S5004027

Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain

The various stages of t rance imagery

Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain

STAGE 1:

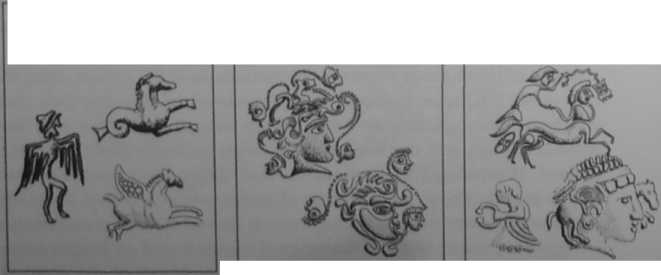

Subjects cxpcrience entoplic phenomena alone. These fonns oflen mulliply. rotulc and develop into compIex paltems. On the left are a rangę of (he kinds of images scen by experimental subjects. On the right are various motifs lrom LA coins.

STAGE 2:

Subjects try to make sense of entoptics by elaborating them into iconic Ibnns. The brain attempts to understand these images as it would impressions suppliedby the nervous system in a normal stale of consciousness.

STAGE 3:

A marked change occurs with individuals experiencing a vortex or rotaling tunnel around them. Within this vortex the first spontaneously produced iconic hallucinations appear, they eventually overlie the vortex as entoptics give way to iconic images. Even al this essentially iconic stage. entoplic phenomena may persist: iconic imagery is often projected against a background of geometrie forms. As fuli iconic hallucinations take place. sevcral common the mes recur in descriptions of trances.

1

Scnsations of wcightlessness

m

Transfomiation into on animal

11

Out-of-body cxpcricnces

Fig. 2.7 The developmcnt and stages of trance imagery

suggestive. This form of imagery was only displaced in the south-east by the arrwal of classical imagery in the late first century BC (see chapters 4 and 5).

The next stage in ASCs is where naturalisdc iconic images begin to appear to the fore against a background of a strong, tunnel-like image. This is also explicitly represented in Britain. On all the early coinage minted in Britain the horses are fairly disjointed affairs; the first relatively naturalistic image of a horse appears on British L and its derivativcs, a coinage issued somctime during or just aft er the Gallic Wars. Curiously, this naturalistic horse is immediately complemented on many coins by a strong tunnel or spiral-like radial image in the background (e.g. British Ma, VAi$2o:E6; Figs. 2.7 and 3.1). Again, serial development is strictly adhered to, but the naturę of that development suggests that trance imagery is informing the visual language of coin, just as on coinage in many parts of Continental Europę.

Away from coinage there are two morę sets of supporting evidence. One is the development of late Insular British art, whilst the second relates to subsequent religious developments in Romanised Britain and Gaul. First Insular British ‘art’:

While Celtic an on the European mainland faltered in the first century BC, that of Celtic Britain and Ireland entered a period of remarkable flowering -developing and rediscovering elements of earlier Celtic styles. Compass design, largely abandoned in the fourth century on the continent, was wideły used in both Britain and Ireland. In England and Wal es extensive use was madę of basketry cross-hatching on bronze mirrors, scabbards and gold torcs. (Megaw and Megaw 1989:206)

Out chronologies for late Iron Age metalwork are impredse, but most of the bronze mirrors and gold torcs are usually dated to the first century BC, possibly continuing into the first half of the first century AD, with some of the torcs pcrhaps being earlier than some of the mirrors. If this is correct, then this new form of motif arrives at a similar time to or shortly aftcr the adoption of coinage and the resurgence of gold (Fig. 2.8). One of the motifs which Dronfield considered most diagnostic of trance imagery was the ‘fortification’ pattem. This was madę from a senes of chevrons, appearing on the inner curve of a cresccnt. Within the early stages of trances, phosphencs and entoptics tend to multiply, fragment and rotatc to form complex, constantly changing pattems, similar in many rcspccts to compass work and basketry cross-hatching. The engraving of such complex pattems on what we can presume to be polished metal would ądd a shimmering appearance to this image. The association with mirrors is particularly telling, as these are ofien associated with passages into othcr realms.

A second linę of argument rclating to the eacistence of shamanistic practices in MIA/LIA Europę comes from post-conquest Gaul. As Gallic culture changed and adopted the practice of making sculptural reliefs, we begin to find reliefs depicting various deities, which are collectively given the generał name ‘Romano-Celtic’ gods. Many havc inscriptions and dedications with them, and these principally include the deities, which are provided with both Celtic and Roman names (Lenus Mars, Sulis Mincrva, etc.). Howevcr, two sets of sculpture stand out: those of the couple

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

46870 S5004024 Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain 42 This effect was the primary driving lorce

S5004023 Coins and power in Lata Iron Age Britain 40 to have been taken over the colour of the early

S5004029 Coins and potuer in Late Iron Age Britain 52 and some other areas have only gone so far as

S5004019 Coins and power in Ute Iron Age Britain British A VA200:E4 Gold Gallo-Bclgic A VA12:SEl-3 G

S5004022 Coins and potuer in Late Iron Age Britain 38 not gold, was used for the consecradon of king

52457 S5004012 Coins aml power in Late Iron Age Britain H genders of the pardcipants are reversed fr

więcej podobnych podstron