Online Bargaining and Interpersonal Trust

Charles E. Naquin

University of Notre Dame

Gaylen D. Paulson

University of Texas at Austin

The presented study explores the effect of interacting over the Internet on interpersonal trust when

bargaining online. Relative to face-to-face negotiations, online negotiations were characterized by (a)

lower levels of pre-negotiation trust and (b) lower levels of post-negotiation trust. The reduced levels of

pre-negotiation trust in online negotiations (i.e., before any interaction took place) demonstrate that

negotiators bring different expectations to the electronic bargaining table than to face-to-face negotia-

tions. These negative perceptions of trust were found to mediate another aspect of the relationship,

namely, desired future interaction. Those who negotiated online reported less desire for future interac-

tions with the other party. Online negotiators also were less satisfied with their outcome and less

confident in the quality of their performance, despite the absence of observable differences in economic

outcome quality.

The Internet has significantly influenced the ways in which

people communicate and exchange information both within and

between organizations (Katsh & Rifkin, 2001; Kiesler & Sproull,

1992). It has been estimated that approximately 80% of business

organizations now rely on electronic messaging (e.g., e-mail) as a

critical means of communication for everyday operations (Overly,

1999). For example, at Intel (the popular computer chip manufac-

turer) employees reportedly spend an average of 2.5 hr per day

interacting via e-mail, generating over 3 million messages per day

(Overholt, 2001). On a broad level, it is clear that with increasing

globalization and the emergence of “virtual workplaces” and rap-

idly changing economic landscapes, e-mail communication repre-

sents an indispensable business and managerial tool.

How do these changing modes of communication affect orga-

nizations and their members? Recognizing that managers spend a

good deal of their time negotiating and dealing with conflicts, it

comes as no surprise that practitioners and scholars alike have

sought to explore the ramifications of using the Internet when

crafting deals and resolving disputes (see Katsh & Rifkin, 2001;

Landry, 2000; McKersie & Fonstad, 1997; Thompson, 2001).

Conferences and workshops devoted to negotiating and resolving

disputes in the online context have been sponsored by such orga-

nizations as the Federal Trade Commission, the U.S. Department

of Commerce, and the European Union (Katsh & Rifkin, 2001).

From a more scholarly perspective, online negotiations have been

compared with traditional face-to-face interactions in such areas as

outcome quality (Barsness & Tenbrunsel, 1998; Rangaswamy &

Shell, 1997), time on task (Hiltz, Johnson, & Turoff, 1986; Kiesler

& Sproull, 1992), and the tone of the process (Sproull & Kiesler,

1991).

One common thread in the electronic communication literature

is that messages sent via e-mail are, in their current text-based

format, lacking when it comes to conveying certain types of

information (Kiesler, 1986; Trevino, Daft, & Lengel, 1990). Spe-

cifically, in the absence of nonverbal cues, e-mail users may find

it challenging (though not impossible) to send and receive affec-

tive or relational information, particularly in new relationships

(Walther, 1995; Walther & Burgoon, 1992). In e-mail negotia-

tions, these problems might become evident as negotiators attempt

to establish a working relationship and to build the trust that is

often considered necessary to create an efficient and satisfying

agreement (Carnevale & Probst, 1997; Kramer & Tyler, 1996;

Purdy, Nye, & Balakrishnan, 2000). Indeed, trust is often cited as

one of the critical hurdles to overcome in online negotiations

(Katsh & Rifkin, 2001; Keen, Ballance, Chan, & Schrump, 2000)

and in online communication in general (e.g., Duarte & Snyder,

1999; Keen et al., 2000; Overly, 1999; Rosenoer, Armstrong, &

Gates, 1999). International consulting firms such as Ernst &

Young and Deloitte & Touche now offer expert advice in the

development of trust within online settings. Academic research has

also begun to focus on ways negotiators might overcome the

challenges associated with the online context (see Moore,

Kurtzberg, Thompson, & Morris, 1999; Morris, Nadler, Kurtzberg,

& Thompson, 1999), with the goal of enabling users to reap the

benefits offered by the efficiency of the medium (i.e., overcoming

distance and time restrictions) while minimizing the potential

costs.

The present research seeks to extend the understanding of (a)

negotiations and (b) the social–psychological consequences of

interacting via the Internet by empirically examining how negoti-

ating online influences interpersonal trust. Much of the theory and

research on negotiations have focused on economic outcomes, and

only recently have studies begun to explore the more relational or

Charles E. Naquin, Mendoza College of Business, University of Notre

Dame; Gaylen D. Paulson, McCombs School of Business, University of

Texas at Austin.

Portions of this research were presented at the annual conference of the

International Association of Conflict Management, Cergy, France, June

2001. We are indebted to Michael Roloff, James Schmidtke, and Trexler

Proffitt for their assistance at various stages of this project.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Charles

E. Naquin, Mendoza College of Business, University of Notre Dame, Notre

Dame, Indiana 46556. E-mail: charles.naquin.1@nd.edu

Journal of Applied Psychology

Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.

2003, Vol. 88, No. 1, 113–120

0021-9010/03/$12.00

DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.113

113

social aspects of the negotiation process. This study provides

further insight into these latter elements, which can be critical for

long-term relationships. To do so, we first explore theory and

research regarding trust on a general level and then move to

consider variations that derive from the online environment.

Perspectives on Trust in Negotiations

In recent years, scholars have begun to give more attention to

the social and relational forces at work within negotiations (e.g.,

Kramer & Messick, 1995; Oliver, Balakrishnan, & Barry, 1994;

Thompson, 2001), with interpersonal trust often cited as a central

component to promoting cooperation and goodwill (Mayer, Davis,

& Schoorman, 1995; McAllister, 1995). Whereas its importance is

frequently noted, trust has historically proved to be an elusive

construct with multiple interpretations (Lewicki, McAllister, &

Bies, 1998).

