Cultural Look 1

5/25/02

Perceiving an Object and its Context in Different Cultures:

A Cultural Look at New Look

Shinobu Kitayama

Kyoto University

Sean Duffy

University of Chicago

Tadashi Kawamura

Kyoto University

and

Jeff T. Larsen

Princeton University

3980 words

Running head: Cultural Look

We thank members of the cultural psychology labs at both Kyoto University and the

University of Chicago for comments on an earlier draft. Address correspondence to

Shinobu Kitayama, Faculty of Integrated Human Studies, Kyoto University. Yoshida,

Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501 Japan. E-mail may be sent to kitayama@hi.h.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Cultural Look 2

Abstract

In 2 studies, a newly devised test (Framed Line Test) was used to examine the hypothesis

that individuals engaging in Asian cultures are more capable of incorporating, but those

engaging in North American cultures are more capable of ignoring, contextual

information. Participants were presented with a square frame of varying size, within

which was printed a vertical line of varying length. Participants were then shown

another square frame of the same or different size and asked to draw a line that was

identical to the first line in terms of either absolute length (absolute task) or proportion to

the height of the pertinent frames (relative task). In support of the hypothesis, whereas

Japanese were more accurate in the relative task, Americans were more accurate in the

absolute task. Moreover, when engaging in another culture, individuals showed a

cognitive characteristic that resembled the one common in the host culture. (148 words)

Cultural Look 3

Perceiving an Object and its Context in Different Cultures:

A Cultural Look at New Look

Although perception depends on sensory input, it also involves a variety of

“top-down” processes that are automatically recruited to actively construct a conscious

percept from the input. According to this thesis, called New Look in the 1950s, percepts

are significantly modified by expectation, value, emotion, need, and other factors that are

“endogenous” to the perceiver (Bruner, 1957; Bruner & Goodman, 1947;). “Exogenous”

factors, such as physical properties of the impinging stimulus, cannot account, in full, for

the emerging percept. Although initial demonstrations evoked a considerable controversy

and skepticism (e.g., Postman, Bronson, & Gropper, 1953), the basic idea has proved quite

viable (Erdelyi, 1974; Niedenthal & Kitayama, 1994; Zajonc, 1980), and has since taken a

strong hold in the mainstream of cognitive and social psychology (Higgins & Bargh,

1987).

For a large part, however, this literature has so far ignored culture. This

omission is both surprising and unfortunate. As a pool of ideational resources (e.g., lay

theories, images, scripts, and worldviews) that are embodied in public narratives,

practices and institutions of given geographic regions, historical periods, and groups,

whether ethnic, religious, or otherwise (Kitayama, 2002), culture may be expected to be

one, perhaps the most fundamental source of each person’s values, expectations, and

needs. The purpose of the current work, then, was to take a renewed look at the New

Look from a cultural point of view.

Culture and Cognition

An important lead on this point has already been made by a number of recent

studies that focus on cultural variation in cognitive processes, which as a whole suggest

that different cultures foster and encourage quite different modes of cognitive processing

Cultural Look 4

(Kitayama, 2000; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001).

In particular, people engaging in North American cultures (North Americans, in short)

are assumed to be relatively more attuned to a focal object and hence to be less sensitive

to context. North Americans are thus described as analytic (Nisbett et al., 2001) or

field-independent (Witkin & Berry, 1975) in cognitive style. Conversely, those engaging in

Asian cultures (Asians, in short) are hypothesized to be attuned more to contextual

information—namely, information that surrounds the focal object. Asians are thus

described as holistic or field-dependent in cognitive style. These culturally divergent

cognitive characteristics have been examined with several different measures such as

attitude attribution (e.g., Masuda & Kitayama, 2002; Miyamoto & Kitayama, in press),

performance in a rod and frame task (Ji, Peng, & Nisbett, 2000; Witkin & Berry, 1975), a

Stroop interference effect (Kitayama & Ishii, 2002; Ishii, Reyes, & Kitayama, in press),

and context-dependent memory (Masuda & Nisbett, 2001). A reasonable conjecture from

this emerging literature is that the cross-culturally divergent modes of cognitive

processing must be differentially advantageous, depending on the demands of a

particular task.

Specifically, some tasks require ignoring contextual information when making a

judgment about a focal object. For example, a judgment about another person may often

be tainted by wrong stereotypes associated with a group of which she is a member. In

these circumstances, it is necessary to discount any such stereotypes. Such tasks may be

called absolute tasks in that the focal judgment must be made in terms that are

uninfluenced or unchanged by any contextual information. In these tasks, performance

should be better for North Americans than for Asians. Using a rod and frame test (RFT;

Witkin & Berry, 1975), Ji and colleagues (2000) have recently provided evidence for this

prediction. Participants were presented with a tilted frame in which a rotating line was

placed at the center. The participants’ task was to rotate the line so that it was orthogonal

Cultural Look 5

to the earth surface (or it was aligned to the direction of gravity) while ignoring the frame.

Ji et al. (2000) found that Americans were more accurate in line alignment (hence

indicating their superior ability to ignore contextual information) than Chinese. This

evidence is noteworthy because the RFT has no obvious social elements.

In contrast, some other tasks require incorporating contextual information. For

example, a judgment about another person often benefits from attention duly given to the

specific social situation in which she behaves. These tasks may be called relative tasks in

that the focal judgment must be made in terms that change in accordance with the nature

of relevant context. We may expect that Asians with contextual sensitivity would have an

advantage. Unlike the evidence for the absolute task, evidence for this prediction comes

exclusively from social domains. Thus, it is well known that North Americans often fail to

give proper weight to significant contextual information in drawing a judgment about a

focal person. This bias, called the fundamental attribution error, is typically substantially

weaker in Asian cultures (e.g., Miyamoto & Kitayama, in press; Morris & Peng, 1994).

Present Research

The available evidence indicates that there is substantial cognitive difference

across cultures (Nisbett et al., 2001). Furthermore, this difference can be demonstrated

with tasks that are both obviously social (e.g., Miyamoto & Kitayama, in press) and those

that are minimally social (e.g., Ji et al., 2000). Nevertheless, there still exist some

significant limitations that have hampered the further development of theory on cultural

variation in cognitive competences.

First, with an important exception of Ji et al. (2000), virtually no existent studies

evaluate performance against any objective criterion. This makes it difficult to draw any

conclusions on the normative status of cognitive biases that are suggested in the

literature. Second, in all existent studies that examine relative tasks (e.g., attitude

attribution), participants are never instructed to use contextual information and,

Cultural Look 6

therefore, it is uncertain whether the cross-cultural difference was due to Asians’ greater

propensity to attend to the context, their greater competence to incorporate information

in the context, or both. Third, though Ji and colleagues’ (2000) RFT findings suggest that

North Americans’ greater ability to ignore context extends from social to nonsocial tasks,

it is not clear whether Asians’ greater ability to incorporate context extends to nonsocial

tasks. Fourth and, perhaps, most important, in all the existent studies, very different

domains such as line alignment and social perception are used in defining the two

theoretical types of tasks. This makes it impossible to draw any meaningful comparison

between performance in an absolute task and performance in a relative task.

In an effort to address these limitations inherent in the current evidence, we

developed a new test called the framed line test (FLT). The FLT is specifically designed to

assess both the ability to incorporate and the ability to ignore contextual information

within a single domain that is arguably nonsocial. Further, within the FLT, this

assessment can be made in reference to an objective standard of performance. Specifically,

participants are presented with a square frame of varying size, within which is printed a

vertical line of varying length. The participants are then shown another square frame of

the same or different size and asked to draw a line that is identical to the first line in

terms of either absolute length (absolute task) or proportion to the height of the pertinent

squares (relative task).

In the absolute task, the participants have to ignore both the first frame (when

assessing the length of the line) and the second frame (when reproducing the line). Hence,

the performance in this task should be better for North Americans than for Asians. In the

relative task, the participants have to incorporate the height information of the

surrounding frame in both encoding and reproducing the line. Hence, the performance in

this task should be better for Asians than for North Americans. Moreover, one major

advantage of the FLT is to allow an assessment of the relative ease or difficulty of the two

Cultural Look 7

tasks. It was predicted that whereas for Asians, accuracy should be higher for the relative

task than for the absolute task, for North Americans the reverse should be the case.

