dog might be bred).

4

Preventing less valued individuals from

procreating would prevent their weaknesses being passed on to

the next generation and improve the overall stock. At the time,

eugenics was popular on both the political right and left, with

many a notable enthusiast in Europe and in the USA. In Aus-

tralia, the condemnation of ‘breeding’ of indigenous people and

Caucasian settlers, the removal and isolation of mixed race

children and the White Australia policy would all be defended

through eugenics.

5

In these early years, the emphasis of eugenics was on preven-

tion of reproduction, mainly by means of sterilisation, rather

than euthanasia. It would be in post-First World War Germany,

however, that it would be developed to include euthanasia. In

Permission for the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life,

6

published in

Germany in 1920, the academic lawyer Karl Binding and psy-

chiatrist Alfred Hoche argued that sentimentality over the sanc-

tity of life prevented the necessary task of removing ‘mentally or

intellectually dead’ individuals who contributed nothing. Why,

they asked, should such people be cared for at great cost with

little or no public benefit, when the state had sacrificed a gen-

eration of healthy, productive young men on the battlefield?

The increasingly dire socio-economic predicament of post-First

World War Germany allowed such arguments to gain momen-

tum and set the scene for the rise and seizure of power of Adolf

Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1933.

The Rise of the Nazis and a Chance Letter

The concept of racial and genetic superiority was at the forefront

of Nazi ideology. Before obtaining power, at a Nuremberg Party

Rally in 1929, Hitler introduced a future direction: ‘If Germany

was to get a million children a year and was to remove 700–

800 000 of the weakest people then the final result might even

be an increase in strength’.

1

Although compulsory sterilisation

of people with disabilities commenced early on in Hitler’s dic-

tatorship, a formal euthanasia programme did not occur until

the war began, strangely prompted by a chance letter sent to

Hitler.

The letter came from Richard Kretschmar, the father of a male

infant born with severe disabilities in Germany in late 1938. He

had already approached his local paediatrician, Dr Werner Catel,

asking that his son receive a mercy killing but Catel refused

because it was illegal. Unhappy with this decision, the father

wrote directly to Hitler requesting permission for his child to be

killed. The letter was brought to the attention of Hitler, who sent

his personal physician, Dr Karl Brandt, to investigate further.

Brandt testified on the case at his own trial in 1946: ‘The father

of a deformed child wrote to the Fuhrer with a request to be

allowed to take the life of this child or this creature. Hitler

ordered me to take care of this case. The child had been born

blind, seemed to be idiotic, and a leg and part of the arm were

missing’.

7

After Brandt’s visit, the case went in the favour of the

father and the child was killed.

Motivated by the Kretschmar case, and with the country now

at war, the Nazis seized the opportunity to legislate for a more

consistent approach for similar children. Doctors and midwives

across Germany were mandated to report not only infants born

with congenital illnesses, but also children with existing prob-

lems up to the age of three. The centralised Reich Committee for

the scientific registering of serious hereditary and congenital suffering

would then review notifications. Firstly, two laymen would

choose appropriate cases and then pass them on to three phy-

sicians (including Dr Werner Catel). The physicians would then

mark the cases with a ‘

+’ or a ‘–’, indicating whether the chil-

dren were considered appropriate for euthanasia. Once agree-

ment was secured between the physicians, the children would

be located and taken from their parents to various clinics (some

new and some in existing children’s hospitals and clinics) where

doctors and nurses would organise their demise. Efforts would

be made to take the child to an institution some distance from

their home to discourage parents visiting. Sedating medicines

such as phenobarbitol were used to induce respiratory failure

and arrest or in some cases, the children were reported to have

been left to starve to death.

8

Once the child had died, a fake

illness would be fabricated, commonly measles or ‘weakness’.

The child would be cremated and the parents would be

informed by letter, letters ending with the bold authority of the

salutation: Heil Hitler!

