1

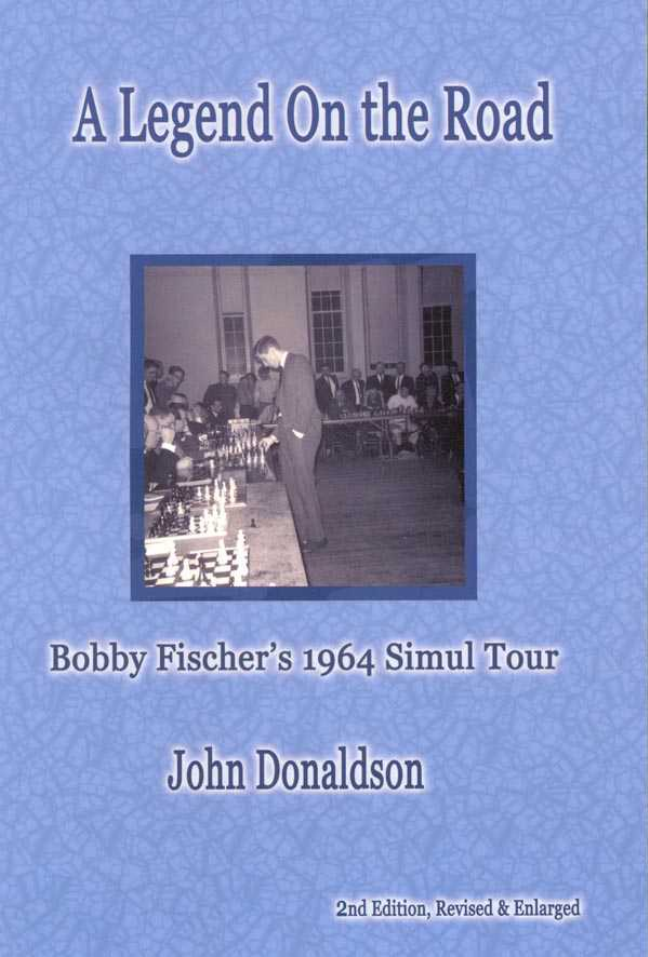

A Legend

on the

Road

Bobby Fischer’s 1964

Simultaneous Exhibition Tour

Second Edition

John Donaldson

2005

Russell Enterprises, Inc.

Milford, CT USA

3

Table of Contents

Bobby Fischer’s 1964 Simul Tour

Introduction to the Second Edition

Introduction to the First Edition

February 1964

Detroit

Rochester

Waltham

Montreal

Quebec City

Toronto

March 1964

Westerly

Fitchburg

Hartford

Richmond

Washington, D.C.

New York

Pittsburgh

Cleveland

Toledo

Chicago

Baton Rouge

New Orleans

Houston

Little Rock

Hot Springs

April 1964

Wichita

Ogden

Hollywood

San Francisco

Sacramento

Davis

Santa Barbara

Santa Monica

Las Vegas

Denver

May 1964

Cheltenham

Boston

Milwaukee

Flint

Columbus

Cicero

Indianapolis

New York

State College

Bibliography

Index of Players, ECO Codes, & Openings

4

5

7

14

36

108

160

194

195

4

Bobby Fischer’s 1964 Simul Tour

February

9

Detroit

51 (+47, -2, =2)

15

Rochester

75 (+69, -1, =5)

20

Waltham

40 (+39, -0, =1)

23

Montreal

55 (+46, -5, =4)

24

Montreal (clock simul)

10 (+10, -0, =0)

25

Quebec City

48 (+48, -0, =0)

27

Toronto

50 (+40, -4, =6)

March

1

Westerly

47 (+44, -1, =2)

2

Fitchburg

56 (+49, -5, =2)

3

Hartford

55 (+49, -2, =4)

5

Richmond

50 (+44, -4, =2)

8

Washington, D.C.

65 (+52, -4, =9)

?

New York

30 (+30, -0, =0)

15

Pittsburgh

53 (+50, -1, =2)

18

Cleveland

51 (+51, -0, =0)

19

Toledo

55 (+50, -3, =2)

22

Chicago

71 (+56, -4, =11)

23

Chicago

54 (+49, -1, =4)

25

Baton Rouge

5 (+5, -0, =0)

25

Baton Rouge

2 (+2, -0, =0) vs. Acers

26

New Orleans

75 (+70, -3, =2)

28

Houston

57 (+51, -3, =3)

29

Little Rock

36 (+36, -0, =0)

30

Hot Springs

1 (+1, -0, =0) vs. Allbritton

April

4

Wichita

40 (+38, -1, =1)

8

Ogden

63 (+60, -1, =2)

12

Hollywood

50 (+47, -1, =2)

13

San Francisco

50 (+38, -4, =8)

15

Sacramento

50 (+47, -2, =1)

16

Davis (clock simul)

10 (+10, -0, =0)

18

Santa Barbara

52 (+49, -2, =1)

19

Santa Monica

50 (+45, -3, =2)

??

