Spanish

securitisation

NEW REGS CHANGE

LANDSCAPE

PLUS:

€

Bond Liquidity Survey

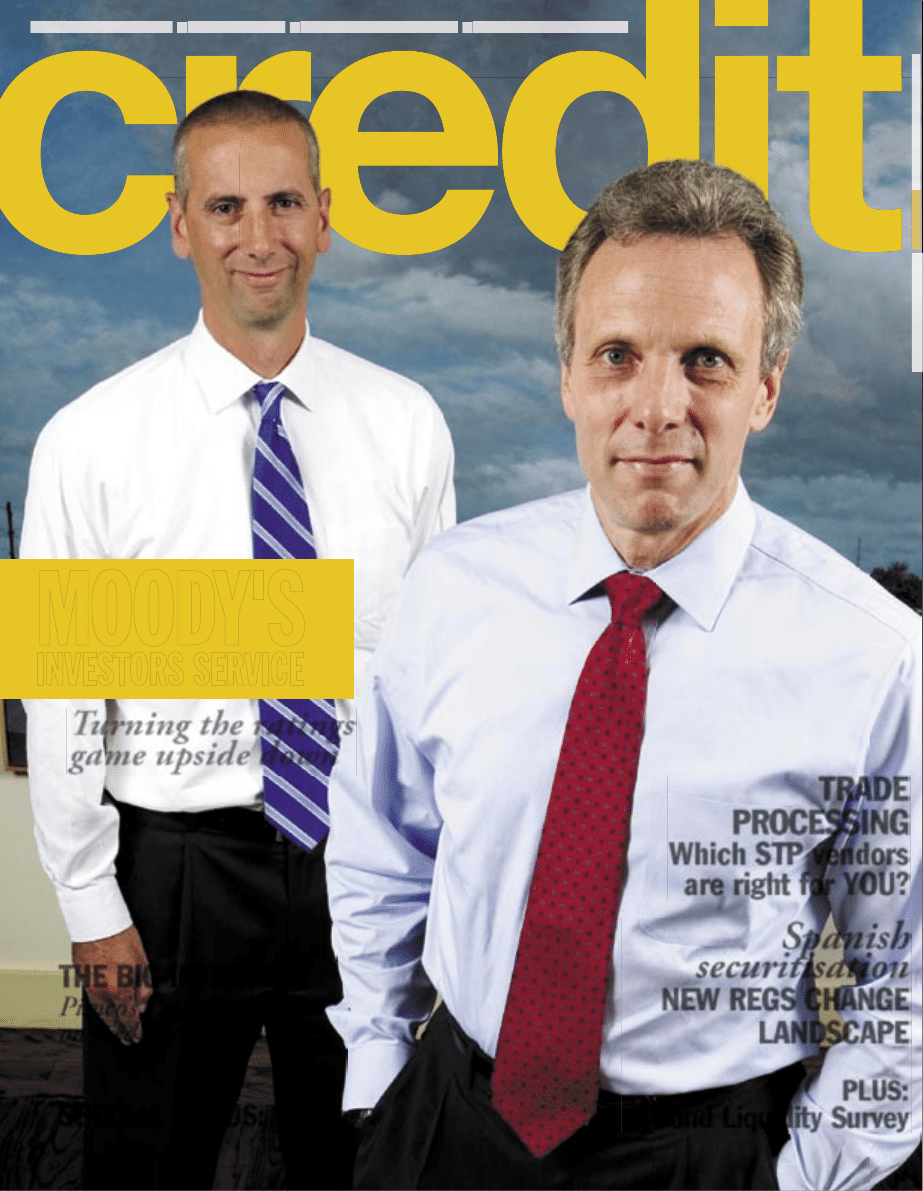

THE BIG INTERVIEW

Pimco’s Peter Bentley

on credit valuations

SPECIAL FOCUS:

Korea

TRADE

PROCESSING

Which STP vendors

are right for YOU?

MOODY'S

INVESTORS SERVICE

Turning the ratings

game upside down

www.creditmag.com

E

nron’s spectacular descent into the biggest corporate

bankruptcy ever seen in the US surprised everyone. Not

least the rating agencies that were still tipping the energy

firm as an investment-grade credit four days before it filed for

bankruptcy protection on December 2, 2001.

