Handout for lecture 2: Early economic thought ( ca 800 BC – ca 1500)

1. Chronology of economics

a) Some important dates in economics

1776, Adam Smith,

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

1817, David Ricardo

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation

1848, John Stuart Mill

Some Principles of Political Economy and their Application to Social

Philosophy

1871-4, William Stanley Jevons

Theory of Political Economy; Carl Menger, Principles of Economics, Leon Walras

Elements of Pure Economics

1890, Alfred Marshall,

Principles of Economics

1936, John Maynard Keynes,

General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

1948, Paul Samuelson,

Economics

1959, Gerard Debreu,

The Theory of Value

b) Important historical episodes in economics

Mercantilism, 13th - 16th centuries

Physiocracy, France 1750 -1789

Classical economics, first half of 19th century

Marginalism, starting late 19th century

Historical economics, late 19th century

American institutionalism, 1918 to 1940s

Rise of business cycle theory, early 20th century

Keynesian economics, 1940s onwards

Rise of econometrics and mathematical economics, 1940s onwards

Early economic thought (pre-classical economics) (8

th

century BC – 1776)

1. early pre-classical economics (Greeks, Scholasticism) (800 BC – 1500)

2. late pre-clasiccal economics (Mercantilism, 13th - 16th centuries; Physiocracy, France 1750 -1789)

(1500-1776)

Though economic activity has been a characteristic feature of human culture from the beginning, there was little

formal analysis of this activity until capitalism developed in Western Europe during the fifteenth century.

The economic studies of that time were not systematic: economic theory evolved very slowly from individual

intellectual responses to contemporary problems. No grand analytical economic systems appeared.

In thinking about this early economic thought, we have to keep in mind several points:

1) the thinkers of this period addressed limited aspects of the economy and did not expand their analysis into a

comprehensive economic system, they were not searching for grand, big, general theories.

2. The early pre-classical thinkers gave greatest attention to those kinds of non-market mechanisms of allocation

(force, authority, power, tradition). They were also in general not concerned with the problem of efficiency of

resource allocation, but rather considered the consequences of various types of economic activities for justice and

quality of life (not for economic efficiency as it is in modern economics).

Modern economies are market economies, thus modern economic theory focuses on how markets help to deal with

the problems of scarcity and gives almost no attention to the use of force, authority and tradition as mechanisms

for resources distribution in the society.

People at the time were not dependent on markets to acquire goods, but were for the most part self-sufficient.

Thus, early pre-classical economists were not interested in markets because of relative unimportance of markets in

the daily activities of people.

This is one of the most significant differences between early pre-classical and modern orthodox economics. In a

pre-market (and therefore pre-classical) setting, thinkers focused on the use of authority and power as an allocator

of resources.

In addition, we should not forget that these writers believed that it was inappropriate to separate any particular

activity – economic for example, from all other activities. In their writings, they therefore did not abstract

economic activity from all other activities, as it is in contemporary economics.

And, finally, we have to remember that early pre-classical economics (the writings of Greek philosophers and the

scholastics) was dominated by ethical, not purely scientific, considerations, the ethical, not purely scientific,

questions of justice, fairness and the morality of commerce were central to these thinkers.

For example, the pre-classical writers examined exchange and prices with the purpose of evaluating their fairness

and justice. Those kinds of considerations (the ethical ones) are almost completely absent in modern orthodox

economics, but can be find in the modern heterodox economic thought form the 18

th

century to the present (for

example in Marxism, institutionalism, radical economics and other currents).

So much for the introduction and we can turn to the Greek economic thought.

We shall now discuss the economic thought of:

1. Hesiod,

2. Xenophon,

3. Plato, and

4. Aristotle.

Hesiod,

Works and Days, c. 800 BC

Xenophon, lived in 4

th

century BC

Plato,

The Republic, c. 400 BC

Aristotle,

Politics, c. 310 BC

The ideas of Hesiod were orally presented during the eighth century BC. The most important work with economic

implications attributed to Hesiod is

Works and Days, in which he initiates a pursuit of economic questions that

continued for two centuries in ancient Greece. Being a farmer, Hesiod was interested in efficiency. Efficiency in a

household for Hesiod was the result of hard work, honesty and peace.

Economists use the concept of efficiency in a number of contexts – for example, it is measured as a ratio of

outputs to inputs. Maximum efficiency is then taken to be achieving the largest possible output with a given input.

We can also thing about a similar procedure for minimizing inputs (costs) for a given output.

Much of the writings about efficiency during the early pre-classical period concerned the efficiency at the level of

the individual producer and household. Those writers and Hesiod too were not interested in efficiency at the level

of society. This problem, efficiency at the level of society is much more difficult and complex, then the problem of

efficiency at the level of one producer or household. It is not surprising therefore that Hesiod and other Greek

thinkers were pursuing problems related to this more obvious issue of efficiency.

Beside touching on the problem of efficiency, Hesiod realized that the basic economic problem is one of scarce

resources, he also suggested that competition can stimulate production, for it will cause people to emulate each

other (that is to imitate the activities, which are profitable).

However, though those ideas of efficiency, scarcity and competition are clearly present in Hesiod’s

Works and

Days, they are not expressed in anything like abstract terms. It is just poetry, good, but only poetry. There are

economic insights, but nothing is developed very far and it is difficult to know how much significance to attach to

them.

Xenophon, writing some four hundred years after Hesiod, that is in the 4

th

century BC, took the concepts of

efficient management much farther than Hesiod and applied them at the level of the household, the producer, the

military, and the public administrator. This brought him insights into how efficiency can be improved by practicing

a division of labor.

Oikonomikos, the title of Xenophon’s work, is the origin of the words “economist” and “economics”. However, it is

better translated as The Estate Manager or Estate Management. Taken literally it means Household Management,

“oikos” being the Greek word for “household”. Xenophon’s Oikonomikos is in fact a treatise on managing an

agricultural estate. According to him, an efficient estate should be, first of all, efficiently organized. He believed

that good organization could double productivity in agricultural estate.

He also argued that the division of labor should be practiced in the household or estate in order to increase

efficiency. He observed that in a small town, the same worker may have to make chairs, doors and tables, but he

cannot be skilled in all these activities. In large cities, however, demand is so large that men can specialize in each

this task, becoming more efficient.

In Xenophon world markets and trade are still almost absent, managing the agricultural estate is as central to his

view of economic activity as it was for Hesiod’s.

Attention to the division of labor was continued by other Greek writers, including Aristotle, and later by the

scholastics. We will see that at the level of society Adam Smith gave special recognition to the influence of the

division of labor on the wealth of nations.

Next we turn to Plato. Living in the forth and third century BC.

Plato was mainly a great philosopher, but he had also some contributions to economics. In his treatise Republic,

he was trying to provide a blueprint for the ideal state, which would be free of all the vices inherent weaknesses of

democracy as well as tyranny (or monarchy). For Plato, the most important feature of society should be its

stability. Leaders in democracy in his view would not do what was right and just, but rather use their office to gain

support, while tyrants or kings, on the other hand, would use their power to further their own interests, not those

of the state as a whole.

Plato’s solution to this dilemma was to create a class of philosophers-kings, who would rule the state in the

interests of whole society. What is important from economic point of view, for the ruling class not to become

corrupt, they would be forbidden to own property or even to handle gold and silver, they would receive what they

needed to live as a wage from the rest of community. In this harsh vision, even the wives and kids in the ruling

class should be common property.

Nevertheless, returning to the economics, like other Greek thinkers Plato considered specialization in production as

a key element to efficiency.

He saw a very limited role for trade and the markets in his ideal state. Consumer goods may be bought and sold

(outside the ruling class), but property was to be allocated appropriately between citizens. There would be no

profits or payment of interest on money loans.

Therefore, what is important here is the Plato’s view that the ruling class should not possess private property but

should hold communal property, to avoid corruption and conflicts. This is a first quasi-economic argument against

private property in the history of economics.

