Skin diseases in the alpaca (Vicugna pacos): a literature

review and retrospective analysis of 68 cases (Cornell

University 1997–2006)

Danny W. Scott*

,†

, Jeff W. Vogel*, Rebekah I.

Fleis

†

, William H. Miller Jr*

,†

and Mary C. Smith

‡

*Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine,

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

†

Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary

Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA

‡

Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Services,

College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853,

USA

Correspondence: Danny W. Scott, Department of Clinical Sciences,

College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853,

USA. E-mail: shb3@cornell.edu

Sources of Funding

This study is self-funded.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Abstract

This retrospective study describes 68 alpacas with

skin diseases investigated from 1997 through 2006 at

Cornell University. During this time period, 40 of 715

(5.6%) alpacas presented to the university hospital

had dermatological diseases. In addition, skin-biopsy

specimens accounted for 86 of 353 (24.4%) of alpaca

biopsy specimens submitted to the diagnostic labo-

ratory, and of these 86 specimens, follow-up was

available for 28 cases. The following diseases were

most common: bacterial infections (22%); neoplasms,

cysts and hamartomas (19%); presumed immuno-

logical disorders (12%); and ectoparasitisms (10%).

Conditions described for the first time included

intertrigo, collagen and hair follicle hamartomas,

lymphoma, hybrid follicular cysts, melanocytoma,

anagen

defluxion,

telogen

defluxion,

presumed

insect-bite hypersensitivity, ichthyosis, and possible

hereditary bilateral aural haematomas and chondri-

tis. The results of the retrospective study are com-

pared and contrasted with the results of a literature

review.

Accepted 22 May 2010

Introduction

Alpacas (Vicugna pacos, formerly Lama pacos) are grow-

ing in popularity and are increasingly being presented for

veterinary care and often present with skin disorders that

provide diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for the

practicing veterinarian.

1–4

Reviews exclusively devoted to

alpaca skin conditions are not available in the literature.

Clinicians have to rely upon literature for the llama,

5,6

or extrapolations from mixed camelid reviews,

2,4,7–9

or

information from scattered case reports.

A postal survey was conducted in the UK between

2000 and 2001 by D’Alterio et al.

10

This survey indicated

that the percentage of alpaca ownership was increasing.

In 1993, alpacas accounted for 21% of the camelid popu-

lation, whereas in 1998 they accounted for 77% of the

camelid population. In the same survey, 51.1% (111 of

217) of respondents indicated that skin diseases were

seen at one time or another, and that up to 9% of all ani-

mals could be affected at a given time. Most respondents

reported that skin conditions were more prevalent in

summer, and that most affected animals were nonwhite

coloured.

The most common skin lesions reported in the UK

survey were alopecia, crusts, scales and pruritus. The

most commonly affected body sites were the nose, ears,

periorbital region, medial thighs, axillae, dorsum and

abdomen. The most common dermatological diagnoses

rendered by attending veterinarians, as reported by the

owners, were zinc-responsive dermatitis (23%), ectopar-

asitism (19%), fungal infection (3%), bacterial infection

(3%), allergy (3%), dermatophilosis (2%) and contagious

viral pustular dermatitis (‘orf’; 1%). This information must

be carefully interpreted, as it is not known how the diag-

noses were established.

The UK survey also indicated that many alpacas were

housed on farms with other domestic species, as follows:

horses and ponies, 66.7%; sheep, 55.9%; goats, 22.6%;

and cattle, 19%. This has obvious implications for the

infectious and ectoparasitic diseases that can affect

those domestic species and alpacas. It is not known if

similar percentages of commingling of species occur in

the USA, but the practice is undoubtedly common.

In this paper we firstly review the literature (predomi-

nantly English language) on alpaca skin conditions, sec-

ondly present the results of a retrospective study of

dermatological disorders in alpacas examined at the

Cornell University Hospital for Animals (CUHA), and

thirdly present the results of a retrospective study of

alpaca skin-biopsy specimens submitted to the Animal

Health Diagnostic Center (AHDC) at Cornell University.

Materials and methods

From January 1997 through December 2006 (10 years), 715 alpacas

were patients at the CUHA, and 40 of these (5.6%) had dermatologi-

cal diseases (Table 1). Follow-up information was available for 33

2

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2010.00918.x

(82%) of these patients. The number of alpaca patients per year

increased from 18 in 1997 to 240 in 2006. The female:male ratios of

the total alpaca patient population and the dermatology cases were

3:1 and 4:1, respectively. During the same time period, 86 skin-

biopsy specimens from alpacas were submitted to the AHDC. Fol-

low-up information was available for 28 (33%) of these alpacas

(Table 1). Skin-biopsy specimens accounted for 24.4% (86 of 353)

alpaca biopsy specimens submitted during the study period.

Case results and literature review

Bacterial diseases

Bacterial infections (including dermatophilosis) accounted

for only 5% of the cutaneous diagnoses made in alpacas

by veterinarians in the UK postal survey.

10

However, bac-

terial infections were documented and

⁄ or diagnosed (by

cytological examination and response to antibacterial

therapy) in 22% of the alpacas in our retrospective study.

In general, there are no systemic antibiotics approved

for use in alpacas. Off-label antibiotics that are commonly

useful for treating skin diseases in alpacas include the fol-

lowing:

1

(i) procaine penicillin at 20 000–40 000 IU

⁄ kg,

twice daily, subcutaneously (s.c.) or intramuscularly (i.m.);

(ii) ceftiofur at 2.2 mg

⁄ kg, twice daily, s.c., i.m. or intra-

venously (i.v.); (iii) oxytetracycline at 20 mg

⁄ kg every

3 days, s.c. or i.m.; or (iv) enrofloxacin at 10 mg

⁄ kg, once

daily, per os (p.o.). The subcutaneous space of alpaca

skin is inelastic and small, and no more than 10 mL of

solution should be injected into a single site; the fold

of skin in the axilla or just cranial to the shoulder is

recommended.

2

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infections appear

to be common in alpacas.

2,11–13

Infection may occur by

wound contamination or by consuming infected milk.

13

Affected animals range from 22 days to 14 months of

age.

Lesions are solitary or multiple subcutaneous nodules

or abscesses. The head, submandibular and ventral cervi-

cal regions are most commonly affected. Early lesions are

characterized by pyogranulomatous inflammation with

central caseous necrosis (nodule), while older lesions are

characterized by liquefactive necrosis and peripheral fibro-

sis (abscess).

13

Diagnosis is confirmed by culture.

Traditional treatment consists of surgical drainage,

flushing and systemic antibiotics.

11

However, en bloc

excision may be the best way to control local infections,

as abscesses may recur following traditional treatment.

11

Furthermore, spontaneous or surgical drainage potentially

contaminates the environment.

11

Corynebacterium pseu-

dotuberculosis is considered a zoonotic risk; however,

C. pseudotuberculosis infection was not documented in

this retrospective study.

Tooth root abscesses

Tooth root abscesses present as firm mandibular swell-

ings, with or without draining tracts.

14,15

Mandibular teeth

are more commonly involved than maxillary teeth, and

molars and premolars are more commonly affected than

incisors. The median age at presentation is 5 years,

which correlates with the eruption of permanent teeth.

15

It has been postulated that infection occurs when the

deciduous caps are loose but the permanent teeth are

not fully mature, thus allowing for trauma from roughage

during mastication.

15

Actinomyces spp. and unidentified anaerobes were the

most common isolates in one large study.

15

Radiography

is recommended to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate

the extent of osteolysis.

15

Treatment usually includes combined tooth extraction

and systemic antibiotics.

14,15

The two most successful

antibiotic regimens (in combination with tooth extraction)

were ceftiofur at 2.2 mg

⁄ kg once or twice daily, i.v. or

s.c., for a mean duration of 11.4 ± 5.5 days, or procaine

penicillin at 20 000–40 000 IU

⁄ kg once or twice daily,

i.m., for a mean duration of 12.9 ± 7.2 days.

15

We diagnosed a tooth root abscess in a 4-year-old

female alpaca with an abscess below the left eye

(Table 1, case 18). The animal also had symmetrical,

3–4 mm diameter, punched-out ulcers, crusts, scaling

and hair loss that followed blood vessels at the pinnal

margins as well as linear, healing areas of alopecia, and

scaling on the convex surface of the pinnal mid-line. The

pinnal lesions had appeared a few weeks after the

abscess had been noted and were neither pruritic nor

painful. Biopsies were not performed, and a presumptive

diagnosis of pinnal vasculitis, possibly secondary to the

tooth root abscess, was made. The animal was treated

with maxillary tooth extraction and ceftiofur, and both the

abscess and the presumed pinnal vasculitis resolved.

Dermatophilosis

Anecdotal reports indicate that dermatophilosis occurs in

alpacas.

2,4,7,8,10

The disease is said to occur most fre-

quently in hot, humid regions of the USA, and frequently

to present as thick crusts on the pinnae.

8

Although we

see dermatophilosis in horses, cattle and goats in our

practice area, we documented no cases in our retrospec-

tive study.

Bacterial folliculitis

Anecdotal reports indicate that bacterial (staphylococcal)

folliculitis occurs in alpacas.

2,4,8

We diagnosed bacterial

folliculitis in 13 alpacas in our retrospective study. In ten

animals, the folliculitis was idiopathic (cases 9–15 and

45–47), and in three animals it was associated with pre-

sumed insect-bite hypersensitivity (cases 29 and 31) or

contact dermatitis (case 44). Lesions consisted of ery-

thematous papules, pustules, brown-to-yellow crusts,

epidermal collarettes, and annular areas of alopecia and

scaling (Figure 1). The muzzle, back, ventrum and distal

hindlegs were most commonly affected. Pruritus was

only reported in the three alpacas with concurrent pre-

sumed insect-bite hypersensitivity or contact dermatitis.

Skin scrapings and trichography were negative for para-

sites and fungi. Cytological examination revealed degen-

erate and nondegenerate neutrophils and phagocytosed

cocci. Cultures were not performed. Histological exami-

nation of biopsy specimens confirmed suppurative lumi-

nal folliculitis in six animals (cases 11–13 and 45–47;

Figure 2). Eosinophils were rarely seen. Follow-up infor-

mation was available for eight treated animals, as follows:

two (cases 9 and 13) were cured with the topical applica-

tion of povidone-iodine; and six (cases 11, 12, 29 and

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

3

Skin diseases in the alpaca

Table 1. Data on 68 alpacas with dermatological disease (Cornell University 1997–2006)*

Case

Age (years)

Sex

Diagnosis(es)

Follow-up

period (months)

