Contents

lists

available

at

Resuscitation

j o

u

r n

a l

h o m

e p a g e

:

w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / r e s u s c i t a t i o n

Clinical

paper

Impacting

sudden

cardiac

arrest

in

the

home:

A

safety

and

effectiveness

study

of

privately-owned

AEDs

夽

Dawn

B.

Jorgenson

,

Tamara

B.

Yount

,

Roger

D.

White

,

P.Y.

Liu

,

Mickey

S.

Eisenberg

,

Lance

B.

Becker

a

Philips

Healthcare,

Bothell,

WA,

United

States

b

Mayo

Clinic,

Rochester,

MN,

United

States

c

Fred

Hutchinson

Cancer

Research

Center,

Seattle,

WA,

United

States

d

Department

of

Medicine,

University

of

Washington,

Seattle,

WA,

United

States

e

Center

for

Resuscitation

Science,

Department

of

Emergency

Medicine,

University

of

Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia,

PA,

United

States

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Article

history:

Received

23

February

2012

Received

in

revised

form

11

September

2012

Accepted

19

September

2012

Keywords:

Automated

external

defibrillator

Cardiac

arrest

Resuscitation

Defibrillation

Emergency

medical

services

Safety

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Background:

Sudden

cardiac

arrest

(SCA)

remains

a

major

public

health

problem.

The

majority

of

SCA

events

occur

in

the

home;

however,

scant

data

has

been

published

regarding

the

effectiveness

of

privately

owned

AEDs.

Methods:

The

study,

initiated

in

2002

under

prescription

labeling,

continued

with

over

the

counter

avail-

ability

in

2004

and

was

completed

in

2009.

Surveillance

methods

included

annual

surveys,

follow-up

phone

calls,

media

reports,

and

use

queries

upon

order

of

replacement

pads.

AED

owners

reporting

emergency

use

of

the

device

were

contacted

for

an

in-depth

interview,

and

the

ECG

and

event

data

in

the

device’s

internal

memory

were

evaluated.

Results:

25

cases

were

identified

in

which

an

AED

was

used

on

a

patient

in

SCA.

Two

uses

were

on

children.

The

SCA

was

witnessed

in

76%

(19/25)

of

the

cases.

In

56%

(14/25),

the

patient

presented

in

VF

and

at

least

one

shock

was

delivered.

All

14

patients

who

were

shocked

had

termination

of

VF;

6

(43%)

required

more

than

one

shock

due

to

refibrillation.

Shock

efficacy

was

100%

(25/25)

for

termination

of

VF

for

all

delivered

shocks.

Of

the

patients

with

a

witnessed

arrest

who

were

shocked,

67%

(8/12)

survived

to

hospital

discharge.

There

were

no

circumstances

of

unsafe

emergency

use

of

the

AED

or

harm

to

the

patient,

responder,

or

bystanders.

Conclusions:

People

who

purchase

an

AED

for

their

home,

even

without

previous

AED

experience,

are

able

to

use

the

device

successfully

in

both

adults

and

children.

The

high

survival

rate

observed

in

this

study

demonstrates

that

lay

responders

with

privately

owned

AEDs

can

successfully

and

safely

use

the

devices.

© 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

1.

Introduction

Sudden

cardiac

arrest

(SCA)

is

a

leading

cause

of

death

and

a

major

public

health

problem

worldwide.

because

of

its

unpredictable

nature,

patients

cannot

be

identified

a

priori.

Prompt

defibrillation

for

those

patients

in

ventricular

fibril-

lation

(VF)

is

the

definitive

treatment.

Delayed

defibrillation

is

far

less

successful,

with

reduced

survival

for

every

passing

minute

from

the

moment

of

cardiac

arrest.

the

past

30

years,

automated

external

defibrillators

(AEDs)

have

been

broadly

夽 A

Spanish

translated

version

of

the

abstract

of

this

article

appears

as

Appendix

in

the

final

online

version

at

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.09.033

.

∗ Corresponding

author

at:

Philips

Healthcare,

22100

Bothell

Everett

Highway,

Bothell,

WA

98021,

United

States.

Tel.:

+1

425

908

2703;

fax:

+1

425

487

7478.

address:

(D.B.

Jorgenson).

disseminated

to

facilitate

more

timely

defibrillation

and

increase

survival.

AEDs

have

gone

from

exclusive

use

by

highly

trained

responders

(paramedics)

to

successful

use

by

lay

responders

in

airports

and

airplanes,

casinos,

and

other

public

places

where

sig-

nificant

numbers

of

people

gather.

Increasing

public

awareness

of

SCA

and

defibrillation

has

helped

drive

the

placement

of

AEDs

still

further

to

locations

such

as

churches,

schools,

and

libraries.

