HEATHEN

HEBREW LANGUAGE

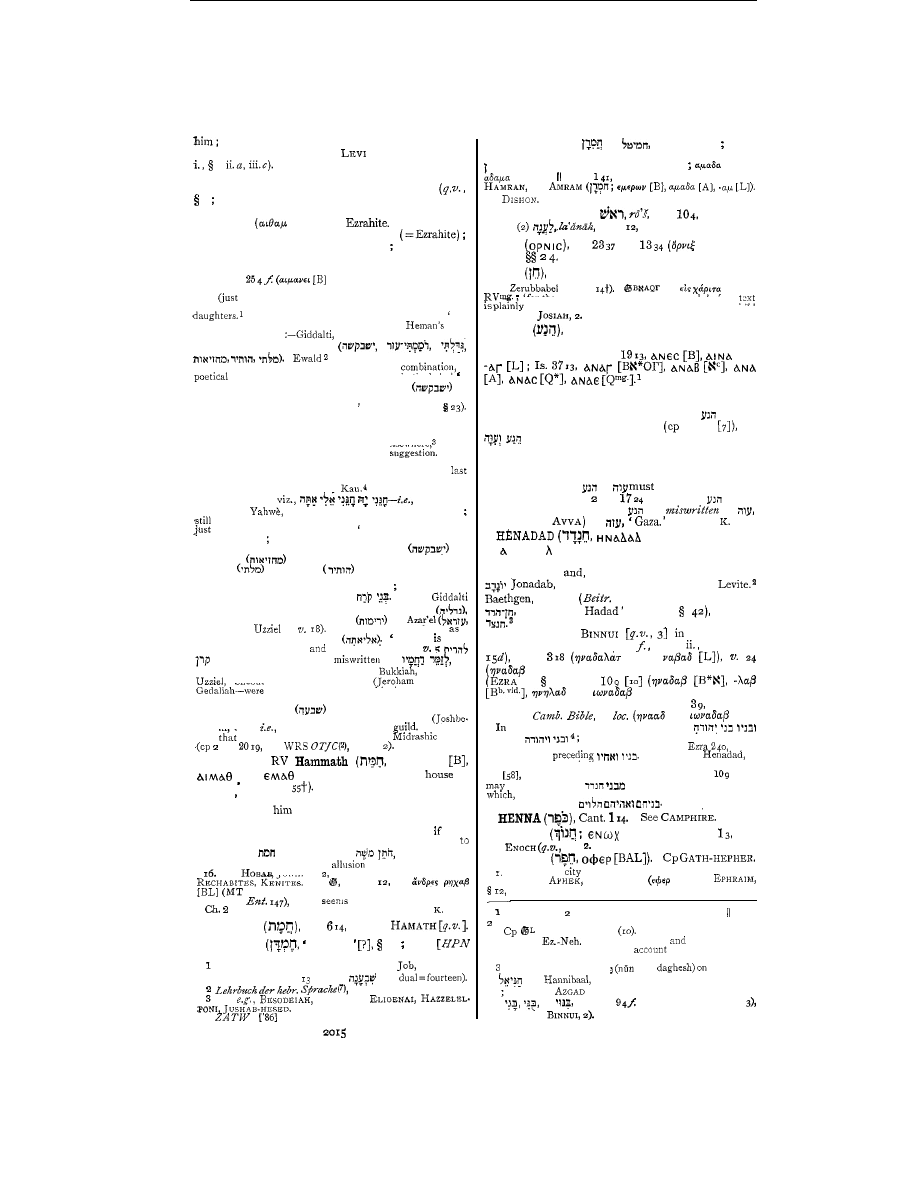

7

Heberites

in Nu.

2645

The clan is called the

Jastrow

The form

Jer. 486-for which

read

(implied in

most naturally

as

a

‘broken plural’ of

Lag.

Barth’s view of it

as

a

sing. adjectival form

is

likely. ‘Tamarisk’ is the rendering of

in Jer.

1 7 6

of Aq. in Jer.176 (in 486

and

of Vg.

;

Tg. has in the former place

edible

thistle but in the other takes

to be a proper

(so

Pesh.

renders by

root

in both places.

T h e plant intended i s almost certainly

a

juniper,

as

that is the meaning of

Ar.

a n d the most likely

sort is, according t o Tristram

the

L.,

or

Savin.

This tree abounds o n the

rocks above Petra, where

as

Robinson

(BR

2

says,

it grows t o

the

height of

I O

or

feet, a n d hangs upon

t h e rocks even

to t h e summit of the cliffs a n d needles.

Its gloomy stunted appearance, with its scale-like leaves

pressed close to its gnarled stem, and cropped close by the wild

goats,

great force to the contrast suggested by the

Tristram adds ‘There is no true heath in Palestine

Lower

Hooker states that this particular

plant is still called

by the Arabs.

[The

or juniper, has been found in

I

S.

20

41

(crit. emend.), where David is said to have sat down

a

juniper tree, while Jonathan shot arrows at three prominent

rocks near. The passage gains in picturesqueness.

i n

should be

;

was originally

and intended

as

a correction of

see Che.

Bib. and cp

See also A

ROER

.

N.

M.

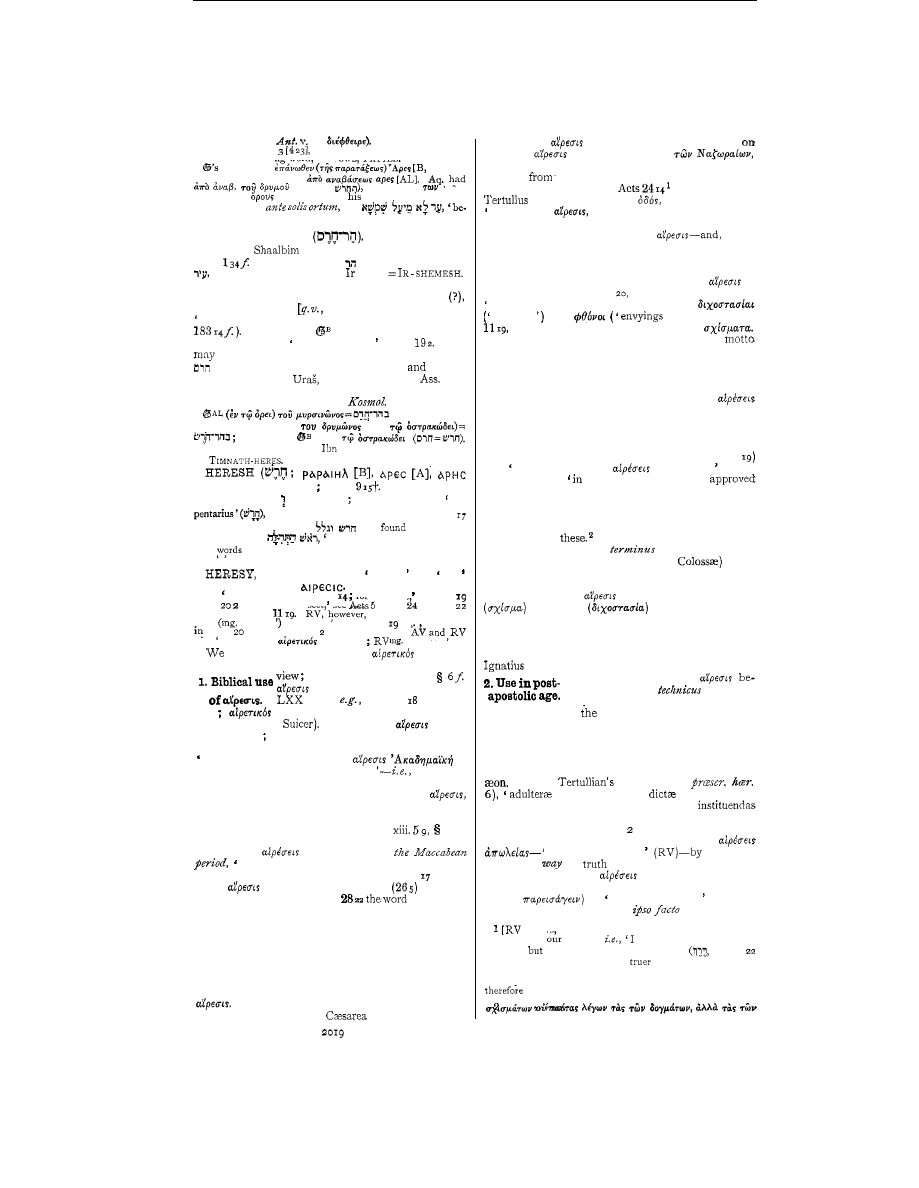

HEATHEN

Therendering

is

plainly

wrong i n

AV of Lev.