1

1

F

Bite wounds

24

2

1

F

Bite wounds

Died

3

1

F

Bite wounds

12

4

8

M

Bite wounds

Died

5

0.8

F

Bite wounds

Died

6

1.5

F

Bite wounds

Died

7

1

F

Bite wounds

12

8

0.7

F

Bite wounds

Died

9

Adult

F

Bacterial folliculitis

12

10

Adult

F

Bacterial folliculitis

0

11

7

F

Bacterial folliculitis

12

12

1.5

M

Bacterial folliculitis

20

13

Adult

F

Bacterial folliculitis

6

14

3

F

Bacterial folliculitis

0

15

3

F

Bacterial folliculitis

0

16

3

F

Bacterial intertrigo

24

17

7

F

Bacterial intertrigo

0

18

4

F

Tooth root abscess, pinnal vasculitis

†

12

19

4

F

Zinc-responsive dermatitis

12

20

3

F

Zinc-responsive dermatitis

12

21

3

F

Zinc-responsive dermatitis

6

22

4

F

Zinc-responsive dermatitis

12

23

1.5

M

Zinc-responsive dermatitis

12

24

0.8

F

Chorioptic mange

Euthanized

25

5.5

F

Chorioptic mange

0

26

5

M

Chorioptic mange

18

27

7

F

Psoroptic mange

†

12

28

0.8

M

Psoroptic mange

†

12

29

11

F

Insect-bite hypersensitivity

†

, bacterial folliculitis

24

30

1

M

Insect-bite hypersensitivity

†

24

31

1

M

Insect-bite hypersensitivity

†

, bacterial folliculitis

0

32

8

F

Insect-bite hypersensitivity

†

12

33

0.8

F

Contagious viral pustular dermatitis

Died

34

0.1

F

Anagen defluxion

6

35

Adult

F

Telogen defluxion

0

36

0.3

F

Ichthyosis

Euthanized

37

1

M

Sterile eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculosis

24

38

5

M

Adverse cutaneous drug reaction

†

12

39

8

F

Hair follicle hamartomas

12

40

5

F

Hair follicle hamartomas

12

41

6

F

Viral papillomas

6

42

4

M

Viral fibropapillomas

12

43

Adult

F

Dermatophytosis

9

44

Adult

M

Contact dermatitis

†

, bacterial folliculitis

18

45

2

F

Bacterial folliculitis

12

46

3

M

Bacterial folliculitis, abscess

6

47

0.7

M

Bacterial folliculitis, pyogranuloma

12

48

2

F

Psoroptic mange

6

49

Adult

F

Chorioptic mange

†

24

50

2

F

Idiopathic urticaria

72

51

5

F

Insect-bite hypersensitivity

†

Killed

52

4

F

Ichthyosis

24

53

1.5

M

Ichthyosis

Euthanized

54

3

F

Hybrid follicular cysts

6

55

2

M

Hybrid follicular cysts

24

56

Adult

M

Hybrid follicular cysts

24

57

11

F

Fibroma

24

58

Adult

F

Fibroma

36

59

6

F

Melanocytoma

48

60

14

M

Trichoepithelioma

24

61

1.5

F

Lymphoma

Euthanized

62

0.1

F

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis

36

63

0.1

M

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis

24

64

0.3

F

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis

36

65

0.2

F

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis

36

66

0.3

M

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis

24

67

0.1

F

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis

24

68

3

M

Collagenous hamartomas

12

*Cases 1–40 were patients at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals. Cases 41–68 had skin-biopsy specimens submitted to the Animal Health Diagnos-

tic Center at Cornell University.

†

Presumptive diagnosis.

F, female; M, male.

4

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

Scott et al.

45–47) were cured after the systemic administration of

ceftiofur for 10–21 days.

Intertrigo

Intertrigo (skin-fold dermatitis) is a frictional dermatitis

that occurs where two skin surfaces are intimately

apposed. We diagnosed intertrigo with secondary bacte-

rial infection in two alpacas (cases 16 and 17). In both

cases, cytological examination revealed pus and phagocy-

tosed cocci. The intertrigo and secondary infection were

perivulvar in case 17. In case 16, a hernia developed

in the left ventral flank area post-Caesarean section. The

intertrigo and bacterial infection developed in the apposed

skin of the left inguinal region and medial aspect of the

left thigh. The animal was cured after surgical repair of

the hernia and a course of systemic ceftiofur.

Miscellaneous bacterial infections

Bacterial

pseudomycetoma

(‘botryomycosis’)

was

reported in one alpaca in the USA.

8

The animal had multi-

ple abscesses and granulomas, 0.5–4 cm diameter, on

the medial thigh. Diagnosis was confirmed by histological

examination and culture (Staphylococcus aureus). Sur-

gery followed by 4 weeks of broad-spectrum antibiotic

therapy was reported to be successful. Further details

were not given.

Mycobacterium ulcerans was identified (by culture and

polymerase chain reaction) in a large ulcer on a leg of an

alpaca in southeastern Australia.

16

No details were given.

Cutaneous infection with Actinobacillus lignieresi was

reported in an alpaca in the UK.

2

No details were given.

Fungal diseases

Anecdotal reports indicate that dermatophytosis occurs in

alpacas.

2,4,7–10

Fungal infection accounted for 3% of the

dermatological diagnoses made by attending veterinari-

ans in the UK postal survey.

10

We documented only one

case of dermatophytosis in our retrospective study (1.5%

of the cases). An adult female alpaca (case 43) developed

an alopecic, crusted, hyperkeratotic area on the upper lip.

Histological examination revealed a suppurative luminal

folliculitis, with fungal hyphae and arthroconidia within fol-

licular keratin, but not within hair shafts (Figure 3). Fungal

culture was not performed. The condition was treated

with topical clotrimazole, twice daily, and resolved in

2 weeks.

Viral diseases

Contagious viral pustular dermatitis (‘orf’ or ‘contagious

ecthmya’) is a parapoxvirus infection that has been

reported in alpacas.

2,4,7–10,17

Affected animals are typi-

cally 2–4 months old. Thick crusts are present on the lips

and nostrils. Infected nursing cria may transmit the

disease to the teats of the dam. The disease is a zoonotic

risk. The condition is typically self-limiting, although one

author mentions that a chronic form lasting ‘months’ can

be seen.

8

Diagnosis is confirmed by viral isolation and

viral antigen detection techniques.

We diagnosed presumptive contagious viral pustular

dermatitis in a 9-month-old alpaca that died shortly after

being admitted to the CUHA (case 33). Thick crusts, ooz-

ing and ulceration were present on the nostrils, upper and

lower lips. Necropsy examination revealed pericardial

effusion and hepatic lipidosis. Histological examination of

skin specimens revealed ballooning degeneration of

epidermal keratinocytes and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic

inclusion bodies consistent with parapox infection.

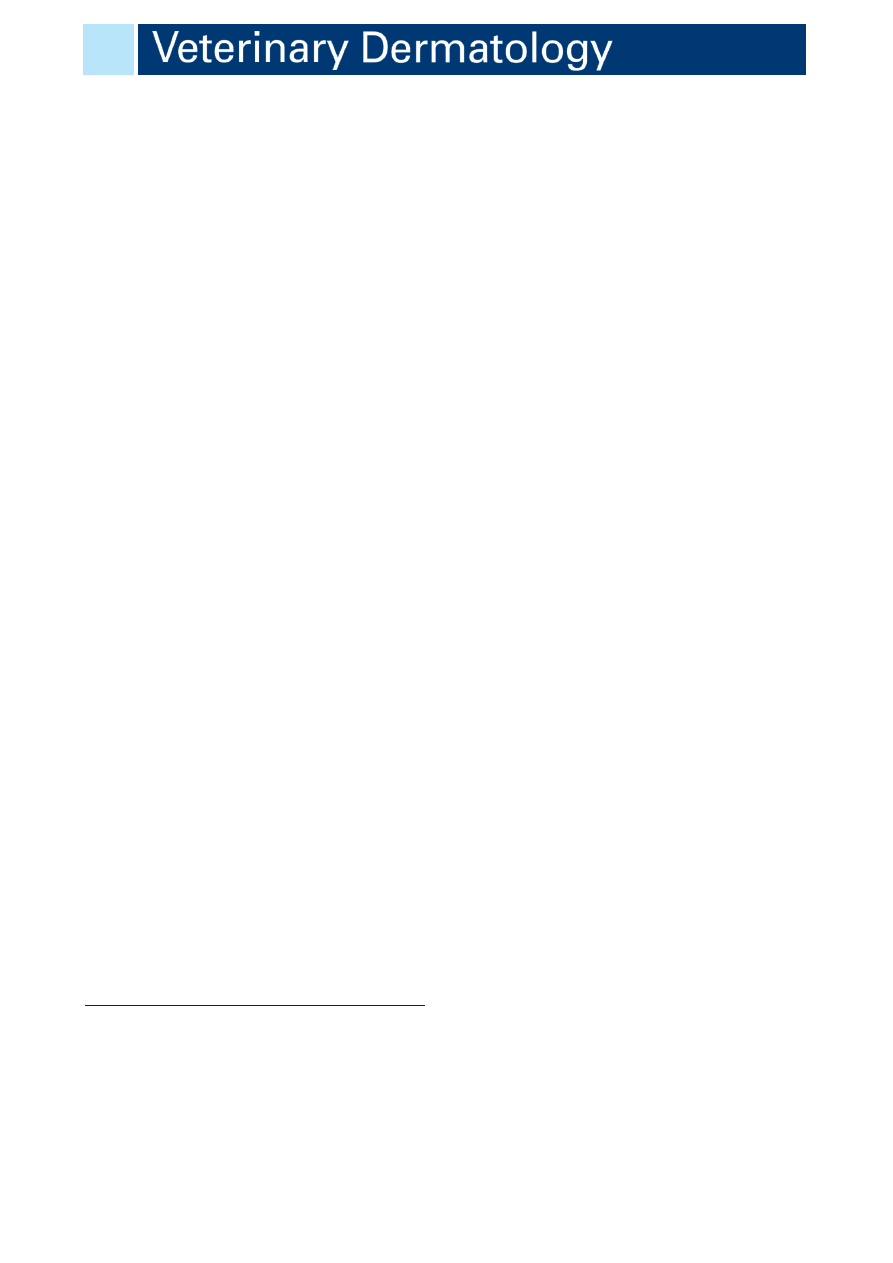

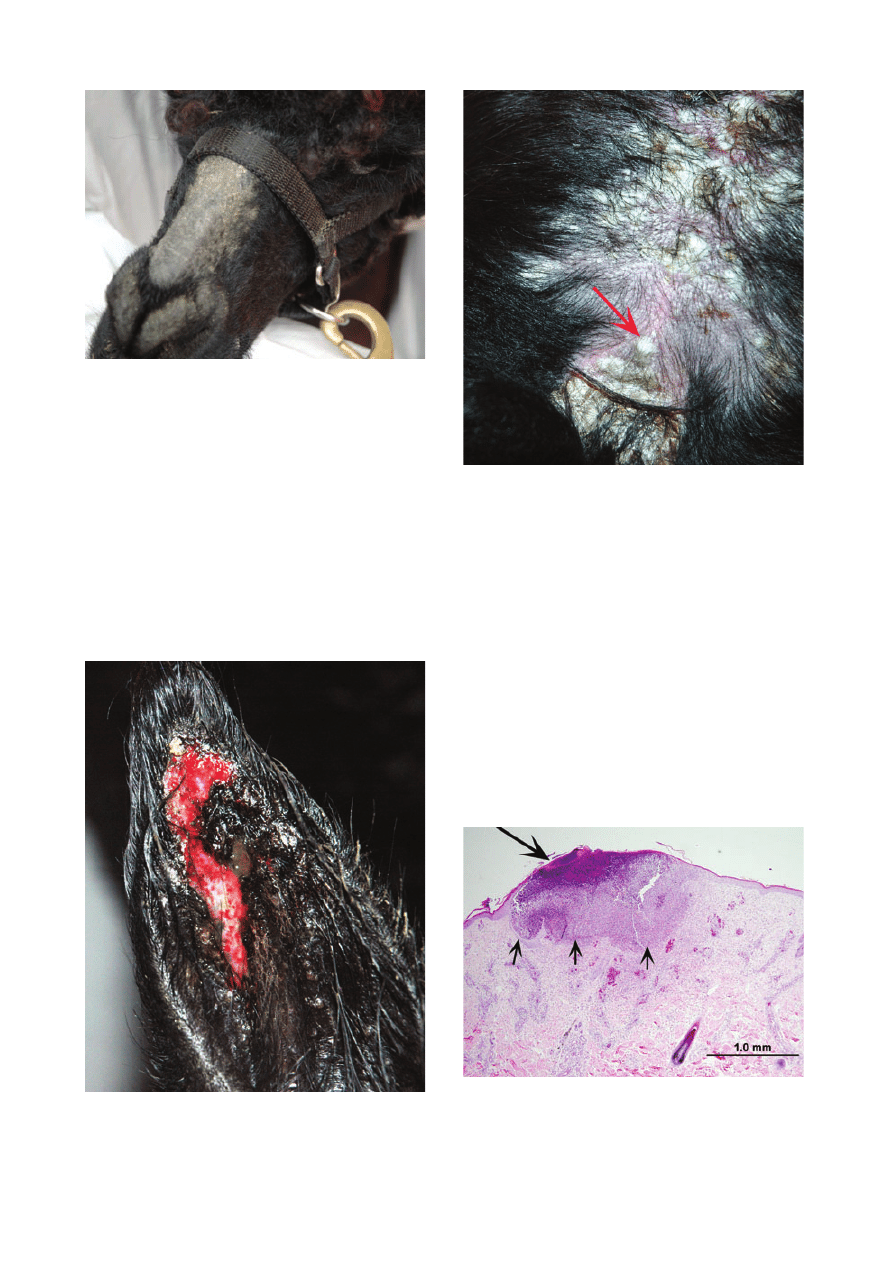

Figure 1. Ventral abdominal area of an alpaca with bacterial folliculi-

tis. Note erythematous papules, pustules and crusts.

