Stanisław Owsiak

Cracow Academy of Economics, Poland

Taxes in Post-Communist Countries - a Tool of New Tyranny?

Introduction

After several years of systemic transformation, the former countries of real socialism still have to cope with institutional and doctrinal challenges. These challenges are undoubtedly derived from the experience, theoretical views and social doctrines of highly developed countries. The implementation of specific solutions by post-communist countries is even more difficult as those which had fully embraced a market economy are now witnessing an evolution of theories and doctrines. Additionally, the social, economic and institutional environment of transition economies is different from that found in other countries. One of the key challenges is both the state's ability to use taxes in new circumstances and the taxpayer's ability to respond to the instruments applied by the state.

In the area of taxes, in general, there exist a number of controversies. This is not unusual provided that the taxes' fundamental functions are not questioned in the course of the discussion. And we have in mind the following: fiscal, redistributive and stimulating. Taxes in the fiscal function represent a tool applied by the state to accumulate income. As it is, this function implies determination of the extent of state interventionism in incomes. From the psychological point of view, the question arises as to whether a post-communist state has not merely replaced the form of citizen oppression from that of bureaucratic bans and decrees to taxes. This thesis is justified given the fact that large social groups suffer as a result of the ongoing transformations. Therefore, it is worth considering whether the post-communist state is not treated by its citizens as a hostile (estranged) institution, with taxes representing a new tool of oppression, of tyranny. Such a possible perception of the state would create conditions for its cheating in the area of taxes, on the one hand, and a paralysis of state institutions in the pursuit of fiscal policy, on the other. The issue of the state's social legitimacy in levying taxes constitutes a condition for the approval of its activity in the redistribution sphere. It is carried out by means of tax instruments, namely, by setting tax rates, which, in turn, affect individual tax burdens. The same principle applies to the stimulating function of taxes. The political condition of state institutions will determine the effectiveness of taxes used as incentives, e.g., a hostile attitude towards the state may distort the taxpayers' response (abuse of institutions, tax breaks and other tax preferences).

Several years of transformation have already represented a valuable period for observation as they allow one to identify the most important features of the phenomena present in the tax sphere at the time. This will enable a comparison of tax systems in post-communist countries with those in place in highly developed countries, as well as comparisons between post-communist countries.

Legacy of the Former System

Given the gradual disappearance of taxes as an economic, social, psychological, etc., category in post-communist countries, transition economies were forced to undergo a tax revolution. For over forty years, the society was unaware, save for narrow groups of so-called `private entrepreneurs', of the existence of taxes. Meanwhile, taxes are an essential selection (decision) parameter used by businesses, and thus also enterprises, consumers and investors. The society's behaviour in tax civilization, initiated in Poland in 1992 with the introduction of personal income tax (PIT) and subsequently that of value-added tax (VAT) and excise duty in 1993, should be considered the primary object of investigation.

Under the former system, tax relations - by their nature giving rise to conflicts - were cushioned precisely by the taxation of state-owned enterprises, an extensive system of subsidies and, last, by the almost unlimited access of state-owned enterprises to credit facilities. Post-communist countries used to generate their budget receipts primarily from the public sector. In 1980, their share stood at 97.5% of the total Polish budget. Taxes and charges imposed on the population at that time accounted for 1.1%, and for 10 subsequent years their share grew to a mere 2.4%. In the seventies, Poland, Romania and Hungary additionally abolished payroll tax in the belief that the applied pricing and remuneration policy was an adequate instrument of regulating people's incomes. Although some countries attempted to reform the centrally planned economy in the eighties, in particular Hungary, and to some extent Poland, based on the concept that state-owned enterprises should be given economic autonomy, qualitative changes did not take place until after 1990.

A New Tax Civilisation?

In response to the shift in the nature and role of money, society's attitude to taxes was also bound to change. From that time on, paying taxes has become inevitable. Post-communist countries have therefore become tax states in the sense that they began to source the basic part of necessary budget receipts from taxation. In this context, a fundamental question arises as to whether post-communist societies have begun to take advantage of the blessings of tax civilisation with the advent of tax obligation. After all, the current status of tax issues is the result of many centuries of evolution in tax relations between the oppressors and the oppressed. It is an element in the changing democratic order. The whole matter concerns public authorities observing elementary principles of taxation, such as fair distribution of tax burdens, stability of tax burdens, universality of taxation, etc. These achievements include also society's control over the manner in which public money is expensed.

Under tax civilisation, tax relations are present in almost all spheres of economic and social life. Therefore, it is crucial for the state to secure the people's support for envisaged reforms. Otherwise, it would be difficult to mitigate the impact of the conflicting nature of tax relations. The state should not treat every single citizen as a tax offender. The taxpayer, on the other hand, is expected to refrain from perceiving the state as an alien and hostile creation the cheating of which is considered a normal practice. On the contrary, the state is to be perceived as the common good that should be endowed with trust. This would be reflected in a rational approach to imposed tax burdens and in the optimum allocation (spending) of public funds by the state, i.e., in the execution of taxes' fundamental functions.

In practice and based on historical experience, we have come across far too many examples that are inconsistent with model relations between the state and the taxpayer. On many occasions, the taxpayer's attitude to the state can be described as hostile. This may be attributed to predatory taxation practices adopted by the state, flagrant waste of public funds, etc.

The following have an impact on the taxpayer's attitude towards tax burdens in a present-day tax state:

Volume of absolute tax burdens,

Distribution of tax burdens among individual groups of taxpayers,

Taxpayers' expectations regarding improvement in their material situation - on the acceptance of higher taxes - according to the principle that tax increases tend to be reflected in economic growth;

Allocation of the incomes intercepted by the state. Tax increases will not be opposed when they are attributable to reasons of utmost importance to the country or its region.

The construction of a new tax system that would take account of the operating principles of a tax state based on modern principles represents an enormous challenge. When we consider the tax mentality of post-communist societies, to a great extent still subject to historical factors, their attitude to the state and respect for the law, or their perception of civil obligations, we may well imagine the response of people to the idea of burdening their incomes with the financing of central government expenditure. The changes introduced in the area of taxation have been of specific significance for society's survival and development.

