EN-RIMMON

traces to the

(

man

of

must have been substituted for some other name.

On

the original position of Gen.

4

see C

AINITES

,

The M T reading,

is

if not certainly,

to

be

rendered ‘Then was profaned,’ the object being to avoid

contradiction of the statement

in

Ex.

4 3

(P).

Such

a

phrase,

however,

as

with

isunparalleled in the Genesis narratives.

‘began,’ occurs again in

9

10

8,

where, it is true, accord-

ing to

Simon

has the sense of profanation.

The alteration of

into

involved

a

disparagement

of

Enos

similar to that inflicted upon

I

,

end) and N

OAH

end) in certain circles. According

an Aggada, in the

time

of

this patriarch, and in that of Cain, the sea flooded

a

great tract of land

as

above). The same extra-

ordinary view of

is

implied in

Onk. and

Jon.

and is

adopted

EN-RIMMON

fountain of Rimmon

the god

[see RIMMON i.]

[BAL]), mentioned in

a list of Judahite villages ( E

Z R A

ii.

1 5

§

BA omit), but also referred t o in Josh.

32

a n d

[A]) and

I

(Ain, Rimmon,

[L]), Zech.

(‘from Geba t o

Rimmon, south of Jerusalem’).

is the

or Eremmon of Eusebius and Jerome

( O S

described by them as

a

‘very large

village

16

m.

from Eleutheropolis.

I t

is usually

identified with modern

9 m.

of Beersheba.

Zech.

14

however, suggests that it

lay farther to the

Elsewhere

it

is

suggested that Azmon,

a

place on the extreme

S.

,of

Judah

(Nu.

Josh. 154) is

a corruption of

and that this

is represented by the once highly

cultivated el-‘Aujeh in the

called by Arab

tradition

a

valley of gardens

(E. H.

Palmer).

EN-BOGEL

H

H

T

O

Y

p.

a

famous land-mark near Jerusalem.

I t was the

place of David‘s spies, Jonathan and

and lay close to the stone Z

OHELETH

where

Adonijah held

a sacrificial feast when he attempted t o

assert his claims to the throne

(

I

K.

I n later

times it was one

of the boundary marks between Judah

and Benjamin (Josh.

15

18 16).

T h e

sacred

character of the spring (cp also G

IHON

[

I

],

I

K.

1 3 8 )

snggests that it is the

as the Dragon Well of

(cp

but see

There can be little doubt of its antiquity, and

it

well have been

a sacred place in pre-Israelite times.

The meaning

of

the name and its identification are

uncertain.

Fuller’s Well does not bear the mark

of antiquity, and

is

rightly omitted

‘fuller,’

is

nowhere else found in biblical Hebrew (see F

U

LLER

,

I t is probable that, like

the original

name had some sacred or mythic significance.

,

Two identifications

of

the place have met with considerable

favour :

(I)

the Virgin’s

now

Umm ed-Deraj,

only real spring close to Jerusalem,

exactly opposite

to

which lies

perhaps Zoheleth

PEFQ

p.

253)

otherwise known as the Well of Nehemiah,

at

the

of

the W.

and Kedron (Robinson

Against

(which has found recent support in

P.

Smith,

and

Benz

it is urged that

is

a

well, not a spring

that

far from

that it is in full view

the city, and does not snit the context

of

17 r7,

and that

its antiquity is uncertain. The chief points in favour of

(

I

)

(which

identifies with

are :

its

antiquity (cp

C

ONDUITS

,

4)

and the evidence of

(Ani.

14

who

places the well in the royal

Other arguments based

upon the fact that in later times the well was used

fullers

are necessarilv precarious.

A .

T. K. C.

The interpretation

H. P.

Smith however observes

that

water flows into the

well,

the top,

so

that it might readily

be called

a

spring

(Sam. 354).

The

identification

of

En-rogel with

10 4

see Grove,

seems difficult

reading is

the

same in

all

MSS

(see

and appears to be

based upon

which follows.

ENSIGNS AND STANDARDS

ENROLMENT

Lk.

22

Acts

537,

AV

‘taxing’)

to be enrolled

Lk.

2 1 3 5 ,

AV ‘taxed’

Heb.

AV ‘written

3

Macc.

RV has ‘enrolled’ also in Tim.

59

AV ‘taken

into the number’) and

in

(‘enrolled him

as a

soldier,’ AV chosen

to be

a

soldier

’).

EN-SHEMESH

‘fountain

of the

on the

of Benjamin, between

ROGEL

and A

DUMMIM

.

The favourite identification

with the modern

or Apostles’ shrine’ near

Bethany is questioned by

who seems to

prefer the tradition which identifies the Well of the Sun

and the Dragon’s Well with

‘Ain

(see

ROGEL

).

Van Kasteren, however

; see

also Buhl,

Pal.

would find En-shemesh in

in an offshoot of the

of

the same name,

situated

on the ancient road to Jericho.

ENSIGNS AND STANDARDS.

Two

questions

have to be considered here:

(

I

)

how are the Hebrew

terms t o be rendered, and

what inferences are to be

drawn from the historical passages containing these

terms ?

(a)

also

a n d

[BMAL etc.]).

I n Is.

11

30

31

(text corrupt see

is rendered

‘ensign.’ but

46

See

T

AXATION

.

..

50

51

27

‘stand-

1.

Renderings.

ard’;

AV also

gives

the

latter in

Is.

and RV

in

Nu.

‘Banner’ is

adopted by AV in

Is.

(KV ‘ensign’) and

by

E V

G O 4

(see below),

also

by

in Ex.

In

Nu.

21

8

AV

RV standard.

‘

Banner,’ being still in common

use,

seems the best

rendering for

except in

Nu.

is

more natural.

Banner is required

also in Ex.

17

where Moses

is

said to have named an altar

is

my banner’ (see J

EHOVAH

-

NISSI

), and

t o have broken into this piece of song

:-

Yea (lifting up) the hand towards

banner

(I

that)

will give battle to

Here,

we must not pass over four disputed passages

in which AV (and

in some cases RV) assumes the

existence

of a

denom. verb from

Ps.

6 0 4

a banner

. . .

that it may be displayed

’);

Is.

1 0

E V standard-bearer,’

sick man

Is.

59

lift

up

a standard,’

so

but RV [which]

. . .

driveth,’

‘ p u t

to flight’) ;

Zech.

(‘lifted

up

a s an ensign,’ but RV ‘lifted

on high,’

glittering

’).

All

these four passages must be

regarded as corrupt.

( u )

Ps.

should probably

be read thus, Thou

given

a

cup

[of judgment] t o

thy worshippers that they may be frenzied because of

the bow’

cp Jer.

I n compensation

Ps.

becomes,

I

will raise the banner

for

of

victory.’

Is.

apparently

b e

a

thorn-bush.

( y ) Is.

59

should

probably be

Che.), when

breath

it.’

The text of Zech.

needs some

rearrangement (see Che.

10582).

‘Stones

of a

diadem lifting themselves up over his land’

is nonsense.

I n

probably

should be

Glittering

stones,

used as amnlets (see P

RECIOUS

S

TONES

), are meant.

(6)

is rendered by E V ‘banner

’

in Cant.

by ‘standard’ in Nu.

22,

etc.

E V also finds

a denom. verb from

in Ps. 20

Cant.

5

IO

6 4

IO

.

Gray thinks

Schick

observes that the name

‘eye of the sun,’ is popularly

to holes in prominent

rocks.

The name dates from the fifteenth century. I t is the last well

on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho before the dry desert

is

reached, and

it

is therefore assumed that the apostles must have

drunk from it on their journey.

1298

ENSIGNS AND STANDARDS

that the context of

the passages in Nu. is fully

satisfied by the meaning company,’ whilst in some of

them the sense standard is plainly unsuitable.

T h e

sense of company,’ however, is even more difficult to

justify than that of ‘banner.’

in

Nu.

