w25G

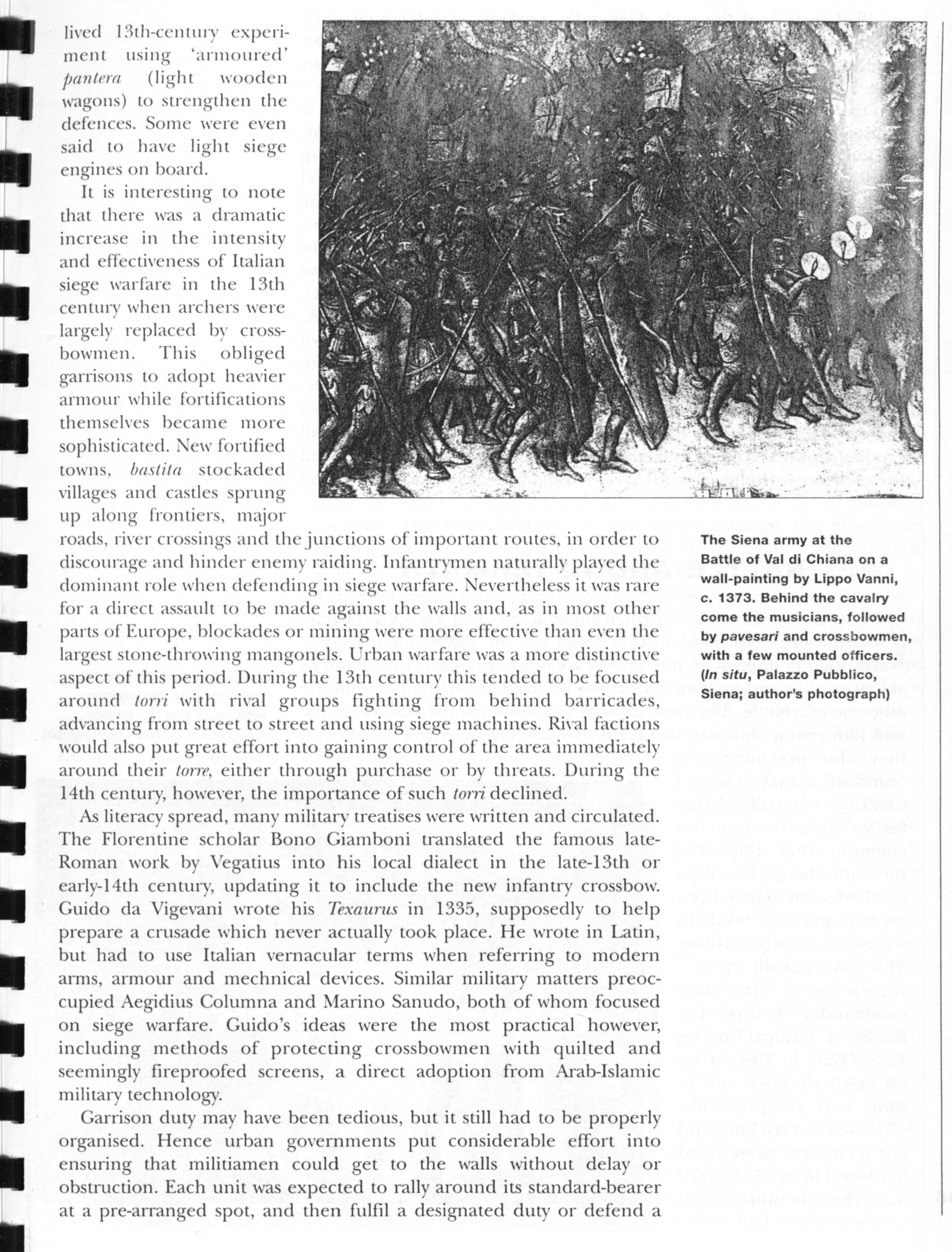

The Siena army at the Battle of Val di Chiana on a wall-painting by Lippo Vanni, c. 1373. Behind the cavalry come the musicians, followed by pavesari and crossbowmen, with a few mounted officers. (Irt situ, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena; author’s photograph)

Iivecl 13th-century experi-inent using ‘annoured’ pantera (Iight wooden wagons) to strengthen the defences. Sonie were even said to have Iight siege engines on board.

It is interesting to notę that there was a dramatic inerease in the intensity and effectiveness of Italian siege warfare in the 13th century when archers were largely replaced by cross-bowmen. This obliged garrisons to adopt heavier armour while fortifications themsehes became morę sophisticated. New fortified towns, baslila stockaded yillages and castles sprung up along frontiers, major roads, river crossings and the junctions of important rontes, in order to disconrage and hinder enemy raiding. Infantrymen naturally played the dominant role when defending in siege warfare. Neyertheless it was rare for a direct assanlt to be madę against the walls and, as in most other parts of Europę, blockades or mining were morę effectiye than even the largest stone-throwing mangonels. Urban warfare was a morę distinctiye aspect of this period. During the 13th century this tended to be focused around toni with rival groups fighting from behind barricades, advancing from Street to Street and using siege machines. Ri\al factions would also put great effort into gaining control of the area immediately around their torre, either through purchase or by threats. During the 14th century, howeyer, the importance of such toni declined.

As literacy spread, many military treatises were written and circulated. The Florentine scholar Bono Giamboni translated the famous late-Roman work by Yegatius into his local dialect in the late-13th or early-14th century, updating it to include the new infantry crossbow. Guido da Vigevani wrote his Texaurus in 1335, supposedly to help prepare a crusade which never actually took place. He wrote in Latin, but had to use Italian yernacular terms when referring to modern arms, armour and mechnical deyices. Similar military matters preoc-cupied Aegidius Columna and Marino Sanudo, both of whoin focused on siege warfare. Guido’s ideas were the most practical however, including methods of protecting crossbowmen with ąuilted and seemingly fireproofed screens, a direct adoption from Arab-Islamic military technolog)'.

Garrison duty may haye been tedious, but it still had to be properly organised. Hence urban goyernments put considerable effort into ensuring that militiamen could get to the walls without delay or obstruction. Each unit was expected to rally around its standard-bearer at a pre-arranged spot, and then fulfil a designated duty or defend a

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

14239 w25T Longinus and the Virgin Mary’ on a wall-painting in the church of Santa Maria inter

Art religiewcTHE INFLUENCE OF DUTCH GRAPHIC ARCHETYPES ON ICON PAINTING IN THE UKRAINĘ, 1600-1750 WA

52913 w25! Soldiers at the Crucifixion’ taken from a late-14th-century wall-painting by Altich

SHALLCROSS—8 “A Man at Respite: A Study of His Interior," a study on intersection of ideology,

m136 famcttua Sienese for ces at the battle of Sinalunga, 1363, in which Siena defeated the freeboo

m1447

m1447

m1447

więcej podobnych podstron