old English

personal names may have been given to some of the migrants,

54

while elsewhere

Anglo-Saxon families may have introduced Old Norse names into their family ‘pool’,

probably through intermarriage.

55

Roberta Frank has identified a number of individual words which, when

viewed in the context of their Old Norse cognates’ contexts, bring a fuller meaning to

their use in Beowulf such as: lofgeornost which in Old English prose carries a

pejorative tone, ‘over-eager for praise’, while in Old Norse poetry it means ‘most

eager for praise’;

56

dollic, ‘foolish’ in prose contexts, and ‘bold’ in poetic;

57

mere and

sund play on their dual prosaic and poetic meanings (‘pool’ and ‘swimming’ versus

‘sea’ and ‘sea/sound’ respectively) in such a way that the composer of Beowulf firmly

49

Julian D. Richards, Viking Age England; Tempus, 2004, p. 41.

50

D.M. Hadley, ‘Viking and native: re-thinking identity in the Danelaw’, Early Medieval Europe, v.

11:1, 2002, p. 46-8.

51

Hadley, p. 55.

52

Robert E. Bjork, ‘Scandinavian Relations’, A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature, (eds.) Phillip

Pulsiano & Elaine Trehearne, Blackwell Publishers, 2001, p. 392.

53

Matthew Townend, ‘Viking Age England as a Bilingual Society’, Cultures in Contact: Scandinavian

Settlement in England in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries, (eds.) Dawn M. Hadley & Julian D. Richards;

Brepols, 2000, p. 92-3.

54

For example in the continued use of ‘Æthelstan’ in East Anglia from pre-Viking times, to Guthrum’s

adoption of it as his baptismal name, to Æthelstan ‘half-king’, the lord of East Anglia in 930’s.

55

Hadley, p. 59-60.

56

Roberta Frank, ‘Did Anglo-Saxon Audiences have a Skaldic Tooth?’, Scandinavian Studies, v. 59,

1987, p. 344-5.

57

ibid., loc. cit.

14

shows his own skaldic capabilities.

58

Elsewhere, the poet seems to falter, as seen in

his lack of confidence when using difficult kennings which he then explains more

plainly not more than a few lines later; however, this may in fact be a fault, not of the

original composer, but of the scribe(s) who found the meanings of the kennings hard

to fathom.

59

Another such word, whose context in Beowulf lies in an Anglo-

Scandinavian millieu, is eorl, which in the earliest Old English texts denotes a man of

the highest social rank second only to the king or prince of that region. By the late

ninth century, though, this meaning had been replaced in most contexts by the words

ealdorman and þegn, and it was not until later, in the tenth century, that the earlier

sense of eorl was revived through contacts with the Anglo-Scandinavian communities

who used the Old Norse jarl in a similar sense of ‘leading man’ or ‘ruler’.

60

This is

the Beowulfian usage, and since þegn is just as common throughout the text as eorl, it

may point to a post-Alfredian period of composition (rather than deliberate archaising

on the part of the poet) since the two words only co-existed in Old English through

Scandinavian influence.

Other words came into Old English through actual loans from the Old Norse;

however, and though no one seems to have made a case for any such loan-words in

Beowulf as yet, there are two words that deserve reappraisal as possible loan-words.

The first is eoton, an Old English word for 'giant’ that is semantically identical with

ent.

61

The latter is a relatively common word which is used in both prose and poetry,

but eoton’s only appearances in the Old English Corpus are in Beowulf at least seven

times, and twice in early eleventh century glosses for edax, ‘rapacious, glutton,

voracious’.

62

Such a relatively high frequency in Beowulf, but nowhere else, suggests

that this is an anglicisation of one of the Old Norse words for giant, jötunn (pl.

jötnar), which happens to be similar to a pre-existing Old English word for the same

58

Roberta Frank, “Mere’ and ‘Sund’: Two Sea-Changes in Beowulf, Modes of Interpretation in Old

English Literature: Essays in Honour of Stanley B. Greenfield, (eds.) Phyllis Russ Brown et al;

University of Toronto Press, 1986, p. 156-161.

59

Frank, 1987, p. 343.

60

H.R. Loyn, ‘Kings, Gesiths and Thegns’, The Age of Sutton Hoo: The Seventh Century in North-

Western Europe, (ed.) M.O.H. Carver, The Boydell Press, 1992, p. 77; Roberta Frank, ‘Skaldic Verse

and the Date of Beowulf’, The Dating of Beowulf, (ed.) Colin Chase; University of Toronto Press,

1981, p. 124.

61

See Chapter Three.

62

Eoton – l. 112, 421, 761, 883, eotonweard – l. 668, eotonisc – l. 1558, 2979, are all definite; here it is

unclear if eoton refers to ‘giant’ or ‘Jute’ – l. 902, 1072, 1088, 1141, 1145; both glosses occur in the

Cotton Cleopatra A.III in the form eotend.

15

creature.

63

Furthermore, since it is not an isolated occurrence in the text, it strengthens

the theory of Scandinavian influence on the poem’s composition. The second word,

hold, has an Old English homophone meaning ‘loyal, faithful’, but on one occasion in

Beowulf, it is better translated by the Old Norse meaning of a ‘vassal’ or ‘free man,

land-holder, noble one’, which Mary Serjeantson noted, in 1935, “may be ascribed to

the period before 1016 [CE].”