Las Vegas (exact date unknown)

35 (+34, -0, =1)

26

Denver

55 (+50, -1, =4)

May

3

Cheltenham

73 (+70, -2, =1)

10

Boston

53 (+50, -1, =2)

14

Milwaukee

57 (+48, -4, =5)

16

Flint

58 (+53, -0, =5)

18

Columbus

50 (+48, -0, =2)

20

Cicero

50 (+44, -1, =5)

21

Indianapolis

50 (+48, -1, =1)

24

New York

34 (+34, -0, =0)

31

State College

50 (+49, -0, =1)

Total (known games)

2022 (+1850, -67, =105) (94%)

5

Introduction to the Second Edition

This edition contains all the material relating to Fischer’s 1964 tour that

previously appeared in the first edition of A Legend on the Road and The

Unknown Bobby Fischer, plus original material I’ve gathered for this

volume. New highlights include the rediscovery of a forgotten visit to

Indianapolis by Bobby and remembrances of simuls by Jude Acers (Baton

Rouge and New Orleans), Carl Branan (Houston), C. Richard Long (Little

Rock), Marty Lubell (Pittsburgh), and Michael Morris (San Francisco).

There are several new photographs and documents relating to the tour.

This time around I would like to thank my editor Taylor Kingston and

publisher Hanon Russell, as well as Jude Acers, Todd Bardwick, Frank

(Kim) Berry, Gary Berry, Gary Bookout, Carl Brannan, Neil Brennen, Ojars

Celle, Mark Donlan, C. Richard Long, Marty Lubell, Jeff Martin (John G.

White Collection of the Cleveland Public Library), Hardon McFarland,

Michael Morris, Robert Peters, Eric Tangborn and Val Zemitis for their

help. I would especially like to thank Holly Lee. This book would not have

been possible without their efforts.

I continue to be amazed at how warmly and vividly people remember

Bobby’s tour of forty years ago.

John Donaldson

Berkeley, March 2005

Explanation of Symbols

(O.G.) Indicates the source is the original game score itself.

All editor’s notes are by John Donaldson, from either the first edition or

The Unknown Bobby Fischer, unless indicated otherwise by “TK” (Taylor

Kingston).

6

Preface to The Unknown Bobby Fischer

The idea for The Unknown Bobby Fischer (1999) came shortly after the publica-

tion of A Legend on the Road (1994). The many readers who wrote me after the

appearance of Legend offered a wealth of new material with games and anec-

dotes. Sometimes gold would appear in the most unexpected places.

Playing in the 1997 McLaughlin Memorial in Wichita, I was delighted to meet

former Kansas Champion Robert Hart, who had kept his copy of the mimeo-

graphed bulletin of Bobby’s 1964 visit to Wichita. I had heard rumors of this

bulletin, but until Mr. Hart generously sent me the games, I feared that all existing

copies had disappeared. My Unknown Bobby Fischer co-author Eric Tangborn

and I, with the help of Erik Osbun, were able, using a little detective work, to

convert 18 of the games (one score was unreadable) from sometimes question-

able descriptive notation into playable algebraic. Only D Ballard’s win, Fischer’s

sole loss in the exhibition, was previously known. The games from this exhibi-

tion offer a rare look at a typical Fischer simul — usually only a few wins and,

more typically, his losses and draws, surface.

I would like to thank Denis Allan, D La Pierre Ballard, Frank (Kim) Berry,

Jonathan Berry, Neil Brennen, Ross Carbonell, George Flynn, Steve Gordon,

Gordon Gribble, Robert Hart, Holly Lee, David Luban, Richard Lunenfeld, Jerry

Markley, Spencer Matthews, Robert Moore, The Mechanics’ Institute (San Fran-

cisco) Library, Erik Osbun, Jack O’Keefe, Duane Polich, Nick Pope, Donald P.

Reithel, Thomas Richardson, Hanon Russell, Andy Sacks, Macon Shibut, Eric

Tangborn, Alex Yermolinsky and Val Zemitis for their help with this project.

John Donaldson

Berkeley, October 1999

7

Introduction to the First Edition

Transcontinental exhibition tours have a long and honored history in North

America. World Champions Alexander Alekhine and José Capablanca were two

of the first to make the 3,000-mile trek. A trek that was most useful for populariz-

ing the game in distant outposts, where masters were all but nonexistent. Names

like Reshevsky, Horowitz, Kashdan, Fine, and Marshall became better known to

the chess public outside of New York as a result of their barnstorming. The tour-

ing masters were well received and taken care of. Horowitz, in particular, kept his

struggling Chess Review alive by periodically hitting the road and spreading the

word to the faithful.

Since World War II this type of tour has been increasingly rare. Various explana-

tions could be offered but undoubtedly one major reason is the proliferation of

weekend Swiss tournaments and the simultaneous decline of local chess clubs.

The result is that in recent memory only Walter Browne’s 1978 18-stop tour and

the “Church’s Chicken” tours of Larry Christiansen and Jack Peters come close

to some of the classic treks of the past.

Between the great barnstormings of the 1930s and the late 1970s only one great

tour was undertaken but it was arguably the greatest of them all. Not even Alekhine

and Capablanca, who were in high demand — each made several major tours —

ever came close to this granddaddy of road trips.