However,

studies

have

shown

that

approximately

80%

of

SCAs

occur

in

the

home,

and

the

survival

rate

is

lower

in

the

home

than

in

public

places.

early

as

1984,

studies

were

conducted

with

AEDs

in

the

homes

of

SCA

survivors

to

see

if

family

members

could

be

adequately

trained

to

use

the

device

1989,

59

patients

at

high

risk

were

provided

an

AED;

there

were

10

arrests

over

a

57

month

period,

and

the

devices

were

used

in

6

events.

two

patients

were

in

VF,

one

died

at

the

scene

and

one

was

resuscitated

with

residual

neurologic

deficits.

0300-9572/$

–

see

front

matter ©

2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

150

D.B.

Jorgenson

et

al.

/

Resuscitation

84 (2013) 149–

153

Over

the

past

15

years,

AEDs

have

undergone

significant

human

factors

design

development,

such

as

incorporating

voice

prompts

to

guide

users.

User

testing

in

simulated

use

scenarios

has

demon-

strated

the

ability

of

minimally

trained

and

lay

responders

and

even

untrained

people

to

use

the

concerns

regarding

safety

issues

and

FDA

panel

supported

over-the-counter

(OTC)

sales

of

one

AED

model

in

2004.

study

was

initiated

to

capture

infrequent

home

AED

use

data.

2.

Methods

This

was

a

prospectively-designed

observational

post-market

study

voluntarily

initiated

by

the

manufacturer.

Information

was

collected

from

owners

of

the

HeartStart

Home

AED,

model

M5068A,

from

November

2002

to

December

2009.

This

is

a

semi-automatic

device

with

adhesive

pads

and

voice

prompts

to

guide

the

user.

At

study

initiation,

in

2002,

the

devices

were

sold

only

with

a

physician

prescription.

In

November

2004,

OTC

sales

were

allowed

and

the

FDA

mandated

a

surveillance

study.

For

pediatric

patients

(under

8

years

old

or

55

pounds)

a

special

pad

cartridge

inserted

into

the

device

reduces

the

delivered

energy;

this

pediatric

cartridge

remains

available

only

through

a

prescription.

The

study

was

approved

by

Western

Institutional

Review

Board,

and

a

Data

Safety

Monitoring

Committee

routinely

reviewed

data.

All

participation

was

voluntary,

and

persons

interviewed

provided

consent.

Multiple

methods

were

employed

to

identify

AED

uses:

• Product

labeling

and

the

manufacturer’s

website

encouraged

reporting

uses

to

the

manufacturer.

Incentivized

product

regis-

tration

cards,

shipped

with

each

AED,

offered

a

practice

kit

or

accessory

kit.

Owners

who

contacted

the

manufacturer

for

any

reason

were

added

to

the

registered

owners

database.

All

reg-

istered

owners

were

sent

a

yearly

survey

inquiring

if

the

AED

had

been

taken

to

the

scene

of

an

emergency,

even

if

pads

were

never

applied

to

a

patient.

If

a

survey

was

not

returned,

follow-up

telephone

calls

were

used.

• Media

reports

on

the

Internet

were

scanned

for

reported

uses.

• The

only

avenue

for

purchasing

home

replacement

pad

cartridges

was

directly

from

the

manufacturer;

all

who

called

for

replace-

ment

pads

were

queried

regarding

a

use.

Owners

who

indicated

they

had

taken

their

AED

to

the

scene

of

an

emergency

were

asked

to

volunteer

for

a

recorded

interview

con-

ducted

by

a

healthcare

professional.

The

interviewer

asked

specific

questions

on

safety

and

efficacy,

and

the

responder

described

the

use

in

his

or

her

own

words.

The

interview

was

designed

to

cap-

ture

any

difficulty

in

using

the

AED,

and

responder

information

(age,

gender,

training),

patient

information

(age,

gender,

previous

conditions),

and

resuscitation

factors

(location

of

arrest,

bystander

CPR,

shock

delivery,

patient

outcome).

If

an

AED

was

used

in

an

emergency,

a

replacement

device

was

sent

in

exchange

for

the

involved

AED

so

its

internal

memory

could

be

examined.

The

memory

includes

use

time,

number

of

shocks,

patient

impedance,

shock

analysis

decisions,

and

ECG.

Each

case

was

categorized

in

terms

of

a

patient

in

SCA

or

a

patient

who

was

recognized

as

not

being

in

SCA

or

was

determined

later

not

to

have

been

in

SCA

(e.g.,

shortness

of

breath

or

loss

of

consciousness).