64

The höldr in Old Norse, was of a rank just below the

jarl in the Anglo-Scandinavian usage.

65

Roy Liuzza, it may be noted, does not even

translate the word holdra in the following, instead dovetailing its Old English

meaning into the ‘dear (and faithful) troop’, when: ahte ic holdra þy læs deorre

duguðe þe þa deað fornam, ‘then I had less land-holders in the noble troop, when

death seized them from me’ (l. 487b-8).

The words used in Beowulf to denote Scandinavia itself, Scedenig (l.1686) and

Scedeland (l.19), do not appear to be current in the tenth century. Instead, Sconeg

66

and Skáney,

67

were both used to refer to the region of Skåne in the tenth century, but

Eric Stanley provides the timely reminder that “[one] cannot date the obsolescence of

Scedenig.”

68

In addition, Frank has noted that Scedenig and Scedelandum properly,

and accurate philologically, denote Scandza (as Scandinavia as a whole was termed

by many a medieval author), rather than Skåne; which usage makes more contextual

sense in Beowulf than if Skåne alone were indicated.

69

Carol Clover’s delineation of the difference between skaldic and eddic poetry

is that the former “is emphatically non-anonymous,” as the poet will regularly place

himself personally into the role of narrator – showing his presence in the events

related, or his opinions through asides – rather than “anonymously narrating

traditional tales in the impersonal epic manner.”

70

This technique may also be

discerned in Old English poetry, as, among others, in Beowulf itself. Likewise, the

63

Probably because they are descended from the same Proto-Germanic root. The same can be seen in

the other direction, since there is place-name in Iceland, Enta, denoting a volcanic crater, (whose

neighbouring crater is named Katla, ‘witch, she-troll’), that is considered to be a ‘definite loan-word

from the Old English’; Stefán Einarsson, ‘Old English ent: Icelandic enta’, Modern Language Notes, v.

67:8, Dec. 1952, p. 554-5.

64

Mary S. Serjeantson, A History of Foreign Words in English; Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962, p. 64-

5.

65

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, p. 94, n. 7; term occurs under the years 905, 911, 921.

66

Its only occurrence precisely datable to c. 890 CE [Bately, 1980, xcii-iii].

67

c. 1000 CE – Frank, 1981, p. 124-5, n. 8.

68

Stanley, 1981, p. 207.

69

Frank, 1981, p. 125, n. 8.

70

Carol J. Clover, ‘Skaldic Sensibility’, Archiv för Nordisk Filologi, v. 93, 1978, p. 63-4.

16

trading of insults between Beowulf and the coastguard, Beowulf and Wulfgar the

Wendel prince, and most famously, Beowulf and Unferth, has been shown to be

directly related to the genre of flyting in its structure of claim, defense and

counterclaim, and content of “boasts and insults in varying proportions with a

admixture of threats, curses or vows.”

71

In these verbal combats, Beowulf is as

successful in defeating all of his challengers as he is in his physical contests in

Denmark, a trait which would be recognised and relished by an audience educated in

an Old Norse literary milieu.

72

On a larger scale, excerpts from a number of eddic and skaldic poems have

been found to be directly related to passages in Beowulf and other Old English

poems.

73

Robert Fulk has uncovered an analogue to the stories of Scyld and Scef in

the English tradition, in the tale of Bergelmir in Vafþrúðnismál, which may also

further illuminate William of Malmesbury’s account of the monks of Abindgon who

set a sheaf of grain (OE yelm) on a shield floating downriver ostensibly to demarcate

a boundary line.

74

Another example of textual echoes may be found in the

descriptions of Heorot throughout Beowulf, comparable to the descriptions of

otherworldly halls found in Old Norse literature in general, but specifically to the hall

in Hindar Fell, the ‘rocky hill of the hind’ (note that Heorot is the ‘stag hall’) in

Fáfnismál. There the description where “a high hall stands on Hindar Fell, all

enfolded it is by fire without, cunning craftsmen this castle built, of the glistening

gold of rivers”, may be paralleled in that of Heorot which is fyrbendum fæst ... innan

ond utan irenbendum searoþoncum besmiþod, “fast in its forged bands ... inside and

out with iron bonds cunningly crafted” (l. 722a ... 774-5a).

75

Finally, an exact

correspondence may be argued between the portrayal of King Alfred in Egil's saga

who was deemed the first 'true' ruler of all England and Englishmen since “had

deprived all the tributary kings of their rank and power; those who had been kings or

princes before were now titled earls” with Scyld Scefing in Beowulf, who was the

71

Carol J. Clover, ‘The Germanic Context of the Unferþ Episode’, Speculum, v.55:3, 1980, p. 452-3.

72

ibid., p. 464-5.

73

For quick overview of others, see Bjork, 2001, p. 391ff.

74

Relying on the Old English stories mistakenly attributing the tales of the son (Beow) to the

father/grandfather (a not uncommon mistake), and the philological interpretation of Bergelmir as

originally a barley deity, comparative to the identification of his ‘father’ Aurgelmir with the ‘ear’ or the

‘spike’ of the barley (ruðgelmir – perhaps ‘mighty bundle (of grain)’?), and the common basis of the

tale that this barley figure was set adrift in a grain-box; R.D. Fulk, ‘An Eddic Analogue to the Scyld

Scefing Story’, The Review of English Studies, new series, v. 40, no. 159, Aug. 1989, passim.

