D E C E M B E R

2 0 0 5

33

W

hen, in 1784, Haydn was

approached with a commission

to write a group of symphonies

for a concert series in Paris, he was frankly

astonished. He had signed on with the

Esterházy princes in Austria and Hungary

in 1761, and in his first two decades in

their service he was perpetually occupied

in composing new works for his musi-

cians’ use and his prince’s delectation. As

Haydn later recalled of these years, in an

interview with his biographer Georg

August Griesinger:

My sovereign was satisfied with all my

endeavors. I was assured of applause

and, as head of an orchestra, was able

to experiment, to find out what

enhances and detracts from effect, in

other words, to improve, add, delete,

and try out. As I was shut off from the

world, no one in my surroundings

would vex and confuse me, and so I

was destined for originality.

However, Haydn was considerably less

“shut off from the world” than he may

have thought, and in the quarter century

in which he had been the court musical

director (Kapellmeister) for the Esterházys

he had gradually grown famous in the

world outside and his music had attracted

an enthusiastic following throughout

Europe. Of course, in the days before

international copyright protection the

composer would not necessarily have

known just how popular he was becom-

ing: publishers could disseminate his

Born

almost certainly on March 31, 1732 —

he was baptized on April 1 — in Rohrau,

Lower Austria

Died

May 31, 1809, in Vienna

Works composed and premiered

The Symphony No. 83 was composed in

1785, the Symphony No. 86, in 1786.

Both works were premiered in 1787

(the exact dates are elusive) at Paris’s

Concerts de la Loge Olympique, directed

by Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de

Saint-Georges.

New York Philharmonic premieres and

most recent performances

Symphony No. 83: premiered March 29,

1962, Leonard Bernstein, conductor;

last performed February 9, 1988,

Charles Dutoit, conductor

Symphony No. 86: premiered March 29,

1925, Bruno Walter conducting the New

York Symphony (which merged with the

New York Philharmonic in 1928 to form

today’s New York Philharmonic); last

performed March 3, 1997, Neeme Järvi,

conductor

Estimated durations

Symphony No. 83: ca. 23 minutes

Symphony No. 86: ca. 24 minutes

Notes on the Program

BY JAMES M. KELLER, NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PROGRAM ANNOTATOR

Symphony No. 83 in G minor/major, “La Poule” (“The Hen”),

Hob. I:83

Symphony No. 86 in D major, Hob. I:86

JOSEPH HAYDN

this is same size as always

12-14 Zacharias 12/2/05 5:29 PM Page 3

pieces at will, without providing him with

any income from the sale of his scores.

The Parisians had taken a shine to

Haydn’s music as early as 1764, when some

of his symphonies and string quartets

appeared in print there. One publisher in

Paris, Jean Georges Siéber, began issuing

works by Haydn in the 1770s, and would

eventually print 53 of his symphonies;

other French publishers did their best to

keep up, and leading Parisian musical

groups (including the prestigious Concert

des Amateurs and the Concerts Spirituels)

offered his works almost incessantly.

In the 1780s a new organization

joined the Parisian musical scene, the

Concerts de la Loge Olympique. This

was a performing arts outgrowth of a

prominent and liberal Masonic lodge; it

held its performances in the guard room

34

N E W Y O R K P H I L H A R M O N I C

The Key of the Symphony No. 83

Haydn’s Symphony No. 83 is sometimes

identified as being in G minor, sometimes

in G major. Both are right, yet neither is. It

is not unusual for a piece in the minor

mode to conclude with a major-key finale;

however in such cases the minor mode is

normally reinforced a good deal before that

conclusion is reached. Here Haydn entirely

sacrifices the minor as the engine of his

music after the first movement; the second

movement is in E-flat major, the third is in

G major (even in its trio section), and its

Finale is in good-humored G major. We

therefore list this symphony as being in

G minor/major, which reflects the minor-

mode bluster of its opening while suggest-

ing that, in the long run, the major mode

governs this symphony fully as much.

