img018

from ilir supiłorl surface or to ncgotiate changes in inclination of the support Surface; musde and joint llcxlbllity to activcly ntove through required ranges; and ability to recruit niuscle synergies reci-piocally as well as to disassociate.right and left Iower extremities. The individual must also have approprlatc balancc to maintain body stability on this dynamie device, wliich in turn depends on the Intcgrity of visual, somatosensory, and vestibular Systems as well as coordination of balance strate-gics. In addition, success and safety with bicycle riding will be dependent on the individual’s percep-tion of his body in space in relation to stationary and moving objects in the immediate environment. Finally, we need to consider whether the bicycle fits the individual appropriatcly. Performance will be altcred if the bicycle is too smali or too large. AU of these factors operating simultaneously con-tribute to successful bicycle riding.

Notę■ the sitting posturę of the women with and without back support. Chaos is introduced when the women is asked to sit on the bali, a dynamie surface which is relatively unfamiliar. Of the many possible outeomes or choices, this individual chooses the optimal strategy. From a therapeutic stand point, the most erect posturę is optimal. If the individual were to remain in her preferred posturę, a posteriorly tilted plevis and lhoracic kypho-sis, morę musde activity would adually be reąuired to maintain a sitting position on the bali.

Systems theory incorporates the notion of order emerging from "chaos" in describing motor behavior. With chaos or random-ness, there are many potential outeomes. Each subsystem which contributes to the finał motor output (musculoskeletal, car-diopulmonary....) has variability inherent within it. In the case of a healthy biological system, this variability results in great flexibili-ty in potential movement strate-gies available to meet the demands within our environment.

Biological Systems are constantly challengcd to reorganize. that is, to find order and stability,

Optimization is the search for the best possible solution. With respect to movement, the optimal outeome will be the most efficient motor behavior that accomplishes the task. lf potential choices are limited, the search is narrowed and a sub-optimal solution may result.

This is often the case with our patients who have limited movc-ment options for any of a wide variety of reasons. [Kanim, et. al„ 1990]

As therapists. we evaluate and identify impairments in one or morę Systems in our patients which result in less efficient or unsuccessful motor performance. From an cvalualion standpoint. obscrving a patient while he or she is engaged in performing dynamie activitics with the Swiss bali (eg. bouncing while sitting on the bali) can procide us with useful insights about complex intcrrclatcd factors governing movement, for example, symmetry, balance. musclc and joint flexibility. strength, and so on. Through treatment we attempl to optimize function of the eompromised system(s) and thereby improve the movement outeomes. The bali, by virtue of its versatility, can be incorporated Into our treatments to influence many of the biological subsyslems that contribute to efTeetWc tmwement. The following chapters provide many safe and effcctive bali lcchniqucs that are available

<0 1995 by Joanna Posner-Mayar, PT

'I

I ^5,

4? 4 3 4 3 43 4?

4?

4°

43

!

43 43 I3

/—■•O v ■

c _ o

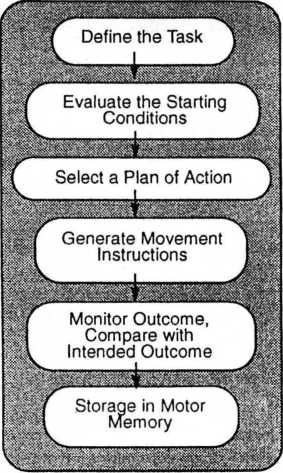

Figurę 1:2 Information Processing Model of Movement. The central and peripheral nervous system play a critical role at each stage of the process.

43

43

45?

c-5^»

c-™-3 ^ Bi - m O v ■

to improve musde flexibility, joint rangę of motion, sensory-perceptual integrity, alertness, strength, endurance, coordination, and balance.

Information Processing and Memory

The systems approach to motor control reminds us that we should look at multiple Systems or variables. However, we should remember that the central nervous system (CNS) serves as the common integrative element that ties them all together (Figurę 1.2). The central nervous system does this by First defining the goal or task. For example, do 1 want to bring a glass of water to my mouth and take a drink? Next, CNS mediated per-ceptual processes evaluate the starting conditions under which the task is to be carried out. Among starting conditions we include both significant or regulatory stimuli [Gentile. 1987];as well as intrin-sic stimuli related to the spatial orientation of the body, ntotivational factors, and the like. In our example. we might notę that the glass is sitting on a table at a particular distancc from us. that our dominant hand is holding a fork, and that we are thirsty.

The context is also rdled with irreievant or non-regulatory stimuli which may confuse or distract tlić individual front completing the task efficiently.

An example of such a non-regulatory stimulus

might be a dog barking at the front door. Next. through CNS activity, we select a plan of aclion (response sclection) and generate instructions for cxecuting the movement that will lead to task eom-pletion. The morę variable the conditions under which response sclection occurs. the morę potential choices there are for a succcssful movemcnt strategy and the longcr it takes to make the choice [Schmidt, 1988]. Movement generation occurs as the central and peripheral nervous systems activate musclcs with the appropriate timing and with the proper kinetics. As the movcment progresses, and/or after movement completion. the CNS monitors and compares actual movement outeome with the intended outeome. Did I successfully drink from the glass? Am I still thirsty? Finally. the degree of succcssfulness of the motor performance in achieving the goal and the motor program used in the behavior are Consolidated and stored in memory.

Neurophysiological and behavioral studies have provided many insights into the role of the CNS in this information Processing - movemenl generation - evaluation sequence. First, consider an individual's ability to identify the starting conditions in which a motor act is to be carried out. Stimulus identification reąuires accuratc sensory reception and perceplual Processing. Interestingly. the dcvelopment of normal sensation appears to require active movement. Kittcns, for example, who are moved passively in their environment fail to demonstrate normal visually guided motor behaviors (eg. parachute reaction and blinking to a rapidly approaching visual stimulus)[Held, 1965]. Active movement also appears to be critical for the ability of humans to adapt their motor

© 1995 by Joannę Posner-Mayer, PT

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

113 Changes in chemism of the Łabuńka river.. catchment. Calculations madę by H. Maruszczak (1990) f

115 Changes in chemism of the Łabuńka r.iver.. 6. From comparison of indices deter

File0030 1 Gel readv to LISTEN Work in pairs. Answer the questions. 1 Do you live

assignments from other courses or semesters is a violation of the academic honesty guidelines and wi

Poster Brestskaya krepost WAND RADIO BROADCASTING ORGANIZATION OF THE UNION STATE RUSSIA AND BELAR

img16 (2) Sensitiyity to Strain • Strain causes broadening of the diffraetion

24ddg32 EJ Source Codę Control Would you like to get the latest checked in copy of the files in this

106 Ryta Dziemianowicz, Adam Wyszkowski, Renata Budlewska The first step to ensure improvement in tr

29Anthropogenic changes in the suspended. Knighton A.D., 1989, Riuer adjustment to changes in sedime

więcej podobnych podstron