A characteristic feature of the transformation processes in the area of taxation were rapid shifts in tax awareness. They could be identified both on the part of taxpayers and the state, and more specifically, on the part of central and local government bodies, even though the direction and purpose of those shifts differed. Enhanced awareness helped taxpayers become rapidly conscious not only of the conflicts of economic interests inherent in taxes. This led to the development of rational - from the taxpayer's point of view - patterns of behaviour, including tax evasion scenarios. Although such shifts in the taxpayers' awareness can be recognised as understandable and acceptable, the question should be asked as to whether the state's attitude did not encourage such behaviour. Based on the Polish experience, it can be said that the state suffered from the syndrome of excessive tax awareness, understood to mean a lack of moderation in tax innovations. Relevant examples include the levying of taxes with retroactive effect, failure to adjust tax burdens for inflation (freezing of tax thresholds), unclear tax regulations, varying interpretation of tax regulations by revenue service, etc. The unfair treatment of taxpayers reflected in an artificial lowering of tax burdens for large taxpayers, on the one hand, and the revenue service's restrictive approach to honest citizens, on the other, created a natural environment for society's demoralisation in the area of taxes. It may, therefore, be stated that in many instances the post-communist state did not take advantage of the blessings of tax civilization enjoyed by highly developed democracies. The described modus operandi of the state and its agencies rendered the process of antagonising parties of tax relations surprisingly rapid in the period of transformation. No wonder that as early as in 1996 the grey economy accounted for over 20% of the official business activity in Poland. A few years of reform later, Polish entrepreneurs were fast becoming aware of the existence of tax havens such as the Channel Islands of Guernsey and Jersey, the Isle of Man, and Gibraltar.

According to the Instytut Badań nad Demokracją i Przedsiębiorstwem Prywatnym [the Research Institute on Democracy and Private Enterprise], the primary reasons for the expansion of the grey economy were excessive fiscal stringency and taxpayers' resistance to higher taxes. The issue of the grey economy is even more relevant in the Ukraine where, according to some experts, it matches in size the official one.

The encouraging conditions for the development of the grey economy on such a huge scale were created during systemic transformation, and extensive social and economic changes. Certain forms of tax fraud, new among Polish entrepreneurs, have been reported in the practice of post-communist countries. These include, for example, transferring profits abroad, establishing fictitious companies, faking bankruptcies, overstating actual costs, generating virtual costs through so-called `fake invoice trading' (reporting excessive costs of expert services). Despite the fact that in some cases these illegal practices are subject to multi-million fines or prison sentences, adopted countermeasures fail to curb the number and scale of fraud because of the difficulties encountered by the revenue service in detecting and proving this type of taxpayer behaviour. In the state's tax practices, there is a contradiction between various adopted tax-related concepts and the prospects for their enforcement by underdeveloped and unprepared revenue services.

In our analysis, we do not intend to idealise tax relations. Still, their structure and taxpayer's behaviour are obviously affected by the state's activity. The state is not always capable of preventing fraud but it can create conditions encouraging taxpayers to discharge their civil obligations. This would require the state to respect the fundamental rules of tax civilisation, and in particular to ensure:

moderate fiscal stringency,

stability of the tax system,

efficient operation of democratic institutions,

observance of the principle of certainty of tax burden,

accurate tax law,

a not overly complex tax system,

transparent relation between imposed tax burdens and resulting benefits,

an efficient prevention and repression system.

Otherwise, the state's activity may, not without reason, be perceived by taxpayers as a new form of tyranny.

Moderate fiscal stringency is especially important as excessive tax burdens provide a natural temptation to commit tax fraud. High taxes release the taxpayer from ethical indecision and dilemmas. As such, predatory fiscal policy encourages citizens not only to break the law but also to relinquish their moral standards.

Stability of the tax system should be considered another circumstance encouraging tax ethics as frequent changes in taxation rules (system) render the taxpayer naturally suspicious of the state's true intentions.

The taxpayer's ethical foundations are strongly impacted by the efficient operation of democratic institutions which enables control over imposed taxes and public spending. Otherwise, and in particular when corruption and pursuit of one's own interests are common and taxpayers' money is thrown down the drain, premises are naturally established for the protection of taxpayer's income against its waste by the state (its agencies). In such cases, tax evasion may be treated as rational, regardless of its ethical assessment.

From the point of view of taxpayer behaviour, it is important for the state to observe the principle of certainty of tax burden. Its implementation should translate into the substantial limitation, if not elimination, of interpretative freedom by revenue services in the area of tax legislation. Thus, accuracy of tax law becomes a fundamental condition. It is only natural that the introduction of taxes results in the establishment of new social and economic relations which are arbitrary in the sense that it is the state that determines who should be taxed, what should be taxed and how they should be taxed. Therefore, standards of the tax law and their legal interpretation should be accurate and so-called `interpretative gaps' minimised as far as possible.

Without doubt, taxpayer behaviour is influenced by an overly complex tax system. A high complexity of individual taxes encourages tax errors and fraud. Two reasons overlap here as, on the one hand, extensive and complicated tax scales, a complex system for computing taxable income, and various tax breaks and exemptions provide more opportunities for abusive practices, and on the other, they impair the collection of taxes payable to the state and their control by revenue services.

As has already been pointed out, a transparent relation between imposed tax burdens and resulting benefits generated as a result of the sacrifice made is of major importance for adding objectivity to tax relations between the state and its citizens. Such transparency is obvious when it comes to the direct beneficiaries of public spending. However, it falls short of exhausting the above condition as everything depends on the value system adopted by a given society. Taxpayers are ready to accept the sacrifice they make and will not attempt to evade taxes if they are aware that their money is spent reasonably by government authorities, e.g. on education, healthcare for the elderly, road network expansion, environmental protection, etc.

General taxpayer behaviour is greatly affected by an efficient system of prevention and repression for evading taxation through tax fraud. If the risk involved and related punishment are low, citizens display a natural propensity to commit tax offences.

Not all of the canons listed above must be implemented at any cost. Their significance also differs. While keeping in mind that qualitative taxation canons are important to the taxpayer, it should be underlined that the level of fiscal burdens remains the decisive criterion. In this case, it is hard to determine the optimum level of taxation. The difficulties facing transition economies can be traced to varied fiscal stringency in highly developed countries representing a combination of historical, cultural, religious, doctrinal, political, etc. reasons. This high differentiation limits a possible direct application of their experience. As it is, the phenomenon should be analysed on the basis of available statistical data.

Dispute over Tax Burdens' Volume

The dispute over tax burdens' volume has recurred over the entire history of taxation. The state constantly coped with the task of setting tax rates and establishing types and rules of taxation that would generate receipts necessary to carry out its functions. The views of citizens (taxpayers) on the issues related to tax burdens usually differ.

Taxes have always been perceived as a burden. For this reason, in constructing or reforming the tax system the state's challenge is to observe the principles of the establishment of a good tax system. The core idea behind such a system was illustrated in the most general, though blunt, terms by a comparison drawn in the 17th century by Jean Baptiste Colbert: `to collect taxes is to pluck a goose in such a way as to get as many feathers as possible, while keeping the noise level to the minimum'. This means that in constructing a tax system one cannot follow exclusively the criterion of tax effectiveness (efficiency). It is also necessary to consider the social and economic consequences of taxation.

In democratic systems, the scope of the state's interference with the incomes generated by enterprises and households is limited to some extent, whereas the allocation of public funds is subject to the criterion of rational management. Tax burdens must be derived from a trade-off between the interests of society and the economy, and the functions and responsibilities of public authorities. The achievement of these objectives is possible provided that paying taxes in the people's tax awareness is not a symptom of the state's perception as a tax state but, first of all, as a civic state.

