Queen Liberty:

The Concept of Freedom in the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth

Studies in Central European

Histories

Edited by

Thomas A. Brady, Jr.,

University of California, Berkeley

Roger Chickering,

Georgetown University

Editorial Board

Steven Beller,

Washington, D.C.

Atina Grossmann,

Columbia University

Peter Hayes,

Northwestern University

Susan Karant-Nunn,

University of Arizona

Mary Lindemann,

University of Miami

David M. Luebke,

University of Oregon

H.C. Erik Midelfort,

University of Virginia

David Sabean,

University of California, Los Angeles

Jonathan Sperber,

University of Missouri

Jan de Vries,

University of California, Berkeley

VOLUME 56

The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/sceh

Queen Liberty:

The Concept of Freedom in the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

By

Anna Grześkowiak-Krwawicz

Translated from Polish by

Daniel J. Sax

LEIDEN • BOSTON

2012

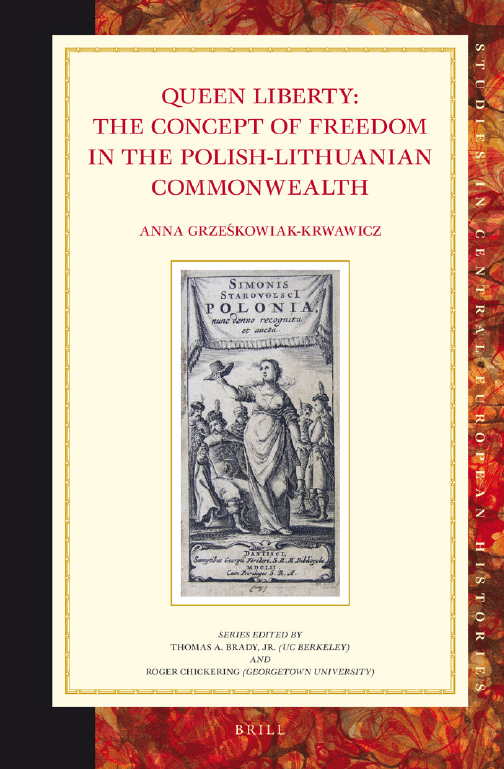

Cover illustration: “Polonia-Libertas,” frontispiece of Szymon Starowolski’s book Polonia, (ed.

Dantisci, Amsterdam 1652), Warsaw University Library, Sd.711.291. With kind permission of the

Warsaw University Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grzeskowiak-Krwawicz, Anna.

Queen Liberty : the concept of freedom in the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth / by Anna

Grzeskowiak-Krwawicz ; translated from Polish by Daniel J. Sax.

p. cm. -- (Studies in Central European histories, ISSN 1547-1217 ; v. 56)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-90-04-23121-4 (hbk. : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-23122-1 (e-book) 1. Poland--

Politics and government--1572-1763. 2. Lithuania--Politics and government. 3. Liberty--History.

4. Nobility--Political activity--Poland--History. 5. Nobility--Political activity--Lithuania--History.

6. Political culture--Poland--History. 7. Political culture--Lithuania--History. 8. Poland--Intellectual

life. 9. Lithuania--Intellectual life. I. Title.

DK4291.G74 2012

320.01’1--dc23

2012022620

This book has been translated from Polish with the kind support of the Muzeum Historii Polski

(Polish History Museum), Warsaw, Poland.

This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters

covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the

humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface.

ISSN 1547-1217

ISBN 978 90 04 23121 4 (hardback)

ISBN 978 90 04 23122 1 (e-book)

Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing,

IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhofff Publishers.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV

provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center,

222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA.

Fees are subject to change.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

CONTENTS

Introduction ................................................................................................................1

1. The Polish Szlachta and Their State .................................................................3

2. Golden Liberty—A Noble Privilege or Universal Idea? .......................... 25

3. The Pillars of Freedom ..................................................................................... 43

4. Freedom in Peril ................................................................................................ 67

5. What Was Wrong with Polish Liberty? ........................................................ 85

6. From Defending Liberty—to Fighting for Liberty ................................. 101

Author Profijiles ....................................................................................................... 121

Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 129

Index ......................................................................................................................... 133

1 H. T. Dickinson, Liberty and Property: Political Ideology in Eighteenth-century Britain,

Methuen 1979, p. 6.

INTRODUCTION

If […] we wish to make sense of the political actions and the political agents

of any past society, then we need to recognize the political values of that

society and understand what that society or sections of it admired and

condemned.1

This book traces the history of a certain idea, which is at the same time the

story of a certain political myth that enjoyed a very long tradition. Its ori-

gins can be sought in writings dating as far back as the 15th century, and in

the 16th-18th centuries it rose to become one of the most important focal

points, if not the centrepiece, of Polish political thought and a core ele-

ment of noble culture. This idea was the main issue in political disputes,

stirring up great emotions over many centuries—serving as a point of

pride, a subject of unreflective apologies and praise, and at the same time

a target of critical analysis, fijierce attacks, and attempts at redefijinition—

and indeed it continues to stir up considerable emotion in Poland to this

very day. This idea is the notion of “Golden Liberty”, as it was known to the

Polish nobles (the szlachta) who were its benefijiciaries.

Polish discussions about this idea are reminiscent of French debates

about the French Revolution—its interpretations are frequently influ-

enced by contemporary events and rarely manage to refrain from passing

some sort of judgment. Whenever this historic Polish species of liberty is

examined, it usually ends up being either fervently defended or vehe-

mently condemned (more often the latter). Such criticism, which appears

in Polish but also foreign writings, has been largely influenced by the

awareness of the eventual crisis and ultimate demise of the Polish-

Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 18th century. This “Polish anarchy” that

was described with such disgust by both European observers and Polish

reformers, that featured prominently in the propaganda of the partition-

ing empires divvying up the Polish lands among themselves as well as in

the writings of the French philosophers who were on intimate terms with

the leaders of those empires, came to symbolize the degeneration of the

Polish nobility and of the state they founded. We can see this as a kind of

2 introduction

myth (or anti-myth?) that took deep root in the European awareness,

including in Poland. As a consequence, opinions about the Polish “Golden

Liberty” are largely dominated by superfijicial judgments and banal, knee-

jerk stereotypes.

And yet “Queen Liberty”, as the concept was once dubbed by one of its

17th-century apologists, certainly deserves more in-depth analysis, sine ira

et studio. At the very least because in a certain sense this notion consti-

tuted, from the 16th century onwards, the very foundation of Polish

thought about the state and about the rightful place of the citizen within

that state. But also, because freedom was not just an idea but a real value

cherished for more than 200 years, enshrined in the laws of the Republic.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth indeed remained a republic of

sorts amidst a Europe increasingly dominated by stronger absolute mon-

archies, and so its ideological underpinnings certainly warrant closer scru-

tiny. Although this state was steeped in a serious crisis of governance in

the 18th century, until at least the mid-17th century it had functioned

smoothly and had been a major player in the European political game—

reifying the republican ideal of external strength in tandem with internal

freedoms (at least as regards some of it inhabitants).

Seeking a deeper understanding of this notion of freedom—probing

the virtues ascribed to it and the threats it was perceived to entail, its gen-

esis and its roots within a certain earlier tradition, as well as the evolution

of the concept over the course of several centuries—will help us to under-

stand not just the attitudes of the Polish szlachta and the principles by

which the noble state functioned, but to some extent also the subsequent

history of Polish society, with its periodic armed uprisings sometimes

interpreted as reflecting a kind of anarchic attachment to the idea of

liberty.

