HUMAN EVOLUTION

Vol.13 - N. 3-4 (229-234) - 1998

M. Henneberg,

Department of Anatomical Sciences,

University of Adelaide, Adelaide

5005,

Australia

V. Sarafis

Centre for Microscopy and

Microanalysis,

The University of Queensland,

Brisbane 4072, Australia

Human adaptations to meat eating

It is argued that Homo sapiens is a habitual rather than a facultative

meat eater. Quantitative similarity of human gut morphology to

guts of carnivorous mammals, preferential absorption of haem

rather than iron of plant origin, and the exclusive use of humans

as the definitive host by Taenia saginata and the almost complete

human specificity of T. solium are used to support the argument.

K. Mathers

Department of Anthropology

University of California, Berkeley,

94720 USA

Keywords: australopithecinae,

Tacniods, parasites, hominids

Introduction

Currently meat of various animals forms a substantial component of the human diet. The

origin and role of meat eating in hominid evolution have been widely debated. There is,

however, no consensus yet in the palaeoanthropological literature on when habitual meat eating

originated nor whether it started as hunting or scavenging (Rose and Marshall 1996 and

following commentary). Gut macro- and microscopic morphology has been seen as reflecting

diet in mammals (Chivers and Hladik 1980). Alas, guts do not fossilise and therefore any direct

evidence for their evolution in hominids is not available. Indirectly, however, it can be

deduced from reconstructions of the skeleton that abdominal contents of australopithecines

were larger, in proportion to their body size, than those of early and modern humans (Aiello

and Dean 1990, Aiello and Wheeler 1995). Inference of meat eating from the Plio/Pleistocene

archaeological record is difficult and results are open to debate. Hominid dentition does not

provide clear indication as to meat eating (Lucas et al. 1985). Trace element (Sillen 1986,

1992) and isotope analyses (Lee-Thorp 1989, Lee-Thorp and Van der Merwe 1993) were used

to determine diet of hominids directly from the fossils. Results may be interpreted as indicating

substantial amounts of animal protein in Pilo/ Pleistocene hominid diet, but they do not agree

well with accepted interpretation of dietary differences between robust australopithecines and

early hominines. Chemical changes taking place in a fossil (diagenesis) also create some

problems (Sillen 1992).

Comparative studies of living humans and animals together with their intestinal parasites

seem to be an appropriate avenue to gain insight into human biological adaptation to meat

eating.

230

HENNEBERG, SARAFIS, MATHERS

Modern human energy intake and gastrointestinal tract morphology will be compared with

those of other extant animals in order to ascertain whether human digestive physiology differs

from that of other primates. Also the evidence from intestinal parasites acquired from food

ingestion and unique to mankind will be discussed in relation to meat eating.