2544

2 6 4 5 ,

but is admissible when

or

is

used of nations whose religion is

neither Jewish,

nor Jewish-Christian, nor Christian,

with consciousness of this fact.

Cp Sanderson

Abimelech, an heathen-man, who

not the knowledge of the true God of heaven to direct him

.

Caxton, Pref. to Malory’s

‘in

places

and

Possibly the Gothic original of ‘heathen’may he

traced to Armenian

an adaptation of Gk.

though

stem-vowel seems to have been assimilated to

‘heath’ (Murray,

Dict.).

O n

the various Hebrew conceptions of

a

heaven

as

the abode of supernatural beings a n d (later)

of

the risen dead,

see

E

SCHATOLOGY

, a n d c p

E

ARTH

AND WORLD,

E

ARTH

[F

O

U

R

QUARTERS], PARADISE.

The usual Hebrew term is

not dual ;

I

but

is used also by

to

render

Ps.

77

18

(RV, whirlwind,’ see W

INDS

), and

37

(KV

‘sky’).

In the N T besides

the

only feature which calls for remark is the reference

to

a belief in

a

plurality

of

heavens

Eph.

1 3

26

3

IO,

etc.),

probably due to Persian influence ; see especially Charles,

of

Enoch,

See

E

LEMENTS

,

2.

etc.).

See

S

ACRIFICE

,

a n d c p

T

AXATION

AND

T

RIBUTE

.

HEBEL

Josh.

n.

HEBER

but

in

Nu.

[BAL] ;

see

N

AMES

,

70).

I

.

The

husband of

JAEL

.

a n d head

of a

Kenite

sept which separated from the main body of

the tribe

(see K

ENITES

), a n d in the course of its nomadic wander-

ings went

as

far north a s

a

certain sacred tree near

(see Z

AANAIM

,

T

HE P L A I N OF)

Judg.

411

[B])

17

In

Judg.

[A])

he has

been introduced b y a glossator.

( A s .

c p

connects

with

Kina, mentioned in the

Pap.

Anastasi, a n d apparently

E.

of Megiddo

(see

Jensen,

Z A

a n d c p A

MALEK

).

T h u s

there

is

an

apparent

coincidence between Heber of

K i n a , a n d the eponym of the neighbouring tribe of

(see

2

below)..

The eponym of an Asherite clan ; Gen. 46

17

Nu.

and

I

Ch.

See

HEAVEN.

HEAVENLY BODIES

Pet.

3

HEAVE OFFERING

See

JETHRO.

Of the

Arab. Gram.,

connects this name with the Habiri of the Amarna tablets (cp

his view on

11

;

so

also

Hommel,

A N T , 235

260

n. This is

See

A clan in Judah the ‘father’ of Socoh

( I

A Benjamite

Ch.

8

;

I

Ch.

5

I

Ch.

8

Lk.

3 35.

I .

See E

BER

(3).

See E

BER

(4).

See

E

BER

(I).

A clan in

the ‘father’ of Socoh

See

I

.

A Benjamite

Ch.

8

;

I

Ch.

5

See E

BER

I

Ch.

8

Lk.

3 35.

See E

BER

See

E

BER

(I).

Ch. 4

HEBREW

T h e name

Hebrew

Gr.

is

a

transcription of

the Aramaic equivalent of the original O T

word

pl.

which is the

proper

name of the people who also

bore the collective name of

Israel

or

Children of Israel

Israel).

The

name of Israel with its sacred

associations in t h e patriarchal history is that

which

the

OT

writers prefer

to

designate their nation

a n d

this circumstance, combined with

the fact that the term

Hebrews is frequently employed where foreigners a r e

as

speaking

or spoken

to

Ex.

26

I

S.

Gen.

Ex.

has led t o the conjecture that

the name of Hebrews (men from the

other

side,

of

the Euphrates)

was

originally given

to

the descendants

of Abraham b y their Canaanite neighbours, a n d con-

tinued to

be

the usual designation of the Israelites among

foreigners, just

as

the Magyars

are

known t o other

Europeans

as

Hungarians (foreigners), a s

we

call the

High-Dutch Germans (warriors),

or

as t h e Greeks gave

the

name of

to

the people that called them-

selves

A

closer view of the case, does not

confirm this conjecture.

[Stade’s theory however,-that the Israelites were called

Hebrews, after

passage of the Jordan, in contradistinction

to

the other West- Jordanic peoples, though connected with a

historical theory not borne out by the (later) Israelite tradition

-is still maintained by its author,

Akad.

p

IIO.

As

to the Habiri of Am. Tal, Wi.

defends

view that the people so-called

nomads from the other side of the Jordan, such as the Suti

or

pre-Aramaic

the Syrian desert. These nomads were

the

‘Hebrews.

But cp Hommel,

Nor has the word Hebrew been hitherto found in the early

monuments of other Eastern nations [unless indeed the Habiri

of the Am. Tab., who give such trouble to

of Jeru-

salem, may be identified with the Hebrews-a theory which in

its

newer form deserves consideration]. The identification pro-

posed by Chabas which finds the Hebrews in the hieroglyphic

Apuriu is more than

whereas the name of Israel

appears

on

the stone of Mesha, king of Moab

7), and perhaps

has been deciphered

Assyrian monuments.5

[On

the

of this name in an old Egyptian inscription, see E

XODUS

The

form

is, in the language of Semitic gram-

marians,

a

relative noun, presupposing

the

word ‘Eber

a s the name of

the tribe, place,

or

common ancestor,

from whom

the Hebrews are designated.

Accordingly we find Eber as a nation side by side with Assyria

in the

poetical passage Nu. 24

24,

and Eber as ancestor

of the Hebrews in the genealogical lists of Gen.

Here we

must distinguish two

According to Gen.

11

(and Gen.

Eber is the great-grandson of Shem through Arphaxad

and the ancestor of Terah through Peleg Reu Serug and

These are not to be taken as the names

men.

Several of them are designations of places or districts near the

upper waters of the Euphrates and the Tigris, and among other

circumstances the place at the head of the series assigned to the

district of

(see, however,

through

which

a

migration from Ararat to the lands occupied by

Semites in historical times would first pass, suggests the prob-

ability that the genealogy is

not

even meant to exhibit

a

table

See

For these forms we may compare the way in which the river

Hebrew

is dealt with in the following articles:-

H

ISTORICAL

L

IT

., P

ROPHETICAL

L

IT

., L

AW

On the labours of the

3

See especially Ces.

Gesch.

der

;

4

See E

GYPT

,

;

I .

Schr.,

defends this not undisputed reading;

See b e Goeje in

T,

243

and We. in

is in one place transliterated

and in another

P

OETICAL

L

IT

.

L

IT

.,

E

PISTOLARY

L

IT

.

Masoretes see W

RITING

, T

EXT

.

more recently

in Riehm’s

A

HAB

4.

’76, p.

395.

HEBREW

LANGUAGE

of ethnological affinities, but rather. presents

a

geographical

sketch of the supposed early movements of the Hehrews who

are personified under the name of Eher. If this is

so,

can

hardly venture to assert (with some scholars) that the author of

the list (the Priestly Writer) extended the name of Hehrews to

all descendants of

The case is different with another (doubtless older) record

of

which a fragment seems

to

be preserved in Gen.

Here there is no intermediate link between Shem and Eber.