In this article, we adopt the cross-disciplinary view of trust

provided by Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, and Camerer (1998), who

defined trust as “a psychological state comprising the intention to

accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the inten-

tions or behaviors of another” (p. 395). From this perspective, trust

becomes most poignant when there exists potential for significant

loss on the part of the one who is trusting. Any benefits of

exhibiting trust in a negotiation (e.g., cooperating) must therefore

be weighed against the potential risk for exploitation or loss

(Deutsch, 1958; Tyler & Kramer, 1996). As such, significant time

and energy may go into assessing the trustworthiness of negotia-

tion opponents. In addition, persons may also spend time and

energy toward encouraging others to place trust in them.

Scholars have long recognized that there may be many reasons

people choose to trust one another (Deutsch, 1973). Building from

work in organizational relationship development, Lewicki and

Wiethoff (2000) suggested that there are two primary routes to

trust development (see also Lewicki & Bunker, 1995, 1996; Sha-

piro, Sheppard, & Cheraskin, 1992): one that is contextually based

and another that is more relationally based. In “deterrence-based”

trust (also referred to as “calculus-based” trust), negotiators essen-

tially engage in a contextual risk analysis of sorts when determin-

ing whether to trust the other party. This analysis is typically

rooted in the extent to which one has the ability to punish or deter

the undesirable behaviors that constitute trust violations (Butler &

Cantrell, 1984; Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Rempel & Holmes,

1986; Ring & Van de Ven, 1992; Shapiro et al., 1992; Williamson,

1993). For example, if a negotiator can impact his or her oppo-

nent’s reputation or social viability, exploitation by the other party

may be perceived as less likely to occur. Trustworthy behavior,

therefore, can be reliably predicted to the extent that it represents

the most rational choice for the opponent in pursuit of his or her

own self-interest. As such, deterrence-based trust incorporates a

contextual analysis whereby negotiators assess, and perhaps ma-

nipulate, external pressures guiding behavioral choices.

The second route to establishing trust, termed “identification-

based” trust, is more relationally based and extends beyond that

which can be explained by a contextual analysis. The foundation

for this perspective is consistent with social identity theory (Tajfel,

1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1981), which emphasizes the perception of

oneness with or belongingness to another. Research in social

identity theory suggests that individuals define themselves partly

in terms of salient group memberships, such as organizational

affiliation, religion, shared interests, and so forth. Such a shared

sense of identity among negotiators may promote a deeper under-

standing of the other individual’s thoughts and actions and thereby

enhance perceived predictability. In addition, shared identity can

create a sense of empathy and concern for the outcomes of the

other. In essence, a shared sense of identity yields a more trusting

relationship (Lewicki & Wiethoff, 2000; Tyler & Kramer, 1996).

In both deterrence- and identification-based trust, negotiators

seek to eliminate or minimize levels of uncertainty. Although high

levels of trust may be hard to attain, attempting to do so from a

distance—such as over the Internet—may be especially challeng-

ing. We now turn our attention to these challenges.

Trust and the Online Environment

There is a growing stream of research examining the effects of

Internet-based communication, such as e-mail, on social interac-

tion and decision making. Because of its almost exclusive reliance

on text-based messaging, the current e-mail system constitutes a

fairly “lean” form of media, with important cues rendered unavail-

able for senders and receivers (Daft, 1984; Trevino et al., 1990).

Negotiators in these contexts must overcome significant limita-

tions not faced by those interacting in a traditional face-to-face

setting.

In particular, whereas e-mail provides an excellent means for

conveying information and task-based content, it is not optimal for

conveying relational messages. Indeed, relational information may

be most efficiently conveyed via nonverbal channels (i.e., those

not translatable into text), with verbal-based channels serving as an

uncomfortable alternative (Watzlavick, Beavin, & Jackson, 1967).

Given that judgments of trust are often viewed, at least in part, as

relational in nature (Lewicki & Bunker, 1995; Shapiro et al.,

1992), making judgments regarding trust exclusively by way of a

text-based channel may feel awkward and constrained. Though

negotiators may attempt to overcome the relational limitations of

this text-based channel (see Thompson, 2001), efforts here may be

difficult or inappropriate within certain organizational settings

(e.g., use of typed symbols to represent an emotional state, com-

monly referred to as “emoticons”). Thus, we predict that negoti-

ators who exclusively communicate over the Internet via e-mail

will be less trusting of others than those who interact face-to-face

as well.

Hypothesis 1: Negotiators who bargain online will exhibit

lower levels of trust than those who interact face-to-face.

Indeed, past research lends support to the first hypothesis re-

garding trust. Specifically, persons interacting at a distance report

lower levels of trust following a negotiation (Fortune & Brodt,

2000; Moore et al., 1999). However, much of the prior research

and theory has focused on trust as being primarily reactive, such

that the process of interacting serves as the means by which trust

differences are created. In contrast, we argue that negotiators

actually have a more proactive approach when assessing trust in

online negotiations and that it is these initial expectations (i.e.,

pre-negotiation) that may influence the relationship between par-

ties. We base this prediction on three interrelated streams of

research that, all combined, suggest that pre-negotiation percep-

114

NAQUIN AND PAULSON

tions of trust may be influenced by Internet-based communication

media.

First, the difficulties resulting from the communication channel

restriction lead to another challenge that involves the expected

ease of encoding, and expected difficulties in decoding, deceptive

messages. Although verbal inconsistencies may be an important

factor for determining the veracity of messages, people rely

heavily on visual indicators of arousal and nonverbal leakage when

assessing sincerity (e.g., Anderson, Ansfield, & DePaulo, 1999;

Ekman, 1985). Where nonverbal information is unavailable, as is

the case with text-based messages, negotiators may find it easier to

engage in exaggerations, bluffs, and outright lies (Valley, Moag, &

Bazerman, 1998). If a negotiator recognizes that his or her oppo-

nent has these sinister opportunities available, feelings of uncer-

tainty regarding the other party’s behaviors may increase and the

generation of trust may be inhibited.

In addition, it is also recognized that the potential for a broad

array of unethical and hurtful behaviors increases when a person is

removed, physically or psychologically, from the victim (Kelman

& Hamilton, 1989). Thus, whereas the potential to exploit another

individual in a face-to-face negotiation exists, such potential be-

havior may be perceived as being even greater when dealing with

a “faceless” opponent (Walther, 1995).