The

inclusion

criteria

required

that

the

AED

be

owned

by

an

indi-

vidual

and

intended

for

the

“home.”

If

the

owner

brought

the

AED

along

when

leaving

home

(e.g.,

in

their

car),

that

use

was

included

wherever

it

occurred.

Those

who

declined

to

participate

or

could

not

be

contacted

were

excluded.

Uses

with

insufficient

information,

no

interview,

and

no

exchanged

AED

(for

memory

examination)

where

the

report

could

not

be

verified

were

excluded.

Two

reported

Table

1

Patient

and

responder

demographics.

Adult

patients,

n

=

23

Pediatric

patients,

n

=

2

Responders,

n

=

24

(1

unknown)

Age

Median:

68

years,

range:

26–90

years

4.5

months,

5

years

Median:

63

years,

range:

33–82

years

Gender

20

male,

3

female

1

male,

1

female

14

male,

10

female

Table

2

Location

of

arrest

and

responder’s

relationship

to

patient.

Location

n

Home

18

Family

business

2

Exercise

facility

2

Street/parking

lot

1

Church

1

Club

1

Relationship

n

None

5

Wife

5

Neighbor

4

Husband

2

Daughter

2

Friend

2

Father

2

Mother

1

Son-in-law

1

Brother-in-law

1

uses

were

excluded

from

analysis.

In

one

case,

an

AED

owner

who

had

a

child

at

high

risk

for

SCA

routinely

kept

a

pediatric

car-

tridge

installed

in

the

device.

This

owner

witnessed

an

arrest

at

a

parking

lot

where

an

adult

had

been

involved

in

a

bicycle/auto

accident

with

resulting

severe

blunt

trauma.

She

retrieved

the

AED

from

her

car

but

was

unable

to

remove

the

pediatric

cartridge

to

insert

an

adult

cartridge.

One

50

J

pediatric

energy

shock

was

deliv-

ered;

defibrillation

was

unsuccessful.

In

addition,

reports

of

AED

use

on

family

dogs

were

excluded;

in

these

cases

the

resuscitation

attempts

failed.

3.

Results

There

were

25

cases

where

the

device

was

used

on

a

patient

in

SCA.

These

uses

were

identified

through

direct

calls

to

the

manu-

facturer

(13),

owner

surveys

(10),

and

Internet

reporting

(2).

OTC

purchasers

accounted

for

18

uses

and

prescription-device

pur-

chasers

accounted

for

7

uses,

including

2

pediatric

patients.

In

addition,

there

were

10

uses

where

the

AED

was

placed

on

patients

not

in

cardiac

arrest;

one

of

these

was

a

pediatric

patient.

3.1.

Uses

on

patients

in

SCA

Patient

and

responder

demographics

are

provided

in

The

majority

of

AED

uses,

18

(72%),

occurred

in

the

home

(

with

a

responder

who

was

a

family

member,

14

(56%).

Most

respon-

ders,

17

(68%),

had

no

formal

medical

training;

the

remainder

were

physician/dentist

(3),

registered

nurse

(2),

military

caregivers

(2),

and

CPR/AED

instructor

(1).

the

responders’

level

of

CPR

and

AED

exposure

prior

to

use;

the

most

common,

18

(72%),

involved

watching

the

CD

that

is

shipped

with

the

AED.

Two

respon-

ders

reported

no

formal

AED

training;

one

knew

the

patient

had

an

AED

and

retrieved

it,

and

the

other

had

seen

an

AED

demonstrated

on

television

and

remembered

that

it

was

supposed

to

be

easy

to

use.

Both

patients

treated

by

these

two

responders

survived

and

later

received

an

ICD

implant.

D.B.

Jorgenson

et

al.

/

Resuscitation

84 (2013) 149–

153

151

Table

3

Level

of

CPR

&

AED

exposure

(multiple

answers

permitted).

CPR

and

AED

exposure

n

Watched

product

training

video

18

Read

product

materials

8

Current

CPR

(

≤5

years

ago)

9

CPR

5

and

≤

10

years

ago

3

CPR

10

and

≤

20

years

ago

1

CPR

20

and

≤

30

years

ago

6

CPR

30

years

ago

1

Practiced

use

2

Watched

TV

demonstration

show

2

Watched

demonstration

by

AED

distributor

1

First

aid

class

(year

unknown)

1

a

Some

responders

specified

that

their

CPR

class

did

not

cover

AED

training,

par-

ticularly

those

who

took

the

class

a

long

time

ago.

Table

4

Resuscitation

characteristics.