So much on Plato.

Aristotle, living in the 4

th

century BC was a student of Plato. The influence of Aristotle on subsequent generations

was such that for many, he was simply “the philosopher”. His writings encompassed philosophy, politics, ethics,

natural science, medicine and virtually all others fields of inquiry, and it dominated thinking in these areas for

nearly 2000 years, until let’s say 15

th

, 16

th

century.

His contributions to what are now thought of as economic issues are found mostly in his work entitled Politics. He

was concerned mainly with the issues of justice, the nature of the household and the state and the status of

private property.

In the matter of private property, Aristotle believed that private property served a useful function in society and

that no regulations should be made to limit the amount of property in private hands. He argued that private

property gives incentives to efficient use of the economic resources.

This may be considered as a first quasi-economic, intuitive, not-formal, argument for private property.

Aristotle was also interested in the problem of justice in distribution and exchange. We should remember that in

his times the allocation of goods was not guided by competitive markets, but rather by authorities. In addition, the

prices of goods were highly regulated. The question of how justly distribute goods and what is the fair price were

therefore important.

When dealing with these problems of distribution and exchange Aristotle distinguished between three types of

justice: distributive justice, rectificatory justice and commutative justice (or justice in exchange).

The first concept applies to the distribution of goods. It is said by Aristotle that goods are distributed justly in this

sense if they are supplied to people in proportion to their merit (goodness, virtue, quality of character,

contributions to the prosperity of state). It was a very elastic notion, for merit can be defined in different ways in

different settings.

Second type of justice is rectificatory justice, that is putting right previous injustice by compensating those who

had lost something. It is not interesting from our point of view.

Finally, there comes commutative justice, justice in exchange.

If two people exchange goods, how do we assess whether the transaction is just? We could say that if exchange is

voluntary, than it must be just. Aristotle recognized however, that in such exchanges justice does not determine a

unique price, but merely a range of possible prices in between the lowest price the seller is prepared to accept and

the highest price the buyer is prepared to pay. There is therefore a scope for a rule to determine the just price

within this range.

His answer was the harmonic mean of the two extreme prices, which is given by the formula:

2/[1/p

1

+1/p

2

],

Where, p

1

and p

2

are the relevant prices.

The harmonic mean has the mathematical property that if the just price is, say 40% above the lowest price the

seller will accept, it is also 40% below the highest price the buyer is prepared to pay.

This is Aristotle’s concept of justice in exchange.

We should remember – he was not dealing with exchange in competitive markets, where there is a unique price,

for in his times the role of markets was limited.

Aristotle also developed a distinction between economics – the science of household or estate management, and

the science of wealth getting, which is called

chrematistics (that is wealth-getting, accumulating wealth).

Aristole distinguished between two kinds of chrematistics – natural and unnatural one. The first one, natural

chrematistics is a part of economics (that is household management), for a person should know whether to

engage in planting wheat or bee keeping, or should know where to go fishing or hunting. These were natural ways

in which to acquire, to get wealth (barter exchange was also part of natural chrematistics).

In contrast, the second type of chrematistics is getting wealth through exchange using the money. It is according

to A. unnatural, for this could involve making a gain at someone else’s expense. Unnatural ways to acquire wealth

included commerce by the use of money and usury (lending money at interest). This kind of chrematistics is not

included in economics and should be condemned as unnecessary and evil, morally bad.

What does it mean that for A. commerce and exchange were unnatural and therefore morally bad?

In Aristotle’s vision, people should aim at a good life. To do this they needed material resources, provided by their

estate. These could be obtained by means of natural chrematistics or by trade and exchange (unnatural, bad kind

of chrematistics). However, according to Aristotle a characteristic feature of a good life is that human needs are

limited and high levels of consumption are not part of a good life. Therefore, there is a limit to the natural

acquisition of wealth – that is fulfilling your basic needs.

What disturbed Aristotle about commerce was that it offered the prospect of an unlimited accumulation of wealth,

far beyond the needs of the household. He thought of money exchange rather as an attempt to satisfy unlimited

desires of human beings. While satisfying the desires was not a part of Greek notion of a good life.

So therefore, according to Aristotle, market exchange with the medium of money, suggests that a person want to

make a monetary gain through the exchange and satisfy the unlimited desire for money and wealth. These

activities do not lead to a good life and as such, unnatural chrematistics should be considered as morally bad.

So much on Aristotle’s economic views.

He had enormous impact on economic ideas during the period of scholasticism. It was Aristotle’s views that St.

Thomas Aquinas and other churchmen developed further in the 13

th

and 14

th

century.

One last remark. The ancient world was dominated by self-sufficiency and isolated (non-market) exchange.

However there was no market economy in the modern sense, commercial activity were sufficiently developed to

provide a big challenge to the thinkers.

Overall, the thinkers whose views are known to us were rather suspicious of commerce and exchange. The

two subjects dominated discussions of economic issues right up to the 17

th

century – justice and the morality of

commerce and exchange. Only by 17

th

century, the existence of market economy and commercial mentality had

come to be accepted.

The Middle Ages and the so-called scholastic economic doctrine.

Some general remarks on the scholasticism.

The scholastics were educated monks, who tried to provide religious guidelines to applied to secular (for example

economic) activities. Their aim was not so much to analyze economic activity taking place during their times, as to

prescribe rules of economic conduct compatible with religious dogma. The economic insights they produced,

usually referred to as “scholasticism” or scholastic economics, were concerned primarily with ethical connotations

of economics.

The most important of scholastic writer was St. Tomas Aquinas,

Summa Theologica, c. 1273, lived in 13

th

century.

Few words about the economy during the Mddle Ages.

Although the production of goods for sale in a market increased throughout the period, it did not play a dominant

role in everyday life. The feudal economy of the middle ages consisted mainly of agriculture in a society bound

together not by a market but by tradition, custom and authority. The society was divided into 4 groups: serfs,

landlords, royalty and the church. All land was fundamentally owned by the Roman Catholic Church or the king.

Use of the land owned by the king was given to the lords, who in exchange had certain obligations to the central

authority. The relationship between lord and serf was also dictated by custom, tradition and authority, the serf was

tied to the land by tradition and paid the lord for use of the land with labor, corps and sometimes money. What is

also important, the church as a largest landholder in Western Europe had significant secular influence in society.

The scholastics essentially addressed the same economic issues as ancient Greeks: that is the institution of private

property and the concepts of just price and usury. We may risk a judgment that scholastic literature is an attempt

to reconcile the religious teachings of the church with the slowly increasing economic activity of the time.

Scholastic writings represent a gradual acceptance of certain aspects of economic activity as compatible with

religious doctrine. The significance of Aquinas ideas lies in his fusion of religious teachings with the writings of

Aristotle, which provided scholastic economic doctrine with much of its content.

To reconcile religious doctrine with the institution of private property and with economic activity, Aquinas had to

challenge numerous biblical statements condemning private property, wealth and the pursuit of economic gain.

As you know, we can find in the Bible the following statements:

And Jesus said to His disciples, 'Truly I say to you, it is hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.

Or: 'And again I say to you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter

the kingdom of God.'

Based upon the New Testament early Christian thinkers held also that communal property is the natural state of

the world.

St. Thomas using Aristotle’s thought were able to argue in a convincing way that private property is not contrary to

natural law or religious beliefs. Although he agreed that under natural, god’s law, all property is communal, he

maintained that the private property was an addition, not a contradiction, to natural, god’s given, law. The nature

of this argumentation was religious, not economical, but the implications of Aquinas reasoning were powerful and

extremely beneficial for the economy.

Aquinas was also concerned with another aspect of economic activity, that is the price of goods. Unlike modern

economists, he was not trying to analyze the formation of prices in an economy or to understand the role that

prices play in the process of resource allocation.

He focused on the ethical aspect of prices, raising issues of justice in exchange. Mainly, he was asking - What is a

just price?

