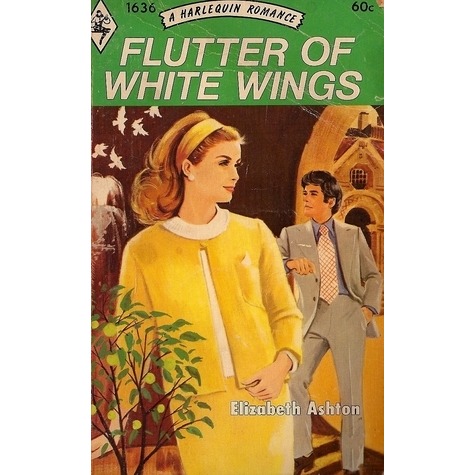

FLUTTER OF WHITE WINGS

Elizabeth Ashton

Catherine

remembered a song about journeys ending in lovers' meeting, but a

lover was the last thing she expected to meet in Seville.

Had

she not been named for St. Catherine, who was the patroness of single

women and seamstress? And yet, in her heart, did she not believe that

the mysterious serenade on her first night at the Casa Aguila had

really been played for her-'Cor' sin amor'- 'heart without love?

She

was to find out.

CHAPTER ONE

'So you are leaving us to go out into the world, my daughter. It is, I must warn you, a very wicked place!' There was a twinkle in the Prioress's black eyes, which belied the severity of her words, as she looked at the girl standing before her in her plain, conventual uniform, but Catherine Carruthers did not see it. Her eyes had strayed to the barred window of the austere little room through which she could see the tops of trees, tipped with bursting buds, and a spray of almond blossom pink against a sunlit blue sky.

'But very beautiful, Reverend Mother,' she said.

'Where every prospect pleases and only man is vile,' the Prioress quoted drily, 'but you will have a staunch protectress against man's vileness in your good mother, Catherine. Obey her wishes in all things, for she has been very generous to you, though I don't think I need to remind you of that.'

'Indeed you needn't,' Catherine returned, flushing slightly. 'I shall always be eternally grateful to her, and one day perhaps I shall have a chance to repay her for all her kindness.'

For Edwina Carruthers was not her real mother, she was her aunt. Her own parents had died together in an accident when she had been only five years old. At that tender age, frightened, bewildered and bereft, she had been put into an orphanage. Edwina was a writer of successful travel books, and she wandered the five continents in search of copy, seeking to assuage her own loss of both husband and baby daughter. She had returned from half-way across the world to rescue the unhappy little girl, taking her to her cottage at the foot of the Pyrenees, which was her pied-a-terre. There for over three years she had devoted herself entirely to consoling, teaching and cherishing the desolate child. As she grew older, Catherine began to realise how much she owed to this aunt, her only relative, who had given her affection when she needed it most, an anchor when her whole world had collapsed, and her name, for Edwina had adopted Catherine as her own daughter to fill the place vacated by baby Caroline's premature decease at the age of one year.

When Catherine was nine, she was sent to the Convent of the Sacred Heart for more progressive education. She went as a boarder so that Edwina could be free to follow her own pursuits during term time, but the widow always returned to the cottage for the holidays, the house being cared for during her absence by a French couple, Pierre and Marie Leroux, who both adored the child. There Catherine spent long, happy days in her adopted mother's company, exploring the countryside and learning to ride the two hacks the widow kept for that purpose, but they never mingled with the people of the neighbourhood, nor did the girl find much companionship among the pupils at the Convent School. She was the only boarder, a concession granted by the Mother Superior because of her unusual circumstances, and the other girls always left for a more sophisticated education upon attaining eleven years, only Catherine stayed on during her teens. She loved the gentle nuns, and had once thought she would like to join their Order. This idea Edwina had discouraged, though she was too wise to directly oppose her, and in due course Catherine realised that she had no real vocation. She had grown to womanhood completely sheltered from all the turmoil and rebellion of modern youth, unaware that Edwina had a purpose in insisting upon this seclusion. The Prioress had been taken into the widow's confidence, and she looked compassionately at the girl's meekly bowed brown head, wondering if the woman to whom Catherine owed so much had acted quite fairly towards her niece, for Edwina had emphasised that she wished Catherine to be kept away from all disturbing influences, and to be trained in self-discipline, obedience and the housewifely arts, because her destiny was to fill a position where these virtues would be important. Suspecting that the girl had no suspicion of the fate mapped out for her, the Prioress said insinuatingly,

'So you propose to occupy yourself assisting your mother, don't you? You are to accompany her upon her travels?'

'Yes, I'm looking forward to that. I'm hoping to see lots of new places,' the girl's face was eager, 'and I'm sure I can help by transcribing Edwina's notes,' she smiled. 'She writes an appalling hand, but I'm used to deciphering it.'

'Yes, she does,' the Mother Superior agreed, having had experience of Edwina's calligraphy. 'Do you call her by her first name?' There was a hint of reproof in her voice.

'She asked me to do so, Reverend Mother, now I'm older, she says it's a modern practice.' Neither knew that Edwina had always shrunk from hearing the maternal appellation upon Catherine's lips. That name belonged to dead Caroline, an odd touch of sentimentality in a woman who prided herself upon having no nonsense in her make-up.

'I see.' The elder woman hesitated, then asked bluntly, 'Then you have no thought of marriage?'

Catherine looked blank. 'No,' she said. 'Who would want to marry a plain creature like myself?'

Personal vanity was not encouraged at the convent, and her idea of feminine beauty was the conventional fair hair, blue eyes and insipid prettiness. She knew she was not pretty, her face had too much character, and her colouring was ordinary. What she did not know was that she could, upon occasion, look beautiful. 'Besides,' she went on, 'I'm named for Saint Catherine, who you have told me is the patroness of sempstresses and spinsters, so I feel I'm destined to be a spinster, and a prop to Edwina's old age.'

The Prioress sighed. Catherine had never given any trouble, but she was no spineless puppet. There was resolution in the firm chin, a hint of passion in the soft curves of her mouth. She thought the girl had the makings of a fine woman if she were allowed to develop normally. Had Edwina Carruthers any right to seek to hand her over to a husband not of her own choosing with her youth untried, her wings still furled? Might she not rebel against the fate ordained for her? It was to be hoped the rebellion would occur before, not after the marriage.

'You will always have a refuge here,' she said, 'if you find the world too wicked.'

Catherine smiled serenely. 'I daresay I can cope with it, Reverend Mother,' she said confidently.

'With God's help, my daughter,' the nun said piously.

'I rely upon that.'

The Prioress gave her the short homily which she felt was her duty to bestow upon her departing pupil, at the end of which Catherine knelt for her blessing, trying to realise that this was the last time that she would do so. Rising to her feet, she stammered out her thanks for all that had been done for her. The Mother Superior for all her gentleness was always so remote that she had never lost her awe of her. Again the nun sighed.

'I only hope, my daughter, that in the days to come you will not blame us for not giving you a more sophisticated education. It was your mother's wish, not ours.'

'I'm sure I'll never do any such thing,' Catherine declared warmly, and took her leave. She lingered in the cloister, looking at the statue of her Saint, which was enshrined there, and smiled calmly down upon her from her niche. She tried to trace a likeness to herself in the carved features, but there was none. The artist who had modelled the statue had made her look insipid; she hardly suggested the strength to endure a martyrdom.

Catherine passed on to the refectory where the Sisters were gathered to bid her farewell. They gave her as a parting present a little silver crucifix upon a chain, and she fastened it around her neck with appropriate thanks. The convent door opened for her for the last time and she went out to the waiting taxi. A phase of her life was ending, but she would never wholly eradicate the convent influence that had governed her early years.

Edwina Carruthers had been born and bred in Southern Spain, her father had been a partner in the wine business that centred in Jerez. She and her much prettier younger sister, Catherine's mother, had lived in Seville. Prominent among the family's friends were the Aguilars, who also lived in that town. Edwina had become intimate with Juana de Aguilar, and fell desperately in love with her much older husband, Salvador, being drawn together by their mutual love of horses. Edwina had always been a fearless rider, and Salvador had a stable full of white Andalusian horses. In a guarded way he returned her feeling, but as both were virtuous, nothing came of it. Over the years, their affection ripened into a life-long friendship. Don Salvador had for this downright, plain, clever Englishwoman a respect and admiration that he did not extend to his own countrywomen. She had what he admired most, an intrepid courage. When she subsequently married Simon Carruthers and Caroline was born, they sought a vicarious fulfilment by planning to betroth the infant to Don Salvador's grandson, Jose. Caroline had died, but Edwina saw no reason why Catherine should not take her place when the time came. Arranged marriages were very much de rigueur with the ageing Don, and Catherine would have a dowry from her own resources.