Finally, these uncertainties and anxieties regarding exploitation

are further aggravated by the “sinister attribution error.” As

Kramer (1994, 1995) noted, people facing diverse challenges and

stress may develop a heightened sense of paranoia. This could

make any initial concern about negotiating online an even more

salient obstacle to overcome.

Taken together, these three interrelated lines of research suggest

that negotiating online encourages the perception that opportuni-

ties are ripe for unethical behavior and, as such, the risk for being

taken advantage of is high. In essence, the online medium yields

significant pre-negotiation cause for concern and leads us to the

following prediction:

Hypothesis 2: Negotiators who bargain online will exhibit

lower levels of pre-negotiation trust (i.e., before any interac-

tion) than those who interact face-to-face.

In a similar fashion, we expected that the reduced levels of

interpersonal trust within the online context would have an influ-

ence in another relational aspect of the negotiation, specifically,

desired future interaction. In this regard, we expected that the

increased uncertainty presented in the e-mail context (as discussed

above) would result in negotiators being less satisfied with the

quality of their interpersonal relationship than those who negotiate

face-to-face. As such, we predicted that the hypothesized low

levels of trust in online negotiations would result in strained

relations such that online negotiators would have less desire to

have future interactions with the other party than those who

negotiate face-to-face.

Hypothesis 3a: Negotiators who have bargained online will

have less desire for future interaction with their opponent than

those who have interacted face-to-face.

Hypothesis 3b: The desire for future interaction will be me-

diated by perceptions of an opponent’s trustworthiness.

Method

Participants and Research Design

Participants were 134 full-time graduate-level business students who

participated in the study as part of a negotiation class assignment. The

experimental design had one manipulation: mode of communication,

wherein negotiations were conducted either exclusively over the Internet

via e-mail or face-to-face. Negotiating dyads were randomly assigned to

one of the two communication media and served as the primary unit of

analysis for our hypothesis tests. In total, 35 dyads negotiated via e-mail,

and 32 dyads interacted face-to-face.

Participants were also assigned roles and partners randomly, with the

restriction that no participant negotiate with another from the same class

section. This cross-class context not only made the need for e-mail com-

munication credible, it also ensured that participants had not completed any

previous negotiation-class simulations together. In addition, whereas in

some cases participants may have known their opponent, any potential

effects here were controlled for by the random assignment of participants

across conditions.

Procedure

Each individual was provided with a packet of material containing the

negotiation case information, confidential role instructions, and an un-

sealed envelope containing a questionnaire. In the confidential instructions,

participants in the e-mail condition were told that their negotiation was to

take place exclusively via e-mail, and they were provided with the name

and e-mail address of the other party. Similarly, in the face-to-face con-

dition, participants were instructed that the negotiation was to be done

exclusively face-to-face and were provided with the name of the other

party and a phone number by which to arrange a meeting.

Participants were informed both verbally and in the written instructions

that their goal in this negotiation was to maximize their economic outcome.

Participants were motivated to perform well on account of two sets of

reasons: Intrinsically, students indicate an enjoyment of these cases and

show enthusiasm toward achieving high-quality outcomes. Extrinsically,

course routine indicated that negotiated outcomes would be posted and

discussed during post-negotiation case debriefings. As such, the anticipa-

tion of a “public” display of individual performance relative to others

provided the incentive to perform well as a matter of competitive pride.

Participants were given either a pre- or post-negotiation questionnaire,

but not both. Those who received post-negotiation questionnaires were not

also given a pre-negotiation questionnaire because of concerns that pre-

negotiation questions might prime participants’ trust levels. Trial runs of

the experimental manipulation raised concerns and comments that the

pre-negotiation trust measure actually led participants to be less trusting of

the other party during the negotiation. Consequently, this was addressed by

having participants who completed a post-negotiation questionnaire forgo

the completion of a pre-negotiation questionnaire. In addition, because we

were working in a classroom setting and were concerned about the appear-

ance of parallel treatment, each person received only a single envelope of

material to complete. Consequently, those who received pre-negotiation

questionnaires did not receive the post-negotiation questionnaire. Pre- and

post-negotiation questionnaires were assigned randomly to dyads across

the two conditions. Thirty-three dyads received pre-negotiation question-

naires (n

⫽ 17 dyads in the e-mail condition, n ⫽ 16 dyads in the

face-to-face condition), and 34 dyads received post-negotiation question-

naires (n

⫽ 18 dyads in the e-mail condition, n ⫽ 16 dyads in the

face-to-face condition).

Those who were assigned pre-negotiation questionnaires were instructed

to open and complete the pre-negotiation questionnaire after reading the

case material and approximately 1 hr before commencing the negotiation.

They were then instructed to seal the pre-negotiation questionnaire in the

provided envelope. In a similar fashion, participants who were given a

115

ONLINE BARGAINING AND INTERPERSONAL TRUST

post-negotiation questionnaire were instructed to complete and seal the

post-negotiation questionnaire within 30 min of completing the negotia-

tion. All questionnaires were returned, along with outcome information,

after the negotiation was completed. Participants were allotted 3 weeks to

complete the negotiation, and outcomes and questionnaire material could

be turned in at any time during those 3 weeks.

Negotiation Task

The negotiation task involved two managers representing separate divi-

sions of the same company negotiating for an intra-organizational transfer

of technology (Bazerman & Brett, 1997). This simulation, “El-Tek,” in-

volves multiple issues that vary in importance for each party and, as such,

contains both fixed-sum and variable-sum elements. All outcome alterna-

tives have explicitly defined payoffs ranging from a maximum joint payoff

of $15.1 million that is distributed between the two parties (as determined

in the negotiation) to the impasse payoff in which the seller gets $5 million

and the buyer gets $0.

Dependent Variables

Pre- and post-negotiation trust.

To assess individuals’ level of trust in

their counterparts, we used the Organizational Trust Inventory—Short

Form (OTI–SF) developed and statistically validated by Cummings and

Bromiley (1996). This scale contains 12 items geared toward assessing

three dimensions of trust, including the reliability, honesty, and good faith

of the other party with respect to fulfilling their commitments. In addition,

it also assesses both an affective and a cognitive component for each

dimension. We modified the OTI–SF slightly to be more appropriate for a

dyadic negotiation setting by asking individually based questions (e.g., “I

think” rather than “We think”) and by substituting the words “the other

party” where the original questionnaire stated the name of the “other

department” or “unit.” The reliability for this measure in the present study

was acceptable, with Cronbach’s

␣ ⫽ .70. The modified OTI–SF, as was

used to measure post-negotiation trust, is presented in the Appendix. The

pre-negotiation OTI–SF that was used was equivalent to the one in the

Appendix, with the exception that it was phrased in the future tense.

