8

ANTHROPOLOGY & ARCHEOLOGY OF EURASIA

8

Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia, vol. 43, no. 4 (Spring 2005), pp. 8–18.

© 2005 M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN 1061–1959/2005 $9.50 + 0.00.

I

U

.B. S

ERIKOV

AND

A.I

U

. S

ERIKOVA

The Mammoth in the Myths,

Ethnography, and Archeology

of Northern Eurasia

Mammoth bones in Siberia have been known to the indigenous

and later to the Russian inhabitants since long ago. The sheer size

of mammoth bones and tusks made people marvel and led to fan-

tastic notions about giant birds and outsized mammals. During

medieval times these horned animals were called “unicorns” and

“other-horned” [inrog] and Slavs referred to them as indrik or inrog

(Ivanov 1949, p. 133).

Within more recent recorded history numerous explanations of

the origin of the mammoth bones have been offered. For example,

they were connected with Alexander the Great’s elephants, or with

elephants brought by the Flood to Siberia from the south

(Tatishchev 1979, pp. 36–38). In the mid-nineteenth century, some

“simple folk-Siberiaks” believed that mammoths still existed there.

They were convinced that mammoths roamed freely underground,

but that if they came to a riverbank or the shore of a lake and stuck

their heads above the earth’s surface, they would die like beached

fish on seeing daylight (Tobolsk guberniia gazette 1859, p. 305).

English translation © 2005 M.E. Sharpe, Inc., from the Russian text © 2004

Russian Academy of Sciences, Editorial Board of “Rossiiskaia arkheologiia,”

and the authors. “Mamont v mifakh, etnografii i arkheologii severnoi Evrazii,”

Rossiiskaia arkheologiia, 2004, no. 2, pp. 168–72.

The authors teach at Nizhnetagil State Pedagogical Institute.

Translated by Laura Esther Wolfson.

SPRING 2005

9

The first scholarly work on the mammoth was published by

V.N. Tatishchev in the form of a letter to his professor Erik Ventsel

in Sweden in 1725. This same article was twice published in Swe-

den and once in England (Valk 1979, pp. 5, 6). Information on

mammoth bones was published in Russian by I.G. Gmelin in 1730

and 1732, in a work based on a manuscript of the article on mam-

moths sent to him by Tatishchev (Valk 1979, pp. 6, 7). For a num-

ber of reasons, Tatishchev’s article “The Tale of the Beast Known

as the Mammoth” did not appear until 1979 (Tatishchev 1979,

pp. 36–50). It must be noted that the first intact skeleton of a mam-

moth was not acquired by the Russian [Rossiiskoe] scientific com-

munity until 1808 (Vereshchagin and Tikhonov 1990, p. 7).

In the mythological constructs of Siberian peoples, the mam-

moth had a special position, having been present in the creation of

the world. According to the Evenki, the mammoth dug up earth

with its tusks from the sea floor and tossed it in clumps to form the

beginnings of the earth. Thus the earth, originally very small, grew

large and capable of sustaining human life. To smooth the uneven

surface of the earth, the mammoth called on a mythical snake, the

diabdar’a. Where the snake slithered, rivers appeared; where the

mammoth trod, lakes formed; and where the pieces of earth thrown

from the bottom of the sea remained, mountains arose. In other

myths the mammoth and the diabdar’a battled a mythological

monster. This fight led to the topography of the earth as we know

it today (Anisimov 1951, pp. 195, 196). The Selkups believed that

an immense and mighty animal lived under the ground, which

they called the koshar (mammoth). It guarded the entry to the

underworld, which was inhabited by dead people. The image of

the underground mammoth often intermingled with that of the

bear, who was the main spirit of the underworld (Prokof’eva 1949,

p. 159). The Nenets and the Mansi called the mammoth the

“ground bull.” They feared this creature and considered it sacred.