Sons

of

Shem and

sons

of Eher appear to be co-extensive ideas,

and to the latter are reckoned

only the descendants of Peleg

(Aramzeans, Israelites,

Arabs, etc.), hut also the

South Arabian tribes of Joktan.

As to the etymological origin

of

the name of Hebrews

we have

an early statement in Gen.

1413,

where

renders Abram the Hebrew [see Di.] by

6

‘

the crosser.

Grammatically more accurate while resting

on

the same ety-

mology is the rendering of

‘the man from

the

side’ of the Euphrates,

is thb explanation of

Jewish tradition (Ber.

R.,

and Rashi); cp Ew.

( E T

1284).

however, ‘takes

in the Arabic sense

of

a river

hank and makes

Hebrews ‘dwellers in a land of rivers’

goes well with Peleg (watercourse)

as

i n

Arabia we have the district

so

named because

is

furrowed by waters (Sprenger,

By the Hebrew language we understand the ancient

tongue of the Hebrews in Canaan-the language in

which the

OT

is composed, with the ex-

ception

of

the Aramaic passages

10

I

T

Ezra

Dan.

We

d o

not find, however, that this language

was

called Hebrew by those who spoke it.

I t

is

the

Zip-

Canaan

(Is.

or,

as

spoken in

southern Palestine,

K.

Is.

Neh.

T h e later

Jews call it the

tongue

in contrast t o the

profane

Aramaic dialect (com-

monly though improperly enough called Syro-Chaldaic)

which long before the time

of

Christ had superseded

the old language

as

the vernacular of the Jews.

This

change had already taken place at the time when the

in Hebrew

first occurs (Prologue

t o

Sirach) and both in the Apocrypha and in the

N T

t h e ambiguous term,

the language after those

who used it, often denotes the contemporary vernacular,

not the obsolete idiom of the OT.

T h e other sense,

however, was admissible

Rev.

and

so

fre-

quently in Josephus), and naturally became the prevalent

one among Christian writers who had little occasion t o

speak of anything but the

OT

See

A

RAMAIC

L

A

NGUAG

E

.

Hebrew is a language of the group which, since

horn, has generally been

as Semitic, the affinities

of the several members

of

which are

so

close that they may fairly be compared

with

a

sub-group of the Indo-Germanic

family-for example, with the Teutonic languages.

T h e fundamental unity of the Semitic vocabulary is

easily observed from the absence of compounds (except

i n proper names) and from the fact that

all

words are derived from their roots in definite patterns

(measures)

as regular

as

those of grammatical inflection.

T h e roots regularly consist

of three consonants (seldom

four

or

five), the accompanying vowels having n o

radical

but shifting according to grammatical

rules to express various embodiments of the root

idea.

T h e triliteral roots are substantially

to the

whole Semitic group, subject to certain consonantal per-

mutations, of which the most important are strikingly

The Terahites, according

to

other testimonies, are Aramzeans

22

Dt.

j);

but the Priestly Writer, who cannot be

pre-exilic, makes Aram a separate offshoot of Shem, having

nothing to do with Eber (Gen.

Cp Jerome,

Quest.

on the passage, and Theodoret,

The term ‘Hebrew

to have originated with

the Grreks or Hellenists. Philo however calls the languageof

the OT Chaldee

(De

2

Jerome on Dan.

the use of the expression

language in the

see

Berliner,

(Berlin,

Cp

HEBREW

LANGUAGE

analogous

to

those laid down by Grimm for the Teutonic

languages.

There are in Arabic four aspirated dentals, which in Hebrew

and Assyrian are regularly represented

sibilants, as follows

:-

Arabic

A

I

.

Ar.

In most of the

dialects the

first

three of these sounds

are represented by

and

respectively, while the fourth

is usually changed

into

the guttural sound

But it would

appear from recent discoveries that in very ancient times some

a t least of the Aramaic dialects approximated to the Hebrew and

Assyrian as regards the treatment of the first three sounds, and

changed the fourth into (cp

beginning, and see

below,

Derivation from the roots and inflection proceed partly

by the reduplication of root letters and the addition

of

certain preformatives and afformatives

(more rarely by the insertion

of formative

consonants in the body of the root), partly

by modifications of the vowels with which the radicals

are pronounced.

I n its origin almost every root ex-

presses something that can be grasped by the senses.

The mechanism

which words are formed from the root is

adapted to present sensible notions in

a

variety of nuances and

in all possible embodiments and connections,

so

that there are

regular forms to express in a single word the intensity, the

repetition, the production of the root idea-the place, the instru-

ment, the time of its occurrence, and

so

forth. Thus the ex-

pression of intellectual ideas is necessarily metaphorical, almost

every word being capable of

a

material sense,

or

a t least con-

veying the distinct suggestion of some sensible notion. For

example, the names of passions depict their physiological ex-

pression ;

‘

to confer honour’ means also

‘

to make heavy,’ and

so

on.

T h e same concrete character, the same

to convey purely abstract thoughts without

a substratum

appealing to the senses, appears in the grammatical

structure

of the Semitic tongues.

This is

to

be seen, for example in the absence

of

the neuter

gender, in the extreme paucity

particles in the scanty pro-

vision for the subordination of propositions

’

which deprives the

Semitic style of all involved periods and

it to

a

succession

of short sentences linked by the simple copula and.

T h e fundamental element

of

these languages is the

noun, and in the fundamental type

of sentence the

predicate is

a noun

set down without any copula and

therefore without distinction of past, present, or future

time.

T h e finite verb is developed from nominal forms

(participial or infinitive), and is equally without dis-

tinction

of time.

Instead of tenses we find two forms,

the perfect and the imperfect, which are used according

as

the speaker contemplates the verbal action as

a

thing

complete or

as

conditional, imperfect, or in process.

It lies in the nature of this distinction that the imperfect alone

bas moods. In their later stages the languages seek to supply

the lack of tenses by circumlocutions with a substantive verb and

participles.

Other notable features (common to the Semitic

tongues) are the use of appended suffixes to denote the

possessive pronouns with

a substantive, or the accusative

of

a

personal pronoun with a verb, and the expression

of the genitive relation by what is called construction

or annexation, the governing noun being placed im-

mediately before the genitive,

if possible, slightly

shortened in pronunciation

so

that the two words may

run together

as

one idea.

A characteristic

of

the later stages of the languages

the

resolution of this relation into a prepositional clause.

These and other peculiarities are sufficient to establish

the original unity

of the group, and entitle us to postu-

late an original language from which all the Semitic

dialects have sprung.

Of

the relation of this language to other linguistic stems,

especially to the Indo-Germanic

on

the

E.

and the North-

African languages

on

the W. we cannot yet speak with certainty

:

but it appears that the present system of

roots has

grown out of an earlier

system which,

so

far as it can

be reconstructed, must form the

of

scientific inquiry

into

the ultimate affinities of the Semitic

4

[See Cook Aramaic

Renan,

sketches the history of

Noteworthy are the remarks

of

On survivals from the

stage,

research

in

this direction.

Lagarde,

see

96.

1986

HEBREW LANGUAGE

Before the rise of comparative philology it was

a

familiar opinion that Hebrewwas the original

speech of mankind.

Taken

from

the Jews, and as already expressed

in the Palestinian Targum

on

Gen.

11

I

,

this opinion drew its

main support from etymologies and other data in the earlier

chapters of Genesis, which, however, were as plausibly turned

by Syriac writers in favour

of

their own

Till recent times many excellent scholars (including

Ewald) claimed for Hebrew the greatest relative antiquity

among Semitic tongues.

I t

is now, however, generally

recognised that in grammatical structure the Arabic,

shut up within its native deserts till the epoch of Islam,

preserved much more of the original Semitic forms than

either Hebrew or Aramaic.

In its richer vocalisation in the possession of distinct case

in the use for

nouns of the

which

in the northern dialect has passed through (originally

as

in Egyptian Arabic) into a mere vowel

in

the more extensive

range of passive and modal forms, and

other refinements

of

inflection Arabic represents no later development

but

the

original

and primitive subtlety

of

Semitic

as

appears not only from fragmentary survivals

in

the other

but also from an examination of the process of decay which

brought the spoken Arabic

of

the present day into a grammatical

condition closely parallel to

OT Hebrew.