STUDY 1. FLT IN JAPAN AND THE US

Method

Participants

Twenty undergraduates at Kyoto University, Japan (8 males and 12 females),

and 20 undergraduates at the University of Chicago, the US(9 males and 11 females),

volunteered to participate in the study. All Japanese undergraduates were native

Japanese and all American undergraduates were of European decent.

Materials and Procedure

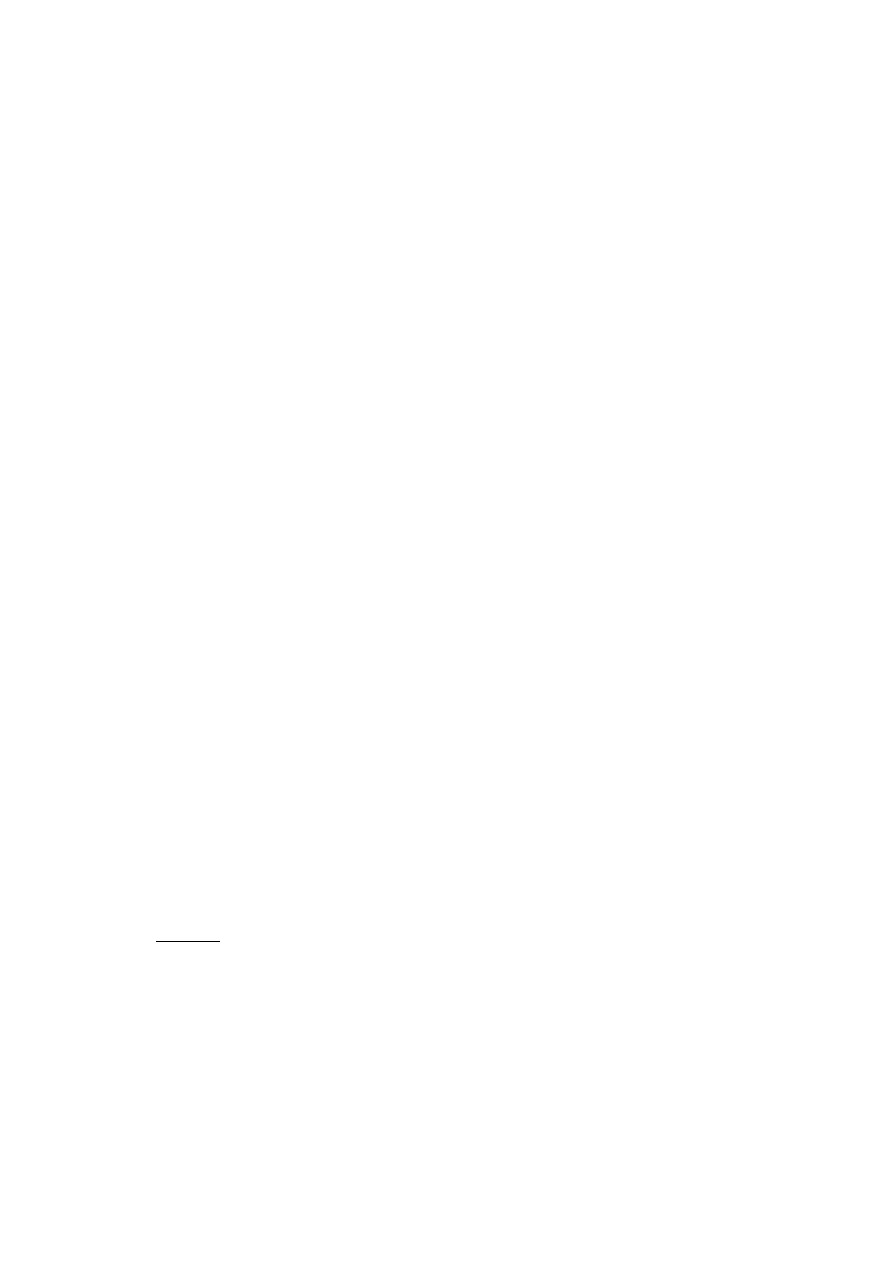

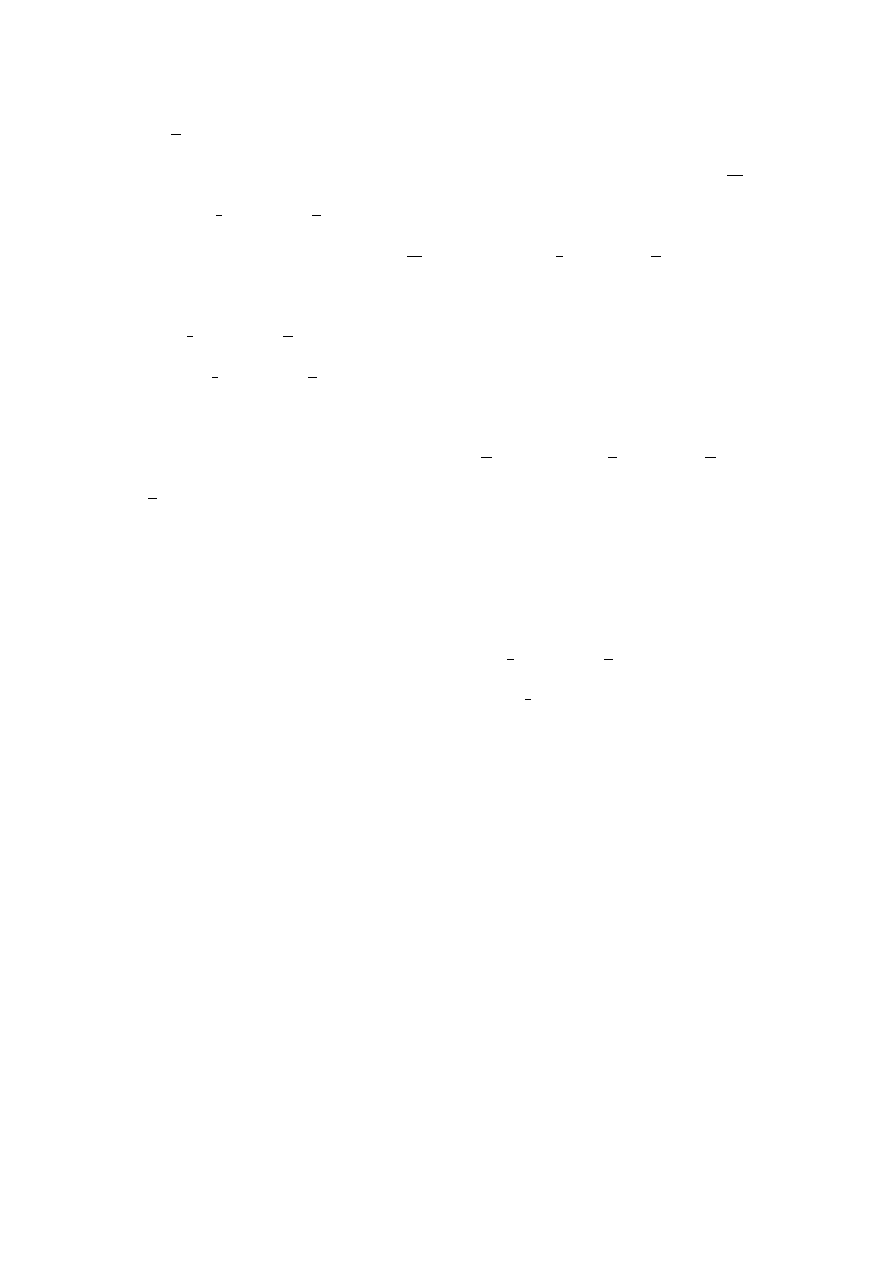

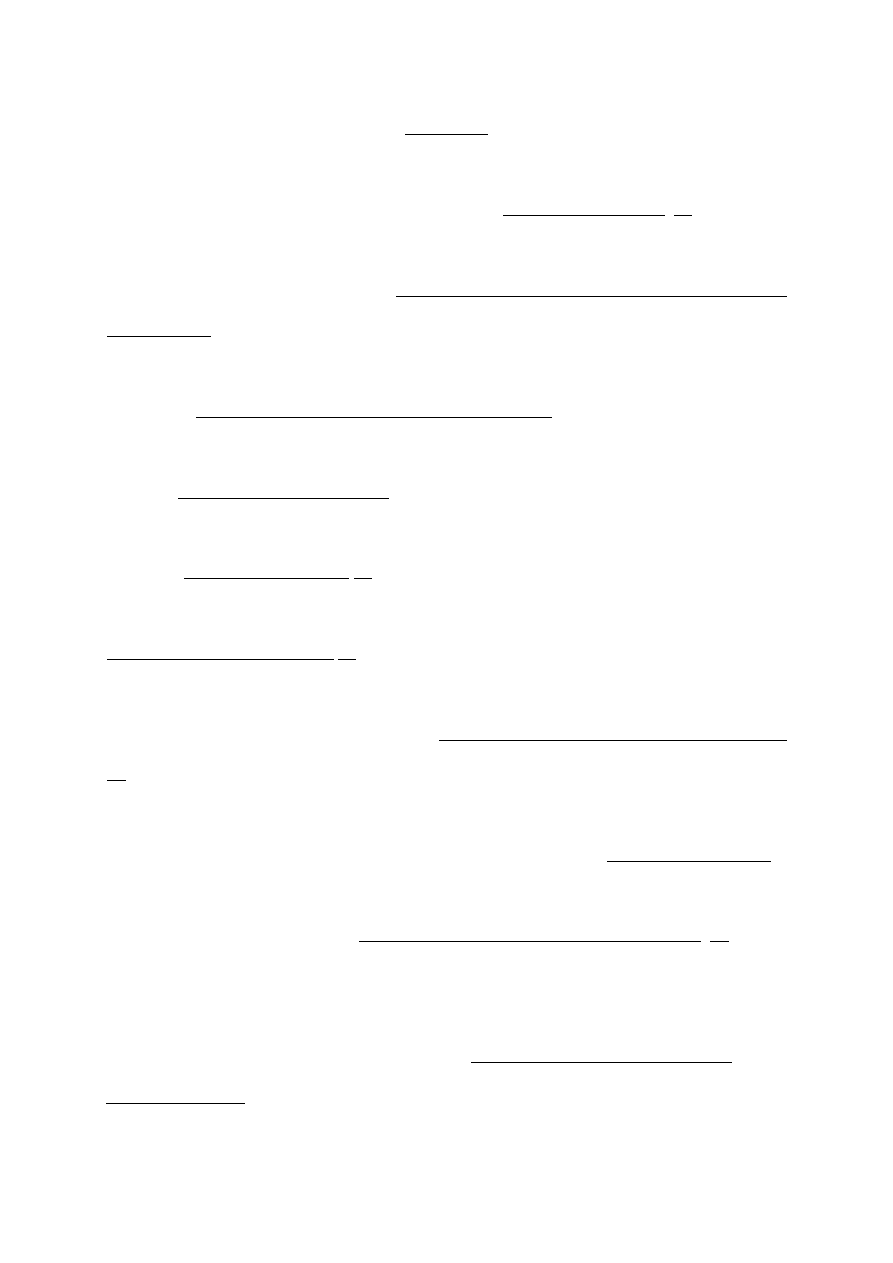

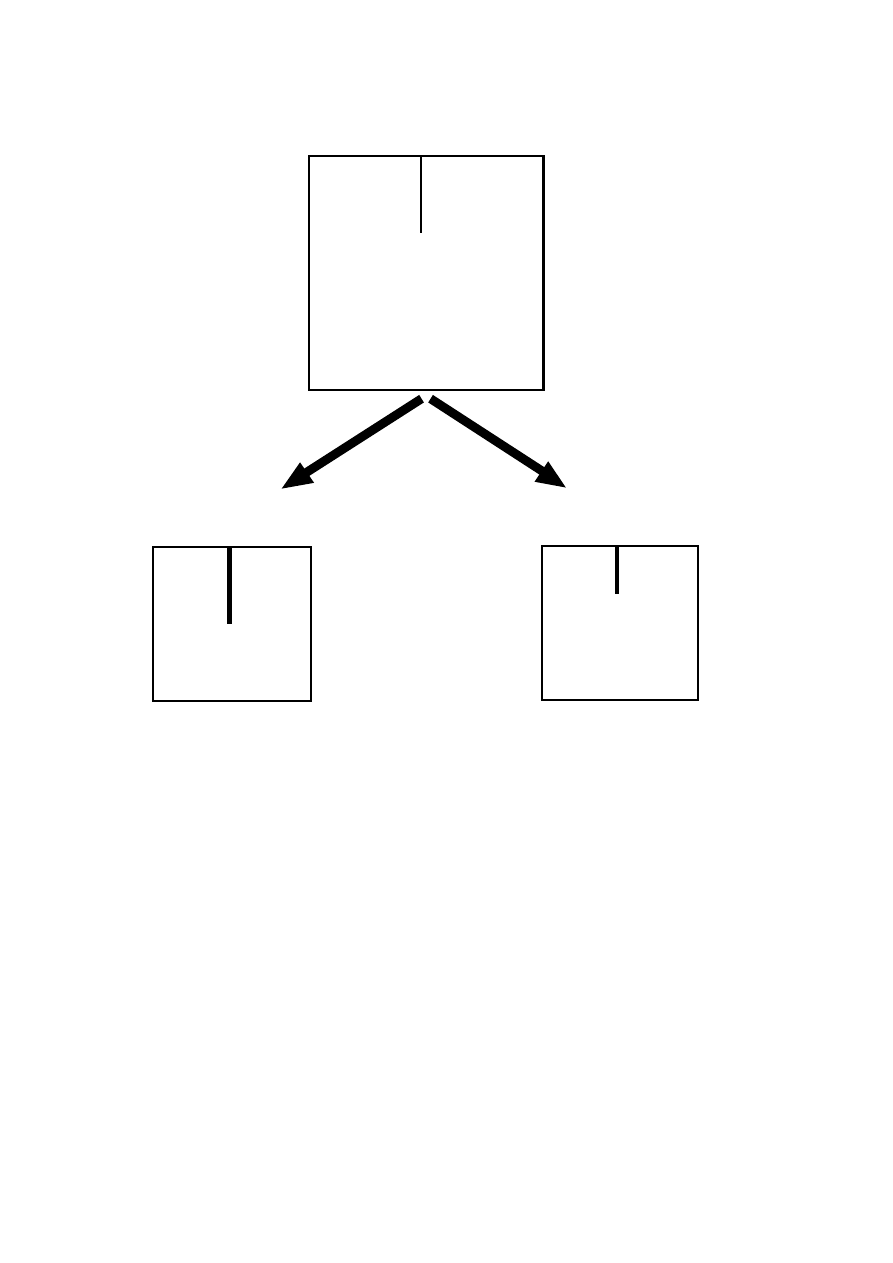

Upon arrival in a lab, participants were explained that they would perform

simple cognitive tasks. They were given both the absolute and the relative tasks in a

counter-balanced order. They received specific instructions for each task right before they

performed it. In both tasks, they were shown a square frame. Within the frame, a vertical

line was printed. The line was extended downward from the upper center of the square

(see Figure 1-A). The participants were then moved to a different table placed in the

opposite corner of the lab (so as to ensure that iconic memory played no role), shown a

second square frame that was either larger, smaller or equal in size to the first frame, and

instructed to draw a line in it. In the absolute task, the participants were instructed to

draw a line in the second frame so that it would be the same absolute length as the line in

the first frame (Figure 1-B). In the relative task, the participants were instructed to draw

a line that had the same proportion to the second frame as the line in the original frame

(Figure 1-C). Care was taken to ensure that the participants understood the respective

tasks by using concrete examples such as the ones given in Figures 1-A through 1-C.