Where it strode, rivers and lakes sprang up and where it bur-

rowed in the earth, tunnels and mountains appeared. The Yakuts

[Sakha] called the mammoth a spirit, the master of the water. The

Mansi, the Khanty, and the Selkup developed the notion of the

mammoth-pike, who lived in “demonic lakes” and were malicious

10

ANTHROPOLOGY & ARCHEOLOGY OF EURASIA

animals. Usually they were portrayed with deer antlers. The Ob-

Ugrians [Khanty and Mansi] also imagined the mammoth as a

huge bird (Ivanov 1949, pp. 135–40). It is interesting to note that

in Siberian mythology the mammoth was associated with all three

worlds: upper, middle, and lower.

a

Myths about the mammoth go back to very ancient times. Study

of archeological material suggests connections between these

myths and current ethnographic information. Usually, the use of

mammoth bones and tusks for life-sustaining activities and the

image of the mammoth in art are considered to date to Paleolithic

times. But interesting archeological data indicate that the mam-

moth image was used, and items were fashioned from mammoth

bones and tusks, during the Holocene period. In addition to mam-

moth bones the bones of other animals from the Pleistocene pe-

riod were sometimes used.

In the Mesolithic stratum of the peat bog at the Koksharov-

Yurinsk encampment [stoianka] a tooth fragment from a woolly

rhinoceros has been found. At the No. 3 Embankment encamp-

ment of the Gorbunov peat bog a Neolithic-era arrowhead was

found, made of scraped and carved from mineralized or fossilized

mammoth bones (Serikov 2001a, p. 57). In a sunken structure in a

Turbin settlement at Borovoy Lake II a mammoth tooth was found

(Bader 1954, p. 252).

One curious discovery of mammoth bones and items fashioned

from them was made at a place of worship, in sanctuaries and

burial mounds. In Kumyshansk Cave on the Chusovaia River in a

group burial mound from the late Neolithic Period, a bison knee

joint was discovered. It was lying in a separate pit filled with ocher,

along with a stone fishing sinker. In the burial mound itself was a

fragment of a rhinoceros shoulder blade (Serikov 2001a, p. 58). At

the sacrificial site under Pisany Kamen on the Vishera River, a dag-

ger 15.4 centimeters [approximately 6 inches] in length was found,

fashioned from a mammoth bone. O.N. Bader has tentatively dated

it to the Eneolithic Era (Bader 1954, p. 252). In the cave sanctuary

at the stone Dyrovatye Rebra (Punctured Ribs) on the Chusova

River in the early Iron Age stratum, a baby mammoth tooth was

found along with a bison vertebrae (Serikov 2001b, p. 57). In the

SPRING 2005

11

medieval stratum at Kaninsk Cave, 155 fragments of mammoth

bone were found, including a shard of tusk showing traces of hav-

ing been worked (Gemuev and Sagalaev 1986, p. 118; Vereshchagin

1981, p. 93).

Such finds are known to have been made not only in the Urals

but farther into Siberia. In burial mound No. 21 of the Neolithic

grave Bratskii Kamen’ (Fraternal Stone) (near Lake Baikal), a

bison bone was found near a human tibia bone (Okladnikov 1976,

p. 145) and in the Eneolithic burial site No. 5 at Ust-Udin, the

tooth of a woolly rhinoceros was found (Okladnikov 1975,

pp. 157, 158). In the Neolithic burial mound No. 10 of the

Ponomarev grave, fragments of an item made from mammoth tusk

was found. The item in question was 60 cm long and was reminis-

cent of an insertable spear tip (Okladnikov 1974, p. 85).

Many sculptures made of mammoth tusks have been found in

Siberian Eneolithic burial sites, anthropomorphic depictions of

couples or individuals. The images of couples were found in the

Ust-Udinsk grave (burial sites Nos. 4 and 6) and in Semenovo

(burial site No. 4). One figure each has been discovered in Novaia

Kachuga and in the burial site at Bratskii Kamen’ (Okladnikov

1955, pp. 286–98). All of these sites are thought to be shamanic

burial sites (ibid., pp. 348–52; Serikov 1999, pp. 52–55). All the

figures of couples—from 12.8 to 25. 6 centimeters in length [ap-

proximately 7 to 10 inches]—were found on the chests of the de-

ceased, adornments for shamanic cloaks. The individual figures

adorned shamanic cloaks and headdresses (Serikov 2000, p. 212).

Such anthropomorphic depictions have been interpreted by A.P.

Okladnikov as spirits of the shaman’s ancestors (Okladnikov 1955,

pp. 304–6). Interestingly, several Siberian peoples (the Khanty and

the Selkup) considered the mammoth to be the guardian of their

ancestors. Thus it was apparently no coincidence that the depic-

tions of ancestors were carved from mammoth tusks. One can see

a certain semantic connection.

