GOSPELS

.GOSPELS

( a )

From the statement of Papias given above in

65,

Schleiermacher in 1832 first drew the inference

the apostle Matthew had made

Aramaic

a

collection only of the

sayings of Jesus.

Whether this is

what Papias really meant is question-

able, for undoubtedly he was acquainted with the

canonical Mt. and had every occasion to express

himself with regard to this hook as well as with regard

to

If he was speaking of Mt., then he was as

much in error

as

to its original language as he was

as to its author (see

this, however,

is

con-

ceivable enough. That by his logia Papias intended

the whole gospel of Mt., although this contains not

discourses merely but narratives

as

well,

is

not by any

means impossible (see

65,

n.

3).

In Greek, logia,

it is true, means only things said

the angel

which spake Rom.

32

oracles,’ etc.

)

but if Papias

took fhe word as

a

translation of Heb.

which he

readily have done,

on

his assumption of

a

Semitic original-then for him it meant ‘events in

general.’

( b )

The actual state of the case in Mt. and Lk., how-

ever, furnishes justification for the hypothesis to which

scholars have been led by the words of Papias, even

though perhaps only by

a

false interpretation of them.

A great number, especially of the sayings of Jesus

which are absent from Mk., are found in Mt. and Lk.

in such

a

way that they must be assumed to have come

from a common source.

If these passages were found

in absolute agreement in both gospels it would be

possible to believe that Lk. had taken them

Mt., or Mt. from ‘Lk. ; but in addition to close general

agreement the passages exhibit quite characteristic

divergences.

(c)

I n point of fact the controverted question as to

whether it is Mt. or Lk. who has preserved them in their

more original form must be answered by saying that in

many cases it is- the one, in many other cases the other.

Secondary in Lk for exam le are : 1 2 4 a s against Mt. 10

(prayer for the Holy Spirit), Lk.

against Mt. 2323 (the

generalisation ‘every herb

or 1144 the mis-

understanding that the

are like‘

because

they

not,’ and not because, a s

in

Mt.

23

they are

outwardly beautiful but inwardly noisome.

I n

Lk.

Mt.

5 38-48 Lk. makes love of one’s enemy the chief considera-

tion and introduces it accordinglyat the beginning

H e

betrays his dependence, however, by repeating it in

35 because

in the parallel passage Mt.

in

source), it is met with

in

that position. Cp

a.

On

the other hand

in

1326

(we did eat and

fits better with the

in which Jesus lived

Mt.

(Lord

ord

we not prophesy?).

I n Lk.

the

‘respect the person’

lit. ‘accept

the face ’)is retained, whilst in Mk. 12

22

16

the

changed.

On

Lk. 8

6

(other fell

on

the

rock)

see

end on

a.

I n

the Lord’s Prayer the text of Mt.

has

is distinctly the more original on the other hand

the clauses which are not found in Lk. may have been

afterwards (see

and the maxim in

also

L

ORD

’

S

P

RAYER

).

A

conclusion-the existence of

a

source used

in common by Mt. and Lk. but different from

indicated by the doublets, that is to

say the utterances which either Mt.

or

Lk.,

or

both, give, in two separate

two sources.

( a )

In the majority of cases it can be observed that

in Mt. the one doublet has

a

parallel in Mk. and the

other in Lk. I n these cases it is almost invariably found

I n what follows, we use the word ‘logia’ (because it has

become conventional) in both senses (‘sayings’ alone, and ‘say-

ings and narratives’) throughout, even if the authors to

we have occasion to refer, prefer another word. This is specially

desirable when they simply say ‘the source,’

we must allow

for the possibility of several sources for the synoptic gospels.

In Mk. there are only two passages that can be called

(‘if any man would be first

and

(‘who.

soever would become great

on which see

;

for 9

I

there be some

and

(‘gospel first preached’) can

hardly be so classed.

For

doublets cp Hawkins 64.87, Wernle

(in neither is

the

enumeration complete).

that in the parallel with Mk. not only the occasion b u t

also the text

is

in agreement with

and in the parallel

with Lk. occasion and text are in agreement with Lk.

Similarly,

wherever there is

a

doublet, is found t o

agree in the one case with Mk. and in the other with Mt.

If

it must be conceded that in many cases the agreement

of text is not very manifest, this is easily accounted for

by the consideration that the evangelist (Mt. or Lk.)

in writing the text the second time would naturally

recall the previous occasion

on

which it had been

The passages, however, in which the observation made

above holds good are many

To

account

for

them without the theory of two sources would, even

apart from these special agreements, be extraordinarily

difficult,-indeed possible only where an epigrammatic

saying fits not only the place assigned to it in what is

assumed to be the one and only source, but also the

other situation into which the evangelist without follow-

ing any source will have placed it.

I n some places indeed this would seem to be what we must

suppose to have actually happened, as we are unable to point to

two

different sources.

So

self shall be abased’)

;

or the quotation from

Hos.

66 (mercy n o t

sacrifice) in

(which, moreover ‘is not very ap-

propriate in either case).

It must be with

intention

that the preaching with which, according to Mk.

(the time

;

Jesus began his ministry is in

already

assigned to

Baptist or the binding and loosing

136) to

Peter. On the other hand, the answer

I

know you not’ which

follows the invocation ‘Lord, Lord’ in

(many will

say) and 25

(five virgins) is associated with a different narra-

tive in the two cases and cannot therefore, properly, he regarded

a s an independent

so also

with the threatening

with

fire

But, in other cases, such

a

repetition of

a

saying,

on

the part of a n evangelist, without authority for it in

some source in each case, is all the more improbable

because Lk. often, and frequently also Mt. (see,

or the omission of Mk.

8

38

9

26

after

Mt.

1626

on account of Mt.

1033).

avoids introducing

for

the second time

a

saying previously given, even when

the parallel has it, and thus

a

doublet might have been

expected

as

in the cases adduced a t the beginning

of

this section.

Were this not

so,

we should expect that Lk.,

before him

ex

hypothesi

the same sources as Mt., would

in every case,

or

nearly every case,

a

doublet

wherever Mt. had one and vice

As

a

matter

of

fact only three or

sayings

are

doublets in Mt. as

well

as

in Lk. ; on the other hand, although the

derivation of

a

passage from the logia

is

not always free

from doubt, we are entitled to reckon that Lk. has seven

doublets peculiar to himself, and Mt.

many.

(6)

W e are led

to

the same inference-that two

sources were employed-by those passages common to

the three Gospels in which Mt. and Lk. have in common

certain little insertions not to be found in Mk.

as, for

example, Mt.

as compared

with Mk.

or

Mt.

(baptize with

as

compared with Mk.

at

the close of which

passage both even have in common the words and with

fire

Another very manifest transition from

one source to another is seen in the parable of the mustard

seed. This

is

given in the form of

a

narrative only in

Lk.

in Mk.

on the other hand, in the

form of

a

general statement.

Now, Mt.

has in

For example Lk. 11 33 (lamp under bushel) agrees much

more closely with 8

16

(under bed)

with its proper parallel

in

Mt.

5 1 5 ;

but Lk.

agrees just a s closely with its proper

parallel in Mk.421 as it does with Lk.1133.

C p further,

especially, Mk. 35 (save life, lose

9

24

from

which the other two parallels, Mt.

17

33, are

guised

common

only by the use of

instead of

(whosoever

everyone

Mt.

or

Mk.

(last.

or’

11

:

(faith‘as

17

6

or Mt.

21

Mt.

7

(ask) = Lk. 11

or

Mk. 4

Lk.

12

(covered up

or

Lk.129

(denieth,

1624;

Lk. 1427 (bear

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

the

one half narrative, in the other general state-

ment.

In

short, the so-called theory of two sources,-that is

of the employment by Mt. and Lk. of Mk. (or original

Mk.) on the one hand, and of the logia on the

ranks among those results of gospel criticism which

have met with most general acceptance.

If the original Mk. was more extensive than the

canonical, possibly it contained things which,

on

another assumption, Mt. and Lk.

might he supposed to have taken

from the logia.

In

particular has

this been asserted of the centurion of

Capernaum (Mt.

85-13

Lk.

of the detailed

of the temptation (Mt.

41-13),

and

also of the Baptist's message (Mt.

11

2-19

Lk.

the logia being held to have been merely

a

of

discourses.

At present it

is

almost universally con-

ceded that in any such collection the occasions of the

discourses included must also have been stated in nar-

rative form.

This once granted, it is no longer possible

to deny that, in certain circumstances, even narratives

of some length may have been admitted, if only they

led

up

to

some definite utterance of Jesus.

B. Weiss

and, after him, Resch

have

even carried this thesis

so

far

as

to maintain that the

logia formed

a

complete gospel with approximately

as

many narratives

as

discourses.

A definite separation of the portions derived from the

logia might be expected to result from linguistic investi-

gation.

B.

Weiss has in point of fact sought with

great care to determine the linguistic character of the

logia hut his argument is exposed to a n unavoidable

source of error, namely this, that the vocabulary of the

logia can be held to have been definitely determined

only when we have already, conjecturally, assigned

definite passages to this source.

I n so far

as

this provisional assignment has been a t fault, the

resultant vocabulary will also have to be modified.

Such

a

can never be accepted otherwise

than conditionally-for this reason, besides the reasons

indicated above, that it would be necessary first to de-

termine whether it is Mt. or Lk. that has preserved the

logia most faithfully.

