Australian English

• Australian English is a relatively new dialect of

English being just over 200 years old. It began

diverging from British English shortly after the

foundation of the Australian penal colony of

New South Wales in 1788.

• Irish 25%

• The first of the Australian gold rushes, in the

1850s, began a much larger wave of

immigration which would significantly

influence the language. During the 1850s,

when the UK was under economic hardship,

about two per cent of its population

emigrated to the Colony of New South Wales

and the Colony of Victoria.

• Since the 1950s the American influence on language in

Australia has mostly come from pop culture, the mass

media (books, magazines and television programs),

computer software and the internet. Some words, such

as freeway and truck, have even been naturalised so

completely that few Australians recognise their origin.

Some American, British and Australian variants exist

side-by-side; in many cases –

freeway and motorway (used in New South Wales) for

instance – regional, social and ethnic variation within

Australia typically defines word usage.

• Words of Irish origin are used, some of which

are also common elsewhere in the Irish

diaspora, such as tucker for "food",

"provisions" (Irish tacar), as well as one or two

native English words whose meaning have

changed under Irish influence, such

as paddock for "field", cf. Irish páirc, which has

exactly the same meaning as the

Australian paddock.

Types of accent: Broad

• Broad Australian English is recognisable and

familiar to English speakers around the world

because it is used to identify Australian

characters in non-Australian films and television

programmes (often in the somewhat artificial

"stage" Australian English version). Examples are

film/television personalities Steve Irwin and Paul

Hogan. Slang terms ocker, for a speaker,

and Strine, a shortening of the

word Australian for the dialect, are used in

Australia.

General Australian

• The majority of Australians speak with the

general Australian accent. This predominates

among modern Australian films and television

programmes and is used by, for example, Eric

Bana, Dannii Minogue, Hugh Jackman and Mel

Gibson.

Cultivated Australian

• Cultivated Australian English has some

similarities to British Received Pronunciation,

and is often mistaken for it. Cultivated

Australian English is spoken by some within

Australian society, for example Kevin

Rudd, Cyril Ritchard, Errol Flynn, Geoffrey

Rush and Judy Davis.

• Parody:

Phonology (1)

• Centring diphthongs

• Centring diphthongs, which are the vowels that occur in

words like ear, beard and air, sheer.

• In Western Australia there is a trend for centring

diphthongs like the vowels in the words "ear" and "air" to

be pronounced as full diphthongs (i.e. vowels that require

the tongue, jaw and lips to move during their production).

• Those in the eastern states will tend to pronounce "fear"

and "sheer" like "fee" and "she" respectively, without any

jaw movement, while the westerners would pronounce

them like "fia" and "shia", respectively.

Phonology (2)

• e > a

For many young speakers from Victoria, the first

vowel in "celery" and "salary" are the same,

so that both words sound like "salary". The

speaker from Victoria will also tend to say

"halicopter" instead of "helicopter". This

feature is present in New Zealand English as

well.

U > I U

• The vowel in words like "pool", "school" and

"fool" varies regionally. People who live in the

Eastern States tend to say "pool" and "school"

like "pewl" and "skewl", respectively, while the

rest of the Australian population pronounces

them as they are spelt.

Palatalisation

• Palatalisation also typically occurs now in

young speakers

where /tj/, /dj/, /sj/ and /zj/ become

single affricate or fricative sounds

Example:

T > R

• In colloquial speech intervocalic /t/ undergoes voicing

and flapping to the alveolar tap [ɾ] after the stressed syllable and

before unstressed vowels (as in butter, party) and syllabic /l/,

though not before syllabic /n/ (bottle vs button [batn]), as well as at

the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel (what

else, whatever). In formal speech /t/ is retained.

• However, the alveolar flap is normally distinguishable by Australians

from the intervocalic alveolar stop /d/, which is not flapped,

thus ladder and latter, metal and medal, and coating and coding re

main distinct; further, when coating becomes coatin' , the t remains

voiceless, thus [kʌutn]. This is a quality that Australian English

shares with some other varieties of English.