1 2 1 0

is

probably a corruption of

‘

troop

or

band

’

the

sense of the word in

I

Ch.

is strikingly

parallel.

No

other course is open, for

all the other

passages adduced for the sense of

banner are, with

the possible exception of those in Numbers, corrupt.

This applies not only to Cant.

but also to the

passages in which

a denom. verb is assumed

Cant.

For

an

examination of these

passages see Che.

11

232-236.

In Cant.

read, ‘Bring me

(so

into the garden-house

I

am sick from love. Stay me, etc.’

As

t o

Ps.

205

it is safe to say that ‘to set

banners

in

name

of Yahwb’ is an unnatural phrase (read

‘we exult’). The

bridegroom in Canticles

etc.)

is

not ‘marked

out

by a

banner above ten thousand’

he may perhaps be

‘one looked up

to,

admired

but more probably he

was

,described in the original text as

‘perfect (in beauty).’

The bride on her side

is

not called ‘terrible as bannered [hosts]

but ‘awe-inspiring as towers’;

so

at least a scribe, but not thk

poet himself, wrote. The corruption was

a

very early one.

The scribe, seeking

to

make sense of half-effaced letters which

he misread

him

of

the figure in

and inserted

‘as towers.’

(c)

is

rendered ‘ensign’ by E V

in

Nu.

22

or

[BAF],

[L]), Ps.

744

I n the latter passage the ensigns

have been supposed to be military standards with

heathen emblems upon

which reminds

us of a

similar theory respecting the abomination of desola-

t i o n ’ in Mt. 2415.

T h e context of the passage in

Ps.,

however,

is

very

Of

all the above passages there are only two which

a r e a t once old and free from

Ex.

E P H A H

and two other devices apparently representing flies.

T h e standard of the Heta-fortress of

Dapuru

which

in

a

representation of

a

siege consists of

a

shield

upon

a pole pierced with arrows (see E

GYPT

, fig.

4,

col.

1223).

Reference is made elsewhere (I

SRAEL

, 90)

to the courtesy with which the Roman procurators,

in deference to Jewish prejudice, removed from the

ensigns

the

of the

emperor.

It was not the ensigns themselves but the

presence of the additional

that was the cause

of the Jewish sedition against

(cp

Ant.

See further,

‘Signa Militaria’

in S m i t h s

and art. Flag in

T.

C.-S.

A.

C.

EN-TAPPUAH

etc.), Josh.

[Ti. WH]), my beloved,

the first-fruits of Asia unto Christ,’ as he is described

the salutation sent to him in Rom.

appears to

have been Paul’s first convert in Ephesus,

as Stephanas

a n d his household were in Corinth

( I

Cor.

16

From

his not being designated kinsman it has been inferred

that he was

a Gentile.

T h e name

is of not uncommon

occurrence

the East

(Ephesus),

(Phrygia). For the bearing which this name has upon

the criticism of the epistle, see R

OMANS

,

4,

I O.

C p

C

OLOSSIANS

,

4.

In the lists of

seventydisciples’by the Pseudo-Dorotheus

and Pseudo-Hippolytus (see D

I

SC

IPL

E

,

figures

as Bishop

of

Carthage or Carthagena

In the Greek Church he is commemorated with Crescens,

and Andronicus on 30th July.

EPAPHRAS

[Ti. W H ] , an abbreviate!

form

of

a faithful ‘minister

and

‘

bond-servant

of Christ (Col.

founder of the church a t

and teacher in the

towns of Laodicea

and Hierapolis (see

Epaphras visited Paul in his

captivity, and it is probable that the outbreak of false

teaching in the Colossian church may have led him t o

seek

Paul’s

aid with the result that the epistle to the

C

OLOSSIANS

(see

was written.

Did Epaphras

share

Paul’s

imprisonment during the writing of the

epistle,

or does

fellow-prisoner

( 6

Philem. 23) refer to merely

a

spiritual captivity?

Cp

the term fellow-soldier (art. E

PAPHRODXTUS

) below,

and see

in Hastings‘

‘charming’), the delegate

see A

POSTLE

,

I

n.,

3)

of the Philippians, visited

Paul during his

imprisonment a t Rome and remained with him-

to

the detriment of his health (Phil.

Paul’s

estimate of him is summed up in the eulogy ‘my brother

a n d fellow

-

worker and fellow soldier

On

his return

Epaphroditus

no doubt took with him the epistle to

the P

HILIPPIANS

, the grave warnings of which

have been due to the report he had brought

E

PAPHRAS

).

It is by no means necessary to identify

Epaphras and Epaphroditus : indeed, though they have

several features in common (note,

‘

a n d

fellow-prisoner

these are far outweighed by

the points of difference.

Epaphroditus

is a common

name in the Roman

I

.

Perhaps rather

or

a Midianite clan

Gen.

[A],

I

Ch.

[B],

[A]).

With Midian it is mentioned in

Is.

Can one compare the mysterious ‘hornet‘ which paved the

way for the entrance of the tribes

into

Canaan (see H

ORNET

)?

TR

(cp

AV)

is certainly wrong see A

CHAIA

(end).

Notably the one

to

whom

Josephus dedicated his ‘Antiqui-

ties

(Vita,

76 ;

Ant.

Pref.,

c.

i.

I

).

According to

As.

7th ser.

10

occurs as a personal name in the

inscriptions.

See

T

APPUAH

,

EPAPHRODITUS

[Ti.

Nu.

pole in the

latter passage was probably such

as

was commonly used for signals

to

collect the Israelites when scattered

the

in the

former was

a pole with some kind of (coloured

cloth

4

upon it to attract attention.

Other terms which might be used for ‘banner were

(Is.

and

(Jer.

R V

‘signal’).

T h a t

also

was

so

used in early times is

more than can be stated safely, nor can we tell what

distinction there

have been between

and

Tg. Jerus. (pseudo-Jon.) tells

us

that the standards were

of

silk of three colours, and had pictured upon them

a

lion,

a stag,

a

young man,

or

a

cerastes respectively.

History to the writer of this

was not essentially

Banners are frequently found

on

the Egyptian and

Apart from the royal banner,

each battalion or even each company in

Egypt had its own particular emblem,

which took the form of

a

monarch’s name,

a

sacred

boat,

an

animal, or some symbol the meaning of which

is

less

T h e standard was borne aloft

npon

a

spear

or staff, and carried by an officer who

wore

a n emblem two lions (to symbolise courage)

different from poetry.

T.

K. C.

the Assyrian monuments.

I t maybe mentioned that Friedr. Del.

40

went

too

far in rendering Assyr.

‘banner

it

simply means as

own

states the’object of gaze,

or of

(on the Arabic and Syriac

cp Gray

The Jews certainly regarded the

on

the Roman

standards

as

idols see below.

3.

3

For an attempted restoration, see Che.

In Is. 3323 EV rightly renders

‘sail‘; a coloured,

is meant (Ezek.

Mr.

A. Cook suggests that the

in

Nu. 22 may

refer

to

clan-marks (cp C

UTTINGS

,

6).

See Goblet

Migration of

In

some cases the symbols may have been mere

for

analogies cp Frazer,

30.

EPHAH

606

as being rich in camels, and a s bringing gold and

incense from Sheba.

See

and

3.

names

I

Ch.

2 46

47.

EPHAH

[Lev.

620

Nu.

Judg.

Ruth

I

S.

Ezek.

Pr.

Am., Zech., Ezek.,

See

W

EIGHTS

AND

M

EASURES

.

[B],

Syr.

according to M T ,

a

man

of

Netophah, whose

sons

were among the adherents of Gedaliah

I n

the parallel text,

K.

is not

found.

Apparently sons of

. . .

is

a

corruption

of

a

duplication

of the following word

Netophathite,'

( C h e . ) ; note the warning

which pre-

cedes.