Listen for …

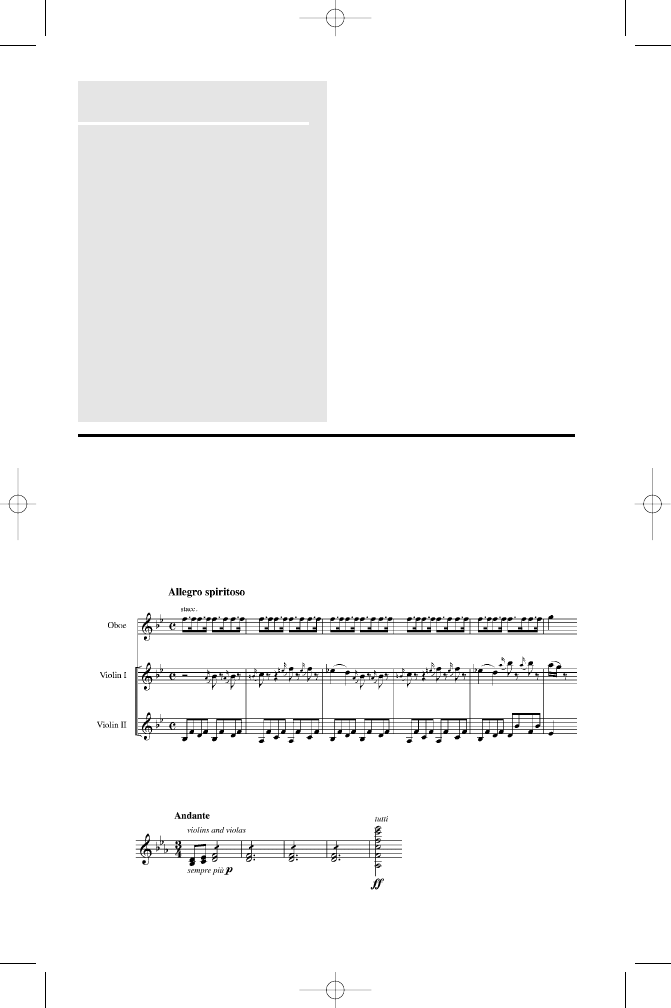

French audiences began attaching the nickname “La Poule” (“The Hen”) to Haydn’s Sym-

phony No. 83 early on. The nickname is generally accepted to refer to a passage in the first

movement where the solo oboe clucks away, staccato, in a dotted rhythm on a single note (F)

for five measures without interruption. However, it could as easily refer to the violin parts that

precede that passage and then accompany it, a halting melody with quirky grace notes in the

first violins, a staccato Alberti bass in the seconds:

Other hints of poultry can be found elsewhere in the piece as well, as in an odd passage of

unaccompanied repeated eighth notes played by middle strings in the slow movement —

terminating in what is perhaps the very loud crow of a rooster:

12-14 Zacharias 12/2/05 5:29 PM Page 4

D E C E M B E R

2 0 0 5

35

of the Tuileries palace. One of the

group’s backers — the marvelously

named Claude-François-Marie Rigoley,

Comte d’Ogny, who was just then inher-

iting the heady state office of Général

des Postes — seems to have been the

direct instigator of the Haydn commis-

sion, though the actual contracting was

left to the group’s musical director, the

famous mulatto violinist Joseph

Boulogne Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

Haydn — who, in all his 51 years, had not

expected that his compositions would

secure him more than a relatively humble

existence — could only marvel at the sum

the Parisians proposed: 25 louis d’or for

each of the six symphonies, plus another

five for the right to publish them. That

was five times what the group normally

paid for such work; in today’s currency, 25

louis d’or would translate to something in

the neighborhood of $60,000.

Haydn’s six “Paris” symphonies (Nos. 82–

87) show off a range of character. Several —

specifically those with nicknames — have

become standard orchestral repertoire:

No. 82, “L’Ours” (“The Bear”); No. 83,

“La Poule” (“The Hen”); No. 85, “La

Reine” (“The Queen,” so called because it

was the favorite of Marie Antoinette). Of

those without handy monikers, No. 86

enjoys nearly as much currency on the con-

cert circuit. For no good reason, No. 84

remains rather the odd symphony out,

almost entirely ignored by programmers;

No. 87 is nearly as neglected.

All six were eagerly applauded —

repeatedly — by the Parisians who first

heard them. They were taken up not only

by the Orchestre de la Loge Olympique,

What’s in a Name?

