ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Pain following stroke: A prospective study

A.P. Hansen

1

, N.S. Marcussen

1

, H. Klit

1

, G. Andersen

2

, N.B. Finnerup

1

, T.S. Jensen

1,2

1 Danish Pain Research Center, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark

2 Department of Neurology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark

Correspondence

Anne Petrea Hansen

E-mail: anne.hansen@ki.au.dk

Funding sources

The study has been funded by the Danish

Research Council, the Elsass Foundation and

the Velux Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Accepted for publication

26 January 2012

doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00123.x

Abstract

Background: Post-stroke pain is common and affects the quality of life

of stroke survivors, but the incidence and severity of headache, shoulder

pain, other joint pain and central post-stroke pain following stroke still

remain unclear. The aim of this prospective study was to determine the

incidence and intensity of these different types of post-stroke pain.

Methods: A total of 299 consecutive stroke patients, admitted to the

Department of Neurology at Aarhus University Hospital, underwent a

structured interview and a short sensory examination within 4 days of

admission. Follow-up was conducted by phone 3 and 6 months after

stroke onset, with 275 patients completing the whole study. Pain with

onset in relation to stroke onset or following stroke was defined as ‘newly

developed pain’.

Results: At the 6-month follow-up, newly developed pain was reported

by 45.8% of the patients; headache by 13.1%, shoulder pain by 16.4%,

other joint pain by 11.7%, other pain by 20.0% and evoked pain by light

touch or thermal stimuli by 8.0%. More than one pain type was

reported by 36.5% of the patients with newly developed pain. According

to pre-defined criteria, 10.5% of the patients were classified as having

possible central post-stroke pain. There was a moderate to severe impact

on daily life in 33.6% of the patients with newly developed pain.

Conclusions: Pain following stroke is common, with almost half of the

patients reporting newly developed pain 6 months after stroke.

1. Background

Pain is an often overlooked consequence of stroke

although it has been reported in 15–49% of patients

within the first 2 years after stroke (Widar et al., 2002,

2004; Kong et al., 2004; Lundstrom et al., 2009; Naess

et al., 2010). The most common types of post-stroke

pain are headache, shoulder pain and central post-

stroke pain (CPSP). Headache in the acute phase of

stroke has been reported in 27–31% of patients,

depending on the type of stroke (Vestergaard et al.,

1993; Tentschert et al., 2005; Verdelho et al., 2008),

whereas headache with late onset has shown preva-

lence rates of 3.5–11% within the first 2 years (Ferro

et al., 1998; Widar et al., 2002; Jonsson et al., 2006).

Shoulder pain has been reported in 15–40% of patients

within 6 months after stroke (Langhorne et al., 2000;

Gamble et al., 2002; Ratnasabapathy et al., 2003;

Lindgren et al., 2007), and CPSP is seen in 5–11% of

stroke patients (Andersen et al., 1995; Bowsher, 2001;

Weimar et al., 2002; Widar et al., 2002).

The large majority of post-stroke pain studies are

retrospective with different follow-up periods. Few

studies have distinguished between the stroke-affected

side and the unaffected side of the body and only few

studies have tried to differentiate between pre-existing

pain condition and post-stroke pain. Since most

studies focus on only one type of pain, the incidence of

1128

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

the various types of post-stroke pain in the individual

patient is not known. These issues can only be clarified

in a prospective study.

The aim of this prospective study was to examine

the incidence of headache, shoulder pain, other joint

pain, evoked pain and possible CPSP after stroke in

consecutively admitted patients with a 6-month

follow-up and to describe each pain type.

2. Methods

2.1 Patients

All consecutively admitted stroke patients at the

Stroke Unit at the Department of Neurology, Aarhus

University Hospital, between 1 February and 30 Sep-

tember 2007, and 1 February and 31 July 2008, were

considered for inclusion in the study. Inclusion criteria

were a stroke diagnosis (ICD-10 codes: I61, I63, I649,

I676, I677), age over 18 years and informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of transitory cere-

bral ischaemic attack (G459) or subarachnoid haem-

orrhage (I609), communication problems (e.g. severe

aphasia or dysarthria), severe dementia, somnolence,

lack of consent to participate or lack of Danish lan-

guage skills.

2.2 Primary interview and sensory examination

Eligible patients were included within the first 4 days

of admission. Patients underwent a structured inter-

view. Patients were asked about pain prior to stroke

defined as any persistent or recurring pain within the

last 3 months including description of location, fre-

quency and pain intensity using the numeric rating

scale (NRS 0–10). Then patients were asked about

headache, shoulder pain, other joint pain, touch- or

cold-evoked pain and other pain experienced in close

temporal relation to stroke onset. Information on loca-

tion, frequency, intensity and a description was

obtained for each pain type.

A brief standardized sensory examination was con-

ducted bilaterally on both sides of the body on the

forearm, thenar, cheek, anterior part of the lower leg,

and dorsum of the foot using a brush (Somedic, Hörby,

Sweden), a cotton ball, a thermo roller (20 °C,

Somedic) and No. 5.88 g von Frey monofilament

(Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). A full neurological

examination was not conducted in relation to the

study. All interviews and examinations were con-

ducted by one of two investigators (N.S.M. and A.P.H.).

All accessible hospital records including the Scandi-

navian Stroke Scale (SSS) score (Lindenstrøm et al.,

1991), imaging results and information on risk factors

were obtained.