T h e Netophathite meant is

S

EXAIAH

,

3 ) .

EPHER

'gazelle,'

68,

cp E

P H R O N

;

EPKAI

;

[A],

EPHESUS

not improbably be inserted by the redactor from

which

verse seems

to

have

from

another version

of

t h e

tradition

(see

Klo.).

T h e present writer, who prefers the former of the

alternatives suggested above, supposes

(

I

)

that

in the

valley of Rephaim (or Ephraim)

is a discrepant state-

ment of the scene of the fight with Goliath, and

that it is the

correct statement.

may have an

insuperable objection to this, and for their benefit

another suggestion is

It is not inconceivable

that Valley of the Terebinth

was the name of

that part of the valley in which David won his victory,

whilst

a larger section of the valley was called Valley

of the red-brown [lands]'

cp the ascent of

brown [hills],' Josh.

7

;

red-brown in each case

is

Large patches of it (the ploughed land in the

valley of Elah) were of

deep red colour, exceptional,

and therefore remarkable' (Miller,

The

Least

Lands,

From

to

is an easy step.

H. P.

Smith is hardly decisive enough in his rejection

of Lagarde's

T h e torrent was

dried

and no longer

a landmark.

See

EPHESIANS.

See

COLOSSIANS

AN

D

E

PHESIANS

.

EPHESUS

[Ti.

WH]

gent.

lay

on the left bank of the Cayster (mod.

Little Meander), about 6

m. from the sea, nearly opposite the island

of Samos.

Long before the Ionian im-

migration the port a t the month of the river had

attracted settlers, who are called

(Paus. vii.

2

6 ) ,

but were probably the Hittites whose centre

of

power

lay a t Pteria in Cappadocia see H

ITTITES

,

11

To

the

E.

of Mt. Koressos, in the plain between the

isolated height of

(or Pion) and the eminence

at the foot of which the modern village stands, there

a

shrine of the many-breasted Nature-goddess

identified by the Greeks with their own Artemis (see

D

IANA

).

T h e population lived, in the primitive

Anatolian fashion, in village groups

round the

shrine, on land belonging to it wholly or in part, com-

pletely dominated by the priests.

With the coming

of

the

who, after long conflict, established them-

selves on the spur

of

Mt. Koressos now shown as the

place

of

Paul's prison (ancient

began

an

obstinate struggle between the Oriental hierarchy and

Hellenic political ideas, which were based upon the

conception of the city

The early struggles of

the immigrants with the armed priestesses perhaps gave

rise to the Greek Amazon-legends.

Even after actual

hostilities had ceased, and the two

had

agreed to live side by side, this dualism continued to be

t o Ephesian history.

T h e power

of the priestly

community remained co-ordinate with, or only partially

subordinate to, that

of the civic authorities

the city and the temple continued to bc

formally distinct centres of life and govern-

ment (cp Curtius,

s.

Gesch.

Top.

T h e situation of the shrine, near one of the oldest ports

of Asia Minor, at the very gateway of the East (Strabo,

663) brought the worship into contact with allied Semitic

cults.

These and similar influences gave the Ephesian

worship that

character which was its greatest

boast (Acts

1 9 2 7

Paus.

318

Hicks,

Brit.

482, see

Class.

Rev. 1893,

78

apart from the existence

of

the

the greatness

of Ephesus was assured for, admirably placed

as

were

all the Ionic cities (Herod.

none were so fortunate

as Ephesus, lying as she did midway between the Hermos

on the N . (at the mouth of which was Smyrna) and the

on the

S.

(port, Miletus).

On

the downfall

of

Smyrna, before the Lydians, about

j

and

See

and cp

76.

For

the grounds

of

this

reading see Dr.

lxxviii.,

292,

and note

criticism

on

Lag.

1302

VALLEY

OF.

T.

K .

C.

I

.

A

Midianite clan, Gen.

[L])

I

Ch.

1 3 3

[L]).

and

com-

pare the Banu

of the stem of

but if H

A N O C H

I

)

has been rightly identified,

Epher may very possibly be the modern

which

is

near

between the

mountain range

a n d

(so

see Di.). Glaser

however, prefers to connect the name with the

of the inscriptions of

2223).

From its mention

in

connection with Judah,

E.

Manasseh, and Reuben (see below), it is possible that

various layers of the tribe of Epher were incorporated

with the Israelites at

a

later time (cp

in Schenkel,

4218.

See

b.

of

I

417

I

.,

A

head of

a

subdivision

of

I

Cb. 5

24

cp

i.,

S.

A.

C.

EPHES-DAMMIM

[Pesh.]

[Aq.], in

dommim

[Vg.]

O S

35

I

T

,

9 6 2 3 ,

226

or, if

be

to mean ' e n d

Dammim

according to

M T , the name

of a

spot where the Philistines encamped,

between

I

,

and

(

I

17

I

) .

By Van

d e Velde (who is followed in Riehm's

it

is

identified with

on the N. side of the

E.

of the Roman road to

but

a

,different name

for this ruin was obtained in the

Ordnance Survey, and the name

if it occurs

a t all, seems to belong to

a

site nearer the high hills.

Conder

p.

on

the other hand, finds

a n

echo of the name in

a place of bleeding

'),

which is close t o Socoh

on the

SE.

This

will not do for the site of the encampment-for the

reason given in Che.

Aids,

85,

n. I-but Conder's

view is not that

represents the site (Buhl,

n.

but that it

is an echo of

a

name of

the great valley of Elah (see

V

ALLEY

OF

)

which

arose out of the sanguinary conflicts that frequently

occurred there.

This is too fanciful

a conjecture.

W e must, it would seem, either regard ' i n Ephes-

in

I

S.

as (on the analogy of

a

corruption

of

' i n the valley of

Rephaim' (or Ephraim; see R

EPHAIM

),

or

else take

to be

a corruption of some proper name,

being

in

this case also

a corruption of

valley.'

T h e latter view is less probable, but

impossible.

The Philistines appear

to

have encamped on the southern,

and the Israelites on the northern side

of

the valley

of

Elah (see

Che. Aids,

and, considering

how

often the same valley has

more than one

name,

we

may conjecture that the

site

of

the

Philistine encampment

was

described

as

' i n

the

valley

of

X ' =

'in

the

of

Elah'

(or

'terebinth-valley'). In

I

S.

some

point

i n the

valley

of

is mentioned

as

the

site of

the-

of

the Israelites ;

but

'

in the valley

of

Elah

'

would

1301

EPHESUS

EPHESUS

the ruin

of

and Miletus by the Persians in 494

B.

she inherited the trade of the Hermos and

valleys. T h e port had always suffered from the alluvium

of the Cayster, and its ultimate destruction from that

cause had been rendered inevitable by an unfortunate

engineering scheme of

Philadelphus, about

a

century and

a half before Strabo wrote yet in Strabo's

time a n d in that of Paul the city was the greatest em-

porium of Asia (Str.

641,

reflected in Rev.

Shortly after Paul's visit the proconsul

Barea

tried t o dredge the port

(61

A.

D

.

Ann.

Its commercial relations are illus-

trated

the fact that even the

of

Cappadocia was shipped from Ephesus, not

(Str.

and by the travels of Paul himself (Acts

18

19

I

cp

Ephesus was the centre of Roman

administration in Asia.

T h e narrative in Acts reveals

a n intimate acquaintance with the special features of its

position.

As the Province

of

Asia was senatorial (Str.

the governor is rightly called

Being

a free city, Ephesus had assemblies and magistrates,

senate

and popular assembly

of its

o w n ; but orderliness in the exercise of civic functions

was jealously demanded by the imperial system (Acts

cp

1883,

p.

506).

T h e

theatre, which

probably the usual place

of

meeting

for the

is still visible.

