232 233 (14)

METEOROLOG!' FOR MARINERS

232

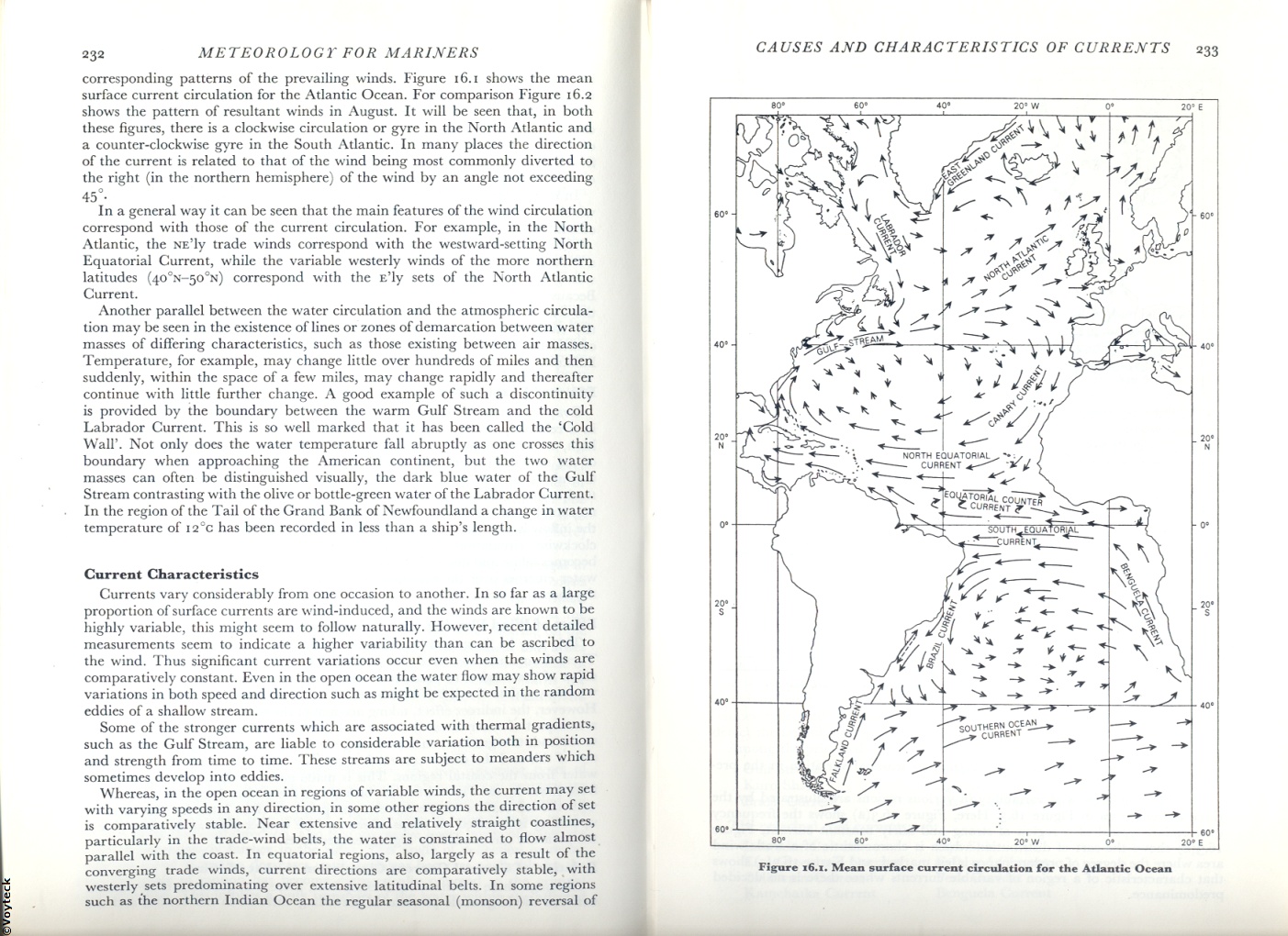

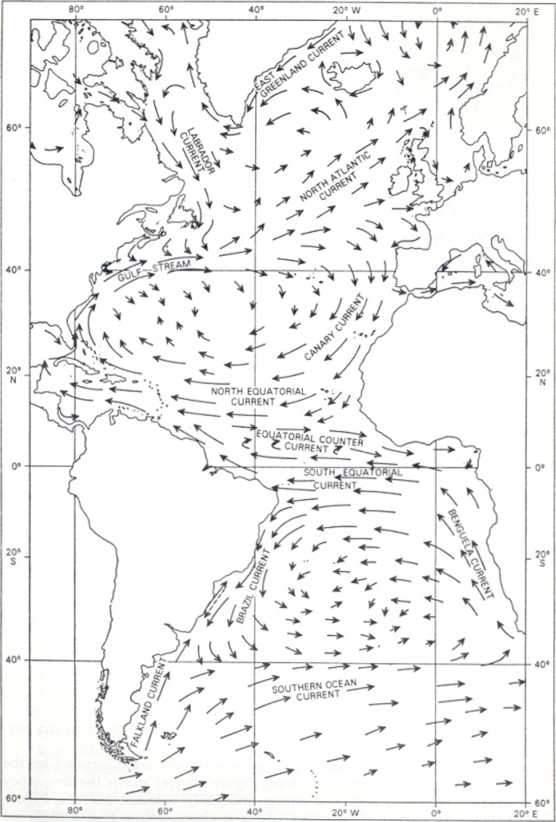

corresponding patterns of the prevailing winds. Figurę 16.1 shows the mean surface currcnt circulation for the Atlantic Ocean. For comparison Figurc 16.2 shows the pattern of resultant winds in August. It will be seen that, in both these figures, there is a eloekwise circulation or gyrc in the North Atlantic and a countcr-clockwise gyre in the South Atlantic. In many places the direction of the currcnt is related to that of the wind bcing most commonly divcrtcd to the right (in the northern hemisphere) of the wind by an angle not exceeding 45 °*