Parents: Cause and Effect

The Kretschmar case illustrates that some parents may have felt

the death of a severely disabled child to be appropriate. Bringing

up a disabled child in wartime Germany would have been

difficult for then, as now, disability carried with it huge stigma.

Disability would have been a source of personal guilt and impli-

cation for parents, in particular for mothers. Attitudes would

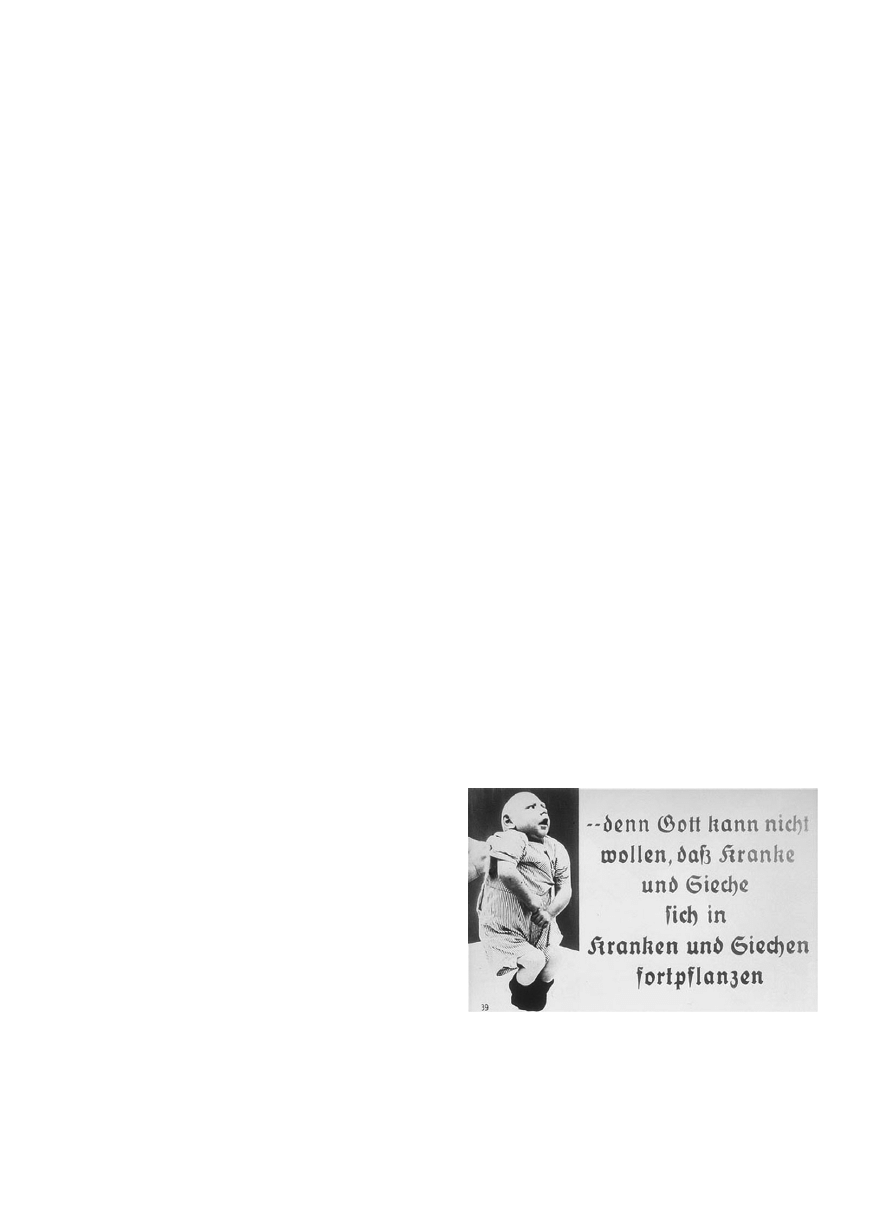

have been compounded by the propaganda that the Nazis pro-

duced about people and children with disabilities. Powerful

films and posters (such as the one in Fig. 1) aimed at invoking

public sympathy for a euthanasia programme. Mathematical

questions on the costs of providing care for people with disabili-

ties versus food for families and wartime supplies appeared in

standard school textbooks.