Figure 2. Photomicrograph of skin-biopsy specimen from an alpaca

with bacterial folliculitis. Note luminal suppurative folliculitis (arrow).

Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 200 lm.

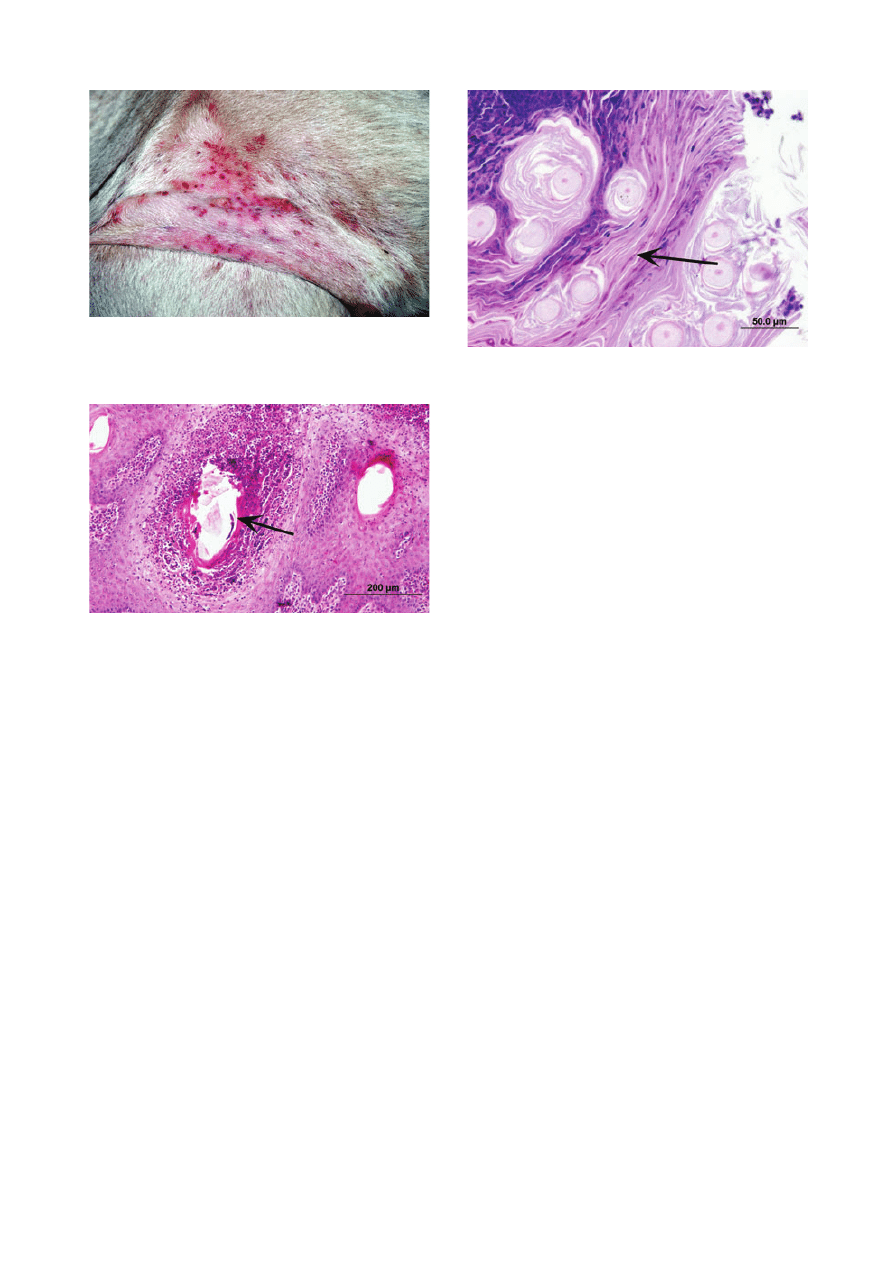

Figure 3. Photomicrograph of skin-biopsy specimen from an alpaca

with dermatophytosis. Dermatophyte hyphae are present in the kera-

tin surrounding hair shafts (arrow). Periodic acid–Schiff; scale

bar = 50 lm.

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

5

Skin diseases in the alpaca

Specific viral isolation and identification techniques were

not performed.

Ectoparasitic diseases

By far the most commonly reported skin diseases of

alpacas are caused by ectoparasites, especially mange

mites and lice.

2,4,8,10

Ectoparasitism accounted for 19%

of the dermatological diagnoses rendered by attending

veterinarians in the UK postal survey.

10

Ectoparasitism

accounted for 10% of the cases in our retrospective

study. Alpacas develop sarcoptic mange, psoroptic

mange and chorioptic mange; and all three mites have

been reported to simultaneously infect the same

animals.

18

In general, there are no ectoparasiticides approved for

use in alpacas. In addition, pharmacokinetic studies of

macrocyclic lactones (avermectins) in New World came-

lids are limited, and most have been conducted in

llamas.

19–22

These studies suggest that the absorption of

these compounds, irrespective of the route of administra-

tion, is somewhat lower than that in cattle and sheep.

Thus, higher doses (e.g. 0.4 mg

⁄ kg ivermectin, every

7 days, s.c.) may be necessary in alpacas.

2

Sterile

abscesses may be seen with the s.c. administration of

ivermectin, and inconspicuous injection sites (such as the

axilla) have been recommended.

1,2

It is common to inject

ivermectin s.c. in the neck just cranial to the shoulder

(much easier to do here; fibre coat makes any resulting

lumps inconspicuous).

An additional consideration is that alpaca fibre does not

contain lanolin, so that topical applications of insecticides

and acaricides used on other ruminants may not be as

effective in alpacas.

2

Sarcoptic mange

Sarcoptic mange is caused by Sarcoptes scabiei var.

auchinae. It has been reported from many countries in

the world, and is a significant cause of weight loss and

decreased

fibre

production.

2,4,8,10,18,23–30

Sarcoptic

mange has been reported to be responsible for up to

95% of the economic losses caused by ectoparasites in

alpacas, with up to 40% of alpacas being infested.

Alpacas with sarcoptic mange present with alopecia

and usually severe pruritus.

2,4,8,10,18,30

Early skin lesions

consist of erythema, papules and yellow-to-grey crusts.

Chronic changes include marked skin thickening, lichenifi-

cation and hyperpigmentation. The disease often begins

on the ventral abdomen and chest, axillae and groin, with

gradual extension to the medial thighs, prepuce, peri-

neum, legs, interdigital spaces, face and pinnae. Second-

ary bacterial infection can complicate the condition.

8

Sarcoptic mange in alpacas is a potential zoonosis.

2,4,8

Diagnosis of sarcoptic mange is confirmed by finding

mites in skin scrapings; however, negative skin scrapings

do not rule out the disease.

2,4

Histopathological findings

include a superficial eosinophilic interstitial dermatitis,

marked parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, and mites in the

surface keratin and crusts.

28

Ivermectin (0.2–0.4 mg

⁄ kg, every 7–14 days, s.c., for

two to four injections) has been reported to be an effec-

tive treatment.

2,4,18,27

It has been suggested that sarcop-

tic mange is rare in the USA because of the use of

ivermectin for routine deworming.

4–6

However, there

have been reports of treatment failures with ivermec-

tin,

2,29,30

as well as doramectin,

29,30

eprinomectin,

30

amitraz

29

and diazinon.

29

We diagnosed no cases of sarc-

optic mange in our retrospective study.

Psoroptic mange

Psoroptic mange is caused by a psoroptic mite previously

referred to as Psoroptes communis var. auchinae, P. au-

chinae, P. cuniculi and P. ovis.

31,32

In fact, the species of

Psoroptes mite that infests alpacas has not been officially

named, and recent authors use the name Psoroptes sp.

2

Alpacas with psoroptic mange most commonly present

with dermatitis on the head, face and pinnae.

2,4,8,10,18,31–33

In some individuals, only the ear canals are affected, and

the animals present for ear twitching, head shaking, large

dry flakes in the ear canals and occasional purulent dis-

charge due to secondary bacterial infection.

8,32

Skin

lesions include papules, crusts, exudation, alopecia and

pruritus. A more widespread distribution of lesions may

be seen: shoulders, back, rump, sides and perineum.

2,8,32

Psoroptic mange does not constitute a zoonotic risk.

Diagnosis is confirmed by finding mites in skin scrap-

ings. Ivermectin, as described previously for sarcoptic

mange, is usually effective for treatment.

2,4,18,31

We diagnosed psoroptic mange (positive skin scrap-

ings) in one alpaca (case 48) and suspected it in two others

(cases 27 and 28). All animals had crusts, scales, alopecia

and pruritus involving the pinnae and face. Skin scrapings

were negative in two cases, but cytological examination

revealed eosinophilic inflammation. Biopsy specimens

from two animals (cases 27 and 48) revealed superficial

and deep eosinophilic interstitial dermatitis with marked

parakeratotic hyperkeratosis. Mites were seen in surface

crust in one case (case 48). All three alpacas were cured

after a course of s.c. ivermectin injections.

Chorioptic mange

Chorioptic mange is caused by Chorioptes bovis. It has

been reported from many countries in the world, and

appears to be the most common mite infestation of alpa-

cas.

2,4,18,32,34–40

Alpacas with chorioptic mange often initially present

with scale, crusts and alopecia on the ventral tail, perineal

region, ventral abdomen and medial thighs.

2,8,32

Lesions

then spread to the axillae, tips and lateral surface of the

pinnae, interdigital spaces and distal limbs up to the fet-

locks. In some outbreaks, lesions are more commonly

seen on the pinnae, face, neck, dorsum and feet.

4,37,39,40

In severe cases, erosions, ulcers and lichenification can

be seen. Pruritus is usually absent or mild. Chorioptic

mange does not constitute a zoonotic risk.

Diagnosis is confirmed by finding mites in skin scrap-

ings. In a study on the prevalence of Chorioptes bovis

infestation in alpacas in the UK,

39

skin scrapings were

positive in 55% of the clinically normal in-contact animals,

but positive in only 28% of the animals with skin lesions.

Clinically normal, skin-scrape-positive alpacas tended to

be younger (<24 months old), whereas alpacas with skin

lesions tended to be older. It is not clear whether or not

all of the alpacas with skin lesions in the UK study had

chorioptic mange. However, other investigators have also

6

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

Scott et al.

indicated that heavily infested alpacas can be clinically

normal, and alpacas with extensive lesions can have

low numbers of mites.

4,36,40

Skin scrapings from the

axilla and interdigital space are the most commonly posi-

tive.

4,39

Histological examination of skin-biopsy speci-

mens is reported to reveal eosinophilic perivascular

dermatitis and eosinophilic epidermal microabscesses

and pustules.

37

Chorioptic mange in alpacas is a therapeutic challenge.

Repeated s.c. injections of ivermectin (0.2–0.4 mg

⁄ kg)

reduce mite numbers and lesion severity, but do not erad-

icate mites and any associated dermatitis.

2,18,37,38

Similar

results were obtained with repeated topical applications

of eprinomectin (0.5 mg

⁄ kg).

38,40

Anecdotal reports sug-

gest that topical applications of fipronil may be effective.

2

We diagnosed chorioptic mange in three alpacas (cases

24–26) in our retrospective study and suspected it in one

other (case 49). All four animals had nonpruritic crusts,

scales and alopecia on the tail, perineum, hindlegs and

hindfeet (Figure 4). Two animals additionally had lesions

on the axillae and front feet. One animal also had lesions

on the pinnae. Skin scrapings were positive, and biopsy

specimens revealed eosinophilic interstitial dermatitis in

three alpacas (cases 24, 26 and 49). Mites were present

in surface crusts in case 24 (Figure 5). One animal (case

24) was euthanized due to endometritis. Two animals

(cases 26 and 49) were successfully treated with weekly

topical applications of 2% lime sulfur for 6–8 weeks.