2.3 Follow-up interviews

A structured follow-up telephone interview was con-

ducted 3 and 6 months after stroke onset. Patients were

asked if they had experienced any pain during the

previous week. Pain was divided into headache, shoul-

der pain, other joint pain, other pain and pain evoked

by touch or cold/warm stimuli. Dysesthesia did not

qualify as pain. In order to distinguish between pre-

and post-stroke pain, patients were asked specifically

about the onset for each pain type, and this information

was compared with the information about pre-existing

pain given at the time of stroke onset. Pain with onset

in relation to stroke onset or after the stroke with

presence within the last week up to the follow-up was

defined as ‘newly developed pain’ and further classified

as being either in the stroke- or non-stroke-affected

side. Frequency, intensity (NRS 0–10) and description

of each pain type within the previous week were

recorded.

All patients with newly developed pain completed

the 7-item Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) question-

naire (Bouhassira et al., 2005, 2008) with a note on

the specific pain type which the item was related to.

Then they were asked about the impact of pain on

their daily life according to a 4-point scale ranging

from no impact to severe impact and their need for

pain medication within the last week prior to phone

call.

If the patients could not be reached by phone, a

questionnaire about newly developed pain was sent

out with a limited number of questions on newly

developed pain, location, intensity (NRS 0–10) and

description. A reminder was sent out once, and non-

responders were categorized as lost to follow-up.

What’s already known about this topic?

•

Post-stroke pain is common with an incidence of

15–49% within 2 years following stroke.

What does this study add?

•

Post-stroke pain incidence of 45.8% with a

moderate to severe impact on daily life in one of

three patients at a 6-month follow-up.

•

A distinction between different types of pain and

reports on more than one type of pain in 36.5%

at a 6-month follow-up.

A.P. Hansen et al.

Post-stroke pain

1129

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

A short questionnaire on development of pain fol-

lowing stroke was sent out once 6 months after stroke

to the excluded patients from 1 February to 30 Sep-

tember 2007.

2.4 Data analysis

Shoulder pain was defined as pain located to the

shoulder joint and nearby region. Other joint pain was

defined as pain in all other joints than the shoulders.

Reported pain that did not fit into any of the pain

groups was classified as other pain. Moderate to severe

pain was defined as pain with an intensity of 4 or

above on the NRS scale (NRS

ⱖ 4).

Data on all newly developed shoulder pain, other

joint pain, other pain and touch-, heat- or cold-evoked

pain on the stroke-affected side at the 6-month

follow-up were systematically reviewed by two of the

authors (H.K. and A.P.H.). Patients were identified as

having ‘possible CPSP’ [based on the proposed grading

system for CPSP (Klit et al., 2009)] if they fulfilled the

following three criteria: (1) development of pain with

onset at or after the stroke; (2) pain located on the

stroke-affected side of the body; and (3) no other

plausible cause of the pain, including pain isolated to

the shoulder joint and nearby region.

The stroke aetiology was categorized according to

the TOAST classification (TOAST) by two of the

authors (N.S.M. and A.P.H.) (Adams et al., 1993;

Kolominsky-Rabas et al., 2001). Stroke severity was

measured using the SSS (0–58) and a score below 45

was considered to be a severe stroke. The study was

approved by the local ethics committee (ID 20060116)

and the Danish Data Protection Agency (ID 2006-41-

6900) and was conducted in accordance with the Dec-

laration of Helsinki.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Data were analysed with STATA 9.1 software (Stata-

Corp LP, Collage Station, TX, USA). Pearson’s

c

2

test or

Fisher’s exact test was conducted for comparison of

categorical variables. T-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum

were applied for continuous variables. Probability

p-values

< 0.05 were considered significant. Missing

data were less than 3.0%.