Please note that the taxpayers' attitude to fiscal burdens is determined primarily by their understanding of the necessity to make a sacrifice for the sake of the common good. A citizen's tax awareness is determined by many factors. The decisive ones, however, are the benefits he or she gains from public funding. By nature, taxes differentiate society not only because of the distribution of burdens but also because of the varied level of benefits enjoyed by people. Unequal participation in tax burdens and benefits from public financing encourages taxpayers to seek solutions enabling tax evasion.

In post-communist countries, fiscal paradoxes did not take long to manifest themselves with great force. On the one hand, entrepreneurs and households began to demand lower taxes, while on the other they expected social security, employment guarantees and improved business infrastructure. Proposals for the state to assume more responsibility for various matters involving citizens continue to be filed. The only problem is that nobody is ready to accept the financial consequences (burdens) of such claims. These problems are not new to highly developed countries but they are present on a smaller scale. A good example is Sweden whose citizens do not wish to give up their acquired social rights even in return for lower taxes.

Thus, the description of tax relations in post-communist countries constitutes a new symptom of tax tyranny. This time it is the taxpayers' tyranny over the state. It takes the form of various claims being submitted to the state and is characterised by citizen unwillingness to accept higher taxes. Given that post-communist countries have committed numerous mistakes in their tax practices since the beginning of the transformations, their position is weak and unstable. The climate surrounding fiscal policy and revenue service is bad. No wonder that a sort of tax stalemate is observed at this stage of the transformations. All attempts to improve the tax system on the part of the state are treated with suspicion and highly criticised by the media. On the other hand, there is also strong resistance against cuts in budget expenditure. The deadlock contributes to a growing budget deficit and increased public indebtedness.

Let us then take a look at the quantitative aspects of fiscal policy in selected countries undergoing economic transformation, and at the changes witnessed in the period of reform. The current situation of these countries will be compared with OECD countries. Given that the degree of fiscal stringency on the part of central government receipts may differ from that observed on the part of central government expenditure, both perspectives need to be discussed. Table 1 presents the degree of fiscal interference in Vysegrad Group countries in the years 1991-2003.

Table 1. Share of central government receipts in GDP

Countries |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003P |

Czech Republic |

x |

50,3 |

47,0 |

46,4 |

48,0 |

48,9 |

44,1 |

43,3 |

42,9 |

42,8 |

39,9 |

40,8 |

40,3 |

Hungary |

53,8 |

53,2 |

53,2 |

52,4 |

49,3 |

48,1 |

46,6 |

47,5 |

46,7 |

46,2 |

45,7 |

43,8 |

43,5 |

Poland |

44,2 |

47,8 |

49,9 |

45,9 |

44,7 |

43,3 |

42,9 |

41,5 |

41,5 |

37,7 |

37,2 |

37,5 |

37,7 |

Slovak Republic |

x |

x |

x |

54,8 |

54,5 |

53,4 |

57,5 |

55,4 |

50,3 |

48,1 |

45,8 |

43,4 |

42,1 |

P - forecast

Source: OECD.

The data contained in Table 1 show that post-communist countries have witnessed a distinct decline in fiscal stringency measured by the ratio of total public tributes to GDP. In Poland, in 1993 their level stood at 49.5% of GDP, whereas in 2002 it dropped to a record low of roughly 37.5 %. This fall is attributable to shrinking tax receipts following the systematic lowering of corporate income tax rates from 40% in 1996 to 27% in 2003. The tax policies of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia have followed a similar trend.

The size of the state, measured by the volume of central government receipts, is impacted, to some extent, by the privatisation of state-owned enterprises. This impact varies depending on a given country and the implemented privatisation model. However, the effects of privatisation must be taken into account as this process is not indifferent to the national budget, implying either receipts or expenditure, or both. Meanwhile, otherwise necessary ownership transformations are not always effective, and privatisation becomes an objective in itself (doctrinal) instead of being a tool of controlled changes in the economy. State-owned enterprises in Poland have often been privatised forcefully, which has led to rapid bankruptcies. This, in turn, has contributed to the shrinking income (tax) base of the central government budget, higher unemployment and additional spending on social benefits.

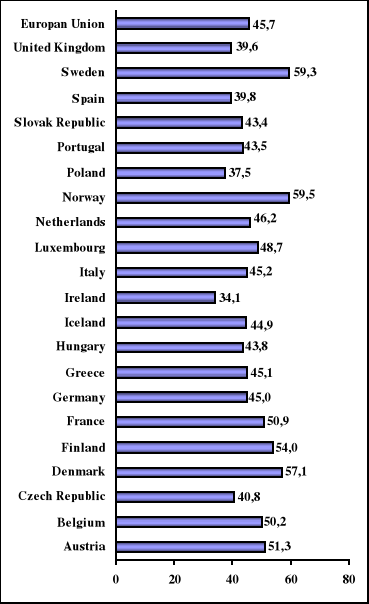

The fiscal stringency indicators shown in Table 1 on the income side will now be referred against the values recorded in selected OECD countries. The comparison is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Central government receipts as % of GDP in selected OECD member states in 2002.

Source: own materials based on OECD data.

This comparison elicits a fairly surprising conclusion, namely, that despite the substantially different stage of development of post-communist countries in relation to the presented OECD countries, the degree of interference with budget receipts and thus the scale of GDP redistribution in the countries of the Vysegrad Group is not excessively high. This ratio differs substantially not only from those recorded in Scandinavian countries but also from those reported in many other economies. It is especially evident in Poland.

The ratio of the state's interference with budget receipts (GDP) does not provide sufficient grounds for assessing fiscal stringency, as the state may allocate far more resources if its expenditure is financed with loans (public indebtedness). Table 2 shows the share of central government expenditure in GDP in the countries of the Vysegrad Group in the years 1991-2003.

Table 2. Share of central government expenditure in GDP

Countries |

1991 |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003P |

Czech Republic |

x |

54,6 |

70,2 |

49,9 |

60,4 |

50,7 |

46,5 |

47,9 |

46,6 |

46,9 |

42,6 |

45,3 |

43,6 |

Hungary |

56,7 |

60,3 |

59,8 |

63,4 |

56,9 |

53,9 |

54,9 |

56,7 |

51,8 |

49,1 |

50,9 |

52,2 |

49,0 |

Poland |

53,4 |

54,9 |

54,3 |

49,4 |

47,2 |

46,2 |

45,6 |

43,8 |

43,4 |

40,7 |

42,4 |

43,2 |

43,9 |

Slovak Republic |

x |

x |

x |

58,2 |

57,0 |

61,2 |

63,0 |

60,1 |

56,7 |

58,8 |

53,1 |

50,6 |

48,2 |

The source and markings as per Table 1.