Pediculosis

Pediculosis in alpacas is caused by two species of lice:

the chewing louse Bovicola (Lepikentron) breviceps and

the sucking louse Microthoracius mazzi (praelongiceps).

Louse infestations have been reported from many areas

of the world.

2,4,7–9,41–48

Pediculosis has been estimated

to produce annual net profit losses of 5–85%, with

weight loss and fibre damage resulting from disturbed

feeding and sleeping schedules and stress in association

with pruritus.

41,42,44

Heavy louse infestations cause alpacas to bite, rub and

kick their skin, resulting in variable degrees of traumatic

alopecia, excoriation and secondary bacterial infec-

tions.

2,4,7–9,41,42,44–47

Chewing lice may be more numer-

ous on the rump, dorsal trunk and neck, and sucking lice

on the head, neck and shoulder. Heavy infestations with

sucking lice may produce anaemia. Diagnosis is made by

parting the fleece in various areas and visualizing lice on

the skin surface and

⁄ or eggs (‘nits’) attached to the fibres

(often 5–10 mm above skin surface).

Treatment recommendations for pediculosis in alpacas

are often anecdotal and contradictory. Topical applications

have been reported usually to be ineffective.

46

Repeated

injections of ivermectin or moxidectin have been reported

to be effective,

41,44

or effective for sucking lice but not

for chewing lice.

7

A single alpaca was reported to be

cured

with

topical

applications

of

cypermethrin

(10 mg

⁄ kg), but no follow-up period was stated.

45

Eradi-

cation of B. breviceps from 25 alpacas in Australia was

achieved with two 8 min shower-dip applications of

spinosad (25 g

⁄ L) in combination with a surfactant wet-

ting agent (alcohol alkocylate at 1000 g

⁄ L) with a 17-day

interval.

47

If feasible, shearing is a useful prelude to the

use of antiparasitic agents. We did not diagnose pediculo-

sis in our retrospective study.

Miscellaneous ectoparasites

Anecdotal reports indicate that alpacas may be infested

with fleas; attacked by mosquitoes, black flies, tabanids

and ticks; and suffer from myiasis.

7–9

The same reports

indicate that Otobius megnini (spinose ear tick) can affect

alpacas in the western USA, causing head shaking and

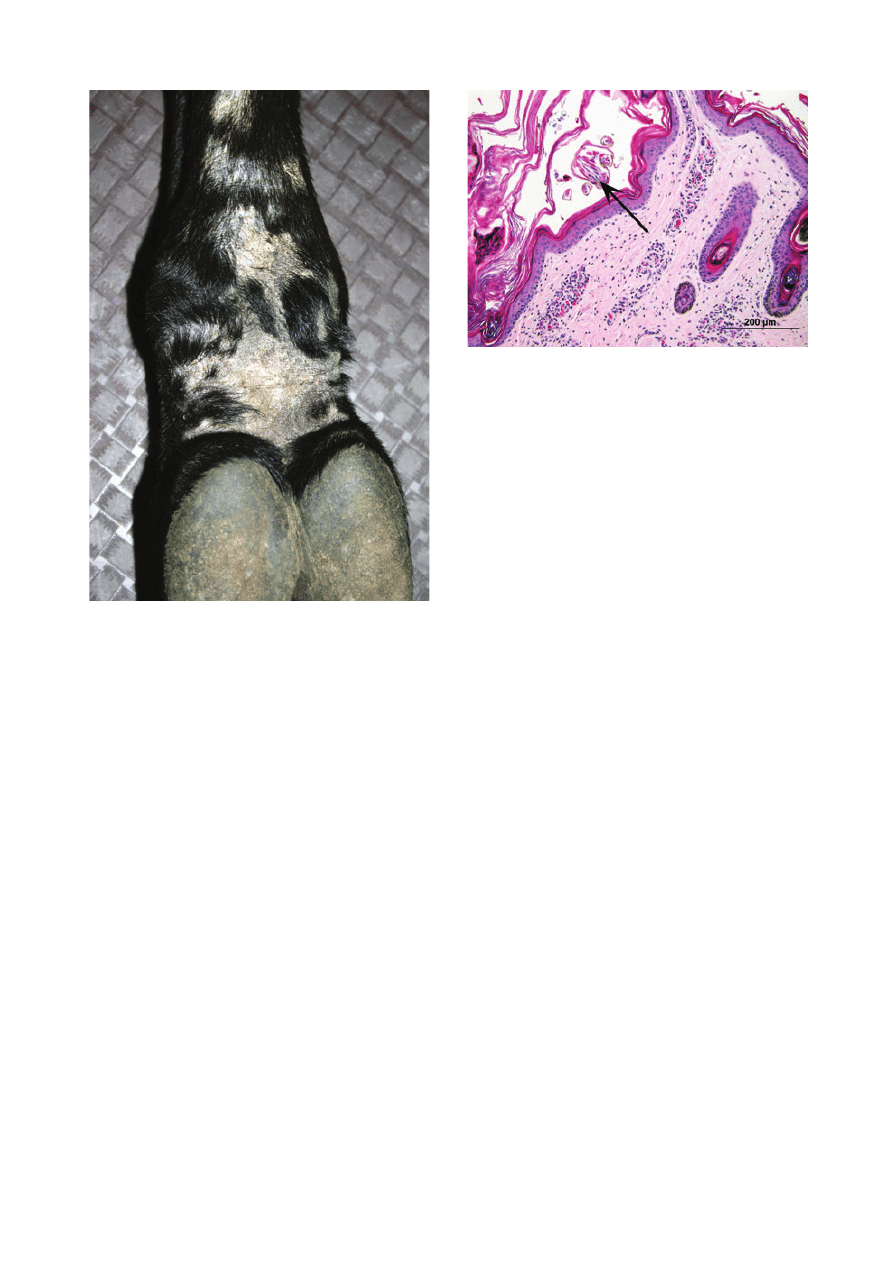

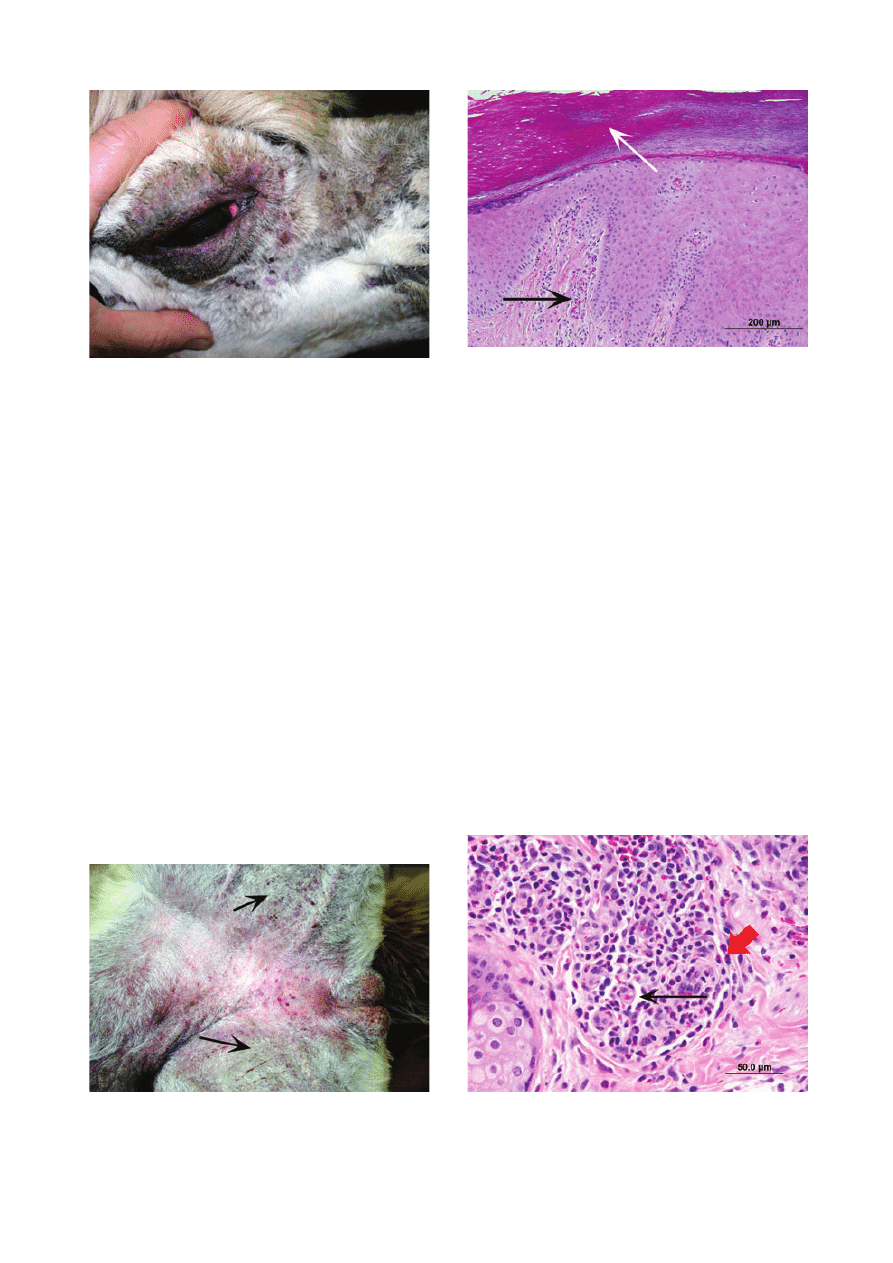

Figure 4. Caudal pastern of an alpaca with chorioptic mange. Note

alopecia, scaling and crusts.

Figure 5. Photomicrograph of skin-biopsy specimen from an alpaca

with chorioptic mange. Note cross-section of mite (arrow) in surface

keratin. Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 200 lm.

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

7

Skin diseases in the alpaca

otorrhoea.

7–9

Ivermectin injections (0.2 mg

⁄ kg) were

reported to be an effective treatment.

Neoplastic and non-neoplastic tumours

In a retrospective study of 368 alpaca specimens (biopsy

or necropsy) from the northwestern USA, neoplasia was

diagnosed in 18 animals (prevalence of 4.9%).

49

Cutane-

ous and mucocutaneous neoplasms accounted for 50%

of the cases. Eight of the nine skin neoplasms were

characterized as fibropapillomas or fibromas. Affected

animals ranged from 4 to 12 years old, and had single or

multiple lesions on the face, nose, lip or distal leg. Poly-

merase chain reaction studies to look for papillomavirus

DNA were not performed. One alpaca in this report had a

solitary fibrosarcoma on the lip.

Mucocutaneous fibropapillomas associated with a

unique camelid papillomavirus were reported in three

alpacas, all of which were 6 years old, from the northeast-

ern USA.

50

Lesions manifested as grey, hyperkeratotic,

nodular masses on lips or cheeks. Histologically, the

masses were similar to equine sarcoids. Polymerase

chain reaction testing revealed that all lesions were posi-

tive for papillomavirus DNA that had 73% homology with

bovine papillomavirus-1. In two animals, lesions were

surgically excised, with no recurrence after a 9-month

follow-up period.

Multiple trichoepitheliomas were reported in a 13-year-

old male alpaca.

51

The lesions were well-circumscribed,

ovoid, 1–4 cm diameter dermal masses distributed over

both sides of the body (especially neck, thorax and rump).

Neoplastic and non-neoplastic tumours accounted for

19% of the cases in our retrospective study (Table 1).

Two animals had multiple presumed viral papillomas

⁄

fibropapillomas (raised, hyperkeratotic, 0.2–2 cm diame-

ter) on the lips (case 41) or on three pasterns (case 42).

Histological findings were typical for papillomavirus infec-

tion (koilocytosis, irregularities in keratohyalin granule

morphology), but no specific tests were performed.