The mammoth remained an object of veneration into later eras

as well. One unique discovery was an image of an anthropomor-

phic face, possibly a mask, in a burial site from the Bronze Age in

the Shumilikh grave. The mask was made of the lower part of a

12

ANTHROPOLOGY & ARCHEOLOGY OF EURASIA

neck vertebrae of a woolly rhinoceros (Gorgiunova 2002, p. 9, fig.

6, 1). Curiously, the mask was in a burial site where the body was

in a crouched seated position. A nonstandard position of a body in

a burial site is one of the most important signs of a dead person’s

high social status (Serikov 2002, pp. 135–38). Very often such sites

were interpreted as having been made for shamans (Okladnikov

1955, p. 316; Serikov 1998, p. 32). An unusually large pelvic bone

from a woolly rhinoceros was found in burial site no. 1, where a

number of people were buried in the Khoorlug-Oimak grave (in

southern Tuva), at the grave pit bottom under a plank floor. The

burial site dates to the early Iron Age (Khudiakov 2000, p. 43).

The discovery of a female statuette made from a mammoth tusk in

a seventeenth-century sanctuary in Khaliato I (on the Yamal Penin-

sula) is well known. The statuette stood at the center of a hill sur-

rounded by arrowheads bent and pointing into the ground, with

scattered reindeer bones and antlers (Kosintsev 1993, p. 141). Many

more such examples can be noted, although such rare finds are

infrequently studied or described in publication.

The discovery of bones of extinct animals and items made from

mammoth bones and tusks at Holocene-era monuments is no co-

incidence. Even O.N. Bader, in describing the discovery of the

dagger at Pisany Kamen and the mammoth tooth at Borovoi Lake

II, proposed that the fossilized mammoth bones might have played

a role in religious rituals (Bader 1954, p. 252).

b

This viewpoint

was shared by Iu.S. Khudiakov, who described the discovery of a

pelvic bone from a woolly rhinoceros in the Khoorlug-Oimak grave.

Its placement on the floor of the grave pit in a corner containing

food for the hereafter indicated, in his view, that it was a sacrifi-

cial offering. Such a bone might have appealed to people because

it was found in the earth, pointing to its relationship with the lower,

underground world. It had value for funeral rites because it had

already been “to the other world” (Khudiakov 2000, p. 43).

The placement of such finds at holy sites suggests a “cult” [kul’t]