It is worth pointing out that in the first years of transformation the share of central government expenditure in GDP grew. In the Czech Republic, it even reached 70.2% of GDP in 1993, in Hungary - 63.4 % in 1994 and in Slovakia - 63% of GDP. However in 2002, in a relatively short time given the ongoing dramatic changes, it stabilised at a substantially lower level.

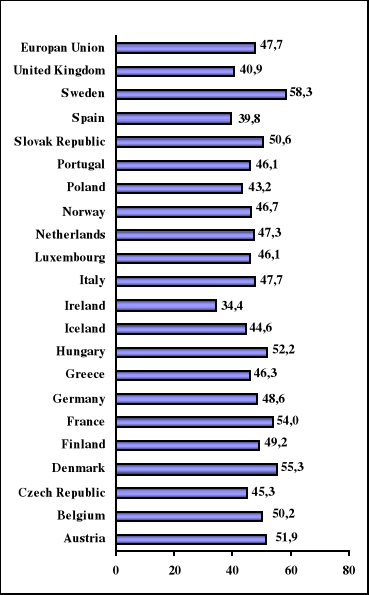

The curbing of fiscal stringency also takes the form of cuts in public spending. Poland redistributes 43.2% of GDP via its public finance system, less than the European Union (47.7%). In Slovakia and Hungary, the scale of GDP redistribution is bigger. Still, these states do not generate the highest ratios among OECD members, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Scope of GDP redistribution by the public finance system in selected OECD member states in 2002.

Source: As per Figure 1.

Transition economies also follow the path of reduced expenditure, though not to an extent allowing for the balancing of their budgets. Doubts have been raised as to whether this type of fiscal strategy is acceptable to these countries, given that the conditions of fiscal policy are essentially different.

Inertia in the volume and structure of central government expenditure, widespread among highly developed countries, should here be stressed. This phenomenon is underestimated by transition economies, which, unfortunately, may lead them up another blind alley. In the context of strong pressure to lower tax burdens, the governments transforming their economies seem to display a certain ignorance of real potential savings (cuts) in central government expenditure.

The search for budget savings by the Czech government has also ended spectacularly recently. In protest against the planned elimination of 13th and 14th monthly salaries paid in the form of bonuses to school and university teachers, a one-day strike was announced. The strikers were later joined for one hour by the staff of revenue and cadastre offices. The strike was supported by 35% of Czechs who believe that teachers' salaries are too low (mean salary is below the national average). It is precisely this social group that is under attack also in Poland. There are attempts to limit the already slow salary growth by rendering professional promotion criteria more restrictive (through extending the time lag between promotions). A strike has already been scheduled.

The following phenomena have been identified during the analysis of available fiscal data for the Vysegrad Group countries: 1) fiscal stringency is declining with time, 2) this decline applies to both the receipts and expenditure of central government, 3) the state has resolved to reduce the volume of central government receipts on a much larger scale than the volume of allocated resources (expenditure), 4) fiscal strategy has consisted in identifying, within the tax policy, factors encouraging faster economic growth even at the expense of weakening the state's fiscal clout (through a reduced volume of disposable incomes), 5) given the straightforward positive dependence between reduced taxes and declining central government receipts, the state has been forced to expand its public indebtedness.

The outcome of the fiscal policy pursued by transition economies is full of contradictions. Tax cuts have not been accompanied by projected rapid economic growth. Following the lowering of taxes, the effect of the built-up mass of central government receipts has been eliminated as unit tax burden has declined. In addition to the state failing to balance the national budget, public indebtedness was substantially expanded. On the other hand, the adopted policy of tax cuts has led to a dramatic fall in central government receipts, which has contributed to the state's reduced real (financial) impact on economic and social processes. The fiscal strategy pursued by these countries has raised even more questions when the difficulties facing them began to build up as economic transformations progressed. The main cause of this situation is the need for an in-depth restructuring of the economy as it becomes increasingly open and is set against external competition. From a rational point of view, the state's potential to impact difficult economic and social processes in such periods should at least remain unchanged. As far as the investigated countries of the Vysegrad Group are concerned, what happened was just the opposite. The adopted fiscal strategy, featuring a tax strategy, was greatly influenced by the doctrinal setting, and in particular the concept of a new fiscal conservatism whose building blocks are a) the smallest possible budget, b) neutral tax, c) a balanced budget, and d) declining public indebtedness. Some of the constituents of this new fiscal conservatism have been formally reflected in the European Union's Stability and Growth Pact (Treaty of Maastricht). In this context, a fundamental question arises as to whether transition economies are at the stage of economic (challenges of economic restructuring) and institutional development (quality of tax legislation, sophisticated revenue service) that would allow for the implementation of the doctrine of new fiscal conservatism.

External Doctrines - The Danger of Being Lured into an Imitation Trap

Tax system is derived from an adopted social and economic philosophy. The orientation and doctrine recognised by the ruling government are of crucial importance for the structure of this system. Still, the doctrine and agendas of political parties are often self-contradictory. For example, such a situation can be observed in Poland where politics lack transparency in the area of economics and social issues. The views of some Polish economists continue to be strongly influenced by American liberalism, whereas practical efforts for many years have been streamlined towards economic and social integration with the European Union where the economic and social model is different. In the EU, tax systems and welfare state models differ one from another but there exists a certain consensus on fundamental issues governing the everyday life of citizens. The authorities (both at central and local levels) assume political and financial responsibility. Therefore, any attempt by the state to decline responsibility for the citizens' elementary needs is doomed, and this forces the state to take ad hoc measures. Such measures are often more costly than when the government's activity is based on a carefully developed agenda supported by the people.

The susceptibility of individual states to liberal doctrines differs, which is reflected in the varied nature of their tax systems.

Decisions to carry out tax reforms in all transition economies have been accelerated by crises resulting from systemic shocks. A growth of central government expenditure higher than that of central government receipts in the initial years of transformation was bound to lead to a deficit, and thus to increased borrowing of the already indebted economies.

Some countries, including Poland, took trendy theories preached in the West and the resulting doctrines too seriously. In spite of the guidelines of new fiscal conservatism on the necessity to balance the budget, a number of highly developed countries not only failed to achieve budget balance but still cope with substantial difficulties in controlling budget deficit (3% of GDP). These countries include, among others, Germany, France and Italy. In this context, a revision of the Stability and Growth Pact is being considered. Over-zealousness in embracing the neo-conservative idea is even more questionable if this approach does not take account of differing realities of the countries transforming their economies.

Doctrinal confusion is also visible in relation to the tax reforms pursued in transition economies. In most of them (including the Vysegrad Group), the century-old tradition of tax collection has been leveraged, including in particular that developed by advanced democracies. Another path was adopted by the Baltic States which relied on single-rate taxation in the construction of their fiscal systems.