3. Results

3.1 Study population

A total of 640 consecutive stroke patients were con-

sidered for inclusion at stroke onset. The stroke diag-

nosis was abandoned in 91 patients and 250 were

excluded, which left 299 patients eligible for inclusion

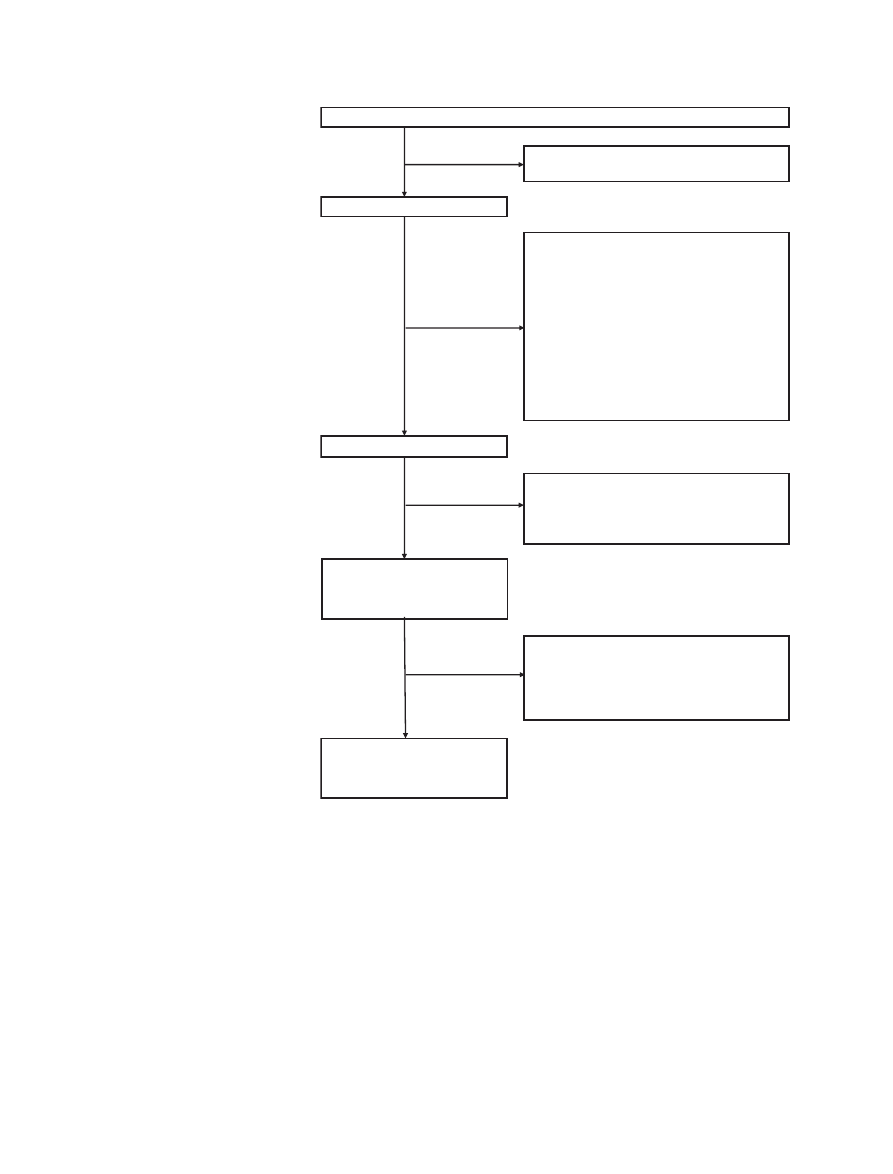

(Fig. 1).

Included

patients

were

younger

than

excluded patients [mean age 65.9 vs. 71.2 years

(p

< 0.0001)] with no significant difference in gender

(included 55.2% male vs. excluded 47.2% male,

p

= 0.062). The following results are based on the 275

patients who completed both the 3-and 6-month

follow-up; stroke characteristics and risk factors are

presented in Table 1. The median for time of follow-up

at 3 months was 95 days (10th and 90th percentiles:

90–113 days) and 189 days for the 6-month follow-up

(10th and 90th percentiles: 183–225 days).

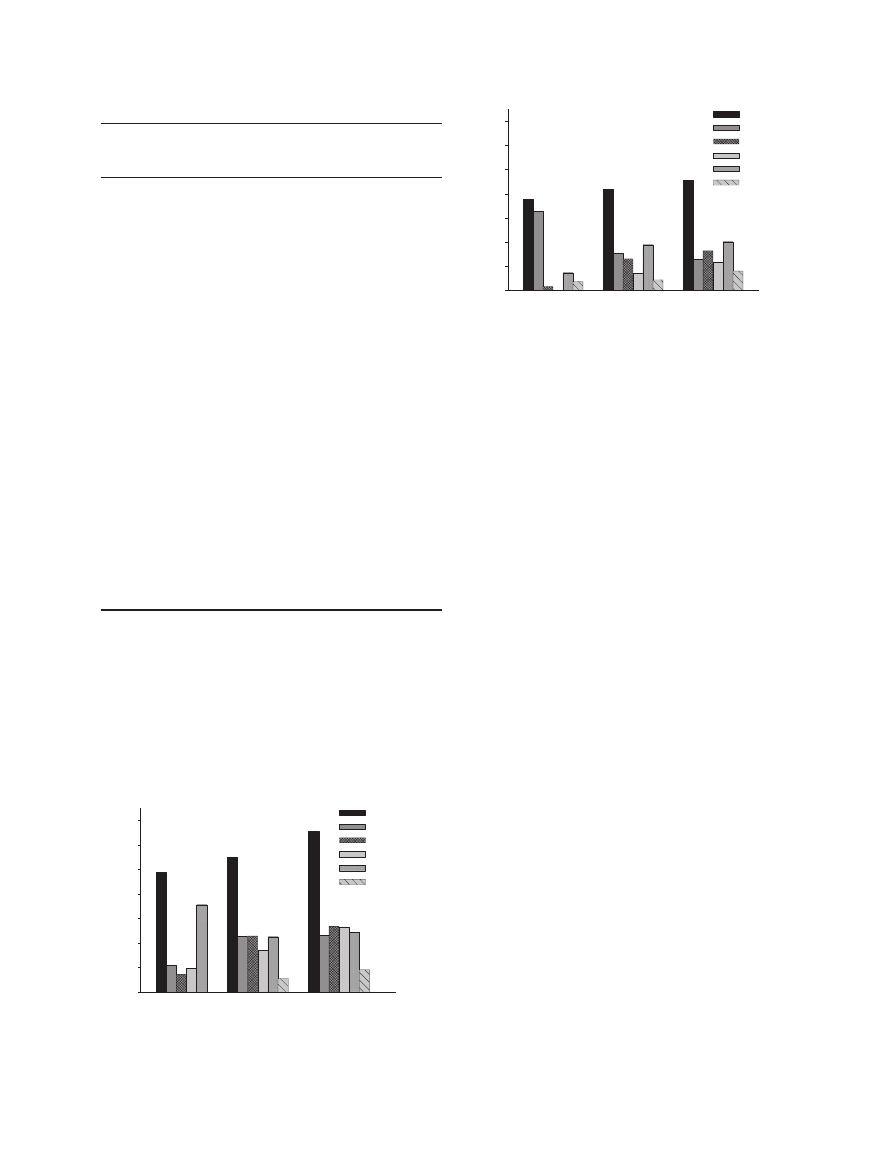

3.2 Pain

Pain within 3 months before the stroke was reported

by 49.1%. Total pain prevalence including all pain,

both pain with onset before stroke and newly devel-

oped pain was 55.3% at 3 months and 65.8% at 6

months (Fig. 2).