Whilst Arabic

is

in many respects the elder brother,

it is not the parent of Hebrew or Aramaic.

Each

member of the group had

an independent development

from

a

stage prior to any existing language, though it

would seem that Hebrew did not branch

off

from

Aramaic

so

soon as from Arabic, whilst in its later

stages it came under direct Aramaic influence.

[On the relation which Hebrew bears to the other Semitic

languages, see Wright,

.

Driver,

Tenses

and

N

art. Semitic Languages

in

published

separately

in

German, with some additions

(Die

T h e Hebrew spoken by the Israelites

in

Canaan was

separated only by very minor differences (like those of

our provincial dialects) from the speech of

neighbouring tribes.

W e know this

so far

as the Moabite language is concerned from

the stone

of Mesha and the indications furnished by

proper names, as well a s the acknowledged affinity of

Israel with these tribes, make the same thing probable

in

the case of Ammon and Edom.

More remarkable

is

the fact that the

a n d Canaanites, with whom

the Israelites acknowledged

no

brotherhood, spoke a

language which, a t least

as

written, differs but little from

biblical Hebrew.

This observation has been

in

support of the very old idea that the Hebrews originally

spoke Aramaic, and changed their language in Canaan.

An exacter study of the Phcenician inscriptions, how-

ever, shows differences from Hebrew which suffice to

constitute

a

distinct dialect, and combine with other

indications to favour the view that the descendants of

Abraham brought their Hebrew idiom with them.

I n

this connection it

is

important to observe that the old

Assyrian, which preceded Aramaic in regions with which

the book of Genesis connects the origins of Abraham, is

Theodoret

(Quest.

in

11)

and others cited

by Assemani

Bib. Or.

same

Conversely Jacob

of Sarug concedes the priority of Hebrew (see ZDMG

The

whose language is in many points older than either,

yield priority to Hebrew (Ahulfeda,

H A

or

t o

Syriac (Tabari

Abu 'Isa

i n

Ahulfeda,

the language of

race

which they owed their first knowledge

of

letters.

That the case endings in classical Arabic are survivals of a

system of inflection can

be doubted. It does

not necessarily follow, however, that

in

the primitive Semitic

language these terminations were used for precisely the same pur-

poses as in Arabic. Moreover, the three Arabic case-endings

commonly called by European scholars the nominative, genitive,

and accusative, do not by any means correspond exactly, as re-

gards their usage, to the respective cases in the Indo-European

languages that is

to

say, the Arabic language sometimes employs

the accusative where we should, on logical grounds, have ex-

pected the nominative and

vice

These apparent anomalies

are probably relics

of

a time when the use

of

the case-endings

was determined by principles which differed,

t o

a considerable

extent, from those known

t o

the Arabic grammarians.

'the

Jews (Rab in

HEBREW LANGUAGE

in many respects closely akin to

[Certain

inscriptions, moreover, recently discovered a t Zenjirli,

in

the extreme N. of Syria, are written in a dialect which

exhibits many striking points of resemblance to Hebrew,

although it would seem,

on

the whole, to belong to the

Aramaic branch.

As

the origin of Hebrew is lost in the obscurity that

hangs over the early movements of the Semitic tribes,

so

we

know very little of the changes which the language

underwent in Canaan. T h e existence of local differences

of speech is proved by Judg.

1 2 6 ;

but the attempt to

make out in the

O T

records

a

Northern and

a

dialect, or even besides these

a

third dialect for

Simeonites of the extreme

has led to

no

certain

results.

In

generalitmaybesaid that

text supplies

inadequate data for studying the history of the language.

Semitic writing, especially

a purely consonantal text

such

as

the

O T

originally was, gives a n imperfect picture

of the very grammatical and phonetic details most likely

to vary dialectically or in course of time.

The later punctuation (including the notation of vowels

:

see below,

$3

g,

and W

RITING

) and even many things in the

present consonantal text, represent the formal pronunciation

of

the Synagogue as it took shape after Hebrew became a

dead language-for even

has often a more primitive

pronunciation

of

proper names (cp

$3

This modern

system being applied to all parts of the OT alike, many

archaisms were obliterated

or

disguised, and the earlier and

later writings

resent in the received text a grammatical

uniformity

is

certainly not original.

It

true that

occasional consonantal forms inconsistent with the accompany-

ing vowels have survived-especially in the books least read

the Jews-and appear in the light of comparative grammar

as

indications

of

more primitive forms. These sporadic survivals

show that the correction of obsolete forms was not carried

through with perfect consistency; but it is never safe

t o

argue as if we possessed the original form

of

the texts

W

RITING

).

T h e chief historical changes in the Hebrew language

which we can still trace are due t o Aramaic influence.

T h e Northern Israelites were in

Immediate contact with

populations and some Aramaic loan-

words were used, a t least in Northern Israel, from

a

very early date.

At the time of Hezekiah Aramaic

seems t o have been the usual language of diplomacy

spoken

by

the statesmen of Judah and Assyria alike

( 2

K.

After the fall of Samaria the Hebrew

population

of

Northern Israel was partly deported,

their place being taken by new colonists, most of whom

probably had Aramaic as their mother-tongue.

It

is

not therefore surprising that even in the language

of

increasing signs of Aramaic influence appear

before the

T h e fall of the Jewish kingdom

accelerated the decay of Hebrew

as a

spoken language.

N o t indeed that those of the people who were trans-

ported forgot their own tongue

in

their new home,

as

older scholars supposed

on

the basis of Jewish tradition

:

the exilic and post-exilic prophets do not write in

a

lifeless tongue.

Hebrew was still the language of

Jerusalem in the time of Nehemiah

( 1 3 2 4 )

in the

middle

of the fifth century

After the fall

of

Jerusalem, however, the petty Jewish people were

in daily intercourse with

a

surrounding

See Stade's essay on the relation of Phcenician and Hebrew

with

ZDMG,

29

also the latter's article, Sprache, hebraische,

in

5

One of these inscriptions, set up by Panarnmii, king

of

Ya'di, probably dates from the ninth

or

the beginning of the

eighth century

Two other inscriptions set up by a king

named

belong

to

the latter half of the eighth cen-

tury. See

A

RAMAIC

L

ANGUAGE

,

$3

in

addition to the works

on the subject which are

specified the reader

consult

Lidzbarski's

der

On the difficulty

of

drawing precise inferences from this

narrative see Marq.

pp.

Bottch.

d . kebr.

('66).

5

,Details in Ryssel De

sic,

the most

collection ofmaterialssince Gesenius,

Gesch. der

An argument

to

the contrary drawn by Jewish interpreters

from Neh.

88

rests on false exegesis.

1988

HEBREW LANGUAGE

population, and the Aramaic tongue, which was the

official language of the western provinces of the Persian

empire, began to take rank

as

the recognised medium

of polite intercourse and letters even among the tribes

of Arabic blood-the Nabataeans-whose inscriptions in

the

are written in Aramaic.

Thus Hebrew

as

a

spoken language gradually yielded to its more power-

ful neighbour, and the style of the latest

O T

writers

is

not only full of Aramaic words and forms but

also

largely coloured with Aramaic idioms, whilst their

Hebrew has lost the force and freedom of

a

living

tongue (Ecclesiastes, Esther, some Psalms, Daniel).

Chronicler no longer thoroughly understood

Old Hebrew sources from which he worked, while for

the latest part of his history he used

a

Jewish Aramaic

document, part of which he incorporated in the book of

Ezra.

Long before the time of Christ Hebrew

was the

exclusive property of scholars.

About

zoo

B.

Jesus the son of Sirach (Ben

a

Palestinian Jew, composed in Hebrew the famous

treatise known in the West

as

Ecclesiasticus.

A

large

portion of the original text has .recently come to light,

unfortunately in a mutilated condition.