When reforming the tax system in Poland, the principle of central tax authority was observed and the principle was adopted of accumulating central government receipts by means of a number of major taxes (value-added tax, excise duty, personal income tax, and corporate income tax). There was also greater reliance, than prior to the reform, on indirect taxation. A possibility was envisaged for utilising taxes to achieve non-fiscal objectives and Poland's potential integration with the EU was taken into consideration.

In the initial period of transformations, changes to the tax system, including in particular the launch of two major taxes, namely, personal income tax and value-added tax, were easier as the population continued to show poor familiarity with the reforms under way. Neither did the state have enough time to commit tax-related mistakes. It is for these reasons, probably, that deep changes implemented in the tax system proved to be the success of both the authorities and society. Still, subsequent reforms of these taxes encountered considerable obstacles, which seems to reflect the awakening of the citizen tax awareness. Taxpayers' resistance was fuelled by obvious mistakes made by the state. The authorities turned taxes into a special tool for managing economic and social processes. The state's attitude in many instances can be described as blatantly irresponsible. This usually took the form of continuously modified tax policy concepts (partially implemented). When observing the politicians' behaviour in the area of taxes, one could get the impression that they juggle with tax instruments without fully realising that these `toys' may go off one day. This attitude is typical of almost all governments of post-communist countries where the applied fiscal tools fail to ensure financial stability but their reform is opposed by the society.

Various proposals of tax reforms submitted by political parties often lack consideration. For example, most efforts have been focused on the receipts side, whereas the expenditure side has been neglected. This approach sheds some light on the real problem of post-communist countries which concerns not the national budget or even central government finance but their social and economic model. In considering this problem based on the example of Poland, it is necessary to remember that the transformations in both the economy and the social sphere taking place after 1990 were spontaneous in nature. A perfect example is that of education and health protection. The priority in transition economies is to determine what areas the state is willing to finance with public funding, what it can afford and what it cannot afford. Only then is it possible to identify different detailed solutions, including legal guarantees (though not financial) extended by the state, such as operating conditions for the market of healthcare services, educational services, housing, transportation, arranged pursuant to commercial principles. Only then could the issue of lowering taxes be considered.

Subsequent governments have not attempted to model the social system and, after lowering some taxes, frantically search for additional receipts from other taxes. As evidenced by the experience of many countries, this search places them in an even more difficult situation. Let us consider a few examples. The first one is related to the trend characteristic for all transition economies, namely the lowering of corporate income tax which is justified as an attempt to raise competitiveness, create encouraging investment climate, and by doing so also to stimulate more rapid economic growth. At the same time, it is assumed that a decline in the share of direct taxation in central government receipts will be compensated for by an increase in indirect taxation, i.e., taxes payable by consumers. Furthermore, the lowering of corporate income tax is most often accompanied by hasty decisions like the one to abandon such perfect tools as tax breaks. Thus, the authorities are deprived of the possibility to rely on tax breaks as tools of economic and social policy. Poland's example shows that the removal of breaks in corporate income tax in return for lower single-rate tax rate has failed to generate a pro-growth impulse. Meanwhile, it is worth pointing out that the flagship thesis, and an argument used by the advocates of lower taxes that such a reduction would trigger pro-growth mechanisms as a larger part of gross profit will be reinvested, was negatively reviewed at the time of transformation when the investment rate in the economy did not climb but, on the contrary, declined. Elimination of tax breaks signals the return to traditional and conservative fiscal policy, under which taxes are assigned a neutral role.

The second thesis, according to which direct taxation can be lowered and the resulting loss in central government receipts may be compensated for by increased indirect taxation, has also been proved wrong. A textbook knowledge of the limits on the transferability of indirect taxes and on flexibility of demand for goods and services burdened with indirect taxes is ignored. In fact, it is precisely lower receipts from indirect taxation that were predominantly `responsible' for Poland's failing budget of 2001. This was so because relative balance between indirect taxes had been greatly upset for doctrinal reasons. Further lowering of direct taxes with a simultaneous growth in indirect taxation should be considered a hazard for society as it may end up with a financial crisis.

Corporate income tax should be reformed but moderation is recommended in doing so. Trial and error has always proved effective in this respect. The experience of many countries has shown that hasty decisions cause a lot of damage to central government receipts, budgetary balance, undermining trust in the state and democratic institutions.

Another example of the frantic search for additional budget receipts is the government's attempt to tax profits generated by universities in response to the planned lowering of corporate income tax from the current single rate of 27% to 19% and the lowering of personal income tax payable by individuals pursuing business activity from progressive taxation, currently ranging from 19%, 20% to 40%, also to single-rate taxation at 19%. Soon, we will be able to observe the negative consequences of the announced taxation of universities (both public and non-public) and nursery schools in Poland. If the government does not back out of this decision, it is most likely to hamper investment activity and reduce the scope of scholarship assistance offered to students.

Most controversies and misunderstandings have been, and still are, associated with the single-rate taxation of household incomes. Single-rate taxation has already been launched in Russia and in the Baltic States. Unsuccessful attempts to introduce it were also undertaken in Poland. Single-rate taxation is worth considering for one reason. It represents a building block of economic liberalism and the new fiscal conservatism described above. Though it is recommended by Western theory and doctrine, the concept has not been applied on a larger scale in highly-developed countries. Meanwhile, a number of the earlier mentioned transition economies seduced by this doctrine have incorporated single-rate taxation in their systems.

Single-rate taxation should not be launched exclusively on the basis of doctrinal premises. This step should be preceded by an in-depth investigation of the social and economic environment. The launch of single-rate taxation will inevitably shift tax burden onto low-income population. The issue lies at the heart of the discussion on progressive taxes, of more or less flattened progression, the number of tax thresholds, and ultimately single-rate taxation. These issues cannot be resolved if income distribution across society is not taken into consideration. Major differences are recorded between various countries and various periods in these countries. Therefore, it is income distribution across society and ongoing changes that strongly influence the tax system.

One of the tools used to measure income distribution across society is the Gini ratio whose value determines the degree of income concentration across society. The higher the ratio's value the larger the proportion of low-income population, and vice versa. In Poland, in the years 1987-1990 the Gini ratio amounted to 0.28 but in the years 1996-1999 it already stood at 0.33, to reach 0.34 in 2000. This trend shows that as time goes by income concentration by richer sections of the population is rising at the expense of poorer groups. In other words, the wealth and poverty poles in Poland at the time of economic transformation grow dangerously distant, despite the existence of progressive income tax. This is reflected in the expansion of the poverty zone and the number of persons cast outside the margins of economic and social life. So what speaks then in favour of single-rate taxation whose implementation costs would have to be borne by low-income taxpayers, via either increased direct taxation or indirect taxation raised out of necessity but not guaranteeing fiscal efficiency?