3.3 Newly developed pain

The incidence of newly developed pain was 37.8% at

stroke onset, 41.8% at the 3-month follow-up and

45.8% at the 6-month follow-up (Fig. 3). The impact

of newly developed pain on daily life for the patients

from phone interviews was moderate in 20.0% and

severe in 16.4% of patients at 3 months, while mode-

rate in 25.4% and severe in 8.2% at 6 months. A

total of 53.2% of the patients reported usage of pain

medication within the last week and 34.9% on the day

of the phone call at the 3-month follow-up while

52.9% reported usage within the last week and 31.9%

on the day of phone call at the 6-month follow-up.

More than one type of pain was reported by 32.2% of

patients with newly developed pain at 3 months and

by 36.5% at 6 months. At the 6-month follow-up, a

previous history of stroke and of acute myocardial

infarct at stroke onset was more frequent in the group

of patients with newly developed pain (p

= 0.040 and

0.045, respectively), and these patients were younger

than patients without newly developed pain (mean

age 63.3 vs. 67.5 years, p

= 0.008). There was no dif-

ference in sex, stroke type, SSS score, thrombolysis or

other stroke risk factors than above mentioned

between patients with or without newly developed

pain. Pain solely in the stroke-affected side was

reported by 18.9% and 22.6% of all patients at the 3-

and 6-month follow-up.

The questionnaire on newly developed pain sent

out to 145 of the excluded stroke patients from the

Post-stroke pain

A.P. Hansen et al.

1130

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

first inclusion period was returned by 42 patients.

Compared with the 45.8% of the included patients

reporting newly developed pain in this study, 35.7%

(15/42) of the excluded patients reported newly

developed pain 6 months after stroke (non-significant

difference p

= 0.220).

3.4 Headache

A total of 10.9% of the patients reported having

experienced persistent or recurrent headache 3

months prior to stroke. Headache with onset in close

temporal relation to stroke was experienced by

33.5%. The probability of reporting headache at

stroke onset if having experienced headache prior to

stroke was 20.0%, and only 6.5% if not having

experienced

headache

prior

to

stroke.

Patients

reporting headache at stroke onset were younger

(mean age 62.5 vs. 67.2 years, p

= 0.0061) and more

likely to be women (60% vs. 36.7%, p

< 0.0001) as

compared with patients without headache. Headache

at stroke onset was more common with large-artery

disease or cardio-embolism as compared with small

vessel occlusion (p

= 0.034). No relation between

Patients considered for inclusion between February 1, 2007 and July 31, 2008,

n=640

Eligible patients,

n= 549

Excluded patients,

n=250

- 55 due to communication problems (e.g.

aphasia)

- 56 due to weariness or loss of consciousness

- 16 due to lack of knowledge of the Danish

language

- 18 due to declination to participate

- 57 not possible to examine on 0-3 days of

admission

- 48 due to other causes (Alzheimer’s disease,

instrument problems, deceased before

examination, etc.)

Included at stroke onset,

n=299

Non-eligible patients,

n=91

- Due to desertion of stroke diagnosis

3-month follow-up,

n =282

-263 by phone interview

-19 by letter with questionnaire

Lost to follow-up at 3-month follow-up,

n =17

-7 deceased

-7 non-responders

-3 various reasons

Lost to follow-up at 6-month follow-up,

n =7

-3 deceased

-2 non-responders

-2 various reasons

6-month follow-up,

n =275

-260 by phone interview

-15 by letter with questionnaire

Figure 1 Flow chart of patients.

A.P. Hansen et al.

Post-stroke pain

1131

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

haemorrhage and headache at stroke onset was

found (p

= 0.66).