Owing to the decay

of popular government under the empire, the 'public

clerk

became the most import-

ant

of the three 'recorders,' and the picture

Acts

of the town-clerk's consciousness of responsibility, a n d

his influence with the mob is true to the inscriptions

2966, etc.).

From its devotion to

Artemis the city appropriated the title Neokoros' (Acts

1935 :

temple-sweeper

'),

and,

as

the

town-clerk said, its right to the title was notorious.

The word Neokoros was 'an old religious term adopted and

developed in the imperial

under theempire the title

Neokoros, or Neokoros

of

the Emperors was conferred by the

Senate's decree at Rome, and was coincident with the erection

of a temple and the establishment

of

games in honour of an

Emperor. When a second temple and periodical games were,

by leave

of

the Senate, established, in honour of

a

later Emperor

the city became

('twice Neokoros'), and

N.)

'thrice Neokoros in inscriptions and on coins.

Hence under the empire not only Ephesns hut also Laodiceia

and other Asiatic cities boasted the title. See Rams.

158

; Buchner,

de

Naturally Ephesus was the head

of a conventus,-Le.,

it was a n assize town

527,

Ephesuni vero, alterum

lumen

remotiores conveniunt

hence in Acts 19

38

' t h e courts are

open'

Jos.

Ant. xiv.

Strabo, 629). From its

position as the metropolis of Roman Asia Ephesus was

naturally

a

meeting-point of the great roads.

On the one side

a

road crossing Mt.

ran

wards to Sardis, and

so

into

(cp G

ALATIA

).

More

important was that which ran southwards into the

valley. Ephesus was, therefore, the western terminus

of

the

'

back-bone of the Roman road system '-the great trade route

to the Euphrates by way

of

Laodiceia and

(Rams.

Hist.

of

A M

the sea-end of the road along

which most of the criminals sent to Rome from the province

of

Asia would be led' (Rams.

in

R.

hence Ignatius,

writing to the church there, says, 'ye are a high road of them

that are on their way to die unto God'

cp Rev.

I t was, in part, by the route just described, that

Paul

his Third journey reached Ephesus from the

interior, avoiding, however, the towns of the Lycus

valley by taking the more northerly horse-path over the

Duz-bel pass, by way

of Seiblia (Acts

191,

Acts

19

38,

the plural is generic, although other.;

take it to

to

P.

Celer, imperial procurator, and the

man Helius, who may have remained in Asia with joint pro.

consular power after murdering the proconsul Junius

at

the instigationof Agrippina,

54

Ann. 13

I

Cp Jos.

Ant.

xix.

S

Agrippa at Cresarea

Hist.

2

so,

Antiochensium

ingressus, ubi

mos

est.

.

Jos.

3

Pro

7,

;

Philostr.

4

(p.

of

Ephesus.

See Rams.

i n

94).

True to his principle, Paul went to the centre of Roman.

life and along the great lines of communication, with-

out his personal intervcntion. his message spread east-~

wards into the Lycus valley (see C

OLOSSE

,

H

I

ERAPOLIS

,

L

AODICEA

).

All the

seven churches'

of

1-3

were probably founded at this period, for all

trade centres and in communication with Ephesus.

T h e

labours of subordinates were largely responsible for their

foundation, perhaps in all cases, though it is only in one

group that evidence

is

forthcoming

(Col.

1 7

T h e position of Ephesus as the metropolis of Asia

is.

clearly reflected

her primacy in the list (Rev.

1

21).

this way, ' a l l they which dwelt in Asia heard the

word

.

.

.

both Jews and Greeks' (Acts

Jews we should expect to find in great numbers at

Ephesus.

As early as

44

B

.

in his consul-

ship had granted them toleration for their rites a n d

Sabbath observance, and safe conduct

their pilgrimage

to Jerusalem

(Jos.

Ant.

10

they must then have

been

a rich community to have been able to buy

favours.

Their privileges were confirmed by the city

and subsequently by

(id.,

To

them, as usual (cp A

CTS

,

4), was Paul's

first message on both visits (Acts

18

198)

but the

good-will with which he had been welcomed on his

first appearance (Acts

cooled,

and he was compelled a t last to take

his teaching from the synagogue to the

philosophical 'school of one Tyrannus' (Acts 19

from the

to the tenth hour' added by

after the usual.

teaching hours cp

1887,

400

Rams.

Expos.

1893,

p.

223).

practices peculiar to the place

a twofold manner.

Paul came into collision with the beliefs and.

Ephesus was a centre of the magical arts of the East.

I t is significant that the earliest Ephesian document extant

deals with the rules of augury (6th cent.

B.C.

Brit.

678).

The so-called 'Ephesian

engraved upon thestatue

of

the

they were inscribed upon tablets of terra-cotta or other

materiai and used as amulets

When pronounced

they were regarded as powerful charms, especially

in

cases of possession

evil

spirits (cp

vii.

54:

The study

of

these symbols was an

elaborate pseudo-science.

T h e miracles ascribed to Paul were therefore

designed

to

meet

the circumstances; they were.

special' (Acts

:

expulsion

of diseases and of evil spirits by

of

kerchiefs or aprons

which-

are, possibly, to be connected with Paul's own daily

for his living

(

I

Cor.

:

I

Thess.

Especially

his.

power brought into comparison with that claimed by

the Jewish

(see E

XORCISTS

), as previously in

Paphos (Acts

although in the story of the sons

of Sceva and the burning of the treatises

magic

there are considerable difficulties-' the writer is here

rather

a picker-up of current gossip,

Herodotus,

than

a real historian (Rams.

I n the second place, the new teaching came

collision with the popular worship.

Even before

the great outbreak, fierce opposition must have

been encountered from the populace

(

I

Cor.

15

32

:

I

fought with beasts

'-a word which

contains

a mixture

of

Roman and Greek ideas

:

the

Platonic comparison of the mob to

a beast,

493,

and the death of criminals in the circus cp

I

Cor.

4 9

:

6

and

I n the conviction that

' a

great door and effectual'

opened in the province,

in spite of there being

adversaries'

(

I

Cor.

From the seven letters, chap.

w e

see how carefully

the author had studied the situation in the Christian

munities accessible

to

EPHESUS

the apostle had resolved to remain at Ephesus

until Pentecost (of

5 7

probably). The great festival

of the goddess occurred in the month Artemision

but whether it must be brought into

connection with the riot or not

is

uncertain.

T h e

opposition did not originate with the priests,

was

organised by the associated tradesmen engaged in the

manufacture of

shrines

led by Demetrius who

was one of the chief employers of labour (Acts

1 9

24

see D

IANA

,

Such trade-guilds

were common in Asia Minor.'

I t is clear, however, that

the riot was badly orgdnised (see Acts

T h e watchword, 'Great

is Artemis'

raised by the workmen, diverted the excite-

ment of the populace, and the demonstration became

anti-Jewish

(a.

34)

rather than directly and especially

anti-Christian. T h e nationality of Gaius and Aristarchus

(Macedonians, AV

Aristarchus alone Macedonian

according to some few

MSS,

Gains in that case being

the Gains of Derbe of Acts

cp

tend

in the same direction

so

long

as

Paul remained invisible

as, apart from the Romans, the Jews formed the

only conspicuous foreign element in the city, and one

notoriously hostile to the popular cult.

T h e solicitude

of certain Asiarchs (a.

cp Euseb.

4

see

for the apostle

is

significant, as they were

the heads

of

the politico-religious organisation of

the province in the

of Rome and the Emperor

whence we must infer that neither

the imperial

policy nor the feeling

of

the educated classes was

opposed to the new teaching

as yet.

The

speech is virtually an

for the Christians.

I t

is

true that

a

very different view has been

suggested (Hicks,

Expos.

June

cp Rams.

Expos.

July

in which Demetrius the silversmith

is

identified with the Demetrius named

as President of

the Board of Neopoioi

temple-wardens,'

Brit.

Mus.

578).