Historians of economics differ in their interpretations of the Aquinas notion of just price. Some of them argue that

a just price of a commodity according to Aquinas is an equivalent to the cost of the labor embodied in the

commodity.

Others, that is an equivalent in terms of the utility, and others that the just price is an equivalent in terms of total

cost of production.

The most popular interpretation is, however, that for Aquinas just price meant simply the market price.

If this is correct – we should stress that it is not useful solution, since Aquinas had no economic theory explaining

the forces that determine market price.

Scholastic thinkers, following Aristotle, were also in the early middle ages prohibiting the usury, that is taking the

interest on money loans, but later in the period they accepted it, at least if money was lent on business purposes.

St Thomas Aquinas was a complex and interesting thinker. On the one hand, he held back economic thinking by

emphasizing ethical issues and focusing on moral aspects of economics; on the other hand, he advanced

economics by his use of little more abstract thinking than writers before him.

So much on Aquinas.

Short summary of early pre-classical economics.

Pre-classical thinkers did not pursue economics as a separate discipline; they were interested in much broader,

more philosophical issues. Moreover, since the economic activity they observed during those early times was not

organized into a market system as we know it, they concentrated not on the nature and meaning of the price

system but on ethical questions concerning justice and fairness.

The Greeks studied the administration of resources at the level of the household and producer and pursued the

ideas of efficiency and division of labor. They examined the role of private property, different notions of justice and

the distinction between human needs and wants.

Later, scholastic doctrine did not attempt to analyze the economy, but rather to set religious standards by which to

judge economic conduct. Nevertheless, the scholastic doctrine helped to form a base for the development of a

more analytical, abstract approach to economics.

Handout for lecture 3

Mercantilism and the Physiocracy

Early economic thought (pre-classical economics) (8

th

century BC – 1776)

1. early pre-classical economics (Greeks, Scholasticism) (800 BC – 1500)

2. late pre-classical economics (1500-1776)

•

Mercantilism, 16th - 18th centuries;

•

Physiocracy, France, 1750 -1789

Late pre-classical economics spans from circa the year of 1500 to 1776. We can distinguish two main currents of

economic thought in this period: Mercantilism, active in the whole Europe from 13

th

to 16

th

century and

Physiocracy, a French school of economic thought, active from about 1750 to 1789. We discuss them in turn.

Important writers of this period (late pre-classical economics)

Thomas Mun,

England’s Treasure by Foreign Trade, 1664

William Petty,

Political Arithmetic, 1690

Bernard Madeville,

The Fable of the Bees, 1714

David Hume, Political Discourses, 1752

Richard Cantillon,

Essay on the Nature of Commerce in General, 1755

Francois Quesney,

Tableu Economique, 1758

The period between 1500 and 1750 was characterized by an increase in economic activity. Feudalism was giving

way to increasing trade. Individual economic activity was less controlled by the custom and tradition of the feudal

society and the authority of the church. Production of goods for market became more important and land, labor

and capital began to be bought and sold in markets.

This laid the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution in the second part in the 18

th

century. However, we have to

remember, that still we are talking about pre-industrial world, where agriculture is the most important sector of the

economy.

During this period from 16

th

to the half of 18

th

century, economic thinking developed from simple applications of

ideas about individuals, households and producers to a more complicated view of the economy as a system with

laws and interrelationships of its own.

Mercantilism.

Mercantilism is the name given to the economic literature and practice in Europe of the period between 1500 and

1750. Although mercantilist literature was produced in all the developing economies of Western Europe (and I

should add some Eastern European, for example in Poland, economies too), the most significant contributions

were made by the English and the French.

Whereas the economic literature of scholasticism was written by medieval churchmen, the economic theory of

mercantilism was the work of secular people, mostly merchant businessmen, who were privately engaged in selling

and buying goods. The literature they produced focused on questions of economic policy and was usually related

to a particular interest the merchant and writer (in one person) was trying to promote.

For this reason, there was often considerable skepticism regarding the analytical merits of particular arguments

and the validity of their conclusions. Few authors could claim to be sufficiently detached from their private issues

and offer objective economic analysis. However, throughout the mercantilism, both the quantity (there were over

2000 economic works published in 16

th

and 17

th

century) and quality of economic literature grew. The mercantilist

literature from 1650 to 1750 was of distinctly higher quality, these writers created or touched on nearly all

analytical concept on which Adam Smith based his Wealth of Nations, which was published in 1776.

The age of mercantilism has been characterized as one in which every person was his own economist. Since the

various writers between 1500 and 1750 held very diverse views, it is difficult to generalize about the resulting

literature. Furthermore, each writer tended to concentrate on one topic, and no single writer was able to

synthesize these contributions impressively enough to influence the subsequent development of economic theory.

Secondly, mercantilism can best be understood as an intellectual reaction to the problems of the times. In this

period of the decline of feudalism and the rise of the nation-states, the mercantilists tried to determine the best

policies for promoting the power and wealth of the nation, the policies that would best consolidate and increase

the power and prosperity of the developing economies.

What is especially important here is the mercantilistic assumption that the total wealth of the world was fixed and

constant. These writers applied the assumption to trade between nations, concluding that any increase in the

wealth and economic power of one nation occurred at the expense of other nations (the rest of the world). Thus,

the mercantilists emphasized international trade as a mean of increasing the wealth and power of a nation.

Using some modern game-theoretic language, we may say, that they perceived economic activity and international

trade in particular as a zero-sum game, that is a game, where it is impossible for both players to win (In a two-

person zero-sum game, the payoff to one player is the negative of that going to the other player). So according to

mercantilists, it is impossible to increase a global wealth of the world in effect of international trade. It is a very

sad assumption, and modern economists do not share it.

The goal of economic activity, according to most mercantilists, was production, not consumption, as classical

economists would later have it.

They advocated increasing the nation’s wealth by simultaneously encouraging production, increasing exports and

holding down domestic consumption. Thus, in practice, the wealth of nation rested on the poverty of the many

members of society. One again, they advocated high level of production, high level of export and low domestic

consumption.

In addition, they proposed low wages in order to give the domestic economy competitive advantages in

international trade. Most of the mercantilists held that wages (of the workers) should be set on the subsistence

level, allowing workers to preserve their lives, but not to consume more than it is required to continue their lives.

Higher wages would cause laborers to limit their work supply and national output; national wealth would fall,

according to mercantilists.

Thus, when the goal of economic activity is defined in terms of national output and not in terms of national

consumption, poverty for the masses benefits the nation. This is another sad consequence of mercantilist

economic theory.

Third general point about mercantilism is their insistence on the notion of balance of trade.

Balance of trade figures, also called net exports, are the sum of the money gained by a given economy selling

exports, minus the cost of buying imports.

A positive balance of trade is known as a trade surplus and consists of exporting more (in financial terms) than

one imports. A negative balance of trade is known as a trade deficit and consists of importing more than one

exports.

As we know today, neither positive nor negative balance of trade is necessarily dangerous in modern economies,

although large trade surpluses or trade deficits may sometimes be a sign of other economic problems.

According to mercantilists a country should increase exports and discourage imports by means of tariffs, quotas,

subsidies, taxes and the like in order to achieve a so-called favorable or positive balance of trade.

Production should be stimulated by government interference in the domestic economy and by the regulations of

foreign trade.

Protective duties should be placed on manufactured goods from abroad; and the state should encourage the

import of cheap raw materials to be used in manufacturing goods for export.

Why did the mercantilists argued for a positive balance of trade?

It is not an easy question to answer.

Many early mercantilists defined the wealth of nation not in terms of nation’s production or consumption, but in

terms of its holdings of precious metals such as gold or silver. They argued for positive balance of trade because it

would lead to a flow of precious metals into the domestic economy to settle the trade balance. Remember here

that later or most eminent mercantilists equated the wealth of nation with the overall production of the nation.

While for early mercantilists the wealth of nation consisted of the precious metals accumulated in the domestic

economy.