Efficiency of digestion and absorption

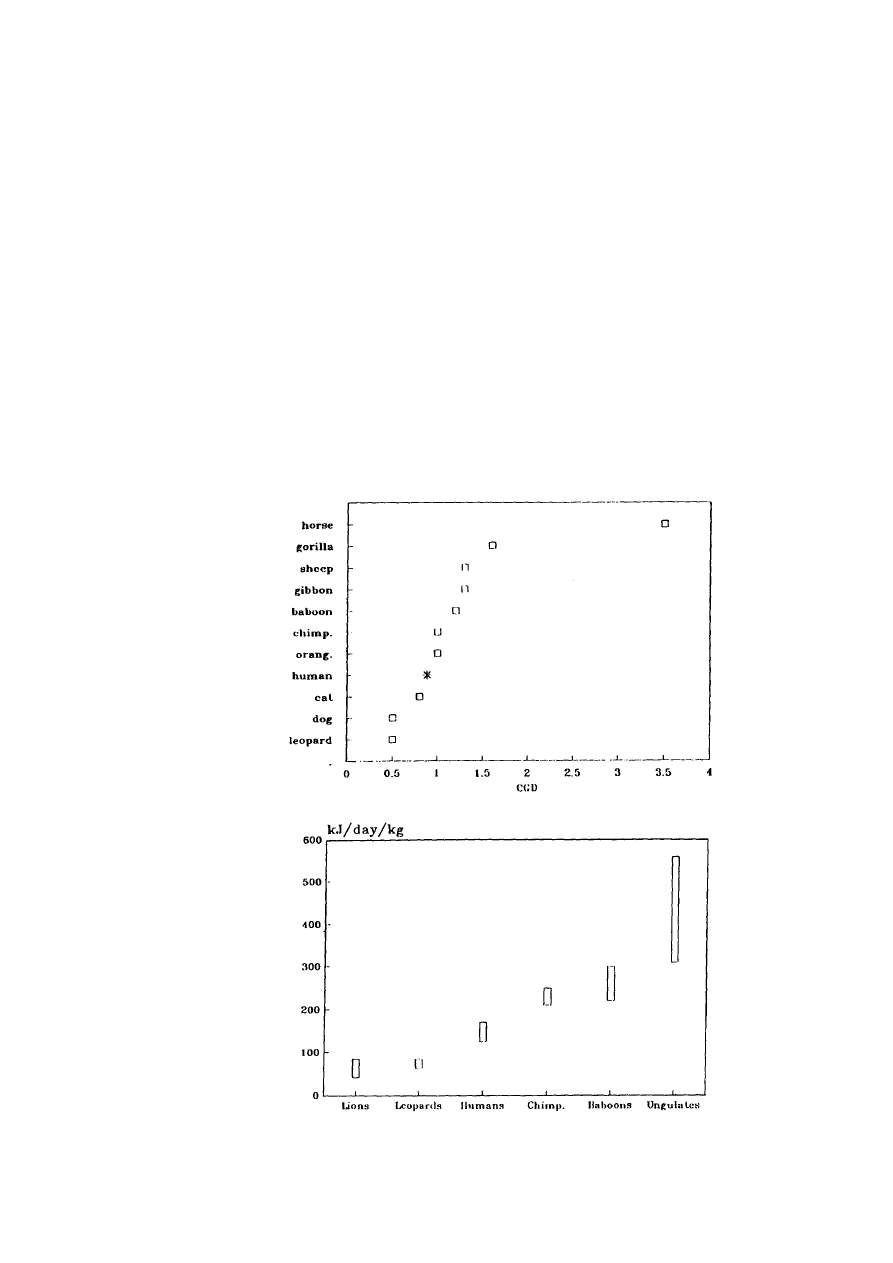

Energy intakes per day per kg of body weight for a range of extant animals are shown in

Figure 1. Carnivore energy requirements were based on food fed to lions and leopards in the

Johannesburg ZOO (N Roux, pers. comm.) and the Krugersdorp Game reserve (M Friedrichs,

pers comm.). Energy intake of baboons and chimpanzees was obtained from Nicolosi and Hunt

(1979); ungulate requirements were given by Belovsky (1987) while FAO standards were used

for humans. Energy intake, in kJ per day per kilogram body mass is the highest for ungulates

(herbivores) and the lowest for carnivores.

Figure 1. Ranges of energy intake (kJ/day/kg) for various extant animals and for humans.