There had been no regression of nonexcised lesions after

6–12 months. Two animals (cases 57 and 58) had solitary

fibromas

(white,

alopecic,

firm,

2–3 cm

diameter)

excised from the lower lip with no recurrence after

24–36 months. A solitary dermal melanocytoma (black,

alopecic, firm, 4 mm diameter) was excised from the

right lower eyelid with no recurrence after 48 months

(case 59). A solitary trichoepithelioma (alopecic, firm,

ulcerated) was excised from the lateral neck region with

no recurrence after 24 months (case 60). One animal

(case 61) had multiple subcutaneous lymphomas widely

distributed over the body. The animal was euthanized,

and necropsy was not performed.

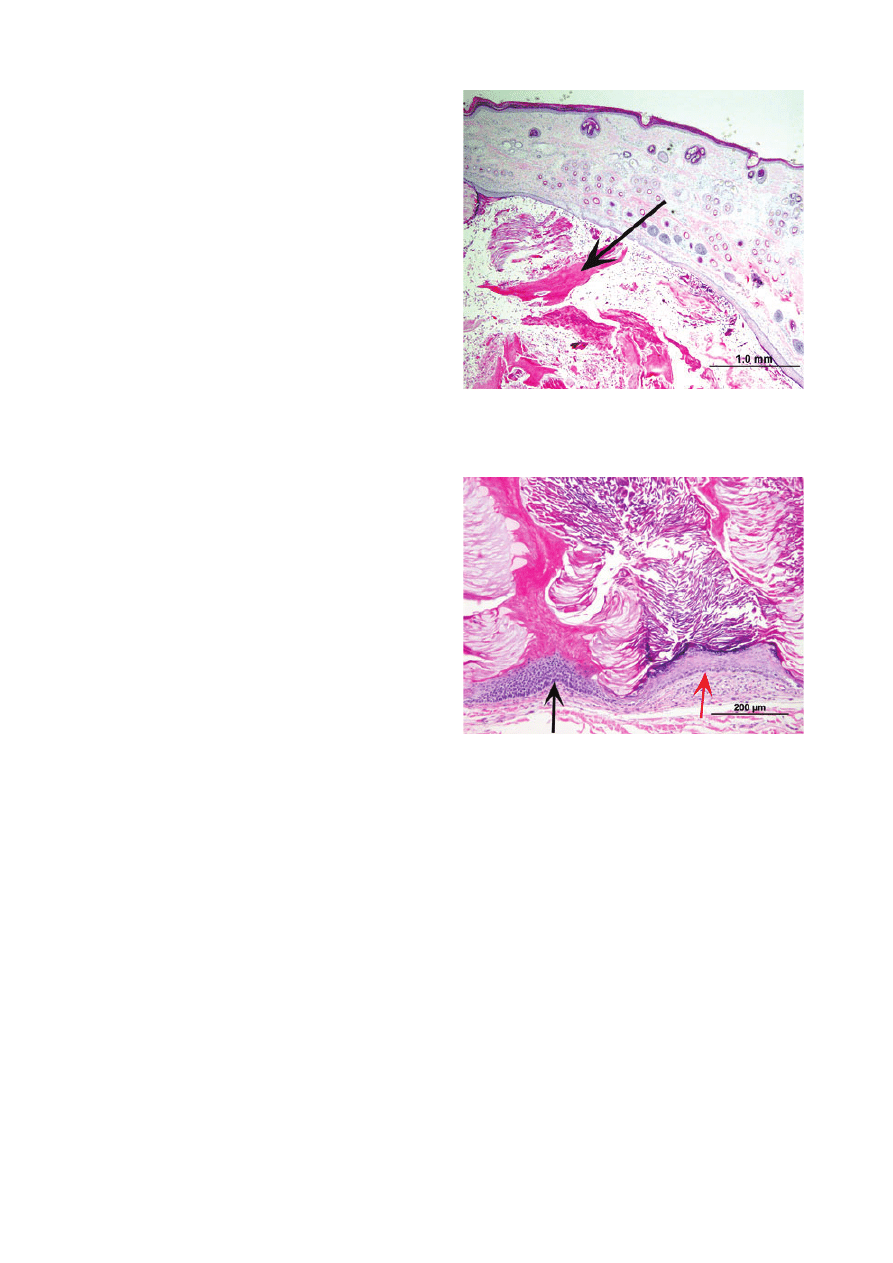

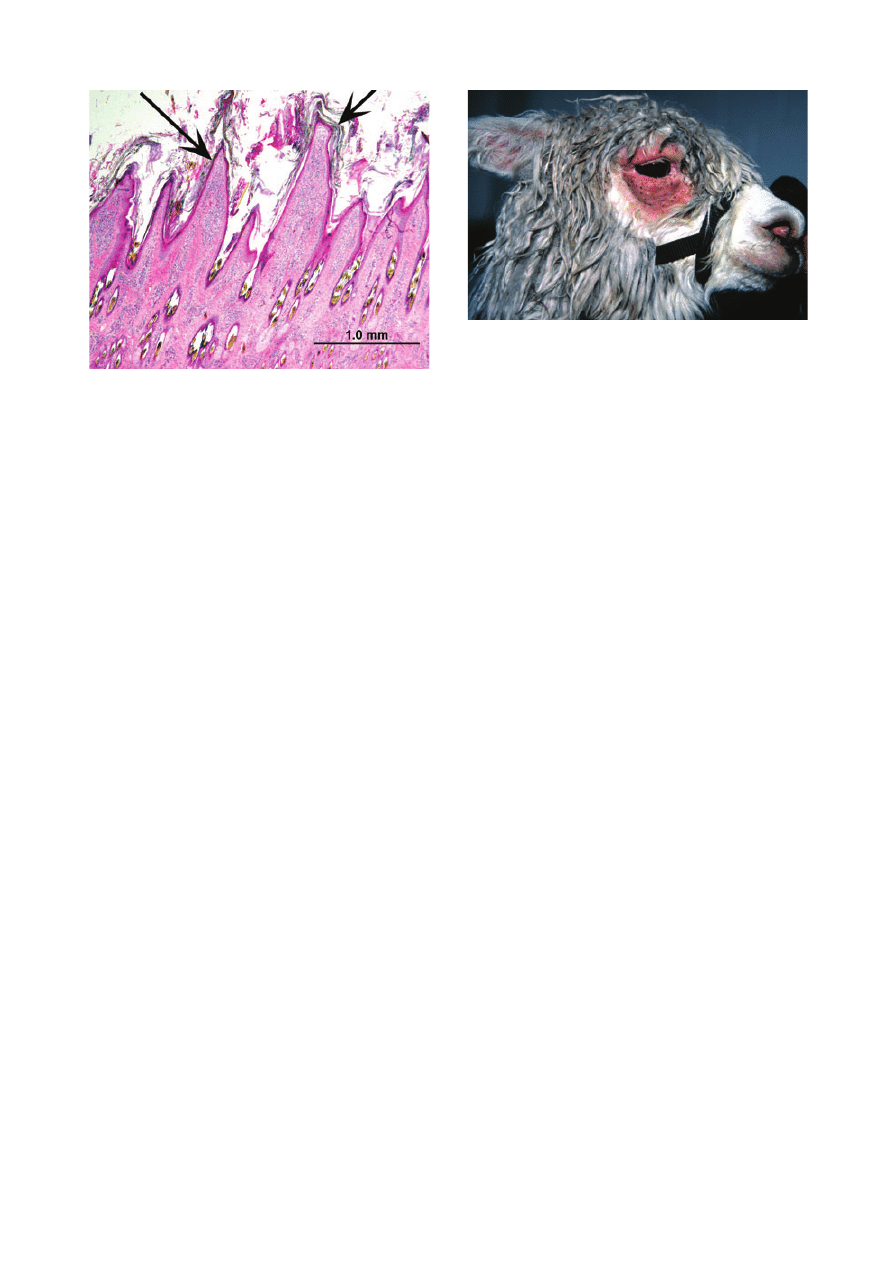

Three animals (cases 54–56) had multiple hybrid follicu-

lar cysts (Figures 6 and 7; white, smooth, 1–3 cm diame-

ter, occasional spontaneous caseous black discharge)

widespread over the body, especially the trunk. Cytologi-

cal examination of the caseous discharge revealed

corneocytes and numerous melanin granules. Lesions

seemed to be stable during 6- to 24-month follow-up

periods.

Multiple hamartomas were diagnosed in three animals.

In case 68, the lesions (firm, smooth) were present on

eyelid, neck and foot. Histologically, these were collage-

nous hamartomas. The lesions seemed stable over a

12-month follow-up period. In two animals (cases 39 and

40), a mother and daughter, lesions were first noted at

about 3 years of age. The lesions were multiple, multifocal

(especially the trunk), firm, round-to-rectangular, slightly

elevated dermal plaques varying from 1 to 10 cm in diam-

eter. Fleece loss was minimal, and the skin overlying the

lesions was smooth to mildly hyperkeratotic. Lesions

were neither pruritic nor painful. Histologically, these

lesions were hair follicle hamartomas (Figure 8). Lesions

seemed to be stable after a 12-month follow-up period.

Environmental diseases

Traumatic wounds

Anecdotal reports indicate that lacerations and puncture

wounds are common in alpacas.

7,8

Lacerations (especially

to the pinnae, neck, caudal pelvic limbs and scrotum) are

often produced by barbed wire fencing or by aggressive

Figure 6. Photomicrograph of hybrid follicular cyst excised from an

alpaca. Cyst cavity (arrow) contains both lamellar and tricholemmal

keratin. Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 1 mm.

Figure 7. Close-up

of

Figure 6.

Tricholemmal

differentiation

(black arrow) and associated tricholemmal keratinization alternates

with epidermal differentiation (red arrow) and associated lamellar

keratinization. Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 200 lm.

8

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

Scott et al.

males interacting with other males or attacking females.

Dogs (individually or in packs) can inflict horrible wounds

that can be lethal.

We diagnosed dog bite wounds in eight alpacas (cases

1–8). Seven of the eight animals were approximately

1 year old. Bite wounds most commonly involved the

neck and hindlimbs, and cellulitis and subcutaneous

emphysema were present in six and four cases, respec-

tively. All animals received aggressive emergency and

supportive care, but five (62%) died.

Contact dermatitis

Anecdotal reports indicate the contact dermatitis can

be seen in alpacas.

7,8

Incriminated contactants include

plants, chemicals and povidone-iodine. Anecdotal reports

indicate that shearing alpacas with clippers that are too

hot can result in thermal burns, which may result in

sloughing of severely damaged skin several weeks later.

We made a presumptive diagnosis of contact dermatitis

and secondary bacterial folliculitis in one alpaca (case 44)

in our retrospective study. The animal had a chronic his-

tory of pruritic dermatitis affecting the entire ventrum.

Histological findings included suppurative luminal folliculi-

tis and a superficial perivascular-to-interstitial lymphoplas-

macytic dermatitis. Eosinophils were rarely seen. Pruritic

dermatitis continued after the bacterial infection was trea-

ted with ceftiofur. Prednisone (1 mg

⁄ kg once daily) was

administered p.o. for 14 days, the animal’s access to the

outdoor environment was restricted, and the pruritic

dermatitis completely resolved. Provocative exposure

was not attempted. No relapse was seen over an 18-

month follow-up period.

Snake bite

Rattlesnake envenomation has been reported in the

southwestern USA.

52

Most bites occur in the period from

spring to summer, especially at night or early morning,

and most commonly involve the face. Bite wounds and

swelling are present, and concurrent systemic signs

(especially tachypnoea, respiratory distress and hyper-

thermia) may be seen in alpacas.

Miscellaneous diseases

Noninflammatory alopecia

Shedding in alpacas may be imperceptible or occur as pat-

chy alopecia, especially over the neck.

7

It is occasionally

mistaken for a sign of disease.

Anecdotal reports indicate that large patches of hair

may be lost with no apparent inciting cause.