Though Ben

uses

a

considerable number of late ‘words, mostly

borrowed from the Aramaic, the general character of

his Hebrew style is decidedly purer and more classical

than that of some parts of the

O T

Ecclesiastes),

and ‘it is specially to be noted that the recovered frag-

ments,

as

far

as

is known at present, contain not

a

single word derived from the Greek.

See

E

CC

LESI

-

ASTICUS.

Several other books of the Apocrypha appear to be

translated from Hebrew originals- Judith,

I

the last according t o the express

mony

of

Jerome.

I t is certain that the

OT

canon contains elements

as

late

as

the epoch of national revival under the Maccabees

(Daniel, certain Psalms), for Hebrew was the language

of religion

as well

as

of scholarship.

As for the

scholars, they affected not only to write but

also

t o

speak in Hebrew

they could not resist the influence

of the Aramaic vernacular, and indeed made no attempt

t o imitate the classical models of the OT, which neither

furnished the necessary terminology for the new ideas

with which they operated, nor offered in its forms

constructions

a

suitable vehicle for their favourite pro-

cesses of legal dialectic. Thus was developed

a

new

scholastic Hebrew, thelanguage of the wise’

preserving some genuine old Hebrew words

happen

not to be found in the

OT,

and supplying some new

necessities of expression by legitimate developments of

germs that lay in the classical idiom, but thoroughly inter-

penetrated with foreign elements, and

as

little

fit

for

higher literary purposes

as

the Latin of the mediaeval

schoolmen. T h e chief monument of this dialect is the

body of traditional law called the Mishna, which is

formed of materials of various dates,

was collected

in its present form about the close

of

the second century

A.D.

(see

L

AW

L

ITERATURE

).

[A

remarkable feature in the Hebrew of the Mishna

is the large use made of Greek and even of Latin words.

That these words were actually current among the Jews of

the period and are

not

mere literary embellishments (as

some-

times the case with Greek words used by Syriac authors) appears

from the fact that they often present themselves in strangely

distorted forms-the result of popular mispronunciation.]

T h e doctors

of

the subsequent period still retained

some fluency

the use of Hebrew; but the mass of

their teaching preserved

the

is

The language of the Mishna has been described by Geiger,

’45);

L.

Die

der

and

(Vienna,

J. H.

(Vienna, ‘67).

HEBREWS, EPISTLE

During the Talmudic period nothing was done for

the grammatical study of

old language but there

was

a traditional pronunciation for the

synagogue, and a traditional interpretation

of the sacred text.

T h e earliest

of Jewish interpretation is the Septuagint

but the final form of traditional exegesis is embodied in

the

or Aramaic paraphrases, especially

in the

more literal Targnms of Onkelos and Jonathan, which

are often cited by the Talmudic doctors.

Many things

in the language of the O T were already obscure,

and

the meaning of words

was

discussed in the schools,

sometimes by the aid of legitimate analogies from

living dialects,’ but more often by fantastic etymological

devices such

as

the

or use

of analogies from

shorthand.

T h e invention and application of means for preserving

the traditional text and indicating the traditional pro-

nunciation are spoken of elsewhere (see W

RITI

N

G

,

T

EXT

).

T h e old traditional scholarship declined, however, till

the tenth century, when a revival

of Hebrew study under

the influence of Mohammedan learning took place among

the Arabic-speaking Jews (Saadia of the

ben Sarug,

Then, early in theeleventh

century, came the acknowledged fathers of mediaeval

Jewish philology,-

the grammarian Judah surnamed

discoverer of the system

of triliteral

and the lexicographer

ibn

(Rabbi Jonah), who made excellent use of Arabic

analogies

as

well

as of

the traditional

A succession

of

scholars continued their work, of whom

the most famous are Abraham ben

of

Toledo, suknamed

Ihn Ezra-also written

a

man

of

great

originality and freedom

of

view Solomon

of

Troyes,

called Rashi

and some-

times by error

of

‘luna’)-(died

whose writings are

a

storehouse

of

traditional lore

;

and David

of

Narbonne, called Radak

whose comment-

aries,’ grammar, and lexicon exercised an enormous and lasting

influence.

Our

own authorised version bears the stamp of

Kimhi on every page.

In the later Middle Ages Jewish learning was cramped

by a narrow Talmudical orthodoxy but a succession

of scholars held their ground till

and others

of his age transmitted the torch to the Christian uni-

versities.

now in preparation, will for English

readers give an adequate account of the Jewish scholars and

their

work.

The portion dealing with Philology will be

tributed by Prof.

F.

Moore.]

W.

R.

A.

B.

HEBREWS

(

Gen.

40

etc. See above a n d

c p

I

SRAEL

,

I

.

HEBREWS

(EPISTLE).

T h e

N T

writing

usually

known under the name of the Epistle to the Hebrews,

or, less correctly, as the Epistle of

the

apostle to the Hebrews, bears in

oldest

MSS

no other title than the words

W H , etc.], ‘ T o the Hebrews.’ This brief heading

embraces the whole information

as to the origin of the

epistle

on which Christian tradition is unanimous.

Everything else-the authorship, the address, the date

-was unknown or disputed in the early church, and

continues

to form matter of dispute

the present day.

As far back

as

the latter part of the second century, how-

ever, the destination

of the epistle

‘

to the Hebrews’

[though it cannot be proved for Rome at

so early a

was acknowledged alike in Alexandria, where it

was ascribed to Paul, and in Carthage, where it passed

by the name of Barnabas

and there is no indication

that it ever circulated under another title. At the same

See B. Rash

26

Del. on Ps.

and

The connecting link between the Masoretes and the gram-

marians

is

ben Mosheh hen Asher, whose

has been published by Baer and

’79).

3

See his

Two

edited by Nutt, London,

4

His Book

Arabic, edited by Neubauer, Oxford.,

HEBREWS,

EPISTLE

time we must not suppose,

as

has sometimes bcen

supposed, that the anthor prefixed these words to his

original manuscript.

T h e title says no more than that

the readers addressed were Christians of Jewish extrac-

tion, and this would be no sufficient-address for a n

epistolary writing

directed to a definite circle of

readers,

local church or group of churches to whose

history repeated reference is made, and with which the

author had personal relations

(13

23).

The original

address, which according to custom must have stood

on

t h e outside of the folded letter, was probably never

copied, and the universal prevalence of the present title,

which tells no more than can be gathered

(as

a

hypo-

thesis) from the epistle itself, seems to indicate that

when the book first passed from local into general

circulation its history had already been forgotten.

With this it agrees that the early Roman church,--

where the epistle was known about the end of the first

century, and where indeed the first

traces of the use of it occur (Clement,

and

nothing

to contribute to the auestion of author-

ship and origin except the negative opinion that the

book is not by Paul.

Caius and the Muratorian fragment reckon but thirteen

epistles of Paul ; Hippolytus (like his master

of Lyons)

knew our book and declared that it was not Pauline.

T h e earliest positive traditions

of authorship to which

we can point belong t o Africa and Egypt, where,

as we

have already seen, divergent views were

by the

end of the second century.

I.

T h e African tradition

preserved by

(De

but certainly

not invented by him, ascribes the epistle t o Barnabas.

Direct apostolic authority is not therefore claimed for it ; but

it

has the weight due

to

one who learned from and taught with

the apostles,’ and we are told that it had more currency among;

the churches than ‘that apocryphal shepherd of the adulterers

(the Shepherd of Hermas). This tradition of the African church

holds a singularly isolated position. Later writers appear

to

know it

from Tertullian,

it

soon

became obsolete,

to

be

revived for

a

moment after the Reformation by the Scottish

theologian Cameron, and then again in our own century

the

German critics, among whom a t present it is the favourite view

[see below,

4,

2.

Very different

is

the history

of

the Egyptian

tradition, which can be traced back as far as

a teacher

of the Alexandrian Clement, presumably

(Euseb.