The task, moreover, is rendered

difficult, by the fact that Mt. and Lk. by no

means adopt their sources without modification

they

alter freely and follow their own manner of speaking

instead of that of their source, or allow themselves to

be influenced by Mk. even in pieces borrowed from the

logia and

vice

versa.

It

is specially interesting

to

notice that Titius,

a

disciple of B.

Weiss, expressly acknowledges the unprovahleness of his

master's hypothesis

as

a

He calls it 'an equation with

many unknown quantities. Nevertheless he thinks he

can

prove it 'quite irrefragably' if

it

he restricted

to

the discourses.

This has theappearance

of

sounder method, for greater unanimity

prevails as

to

the extent

of

the discourses which belonged

to

the logia (Wernle,

91 187).

At the same time, even when this

restriction

has

been made, the difficulties that hare been urged

hold good, and

all

the

more

so

since

at

the

outset assigns

too

large

an

extent

to

the logia and also, what

is

more serious,

in

his verbal statistics makes

a

number of assumptions of

a

kind

that are quite usual but

also

quite unjustifiable.

It was

there-

fore

an exceedingly hold step when (amongst others)

B.

Weiss

Wendt

(Die

First

Part,

Resch

(Die

and Blair

Gospel,

1896)

printed the logia,

or a

source

similar to them

Hawkins

came

to

the conclusion that

linguistic methods no trustworthy separation of

the

logia-

portions could

he

made.

T h e divergences between Mt. and Lk. in the

common

to

the two but not shared bv Mk.

See further

.

-

Sp

eci

a

l

(I

a)

are often

so

great that it be-

comes a question whether both have

been drawing. from one and the same

source.

If it be assumed that they were, then one

or

other of them, or both, must have treated the source

with

a

drastic freedom that does not accord well with the

verbal fidelity to their source elsewhere shown by them

I t

is

the Ebionitic passages, chiefly, that

come

into

consideration ,here. According

to

Lk. derived them from some source.

Now, this source

must have had many

in common with the

logia

pre-eminently, the beatitudes,

as

also Lk.

(lend, hoping for nothing again);

1 1 4 1

('give for

alms')

('sell

. . .

and give alms').

In

it has further been shown to he probable that it

was

not Lk. himself who was enamoured of Ebionitic ideas.

All the more must they already have found

place in

the edition of the logia which he had before him.

( b )

The hypothesis of a special source for Lk. must

not, however, be stretched to the extent of assuming

that everything Lk. has from the logia had come to

him only in Ebionitic form.

Much of his logia material

is free from all Ebionitic tendency, yet it is not likely

that the Ebionitic editor who often imported his ideas

into the text

so

strongly would have left other passages

wholly untouched. Slight traces of an Ebionitic

perhaps can be detected in Lk.

whosoever

renounceth not

all'),

(bring in the poor) (cp

13

bid the poor),

6

36

(

merciful,

18

(

sell

all,'

19

8

(half of my goods). But that Lk. had

access to, and made use of, the unrevised logia

also

can hardly be denied.

(c)

All the more pressingly are we confronted with

the question whether

Ebionitic source of Lk. con-

tained also those passages which are peculiar to Lk.

This

is

at once probable

as

regards the parables

in

fact, for the parable of the

Rich Man and Lazarus, a t least

its Ebionitic shape

without the appendix

vv.

27-31

see

it is possible to conjecture a n original form of

a

purely ethical nature which characterised the Rich

Man

as

godless and Lazarus

as

pious, and thus

a

place (along with the beatitudes)

the logia, and

may have come from the mouth of Jesus. On the other

hand, such pieces as the parable of the Prodigal Son

of the Pharisee and the Publican

of

the unprofitable servants

on account of their

wholly different theological complexion, cannot possibly

be attributed to the same Ebionitic source.

For this

reason alone, if for no other, it becomes impossible to

suppose that Lk. had

a

special source for his account

of the journey of Jesus through Samaria

( 9

14)

this narrative, too, has some things in common with

Mk., others with Mt.

W e are

led to the con-

clusion,

so

far

as

Lk. is concerned, that he had various

other sources besides Mk.

(or

original

con-

clusion that is, moreover, in

with his own

preface.

Short

Narratives.

-Going much beyond the

results embodied in the foregoing section

Schleiermacher,

as

early

as

1817, assumed

a

series of quite short notes

on

detailed

events which, founding (incorrectly)

on

Lk.

1

I

n.

he called 'narratives'

On the analogy of

OT

s i n

this might be called the

fragment-hypothesis.' That

present gospels should.

have been directly compiled from such fragmentary

sources, as Schleiermacher supposed, is not conceivable,

when the degree in which they coincide in matter and

arrangement is considered

116

a ) .

As subsidiary

sources, however, or

as

steps in the transition fi-om

merely oral tradition to consecutive written narrative,

The two forms

in

which

these

are found admit

of

explanation

most easily if

we

assume

that

' i n

spirit'

;

Mt.

5

3)

and 'righteousness

Mt.

56)

were

originally

absent. The Ebionitic source-and, with

it,

in

this

case preserved the

tenor

of the

words with the greater fidelity

hut

Mt.,

his insertions, has better preserved the religious and

ethical meaning in which unquestionably Jesus spoke the words

-perhaps also by the addition of unambiguously moral

utter-

ances such as

(pure

in

heart, peacemakers) which with

equal certainty

can

be attributed to Jesus, and

7

(mourn

merciful). Both these

are

wanting in

Lk.,

although they

capable

of

used in

an

Ebionitic sense if he had chosen

to

take meek

in

the sense

of Ps. 37

and

'

merci-

ful

in that

of Lk.

11

41.

1856

[Cp

GOSPELS

the possibility of such brief notes can by no means be

disregarded (see

d ) .

Still,

to

show that they ex-

isted is by no means easy.

(6)

The

'-Nevertheless, the belief

is

continually gaining ground that into Mt.

24,

into

Mk.

13,

and (only with greater alterations) into

Lk.

21

a work often called the 'Little Apocalypse' has been

introduced.

The evidence of this is found

the first instance in

the want of connection.

'These things'

in Mt. 2433

21

coming as the phrase does after 71.31,

refer to the end

of the world; yet originally it must have

the pre-

monitory signs of the approaching end, for it is said that when

the beholders see

'these things,' then they are to know

that

'nigh.

Lk. 21 29-31) is not in its proper place here. On the other hand

Mt.

comes appropriately enough after

Mt.

Mk. 13

speaking as does of a tribulation,' does not come

in well after the discourse about false Messiahs and false prophets

in

Mt.

parallel to which in Lk. is

actually found

another chapter

23

would be ap-

propriate after Mt. 24

13

where

the connection is excellent.

21

occurs also in Mt.

in a form which, a s suiting

Jewish circumstances better

(10

'in their synagogues they will

scourge

must be regarded a s the more original

;

it is to

be regarded a s

of place in chap. 24. On the other hand,

abomination of desolation,' Mt.

comes

fittingly after

7171.

As for

71.

5

it belongs, so far a s itssubstance a t least

concerned, to the passage,

23-28, which we have already

seen isoutofplacehere.

not

fit well with

15

Mk. 13 14) where only a desecration,

not a destruction, of the temple is thought of (otherwise in Lk.

21 20-'when y e shall see Jerusalem compassed'-on which

see

Regarded a s a unity, accordingly, the passage

would consist of Mt.

15-22

14-20

As

adiscourse of Jesus it is prefaced by v.

21

introduction which anticipates v. go-and if

you will h y v .

and

is

brought to a

close in

35 ( = Mk.

21

33).

In contents, however, the passage is quite alien from

Jesus' teaching as recorded elsewhere, whilst on the

hand it

closely related to other apocalypses.

I t will, accordingly, not be unsafe to assume that an

apocalypse which originally had a separate existence

has here been put into the mouth of Jesus and mixed up

with utterances that actually came from him.

The

most appropriate occasion for a prophecy concerning

a n abomination about to be set up in the temple

(24

would be the expressed intention

of

the emperor

in 40

threw the whole Jewish

into the greatest excitement-to cause a statue

of

himself to be erected

The origin of this apoca-

lypse will best be placed somewhere between this date

and'the destruction of Jerusalem, which is not yet pre-

supposed in Mt.

24

Whether it was composed by a

Jew or by a Christian is an unimportant question (see,

however,

( c )

other minor sources that

have been conjectured mention may here be made

of the so-called anonymous gospel found by Scholten

in

19-22

.other words, in the main, the passages mentioned at

the beginning of

of the book which is held

to

be cited by

Lk.

under the title of 'Wisdom'

( d )

Buddhistic

(

1882;

' 8 4 ;

'97) has not actually

attempted to draw

up

a gospel derived from Buddhistic

material

but the parallels he has adduced from the

life of Buddha are in many places very striking, at least

so

far as the story of the childhood of Jesus is

and his proof that the Buddhistic sources are

5 9 ;

10;

8

I.

end, p.

To the

(Mt. 1

IS

), the annunciation to Mary

(1

the star (2

the gifts (2

(Lk.

the incident a t twelve years of age (Lk. 2

must be added

also the presentation in the temple; and here

it

is worthy

of

remark that such a presentation was not actually required either

by the passage

(Ex.

13

cited in Lk. (2 22-24)

or

yet by

t h e

passages Nu. 3

46

18

Ex.

22

See

I

SR

A

EL

96.

older than the Christian must be regarded as irre-

fragable.