Outcome quality.

Both the economic outcome and participants’ per-

ceptions of the negotiated outcome were assessed. To assess objective

outcome quality we used an economic measure of success, assessed with

dollar gains. The El-Tek simulation provides an explicitly defined payoff

schedule (included in the case material given to each participant) that

readily yields quantifiable payoffs as a function of the negotiated deal.

These outcomes were analyzed with respect to participants’ ability to

capture all available gains (i.e., integrativeness or efficiency) and also with

respect to the distribution of those gains. Integrativeness was measured

with total joint gains, represented by the sum of both parties’ outcomes. For

the distribution of gains, we analyzed the dispersion of the agreements. In

this case, higher levels of variation in one condition relative to the other

might be indicative of a greater willingness to claim gains at the other’s

expense, whereas a smaller variation might suggest a tendency toward

more “balanced” deals. We measured subjective perceptions of outcome

quality by participants’ responses to two questions. First, participants’

perceptions of the quality of their performance was assessed by responses

to the question, “How well do you think you performed in this negotiation

compared to others also playing your role? I did better than

% of the

others playing my role.” Second, participants’ overall satisfaction with the

negotiated outcome was evaluated on the basis of responses to the follow-

ing question: “How satisfied are you with the negotiated outcome?” (1

⫽

not satisfied at all, 7

⫽ very satisfied).

Desired future interaction.

From a relational perspective, we measured

participants’ willingness to have a continued relationship through re-

sponses to this question: “Based upon your experience in this negotiation

with the other side, to what degree are you willing to have future dealings

(i.e., negotiations) with them? Please give your response on a scale of 1 to

100, with 1 being not at all and 100 being without hesitation.”

Results

Our reported analyses were conducted at the dyadic level. No-

tably, the reported pattern of results was found to be equivalent

whether the analysis was conducted at an individual or a dyadic

level. However, because dependent variables were highly corre-

lated within dyads, we combined individual measures to form

dyadic measures in order to eliminate any dependency concerns

within the data (Kenny, 1995).

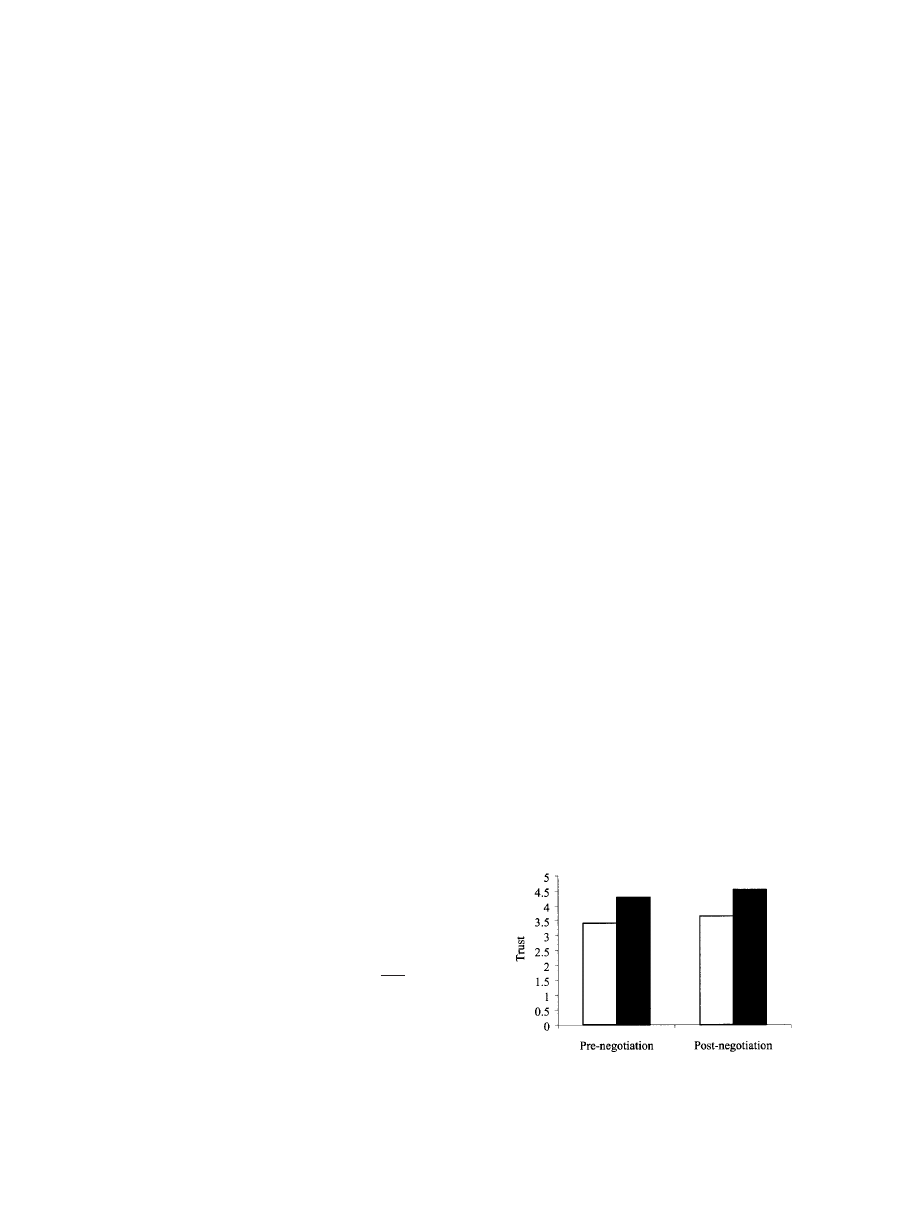

Post-negotiation trust.