This

‘

blessed’presbyter,’ as Clement calls him sought to

explain why Paul did

not

name himself as usual

the head of

the epistle, and found the reason in the modesty

of

the author,

who in addressing the Hebrews was going beyond his

apostle to the Gentiles.’ Clement himself takes it for

granted that an epistle to the Hebrews must have been written

Hebrew, and supposes that Luke translated it for the Greeks.

Thus far there is no sign that the Pauline authorship

was ever questioned in Alexandria, and from the time

of

Origen the opinion that Paul wrote the epistle became

more and more prevalent in the East.

rests

on

the same tradition, which he refers

to

‘the

ancient men ;

but he knows that the tradition is not common

to

all

churches. H e feels that the language is

though

the admirable thoughts are

not

second

to

those of the unques-

tioned apostolic writings. Thus he is led to the view that the

ideas were orally set forth by Paul, but that the language,

arrangement,

some features of the exposition are the work

of a disciple. According to some, this disciple was Clement of

Rome

;

others [Clement and his school] named

; but

truth says Origen is known

to

God alone (Eus.

625

cp

338).

I t is

surprising’that

of the traditio; had less

influence than the broad fact that Origen accepted the book as

of Pauline authority.

I n the West this view was still far from established in

the fourth century but it gained ground steadily, and,

indeed, the necessity for revising the received view could

not be qnestioned when men began to look a t the facts

of the case.

Even those who, like Jerome and Augustine, knew the

of

tradition were unwilling

to

press an opposite view

;

and

in the fifth

the Paulineauthorship wasacceptedat Rome,

and practically throughout Christendom,

not

to be again disputed

till the revival of letters and the rise of a more critical spirit.

I t was Erasmus who indicated the imminent change

of

opinion.

HEBREWS, EPISTLE

Erasmus brings out with great force the vacillation

of

tradition

and the dissimilarity of the epistle from

style and thoughts

of

Paul in his concluding annotation

on

the hook. He ventures

the conjecture, based

on

a passage of his favourite Jerome, that

Clement of Rome was the real author. Luther (who suggests

Apollos) and Calvin (who thinks of Luke or Clement) followed

with the decisive argument that Paul who lays such stress

on

the fact that his gospel was

not

to

by man but was

by direct revelation (Gal.

1

could

not

have written Heb.

where the author classes himself among those who received

the message of salvation from the personal disciples of the Lord

on the evidence of the miracles which confirmed their word.

T h e force of tradition seemed already broken

but

the wave of reaction which

so

soon overwhelmed the

freer tendencies of the first reformers, brought back the

old view.

Protestant orthodoxy again accepted Paul as

the author, and dissentient voices were seldom heard till

the revival of free biblical

in the eighteenth

century.

As

criticism strengthened its arguments, theo-

logians began to learn that the denial of tradition in-

volves no danger to faith, and at the present moment,

scarcely any sound scholar will be found to accept Paul

as

the direct author of the epistle, though such a

modified view

as

was suggested by Origen still claims

adherents among the lovers

of

compromise with

tradition.

T h e arguments against the Alexandrian tradition are

in fact conclusive.

It

is probably unfair to hamper that tradition with Clement’s

notion that the book is a translation from the Hebrew. This

monstroushypothesisreceived

its

3.

Not

Paul.

absurdum

the attempt of J. H. R.

Biesenthal

to

reconstruct the Hebrew text

( D a s

des

an

die

etc.,

78).

Just as little, however,

can

Greek be from Paul’s pen.

T h e

character of the style, alike in the

words used and in the structure of the sentences, strikes

every scholar

as

it struck Origen and Erasmus.

The theological ideas

are cast in

a

different mould

;

and the leading conception of the

high-priesthood of Christ which is

no

mere occasional

but a central point in

author’s conception of

finds

its

nearest analogy

not

in the Pauline epistles but in John

17

The Old Testament is cited after the Alexandrian transla-

tion more exactly and exclusively than is the custom of

Paul,

and that even where the Hebrew original is divergent. Nor is

this an accidental circumstance.

There

every appearance

that the author was

a

Hellenist whose learning did not embrace

a

knowledge of the Hebrew text, and who derived his metaphysic

and allegorical method from the Alexandrian rather than the

Palestinian

T h e force of these arguments can be brought

out

only

by the accumulation of a multitude of details too tedious

for this place but the evidence from the few personal

indications contained in the epistle

is

easily grasped and

not less powerful.

The type of thought is quite unique.

The

from

which appeared decisive

to

Luther

and Calvin, has been referred

to

already

Again, we read

in

that

writer is absent from

church which he

addresses but hopes

to

be speedily restored to them.

This

is

not to be understood as implying that the epistle

was written in prison, for

1323

shows that the author is master

of

his

own

The plain sense is that the author’s home is with the

church addressed, but that he is at present absent, and

begs their prayers for

a

speedy return.

T h e external

authority of the Alexandrian tradition can have no

weight against such difficulties.

If that tradition was

original and continuous, the long ignorance of the

church and the opposite tradition of Africa are

inexplicable.

No

tradition, however, was more likely

to arise in circles where the epistle was valued and its

forgotten.

In spite

of

its divergences from the

For

the

Alexandrian elements in the

consult

list

of

n.

‘75).

A

large mass of valuable material is

J. B. Carpzov’s

Sacra

in

a d

ex

A

(Helmstadt

[Von

Soden

(Handcomm.

4)

gives addi-

tional

of

dependence

on

Philo, and proves the literary

influence also of the Wisdom of Solomon; cp Plumptre in

Expositor,

ser.

i.

I n

10 34

the true reading is not of me in my bonds,’ but

them that were in bonds’

The

false reading, which was that of Clement of Alexandria, is

probably connected with the tradition that Paul was the author.

HEBREWS, EPISTLE

standard of Pauline authorship, the book has manifest

Pauline affinities,

and

can hardly have originated beyond

the

circle, to which it is referred, not only

by

the author's friendship with Timothy

but also

by

many unquestionable echoes of the Pauline theology,

and even

by

distinct allusions to passages in Paul's

epistles.

I n a n uncritical age these features might easily suggest

Paul

as

the author of

a book which [doubtless, because

its Pauline origin was universally believed in Alexandria]

took its place in

MSS

immediately after the recognised

epistles of that apostle, and contained nothing in its

title to distinguish it from the preceding books with

similar headings, ' T o the Romans,'

' T o

the Cor-

inthians,' and the

A similar history,

as Zahn has

pointed out, attaches to the so-called second epistle of

Clement to the Corinthians.

When we see that the tradition which names Paul

as

author does not

an

authentic historical basis. we

are necessarily carried o n

to

deny historical

authority t o the subsidiary conjectures or

traditions which speak of Luke a n d

Clement of Rome.

The history of the Alexandrian tradition shows that these

names were brought in merely to lessen the

attaching

to

the view that Paul wrote

book exactly

as

we have it.

T h e name of Lnke seems to be

a

conjecture of the

Alexandrian Clement, for it

has n o place in the tradition

received from his master.

Some had

mentioned one and some the other God alone knows the truth.

We

no

to think more'highly of these suggestions

than Origen did. Indeed no Protestant scholar now proposes

the name of

extant epistle to the Corinthians

shows his familiarity

the epistle

to

the Hebrews, and at the

same time excludes the idea that he composed it. The name of

Luke has still partisans-Delitzsch carefully collected linguistic

between our epistle and

Lucan writings

57

; ET,

'68-'70).

The arguments of Delitzsch are generally met

with the objection that

author must have been a born

Jew,

which from his standpoint and culture is in the highest degree

probable, though not perhaps absolutely certain. In any case

we cannot suppose that Luke wrote the epistle on Paul's com-

mission, or that the work is substantially the apostle's for such

a

theory takes

no

account of the strongly-marked individuality of

the

in thought and method as well as expression.

T h e theory that Luke

was

the independent author

of

the epistle (Grotius a n d others) has

n o right

to

appeal

t o 'antiquity, and

stand entirely on the very

inadequate grounds of internal probability afforded

by

language a n d style.

If Alexandria fail us, can we suppose that Africa

preserved the original tradition? This is

a difficult

question.

T h e intrinsic objections to authorship

by

Barnabas

are not important.