The

Problem is

so

complicated that

few students, if any, will now be found who believe a

solution possible by means of any one

of

the hypotheses described above with-

out other aids. The need for combining

several of them is felt more and more.

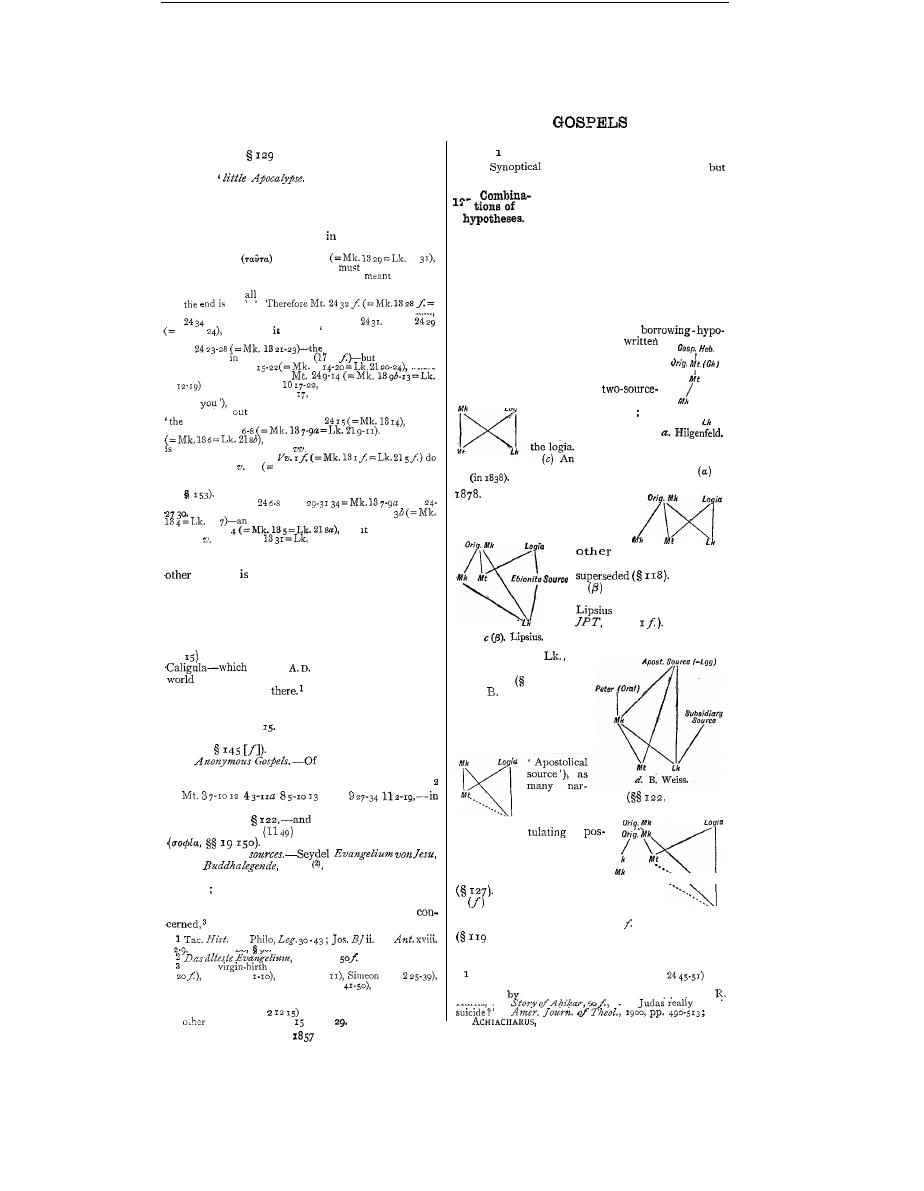

Most frequently, we find the borrowing-hypothesis com-

bined with the sources-hypothesis in one form or another,

and, over and above, an oral tradition prior to all written

sources assumed. Instead of attempted detailed accounts,

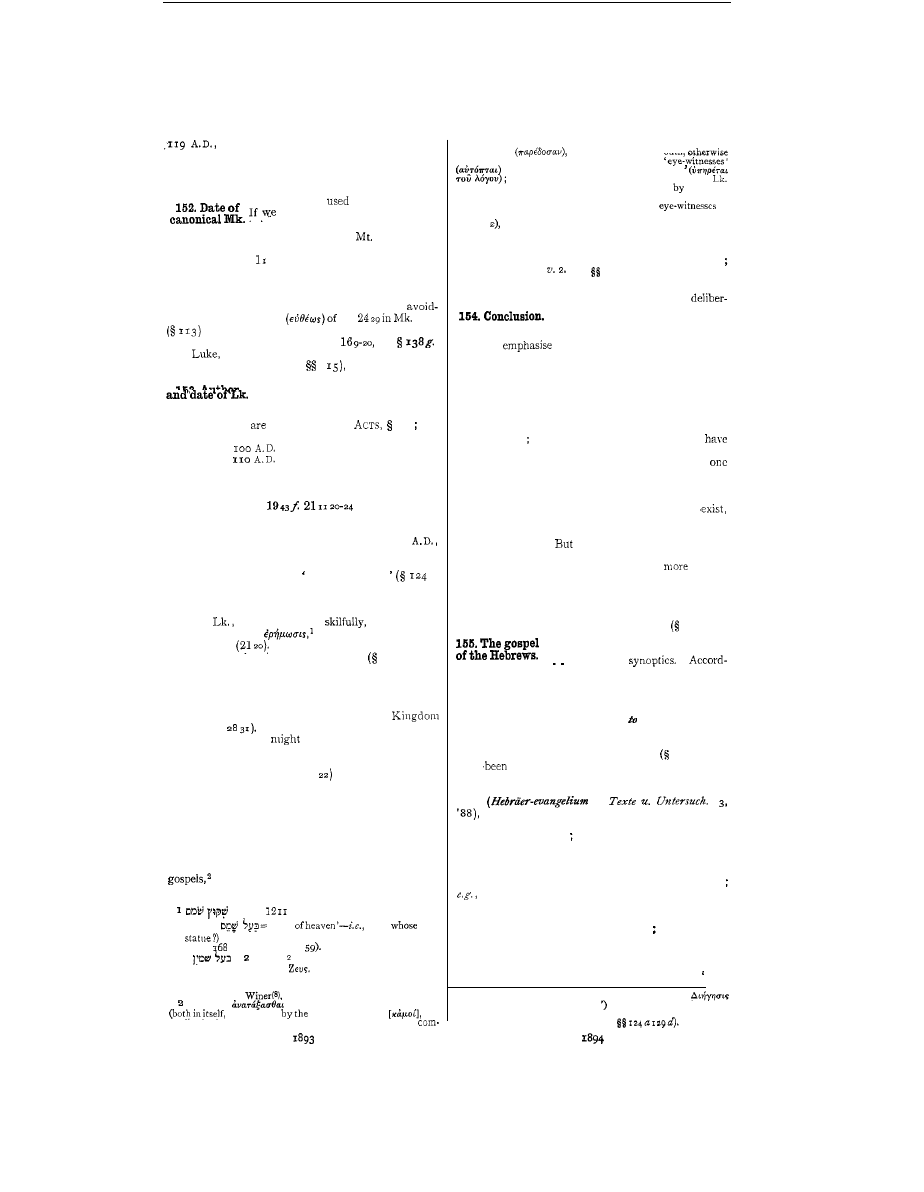

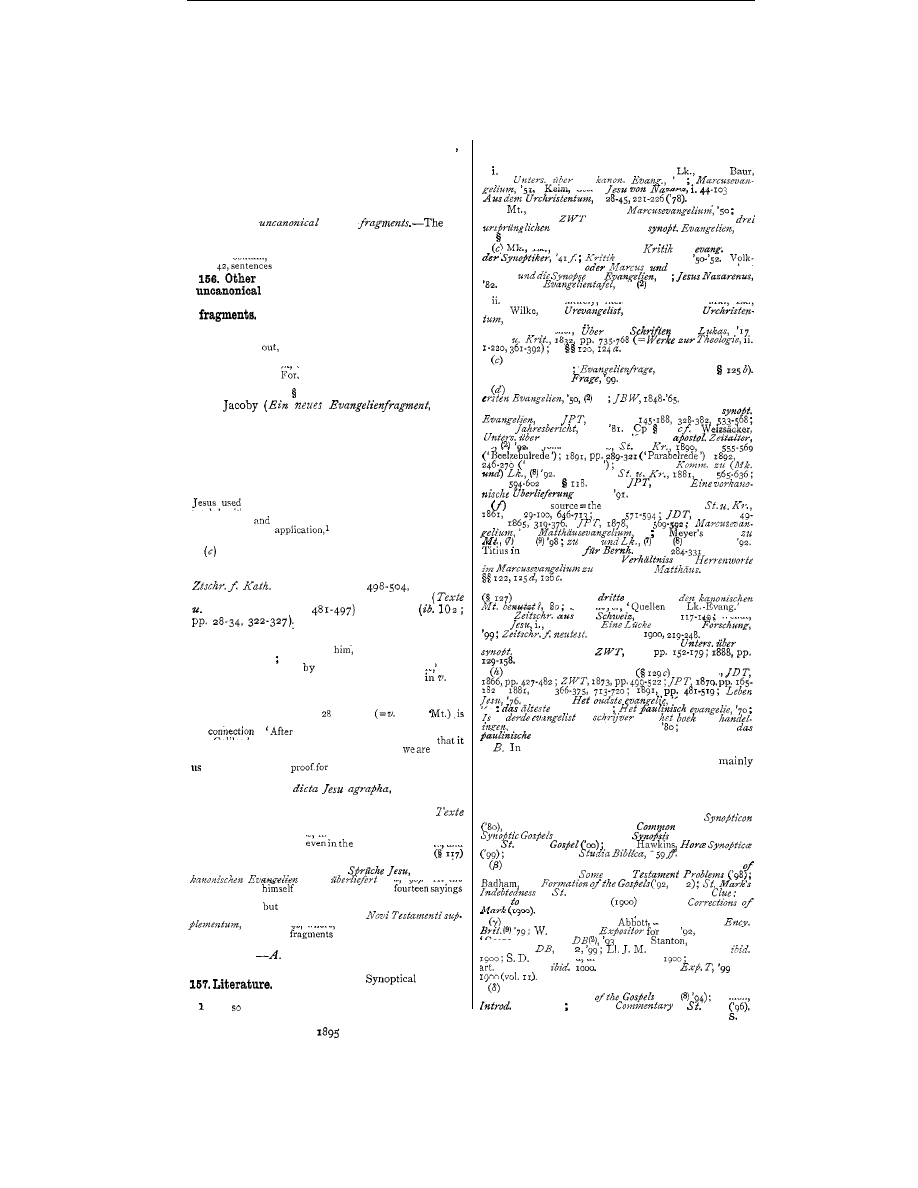

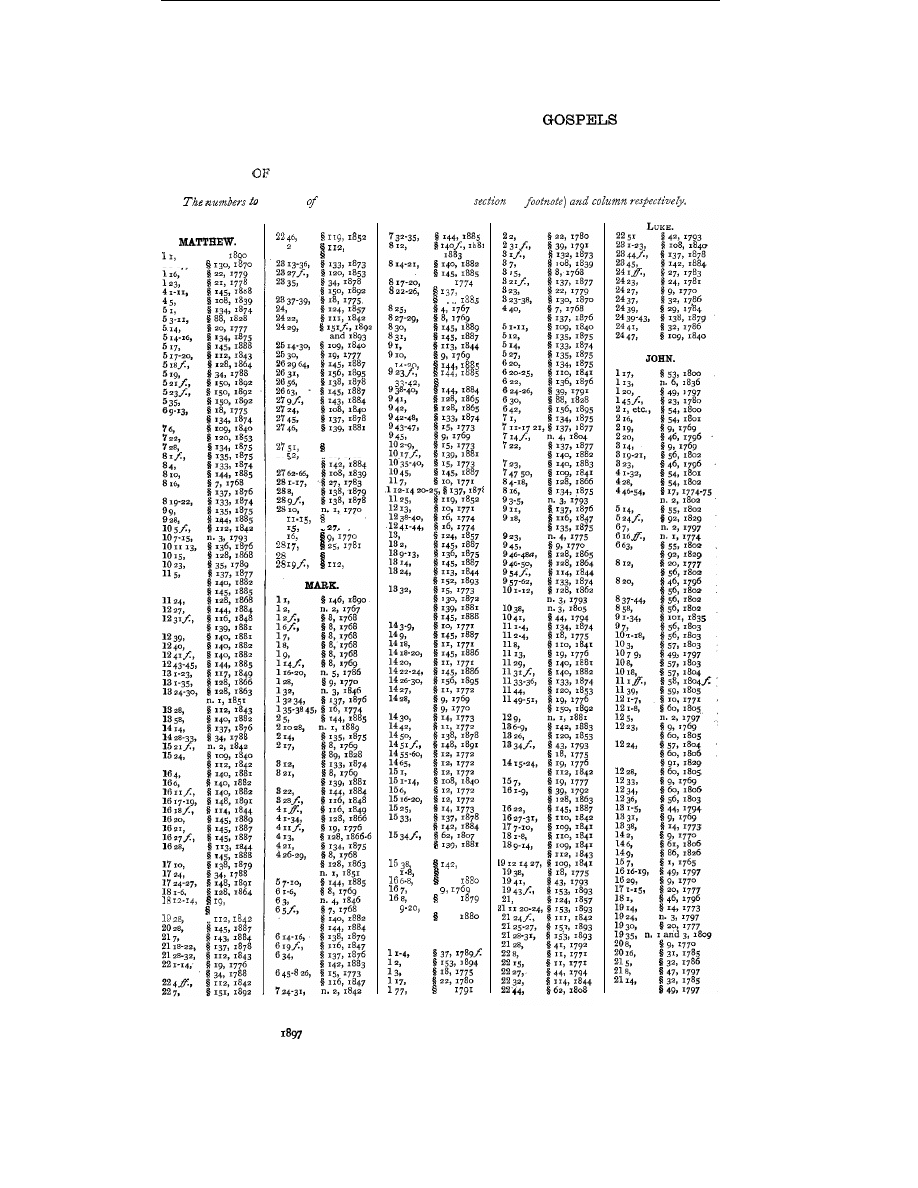

we subjoin graphic representations of some combina-

tions which

are

not too complicated and which bring into

characteristic prominence the variety that exists among

the leading hypotheses.

( a )

Hilgenfeld combines with the

thesis the further assumption of a

original gospel in two successive stages,

Hebrew and Greek

(so