CHAPTER ONE

THE POLISH SZLACHTA AND THEIR STATE

King Sigismund Augustus (Zygmunt August), the last of the Jagiellonian

dynasty on the Polish-Lithuanian throne, died on 1 July 1572. Several

months later the noble deputies who gathered at the Sejm which was to

elect his successor prepared a kind of constitution, laying down the insti-

tutional framework of the Rzeczpospolita, a state commonly known in

English as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (also referred to as the

First Polish Republic or the “Republic of the Two Nations”). This act was

subsequently known as the Henrician Articles, after Henry of Valois, the

fijirst elected monarch coerced into signing it. It provided a legal confijirma-

tion of the fact that this vast country sprawling over more than

800,000 km2 was the possession not of its king, but of its noble estate. Yet

this single act, signifijicant as it was, did not actually mark the beginning of

the history of the noble Republic: it was more the culmination of a certain

stage, representing an efffort to safeguard against any future attempts to

disrupt the existing system of governance or to upset the distinctive politi-

cal consensus that had emerged between the kingdom’s ruler and its

subjects—or to describe the true state of afffairs more accurately, between

the nation’s caste of governors and their co-ruler, since by that time the

szlachta held more of a sovereign sway within their own state than the

king himself.

The history of the szlachta’s rule had in fact begun much earlier, as the

foundations of the noble Republic’s political system stretched back to at

least the 15th century. One might even be tempted to trace it further back

to the personal union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania in 1385, which had imparted a certain preliminary ter-

ritorial shape to the future Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and had

moreover fijirst installed the Jagiellonians on the Polish throne. Seeking to

achieve their own political and dynastic objectives, the Jagiellonian mon-

archs had been forced to make successive concessions to their noble sub-

jects. Throughout Europe, rulers were granting various prerogatives to the

noble estate, or at least to certain strata thereof. But the rights granted to

the Crown nobility in the 15th century by King Ladislaus Jagiello

(Władysław Jagiełło) and then by his son Casimir Jagiellon (Kazimierz

4 chapter

one

Jagiellończyk) did more than just elevate the nobility as a privileged class;

they laid the foundations of civil rights for the nobles. While it is admit-

tedly quite anachronistic to use the term “civil rights” here to describe

these medieval privileges, it nevertheless seems apt in view of the fact that

one of these rights was the famous neminem captivabimus nisi iure victum

privilege (1433), stating that no member of the nobility could be impris-

oned or have his assets confijiscated without a valid court verdict against

him. This was, therefore, akin to the Habeas Corpus Act introduced in

English law nearly 250 years earlier—although in the Polish case it applied

only to a single estate. This right, defending the nobility’s freedom against

unauthorized infringement by the ruler, constituted not just a guarantee

of civil liberty but also the basis for political liberty, since an individual so

protected was free to speak their mind about the ruler’s deeds and policies

without having to fear repression. Successive prerogatives continued to

increase the nobility’s hand in political decision-making—King Casimir

Jagiellon made the concession (in the Nieszawa statutes of 1454) not to

impose any new taxes or to raise an army through levée-en-masse without

the szlachta’s consent. The nobility became increasingly active in self-

governance, encompassing more and more domains of life, and meetings

convened by the szlachta took on greater political signifijicance. At this

stage these were still somewhat informal gatherings of knights from the

province where the king happened to be present, but they marked

the early beginnings of representative self-governance. Although it is true

that a gathering convoked in Piotrków in 1493 is conventionally regarded

as being the fijirst true Sejm of the Polish Crown, i.e. the fijirst representative

body to which the nobles of various lands sent elected deputies, the Sejm

assembly held in Radom in 1505 is undoubtedly a more important water-

shed date in the history of the Polish noble Republic: it was here that the

principle of nihil novi sine omnium consensu (nothing new without the

consent of all) was formulated. This important act of law, adopted and

proclaimed by King Alexander Jagiellon, stated:

Because general laws and public acts apply not to individuals but to the

whole nation, therefore from now on nothing new that would be detrimen-

tal or burdensome to the Commonwealth, or harmful or injurious to anyone,

or that would be intended to alter the general law and public freedom, may

be decided by us [the king] or our successors, without a common consensus

of senators and landed deputies.

This law, later known as the Nihil Novi Act, would become, for nearly

300 years, the foundation of the idea that the state should be understood

as the common good of its citizens, who have the right to determine its

the

polish

szlachta and their state

5

afffairs to a degree no lesser than the monarch himself (and as time passed,

even to a greater degree). The Sejm gained powers of a sort no other estate

assembly enjoyed in Europe: the power to enact laws. It gradually became

not merely a consultative body, debating whether to approve new taxes,

but a legislative body per se—a modern-era parliament. The ruler was no

longer external to it, a sovereign standing above it, but instead became

incorporated into the very fabric of the Sejm itself, as the fijirst of the three

“estates” comprising it. The second estate of the Sejm was the Senate,

which developed out of the Royal Council and was comprised of state offfiji-

cials nominated for life by the monarch (the voivodes, castellans, and

high-ranking offfijicials of the Crown) plus the Catholic bishops. The third

estate of the Sejm was the chamber of deputies elected by the nobility

(also known as the izba poselska or chamber of envoys). The political sys-

tem of the Kingdom of Poland thus became a mixed monarchy. Under the

last two Jagiellonian kings, Sigismund the Old and Sigismund Augustus,

the power of the monarch still remained very great, but he was already a

“king in parliament”. Not only was he subject to the laws of the Republic

like everyone else, no longer standing above those laws, he was moreover

no longer able to enact those laws himself, or at least those which per-

tained to the kingdom as a whole or to the noble estate (although he still

retained the privilege of issuing decrees concerning the status of cities, for

instance). The initially small role played by the chamber of noble deputies

clearly began to increase from the mid-16th century onward, in tandem

with an increase in the nobility’s sense of political strength and responsi-

bility for the future of the state. The last decade and a half of Sigismund

August’s reign was already a time of co-governance between the nobility

and the monarch—and very efffective co-governance at that. This period

saw not only reform of the fijinancial and administrative afffairs of the state,

but also its conclusive unifijication, with Royal Prussia (until then a prov-

ince quite loosely afffijiliated with the rest of the country) being brought

fully into the fold of the Crown, and the Crown plus the Grand Duchy of

Lithuania also being combined into a single political entity. This was a

federative entity: Lithuania preserved its own laws, treasury, and army but

shared a common ruler and Sejm; the Lithuanian nobility gained all the

prerogatives of the Crown nobility as well as full civil rights; high-ranking

Lithuanian offfijicials gained seats in the Senate and representatives of the

Lithuanian nobility sat in the chamber of noble deputies.

It was precisely at this point that the nobility of the Commonwealth

conclusively became a political nation. The uniform privileges and rights

enshrined for the Polish and Lithuanian noble estates at the moment of

6 chapter

one

1 A. Radawiecki, , Prawy szlachcic, Kraków 1625, p. 32

the Union of Lublin (1569) marked the conclusive birth of a single “noble

nation”. A single nation, albeit not a homogenous one. The reader should

bear in mind that the phrase “Polish nobility” used in reference to the

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth or “Republic of the Two Nations”

should be construed quite broadly, as referring to a multinational mosaic

that would only gradually succumb to Polonization over time. It is still

unclear how numerous the “noble citizens” were in the Commonwealth;

the estimates of historians continue to vary and the noble estate is cur-

rently estimated to have constituted 6–8% of all the inhabitants of the

Polish-Lithuanian lands. This is worth bearing in mind when discussing

their political rights—such a relatively high percentage of politically

active citizens did not appear in other European states until the 19th cen-

tury, indeed more towards its latter half. The term nobility, or szlachta, is

here quite imprecise, as the class included both impoverished noblemen

possessed of a single village (or perhaps not even that) as well as mighty

magnates from the south-eastern expanses of the Republic, who might,

like Jarema Wiśnowiecki in the mid-17th century, have more than 200,000

subjects. No aristocratic stratum ever formally emerged from the noble

estate of the Commonwealth. There were no diffferent ranks of nobility,

there were no orders or titles aside from the former Lithuanian ducal

titles. At least in theory, therefore, things stood as the old saying went:

szlachcic na zagrodzie równy wojewodzie—“a rural nobleman on his plot of

land is equal to a voivode” (province governor), and a voivode would

indeed address such a petty nobleman as Panie Bracie, “lord brother”. This

phrasing was meant to underscore both the class-internal equality and the

strong sense of szlachta community. Yet on the other hand, such a rural

nobleman would never in fact have used the same term to address a

voivode, instead referring to him as “His Honourable Lordship” if not “His

Enlightened Lordship”. As Andrzej Radawiecki caustically remarked:

So you have your talk: ‘I am equal’—yet still you do not dare to sue him, ‘I am

free’—yet still you bow to the high and mighty.1

However, despite the fact that things often looked quite diffferent in prac-

tice, equality was one of the values most highly cherished within noble

society and even the most powerful magnates took pains to keep up at

least the appearances of equality. Although in terms of wealth, and thus

likewise in terms of political influence, the notion of equality became an

the

polish

szlachta and their state

7

2 P. Skarga, Kazania sejmowe, ed. J. Tazbir, M. Korolko, Warsaw—Kraków, 1995, p. 33

3 A. Walicki, Idea narodu w polskiej myśli oświeceniowej, Warsaw 2000, p. 21

illusion following the rise of powerful magnates families in the 17th cen-

tury, in the realm of the law it was a reality: the entire nobility legally

enjoyed the same rights and privileges.

These rights and privileges were what bound them together into a sin-

gle noble nation. A nation, as we have mentioned above, that was highly

diverse, at least at the outset of the Republic of the Two Nations. Much has

been written about the distinguishing characteristics of the Polish nobility

against the European backdrop, and such diffferences have often been

exaggerated—but who knows whether, at least in the 16th century, such

diversity may itself have been the Polish nobility’s most distinguishing fea-

ture? The people who described themselves as the “nation”, even as the

“Polish nation”, were in reality an amalgamation of diverse ethnic, linguis-

tic, and religious backgrounds. The noble citizens included not just the

Polish-speaking szlachta of the Wielkopolska (Polonia Major) and

Małopolska (Polonia Minor) provinces, but also the Ruthenian-speaking

nobles of Ukraine, the Rhutenian- Belarusian and Lithuanian (Aukštaitian

and Samogitian) speaking nobles of Lithuania, and even the German-

speaking nobles of Livonia. The traditional division into Catholic and

Orthodox, existing from the 14th century, was further complicated in the

16th century by the arrival of the reformed confessions: Lutherans,

Calvinists, Bohemian Brothers, and Arians, who garnered numerous fol-

lowers likewise among the nobility (aside from the Lutherans). The nobil-

ity was well aware of its internal diffferences. The famous preacher Piotr

Skarga tellingly wrote in the early 17th century that the Commonwealth

consisted of Poles, of Lithuania, of Ruthenia, of Prussians, Livonians, and

Samogitians.2 And yet, irrespective of ethnicity and religion, the nobility

nevertheless considered itself from the 16th century onward to be repre-

sentatives of a single nation. Indeed a “nation”, not just one estate of the

realm. Joint privileges undoubtedly played a great integrating role, but

even more important were the common political rights, the fact that all

nobleman were citizens of a single republic. As Andrzej Walicki pointed

out, the noble nation was a community of individuals who shared not an

ethnic but a political afffijiliation—acceptance of the same political ideals

and a certain system of governance that guaranteed the realization of

those ideals.3 Natione polonus entailed not an ethnic nationality, but

being a co-equal member of the political community known as the

8 chapter

one

4 H. Wisner, Najjaśniejsza Rzeczpospolita. Szkice z dziejów Polski szlacheckiej XVI–XVII

wieku, Warsaw 1978, p. 225.

5 A. Zamoyski, Mowa na sejmie convocationis dnia 16 maja 1764 roku w Warszawie miana,

n. p. (no place of publication) 1764, n. pag. (no pagination).

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This strong sense of community, of

identifying with the political nation, moreover contributed to the rapid

Polonization of the nobility, which was already largely Polish-speaking by

the mid-17th century. This did not stand at odds with an awareness of, or

even the prominent manifestation of ethnic diffferences. Especially the

Lithuanian nobility, despite its rapid adoption of the Polish language,

maintained a profound sense of its own distinct “Lithuanian-ness”, a feel-

ing they repeatedly and variously expressed (such as in the catchphrase

“we, Lithuania”), while at the same time considering themselves members

of the very same nation as the “Lord Poles”.

Members of the same nation and of the same state, as the borderline

here was indeed highly fluid. The noble nation of the Commonwealth

identifijied itself with the state which it resided in and co-governed to a

degree unknown in other countries. Researchers point to a “disappear-

ance of a distinction between the state and society, their mutual perme-

ation”.4 In Polish political discourse, from at least the 16th century, there

was no discussion of any abstract state that stood above its citizens, of the

kind frequently identifijied in the West with state power. In the Polish-

Lithuanian Commonwealth the state was described in speech and in writ-

ing as a community of its citizens. The term Rzeczpospolita, meaning

Commonwealth or Republic, was a calque from the Latin res publica, “pub-

lic thing” or “common thing”, and tellingly the Polish-Lithuanian nobility

took a very literal interpretation here, using the term to refer to a certain

polity, and to a certain territorial domain, and to a certain community who

formed that polity and inhabited that domain. “Of what does the republic

consist, if not of us ourselves?” asked Andrzej Zamoyski in the mid-18th

century,5 and this was then a wholly rhetorical question: essentially a

statement of proud fact, already deemed obvious back in the 16th century.

We might say that in the Polish understanding, all the way until the end of

the 18th century, the state was construed in a way more akin to the Roman

civitas than to the French état.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s political system took on its

ultimate shape during what was known as the “great interregnum” (1572–

1576), stretching from the death of Sigismund Augustus to Stephen

Bathory’s ascension to the throne. This period also saw the intensifijication

the

polish

szlachta and their state

9

6 The declaration of the Confederation of Warsaw of 28 January 1573 was included in

UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2003 as an important achievement in the

development of religious tolerance.

of the nobility’s sense of sovereignty, of co-involvement in shaping the

state. It was the fijirst time the Sejm assembly—without any king—made

political decisions and enacted laws. It was then decided that the succes-

sors to the Jagiellonians on the Polish throne would be elected by a general

assembly of the nobility (in what were called viritim elections, held in a

fijield outside of Warsaw) and that the Sejm would convene on a regular

schedule (thenceforth gatherings had to be called every two years for six

weeks); it was then that the possibility of refusing obedience to a king who

violated the laws of the Republic was fijirst allowed for; and it was then, in

1573, that the nobles of various religious confessions who gathered together

in Warsaw pledged

to maintain peace among one another, not to spill blood or punish over dif-

ferent faiths or difffering Churches, and not in any way to assist any authori-

ties or offfijice to perform such deeds. And also, should anyone so desire to

spill blood, exista causa [for this reason] we must all object.6

Amidst a Europe then in the throes of religious warfare, this was evidence

of extraordinary pragmatism and political far-sightedness. On the one

hand such tolerance grew out of class solidarity and concern for the com-

mon liberties, which could come under attack by a king taking advantage

of religious feuding, and on the other it was a manifestation of concern for

preserving religious peace, in a country not just of many confessions but

of many religions and many nationalities. Diversity of languages and faiths

in the Commonwealth was not just the stamp of the nobility: the country

was likewise inhabited by German burgers from Royal Prussia, Ruthenian

and Lithuanian peasants, plus Karaims, Armenians, Scots, Tatars, and

Jews. All three great monotheistic religions, plus diffferent variations

thereof, had followers in the Commonwealth, which was in ethnic and

religious terms the most diverse country in Europe and was aptly likened

to a multi-coloured bird. It had become a single polity only three years

previously, and particularism was still very strong (especially in Royal

Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania). Noble citizens were well aware

that any internal disputes and fijights (especially over issues of religion)

might easily trigger the disintegration of the state. Their representatives

and leaders at the Sejm showed concern not just for the solid legal under-

pinnings of the political system and for safeguarding the noble liberties,

10 chapter

one

7 J. Tazbir, Kultura szlachecka w Polsce, 2nd ed., Warsaw 1979, p. 65

but also for the efffective functioning of state institutions and especially for

guaranteeing the peace and security of the entire Commonwealth.