Characteristic

Percentage

(n)

Witnessed

76%

(19/25)

CPR

performed

88%

(22/25)

CPR

before

AED

applied

to

patient

52%

(11/21,

1

unknown)

AED

CPR

instruction

set

utilized

55%

(12/22)

Patients

presenting

in

VF

56%

(14/25)

Patients

with

refibrillation

43%

(6/14)

Shock

efficacy

100%

(25/25)

a

summary

of

event

characteristics.

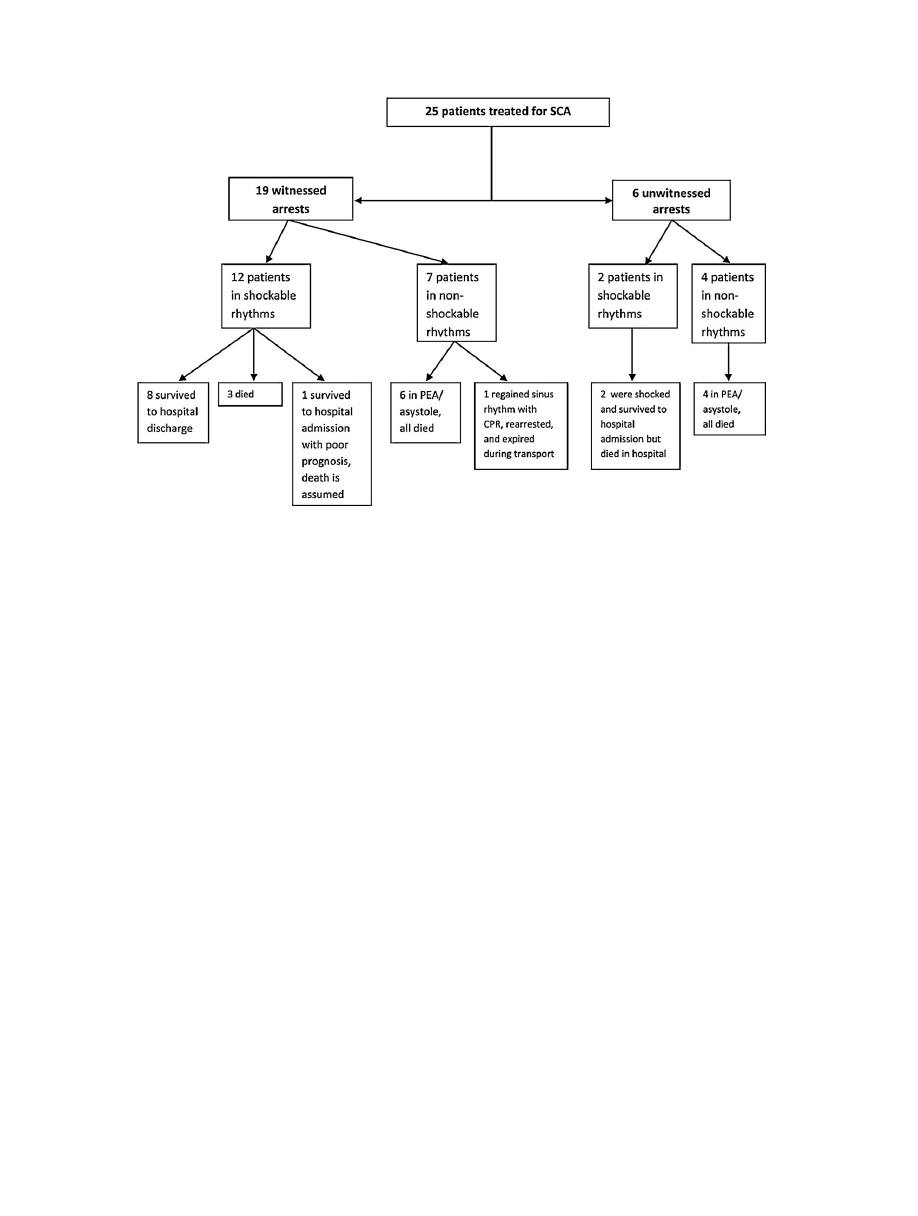

SCA

was

witnessed

in

19

(76%)

of

the

25

cases.

In

22

(88%)

cases,

CPR

was

performed

and

in

12

(55%)

cases

the

user

initiated

the

AED’s

CPR

instruction

set

and

audio

metronome

for

compression

timing.

In

14

(56%)

cases,

the

patient

presented

in

VF

and

at

least

one

shock

was

delivered;

the

median

shock

number

was

1

(range

1–5).

The

median

(range)

time

from

pads

placed

on

the

patient

to

the

first

shock

was

21

(15–53)

s.

All

14

patients

who

were

shocked

had

ter-

mination

of

VF;

6

of

the

14

(43%)

required

more

than

one

shock

due

to

refibrillation.