Cultural Look 8

Five different combinations of frames and a line were prepared such that in 2 of

the combinations the first frame was smaller than the second and in 2 of the

combinations the former was larger than the latter. Furthermore, in half of the cases, the

first line was longer than one half of the height of the first square and in the remaining

half, it was shorter than half of its height. Finally, in the remaining one combination, the

first and the second frame were identical in size. This last case is of interest because the

correct response would be identical in both the relative and the absolute judgment. See

Table 1 for specifications of the square size and the line length of the combinations used

in Study 1. The five combinations were presented in a random order. The same set of

target stimuli were used in both the relative and absolute tasks.

Results and Discussion

An inspection of data showed that both over-estimation and under-estimation

happened to a nearly equal extent in all the five stimulus combinations. Accordingly, in

order to assess the performance in the two tasks, the lines drawn by the participants

were measured and the absolute difference between the lines drawn by the participants

and the correct length of the lines were calculated. Because the absolute size of error was

somewhat larger for longer lines, we also analyzed the percent of the error relative to the

correct line length. The results were no different. This was the case in both Studies 1 and

2. We therefore discuss only the results for absolute error.

The mean error scores (in mm) for the two tasks are summarized in Table 1.

These means were submitted to an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with one

between-subject variable (culture of participants [Japanese vs. Americans]) and two

within-subject variables (task [absolute vs. relative] and stimulus version [the five

combinations noted above]). A preliminary analysis had shown that effects do not depend

on either gender of the participants or the order by which the two tasks were given.