Hicks supposes that the priests persuaded

the Board to organise the riot, and that the honour voted

in

the inscription to Demetrius and his colleagues was

in recognition of their services in the cause of the god-

dess. Apart from the doubt attaching to the restoration

and t o the date of the decree, the theory

does not show why the priests acted by intermediaries

who were civil not religious magistrates nor how

interests were affected-;.

e . , it involves the assumption

that the author

of

Acts misconceived the situation, and

in recasting his authority altered

into

Further,

in

order to

explain the difference between the friendly attitude

of

the Asiarchs and the supposed hostility of the priests, it

is necessary t o assume that the Asiarchs represented

a

different point of view from that of the native hierarchy.

There is

no

evidence that they represented the point

of

view of the Roman governors, and

they had

themselves previously held priesthoods of local cults

before becoming Asiarchs : they represented the view

of the

classes generally, one which prevailed out-

side Jewish circles wherever Paul preached (for com-

plete discussion, see Rams.

T h e short visit during the voyage from Corinth to

a t the close of the Second journey, and the two

and

a half years' labour there during the Third journey,

together with the interview with the Ephesian elders a t

Miletus

on

the return voyage (Acts

form the

only record of Paul's personal contact with Ephesus,

unless we admit the inferences drawn from the Pastoral

Cp

See

especially Thyatira, where we have, among others,

Possibly classification by trade was

Herod.

tribe being

a

Greekintroduction

;

Rams.

Hist.

1

Cp

85-returns of

stock in trade by Egyptian guilds,

etc.

[The Pastoral Epistles, though they may possibly contain

fragments of genuine letters

of

Paul (worked

with freedom),

See Menadier,

43

EPHOD

('prepare me

also a

lodging'. cp Phil.

2

24)

expresses an expectation of visiting

which inevitably

a

to Ephesus.

I

Tim.

3

that this in-

tention was realised, and perhaps there are hints also of a fourth

visit

:

some reconstruct the fragmentary picture of these years

so

as to give even a fifth

or

a

sixth visit (Conybeare and

2

before the final departure for

by way

of

Miletus and Corinth

4

On

the destruction of Jernsalem the surviving apostles

and leading members of the church found refuge in

Asia, and for

a time Ephesus became virtu-

ally the centre of the Christian world.

and

with Aristion and

the Elder, had their abode here

in

this circle Polycarp passed his youth.

The modern name of Ephesos

is

a

corruption

of

Ayos

the

town

being named in

times from the great Church of

John the Divine

built by Justinian on the site of an earlier edifice

:

its ruins

visible on the height above the modern village (cp

de

I

Rams.

H i s t .

A M ,

This church became

the centre of

a

town,

itself being gradually abandoned.

The plain has thus reverted to its original condition, the miserable

remnant of the population now occupying the site of the sanc-

tuary of Artemis founded by the prehistoric settlers, whilst the

site of the Greek and Roman Ephesus is

a

desert (Rev.

2

See Wood,

Discoveries

at

Ephesus,

1877,

for the excavations

(now resumed in the town

the Vienna Arch.

no. 3677

Class.

Rev.

For history, Curtius,

Gesch.

Top.

1872 but Guhl's

1843

is still valuable. The

of

Wood's

labours

given in

Brit.

Mus.

3.

Consult

also

mann,

Christ.

Weber, Guide

with

good

maps (plan of

Ephesus after Weber in

Handbook

t o

Asia

Murray,

1895, p. 96); good article, with good views and maps, by

dorf Topographische Urkunde aus Ephesos

'),

in

EPHLAL

meaning

?),

a Jerahmeelite name,

I

T h e M T is virtually supported by

[B],

[A]-A,

M

from

A ) ,

but

per-

haps originally theophorous.

Read, therefore,

abbreviated form of

(see

ELIPHELET),

or, more

probably,

(cp

See

and

W.

W.

cp

readings there cited.

S .

A. C.

E

PHOD

in Pent.

Vg.

in Judg. and

I

ephod; in

I

Ch.

but

[L]

in

I

Ch.

Hos. 34

[BAQ]),

a Hebrew word

which the English translators have taken over

as

a technical term.

T h e word

is

used

the historical

books

in two meanings, the connection between which

is not clear.

T h e boy Samuel ministered before

'

girt with

a

linen ephod

I

S.

in the same

garb.

when he brought the ark up

to Jerusalem, danced before

with

all his might

S.

in

I

Ch.

the words are

a gloss).

It was long the accepted

opinion that the linen ephod

was the common vestment

of the priests

but in

I

S.

2218 'linen'

(bad) is

a

gloss (see

a s

also

in

I

and the other

passages usually alleged in support

of the theory speak

of

or

the ephod, not

of

wearing it (see

below,

This ephod

was manifestly a scanty gar-

ment, for Michal taunts David with indecently exposing

himself like any lewd fellow.

It was probably not

a

short tunic,

as is

generally thought,

a loin-cloth

about the waist

Samuel's tunic

is

mentioned separately, and the verb rendered ' g i r d '

is used in Hebrew not of belting

in

outer garment,

but only of binding something (girdle, sword-belt,

loin-

cloth) about the loins ; additional support

is given to

this view by the shape of the high priest's ephod (see

below,

3 ) .

David's assumption of this meagre garb

an occasion of high religious ceremony may perhaps

have been

a

return to

a

primitive costume which

quity had rendered sacred, as the pilgrims to Mecca

are

un-Pauline in language and in theological position, nor can

they he fitted into

a

chronology of the life of

Paul.

See

Julicher

and cp

1306

EPHOD

EPHOD

to-day must wear the simple loin-cloth

see

G

IRDLE

,

I

),

which was once the common dress of the

Arabs.

T h e ephod was used in divining or consulting

Of this

is frequent mention in the history of

Saul and David

( I

S.

1 4

18

:

cp

3

236

g

see also

Hos.

From the passages

I

it appears

that the ephod

carried by the priest

cp

236)

to carry the ephod is the distinction of

the priesthood

one of its chief prerogatives

(228).

W h e n Saul or David wishes to consult Yahwb,

the priest brings the ephod to him he puts

inter-

rogatory which

be answered categorically

or a simple alternative, or a series of

alternatives narrowing the question by successive exclu-

sion

cp

T h e priest manipulated the

ephod in some way

Saul breaks off a consultation by

ordering the priest to take his hand away

T h e

response, a s we should surmise from the form

of the

interrogatory, was given by lot in

(6,

cp

18)

the

lot is cast with two objects, named respectively Urim

and Thummim (see U

RIM

). T h a t the ephod was part

of the apparatus of divination may be inferred also

from its frequent association with the

T

ERAPHIM

(Judg.

Hos.

3 4

cp Ezek.

2121

Zech.

T h e passages

Samuel, whilst leaving

no doubt

concerning the use of the ephod, throw little light upon

its nature.

They show, however, that it was not

a

part of the priests' apparel it was carried, not worn

never means wear

a

garment cp also

236,

in

his h a n d ' ) , and brought

'bring near') to the

person who desired to consult the oracle. Other pass-

ages seem to lead to

a

more positive conclusion. At

Nob the sword of Goliath, which had been deposited in

the temple a s

a

trophy, was kept wrapped up in a

mantle 'behind the ephod,' which must, therefore, be

imagined as standing free

(

I

S.

2 1

Judg.

ephod and teraphim in one version of the story are

parallel

and

(idol) in the other.

It is

natural, though not necessary, t o suppose that the ephod

was something of the same kind, and the association of

ephod with teraphim elsewhere

(Hos.

3 4 )

is thought to

confirm this view.

Gideon's ephod (made of

1700

shekels of gold) set np

cp

I

617

[of the

ark]; c p

a t Ophrah, where, according to the

deuteronomistic editor, it became the object of idolatrous

worship Jndg.

was plainly a n idol, or, more pre-

cisely,

an

of some kind.