Ina generał way it can be seen that the main features of the wind circulation corrcspond with those of the current circulation. For example, in the North Atlantic, the NEłly trade winds correspond with the westward-setting North Equatorial Current, while the variable westerly winds of the morę northern latitudcs (40°n-50°n) correspond with the E’ly sets of the North Atlantic Current.

Anothcr parallcl betwecn the water circulation and the atmospheric circulation may be seen in the existence of lines or zones of demarcation between water masses of dilfcring characteristics, such as those cxisting betwecn air masses. Temperaturę, for cxample, may change littlc ovcr hundreds of miles and then suddcnly, within the spacc of a fcw miles, may changc rapidly and thcrcaftcr continue with little further change. A good example of such a discontinuity is provided by the boundary between the warm Gulf Stream and the cold Labrador Currcnt. This is so well marked that it has bccn callcd the ‘Cold Wall’. Not only docs the water temperaturę fali abruptly as one crosses this boundary when approaching the American continent, but the two water masses can often be distinguished visually, the dark blue water of the Gulf Stream contrasting with the olivc or bottlc-grccn water of the Labrador Current. In the region of the Taił of the Grand Bank of Newfoundland a change in water temperaturę of i2°c has becn recordcd in less than a ship’s length.

Current Characteristics

Currcnts vary considerably from one occasion to anothcr. In so far as a large proportion of surface currcnts are wind-induced, and the winds are known to be highly variable, this might sccin to follow naturally. Howcver, recent detailed mcasurcmcnts sccm to indicatc a higher variability than can be ascribcd to the wind. Thus significant current variations occur cvcn when the winds are comparatively constant. Evcn in the open ocean the water flow may show rapid variations in both speed and direction such as might be cxpccted in the random eddies of a shallow stream.

Some of the stronger currcnts which are associatcd with thcrmal gradients, such as the Gulf Stream, are liablc to considcrable variation both in position and strength from timc to time. These streams are subject to mcanders which sometimes dcvelop into eddies.

Whcrcas, in the open ocean in regions of variable winds, the current may set with varying speeds in any direction, in some other regions the direction of set is comparativcly stablc. Near extcnsivc and rclatively straight coastlines, particularly in the tradc-wind bclts, the water is constraincd to flow almost parallcl with the coast. In cquatorial regions, also, largcly as a result of the convcrging trade winds, currcnt directions are comparatively stable, with westerly sets predominating over cxtensive latitudinal belts. In some regions such as the northern Indian Ocean the regular scasonal (monsoon) rcvcrsal of

Figurę 16.1. Mean surface current circulation for the Atlantic Ocean

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

230 231 (14) METEOROLOGY FOR MARINERS 230 hcmisphcrc) of that of the surfacc laycr. Thus, with incre

234 235 (14) 234 METEOROLOG! FOR MARINERS Figurc 16.2. Mcan rcsultant winds ovcr the Atlantic Ocean

242 243 (14) 242 METEOROLOGT FOR MARINERS salt is deposited, leaving purc icc containing pockets of

244 245 (14) 244 METEOROLOGT FOR MARINERS they reach an advanccd State of dccay, break into smali pi

224 225 (16) METEOROLOGY FOR MARINERS 224 Extreme Eastern Part of the Ocean The currents here, inclu

228 229 (15) 228 METEOROLOGT FOR MARINERS ARCTIC OCEAN The main inflow of water into the Arctic Basi

236 237 (13) METEOROLOGY FOR MARINERS 236 In thc casc of some of thc cold currents the Iow temperatu

238 239 (12) METEOROLOGY FOR MARINERS 238 Formation of Ice Fresh water and salt watcr do not frcczc

248 249 (13) METEOROLOG! FOR MARINERS 248 Antarctic Bcrgs The breaking away of ice from the Antarcti

254 255 (11) 254 METEOROLOGY FOR MARINERS SEA ICE IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE Though sca icc extends

256 257 (10) 256 METEOROLOGY FOR MARINERS Distribution of Sea Ice at the Time of G

264 265 (10) METEOROLOG! FOR MARINERS 264 speed at the locality in qucstion but also upon the diffe

266 267 (10) 266 METEOROLOG! FOR MARINERS An cfTcct which is sometimes ovcrlookcd is that of atmosp

232

IMGs2 Ernst Mach clcctcd a corresponding mcmber of the Austrian Acadcmy of Science, the most importa

14:00-17:00i; i we? C5II IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SAS EL STATEMENTS - COUNTRY AND REGIONAl ACTIONS.

13 UN DEEat : les mentalitEs collectives 569 through the traditional corresponding planes of th

DIALOGUE CHARACTER ACTINC THIS 15 A MODEL SHEET FOR A PROFOSED ANI MATĘ D SERIES OF THE HONEYMGONER5

więcej podobnych podstron