Starting in February of 1964 and going until the end of May, Bobby Fischer’s

only major exhibition tour was record-breaking in all aspects, from the number of

players he played (close to 2000) to the fee he commanded (a then unheard-of

$250 an exhibition).

Bobby, of course, had prior experiences with exhibitions. In fact, his first chess

event was playing master Max Pavey in a simul at the Brooklyn Public Library in

January of 1951. The first major exhibition Fischer gave, against 12 children,

was written about in the Jan. 1956 issue of Chess Review.

Fischer’s early opinion of simul play was not particularly high. A 1957 issue of

Parade had this to say: “To make money, Bobby has taken on as many as 30

challengers simultaneously at $1 a challenger. But such games, he says, ‘don’t

produce good chess. They’re just hard on your feet.’” Fischer’s feelings about the

quality of play changed in the following years with several games from the tour

being featured in the American Chess Quarterly and the game with Celle chosen

for inclusion in My 60 Memorable Games.

During the next six years Bobby gave several exhibitions, mostly in the New

York area, but the only one that attracted any attention was one that was never

held. The following announcement appeared in the first issue of the excellent but

ill-fated Chessworld:

8

Fischer will attempt to break Gideon Stahlberg’s 1941 record of 400 oppo-

nents Wednesday, November 27, 1963, 7:30 p.m., Grand Ballroom, Hotel

Astor, Broadway and 44th, NYC. $3 to play, $1 to watch. Organized by

CHESSWORLD.

Five days before the event it was cancelled because of the assassination of Presi-

dent Kennedy.

When 1964 began, Fischer was on a roll. The 20-year-old GM had just won his

6th U.S. Championship and he had done so in spectacular fashion, scoring 11-0!

With the Amsterdam Interzonal scheduled for the spring there was much talk

about Bobby’s run for the World Championship.

The genesis of the tour appears to be the following letter, which appears courtesy

of the Russell Collection.

From: Bobby Fischer

To: Larry Evans

Date: Sept. 15, 1963

Dear Larry,

Nice talking to you on the phone Saturday. About the books, if you send me

a list please mark down what condition they’re in. Another thing last Decem-

ber when you were in New York you said you were interested in setting up an

exhibition tour if I brought my price down. How does $300 strike you: 35-40

boards plus lecture on a game or two. I don’t know what percentage or fee

you would want for this but I think we can work that out if you agree to my

terms above. If you’re not interested, what with $200 rolling in maybe you

could set up something at one of the strip hotels for me.

By the way there IS one mistake in my next Chess Life article. I caught it

when I was going over it for typographical errors. It’s in my annotations to

my game with Berliner. It was not too late to have it corrected but Joe said

that I had better leave well enough alone since the people in Iowa where it’s

printed would probably mess it up altogether. If you catch it you’re pretty

good, but it can be argued that it is not actually a mistake.

I am mainly occupying my time by studying old opening books and believe it

or not I am learning a lot! They don’t waste space on the Catalan, Réti, King’s

Indian Reversed and other rotten openings.

Best of Luck in your real estate!

Yours truly,

/s/ Robert Fischer

9

Between that letter and the following February many details had to be worked

out. One of the primary issues that had to be addressed was what sort of fee

Bobby could command. Today, when Kasparov receives $10,000 for a simul, it’s

difficult to put Fischer’s 1964 fee of $250 per exhibition in perspective, but the

December 1964 California Chess Reporter (p. 50) does a pretty good job:

Fischer has set an unprecedented $250 fee for his exhibitions. Relatively few

years ago, the best players were lucky to get $50 for a simultaneous display.

Recently, a fee of the order of $100 was in order. Our hat is off to Bobby for

setting his fee at $250 and for making it stick!

GM Larry Evans’ father, Harry, who ran the business side of the American Chess

Quarterly, was in charge of putting together the tour. Through the pages of Chess

Life and the ACQ interested parties were given the conditions: $250 for a fifty-

board simul plus a lecture.

For the uninitiated, the latter might have seemed a throw-in but those who showed

up to hear Fischer speak were in for a real surprise. New Yorkers, of course, knew

what a fine lecturer Bobby was, but the rest of the country had never before had

the chance to see him in action.

A real natural, Bobby was a first-rate commentator who managed the almost im-

possible task of keeping beginner and master alike entertained. Without excep-

tion, of the 30-odd people I contacted who played Fischer all agreed that he was

an exceptional speaker who was both informative and entertaining, especially for

someone who was only 20-21 years old.