The Don agreed, albeit with reservations. Jose, as he grew up, became something of a disappointment to his grandfather, who had lost two sons in an ill-fated mountaineering expedition for the glory of Spain. He had none of his father's dash and daring. If Caroline had lived, and had inherited her mother's intrepidity, she would have supplied what Jose lacked in the next generation, but Catherine was not Edwina's real daughter, she had yet to prove herself. Knowing that Don Salvador was a reactionist, clinging to the old ways, and disliking intensely emancipated women, Edwina had sent Catherine to the convent to be trained to be a submissive Spanish wife. She gave the girl no hint of her intentions, that might set her against the plan, but once she was in Seville, a guest of the Aguilars, with Jose prepared to woo her (so she hoped), it was highly probable that the unsophisticated young girl would fall for the first presentable young man with whom she had been brought in contact. Propinquity, Edwina thought, should do the trick, and she had been careful that Catherine should in the meantime meet no possible rivals.

Edwina had arrived back from a trip to Crete too late to collect Catherine, but was present to welcome her when she arrived. As the hired car drew up, she ran out eagerly to greet her. After they had embraced, she stood back to eye her critically. Catherine was of medium height, slim built and graceful. Her grey eyes were clear and candid under well-marked brows. Though there was nothing remarkable about her features, she had a lovely bloom in her cheeks and her short, bobbed hair was the colour of a ripe chestnut, but her plain grey dress and travel coat did nothing to enhance her looks. All her clothes were plain and serviceable. Edwina had no dress sense, and her trim figure always looked well in the tweeds she normally wore, so that she had left the selection of Catherine's wardrobe to the nuns. She was more concerned with the girl's character than her appearance, and as she looked modest and unsophisticated, Edwina thought she would favourably impress Don Salvador, and that was what was important to her.

'You're too thin,' she said abruptly, thinking Jose would prefer more curves. 'Did they starve you at the convent?'

'Of course not!' Catherine laughed. 'Though naturally, as it's Lent, we didn't feast.'

'We're going to feast now, Lent or no Lent,' Edwina announced. 'Marie has prepared a really sumptuous repast for your return, and if you don't do it justice, you'll hurt her feelings.'

'I'd hate to do that,' Catherine declared, 'and the journey has made me quite hungry.'

Marie Leroux greeted her rapturously and she too exclaimed about Catherine's thinness.

'You are the skeleton,' she announced. 'You need my cooking to put more meat on your bones.'

'I don't think I'm any thinner than usual,' Catherine pointed out, 'and I understand it's fashionable to be slim.'

'But now you are the young lady, you need the embonpoint,' Marie persisted, who had more than enough of her own. 'The jeunes hommes, they like not to sleep with a bag of bones.'

Catherine coloured faintly, while Edwina said sharply, 'That will do, Marie.' Her housekeeper had all the peasant's crudeness of expression, and that she had been thinking along similar lines herself did not excuse the woman's forthrightness, and she had noticed the wild rose blush in Catherine's cheeks.

'Young men don't interest me,' the girl said lightly. 'There'll be too much else to do.' She glanced fondly at Edwina.

'But you're no longer in a convent,' the widow pointed out, hoping Catherine had quite got over her desire to be a nun.

After their meal, she produced her notes and sketches; she was writing a book about Minoan culture.

'The bull,' she remarked, 'was a sacred animal in Crete. I fancy the Minotaur must have been a special one to whom human sacrifices were offered, and the bull dances are the origin of the Spanish corrida, though they were more like the Provencal course libre, in which they play with the bull but never kill it. Bull culture is one of the oldest in the world.'

Becoming aware of a stiffening in Catherine's attitude, she looked up from her papers to ask, 'What's the matter?'

Catherine had a passionate love for all animals. She endowed them with human feelings and emotions, so that their tribulations often caused her more pain than that suffered by the victims, and the mention of the corrida had offended her.

'I hope you'll never want me to go to Spain,' she said. 'Spaniards must be horribly cruel.'

'Oh come, don't be absurd. You can travel ail over Spain and never see a bullfight. In any case it's giving place to football as a national sport. As a matter of fact, we are going to Seville for Easter. My old friend Don Salvador de Aguilar has asked us both to attend his elder granddaughter's wedding.'

Catherine had heard all about the Aguilars. She knew the family consisted of the old man, his widowed daughter-in-law, Luisa, and his grandchildren, Inez, Jose and Pilar. From all she had been told Don Salvador de Aguilar y Miranda was a formidable personage, being a grandee of the old school, stubborn in his efforts to put back the clock and a stickler for maintaining the customs of his country. She had seen a photograph of Dona Luisa and her two eldest taken at the time of the children's confirmation. Inez was demure-looking in a white dress with a veil on her head, and Jose looked incredibly devout in a sailor suit. Dona Luisa beamed behind them in black, but Don Salvador was not included in the picture, and the mental one she had formed of him was intimidating. She had no wish to meet him, particularly as he owned, in addition to his home in Seville, a ganaderia on the Andalusian plains where he bred fighting bulls. Though she had looked forward to travelling with Edwina, she was not expecting to have to fulfil a social engagement. She was naturally shy, and the idea of being precipitated into a strange family was frightening. She said bluntly,

'I don't want to go. They don't know me and I don't know them. Couldn't I stay here with Pierre and Marie while you're away? I don't mind being alone.'

'Of course you must come,' Edwina declared. 'They want to meet you and it's time you made their acquaintance— besides, a little young society will do you good. Of the three younger people, Pilar is nearest your age, the others are older. You'll like Pilar, she's a charming girl.'

Catherine looked down, twisting her hands together. 'But you told me Don Salvador owns a bull farm. I ... I can't condone...'

'Oh, rubbish!' Edwina was annoyed. 'You know nothing about it. The animals on the farm are pampered creatures, but there'll be no occasion for you to go near it if you don't want to. Do you expect me to say to my friend, my daughter won't visit you because you breed the cattle your ancestors have bred for generations, and one or two find their way into the ring? He'd think you're a stupid little prig, and so you are.'

Catherine flushed and hung her head.

'What you will see,' Edwina went on, 'are the religious processions during Holy Week, and although they're becoming commercialised they're still unique. Your convent training will have taught you to appreciate them.' She continued to enlarge upon the beauties of Seville, the flamenco dancing and singing, which she would be taken to see, the gracious way of life that was still preserved at the Casa de Aguilar, until Catherine's imagination was fired, and she forgot her hostility, though she still felt anxious about meeting the Spanish family.

'By the way, how's your Spanish coming on?' Edwina broke off to enquire.

'Not very well... it's the speaking. I can write it a little.'

'Oh well, not to worry,' Edwina said cheerfully. 'The way to learn a language is to go to the country of origin, and all the Aguilars speak English. Honestly, they'll be delighted to welcome you, Kit, as they say in that country, their house is yours.'

'And they know you're my adopted mother?'

'Only Don Salvador knows that, but it's not important. You're my sister's child, and I'm your next of kin.'

A curious constraint fell between them. Edwina's relationship to Catherine had become like that of a much older sister, and she had never been really maternal. The ghost of little Caroline stood between them. Catherine could dimly remember her own parents, remembered more sharply the awful feeling of desertion that had swept over her when she had lost them. Edwina had saved her, Edwina wanted her to go to Spain to meet her friends; the least she could do was to fall in with her wishes.

'I'll come,' she said, 'and I'll do my best not to disgrace you.'

'I don't think you'll do that,' Edwina said, and laughed.

It was a fine spring morning when they set forth for Spain in Edwina's car, in which she always travelled, a day of white clouds against a blue sky, with trees and flowers awakening to verdant life. Catherine's spirits rose, for she was on the road at last, about to visit a new country, with all its width to explore and wonder about before she had to face the awe-inspiring Aguilars.

They crossed the frontier at Irun into what was still Basque country, with little difference in the scenery and beret-crowned people, who were a short, stocky, independent race, about whom Edwina had already written, but the language was different, and instead of the tricolour flag, they were welcomed by the scarlet and gold of Spain.