Our first hypothesis examined post-

negotiation trust levels. Consistent with our prediction, and as

illustrated in Figure 1, a significant difference was observed in

post-negotiation trust levels based on our manipulation of com-

munication medium. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) on these

data indicated that participants who negotiated online via e-mail

reported significantly lower post-negotiation trust levels (M

⫽

3.66, SD

⫽ 0.28) as compared with those who communicated

exclusively face-to-face (M

⫽ 4.56, SD ⫽ 0.18), F(1, 32) ⫽

118.23, p

⬍ .01,

2

⫽ .78. The means, standard deviations, and

intercorrelations between post-negotiation variables are shown in

Table 1.

Pre-negotiation trust.

Supporting our second hypothesis re-

garding pre-negotiation trust, a significant difference in trust was

also evident for negotiators who completed pre-negotiation ques-

tionnaires. In particular, online negotiators reported significantly

lower pre-negotiation trust (M

⫽ 3.41, SD ⫽ 0.20) than did their

face-to-face counterparts (M

⫽ 4.29, SD ⫽ 0.29), F(1, 31) ⫽

100.22, p

⬍ .01,

2

⫽ .76.

Even though pre- and post-negotiation questionnaires were ad-

ministered to different groups at different times, we performed a

post hoc exploration into the magnitude of the difference between

pre- and post-negotiation measures of trust across media. When the

data were entered into a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

with the media manipulation, a main effect for time was observed

for levels of reported trust, F(1, 63)

⫽ 18.44, p ⬍ .01,

2

⫽ .23,

wherein post-negotiation trust was higher than pre-negotiation

trust for all groups. The interaction of time with the manipulation,

however, was not significant, F(1, 63)

⫽ 0.04, ns, suggesting that

improvements in trust were equivalent for e-mail and face-to-face

participants. Thus, the initial negative expectations evidenced for

e-mail negotiators did not generate a downward spiral of hostility

Figure 1.

Mean interpersonal trust as a function of communication me-

dia. Open bars represent e-mail; solid bars represent face-to-face.

116

NAQUIN AND PAULSON

in the interactions, nor was the interaction enough to overcome the

initial deficiency in trust exhibited in the pre-negotiation measure.

Desired future interaction.

In Hypothesis 3A we predicted that

participants who negotiated online would be less inclined to desire

a future relationship than those who negotiated face-to-face. This

hypothesis was confirmed. Online negotiators reported a signifi-

cantly lower interest in future relations (M

⫽ 33.28, SD ⫽ 16.92)

than did persons in the face-to-face condition (M

⫽ 46.09,

SD

⫽ 16.68), F(1, 32) ⫽ 4.92, p ⫽ .03,

2

⫽ .14.

Objective outcome quality.

Outcome quality is reported in two

ways: objective and subjective. First we report an analysis of the

objective outcomes. The objective outcomes were turned in as

regular class submissions and were available for all participants

regardless of whether they had completed the pre- or post-

negotiation questionnaire. Consequently, the reported analysis of

objective outcomes includes all participants.

With respect to impasse rate, a logistic regression analysis

revealed that no difference was observed between communication

media for impasse rate, with 6.3% of dyads in the face-to-face

condition impassing (n

⫽ 32) versus 8.6% in the e-mail condition

(n

⫽ 35),

⫽ .34, ns.

Similarly, no differences were observed for either the creation of

joint gains or the distribution of gains. Dyads in the e-mail con-

dition (M

⫽ 13.32, SD ⫽ 2.89) captured an equivalent number of

points to those in the face-to-face condition (M

⫽ 13.38,

SD

⫽ 2.61), F(1, 65) ⫽ .01, ns. To examine the balance of gains

between individuals, we used a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (see

Sheskin, 2000). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test compares two dis-

tributions to determine whether they are equal. Higher levels of

variation in one condition relative to the other might be indicative

of a greater willingness to claim gains at the other’s expense,

whereas a smaller variation might suggest a tendency toward more

“balanced” deals. Results suggested that e-mail (M

⫽ 6.65,

SD

⫽ 1.94) and face-to-face (M ⫽ 6.69, SD ⫽ 1.66) participants

had statistically equivalent variance (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z

⫽

.51, ns). In total, no differences were observed for joint gains or in

the distribution of gains as reflected in individual outcomes.

One final exploration into objective outcome quality revealed

that the economic indicators showed no connection to negotiator

trust levels. In a regression analysis neither pre-negotiation trust

(

⫽ .23, ns) nor post-negotiation trust ( ⫽ .32, ns) was predic-

tive of negotiated joint outcomes. Similarly, neither pre-

negotiation trust (

⫽ .36, ns) nor post-negotiation trust ( ⫽ .35,

ns) was predictive of individual objective outcome.

Subjective outcome quality.

In contrast to the objective out-

come data that were available for all participants, subjective per-

ceptual measures were limited to those who completed the post-

negotiation questionnaire (n

⫽ 34 dyads). Here, significant

differences were found in the subjective perceptions of outcomes.

Participants in the e-mail condition reported lower confidence in

their performance relative to others in their simulation role

(M

⫽ 0.37, SD ⫽ 0.17) than did those in the face-to-face condition

(M

⫽ 0.65, SD ⫽ 0.11), F(1, 32) ⫽ 33.97, p ⬍ .01,

2

⫽ .52.

Participants in the e-mail condition were also less satisfied with

their outcome (M

⫽ 2.97, SD ⫽ 0.63) than those in the face-to-face

condition (M

⫽ 3.91, SD ⫽ 0.95), F(1, 32) ⫽ 11.62, p ⬍ .01,

2

⫽

.27. Whereas online communication did not have a significant

effect on the objective economic nature of the outcome, it did have

a significant influence on how those outcomes were perceived.

Mediational analyses.