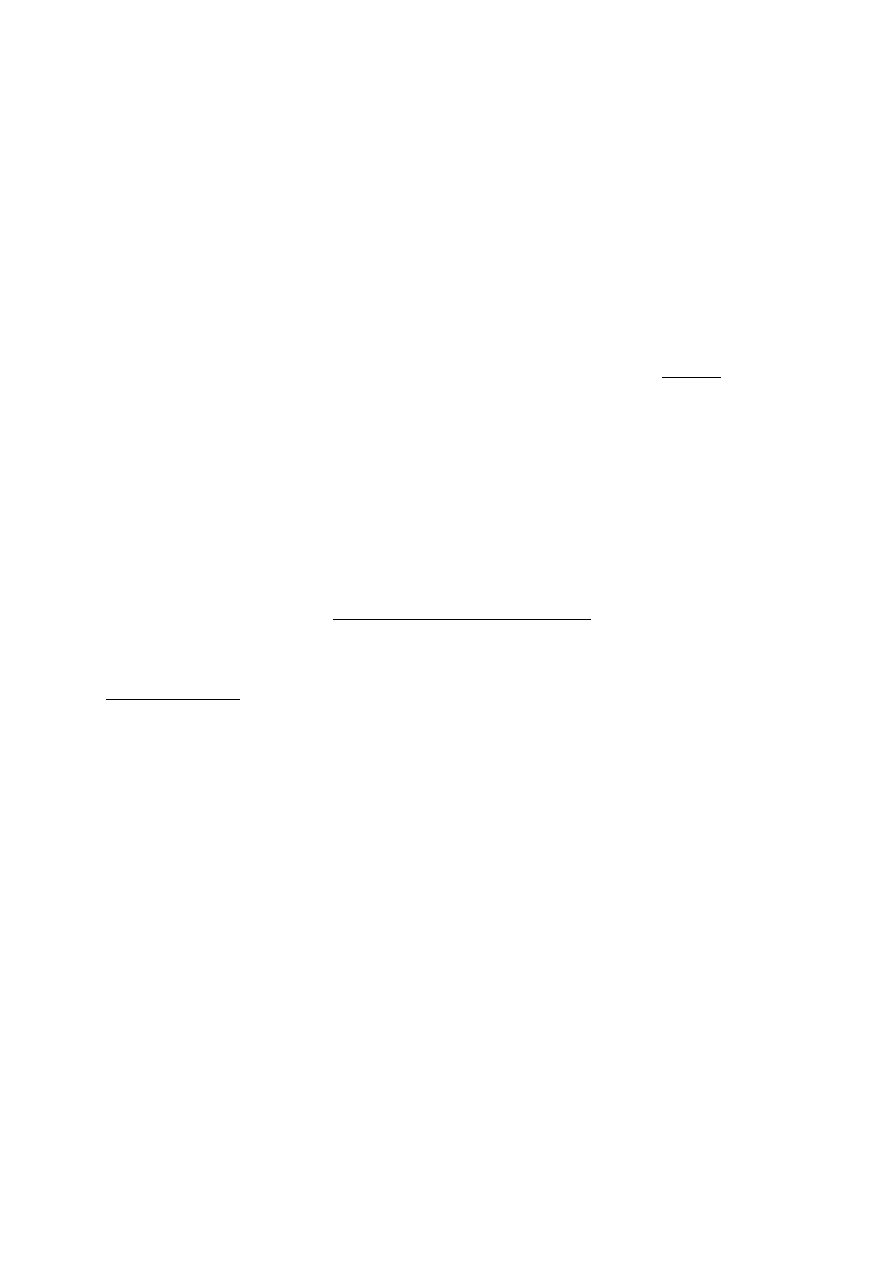

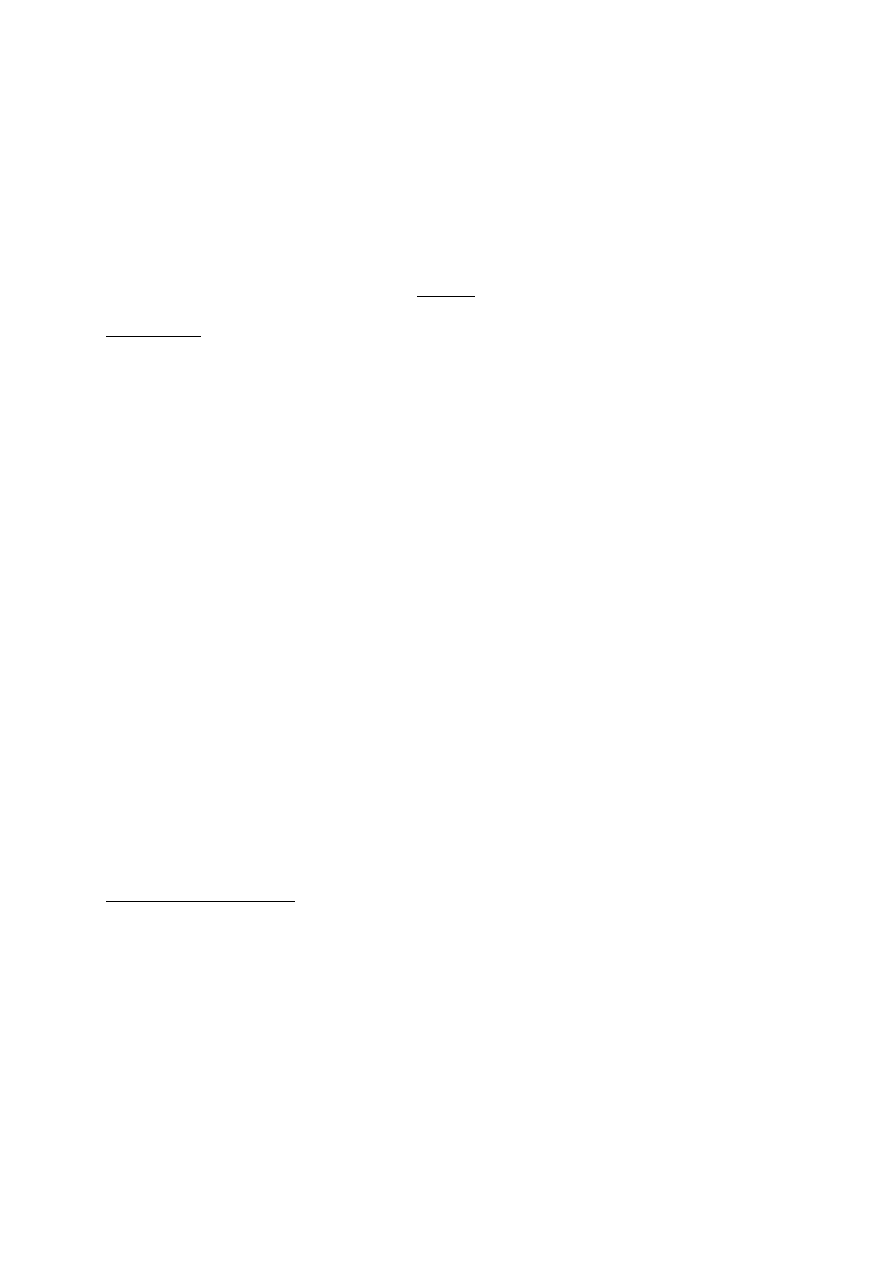

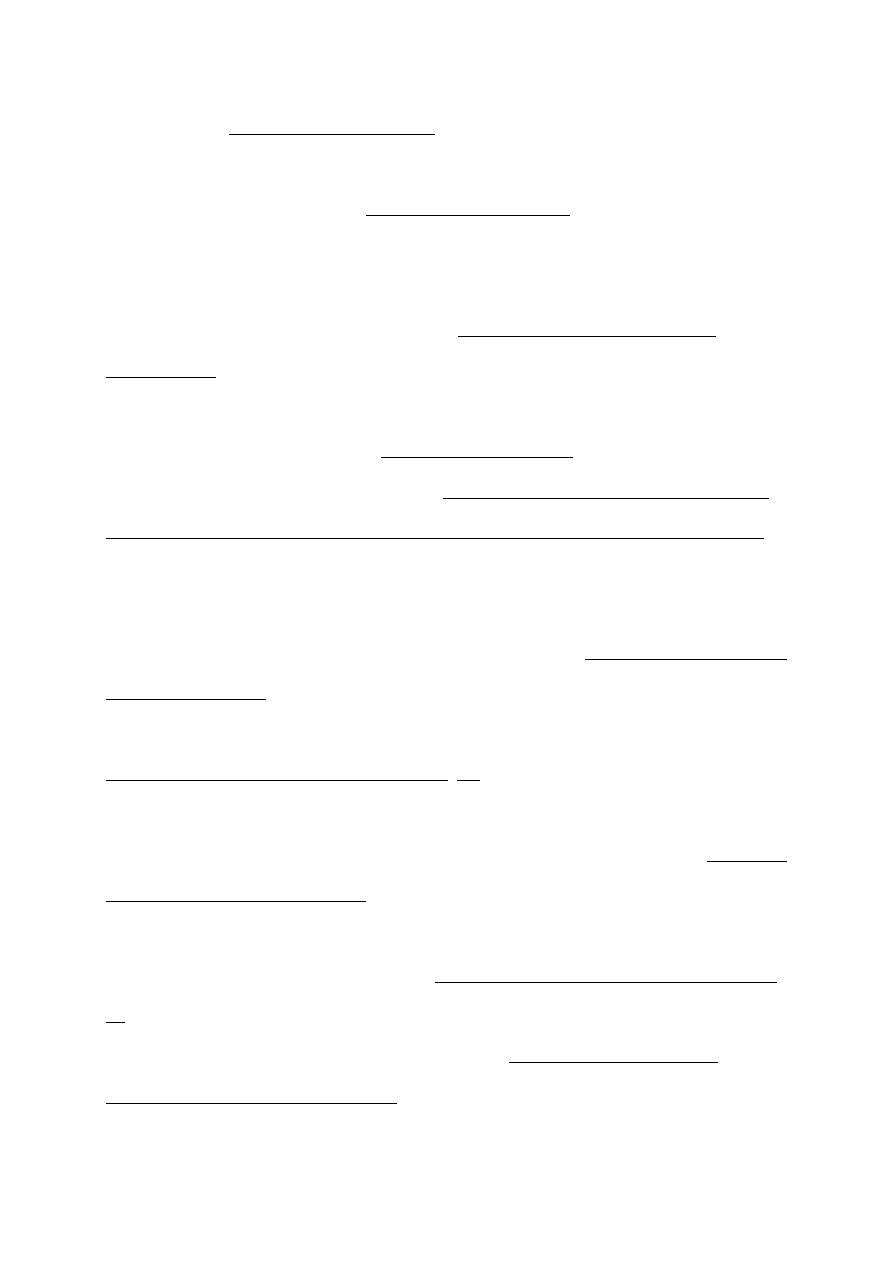

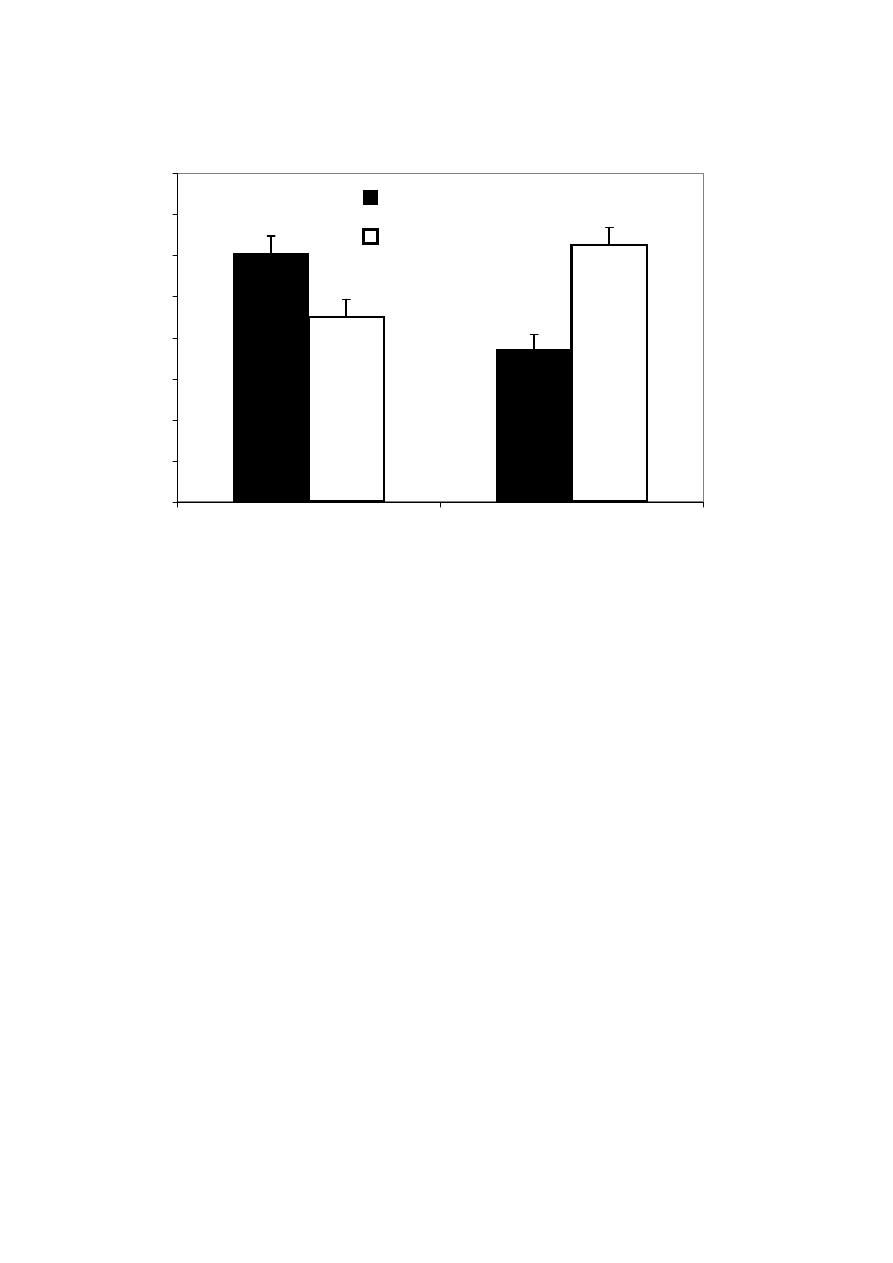

As predicted, an interaction between culture and task proved significant, F(1, 38)