NT > N

• Intervocalic /nt/ in fast speech can be realised

as [n], another trait shared other varieties of

English at the colloquial or dialect level,

though in formal speech the full form /nt/ is

retained.

• winter / winner

• 1999

Linking R

• Non-rhotic: CAR, CARD

• However, the /r/ sound can occur when a word

that has a final “r” in the spelling comes before

another word that starts with a vowel. For

example, in “car alarm” the sound /r/ can occur in

“car” because here it comes before another word

beginning with a vowel.

• The words “far”, “far more” and “farm” do not

contain an /r/ but “far out” will contain the

linking /r/ sound because the next word starts

with a vowel sound.

Intrusive R

• Australian English speakers may also use

intrusive or epenthetic /r/. This is when

an /r/ may be inserted before a vowel in

words that do not have “r” in the spelling. For

example, "drawing" will sound like "draw-ring"

and "saw it" like sound like "sore it".

Bad – lad split

• A long /æ/ sound is found in the adjectives

“bad, mad, glad and sad”, before the

sound /g/ (for example, “hag, rag, bag”) and

also in vowels before /m/ and /n/ in the same

syllable (for example, “ham, tan, plant”).

Nasality

• Nasal consonants can affect the articulation of

the preceding vowel. For some speakers

words like "land", "man", "band", "stand",

"can" and "hand" will contain a vowel that

sounds similar to a long /e/ vowel, which is

the vowel in "head"

•

a good lurk

•

ace

•

aggro

•

Alf

•

amber (fluid)

•

arvo

•

Aussie, Strine

•

chalkie

•

chokkie

•

chook

•

Chrissie

•

comfort station

•

counter meal

•

cut lunch

•

game

•

to gander

•

G'day mate.

•

Good on ya!

•

to grizzle

•

grog

•

gum tree

•

gummy

•

a way of getting something for nothing

•

excellent

•

aggressive

•

stupid person

•

beer

•

afternoon

•

Australian

•

teacher

•

chocolate

•

chicken

•

Christmas

•

toilet

•

pub meal

•

sandwiches

•

brave

•

to have a look

•

Hi.

•

Well done!

•

to whine

•

alcohol

•

Eucalyptus tree

•

a sheep which has lost all its teeth

• Aboriginal English

•

camp

•

mob

•

big mob

•

lingo

•

sorry business

•

grow [a child] up

•

growl

•

gammon

•

cheeky

•

solid

•

to tongue for

• standard Australian

English

•

home

•

Group

•

a lot of

•

Aboriginal language

•

ceremony associated with

death

•

raise [a child]