The run down to Madrid was uneventful but cold, colder than the French spring that they had left behind them. Catherine, who had visions of warmth and hot sun, was unpleasantly surprised. Vittoria, which they passed through, was reputed to be the coldest town in Spain and lived up to its reputation by greeting them with a snowstorm. They slept at Burgos, one of the oldest cities in the country, and Edwina insisted that Catherine must see the cathedral in which was buried Roderigo Diaz y Bivas ... El Cid, campeador. The girl was overawed by the great Gothic pile with its truly Spanish interior, crammed with rejas, sculptures and rich embellishments, the candles before the effigies making pools of light amid its sombre magnificence. She found it oppressive; she seemed to glimpse the dark, secret soul of Spain, and a sense of foreboding assailed her.

There was snow on the Sierra Guadarrama, though the road was clear, and from the heights of the pass they could look over the almost treeless plain to Madrid. That night they reached the capital.

After they had dined, Edwina went to ring up the Aguilars to tell them that they hoped to arrive in Seville by the next evening. Catherine waited for her in the lounge of the very anglicised hotel with a mind full of uneasiness. The hour of her ordeal was fast approaching. Edwina came back from the telephone and laughed at her dismal expression.

'You aren't going to be hanged, my lamb,' she told her. 'You're going to have the time of your life, but we'd better go to bed. We've over three hundred miles to do tomorrow, if we're to reach Andalusia by nightfall, and I bet you won't be sorry to reach journey's end.'

Inconsequently Catherine remembered a song about journeys ending in lovers' meetings, but a lover was the last thing she expected to meet in Seville. No romantic-looking Spaniard was likely to even look at Catherine Carruthers, a mercy for which she was grateful. She had no notion of what she would say to him.

The sun was shining when she awoke next morning, and her forebodings of the previous night had dissipated. She supposed she had been overtired, and she bathed and dressed in a mood of eager anticipation. She wanted to see Andalusia, which Edwina had told her was what most people thought of as Spain, a land of Moorish buildings, fluttering fans, flamenco and hot sunshine. So far they had seen little of the famous southern sun.

Coming into the dining-room, she was surprised to find Edwina in conversation with a young man, who was seated at their table. They were both talking in Spanish, and as she moved towards them quietly over the tiled floor, the flow of sonorous syllables were audible but incomprehensible to her. She stood hesitating, wondering if she should venture to interrupt them, when Edwina looked up and saw her.

'Good morning, Kit. This is Senor Cesar Barenna. Senor, my daughter Catherine.'

The young man sprang to his feet in one quick lithe movement and bowed from his hips.

'Delighted to meet you, Senorita Carruthers.'

Catherine muttered something inaudible overcome by bashfulness; she had no experience of young men. She noticed with slight surprise that this one spoke English without a trace of accent. Self-consciously she sat down in the chair, which Cesar, forestalling the waiter, pulled out for her, and as he seated himself again opposite to her, she surreptitiously glanced at him from under her long lashes. Tall for a Spaniard, he had a narrow, high-bred face with a straight nose and dark eyes fringed with magnificent eyelashes. The mouth was long and flexible, with a slightly sardonic twist, his hair was like black silk. He was casually dressed in a sweater and slacks, an unusual garb for a Spaniard, Madrilenos do not lightly dispense with jackets and the waiters were eyeing him with discreet disapproval. Though used to tourist eccentricities, they deplored them in a fellow-countryman. So also did the neatly suited fellow guests, but Cesar was impervious to their critical glances. He held himself with an easy arrogance, his whole slender figure vibrant with life and energy, and the lazy, appraising look he gave Catherine was disconcerting. Uncomfortably she realised that the two-piece which she was wearing was more serviceable than smart, that her face was innocent of make-up and her hair unfashionably cut. There were several chic, painted young women in the dining-room with whom she felt that she must contrast unfavourably in this man's eyes, unaware that she possessed a freshness and simplicity which made them look jaded.

'Senor Barenna is a cousin of the Aguilars,' Edwina explained, 'he has come to stay with them to ... er ... learn the trade ... isn't that what you said, senor?'

'Please call me Cesar,' he asked, 'yes, I've come over to see how Don Salvador runs his ganaderia, and to take some stock back to our ranch in Argentina. Though of Spanish extraction, I'm actually an Argentine, senorita.'

'Oh,' Catherine said vaguely, having no preconceived ideas about South America and its denizens.

'He has travelled up from Seville to meet us, Don Salvador was distressed to think of two lone females making such a long journey unescorted.' Edwina's hazel eyes twinkled as she gave this explanation; she had toured much wilder places alone and was amused by his concern, but she was not amused by Cesar Barenna's appearance. If he made an impression upon Catherine, it might upset all her schemes. She had counted upon Jose de Aguilar having no rivals.

The waiter brought coffee and Catherine realised with dismay that the other two had already breakfasted. 'I'm afraid I'm late,' she apologised.

'No, we were early,' Cesar said courteously. 'The Senora Carruthers would not let me wait for you, and I must admit I was ravenous.'

'The poor boy has been travelling all night,' Edwina explained, whose good nature was stronger than her dismay at Cesar's arrival. Cesar spread his hands and shrugged his shoulders, a foreign gesture.

'It was nothing, I often travel at night and the rapido runs smoothly—besides, I've business to transact for Senor de Aguilar, so I'm making of it a combined operation. If you'll excuse me now, I'll perform my errand and then I'll be free to accompany you.'

'We've a little shopping to do,' Edwina told him, 'so we'll meet you in the Plaza Mayor for a glass of wine. That's a place Catherine ought to see while we're here.'

'Certainly she should,' he agreed, and again his appraising, audacious glance swept over the girl. 'Hasta la vista.'

He bowed and left them with a lithe, catlike tread that made no sound on the tiled floor.

'He'll take his turn at the wheel,' Edwina said, 'which means that we'll make better time and we needn't be in a hurry to be off. I hope he isn't staying long at the Casa.'

A sentiment that Catherine silently endorsed. There was something oddly disturbing about Cesar Barenna, and she had been dismayed to learn that he was to be their travelling companion. She had no experience of men, especially young ones, and he embarrassed her. The waiter placed a plate of ham and eggs in front of her—Edwina considered the continental breakfast of rolls and coffee insufficient sustenance for a day on the road—and she began to eat it.

'What are we going to buy?' she asked without much interest.

'Since there are some excellent shops here, I thought we might get you one or two new outfits,' Edwina told her. 'The Reverend Mother hasn't much idea of style, so we'll find something a little more chic.' She had suddenly realised that Catherine needed something more modish than her present wear to impress her friends and was anxious to repair her omission.

'Is that necessary?' Catherine asked doubtfully.

'Definitely. I can't have you looking a dowd when we get to Seville.' She had noticed the amused glint in Senor Barenna's eyes when he had looked at Catherine and guessed his thought. The girl must be re-clad before she met her hosts. At least Cesar had done her one good turn by drawing attention to her oversight.

The Gran' Via had excellent shops, and for immediate wear, under the saleswoman's guidance, Edwina bought a green suit with black trimmings, the jacket of which could be discarded if the heat became too great en route, and insisted that Catherine should dispense with her serviceable grey in its favour. She also bought a handsome silk negligee of an oriental design, which seemed to Catherine to be almost wicked in its sensuous magnificence. To her half-whispered protest, Edwina said brusquely,

'You're not at the convent now.'

After buying several other garments, they left their purchases and Catherine's old clothes to be packed and delivered to their hotel, and repaired to the Plaza Mayor. The sun was so warm it was possible to sit at one of the cafe tables set out on the cobbles, and Edwina ordered vino bianco. The square retained much of its medieval atmosphere, being surrounded by four-storey buildings with arcades at ground level. They were decorated with iron balconies and grey shutters against brown and pink stucco. The dark slate roofs were full of dormers, their line broken by square towers with steeples and weather vanes.

While they sipped their wine, they saw Cesar crossing the square and, perceiving them, his face broke into a charming smile ... too charming, Edwina thought sourly, fearing its effect upon Catherine. She also saw appreciation in his glance as he took in the girl's changed appearance, and Catherine's answering blush, but he was too polite to make any comment. Instead he talked about the square in which they were sitting.