Their collective failure to rate Enron’s creditworthiness

adequately in the weeks leading up to its collapse earned the

rating agencies the lasting enmity of US lawmakers, who have

been dying to get their hands on the right to regulate them

ever since. “The credit raters – despite their unique position to

obtain information unavailable to other analysts – were no more

astute and no quicker to act than others,” said US senator Joe

Lieberman, who chaired the governmental committee looking

into Enron’s collapse.

Yet the signs of the energy firm’s imminent demise were there

to be seen clearly in the markets several weeks before Enron’s

Chapter 11 filing, which left creditors holding some $16 billion

of defaulted debt.

On October 22 that year, Enron’s stock price dropped 20%

to $20.65 per share, and five-year credit default swap (CDS)

spreads jumped 20% to 48 basis points, after the Securities &

Exchange Commission announced it was looking into the firm’s

accounting practices. When Enron announced it had overstated

profits by nearly $600m over five years on November 8, the stock

was at $8.41 and CDS spreads were at 133bp. By the time Moody’s

and S&P finally downgraded Enron to junk status on November

28, its stock was worth little more than a dollar per share.

The moral of the story, ‘don’t ignore the market’, was a hard

lesson for the rating agencies to learn. Five years on, one agency,

Moody’s, has something to show for it.

Moody’s, the oldest rating agency, and alongside Standard &

Poor’s one of the two largest agencies by market share, has devel-

oped a set of ratings indicators derived from market signals. These

may be used as a counterpart to Moody’s ‘normal’ ratings, which

are based on analysts’ views of an issuer’s creditworthiness.

The indicators, dubbed ‘market implied ratings’ (MIR), high-

light discrepancies between an issuer’s credit rating – in essence,

the rating agency’s assessment of a company’s financial situation

and future outlook – and the market’s view of that issuer – which

is in effect the sum total of the expression of all bond, credit

derivatives and equity investors’ views on that company.

The concept is quite simple. Using data derived from all the

issuers it rates, Moody’s has worked out an average bond spread

for certain ratings categories. The MIR team then analyses a

given issuer’s bond spreads to give it a bond implied rating. For

example, the median credit spread for five-year B2 rated bonds

might be 377 basis points over Treasuries. If Acme Inc, a B2

rated credit, is trading at 168 basis points – the median spread

of five-year Ba1 rated bonds – its bond implied rating would be

Ba1. As this is four notches above its actual rating, it is said to

have a ratings gap of +4.

Ford Motor Company is a good example of an issuer’s bonds

trading below its Moody’s rating: as of September 1, Ford’s rat-

ing was B2, while its bond implied rating was Caa1, giving it a

ratings gap of -2. In other words, Ford was then trading two

notches below – or cheap to – its rating.

Synthetic feature

To add extra dimensions to the implied ratings, Moody’s applies

the same analysis to an issuer’s credit default swaps, using median

five-year CDS spreads, and also examines equity implied ratings.

Determining these is more complex, and is based on Moody’s

KMV EDF model, extracting credit risk information from an

issuer’s equity price by assessing expected default frequency.

By highlighting differences between an issuer’s implied rating

and its actual rating, the MIR team is able to flag up different

types of credit risk. They identify default candidates: the agen-

cy’s research shows that default rates are significantly higher for

issuers whose securities are trading with negative gaps compared

with their Moody’s rating. It might seem like something of a no-

brainer that securities the market takes a dim view of are more

likely to default; but what is surprising is the degree to which it

is true.

Using a data set of 2,900 issuers, with 180,000 observations

gathered between January 1, 1999 and February 28, 2006, the

one-year default rate for B2 rated issuers trading two notches

below their Moody’s rating was a massive 17.82%. That com-

pares with a default rate of 3.61% for issuers trading flat to their

Moody’s rating; or 0.59% for those trading two notches rich. In

other words, if you held a portfolio of bonds that were trading

two notches cheaper than the Moody’s rating, you should expect

nearly a fifth of them to default within a year.