The first mercantilists argued that a positive balance of trade should be struck with each nation. A number of

subsequent writers however argued that only the overall balance of trade with all nations was significant. Thus,

England might have a trade deficit with India, but because it could import from India cheap raw materials that

could be used to manufacture goods in England for export, it might well have a positive overall trade balance with

all nations.

A related issue concerned the exports of precious metals or bullion (that is gold or silver in bars).

Early mercantilists recommended that the export of bullion be strictly prohibited. Later writers suggested that

exporting bullion might lead to an improvement in overall trade balances if the bullion were used to purchase raw

materials for export goods.

So much on the mercantilist concept of positive trade balance.

One more point about mercantilist theory concerns money.

The early mercantilists equated the wealth of nations with the stock of precious metals internally held in the

country. They were very impressed with the significance of the tremendous flow of precious metals into Europe,

particularly into Spain, from the New World, from America. It is therefore not surprising that they became to

identify the wealth of nations with gold and silver.

However later mercantilists subscribed to a more sophisticated view and identified the wealth of nation with the

nation’s overall production. They were able to develop useful analytical insights into the role of money in an

economy.

A central feature of this late mercantilist literature is the conviction that monetary factors, money supply, rather

then real factors (such as quantity of labor, capital goods and the like), are the chief determinants of economic

activity.

They maintained that an adequate supply of money is particularly essential to the growth of trade, both domestic

and international. Changes in the quantity of money, they believed, generate changes in the level of real output.

Therefore, in this view a positive balance of trade, which would effect in a flow of money into the domestic

economy, would increase the production, the real output and therefore contribute to the increasing wealth of

nation.

Classical economists and Adam Smith radically rejected this view, that monetary factors are main determinants of

economic activity and economic growth in the second halt of 18th century.

Classical economists held that the level of economic activity and the rate of growth depend upon a number of real

factors: the quantity of labor, natural resources, capital goods and the institutional structure of the society. Any

changes in the quantity of money according to classical economists would not influence the level of neither output

nor growth, but only the general level of prices.

Mercantilists held that money supply (not any non-monetary, real factor) was the main factor contributing to the

wealth of nation.

So much on the assumptions of the mercantilistic economic doctrine, and we can move to the discussion of its

contribution to the economic theory – theoretical contributions of mercantilists.

Probably the most significant accomplishment of the later mercantilists was the explicit recognition of the

possibility of analyzing the economy. As we remember, the ancient and medieval thinkers were mostly engaged in

moral, ethical analysis of the economy. It is just in mercantilistic writings, that economy becomes an object of a

purely scientific, not moral analysis. They started to think about an economy as a subject of science, they realized

that the laws of economy could be discovered by the same methods that revealed the laws of physics and other

sciences. This was extremely important step toward subsequent developments in economic theory.

Many mercantilists saw an economy as a mechanical system and believed that if one understood the economic

laws governing the economy, one could control the economy. Wisely proposed legislation could, in this view,

positively influence the course of economic events and economic analysis would indicate what forms of

government intervention would help the economy.

They however realized that government intervention must not be in contradiction with some basic economic truths

such as the law of supply and demand.

Some of them correctly deduced, for example, that price ceilings set below the equilibrium prices lead to excess

demand and shortages.

In addition, the later mercantilists frequently applied the concepts of economic man and the profit motive in

stimulating economic activity – they said, that government cannot change the basic nature of human beings, and

especially their egoistic drives. Therefore, politicians have to take these factors as given (that humans are egoistic

and driven by profit motive) and try to create a set of laws and institutions that will channel these drives to

increase the power and prosperity of the nation.

Many of the later mercantilists became aware of the serious analytical errors of their predecessors (that is early

mercantilists). They recognized, for example, that stock of gold and silver is not a measure of the wealth of a

nation, that it was not possible for all nations to have a positive balance of trade, and also that no one country

could maintain a positive balance of trade over the long run.

What’s more, some of them realized that trade can be mutually beneficial to nations and that advantages will

occur in those countries that practice the division of labor in production.

An increasing number of writers recommended a reduction in the amount of government intervention, anticipating

the prescriptions of Adam Smith and other classical economists.

We have to remember however, that none of these writers was able to present an integrated view of the operation

of a market economy – the manner in which prices are formed and scarce resources are allocated. This was

eventually achieved by Adam Smith and classical economists in the second half of 18

th

century and in 19

th

century.

The popular explanation of this failure of mercantilists to produce a systematic account of a market economy is

that the mercantilists believed that there was a basic conflict between private and public interests or between

private and public welfare.

Therefore, they considered it necessary for government to channel private self-interest into public benefits.

Classical economists, on the other had, found a basic harmony in society between private, egoistic drives of

individuals and social welfare. Even the later mercantilists who advocated market policies lacked sufficient insights

into the operation of market to make an adequate argument linking private self-interest and social welfare.

Still, the writings of the later mercantilists were used by Smith to develop his analysis, and this is another

significant contribution of the mercantilists.

So much on the analytical contributions of mercantilists to the economic theory.

The thought of some influential mercantilist writers.

Thomas Mun (1571-1641), director in one of the most important English trading companies, his most important

book was

England’s Treasure by Foreign Trade, published after his death in 1664.

Mun was a typical mercantilist, he was a proponent of governmental policies that benefited a particular business

interest. It is often said that his book is the classic example of English mercantilist literature.

Mun asserted in the tile of the book that England’s treasure (the wealth of England) was gained by foreign trade.

His thinking was typically mercantilistic in that he confused the wealth of nation with its stock of precious metals

and therefore argued for a positive balance of trade and inflow of gold and silver to England.

He believed that government should regulate foreign trade to achieve a positive balance, encourage importation of

cheap raw materials, encourage exportation of manufactured goods, use protective tariffs on imported

manufactured goods and take other actions to increase population and keep wages low and competitive.

These are all classic mercantilistic policies.

But Mun also has refuted some of the cruder mercantilistic notions, such as a view that England should have a

positive balance of trade with each country; he argued that the really important thing is to have a positive balance

of trade with all countries.

So much on Mun’s book.

Another mercantilist thinker, William Petty (1623-1687), was a sailor, physician, inventor, and what is most

important for us, the first economic writer to advocate the measurement of economic phenomena.

His economic writings were not general treatises; they were the result of his practical interests in matters such as

taxation, politics, money, and measurement.

His most important economic work,

Political Arithmetic, was published after the death of the author in 1690.

Petty was apparently the first to explicitly advocate the use of what we would call statistical techniques to measure

social and economic phenomena. He tried to measure population, national income, exports, imports, and the

capital stock of England. His methods were very crude or simple indeed, but the tried to express economic events

in terms of numbers, weight, and measure, which is a characteristic feature of modern economics. So we could

say, that Petty is a precursor of contemporary methodological position of mainstream economics, which aims at

statistical and econometric testing of theoretical propositions.

Later Adam Smith rejected Petty’s political arithmetic because of the simplicity of Petty’s methods and the

problems of obtaining reasonably accurate data, and the process of quantification of economic analysis has

stopped for nearly 100 years until the second half of 19

th

century.

Another mercantilistic thinker Bernard Mandeville (c. 1670-1733) wrote a satirical poem entitled

Fable of the Bees,

or Private vices, Public Benefits (1714), which drew interest not only from economists but also from philosophers,

psychologists, and other scientists.

In the poem, Mandeville argued against some widely shared at the time views about morality. According to these

views, good society and accordingly good economy requires that people behave virtuously, that is altruistically for

example. In other words, the popular opinion at the time was that people should care not only for their own good,

but also for the good of other members of society, if you want to have a prosperous society with high standard of

social welfare.

Mandeville argued that egoism and selfishness is a moral vice, but that social good, public benefit could result from

selfish acts if these actions were properly channeled by government. On the other hand, if you would try to

change people by moral persuasion, and try to build a society where people are driven by private virtues (not

private vices as in the real societies) you would end up with much lower level of economic output, unemployment

and economic depression. So private vices produce public benefits.