Many scholars infer

the ephod in Judg.

8 2 7

and

I

S.

was a n

image of

and some think that a similar

image is meant in all the places cited above where the

ephod is used in

W e should then imagine

a

portable idol before which the lots were cast.

See

below,

3

(end),

4.

I n

P

the ephod is one

of

the ceremonial vestments of

the

Driest enumerated in Ex.

T h e

for the ephod is given in

the

fabrication is recorded

39

(

360

the investiture of Aaron in

,

Lev.

T h e

is not

altogether clear nor do the accounts of those who had

(probably) seen the high priest in his robes afford much

additional

M T

(so

substitutes the

ark

as in

I

K.

226.

See

A

RK

, col.

n.

It

is possible, however, that

has here been substituted

for another word (perhaps

'ark'), for reasons similar

to

those which led

to

omit the words altogether (they have been

introduced in many codd. from Theodotion).

See Moore,

381.

If the words 'before me'

in

I

S .

are original, they

exclude this nypothesis see however

and Pesh.

5

Ecclus.

45

I

O

Heh.;

ed. Schmidt, in Merx,

1

.

Philo

De

Monarch. 2

Mangey)

3

Jos.

v.

5 7

A n t .

7

See also Jerome,

A d

ep.

64

A d

ep.

Braun (De

1698,

whom most

scholars since his day have

held that

ephod con-

sisted of two pieces, one covering

of

the

body

to

a

little

below the waist, the other the hack; two shoulder straps

ran up from the front piece on either side

of

the breastplate

and were attached

to

the back by clasps on the shoulders

hand, woven in one piece with the front of the ephod, passed

around the body under the arms and secured the whole.

Others conceive

of

the ephod as

an

outer garment covering

the body from the arm-pits to the hips, firmly hound

on

by its

girdle, and supported

straps over the shoulders, something

like a waistcoat with a square opening in front for the insertion

of the

This view is incompatible with

descrip-

tions in Exodus, especially with the directions for the making

and the use of the hand

(28

8

27

29

against Braun's theory it

he noted that nothing is said

in

the text about a back piece

nor is there anything

to

suggest that the ephod was made in

parts

; 28

8

again seems to exclude such a construction.

As far as we can now understand the description,

the high priest's ephod appears to have been

a

kind

of

tied around the waist by a band or girth

two broad shoulder-straps

were carried up to

the shoulders, and there fastened (to the robe,

by

two brooches set with onyx

T h e oracle-pouch

E V 'breastplate

of judgment

cp

col.

607)

was permanently attached

by its

corners to the shoulder-straps, filling the space between

them, and

on its lower border meeting the upper edge of

the ephod proper. T h e high priest's ephod may then be

regarded a s a ceremonial survival of the primitive loin-

cloth

bad; see above, §

I)

worn by Samuel and

precisely

as a Christian bishop at one time wore

-as the Pope does still-over his alb a succinctorium

with its

zona,

the two ends falling a t his left

T h e fact that the apparatus of the high-priestly

oracle, the

with the sacred lots, was per-

manently attached to the ephod recalls the use of the

ephod by the priests of Saul and David in divining (see

U

R I M

)

and the most natural explanation is that it

also is

a

survival. This is, of course, impossible

if the

ephod in Samuel was an image (see above,

2 )

but

the latter conjecture

i s

not

so certainly established that

the evidence of P may not be put into the scales against

it.5

Various hypotheses have been proposed to connect

the different meanings and uses of

in the OT.

-

-

from the corners of the apron

4.

Attempted

explanations.

the lots, from

It is possible that the primitive ephod

-a

corner of which was the earliest

pocket-was used a s

a

receptacle for

which they were drawn, or into which

they were cast (see Prov.

1633)

and that when it was

no

longer a common piece of raiment it was perpetuated

this sacred use, not worn, but carried by the priest

the ephod and oracle-pouch of the high priest would

then preserve this ancient association. T h e ephod

of

Gideon- perhaps also the ephod

the temple at

however, an

of an entirely different

character; what relation there may be between the

ephod-garment and the ephod-idol, it is not easy to

In both cases we must admit the possibility

Dillmann

Ex.

I.

Leu.

334:

Nowack, HA

2

Driver in

D B

cp Saadia, Ahulwalid.

The

figures in Lepsius'

(3

224

which

Ancessi, followed by

others, would see an Egyptian

ephod of this form, represent not a ceremonial dress, hut simply

of two familiar

The interpretation 'shoulder-cape

Schulterkleid,' found

in some recent works is

a

mistranslation (through

Old Latin and Vg.

of

which is not

a

garment covering the shoulders, but one open on the shoulders

and supported

brooches or shoulder-straps

3

Rashi (on Ex,

28

40

end) likens the ephod of the

high priest

to a

woman's

two pieces of

cloth,

in front

and behind, on

a

band or

4

See Marriott,

153,

that

the original use of the succinctorium was not forgotten, see

Innocent

De

I

,

The

is that the union of

ephod with the Urim

and Thummim is an artificial combination suggested to the

of

P

the passages in Samuel themselves. P, it is

thought, knew nothing

the

nature of the old ephod

or the Urim and Thummim.

For the etymological explanation by

J.

D. Michaelis, see

below cp also Smend.

A

T

n.

1308

EPHPHATHA

that

has supplanted a more offensive word,

possibly

cp the substitution of

ark,’

for

in

I

I

K.

6, n.

I

.

T h e etymology of

is obscure; the verb

(Ex. 29 Lev. 8

7 )

is generally regarded

as

denominative.

Lagarde’s derivation from

a

root

is formally un-

impeachable ; but his explanation,

garment of ap-

proach to God,’

is

inadmissible

178). J.

D.

Michaelis conjectured that Gideon’s ephod-idol was

so

called because it had

a

coating

Ex. 288

of gold over

a

wooden core (cp Is.

This theory

has been widely accepted, and extended to the whoie

class of supposed oracular ephod-idols but the com-

bination is very doubtful.

Even in Isaiah it is quite

possible that

an actual garment may be meant.

See the authors cited above in the notes, and in Moore,

Older monographs

: R.

D.

ficum

vestitu

6.

Literature.

785

;

dotium

13

of Jewish scholars

in extenso)

cp Maimonides

8

especially

De

6

Spencer, De

Leg.

lib.

diss.

7,

c.

3

;

further,

Ancessi,

de

1872

;

of

ii.

1

van Hoonacker, L e

EPHPHATHA

[Ti.

W H ] ) , an

used by Jesus according

to Mk.

I t is glossed by

and

is

properly the passive (Ethpe’el

or

differ) of

to open.’

The assimilation of the

before can be paralleled

later

Aramaic; but it would perhaps be simpler to suppose that

the older

(correctly)

See Kau.

Gram.

io,

See A

RK

,

Judges, 381.

G.

F.

M.

EPHBAIM

EPHRAIM

Ephraim

on meaning of name see

below,

2

occasionally

or

; on

.

gentilic

Ephraimite, Ephrathite

see

below,

I

[end],

the common

designation in Hosea (originally oftener

than now) of the northern kingdom of Israel. This usage

was not confined, however, tonorthern writers. It

also in Isaiah and Jeremiah and in post-exilic prophets

and

There

is

no evidence that the name was used

by other nations. T h e Moabites called the northern

kingdom Israel

( M I ,

; the Assyrians called it Bit

(cp

or Israel (cp

Nor

does

Ephraim’ in this sense occur in the earlier

historical

T h e explanation probably

is

that it

was

not

a

correct, formal style.

An

orator may speak

of England

a

diplomatist must say Great Britain.’

T h e

of the name suggests that it

is

really geo-

graphical (cp the many place-names ending in

[N

AMES

,

and, for the prefixed

such names

as

Achshaph cp also Achzib).

Land of Ephraim’

it is true occurs only once

late (Judg.