MIR can also be used to predict potential ratings changes. An

issuer trading three notches below its Moody’s rating is looking

at about a 25% chance of downgrade over a one-year horizon,

according to MIR data from the same data set. And when you

drill down further into specific ratings categories, the probability

of downgrade can increase further. The most extreme example

As the debate rages over the usefulness of credit ratings, Moody’s unveils

a set of credit risk indicators derived from market movements. Will ‘market

implied ratings’ silence the agencies’ critics?

Nikki Marmery

investigates

rating process

Upgrading

the

P R O F I L E

1

credit

OCTOBER 2006

P R O F I L E

credit

OCTOBER 2006

2

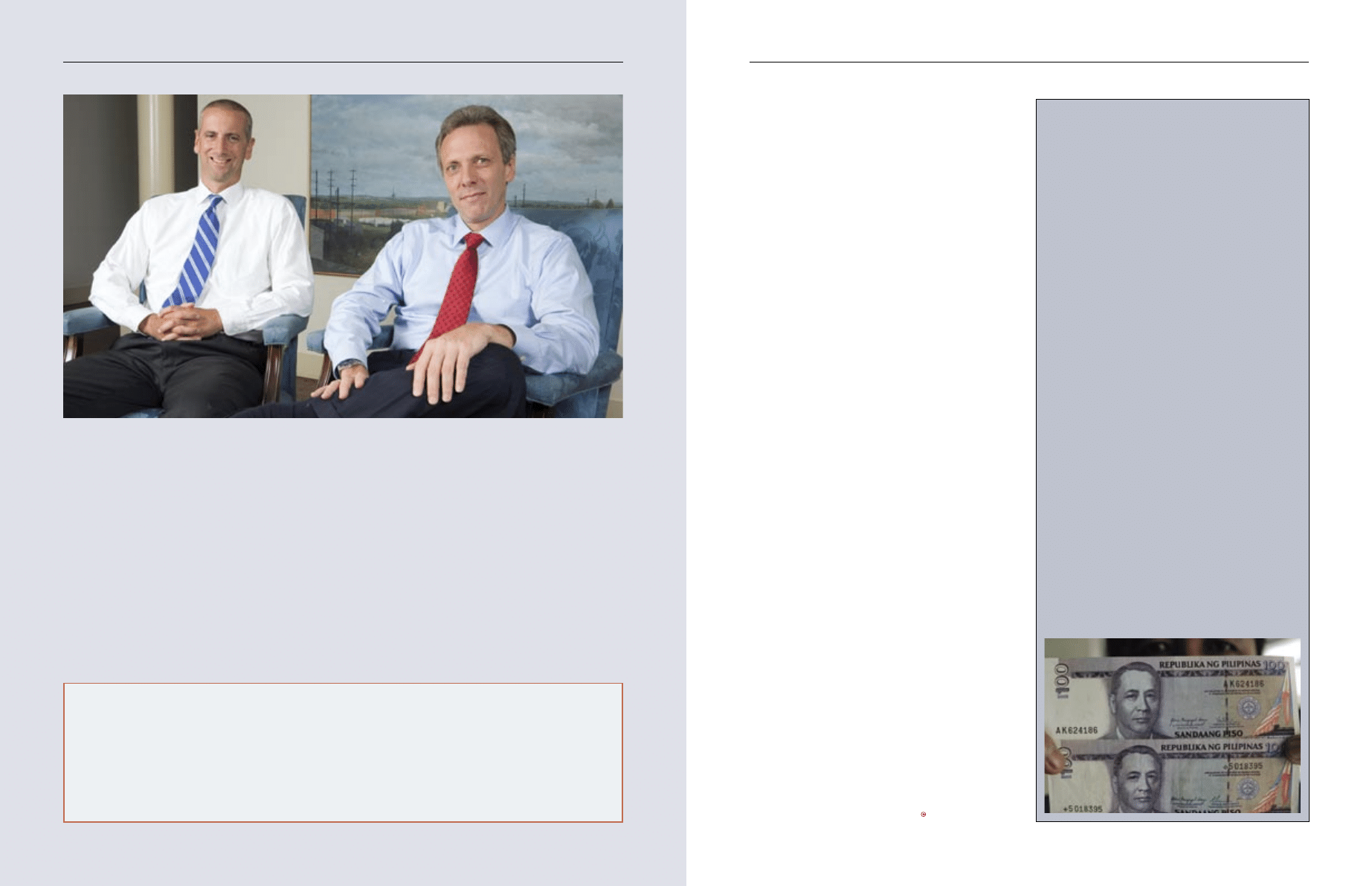

PHOTOGRAPHY

: AMY FLETCHER

Moody’s MIR team: (from left) Simon Jiang, Chris Lam, Dan Russell, Robert Eckerstrom, David Munves, Njundu Sanneh and Tipanee Pipatanagul