Analyses were conducted to determine

whether interpersonal trust mediated any of the following three

variables: relational satisfaction (per Hypothesis 3B), outcome

satisfaction, and confidence in performance. Following Baron and

Kenny’s (1986) recommended methodology for mediational anal-

ysis, we regressed the following: (a) the dependent variable on the

independent variable, that is, media; (b) the purported mediating

variable, post-negotiation trust, on the independent variable; and

(c) the dependent variable on both the independent variable and the

mediating variable. These analyses revealed that for (a) partici-

pants’ confidence in their performance and (b) their outcome

satisfaction, trust was not a significant mediator (

⫽ .08, ns;  ⫽

.02, ns, respectively). However, in support of Hypothesis 3b, trust

was found to be the mediating mechanism for the desire to work

together again in the future. Significant results were observed for

the influence of trust on desired future interaction (

⫽ .35, df ⫽

33, p

⬍ .01), and they remained even when entered with the

communication media manipulation (

⫽ .31, df ⫽ 33, p ⬍ .05).

The effect of media was concurrently reduced to nonsignificance

(

⫽ .08, ns). In summary, post-negotiation trust in a negotiation

was found to be a significant mediator for desired future interac-

tion but not for perceptions of outcome satisfaction or one’s

confidence in performance.

General Discussion

The goal of the present research was to extend our understand-

ing of (a) negotiation and (b) the social–psychological conse-

quences of interacting via the Internet by empirically examining

how negotiating online influences interpersonal trust. The reported

findings demonstrate that negotiators who bargain online may

bring different expectations to the electronic bargaining table than

when they negotiate face-to-face, resulting in a host of potential

detrimental consequences on the perceptual and relational dynam-

ics in a negotiation. For example, trust in the opposing party of a

pending negotiation was significantly lower in the online context

than in the face-to-face condition. This was before any interaction

commenced and thus was necessarily rooted in expectations rather

than in processes within the negotiation. In addition, our prediction

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations Between

Post-Negotiation Dependent Variables, Dyad Level

Variable

1

2

3

4

5

1. Trust

—

.50**

.39*

.65**

.14

2. Future interaction

—

.12

.39*

⫺.05

3. Outcome satisfaction

—

.29

.04

4. Perceived performance

—

⫺.08

5. Joint outcome

—

M

4.08

39.31

3.41

0.50

13.23

SD

0.51

17.78

0.92

0.20

3.01

Minimum

1

1

1

0

5

Maximum

7

100

7

1

15.10

Note.

The minimum and maximum values listed in the table are theoret-

ical rather than actual (they specify the most extreme possible outcomes,

not actual results).

* p

⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01.

117

ONLINE BARGAINING AND INTERPERSONAL TRUST

that the desired future interaction would be damaged in the online

context was confirmed, and this effect was mediated by trust.

Finally, although agreement rates and outcome quality measures

were parallel between online and face-to-face contexts, the levels

of confidence and outcome satisfaction were much higher in the

latter condition. These interpersonal deficiencies and perceptual

concerns suggest that persons seeking a more lasting exchange

relationship would be wise to build a base for their interactions

through some other medium (e.g., Drolet & Morris, 1995) or to

take steps to correct for initial trust problems.

These findings may appear somewhat at odds with the argu-

ments presented by Drolet and Morris (1995) in their comparisons

of telephone and face-to-face negotiators. Their results indicated a

trend toward differing expectations between media but no signif-

icant limitations therein. Instead, they argued that a lack of non-

verbal cues inhibits the development of interpersonal synchrony

necessary to build rapport, which subsequently inhibits coopera-

tion. In the online context, we recognize that the limitations of the

Internet are even more restrictive (Trevino et al., 1990) as the

nonverbal cues carried via vocal inflections and intonation (i.e.,

“vocalics”) are removed as well. Additionally, differences ob-

served in the pre-negotiation (i.e., pre-interaction) trust levels

cannot be accounted for by nonverbal behaviors. Although we do

not have data with respect to behavioral synchrony or rapport, our

findings are clearly suggestive that differences in some post-

negotiation perceptions and intentions are, at least partially, im-

pacted by differences in initial expectations.

These findings also contribute to the literature by suggesting

that the greatest problems for online negotiations may be associ-

ated with creating positive relationships and feelings rather than

with the creation of low-quality agreements. This is interesting in

that contextually based conditions (i.e., media) translated into

broad judgments of the personal characteristics of the other party.

In particular, online negotiations yielded lower levels of interper-

sonal trust that, in turn, generated negative assessments with

respect to the suitability of the other individual for future business

dealings.

Our data also showed comparable objective economic gains

between online and face-to-face negotiations but significant dif-

ferences when it came to how those outcomes were perceived.

Participants who negotiated via e-mail had lower confidence in the

quality of their deal and lower overall satisfaction with the out-

come than did those who negotiated face-to-face. These findings

regarding outcome perceptions, however, were not directly medi-

ated by trust. As such, the influence of trust on these subjective

perceptions may instead be tied more closely to differences within

the negotiation processes or in the messaging system itself (e.g.,

Morris et al., 1999).

These findings of more negative subjective perceptions of out-

comes may also help to explain why prior research has found that

online negotiators have a more difficult time reaching an agree-

ment (Moore et al., 1999). To the extent that a negotiator feels that

he or she is receiving a low-quality offer or outcome, impasse may

be viewed as the most sensible choice regardless of absolute gain

(Neale & Bazerman, 1991). In the current study no differences

were found in impasse rates between the two experimental condi-

tions: however, we recognize that the vast majority of impasses

observed in other research have arisen amongst negotiators who

were in a distinct out-group (i.e., a competing institution; Moore et

al., 1999; Morris et al., 1999). All participants in the present study

knew that although their opponent was not in the same class

section, they were students at the same university (via the e-mail

address), perhaps yielding an initial basis for identification and

comfort. Thus, competitive choices may have been minimized for

all persons in our study. Alternatively, it is possible that the length

of time required to reach an agreement in an online setting is

greater (Kiesler & Sproull, 1992) such that the ample time offered

to our participants (3 weeks) may have provided an opportunity to

arrive at a negotiated settlement. In cases in which persons are

allotted less time, the media effect on impasse may be stronger.

Unfortunately, negotiators do not always have the luxury of

choosing their communication medium in today’s organizational

landscape. There may be times when the Internet is the only

available or feasible opportunity for communication. If this is the

case, one might make a strategic effort to overcome the reported

hazards of the e-mail context while still enjoying the benefits that

the medium provides. One avenue by which to accomplish this

(building on theory and research in trust development) is through

deterrence- or identity-based approaches. For example, one may

minimize uncertainty by attempting to establish norms governing

appropriate online behaviors or by building a common sense of

identification between parties through an exchange of personal

background (i.e., chitchat). This is an area of considerable practical

importance and warrants further research.