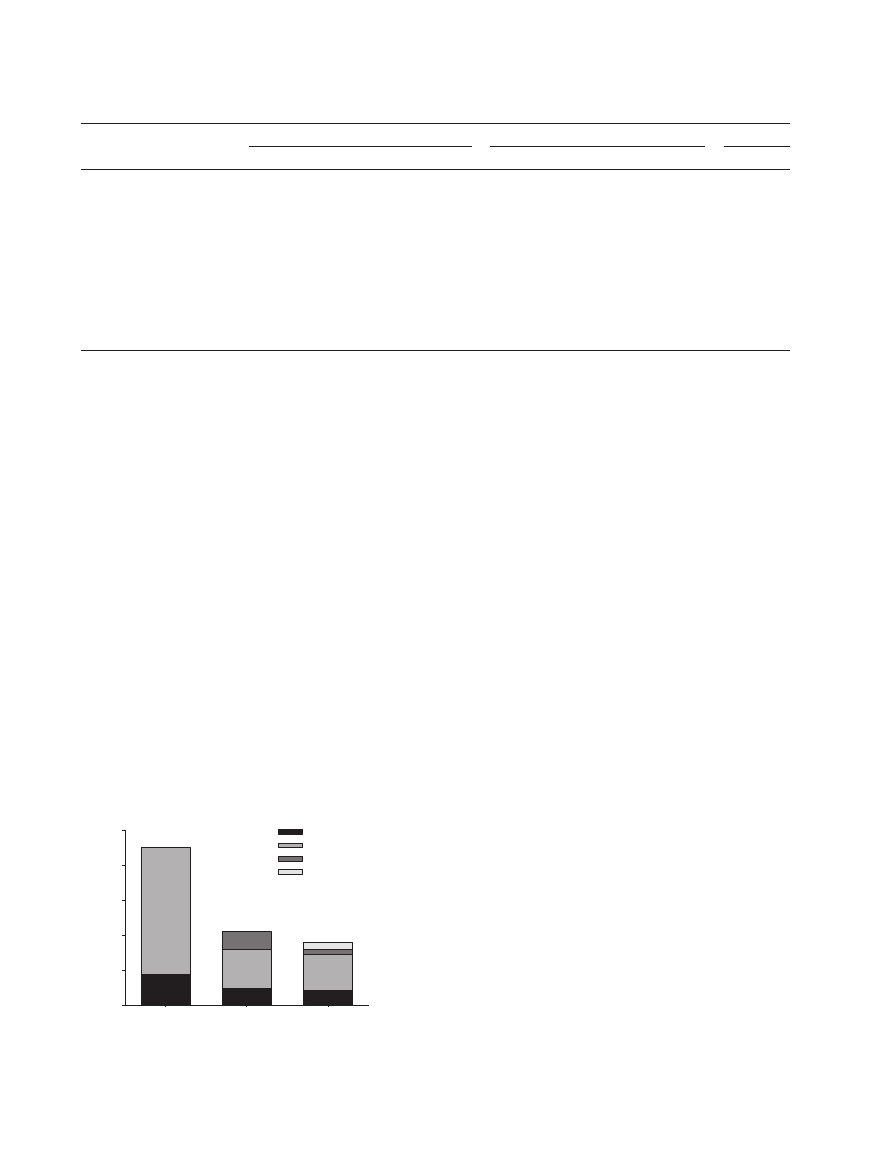

Headache was reported by 23.0% at 3 months and

23.4% at 6 months, and newly developed headache

was reported by 15.3% (NRS

ⱖ 4: 64.3%) and 13.1%

(NRS

ⱖ 4: 66.7%), respectively. See Table 2 for

further characteristics. The main descriptor of newly

developed headache was pressing, reported by 44.4%

at stroke onset, 43.0% at 3 months and 58.3% at 6

months. Movement did not induce or aggravate head-

ache in 73.8% and 66.7% of patients at the 3- and

6-month follow-up, respectively. Patients with newly

developed headache were younger than patients

without headache (p

< 0.05), but there was no gender

difference. The time of headache onset is depicted in

Fig. 4 and the likelihood of continued newly devel-

oped headache at 3-month follow-up was 69.0% and

70.3% at 6-month follow-up in patients with head-

ache at stroke onset. Accordingly, headache at stroke

onset was correlated to the presence of headache at 6

months (p

< 0.001).

3.5 Shoulder pain

The incidence of shoulder pain was 7.3% before

stroke, 22.9% at 3 months and 26.9% at 6 months

after stroke. Newly developed shoulder pain was

present in 1.5% at stroke onset, 13.1% at 3 months

and 16.4% at 6 months. Of those with shoulder pain

at 3-month follow-up, the probability of still reporting

this pain at 6-month follow-up was 48.9%. There was

no difference in age or gender between patients with

and without newly developed shoulder pain at follow-

up. Newly developed shoulder pain in the stroke-

affected side was reported by 10.2% at 3 months (NRS

ⱖ4: 71.4%) and 12.0% at 6 months (NRS ⱖ 4:

75.8%). The shoulder pain in the stroke-affected side

was aggravated or induced by movement in 71.4% at

the 3-month follow-up and in 71.9% at the 6-month

follow-up. Further characteristics are displayed in

Table 2. There was no association between stroke

severity (SSS

< 45) on admission and the development

of shoulder pain in the stroke-affected side at 3-month

Table 1 Stroke characteristics and risk factors at stroke onset.

Patients who

completed study

n

= 275

Sex, male, % (n/N)

55.6 (153/275)

Age, mean (range) years

65.6 (24–92)

Stroke type, % (n/N)

Infarct

90.5 (249/275)

Haemorrhage

9.5 (26/275)

Toast classification, % (n/N)

Large-artery atherosclerosis

12.9 (32/249)

Cardio-embolism

19.7 (49/249)

Small vessel occlusion/lacunar

38.1 (95/249)

Stroke of other determined etiology

4.8 (12/249)

Stroke of undetermined etiology

23.3 (58/249)

Not enough information to classify

1.2 (3/249)

SSS (n

= 205), median (range)

51 (2–58)

Thrombolysis, % (n/N)

17.6 (48/273)

Diabetes, % (n/N)

15.0 (34/227)

Hypertension, % (n/N)

64.2 (145/226)

Atrial fibrillation, % (n/N)

12.7 (25/197)

History of acute myocardial infarction, % (n/N)

8.0 (21/262)

Intermittent claudication, % (n/N)

6.6 (16/242)

Prior stroke, % (n/N)

17.9 (47/263)

Prior TIA (transient ischemic attack), % (n/N)

7.6 (19/249)

Alcohol,

>14 and 21 (women and men)

units/week, % (n/N)

10.6 (29/275)

Smoker, % (n/N)

Current

40.7 (112/275)

Prior

32.0 (88/275)

Never

27.3 (75/275)

SSS, Scandinavian Stroke Scale.

Percentage

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Total

Headache

Shoulder pain

Joint pain

Other pain

Evoked pain

Prior

3-month

6-month

Figure 2 Prevalence of pain 3 months before stroke not including evoked

pain and within the week leading up to the follow-up interviews.

Pe

rcentage

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Total

Headache

Shoulder pain

Joint pain

Other pain

Evoked pain

Onset

3-month

6-month

Figure 3 Incidence of newly developed pain at stroke onset and within

the week leading up to the follow-up interviews.

Post-stroke pain

A.P. Hansen et al.

1132

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

(p

= 0.348) and 6-month (p = 0.084) follow-up.

Detailed information on arm function was otherwise

not available. At the 6-month follow-up, 57.6% of the

patients described their shoulder pain on the stroke-

affected side as a deep pain while the pain was

described as both deep and superficial by 21.2%.

3.6 Other joint pain

Other joint pain was reported by 9.8% of the patients

prior to the stroke. None of the patients reported other

joint pain at stroke onset, while 17.1% had other joint

pain at 3 months and 26.6% at 6 months. A minority

of the patients reported newly developed other joint

pain: 7.4% at 3 months and 11.7% at 6 months. The

newly developed other joint pain at 6 months was

located on the hips (21.9%), knees (21.9%), finger

joints (15.6%), elbows (12.5%), feet (9.4%), pelvis

(6.3%), leg (6.3%), wrists (3.1%) and back (3.1%).