75

Fáfnismál, st. 42, p. 231; The Poetic Edda, (trans.) Lee M. Hollander; University of Texas Press,

Austin, 2

nd

ed., 2004.

17

‘first’ king of the Danes (as presented by the poet) since he had “refused mead-

benches to many nations, struck terror into the earls” (l. 4-6).

76

HISTORICAL CONCORDANCES:

The original poet of Beowulf then, was well acquainted with Scandinavian

modes of expression, so much so that his own style is, in parts, comparable in

technique, vocabulary and stories common to the skaldic and eddic traditions which

are apparent from the end of the ninth century, but which most likely stretches back to

the Volkerwanderung whence much of the material for the heroic stories originated.

The characters and tribal groups referred to in Beowulf may also be traced to having

originated in this period; however, these references do not correspond to any single

historical period, but are a literary backdrop created to invoke a generic past time that

juxtaposes with the present time of the narration of Beowulf. Since all of those

included as part of this ‘scenery’ must necessarily be in the past at the time of

composition, a terminus a quo for Beowulf may then be placed at the point of the

latest entity. The only problem with this approach is that almost all of these figures,

who occur only once or twice in the poem, cannot be located in other literature; or if

they can, it is not within the context of a historical event or datable document.

The most famous exception to this is the figure of Hygelac in Beowulf whom

Nicholas Gruntvig, in 1817, first equated with the historical figure of Chlochilaich,

whose death c. 530 CE was recorded by Gregory of Tours (c. 580’s CE) while he was

on his fatal raid into “Frisian territory” (l. 2357b).

77

Since realistic time-keeping was

not the intention of Beowulf’s poet, it is uncertain how much could have elapsed

between this and Beowulf’s own death, but the longest possible gap was a little under

fifty years.

78

Since Hygelac’s raid is the earliest historically verifiable event related in

the poem, it has been understood that the terminus a quo must be c. 530-80 CE. But

this conclusion has then been used to assert that all of the action (with the exception

of the ‘Finnsburg Episode’ which is presented as a past within the past) occurred

within this historical time-frame, and yet there is nothing to support such a belief.

76

Egil’s Saga, (trans.) Bernard Scudder, (ed.) Svanhildur Óskarsdóttir; Penguin Books, 2004, ch. 51, p.

90; Beowulf interpretation from Bammesberger, p. 20.

77

Gregory of Tours, The History of the Franks, (trans.) Lewis Thorpe; Penguin Books, 1974, 3:3, p.

163-4.

78

Beowulf returned to Geatland while Hygelac’s was still alive, with the necklace that was a present

from Wealhþeow; which was the necklace Hygelac himself wore on the aforementioned fatal raid.

18

Even archaeological evidence, which can be vague at the best of times in the absence

of precisely datable objects,

79

cannot agree with the dating of the action in Beowulf to

the sixth century, as shown by the descriptions of the ships in the poem which clearly

have the option of sails – an innovation which did not reach Northern Europe until the

close of the seventh century.

80

It may be pertinent to note here in the context of

archaeology, that while innovation may be dated, obsolescence cannot.

The character of Ongenþeow has two philologically exact correspondences in

the historical figures of a Danish king Ongendus,

81

who flourished c. 700 CE, and an

Angandeo, brother to the Danish king Hemming, whose solitary reference is found in

the Annales Regni Francorum as a signatory to Charlemagne’s peace treaty with the

Danes of 811 CE.

82

There is also the reference in Widsið to an “Ongenþeow [who

ruled] the Swedes” (l. 31b), but this can remain no more than a teaser since Widsið

can in now way be considered a historically accurate source. Ongendus appears in

Alcuin’s Life of St. Willibrord described as “a man more savage than any wild beast

and harder than stone,”

83

one that accords well the characterisation of Ongenþeow in

Beowulf.

The tribal name, Scyldingas, used throughout Beowulf in reference to the

Danes, arguably provides as firm a terminus a quo from the composition of the poem

as the concordance of Hygelac and Chlochilaich does. The earliest mention of

Scyldingas comes c. 950 CE in the Historia de Sancto Cuthberti naming the sons of

Ragnarr Loðbrók, Ívarr the Boneless and Halfdan the Black, as leaders of the

Scaldingi;

84

linguistically, this form of the name could not have been borrowed from

the Old Norse after the ninth century.

85

In the Historia, the Scaldingi refer to the

combined Danish forces of Ívarr and Olaf the White at the battle of York in 867, and

the same army led by Halfdan after Ívarr’s death. These ‘Scyldingas’, who likely had

their origins in the generation before Ragnarr and Olaf, in the chaos of the civil wars

79

Even in the presence of datable objects like coins, the interpretation is not assured, as with the case

of Mound 1 from Sutton Hoo, which may be dated to that of the latest of the coins, or alternatively, it

has been seen as a deliberate collection of rare coins which may have been collected at any time.

80

l. 217-8, does not explicitly state there are sails, but l. 1903b-13, does, and likewise Scyld’s ship has

a mast which indicates sails, l. 35b-6a; Arne Emil Christensen, ‘Scandinavian Ships from earliest times

to the Vikings’, A History of Seafaring based on underwater archaeology, (ed.) George F. Bass;

Walker & Co. New York, 1972, p. 165.