The

Capriccio: Largo of the Symphony No. 86 is curiously titled. One would not expect to find

these terms arm in arm, since capriccios — suggestive of nonchalance and whimsy — seem

generally disposed to quick tempos rather than to such a

super-slow one as Largo.

However, this marking does seem just right for

the peculiar personality of this movement, which

is grave yet fantastical, prone to modulate in all

sorts of unexpected directions, its discrete

sections divided by sometimes violent

ruptures, not too distant in spirit from the

emotionally fraught, ever-questing slow move-

ments of C.P.E. Bach. One imagines Haydn

seated at his piano, deep in thought,

improvising — which is how he said he

customarily got started on a composition.

Here the trumpets and timpani, which add a

festive air to the other movements, are silent

while the strings and woodwinds weave a spell

of deepest intimacy.

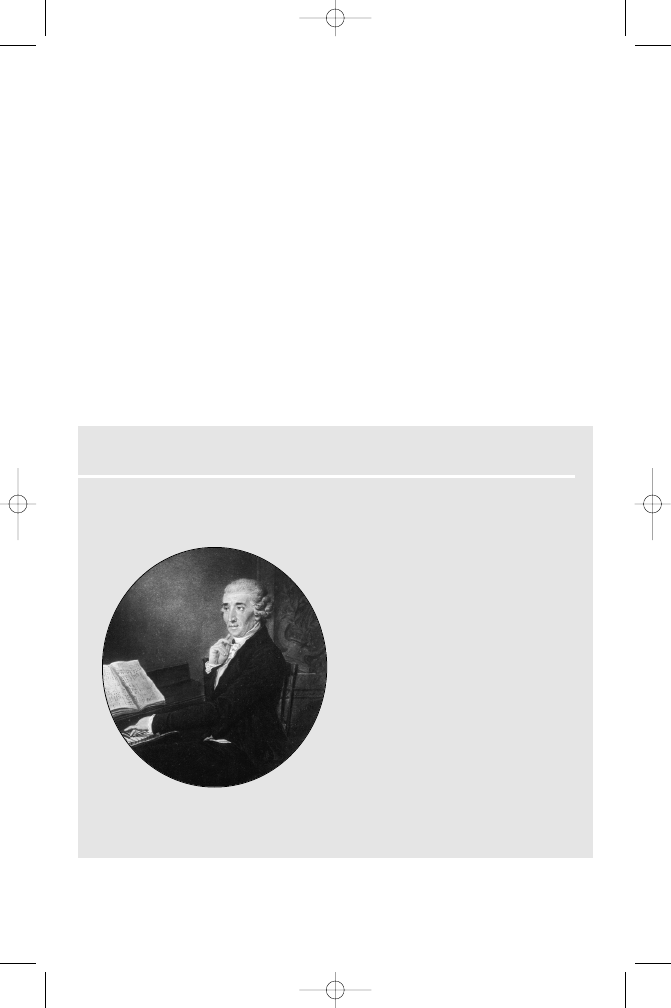

Johann Zitterer's portrait of Haydn (1795)

12-14 Zacharias 12/2/05 5:29 PM Page 5

36

N E W Y O R K P H I L H A R M O N I C

but also by other orchestras in town.

Commenting on the 1787 season of the

Concerts Spirituels, the Mercure de

France reported:

Symphonies by Monsieur Haydn were

performed at every concert. Each hear-

ing increases our appreciation and

admiration of the works of the great

genius, who, in all his pieces, under-

stands so well how to draw the richest

and most varied developments from

every theme. In this he is the complete

antithesis of those sterile composers

who switch constantly from one idea to

another because they do not know how

to present it in a variety of forms and

who mechanically place one effect next

to another, without any sense of cohe-

sion and taste.

Instrumentation:

both works are scored

for one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two

horns, and strings; to this the Symphony

No. 86 adds two trumpets and timpani.

On the Grand Scale

The income provided by the commission for the “Paris” Symphonies surely pleased Haydn, but

he must also have been thrilled at the prospect of writing for a large cosmopolitan orchestra.

At the Esterházy court he could depend on an ensemble of about 24 instrumentalists — the

exact number fluctuated a bit over the years — which was a good-sized orchestra at that time.