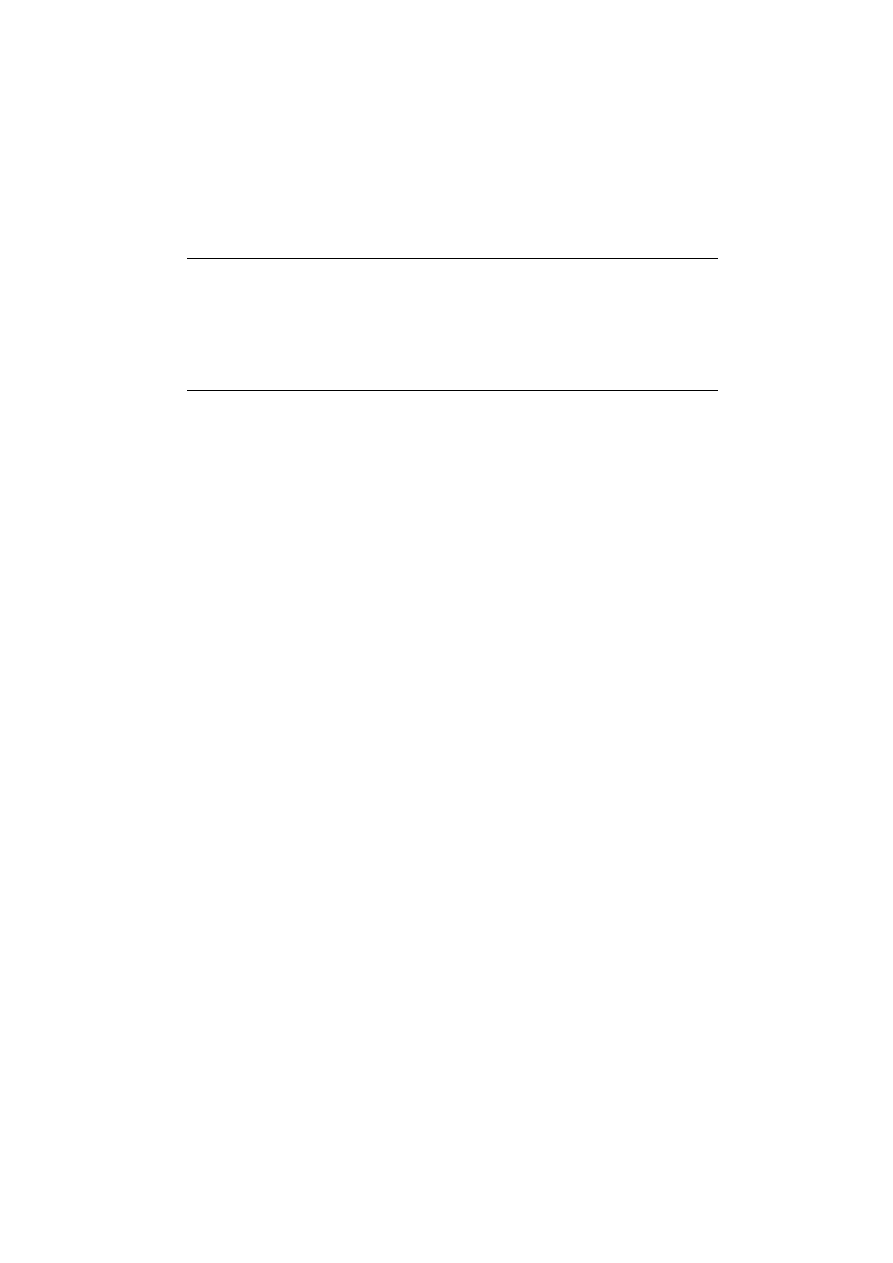

Figure 2. Comparison of the coefficient of gut differentiation (CGD) for various extant animals and for humans. Data for animals

from Chivers and Hladik (1980).

HUMAN ADAPTATIONS TO MEAT EATING

231

TABLE

1.

Quantitative comparison of gastrointestinal tracts of some animals and humans. Data sources described in the text.

Animal intestinal

length

to body length

gastrointestinal surface area

to body surface area

Cattle

20:1

3.0:1

Horse 12:1

2.2:1

Baboon

8:1

1.1:1

Dog 6:1

0.6:1

Human

5:1

0.8:1

Cat 4:1

0.6:1

Chimpanzees and baboons as predominantly plant-eating primates fall between these

extremes. Total food , intake in humans tends to be the lowest of the three primates and closest

to that of carnivores.