81

In Beowulf, ð and þ seem to be interchangeable, and so are ð and d as seen in Hreþel/Hreðel/Hrædel.

82

Annales Regni Francorum, [under year] 811, http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/annalesregni

francorum.html

83

Alcuin, The Life of St. Willibrord, p. 9; [in] The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany, (trans., ed.)

C.H. Talbot; Sheed & Ward Ltd., London, 1981.

84

Leneghan, p. 10.

85

Frank, 1981, p. 127, n. 17.

19

of Denmark that lasted c. 810-40 CE, were more likely to have originally been the

‘Men of the Shield’ (a term comparable to the “Rondingas” in Widsið), rather than

‘the descendants of Scyld’.

86

This latter idea apparently only emerged in the second

datable period of the name’s use during the first half of the eleventh century by Old

Norse skalds who used it to refer specifically to Cnut the Great, St. Olaf Haraldsson

and Magnus Olafsson the Good.

87

The usage of Scyldingas in Beowulf,

chronologically falls between these two periods and is also a combination of the

earlier application to incorporate the followers of the ‘descendant of Scyld’, and the

later preference for using it to refer only to that royal descendant himself. Where

Scyld fits into the Anglo-Saxon tradition may be briefly contextualised by glancing at

the ever-expanding genealogy of the kings of Wessex.

The purpose of the royal genealogy in late Anglo-Saxon England, was

arguably to assert the right of rule over a people through the citation of a common,

heroic, ancestor with the leading, or princely families of that region. The core of a

royal genealogy generally would go no farther back in time than three of four

generations from the present, as is the case with the genealogies provided in

Beowulf.

88

Such a core would have existed for the early West Saxon kings, but as

their spheres of influence grew, “those who calculat[ed] the reigns of kings,”

89

fabricated a common ancestry between the West Saxons and their subject peoples.

90

Scyld was likely to be one such adopted ancestor who could have been a combination,

in the West Saxon genealogy, of a hero claimed by some of the Scandinavian

Scaldingi in England, and a legendary “boat-borne hero ... originally fostered by the

Wuffings,” the indigenous East Anglian royal line.

91

Sam Newton has shown that

these Wuffings most likely laid claim in their own genealogy to the characters of

Hroðmund and Wealþeow, who of course are members of the Scyldingas in Beowulf,

and moreover, that since “there may have been dynastic kinship between East Anglia

and Wessex during the second quarter of the ninth century ... [this provided] a context

86

ibid., p. 127.

87

Leneghan, p. 10.

88

As is the case with the genealogies Bede provides for Hengest, and Æthelberht, and it may be noted

that even though Hengest occupies the fourth place back for Æthelberht, Bede does not link the two in

the way that the Chronicle tends to; Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, (trans.) Leo

Shirley-Price, (revised) R.E. Latham; Penguin Books, 1990, 1:15, p. 63, 2:5, p. 112; Kenneth Sisam,

‘Anglo-Saxon Royal Genealogies’, Proceedings of the British Academy, v. 39, 1953, p. 322-3, 329.

89

Bede, 3:1 p. 144.

90

David N. Dumville, ‘Kingship, Genealogies and Regnal Lists’, Early Medieval Kingship, (eds.) P.H.

Sawyer & I.N. Wood; School of History, University of Leeds, 1977, p. 81.

91

Newton, p. 142.

20

for the West Saxon acquisition of Wuffing ancestral traditions.”

92

The theoretical

supremacy of the West Saxon kings was a fait accompli by the opening years of the

tenth century,

93

having assimilated the illustrious (and distant) ancestors of all the

people now subject to them; though how far this was applied in reality is another

matter all together. With regard to Beowulf, the Anglo-Scandinavian milieu by which

it was greatly influenced – though not so much so that it may be seen as an Anglo-

Scandinavian product – may perhaps tentatively be placed within the Danish kingdom

of East Anglia, that was demarcated c. 890 CE in the treaty between Alfred and

Guthrum, but which remained autonomous for less than thirty years, when, after some

years of upheaval, Edward the Elder permanently gained control over the region in

917 CE.

94

*

*

*

The majority of authors, in any period of history, when they are writing about

the past, are unable to avoid presenting their material “in the social idiom of [their]

own day, creating an atmosphere and a way of life that would have been familiar to

[their] audience.”

95

Some authors are better able to dissociate from their cultural

surroundings than others, but it can be hard to tell whether or not this indicates an

objective transmission of an old story over time, or a conscious re-working of the

material in an archaistic fashion. As noted by Hutcheson, Beowulf is unlikely to be the

work of an archaist on metrical grounds as “there is nothing in the surface phonology

[of traditional poetry] that indicates that Kaluza’s law is operating, [and a] tenth

century poet would have had no way of knowing which verses were archaic and

which were not.”

96

This is clear evidence for the ability of tenth century poets to

compose new material in the style of ancient poetry which does not necessitate a

written form from the eighth century, but simply the barely-changed Old English

traditions of oral composition into the tenth century (and probably further). That the

exemplar from which the Nowell Codex was copied was itself written in a scribal

shorthand, much like a modern-day stenographer’s shorthand, raises the possibly that

this was the original written copy of Beowulf transcribed during a performance. This

92

ibid. loc.cit.

93

Davis, p.127-9.

94

Ashley, p. 467.

95

Karl P. Wentersdorf, ‘Beowulf: The Paganism of Hrothgar’s Danes’, Studies in Philology,v. 78,

1981, p. 92.