of the mammoth in ancient times. This is quite probable, as in the

mythological imaginings of Siberian peoples the mammoth occu-

pied a very important role (see above). It must be emphasized that

the myth of the mammoth is related exclusively to a shamanic

SPRING 2005

13

cosmogony and that depictions of mammoths are encountered only

among shamanistic objects (Vasilevich 1949, p. 155). Ethnogra-

phers have described the widespread use among Siberian peoples

of mammoth images on pendants attached to shamans’ costumes

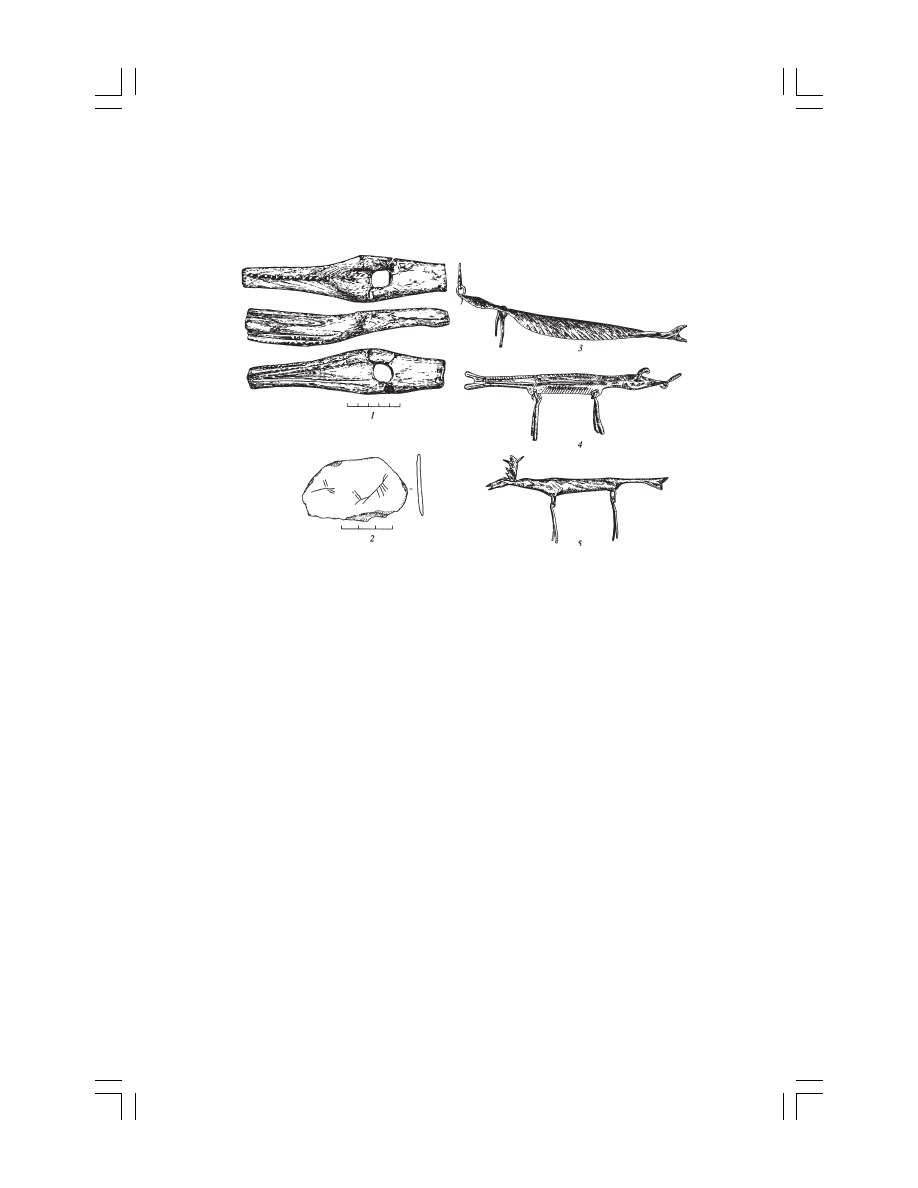

(see Figure 1, 3–5).

c

For example, a Yukagir shaman had an at-

tachment with an image of a mammoth that he used to summon

spirits. Among the shaman’s helper spirits the mammoth was con-

sidered the strongest. The immense, monstrous animal became an

underworld spirit at the shaman’s beck and call. The shaman re-

sorted to his aid during his journeys in the underworld when he

battled other shamans (Ivanov 1949, pp. 140–46). In Selkup my-

thology, the mammoth was considered the forefather of all wild

animals in nature. It was the spirit of the origins of everything, a

symbol of undying eternity. It is possible that this is precisely why

old shamans required of their spirits that for their service to the

shamans the spirits transform the shamans into mammoths [kvoli-

kozar] for a certain number of years (Golovnev 1995, p. 508).

d

Figure 1. Images of mammoths in archeology and ethnography.

1—a figured hammer from the Shigirsk peat bog; 2—a slab of stone with

engraved images from Cape Laisk;

3–5—depictions of mammoths on

pendants on an Evenk shaman’s costume (according to S.V. Ivanov).

14

ANTHROPOLOGY & ARCHEOLOGY OF EURASIA

Another reason the bones of extinct animals are found particu-

larly on monuments dedicated to religious matters may be the be-

lief of ancient peoples in the supernatural power of ancient objects.

The ethnographic study of the Ugrians provides numerous examples

of indigenous people attributing archeological finds to the world

of supernatural powers. Some cases are known of shamanic use of

archeological artifacts, considered fetishes that increased a

shaman’s strength (Gemuev and Sagalaev 1986, pp. 109, 175). It

has also been suggested that one of the reasons that graves were

robbed in ancient times was due to a desire to possess objects that

had been to the world of the dead (Khudiakov 2000, p. 43).

Images of mammoths are rarely found among images of other

animals. Not all such images have been identified. S.V. Ivanov,

who has studied the sculpture of Siberian peoples, said that people

not infrequently think the bones and tusks of mammoths are the

remains of a giant animal that lives underground or underwater.