Further research into the boundary conditions of these reported

media effects is warranted. For example, in negotiations in which

e-mail messages are knowingly archived, some forms of deception

may be problematic, thus promoting an atmosphere of trust. Hav-

ing statements “on the record” and verifiable may make factual

misrepresentation an unattractive option. However, exaggerated

demands (i.e., bluffs) might occur more readily, as the bluffer

could more easily “keep their story straight” by reviewing their

prior personal dialogue. Researchers might draw on work on the

verbal correlates of deception (e.g., Vrij, Edward, Roberts, & Bull,

2000; Zuckerman & Driver, 1985) to more carefully explore the

opportunity for, and the use of, various forms of misrepresentation

in this context.

Another noteworthy opportunity for future research is rooted in

the limitations of the current study. We speculated that the ob-

served pre-negotiation effects on interpersonal trust may influence

negotiation processes and expectations, such as norms of informa-

tion exchange, strategy selection, or the use of specific tactics (e.g.,

deception, threats). However, our insights were limited by a lack of

interaction data, and this opens the door for future investigation.

We also hold out hope for negotiations in the online context. In

the present study, prior in-class negotiation interactions between

participants were minimized. It may be the case that if negotiations

took place between colleagues with a positive history, their exist-

ing relationship could overcome the problems associated with the

online environment. In such circumstances, the initial pre-

negotiation differences observed in this study may be minimized

or eliminated, yielding more beneficial relational and outcome

perceptions.

References

Anderson, E. D., Ansfield, M. E., & DePaulo, B. M. (1999). Love’s best

habit: Deception in the context of relationships. In P. Philippot, R.

118

NAQUIN AND PAULSON

Feldman, & E. Coats (Eds.), The social context of nonverbal behavior:

Studies in emotion and social interaction (pp. 372– 409). New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable

distinction in social psychology research: Conceptual, strategic, and

statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol-

ogy, 51, 1173–1182.

Barsness, Z., & Tenbrunsel, A. (1998, August). Technologically mediated

communication and negotiation: Do relationships matter? Paper pre-

sented at the annual meeting of the International Association for Conflict

Management, College Park, MD.

Bazerman, M. H., & Brett, J. M. (1997). El-Tek negotiation case. Chicago:

Northwestern University, Dispute Resolution Research Center.

Butler, J. K., & Cantrell, R. S. (1984). A behavioral decision theory

approach to modeling dyadic trust in superiors and subordinates. Psy-

chological Reports, 55, 19 –28.

Carnevale, P. J., & Probst, T. M. (1997). Conflict on the Internet. In S.

Kiesler (Ed.), Culture of the Internet (pp. 233–255). Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Cummings, L. L., & Bromiley, P. (1996). The organizational trust inven-

tory (OTI): Development and validation. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler

(Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp.

302–330). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Daft, R. L. (1984). Information richness: A new approach to managerial

behavior and organizational design. Research in Organizational Behav-

ior, 6, 191–233.

Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2,

265–279.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

Drolet, A. L., & Morris, M. W. (1995, August). Communication media and

interpersonal trust in conflicts: The role of rapport and synchrony of

nonverbal behavior. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Acad-

emy of Management, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Duarte, D., & Snyder, N. (1999). Mastering virtual teams; Strategies,

tools, and techniques that suceed. New York: Jossey-Bass.

Ekman, P. (1985). Telling lies: Clues to deceit in the marketplace, politics,

and marriage. New York: Norton.

Fortune, A., & Brodt, S. E. (2000, August). Face to face or virtually, for

the second time around: The influence of task, past experience, and

media on trust and deception in negotiation. Paper presented at the

annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada.

Hiltz, S. R., Johnson, K., & Turoff, M. (1986). Experiments in group

decision making: Communication process and outcome in face-to-face

versus computerized conferences. Human Communication Research, 13,

225–252.

Katsh, E., & Rifkin, J. (2001). Online dispute resolution: Resolving con-

flicts in cyberspace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Keen, P., Ballance, C., Chan, S., & Schrump. S. (2000). Electronic com-

merce relationships: Trust by design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice

Hall.

Kelman, H. C., & Hamilton, V. L. (1989). Crimes of obedience. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kenny, D. A. (1995). The effect of nonindependence on significance

testing in dyadic research. Personal Relationships, 2, 67–75.

Kiesler, S. (1986, January 1). The hidden messages in computer networks.

Harvard Business Review, 64, 46 – 60.

Kiesler, S., & Sproull, L. (1992). Group decision making and communi-

cation technology. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Pro-

cesses, 52, 96 –123.

Kramer, R. M. (1994). The sinister attribution error: Paranoid cognition

and collective distrust in organizations. Motivation and Emotion, 18,

199 –230.

Kramer, R. M. (1995). Dubious battles: Heightened accountability, dys-

phoric cognition, and self-defeating bargaining behavior. In R. M.

Kramer & D. M. Messick (Eds.), Negotiation as a social process (pp.

95–120). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kramer, R. M., & Messick, D. M. (Eds.). (1995). Negotiation as a social

process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kramer, R. M., & Tyler, T. R. (1996). Trust in organizations: Frontiers of

theory and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Landry, E. M. (2000). Scrolling around the new organization: The potential

for conflict in the on-line environment. Negotiation Journal, 16, 133–

142.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1995). Trust in relationships: A model of

development and decline. In B. B. Bunker & J. Z. Rubin (Eds.), Conflict,

cooperation, and justice: Essay inspired by the work of Morton Deutsch

(pp. 133–174). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust

in work relationships. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in

organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 114 –139). Thou-

sand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust:

New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23,

438 – 458.

Lewicki, R. J., & Wiethoff, C. (2000). Trust, trust development, and trust

repair. In M. Deutsch & P. Coleman (Eds.), The handbook of conflict

resolution: Theory and practice (pp. 86 –107). San Francisco: Jossey-

Bass.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative

model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20,

709 –734.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognitive-based trust as foundations

for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management

Journal, 38, 24 –59.