also Holsten, only

with omission of the first stage),

(6)

The simplest form of the

hypothesis was argued for

\

by Weisse in 1838

in

\

an original

Mk.

along with

1856, however, heassumed

Mt

original

Mk.

alongside of the

Z.

Weisse

logia was postulated as

a

source

in

simple form by Holtzmann down to

The borrowing-hypothesis

in its purest state-the theory,

namely, that

one

canonical gospel

had been

used

in the preparation

O f

t h e

-

c

(a).

Holtzmann

was thus

(before 1878).

As

a more complicated

form

we

single out that of

(as

described by Feine,

'85, p.

Inaddition

to Holtzmann's scheme he

assumed a borrowing from

canonical

Mk.

by

and

also an Ebionitic redaction

of the logia

123).

( d )

Weiss reverts al-

most to the hypothesis

of

an original gospel.

He

postulates for the logia

(which he therefore prefers

to call the

ratives as discourses

126

c).

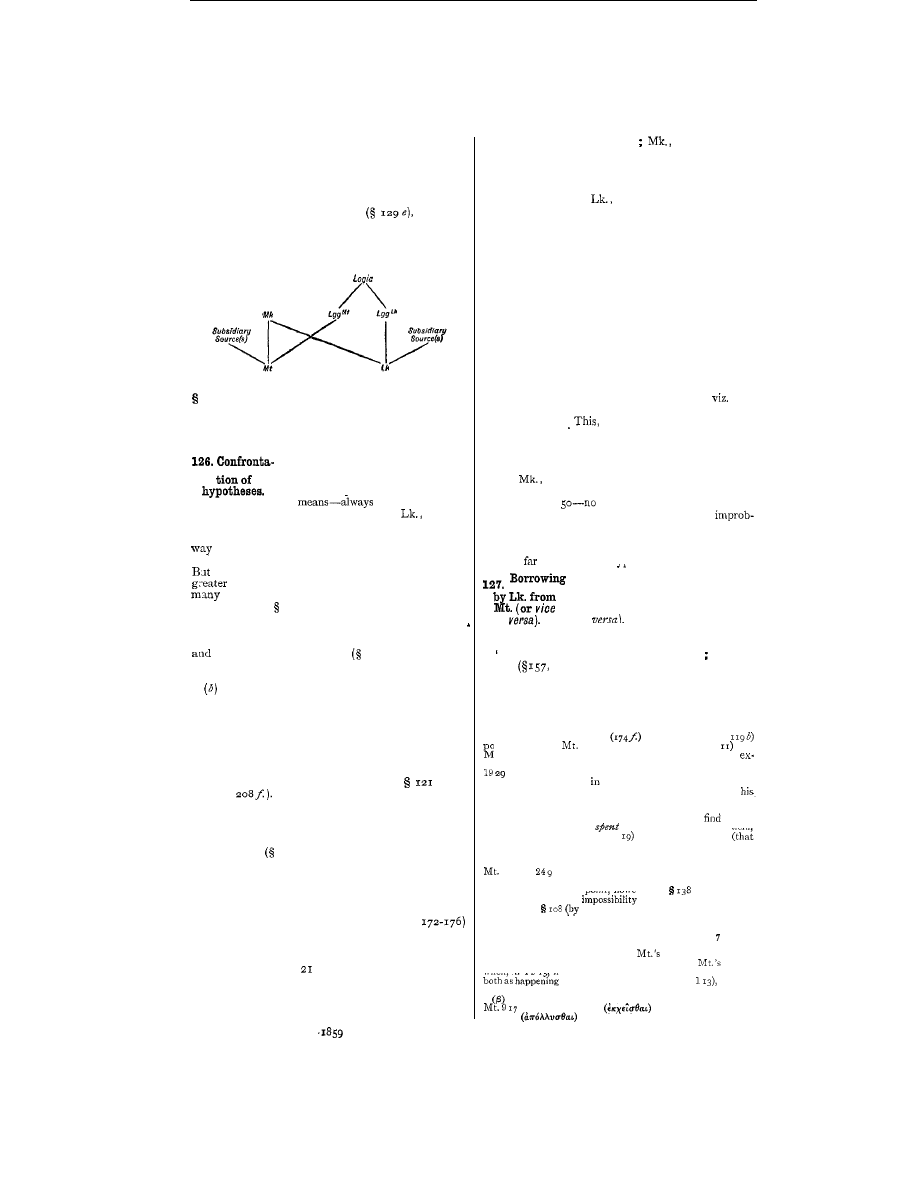

( e ) Simons essentially simplified the

e.