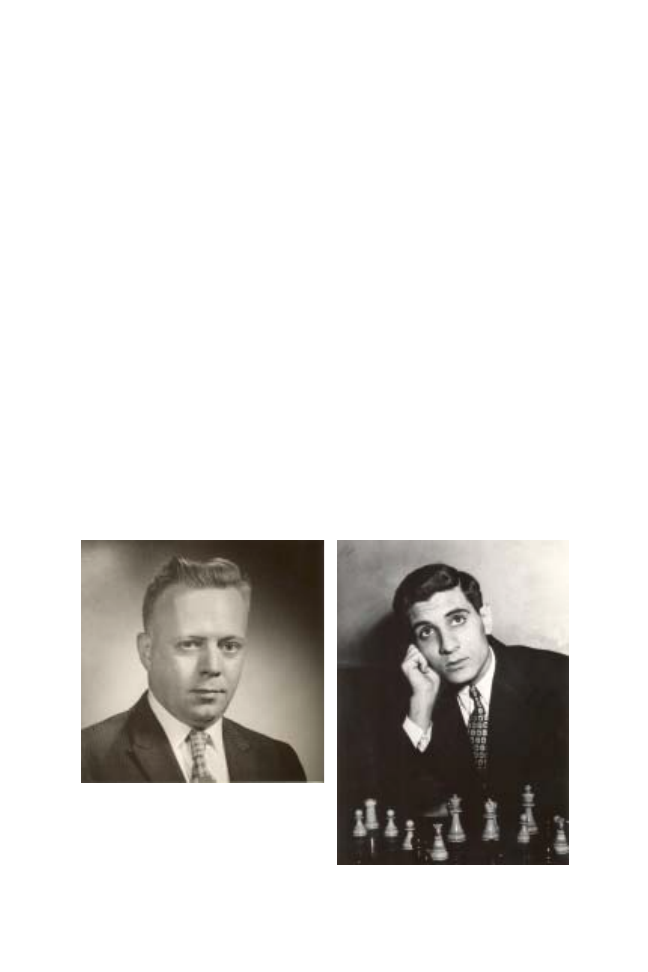

Larry Evans, at right, and his father Harry

organized the 1964 tour. Marshall Rohland,

above, (1925-1994) was USCF Secretary in

1964. He served as President in the late

1960s when the USCF experienced record

membership growth. (California Chess

Reporter)

Photo by Nancy Roos

10

Typical was the response of Lew Hucks, who heard him in Washington, D.C.:

“Bobby’s demonstration of the Botvinnik game from the Varna Olympiad in 1962

was the best demonstration of a chess game I have ever seen. He was witty and

quite entertaining. I have always believed that many of the Fischer quotes, to

which people have taken exception, would have been funny if you heard him say

them in person.”

Normally when a player goes out on tour he usually shows the same game every

evening but Bobby was different. Among the games he lectured on were: Botvinnik-

Fischer, Varna Olympiad 1962; Fischer-Tal, 1959 Candidates (the game given in

My 60 Memorable Games); Addison-Fischer, U.S. Ch. 1963-64; R. Byrne-Fischer,

U.S. Ch. 1963-64; Fischer-Geller, Bled 1961; Fischer-Benko, U.S. Ch. 1963-64;

and Fischer-Najdorf, Varna Olympiad 1964.

Every exhibitor sets his own conditions of play. Typically the master takes White

on each board but after that things vary. The practice in the distant past was that

the master’s move on a board wouldn’t be completed until he had made a move

on the next board, a nice fail-safe measure against egregious blunders, but cur-

rently considered not very sporting. The major area of difference between exhibi-

tors these days is usually in the area of passes — the question being whether they

are allowed and if so how many.

The idea that players in the simul should have the opportunity for a little extra

thinking time in critical positions would seem to be a fair one but in practice it

can be abused. More than one exhibitor has been stuck with a player who quickly

uses up his allotted passes and then conveniently “forgets” that fact.

At the beginning of the tour, in early February. it seems Bobby was quite liberal

in his policies regarding passes and consulting, but this changed. Jude Acers,

who organized Fischer’s visit to Louisiana, relates:

“A chess fan in Chicago had witnessed Fischer’s appearances and penned a harsh

criticism of Fischer to my postal box. He never dreamed where it was going … I

simply turned from the box and HANDED THE POSTCARD TO FISCHER!!

“Fischer turned crimson with surprise at the ‘slow’ Fischer play the card cited …

‘To begin with,’ said Fischer, ‘I allowed all those players unlimited passes all the

way. They could think all they wanted on the moves. And this is the appreciation

I get.’ After this Fischer allowed no passes.”

Fischer’s barnstorm generated a fair amount of publicity. Prior to the tour Bobby

had not seen much of the country, his only trips west of the Mississippi being the

1955 U.S. Junior in Lincoln, the 1956 U.S. Open in Oklahoma City, the 1957

U.S. Junior in San Francisco, and the match with Reshevsky in 1961. What im-

pression most chess players had of him could only be based on what they read

11

and journalists were not particularly kind to Fischer. The tour proved to be a bit

of a revelation for a lot of American chess players who were pleasantly surprised

when they got to meet their young champion up close.

One example is Cleveland Chess Association President Craig Henderson writing

in the April 1964 Cleveland Chess Bulletin:

“A word about Bobby Fischer. A number of articles have appeared in various

magazines criticizing him for his attitude toward tournament officials and others

with whom he has dealt. For the record, Bobby cooperated completely with all

arrangements that were made for him during his stay in Cleveland. There were no

‘incidents’ of any kind. Sometimes our own local players seem to be much more

temperamental about their chess matches.”

Another is James Schroeder in the June 1964 issue of the Ohio Chess Bulletin.

“After meeting Mr. Fischer in Cleveland and driving him to Toledo, I received

such a favorable impression of him that I organized the exhibition in Columbus.’’