Standardised by body mass energy intake is a measure of the efficiency with which the gut

extracts nutrients from the ingested food mass since basic metabolic requirements of all

mammals are similar. Carnivores eat less per kilogram body weight because they are

physiologically and anatomically adapted to a nutrient rich diet.

Physiologically, haem and other porphyrine-iron compounds derived only from meat are

absorbed by humans in preference to ionic iron, whereas herbivorous animals cannot absorb

these compounds and rely on absorption of ionic iron (Bothwell and Charlton 1982). We do not

know whether the other primates absorb haem as selectively as humans do but further

comparisons of absorption in the gut of various primates could be useful to elucidate the issue.

Quantitative morphology of the gastrointestinal tract

McNeil Alexander (1991) has suggested a generalisable model which allows predictions of

gross gut morphology from the size of an animal and its diet. This model suggests that relative

to the body size the gut size should reduce with the shift to a richer diet. In particular, parts of the

digestive system in which processing and digestion of cellulose take place will be reduced. This

model can be applied to hominoids. Quantitative comparisons of gastrointestinal tract

morphology of extant animals confirm differences between carnivores and herbivores and

underline the fact that human gut morphology resembles that of carnivores. Numerical

information on average dimensions of various parts of the human gastrointestinal tract can be

found in more complete textbooks of anatomy (e.g. Williams et al.1995). Data for domesticated

animals are available in the literature (Church and Pond 1988). The gut of a baboon

(Papio

ursinus)

was assessed by our own (MH) dissection of an adult female. The ratio of intestinal

length to body length and the ratio of gastrointestinal surface area to body surface area show

that the human pattern fits between the carnivores (dog and cat) and a baboon (Table 1).

Comparison of the coefficient of gut differentiation as defined by Chivers and Hladik (1980)

echoes the same pattern (Figure 2). The coefficient is defined as a ratio of a sum of the surface

areas of the stomach and the large intestine to the surface area of small intestine. Herbivores -

horse, gorilla and sheep - fall at one extreme while carnivores - leopard, dog and cat - occupy

the other. Gut morphology places humans midway between other primates and carnivores. A

similar differentiation between humans and other primates can be seen in a study of

gastrointestinal allometry in primates (Martin et al. 1985).

2 3 2

HENNEBERG, SARAFIS, MATHERS

Taenioid parasites

Cestodes of the family Taeniidae are parasites of carnivores (Okamoto et al. 1995).

Cestode parasite Taenia saginata uses humans as the only definitive host and T. solium almost

exclusively uses human hosts, although it is sporadically found in monkeys (Grove 1990).

These two taenioids are very closely related species that differ strongly from some other

species of Taenia: pisiformis, ovis, taeniaformis on molecular biology and monoclonal antibody

tests (Harrison and Parkhouse 1989). All human-specific taenioids are exclusively transmitted

through the eating of meat. Intermediate hosts preferred by T. saginata are bovids, ovids, and

caprids, while T solium preferential intermediate hosts are suids, mainly the domestic pig

(Miyazaki 1991). It is strongly suggested that mammalian hosts and their parasites undergo

close co-evolution and that speciation in the parasites lags behind speciation in hosts (Hafner and

Nadler 1988). C Joyeux and J-G Baer (1961) in their review of cestodes mention meat eating by

humans as the cause of infection by these two Taenia species. This indicates the habitual eating

of meat by humans and differentiates humans from chimpanzees who also hunt animals and eat

meat. They also draw attention to the stricter definitive host status of humans for Taenia

saginata than for T. solium. A third form of Taenia has recently been claimed as having humans

in Asia as its only definitive host. It is still uncertain whether it is a separate species or a

subspecies of T. saginata (Garcia and Bruckner 1997), but it may be of considerable antiquity .

Taenia species parasitising humans are related to those parasitising dogs. The +100

thousand years of association between humans and dogs recently described by Vila et al. (1997)

may suggest that humans acquired taenioid parasites initially from dogs sufficiently early to

allow their speciation.