Inhabitants of Siberia and the Far East believed the mammoth was

a hybrid creature, usually attributing to it traits of familiar ani-

mals. For example, the Evenki depicted the mammoth in the form

of a fish with elk antlers (Figure 1, 5). The Khanty believed that

the mammoth was an underground reincarnation of the elk, the

pike, and the bear. On attaining a very advanced age, these ani-

mals did not die naturally but withdrew beneath the earth and were

transformed into mammoths [muv-khora]. The Selkups had a mam-

moth-beast [surik-kozar] and a mammoth-fish [kvoli-kozar]. Thus

images of mammoths can be very hard to recognize.

An example of this is a figured hammer of elk horn found at

Shigir peat bog. On the elongated part of the hammer two incon-

spicuous bumps are intended to represent eyes, its maw is half-

open, extending almost the entire length of the face; notches around

the edge of the mouth opening indicate teeth (Figure 1, 1). It is

thought to be a depiction of some fantastical animal. In the opin-

ion of D.N. Eding, this hammer is an indicator that images of

fantastical animals existed in the Urals (1940, p. 61). It might be a

depiction of a mammoth-pike.

Another such example might be a find, apparently dating to the

early Iron Age, discovered in a sacrificial site at Cape Laisk (Serikov

SPRING 2005

15

2002, p. 144). This is a slab of serite shale, 6

× 3.5 cm in size, on

which two figures are engraved. One looks like a bird in flight,

while the other is more enigmatic. It is indisputably some sort of

animal: scratched lines represent the torso, four legs, a horned head,

and a cleft tail (Figure 1, 2). This figure strongly resembles a mam-

moth as the Siberian peoples portrayed them, according to ethno-

graphic data (Figure 1, 5).

A curious aspect of the use of the mammoth image in religious

practices of the ancient population has been suggested by S.E.

Chairkin. He believes that the shape of the entrance to the Lakseisk

Cave resembles a mammoth and proposes that this was an addi-

tional reason that the cave served as a sanctuary (Kosintsev and

Chairkin, 2000, p. 168). It is rather difficult to accept this supposi-

tion, since during the Holocene Era peoples of the Urals and west-

ern Siberia did not know what the mammoth looked like. Suffice

to recall that the first scholarly work on the mammoth was pub-

lished by Tatishchev in 1725 and that the first complete skeleton

of a mammoth was not found until 1808. Arguments about the

outward appearance of the mammoth have raged since 1831, when

a first reconstruction was made public, and continue to this day.

e

It is appropriate to note here that S.V. Ivanov divided all ethno-

graphic depictions of the mammoth into two types: eastern and

western. Depictions of the eastern type are relatively realistic, be-

cause local people knew of discoveries of mammoth carcasses. As

for the western areas (including Lakseisk Cave, which Chairkin

discussed), images of the mammoth were generally purely fantastic.

Thus, archeological data indicate that the bones of extinct ani-

mals (and the mammoth especially) were used infrequently, but in

all locales, by ancient peoples of the Urals and Siberia for varied

religious purposes. We can say with relative certainty that a cult of

the mammoth existed in various Holocene eras. In many cases the

image of the mammoth is related to shamanic cosmogony (Serikova

2001, pp. 26, 27). With time it is possible that new evidence will

give us a basis for considering mammoth bones in burial sites as

an indicator that shamans are buried there. It is possible that fur-

ther work in this area will provide grounds for interpreting the

depictions of fantastical animals as images of mammoths.

16

ANTHROPOLOGY & ARCHEOLOGY OF EURASIA

Editor’s notes

a. The concept of a three-part cosmology is widespread, not only for Siberia.

For example, Ob-Ugrian concepts of the three worlds correlate with other cir-

cumpolar cosmologies, while Sakha (Yakut) concepts relate to other Turkic groups.

See also Felix Guirand, ed., Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology (London:

Batchworth, 1959), and the recent Encyclopedia of Uralic Mythology series, ed.

Anna-Leena Siikala, Vladimir Napolskikh, and Mihaly Hoppal (Budapest:

Akademiai Kiado; Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2001).

b. The “even” in this sentence refers to O.N. Bader’s scholarship during So-

viet times, when religious explanations for particular sites and objects were

downplayed and making sacrificial offerings was considered superstitious and

retrograde. Nonetheless, throughout the Soviet period, a specific, secretive lore

among archeologists themselves, as well as local workers and ethnographers,

revolved around the need for special respect at sacred sites. Respect sometimes

included token offerings (food, ribbons, coins) by archeologists to the spirits of

local, deceased ancestors and shamans. The personal peril of archeologists who

removed objects from grave sites was renowned in the lore of local Khanty and

Sakha (Yakut) communities, as I have learned since the 1970s from my own

fieldwork. Spiritual concerns have caused many indigenous scholars to stay away

from the archeology of grave sites.