'This plaza is full of history,' he told them. 'It was designed for fiestas, bullfighting and auto-de-fes. Philip IV built it in 1619. From a balcony on the north side he used to watch the spectacles.' He stole a glance at Catherine, who had shivered at the mention of bullfights and auto-de-fes. As in Burgos Cathedral, she became oppressed by something sinister in her surroundings. This place had witnessed too much blood and pain. Unthinkingly she said,

'The Spanish are a cruel people ... I mean they were,' she hastily amended.

'And still are, in some ways,' he returned, 'but to give them their due, they have their reverse side. It's not necessary in Spain to have a society for the prevention of cruelty to children.'

'Touché,' Edwina laughed. 'And now we must really be getting on if we're to make Seville before midnight. I hope they've delivered your parcels, Kit.' She turned half apologetically to Cesar. 'The shops here are so good, we've had a spending spree.'

Again his dark eyes flickered over Catherine. 'I see you made good use of your opportunities,' he said suavely. 'May I congratulate you both ... and the shops ... on the result?'

'Thank you,' Edwina murmured, while Catherine looked away from him. Although he was undoubtedly charming, there was something about him that repelled her. His remark about cruelty lingered in her mind. He could be cruel upon occasion, she felt sure. She could imagine him leaning over the king's balcony watching some poor wretch burn with just that same slightly sardonic smile that he was wearing at that moment. He might call himself Argentinian, but the Spaniard was predominant in him, and she suspected dark depths which she hoped she would never have to plumb.

They drove out of Madrid with Cesar at the wheel and Edwina sitting beside him. He drove fast and well, threading his way skilfully through the urban traffic. The country was smiling after the spring rain and not yet scorched by the summer heat. They passed through green farms and gardens, but when they came to the tableland of La Mancha all that was changed. The road ran straight across an arid plain, land too sun-struck, too long devegetated to be fertile. Practically treeless except for an occasional drift of olive trees with gnarled trunks and pewter-coloured leaves, wheatland stretched from horizon to horizon, but in places it was sheer stony desert, mile upon mile of lunar landscape, grim and stark. The people they passed scratching a meagre living from the land were beings from an earlier age, as withered and brown as their forbidding country, the women wearing old-fashioned skirts working alongside the men, while the main source of power was mules and donkeys, the latter treading an endless circle as they manipulated the ancient pumps at the well heads.

'Hasn't changed since the year dot,' Edwina remarked.

'Some day there may be artesian wells and tractors,' Cesar said, 'but it won't be yet awhile, this country is too unproductive to be worth the outlay.'

The sun became hot and he threw off his sweater and rolled up his shirt sleeves, Catherine became conscious of his brown, muscular arms and narrow sinewy hands that gripped the steering wheel so firmly. She could see nothing else except his smooth black head, and against her will, her eyes kept returning to him from the monotonous view upon either side of them. She too had discarded her jacket, beneath which she had on a white frilly blouse. Cesar seemed completely tireless, and chafed when Edwina insisted upon stopping to rest and take refreshment from the picnic basket she had had stocked for them.

'We still have far to go,' he pointed out.

'We've plenty of time for a siesta,' she said.

'Siesta? Bah!' He snapped his fingers. 'You and the senorita can doze as we go along. I don't need any rest and I'm tired of this endless plain. It depresses me—no wonder Don Quixote was mad, or so I understand. I've never managed to get through that classic.'

'No more have I,' Catherine admitted from the back seat, but she had been briefed about the doleful knight. 'All I know is that he tilted at windmills, of which I see there are still a few about.' They had just passed a row of them.

Cesar looked sombre. 'Some of us still do,' he remarked, 'and of course the windmill always wins.'

There was bitterness in his tone, and she wondered what obstacle stood in his path to call forth that remark. Edwina had her way, and they stopped, the culminating argument being that the engine needed cooling. Catherine was glad of an opportunity to stretch her legs, and they consumed the rolls and ham and the inevitable bottle of wine by the roadside, feeling oppressed by the harsh scenery. Then they were off again with Cesar driving at reckless speed, until Edwina remonstrated with him, for it was her car and she did not want it to be overdriven, nor to fall foul of the Guardia Civil. He immediately checked to a crawl, flashing her a mischievous smile, whereupon she made him surrender the driving seat, and he lolled beside her making occasional comments in Spanish in answer to one of which Edwina said pointedly in English, feeling Catherine was being neglected,

'No doubt in your own country you are used to covering enormous distances at breakneck speed, but this is a British car and built for durability, not pace.'

'Typically British!' he laughed. 'But England is only the size of a pocket handkerchief,' he spoke in the same tongue. 'I know, because I was sent to school there.' Which explained his mastery of the language.

Surprised, Catherine exclaimed, 'I would never have suspected that.'

He turned his head to look at her. 'My school tried its hardest to fit me into the regulation mould, but it didn't succeed.' He laughed. 'Actually I was asked to leave before I'd finished my academic career.'

'Do you mean you were expelled?' Edwina asked bluntly.

'Not exactly,' his eyes danced with mischief, 'it was merely suggested that England had done all she could for me. Oh, I didn't do anything bad, it was just a foolish prank. You see, I can't resist a challenge. On the headmaster's house was a climbing rose reaching nearly to the roof, and I was dared to pick the topmost bloom. I and my friends escaped from our dormitory one night, and while they waited in the garden, I climbed. I obtained the rose, but I had difficulty in descending. They shouted to me, "Cave" and to save myself from discovery I dived in through an open window into what I hoped was an empty room. The occupant, for there was one, switched on the light and I was confronted by the headmaster's daughter. She screeched loud and long and I was caught red-handed, a flower in my hand. My story was disbelieved; because I am Latin, ergo, I must at heart be a Don Juan. My friends might have saved me, but I did not want to betray their complicity. So exit Cesar Barenna from the British scene at the age of seventeen with no regrets. She wasn't even pretty, she wore the most hideous striped pyjamas. She presented no temptation whatever.'

He kept his gaze upon Catherine as he told this preposterous tale with a wicked gleam in the dark depths of his eyes, as if he were wondering how she appeared in her night gear, and remembering the negligee Edwina had bought, she flushed and turned away to look out of the window.

Edwina laughed. 'Do you expect us to believe that improbable yarn?'

"No, but all the same it's true.'

Catherine turned back to say diffidently, 'Isn't it rather stupid to do something wro ... imprudent ... just for a dare?'

'Ah, senorita, it goes deeper than that,' he said seriously. 'Neither boy nor man can refuse a challenge to his manhood.'

Edwina made some flippant rejoinder and the subject dropped, but Catherine was to remember Cesar's words in the days to come.

Edwina was driving when they reached the Sierra Morena, where in places the rugged rocks were a grim, vertical palisade against the sky, and it was she who negotiated the Gorge of the Despenaperros, the ditch of the dog, so called because the Spaniards called the Moors infidel dogs and the Moors reciprocated by naming them Christian dogs. The doggy pass had once been a haunt of brigands, but now a motor road and the railway ran through its dramatic scenery. Again Catherine was aware of a premonition of evil lying ahead of them and was thankful to leave the sinister rockery behind. Then, as the towns became whiter, the soil redder and the trees more plentiful, her dark mood was dispelled in the more genial air of Andalusia.

The sun was setting when they reached the old Moorish caliphate of Cordoba, and Edwina suggested that they should stop for refreshment, an idea Catherine welcomed, for she was stiff with sitting. César at first was all for pushing on, but realising their weariness became agreeable.

'We'll reach the Casa in time for dinner,' he said, looking at his watch, 'that is, if you let me drive,' and he glanced meaningly at Edwina, whose passage of the Sierra Morena had not met with his approval.

'All right, you Jehu,' Edwina laughed, 'but please let us arrive in one piece!'

He found a parking space and announced that he would take them to a posada that was all Old Spain. 'Senorita Carruthers needs to be initiated into Andalusian life,' he said airily.

'Oh, don't be so formal,' Edwina objected, 'call her Kit.'

He shook his head. 'I don't think she's a kitten. Is that really your name, senorita?'

'It's short for Catherine,' the girl said coldly.

'Ah, Catalina, I like that better.'

Catherine was inclined to remark that his preferences had not been consulted when she was christened, but checked the words on her tongue. She was too tired to care what he called her, though she shrank from the intimacy of this Spanish Don Juan using her first name. He came round to open her door, and ignoring his outstretched hand, she tried to alight with dignity, but her cramped limbs betrayed her. She stumbled and would have fallen if he had not caught her. For the first time in her life she was in close contact with a man, a man, moreover, who was intensely masculine and virile. She was almost painfully aware of the strength of the arms supporting her, the lean, dark face so close to her own, and the blood surged through her veins.