Simons.

sources by (what

Lh

theory of two

all the hypotheses hitherto enu-

merated had avoided doing)

a

borrowing by

Lk.

from

Mt.

Holtzmann from 1878

combined this last with the

hypothesis

of

an original

Mk.

Lh

Holtzmann (1878).

a).

(g) The latest form of the two-source-theory is ihat

propounded by Wernle. Whether Mt. and Lk. severally

Only the parable

of

the Wicked Servant

(Mt.

and,

indirectly, the narrative of the end of the betrayer (Mt. 27 3-10)

are affected

the resemblance to the story of Ahikar; cp

J.

Harris

The

'Did

commit

in

and

see

I

.

1858

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

used one or more subsidiary sources he leaves an open

question. With regard to the logia he assumes that

before they were used by Mt. and Lk. they had under-

gone additions, transpositions, and alterations-yet not

to too great an extent-at the hands of a transcriber

or possessor.

T h e copy which Mt. used had been

worked over in a Judaistic spirit

that used

by Lk. was somewhat shorter.

Mk. was acquainted

with the logia, but did not use them; he merely took

them for granted as already known and on that account

introduced all the fewer discourses (against this see

g.

Wernle.

148).

Our present Mk. is different from that used

by Mt. and Lk. but only by corruption

of

the text,

not by editing.

I t

is

the agreement between Mt. and Lk. as compared

with Mk. that tries any hypothesis most severely, and

it is with reference to this point that

all the most important modifications

in the various theories have been

made.

W e proceed to test the lead-

ing hypotheses by its

on the presupposi-

tion that neither Mt. was acquainted with

nor Lk.

with Mt.

( a )

T h e hypothesis

of

an original Mk. is in

a

general

very well fitted to explain the agreement in question

in so far as canonical Mk. is secondary to Mt. and Lk.

if, on the other hand, our Mk.

has

elements of

originality, as we have seen to be the case with

of his exact details, then one will feel inclined, in

accordance with

3,

to suppose that it was

a

younger

copy of Mk. that Mt. and Lk. had access to.

fact, however, sometimes the one condition holds good,

sometimes the other.

It is in this textual question, over

above the question already

118)

spoken

of

as to

its extent, that the difficulty

of

the original-Mk. -hypo-

thesis in its present form lies.

If

certain passages which are found in Mk.

occurred also in the logia, then Mt. and Lk. may have

derived their representation, in

so

far as it differs from

Mk., from the logia, provided that the logia was unknown

to

Mk.

That there were passages common to Mk. (an

original Mk. is not required when we approach the

question as we do here) and the logia is at least

shown by the doublets, and is by no means excluded

even where there are no doublets (see

6

and

Wernle,

One, however, can hardly help think-

ing that the great degree of verbal coincidence which

nevertheless is seen between Mk. on the one hand and

Mt. and Lk. on the other comes from oral tradition. Thus

a

very high degree of confidence in the fixity of the oral

narrative type

115)

is

required, and this marks one of

the extreme limits to which such hypotheses can be

carried without losing themselves in what wholly eludes

investigation.

But, moreover, the logia must be con-

ceived of as a complete gospel if we are to suppose that

it contained all the sections in which Mt. and Lk. are

in agreement against Mk.

Hawkins (pp.

reckons that out of

58

sections which almost in their

whole extent are common to the three evangelists there

are only 7 where Mt. and Lk. are not in agreement

against Mk., and in

of

the remaining 51 he finds

agreements which are particularly marked and by no

possibility admit of explanation as being due to

chance.

(c)

According to

B.

Weiss

not

only Mt. and Lk.

but

In actual

also Mk. made use of the logia

over and above,

drew upon the

oral

communications of Peter and was

again in his turn used by Mt. and Lk.

This hypothesis

has the advantage of accounting for the secondary

passages of Mk. as due to a more faithful reproduction

of the logia by Mt. and

and the fresher colours of Mk.

as due to the reminiscences of Peter.

It still remains

surprising, doubtless, that Mt. and Lk. should have

omitted so many of these vivid touches if they lay

before them in Mk.

T h e supposition that they did

not regard Mk. as

of

equal importance with the logia is

not in itself inherently impossible; but it does not

carry

us

far, for they elsewhere take a great deal from

Mk.

Still more remarkable is it that Mk. should have

omitted

so

much from the logia. T h e suggested ex-

planation that in writing down the reminiscences of

Peter he regarded the logia as only

of

secondary value

is, in view of the number of passages which according

to Weiss he took from them, still more improbable

almost than that already mentioned.

As

regards the coincidences between Mt. and Lk.

against Mk., a very simple explanation seems to be

found for them in the hypothesis of Weiss,

that

Mt. and Lk. drew upon the logia with greater fidelity

than Mk. did.

however, can

of

course be

claimed by Weiss only for those sections which he

actually derives from the logia. Yet for one portion of

the sections in which such coincidences occur (see

above,

6 )

he finds himself compelled by his principles to

regard

not the logia, as the source of Mt. and

Lk.

In this way, of the

240

coincidences enumerated by

Hawkins, some

inconsiderable number-remain

unaccounted for.

Nor can we overlook the

ability that the logia, as conceived of by Weiss, should

have contained, as he himself confesses, no account

of

the passion.

In

so

as the various hvuotheses referred to in the

preceding section are found to be in-

sufficient, in the same degree are we

compelled to admit that Llc. must

have been acquainted with Mt. (or

vice

(a)

Each of the two assumptions-partly without any

thorough investigation and partly under the influence of

a

tendency’ criticism-long found support

but the

second

Ai. c)

has at present few to uphold it. T h e

other has for the first time been taken

up

in a thorough-

going manner with use

of

literary critical methods

by

Simons

($125

e).

We begin with arguments of minor weight.

(a)

Out of the selection of specially strong evidences in sup-

port of it given in Hawkins

we have already (#

ointed out that

13

11

Lk. 8

IO

(as

against Mk. 4

and

t. 2668 Lk. 2264 (as against Mk. 1465) admit of another

planation. Similarly, the ‘Bethphage and Bethany’ of Lk.

may be sufficiently explained by assuming that originally

only the first word stood

the text (as in Mt. 21

I

)

or only the

second (as in Mk. 11

I

), and that it was a copyist who, of

own proper motion, introduced the name he found lacking.

Possibly we ought to trace to the source of Mt., rather than to

the canonical Mt., such material divergences as we

in

Mt.

21

17 Lk. 21 37 (that Jesus

the night outside of Jerusalem

a statement not found in Mk. 11

; in Mt. 21 23 Lk. 20

I

Jesus taught in the temple, as against Mk. 11 27 ‘he was walking

in the temple’); in Mt. 2650 Lk. 2248 (that Jesus spoke to the

betrayer in the garden-a statement not found in Mk. 1445); in

288 Lk.

(that

the women reported to the disciples the

angel’s message, whereas according to Mk. 168 they said nothing

to any one ; on this last point however, see

e).

Similarly,

the representation, the

of which has already been

referred to

in

which the

Baptist

is made to address the

penitent crowds flocking to his baptism as a generation of vipers)

is either due to an infelicitous juxtaposition of Mt. 3 5 (where it is

said that the multitudes went out to him) and Mt. 3 (where

the words in question are addressed to the Pharisees and Sad-

ducees); or it may be due to use of

source. Lk. appears

to be dependent at once on Mk. and on

Mt.

(or

source)

when in 4 2-13 h e represents the temptation in the wilderness

during t h e forty days (as in

Mk.

and also

as happening after their expiry

(as

in Mt.

42-11).

In

Lk.537 ‘spilled’

is used of the wine

‘perish’

only of the bottles;

in

Mk.

222 ‘perish’

1860

Greater importance belongs to the verbal agreements.

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

is used of both. I n

9

Lk.

8 44 the woman

touches the hem of the garment of Jesus in Mk. 5 27 simply the

garment. I n Mt.

I

Lk. 9 7 Herod

is

correctly called

tetrarch, in Mk. 614

and also

inexactly

‘king’

Mt. 19 29 Lk. 18 30 have

Mk. 10 30 ‘a hundredfold’

In

Mt. 26 75 Lk. 22

it is said of Peter ‘ h e went out and wept

in

‘ h e began

to

weep’

In

Lk. 2353 it

is

said of Joseph of

‘ h e wrapped it in a linen cloth

. .

.

and laid

.

.

.

Mk.

46

wound him in a linen cloth

. . .

and laid’

Mt. 28

I

Lk. 23 54 have,

as against Mk.

‘it began to dawn’

indeed, in a different connection. In Mt. 28 3 Lk. 244,

Mk. 16

5 ,

the countenanceof the angel, or the apparel of the two

A

material divergence from Mk., but a t the same time an

approach to coincidence of expression is seen in Lk.

where

the answer of Jesus to the high

given in this form : ‘Ye

say that

I

am.’ T h e first two words are a paraphrase of the ‘thou

said’

of Mt. 26 64

;

the remainder of the sentence

is a repetition of the paraphrase in Mk.

For another

material divergence from Mk. see Lk. 11 17

=

12

25

as

against

Mk. 323 (Jesus knowing the thoughts of his enemies).