Cultural Look 9

= 24.41, p < .0001. The pertinent means are plotted in Figure 2. As predicted, Japanese

performed the relative task significantly more accurately than the absolute task (Ms =

4.52 vs. 6.05), t(38) = 2.56, p < .02. In contrast, Americans performed the absolute task

more accurately than the relative task (Ms = 3.71 vs. 6.35), t(38) = 4.57, p < .01. Moreover,

the performance in the absolute task was significantly better for Americans than for

Japanese, t(38) = 3.92, p < .01. But the reverse was true for the performance in the

relative task, t(38) = 3.06, p < .01. The pattern was more pronounced for some

combinations than for others as indicated by a significant main effect of version and a

significant interaction between version and task, F(4, 152) = 8.95, p < .001 and F(4, 152) =

9.44, p < .001. Importantly, however, the pattern in Figure 2 emerged, albeit to a varying

degree, over all the five combinations.

Remember when the two frames are identical in

size, the correct length for the relative and the absolute tasks is identical. Curiously, even

here, the same pattern emerged. Specifically, performance for Japanese was significantly

better in the relative task than in the absolute task, t(38) = 2.53, p < .02, but this

difference was considerably attenuated for Americans, t < 1. We return to this issue later.

STUDY 2. VARIABILITY AND MALLEABILITY OF FLT PERFORMANCE

Study 2 sought to replicate Study 1 and, further, to extend it by testing both

Americans and Japanese in both Japan and the United States. This effort was motivated

by a concern with the variability and malleability of cross-cultural variations. If, for

example, the cross-cultural difference is both relatively uniform within each culture and

relatively stable and trait-like over time, then the cross-cultural variation should be

entirely a function of the cultural origins of each participant: Americans (or Japanese)

should show a prototypically American (or Japanese) pattern more or less uniformly

regardless of where they are tested. If, however, the cognitive abilities at issue are both

Cultural Look 10

variable and malleable, there ought to be a considerable variation as a function of both

the cultural origins of participants and the specific location in which they are tested.

Specifically, participants in a foreign culture would show a pattern of cognitive biases

that resembles the pattern typical in the host culture.

Method

Participants

Four groups of individuals (Total N = 111) volunteered for the study. Japanese in

Japan were 32 undergraduates (20 males and 12 females) at Kyoto University, Japan.

They were tested by a Japanese experimenter. Instructions were given in Japanese.

Americans in Japan were 18 exchange students (8 males and 10 females)—all

Americans—who were temporarily staying in Kansai Institute for Foreign Languages.

They had stayed in Japan for four months at most and their Japanese proficiency was

quite limited. They were tested by a Japanese experimenter. Instructions were given in

English. Americans in the US are 40 undergraduates (21 males and 19 females) at the

University of Chicago, and Japanese in the US are 21 Japanese undergraduates (13

males and 8 females) who were temporarily studying at the University of Chicago. These

Japanese stayed at the University for a varying length from 2 months up to four years.

The Americans and the Japanese in the US were both tested by an American

experimenter and instructions were given in English.

Materials and Procedure

Six different combinations of frames and a line were prepared. They were mostly

identical to the ones used in Study 1, except, first, that some of the ratios of the size of the

two frames were somewhat changed and, second, that the pattern with the two frames of

the identical size was run in two variations. See Table 2 for specifications of the square

size and the line length of the combinations used in Study 2. The participants were tested

individually within the same procedure as in Study 1.

Cultural Look 11

Results and Discussion

As in Study 1, there was no systematic tendency for over- or under-estimation in

any of the stimulus combinations. Preliminary analysis showed no significant effects

involving the gender of participants. Although past research tended to show females to be

more context-sensitive than males (Cross & Madson, 1997), this effect appears to be less

robust than the cultural difference.

The means were thus submitted to a 2x2x2x6 ANOVA, with two between-subject

variables (cultural origins of participants [Japanese vs. Americans] and testing location

[Japan vs. US]) and two within-subject variables (task [absolute vs. relative] and

stimulus version [the six combinations noted above]. The mean error scores (in mm) are

summarized in Table 3. The size of error varied systematically across the four groups of

participants, as indicated by a significant main effect for testing location and an

interaction between testing location and participant culture, F(1, 105) = 15.97, p < .0001

and F(1, 105) = 8.25, p < .01. Further, the error size was larger for the absolute task than

for the relative task, F(1, 105) = 39.56, p < .0001. Importantly, however, replicating Study

1, the critical interaction between task and participant culture proved to be highly

significant, F(1, 105) = 10.18, p < .002. Moreover, we also found a highly reliable

interaction between task and testing location, F(1, 105) = 56.19, p < .0001.

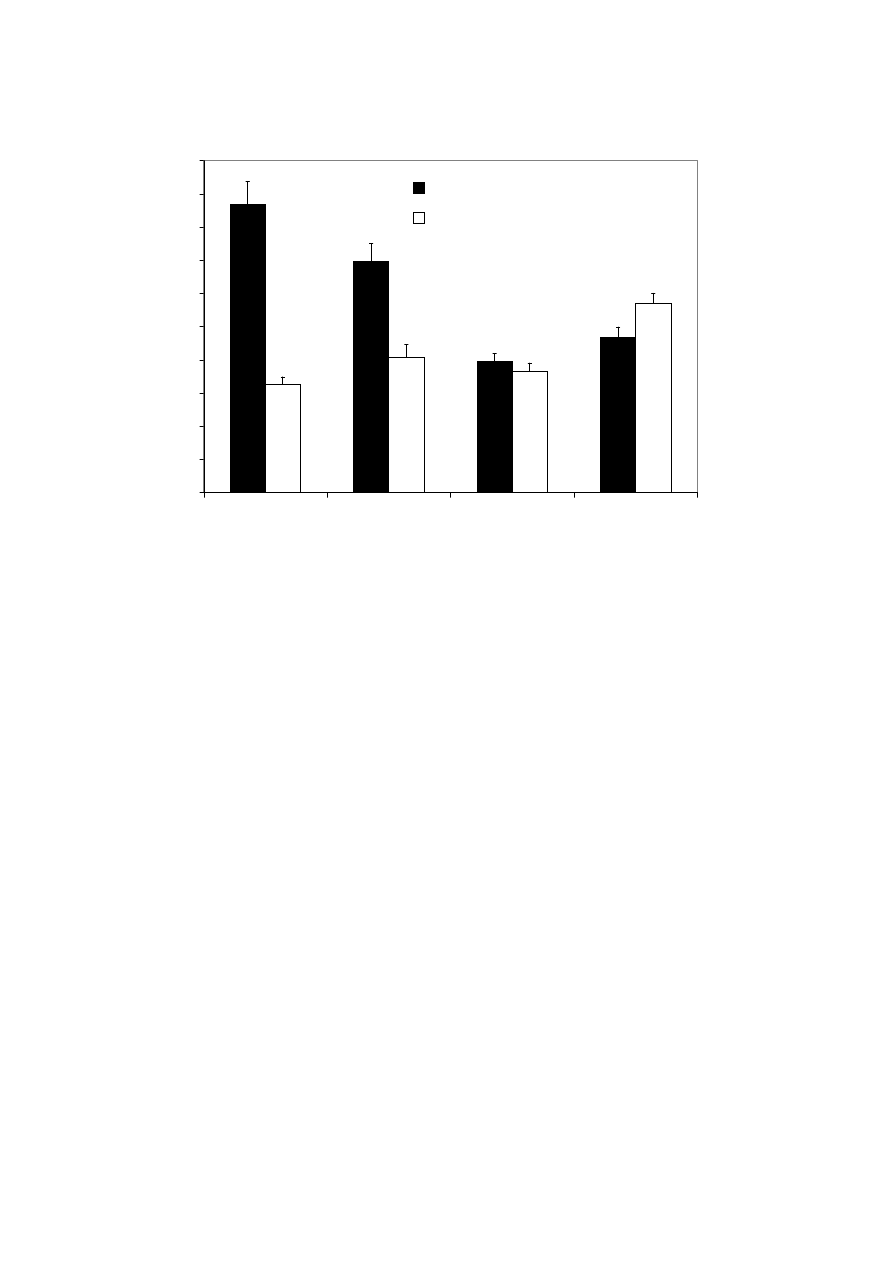

The pertinent means are summarized in Figure 3. Replicating Study 1, Japanese

participants in Japan proved to be much more accurate in the relative task than in the