'Careful, Senorita Catalina, you are numb with sitting,' he warned her, and his voice was a caress. Aware that she was blushing, she hastened to withdraw herself.

'Thank you, I'm all right now,' she said hurriedly.

He drew her arm through his. 'Better let me support you until you've found your feet.'

She sensed that he was fully aware of her embarrassment and it seemed to amuse him. The arm she clung to perforce was strong and sinewy. It flashed through her mind that to always have a man's strength to lean upon must be a wonderfully sustaining prop, but such things were not for her, it was her destiny to be Edwina's prop when she declined into old age, not that Edwina looked much like declining for a long while yet. In spite of the long gruelling journey, she was stepping out briskly. Guided by Cesar, Catherine moved self-consciously down the side road that he indicated, with the widow upon her other side. Then they turned into a calle so narrow that they could not walk three abreast, and he fell back to allow her to precede him, but she had forgotten him in sheer wonderment. The alleyway led between white-walled houses with delicate wrought-iron balconies and outside each one of them hung quantities of potted plants fixed to the walls, like an aerial garden, while the balconies themselves were filled with fern and flowers. The scent of jasmine, violets and orange blossom enveloped them, and the walls glimmered palely in the blue dusk. Ahead a white arch crossed the calle, beyond it was another, and at the far end rose an illuminated tower hung with bells. Involuntarily she exclaimed, 'But how beautiful!'

'It's only one of Cordoba's ancient alleys,' Cesar said indifferently.

'It doesn't appeal to you?'

'I'm jealous, where I come from the ancient buildings are massive blocks of stone. There's nothing graceful and enchanting like this.'

Enchanting was the right word, Catherine thought, a magic prospect where only man was vile, but Cesar was not vile, rather his presence added to the witchery of the night —she checked herself, reminding herself that she was not sure that she liked him.

They walked down the narrow, cobbled street, turned at the bottom of it and passed a gate of fine tracery through which could be glimpsed a tiled patio in which a fountain played, illuminated by the lights from the house, and on to a cobbled plaza with orange trees and little tables set out before a lighted cafe front from which came the thrum of a guitar and the wail of a flamenco tune.

Cesar ordered for them manzanilla, the drink of Andalusia, a kind of light sherry. It came in thick-bottomed, narrow tumblers and though very dry was light and refreshing. It went slightly to Catherine's head, for she was unused to wine. She was no longer embarrassed by Cesar's bold glances and met his eyes with a frank, clear gaze, so that it was he who dropped his regard. The long black lashes made inky crescents on his olive face, between the high-bridged nose. Then he lifted them and looked long into her clear, grey orbs, with a dark, penetrating stare. Neither spoke; some subtle communion seemed to be passing between them, a questing to discover what lay behind the other's facade.

I'm dreaming, Catherine thought, none of this is real. I shall wake up and find myself back at the convent.

Edwina drained her glass and rose briskly to her feet.

'Time we were off,' she announced. 'Wake up, you two!'

Catherine's gaze strayed to a Moorish arch on the further side of the plaza, but Cesar was still watching her. In the dim light she looked younger and softer and the wistful droop of her lips was pathetically childish. Her face was palely luminous in the dusk, framed by the darkened wings of her hair. Vulnerable, he was thinking, and untouched, very different from the brash self-confident tourist girls with whom he was only too familiar. She fitted her surroundings, for she was like a girl of Old Spain, a girl who had been allowed to have no contact with the world of men and so had preserved her innocent bloom. Edwina's voice recalled him from his musings, and he jumped up.

'At your service, Senora Carruthers,' adding curiously, 'Pardon me, but was your daughter educated at a convent?'

For only in a nunnery could a modern girl retain such unsophistication.

Catherine answered for Edwina. 'How clever of you,' she smiled. 'I was.'

'She's only just left its shelter,' Edwina added, with a note of warning in her voice. 'She's had no experience of the ways of our wicked world.' The nuns had not taught Catherine how to deal with men like Cesar Barenna.

'Ah, that accounts for the out-of-this-world look,' Cesar remarked as they started to walk away, with this time Edwina between them.

Catherine laughed. 'I'm not a ghost, you know,' she said, Tm still with you,' and I think the wine must be making Senor Barenna fanciful.' It had also made her bold, and the look she gave him was a challenge. She felt exhilarated, not only by the manzanilla but by the magic of this romantic southern land and the expression in Cesar's velvet eyes.

CHAPTER TWO

It was dark when the travellers arrived at the Casa de Aguilar. Catherine stared at the windowless shoulder it presented to the street, in which was set a wrought-iron gate, and thought it looked forbidding. Certainty it gave no indication of the gracious interior, with which she was later to become familiar. It was situated in the oldest part of Seville and was built upon the remnants of a Moorish palace.

'Looks a bit grim from the outside,' Cesar remarked, as they drove into the cobbled courtyard, from which a flight of steps led up to the huge, brass-studded front door, above which the windows were small and heavily grilled. 'The people who built it liked to keep themselves to themselves— but don't be alarmed, senorita, although from this approach it looks like a medieval fortress, and Don Salvador dislikes modern inventions, he has installed plumbing, electric light and the telephone, though not, alas, central heating.'

'You don't mean he still uses braseros?' Edwina asked, as Cesar cut the engine, and at his nod, explained to Catherine that braseros were brass or copper bowls filled with charcoal, and were usually located under the table so that the family's feet could be warmed at meal times. 'But we shouldn't need them at this time of the year,' she concluded thankfully.

Cesar ran up the front steps and pulled the iron bell rod beside it. In the flickering light from the light above it, he looked to Catherine's tired eyes immensely tall and a little sinister, and matched the house, which she thought had the appearance of a prison. She felt extremely reluctant to enter it and meet its inhabitants. The door was opened by an aged manservant, who led them into the tiled hall and then went to summon his minions to unload the car. The immense vestibule went through the width of the house and at its further end was open to a patio through an arcade of Moorish arches. The lights from the house shone out on to tubs of orange trees, and sparkled on the jet of a fountain in a marble basin. Marble too was the wide staircase ascending to the upper floors. The thick outer walls shut off all noise from the street, and over all hung the silence of ages. She felt as if she had stepped into a scene from the Arabian Nights.

The silence was broken by the patter of high heels and from one of the passages that ran right and left of the vast hall, Dona Luisa de Aguilar came hurrying to greet them. She wore black, which she had assumed upon her widowhood and would never discard again. She was short and plump with grey hair, above an amiable, placid face. She almost ran on her tiny feet to embrace Edwina.

'Amiga mia, you are welcome, and this is the daughter about whom you have told us so much. At last we meet.'

Catherine was a head taller than Luisa, but, undeterred, the Spanish woman rose upon her toes to embrace her, and Catherine stooped to receive a kiss upon either cheek. 'Cesar, go tell el senor that his guests have arrived,' she called, 'he will want to receive diem,' and as Cesar disappeared down a tiled passage, she went on, 'The years take their toll, you understand. Is not what he was, mi padre.' She sighed prodigiously. 'Has been all day at the ganaderia, and is tired, but still he is indomitable.' Her English was heavily accented, and she often mislaid the pronoun, which is rarely used in her own tongue.

Indomitable was the operative word, Catherine thought, as their host came towards them. He was not tall, only a bare inch or so more than her five foot five, but so proudly did he hold his head, and so straight was his spare figure, that he gave the impression of height. The snow-white hair, still plentiful, crowned a narrow face with a long upper lip and thin mouth, but it was the eyes that gave life to it. Dark and brilliant, deep-set under beetling brows, nothing missed their piercing gaze. He wore a small, carefully trimmed imperial, and black evening clothes, the short jacket long outdated, with a snowy shirt and cummerbund. He looked, and was, an autocrat, and not a benign one. He kissed Edwina's band, and shook Catherine's ... unmarried girls did not rate a kissed hand ... and in excellent English, bade them welcome.

'My house is yours.' Which statement, Catherine thought, only a fool would take literally. Then maids were summoned—there was no lack of domestics—to conduct the ladies to their rooms and, saying that they would meet before dinner, Don Salvador departed, holding Cesar affectionately by the arm.