Shock

efficacy

was

100%

(25/25)

for

termina-

tion

of

VF

for

all

delivered

shocks.

Of

the

14

shocked,

12

(86%)

had

a

witnessed

arrest

and

2

(14%)

had

an

unwitnessed

arrest.

A

summary

flowchart

is

shown

in

patients

with

an

unwitnessed

arrest

who

were

shocked

survived

to

hospital

admis-

sion

but

later

died

in

hospital.

Of

the

12

patients

with

a

witnessed

arrest

who

were

shocked,

8

(67%)

survived

to

hospital

discharge.

Of

the

remaining

4

patients,

3

were

known

to

have

died

(one

had

a

pulse

during

transport

but

the

resuscitation

was

stopped

due

to

a

DNR

order)

and

1

survived

to

hospital

admission

but

had

a

poor

prognosis;

death

is

assumed.

There

were

7

patients

with

a

witnessed

arrest

who

presented

with

a

non-shockable

rhythm.

All

of

these

patients

died;

6

were

in

asystole/PEA

and

1

reportedly

regained

sinus

rhythm

with

CPR

but

rearrested

and

expired

during

transport.

3.2.

Pediatric

SCA

Due

to

the

scarcity

of

pediatric

SCA

events,

a

brief

qualitative

summary

of

two

uses

is

presented.

A

4.5-month-old

baby

girl,

who

had

survived

a

previous

SCA,

was

defibrillated

by

her

parents.

The

patient’s

physician

had

recommended

an

AED

to

the

family.

The

father

reported

the

infant

had

been

awakened

to

have

propra-

nolol

administered;

she

began

crying,

became

limp

and

apneic

and

then

lost

consciousness.

The

father

began

CPR,

called

EMS,

placed

the

AED

with

pediatric

pads

in

an

anterior/posterior

position,

and

delivered

one

shock.

The

infant

was

awake

and

crying

when

EMS

arrived.

The

infant

had

an

ICD

implanted

and

survived

to

hospital

discharge.

In

the

second

pediatric

case,

the

mother

of

a

five-year-old

boy

with

congenital

atrioventricular

canal

defect

and

pulmonary

steno-

sis

had

an

AED

because

their

doctor

ordered

it

after

the

insertion

of

an

artificial

heart

valve.

After

waking

the

child

for

the

first

day

of

kindergarten,

she

saw

him

fall

and

not

get

up.

She

applied

the

AED

and

delivered

one

shock

then

began

CPR

using

the

AED

CPR

instruction

set.

He

refibrillated

and

the

AED

advised

a

second

shock,

which

she

delivered.

He

survived

this

episode

and

received

an

ICD

implant.

3.3.

Uses

of

the

AED

on

patients

not

in

SCA

There

were

9

instances

of

AED

use

on

adults

and

1

use

on

a

child

not

in

arrest.

In

all

cases,

the

AED

did

not

advise

a

shock.

In

each

case

concern

for

the

patient

resulted

in

caregivers’

applying

the

AED

even

though

in

several

instances

the

patient

was

conscious

and/or

breathing

(allowed

under

AED

instructions).

In

all

but

two

cases,

EMS

was

called

and

assumed

care.

Brief

summaries

of

these

cases

are

given

as

follows:

• A

responsive

man

who

had

had

a

previous

myocardial

infarction

was

having

severe

chest

pain,

shortness

of

breath,

and

sweating.

The

patient

felt

better

within

minutes

after

the

AED

was

applied;

EMS

was

not

called.

• A

woman

who

had

previously

had

a

stroke

became

unresponsive.

The

AED

was

applied

but

no

CPR

was

performed.

The

responder

reported

breathing

and

faint

pulses

at

the

neck

and

wrist.

The

patient

reportedly

had

another

stroke.

• A

physician

self-applied

pads

when

he

was

in

atrial

fibrillation

to

see

“what

the

AED

would

do”

and

reported

he

“knew

it

would

not

shock.”

• A

patient

with

an

extensive

cardiac

history

reported

she

was

not

feeling

well

and

was

light-headed.

She

checked

her

pulse

and

self-applied

oxygen

and

the

AED.

She

reported

relief

and

did

not

call

EMS.

• A

responder

applied

his

AED

to

a

man

who

was

conscious

and

sweating.

He

thought

the

man

was

having

a

myocardial

infarction

and

wanted

to

be

ready.

• A

responder

was

called

to

a

neighbor’s

home

because

someone

had

collapsed.

The

responder

applied

the

AED

as

he

was

not

sure

if

the

patient

was

breathing

and

thought

there

was

a

slight

pulse.

• A

wife

noticed

that

her

husband,

who

had

an

extensive

cardiac

history,

could

not

speak.