c. For more on shamanic cloaks (not “costumes” for those who wore them),

see especially E.D. Prokof’eva, “Shamanskie kostiumy narodov Sibiri,” Sbornik

Muzeia Antropologii i Etnografii, no. 27, pp. 5–100. See also the Siberian

(Bering Sea area) collection from the Jesup Expedition of the American Mu-

seum of Natural History in New York: http://anthro.amnh.org/anthropology/

databases/jesup/.

d. This interpretation derives from Andrei Golovnev, whose source is N.P.

Grigorovskii, “Ocherki Narymskogo Kraia,” Zapiski Zapodno-Sibirskogo Otdela

Russkogo Geograficheskogo Obshchestva, 1882, bk. 4, pp. 1–60. Significantly,

in Selkup concepts, the flesh of the mammoth after death was thought to harden

into stone, possibly a reference to finds by indigenous peoples of buried frozen

mammoths, well before scientists found them. As I discovered during fieldwork

in 1991, western Khanty of the Kazym area also have stories of finding large,

buried frozen, fantastical creatures, probably mammoths.

e. Chairkin’s correlation of the Lakseisk Cave with the shape of a mammoth

may well be fanciful. But the explanation given here, that people knew what a

mammoth looked like only after the first scholarly publication on the subject,

does not refute his suggestion. We are not in a position to know the iconographic

imagination of ancient worshipers at the Lakseisk Cave.

References

Anisimov, A.F. “Shamanskie dukhi po vozzreniiam evenkov i totemicheskie

istoki ideologii shamanstva.” In Sb. MAE [Sbornik Muzeiia Antropologii i

Etnologii], 1951, vol. 13.

SPRING 2005

17

Baber, O.N. “Zhertvennoe mesto pod Pisanym kamnem na r. Vishere.”

Sovetskaia arkheologiia, 1954, vol. 21.

Eding, D.N. “Reznaiia skul’ptura Urala.” Tr. GIM [Trudy Geograficheskogo

Istoricheskogo Muzeiia], no. 10. Moscow, 1940.

Gemuev, I.N., and Sagalaev, A.M. Religiia naroda mansi (kul’tovye mesta

X–nachala XX v.). Novosibirsk, 1986.

Golovnev, A.V. Govoriashchie kul’tury. Traditsii samodiitsev i ugrov.

Ekaterinburg, 1995.

Goriunova, O.I. Drevnie mogil’niki Pribaikal’ia (neolit-bronzovye vek).

Irkutsk, 2002.

Ivanov, S.V. “Mamont v iskusstve narodov Sibiri,” Sb. MAE, 1949, vol. 11.

Khudiakov, Iu.S. “Ispol’zovanie kostei pleistotsenovykh zhivotnykh

naseleniem Saiano-Altaia v drevnosti i srednevekov’e i zadachi okhrany

pamiatnikov paleontologii.” Sokhranenie i izuchenie kul’turnogo naslediia

Altaia, no. 12. Barnaul, 2000.

Kosintsev, P.A. “Zhertvennye zhivotnye iz sviatilishcha Khaliato I.” In

Problemy kul’turogeneza i kul’turnoe nasledie.

Mater. k konf. Arkheologiia

i izuchenie kul’turnykh protsessov i iavlenii. St. Petersburg, 1993.

Kosintsev, P.A., and Chairkin, S.E. “Kul’tovye peshchery Urala.”

Sviatilishcha: arkheologiia rituala i voprosy semantiki. Mater.

tematicheskoi nauchn. konf. St. Petersburg, 2000.

Okladnikov, A.P. “Neolit i bronzovyi vek Pribaikal’ia,” Materialy i

issledovaniia po arkheologii, 1955, no. 43, Part 3.

———. Neoliticheskie pamiatniki Angary. Novosibirsk, 1974.

———. Neoliticheskie pamiatniki Srednei Angary. Novosibirsk, 1975.

———. Neoliticheskie pamiatniki Nizhnei Angary. Novosibirsk, 1976.

“Poniatiia sibiriakov-prostoliudinov o mamontakh.” Tobol’skie gubernskie

vedomosti, Tobolsk, 1859.