Pongids are not definitive host for any taenioid cestode. This suggests that the three

specifically human taenioids have evolved after the separation of hominids from the common

ancestor. Meat eating in chimpanzees has recently been suggested to be a regular occurrence

(Teleki 1973, Wrangham and Van Zinncq Bergmann Riss 1990, McGrew 1992). The lack of

meat-transmitted parasites in pongids, however, suggests that the frequency of meat ingestion by

pongids is so low that it cannot support reproductive success of a muscle dwelling cysticercoid.

It is well known that because hominid dentition cannot penetrate the hide of larger

mammals, meat eating had to be coupled with the use of weapons and tools. Cooking may have

also been of importance. Human tenioid cysticerci occur with the highest frequency in animal

masseter muscles and in the heart, while their frequency is lowest in trunk muscles (Sprehn

1932, Miyazaki 1991). Since thorough cooking

is

supposed to kill cysticerci it may be

suggested that selection caused their preferential placement in those parts of the carcass that are

relatively less likely to be thoroughly cooked. T. saginata cysticerci have been shown to survive

in about 2 % of beef cuts used for cooking as "suya" and consumed at a stage considered

normal for human consumption in Nigeria (Mosimabale and Belino 1980).

Conclusions

The comparative anatomy and physiology pattern indicates that modern humans are well-

evolved meat eaters but we do not know the time scale necessary for such changes to have

occurred in human biology. Some evidence that meat eating has a long history in the human

lineage is provided by comparisons of Sr/Ca ratios and carbon isotope ratios from

HUMAN ADAPTATIONS TO MEAT EATING

233

hominid fossils (Sillen 1986, 1992, Lee-Thorp 1989, Lee-Thorp and Van der Merwe 1993). It

seems that on these indicators robust australopithecines and early

Homo

differ from baboons and

fall in between the herbivore and carnivore ratios. This may point to significant meat ingestion as

part of an omnivorous diet already in robust australopithecines and early Homo. Therefore we

may postulate that physiological, anatomical and behavioural adaptations to habitual reliance on

meat eating occurred in the hominid lineage at the australopithecine stage.

References

Aiello LC and Dean C (1990) An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy. Academic Press, London. Aiello LC and

Wheeler P (1995) The expensive tissue hypothesis. Curr. Anthrop. 36:199-221.

Belovsky GE (1987) Foraging and optimal body size: An overview, new data and a test of alternative

models. J Theor Biol. 129: 275-287.

Bothwell TH and Charlton RW (1982) A general approach to the problems of iron deficiency and iron overload in

the population at large. Seminars in Haematology 19: 54-67

Chivers DJ and Hladik CH (1980) Morphology of the gastrointestinal tract in primates: comparisons with other

mammals in relation to diet. J Morphol 166:337-386

Church DC and Pond WC 1982 Basic Animal Nutrition and Feeding. 3rd ed., J Wiley, New York.

Garcia LS and Bruckner DA (1997) Diagnostic Medical Parasitology, 3rd ed., American Soc. for Microbiology Press,

Washington, DC.

Grove DI (1990) A History of Human Helmintology, CAB International, Wallingford

Hafner MS and Nadler SA (1988) Phylogenetic trees support the coevolution of parasites and their hosts. Nature

332: 258-259.

Harrison LJ and Parkhouse RM (1989) Taenia saginata and Taenia solium: Reciprocal models. Acta Leiden. 57:

143-152

Joyeux C and Baer J-G (1961) Classe des cestodes, in: Grasse P-P (ed.) Traite de Zoologie, vol. IV, Masson et Cie.,

Paris, pp 347-560

Lee-Thorp JA (1989) Stable Carbon Isotopes in Deep Time: The Diets of Fossil Fauna and Hominids, PhD Thesis,

University of Cape Town

Lee-Thorp JA and Van der Merwe NJ (1993) Stable carbon isotope studies of Swartkrans fossils, In Brain

CK (ed) Swartkrans: A Cave's Chronicle of Early Man, Transvaal Museum Monograph 8: 251-256 Lucas PW,

Corlett RT, and Luke DA (1985) Plio-Pleistocene hominid diets: An approach combining

masticatory and ecological analysis. J. Hum. Evol. 14:187-202

McNeil Alexander R (1991) Optimisation of gut structure and diet for higher vertebrate herbivores. Phil. Trans. R.