The so-called Epistle of

was not written by our

author ;

but then it is admittedly not hy Barnahas. The superior

elegance of the style of our epistle

as

compared with that of

Paul is not inconsistent with Acts

14

nor is there, as we shall

see presently, any real force in the once favourite objection that

the ordinances of the temple are described with less accuracy

than might be looked for in Barnabas, a Levite and one who had

resided in Jerusalem (see

On the other hand, it is hard

to believe that the

account of the authorship of our book

was preserved only in Africa, and in a tradition

so

isolated that

Tertullian seems

to

he its only independent witness. How could

Africa know this thing and Rome be ignorant? Zahn, who is

the 'latest exponent of the Barnabas hypothesis, argues that in

the West, where the so-called epistle of Barnabas was long

unknown, there was nothing to suggest

idea of Barnabas

as

an author; that the true tradition might perish the more readily

attaches no importance to either name.

An unambiguous proof that our author had read'the epistle

to

the Romans seems

to

lie in

This is the one OT

citation of the epistle which does not follow the LXX

32

35)

but

it

is word for word from Rom.

[The proof is

however, conclusive. Dependence on Romans cannot be shown

elsewhere in the epistle and this particular citation is found

exactly as it is in

Further signs of dependence on

Romans and Corinthians (which require sifting) have been

collected by Holtzmann

see also Hilgenfeld's

The order of EV

is that of the Latin Church, the oldest Greek codices placing it

before

pastoral epistles. The Latin order, which expresses

the original uncertainty of

Pauline tradition, was formerly

current even in the East.

1993

The place of the epistle in MSS varies.

HEBREWS,

EPISTLE

in other parts

of

the church after the name of Barnabas

been falsely attached

to

another epistle dealing with the typology

of.

ceremonial law and finally that the false epistle

of

Barnabas which was first

so

in Alexandria may there

have

off

the true title of the epistle to the Hebrews after

the latter

was

ascribed

to

Paul. That is

not

plausible, and it is

more likely that an epistle which calls itself

(Heb.

was ascribed to the

(Acts

436)

in

the same way as

Ps. 127

was ascribed

to

'the beloved

of the Lord'

(z

Sam.

12243)

from the allusion 'in

than

that this coincidence of

affords a confirmation of the

Barnabas hypothesis.

I n short, the whole tradition

as

to the epistle is too

uncertain to offer much support to any theory of author-

ship, and if the name of Barnabas is to be accepted,

it

must stand

mainly

o n internal evidence,

See further

below,

Being thus thrown back on what the

epistle itself can tell us, we must look a t

the first readers, with whom,

as we have

already seen, the author stood in very

close relations.

Until comparatively recently there

was

a

general

agreement among scholars that the church addressed

was composed of Hebrews, or Christians of Jewish

birth.

We

are not, however, entitled to take this

simply on the authority of the title, which is hardly

more than

a

reflection of the impression produced

on an

early copyist-an impression the justice

of

which is now seen to b e more than doubtful.

I t is

plain, indeed, that the writer

is

a t one with his readers

in approaching all Christian truth through the OT.

He and they alike are accustomed to

Christianity a s a

continuous development

of

Judaism, in which the benefits of

Christ's death

to the ancient people

of

God and supply

the shortcomings of the old dispensation (49

9

13

With

all the weight that is laid on the superiority of Christianity, the

religion

of

finality, over Mosaism, the dispensation which

brought nothing to its goal, the sphere

of

the two dispensations

is throughout treated as identical.

This, however,

is

n o less the position

of

Paul

and

of

Acts.

Not only Jews by birth, but Gentiles

also, are

reckoned

as

belonging to the people of God, children of

Abraham, heirs of the promise,

as

soon

as

they

believers in Christ.

The OT is the book

of

this the true

of

God

: it is the

original record of the promises which

been fulfilled

to

it

in

Christ and

institutions of the Old Covenant equally with

the histories of the ancient people are types for Christian times.

T h e difference between Paul a n d the author

of our

epistle is only one of temperament.

With respect to

the two stages, Paul brings into bolder prominence the

differences, the incompatibilities, which render compro-

mise impossible, a n d compel

a

man

either to abide in

the one or to make the decisive forward step to the

other.

Our author,

on

the other hand, lays stress

rather on their common features, with the object

of

pointing out the advance they show from the imperfect

to the perfect.

Moreover,

as

a n Alexandrian,

he

is

bolder in the freedom, rendered possible

by

the

allegorising method, with which he adapts

OT

pre-

scriptions to N T times.

In

the same degree in which

our

author comes behind

Paul

in originality a n d

force of character does he rely in

a more academic a n d

thoroughgoing manner on the absolute a n d supreme

authority of the

O T

for Gentile Christians also.

T h e whole tendency of the epistle, however, is against

the theory that it was originally addressed

to

Jewish

Christians.

T h a t the readers were in

no danger

of relapsing into participation

in the Jewish sacrifices, that the tenor

of the epistle in like manner forbids the assumption

that they had consistently followed the ceremonial

observances that had their centre in the temple ritual,

has been shown conclusively

by

the original author

of

the present article.

Nowhere is any warning raised

against taking part in the worship

of

the temple, against

the retention of circumcision, or against separation from

of the present article have undergone very consider-

able revision the view that the epistle was originally addressed

to

Jewish

being here abandoned.]

REBREWS, EPISTLE

those who are not Jews.

Nor could any such warning

b e necessary in the case

of readers who

so

plainly were

a t one with the author of the epistle with regard to the

Alexandrian allegorizing methods.

Robertson Smith

concedes that at least their ritualism seems to have been

rather theoretical than practical, and goes

to say-and

with truth- that among men of this type (of the Hellen-

istic Diaspora and

of such

a

habit

of thought as enabled

them readily to sympathise with the typological method

of our author) there was no great danger of a relapse

into practical ceremonialism. They would rather be

akin to the school of Judaism characterised by Philo

(De

16,

ed. Mangey,

who neglected

the observance of the ceremonial laws because they took

them as symbols of ideal things.

Over and above all this, however, we learn quite

clearly from the admonitions of the letter itself, what

were the dangers that threatened its readers.

Its theoretical expositions constantly end in exhortations to

hold fast to the end their confession, their confidence, the firm

convictions with which they had begun their Christian life, to

draw near with boldness to the throne of grace in full assurance

of

faith, to serve God acceptably, earnestly

to

seek

an

entrance

into rest and

so

forth. On the usual assumption that the

readers

Jewish Christians who were in danger of going

back to Judaism, these are precisely the objects which they

would have hoped to realise

taking this step. The exhorta-

tions expressed in such terms

as

these would not have been

a p

riate to their case.

does this hold good of the negative precepts of the

epistle.

Assnmin that they had thoughts of returning to

how

they have felt themselves touched by

a

warning not

to

depart from the living God

(3

not

to

reject

‘

him that is from heaven

12

not to despise

so

great salvation

3),

not to sin willingly

(10 26)

not to tread

under foot the Son of God, not to reckon

of

the

covenant an unholy thing, not to do despite to the spirit of grace

How could they be expostulated with as if their pro-

posed action proceeded from

(3

4

11

), or

from an evil

heart of unbelief

(3

or

as if they were being hardened in the

deceitfulness of sin

(3

or in danger from regard to outward

show,

and

from

How could

O T (Dt.

29

figure of the root of bitterness

or,

still more,

that of Esau (12

appeal to them?

Such expressions as these can refer only t o an open

apostasy from Christianity out of very unworthy motives,

and if applied to a proposed return t o Judaism on re-

ligious motives working

upon

a pious but unenlightened

conscience would be harsh, unreasonable, and tactless.

The reproaches would seem

so

unjust to the person

addressed as to lose all their force.

Further, the remonstrance in

would even be

absolutely meaningless, for the points there named are

for

the most part positions that are common to Jews

and Christians, and none of them touches upon what

is

distinctive of Christianity a s contrasted with Judaism.