) Specially important are cases

which a casual expression

of

is laid hold of.

for example, in Lk. 9 34 while he

said these things

as

compared with

17

(‘while be was yet

speaking’), and as against Mk.97. Similarly Lk.

(4

16-30)

was

able to find a justification for his erroneous

that Jesus

had come forward in the synagogue a t Nazareth at the very

of his

activity (cp

39,

in Mt. 4

where it is said that Jesus before coming to Capernaum left

Nazareth (in Lk.

he comes to Capernaum from Nazareth).

The scribe’s question as to the greatest of the commandments is

described not by Mk. (12

but only by Mt. (22 35) as having

been asked for the purpose of ‘tempting’ Jesus.

According to

Lk. 10 25 the questioner asks what he must d o to inherit eternal

life. Nevertheless h e too is represented a s having sought to

‘

tempt’ Jesus.

Lk. 16

would be specially convincing on the

present point if here a sentence had been taken over from the

latest hand of Mt. (5

But the original text of Lk. probably

said the opposite (see

On the other hand, we really

have a sentence by the latest hand in Mt.

with which Lk.

7

I

betrays connection, for with the formula ‘When Jesus had

ended all these words,’ Mt. concludes his

not only here, hut also in four other places (11

I

13 53

I

26

I

).

Moreover, Lk. also shares with

the statement that

the multitude heard the preceding discourse, though this is con-

tradicted by the introduction to it in Lk. 6

as

well a s in

Mt.

Mk. says in 1218 correctly ‘There came unto him Sad-

ducees,

who

well known] say that there

is no resurrection

Mt. 22 23 infelicitously reproduces this as

‘there came unto him Sadducees saying

that etc.

Lk. 2027 seeks to improve this: ‘There came to him

of

the Sadducees, they which say

that there is no

resurrection, and they asked him, saying.

ought

to

have been in the genitive

In the nom.

we seem to have an echo of

Lk. rightly inserts the article missing in Mt.

reference, however, must he to the Sadducees, not to certain

T h e formula, while he was saying these things (see

above, Lk. 9

is met with also in Lk. 11

37,

where Jacohsen

would derive it from Mt. 12 46 as also he would derive the state-

ment in Lk. 12

,‘When the myriads of the multitude

gathered together insomuch that they trode one upon another

(which indeed does not fit well with

immediately follows

:

‘he began to say to his disciples’) from Mt.

considers that when he wrote these passages Lk. had reached, in

taking what he has taken from Mt., exactly the neighbourhood

of the two Mt. passages just cited (1246 13

This, however,

cannot he made evident.

(6)

On

general grounds,

on

the other hand, the

dependence of Lk. on Mt. (and, equally

so,

the con-

verse) is very improbable.

I n each of the two evan-

gelists much material is absent which the other has,

while yet no possible reason can be assigned for the

omission.

Nay, more, the representations given in the

two are often in violent contradiction.

Even agree-

ments in the order, in

so

far as not coming from

almost always can be accounted for as derived from

a

second source-the logia. Simons has, therefore, in

agreement with Holtzmann, put forward his hypothesis

only in the form that Lk. regarded Mt.

as a

subsidiary

source merely, perhaps, in fact, only knew it by frequent

hearing, without giving to it any commanding import-

This is in very deed quite conceivable, if only he

knew the logia, and was in a position to observe how

freely Mt. had dealt with that material.

(c)

Soltau sought to improve the hypothesis of

dependence

on

Mt. by the assumption that it was with

the penultimate form of Mt. that Lk. was acquainted.

That Mt.

was still absent from Mt. when Lk. used

it is an old conjecture. The pieces from the middle cf

the gospel which Soltau reserves for the canonical Mt.

are

of

very opposite character (to it he reckons

the

highly legalistic saying in

and the strongly

Judaistic one in

and are attributed by him

lo

very various motives.

This indicates a great

in his hypothesis. Nevertheless the suggestion is always

worth considering that

O T

citations of the latest hand

which are adduced to prove the Messiahship of Jesus

and perhaps some other portions besides, did

not yet lie before Lk.

That there is

reason to shrink

from a hypothesis of this kind, see

Let

us

now proceed to consider whether the possible

origin from still earlier written sources of those con-

secutive books which were the last to

precede our present gospels can

raised above the level of mere con-

jecture.

This of course can be done, if at all, only at

a

few points.

T o show that it has not

been affirmed, even though no very thoroughgoing con-

sequences were drawn from the affirmation, we shall

begin by giving three examples well known in the litera-

ture of the subject.

(a)

Johannes Weiss (on Lk. 5

17,

in Meyer’s

says

that the exemplar of Mk. used by Lk. underwent, after it had been

so

made use of, another revision, which we have in our Mk. and

that

had been previously made use of by Mt. before

into the hands of Lk. H e r e and in the following paragraphs

let A,

B,

and

C he necessarily different hands, and Aa,

Ac,

on the other hand, be such portions as may perhaps

he due to one and the same hand but perhaps also

from different hands ; similarly also with

Ba,

Bc,

etc. tben

view of Weiss can be stated a s follows. A is a written

source on the healing of the paralytic without mention of the

circumstance that h e was let down through the roof. This

source was drawn upon, on the one hand by Mt., on the other

by B who introduced the new circumstance just mentioned.

was drawn upon on the one hand by Lk on the other by Mk.

It is in this way

at

the same

Weiss explains

also

how Mt. and Lk. coincide in many details as against

Mk. B thus takes the position which original Mk. has in the

usual nomenclature not however-and this is the important

point-being the oldbst writing, but being itself in turn dependent

on a source.

For our own part we cannot regard this view

as

being sufficiently firmly

since it has been shown in

that

is Mt. who has greatly curtailed the narrative of

death of Herod ; it is therefore conceivable also that

in

the

passage before

he should have left out the detail about the

roof also his interest being merely

miracle itself as prov-

ing the Messiahship of Jesus, not in any special detail of it

such

as

this

Hawkins

and also Wernle,

for

similar passages).

(6)

86-88,

assumes for the narrative of the Mission of

the disciples two sources -one (which we shall call A) relating

to that of the twelve the bther

(B)

to

that of the

Mk.

67-11

and

only from A.

A and B were both

drawn upon by a third document (C) which was used in Lk.

10

as

the sole source, hut in Mt. 10 1-16 along with A. I t

will create no difficulties if we recognise in A an original Mk.

(according to Woods

‘

the

tradition

’),

in

B

logia.

Whilst.

critics as

Bernard Weiss and Holtzmann

10

were drawn direct from the logia

(as

Lk. 9 was from Mk., or original Mk.), Woods has found it

necessary to interpolate an intermediate stage

( C )

in which both

these

were already fused. One might even feel inclined

to

go a step further. Lk. in 107

would certainly not have

given the injunction to ‘eat such things a s are set before you,’

first in speaking of a house, and then in speaking of a city, un-

less the one form had come from one source, the other from

another. I t happens, however, that neither of the

t w o

found either in Mk. or in Lk. 9. Lk.

therefore apart from

the Mk. source

(A),

which

is made use df, for

in 10

I

‘two and two’), would seem to have had two other

sources.

In any case Woods’ observation in correct that

Mt.

has fused together all the sources that can be

in

Mk. or in Lk. Whilst passing over the rest of Lk.

introduces the ‘city‘ into 10

11

at

the place where Mk. 6

The main point

is

not affected if it

be

assumed that

B

also

dealt

the mission of the twelve, and that the seventy were

first introduced by Lk.

a).

1862

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

a n d Lk. 9 4 speak of the ‘house’ ; the ‘house’ he introduces

into 10

in the parallel

to

Lk. 10 5 which is absent from Mk. and

Lk.

9.

In 10 Mt. has ‘silver

with Lk. 3

and also

’

as

(with Mk.

G

8).

Similarly,

with Mk. and Lk. he has ‘twelve’ in 10

I

,

though he had not

hitherto given the number of the twelve and has to enumerate

them for the first time in

The injunction laid on the

missionaries in 10 9 to ‘acquire’

no money is to he

explained from 108 as meaning that they are forbidden

to

take

a n y reward for their

or healing on their journey

(‘freely ye have received, freely give ’), whereas

10

(‘no

the way,’

we are to interpret it as a

on against taking anything with them when they set

(c)

Loman ( Th.

’69,

traces back to one original

parable those of the Tares in the Wheat

Mt.

and of

the Seed growing secretly in Mk.

However different

they may he apparently, he urges, and however possible it

might he to show that even such

in which they agree a s

‘man ‘spring

‘fruit

corn,’

belon ed to two quite

distinct parables, a common original form is

by the

word sleep

Mk. would never have introduced

any touch so self-evident a s that of the man sleeping and rising

night and day had there not lain before him something in which

the sleep was spoken of. By the addition that the man awoke

again daily the original meaning of the sleep is obscured.

If the two parables cannot he supposed to be of independent

origin, it is a t the same time only with great violence that we

could derive

from Mt. or

from Mk.

lacks

the quality of a trne original in

so

far a s it is not a n incident of

ordinary life that any one should

sow tares in another’s

a n d the other parables of Jesus are conspicuously taken from

affairs of every day.

lacks the character of a n original in

so far as its fundamental idea-that the kingdom of God comes

to its realization without the intervention of God or of the

Messiah (in other words, the precept of

quite a modern one, directly inconsistent with the

conceptions of Jesus a s disclosed elsewhere in the gospels.