96

Hutcheson, p. 319.

21

has been suggested by Paul Sorrell, among others, who notes that since more than one

version of events is related over the course of Beowulf,

97

and the relationship of the

storyline’s progression is in a “‘zigzag’ pattern of the oral method...an incremental

style that is very close to...the so-called ‘digressions’ in Beowulf,”

98

the form of the

poem as it stands is very close to an orally delivered original (from which the

exemplar is taken).

A scenario for the composition and transmission of the Nowell Codex Beowulf

may be presented in the ‘recording’ of a recital by one or more scribes, at some point

during the first quarter of the tenth century, somewhere in Anglo-Saxon England

sympathetic to the West Saxons. More precisely, a plausible point of origin for the

written poem lies in the late 910’s or early 920’s when Wessex was re-asserting itself

in the southern Danelaw, or even a little later in the reign of Æthelstan who was

sometimes styled Angelsaxonum Denorumque gloriosissimus rex.

99

It was then that

the mixed population of the ‘Danelaw’ were not viewed unfavourably in the Anglo-

Saxon Chronicle,

100

may have shifted the focus of their cultural milieu to Wessex,

101

away from the northern Danelaw which in was ruled by a series of heathen Dublin

Norse, who held onto it for the next thirty or so years.

102

97

Paul Sorrell, ‘Oral Poetry and the World of Beowulf’, Oral Tradition, v. 7:1, 1992, p. 37.

98

ibid., p. 41, also fig. 1, p. 44.

99

Murray, p. 109-10.

100

Both Danes and Englishmen work together to improve the fortifications of Nottingham; Anglo-

Saxon Chronicles, under year 922.

101

For instance in Lincolnshire; David Stocker & Paul Everson, ‘Five towns funerals: decoding

diversity in Danelaw stone sculpture, Vikings and the Danelaw, (eds.) James Graham-Campbell et al;

Oxbow Books, 2001, p. 241.

102

Every successive ruler of Danish Northumbria/York in the tenth century, was depicted in the West

Saxon sources as officially sponsored in baptism by a West Saxon king, though some delayed this act,

many later apostasised, and all were antagonistic towards Christianity; Ashley, p. 462-6.

22

C

HAPTER

T

WO

:

T

HE

S

OCIO

-R

ELIGIOUS

C

ONTEXT OF

B

EOWULF

Everything which modern scholarship knows about early medieval European

heathenism, has passed through the pens and perceptions of Christians – but all of the

archaeological evidence from the periods prior to Christian influence and adherence,

is mute without this literary context. In fact, very little has survived the early

medieval period, which can be proven to have been drawn from an actual eyewitness

account (or even a reliable firsthand report) of heathen practices,

103

most literary

references to heathenism being far-removed from their source in either time, or place,

or chain of communication – or all three at once. And even when the derivative,

fictive, and un-informed elements are stripped away from an account, the most which

the modern scholar may be provided with are descriptions of the external expressions

and manifestations of heathenism, since not even the most well-informed and intuitive

Christian recorder or complier could report the beliefs underlying the rituals

witnessed without having had them reported to him by their holders, or been one

himself at some stage.

Beowulf is no exception, since even though there are instances of heathen

activities and people in the poem, what they tell us about the nature of any heathenism

known to the Christian Anglo-Saxons is arguably less than what can be gathered from

the Old English penitential corpus.

104

However, the nature of the latter is more

concerned with heathen practices among the general population, than with what may

be termed the elite expressions of heathenism, such as those which the Beowulf poet

draws upon. Those are discussed here include the role of the heathen priest, the

maintenance of heathen temples, and the elaborate and expensive funerary rites,

which, without an aristocratic class to perpetuate them, would arguably not exist, or at

least be greatly altered in form. This discussion does not set out to resurrect the old

103

With some notable exceptions, eg; Ibn Fadlan’s account of the Rus funeral and the letters of

Sidonius Apollinaris.

104

Wentersdorf has shown through the use of excerpts from this and other sources, that in the eighth

century heathen practices were still of great concern to the Anglo-Saxon church – eg, in Egbert of

York’s penitential, c. 750 CE, specific aspects of the usual ‘idol-worship, divination, amulet wearing’

are given: eclipses are special times where by “outcries and charms” one can “defend” oneself,

Thursday and “the first day of January” is dedicated to Jovis, divination ma be done through “oracles

of the saints” and “whatever kind of writings”, while amulets may be of “grass or amber”, p. 102 – and

even of concern to Rome, who sent a stern decree in 787 CE to the Anglo-Saxon bishops to root out

such practices and practitioners as mentioned above, p. 102-3.

23

pagan-Christian debate; but instead hopes to quell it by showing that the poet displays

a knowledge of only the public expressions of heathenism, which themselves cannot

be seen outside of the context of Scandinavian influences, and thus shows himself to

be a product of a Christian society long accustomed to that state.