Soc. Lond. B 333: 249-255

Martin RD, Chivers DJ, Maclarnon AM, Hladik CH (1985) Gastrointestinal allometry in primates and other

mammals. In Jungers WL (ed) Size and Scaling in Primate Biology, Plenum Press, New York, p. 61-89 McGrew C

(1992) Chimpanzee Material culture Implications for Human Evolution. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

Miyazaki I (1991) An Illustrated Book of Helminthic Zoonoses. IMFJ, Tokyo

Mosimabale FO and Belino ED (1980) The recovery of viable Taenia saginata cysticerci in grilled beef "suya" in

Nigeria. Int. J Zoonoses 7: 115-119.

Nicolosi RJ and Hunt RD (1979) Dietary Allowances for Nutrients in Non-Human Primates. In Hayes KC (ed):

Primates in Nutritional Research, Academic Press, New York, p.11-37

Okamoto M, Bessho Y, Kamiya M, Kurosawa T, Hori T (1995) Phylogenetic relationships within Taenia

taeniaformis variants and other taeniid cestodes inferred from the nucleotide sequence of the cytochrome c oxidase

subunit I gene. Parasitology Research 81: 451-458.

Rose L and Mashall E (1996) Meat eating, hominid sociality and home bases revisited. Curr. Anthrop. 37: 307-338.

Sillen A (1986) Biogenic and diagenetic Sr/Ca in Plio-Pleistocene fossils in the Omo Shungura formation,

Palaeobiology 12: 311-323.

Sillen A (1992) Strontium-calcium (Sr/Ca) of Australopithecus robustus and associated fauna from Swartkrans. J Hum

Evol 23: 495-516.

234

HENNEBERG, SARAFIS, MATHERS

Sprehn CEW (1932) Lehrbuch der Helmintologie, Gebruder Borntrager, Berlin

Teleki G (1973) The Predatory Behavior of Wild Chimpanzees. Bucknell Univ. Press, Lewisburg.

Vila C, Savolainen P, Maldonado JE, Amorim IR, Rice JE, Honeycutt RL, Crandall KA, Lundeberg J,

Wayne RK (1997) Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog, Science 276: 1687-1689 Williams PL, Bannister LH,

Berry MM, Collins P, Dyson M, Dusek JE Ferguson MWJ (1995) Gray's Anatomy. 38th ed., Churchill Livingstone,

London .

Wrangham RW and Van Zinnicq Bergmann Riss E (1990) Rates of predation on mammals by Gombe chimpanzees 1972-

1975, Primates 31: 157-170.

Received October 2, 1997

Accepted December 20, 1997

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

kraatz learning by association interorganizational networks and adaptation to environmental change

Sosnowska, Joanna Adaptation to the institution of a kindergarten – does it concern only a child (2

Psychological essentialism and the differential attribution of uniquely human emotions to ingroups a

Nutrition Keys to Healthy Eating

A Guide To Healthy Eating And Losing Weight

Block Walter Is there a Human Right to Medical Insurance

Love; Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Locke on Human Understanding

Pieniądze to nie wzystko Operon 2010 PEG2010-Human-kartoteka

Introduction To Human Design

Intro to Human Sexuality

Introduction to Human services

adaptacja wybranego utworu 85, szkolne, Język polski metodyka, To lubię, To lubię - scenariusze

How To Draw Comic Human

Design Guide 11 Floor Vibrations Due To Human Activity

więcej podobnych podstron