Loman therefore supposes that

Mt.

13 24 26

alone stood in

a

source A

:

after the seed had been sown, the tares grew up with

i t

and the servants asked their master whence these came. T h e

he takes from Mk. 4

hut in the form : ‘the earth

brings forth the tares of itself,’ With this the parable ended.

That such a saying would be eminently

in the

mouth of Jesus he proves very aptly by Mt.

15

19 (out of the

heart proceed evil thoughts).

An anti-Pauline form of the

parable, however B a took Paul a s the sower of the false

doctrine which

to he denoted by the tares. I t

therefore introduced Mt. 13 25 saying that the enemy (on this

designation for Paul see

had

the tares,

it also, for the conclusion of the parable in A, substituted

Mt. 13

master’s answer that the tares were sown

by the enemy.

then added Mt. 13

that

nevertheless no attempt should be

to

the false

doctrine of

that it should be left to the Final Judg-

ment. The polemic against

here is thus milder than that

of

Paul against his Judaistic adversaries in

Cor. 11 13’15 ;

1

5

Canonical Mk., further, was acquainted

with A and Ba. I n order to avoid the anti-Pauline meaning

of

he left out the whole

of the enemy

and

consequently also the tares. H e had therefore to take the

answer of the master from

A,

not however of course in the form

that the tares sprang up of themselves, hut in the form that i t

was the good seed that did

so.

This last very modern idea

accordingly did not find expression here out of the inde-

pendent conviction of a n ancient author hut arose from the

difficulty in which

Mk.

found himself. The sleep of the master

lost its original

when the daily waking was added.

From 42 it

is

clear that Mk. had also B6 hefore him, for he

speaks

the harvest.

Canonical Mt. expressly says

the

interpretation of the parable attributed to Jesus (13 39) that the

enemy is the devil. Either, therefore, h e no longer perceives

the anti-Pauline tendency of

or like

Mk.

he deliberately

seeks to avoid it, though he takes a

different way to do so.

There remains a possibility that he may have understood the

Pauline doctrine to he meant by the false teaching introduced

by the devil ; but it

is

equally possible that he was thinking of

form of heresy.

This hypothesis of Loman combines with a literary criticism

which has far its object the elucidation of the mutual relations

of the various texts, also a tendency-criticism which postulates

a n

anti-Pauline tendency in B a . Even should one he unable to

adopt the latter criticism, it

is

not necessary on that account to

reject the former

;

it is open to any one to suppose that the

‘enemy’

may have been a t the outset some

form (as already indicated) of heresy.

To

the three examples given above we purpose

to add

a

few others which,

so

far as we are aware, have

not been previously employed in this connection.

In

Lk.

the Unjust Steward is commended.

H e accordingly must be

in the commendatory

clause

(v.

which follows-‘ H e that is faithful

in

a

very little is faithful also in much’- not in the

words of censure

106)

’ h e that is unrighteous in

a

very little

is

unrighteous also in much.’ And yet in

1 6 8 he

is

called ‘ t h e unrighteous steward.’

In

16

we read further If ye

have not been

faithful in the unrighteous mammon and

so

forth. By

the very little’

which one is to show fidelity we

must accordingly understand Mammon. Where then

are we to look for the steward’s fidelity as regards

Mammon? According to the parable, in this-that he

gave it away.

Unfaithfulness accordingly would

manifest itself if one were to keep Mammon to oneself.

T h e steward, however, did not keep Mammon to himself

and yet was called ‘unrighteous’ (which of course

is

not to be distinguished from ‘unfaithful‘).

W e see

accordingly that the terminology in 16

is in direct

opposition to that of the parable itself. Further, the

contrast in the parable

is

not in the least between

fidelity and its opposite.

What

the steward is com-

mended for

is

his cleverness the opposite to this would

be want of cleverness.

Thus

are an appendix

to the parable by another hand. Taken by

their meaning would be simply an exhortation to fidelity

in money matters.

Here, however, they are brought

into connection with the parable of the steward, whose

relation to Mammon

is

represented

as

one of fidelity.

Their fundamental idea accordingly is just as exactly

Ebionitic

as

that of the parable itself.

Thus two

Ebionitic hands can be distinguished, and distinct from

both

is

that of

Lk.

himself who has added yet another

transformation of the

where he

declares the parable to have been directed against the

Pharisees and their covetousness.

( e ) According to

we may t a l e it that the

final redaction of Mt.

was

made in a sense that was

friendly to the Gentiles

thus attached no value to

compliance with the precepts of the Mosaic law.

Unless then Mt.

5

be a marginal gloss (see

it must have been introduced

not

b y the last, but by

the pennltimate hand, and its context comes from

a

source of a n antepenultimate hand.

5

18

itself rests upon, Mt.

or the source in which this

originally stood.

‘till all things he accom-

plished does not amalgamate

with the beginning of the

verse

heaven

earth pass away [one jot or one tittle shall

in

pass away].

Moreover,

is difficult to see why the

law should cease to have validity the moment it is fulfilled

its

entirety. But the closing sentence in 2434 is perfectly intelli-

gible

:

shall not pass away till all these things

he accomplished.’ All these things’means here the premonitory

signs of the

24

35 proceeds

:

‘Heaven

earth shall pass

away; hut my words shall not pass away.

Marcion has the

same thought in his redaction of Lk. 16 17

:

‘ I t is easier that

heaven and earth

pass away than that one tittle should

fall from my words.

For this, canonical Lk. has ‘than for one

tittle

of

the law to fall.’ But this can hardly have been what

Lk. intended to say, for this verse stands between two verses

which accentuate

the greatest possible emphasis the

abolition of the law.

T h e conjecture of

therefore is

very attractive-that Lk. wrote ‘than for one tittle of my law to

fall’

Here on account

of his antipathy to the idea of law, Marcion subdtituted (hut

without altering the sense) ‘words‘ for ‘law’

But a very old transcriber of

Lk.

took

the word ‘my’

for a wrong repetition of the second syllable

of

he therefore omitted it and thereby changed

the meaning of the sentence to its opposite. This

mean-

ing

is

reproduced in Mt. 5

One

sees

how

many the intermediate steps must have

been before these two verses

have received their

present form. Still, as already said,

5

may possibly

be

a

marginal gloss.

In Mk.

and parallels

18

1-6

very diverse things are brought into combination. First,

the account of the disciples disputing with

one

another

to precedence

then the story of Jesus

little child

in

their midst with the exhortation to receive

in his

next, the exhortation

not to forbid other miracle-workers ; further, the promise

that even

a

cup of water given to

a

follower

of

Christ shall by

no

means

lose its

reward; and lastly

the threatening against those who cause any

of

the little

ones

that believe in Christ to stumble.

The close of 5

18

GOSPELS

GOSPELS

The dispute ahout precedence is answered according to Mk.

(v.

35)

by the saying of Jesus

‘

If

man would be first, he

shall be last of all and

all.

This is not found in Lk.

except in the

(22

26)

where it occurs as a parallel to Mk.

in thesameparallel

Mt. has it again, only in a quite different place (23

and yet neither

nor Lk. would have omitted it

the parallel

to

our present passage Mk. 9

35,

had they found it there. For

indeed it is very

to

the matter, whilst the mention

of the child

no means serves to settle the dispute, for the

child is not brought forward a s an example of humility hut as a

person to he ‘received,’ and not for the sake of his

a s

a child but for the sake of the ‘Name of Christ.’ Mt. felt this

want of connection and in order to represent the child a s a n

example he says

v.

that the disciples did not discuss the

question among themselves hut referred it to Jesus who

by

the little child in their midst. Between this act and

the exhortation based upon it he inserts further his third verse,

Except ye be converted and become

little children ye shall

in

no wise enter the kingdom of heaven.

This he borrows from

Mk.

10 15, as is made unmistakably clear by the fact that in the

parallel to this passage, viz., in Mt.

19 13-15,

he omits it, so as

to avoid a

183

is

also in substance a very fitting

settlement of the dispute between the disciples, and would not

have

passed over by Lk. had it lain before him. The ex-

hortation to receive such a child

is

in Mt.

185

in the same

degree inappropriate to the context.

Mt.

therefore interpolates

between the two distinct thoughts his fourth verse

:

‘Whoso-

ever shall humble himself like this

child, the same shall he

greatest in the kingdom of heaven.

But even this insertion

does not fill the hiatus between

and

5.

The exhortation in Mt. 185 to receive the little child is

immediately followed

(v.

6)

the

But whoso shall

cause one of these little ones to stumble.

This fits well enough

on the assumption that children are intended by the ‘little

I n

Mk. and Lk., however, the

two

thoughts are separated very

unnaturally by the account of the miracle-worker who followeth

not with us,’ and in Mk., too

by the promise of a reward

for the cup of cold water-a promise which

Mt.

(1042)

gives

in a quite different connection, and there, moreover, using

the expression these little ones,’

whom, however, he

stands (differently from

grown-up persons of low estate.

T o this promise there is appended in Mk.

942

the threatening

against him who shall cause one of these little ones to stumble,

quite fittihgly-only, however,

the assumption that

‘these

little ones’ we are to understand grown-up people of low estate,

children, a s in

Let

us now

endeavour to trace, genetically, the origin

and growth of this remarkably complicated passage.

In

a

source

A

were combined only those two parts which

are common to all three gospels-to wit, the statement

of the dispute among the disciples and of the placing of

a

child in the midst with the exhortation to receive him.