www.creditmag.com

Moody’s rolled out a form of the product to its analysts in

2001. From the start, the agency used implied ratings as a guide

to the companies they rated, rather than factoring them in to

their ratings judgments. “As one of the analysts said to me,”

reports Munves, “it makes sure they ask the right questions in

the right way at the right time.”

Three years later, Moody’s rolled out MIR to customers. At

that point it became clear that MIR needed further research on

its uses to help customers interpret the data, and the agency

turned to David Munves, a credit strategist with more than two

decades of experience in the fi xed-income groups of Lehman

Brothers and Standard & Poor’s, to lead the team.

“I joined in December 2004, some months after it was rolled

out to customers,” says Munves. “They wanted to know, ‘what’s

the signifi cance of this? Is it something I should act upon? Is that

a high level of default risk?’ Without the research, no one really

had the answers.”

Team-building

Munves was joined by quant specialist Simon Jiang from another

part of Moody’s research team, and in November 2005 by assist-

ant vice-president Keith Gudhus and research associate Chris

Lam. Gudhus’s background was in trading, having worked in

BNP Paribas’ loan syndication and trading department, and

before that at the Gelber Group, where he traded corporate

debt. Lam researches the MIR database and contributes to the

monthly comments; he was previously at private equity fi rm CAI

Managers in New York where he specialised in buyouts, restruc-

turings and acquisitions.

Vice-president Robert Eckerstrom, who with Gudhus writes

market-orientated research and researches long-term projects,

joined in July. He previously worked for the Government of Sin-

gapore Investment Corporation, where he was an interest rate

portfolio manager and co-managed a credit portfolio.

Moody’s also hired two emerging markets specialists earlier this

year: economists Tipanee Pipatanagul, who monitors Asian and

emerging European economies, and Njundu Sanneh, who looks

at MIR-related credit market trends in regional markets. Pipatan-

agul previously worked as an economist at the US Treasury, and

Sanneh transferred from Moody’s Credit Trends service, where he

provided emerging markets commentary.

The newly formed team each saw the potential for the product

from the perspective of their diverse backgrounds. “Putting my

trading hat on,” says Gudhus, “I thought, ‘this would really help

me with my trading ideas.’”

Still, all this leads to a clear conundrum. If credit risk infor-

mation derived from market movements is more accurate

than Moody’s analysts’ assessments, then what’s the point of

analysts’ assessments of credit risk? Shouldn’t the price of a

security be a function of its creditworthiness – not the other

way round? Isn’t MIR an admission that the naysayers are right

– and Moody’s ratings, along with those of the other agencies,

are untimely and inaccurate?

“They are different signals,” affi rms Russell. “They both serve

a role and the market has spoken that it wants to continue to use

our ratings in a broad manner.”

Serving as a benchmark for the implied ratings, ‘traditional’

ratings are useful, because it’s the discrepancy between the two

that delivers the signals. “We see them

as complementary,” says Russell. “We

think we can play a unique role in

doing rigorous research into mar-

ket signals relative to ratings so we

can move from instinct-based dis-

cussions and conclusions to more

empirically based discussions of

how credit ratings behave.”

But is it necessary for market

implied ratings to function rela-

tive to Moody’s ratings? Could not

default probability be derived from

absolute price move-

ments, irrespective

of rating gaps?

One

credit

analyst at an

investment

bank in

“A lot of the time people have intuition, but

empirical data doesn’t back it up. MIR

helps investors avoid opportunities to buy

expensive paper”

David Munves, Moody’s

P R O F I L E

is B rated issuers, for whom there is a higher than 50% chance of

downgrade over the next year for all issuers trading three notches

or more below their Moody’s rating.