Nevertheless, the Orchestre de la Loge Olympique was enormous in comparison, boasting a

string section with fully 40 violins on top and 10 double basses on the bottom, not to mention

two players for each of the usual wind instruments (though normally only one flute). This

represented a luxury for a composer accustomed to doling out his parts with consideration to

which players could double on which instruments.

In the event, Haydn could only imagine these expanded sounds as he composed the six

works in 1785–86, in Eisenstadt and Esterháza. Further, he never heard the Orchestre de la

Loge Olympique play his symphonies, and he was therefore deprived of the further spectacle of

seeing the members of that ensemble decked out in their full concert regalia, each wearing a

sky-blue uniform with a sword at his side.

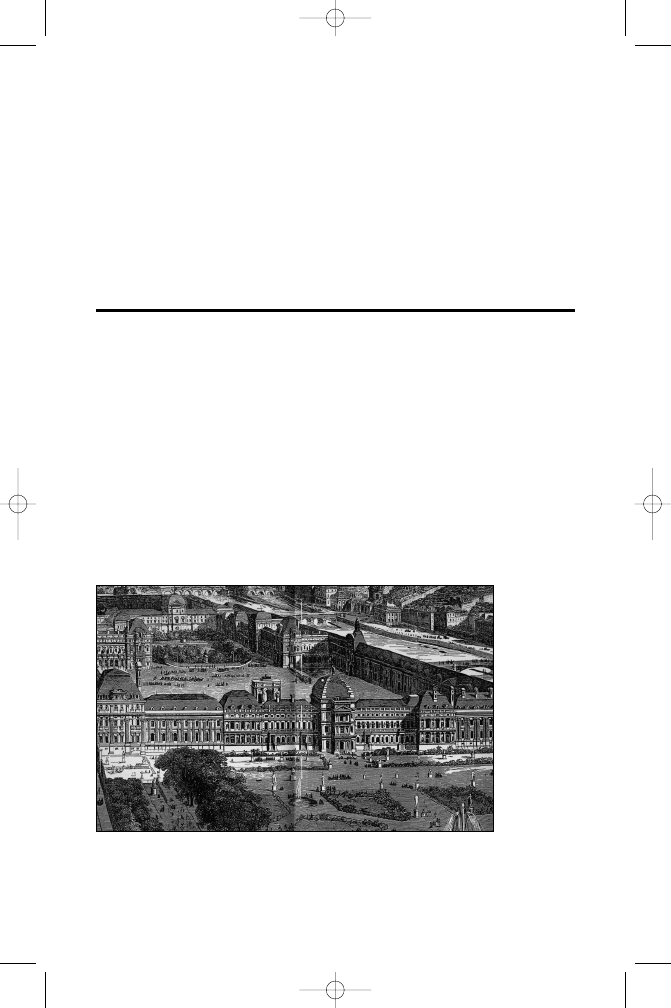

An early

19th-century

engraving of

the Palais

des Tuileries,

where these

works were

premiered

12-14 Zacharias 12/2/05 5:29 PM Page 6

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Haydn Symphony No 98 Winkler

Haydn Symphony No 93 Winkler

Haydn Symphony No 100 double bass ed Bentgen

Haydn Symphony No 99 (2h, Winkler)

Haydn Winkler Symphony No 85 La Reine

Haydn Winkler Symphony No 94 The Surprise(1)

Haydn Symphonie Nr 6 Le matin Violoncello

103 7 Symfonia Sibeliusa Jay Friedman Sibelius Symphony no 7, Oct 1, 2003 ,

Nowowiejski Organ Symphony No 8, Op 45 No,8

Haydn Symphonie Nr 6 Le matin Fagotto

Beethovens symphony no 5

Haydn Symphonie Nr 6 Le matin Oboe 1 2

Haydn Symphonie Nr 6 Le matin Contrabbasso

Mahler Symphony No 5 IV

Beethoven Symphony No 5 Mov 3

Górecki, Henryk Mikołaj Polish Music Journal 6 2 03 Gorecki s Remarks on Performing His Symphony No

Mahler Symphony No 2 IV Urlicht orch score

Beethoven Symphony No 5

Brahms Symphony No 4 Mov 2

więcej podobnych podstron