New Forms Taschen 189

new, sophisticated attitude towards Modernism coming out of SCI-Arc, the avant-garde school of architeaure that Thom Mayne's partner Michael Rotondi took over in the 1980s. Whereas Modernists had a f aith in industrial progress, signif ied by the white sobriety of the International Style, the Post-Modernists of SCI-Arc had a bittersweet attitude toward technology. They knew it brought pollution, knew that progress in one place was paid for by regress in another, but nevertheless still loved industrial culture enough to remain committed to the Modernist impulse of dramatizing technology.'33

Despite his cerebral approach, Morphosis principal Thom Mayne defines his work, such as the Kate Mantilini Restaurant, by making reference to film, albeit of the morę intellectual variety: "Jim Jarmusch madę the film Stranger than Paradise from nothing," he says. "Today, buildings are as ephemeral as film. The most solid aspect of my work is what has been published. The buildings are gone in ten years. Buildings are not that permanent anymore. There has got to be room in architeaure for the Jim Jarmusches, not just the Spielbergs.'34

Two projeas by Erie Owen Moss, his Ince Theater, in Culver City, and Samitaur in the same Los Angeles area, illustrate this young architea's approach.

The Ince Theater is a 1994 projea for a 450-seat theater to be located in the present parking lot between the Gary Group-Paramount Laundry-Lindblade Tower complex. Though not yet under construaion, another part of this series of buildings, now called Metafor (formerly GEM), is being completed. Intended for live performance or movies, the Ince Theater's unusual form is a computer-generated interaaion between three spheres. Whereas the other Gary Group buildings were largely conversions from existing warehouse space, the Ince Theater further explores the possibilities of spatial innovation that Moss proved himself to be capableof in the Lawson-Westen House (Brentwood, 1989-93). The apparent com-plexity of the struaure as seen in Computer drawings resolves itself into an unusual and elegant solution to the age-old problems of theater design. According to the origmal plans, a pedestrian bridge would link the theater to the as yet unbuilt Sony building across the Street. The presence of Sony would make the idea of a theater in this otherwise rather forlorn seaion of Los Angeles morę viable. Exterior and interior stairs would make it possible to dimb onto the roof. This is a dynamie form, and as Erie Owen Moss has said, "If a building itself can include oppositions, so that it is about movement or the movement of ideas, then it might be morę durable."

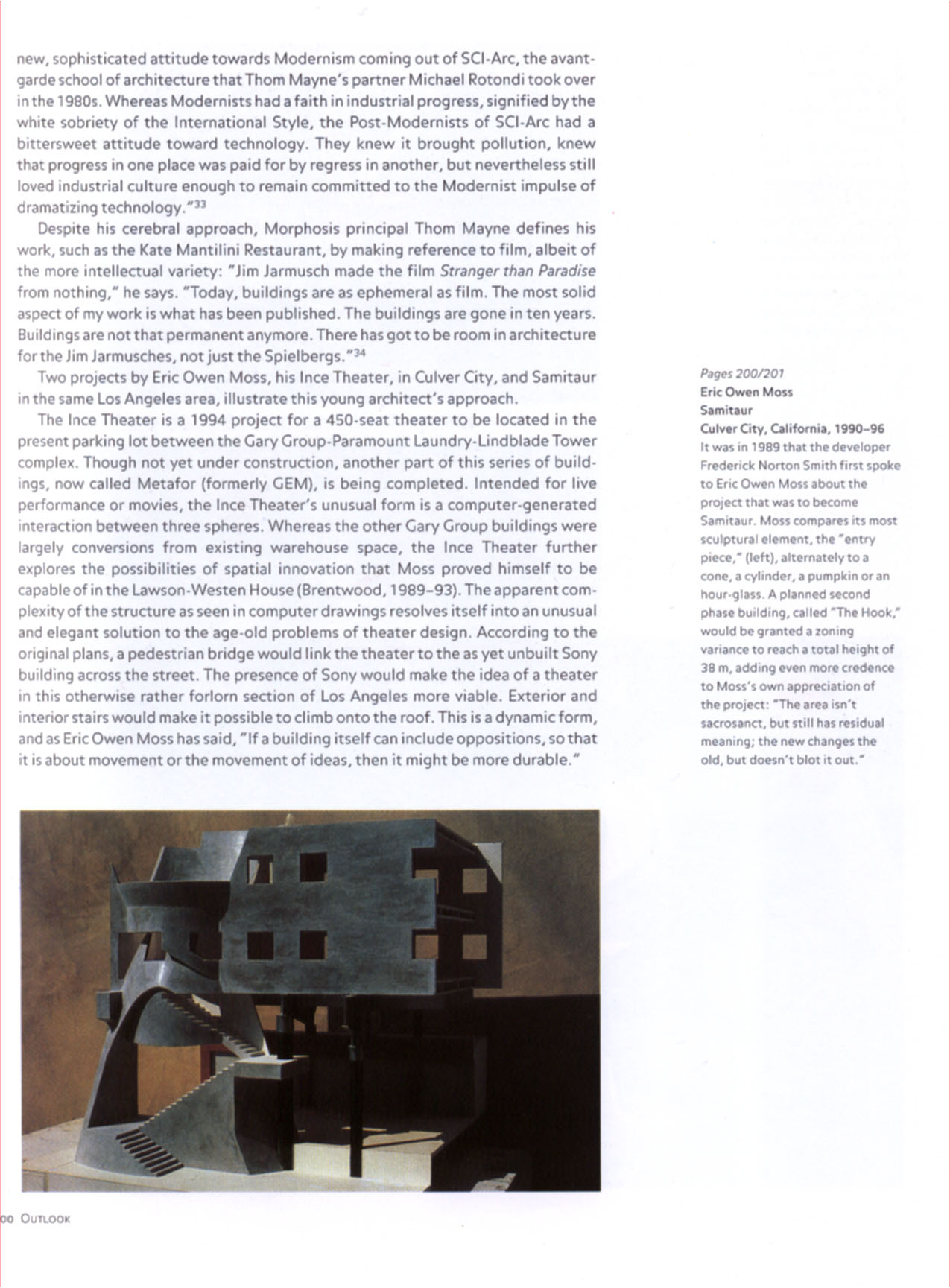

Ptges200/201 Erie Owen Moss Samitaur

CulverCity, California, 1990-96 It was in 1989 that the dcveloper Frederick Norton Smith first spokc to Erie Owen Moss about the project that was to become Samitaur. Moss compares its most sculptural element, the 'entry piece," (lef t). alternately to a conc, a cylinder, a pumpkin or an hourglass. A planned second phase building. called 'The Hook.' would be granted a zoning variance to reach a total height of 38 m, addmg even morę credence to Moss's own appreciation of the project: 'The area isn't sacrosanct, but still has residual meaning; the new changes the old, but doesn't biot it out.'

Outlook

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

New Forms Taschen 167 Bortom I.M.Pei Bell Tower Misono. Shiga. Japan. 1992 located at the end o

52837 New Forms Taschen 093 Page 101 Mario Botta San Francisco Museum of Modern Art San Fr

New Forms Taschen 123 Cultural Centers and Concert Halls The trend toward cultural centers intended

New Forms Taschen 072 In different circumstances, other American architects, Hodgetts + Fung have ev

więcej podobnych podstron