A third application of the tool is relative value analysis. By

comparing relative implied ratings moves, the data can signal

which bonds are likely to rise or fall against the broad market

in the coming year – effectively delivering buy and sell signals

for investors benchmarked against indices. The data shows, for

example, that bonds trading with a ratings gap of -3 are more

than 50% likely to see their bond implied rating rise over the

next 12 months – indicating an outperformance of the broad

market. Conversely 65% of bonds trading three gaps rich to their

Moody’s rating should expect to see their bond implied rating

decrease over the coming year, indicating underperformance

versus the market.

That’s a refl ection of the typical cycle of the market, says David

Munves, the managing director of credit strategy research at

Moody’s in New York, who leads the MIR team. “Fund manag-

ers will rotate out of expensive names and into cheap names; it’s

the traditional pattern of issues being oversold, stabilising and

coming back.”

Bonds with the positive ratings gaps are the ones investors

want to avoid in order to outperform the index. “Holding a

portfolio of bonds here, you’ll have a lot that will lose value

against the benchmark,” he says.

It’s in this relative value analysis that MIR is at its most useful.

It means a trader is able to back up his intuition with cold, hard

facts as to whether a credit really is as cheap as it ‘feels’. “A lot of

the time people have intuition, but empirical data doesn’t back it

up. How many notches exactly is it cheap? It looks like it’s trad-

ing cheaply, but has it become more expensive over time relative

to the market? MIR helps investors avoid opportunities to buy

expensive paper,” says Munves.

It also helps traders pick out the ‘biggest’ trading signals from

a mass of information. Autos traders for example might know

the ins and outs of Ford and GM spread movements; but with

75 rated names in the sector, they are likely to have less intuitive

expertise on the less liquid names. This makes the tool particu-

larly valuable for supervisors and risk managers.

“How well does a boss know what’s going on?” asks Munves.

“They need all the help they can get to stay on top of 300–400

names. With MIR, it’s very easy to get those names uploaded,

look at ratings gaps and get email alerts when ratings gaps appear.

It helps managers keep an eye on large number situations, which

is how Moody’s analysts use it. Information overload is killing

people. MIR picks out what’s important.”

Gestation period

The roots of Moody’s market implied ratings were growing long

before accounting scandals such as Enron’s so clearly demon-

strated their value. “Since time immemorial, Moody’s has gotten

calls from customers saying, ‘you’ve got this thing rated like a B3,

but it’s trading like a B1. What’s going on?’” says Dan Russell,

the managing director responsible for new business initiatives at

Moody’s in New York.

Towards the beginning of this decade, various factors conspired

to make the idea of extracting credit risk from price information

more viable: the wider use of the Merton approach to analys-

ing default risk from equity market information; the emergence

of CDS data, enabling the use of risk signals from this market;

and the availability of traded levels for corporate bonds from the

Trace reporting engine.

“We use it to look for credits that may be

deteriorating so we can make our credit

risk offi cers aware of them,” says one user

of Moody’s market implied ratings who

works in the internal credit risk depart-

ment of a major investment bank in New

York. “We’ve built our own system linking

in all our exposures that alerts us of big

ratings gaps developing.”

Watching ratings gaps evolve helps the

bank act faster in dumping bad credits,

explains this user. “If you look at some of

the auto names in particular – say [auto parts provider] Dana Corp,

with a ratings gap of six – you can see the ultimate crash landing of

that credit developing.”

Dana Corp declared bankruptcy on March 3 this year.

“It’s like the canary in the coalmine: a sign that it’s time to get out

of the credit,” he says.

But credit risk offi cers are looking for

potential upgrades as well as downgrades,

he adds. If market implied ratings signal a

credit is heading for an upgrade, the risk

offi cer could free up the economic capital

set aside against it for another area.

These types of clients – as opposed to

investment managers looking for trad-

ing ideas – might also be using a similar

tool developed by Riskmetrics Group,

a risk management software fi rm spun

out of JPMorgan in 1998. CreditGrades is

an equity-based model for assessing the credit quality of publicly

traded companies. The model is used by Deutsche Bank, Goldman

Sachs and JPMorgan. It diff ers from Moody’s market implied ratings

in that it assesses default probabilities unrelated to credit ratings.

It also focuses purely on credit risk information derived from the

equity markets.