She

checked

for

signs

of

stroke

and

applied

the

AED,

wanting

to

be

prepared.

• A

woman

reported

that

her

husband

was

unresponsive

on

two

separate

occasions;

each

time,

she

applied

the

AED.

• An

AED

was

placed

on

a

two-year-old

child,

with

a

history

of

long

QT

syndrome,

after

a

four-year-old

sibling

(also

diagnosed

with

long

QT

syndrome)

alerted

their

mother.

The

AED

was

applied

after

a

seizure

started

because

the

mother

“knew

it

would

not

hurt

her.”

CPR

was

started.

EMS

arrived,

and

the

child

recovered.

3.4.

Safety

and

post-use

assessment

The

post-use

interview

included

questions

about

both

patients

and

rescuers,

including

specific

inquiries

regarding

shock

safety

and

inappropriate

shocks.

There

were

no

reported

instances

of

unsafe

emergency

use

of

the

AED

or

harm

during

use

to

the

patient,

responder,

or

bystanders.

Responders

who

treated

patients

in

SCA

reported

they

felt

adequately

trained

in

24

(96%)

of

the

cases;

one

felt

she

should

have

rehearsed

more

in

order

to

be

faster.

Twenty-

four

of

25

(96%)

reported

they

would

use

the

AED

again

if

needed,

while

one

rescuer

was

uncertain.

152

D.B.

Jorgenson

et

al.

/

Resuscitation

84 (2013) 149–

153

Fig.

1.

Event

summary

flowchart.

4.

Discussion

Efforts

to

disseminate

AEDs

to

public

areas

were

initiated

in

1993,

yet

the

overall

survival

rate

for

SCA

in

the

U.S.

remains

at

approximately

2000,

Valenzuela

studied

AED

use

in

casinos

by

security

officers.

of

the

105

patients

(53%)

survived

to

hospital

discharge.

In

2002,

Caffrey

demonstrated

the

successful

use

of

AEDs

at

three

Chicago

airports.

that

study,

18

patients

presented

in

VF

and

11

(61%)

were

resuscitated,

a

survival

rate

for

witnessed

VF/VT

quite

similar

to

that

in

this

report.

The

Public

Access

Defibrillation

Trial

in

2004

studied

randomized

AED

placement

in

community

units

such

as

shopping

malls,

recreation

centers

and

hotels.

were

30

survivors

out

of

128

arrests

(23%)

in

the

AED

arm.

In

another

study

of

public

access

defibrilla-

tion,

an

AED

was

applied

in

4.4%

of

VF

arrests,

with

spontaneous

pulses

present

in

84%

by

the

end

of

EMS

care,

resulting

in

a

52.5%

survival

2008,

the

Home

Automated

External

Defibrilla-

tor

Trial

(HAT)

enrolled

7001

patients

at

increased

risk

for

sudden

cardiac

arrest.

They

compared

survival

with

an

AED

in

the

home

to

a

control

group

without

AEDs

who

were

instructed

to

call

EMS

and

perform

CPR.

the

two-year

enrollment

period

and

two-

year

follow-up

period,

AEDs

were

used

on

32

patients,

14

received

an

appropriate

shock,

and

4

survived

to

discharge.

Mortality

did

not

differ

significantly

between

the

groups.

It

is

noteworthy

that

for

the

HAT

study,

AEDs

were

provided

to

specific

high-risk

indi-

viduals

with

training

and

follow-up

whereas

this

study

followed

people

who

purchased

an

AED

due

to

personal

choice.

While

80%

of

SCAs

occur

in

the

home,

on

private

AED

use

is

limited.

In

this

study

there

were

very

few

uses

reported

from

owners

who

purchased

their

AEDs

with

a

prescription,

and

we

found

no

obvious

differences

in

these

uses

or

training

versus

those

who

purchased

OTC.

Many

owners

could

not

recall

the

condition

under

which

they

purchased

their

AED.

In

this

study,

the

ability

of

home

users,

some

with

no

training

or

experience,

to

use

an

AED

has

been

demonstrated.

We

have

reported

that,

of

home

AEDs

uses,

8

of

12

(67%)

patients

with

witnessed

VF

arrest

and

subsequent

shock

survived

to

hospital

discharge.

In

one

use

a

responder

(a

prescription

purchaser)

was

unable

to

remove

a

pediatric

cartridge,

resulting

in

the

delivery

of

a

pediatric

energy

dose

to

an

adult.

Of

note,

this

same

owner

responded

to

another

adult

SCA

about

one

year

later

with

a

success-

ful

outcome.