Nowhere does

our

author speak

a

word of warning against

participation in heathen sacrifices. As causes of the apostasy that

i s

feared, no prominence is given nor

is any mention made

of any inclination to legalism. Indeed it was

exact opposite

of this that was the temptation of the Israelites in the wilderness

with whom the readers are compared

(3

13).

Apart from the

references to moral infirmity

12 3

the only positive fault

that theauthor mentionsin connection with the lesson drawn from

his doctrine to use with diligence the specifically Christian way

of

access to God

(10

is

a

disposition to neglect the privileges

of social worship

(1025).

This again is plainly connected, not

with an inclination to return

the

but with

a

re-

laxation of the zeal and patience of the

of

their Chris-

tian profession

(6

+$

I

$),

associated with

a

less firm

hold than they once had of the essentials of Christian faith,

a

less clear vision of the heavenly hope of their calling

(3

4

5

T h e writer fears lest his readers fall away not merely

from the higher standpoint of Christianity into

practices, but from all faith in God and judgment and

immortality

What, in fact, threatens to alienate the readers

of

t h e epistle from Christianity is the character

of

the out-

ward circumstances

which they are placed.

In this

their case resembles that of Israel in the wilderness.

This comes clearly into view in the second part of the

epistle, in which the theological arguments are practi-

cally applied.

At the very outset of this second part

we learn that

the readers have been passing through sore persecutions. How

HEBREWS,

EPISTLE

long these have lasted is not said hut the present attitude of

the readers is different from what it had been.

they had

kept steadfast

;

hut now their endurance threatens to give way;

they are

danger of casting away their confidence. In chap.

11

they are pointed to the examples of a faith that triumphed over

every obstacle, and exhorted to

a

similar conflict, even

blood,

as Jesus has gone before

as the beginner

and ender of faith

(12

The writer grants that their cir-

cumstances are such as niay well make hands listless and knees

feeble and souls weary and faint

3

6

but

proper

course is to take all this as

to remember the

persecuted and imprisoned with true fellow-feeling

(13 3), to

find

strength in recalling the memory

of

their departed teachers

(13

to go forth

in the allegorising

style of

epistle, to quit the world (see below)-with

Jesus,

bearing his reproach

(13 13).

Now it is quite true that troubles

of

the kind indicated

might very well tend to tempt back to Judaism those

who, originally Jews, had experienced on account

of

their Christianity persecution that contrasted with the

religious freedom they had enjoyed as Jews.

In that

case, however, their Jewish character would certainly

have appeared otherwise also -which,

we have seen,

is not the case-or the theoretical ground-work on

which the hortatory part proceeds must have aimed a t

depreciating the Jewish religion and bringing it into

irreconcilable antithesis to the Christian.

This is

certainly not the tenor of chaps.

1-10.

On the contrary,

the close connection of Christianity with the old

Covenant, and the high significance of the latter, is

elaborated in every way; it is

so

at the very outset

(1

I

) ,

and again in 22

and elsewhere.

The

in chaps.

7-10

is

not intended

to

prove the abro-

gation

it assumes it and proceeds

it

as

an

acknowledged fact: The elaborate description of the OT sacri-

ficial system in

9

10

is

at

no

point accompanied

with

a

warning against participation in it. The author draws

conclusions

as

to

the glory of the new covenant from the signi-

ficant ordinances of the old, which are regarded as shadows of

the other ; but his argumentation has not for its aim the desire

to detach the readers from Judaism any more than has Philo’s

of proving from the O T the truth of his philosophy and

ethics, which he regards as constituting its kernel.

T h e author knows no better way to prove the truth

of

Christianity than simply by showing that it

is

in

every respect the complete fulfilment of all that was

prefigured and promised in the

OT,

the record of the

pre-Christian revelation of God.

This manner of using the

OT

in argument must not,

however, be held to imply on the part

of

the readers

a

previous acquaintance with the

OT,

such as would

have been possible only in the case of Jews.

A

similar

line of argument is addressed in Gal.

3f:

Cor.

3

to the Pauline, and admittedly Gentile, Christian com-

munities of Galatia and Corinth

Philo also, addressing

pagan readers, takes all his proofs from the

OT.

T h e view that those originally addressed in the epistle

were Jewish Christians, although supported by the

ancient tradition implied in its superscription, must thus

be given

up.

With this, the difficult problem of finding

a local habitation for such

a

community disappears.

T h e following are the hypotheses as to the place

of

abode of the readers of the epistle that have been

offered.

I

.

T o some writers ‘the

emphatic all in

13

2 4 ,

the admonitions

have suggested the possibility

that the Hebrews addressed were but part, a somewhat

discontented part, of a larger community in which Gentile

elements had a considerable place.

This appears

a

strained conclusion (Phil.

I

Thes.

distinctly

contrary to the general tone of the epistle, which moves

altogether outside of the antithesis between Jewish and

Gentile Christianity.

W e must think not

of

a party but

of a church, apd such a church can be sought only in

Palestine, or in one of the great centres of the Jewish

dispersion.

T h a t the epistle was addressed to Palestine, or more

specifically to Jerusalem, has been a prevalent opinion

from the time of Clement

of

Alexandria, mainly because

it was assumed that the word Hebrews must naturally

mean Jews whose mother-tongue was Aramaic.

The

HEBREWS, EPISTLE

term has this restricted sense, however, only when

put in contrast to Hellenists.

I n itself, according to

ordinary usage, it simply denotes Jews by race, and in

Christian writings especially Jewish Christians.

There are several things in the epistle that seem to

exclude Palestine, and

all Jerusalem.

The Hel-

lenistic culture of the writer and the language in which

he writes furnish one argument.

Then the most

marked proof of Christian love and zeal in the church

addressed was that they had ever been assiduous in

ministering to the saints

This expression may

conceivably have

a

general sense

(

I

Cor.

16

?) but it

is far more likely that it has the specific

which

it generally bears in the

the collection of alms

for the church, in Jerusalem.

At

any rate

it

was

clearly

understood in the first age of Chris-

tianity

that

the

church took alms and did not give them

receiving

in

temporal things

an

acknowledgment for the

things they had

In fact the great

weight laid

the epistles

of

Paul on this-the

manifesta-

tion of

the

catholicity of the church then possible (Gal.

2

alone

explains

the emphasis with which

our

author cites this

one

proof

of Christian feeling.

Again, the expressions in

already referred t o imply

that the readers

not include in their number direct

disciples of Jesus, but had been brought to Christ by

the words and miracles of apostolic missionaries now

dead

( 1 3 7 ) .

This conversion, as it appears from

1032,

was a thing of pre-

cise date immediately followed by persecution (note the

Accordingly we cannot suppose those

addressed

to

represent a

second

generation

in the

Palestinian

Church we

are

referred to some part

of

Diaspora.

Against these difficulties-

which have led some of

the defenders of the Palestinian address, a s Grimm

(who, in Hilgenfeld‘s

proposes Jamnia)

and

(New

Testament Commentary

English

Readers,

vol.

to give up Jerusalem altogether,

whilst others, as Riehm, suppose that the Hellenists

of

Jerusalem (Acts

61)

a r e primarily addressed [and

B.

Weiss thinks of the epistle as having been

a circular to

Palestine generally]-it is commonly urged that the

readers are exposed to peculiar danger from the per-

secutions and solicitations of unbelieving Jews, that

they a r e in danger

of

relapsing into participation in the

Jewish sacrifices, or even that they appear to have never

ceased to follow the ceremonial observances that had

their centre in the temple ritual.

The capital argument for this is drawn from

13

where the

exhortation

to

go forth to Jesus without the camp

as

an

injunction

to

renounce fellowship with the synagogue and with

the ceremonies and ritual of Judaism. This exegesis however

rests on

a

false view of the context which does

and expresses by

a

figure

that

Christians

(as

the priests

of

the new covenant) have

no

temporal advantage to expect

their participation

in

the sacrifice of Christ, but must he content

to share his reproach, renouncing this earthly country for the

heavenly kingdom (cp

11

25-27

with

13

14

Phil.

3

Altogether, this view of the situation of the first