3

credit

OCTOBER 2006

P R O F I L E

The canary in the coalmine: How MIR acts as an early warning system

CORBIS

www.creditmag.com

have happened had an investor bought and sold bonds based

on patterns of behaviour revealed by MIR data in the context

of the market environment of the time. For example, the paper

demonstrates that in 2000 – a “horrific” year for the corporate

bond markets, says Munves – you were better off buying expen-

sive bonds (those trading rich to their Moody’s rating): the ‘+2’

portfolio returned 6.64%. In every year after that, buying rich

bonds proved to be a losing strategy. And in the best year for

corporate bonds – 2003 – “it was a real losing proposition”: the

‘+2’ portfolio returned -19.68%.

‘Super implied ratings’

The team is also looking into what gives more accurate indica-

tors: implied ratings derived from bond spreads, CDS spreads

or equities. Early indications are that the CDS market is the

most efficient, probably because it’s a liquid two-way market,

says Munves. Once the analysis is complete, the team hopes to

determine a ‘super implied rating’ derived from an optimum

weighting of all three indicators.

Other long-term research studies include a project looking at

past leveraged buyouts and working out whether bond and equity

implied ratings can be used to identify risky LBO situations.

As such, MIR is looking at significant expansion. It’s tripled

the number of firms using MIR to “north of 500” over the past

year, says Russell. “We’ll probably double staff size before the

year is over, and expand in London. We expect rapid growth.”

Which leads us to one extreme scenario: what happens if

everyone started to buy into Moody’s market implied ratings?

Would the market end up trading off highly leveraged market

signals? Bonds trading cheap to their Moody’s rating being sold

off, sending the spreads wider, and making them even cheaper

to their Moody’s rating – thus heightening the signal to sell?

Bonds trading rich being bought, thus tightening their spreads

and exacerbating their positive ratings gap to Moody’s rating?

Russell, however, isn’t concerned about this nightmare vision

of the future. “The good news about markets is it’s hard to find

10 people who agree on anything,” he says. “Even if everyone

did [use market implied ratings], they would interpret the out-

put differently.”

A credit risk manager, for example, focuses on the default rate

of entities, which for a portfolio of 100 B2 bonds with -2 rat-

ings gaps would be 17.42%. As a result he would likely buy

protection in the CDS market against these names. However

an active portfolio manager would take a different view: “He

would assume he is a superior name-picker,” explains Munves,

“so would be able to hold a portfolio of cheap bonds and have

a default rate much lower than the market average. He would

likely sell CDS protection.” Thus the names for which protec-

tion would be bought or sold would vary according to the views

of the participants.

This underlines the point that Munves and Russell keep com-

ing back to: “What we are saying is that MIR data is an initial

screening tool,” says Munves. “People then have to make their

investment or risk decisions, as always.”

Case study: MIR raises alarm on Philippine debt

Emerging markets is one of the new project areas Moody’s MIR

is looking into, after the addition of economists Tipanee Pipatan-

agul and Njundu Sanneh earlier this year. One early example of

the team’s work in this area is a recent study on the Philippines.

Financial markets in the country enjoyed a strong rally over the

summer on the back of the government’s improving fiscal situ-

ation, expectations of an end to US and local rate hikes and the

return of foreign inflows to the country.

Against such a backdrop, the Philippines Composite Equity

index rose 13.4% between June 14 and August 16, after a sell-off

in spring brought it crashing down 20.2% from its record high of

2,589 on May 8. The Philippine peso rallied 4% against the dollar

over the same period.

Credit investors looking for opportunities in emerging mar-

kets might be buoyed by such market optimism and see solid

investment potential in the country. But a warning signal from

Moody’s MIR prompted the agency to advise investors to “curb

their enthusiasm” on the sovereign.

It noted on August 18 that bond implied ratings for Philippine

issuers rose by one notch between the end of June and August

15 to a rating of Ba2, taking them to two notches above the sov-

ereign’s actual Moody’s rating of B1. As issuers with bond implied

ratings gaps of two notches tend to underperform over a 12-

month view, Moody’s cautioned investors on Philippine debt.

Qualitative factors back up that cautious view, says Pipatanagul.