8

Often the

hairs appear broken off, and analogous to ‘wool break’

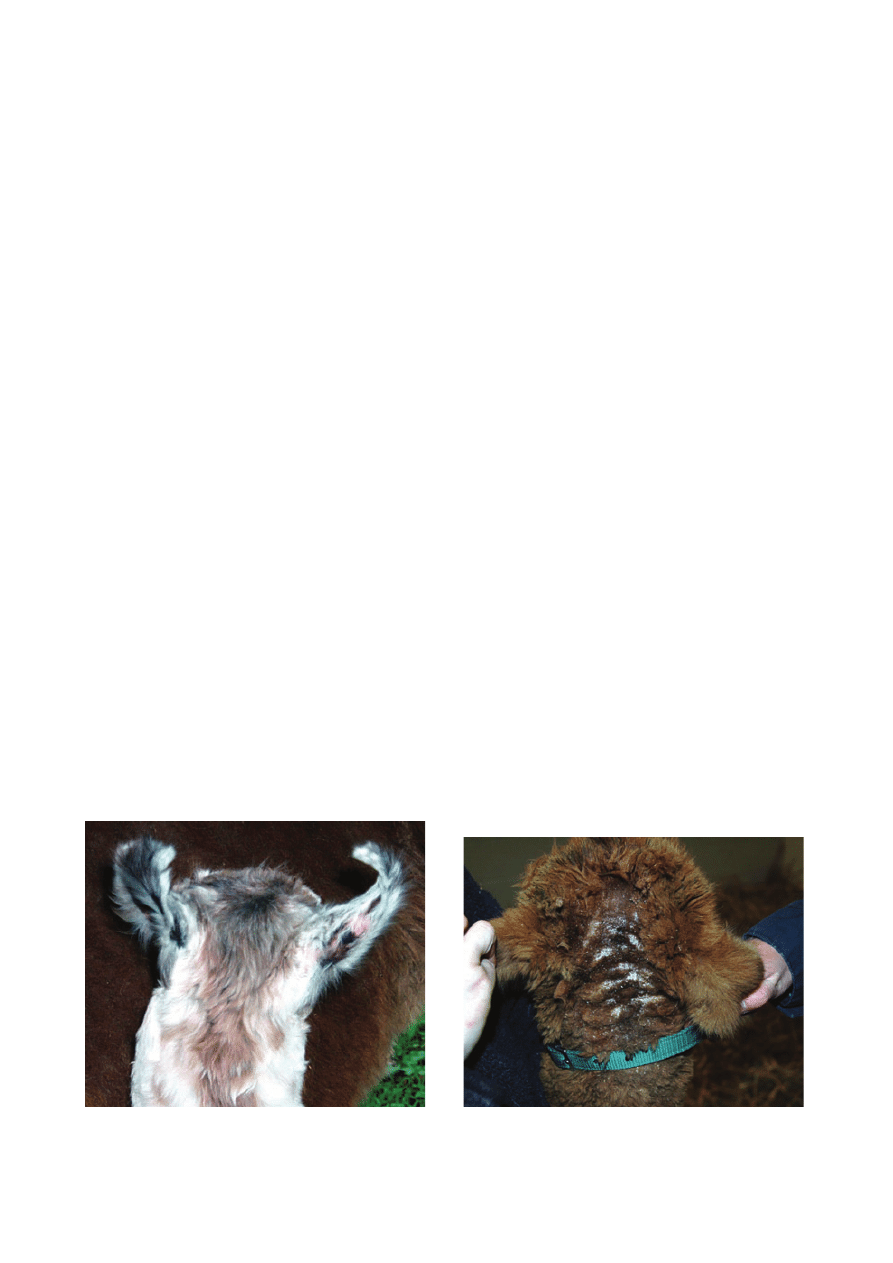

(anagen defluxion) in sheep. We diagnosed anagen

defluxion

53

in a cria (case 34) that acutely developed mul-

tiple areas of hair loss over the face, trunk and legs 7 days

after the onset of a diarrhoeal disorder (Salmonella sp.

cultured from faeces) and antibiotic therapy (Figure 9).

The skin appeared normal, and short, broken-off hairs

could be seen and palpated in the hypotrichotic areas.

Trichographic findings were consistent with anagen

defluxion. We also diagnosed telogen defluxion

53

in an

alpaca (case 35) presented for the acute onset of hair loss

over the trunk and face several weeks after a poorly

defined illness (Figure 10). The skin appeared normal, and

hair was totally absent in alopecic areas. Trichographic

findings were consistent with telogen defluxion.

Figure 8. Photomicrograph of hair follicle hamartoma excised

from an alpaca. The middle and deep dermis are filled with hyper-

plastic hair follicles (arrow). Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar =

1 mm.

Figure 9. Anagen defluxion in an alpaca cria in association with a

diarrhoeal disorder. Note noninflammatory hair loss on the legs.

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

9

Skin diseases in the alpaca

Immunological diseases

Anecdotal reports indicate that pemphigus-like diseases,

adverse cutaneous drug reactions, cutaneous vasculitis,

and food and environmental allergies may occur in alpa-

cas.

2,10

We diagnosed presumed pinnal vasculitis associ-

ated with a tooth root abscess in one alpaca (see

discussion of case 18 with tooth root abscess).

We diagnosed a presumed adverse cutaneous drug

reaction in a 5-year-old male alpaca (case 38) with an

acute history of skin and systemic disease following an

injection of ivermectin. The animal first developed

‘bumps’ on the pinnae, which rapidly progressed to ulcers

and general pinnal swelling (Figure 11). The alpaca

became febrile, depressed and inappetent, and skin

lesions appeared on the perineum and ventral abdomen.

When the animal was examined at the CUHA, additional

findings included numerous pustules on the ventral abdo-

men, prepuce, perineum, and inguinal and axillary areas

(Figure 12). Skin scrapings and trichography were nega-

tive. Cytological examination of pus revealed eosinophils

and nondegenerate neutrophils, and no microorganisms.

A pustule was cultured and was negative for bacteria and

fungi. Results of routine haematology and serum bio-

chemistry panel were unremarkable. Histological findings

of multiple skin biopsies were characterized by eosino-

philic and neutrophilic epidermitis and luminal folliculitis

and furunculosis (Figure 13), and special stains for micro-

organisms were negative. The alpaca was treated with

methylprednisolone (1 mg

⁄ kg given once daily p.o.) and

Figure 11. Presumed adverse cutaneous drug reaction due to iver-

mectin in an alpaca. Note linear ulcer on convex (dorsal) surface of

pinna.

Figure 12. Same alpaca as in Figure 11. Note multiple pustules

(arrow) on ventral abdomen.

Figure 10. Telogen defluxion in an adult alpaca following a poorly

defined illness. Note noninflammatory hair loss on face.

Figure 13. Photomicrograph of skin-biopsy specimen from the

alpaca in Figures 11 and 12. Large pustule (large arrow) is formed by

coalescence of furunculosis of three pilosebaceous units (small

arrows). Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 1 mm.

10

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

Scott et al.

completely recovered. Ivermectin has not been readmin-

istered, and the alpaca remains normal after a 12-month

follow-up period.

Idiopathic urticaria was diagnosed in one alpaca (case

50) in our retrospective study. The animal had recurring

nonpruritic wheals over the neck and trunk. No triggering

agents were identified. Histological findings included

pure superficial perivascular lymphoeosinophilic derma-

titis with moderate superficial dermal oedema. After a

several week course of lesions, the condition disappeared

for a 72-month follow-up period.

Presumed insect-bite hypersensitivity (probably associ-

ated with Culicoides spp. gnats) was diagnosed in five

alpacas (cases 29–32 and 51) in our retrospective study.

Four animals (cases 29, 31, 32 and 51) had a recurrent or

seasonal (spring to autumn) pruritic dermatitis for ‘several

years’, which spontaneously resolved without treatment

every winter. All five alpacas were the only affected ani-

mals in their respective herds. Treatment with ivermectin

had been ineffective. Lesions had the following character-

istics: (i) they were more-or-less symmetrical; (ii) they

most commonly affected the pinnae, periocular area,

bridge of the nose, axillae, groin, ventral mid-line and dis-

tal legs; and (iii) they consisted of alopecia, crusts, licheni-

fication and occasionally papules (Figures 14 and 15).

Skin scrapings and trichography were negative in all

cases. Cytological examination revealed eosinophilic

inflammation in two animals. Two animals (cases 29 and

31) had concurrent bacterial folliculitis (see earlier discus-

sion). Histological findings in biopsy specimens from two

alpacas (cases 29 and 51) included eosinophilic interstitial

dermatitis, eosinophilic epidermal microabscesses, eosin-

ophilic infiltrative mural and luminal folliculitis, and com-

pact orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis (Figures 16 and 17).

The latter finding is consistent with chronic rubbing,

scratching and chewing in response to pruritus. Three ani-

mals (cases 29, 30 and 32) improved markedly with pro-

tective housing (dusk to dawn) and permethrin-containing

sprays.

Congenital diseases

Ichthyosis was diagnosed in three alpacas (cases 36, 52

and 53). The animals had a generalized keratinization dis-

order since birth or shortly thereafter. Fine, nonadherent

white scales covered nearly the entire body surface and

were scattered throughout the fleece. In one of the ani-

Figure 14. Presumed insect-bite hypersensitivity in an alpaca. Note

alopecia, erythema and multiple crusts on face.

Figure 15. Same alpaca as in Figure 14. Note alopecia, erythema,

papules and crusts on ventral abdomen, medial thighs (arrows) and

perineum.

Figure 16. Photomicrograph of skin-biopsy specimen from an alpaca

with presumed insect-bite hypersensitivity. Note hyperplastic peri-

vascular dermatitis (black arrow) with compact orthokeratotic hyper-

keratosis (white arrow) consistent with chronic rubbing, scratching

and chewing in response to pruritus. Haematoxylin and eosin; scale

bar = 200 lm.

Figure 17. Close-up of Figure 16. Note perivascular (black arrow

indicates segment of blood vessel) accumulation of eosinophils (red

arrow). Haematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 50 lm.

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

11

Skin diseases in the alpaca

mals, multiple areas of erythema were present on the

abdomen. Pruritus was absent, and the animals appeared

to be otherwise healthy. Parents and relatives of these

alpacas were reported to be unaffected. Histological find-

ings in skin-biopsy specimens revealed diffuse orthokera-

totic hyperkeratosis (epidermis and hair follicles) and

minimal to no inflammation. Eosinophils were not seen.

Treatment was not attempted, and two animals were

euthanized (no necropsy performed).

Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis occurred in

six crias (cases 62–67) on the same farm in our retrospec-

tive study. All cria were affected at birth. There was no

history of prior trauma to the pinna. The same sire and

three different dams were involved. The sire had been

used on other farms and had reportedly produced other

affected cria. Multiple small, fluid-filled, flat plaques

occurred on the lateral surface of both pinnae. Signs of

infection (heat, discoloration, wounds and draining tracts)

were not present. Pruritus and otitis were not present,

and the crias were otherwise healthy. Skin-biopsy speci-

mens were taken with a 6-mm biopsy punch when the

haematomas were drained. Pinnal lesions healed with

scarring and deformation (Figure 18). Histological findings

included variable combinations of dermal oedema and

haemorrhage, and necrotic cartilage which was dissected

by neutrophils.

Zinc-responsive dermatitis

Zinc-responsive dermatitis accounted for 23% of the der-

matological diagnoses made by attending veterinarians in

the UK postal survey,

10

but only 8% of the cases in our

retrospective study.

There is limited peer-reviewed literature on the subject

of zinc-responsive dermatitis in alpacas.

2–5,8–10

Lesions

consist of scales and papules and plaques with thick,

tightly-adherent crusts, which are most commonly seen

in relatively hairless areas such as the perineum, ventral

abdomen, groin, medial thighs, axillae and medial fore-

legs. The bridge of the nose, muzzle and periocular region

may also be affected. Pruritus is absent or mild. It has

been suggested that young animals (1–2 years old),

males, and animals with dark fleeces may be more fre-

quently affected.

5,8

Typically, only a few individuals in a

herd are affected.