absolute task, t(105) = 9.90, p < .01. In contrast, Americans in the US were significantly

more accurate in the absolute task than in the relative task, t(105) = 2.15, p < .05. The

remaining two groups of participants showed an effect that strongly resembled the effect

of the host culture. Thus, the pattern for Americans in Japan was closer to the pattern for

Japanese in Japan than to the pattern for Americans in the US. Likewise, the pattern for

Japanese in the US was closer to the pattern for Americans in the US than to the pattern

Cultural Look 12

for Japanese in Japan. When examined from a different angle, the performance in the

relative task was significantly better for Japanese than for Americans, t(105) = 7.84, p

< .001; but the performance in the absolute task was better for Americans than for

Japanese, t(105) = 4.73, p < .001. In both cases, the data in the remaining two groups fell

in-between. It is noteworthy that essentially the same pattern was observed across the

six combinations of stimuli (see Table 2). In particular, as in Study 1, the same

cross-cultural difference in error pattern was observed for the two combinations where

the two frames were equal in size.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Socio-Cultural Shaping of Attention and Perception

In agreement with recent theorizing on cultural variation in cognition (Nisbett et

al., 2001), the current work showed that Japanese are more capable of incorporating

contextual information in making a judgment on a focal object, but North Americans are

more capable of ignoring it. Importantly, we demonstrated the cross-cultural variation in

a non-social task that is specifically designed to simultaneously assess the two cognitive

competences of either ignoring or incorporating context. The FLT may be an important

source of information for a nonsocial, basic cognitive capacity that is recruited in the

making of more complex, contextualized judgments and perceptions. Future research

should clarify both the social origins of the nonsocial cognitive and attentional skills and

processes and the contribution of the nonsocial cognitive and attentional processes to

judgments and inferences made on social objects and events.

We repeatedly found the same cross-cultural variation in error pattern even

when the two frames were identical. This finding contradicts the notion that Asians (or

Americans) are predisposed to perform the relative (or the absolute) task even when they

Cultural Look 13

were instructed to do otherwise. Should individuals have these predispositions, errors

should have been minimum when the two frames were identical because, under these

conditions, the answers of the two tasks converge. In view of the current evidence, we

may suggest that errors were due, in part, to a difficulty in accurately encoding the

central line. That is to say, whereas Japanese may have had a difficulty in releasing

attention from the frame and then refocusing it on the line in the absolute task,

Americans may have had a difficulty in releasing attention from the central line and

shifting it to the frame in the relative task. It is of note that the errors in the two tasks of

the FLT were largely independent within each experimental group in the both studies

(-.08 < r < .44, with the medium = -.06), indicating that the two attentional abilities are

mostly separate. Yet, in both cases, the difficulty in controlling attention may be expected

to cause an impairment in the adequate encoding of the line. Future work should

examine this and other mechanisms in greater detail.

Limitations

The effects of cultural origins of participants and test locations in Study 2 are

quite suggestive, but require caution in interpretation. One provocative interpretation is

that the effect of test location was caused by immersion into a new culture. That is to say,

cognitive and attentional capacities and tendencies may be modified in accordance with

new demands and affordances of living in a new host culture (Kitayama, Markus,

Matsumoto, & Norasakkunkit 1997). Importantly, this modification can be permanent

once it takes place or relatively temporary and reversible, with an important implication

in what might be expected to happen when our participants go back to their home country.

Nevertheless, for a variety of practical constraints associated with cross-cultural

experimental research, we could not exercise the degree of experimental control that

would have otherwise been obligatory. Among others, we depended entirely on

convenience samples. We wish to acknowledge three ensuing difficulties in

Cultural Look 14

interpretation.

First, the average length of stay in the host cultures turned out to be very different

between the Americans in Japan and Japanese in the US. Although this variable did not

correlate with the error size in the two tasks, a better balanced sampling would have been

desirable.

Second, the language used for instructions was also chosen for convenience. In

particular, in the US not only Americans but also Japanese were tested in English, but in

Japan participants were tested in their native languages. This might have had an

unknown degree of influence on the results because evidence indicates that language can

prime the associated culture (Hoffman, Lau, & Johnson, 1986; but see Ishii et al., in press,

for an important caveat).

Third, both the Japanese participants in the US and the American participants in

Japan were people who voluntarily moved to the other culture. Though obtained effects

on cognitive biases may have been due to immersion in a new culture, the possibility of

selection bias is equally viable. That is to say, only those people who have psychological

affinities to another culture may find themselves living in this other culture. Although

these explanations for the effect of test location are not mutually exclusive, future work

should empirically address their relative significance.

Conclusion

Culture is a source of generic expectations, default goals, desires, and needs, and

overarching values. Cultural variations in attention, perception, and cognition, then,

would enable us to take a renewed look at the New Look (Bruner, 1994). The current work

suggests that culture’s practices and beliefs encourage very divergent cognitive and

attentional capacities—the ones to either incorporate or ignore context while making a

judgment about a focal object.

Future work along the line proposed here may reveal a degree of socio-cultural

Cultural Look 15

shaping of attention and perception that is substantially greater than has so far been

assumed in the psychological literature. If so, this evidence would provide a solid basis to

re-conceptualize the human psychological processes and structures as fully embedded in

and thus significantly constituted by the collectively shared practices, values, and beliefs

of culture (Kitayama, 2002). Indeed, if properly analyzed, the thesis of the New Look will

be instrumental in breaking a self-imposed shell of the traditional psychological

discipline and broadening its horizon to include society, culture, and history in its

territory of investigation.

Cultural Look 16

References

Bruner, J. (1957). On perceptual readiness, Psychological Review, 64, 123-152.

Bruner, J. (1994). The view from the heart’s eye: A commentary. In P. M.

Niedenthal, P., & S. Kitayama (Eds.), The heart's eye: Emotional influences in perception

and attention (pp. 269-286). Academic Press.

Bruner, J., & Goodman, C. C. (1947). Value and need as organizing factors in

perception. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42, 33-44.

Cross, S. E., & Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: Self-construals and

gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 5-37.

Erdelyi, M.H. (1974). A new look at the new look: Perceptual defense and

vigilance. Psychological Review, 81, 1-25.

Higgins, E. T., & Bargh, J. A. (1987). Social cognition and social perception.

Annual Review of Psychology, 38, 369-425.

Hoffman, C., Lau, I., & Johnson, D.R. (1986). The linguistic relativity of person

cognition: An English-Chinese comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

51, 1097-1105.

Ishii, K., Reyes, J. A., & Kitayama, S. (in press). Spontaneous attention to word

content versus emotional tone: Differences among three cultures. Psychological Science.

Ji, L. J., Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. E. (2000) Culture, control, and perception of

relationship in the environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78,

943-955

Kitayama, S. (2000). Cultural variations in cognition: Implications for aging

research. In P.C. Stern & L.L. Cartensen (eds.), The aging mind: Opportunities in

cognitive research (pp. 218-237). Washington, D. C.: National Academy Press.

Kitayama, S. (2002). Culture and basic psychological processes: Toward a system

Cultural Look 17

view of culture. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 189-196.