Only 1.8% had joint pain solely in the stroke-affected

side at 3-month follow-up (NRS

ⱖ 4: 100%) and

5.1% at 6-month (NRS

ⱖ 4: 85.7%) follow-up.

3.7 Other pain

Other pain was reported by 35.6% before stroke, 7.3%

at stroke onset, 22.2% at 3 months, and 24.0% at 6

months. Newly developed other pain was reported by

18.9% at 3 months and 20.0% at 6 months, and this

pain was on the stroke-affected side in 8.4%

(NRS

ⱖ 4: 87.0%) and 8.9% (NRS ⱖ 4: 75.0%),

respectively.

3.8 Evoked pain

Pain evoked by light touch or cold stimuli was

reported by 3.6% during the interview at stroke onset.

At the follow-up interviews, light touch, cold or warm

stimuli was reported by 5.5% and 9.1%, respectively,

at 3-month and 6-month follow-up. The evoked pain

was reported to be newly developed by 4.4% at

3-month follow-up (NRS

ⱖ 4: 91.0%) and 8.0% at

6-month follow-up (NRS

ⱖ 4: 72.7%). A total of 3.6%

reported evoked pain in the stroke-affected side at

the 3-month follow-up and 5.5% at the 6-month

follow-up.

Table 2 Overview of newly developed headache, shoulder pain on the stroke-affected side and possible CPSP.

Headache

Shoulder pain on the stroke-affected side

Possible CPSP

Onset

3-month

6-month

Onset

3-month

6-month

6-month

Total, n (%)

90 (33.5)

42 (15.3)

36 (13.1)

3 (1.1)

28 (10.2)

33 (12.0)

29 (10.6)

Male, n (%)

36 (40.0)

a

21 (50.0)

17 (48.6)

2 (66.7)

15 (53.6)

18 (54.6)

11 (37.9)

a

Age, mean (range)

62.5 (24–87)

b

61.4 (33–86)

b

60.7(30–86)

b

59.7 (49–67)

62.8 (33–86)

61.9 (33–80)

60.4 (39–76)

b

Frequency, n (%)

Constantly

57 (63.3)

4 (9.5)

4 (11.1)

0 (0.0)

5 (17.8)

6 (19.4)

6 (26.1)

c

Daily

–

13 (31.0)

9 (25.0)

–

14 (50.0)

16 (51.6)

16 (59.3)

c

ⱖTwice a week

–

12 (28.5)

12 (33.3)

–

8 (28.6)

8 (25.8)

4 (14.8.)

c

ⱕTwice a week

–

13 (31.0)

11 (30.6)

–

1 (3.6)

1 (3.2)

1 (3.7)

c

Pain intensity, NRS (0–10)

Median (range)

4 (0–9)

d

5 (1–8)

e

5 (1–10)

e

1 (0–3)

5 (2–10)

e

4.5 (1–9)

e

5 (1–10)

e

Movement induced/aggravation

–

11 (26.2)

12 (33.3)

–

20 (71.4)

23 (71.9)

–

CPSP, central post-stroke pain; NRS, numeric rating scale.

a

Significantly more women than men with pain (p

< 0.05).

b

Significantly younger patients with pain than patients without pain (p

< 0.05).

c

Only patients from phone interviews.

d

Intensity within the last 4 h prior to interview. Only including the 70 patients still having headache at interview time and including one patient who scored

a constant headache at 0 on the NRS.

e

Intensity within the last 1 week leading up to phone interview.

Stroke onset

3-month

6-month

Nu

mber

of p

atie

nts

0

20

40

60

80

100

Prior to stroke

At stroke onset

Between 0 and 3 months

Between 3 and 6 months

Onset of headache:

Figure 4 Time of headache onset.

A.P. Hansen et al.

Post-stroke pain

1133

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

3.9 Central post-stroke pain

Possible CPSP was identified in 10.5% (NRS

ⱖ 4:

75.9%). Further characteristics are displayed in

Table 2. Patients with possible CPSP were more often

women (p

= 0.042), and they were slightly younger

than the remaining patients (mean age 60.4 vs. 66.2

years, p

= 0.025). The pain was located in the upper

extremity in 37.9%, the lower extremity in 20.7%, in

both upper and lower extremities in 10.3%, in the

head in 16.0%, in both head and lower extremity in

3.4%, and in one entire side of the body in 10.3%. The

pain was spontaneous in 65.5% of the patients with

possible CPSP, both spontaneous and evoked in

20.7%, and solely evoked in 13.8%. The DN4 scale

was applied on the 27 patients who were followed up

by phone and a score of 3 or more on the 7-item DN4

concerning items related to the possible CPSP was

found in 48.1% of these patients. The item pins and

needles was experienced by 63.0.%, tingling by 48.1%,

burning by 29.6%, numbness by 37.0%, while electric

shocks, painful cold and itching were experienced by less

than 20% of the patients with possible CPSP.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the

incidence of all common pain types following stroke in

a prospective study with 3-month and 6-month

follow-up interviews. Since we did not include a

control group, we cannot determine how much of the

pain is attributed to the stroke. Nevertheless, the fact

that two-thirds of all stroke patients reported pain 6

months after stroke and nearly half of the patients with

pain reported the pain to be newly developed indicates

that pain is an important consequence of stroke.

In a retrospective study, Naess et al. (2010) found

that 44.6% had post-stroke pain 1 year after stroke,

similar to the 45.8% at 6 months found in this study.