DATABLE ASPECTS OF CHRISTIANITY AND HEATHENISM IN BEOWULF:

Christian concepts are virtually undatable beyond their earliest point of their

inception; likewise individual texts, except through datable manuscript rescensions,

and even Christianity itself in Anglo-Saxon England, beyond the date of its official

introduction,

105

are both impossible to date. Within Beowulf in particular, specific

ideas such as the theme of the ‘soul-shooter’ from the Psalms and Ephesians,

106

and

texts including Gregory’s Moralia On Job

107

and Duodecim abusivas,

108

may be

shown to have a very pervasive influence throughout the poem; the problem in using

them to date Beowulf, lies in their ubiquity in Anglo-Saxon England. However, an

exception has been made in the case of the late tenth century Blickling Homily #17,

‘Dedication of St. Michael’s Church’, in which the description of hell has been

proven to be textually paralleled in the description of Grendel’s mere in Beowulf.

Both stem from the Visio St. Pauli (The ‘Apocalypse’ of St. Paul), one of the most

widespread and enduring texts in medieval western Christian eschatology;

109

and the

pre-eminent authority of its textual transmission, Theodore Silverstein, has shown that

neither text is dependent upon the other, but that both are derived from a ninth century

Anglo-Saxon rescension.

110

Not much more can be said of the datable aspects of

Christianity evident in Beowulf; while for the non-Christian elements, there is a single

105

The kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England were converted officially between 597 and 678 CE, but it is

erroneous to assume that there were no Christians in Britain prior to these events, since many Anglo-

Saxons arrived from the Continent (arguably a large portion of them only in the mid sixth century)

where Christianity was establishing itself among the Franks, and had been a part of the culture (in the

form of Arianism) of most of the Germanic tribes to have settled in the Roman Empire for at least a

century. And of course the Romano-British themselves were largely Christian at the time of the arrivals

of the Anglo-Saxons (and others), and many of them maintained their religion if the evidence of place-

names and the cults of SS Alban and Sixtus, as a minimum, are anything to go by.

106

Mark Atherton, ‘The Figure of the Archer in Beowulf and the Anglo-Saxon Psalter’, Neophilologus,

v. 77, 1993, p. 653.

107

Judson Boyce Allen, ‘God’s Society and Grendel’s Shoulder Joint: Gregory and the Poet of the

Beowulf’, Neophilologische Mitteilungen, v. 78:3, 1977, p. 239-40.

108

Particularly in the ninth abuse of the unjust king; Rob Meens, ‘Politics, mirrors of princes and the

Bible: sins, kings and the well-being of the realm’, Early Medieval Europe, v. 7, 1998, p. 350-1.

109

Second only the Apocalypse of St. John, or Revelation, and in many places and periods, the Visio

St. Pauli surpassed the latter in importance.

110

Frank, 1981, p. 138, n. 63.

24

reference to the activities of heathens,

111

when hwilum hie geheton æt hrærg trafum

wig weorþunga wordum bædon þæt him gastbona geoce gefremede wið þeodþreaum,

‘at times [the Danes] vowed at the temple-sanctuary of the being they worshipped,

prayed with words that for them the soul-slayer/spirit-slayer might be a help against

the people’s-misery’ (l.175-6a). Hrærg is invariably emended to hearg, which has a

wide semantic range of ‘temple, altar, sanctuary, idol’ – none of which refers to a

Christian place – while træf likewise is a word associated with places of

heathenism.

112

With reference to the cognate Old Norse hörgr, which is “a heathen

place of worship,”

113

Thomas Markey concludes that the Old English hearg was “a

learned translation of ‘heathen temple’ in Christian texts ... which in its pre-Christian

context would have referred to an (elevated) area in the open where pagan rites were

conducted.”

114

The only other piece of information which these lines yield is that the

being (wig

115

) to whom the Danes “offered worship in [their] pagan cult centres,”

116

is synonymous with the gastbona, who, as any Christian in Anglo-Saxon England

would have known, was the Devil himself.

117

It is then a natural progression for the

poet to state that the Danes were destined to burn forever in hell because of their

actions (l. 183b-6a).

On one occasion the poet refers to Beowulf’s Geats as heathens, when they

arrive back at the court of Hygelac and Hæreðes dohtor ... liðwæge bær hæðnum to

handa, “Hæreth’s daughter bore the cup to the heathens by her [own] hand”, (l.1981-

111

There is the possibility of a single reference in to divination in the poem, though not the traditionally

identified one at l. 204, which Christine Fell has shown to be a prosaic ‘wished him well’, as opposed

to the usual, ‘they cast lots’, or ‘scrutinised the omens’, ‘Paganism in Beowulf: A Semantic Fairy-Tale’,

Germania Latina II: Pagans and Christians, (eds.) T. Hofstra, et al ; Egbert Forsten, 1995, p. 30-3. It

is the ‘day-raven’ of l. 1801-3, which, if the adjective describing the raven is emended from blaca to

blota (according to Lapidge’s set of common substitutional scribal errors (c/t and a/o), the confusion

over whether it is ‘shining’ or ‘dark’ may be dispelled with it would then be - o† †æt hrefn blaca

heofones wynne bli∂heort bodode, ‘[all Heorot slept] until the hallowed raven foretold the joy of

heaven’, ie, that Heorot was now safe from attacks. This emendation alliterates better with the bodode

below, and would be an example of augury from the flight of birds.

112

TOE; Fell, 1995, p. 21-3.

113

That is either a naturally occurring outcrop of stones, or a man-made cairn or barrow in contrast to

the hof which was a man-made temple, associated with buildings and human habitation; C-V.

114

Thomas L. Markey, ‘Germanic Terms for Temple and Cult’, Studies for Einar Haugen: Presented

by Friends and Colleagues, (eds.) Evelyn Scherabon Firchow, et al; Mouton & Co., 1972, p. 368.