Kitayama, S., & Ishii, K. (2002). Word and voice: Spontaneous attention to

emotional speech in two cultures. Cognition and Emotion, 16, 29-59.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., Matsumoto, H., & Norasakkunkit, V. (1997).

Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: Self-enhancement in

the United States and self-criticism in Japan. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 72, 1245-1267.

Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for

cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Masuda, T., & Kitayama, S. (2002). Perceiver-imposed constraint and attitude

attribution in Japan and the US: A case for culture-dependence of correspondence bias.

Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan.

Masuda, T., & Nisbett, R. E. (2001). Attending holistically vs. analytically:

Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 81, 922-934.

Miller, J. G. (1984). Culture and the development of everyday social explanation.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 961-978.

Miyamoto, Y., & Kitayama, S. (in press). Cultural variation in correspondence

bias: The critical role of attitude diagnosticity of socially constrained behavior. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology.

Morris, M. W., & Peng, K. (1994). Culture and cause: American and Chinese

attributions for social and physical events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

67, 949-971.

Niedenthal, P., & Kitayama, S. (Eds., 1994). The heart's eye: Emotional

influences in perception and attention. Academic Press.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems

Cultural Look 18

of thought: Holistic vs. analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108, 291-310.

Postman, L., Bronson, W. C., & Gropper, G. L. (1953). Is there a mechanism of

perceptual defense? Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 48, 215-224.

Witkin, H. A., & Berry, J. W. (1975). Psychological differentiation in

cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 6, 4-87.

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inference.

American Psychologist, 35, 151-175

Cultural Look 19

Table 1. Mean error scores in the absolute versus relative line-drawing tasks by Japanese

and Americans (Study 1, the metric is in terms of mm in all cases).

Height Length Height

of 1

st

of

of 2

nd

Japanese American

Frame Line

Frame

89 62 179

Absolute

Task

M

6.8

2.2

SD

(5.0)

(2.1)

Relative

Task

M

6.3

10.6

SD

(4.8)

(4.1)

102 29 153

Absolute

Task

M

3.6

2.5

SD

(4.9)

(2.5)

Relative

Task

M

5.7

6.2

SD

(5.9)

(4.0)

127 53 127

Absolute

Task

M

7.1

3.8

SD

(4.7)

(4.0)

Relative

Task

M

4.0

4.5

SD

(3.3)

(3.5)

153 87 102

Absolute

Task

M

9.0

6.1

SD

(4.9)

(4.6)

Relative

Task

M

4.2

6.6

SD

(3.4)

(5.0)

179 31 89

Absolute

Task

M

3.6

3.8

SD

(2.9)

(3.6)

Relative

Task

M

2.3

3.7

SD

(2.7)

(2.5)

Cultural Look 20

Table 2. Mean error scores in the absolute versus relative line-drawing tasks by Japanese

and Americans in both Japan and the US (Study 2, the metric is in terms of mm in all

cases).

Height Length Height

of 1

st

of

of 2

nd

Japanese

Americans

Japanese Americans

Frame Line

Frame

in Japan

in Japan

in the US in the US

81 68 162

Absolute

Task

M 9.2

6.6

4.1

3.4

SD

(5.7)

(5.7)

(3.0)

(2.9)

Relative

Task

M 4.3

3.6

5.7

7.7

SD

(3.5)

(2.6)

(3.2)

(7.4)

108 22

162

Absolute

Task

M 5.1

3.2

3.2

4.1

SD

(5.1)

(2.7)

(2.3)

(2.6)

Relative

Task

M 3.1

5.8

3.0

3.9

SD

(2.0)

(4.4)

(2.4)

(3.4)

101 28

101

Absolute

Task

M 8.1

5.4

4.0

4.2

SD

(6.7)

(7.0)

(2.8)

(3.0)

Relative

Task

M 3.1

2.7

2.9

4.4

SD

(2.0)

(1.8)

(2.6)

(2.9)

141 102

141

Absolute

Task

M

14.5

14.0

3.3

6.5

SD

(10.1)

(9.1)

(2.9)

(4.7)

Relative

Task

M 3.9

5.1

4.7

8.4

SD

(2.8)

(4.1)

(3.3)

(5.6)

108 73

81

Absolute

Task

M 8.0

7.8

4.8

5.3

SD

(4.4)

(3.5)

(3.3)

(3.8)

Relative

Task

M 3.0

4.2

2.8

5.6

SD

(2.2)

(4.8)

(2.4)

(4.0)

162 30

81

Absolute

Task

M 6.7

4.6

3.9

4.2

SD

(7.0)

(3.6)

(2.4)

(3.2)

Relative

Task

M 2.0

2.8

2.7

3.9

SD

(1.9)

(1.7)

(2.0)

(2.2)

Cultural Look 21

Figure 1-A. The original stimulus

Figure 1-B. The absolute task

Figure 1-C. The relative task

Square=90 mm tall

Line=30 mm/

one third of the

height of the

square

30 mm

one third of

the height of

the square

Figure 1. Framed Line Test (FLT). Participants are shown a square frame with a vertical

line, followed by the tasks of drawing a line in a new square of the same or different size.

The line has to be identical to the first line either in absolute length (Figure 1-B) or in

proportion to the height of the respective frames (Figure 1-C).

Cultural Look 22

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Jap anese

A m ericans

C ulture

Mean Absolute Error (mm)

A b solu te T ask

R elative T ask

Figure 2. Mean error scores (in mm) in the two line drawing tasks of FLT for Japanese

and Americans.

Cultural Look 23

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1 0

Jap an ese in

Jap an

A m erican s in

Jap an

Jap an ese in

A m erica

A m erican s in

A m erica

Mean Absolute Error (mm)

A b solu te T ask

R elative T ask

Figure 3. Mean error scores (in mm) in the two line drawing tasks of FLT for Japanese

and Americans in the two cultural locations (i.e., Japan and the United States).

Document Outline

- Culture and Cognition

- Present Research

- Method

- Participants

- Participants

- Materials and Procedure

- Socio-Cultural Shaping of Attention and Perception

- In agreement with recent theorizing on cultural variation in cognition (Nisbett et al., 2001), the current work showed that Japanese are more capable of incorporating contextual information in making a judgment on a focal object, but North Americans ar

- Limitations

-

-

- The effects of cultural origins of participants and test locations in Study 2 are quite suggestive, but require caution in interpretation. One provocative interpretation is that the effect of test location was caused by immersion into a new culture. That

- First, the average length of stay in the host cultures turned out to be very different between the Americans in Japan and Japanese in the US. Although this variable did not correlate with the error size in the two tasks, a better balanced sampling would

- Second, the language used for instructions was also chosen for convenience. In particular, in the US not only Americans but also Japanese were tested in English, but in Japan participants were tested in their native languages. This might have had an unkn

- Third, both the Japanese participants in the US and the American participants in Japan were people who voluntarily moved to the other culture. Though obtained effects on cognitive biases may have been due to immersion in a new culture, the possibility of

-

-

- Conclusion

- HeightLengthHeight

- HeightLengthHeight

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Analysis of soil fertility and its anomalies using an objective model

Analysis of soil fertility and its anomalies using an objective model

Roy Childs Objectivism and the State An Open Letter to Ayn Rand

Magnetic Treatment of Water and its application to agriculture

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Extract from Armoracia rusticana and Its Flavonoid Components

[38]QUERCETIN AND ITS DERIVATIVES CHEMICAL STRUCTURE AND BIOACTIVITY – A REVIEW

Angielski tematy Performance appraisal and its role in business 1

conceptual storage in bilinguals and its?fects on creativi

Motivation and its influence on language learning

Pain following stroke, initially and at 3 and 18 months after stroke, and its association with other

The Vietnam Conflict and its?fects

International Law How it is Implemented and its?fects

Central Bank and its Role in Fi Nieznany

Piórkowska K. Cohesion as the dimension of network and its determianants

Lumiste Betweenness plane geometry and its relationship with convex linear and projective plane geo

więcej podobnych podstron