This duty was made all the more responsible by the fact that no central-

ized administrative apparatus subordinate to the king had emerged. There

was no complex system of state institutions and state offfijicials, akin to

those that increasingly regulated the lives of subjects in the monarchies of

Western Europe, then striving towards absolutism. On the local level the

Commonwealth was governed by local bodies, by municipal authorities in

the cities, and by nobles in the provinces (which meant most of the coun-

try, given the poor network of urban centres). Gatherings of nobles from a

given land, county, or voivodship, known as sejmiki (“little Sejms” or

dietines), dealt with local afffairs as well as issues of state-wide politics.

They were nearly 70 such sejmiki bodies throughout the Commonwealth,

and each nobleman residing within the respective area had a right to take

part in their gatherings. It was the sejmiki that proposed candidates to the

king to be appointed to landed offfijices, that elected judges to the Tribunals

(the highest courts of appeal for the nobility), discussed local economic

matters, and fijinally chose deputies to send to the Sejm, gave them instruc-

tions, and listened to their reports upon their return. The sejmiki convened

several times a year, with highly varied numbers of nobles in attendance:

ranging from just several dozen or a hundred-odd individuals, up to sev-

eral thousand when a matter was of particular importance (for instance

when the election of a new king was approaching). Sessions of the sejmiki

were not always peaceful and the image of quarrelling and wrangling that

foreign observers took away was not entirely unfounded. Still, that does

not change the fact that these provincial assemblies were capable of mak-

ing highly rational political decisions, not only on particularist issues but

on matters afffecting the entire Commonwealth, such as on taxes or foreign

policy. The sejmiki also served as an excellent political training ground:

before each gathering of the Sejm itself, nobles here had a chance to debate

issues of major importance for the country, to learn how to discuss politics,

and hone their ability to hash out agreements on disputed matters.

It is worth stressing that the political culture of the szlachta was indeed

a culture of discussion and debate, consensus and compromise. Discussion

was conducted in the provincial sejmiki, in the Sejm, and also outside of

such assemblies. As the historian Janusz Tazbir has noted, this was the

political culture of a free people,7 and we may add here: of people fully

the

polish

szlachta and their state

11

aware that they were determining matters for themselves and for their

state. Their output of political writings, especially those penned in con-

nection with important events—elections, Sejm gatherings, “confedera-

tions”—nowadays fijills thick volumes. Every political event, every dispute,

every decision could and most often did trigger a flurry of commentaries

in writing, sometimes printed but often copied out by hand and distrib-

uted among the “noble brothers”. We might say that political propaganda

had already made its appearance in the Commonwealth as far back as the

16th century. However, the objective was not just to win others over by the

force of one’s arguments, but also to work out some form of agreement on

disputed issues.

Consensus was the supreme political ideal of the noble citizens—an

ideal that was interpreted quite pragmatically, as working towards a com-

promise acceptable to all participants in the political debate. This notion

of consensus was the underlying principle by which the highest body

within the state, the Sejm, functioned. All of its decisions were made after

prolonged debate, in which votes were not counted but rather “weighed”—

meaning that the value of the arguments presented, the political signifiji-

cance of each speaker, and their intentions were all carefully judged. It is

worth remembering that in the times when Polish parliamentary customs

were crystallizing, the practice of majority voting was still unknown in

Europe. Moreover, in a country with numerous minorities, such majority-

based voting could very simply have ended up leading straight to internal

conflict, to rebellion by those who felt unacceptable decisions were being

forced upon them by a stronger majority, against their will. Through the

practice of ucieranie materii as it was then called in Polish (or “working

matters through”), compromise solutions could be hashed out that would

be acceptable to all or nearly all the Sejm deputies, and moreover to their

noble electors back in their provinces. “Ordinary consensus” was treated

quite loosely, with objections sometimes being ignored if the overwhelm-

ing majority was in favour of adopting a given measure. It was only in the

latter half of the 17th century, when the Commonwealth’s political system

was already in serious crisis, that it began to be treated literally, as entail-

ing that Sejm decisions required full and unanimous acceptance. Through

the principles of consensus and cooperation between the three estates

(one of which was the king), the Sejm was until the mid-17th century not

just a central political body integrating the varied lands of the Republic of

the Two Nations, but also an efffijicient institution co-administering the

afffairs of the state together with the king. The participating nobles had a

deep sense of responsibility, as well as of power and dignity. A telling

12 chapter

one

scene, oft-cited by historians, played out in the Sejm of 1585, when King

Stephen Bathory, furious at an overly bold statement made by one of the

deputies (Mikołaj Kazimierski), cried out at him: Tace nebulo! (Silence,

scamp!). Kazimierski replied: “I am not scamp, only citizen who elects

kings and overthrows tyrants”. Few noblemen in Europe would have dared

to make such a public statement to his monarch, and even fewer could

have managed to get away with it scot-free.

The success of the noble politicians—and also the success of the

Commonwealth itself, as a distinctive system of governance diffferent from

absolute monarchy—may be attested by the fact that over nearly 100 years

of joint noble/royal governance (1560–1648) it enjoyed a time of peace and

security unmatched in other countries. Wars against foreign powers, inso-

far as they occurred, played out in distant peripheries, most often outside

the Commonwealth’s borders, and they were generally victorious wars—

sufffijice it to mention that by 1634 the country’s surface area had swelled to

nearly 1 million km2. Domestically, there was no religiously-motivated

bloodshed, no rebellions or bloody struggles for power. Despite the some-

times harsh disputes, only once did a serious conflict occur, spilling over

the limits of a political struggle and heading towards civil war (the

Sandomierz rokosz, or insurrection, against Sigismund III in 1606), but it

was ultimately defused by peaceful means after a single armed clash.

Amidst war-torn Europe, the Commonwealth was a calm oasis. Krzysztof

Opaliński, observing the destruction wrought by the 30 Years’ War in

neighbouring countries, asserted with satisfaction in 1630 that his country

“like a safe spectator on the shores of the sea, gazes calmly upon the tem-

pest raging before it”.

However, this sense of security, the ability to calmly enjoy one’s own

wealth, the freedom to cultivate one’s own faith, tradition, and customs

were not enjoyed by the nobility alone. The lack of a strong central govern-

ment, intervening in the private lives of individuals, meant that the

Commonwealth’s residents who did not have political rights nevertheless

also enjoyed a certain “space of freedom”. This was especially true for the

citizens of the royal cities. As the political system of the Commonwealth

was crystallizing, its largest towns (Kraków, Wilno, Lublin, Poznań, Toruń,

and Gdańsk) had the right to participate in the Sejm assemblies, but being

too weak to influence the decisions made by those assemblies they did not

exercise that right, striving instead to arrange their matters either by inter-

vening directly with the king or via behind-the-scenes negotiations. Thus

the Sejm ultimately remained a body purely of the nobility. Burghers

the

polish

szlachta and their state

13

generally did not influence state-wide politics, although there were some

exceptions here—such as the powerful town of Gdańsk, which sometimes

dictated its own terms to the king and Sejm. Yet within the bounds of their

own cities, the burghers did have their own sense of citizenship and loy-

alty to the Commonwealth. This is evidenced by the stance the towns

adopted in the event of an external threat—such as the loyalty shown by

Lwów and Gdańsk during the Swedish invasion in the 17th century, or the

resistance put up by the cities of Royal Prussia (Toruń and Gdańsk) to the

Kingdom of Prussia as it seized those lands in the 18th-century partitions,

even despite their linguistic and cultural afffijinities to Prussia.