1 2

and ‘Wood of

may be

(see

[W

OOD

‘Mount

occurs over thirty times (cp Mt. Gilead), and it

is

significant

that

never hear of ‘house of Ephraim’ (as we do

of

house

of

See

The

forms occur in Josephus

:

for the eponym

for the

variants

is uncertain.

4

Cp

47

out of Ephraim

a

kingdom of violence

5

Statistics

as to

the oc urrence of the name may now he

found conveniently

in W.

For

we have

19

If the text of these

two words is correct (see N

EGEB

), we must give

the mean-

ing it

has

in Assyrian

‘

mountain

’

(for other cases see

F

IELD

,

I

)

.

The late passage Jndg.

cannot he considered an

exception. The

is

modelled after others.

Against the view that Ephraim is the name of

district the absence of

such a place-name from the

Egyptian records is of

no significance. They mention,

on the whole, towns rather than districts.

Nor

we consider seriously the suggestion (Niebuhr, Gesch.

that there may be in Egypt

a

trace of Ephraim

as

the name of

a

people-viz. in the

repeatedly

discussed in relation to Israel (the Hebrews

cp

H

EBREW

,

I

) ,

since Chabas called attention to them,

in

T h e objections to

such

a

view-initial

for

aleph

and certain facts about

the

obvious

(so,

strongly,

WMM).

The occurrence in a document of Egyptian

for initial

Semitic

is not indeed impossible, as is proved

the

singular case of the similar name Achshaph (see above)

hut

that must be regarded simply

as

a

blunder of the scribe who

wrote the

As.

Bur.

The name

occurs

too

often for there

to

be any uncertainty about its

spelling and it is always with

Nor

there in favour of it any positive argument. We find

the time of

(cp E

GYPT

,

in the (eastern) borders

of Egypt where

a

persistent tradition says that Joseph, which,

as we shall see, is practically equivalent to Ephraim, was

settled (cp

JOSEPH

i.); hut

are mentioned as early

as

the thirteenth and

as

late as the twentieth

and there

is nothing to suggest their being connected with

a

special

movement towards Canaan.

It is most probable, therefore, that ‘Ephraim’

is

strictly the name of the central highlands of

W.

Palestine.

T h e people took the name of the tract in

which they dwelt, just

as their neighbours towards the

were called men of the south,’

of the south

(see B

EN

JAMIN

,

I

) .

Ephraim would thus be simply

the country of Joseph

called his

son, as Gilead is called

the

son

of Machir. It

is

just possible that Machir, too,

was at one time used in

a

wider sense, more nearly

equal to Joseph

story says (Gen.

cp

4 5 4 )

that it was because Joseph was sold

that

he was found living in Egypt

sold

When Josephwas regardedas consisting definitelyof three

collections of

(Manasseh), Ephraim, and

Benjamin-the main body retained the name Ephraim.

The

occurs seldom (Judg.

12

5

I

S. 1

I I

K.

11 26)

in

MT, and the text is doubtful (see below,

Analogy would

lead

us to

expect Epbrite

from

from

but the form used

Ephrathite

as

from

a noun Ephrah.

(Josh.

16

IO

Jndg.

12 4 6

is an invention of EV. ‘Ephrathite’ in Judg.

12 5

is probably genuine

in the sense of belonging

to

Ephraim.

From the days

of

Hosea

(13

and the

Jacob (Gen.

49)

and

of Moses

33)

men

have seen in the name Ephraim

a fitting

designation for the central district

of

fair and open,’ fertile and

well-watered

and modern scholars

We.,

Gesch.

regard the name

as

originally

a Hebrew

omits ‘house of.’ The Chronicler speaks of the ‘sons of

E

Ch.

For

the

see

reff. in

Gesch.

1166

n.

Marq.

57

n.

124.

Another phonetic objection, that medial is normally repre-

sented

f

not

(so

WMM,

As.

is not decisive.

P

also appears, for example,

(pap.

Anast.

22

3).

Brugsch compared the Midianite ‘Epher,

’76,

71).

Achshaph occurs in the list of towns in Upper

of

Thotmes

111.

(no.

normally

as

but in pap. Anast.

i.

21 4

it appears as

(initial

y).

As the Egyptian pronunciation of

was less emphatic

than the Canaanite it might be thought possible that

emphatic

Semitic

should sometimes be represented in Egyptian by

What is found, however, is the converse effect-Egyptian

for Semitic 'sin,-and it is hardly possible to believe that

in the case of people for many centuries in the employment of

the Egyptians a name which was spelled by the Egyptians

y invariably really

with

s

even been

that

is never a race name

(Mcyer,

G A , 297,

n.

Maspero, Hist.

2 443,

n.

3

; but

not

so

Erman W. M. Miiller).

7

The place) of the incident of

sale in the life of Joseph

referred

to

elsewhere. See

3.

E

applies the etymology differently (Gen.

41 52

: ‘fruitful

in the land of my affliction’

and again, Josepbus

6

I

‘restoring’

‘because

of

the restoration

‘to

the freedom of his forefathers.‘

1310

Phonetically, therefore, the equation is indefensible.

EPHRAIM

EPHRAIM

appellative meaning

fertile tract.’

Formally this is

plausible (see above,

I),

and, as we shall see

such

a name

is

fitting- it would be eminently

fitting

on the lips of Hebrew immigrants from the

Steppes.

The Arabs called the beautiful plain of

the

and this has become

a proper

name

Compare the (very different) name

given to the parched tract

S.

of Judah (see

Other possible explanations, however, should not be

overlooked.

ii. If

means

in connecting ‘Ephraim’

with

may have been wrong only in interpreting the termina-

tion

aim

as

a

dual

ending, and Ephraim

meant

the

loamy tract.’

A slightly

explanation would be reached if we

followed the hint of the

Hebrew

(Euxt.

cp

5

7

:

‘Domestic animals

are such

as

pass the

in

the city

pastoral animals

are such

as

pass the night in the open

also

8 6 :

‘[Exod.

34

teaches that thy cow

pasture in the open

If this sense for

was old ‘Ephraim’ might mean the

country where the earlier

in

Palestine had not

yet

(cp below,

7

in the Talmud

means ‘meadow.

O n the other hand, the interpretation of geographical

names is proverbially precarious (cp C

ANAAN

,

6,

I

)

; we must take into consideration the possi-

bility that the name Ephraim as it has reached

us

may

owe its precise form

part to popular etymology such

as,

it is thought, has turned (conversely)

vert

into

(hill).

Ephraim

is

generally called

Mount Ephraim

mountainous-country

of

Ephraim.’

The Assyrian

may he

not

This was no mere form of speech.

From

the plain of Megiddo to Beersheba is

a

great mountainous mass, ninety miles in

length, called the mountain.’

Mountain of Ephraim

will mean that part of this great mountain mass which

lies within the (fertile) tract called

the

northern part. I t

is impossible not to see that Ephraim

differs from the less

tract that extends down to

sheba. The change is patent.

It is more difficult, how-

ever, to say where it occurs (see, further, end of this §).

I n fact, there is not really

a definite physical line of sec-

tion, any more than there was

a

stable political boundary.

I t has been suggested elsewhere (B

EN

J

AMIN

,

that

this made easier the formation of a n intermediate canton

called the southern [Ephraim]

Benjamin. T h e

O T nowhere defines the extent

of

Ephraim.

It

is likely

that there was always

a certain vagueness about its

southern limits.

There can be little doubt, however,

that it included Benjamin (see B

EN

JAMIN

,

I

).

All

that follows the word even in Judg.

19

16

is probably

a n interpolation (to magnify the wickedness of the Ben-

jamites? ;

so

Bu.

ad

T h e northern boundary is

clearer.

When Josephus tells

us

v.

that

Ephraim reached (from Bethel) to the great plain

he may mean the plain not

of

Megiddo

but

of

the Makhneh (see below,

4)

; but he is

of the seat of the smaller Ephraim tribe.