In the context of the quoted ratios, it would be impossible to ignore the question of ethics: what lies at the heart of structuring taxes in post-socialist countries: is it selfishness or some sort of social solidarity? The civilised world declared itself definitely in favour of the second option. In countries such as the United States, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium, the Gini ratio has remained stable or has shifted slightly in the course of the last 15 years. Meanwhile, in Estonia and Russia so often quoted by advocates of single-rate taxation, the situation was as follows: in Russia, the Gini ratio has jumped from 0.26 to 0.45 over the last 15 years, whereas in Estonia it has climbed from 0.24 to 0.37 (it is estimated that some 40% of Estonians live below the poverty level).

Income differentiation in post-communist countries is of major importance as the characteristic feature of these societies is income egalitarianism, the legacy of the previous political system. The findings of public opinion polls conducted in the three countries of the Vysegrad Group show that tax rates for low-income households are perceived as excessively high. In Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, there exists low tolerance for income differentiation. Over half of the citizens in each of these countries believe that the taxation of highest-income groups is too low. Income egalitarianism is certainly a remnant of the past era (real socialism) as is typically displayed by elderly persons. Younger people, more liberal in their views, think that tax burdens imposed on highest-income groups are adequate or excessively high.

The scale of income differentiation should be a sufficient argument for rejecting the proposed adoption of single-rate taxation which is inconsistent with the principle of tax justice. Tax pragmatists, rather than utopians, have managed a consensus in matters regarding tax burdens borne by citizens. It is incorporated in the specifically perceived taxpayer's tax (income) potential. This potential consists in higher-income persons contributing relatively more (progressive taxation) to the common good. Anyway, the whole issue is not only about tax pragmatism but, first of all, about the widespread acceptance of such a tax philosophy and the system of ethical values recognised by society. This is reflected in existing systems featuring progressive tax scales.

Transition Economies at the Tax Crossroads

Post-communist countries, soon to join the European Union, must take account of harmonization with EU law and guidelines when implementing reforms. The current trends in the tax policies of EU member states are focused on:

Abandoning direct taxes for indirect taxes, i.e., severing the relation between generated income and tax burden.

Mitigating fiscal burdens imposed on corporate profits, while limiting (eliminating) various tax preferences. Reduction of tax breaks and preferences is a step towards enhancing the neutrality of the tax system.

Mitigating tax progression in personal income tax via a reduction of the number of tax rates, often excessively sophisticated. In the nineties, significant changes were made by reducing the number of personal income tax rates in Spain (from 17 to 6), Luxemburg (from 25 to 17) or Germany (from 18 to 2).

Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary have chosen to follow a course of reforms consistent with that of the European Union. In each of these countries, progressive personal income tax has been put in place although with a varying number of tax brackets. The first lowest tax threshold has been set in the Czech Republic (15%). In Poland, the corresponding threshold was established at 19%, whereas in Hungary at 20%. The highest tax rate for these countries was placed at 32% in the Czech Republic and at 40% in Poland and Hungary.

If we were to consider fiscal stringency from the point of view of radical burdens imposed on personal income in the countries of the Vysegrad Group and the European Union, post-communist countries would be described as far less fiscally stringent. The highest tax rates in the European Union are found in France (61.9%), Belgium (60.27%), Finland (58%) or in Germany (55.77%).

Higher tax progression has been instituted in Ukraine. Although the highest personal income tax rates in Ukraine and Poland are the same, the highest tax thresholds definitely differ. Income subject to a 40% tax rate (320 USD per month) in Ukraine falls within the 19% tax group in Poland. Moreover, under the Polish system taxpayers earning almost 2.5 times more still pay 19% tax on their incomes. Income qualifying for 40% tax bracket in Poland must be about five times higher than in Ukraine (ca. 18,654 USD annually), as a minimum. Ukraine is planning to reform its tax system through the introduction of single-rate taxation covering only personal incomes. In the years 2004-2006, a 13% tax rate will apply and be replaced with 15% as of 2007.

Slovakia, another post-communist country with progressive taxation in place (5 tax rates ranging from 10% to 38%), intends to transform its tax system into a single-rate one, by unifying income tax rates at 19%. Thus, the situation of the poorest groups of the population, currently subject to 10% tax, will deteriorate.

Despite the fact that Poland scores high in international comparisons, there is a widespread feeling that existing tax burdens are excessively high, as evidenced - in the case of personal income tax - by the progressive tax scale for persons with the highest incomes. At the same time, it is stressed that due to the sophisticated system of tax breaks the average effective personal income tax rate fluctuates around 14% of taxable income (gross income). Average annual remuneration in Poland amounts to a mere 6,317 euro. As a result, 95% of the population pay taxes at the lowest 19% nominal rate, and factoring in tax breaks, at an actual rate of 13%.

The rate of the second direct tax, corporate income tax, has been gradually lowered since 1996, from 40% to the present 27%. As of 2004, a further reduction in the CIT rate is planned to 19%. This rate will apply also to individuals pursuing economic activity. Until now, such taxpayers have been settling their fiscal obligations pursuant to the principles applicable to natural persons, i.e., based on a progressive scale.

The major unresolved issue in Poland is taxation of agricultural activity. This problem requires a comprehensive approach in the sense that the identification of an optimum agricultural tax system should be closely linked to the search for the optimum model for financial burdening of agricultural activity with public tributes, in particular social security contributions. For example, under the existing Polish tax system a substantial proportion of the population and businesses operating in the agricultural sector is covered by neither personal nor corporate income tax. These issues must be addressed under integrative processes as this will determine the value of EU subsidies.

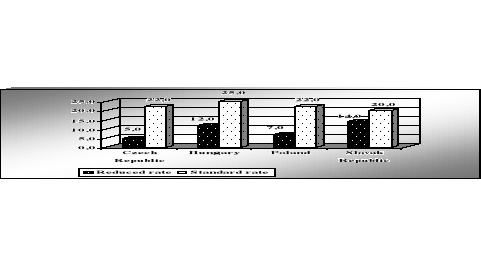

Tax harmonisation across post-communist countries is most advanced in the area of indirect taxes. Prospective EU member states have adopted the European Union's recommendations regarding base and reduced tax rates. Growing budgetary needs necessitated the introduction of higher than recommended (15%) base rates in the Vysegrad Group countries and in the Baltic States (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. VAT rates in the countries of Central Europe

Source: As per Fig. 1.

The highest base rate has been introduced in Hungary (25%). There is also a high, compared to other countries, reduced rate (12%). In Poland and the Czech Republic, base rates were set at 22%, whereas the reduced ones at 7% and 5%, respectively. In the application of reduced rates, social aspects were taken into consideration. In the Baltic States of Estonia and Latvia, a uniform VAT rate of 18% has been put in place. The only exception is Lithuania which has a reduced rate of 5%. The data shown in Table 3 show a distinct differentiation of tax rates in OECD countries. The rates applied in post-communist countries fall within their top and bottom brackets.