Other residents of the Commonwealth lands also benefijited from this

space of freedom, enabling them to enjoy liberties of confession and cus-

tom. Among them were certain people who remained somehow outside

the structures of society at that time, such as the Gypsies. This was espe-

cially evident in the case of the Jews, who had their own justice system

within the Commonwealth, their own self-government, and even a kind

of representative assembly (called the Waad), the only such institution of

its kind in Europe. The only group not encompassed was the peasantry—

consisting of serfs increasingly dependent on their noble landowners.

Although the peasants enjoyed quite decent conditions during the eco-

nomic boom of the 16th and early 17th centuries, their predicament clearly

began to worsen during the time of crisis and military destruction in the

latter half of the 17th century, in tandem with mounting feudal burdens

placed upon them and their increasing subjugation to their lords.

Moreover, another point to note is that there were very wide diffferences

between the individual regions of the country, making it very hard to com-

pare relatively wealthy and frequently free peasants from Royal Prussia or

tenant-farmers from the Wielkopolska region to the serfs in the broad

south-eastern expanses.

The system of governance fijirst set forth in the Henrician Articles

evolved in subsequent years towards the further strengthening of the

noble nation. The noble judiciary system had been excluded from

the king’s purview already in the 16th century, with the formation of the

Crown Tribunal (1578) and Lithuanian Tribunal (1581), to which judges

were elected by the provincial sejmiki. The power of the chamber of depu-

ties surged and among other things it began to exert an influence over

foreign policy, which had until then been a royal domain. At least until the

end of the 1640s, the institutions of the mixed monarchy system of gover-

nance worked efffijiciently and the Commonwealth was defijinitely a major

14 chapter

one

political player in its region of Europe, even if not a European power.

Despite that, certain signs of the political system’s future crisis were

already then perceptible.

The system of mixed monarchy was a quite complex and very delicate

construction, functioning well only under specifijic socio-political condi-

tions. Such conditions did exist under the reign of Sigismund Augustus,

when there was cooperation between the king and the gentry (the nobility

of medium wealth). This was then a numerous group within the Crown,

independent, consolidated, and possessed of considerable civic aware-

ness. Moreover, it was in the gentry’s interests to ensure the rule of law and

domestic peace, ipso facto to strengthen the state and the institutions

which guaranteed these things. It proved capable of putting forth a politi-

cal representation that was modern for its times (known as the “Movement

for the Execution of the Laws”), which in agreement with the king enacted

many measures which strengthened the state whilst reining in the exces-

sive influence of the wealthy families. However, this situation changed

when the Jagiellonian line expired, or even previously, after 1569, when

Poland formed a political union with Lithuania. This merger altered the

balance of forces within the noble class, by bringing in the great Lithuanian

and Ukrainian families. Their vast economic power surpassed even that of

the magnates of the Crown, and although they did not immediately

become active in political manoeuvring, they nevertheless clearly shifted

the political balance. At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, the gentry

had not yet lost its signifijicance yet it had already lost its confijidence in

kings, such as it had harboured for the Jagiellonians. The noble/royal alli-

ance, which had been constructive for the country, thus came into ques-

tion. Distrust was already visible in the decisions made in the fijirst

interregnum, which boosted the power of the Sejm at the expense of the

monarchs, and it was then not unjustifijied. The elected monarchs proved

unable to fully exercise the possibilities given to them by the mixed nature

of the Commonwealth’ system of governance. They perceived the institu-

tions that Sigismund Augustus had been able to cooperate with efffijiciently,

above all the noble Sejm, not as mechanisms for exercising their power in

political cooperation with the nobility, but as a rival for power. The kings

from the Vasa dynasty were already more concerned with their own dynas-

tic interests than with strengthening the institutions of the mixed system.

They tried to boost their own power by violating or “circumventing” cer-

tain legal and systemic principles which the nobility viewed as inviolable.

The fijirst serious conflict came under the reign of Sigismund III Vasa. Faced

with a king clearly striving to strengthen his own power at the expense of

the

polish

szlachta and their state

15

the Sejm (including an attempt at imposing fijixed taxes), in 1606 a sizable

portion of the nobility refused to obey him. They bound together as what

was known as a “confederation”.

A confederation (from the Latin confederatio) was a league of nobles

sworn to pursue a certain objective, an institution deeply rooted in the

longstanding political customs of the Commonwealth, although it did not

have solid legal footing. Its sources should perhaps be sought in medieval

gatherings of noble knights, since it represented a kind of direct democ-

racy. Any noble who accepted the stated objective could participate.

A confederation was led by a “generalcy” chosen from among its members.

Confederations were forged in situations deemed to be extraordinary

(such as during each interregnum), when the legally-sanctioned institu-

tions did not function or were widely viewed as insufffijicient, and thus a

group of nobles felt an obligation to take matters into their own hands.

A confederation was intended to defend whatever its participants saw as

being under threat: rights, freedoms, the public order, even the country

itself.

The confederation of 1606 was of a particular sort known as a rokosz,

the term used for a confederation formed in rebellion against the king.

Invoking this form of extraordinary action without clear cause was very

dangerous, as it undermined the legal institutions of governance—not

just the king, against whom a rokosz was targeted, but also the Sejm, since

the confederating nobles opted to resolve their dispute with the ruler in

circumvention of it. While the confederation of 1606, known as the rokosz

of Zebrzydowski (or Zebrzydowski’s rebellion) after its leader, did end in

an agreement reached with Sigismund III and the mixed monarchy sys-

tem did still function decently for another few decades, the events of

1606–1608 nevertheless dealt a serious blow to the Commonwealth’s sys-

tem of governance, and at the same time conclusively buried the possibil-

ity of cooperation between the king and the general nobility. In essence,

this represented a victory for the magnates. Relatively quickly, representa-

tives of the great families began to portray themselves as defenders of the

noble liberties, and at the same time as ordo intermedius—a third force

mediating between the king and the nobility.

The former alliance between the king and the nobility came to be

replaced instead by an alliance between the magnates and the gentry, and

starting in the 1620s/1630s the political signifijicance of the gentry waned

whereas that of the magnates increased. This was partly due to a deteriora-

tion in the economic climate, above all a drop in grain prices which espe-

cially afffected the gentry. It was also the gentry who would bear most of

16 chapter

one

the cost of the wars in the mid-17th century. All of this rendered the gentry

increasingly dependent upon the great families and undercut the former’s

political independence. Its degree of political activity also gradually began

to wane. This was related to a gradual drop in interest in political afffairs

and a lessening sense of responsibility for the state, interpreted as the

common good. We might say that the noble citizen gradually came to be

replaced by the wealthy landowner, interested not so much in participat-

ing in the political life of the country as in protecting his own wealth and

liberties. Polish noble culture had always been a landowning culture; the

idea of leading a virtuous life of moderation in the countryside was already

being held up as an ideal in the 16th century—sufffijice it to mention the

verses of the most illustrious poet of the Polish Renaissance, Jan

Kochanowski. But during the era when the nobility at large was politically

active and the mixed monarchy system enjoyed its greatest successes, this

was chiefly the ideal of a proprietor-citizen always at the ready to serve the

homeland. With time the image shifted instead to that of a meticulous

landowner focused on the afffairs of his own village or villages. The civic

ideals were never fully forgotten, but they distinctly moved into the back-

ground. Already in the times of King Ladislaus (Władysław) IV (1632–1648)

it became evident how political activity was being replaced (then still

gradually) by inertia and a desire to preserve the status quo.