Lundstrom et al. (2009) found stroke-related pain

defined as pain that started after stroke and was

located in the paretic side of the body in 21% 1 year

after stroke, which corresponds to our 22.6% of

patients with pain in the stroke-affected side at 6

months. Thus, our study indicates a high incidence of

newly developed already 6 months after stroke.

The high incidence of headache at stroke onset in

one-third of the patients is similar to the 27% with

headache in relation to stroke found by Vestergaard

et al. (1993). The patients with headache in our study

were younger at stroke onset and more often female,

which is consistent with other studies (Tentschert et al.,

2005). Patients were asked about prior headache at the

time of their stroke where other major symptoms and

signs may have obscured the perception of headache or

the likelihood to report that symptom leading to a

possible underestimation. Headache at stroke onset

was a predictor for headache 6 months after stroke. Our

results indicate that headache following stroke gener-

ally resembles a tension-type headache with the main

description of the headache being pressing, not aggra-

vated by movement and with a moderate intensity

(mean NRS 4–5), in consistency with previous studies

(Vestergaard et al., 1993; Widar et al., 2002).

Newly developed shoulder pain was reported by

16.4% (45/275) at 6 months and the majority of these

patients (33) had pain in the stroke-affected side. The

underlying mechanisms of shoulder pain and its rela-

tion to stroke are not examined in this study but have

previously been associated with paresis, abnormal

joint postures, muscle overuse or nerve damage

(Gamble et al., 2002; Roosink et al., 2011).

Possible CPSP was suspected in 10.5%. This figure of

CPSP is slightly higher than the incidence of 8.0%

reported by Andersen et al. (1995) and the incidence of

7.3% reported by Klit et al. (2011). Half of the patients

with possible CPSP (48.1%) had a DN4 score

ⱖ 3,

which may indicate a low sensitivity. However, we are

not in a position based on the present results to deter-

mine the sensitivity or specificity of the DN4 to detect

neuropathic pain. The sensitivity and specificity of the

DN4 to detect neuropathic pain has been found to be

much higher in other studies (Bouhassira et al., 2005).

In the present study, we have only used a telephone

interview and only included items that were reported

in an area in close proximity to the area of the possible

CPSP to classify the pain. Therefore, it is likely that the

DN4 score would be higher if the patient sample was

restricted to patients with probable or definite CPSP. We

are currently carrying out a detailed examination

including a DN4 questionnaire of these patients with

possible CPSP to find out who has definite or probable

neuropathic pain (Klit et al., manuscript in prepara-

tion). We cannot exclude that some of the patients

classified with shoulder pain in fact have CPSP, and the

incidence of possible CPSP would have been 13.5% if

patients with shoulder pain fulfilling the pre-defined

criteria for CPSP were included (Klit et al., 2011;

Roosink et al., 2010).

We believe that the reason for the negative trend of

the development of shoulder pain and CPSP at

follow-up interviews in relation to stroke onset is that

these pain types develop over time whereas headache

often starts simultaneously with stroke. The preva-

lence of CPSP may be underestimated in this study

due to the relatively short follow-up period.

Post-stroke pain

A.P. Hansen et al.

1134

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

Forty-five percent of the consecutively admitted

patients were not included in the studies due mainly

to aphasia, dementia, weariness and loss of conscious-

ness. Therefore, our result may not be representative

for a non-selected group of stroke patients. However,

an analysis of excluded patients suggested similar inci-

dence of newly developed pain as in the included

patients.

Part of the reported pain in this study might be

attributed to other factors, e.g. cardiovascular disease

with the higher incidence of previous stroke and acute

myocardial infarction in the patients with newly deve-

loped pain. Prior post-stroke pain might be an influence

on reported pain and be a potential pre-existing pain

condition which involves 17.9% of the patients. In this

study, we have explicitly concentrated on newly devel-

oped pain after the actual stroke and therefore believe

that a former stroke-related pain condition does not

have a major influence on the present results. Another

factor for influencing reported pain is treatment with

dipyridamole (Persantine®) inducing a newly deve-

loped headache in the patients with headache at the

follow-up interviews.

The strength of our study is its prospective character

and that it distinguishes between pain before stroke

and pain after stroke by questioning the patients about

pre-existing pain at the time of admission. Since we

asked for pain during the previous 3 months, we cannot

exclude some recall bias for this parameter and it is

possible that patients may neglect some of their prior

pain when submitted to a hospital for a critical illness.

Recall bias at follow-up was minimized by asking the

patients about their pain in the last week before the

interviews. However, the narrow time frame makes it

impossible to classify the pain as chronic pain.

5. Conclusion

The high incidence of pain following stroke suggests

that pain in stroke survivors should be recorded,

analysed and managed if severe. Patients may have

more than one type of pain which could complicate

their rehabilitation.

References

Adams, H.P., Jr, Bendixen, B.H., Kappelle, L.J., Biller, J., Love,

B.B., Gordon, D.L., Marsh, E.E., 3rd. (1993). Classification of

subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a

multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute

Stroke Treatment. Stroke 24, 35–41.

Andersen, G., Vestergaard, K., Ingeman-Nielsen, M., Jensen, T.S.

(1995). Incidence of central post-stroke pain. Pain 61, 187–

193.

Bouhassira, D., Attal, N., Alchaar, H., Boureau, F., Brochet, B.,

Bruxelle, J., (2005). Comparison of pain syndromes associated

with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new

neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain 114,

29–36.

Bouhassira, D., Lanteri-Minet, M., Attal, N., Laurent, B.,

Touboul, C. (2008). Prevalence of chronic pain with neuro-

pathic characteristics in the general population. Pain 136,

380–387.

Bowsher, D. (2001). Stroke and central poststroke pain in an

elderly population. J Pain 2, 258–261.