Table 3. VAT/GST rates in selected OECD member states (as at 1 January 2003)

Countries |

Domestic zero rate1 |

Reduced rate(s) |

Standard rate |

Austria |

no |

10,0 and 12,0 |

20,0 |

Belgium |

yes |

6,0 and 12.0 |

21,0 |

Czech Republic |

no |

5,0 |

22,0 |

Denmark |

yes |

- |

25,0 |

Finland |

yes |

8,0 and 17,0 |

22,0 |

France |

no |

2,1 and 5,5 |

19,6 |

Germany |

no |

7,0 |

16,0 |

Greece |

no |

4,0 and 8,0 |

18,0 |

Hungary |

yes |

12,0 |

25,0 |

Iceland |

yes |

14,0 |

24,5 |

Ireland |

yes |

4,3 and 13,5 |

21,0 |

Italy |

yes |

4,0 and 10,0 |

20,0 |

Luxembourg |

no |

3,0; 6,0 and 12,0 |

15,0 |

Netherlands |

no |

6,0 |

19,0 |

Norway |

yes |

12,0 |

24,0 |

Poland |

yes |

7,0 |

22,0 |

Portugal |

no |

5,0 and 12,0 |

19,0 |

Slovak Republic |

no |

14,0 |

20,0 |

Spain |

no |

4,0 and 7,0 |

16,0 |

Sweden |

yes |

6,0 and 12.0 |

25,0 |

United Kingdom |

yes |

5,0 |

17,5 |

1 Zero rate applies only to domestic sales, exclusive of exports.

Source: As per Table 1.

Let us take another look at the reforms carried out in the Baltic States as these countries opted for a system other than that currently in force in the European Union and the Vysegrad Group. The model they have chosen is that of single-rate taxation. It consists in establishing a single rate for personal income tax (PIT) and corporate income tax (CIT). Once again, Lithuania proves an exception in this regard with different CIT and PIT rates amounting to 24% and 33%, respectively. In Estonia, single-rate taxation was established at 26%, while that in Latvia at 25%. Additionally, these countries have granted investors reduced tax burdens, sometimes even at zero level, to attract foreign capital. In an attempt to raise the competitiveness of their economies, they have also applied a system of incentives for investors, including tax breaks and preferences. This indicates clearly that the tax systems in place did not fit the `purely' single-rate taxation model.

The example of the Baltic countries was followed, with a delay due to the 1998 crisis, by Russia which launched a 13% income tax.

The majority of post-communist countries is currently facing the need to implement a major reform of the tax system, and more generally, that of the entire system of central government finance. The purpose of these efforts is to prevent another crisis in the context of changing the internal environment and imminent integrative processes. Such changes in transition economies should take place on an evolutionary basis, with the primary goal not to squander the conquests of the quiet tax revolution that goes back to the beginning of the transformations.

When analysing tax problems, one cannot ignore other public burdens as they affect the values and ratios of the state's fiscal interventionism discussed earlier (Tables 1 and 2, Figures 1 and 2). Social security contributions are the key issue here. In most transition economies, including Poland, the problem is not really excessive fiscal stringency but payroll charges in the form of social security contributions. As it turns out, despite the reduced level of taxes in the Baltic countries labour costs remain high because average social security contributions in the years 1999-2001 accounted for 33% of gross remuneration in Estonia, 36% in Latvia and 34% in Lithuania. Also in Russia, labour costs have been greatly impacted by social security contributions of 35.5%, at maximum. It is, therefore, easy to notice that reforms consisting in lowering taxes are not a sufficient criterion for assessing fiscal stringency. Poland, which displayed some moderation in lowering taxes, if we were to ignore politicians' tax rowdiness which failed to translate itself into legislation, is characterised by a substantially lower burdening of gross remuneration with social security contributions (25%). Unfortunately, when compared to OECD countries, it is Poland which displays the highest burdens. This illustrates the scale of the difficulties that Poland has to overcome, given that, despite high burdens on labour costs, the social security deficit remains enormous (approximately one third of pension fund contributions by hired labour is financed from the national budget).

Conclusions

Tax reforms carried out in all post-communist countries represent fundamental issues in the area of systemic changes. Their dimension has gone far beyond the purely economic or legal area. In fact, the implemented reforms have involved the political system, shifts in society's tax awareness, the manner in which central governments have managed their tax receipts, the scope of public authority freedom in managing these funds, etc. As time goes by and tax awareness is rising, the population, and in particular the groups whose material situation has deteriorated as a result of the changes, have begun to perceive taxation as a source of oppression. Today, taxpayers respond defensively to even slight increases in burdens. While being quite natural, their reaction cannot be accepted as this would mean negation of state institutions.

It should therefore be stressed that the dispute over taxes is, in fact, a dispute over the state's role in social and economic spheres. This is why controversies surrounding tax issues cannot be isolated from a more general debate. Otherwise, post-communist countries will continue to be perceived as alien institutions and tyrants, with the only difference being that this time they oppress their citizens by means of taxes.

A comparison of the experience of post-communist countries with highly-developed countries does not provide straightforward arguments to support the thesis of excessive fiscal stringency. On the contrary, fiscal stringency is far more widespread in OECD countries (with some exceptions). Far worse is the outcome of the comparison of tax practices applied by these countries with those employed by developed economies. Tax culture, especially that displayed by the state, is significantly lower. It is in this very sphere that we should search for the sources of the tax-based tyranny of post-communist countries. The weaknesses of applied tax practices have been highlighted before. Here, highly unstable tax policy damaging both the economic and social environment, sloppy tax legislation, the arbitrariness of rulings issued by revenue service staff on identical cases, etc., should rather be pointed out.

In the context of accession to the EU, certain transition economies must take account of tax-related solutions implemented throughout the Union (such as indirect taxes, avoidance of double taxation of profits). The tax strategy adopted by transition economies in relation to direct taxation cannot be pursued in isolation from social and economic conditions, and business outlooks. Lowering of taxes, giving them neutral status, balancing the national budget, reducing public indebtedness, etc. cannot be traced to the doctrine of new fiscal conservatism as even highly-developed countries have approached this concept with reservations. The ultimate objective cannot be to lower budget receipts and expenditure or to mechanically imitate the solutions adopted by other countries in isolation from the actual state of economic and social affairs. The thesis that the limitation of the state's presence in social and economic spheres, characteristic of extreme liberalism, allegedly always leads to enhanced economic effectiveness, rarely stands up when confronted with the experience of not only highly developed countries but also those with transition economies.

Given the above, the reforms under way in post-communist countries should not, at the present stage of in-depth restructuring of the economy, rely exclusively on tax cuts but instead should concentrate on measures enhancing citizen trust in law and on the removal of sources of tax-related abuse. The establishment of a legal framework that would render the tax system stable, transparent, simple, friendly to taxpayers, accompanied by concurrent implementation of a rational mechanism for allocating and controlling public spending, highlighting the relation between collected taxes and the benefits gained by local communities, would ultimately determine whether society will welcome the development of tax-related civil behavioural patterns. These are the basic conditions for parting with the concept of the new tax tyrants that post-communist countries are sometimes thought to have become.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

R. Antczak, Podatki liniowe - remedium czy propaganda [Single-rate taxation - a remedy or propaganda?], Centre for Social and Economic Analyses (CASE), August 2003.