In the domain of political culture, other changes were also taking place.

With the decreasing confijidence in the king and the growing fear of abso-

lutum dominium, the nobility’s stance towards the institutions of the

mixed monarchy began to change. This is evident in the example of the

monarch, who is no longer treated as a political partner, but as a rival to

the Republic. It is also evident in the example of the Sejm. In the times of

King Ladislaus IV and for a signifijicant portion of the reign of John Casimir,

the Sejm still continued to play the role of a central political nexus, where

the sovereign power of the noble nation was exercised, where laws were

enacted, and where all the most important political decisions were made.

However, a conviction began to take root that the basic function of the

Sejm lay not in being politically active, but in defending the existing sys-

tem of governance and the liberty that guaranteed it against the designs of

the king. The Sejm was seen as the main arena in the battle inter maiesta-

tem ac libertatem (between majesty and liberty). Concern for the good of

the Commonwealth changed into concern for the inviolability of its gov-

ernmental principles, the rule of law turned into stifff observance of the

letter of the law. The latter shift is visible in how the principle of full con-

sensus was applied. What had previously been treated quite flexibly,

the

polish

szlachta and their state

17

mainly as entailing equal involvement in political decision-making for all

the lands and districts (via their representatives to the Sejm), now began

to be seen as entailing a requirement that every decision must be accepted

by everyone, down to the very last deputy (the principle of liberum veto). If

we consider that in those times the Sejm did not pass laws individually but

rather treated the various decisions made at a single assembly together, as

a whole (subsequently published as what were called “Sejm constitu-

tions”), a lack of unanimity concerning just one insignifijicant measure

could cause the rejection of all the legislation adopted at a Sejm assembly

and thus entail the complete paralysis of legislative work—and in essence

it soon would mean just that. The objection of a single deputy paralyzed

the Sejm for the fijirst time in 1652, when that deputy objected to the exten-

sion of debate beyond the statutory 6 weeks. This was already a symptom

of a serious crisis of the Commonwealth’s political system, but not yet a

full crisis of the state.

The mid-17th century was a time of severe warfare, starting with inter-

nal conflict against the Cossacks in the south-eastern borderlands (start-

ing in 1648), followed by the Polish-Russian war fought along the

Commonwealth’s entire eastern frontier (1654–1656) and next by the

Swedish “deluge” (1655–1656). For the fijirst time, military engagements cov-

ered the entire territory of the Commonwealth. Faced by the Swedish

onslaught, the decentralized system of local governments worked surpris-

ingly well. With a signifijicant portion of the country occupied by Swedish

forces and with the king in exile, it was the provincial sejmiki that made

and implemented decisions to call up and fund the troops that ultimately

defeated the Swedes. The Commonwealth seemed to emerge victorious

from all this mid-century warfare, but this victory proved illusory—while

it had not sufffered signifijicant territorial losses it did lose its role as a

regional power, and that role would soon be taken up by Russia. The vast

devastation also triggered a long-term economic crisis and caused the gen-

try to completely lose their political signifijicance. Their last attempts at

participating in political life came in the latter half of the reign of King

John Casimir, and their last success was the quite unfortunate election

(contrary to the wishes of the magnates) of his inept successor, Michael

Korybut Wiśniowiecki (1669–1672).

By then, the noble nation already clearly difffered from the one that had

forged the governmental framework of the Republic of the Two Nations.

Above all, the once extraordinarily diverse noble class had become a sig-

nifijicantly more uniform group, becoming almost completely Polonized

and extensively re-Catholicized. The noble nation became increasingly

18 chapter

one

closed offf—both literally so, because it became increasingly difffijicult to

attain noble status, and metaphorically so, since there was a rise in noble

self-satisfaction and mistrust for anything foreign, leading to xenophobia.

The wars fought from the middle of the century onward, in which the

Commonwealth’s external foes were representatives of other confessions

and religions (the Protestant Swedes, Orthodox Russia, and fijinally the

Muslim Turks) bolstered feelings of distrust towards inhabitants of the

Commonwealth who were not of the dominant Catholic faith. Although

all faiths generally did enjoy full freedom (aside from the Polish Bretheren,

who were expelled following the Swedish wars), there was a rising ten-

dency to push the non-Catholic nobility out of political influence, some-

thing that was not conclusively achieved until the 18th century. The noble

class, convinced that they resided in the ideal state, one that guaranteed

the ideals of liberty and mortal happiness, became increasingly closed offf

to foreign influence and models, looking upon other countries with a

sense of superiority and aversion and upon other classes within their own

country with increasing disdain.

At this time, the political system of the Commonwealth was already

functioning very poorly. Aside from objective factors, this was in part

caused by the policies of the last king of the Vasa dynasty, who had consid-

erable opportunities to reform the system with the support of the szlachta,

yet rejected their offfer of cooperation and attempted instead to bolster his

own power, thereby coming into conflict with both the nobility and the

magnate families. This ultimately led to a bloody civil war (1665–1666) and

further undermined the authority of both the monarchy and the Sejm.

Formally speaking, the mixed monarchy system was still the same as

had been created in the 16th century, but in practice its most important

institutions were not functional or functioned poorly. The king, increas-

ingly restrained in his powers, ceased to be a stable political factor guiding

the actions of the state. The Sejm, paralyzed by the principle of mandatory

unanimity, found it increasingly difffijicult to perform its function as the

noble society’s central institution of power—under the reign of Michael

Korybut, only 2 Sejm gatherings out of six arrived at a successful conclu-

sion (meaning the adoption of laws), and under his successor only half

(6 of 12) managed to produce any legislation at all. At the same time, the

Sejm was treated less and less as a body representing a uniform state, more

and more as a gathering of representatives of the individual lands, closely

bound by instructions issued by their respective sejmiki. Given the weak-

ness and inefffectiveness of the system, more and more decisions needed

to be made and were made by the sejmiki, which remained relatively

the

polish

szlachta and their state

19

efffijicient institutions on the local level. This was symptomatic of a broader

problem—in the mid-17th century the Commonwealth experienced a

phenomenon which researchers describe as the decentralization of

sovereignty. The great magnate families emerged still-powerful from the

mid-century warfare, as the destruction wrought by the wars and the con-

sequent economic crisis did not afffect their vast estates to the same degree

as it had the medium-sized noble estates. Their representatives had long

held the highest state offfijices, which kings frequently granted to members

of the same family, even though formally such titles were not hereditary

but granted for life. In view of their economic and political might, the

most powerful of the magnates—the Radziwiłł, Pac, Sapieha, Wiśniowiecki

lines—were essentially virtual sovereign rulers within their own vast

estates. The impoverished nobles were no longer a political partner for

them, as they had been in the fijirst half of the century, but became clients

of one family or another. From the 1680s onward, the magnate courts were

the local centres of political control, and the country was ruled more by

contending factions of powerful magnates than by the king or Sejm. A

ruler who wanted to pursue any comprehensive state-wide policies had

to manoeuvre between such factions. The last monarch able to achieve

success in this regard, perhaps because he was a great magnate himself,

was John III Sobieski (1673–1696). This he spectacularly demonstrated

with his victory at Vienna, a military success and a political success for

both the king and for the Commonwealth—fijielding an army of 83,000 sol-

diers and forging an alliance to defeat the Ottoman Empire, the most men-

acing enemy at that time. Sobieski’s reign was the last period in the history

of the Commonwealth when despite being weak it still remained an active

participant in international politics. Under his successors from the Saxon

dynasty, it would cease to be an active player in its own right, becoming

instead a pawn manipulated by other European powers.