In

all

other

uses

the

responders

were

able

to

use

the

AEDs

as

intended,

and

there

were

no

safety

issues

or

harm

reported

to

bystanders

or

responders

or

effectiveness

issues.

There

are

several

limitations

to

this

study

of

privately

owned

AEDs.

The

number

of

patients

with

SCA

treated

with

AEDs

was

small.

Although

we

queried

owners,

it

is

likely

there

were

uses

not

reported

to

us

thus

the

ability

to

discover

complications

or

adverse

events

from

AED

use

was

limited.

Efforts

were

made

to

encourage

owners

to

register

their

devices;

however,

the

portable

nature

of

the

AEDs

along

with

the

inherent

difficulties

of

following

owners

(who

marry,

change

names,

die,

give

away

their

AEDs,

etc.)

and

the

reluctance

of

private

AED

owners

to

participate

in

this

type

of

sur-

vey

made

this

process

difficult.

It

may

be

that

responders

were

more

likely

to

report

a

use

or

be

interviewed

if

the

use

was

successful.

Although

we

interviewed

responders

and

reviewed

the

electron-

ically

recorded

memory

of

the

AEDs,

we

did

not

have

access

to

medical

records

for

verification.

5.

Conclusions

Although

the

number

of

uses

was

small,

this

study

demonstrates

the

safety

and

effectiveness

of

home

AEDs

used

by

lay

persons

with

no

or

minimal

training.

Both

adult

and

pediatric

patients

were

defibrillated

and

survived.

There

were

no

reports

of

injury

to

responders,

bystanders,

or

patients.

In

many

cases

CPR

was

per-

formed

with

the

guidance

of

the

AED’s

CPR

instruction

set.

In

this

study,

the

survival

rate

in

patients

with

witnessed

arrest

and

a

shockable

rhythm

treated

with

home

AEDs

was

similar

to

rates

reported

for

airports

and

casinos.

The

data

suggests

AED

technol-

ogy

designed

for

home

use

appears

to

be

safe

and

effective,

and

may

be

an

important

additional

strategy

for

treatment

of

SCA.

D.B.

Jorgenson

et

al.

/

Resuscitation

84 (2013) 149–

153

153

Conflict

of

interest

statement

Dawn

Jorgenson

and

Tamara

Yount

are

employees

of

Philips

Healthcare

which

manufacturers

the

AED

used

in

this

study.

The

other

authors

have

no

conflict

to

declare.

Acknowledgements

We

thank

the

AED

owners

and

responders

who

shared

their

personal

stories

with

us.

We

would

also

like

to

thank

Michael

Sayre

for

his

work

on

the

Data

Safety

and

Monitoring

Board

and

Robin

Havrda,

Karen

Uhrbrock,

Richard

O’Hara,

Garth

Bammer,

Francesca

Infantine

and

Emily

Mydynski

for

their

invaluable

assistance

with

this

study.

This

work

was

supported

by

Philips

Healthcare,

Bothell,

WA.

References

1.

Zheng

ZJ,

Croft

JB,

Giles

WH,

Mensah

GA.

Sudden

cardiac

death

in

the

United

States,

1989

to

1998.

Circulation

2001;104:2158–63.

2.

Goldberger

JJ,

Cain

ME,

Hohnloser

SH,

et

al.

American

Heart

Associ-

ation/American

College

of

Cardiology

Foundation/Heart

Rhythm

Society

scientific

statement

on

noninvasive

risk

stratification

techniques

for

identify-

ing

patients

at

risk

for

sudden

cardiac

death:

a

scientific

statement

from

the

American

Heart

Association

Council

on

Clinical

Cardiology

Committee

on

Elec-

trocardiography

and

Arrhythmias

and

Council

on

Epidemiology

and

Prevention.

Circulation

2008;118:1497–518.

3.

Larsen

MP,

Eisenberg

MS,

Cummins

RO,

Hallstrom

AP.

Predicting

survival

from

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest:

a

graphic

model.

Ann

Emerg

Med

1993;22:1652–8.

4.

Marenco

JP,

Wang

PJ,

Link

MS,

Homoud

MK,

Estes

3rd

NA.

Improving

survival

from

sudden

cardiac

arrest:

the

role

of

the

automated

external

defibrillator.

JAMA

2001;285:1193–200.

5. Swor

RA,

Jackson

RE,

Compton

S,

et

al.

Cardiac

arrest

in

private

locations:

differ-

ent

strategies

are

needed

to

improve

outcome.

Resuscitation

2003;58:171–6.

6.

Weisfeldt

ML,

Everson-Stewart

S,

Sitlani

C,

et

al.

Ventricular

tachyarrhythmias

after

cardiac

arrest

in

public

versus

at

home.

N

Engl

J

Med

2011;364:313–21.