115

Wig/Weoh, means ‘idol, being, creature’; it is interesting that the related word wiga means ‘man,

warrior’, which if the wig here is in fact Grendel, accords well with his man/demon split character.

116

Fell, 1995, p. 23.

117

Paul Cavill, ‘Christianity and Theology in Beowulf’, The Christian Tradition in Anglo-Saxon

England: Approaches to Current Scholarship and Teaching, (ed.) Paul Cavill; D.S. Brewer, 2004, p.

27 & n. 35.

25

3a).

118

This, as noted by Roy Liuzza and Benjamin Slade, is the manuscript reading,

which, even though it now reads hænum, in fact has “an original ð erased between the

æ and the n.”

119

Most editors have emended it to hæleðum, ‘the hero(es)’, Kiernan

retains hænum, ‘the lowly ones’; but ‘the heathens’ is just as appropriate an

appellation for the Geats who, if they even existed,

120

did so long before any

Christianity had reached northern Europe. In any case, the Geats’ heathenism seems

to have been less of an issue for the poet than the Scyldingas’ similar state, mainly

because they did not engage in conspicuously heathen activities that from a Christian

point of view would have damned them to hell. Concerning the other heathens in the

poem, hell is of course the fate of the heathen Grendel (l. 852a, 986a) – who was both

Godes andsaca, ‘God’s adversary’ (l. 786b, 1682b) and feond mancynnes, ‘the enemy

of mankind’ (l. 164b, 1276a) – which was made explicit when hæþene sawle...hel

onfeng, ‘his heathen soul...hell received’ (l. 852). Elsewhere, the word hæðen is twice

used to describe the treasures of the dragon’s hoard (l. 2216a, 2276b), which may

equally refer to the dragon being a heathen creature, or to the undoubtedly heathen

state of the people who had originally deposited the treasures into the barrow along

with their dead chief a millennium ago. When the gold is taken from the dragon’s

barrow and then re-interred into Beowulf’s barrow, it is not called heathen as such;

but the poet comments that the treasures are again eldum swa unnyt þær hit æror wæs,

‘just as useless to men [in] there [as they were] before’ (l. 3168), which “recall[s] the

biblical injunction against ‘storing up treasures on earth’ (Matthew 6:19),”

121

echoed

in the tenth century poem, The Seafarer,

122

and probably points to the gold still

considered as heathen, since it was not orthodox Christian practice in the tenth

century, to bury the dead with grave-goods.

118

Hæðnum can only be a dative plural (unless this is one of Lapidge’s ‘literal’ errors where the ū was

mistaken for a open-topped a in the exemplar, and since hæðen is declined like hand, they may in that

case agree with one another), and handa may be anything but a dative plural; to can govern the dative

or the genitive, and mean not just ‘to’, but also ‘at’ and ‘by’. It is also interesting to note that another

occurrence of hæðnum (l. 2216) also has hond and wæge in the same line, suggesting that there is a

deliberate mirroring of terms here; firstly that a cup is given to the heathen one(s), and secondly that a

cup is taken from the heathen (hoard).

119

Benjamin Slade, ‘Semi-Diplomatic Edition (Old English Text only with notes on the MS)’, Beowulf

on Steorarume (Beowulf in Cyberspace), (ed.) Benjamin Slade; http://www.heorot.dk, note for l.1983.

120

Probably not, since they were a fantastic, fictitious tribes from whom many a nation assigned at

least part of its descent, if the equation is made with the Geatas and the Getae, Leake, passim, but esp.

p. 71-9, 127ff.

121

Beowulf: A new verse translation, (trans.) R.M. Liuzza; Broadview Literary Texts, 2000, p. 38.

122

The Seafarer: ‘Though he wished the grave with gold to strew, the brother for his brother, he buried

beside the dead the precious things that he himself would wish with him; [but] for that soul who was

full of sins he could not [give] gold [as] a consolation against God’s awesome power, for he had

hoarded it before whilst he was living’ (l. 97-103).

26

When one turns the search from heathen practices to practitioners, the

evidence is just as slim on the ground; and not just in Beowulf, but in the Germanic

world in general. Complicating the matter is the lack of a permanent priesthood,

comparable to the established ecclesiastical hierarchy of Christianity, in the pre-

Christian Germanic religions where the role of a people’s spiritual leadership was

appropriated by the secular leader.

123

This dovetailing of spiritual and secular

authority is preserved best in the Icelandic sources in the duties of the great land-

owning magnates of the goði, the island’s de facto rulers, whose sacred role in pre-

Christian times was to be “responsible for the upkeep of the temple and ensuring it

was maintained properly, as well as for holding sacrificial feasts in it.”

124

Nowhere

else in western European sources is the overlap so well defined, though hints of it

may be found in enough diverse examples to conjecture that the priest-chief was once

the pre-Christian norm. Earl Hákon Grjotgardsson of Lade, ‘held [ie, presided over]

sacrifices’,

125

King Radbod of Frisia, was arguably the chief worshipper of his god,

Fosite,

126

and the ‘custodian’ of the idol in Walcheren was clearly a wealthy man

since he not only owned his own sword, but was apparently unable to be brought to

compensate Willibrord for attempted murder, indicating his higher social status.