T h e

general character of the O T references and the cities

assigned to Mt. Ephraim (see helow,

13)

make it

probable that it reached to the

of Megiddo.

The only serious argument against

it

is

the rather obscure

passage Josh.

(on the text of which

see

Che.

On the view of Gesenius see later

G. H.

suggests

11

247

that

is

the masculine equivalent

of

an appellation of Rachel, signifying ‘her that

fruitful

(see

R

ACHEL

).

Cheyne has conjectured that the plain below Jerusalem

similarly received

name ‘Ephraim,’ corrupted

transposi-

tion of letters

into

Bethlehem (or

a

place

near it), only two

or

three miles distant, seems

to

have been

called

So

Barth,

comparing Ar.

which,

however, means

‘dust

.

also

Twice ‘mount

Josh. 11 1621

on Ezekiel’s

frequent ‘mountains of Israel’

see

P

L

AC

E

,

Looked

at

from the sea indeed or from across the Jordan,

it ,‘presents the aspect,’

as

6.

A.

says, ‘of

a

single

1311

cp

R

E

PHAIM

). The house of Joseph, complaining that Mt.

is

too small for them, are told

to

clear for themselves

settlement in the

wood

in the land of the Rephaim and

the

has been supposed that this refers

to

the northern

of the western highlands from Shechem

to

Jenin

van

p.

is

more

that the passage is to be connected with the

of

colonies settling E. of

t h e

Jordan (cp

etc.;

[WOOD]);

SO

87

Buhl,

n.

265).

See

and, on the

of Ephraim to other tribes, hclow,

5.

T h e places expressly said to be in Mount Ephraim

we

:

in the south,

perhaps

(see

Zuph, and Timnath-heres (Josh.

50

Judg.

perhaps et-Tibnah (see

HE RE

S

)

; in the centre, Shechem (Josh.

2121

I

12

25

I

6

67

in the

Judg.

10

I

)

also the hills Z

EMARAIM

,

of Bethel

( 2

Ch.

and G

AASH

, near Timnath-heres (Judg.

etc.

).

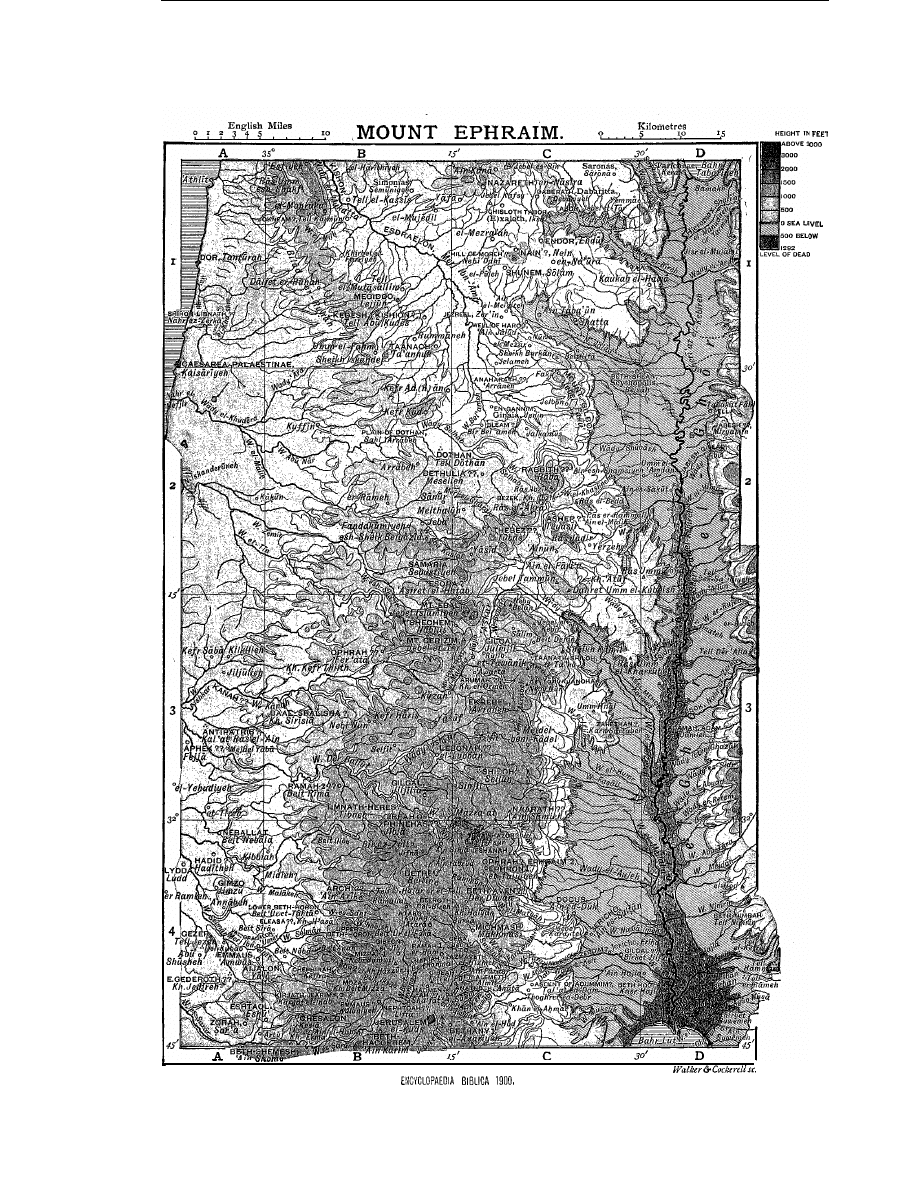

T h e Ephraim highlands differ from those of Judah

in several respects.

I n Judah we have a compact and

fairly regular tableland deeply cut by steep defiles,

bounded on the

E.

by the precipices that overlook the

of the Dead Sea, and separated on the W . from

the maritime plain by the isolated lowland district of

the

(see

I n Ephraim thisgives place

to

a

confused complex of heights communicating

on

the

E.

by great valleys with the Jordan plain,

and letting

itself down by steps

on

the W . directly

on

to the plain

of Sharon, cut across the middle by

a great cleft (see

helow,

4, end) and elsewhere by deep valleys, and en-

closing here and there upland plains surrounded by hills.

The change in the western border occurs about WHdy

directly west of Bethel; the change in the

character of the surface not till the Bethel plateau ends

(some

5

or 6

m. farther N.) a t the base of the highest

of Ephrain- on which the ruins of

probably mark the site of BAAL-HAZOR-whose waters

running east through the

W.

and west through

the

W.

en-Nimr and the

W.

empty

selves into the Jordan and the Mediterranean by the

two

Geographically,

as

well as historically, the heart and

centre of the land

is

Shechem.

Embosomed in

a

forest of fruit gardens’ in

a

fair vale

sheltered by the heights of Ebal and

Gerizim, it sends out its roads, like

arteries, over the whole land, distributing the impulse

of its contact with foreign culture.

I.

Northwestwards the

W.

esh-Sha‘ir winds past the

open end of the

plain down to Sharon.

From the plain of

whose island city-fortress the

sagacity of Omri made for centuries the capital, one gets by

valley up

to

near

and

then down the W.

or

by

a

road over the saddle of

into the upland

of

and

and on to

Dothan, and the plain of Megiddo.

2.

T h e

E.

end of the vale

of Shechem

is

the plain

of

‘Askar.

If one turns

to

the left, the steep, rugged gorge

of

W.

(with its precipitous cliffs, surmounted by

on

the

left

by Neby

on the right)

tales

one down northwards

to

the

great crumpled

which collects the waters

of

the

W.

the main avenue of access from

the ford of

less than

m.

o f f .

Straight on (NE.)

past

the road

to

in

the Jordan plain,

passing by the large village of

(identified

by some with

which

lies

m. from