But no connection between them had been

as

yet

established.

This (primitive) form

is

found with least

alteration in Lk.

in Mk. it is represented

Mt. by

added to it the

promise

of

reward for the cup of water to

a

disciple

(Mk.

Bb further added the threatening against

him who shall cause

a

little one to stumble

( M k .

C

interpolated the story of the miracle-worker who

followed not with the disciples.

Its distinctive character

forbids the obvious course of assigning it to Bc.

Now,

in Mk.,

only

938 39n

40

answers to the form of the story

in

T h e form of the whole pericope which

arose through addition of this piece (without Mk.

thus takes the place which in the usual nomenclature is

given to original Mk.

Bot

on

this occasion ‘original

Mk.’ has had not one literary predecessor merely, but

two, or, should

be separated

Bb, three; and

these write not, it is to be noted, independently of each

other the one was continually making use of the other.

Canonical Mt. rests upon

A +

B

(or at least

but

Since Mt.

18

offers parallels only to what we have

to

one might be inclined rather to attribute to

the

addition

Mk.

and to

that of Mk.

If this were

done it would have

to

be presupposed (what was left open, above,

under

a)

that

Ba

and B6 mean two different authors.

We

should then have the advantage of being able to suppose that

was

acquainted with Ba,

hut not with

A t the same

time, however, we should have to attribute Mk.

in that case

rather to

C,

for on the previously mentioned presupposition it

must remain equally possible that

and

B6

together mean

only one author. T h e hypothesis would, therefore, only become

more complicated.

Further, it is not probable that Mk. 9

42

should have been introduced earlier than

I t is simpler,

therefore, to suppose that

knew

other words

Mk.

a s well a s Mk.

but that he dropped

he had himself already reproduced the same thought in 10

42

(cp

1865

surely

also

:

see last footnote). Mt. then, as

above, changed the introduction in

v.

I

,

and added his

own

3

,

so

as to bring into mutual connection the

dispute about precedence and the precept about receiving

the child.

6,

through its direct contiguity with

v.

(instead of with 1042 which here ought to have been

repeated as parallel to

Mk.

underwent a change of

meaning, to the effect that children, not grown-up

persons, were meant.

L k .

rests on

A +

C. H e added

he that is least among you all, the same

is

great.‘

This does not, indeed, come in appropriately after the

precept about receiving

a

child it would have found a

with greater fitness before this precept and after

the statement of the disciples’ dispute, in other words

between

and

v.

a t the very point where

Mk.

v.

35

introduces the same thought.

Mk.

rests

upon

H e adds

on

the one hand his

which Lk. would certainly not have passed over

had he known it, and

on

the other hand his

35,

containing

so

excellent

a

settlement of the

dispute.

Neither Mt. nor Lk. was acquainted with the

verse or

(as

already said) they would not have omitted

it or introduced something like it at

a

later place,

as

in Lk.

I t is certainly worthy of notice that

M k . ,

by the in-

sertion of

35,

has produced the only doublet which he

has

121

a ,

n.

I

).

The circumstance that Jesus calls the

disciples to him in

35

whilst in

he has already

been questioning them, points also to the conclusion that

the passage is composed from various pieces.

The successive contents of

Mk.

4

1-34

and parallels

(Mt.

Lk.

84-18)

cannot possibly have been set

down in any one gospel in their present order a t one

writing.

Let us examine them.

After the parable of

the Sower, Jesus

is

alone with his disciples

( M k .

Mt.

89)

so

also when he explains the par-

able

13

Lk.

8

11-15).

Nor is any

hint given of his again addressing himself to the

people yet we read in

that he spoke openly

to the people

parables

(so

also Mt.

.and

that he gave his explanations to the disciples in private.

There is ground, therefore, for supposing that in one

source,

A,

there stood an uninterrupted series of parables,

all those which have parallels in Mt. (Mk.

26-29 30-32-in

an

older form

as

regards 26-29 see

above,

also the conclusion

33$

Bn, on the

strength of the concluding statement that when they

were alone Jesus expounded all things to his dis-

ciples, introduced Mk.

4

14-20

Bb the

21-25

to the effect that one ought not to keep hack know-

ledge once gained of the meaning of

a

parable, but

ought to spread it freely. C introduced

These

verses to the effect that the parables were interded

to conceal the meaning they contained from the people

are in contradiction

alike

to

v.

and to

21-25,

and are, moreover, impossible in the mouth of Jesus.

What pleasure could he have had in his teaching if

he had to believe

his

God-given task to be that of

hiding from the people the truths of salvation?

It

is,

therefore, utterly futile to make out forced con-

nection between

M k .

and

M k .

4

$ ,

by inter-

preting to the effect that Jesus, when asked

as

to the

meaning of the parables, in the first place, said, b y

way of introduction to his answer, that to the disciples it

was given to apprehend the meaning, and then went

on

to tell them what it was.

Moreover, Mk. 413 does not

fit in with this connection.

T h e verse is clearly

a

question in which Jesus expresses his astonishment a t

the small understanding of the disciples : How?

you

I n

4

IO

the disciples ask concerning ‘the parables.’ T h e

plural carries us back to what is said in Mk. 42 that Jesus spoke

several. The

therefore, can very well he that which Lk.

9)

expresses more clearly though with reference to one parable

only: they asked about the

of these parables. Were

it the intention of Mk. to say like

Mt.

(13

that they asked

about the

of the parables then we must suppose that

only Lk.

rightly preserved

thought of the source

GOSPELS

do not understand this parable; how then shall you

know all the parables?’ This astonishment again is

out of place if Jesus in

has found nothing to be

surprised at in the circumstance that the disciples needed

t o have the meaning first of all imparted to them. T h e

question is appropriate, therefore, only

as

a direct reply

to

v.

I

O

,

and furnishes a aery good occasion for Jesus to

decide to give them the interpretation (cp, further,

129 n.). Here also, as

C takes the position

which elsewhere is appropriate to original

and here

also

there are two or three antecedent literary stages.

D

inserted the

(Mt.

Each of the three canonical gospels then rests upon

Mt., too, upon

D.

Mk. did not

change the extent of

vv.

(perhaps it was he who left

out the

from

cp

RV

with

AV),

on the other

hand he gave to

a form which suits the applica-

tion here made of the saying better than does that of Mt.

and Lk. (see

u).

Mt. and Lk., on the other hand,

in order to be able to retain from

C,

Mk.

deleted

the surprised question of Jesus in Mk.

(from

Ba),

because it was inappropriate after this insertion.

Moreover, Mt. has

also

so

altered the question of the

disciples (who in Mk.

and Lk.

ask as to the

meaning of the parable) as to make it suit the answer

which was first brought in from C : ‘ t o you it is given

t o understand the parables, but to the multitude it is not

given.’ I t now runs in Mt. (13

IO)

:

Why speakest thou

to them in parables?’ But such

a

form of the question

cannot have been the original one-for this reason, if

for no other, that according to it, Jesus would have had

no occasion to expound the parable to the disciples.

Further, Mt. has in

introduced a saying which in

at first came after the interpretation of the first par-

able. W e further see that he must have found difficulty

in the assertion that the purpose

Mk. 412) of the

parables was to conceal the meaning they contained.

H e substitutes therefore : For this cause do

I

speak to

them in parables

they see not and hear

not.’ H e thus puts in the foreground the defective

understanding of the multitude as

a

fact with which

Jesus must reckon.

By what follows, however

(v.

taken from Isaiah, he gives it clearly to be seen that he

had before him an exemplar in which their not being

understood was alleged as the

of the parables

(see the lest perchance,’

in

13

Finally

perhaps it was Mt. himself who added the interpretation

of

the parable of the Tares (not immediately after the

parable, but at the end of the whole section that

is

parallel to

cp

and also the other

parables

1336-52

;

possibly also

35.

Still it is

also permissible to suppose that only Mk. 4

stood in

A

but this makes little change in

our

construction as a

whole ; it bnly becomes necessary in that case to postulate that

Bc added Mk. 4

26-32.

On

the other hand, the mutual relation

of

sources can become

still somewhat more complicated if

hypothesis regarding

26-29

(see above

be combined with what has just been

elahorated about

4

Yet it is possible to do this without

multiplying the number of sources. We therefore refrain from

introducing the hypothesis in question,

all

more because

it

might, as being of the nature of tendency-criticism, call forth

special objections.

( h )

Finally, it has to be pointed out that even the

doublets might be used to give probability to the com-

posite character of the logia.

In

they have heen

employed to show that Mt. and Lk. alike draw from

two sources. For the most part these were, on the one

hand Mk. (or original Mk. and on the other the logia.

Only,

happens by no means infrequently that both

places

which Mt. has the same saying are generally

traced to the logia. What would seem to follow for

this would be that the writer of the logia himself made

tosupposethat

Lk.

may have

because he already had

it

38,

and that Mt. may have omitted all these verses hecause he

also had them all elsewhere in one place

or another ( 5

15

6

last, in particular,

in

the very pericope with which

we are

now

dealing (13 12).

1867

use of two sources. Now, we are not inclined to carry

back Mt.

to two sources from which the logia

drew, but prefer to regard the repetition

as

an express

and deliberate accentuation of the statement upon which

stress is here laid.

But we do in all seriousness adduce

( ‘ m o r e tolerable for

(the tree and its fruits), as well as the utterances of

John which are

also

afterwards put into the mouth of

Jesus

‘ y e offspring of vipers, how shall ye

escape’