w251

‘Pope Boniface crowned at Anagni while his enemies are driven out’, depicted in the early-14th-century Croniche of Giovanni Villani. (Cod. Chigi. VIII, 296, f. 176r, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Romę)

return to the Italian battlefield, though during the 14th century Italian foot soldiers continued to play a major role in conflicts in mountainous or hilly regions. In mid-14th-century Savoy, for example, the brigandi were grouped into banderie units of 25 crossbowmen or 25 pavesań. Their methods of coordination and cooperation in battle are unknown. Elsewhere it seems that existing militia formations had become too large and unwieldy.

We know that in Florence in 1356 an elite of 4,000 crossbowmen - all ‘proven men’ - were re-formed into special units. Elsewhere surviving lists of equipment for selected infantry forces indicate the role they were expected to play. For example, the Statutes of Lucca from 1372 State that the constable's elite crossbowmen must have a corazzina or lorica armour, a helmet, dagger, sword, crossbow, a faretra pro piUoctis (special quiver), and a croceo (hook) to span the weapon, whereas the equipment required for ordinary crossbowmen was merely a rapo (helmet), dagger, crossbow, ordinary quiver, and a croceo.

Disciplined infantry tactics and use of the crossbow required regular training and in 1162 Pisa introduced a law obliging citizens to practise with the crossbow, spear and ‘Sardinian javelin\ Morę importantly, unit training instilled confidence in the face of an attack, while also main-taining a steady supply of adequately skilled and able crossbowmen. From the late-1 lth century onwards several urban militias seem to have trained weekly in an infantry counterpart to the better-known knightly tournament. The emphasis was clearly on discipline, as well as on the ability to move as a unit and to withstand a cavalry charge. Experience of the latter was providecl by militia caealry who ‘attacked’ their infantry col-leagues in open spaces in front of churches, outside city walls, on main roads, or on a specially designated campo de batalia (battlefield). In Bergamo in 1179 one particular training exercise is referred to as a ‘battle with smali shields’ which suggests light infantry training: tliis became morę common during the 13th century. All classes took part in what became a form of public enter-tainment. Wooden weapons were used in these pugneor ‘figlits’: we also know thatjudges imposed hea\y fines on anybody caught using iron weapons. By the 14th century such exercises often degenerated into brawls in which only youngsters took part: this in itself reflected the decline of the urban militias.

Practice with the crossbow was a morę indi-vidual affair, though it took place in areas set aside by the ruling bodies. There were also competitions which, like the one instituted in Pisa in 1286, drew in competitors and organised teams from other cities. In 1295 Yenice tried to ban all games except crossbow shooting at various bersagli (butts) in and around the city, where all men between the ages of

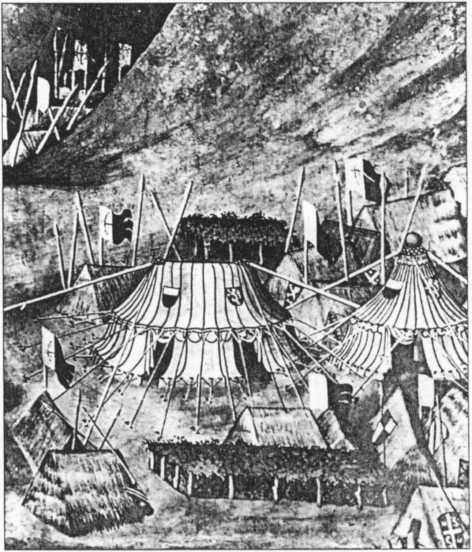

Detail from an early-14th-century wall-painting by Guidoriccio da Fogliano showing an army encampment. Senior officers have large tents while the ordinary militia live in grass huts. (In situ, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena)

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

w251 ‘Pope Boniface crowned at Anagni while his enemies are driven out’, depicted in

pop o bu cebule O C^ĄT e -ćCk^-tfn^ &n*4 uTo.zU "t t- ■?, a=2b (ceoU

ipe 20 31. While ting your tle, make ihe movemcnlt in slow motion Hołd your&n

m c+051+ +25 At cno of md 4. last cno ip= 2 ch + I dc in clostng sl ci below. RrrJ 5 : Ch 4 (=

31 Creative u-leaming: Complex ICT Use at the Masaryk Uniyersity Language Centre and structural plan

First research works on LCA at Poznań University of Technology 95 Table 3. Materials used in the ope

disorders. I continue my lecturing at the Academy of Health Education and Social Sciences in Łódź, P

Project 4 • Unit 1 Test A 1 Look at the pictures. Complete the sentences with the words in the

Snów Play Help the little boy get to his friends so he can join in the snów play. gry-gackMznor 1999

* * oEa mtfra, 9» «at Mt, Mm W «#ne ifcWk M Wtf# 4» iWtat pprtr In tyćdeątiom •o—w»K Im Mi 41M, 4 Ma

Er.gMflŁDdi3Łit.grcŁgniatign of thc Nga.W.gild Captain Smith s Style: - His works

więcej podobnych podstron