In particular the government’s exceptionally high public-sector

debt makes the country highly vulnerable to shocks. “Although

Moody’s recognises that the country’s strengthened external

payments position provides a buffer to transitory shocks or

policy mis-steps, this is not enough to significantly reduce the

country’s debt ratios,” she says. “Even assuming a best-case sce-

nario for fiscal reform this year, the ratio of national government

and non-financial public sector debt to revenue will likely stand

at around 400% at the end of 2006, a level that is well above that

of similarly rated countries.”

Political risk ahead of congressional elections in May 2007 is

also an issue, she notes.

credit

OCTOBER 2006

6

CORBIS

P R O F I L E

London thinks so: “To say the market is implying a particular

rating is egocentric: it breaks everything down as though the rat-

ing was the common language of the credit. What the market is

doing is implying a default probability.”

But there’s another, more compelling argument in favour of

Moody’s market implied ratings: stability. Precisely because they

don’t change with every news-related market movement, they

serve as a more stable indication of longer-term risk, making

them just as valuable to investors, argue Munves and Russell.

Market-based metrics give you “more refined signals”, says

Munves, “but there’s an offset, and the offset here is volatility.

Markets move faster, they’re more volatile, and they’re wrong

on occasion.”

Around 90% of Moody’s market implied ratings, for example,

change in the course of one year, and some 76% reverse that

move during the next 12 months. By comparison around 20% of

Moody’s ratings change throughout a year, with a reversal rate

of just 1%.

Delphi is an example of why an investor would want to keep

both sets of ratings in mind. Earlier in this decade, bond implied

ratings of the then Baa2 rated US auto parts manufacturer were

regularly trading two notches higher – at the level of an A3

credit. By February 2002, the bond implied rating sank a notch

below its Moody’s rating to Baa3, before swinging back to the

Moody’s rating and below again later that year. The Moody’s

rating had remained unchanged throughout. “Markets often

overshoot and come back to the Moody’s rating,” says Russell.

“The question is: how do you use the two together to maximise

the value of both?”

That, of course, was before Delphi’s default in October 2005.

As it stumbled headlong down the path to default, the Moody’s

rating lagged the market indicators – but only just.

Now the MIR team is focusing on new projects. A portfolio

paper is in the pipeline, the result of a back-testing exercise to

examine what happened to portfolios of bonds grouped by their

ratings gap over the past five years. The results reveal what would

Issuer

Sector

Market implied rating

Probability of default

Probability of downgrade

1

HCA

Healthcare

Caa1

(Ba2)

21.5%

(1.8%)

48.4%

(16.1%)

2

Ford Motor Company

Autos

Caa1

(B2)

17.4%

(5.5%)

35.4%

(15.7%)

3

Abitibi-Consolidated

Pulp & paper

Caa1

(B1)

10.6%

(2.7%)

35.9%

(18.8%)

4

Beazer Homes USA

Construction

B3

(Ba1)

7.1%

(0.8%)

47.6%

(17.5%)

5

Fairfax Financial Holdings

Financial services

Caa2

(Ba3)

2.9%

(1.3%)

42.6%

(18.7%)