So, according to Mandeville, one should accept men and women as they are and not try to moralize about what

they should be. It is the role of government to take imperfect humankind, full of vice, and by rules and regulations

channel its activities toward the social good.

As a mercantilist, Mandeville had no concept of natural harmony, where the so-called “invisible hand” of the

market, within appropriate institutional setting and without the need of government intervention, makes individual,

egoistic actions also profitable for the whole society. Such a concept was later developed by Adam Smith.

He still insisted that government should regulate much of the economic activity, for example, regulate the foreign

trade in order to create employment and to undertake various projects to provide employment for the poor. In

Mandeville thought mercantilist ideas thus coexisted with his recognition of the importance of the beneficial effects

of the markets.

David Hume (1711-1776).

He is now best known for his philosophical writing, but he also contributed to economics. He was a close friend to

Adam Smith; his economic views are contained in nine essays published in 1852 as a part of a volume of

Political

Discourses.

Like many of his contemporaries Hume could be called a liberal mercantilist, he had one foot in mercantilism, but

with the other stepped forward into classical political economy.

His most important contribution is known in international trade theory as the price specie-flow mechanism,

where

specie is simply the money in the form of coins rather than notes.

Hume pointed out that it would be impossible for an economy to maintain a favorable positive balance of trade

continuously, as many mercantilists advocated.

A positive balance of trade would lead to an increase in the quantity of gold and silver (that is specie) within an

economy (let’s say English economy).

An increase in the quantity of money would lead to a rise in the level of prices in the economy with the positive

balance of trade (English economy).

If England has a positive balance of trade, some other country or countries must be having negative balance, with

a loss of gold or silver and a subsequent fall in the general level of prices in those countries.

Exports in England will decrease and imports will increase because its prices are relatively higher than those of

other economies.

The opposite tendencies will prevail in an economy with an initial negative balance of trade.

This process will ultimately lead to a self-correction of the trade balances in all countries.

Thus, according to this theoretical, beautiful argument of Hume (price specie-flow mechanism), mercantilistic

policy of advocating a positive balance of trade is self-defeating, it is impossible to have a positive or negative

balance of trade in the long run.

It is a very strong, defeating argument against mercantilistic policy.

However, other mercantilists unfortunately paid little attention to Hume’s argument, and they still held the view

that a nation in the first place should care about its balance of trade.

But we still name Hume as a mercantilist because he believed that gradual increase in the money supply would

lead to an increase in real production, real output, while it is characteristic feature of classical economists’ thought

that they maintained changes in money supply would change only the general level of prices.

Therefore, Hume was at least half-mercantilist.

A short summary about mercantilism.

Mercantilists made useful contributions to economic theory, the most important of which was their recognition that

the economy could be formally, scientifically studied. They developed also some abstract models (such as Hume’s

price specie-flow mechanism) to discover the laws that regulated the economy. Along with Physiocrats they can be

regarded as the first economic theorists.

The Mercantilists achieved the first insights into the role of money in determining the general level of prices and

into the effects of foreign trade balances on domestic economic activity.

They also perceived exchange, especially international trade as a process in which one party gains at the expense

of another. Therefore, they advocated intervention in the economy by the government.

Finally, the argument by David Hume, price specie-flow mechanism, put a final nail in the coffin of mercantilist

economic theories, so to speak.

We should however remember that mercantilism could be interpreted not as an attempt to build an economic

theory, but as a sort of rent-seeking activity.

The mercantilists according to this interpretation were driven not by the desire to discover the truth about the

economy, but rather by profit motives to use government to gain economic privileges for themselves. They were

generally merchants who favored government granting of monopolies that would enable the merchant-monopolists

to charge higher prices.

This is only a suggestion, but there may be some truth in this interpretation also.

Physiocracy, France, 1750 -1789

Although mercantilism was a predominant economic school in 18

th

century France, a new but short lived

movement called Physiocracy (or Physiocratic school) began there, in France around 1750.

It provided significant analytical insights into the economy, perceived the interrelatedness of the sectors of the

economy and analyzed the working of non-regulated markets. Thanks to these achievements, the influence of

physiocracy on subsequent economic thought was considerable.

Historians of economics often arbitrarily group thinkers with divergent ideas into a school of thought, usually

because of a single similarity in their thought.

However, the writings of physiocratic school express remarkably consistent views on all major points. There are

three reasons for this, and thus these are three reasons for calling physiocracy – the school of economic thought.

We shall not call mercantilism a school of economic thought, since mercantilistic writings were extremely diverse

and widely scattered in time and space. Mercantilists were united by the insistence of the balance of trade as an

indicator of country opulence, of country prosperity, but in many other aspects of their works their views were

incoherent, inconsistent or simply opposing to one another. So mercantilism was rather a deeply internally diverse

movement in the history of economics, than a school of economic thought

First reason for calling the physiocratic movement school of economic thought is that physiocracy developed

exclusively in France. There were no physiocratic writers in other countries.

Second reason, is that ideas of physiocrats were presented over a relatively short period, from about 1750 to

1780s. Somewhat ironically, we may say that no one was aware of physiocratic ideas before 1750 and after 1780,

only a few economists had heard of them.

Finally, third reason is that physiocracy had an acknowledged, charismatic intellectual leader, Francois Quesnay

(1694-1774), whose ideas were accepted virtually without question by his fellow physiocrats. There was no such

leader in mercantilist movement for example. The writings of other physiocrats were mainly designed to convince

the reader of the merits of Quesnay’s economics.

So physiocracy was a school of economic thought because it was a movement quite limited in space (that is

geographically), time and the diversity of their ideas, it was a closely knit group of followers to spread the

doctrines of the master – F. Quesnay.

The term “physiocracy” means “the rule of nature” or “the regime of nature”, “the authority of nature” and the

like.

In 18

th

century France many feudal institutions still remained, many more than for example in 18

th

century

England, and the king possessed absolute power. Economic policy in the early 18

th

century was mainly

mercantilistic, there were attempts to increase exports and reduce imports, thereby both achieving national self-

sufficiency and accumulating the treasure. In addition, there were attempts to increase the population and to keep

wages low, thus forcing people to work hard. Immigration of skilled workers was encouraged through subsidies.

Trade, internal trade, was carefully regulated and new industries were set up, sometimes with foreign workers.

France in the 18

th

century faced severe financial and economic problems. It was not until much, much later that

deaths from famine, from hunger, from starvation, became outdated.

Throughout the century, the 18

th

century, shortages of food were common.

The government resorted to numerous measures in order to deal with the problem, including price fixing,

prohibiting speculation, and direct regulation and coercion of food producers. The main reason for shortages of

food was the lack of internal movement of food, since there were some surpluses of food in some parts of the

country and at the same time, shortages in others. The markets for food were very limited, in large part because

of the governmental taxes and barriers.

The government also faced chronic financial difficulties, these being due to military expenditures incurred by

French kings, Louis XIV and his successors.

The state was continually on the verge of bankruptcy. The clergy (that is people ordained for religious duties in the

church), and the nobility (the aristocracy), who owned most of the nation’s wealth, were largely exempt from

direct taxation, and among those who were liable the burden of such taxes was very uneven. Collection of taxes

was arbitrary and unjust.

A major reason for this was that the state did not have the administrative apparatus to collect them itself, but

farmed the job out to private companies. These would pay an agreed sum to the state in return for the right to

collect taxes, this process was inefficient and unjust methods of collection of taxes were often used.

Physiocratic ideas were developed mainly by Francois Quesnay in 1750s and 1760s.

By the time Quesnay turned to economics (he was in his 60s), he had gained a considerable reputation as a

doctor, surgeon and physician. His position in the French court was as physician to Madame de Pompadour,

mistress of Louis XV, and it was for his medical services that he received an aristocratic title and considerable

wealth. After a few years, his interest in economics stopped and toward the end of his life he turned to

mathematical investigations.