To her great relief, Catherine found her room was next to Edwina's. It was a large, square apartment, with a high ceiling, the tall window opening on to a balcony that overlooked the patio. The furniture was sparse, a dressing table, a huge wardrobe, a high, old-fashioned bed, one chair and a couple of mats on the polished wooden floor. The white walls were unadorned except for a picture of the Madonna and Child over the bed, and the heavy wooden door had a latch on a ring. The little Spanish maid proceeded to unpack Catherine's clothes, but communication was impossible except by signs, Catherine's few Spanish phrases being defeated by the Andaluz dialect the girl spoke. She exclaimed over the clothes that Edwina had bought in Madrid, and hung them reverently in the wardrobe. Then Edwina came in and selected a dress for her to wear at dinner, a long princess-shaped gown in pale blue nylon.

'You mustn't be surprised to find all the others are in black,' she told her. 'Lent is very rigorously observed here, and during Holy Week they wear nothing else.'

'How many will there be for dinner?' Catherine asked nervously. She felt more like bed than a dinner party, the day seemed to be going on for ever.

'That remains to be seen. The girls and Jose, of course, but how many odd relatives are visiting, I couldn't say.'

Keeping well behind Edwina, Catherine entered the sola where the family were assembled to await the dinner bell, a meal which never appeared much before ten o'clock, and was often later. There was more kissing and hand-shaking. Inez de Aguilar, the bride-to-be, was dark and plump with magnificent eyes, Jose had brown hair and eyes set in a sensitive face, but Pilar, the younger girl, was pure Castilian. Catherine was astonished to be confronted by golden hair above great dark eyes; she had a matt cream-coloured skin, and was a beauty, her looks marred by her discontented expression. Contrary to Edwina's expectations, there was only one other guest, Ricardo Laralde, Inez's fiancé, a short, plump man with oily hair.

Jose enquired politely about her journey in good English, though he did not speak as idiomatically as Cesar, and Pilar broke in excitedly,

'Oh, how I envy you, senorita, to be able to travel alone across Spain. It is the freedom only foreign girls may have.'

'Senorita Carruthers was not alone,' Jose pointed out, 'her mother was her duenna.'

Pilar glanced at Edwina, who was deep in conversation with Don Salvador.

'That one is not like a Spanish mother,' she announced, 'but how brave you were to travel all those miles without a man. They say there are still wolves on the sierras near Burgos.'

'We didn't see any,' Catherine told her, glad that she had not known this at the time. 'The worst we experienced was a fall of snow.'

'Snow? We have that here perhaps once in fifty years. Senorita, I long to see the world!' Pilar fixed anguished dark eyes on Catherine's face. 'But Mamma will not stir from Sevilla. I must wait until I marry, and then, quien sabe, it will be just as bad. I shall be expected to stay in the house and produce los ninos.'

Catherine, who was unused to such plain speaking, blushed faintly, while Inez, who had overheard, turned upon her sister.

'You talk like the baby, Pilar. No woman want more than the good husband and the children. Me, I shall be happy to have both.' She gave Ricardo a languishing glance, and he bowed with his hand upon his heart. Jose said pacifically, 'It is hard for Pilar, Inez, to see everywhere the turistas enjoying freedom while she must observe the old rules,' and Don Salvador, who, it seemed, took notice of what was going on, whoever he was talking to, broke off his conversation with Edwina, to say shortly,

'Freedom is licence. If I permit Pilar to run wild, what would she become?'

Pilar's eyes sparkled and a wild rose flush stained her face. 'A woman, Abuelo,' she declared, 'instead of a piece of merchandise to be sold to the highest bidder.'

The Don's heavy eyebrows drew together, while Catherine was horrified to realise that pretty little Pilar would not be allowed to choose her mate. Edwina had mentioned marriages of convenience to her, but she had not until now understood the full implication. She would have been still more horrified had she any inkling that her adopted mother was contemplating arranging one for herself.

Don Salvador's reprimand was never uttered, for at that moment the manservant threw open the door, announcing that dinner was served. The old man offered his arm to Edwina, while with a bow, Jose presented his to Catherine. Ricardo gallantly escorted Dona Luisa while the two girls brought up the rear of the little procession, for Cesar had not yet appeared. As they went across the hall from the sala to the dining-room, Jose said apologetically,

'Pilar is very young and a little headstrong; she does not realise that a woman needs to be cherished and protected.'

Catherine said nothing, though it occurred to her that neither Edwina nor herself had a male to cherish and protect them and they managed very well without, but in Spain, female independence was not encouraged.

The heavy refectory table was covered by a damask cloth and lit by candles in branched candlesticks. Don Salvador sat, not at the head, but half-way down one side, with Edwina on his right and Luisa on his left. Catherine found herself opposite to him, between Jose and Inez, who had Ricardo beside her. Then Cesar came in and her heart missed a beat, for he looked so distinguished in formal dress and older, quite different from the boyish young man who had entertained them in Cordoba. He murmured an apology and sat down beside Pilar, who at once lost her discontented look and engaged him in animated talk. So that way sets the wind, Catherine thought, watching the black head inclined towards the golden one, and was conscious of a slight pang. I'm tired, she told herself; it's been a long day. It could not possibly be that the sight of Cesar's absorption in Pilar was causing her distress. She had not yet known him for twenty-four hours, though the long journey in the car had ripened their acquaintanceship, but it was only an acquaintanceship, and several times during it, she had felt that she disliked him. She heard the Don say to Edwina,

'Tomorrow you and your charming daughter will like to rest, but on tie day after I go to Valdega to visit the ganaderia, and I hope you will both accompany me. There are improvements that I wish to show you.'

'We shall be delighted to do so,' Edwina replied, and Catherine looked at her reproachfully. So although her mother had assured her that she would not have to visit the place, she was arranging to do so, almost as soon as they had arrived.

'We have some very fine animals this year,' the Don went on. 'They are being rounded up to make the selection for the corridas, of which, as you know, there will be many after Easter. It will give you an opportunity to see them.'

Catherine turned cold. She said quickly, 'I had much rather stay at home, if you don't mind.'

Mistaking the reason for her refusal, Jose said reassuringly, 'You need have no fear, the animals are all securely penned:'

'I'm not afraid of them, or of any animal,' she returned, 'but ... but ... they're destined for the bullring, aren't they? I may as well confess here and now that I loathe the corrida and I don't want to see anything that has the remotest connection with it.'

There was a moment of complete silence while every pair of eyes was focussed upon her—and she was worth looking at; her passionate repudiation of the spectacle had caused colour to rise in her pale cheeks and her grey eyes to flash. Catherine at that moment was beautiful, and there was appreciation in the looks with which all three young men were regarding her, while Senor de Aguilar's expression was almost comical in its surprise, but it was Pilar who flew to the defence of her country's national pastime.

'You speak like an ignorant fool!' she cried, her eyes blazing. 'You have never been to one ... no? You do not know how the emotions are stirred from the first bars of the paso doble to the moment of truth ... and the brave men who pit their cunning against the brute's strength, they are heroes. I cannot conceive an honour greater than to receive the dedication of a matador!'

Catherine stared at Pilar in horror. That such a lovely, dainty creature could not only attend the corrida but defend it seemed to her unbelievable.

'I didn't know that women went to bullfights,' she said faintly.

Cesar laughed. 'Women are a lot tougher than men in some respects,' he said a little scornfully, 'but Pilar only goes in the hope that some handsome torero will let her display his dress cape and guard his montera. She's not really interested in the proceedings.'

'Why should I not enjoy the homage of brave men?' Pilar returned. 'And they are men who have proved their courage, and not just talked about it.' Her eyes taunted him.

Cesar reddened and exclaimed angrily, 'One of these days I'll show you ...'

'You will not,' Don Salvador intervened. 'Kinsmen of noble houses do not demean themselves before the public in the arena.'

'I'd certainly hate to have to do so,' Cesar confessed. 'One thing I learned at my English school was to respect fair play.'

'Even though in England they hunt the fox?' Don Salvador asked silkily.

Cesar reddened again. 'But Reynard has a chance of escape, and often does so,' he said Shortly.

'And many British people deplore blood sports,' Edwina pointed out.

'Chicken hearts,' the Don growled in his beard.

'Cesar has perhaps a little of the chicken heart,' Pilar said archly, and Catherine again stared at her. What was she trying to do? Goad her lover to some rash act to feed her vanity? That she was succeeding was evident from the furious look Cesar bestowed upon her. She responded to it with a little giggle, and turned to her grandfather.