N.B. Figures in

RED

are ‘market implied’; figures in BLACK

are according to Moody’s actual rating

Beware of the dog: next year’s likely defaults and downgrades

P R O F I L E

5

credit

OCTOBER 2006

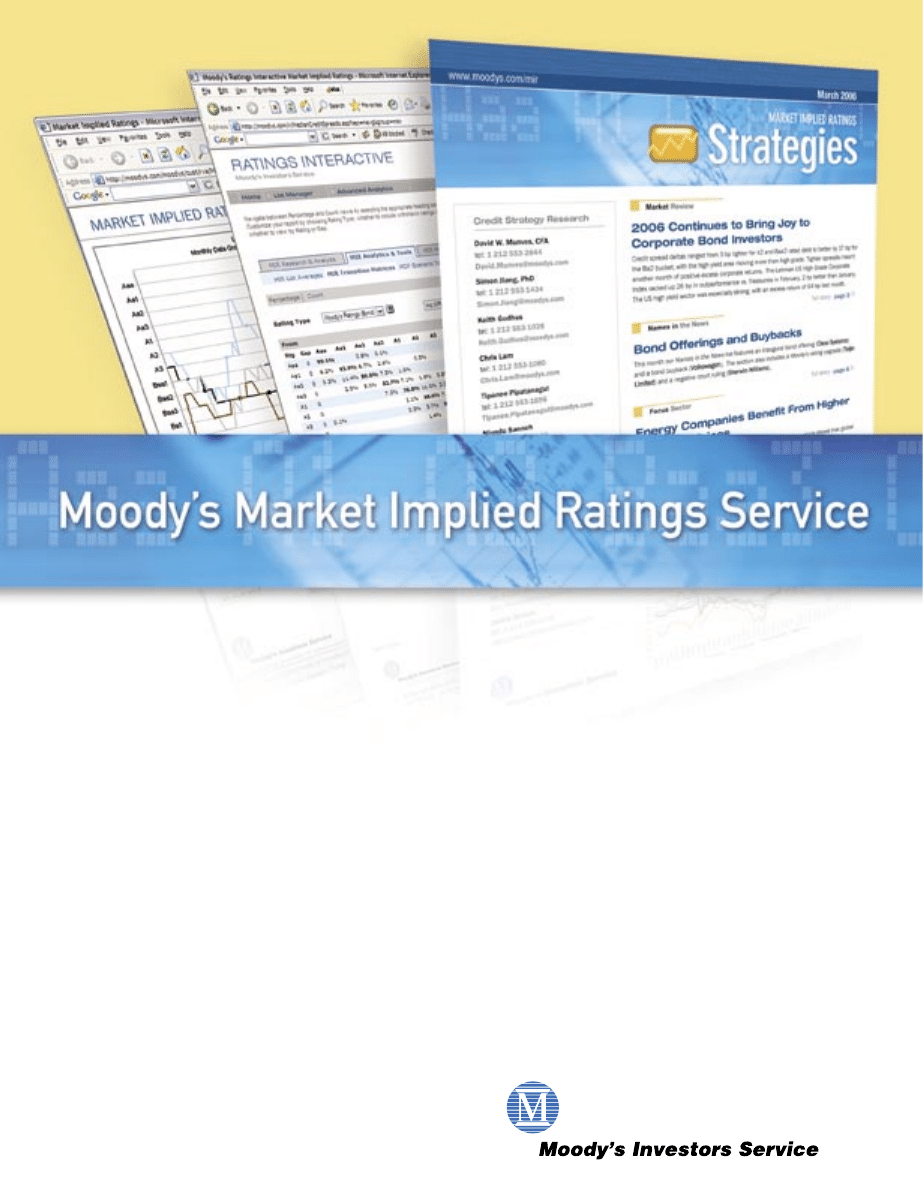

��������

���������������������������

��

�

����������������������������������������������������������������

�������������������������������������������������

�����������������������������������������������������������

�

� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

� �������������������������������������������

�

� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

� ����������������������������������������������

�

� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�

� �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�

� ��������������������������������������������������

�������������������������������������������������� �����������

�

����������������

�

����������������������

�

�����������������

�

�����������������

�

����������������������������

�

�

�

��

��

��

���

�

�����������������������������������������������������

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

ARTICLE SUSPENSION STRUT FRONT REPLACE INSTALL

252550982 GFI Submission Re Credit Suisse QPAM Waiver Hearing

articles ćw

Ziba Mir Hosseini Towards Gender Equality, Muslim Family Laws and the Sharia

Articles et prepositions ex

pa volume 1 issue 2 article 534

article CoaltoLiquids Hydrocarb Nieznany

KasparovChess PDF Articles, Sergey Shipov The Stars of the Orient Are the Brightest Ones!

article

ARTICLE MAINT INSPECTION ENGINE

klucz articles, 2008-2011 (Graduates), Gramatyka opisowa

ARTICLE BRAKES PEDAL ASSEMBLY SERVICE

KasparovChess PDF Articles, Sergey Shipov Polanica Zdroj 2000 A Tournament of Surprises

Jung, C G 1932 Article on Picasso

ARTICLE TRANNY AUTO REASSEMBLE PART1

On The Manipulation of Money and Credit

rossijskoe oruzhie vojna i mir

vonnno polevoj obman v chechne nastupil mir konca kotoromu ne

zaterjannyj mir ili maloizvestnye stranicy belorusskoj istorii

więcej podobnych podstron