Ferro, J.M., Melo, T.P., Guerreiro, M. (1998). Headaches in

intracerebral hemorrhage survivors. Neurology 50, 203–

207.

Gamble, G.E., Barberan, E., Laasch, H.U., Bowsher, D., Tyrrell,

P.J., Jones, A.K. (2002). Poststroke shoulder pain: a prospec-

tive study of the association and risk factors in 152 patients

from a consecutive cohort of 205 patients presenting with

stroke. Eur J Pain 6, 467–474.

Jonsson, A.C., Lindgren, I., Hallstrom, B., Norrving, B.,

Lindgren, A. (2006). Prevalence and intensity of pain after

stroke: a population based study focusing on patients’ perspec-

tives. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77, 590–595.

Klit, H., Finnerup, N.B., Andersen, G., Jensen, and T.S. (2011).

Central poststroke pain: A population-based study. Pain 152,

818–824.

Klit, H., Finnerup, N.B., Jensen, T.S. (2009). Central post-stroke

pain: clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and manage-

ment. Lancet Neurol 8, 857–868.

Kolominsky-Rabas, P.L., Weber, M., Gefeller, O., Neundoerfer,

B., Heuschmann, P.U. (2001). Epidemiology of ischemic

stroke subtypes according to TOAST criteria: incidence, recur-

rence, and long-term survival in ischemic stroke subtypes: a

population-based study. Stroke 32, 2735–2740.

Kong, K.H., Woon, V.C., Yang, S.Y. (2004). Prevalence of chronic

pain and its impact on health-related quality of life in stroke

survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85, 35–40.

Langhorne, P., Stott, D.J., Robertson, L., MacDonald, J., Jones,

L., McAlpine, C., Dick, F., Taylor, G.S., Murray, G. (2000).

Medical complications after stroke: a multicenter study. Stroke

31, 1223–1229.

Lindenstrøm, E., Boysen, G., Christiansen, L.W., Hansen, B.R.,

Nielsen, P.W. (1991). Reliability of Scandinavian neurological

stroke scale. Cerebrovasc Dis 1, 103–107.

Lindgren, I., Jonsson, A.C., Norrving, B., Lindgren, A. (2007).

Shoulder pain after stroke: a prospective population-based

study. Stroke 38, 343–348.

Lundstrom, E., Smits, A., Terent, A., Borg, J. (2009). Risk factors

for stroke-related pain 1 year after first-ever stroke. Eur J

Neurol 16, 188–193.

Naess, H., Lunde, L., Brogger, J., Waje-Andreassen, U. (2010).

Post-stroke pain on long-term follow-up: the Bergen stroke

study. J Neurol 257, 1446–1452.

Ratnasabapathy, Y., Broad, J., Baskett, J., Pledger, M., Marshall,

J., Bonita, R. (2003). Shoulder pain in people with a stroke: a

population-based study. Clin Rehabil 17, 304–311.

Roosink, M., Geurts, A.C., Ijzerman, M.J. (2010). Defining post-

stroke pain: diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol 9,344; author

reply 344–345.

Roosink, M., Renzenbrink, G.J., Buitenweg, J.R., van Dongen,

R.T., Geurts, A.C., Ijzerman, M.J. (2011). Somatosensory

symptoms and signs and conditioned pain modulation in

chronic post-stroke shoulder pain. J Pain 12, 476–485.

A.P. Hansen et al.

Post-stroke pain

1135

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

Tentschert, S., Wimmer, R., Greisenegger, S., Lang, W.,

Lalouschek, W. (2005). Headache at stroke onset in 2196

patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Stroke 36, e1–e3.

Verdelho, A., Ferro, J.M., Melo, T., Canhao, P., Falcao, F. (2008).

Headache in acute stroke. A prospective study in the first 8

days. Cephalalgia 28, 346–354.

Vestergaard, K., Andersen, G., Nielsen, M.I., Jensen, T.S. (1993).

Headache in stroke. Stroke 24, 1621–1624.

Weimar, C., Kloke, M., Schlott, M., Katsarava, Z., Diener, H.C.

(2002). Central poststroke pain in a consecutive cohort of

stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis 14, 261–263.

Widar, M., Ek, A.C., Ahlstrom, G. (2004). Coping with long-term

pain after a stroke. J Pain Symptom Manage 27, 215–225.

Widar, M., Samuelsson, L., Karlsson-Tivenius, S., Ahlstrom, G.

(2002). Long-term pain conditions after a stroke. J Rehabil Med

34, 165–170.

Post-stroke pain

A.P. Hansen et al.

1136

Eur J Pain 16 (2012) 1128–1136 © 2012 European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain Chapters

Copyright of European Journal of Pain is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Pain Following Stroke A Population Based Follow Up Study

Pain following stroke, initially and at 3 and 18 months after stroke, and its association with other

Ebsco Bialosky Manipulation of pain catastrophizing An experimental study of healthy participants

Ebsco Bialosky Manipulation of pain catastrophizing An experimental study of healthy participants

Chronic Pain Syndromes After Ischemic Stroke PRoFESS Trial

Evidence for Therapeutic Interventions for Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain During the Chronic Stage of Stro

Prospective Demographic Study

Chronic Pain Syndromes After Ischemic Stroke PRoFESS Trial

Changes in Negative Affect Following Pain (vs Nonpainful) Stimulation in Individuals With and Withou

Effect of sensory education on school children’s food perception A 2 year follow up study

Badania obserwacyjne prospektywne (kohortowe)

A Behavioral Genetic Study of the Overlap Between Personality and Parenting

Aneks nr 2 Prospekt PKO BP 05 10 2009

CEREBRAL VENTICULAR ASYMMETRY IN SCHIZOPHRENIA A HIGH RESOLUTION 3D MR IMAGING STUDY

więcej podobnych podstron