There would also have been financial and social pressure for

mothers raising children alone while fathers were posted at the

front. There is evidence that parents handed over their disabled

Fig. 1

“Propaganda slide featuring a disabled infant”. The caption reads

“. . . because God cannot want the sick and ailing to reproduce.” Circa

1934, Germany. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of

Marion Davy. Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

L Hudson

Nazi euthanasia of children

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health

47 (2011) 508–511

© 2011 The Author

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health © 2011 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

509

children to the authorities for temporary, respite periods not

knowing what treatment they would receive.

9

One father took

his disabled one-year-old son to an asylum in Scheuern in 1937

after the child’s mother had died as he was unable to bring the

child up alone. After remarrying in 1941, he was refused a

request for the return of his son, told by letter from the asylum

that ‘the child is to a high degree feeble-minded and is a fun-

damental case needing pure nursing care. As a result he is

utterly unsuited to being cared for in the family’. The boy was

sent onto Hadamar two years later where he was killed.

9

In fact, for most families, the planned outcome for their child

was unknown as they handed their children over in good faith.

Maria H, whose daughter was born with abnormal facies in

1939, was persuaded by her family doctor that she would be

best cared for at the paediatric clinic of Egling-Haar, some dis-

tance from her home.

8

Trusting, she consented. She received

written notification a month later that her baby had died of

pneumonia. Four-year-old Friedrich S was taken to a paediatric

clinic in Eichberg after developing neurological complications

secondary to meningitis.

8

His family received a letter from the

clinic doctor after his arrival saying that a course of ‘treatment’

had been commenced. They managed to visit him a month later,

finding him malnourished and bruised, but on trying to take

him home, they were prevented, receiving a letter two weeks

later to tell them he had died.

Despite attempts at secrecy about the programme, suspicion

was ignited, especially in the local populace. Children playing in

the streets near the Hadamar clinic would chant ‘here come the

murder boxes’ in reference to the blackened window buses that

brought new patients for euthanasia to the clinic.

9

Some who

were brave enough would make public protest and some would

be punished as a consequence. Increasing public awareness and

discontent may have contributed to the ending of ‘T4’ (the adult

disability euthanasia programme) in 1941, but the bulk of the

work was probably done by then, and larger, racially motivated

crimes outside Germany in the East may have been considered

of larger priority. The child programme continued, enlarging to

encompass more acquired disabilities and even to children dis-

playing antisocial behaviour.

9

Discarding Hippocrates

The involvement of medical staff in the killing of children espe-

cially those specialising in paediatrics seems surprising and

shocking. It is tempting to explain this away as obedient behav-

iour with fear of punishment upon refusal, but there is much to

counter this explanation.

Although the Nazi party provided political and legal authority

for euthanasia, the medical philosophy and will was already

established in Germany before Hitler came to power. At the

beginning of Hitler’s dictatorship, almost half of paediatricians

in Germany were Jewish.

10

Gradual persecution and profes-

sional exclusion led to many emigrating or eventually being

killed themselves in the holocaust, leaving a large professional

vacuum to be filled by physicians of Nazi persuasion. Indeed,

nearly half of practicing doctors in Nazi Germany were members

of the Nazi Party.

11

Doctors received distinguished professorial

posts for involvement and were more likely to secure research

grants from the government.

12

Medical staff were paid more for

work in euthanasia centres.

13

To understand the mindset of the Nazi doctor involved in

euthanasia, we can look to Dr Werner Catel, the Paediatrician

involved in the original Kretschmar case. Catel, a prominent

Nazi who played a central role in the euthanasia of children

both at a local and national level, was cleared of criminal

charges after the war and would continue to be a proponent for

euthanasia of disabled children. Catel insisted that he had

helped children and their families by killing disabled children:

‘the physician who made the diagnosis must explain the situa-

tion to the parents. He must tell them the truth especially that

this creature cannot be helped anymore, that it will never

becomes a human being’.