'I would not attend the corrida if you would let me enjoy more modern recreations,' she told him. 'Carlos Fonseca's father promotes the football and is opening lidos and dancing halls for the turistas. Carlos has asked me many times to go with him to sample them, but always you say no.'

'And shall continue to do so,' he said sternly. 'Fonseca makes a lot of money, but he is no caballero, nor will I have you mingling with the turistas. I am told the Ingles dance cheek to cheek!' He looked pained at the thought of such depravity.

Cesar, who had recovered his temper, turned his audacious glance upon Catherine. 'Do you dance so?' he enquired. 'It must be quite delightful.' His eyes lingered meaningly upon her soft face in which the blood was rising, as she dropped her eyes in confusion.

'I ... I do not dance at all,' she murmured, 'at least not that sort of dancing.'

She had learned folk dancing during her holidays, but she had never danced in a man's arms.

'Catherine has not been brought up to modern freedoms,' Edwina said repressively, giving him a stern look. Cesar looked at his plate.

'A pity,' he observed, and Don Salvador sought to quell him with a frown.

'Basta, enough,' he said shortly. 'You all talk much foolishness.' He turned to Catherine. 'Nevertheless, senorita, whatever your prejudices, I trust you will be courteous enough to accompany the senora your mother when she comes with me to Valdega. The farm is a very pleasant spot, and I presume you will admit that cattle have to be raised for many different purposes.'

There was a steely glint in his deep-set eyes and Catherine knew that she had displeased him. While she was wondering what she could say to placate him, Edwina interposed.

'Of course she'll come. Don Salvador has some fine horses, Kit, which I'm sure you would wish to see.'

'I ... I'd like too,' Catherine capitulated, realising that she had no option, and she wished that she had complied at once without drawing so much attention to herself.

When the meal was over and they had gone back to the sola, it seemed to her that the family avoided her. Cesar was monopolised by Pilar and Edwina was again deep in conversation with the Don. She went to the floor-length window that was open to the night and looked into the patio, wondering if the Aguilars ever went to bed. If she had not been so tired she would not have allowed herself to be so provoked at dinner. Jose approached her with a little deprecating smile.

'I do not care for the corrida myself,' he told her, 'but I dare not admit it to Abuelo, hp believes it expresses the soul of Spain.'

'A dark soul!' she exclaimed involuntarily, then laughed self-consciously. There I go again! I am too outspoken, am I not?'

His brown eyes were regarding her kindly.

'Candour is not a bad thing,' he told her, adding with a little shrug, 'There are too many undercurrents in this household.'

That she could well believe.

When at length they did retire, Catherine found the business of saying goodnight was a ritual. She was expected to shake each man's hand and kiss each woman's cheek. Don Salvador held her slim fingers for several moments, while he looked her up and down.

'When you came in I thought you were a mouse of a woman,' he said with a twinkle in his deep-set eyes, 'but during dinner I discovered that you could roar like a lion.'

'I... I hope I didn't offend you,' she faltered.

He laughed and patted her hand. 'Not at all, my dear. I am glad to see that you have a fighting spirit. So many in this house have not.' He glanced contemptuously at his grandson, and Catherine wondered in what poor Jose had failed.

César barely touched her hand and seemed abstracted, his eyes on Pilar, even while he murmured, 'Goodnight, sleep well.'

Edwina came with her into her room, and Catherine spoke the thought uppermost in her mind.

'Is there anything between Cesar and Pilar?'

'Not officially,' Edwina told her. 'Of course he's in love with her, that sticks out a mile, but all the young men who visit the Casa pay homage at that shrine, and it's not to be wondered at. She looks lovelier every time I see her.'

'Yes, she is very lovely,' Catherine admitted, 'but I think she's cruel.'

Edwina laughed. 'Now you're being fanciful! Because she attends the brava fiesta, and most of them do from time to time, it doesn't mean that she's a monster.' She herself was delighted to notice Cesar's infatuation with his host's granddaughter, and even more so that Catherine had marked it. The girl would be too proud to let herself hanker after another woman's man, and Jose had seemed to be attracted.

'I'm afraid you'll have to go to Valdega,' she went on, 'since Don Salvador is set upon it. He's very proud of the place, but you won't see anything objectionable, in fact the creatures are pampered, so there was no need to make such a fuss about it.'

'I thought it was just as well to make my attitude quite plain,' Catherine returned.

'You did that,' Edwina smiled dryly. 'Goodnight, dear, and pleasant dreams.'

But Catherine was restless and over-stimulated and found she was unable to sleep, tired though she was. The room seemed hot and close, so she put out the light, opened the curtains, drew up the slatted blinds and moved noiselessly out on to the balcony beyond. Slender stone pillars rose up to support a roof above her head, twined with creepers that grew up from the ground below. A fretted marble balustrade protected her from the drop beneath her. Edwina's windows were closed and dark; she feared mosquitoes. The room on her other side appeared to be untenanted, and all three had access to her balcony. There were chinks of light from some of the other rooms in the two wings of the house which enclosed the patio, rooms which had small iron, flower-filled balconies outside them. The fourth side, directly opposite to her, was a high, blank wall covered with jasmine and roses, on the other side of which was the old stabling, now turned into garages. A faint glow in the sky above the wall and muted sounds showed that the city was still awake. Below her, the patio was dark, except for the faint gleam of water in the fountain basin, reflecting the starshine. Mingled perfumes of roses, orange blossom and jasmine came up to her.

Something white stirred in one of the orange trees, and murmured a sleepy coo. The patio was the home of several pairs of Java doves. From somewhere in the servants' quarters came the distant throb of a guitar. It was a night for romance, a night for love in this city of Don Juan, but romance had no meaning for her, though she had glimpsed it in a pair of dark eyes at Cordoba, but Cesar was not for her, he was enthralled by the lovely Pilar—She sighed—did that proud beauty appreciate her gifts? Or was it only insignificant creatures like herself who recognised her rich endowment? She did not feel that Pilar was using the power her beauty gave her to the best advantage. Such a woman could be such a good influence, thought convent-bred Catherine, and she felt instinctively that Pilar's influence over Cesar was detrimental.

The lights in the bedrooms were extinguished, the glow in the sky faded. Seville at last had sunk into sleep. Reluctantly she turned to seek her own bed, and then from the patio below her came the thrum of a guitar and a man's voice singing in Spanish, a plaintive gypsy air.

Noche sin luna,

Flor sin olar,

Rio sin agua,

Cor' sin amor.

It only wanted that, she thought scornfully, and went quickly into her bedroom, drawing the curtains over the window to shut out the scented night and the importunate lover, but through her fitful sleep the tune persisted—cor' sin amor ... heart without love ... Would her heart always be empty?

At breakfast next morning, Don Salvador remarked,

'Although I am in favour of retaining the old Spanish customs, I thought the serenade had been dead for the last fifty years.'

He glanced round his assembled family with the suggestion of a twinkle in his eyes. He had spoken in English, as they all did when Catherine was present, deeming it discourteous to use a language she could not wholly understand.

Dona Luisa looked nervously at the deadpan expression on the young men's faces.

'Perhaps it was Ricardo,' she hazarded, and Inez looked complacent at the suggestion, until Pilar said scornfully,

'I cannot think Ricardo would wander round the patio with a guitar. Why should he woo you when you are already won? Besides, how could he get into the patio? He is too stout to climb the wall.'

'My novio is not stout,' Inez was indignant, 'though it is true he is a man of substance.'

Pilar laughed jeeringly, while Dona Luisa said quickly, 'Then perhaps it was the novio of one of the maids. You know they expect to speak with their men every evening.'

'If that is so, Luisa,' Don Salvador said suavely, 'you must insist that they leave at a reasonable hour so that our guests' rest may not be disturbed by such caterwauling.'

He looked keenly at Cesar and Jose, but neither face betrayed a flicker of expression.

'I will see to it,' Dona Luisa promised, but she did not believe in her own explanation, and neither did Don Salvador.

Cesar raised his eyes and caught Catherine's glance and saw that they were full of mischief.

'I'm sure the Senorita Catalina was not disturbed,' he said. 'She would expect no less a welcome from romantic Andalusia.'

Then his glance went to Pilar and Catherine was sure there was meaning in it. Cesar was, as she had suspected all along, the serenader; he had been singing to Pilar and he was trying to use her as a smoke-screen. He had probably seen her light go on when she had re-entered her room and knew that she had been awake.