127

In

Anglo-Saxon England, King Redwald arguably tended his own temple, as there is no

mention of any priest(s) who performed this task; likewise, he was able to add another

god (Christ) to his ‘set’ without any opposition.

128

It is also telling that there is no

mention of a Christian priest who accompanied him from Kent after his baptism,

suggesting that he expected to be his own priest.

129

Lastly, King Edwin, prior to his

conversion, is chastised by Pope Boniface in a letter to Æthelburga queen, for

123

Przemysław Urbanczyk, ‘The Politics of Conversion in North Central Europe’, The Cross Goes

North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300-1300, (ed.) Martin Carver; York

Medieval Press, 2003, p. 19-20.

124

The first generation of Norwegian emigré goðar also usually built these temples in Iceland;

Hrafnkel’s Saga and other Icelandic Stories, (trans.) Hermann Pálsson; Penguin Books, 1977, ch. 2, p.

36; Eyrbyggja saga [in] Gisli Sursson’s Saga and The Saga of the People of Eyri, (trans.) Judy Quinn

& Martin S. Regal; Penguin Books, 2003, ch. 4, p. 75-6.

125

Urbanczyk, p. 19.

126

Alcuin, Life of St. Willibrord, [in], The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany, (trans., ed.) C.H.

Talbot; Sheed & Ward Ltd., London, 1981, p. 10-11.

127

However, the Anglo-Saxons were foreigners in the area and may not necessarily been covered for

reimbursement for physical attacks under local Frisian law, and in any case the attack was justified

from the Frisian point of view, since Willibrord had attacked the idol first. Luckily for Willibrord, God

was there to settle the matter in his favour, since one suspects that in real life the ‘custodian’ would

have won any case brought against him; ibid., p. 12-3.

128

It is only sole Christian worship to which Redwald’s wife and advisors seem to object.

129

Bede, HE, 2:15, p. 133.

27

‘serving abominable idols’ “with the implication that [he] was involved in these

ceremonies.”

130

Ian Wood has pointed out the discrepancy, across the Germanic world,

between the meagre references to priests in the literature, and the number of words

which mean ‘priest’.

131

One such word is the Old Norse þulr, whose role seemed

primarily to be that of a speaker, as shown through the closely related words þular,

‘poetic lists and mnemonic catalogues of beings and events’, and þylja ‘to speak,

recite, chant’.

132

A secondary association of the þulr is with engaging in divination

and prophecy,

133

and being considered a keeper of wisdom and knowledge.

134

The

earliest occurrence of this word is from a memorial stone in Snoldelev, Denmark,

whose inscription, Gunnwalds stæinn sonar Hróalds þulaR á Salhaugum, “the stone

of Gunnwaldr Hróaldsson, ‘speaker’ at the hall-mounds” is dated to the ninth

century.

135

The þulr seems to be a Scandinavian phenomenon, but there is a cognate

word in Old English, þyle, which Adelaide Hardy first argued may be translated as

‘heathen priest’.

136

Outside of Beowulf, þyle occurs only in Widsið as the name of an

ancient hero in Þyle [weold] Rondingum, “Þyle ruled the Rondingas” (l. 24b),

137

and

in five Old English glosses – twice for orator in the Cotton Cleopatra A.III, (l.4455)

130

Bede, HE, 2:11, p. 124; Barbara Yorke, ‘The Adaptions of the Anglo-Saxon Royal Courts to

Christianity’, The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300-1300, (ed.)

Martin Carver; York Medieval Press, 2003, p. 252.

131

It is interesting to note here that ealdormann is a synonym for preost in the Thesaurus of Old

English; Ian N. Wood, ‘Pagan Religions and Superstitions East of the Rhine from the Fifth to the Ninth

Century’, After Empire: Towards and Ethnology of Europe’s Barbarians, (ed.) G. Ausenda; The

Boydell Press, 1995, p. 258.

132

Cleasby-Vigfusson.

133

Odin is the fimbulþulr (Ynglingatal, st. 6), and his alter ego in Hávamál calls both himself (st. 80,

111, 134, 142) and the speaker of the chair at Urthr’s well a þulr...and also sacrifice as in Ida Masters

Hollowell, ‘Unferð the þyle in Beowulf’, Studies in Philology, v. 73:3, Jul. 1976, p. 244, (There may be

a link with the chair of the þulr and the platform used in seiðr, as well as to the platforms which may

be archaeologically found as an Anglo-Saxon construction over prehistoric mounds (Sarah Semple, ‘A

fear of the past: the lace of the prehistoric burial mound in the ideology of middle and later Anglo-

Saxon England’, World Archaeology: The Past in the Past: The Reuse of Ancient Monuments, v. 30:1,

Jun. 1998, p. 116-7), and the literary evidence from Gisli Sursson’s saga that esoteric rituals performed

on burial mounds which involved a nine-year old gelding ox and a scaffold structure, were in honour if

Frey (ch. 18, p. 30-1), who of course was the first of the gods/kings buried in a barrow in Saxo

Grammaticus, The First Nine Books of the Danish History, (trans.) Oliver Elton; Publications of the

Folk-Lore Society, Kraus Reprint Ltd., 1967, book 5, §171, p. 210-1; and Snorri Sturluson, Ynglinga

saga, ch. 13-5, [in] Heimskringla: Chronicles of the Kings of Norway, (trans.) Samuel Laing;

http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/heim/index.htm.

134