14

Contrast this with the Jewish female

Paediatrician Dr Lucie Adelsberger. Herself interred in Aus-

chwitz, Adelsberger was doctor for the small (and eventually

exterminated) gypsy population in Auschwitz: ‘The only thing

doctors could do for their patients, emaciated, skeletal or

swollen with edema of starvation and wallowing in feverish

deliriums, was to comfort them. It didn’t make them any better,

they still died like flies’.

10

Care for and comfort them, in other

words, not kill them yourself like Catel.

There were doctors who refused to participate. Dr Friedrich

Hozel, a Nazi, was asked by seniors to head a child euthanasia

programme and refused. He explained: ‘I am reminded of the

difference which exists between a judge and an executioner

. . . lively as my desire is in many cases to improve upon the

natural course of things, it is equally repugnant to me to carry

this out as a systematic policy after cold-blooded deliberation

and according to objective scientific principles, and without any

feeling towards the patient’.

11

There is no evidence that German

doctors and nurses who refused to participate received punish-

ment. Doctors such as Dr Hozel went to work safely elsewhere.

This is in contrast to doctors in Holland who collectively refused

to carry out Nazi orders to collude with the Nazi policy of

euthanasia on their patients during their occupation, some of

whom were sent to concentration camps as a consequence.

15

Conclusions

How can we prevent physicians becoming involved with

medical atrocities in the same way again? To answer this ques-

tion, we should perhaps look to Dr Leo Alexander, the Ameri-

can psychiatrist who gave medical advice at the Nuremberg

Trials, wrote parts of the Nuremberg Code and witnessed

first-hand the individual doctors who were tried for war crimes.

He argued that ‘Science under dictatorship becomes subordi-

nated to the guiding philosophy of the dictatorship’.

15

All gov-

ernments in some way control the health-care system in their

countries, but self-regulatory bodies such as the Royal Colleges

can allow independence from government and provide separate

guidance on complex issues such as withdrawing care. Alex-

ander also warned that in the Nazi state, crimes and atrocities

‘started from small beginnings’.

15

The gradual acceptance of Nazi

State policy by physicians over the unworthiness of some indi-

viduals to deserve life allowed them to first kill severely disabled

children. Once adapted to this, they were able to move on to

older children with existing and lesser disabilities, to adults and

eventually to anyone considered unsuitable of life by the state.

Nazi euthanasia of children

L Hudson

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health

47 (2011) 508–511

© 2011 The Author

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health © 2011 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

510

In Nazi society individuals were measured by their civic or

financial value, as well as speculative future worth or potential

danger. Disabled children would grow to become disabled,

unproductive adults who might procreate and pass on their

problems and so were killed; jewish children would become

jewish adults and so were killed. In modern times of financial

difficulty, arguments over the rationalisation of health-care pro-

vision can include focusing on the value or civic return for

investment for an individual rather than upon need. We should

be mindful of where this has led in the past.

The Nazi euthanasia programme should also make us reflect

upon how we as individuals and as a society react to adults and

children with disabilities. The nameless stranger with a disability

in the street can evoke an array of emotional responses includ-

ing pity, anger, frustration and confusion until we know that

person as an individual, as part of our family, as our friend, our

colleague or as our patient. Today, as under the Nazis, children

and adults with disabilities are sometimes considered as outside

of society rather than part of it and in so doing, may be seen as

a burden or apportioned blame. Blame can be a natural

response to disability or any illness that frustrates us (this

patient is not trying, is not complying). Blame alleviates our

frustration, guilt and shame, which ultimately diminishes our

civic or moral responsibility. If we are not careful, this can lead

to their neglect, or in the case of the Nazis, their destruction.