His medical background is important as it influenced his perspective on economics.

In turning to economics, Quesnay sought to analyze the pathology of society and to propose remedies. He focused

on the circulation of money, a clear analogy with the circulation of blood within the body. It is tempting to suggest

that the term “Physiocracy”, meaning the rule of nature, reflected the attitude of an experienced physician,

medicine doctor, who knew the importance of working with nature in discovering a cure for a disease in the

society and the economy.

Beside focusing on the circulation of money, equally significant, the Physiocratic system rested on a clear analysis

of the structure of French society.

The main components of physiocratic thought:

•

Concept of the “natural order”

•

Concept of “net product”

•

The theoretical model of the economy

•

Policy implications and proposals

The concept of natural law or natural order.

The physiocrats like the later mercantilists developed their economic theories in order to formulate correct

economic policies. Both groups believed that the correct formulation of economic policy required a correct

understanding of the economy. Economic theory was therefore a prerequisite of economic policy.

The physiocrats’ unique idea concerned the role of the so-called natural law in the formulation of policy. They

maintained that natural laws governed the operation of the economy and that, although these laws were

independent of human will, humans could objectively discover them – as they could the laws of natural sciences.

Those natural laws, which are independent of human will, but also objectively manageable to discover, made up

the natural order. The natural order is, according to Quesnay, the one being made up of beneficial and self-

evident, created by God, rules that govern the operation of society and the economy. The example of such a

natural law would be in Quesnay’s views:

- right to acquire property through labor

- the right to pursue one’s own interest

- the right to survival

- Duty to respect other persons and property of others

- the right to voluntary exchange, etc.

Following these laws will ensure the happiness of mankind, Greatest possible abundance of goods, greatest

possible liberty to make use of these goods, and harmony of interest between social classes as physiocrats

thought.

Quesnay made a sharp distinction between the natural order as defined above and the positive order in the nature

and society.

A positive order was human legislation, laws created by people, by governments.

What is important here, physiocrats held that where the positive order (human legislation) deviates from the

perfect, created by God, natural order, the beneficial effect of the natural order will not come into full play.

However, if the government in enlightened by reason, positive laws that are harmful to society will disappear. So

this was the task that physiocrats were trying to perform – to advice the government, the king, to implement the

kind of positive order, the state legislation, which is consistent with eternal, created by God, natural order.

The concept of “net product” and the theoretical model of the economy

Even though physiocratic theory was deficient in logical consistency and detail, the physiocrats did determine the

necessity for building theoretical models by abstracting and isolating key economic variable for study and analysis.

So they were early proponents of abstract model building in economics, their work was analytical, it was not some

kind of story telling, but they tried to work scientifically by building models, very simple models, but nevertheless

scientific models.

Using this procedure (modeling) they achieved significant insights into the interdependence of the various sectors

of the economy on the levels both

The major concern of the physiocrats was with the macroeconomic process of development. They recognized that

France was lagging behind other countries, and especially England in applying new agricultural techniques. Most of

France was maintaining its old agricultural techniques in production, and while some areas of France were

introducing advanced techniques, in overall the country was developing very unevenly.

To cope with this problem, the physiocrats like mercantilists wished to discover the nature and the causes of the

wealth of nations and policies that would best promote economic growth. Physiocracy was an intellectual reaction

to the widespread regulation of the economy that was promoted in 18

th

century by French mercantilism.

The physiocrats focused not on money (as mercantilists did), but rather on the real forces leading to economic

development. In reaction to the mercantilistic notion that wealth was created by the process of exchange

(international exchange), they studied the creation of physical value and concluded that the origin of wealth was in

agriculture or nature.

That is a fundamental conclusion of physiocratic thought – the origin of nation’s wealth is in agriculture.

In the economy of 18

th

century, more goods were produced than were needed to pay the real costs to society of

producing those goods. Therefore, a surplus was generated. The physiocratic search for the origin and size of this

surplus led them to the idea of natural or net product.

The agricultural production process provides a good example of a net product.

After the various factors of production – seed, labor, machinery, and the like – are paid for, the annual harvest

provides an excess, a surplus. The physiocrats regarded this as resulting from the sole productivity of nature.

Labor, according to them, could produce only enough goods to pay the costs of labor, and the same held true for

the other factors of production, with the exception of land.

So all other factor of production, beside land, are not productive, they do not produce any surplus over the costs

of their use. Only land is productive factor of production and only agriculture is a productive sector of the

economy. All other sectors (trade, manufacturing) are therefore not productive; they are sterile. They are (other

factors of production and other sectors of the economy), but they are essential for other purposes in the economy,

they are necessary in the economy, but they do not produce wealth.

Manufacturing covers subsistence and the costs of the inputs used up but does not produce a surplus. Land is

productive in physiocratic meaning of the term, in that that it produces a surplus over the necessary costs of

production, only land and agriculture yield a net product, a surplus.

Once more, production from land created the surplus that the physiocrats called the net product. Manufacturing,

trade and other nonagricultural economic activities were considered non-productive, because they created no net

product.

The belief that only agricultural production was capable of returning to society an output greater than the social

costs of that output (cost of production) may seem very strange today.

We know today that other factors of production (capital, labor and others) are productive in the sense also.

The physiocratic view about the unique productivity of land may be explained by the fact that the physiocrats

focused on physical productivity (that is a measure of physical quantity of output produced) rather than value

productivity (a measure of money equivalent of the products). And physical productivity is best physically visible in

agriculture, where plants grow, animals are raised and the like.

In addition, because large-scale industry had not yet developed in France in the middle of 18

th

century, the

productivity of industry was not apparent in the economy of the physiocrats.

The small employer with only a few employees did not seem to be making any surplus of revenues over the costs

of production, and his standard of living was not significantly higher from that of his employees. Therefore, they

could not see that the industry was productive in the same sense as agriculture was.

Having established that the origin of the net product was in land, the physiocrats concluded that land rent (rent

derived from land) was the measure of the society’s net product, society’s wealth.

The relationship between agriculture and net product was explained by Quesnay in several versions of his main

economic work,

Tableau economique, the first version published in 1758.