In a study conducted on a German farm,

54

the zinc sta-

tus of alpacas was evaluated. The animals were supple-

mented with a commercial camelid feed, but their hay

had an inadequate mineral content. Twenty-five per cent

of the animals in the herd had lesions on the bridge of the

nose and the pinnae. Only females were affected, and all

had given birth that year or were pregnant. Animals with

nonwhite fleeces were more likely to have skin lesions.

There was no influence of sex, fleece colour or breed (suri

versus huacaya) on serum zinc or copper concentrations.

It was not possible to distinguish affected from nonaffect-

ed alpacas based on serum mineral concentrations. The

authors of this study made the following suggestions: (i)

that skin lesions are most likely to occur first in breeding

females when the mineral content of the diet is marginal;

(ii) that dark fleeces, which contain more zinc and copper

than white fleeces, are likely to exert higher demands on

mineral metabolism; and (iii) that serum zinc concentra-

tions may not reflect total body zinc levels. Histological

findings are reported to include diffuse orthokeratotic

hyperkeratosis (epidermis and hair follicles) and a mild to

moderate perivascular dermatitis containing lympho-

cytes, macrophages, plasma cells and occasional eosin-

ophils.

2–5,8,54

Diagnosis is based on history, physical examination,

ruling out other differential diagnoses, and response to

zinc supplementation. Animals are given 1–2 g ZnSO

4

or

2–4 g zinc methionine, once daily, p.o., with improvement

being seen within 30–90 days.

2,4,8,54

We diagnosed zinc-responsive dermatitis in five alpa-

cas (cases 19–23) presenting with chronic histories of

nonpruritic dermatitis consisting of alopecia, adherent

scales, hair casts, thick crusts and occasional hyperkera-

tosis. Lesions most commonly occurred on the face

(muzzle, periocular region), pinnae, neck, ventral abdo-

men, medial thighs and medial forelegs (Figure 19). The

feet and distal legs were less commonly affected. The

animals were on good diets with no mineral supplements

Figure 18. Bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis in a cria. Note

scarring and disfigurement of both pinnae.

Figure 19. Zinc-responsive dermatitis in an alpaca. Thick scale and

crusts on top of head and dorsal neck.

12

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

Scott et al.

and were generally the only individual in the herd

affected. Case 19 was one of a herd of 52 alpacas, two

others of which had ‘a similar skin problem’. Skin biopsies

were performed in three animals (cases 19, 20 and 22)

and revealed lymphoeosinophilic superficial perivascular

dermatitis with papillated epidermal hyperplasia, papillo-

matosis, and predominantly lamellar orthokeratotic hyper-

keratosis of the epidermis and hair follicle infundibula

(Figure 20). Occasional papillae were ‘capped’ with

parakeratotic hyperkeratosis. The skin lesions in all five

alpacas were reported to have resolved with zinc methio-

nine (2 g

⁄ day p.o.). Zinc supplementation was continued,

and all five alpacas were in remission following periods of

6–12 months.

Focal sterile eosinophilic and neutrophilic folliculitis and

furunculosis

A 1-year-old male alpaca (case 37) presented to the CUHA

with a 1-month history of dermatitis and pruritus around

the right eye. The other animals in the herd were unaf-

fected. Previous treatment with topical miconazole and

oral enrofloxacin was unsuccessful. The right periocular

area was alopecic, erythematous and oedematous with a

few pustules and crusts (Figure 21). Skin scrapings and

trichography were negative. Cytological examination

revealed eosinophilic inflammation. Histological findings

included eosinophilic folliculitis and furunculosis, and spe-

cial stains were negative for microorganisms. Prednisone

administered p.o. (1 mg

⁄ kg once daily for 2 weeks) was

curative. This condition is similar to the sterile eosinophilic

folliculitis and furunculosis that occurs in dogs

55

and

horses,

56

presumably associated with insect envenoma-

tion.

Idiopathic nasal

⁄ perioral hyperkeratotic dermatosis

Idiopathic nasal

⁄ perioral hyperkeratotic dermatosis (‘mun-

ge’) is anecdotally reported to occur in alpacas.

2–5,7,8

This

condition is very poorly understood and may, in fact, be

nothing more than a reaction pattern in the skin caused

by many different factors.

The dermatosis usually begins at 6–24 months of age.

The nasal and periocular areas become covered with thick

crusts that occasionally obstruct the nostrils. Lesions

may occasionally occur on the bridge of the nose and peri-

ocular region. Pruritus is usually absent or mild.

Histological findings are reported to include various

combinations of epidermal oedema, hyperplasia and

necrosis; palisaded crusts (orthokeratotic

⁄ parakeratotic

hyperkeratosis and pus); and a mixed perivascular derma-

titis.

2–5,8

Treatment

observations

are

consistent

with

the

aforementioned idea that many different conditions are

being called ‘munge’. Cases are reported to respond to

topical and

⁄ or systemic antibiotics, topical and ⁄ or sys-

temic glucocorticoids, oral zinc, or to regress sponta-

neously.

2–5,8

We

presently

believe

that

idiopathic

nasal

⁄ perioral hyperkeratotic dermatosis is a cutaneous

reaction pattern of alpacas possibly provoked by disor-

ders such as bacterial folliculitis, dermatophilosis, dermat-

ophytosis, contagious viral pustular dermatitis, chorioptic

mange, fly bites, viral papillomas

⁄ fibropapillomas, contact

dermatitis and zinc-responsive dermatitis. The authors

are not aware of any laboratory tests or therapeutic

interventions that allow one to diagnose ‘munge’. Such a

multifactorial aetiology could explain the anecdotal suc-

cesses of popular topical concoctions such as ‘witches

brew’, which contains gentamicin, ivermectin, dimethyl

sulfoxide and mineral oil.

57

Discussion

The popularity and numbers of alpacas have increased in

many parts of the world.

1–4,10,40

This naturally has led to

increasing demands for veterinary care. The number of

alpaca patients at our university practice increased

approximately 13-fold over a 10-year period. During this

period of time, dermatological diseases were docu-

mented in 5.6% of the alpacas, which is similar to previ-

ously reported data on our equine patients (4.1% of all

horses over a 21 year period).

58

Skin-biopsy specimens

accounted for 24.4% of all alpaca biopsy specimens

received over the 10 year period, which is again similar to

previously reported data on our equine population (23.4%

of all biopsy specimens).

58

Figure 20. Photomicrograph of skin-biopsy specimen from an alpaca

with zinc-responsive dermatitis. Note papillated epidermal hyperpla-

sia, papillomatosis (arrows) and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. Hae-

matoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 1 mm.

Figure 21. Presumed insect-bite reaction in an alpaca. Periocular

alopecia, erythema, oedema, pustules and crusts.

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

13

Skin diseases in the alpaca

To our knowledge, this literature review and retrospec-

tive case study is the first one entirely devoted to alpacas.

While some of our experiences are similar to those

reported in peer-reviewed and anecdotal literature, there

were some notable differences. For instance, while bac-

terial and neoplastic dermatoses accounted for only 5%

and 0%, respectively, of the conditions diagnosed in a UK

postal survey,

10

these two categories accounted for 22%

and 19%, respectively, of the dermatological diagnoses

in our retrospective study conducted in the northeastern

USA. Anecdotal literature (veterinary and lay) suggests

that dermatophilosis and dermatophytosis are routinely

diagnosed in alpacas. However, in our study, we con-

firmed no cases of the former and only one case of the

latter. Our case of dermatophytosis had no histological

evidence of hair shaft invasion, similar to what is seen

with Microsporum persicolor and Trichophyton mentagro-

phytes var. erinacei infections in dogs.

59,60

In such cases,

plucking hairs for fungal culture usually produces negative

results. We documented no cases of sarcoptic mange or

pediculosis.

In our study, we have also documented the clinicopath-

ological details of several cases of bacterial folliculitis, as

well as several previously unreported conditions, to

include intertrigo, collagenous and hair follicle hamarto-

mas, melanocytoma, lymphoma, hybrid follicular cysts,

anagen defluxion, telogen defluxion, a presumed adverse

cutaneous drug reaction to ivermectin, a presumed focal

insect-bite reaction and a unique, possibly hereditary

syndrome of bilateral aural haematomas and chondritis.

Ichthyosis had previously been reported in a llama,

61

and

we report three cases in the alpaca. The three alpacas

with multiple hamartomas precipitated a discussion of

the syndrome of multiple collagenous hamartomas (‘nod-

ular dermatofibrosis’) in association with renal disease as

recognized in dogs.

62

However, the owners declined

ultrasound examinations for their animals.

To our knowledge, we provide the original description of

alpacas with presumed insect-bite hypersensitivity. In our

practice area, the seasonality, environmental exposure

and clinicopathological features of the condition are con-

sistent with documented or presumed Culicoides hyper-

sensitivity in horses,

63

sheep,

64–66

goats

64

and cattle.

64,65

Skin-biopsy specimens were procured from three of

five alpacas with zinc-responsive dermatitis. The keratini-

zation abnormality in these three specimens was diffuse

and predominantly orthokeratotic. This is unlike the dif-

fuse parakeratotic hyperkeratosis classically reported in

swine,

67

cattle

68

and dogs.

69

In sheep

70–72

and goats,

73,74

however, the keratinization abnormality in zinc-responsive

dermatoses has been reported to be parakeratotic, ortho-

keratotic or a combination of both of these.

It has been suggested that eosinophils are commonly

present in chronic inflammatory dermatoses of alpacas

and are of little diagnostic significance.

2

In our study,

eosinophils were consistently numerous in presumed

insect-bite hypersensitivity, chorioptic mange, psoroptic

mange, zinc-responsive dermatitis, and in single cases

of urticaria, presumed focal insect-bite reaction and

presumed adverse cutaneous drug reaction. However,

eosinophils were rarely seen in cases of bacterial folliculi-

tis, dermatophytosis, contagious viral pustular dermatitis,

presumed

contact

dermatitis,

ichthyosis

and

aural

haematomas with chondritis.

In conclusion, skin disease is commonly seen in alpa-

cas, and the possible causes are many. We hope this

article will encourage practitioners and specialists to

investigate alpaca dermatoses in greater depth and with

enthusiasm and to report their findings. There is much to

be learned.

References

1. D’Alterio GL. Introduction to the alpaca and its veterinary care in

the UK. In Practice 2006; 28: 404–11.

2. Foster A, Jackson A, D’Alterio GL. Skin diseases of South Ameri-

can camelids. In Practice 2007; 29: 216–23.

3. Zanolari P, Meylan M, Roosje P. Dermatologie bei Neuweltka-

melidin. Teil 1: Propa¨deutik und dermatologische Diagnostik.

Tiera¨rztliche Praxis 2008; 36: 304–8.

4. Plant JD. Update on camelid dermatology. Proceedings of the

International Camelid Health Conference. Oregon State Univer-

sity, Corvallis, OR, 2007. pp. 127–30.

5. Rosychuk RAW. Llama dermatology. Veterinary Clinics of North

America – Food Animal Practice 1989; 5: 203–14.

6. Rosychuk RAW. Llama dermatology. Veterinary Clinics of North

America – Food Animal Practice 1994; 10: 228–39.

7. Fowler ME. Skin problems in llamas and alpacas. Llama 1989; 3:

45–8.

8. Fowler ME. Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids.

Llama, Alpaca, Vicun˜a, Guanaco II. Ames, IA: Iowa State Univer-

sity Press, 1998. pp. 148–209.

9. Fowler ME, Cubas ZS. Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of South

American Wild Animals. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press,

2001. pp. 392–401.

10. D’Alterio GL, Knowles TG, Eknaes EI et al. Postal survey of the

population of South American camelids in the United Kingdom in

2000

⁄ 01. Veterinary Record 2006; 158: 86–90.

11. Anderson DE, Ring DM, Kowalski J. Infection with Corynebacte-

rium pseudotuberculosis in 5 alpacas. Journal of the American

Veterinary Medical Association 2004; 225: 1743–7.

12. Braga WU, Chavera A, Gonzalez A. Corynebacterium pseudotu-

berculosis infection in highland alpacas (Lama pacos) in Peru.