The period from the end of the 17th century until the 1760s was a time

of crisis not only of the governmental system, but of the entire noble state.

It is sometimes described as a period of magnate oligarchy, but this is a

misleading term because it seems to imply that the formal system of gov-

ernance had changed, and that there now existed some central institution

of magnate power. In reality the Commonwealth’s system of governance

formally remained the same as it had been 100 years previously, only its

institutions had completely lost their capacity for political action. The

reigns of the Wettins (1698–1763) brought a complete paralysis of central

institutions, above all the Sejm. Although by law it still convened every

two years, it had become just a kind of shadow-play—over 66 years, only

20 chapter

one

fijive Sejm assemblies concluded in any sort of decision-making at all (and

only one under the reign of Augustus III, 1733–1763), the others ending up

interrupted. In essence, no one had any interest in seeing the Sejm func-

tion well—the king preferred to pursue his own policies without being

checked by the nation, the magnates wanted to be left to govern their own

vast estates, while the szlachta, lamenting the crisis of the Sejm and para-

lyzed by the mythical requirement of full and unanimous consensus and

an obsessive fear of absolutum dominium, were unable to take any steps to

remedy things. The only still-functioning bodies of authority were the

sejmiki, which on a local level also took decisions concerning taxation and

military afffairs. The decentralization of the country continued, and pro-

vincial particularisms intensifijied. While still remaining a mixed monarchy

in formal terms, the Commonwealth was at that time de facto a kind of

federation of magnate-ruled statelets, and at the same time a fijield of com-

petition between rivalling magnate factions, which were strong enough to

hamper the king from ruling and to paralyze the Sejm, yet not sufffijiciently

strong to pursue any autonomous state-wide policies of their own. Besides,

the magnate factions lacked any precise political agendas, and difffered

chiefly in terms of their foreign orientation—variously supporting (and

being supported by) France, the Habsburgs, later Russia, and fijinally

Prussia.

The domestic predicament was further exacerbated by the unfortunate

effforts of King Augustus II, striving to strengthen royal power after the

model of authority he had enjoyed as elector in Saxony, which triggered

great mistrust and fear among the szlachta, who were profoundly attached

to the liberty-based system. Almost from the outset of his reign, this led to

conflict between the noble citizens and the king, and in consequence to a

further weakening in the system of governance. The crisis was deepened

by Augustus II’s decision to embroil the Commonwealth in the highly

destructive Great Northern War (in Poland: 1701–1709). The Commonwealth

became a completely passive, if not to say submissive participant in inter-

national politics, a realm under the multilateral influence of foreign pow-

ers. It did not pursue its own foreign policy; the king generally implemented

the policies of Saxony, the magnates drew upon the assistance of foreign

courts to further their domestic manoeuvring, while the szlachta, con-

vinced of divine Providence, were uninterested in foreign policy and

reluctant towards any attempts at making the Commonwealth more active

internationally, afraid that this could supply grounds for strengthening the

power of the monarchy. A very dangerous situation emerged—a huge

republic, devoid of its own foreign policy and thus of an army, with

the

polish

szlachta and their state

21

inefffijicient state institutions, came to be surrounded by the mightiest

absolute monarchies of the epoch. At least from the 1720s, the surrounding

powers not only meddled in the domestic afffairs of the Commonwealth,

but even determined the shape of its governmental system—the fijirst in a

long series of treaties guaranteeing that the noble republic system would

remain unchanged (including the liberum veto and the free election) was

signed between Russia and Prussia in 1720. Even worse, from the 1720s

onward, interference by foreign powers and its use as a ploy in domestic

political wrangling began to be treated as a fully acceptable element of the

political game.

The fact that not just the political system, but the very sovereignty of

the state was in crisis was clearly confijirmed by the election which fol-

lowed the death of King Augustus II (1733), when the neighbouring pow-

ers, Russia and Austria, took armed action to force the Saxon Elector,

Frederick Augustus II, onto the throne (crowned as King Augustus III of

Poland), even though the szlachta had legally elected Stanisław (Stanislaus)

Leszczyński, an extraordinarily popular magnate from Wielkopolska (the

father-in-law of Louis XV of France). This came as a huge shock for the

noble society, although positive lessons would not be learned from it for

several more decades. The epoch of King Augustus III was a time of great

political stagnation, but it was then that timid discussion began about the

need to reform the political system of the Commonwealth. The degenera-

tion of the system had been criticized previously, the szlachta had already

realized that it was not functioning as well as it had in the times of their

quite mythical “forebears” and lamented the demise of political virtue, yet

no positive agendas for dealing with the crisis had been put forward,

mainly out of the longstanding fear that any change might lead to despo-

tism on the monarch’s part—omnis mutatio periculosa (any change is dan-

gerous) was one of the axioms of Polish political thinking at least from

turn of the 17th and 18th centuries. Starting in the 1740s certain individuals

began to speak out, proposing certain alterations, sometimes extensive

ones, to the existing organization of the system of governance. They were

put forward by the authors of political writings—in A Free Voice Ensuring

Freedom, a work ascribed to Stanisław Leszczyński, in the publications of

Stanisław Poniatowski and Stefan Garczyński, and in Stanisław Konarski’s

On the Means of Efffective Council (1761–1763), fijiercely attacking the liberum

veto. The need for reform was also perceived by the leaders of the two

main magnate factions at that time, the Czartoryskis (simply known as

“the family”) and the Potockis. However, in political practice they remained

focused on their own short-term, particular interests and no attempt at

22 chapter

one

overcoming the political paralysis was made down to the end of Augustus

III’s reign.

Such attempts would not be made until after his death, under very

inauspicious political conditions, when the Commonwealth was already

de facto a Russian protectorate. The effforts made by King Stanisław August

(Stanislaus Augustus) Poniatowski (1764–1795) to curb the liberum veto

principle and to streamline the organization of the central institutions to

some extent were initially received very badly by a signifijicant portion of

the szlachta, as an endeavour striving towards absolutum dominium. This

mood of discontent was taken advantage of by the magnates on the one

hand, anxious to preserve their own influence, and by Russia on the other,

not eager to see any reforms that might strengthen the Commonwealth.

This triggered the Commonwealth’s last noble “confederation” formed

against the king, known as the Confederation of Bar. The resulting bloody

civil war, which at the same time was a war against an external enemy

because Russian troops played a large role, lasted four years (1768–1772)

and ended in the First Partition of the Commonwealth and its complete

subjugation to Russia. These dramatic events triggered a revival in politi-

cal interest among the gentry. This group had again begun to gain in

importance, as the economic situation began to improve from the middle

of the century onwards. At the same time, it had borne the main costs of

the events of 1768–1772, a fact that severely undermined its trust in the

magnate leaders. The gentry also began to realize that the real threat to

their freedoms was posed not by Poniatowski the alleged tyrant, but by a

loss of sovereignty and by foreign meddling in domestic state afffairs. This

group did not become politically active immediately, and it took even lon-

ger for it to fully grasp the need for change. Besides, under Russia’s protec-

torate the possibility for any sort of political action was highly limited, and

governmental reforms were completely impossible. They only became

attemptable in 1788–1792, when the longest Sejm ever held in the Republic

of the Two Nations, known as the Four-Year Sejm, convened under an aus-

picious international situation. The king undoubtedly played a huge role

in this assembly, probably as the only participant who had an overall con-

cept for state reform that had been worked out long in advance. The mag-

nate leaders were quite signifijicant, especially Ignacy Potocki, but there

was also a large group of gentry representatives present, independent and

taking on ever-greater political signifijicance. There was extraordinarily

lively political discussion not only in the Sejm itself, but also outside it—

the period saw a true outpouring of political writings. Burghers also joined

in, demanding full civil rights and an influence over political decisions.