Acknowledgements

The contents of the paper were presented as an oral presenta-

tion for The British Society for the History of Paediatrics and

Child Health (BSHPCH) autumn meeting in Liverpool, UK in

2010.

References

1 Kershaw I. In: Chapter 17: Licensing Barbarism eds. Hitler

(One-Volume Abridgment of Hitler 1889–1936 and Hitler 1936–1945).

London: Penguin Books, 2009; 532.

2 Report of the House of Lords Select Committee on Medical Ethics (HL

Paper 21-I of 1993–4). London: HMSO, 1994; paragraph 20–21.

3 When Death is Sought: Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia in the

Medical Context. New York: New York State Task Force on Life and the

Law, 1994. Executive summary.

4 Galton F. The possible improvement of the human breed under

the existing conditions of law and sentiment. Nature 1901;

64:

659–65.

5 Wyndham D. Eugenics in Australia: Striving for National Fitness.

London: The Galton Institute, 2003.

6 Hoche A, Binding K. Die Freigabe der Vernichtung Lebensunwerten

Lebens. Leipzig: Felix Meiner Verlag, 1920.

7 Schmidt U. Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor. London: Hambledon

Continuum, 2007.

8 Burleigh M. In: Chapter 3, ‘Wheels must roll for victory!’ Children’s

‘euthanasia’ and ‘Aktion T-4’. eds. Death and Deliverance:

‘Euthanasia’ in Germany C. 1900–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1994; 100–7.

9 Stargardt N. In: Chapter 3, Medical murder, eds. Witnesses of War,

Children’s Lives under the Nazis. New York: Alfred A. Knopf

Publishing, 2006; 81–102.

10 Saenger P. Jewish pediatricians in Nazi Germany: victims of

persecution. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2006;

8: 324–8.

11 Burleigh M. In: Chapter 5, ‘Eugenics and Euthanasia’ eds. The Third

Reich a New History. London: Pan Books, 2000; 386–88.

12 Friedlander H. In: Chapter 11, ‘Physicians and other killers’ eds. The

Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution.

Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995; 216–45.

13 Benedict S. Nurses’ participation in the Nazi euthanasia programs.

West. J. Nurs. Res. 1999;

21: 246–63.

14 Parent S, Shevell M. The ‘first to perish’. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med.

1998;

152: 79–86.

15 Alexander L. Medical science under dictatorship. N. Engl. J. Med.

1949;

241: 39–47.

L Hudson

Nazi euthanasia of children

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health

47 (2011) 508–511

© 2011 The Author

Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health © 2011 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (Royal Australasian College of Physicians)

511

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Brothers and Sisters of Children with Disabilities Medicine Jessica Kingsley Publishers

The Presentation of Self and Other in Nazi Propaganda

Differences between the gut microflora of children with autistic spectrum disorders and that of heal

Locke and the Rights of Children

APA practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder

Kosky; Ethics as the End of Metaphysics from Levinas and the Philosophy of Religion

Geoffrey Hinton, Ruslan Salakhutdinov Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks

A Propagandist of Extermination, Johann von Leers and the Anti Semitic Formation of Children in Nazi

Wicca Book of Spells and Witchcraft for Beginners The Guide of Shadows for Wiccans, Solitary Witche

Jóźwiak, Małgorzata; Warczakowska, Agnieszka Effect of base–acid properties of the mixtures of wate

Paul Ricoeur From Existentialism to the Philosophy of Language

Shel Leanne, Shelly Leanne Say It Like Obama and WIN!, The Power of Speaking with Purpose and Visio

Latour Pursuing the Discussion of Interobjectivity With a Few Friends

Stories from a Ming Collection The Art of the Chinese Story Teller by Feng Menglong tr by Cyril Bir

Fishea And Robeb The Impact Of Illegal Insider Trading In Dealer And Specialist Markets Evidence Fr

The Keys of Basilus With Commentary

2002 04 Migration the Benefits of Browsing with Konqueror

więcej podobnych podstron