McKersie, R. B., & Fonstad, N. O. (1997). Teaching negotiation theory and

skills over the Internet. Negotiation Journal, 13, 363–368.

Moore, D. A., Kurtzberg, T. R., Thompson, L. L., & Morris, M. W. (1999).

Long and short routes to success in electronically mediated negotiation:

Group affiliations and good vibrations. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes, 77, 22– 43.

Morris, M. W., Nadler, J., Kurtzberg, T. R., & Thompson, L. (1999,

August). Schmooze or lose: The effects of enriching e-mail interaction to

foster rapport in a negotiation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of

the Academy of Management, Chicago, IL.

Neale, M. A., & Bazerman, M. H. (1991). Cognition and rationality in

negotiation. New York: Free Press.

Oliver, R. M., Balakrishnan, P. V., & Barry, B. (1994). Outcome satisfac-

tion in negotiation: A test of expectancy disconfirmation. Organiza-

tional Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 60, 252–275.

Overholt, A. (2001). Intel’s got (too much) mail. Fast Company, 44,

56 – 65.

Overly, M. R. (1999). E-policy. New York: Amacom.

Purdy, J. M., Nye, P., & Balakrishnan, P. V. (2000). The impact of

communication media on negotiation outcomes. International Journal of

Conflict Management, 11, 162–187.

Rangaswamy, A., & Shell, G. R. (1997). Using computers to realize joint

gains in negotiation: Toward an “electronic bargaining table.” Manage-

ment Science, 43, 1147–1163.

Rempel, J. K., & Holmes, J. G. (1986). How do I trust thee? Psychology

Today, 20, 28 –34.

Ring, P. S., & Van de Ven, A. (1992). Structuring cooperative relationships

between organizations. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 483– 498.

Rosenoer, J., Armstrong, D., & Gates, J. R. (1999). Click with trust. New

York: Free Press.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so

119

ONLINE BARGAINING AND INTERPERSONAL TRUST

different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Man-

agement Review, 23, 393– 404.

Shapiro, D. L., Sheppard, B. H., & Cheraskin, L. (1992). Business on a

handshake. Negotiation Journal, 8, 365–377.

Sheskin, D. J. (2000). Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statis-

tical procedures (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Sproull, L., & Kiesler, S. (1991). Connections: New ways of working in the

networked organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the

social psychology of intergroup relations. London: Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1981). The social identity theory of intergroup

behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of inter-

group relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Thompson, L. (2001). The mind and heart of the negotiator (2nd ed.).

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Trevino, L. K., Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1990). Understanding

managers’ media choices: A symbolic interactionist perspective. In J.

Fulk & C. Steinfield (Eds.), Organizations and communication technol-

ogy (pp. 71–94). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Tyler, T. R., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Whither trust? In R. M. Kramer &

T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and

research (pp. 1–15). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Valley, K. L., Moag, J., & Bazerman, M. H. (1998). A matter of trust:

Effects of communication on the efficiency and distribution of out-

comes. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 34, 211–238.

Vrij, A., Edward, K., Roberts, K. P., & Bull, R. (2000). Detecting deceit via

analysis of verbal and nonverbal behavior. Journal of Nonverbal Behav-

ior, 24, 239 –263.

Walther, J. B. (1995). Relational aspects of computer-mediated communi-

cation: Experimental and longitudinal observations. Organization Sci-

ence, 6, 186 –203.

Walther, J. B., & Burgoon, J. K. (1992). Relational communication in

computer-mediated interaction. Human Communication Research, 19,

50 – 88.

Watzlavick, P., Beavin, J., & Jackson, D. D. (1967). Pragmatics of human

communication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies, and

paradoxes. New York: Norton.

Williamson, O. E. (1993). Calculativeness, trust, and economic organiza-

tion. Journal of Law and Economics, 36, 453– 486.

Zuckerman, M., & Driver, R. E. (1985). Telling lies: Verbal and nonverbal

correlates of deception. In A. W. Siegman & S. Feldstein (Eds.), Mul-

tichannel integrations of nonverbal behavior (pp. 129 –148). Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Received October 4, 2001

Revision received April 22, 2002

Accepted April 22, 2002

䡲

Appendix

Post-Negotiation Trust Questionnaire

Please circle the number to the right of each statement that most clearly describes your opinion of members of

the other party.

Strongly

disagree

Disagree

Slightly

disagree

Neither agree

nor disagree

Slightly

agree

Agree

Strongly

agree

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1

I think the other party told the truth in the

negotiation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2

I think that the other party met its

negotiated obligations.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

3

In my opinion, the other party is reliable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

4

I think that the other party succeeds by

stepping on other people.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

5

I feel that the other party tries to get the

upper hand.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

6

I think that the other party took advantage

of my problems.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

7

I feel that the other party negotiated with

me honestly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

I feel that the other party will keep its word.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

I think the other party has not misled me.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

10

I feel that the other party tries to get out of

its commitments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

11

I feel that the other party negotiated joint

expectations fairly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

12

I feel that the other party takes advantage of

people who are vulnerable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Note.

Items 4, 5, 6, 10, and 12 were reverse scored.

120

NAQUIN AND PAULSON

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Microsoft Dynamics CRM Online security and compliance planning guide

the role of interpersonal trust for enterpreneurial exchange in a trnsition economy

Decoherence, the Measurement Problem, and Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics 0312059

Dead zones of the imagination On violence, bureaucracy, and interpretive labor David GRAEBER

Guide to Online Dating and Matchmaking

Social,emotive and interpersonal meaning referat

Text and Interpretation of Philebus 56a

Before Textuality Orality and Interpretation Walter J Ong, S J

Online Tells and Giveaways

Buc, Ritual and interpretation

Introduction to Translation and Interpretation

lec6a Geometric and Brightness Image Interpolation 17

Metaphor interpretation and emergence

BarssCarnie phases and nominal interpretation

How does personality matter in marriage An examination of trait anxiety, interpersonal negativity, a

Culture, Trust, and Social Networks

Doll's House, A Interpretation and Analysis of Ibsen's Pla

Interpretation of canine and feline cytology (by crexcrex) vet med

więcej podobnych podstron