7.

Cummins

RO,

Eisenberg

MS,

Bergner

L,

Hallstrom

A,

Hearne

T,

Murray

JA.

Automatic

external

defibrillation:

evaluations

of

its

role

in

the

home

and

in

emergency

medical

services.

Ann

Emerg

Med

1984;13:798–801.

8.

Eisenberg

MS,

Moore

J,

Cummins

RO,

et

al.

Use

of

the

automatic

external

defi-

brillator

in

homes

of

survivors

of

out-of-hospital

ventricular

fibrillation.

Am

J

Cardiol

1989;63:443–6.

9.

Callejas

S,

Barry

A,

Demertsidis

E,

Jorgenson

D,

Becker

LB.

Human

factors

impact

successful

lay

person

automated

external

defibrillator

use

during

simulated

cardiac

arrests.

Crit

Care

Med

2004;32:S406–13.

10. Mosesso

VN,

Shapiro

AH,

Stein

K,

Burkett

K,

Wang

H.

Effects

of

AED

device

fea-

tures

on

performance

by

untrained

lay

persons.

Resuscitation

2009;80:1285–9.

11. Brown

J,

Kellermann

AL.

The

shocking

truth

about

automated

external

defibril-

lators.

JAMA

2000;284:1438–41.

12. Eisenberg

M.

On

approving

the

over-the-counter

sale

of

automated

external

defibrillators.

Ann

Emerg

Med

2005;45:25–6.

13. Bar-Cohen

Y,

Walsh

EP,

Love

BA,

Cecchin

F.

First

appropriate

use

of

automated

external

defibrillator

in

an

infant.

Resuscitation

2005;67:135–7.

14. Kerber

RE,

Becker

LB,

Bourland

JD,

et

al.

Automatic

external

defibrillators

for

public

access

defibrillation:

recommendations

for

specifying

and

reporting

arrhythmia

analysis

algorithm

performance,

incorporating

new

waveforms,

and

enhancing

safety.

A

statement

for

health

professionals

from

the

American

Heart

Association

Task

Force

on

Automatic

External

Defibrillation,

Subcommittee

on

AED

Safety

and

Efficacy.

Circulation

1997;95:1677–82.

15.

Sasson

C,

Rogers

MAM,

Dahl

J,

Kellermann

AL.

Predictors

of

survival

from

out-of-

hospital

cardiac

arrest

a

systematic

review

and

meta-analysis.

Circ:

Cardiovasc

Qual

Outcomes

2010;3:63–81.

16.

Valenzuela

TD,

Roe

DJ,

Nichol

G,

Clark

LL,

Spaite

DW,

Hardman

RG.

Outcomes

of

rapid

defibrillation

by

security

officers

after

cardiac

arrest

in

casinos.

N

Engl

J

Med

2000;343:1206–9.

17. Caffrey

SL,

Willoughby

PJ,

Pepe

PE,

Becker

LB.

Public

use

of

automated

external

defibrillators.

N

Engl

J

Med

2002;347:1242–7.

18.

Hallstrom

AP,

Ornato

JP,

Weisfeldt

M,

et

al.

Public-access

defibrillation

survival

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

N

Engl

J

Med

2004;351:637–46.

19. Rea

TD,

Olsufka

M,

Bemis

B,

et

al.

A

population-based

investigation

of

pub-

lic

access

defibrillation:

role

of

emergency

medical

services

care.

Resuscitation

2010;81:163–7.

20.

Bardy

GH,

Lee

KL,

Mark

DB,

et

al.

Home

use

of

automated

external

defibrillators

for

sudden

cardiac

arrest.

N

Engl

J

Med

2008;358:1793–804.

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

(Gardening) Beneficial Insects In The Home Garden

In the Home Bathroom2

Dangers in the Home

Occult Experiments in the Home Personal Explorations of Magick and the Paranormal by Duncan Barford

57 Pattern Relationships in the Home

[Psilocybin]Experiment in the Home Cultivation of Psychedelic Mushrooms A journal of a growing proj

In The Home Living Room

Spanish Influence in the New World and the Institutions it I

93 Team Attacking in the Attacking 1 3 – Crossing and Finis

The main press station is installed in the start shaft and?justed as to direction

The Mammoth in the Myths, Ethnography, and Archeology of Northern Eurasia

Far Infrared Energy Distributions of Active Galaxies in the Local Universe and Beyond From ISO to H

At Work & In The Office Jobs and Occupations

Tourism Human resource development, employment and globalization in the hotel, catering and tourism

Test English tenses in the reported speech and passive voice

Edgar Allan Poe The Murders In the Rue Morgue and Other Stories

więcej podobnych podstron