Fischer had his own style of playing in exhibitions. The California Chess Re-

porter reports that he seemed to play his opponents on an individual basis, de-

feating the stronger opponents but giving big chances to the weaker ones.

A steadfast diehard of 1.e4, he played it invariably in his exhibitions with only

one exception, 1.b4. What caused him to adopt the Orangutan is a mystery that

defies an easy answer. The tour produced lots of study material for devotees of

double King Pawn openings with Fischer departing from his beloved Ruy López

to test out the white side of the Evans Gambit, Two Knights Defense, Vienna, and

King’s Gambit.

While Kasparov is clinical in his preparation before a simul with sightseeing on

the day of the event a no-no and ChessBase computer database review of the

prospective opponents games de rigueur, Fischer was more relaxed. He was in-

tense enough during the games, his 94% winning percentage over more than 2000

games one of the best results ever achieved, but he also found time to enjoy

himself. He almost always stayed at the home of the local organizer and his mode

of travel was a catch-as-catch-can with cars, trains, buses, and airplanes all being

utilized.

Despite visiting over 40 cities in his four-month tour there were a few big cities

that it seems Bobby didn’t get to. Particularly glaring by omission are St. Louis,

Kansas City, and Miami. Lack of funds seems usually to have been the chief

culprit. There are a few reports from places that were unable to arrange a visit

from Fischer. The Arizona Woodpusher for May-June of 1964 has this to say

under the headline No Fischer in Phoenix:

Club Secretary Ed Humphrey has been told by the Tours organization spon-

soring the exhibition tours of Bobby Fischer that he has a full schedule. His

12

commitments in the Southwest are such that he will not be able to include

Phoenix in his itinerary.

One wonders what Southwest cities are being referred to. Bobby gave documented

exhibitions in Houston and Los Angeles (two). Was he in Albuquerque? Did he

visit Mobile, Arizona, where his family lived for a short while before moving to

Brooklyn?

The December 1963 issue of the Georgia Chess Letter discusses the possibilities

of bringing Bobby down. Lacking a sponsor the suggestion is to have several

members band together to guarantee Fischer his $250 fee. Nothing seems to have

come of it.

Two other areas with well-developed chess communities that didn’t enjoy a visit

from Bobby were the Pacific Northwest and Minnesota. Some accounts have

Bobby giving an exhibition in Rochester, Minnesota, but that seems to be confus-

ing it with the Rochester, New York, simul. According to master Curt Brasket and

fellow Minnesotan George Tiers, Bobby was never in the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

Of course, I most certainly have missed some exhibitions. The list of cities he

visited shows some gaps, particularly for early May. The April 19, 1964, issue of

the Toledo Blade mentions that Bobby’s visit to that city on March 19 was the

21st stop on the tour. Should that be the case that means that five cities are unac-

counted for (Toledo is number 16 on our list).

Researching this tour wasn’t easy. The three national magazines Chess Review,

Chess Life, and Canadian Chess Chat gave only spotty coverage. Surprisingly

the American Chess Quarterly, which GM Larry Evans edited, Harry Evans man-

aged, and to which Bobby frequently contributed, has very little on the tour.

State and club publications (e.g. Dayton Chess News) have yielded some gems of

information but it is remarkable how few are readily available thirty years after

the fact. The bibliography gives a list of sources consulted but an equally long

one could be made of periodicals that were active in 1964 but are not in the John

G. White Collection in Cleveland. Among these are the Louisiana Chess Newslet-

ter, Rhode Island Chess Bulletin, and the Arkansas state publications. These maga-

zines might well yield much valuable material.

Newspapers, particularly in the smaller cities, were quite helpful. While Horowitz’s

column in the New York Times and Kashdan’s in the Los Angeles Times had sur-

prisingly little information, papers like the Fitchburg Sentinel had excellent cov-

erage.

But by far and away the best source of information for Fischer’s great tour was

the people who actually played him. I was very pleasantly surprised by the num-

ber of people who responded to my appeals for help and I would like to thank

them:

13

Chess Life Editor Glenn Peterson for very generously giving me permission to

use material from Chess Review and Chess Life. This proved to be an excellent

starting point. Drs. Alice Loranth and Motoko Reece of the John G. White Col-

lection of the Cleveland Public Library were extremely helpful in making their

extensive collection of state publications available.

I would especially like to thank John Blackstone and Eric Osbun for sharing their

Fischer files with me. These contained over a dozen unpublished games. Hanon

Russell was very kind in allowing me the run of his vast archives which proved

most useful in gaining some perspective on the tour.

Joe Sparks, Editor of Chess Horizons, did yeoman’s service in going through Jim

Burgess’ column in the Boston Globe. Without his efforts the exhibition in Bos-

ton would have remained a mystery and several games from Fitchburg would

have been unavailable.

Jim Warren, of APCT, came up with some rare items, the Illinois Chess Bulletin

and the bulletin of the Chicago Industrial Chess League, which proved to be real

finds yielding a large number of new games.

