New Forms Taschen 054

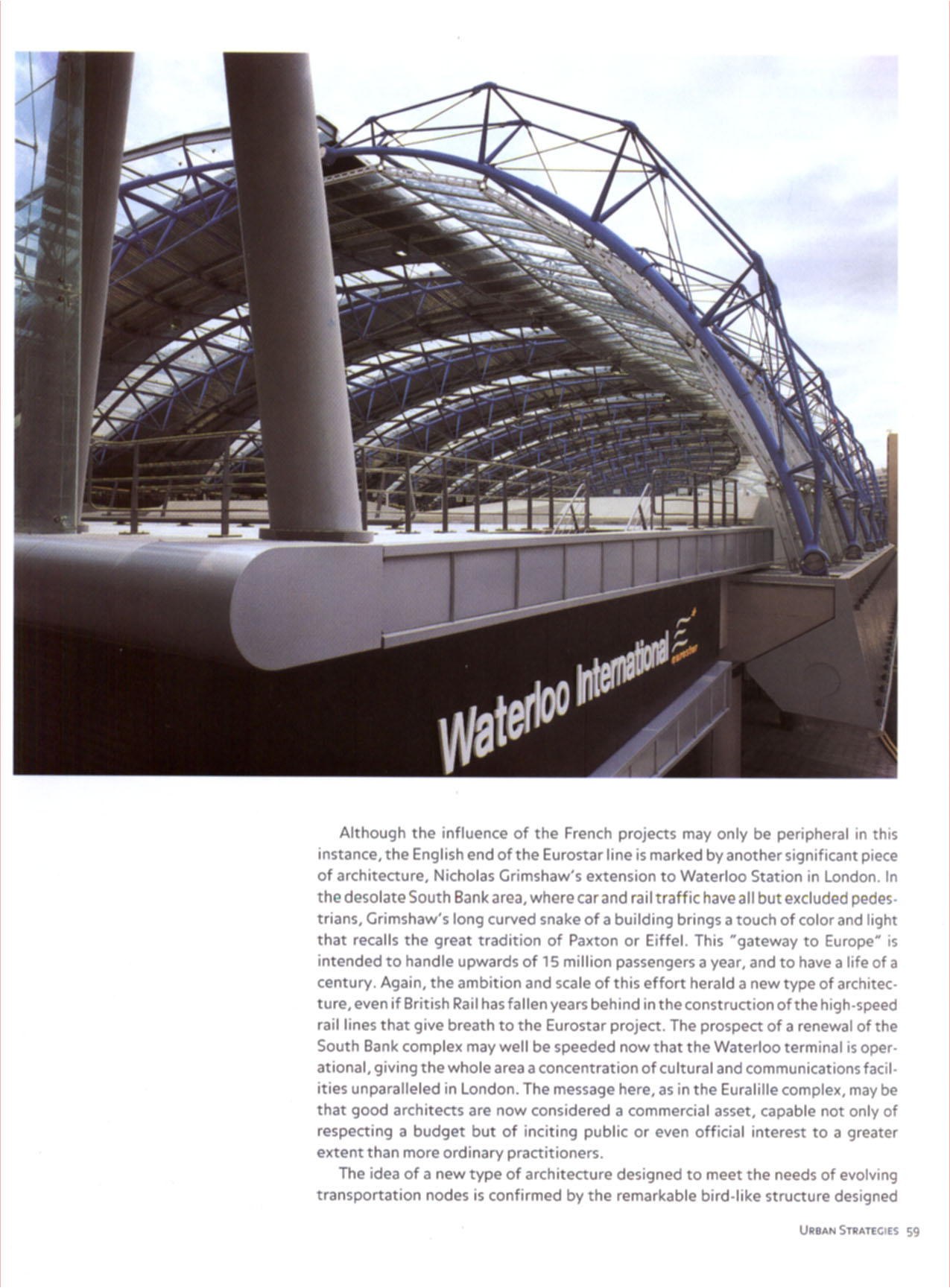

Although the influence of the French projects may only be peripheral in this instance, the English end of the Eurostar linę is marked by another significant piece of architecture, Nicholas Grimshaw's extension to Waterloo Station in London. In the desolate South Bank area, where car and raił traff ic have all but excluded pedes-trians, Grimshaw's long curved snake of a building brings a touch of color and light that recalls the great tradition of Paxton or Eiffel. This "gateway to Europę" is intended to handle upwards of 15 million passengers a year, and to have a life of a century. Again, the ambition and scalę of this effort herald a new type of architecture, even if British Raił has fallen years behind in the construction of the high-speed raił lines that give breath to the Eurostar project. The prospect of a renewal of the South Bank complex may well be speeded now that the Waterloo terminal is oper-ational, giving the whole area a concentration of cultural and Communications facil-ities unparalleled in London. The message here, as in the Euralille complex, may be that good architects are now considered a commercial asset, capable not only of respecting a budget but of inciting public or even official interest to a greater extent than morę ordinary practitioners.

The idea of a new type of architecture designed to meet the needs of evolving transportation nodes is confirmed by the remarkable bird-like structure designed

Urban Stratecies 59

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

New Forms Taschen 164 Although Kawamata vigorously rejects any relationship between his use of wood

New Forms Taschen 071 Holi is one of the morę thoughtful contemporary architeas. He has written, &qu

New Forms Taschen 144 architecture: "The installation represents the work site of an enormous b

76043 New Forms Taschen 051 Britain and Eiffel of France as subcontractors. Another huge Asian proje

New Forms Taschen 198 Although less poetic than his Unazuki Meditation Space, the Takaoka Station in

New Forms Taschen 055 by the Spanish engineer Santiago Calatrava for the Lyon-Satolas station, where

New Forms Taschen 118 1 _L „L- the modern purist tenants, and he may be right about that

więcej podobnych podstron