•

scold

•

pretending, kidding,

joking

•

mischievous, aggressive,

dangerous

•

Fantastic

•

to long for

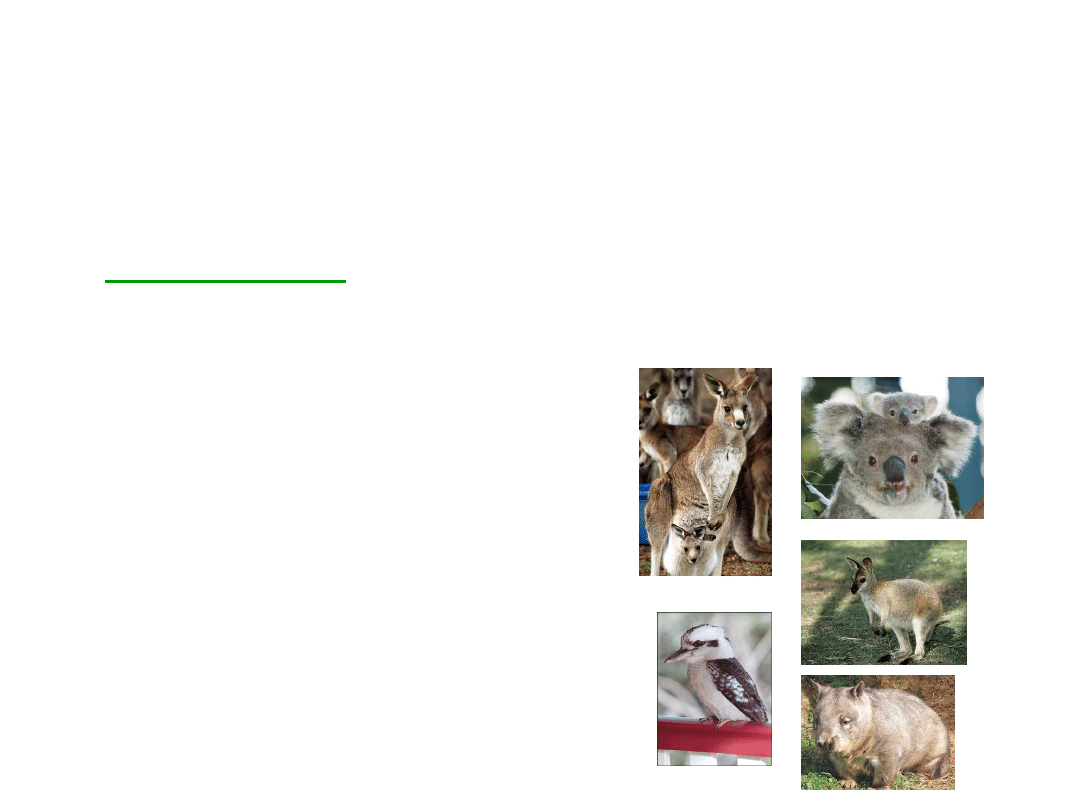

• Billabong

Boomerang

Corroboree

Kangaroo

Koala

Kookaburra

Wallaby

Wombat

Yabber

• Small lake

• Throwing stick

• Ceremonial meeting

HRT

• The high rising terminal (HRT), also known

as uptalk, upspeak, rising inflection or high rising

intonation (HRI), is a feature of some accents

of English where statements have a rising intonation

pattern in the final syllable or syllables of the

utterance. Ladd (1996: 123) proposes that HRT

in American English and Australian English is marked by

a high tone (high pitch or high fundamental frequency)

beginning on the final accented syllable near the end of

the statement (the terminal), and continuing to

increase in frequency (up to 40%) to the end of the

intonational phrase.

• A 1986 report stated that in Sydney, it is used more than

twice as often by young generations as by older ones, and

particularly by women (Guy et al., 1986).

• It has been suggested that the HRT has a facilitative

function in conversation (i.e., it encourages the addressee

to participate in the conversation), and such functions are

more often used by women.

• It also subtly indicates that the speaker is "not finished

yet", thus perhaps discouraging interruption (Allen, 1990;

Guy et al., 1986; Warren, 2005).

• Its use is also suggestive of seeking assurance from the

listener that she is aware of what the speaker is referring

to.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

nexus nowe czasy 2009 (02) 64 żywe dinozaury w australii english

080 Living English Video Series (Australian Network) Dialogues (scripts)

IntroductoryWords 2 Objects English

Australia i Nowa Zelandia

Ekonomiczna analiza prawa własności w ujęciu szkoły austrackiej

NOWE AUSTRALIJSKIE OGNIWA SŁONECZNE

Australia

English for CE materials id 161873

120222160803 english at work episode 2

Australia i Oceania

English, Intermediate Grammar Questions answers

Lesley Jeffries Discovering language The structure of modern English

Lady Australia belaus

Hyd prd cat 2009 english webb

Chirurgia wyk. 8, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat 2 pos

Nadczynno i niezynno kory nadnerczy, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Austral

121024104303 bbc english at work episode 37

więcej podobnych podstron