I would also like to thank the following individuals for taking time to help me. I

apologize if anyone has inadvertently been left out: Jude Acers, Robin Ault, D La

Pierre Ballard, Robert Barry, Alan Benson, Gary Berry, Roger Blaine, Frank Brady,

Curt Brasket, Steve Brandwein, Richard Cantwell, Bob Ciaffone, Frank Cunliffe,

Harold Dondis, Tom Dorsch, Bob Dudley, Alex Dunne, Sheila Gilmartin, Peter

Grey, Lou Hays, Elliot Hearst, Ken Hense, Mark Holgerson, Lewis Hucks, Rabbi

Steven Katz, IM Larry Kaufman, Wesley Koehler, Anthony Koppany, Barry Kraft,

Harry Lyman, Tony Mantia, Henry Meifert, Najeed Mejas, George Mirijanian,

Robert Moore, Bob Nasiff, Roger Neustaedter, Ross Nickel, Jack O’Keefe, John

Ogni, John Owen, Richard Reich, Bill Robertie, Sid Rubin, Andy Sacks, Macon

Shibut, Steve Shutt, Jeremy Silman, Chuck Singleton, Jennifer Skidmore, Joe

Sparks, Peter Tamburro, Robert Tanner, Keith Vickers, Ed Westing, Edmund

Wheeler, and Val Zemitis. This book would have been much poorer without their

help. It goes without saying that any mistakes are my responsibility.

One hope of this book is that it will inspire further research. I would be very

interested in hearing from readers with additional information on Fischer’s tour.

They can do so by writing to me c/o Inside Chess, P.O. Box 19457, Seattle, WA

98109.

This book is dedicated to Bobby Fischer, who has done so much for American

chess.

IM John Donaldson

Seattle, February 1994

February 1964

14

Detroit, February 9

+47, =2, -2

On tour, Bobby Fischer put on a simultaneous display at the Chess-Mate Gallery

in Detroit against 51 players, including several masters and numerous experts.

He won 47 games, drew two and lost only two. That he would make a showing of

this sort was no doubt expected, but the outstanding feature of the exhibition was

the extraordinary rapidity of his play, insofar as he is reported to have consumed

no more than an average of six minutes per game! (Chess Review, April 1964)

The Man Behind the Legend by William Wilcock

Since the day when Robert Fischer first appeared on the American Chess scene

he has been a controversial and misunderstood figure. A certified and authentic

chess genius, capable of being classed with the greatest. It has been Fischer’s

misfortune to appear as something less than a hero to the general public.

Reporters and magazine writers, some of whom must have read about chess for

the first time on the morning of their meeting with Fischer, have written articles

that portray Bob as (a) a colossal egotist, (b) a moody illiterate, (c) a brash, over-

bearing young man, (d) a dreamer from an ivory tower and (e) a sullen young

genius.

Dr. Howard Gaba, CCLA’s Second Vice-President, scoffs at these labels. “Rob-

ert Fischer at twenty years,” Dr. Gaba writes, “is six feet, two inches tall, lanky

but well-proportioned and well-muscled. He is pleasant in appearance with a quiet,

even-tempered manner.”

The rest of Dr. Gaba’s letter follows:

Early in February, Robert Fischer staged a tremendous chess exhibition in De-

troit. Over Sunday and Monday of that weekend we had him as our house guest.

My wife, my son Arthur, my daughter Joanne, and I felt honored to have him with

us for so many pleasant hours.

Fischer is not, as reports have it and many people seem to think, completely

wrapped up in chess. He took a great interest in Arthur’s demonstration of some

old Edison cylinder phonographs. This led to a conversation on antiquities and

relics which ended in a visit to Greenfield Village, the well-known Museum dis-

play near Detroit with its world-wide collection of historical objects.

The rest of the time at our home we watched TV, listened to the radio and record-

ings, including the Edison cylinders, talked a little, ate a little, and relaxed.

Away from the exhibition he played no chess but we did talk about the game.

Robert learned chess quite early in life but did not take it up seriously until he

February 1964

15

began to visit the chess clubs. From then on his progress was rapid.

He has a photographic mind and can play a long game through from the score

mentally, holding the main position in his mind while making side excursions

into the footnotes. He can play one game blindfolded easily but has not pushed

the development of playing multiple games sans voir though he felt it within his

power.

His development against experts and masters is well recorded and his growth,

mentally, has actually only started. At present he reads the major chess publica-

tions from all over the world and is in complete command of current master theory.

Fischer feels that he has no control over articles written about him and seems to

be becoming philosophical about the situation. The pieces in the local press seemed,

in the main, to be by writers who had not taken too much time to interview Fischer.

Fischer faced one of the strongest gatherings in Detroit in the last fifteen years. In

spite of the strong opposition and the numerous consultation games Fischer lost

only two games during the evening. He played fast and at the end of the exhibi-

tion the 200 people present seemed to realize that they had seen a great show by

a great chess player.

One incident attracted favorable attention from the spectators. A player resigned

in a position that could have been drawn, as Fischer pointed out. He then refused

the win, credited the player with the draw and signed his score sheet to that effect.

One of the strongest Michigan players is Morrie Wiedenbaum, a rated USCF

master. When I’m lucky I win from him perhaps ten percent of the time. Among

his victims at one time or another are masters Bisguier, Popel, Poschel, Burgar,

Finegold and Dreibergs.