'Oh, Kit was tired out and would have been sound asleep,' Edwina said brightly, 'as I was. Weren't you, Kit?'

'Of course,' Catherine murmured non-committally.

Pilar was looking as pleased as a cat that was being stroked, though she kept her eyes demurely on her plate. Catherine was sure that she had slept through the musical interlude, and now had just realised what it implied. One thing she resolved, she was not going to be used as a stooge to conceal Pilar's flirtation with Cesar; that was too much to expect from her.

Catherine and Edwina spent the morning idling in the patio, for both were more weary than they cared to admit. The other women went to church; they went most days throughout Lent. All three were dressed in black with lace velos on their heads, small lace caps, for Spanish women rarely wore hats. César left after breakfast for Valdega, and Don Salvador retired with Jose to his own sanctum, but both appeared for lunch, which was the Spanish main meal, after which, refreshed by a siesta, Catherine was ready to go out with Edwina to see something of the city. The enormous Gothic cathedral, third largest in Europe, was their first objective, but she was repelled by the number of tickets they were expected to buy to see this, that and the other. Although it was early in the year, the place was packed with visitors, and a rich harvest was being reaped.

'They must need a packet for its upkeep,' Edwina excused the commerce. The cathedral contained the bones of Cristobal Colon, better known as Christopher Columbus, in an elevated tomb. Here in the city from which he had set sail, he had at last come to rest, when his burial place in the New World he had discovered had passed out of Spanish control.

'Though actually he wasn't Spanish, he was Genoese,' Edwina remarked, 'but I don't suppose they admit that.'

Beside the cathedral was the Giralda, the most familiar sight in all the pictures of Seville, from the lofty summit of which the muezzin had once called the faithful to prayer. The Christians had spared it because of its beauty, but had surmounted its summit with a statue of Faith, which was also a weathervane, hence its name, which meant just that. Inside the top was readied not by stairs but a ramp, up which a horse could be ridden, but they decided they did not feel energetic enough to go up.

Not far away was the Alcazar Palace with its Moorish arches and beautiful gardens, but they gave it no more than a cursory glance, Edwina saying they would explore it upon another day. Finally they went into the Calle de las Sierpes, from which all traffic was barred and awnings were drawn over the street to shade it from the sun. Here Edwina headed for a cafe which she said was one of the two places in the town where they could obtain an English cup of tea.

'And that,' she said after this refreshing beverage, 'will do for today.' Catherine agreed, for already her head was buzzing with new impressions.

Cesar did not appear for dinner and Catherine chid herself when she realised that she was watching for his reappearance. Don Salvador demanded to know where he was, and a sulky Pilar returned,

'I expect he has gone out on the town.'

Her brother looked shocked, and her grandfather thundered,

'What do you know about such matters?'

'Quite a lot,' she informed him. 'Me, I am modern, though you do try to keep me in a zenana.'

'Then you should also know such things are not talked about,' he reproved her, and changed the subject. Catherine knew what Pilar had implied and felt revolted. Cesar then was something of a rake. His glances at Cordoba were now explained; though he owed allegiance to Pilar, his fancy could stray. She firmly resolved to put him out of her mind.

It was he who drove them to Valdega next day in the big Aguilar estate car. Pilar had wanted to come with them, but Dona Luisa insisted that there was still sewing to be done on Inez's trousseau, and since Pilar was an excellent needlewoman, her services were much in demand by her family. She stood with her mother behind her in the doorway of the Casa to watch them drive away, wearing a white frock trimmed with black, and the oblique look Cesar gave her from under his long lashes was calculated to stir any woman's heart as he said,

'Cheer up, Pilar, you may soon be sewing for your own.'

'Madre mia!' Luisa exclaimed. 'She is still a child!'

But the warm look Pilar bestowed upon Cesar was not that of a child but that of a woman ripe for love.

Valdega was situated out on the Andalusian plain some half an hour's drive from Seville. Here among olive groves and wheatlands, cattle and horses fed in the lush pastures running down towards the river, as yet unscorched by the summer sun. The farmhouse was a square, white building with a red-tiled roof. In front of it a group of ilex trees gave some shade and beneath them were set a wooden table and benches. Below it the ground sloped to a number of pens, with high walls and strong gates, with narrow alleyways between them. Behind the farm was a big enclosed yard with stabling and sheds, in the dust of which a number of scrawny barn door fowls were scratching.

Juan Cuerva, Don Salvador's headman, came hurrying to greet them as the car stopped. The bulls, he said, were being rounded up and would shortly be corralled for his inspection. Meanwhile would the senor and his guests honour him by partaking of some refreshment? He spoke the Andaluz patois, which was quite incomprehensible to Catherine and which even Edwina could barely follow. They all sat down under the shade of the ilex trees and Juan himself brought glasses and a jug of Sangria, a kind of fruit cup, mixed with red wine, mineral water and ice, which was very refreshing, while a small, barefooted girl, his daughter, proudly carried a plate of small honey cakes.

Then Don Salvador suggested tactfully that the ladies might like to repair their toilets before going to the pens, from which shouts and bellows were now audible. Catherine followed Edwina, who knew her way about, into the house. Having completed their business in a room that contained no recognisable toiletware, Edwina said she ought to pay her respects to the Senora Cuerva, and led the way into the huge kitchen where the family did its living. Maria Cuerva was frying tortillas over a charcoal stove, surrounded by her brood of dark-skinned, barefoot children. Strings of onions, garlic and several smoked hams hung from the ceiling, the furniture was heavy and crude and the floor stone-paved.

Spanish children delighted Catherine, who found their plump brown limbs, liquid eyes and long black lashes most attractive. The Cuerva collection stood in a row, fingers in their mouths, eyeing her curiously, while Edwina introduced her to their mother. Edwina they had seen before, she was la Inglesa loca, the mad Englishwoman who upon occasion rode Don Salvador's horses like a man, and was always asking questions, but Catherine was something new. A sudden loud yell announced that the latest addition to the family had woken in his wooden cradle and the harassed mother reluctantly left her cooking to pacify him. Catherine impulsively held out her arms and the woman laid the baby into them.

'I expect he wants changing,' Edwina suggested. 'Can you do it?'

Catherine could, though not very expertly, having operated upon Marie Leroux's grandchildren. A nod to one of the little girls produced the necessary articles, and Catherine, sitting down in an old wooden rocker, managed to do the necessary. The baby, now dry and comfortable, settled down in her arms, and intrigued by the strange face, stretched out tentative fingers towards it. The other children, emboldened by her action, gathered round her, babbling excitedly, touching her dress, her bag, even her shoes.

'Senor de Aguilar will be waiting for us,' Edwina protested.

'Couldn't you go?' Catherine suggested, 'and tell him I'm tired, or something.' Nursing babies was a far more congenial occupation to her than looking at cattle. Edwina hesitated and at that moment, Maria exclaimed, 'El senor' and dropped a curtsey, while the children scattered like a flock of frightened starlings, seeking cover behind cupboards and chairs. Catherine remained seated, gently rocking the baby.

'Buenos dias,' Don Salvador said to Maria, followed by some further remarks in the dialect. Catherine became aware that Cesar had followed him. She looked up and found his eyes fixed upon her.

'You make a charming picture, Senorita Catalina,' he said in a low voice. 'With the nino in your arms you look like the Madonna. I thought maternity had gone out of fashion.'

'All women love babies,' she said defensively.

'All women don't, but you, I can see, are everything that a woman should be.'

'I ... I hope so,' she said vaguely, disturbed by the expression in his eyes. Already she had learned that these Latin men were quick to flatter, and she doubted his sincerity, but being unused to compliments she did not know how to counter them. With Cesar, she never knew when he was being admiring or mocking. Don Salvador moved to stand beside him, saying,

'The mother is greatly venerated in this country.'

Feeling acutely embarrassed, Catherine rose to her feet and laid the baby back in his cradle, aware that both men were watching her closely.

'I fear me the Senorita Catalina finds chicos more attractive than bulls,' Don Salvador remarked with a chuckle.

'Isn't that natural?' she retorted quickly.

'It might be an act,' Cesar said coolly.

'But what object would there be in pretending?' she asked, more bewildered than angry. 'Whom do you imagine I'm trying to impress?'

'Quien sabe?' he said mockingly, and turned on his heel, calling to Don Salvador, 'See you at the corrals, senor,' as he went out quickly.