Prokof’eva, E.D. “Mamont po predstavleniiam sel’kupov,” addendum to the

article by S.V. Ivanov, “Mamont v iskusstve narodov Sibiri.” Sb. MAE,

1949, vol. 11.

Serikov, Iu.B. “Shamanskie pogrebeniia kamennogo veka Zaural’ia.” VAU

[Vestnik arkheologii Urala], 1998, no. 23.

———. B.“Shamanskie pogrebeniia kamennogo veka,” In 60 let kafedre

arkheologii MGU im. M.V. Lomonosova. Tez. dokl. iubileinoi konf., posv.

60-letiiu kafedry arkheologii ist. f-ta Mosk. gos. u-ta im. M.V.

Lomonosova. Moscow, 1999.

———. “Atributy shamanskogo kul’ta.” Trudy Mezhdunar. konf. po

pervobytnomu iskusstvu, vol. 2. Kemerovo, 2000.

———. “Novye dannye o peshchernom sviatilishche na reke Chusovoi.”

XV Ural’skoe arkheologicheskoe soveshchanie. Tez. dokl. mezhdunar.

nauch konf. Orenburg, 2001a.

———. “Vtorichnoe ispol’zovanie izdelii preshestvuiushchikh epokh.”

XV Ural’skoe arkheologicheskoe soveshchanie. Tez. dokl. mezhdunar.

nauch. konf. Orenburg, 2001b.

———. “Proizvedeniia pervobytnogo iskusstva s vostochnogo sklona Urala.”

VAU, 2002, no. 24.

18

ANTHROPOLOGY & ARCHEOLOGY OF EURASIA

———. “Mamont v kul’tovoi praktike drevnego naseleniia Urala i Sibiri.”

Materialy XXXIII Uralo-Povolzhskoi arkheol. studencheskoi konf.

Izhevsk, 2001.

Serikova, A.Iu. “Poza pogrebennogo kak odin iz pokazatelei ego sotsial’noi

znachimosti.” In Uch. zapiski Nizhnetagil’skogo gos. ped. in-ta. Ser.

Obshchestvennye nauki. vol. 2, pt. 2. Nizhnii Tagil, 2002.

Tatishchev, V.N. “Skazanie o zvere mamonte.” In Izbrannye proizvedeniia.

Leningrad, 1979.

Valk, S.N. “O sostave izdaniia.” In Izbrannye proizvedeniiia, ed. V.N.

Tatishchev. Leningrad, 1979.

Vasilevich, G.M. “Iakyzovye dannye po terminu ‘khel-kel.’ ” Addendum to the

article by S.V. Ivanov, “Mamont v iskusstve narodov Sibiri.” Sb. MAE,

1949, vol. 11.

Vereshchagin, N.K. Zapiski paleontologa. Leningrad, 1981.

Vereshchagin, N.K., and Tikhonov, A.N. Ekster’er mamonta. Yakutsk, 1990.

To order reprints, call 1-800-352-2210; outside the United States, call 717-632-3535.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

FIDE Trainers Surveys 2012 08 31 Uwe Bönsch The recognition, fostering and development of chess tale

Xylitol Affects the Intestinal Microbiota and Metabolism of Daidzein in Adult Male Mice

Preliminary Analysis of the Botany, Zoology, and Mineralogy of the Voynich Manuscript

Walker The Production, Microstructure, and Properties of Wrought Iron (2002)

Decoherence, the Measurement Problem, and Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics 0312059

the effect of water deficit stress on the growth yield and composition of essential oils of parsley

The Conditions, Pillars and Requirements of the Prayer

Motyl Imperial Ends, The Decay, Collapse and Revival of Empires unlocked

Guide to the properties and uses of detergents in biology and biochemistry

A picnic table is a project you?n buy all the material for and build in a?y

Catcher in the Rye, The Book Analysis and Summary

Spanish Influence in the New World and the Institutions it I

93 Team Attacking in the Attacking 1 3 – Crossing and Finis

improvment of chain saw and changes of symptoms in the operators

The main press station is installed in the start shaft and?justed as to direction

Impacting sudden cardiac arrest in the home A safety and effectiveness home AED

Pearson Archeology of death and Burial Eating the body

The problems in the?scription and classification of vovels

Catalogue of the Collection of Greek Coins In Gold, Silber, Electrum and Bronze

więcej podobnych podstron