Fischer played seven games of five-minute speed chess with Wiedenbaum, at

which the latter is very good. Fischer made a clean sweep of the games, seeming

to win them in systematic style, a pawn or so falling to him about every five

moves. In nearly every game Morrie ended up a full queen down or its equivalent.

Of his visit with us I will say only that I enjoyed it and I hope Robert did, too. We

were left with a feeling that he was an unusually alert and intelligent young man.

He is quietly but deeply religious, carrying a Bible with him on his travels and

reading it regularly.

From his speech and action you can see that he is strongly competitive in his

chess and brilliant. As his career has already been it should be more so in the

future. (The Chess Correspondent, July, 1964)

February 1964

16

(1) King’s Gambit C36

Fischer - J. Witeczek

Detroit (simul), February 9, 1964

1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3 d5 4.exd5

Nf6 5.Bb5+ c6 6.dxc6 Nxc6 7.d4

Bd6 8.O-O O-O 9.Bxc6 bxc6

10.Ne5 Bxe5 11.dxe5 Qb6+

12.Kh1 Nd5 13.Qe2 Ba6 14.c4

Qd4 15.Na3 Rfe8 16.Qf2 Qxf2

17.Rxf2 Rxe5 18.Bd2 Nb6

19.Bxf4 Re4 20.b3 Bb7 21.Rd1

a5 22.h3 Re7 23.Rfd2 f6 24.Bd6

Rd7 25.Bc5 Rad8 26.Rxd7 Rxd7

27.Rxd7 Nxd7 28.Bd6 Ne5

29.Bc7 Nd3 30.Bxa5 Nc1

31.Bd2 Nxa2 32.Kg1 Kf7

33.Kf2 Ke6 34.b4 Kd6 35.g3

Bc8 36.h4 Bf5 37.Ke3 Ke5

38.b5 cxb5 39.Nxb5 Be6 40.c5

Bd7 41.Nd4 Kd5 42.c6 Bc8

43.c7 Kc5 44.Ne2 Kb6 45.Nf4

Kxc7 46.Nh5 Bg4 47.Nxg7 Kd8

48.Kf4 Bd7 49.Nf5 Ke8 50.Nd4

Kf7 51.Ke4 Kg6 52.Kd5 Be8

53.Ke6 Bf7+ 54.Ke7 Bd5

55.Ne6 Bc4 56.Nf8+ Kg7 57.h5

Bb3 58.h6+ Kg8 59.Nd7 f5

duced material, was most instructive.

The following game is a smooth tech-

nical effort by Fischer, who occupies

the hole on d5 (c4, Nb1!, Nc3, Ncd5)

a step ahead of Black.

(2) Caro-Kann Closed B10

Fischer - J. Richburg

Detroit (simul), February 9, 1964

1.e4 c6 2.d3 d5 3.Nd2 e5 4.Ngf3

Nd7 5.g3 Ngf6 6.Bg2 g6 7.O-O

dxe4 8.dxe4 Bg7 9.Qe2 O-O

10.b3 Qc7 11.Ba3 Re8 12.Nc4

c5?!

Weakening the d5-square. See White’s

17th move.

13.Rfd1 Bf8 14.Nfd2 Rb8

15.Ne3 Nb6 16.c4 Bd7

cuuuuuuuuC

{wdwdwdkd}

{dwdNIwdp}

{wdwdwdw)}

{dwdwdpdw}

{wdwdwdwd}

{dbdwdw)w}

{ndwGwdwd}

{dwdwdwdw}

vllllllllV

60.Nf6+ Kh8 61.Kf8 Be6

62.Nd5 1-0 (Detroit News, Feb. 16,

1964)

Fischer’s exploitation of the trapped

knight on a2, in view of the greatly re-

cuuuuuuuuC

{w4wdrgkd}

{0p1bdpdp}

{whwdwhpd}

{dw0w0wdw}

{wdPdPdwd}

{GPdwHw)w}

{PdwHQ)B)}

{$wdRdwIw}

vllllllllV

17.Nb1!

Heading for d5. Fischer’s knowledge

of the structure e4 and c3 versus ...e5

and ...c5 is unparalleled. During his

career he has won many games with it

both as White (usually via the Ruy) and

Black (King’s Indian). For a recent ex-

ample of Bobby’s knack for finding the

right knight maneuver to crack the en-

emy position see the first game of his

1992 match with Spassky where Ng3-

f1-d2-b1 intending Na3 did the trick.

February 1964

17

17...Rbd8 18.Nc3 a6 19.Rac1

Bc8 20.Ncd5 Nbxd5 21.cxd5 b5

22.Bxc5! Qb8

If 22...Bxc5 White has 23.b4 recover-

ing the piece with much the better game.

23.Bxf8 Rxf8 24.Rc6 Ne8

25.Rdc1 Nd6 26.Qd2 Kg7 27.f4

f6 28.Qb2 exf4 29.gxf4 Kg8

30.e5 fxe5 31.fxe5 Nf5 32.Ng4

Kh8 33.e6+ Ng7 34.Rc7 1-0 (De-

troit News, Feb. 16, 1964)

The following game is an amusing min-

iature in which Fischer disposes of his

opponent in convincing fashion.