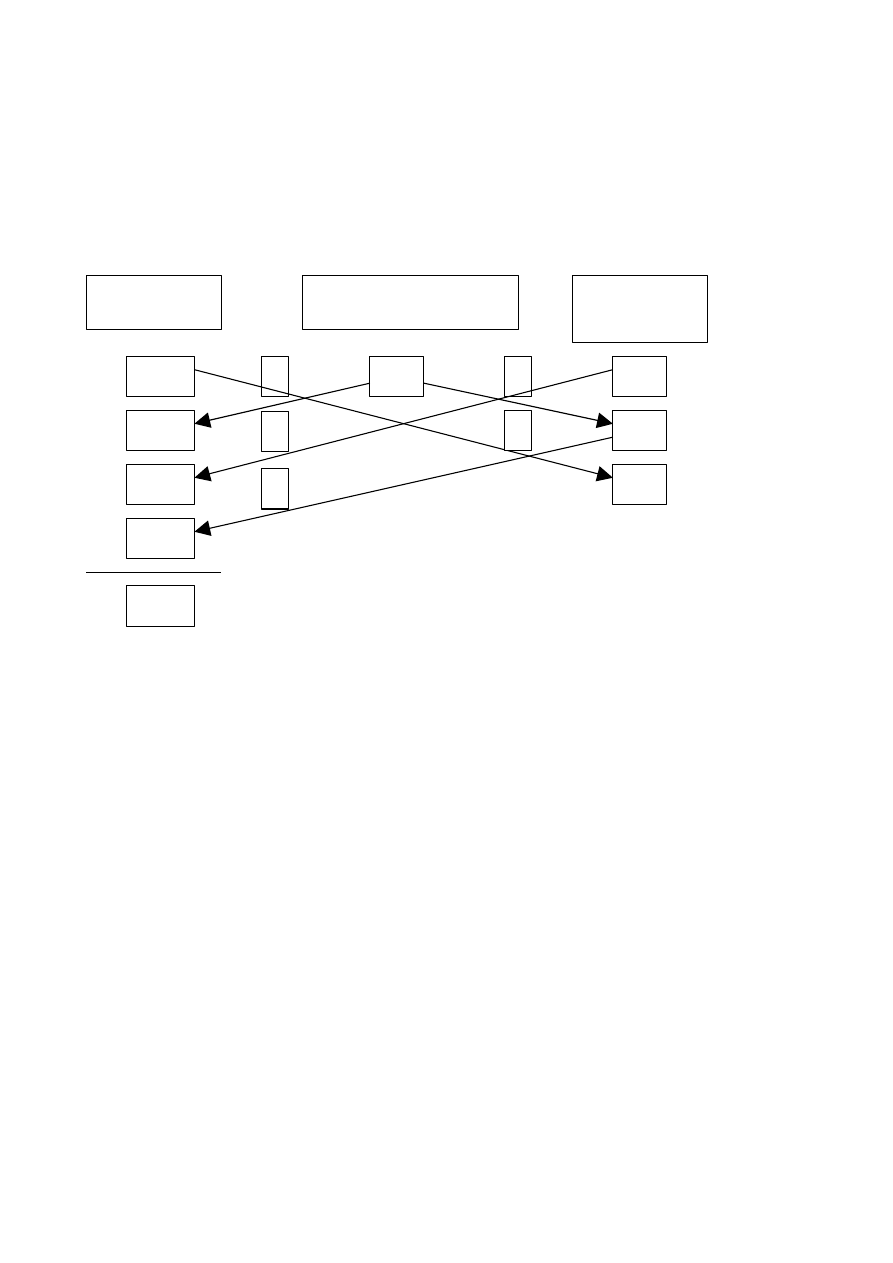

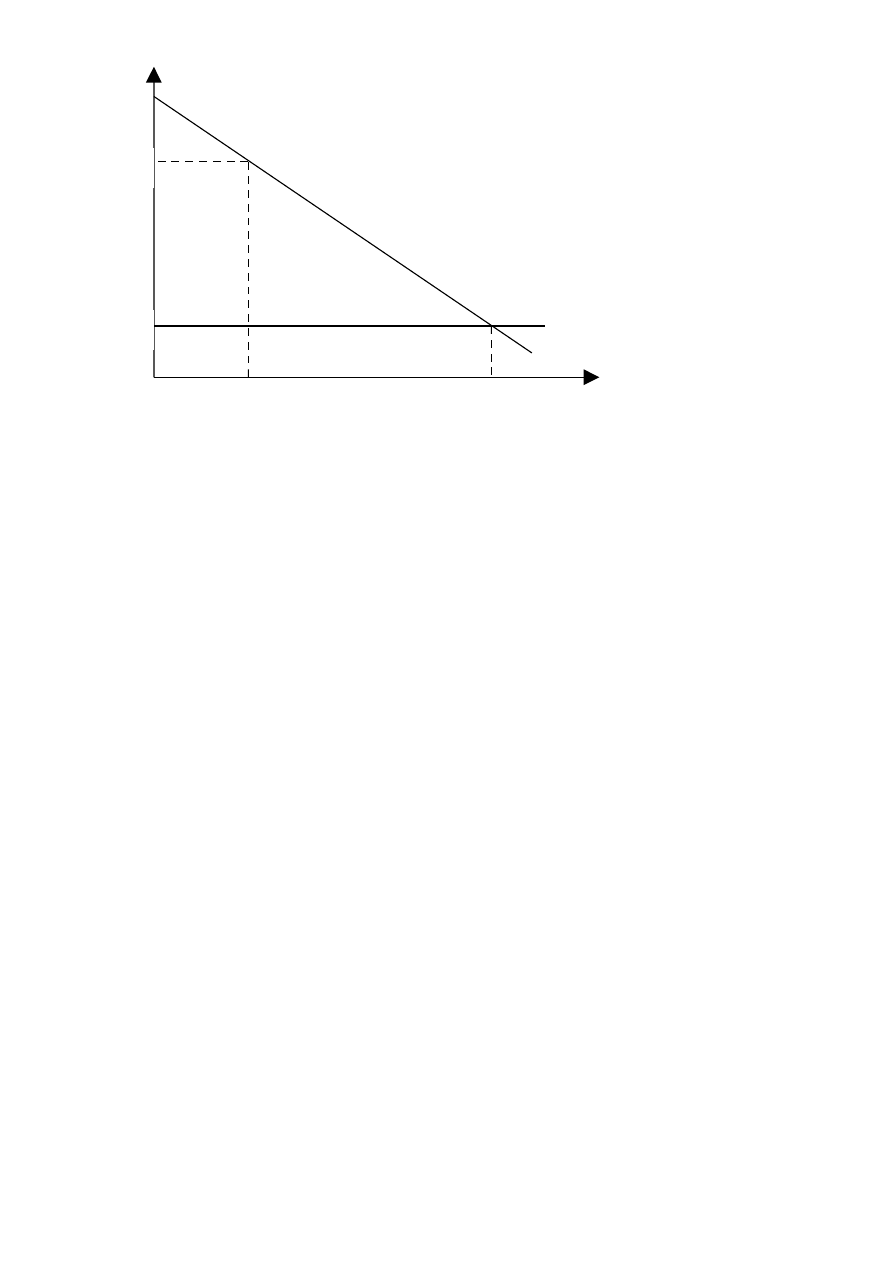

Quesnay presented the creation of net product in the economy by means of quite complicated diagram. The

simplification of the diagram shows the essence of the physiocratic analysis, their model of the economy.

The diagram shows three sectors of society: farmers, landowners (lendołners, king, aristocracy, the church) and

artisans (craftsmen, skilled workers, mechanics, technicians).

There is no foreign sector, government sector or manufacturing sector above the artisan level. So the model is

very abstract and simple.

The physiocratic analysis began with a net product at the beginning of the economic period of let’s say 2 million

pounds held by landowners.

This net product was paid to the landowner class as rent from economic activity in the previous period.

The physiocrats assumed that only land could produce an output greater than its costs of production and every

year accumulated capital generates a gross production worth 5 million pounds. The costs of production in

agriculture are 3 million pounds – 1 million is annual depreciation of fixed capital (agricultural machines) and 2

million is circulating capital (wages for agriculture workers, money for buying manufactured goods to agricultural

production).

The circulating capital is shown as the number 2 in the farmers’ column on the diagram.

So the net product is 2 million pounds at every year – since the annual production is worth 5 million and the costs

of production are 3 million.

The net product it is paid as a rent from farmers to landowners – two millions go to the landowners, this is market

by the number 2 in the central column.

Activities of artisans’ results in products produced and the payments to factors of production in artisan production

equal exactly the value of the goods produced.

These activities are not productive in the Quesnay'’s meaning of the word ‘productive’.

The sterile class, artisans have one million pounds of circulating capital (this is shown as number 1 in the artisans’

column).

Starting at the top center of the Quesnay’s economic table, the landowners spend last year's net product of 2

million pounds by buying agricultural goods (food) from farmers for 1 million pounds and buying luxury goods from

artisans (and paying another 1 million pounds for them)

This is represented by the lines A and B from the landowner column of the diagram, toward the columns

representing the farmers and the artisans.

Thereafter, artisans buy food from the farmers for 1 million. This is represented by line C.

Farmers reconstitute their capital by buying manufactured goods from artisans for 1 million (remember, we said,

that the fixed capital of the productive class is depreciating 1 million each year). This is line D.

Farmers

Landowners

Artisans

(sterile class)

2

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

A

B

C

D

E

5

Finally, artisans spend this 1 million received from farmers buying agricultural products (and paying 1 million) in

order to reconstitute their circulating capital – this is shown by the line E. (remember that at the beginning of the

period artisans had 1 million of circulating capital).