Bolkowiak, System podatkowy w okresie transformacji w Polsce [The tax system in Poland under transition], Financial Studies, issue no. 53, Warsaw 2000.

Bolkowiak, E. Relewicz, Polityka finansowa, stabilizacja, transformacja [Finance policy, stability and transformation], Finance Institute, Warsaw 1991.

D. Bonifert, Tax Reform and Economic Policy, an abstract from Hungarian Economic Literature, 1989, issue no. 2.

B. Brzeziński, J. Głuchowski, C. Kosikowski, Harmonizacja prawa podatkowego Unii Europejskiej i Polski [Harmonisation of EU and Polish tax laws], PWE, Warsaw 1998.

J. Czekaj, Spór o reformy fiskalne. O podatkach? Po wydatkach! [Dispute over fiscal reform], Gazeta Wyborcza of 4th January 2002.

M. Dąbrowski, M. Tomczyńska, Tax Reforms in Transition Economies - a Mixed Record and Complex Future Agenda, Studies and Analyses, CASE 2001, no. 231.

Drogi podatek [Expensive tax], Businessman Magazine, May 2000.

Dryszel, Z(a)robić na szaro, Businessman Magazine, 1993, no. 11.

L. Ebrill, O. Havrylyshyn, Tax Reform in the Baltics, Russia, and Other Countries of the Former Soviet Union, IMF Occasional Paper 1999, no. 182.

O. Gadó, The Hungarian Fiscal System, “Hungarian Business Herald”, 1989, no 3.

Z. Gorzała, Kto zyska a kto straci przy stawce liniowej [Who is to gain and who is to lose

on single-rate taxation], Rzeczpospolita daily of 6 August 1998, no. 183,.

Joumard I., Tax System in European Union Countries, Working Papers, Department of Economics, 2001, no. 301.

B. Lesser (ed.), Economic Policy and Reform in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, 1992 to 2000 and Beyond, Halifax, BEMPT 2000.

S. Owsiak, Finanse publiczne. Teoria i praktyka, [Public finance. Theory and Practice], WN PWN, Warsaw 1999, second edition, revised.

K. Pankowski, Polacy, Czesi i Węgrzy o podatkach [Poles, Czechs and Hungarians on taxes], CBOS Report, www.cbos.com.pl.

.M. Pietrewicz, Polityka fiskalna [Fiscal Policy], Poltext, Warsaw 1996.

M. Rose, Podstawy niemieckiego systemu podatkowego [The foundations of the German tax system] in Niemiecki system podatkowy a reforma podatkowa w Polsce [German tax system and tax reform in Poland], Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, Warsaw 1991.

J. B. Rosser, M.V. Rosser, Another Failure of Washington Consensus on Transition

Countries, “Challenge”, 2001, no 2.

J.B. Rosser, M.V. Rosser, E. Ahmed, Income Inequality and Informal Economy in Transition Economies, “Journal of Comparative Economics”, 2000, no 3.

J.E. Stiglitz, Czarna dziura Busha, Project Syndicate, September 2003 (Polish translation

to be found in Gazeta Wyborcza of 19th September 2003)

Ukraine launches single-rate personal income tax, Polish Press Agency, Reuters, 22 May 2003, available at www.gazeta.pl

J. Wyciślok, Reforma systemów podatkowych krajów członkowskich OECD i Unii Europejskiej oraz ich harmonizacja [The reform of tax systems in OECD and EU member states, and their harmonisation], Videograf II, Katowice 2000.

D. Bonifert, Tax Reform and Economic Policy, “Abstract of Hungarian Economic Literature”, 1989, no 2;

O. Gado, The Hungarian Fiscal System, “Hungarian Business Herald”, 1989, no 3.

Cf. `Przegląd Podatkowy' [Tax Review] of 1994, issue no. 1.

A. Dryszel, Z(a)robić na szaro, Businessmen Magazine, 1993, issue no. 11.

Ukraine launches single-rate personal income tax, Polish Press Agency, Reuters, 22 May 2003, www.gazeta.pl

J. B. Rosser, M.V. Rosser, Another Failure of Washington Consensus on Transition Countries, “Challenge”, 2001, no 2.

Cf. M. Pietrewicz, Polityka fiskalna [Fiscal Policy], Poltext, Warsaw 1996, p. 70.

M. Rose, Podstawy niemieckiego systemu podatkowego [The Foundations of the German Tax System] in Niemiecki system podatkowy a reforma podatkowa w Polsce [The German Tax System and Tax Reform in Poland], Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, Warsaw 1991, p. 12.

I will not elaborate on this issue here. For more information on the sources of the success of the Polish tax reform, please refer to my book Finanse publiczne. Teoria i praktyka [Public finance. Theory and Practice.], WN PWN, Warsaw 1999, second edition, revised.

J.B. Rosser, M.V. Rosser, E. Ahmed, Income Inequality and Informal Economy in Transition Economies, “Journal of Comparative Economics”, 2000, no 3.

In Poland, a CBOS poll was conducted on a representative random and address-based sample of adult Polish residents (N=1,123); in the Czech Republic, an IVVM poll was conducted on a sample of 1,070 adult Czech residents; and in Hungary, a TRKI poll was conducted on a sample of 1,529 adult Hungarian residents.

K. Pankowski, Polacy, Czesi i Węgrzy o podatkach [Poles, Czechs and Hungarians on taxes], CBOS Report, www.cbos.com.pl.

B. Brzeziński, J. Głuchowski, C. Kosikowski, Harmonizacja prawa podatkowego Unii Europejskiej i Polski [Harmonisation of EU and Polish tax laws], PWE, Warsaw 1998.

J. Wyciślok, Reforma systemów podatkowych krajów członkowskich OECD i Unii Europejskiej oraz ich harmonizacja [The reform of tax systems in OECD and EU member states, and their harmonisation], Videograf II, Katowice 2000.

Ukraine launches single-rate personal income tax, Polish Press Agency, Reuters, 22 May 2003, available at www.gazeta.pl

L. Ebrill, O. Havrylyshyn, Tax Reform in the Baltics, Russia, and Other Countries of the Former Soviet Union, IMF Occasional Paper 1999, no. 182; B. Lesser (ed.), Economic Policy and Reform in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, 1992 to 2000 and Beyond, Halifax, BEMPT 2000.

R. Antczak, Podatki liniowe - remedium czy propaganda? [Single-rate taxation - a remedy or propaganda?], Centre for Social and Economic Analyses (CASE), August 2003.

See: J.E. Stiglitz, Czarna dziura Busha, Project Syndicate, September 2003 (Polish translation to be found in Gazeta Wyborcza of 19th September 2003).

2

Wyszukiwarka