(3) King’s Gambit C30

Fischer - J. Jones

Detroit (simul), February 9, 1964

1.e4 e5 2.f4 f6? 3.fxe5 Nc6 4.d4

Be7 5.exf6 gxf6 6.Qh5+ Kf8

7.Bc4 Qe8 8.Bh6+ 1-0 (Detroit

News, Feb. 16, 1964)

(4) French Winawer C19

Fischer - H. Kord

Detroit (simul), February 9, 1964

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4

“I may be forced to admit that the

Winawer is sound. But I doubt it! The

defense is anti-positional and weakens

the kingside.” — Fischer, My 60 Memo-

rable Games.

4.e5 Ne7 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.bxc3 c5

7.a4 Qa5 8.Bd2 Nbc6 9.Nf3 c4!?

Conventional wisdom holds that Black

should hold off on this move and main-

tain the tension in the center, while de-

veloping with 9...Bd7. The text has had

a bad reputation since the 1940s, but is

not an easy

nut to crack.

10.Ng5

The classical way of answering 9...c4,

but 10.g3 is probably equally good.

10...h6 11.Nh3 Bd7

Black can try to cut across White’s plan

of Nh3-f4-h5 with 11...Ng6, but after

12.Be2, intending 13.Bh5, White has

the advantage.

12.Nf4 O-O-O 13.Be2

cuuuuuuuuC

{wdk4wdw4}

{0pdbhp0w}

{wdndpdw0}

{1wdp)wdw}

{Pdp)wHwd}

{dw)wdwdw}

{wdPGB)P)}

{$WdQIWdR}

vllllllllV

This move is natural, but 13.Nh5, at-

tacking g7 and restraining ...f7-f6, is

more thematic. Black might then try

13...Qc7, meeting 14.Nxg7 with

14...Nxe5. White should answer

13...Qc7 with 14.Be2 and a slight

edge.

13...f6 14.exf6 gxf615.O-O e5 16.

Nh5 Rdf8 17.Kh1 Kb8 18.Rab1

Ka8 19.Qc1 Qc7 20.Bxh6 Rf7

21.dxe5 R7h7 22.Bg7 Rxh5

23.Bxh5 Rxh5 24.Bxf6 Nxe5

25.Qf4 N7g6 26.Bxe5 Qxe5

27.Qxe5 Nxe5 28.a5 Kb8 29.h3

Kc7 30.Kg1 b5?

February 1964

18

This allows White to get rid of his weak

a-pawn. Better was 30...Nc6 31.Ra1 d4

with a complicated struggle. White has

three connected passed pawns on the

kingside, but Black’s minor pieces are

very active.

31.axb6+ axb6 32. f4 Nf7 33.Rf3

b5 34.g4 Rh8

cuuuuuuuuC

{wdwdwdw4}

{dwibdndw}

{wdwdwdwd}

{dpdpdwdw}

{wdpdw)Pd}

{dw)wdRdP}

{wdPdwdwd}

{dRdwdwIw}

vllllllllV

35.Kg2?

Asking for trouble on the diagonal.

Bobby should have played 35.Rd1 Bc6

36.Re3.

35...Bc6 36.Re1 Nd6 37.Re7+?

This check leaves both of White’s rooks

under attack. Instead, Fischer had to

play 37.Kh2.

37...Kd8 38.Ra7 d4 39.f5

The last chance to continue fighting

was 39.cxd4.

39...d3 40.cxd3 cxd3 41.Ra6 d2

42. Ra1 Bxf3+ 43.Kxf3 Rxh3+

44.Kf4 Rxc3 45.Rad1 Nc4 0-1

(O.G.)

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

090219 3404 NUI FR 160 $3 9 million spent on the road to success in?ghanistan

on the road analyse RJVDSG2WQHCLFAPZX7ACRFFGKS7U6IR26AW2BLA

On the road again Text

Kerouac On The Road

on the road TSOFF7NLA34N3UKMLKQPKT2HZVNWJIDVN6HAYXA

w drodze on the road fce wszystkie z 2013 10 06 u 406698

Lackey, Mercedes Elves on the Road 02 Diana Tregarde 02 Children of the Night

Lackey, Mercedes Elves on the Road 01 Bedlam Bard 02 Bedlam Boyz (Ellen Guon )

Richard Stevenson [Donald Strachey 02] On The Other Hand, Death (v1 0)[htm]

Richard Stevenson [Donald Strachey 02] On The Other Hand, Death (v1 0)[htm]

The Modern Scholar David S Painter Cold War On the Brink of Apocalyps, Guidebook (2005)

John Ringo The Legacy of the Aldenata 7 Watch On The Rhine

Calling On The Name Of Avalokiteshvara John Tarrant (Zen, Buddhism, Koan)

Iceland on the Ring Road 7 days

FIDE Trainers Surveys 2013 04 01, Georg Mohr Bobby Fischer and the square d5

John Barth The End of the Road

Elton John Don t Let the Sun Go Down On Me

John Ringo Alldenata 07 Watch On The Rhine

Parzuchowski, Purek ON THE DYNAMIC

więcej podobnych podstron