Summing up, the landowners, landlords, have spent all the money received as rent in order to consume food and

luxury goods from the artisans.

The artisans have sold manufactured goods for two million pounds (units of money) and spent two millions in

order to buy food and to reconstitute their capital.

The circulation process in the economy has allowed these two classes in the end to get what they had in the

beginning (landlords spent all the money, and in the next period they will receive another rent form farmers, and

artisans have one unit of circulating capital).

What about the productive class - the farmers? They have sold agricultural goods for 3 million (goods worth one

million for landlords and worth two million for artisans).

In addition, they have still agricultural goods worth 2 million to reconstitute their circulating capital (wages for

workers).

They have also bought the necessary manufactured goods in order to reconstitute their fixed capital (which is

depreciating every year for 1 million).

Finally the money capital is reconstituted as well, since the farmers have 2 million pounds (they got 3 million

pounds lines A, C, E) and spend 1 million (line D).

Every form of capital is thus reproduced in the economy, the process of circulation of goods and money

reproduced the initial conditions of production.

And another year the process repeats itself reproducing the net product and capital.

This is the nature of the tableau economic by Francois Quesnay - a bold, creative conception of the

interrelatedness of macroeconomic sectors with great simplicity.

The table presents how the natural product is generated in the economy, and how goods and money circulate

between different sectors in the economy.

They made few efforts to develop a theory of the microeconomic theories of the markets and these cannot be

considered as successful microeconomic theories.

The physiocrats considered Quesnay's tableau, the diagram, to be their main theoretical achievement. It gave a

crude, simple, but clear representation of two main things.

First, it represents the flow of money incomes between the various sectors of the economy.

Second, it shows the creation and annual circulation of the net product throughout the economy.

The tableau economic, Quesnay's can be considered as first, very simple, macroeconomic model of the economy in

the history of thought. It is a major methodological advance in the development of economics - a grand attempt to

analyze economic reality by means of abstraction.

The tableau, table, was not only an abstract model to analyze the relationships between various sectors in the

economy. The physiocrats also attempted to quantify the sensitivity of the economic system to various changes.

For example by the use of the tableau, Quesnay showed that if a tax of 25 000 pounds were imposed on both

sectors (that is on farmers and artisans), the result would be a decline in the annual product in agriculture from 2

million to 1 million 950 thousand pounds. The net product would decreased by 50 000 pounds in effect of taxes of

25 000 pounds. The result would be then economic decline, for less output would be produced the following year.

Similarly, he showed that a fall in the productivity (due to government intervention) would reduce output. So, the

physiocrats also tried to quantify the effects of different changes in economic system on the national wealth,

national output.

So much on the theoretical contribution of the physiocracy.

A few words on physiocratic economic policy.

The physiocrats thought that free competition led to the best price and that society would benefit if individuals

followed their self-interest. Furthermore, they believed that the only source of a net product was agriculture; they

concluded that the burden of taxes would ultimately rest on land as the sole productive factor.

For example, a tax on labor would be shifted to land because competition had already ensured that the wage of

labor was at a subsistence level, the lowest possible level.

Because the physiocrats believed that a natural order existed that was superior to any possible human design, they

conceived of the economy as largely self-regulating and thus rejected the controls imposed by the mercantilist

system.

The proper role of government was to follow a policy of laissez-faire – which means to leave things alone, allow to

do, in French. A laissez-faire policy demands that a government do not interfere into in the working of the free

market at all.

In the hands of Adam Smith and classical economists this idea of laissez-faire policy, was of tremendous

importance in shaping the ideology of Western civilization. We will talk about this laissez-faire policy many times in

the following lectures.

Returning to some details of physiocratic economic policy, they maintained that the primary obstacles, barriers, to

economic growth proceeded from the mercantilist policies regulating domestic and foreign trade. They objected

particularly to the tax system of the mercantilists and advocated that a single tax should by levied on land. All

other taxes should be abolished.

The most unfortunate of the many governmental regulations according to the Physiocrats, was the prohibition on

the export of French grain, the seeds of wheat or rice, for example.

For physiocrats, it kept low the price of grain in France and in their view was therefore an obstacle to agricultural

development. In the absence of the prohibition, if laissez-faire policy were introduced, the small-scale agriculture

would be replaced by large-scale agriculture and the wealth and power of France would be increased. Laissez faire

policy would lead to increased agricultural production and greater economic growth.

However, we may add, physiocrats did not foresee that soon, at the end of 18

th

century in the effect of industrial

revolution, the agricultural sector would start to lose its central role in the European economies and that the

manufacturing and industry would start to be the most important sectors in the economy.

So to sum up the physiocratic economic policy, I will stress following points

First, they tried to Encourage Agriculture--Improve agricultural management and technique.

2

nd

, they tried to Dismantle restrictive laws and regulations and to introduce the policy of laissez-faire

Third, they wanted to end artificial encouragement of manufacturing by the government.

4

th

, they proposed to reform the tax system and to implement a single tax on the net product derived from

land.

5th, they encouraged the domestic consumption as a mechanism to maintain income flows between the

classes in the society.

And finally, they praised the free international trade, particularly in agricultural goods.

So much on the physiocracy.

The most important contribution of physiocracy was their recognition that the economy can be formally studied, by

means of models, by means of abstract reasoning. Along with mercantilists, they were the first model builders in

economics.

Their most abstract model, the economic table,

tableau economique, shows the interrelatedness of various sectors

of the economy, the process of generating the net product, and circulating of money between different classes of

the society.

We should also stress that they are first advocates of a free market economy, they called not for intervention in

the economy, but for laissez faire, a policy of not intervening in the working of the economy.

Lecture 4

Classical Economics: Adam Smith

What is generally called the classical economics or classical political economy covers more than one hundred years

from about 1776 to circa 1890. Classical economics was almost exclusively produced in Britain.

The three major treatises, economic masterworks of the classical period were:

1. Adam Smith (1723-1790),

Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776 (we shall use the

shorter version of the title, the

Wealth of Nations; almost nobody uses the full title).

2.

On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation by David Ricardo (1772-1823), 1817.

3.

Principles of Political Economy by John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), 1848.

Smith, Ricardo and John Stuart Mill ruled economic thought from 1776 until almost the end of 19

th

century; Smith

from 1776 until about 1820, Ricardo from roughly 1820 to 1850s, and Mill from 1850s until the 1890s.

There were of course many other minor thinkers, who belong to classical economics, but these three authors are

the representative economists of the period.

There are two main characteristic features of the classical economics.

First, classical economists found in the economy a basic harmony; they had a positive attitude to the economic

phenomena, which were induced by natural forces in the economy. They held a view that markets automatically,

at least in the long run, bring a harmony in the economy and the society, that markets harmoniously resolve

conflicts over the scarcity of economic resources, that markets always operate at or near full employment, that

economic depressions are short-lived and that the markets automatically recover from slumps and the like.

This led them to advocate a governmental policy of laissez-faire, policy of governmental non-interfering in the

economy. This was a very optimistic view about the functioning of the markets.

The second widely shared assumption or interest within classical economics is that classical economists were

mainly interested in dynamic issues, long-term, long-run economic processes. The classicals were very interested

in the forces determining the economic growth and the distribution of income over time. Adam Smith focused on

the economic growth, while David Ricardo was interested in long-run changes in the distribution of income that

would take place under capitalism.

After the decline of classical economics in 1870s, the long-term economic problems like the economic growth or

the distribution of national income over time disappeared from economic theory for about 80 years in case of

economic growth (the interest in growth reappeared in 1950s) and about 100 years in case of distribution of

income over time (the interest in this problem has been brought back to economics only in recent let’s say 20

years).

The interest in long-run economic processes is the second characteristic feature of classical economics.

Two other seminal thinkers of the period deserve mention in this introduction to the classical thought.