the

polish

szlachta and their state

23

Ultimately, after three years of discussion and disputes, on 3 May 1791,

what was called a “Government Act” was adopted—the fijirst modern con-

stitution in Europe, and the second in the world. Later known as the

Constitution of the Third of May, it was drafted based on foreign mod-

els (especially the English model) and modern political theories

(Montesquieu, Rousseau), but also based on the Polish political tradi-

tion. In 11 short articles, it laid the foundation for a political system that

turned the anachronistic and long-inefffijicient system of mixed monar-

chy into a modern parliamentary monarchy, with a sovereign nation, a

hereditary monarch (upon Stanisław August’s death this was meant to be

Elector Frederick Augustus III of Saxony and then his descendants), a

separation and balance of powers, and a regularly convening parliamen-

tary assembly. As an aside, it is worth noting that modernization was

in fact a relatively easy task despite the decentralization of the Common-

wealth, since it was a country quite uniform in legal and administrative

terms, there were no local privileges, and no new uniform structure of

power needed to be forged for the entire country. Rather, the functioning

of the existing Sejm, sejmiki, and courts merely needed to be stream-

lined—and this is precisely what the Constitution of the Third of May

achieved. Signifijicantly, it likewise precipitated processes of social change:

although political power remained vested in the szlachta, by giving the

burghers full civil rights and limited political rights and by placing the

peasants under the protection of the Republic, a fijirst step was taken

towards eliminating the class-based society, replacing the noble nation

with a nation of all Poles. By Polish standards, these changes were revolu-

tionary and were recognized as such by European opinion, which indeed

described them as “the Polish revolution”. Although initially not imple-

mented too formally, the reforms were accepted by a majority of noble

society in the sejmiki gatherings of February 1792, which constituted a kind

of referendum.

The Commonwealth thus joined in the general European process of

modernization, ceasing to be the nation of just a single class, a nation of

the nobility. But unfortunately, the noble and bourgeois citizens would

never have the opportunity to follow through with such reforms. The

international situation again took a turn for the worse, leading to a Russian

invasion (1792) dealing a defeat to the still weak troops of the

Commonwealth. The Second Partition ensued, and then after the short

interlude of the Kościuszko Uprising, which saw the nobility fijighting

alongside the bourgeoisie for freedom, the Third Partition quite simply

wiped the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth offf the map of Europe.

24 chapter

one

The state which the nobility had formed back in the 16th century thus

met its demise at the very moment when it was ceasing to be just a “noble”

state, just when it was managing to overcome its long-standing crisis, just

when anarchy was being lifted and governmental and social reforms were

achieving great success. This fact is worth stressing, since contrary to what

the partitioning powers maintained the partitions were not in fact caused

by the weakness and anarchy of the Commonwealth—although such fac-

tors defijinitely made the partitions easier to carry out.

1 “Uwagi względem Konstytucyi dnia 3 maja zapadłej”, Pamiętnik Historyczno-Polityczny,

June 1791.

2 This ecstatic statement was penned by a defender of the old freedom during the Four-

Year Sejm: Uwagi przeciw elekcyi i sukcesyi tronu w Polszcze, n.p. 1791, p. 9.

3 [F. S. Jezierski], O bezkrólewiach w Polszcze i wybieraniu królów[…], Warsaw 1790, p. 54.

CHAPTER TWO

GOLDEN LIBERTY—A NOBLE PRIVILEGE OR UNIVERSAL IDEA?

“Let us begin with what Poles are concerned with most—freedom”, Piotr

Świtkowski wrote in 1791,1 and his words reflected well the views of his

own time as well as those that had prevailed 100 and 200 years previously.

Starting already in the 16th century, the concept of freedom, love for free-

dom, concern for preserving freedom, and a constant fear of losing free-

dom were permanent elements not just of political discussion, but nearly

every public statement made in the Republic of the Two Nations. Freedom

was perhaps the most frequently appearing catchword in political trea-

tises and propaganda pamphlets, in addresses to the Sejm, sejmiki, and

courts, in sermons and laudations, where it featured as the supreme value,

the most cherished treasure of the Poles. How precious a commodity free-

dom was seen as is indicated by the numerous epithets heaped upon it:

liberty was not just described as “golden”, it was held up as the most prized

and beautiful gemstone, as a treasure, as the “honour of the world”, as the

most precious gift bequeathed by heaven or by nature (depending on the

context and the views of the author), as a “refijined gift, a magnifijicent gift,

so magnifijicent that the human mind is unable to fathom it”.2 It was sacred,

inestimable, sweet. This last adjective was perhaps the most popular: the

slogan libertas patriae dulcissima rerum, taken from the Romans, was

repeated in the Commonwealth from the 16th century onward. The sweet

taste of freedom was appreciated even by 18th-century critics of unbridled

anarchy. Franciszek Salezy Jezierski—by no means a Sarmatian noble-

man, but rather a leading Polish reformer of the late 18th century—felt

that liberty was “a gift from Heaven to sweeten the unpleasant life of mor-

tals on Earth”.3 It seems uncontroversial to conclude that freedom was in

the Polish writings and speeches not just a precious commodity, but

indeed the most precious one of all, verging upon the sacrum. This is con-

fijirmed by the turn of phrase “faith and freedom” that was popular in the

26 chapter

two

4 Krótkie rzeczy potrzebnych z strony wolności a swobód polskich zebranie, przez tego,

który wszego dobrego życzy ojczyźnie swojej roku 1587, 12 februarii, ed. K. J. Turowski, Kraków

1859, p. 13.

5 J. Zamoyski, Votum … na sejmie warszawskim, już ostatnim za jego żywota, w r. 1605. In:

Pisma polityczne z czasów rokoszu Zebrzydowskiego 1606–1608, ed. J. Czubek, vol. 2: Kraków

1918, p. 94.

6 Naprawa Rzeczypospolitej do elekcyi nowego króla (1573), ed. K. J. Turowski, Kraków

1859, p. 4.

7 Wolność polska rozmową Polaka z Francuzem roztrząśniona, ed. T. Wierzbowski,

Biblioteka zapomnianych poetów i prozaików polskich XVI - XVIII w., vol. 21, Warsaw

1904, p. 7.

17th and especially 18th centuries, equating liberty with the supreme spiri-

tual value. Without freedom, all other values were worthless. Without

freedom, one could not enjoy wealth, success, or even family life. This had

been stressed very heavily by the Renaissance authors at the very dawn of

the Republic of the Two Nations: “Without this gem, all other values be

next to nothing” wrote the author of one pamphlet dating to 1587.4 The

Polish nobility considered themselves to be the possessors of this treasure

starting in the 16th century. Fundamentum nostrae reipublicae libertas est

said Jan Zamoyski in 1605,5 but the conviction he voiced had been around

earlier. It was expressed even prior to the creation of the Republic of the

Two Nations, under the reign of the last Jagiellonian ruler. This conviction

was a source of pride, or even hubris—especially since it was accompa-

nied by a belief that the Polish freedom was something extraordinary and

unparalleled, that no one enjoyed such liberty as the Poles did. This Polish

freedom was viewed not only as the most precious jewel, but as the only

such jewel anywhere in Europe, if not the world. As early as in 1573, an

anonymous author wrote with pride: “No nation in the world hath greater

freedoms and liberties than we”.6 For 200 years, it was reiterated that “there

is no nation under the sun as free as Poland”.7