Veterinary Record 2006; 159: 23–4.

13. Braga WU, Chavera AE, Gonza´lez AE. Clinical, humoral, and

pathologic findings in adult alpacas with experimentally induced

Corynebacterium

pseudotuberculosis

infection.

American

Journal of Veterinary Research 2006; 67: 1570–4.

14. Cebra ML, Cebra CK, Garry FB. Tooth root abscess in New

World camelids: 23 cases (1972–1994). Journal of the American

Veterinary Medical Association 1996; 209: 819–22.

15. Niehaus AJ, Anderson DE. Tooth root abscesses in llamas and

alpacas: 123 cases (1994–2005). Journal of the American Veteri-

nary Medical Association 2007; 231: 284–9.

16. Portaels F, Chemlal K, Elsen P et al. Mycobacterium ulcerans

in wild animals. Revue Scientifique et Technique 2001; 20:

252–64.

17. Preston Smith H. Ectima de los animales del Peru, dermatitis

pustular contagiosa. Ganaderia (Peru) 1947; 1: 27–32.

18. Geurden T, Deprez P, Vecruysse J. Treatment of sarcoptic, psor-

optic, and chorioptic mange in a Belgian alpaca herd. Veterinary

Record 2003; 153: 331–2.

19. Jarvinen JA, Miller JA, Oehler DD. Pharmacokinetics of ivermec-

tin in llamas (Lama glama). Veterinary Record 2002; 150: 344–6.

20. Hunter RP, Isaza R, Koch DE et al. The pharmacokinetics of topi-

cal doramectin in llamas (Lama glama) and alpacas (Lama pacos).

Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2004; 27:

187–9.

21. Hunter RP, Isaza R, Koch DE et al. Moxidectin plasma concen-

trations following topical administration to llamas (Lama glama).

Small Ruminant Research 2004; 52: 275–9.

14

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

Scott et al.

22. Burkholder TH, Jensen J, Chen H et al. Plasma evaluation for

ivermectin in llamas (Lama glama) after standard subcutaneous

dosing. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2004; 35: 395–6.

23. Mellanby K. Sarcoptic mange in the alpaca. Transactions of the

Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1946; 40: 359.

24. Alverado J, Astrom RG, Heath GBS. An investigation into reme-

dies of sarna (sarcoptic mange) of alpacas in Peru. Experimental

Agriculture 1966; 2: 245–54.

25. Chuvela J, Guerrero Diaz CA. Evaluacion de metodos en el

tratamiento de la sarna de alpacas. Revista de Investigaciones

Pecuarias 1973; 2: 23–8.

26. Leguia G. The epidemiology and economic impact of llama para-

sites. Parasitology Today 1991; 7: 54–5.

27. Ramos-Acunatt H, Catrejon-Valdez M, Valencia-Mamani N et

al. Control of sarcoptic mange (Sarcoptes scabiei var auche-

niae) in alpacas (Lama pacos) in Peru, with injectable long-

acting 1% W

⁄ W ivermectin. Veterinaria Argentina 2001; 17:

570–7.

28. McKenna PB, Hill FI, Gillett R. Sarcoptes scabiei infection on an

alpaca (Lama pacos). New Zealand Veterinary Journal 2005; 53:

213.

29. Borgsteede FHM, Timmerman A, Harmsen MM. Een geval van

emstige Sarcoptes – schurft bij alpacas (Lama pacos). Tijdschrift

voor Diergeneeskunde 2006; 131: 282–3.

30. Lau P, Hill PB, Rybnı´cˇek J et al. Sarcoptic mange in three alpacas

treated successfully with amitraz. Veterinary Dermatology 2007;

18: 272–7.

31. D’Alterio GL, Batty A, Laxon K et al. Psoroptes species in alpa-

cas. Veterinary Record 2001; 149: 96.

32. Bates P, Duff P, Windsor R et al. Mange mite species affecting

camelids in the UK. Veterinary Record 2001; 149: 463–4.

33. Frame NW, Frame RKA. Psoroptes species in alpacas. Veteri-

nary Record 2001; 149: 128.

34. Cremers HJ. The incidence of Chorioptes bovis (Acarina: Psorop-

tidae) in domesticated ungulates. Tropical and Geographical

Medicine 1983; 36: 105.

35. Cremers HJWM. Chorioptes bovis (Acarina: Psoroptidae) in

some camelids from Dutch Zoo. Veterinary Quarterly 1985; 7:

198–9.

36. Young E. Chorioptic mange in the alpaca, Lama pacos. Journal of

the South African Veterinary Medical Association 1996; 47: 474–

5.

37. Petrikowski M. Chorioptic mange in an alpaca herd. In: Kwochka

KW, Willemse T, von Tscharner C, eds. Advances in Veterinary

Dermatology, Vol. 3. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann,

1998:450–1.

38. D’Alterio GL, Jackson AP, Knowles TG et al. Comparative

study of the efficacy of eprinomectin versus ivermectin, and

field efficacy of eprinomectin, for the treatment of chorioptic

mange in alpacas. Veterinary Parasitology 2005; 130: 267–

75.

39. D’Alterio GL, Callaghan C, Just C et al. Prevalence of Chorioptes

sp. mite infestation in alpaca (Lama pacos) in the Southwest of

England: implications for skin health. Small Ruminant Research

2005; 57: 221–8.

40. Plant JD, Kutzler MA, Cebra CK. Efficacy of topical eprinomectin

in the treatment of Chorioptes sp. infestation in alpacas and lla-

mas. Veterinary Dermatology 2007; 18: 59–62.

41. Windsor RHS, Teran M, Windsor RS. Effects of parasitic infesta-

tion on the productivity of alpacas (Lama pacos). Tropical Animal

Health Production 1992; 24: 57–62.

42. Windsor RS, Windsor RHS, Teran M. Economic benefits of con-

trolling internal and external parasites in South American came-

lids. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1992; 653:

398–405.

43. Rojas C, Lobato MY, Montalvo VM. Fauna parasitaria de cami-

lides sudamericanos y ovinos en pequen˜os reban˜os mixtos

familiares. Revista de Pecuaires Investigaciones Peru 1993; 6:

22–7.

44. Cicchino AC, Mun˜oz Coben˜as ME, Bulman GM et al. Identifica-

tion of Microthoracius mazzai (Phthiraptera: Anoplura) as an eco-

nomically important parasite of alpacas. Journal of Medical

Entomology 1998; 35: 922–30.

45. Vaughan JL, Carmichael I. Control of the camelid biting

louse, Bovicola breviceps in Australia. Alpacas Australia 1999;

27: 24–8.

46. Levot G. Resistance and the control of lice in humans and pro-

duction animals. International Journal for Parasitology 2000; 30:

291–7.

47. Vaughan JL. Eradication of the camelid biting louse, Bovicola

breviceps. Australian Veterinary Journal 2004; 82: 216–7.

48. Palma RL, McKenna PB. Confirmation of the occurrence of the

chewing louse Bovicola (Lepikentron) breviceps (Insecta: Phthi-

raptera: Trichodectidae) on alpacas (Lama pacos) in New

Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 2006; 54: 253–4.

49. Valentine BA, Martin JM. Prevalence of neoplasia in llamas and

alpacas (Oregon State University, 2001–2006). Journal of Veteri-

nary Diagnostic Investigation 2007; 19: 202–4.

50. Schulman FY, Krafft AE, Janczewski T et al. Camelid mucocuta-

neous fibropapillomas: clinicopathologic findings and association

with papillomavirus. Veterinary Pathology 2003; 40: 103–7.

51. Suedmeyer WK, Williams F. Multiple trichoepitheliomas in an

alpaca (Lama pacos). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2005;

36: 706–8.

52. Dukgraaf S, Pusterla N, Van Hoogmoed LM. Rattlesnake enven-

omation in 12 New World camelids. Journal of Veterinary Inter-

nal Medicine 2006; 20: 998–1002.

53. Scott DW, Miller WH Jr, Griffin CE. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal

Dermatology, 6th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2001. pp.

893–4.

54. Clauss M, Lendl C, Schramel P et al. Skin lesions in alpacas and

llamas with low zinc and copper status – a preliminary report.

Veterinary Journal 2004; 67: 302–5.

55. Scott DW, Miller WH Jr, Griffin CE. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal

Dermatology, 6th edn. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 2001.

pp. 641–2.

56. Scott DW, Miller WH Jr. Equine Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA:

W.B. Saunders, 2003. pp. 658–9.

57. http://www.pacapooalpacas.com/NewSite/Articles/animal-hus-

bandry-safley.htm. Accessed July 29, 2010.

58. Scott DW, Miller WH Jr. Equine Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA:

W.B. Saunders, 2003. pp. v–ix, Preface and Acknowledge-

ments.

59. Bond R, Middleton DJ, Scarff DH et al. Chronic dermatophytosis

due to Microsporum persicolor infection in three dogs. Journal

of Small Animal Practice 1992; 33: 571–6.

60. Fairley RA. The histological lesions of Trichophyton mentagro-

phytes var erinacei infection in dogs. Veterinary Dermatology

2001; 12: 119–22.

61. Belknap EB, Dunstan RW. Congenital ichthyosis in a llama. Jour-

nal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1990; 197:

764–7.

62. Castellana MC, Idiart JR. Multifocal renal cystadenocarcinoma

and nodular dermatofibrosis in dogs. Compendium of Conti-

nuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian 2005; 27: 846–

53.

63. Scott DW, Miller WH Jr. Equine Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA:

W.B. Saunders, 2003. pp. 458–67.

64. Scott DW. Color Atlas of Farm Animal Dermatology. Ames, IA:

Blackwell Publishing, 2007. pp. 56, 133, 175.

65. Yeruham I, Braverman Y, Orgad U. Field observations in

Israel on hypersensitivity in cattle, sheep, and donkeys

caused by Culicoides. Australian Veterinary Journal 1993; 70:

348–52.

66. Yeruham I, Perl S, Branerman Y. Seasonal allergic dermatitis in

sheep associated with Ctenocephalides and Culicoides bites.

Veterinary Dermatology 2004; 15: 377–80.

67. Norrdin RW, Krook L, Pond WG et al. Experimental zinc defi-

ciency in weanling pigs on high and low calcium diets. Cornell

Veterinarian 1973; 63: 264–90.

68. Singh AP, Netra PR, Vashistha MS et al. Zinc deficiency in cattle.

Indian Journal of Animal Science 1994; 64: 35–40.

ª 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation ª 2010 ESVD and ACVD, Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 2–16.

15

Skin diseases in the alpaca

69. White SD, Bourdeau P, Rosychuk RAW et al. Zinc-responsive

dermatoses in dogs: 41 cases and literature review. Veterinary

Dermatology 2001; 12: 101–9.

70. Ott EA, Smith WH, Stob M et al. Zinc deficiency in the young

lamb. Journal of Nutrition 1964; 82: 41–50.

71. Masters DG, Chapman RE, Vaughan JD. Effects of zinc defi-

ciency on the wool growth, skin, and wool follicles of pre-rumi-

nant lambs. Australian Journal of Biological Science 1985; 38:

355–64.

72. Suliman HB, Abdelrahim AI, Zakia AM et al. Zinc deficiency in

sheep: field cases. Tropical Animal Health and Production 1988;

20: 47–51.

73. Miller WJ, Pitts WJ, Clifton CM et al. Experimentally produced

zinc deficiency in the goat. Journal of Dairy Science 1964; 47:

556–9.

74. Krumetter-Froetscher R, Hauser S, Baumgartner W. Zinc-respon-

sive dermatosis in goats suggestive of hereditary malabsorption:

two field cases. Veterinary Dermatology 2005; 16: 269–75.

Re´sume´ Cette e´tude re´trospective de´crit 68 cas de dermatose d’alpagas diagnostique´s entre 1997 et

2006 a` l’Universite´ de Cornell. Au cours de cette pe´riode, 40 des 715 (5.6%) alpagas vus en consultation a`

l’hoˆpital universitaire pre´sentaient des le´sions dermatologiques. De plus, les biopsies cutane´es repre´senta-