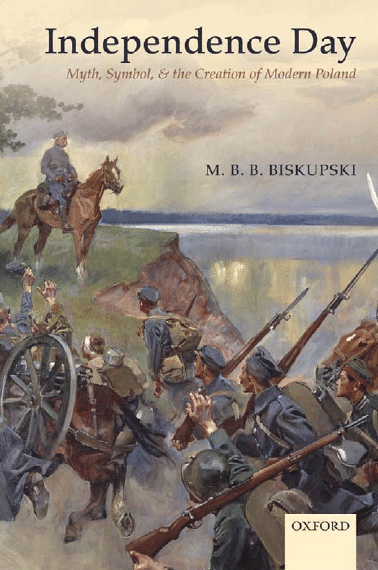

I N D E P E N D E N C E D AY

This page intentionally left blank

Independence Day

Myth, Symbol, and the Creation of

Modern Poland

B Y M . B . B . B I S K U P S K I

1

3

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© M. B. B. Biskupski 2012

Th

e moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2012

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted

by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics

rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the

above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press,

at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 978–0–19–965881–7

Printed in Great Britain by

MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and

for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials

contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Jankowi Biskupskiemu, który zawsze był mi wzorem

starszego brata, tę książkę poświęcam

This page intentionally left blank

Foreword

Th

e essential content of history is legend, but the form of history is founded on

myth.

Stefan Czarnowski

1

Many years ago, I was going over the papers of my late great-grandmother. Born in

Mazowsze near Warsaw, she had married an older man who had come from the

former northeastern borderlands of historic Poland. I was only a small child, and

had no conception of Polish politics or the symbols which have, to such a striking

degree, explained them. However, I found amongst these papers a picture of an old

man in a simple uniform taking a walk. He was, I later discovered, Józef Piłsudski:

a controversial fi gure in the modern history of our ancestral homeland. It was the

only picture with a Polish theme that my grandmother kept.

Years later, I noticed that my mother, a pianist, would occasionally play an odd

song on her piano, which I later learned was called My, Pierwsza Brygada [We, the

First Brigade]. She would always burst into song—she had a very weak voice—and

become very emotional. What this meant, I had no idea, but my family was always

moved by it. It was the anthem of Piłsudski’s loyalists.

It seems I was born into a Piłsudskiite family. What this meant had no signifi -

cance for me. Later I discovered it meant a great deal, but exactly what I have never

decided. Th

e purpose of writing this book is to explore the meaning of the symbols

and characters of my childhood to fi nd answers that satisfy me and, I trust, will

prove of value to others for whom the history of Poland is a fascination.

Th

is book is a radically revised version of a lecture presented at the Institute on

East Central Europe at Columbia University on November 18th, 2002. It is based,

in part, on research carried out—for a far diff erent project—during 1998–99 as an

External Fellow of the Open Society Archives of the Central European University

in Budapest.

2

My research assistant then was Izabella Main of the Jagiellonian

University in Kraków. She has gone on to make her own contributions to a fi eld

not far distant from the questions which intrigue me.

I should like to thank John Mićgiel of Columbia University for whom I fi rst

prepared a draft of the original project; Piotr S. Wandycz of Yale; Anna M. Cienciała

of the University of Kansas; my colleague Jay Bergman, the younger brother I never

had, who read the manuscript and off ered his always sage comments, correcting

many minor slips and, more importantly, raising insightful questions about the

arguments. Among others, I should single out John P. Bermon who has provided

1

Quoted in Wanda Nowakowska, “3 Maja w lararskiej legendzie,” in Alina Barszczewska-Krupa,

ed., Konstytucja 3 maja w tradycji i kulturze polskiej (Łódź: Wydawnictwo łódzkie, 1991), 572 .

2

All references to material from this collection will henceforth be designated as OSA, CEU.

wise counsel, and Waldemar Kostrzewa for unswerving friendship. My youngest

children Misia and Staś would occasionally type things in the manuscript which I

later edited out. Whether this worked as an improvement or not is an open question.

My older children, Olesia, Jadzia, and Mietek, supported me with their devotion.

Finally, I dedicate this book to my brother, Janek, whom I love.

Colchester, 2012

viii

Foreword

Contents

e Myths and Symbols of Independence Day

2. Discovering Independence Day

3. Contesting a National Myth, 1918–26

4. Formalization of a Discourse, 1926–35

5. Independence Day and the Celebration of Piłsudski’s

6. Maintaining a Piłsudskiite Independence Day, 1939–45

7. Independence Day as Symbol of Protest

Independence Day: A Confl icted History

November 11th, 1918, Polish Independence Day, is a curious anniversary whose

commemoration has been observed only intermittently in the last century. In fact,

the day—and the several symbols that rightly or wrongly have became associated

with it––have a rather convoluted history, fi lled with tradition and myth, which

deserve our attention.

3

For, as Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna lectured her countrymen,

a Pole must learn his “list of symbols.”

4

Between 1918 and 1939—during the Polish Second Republic—the 11th was

increasingly regarded as the principal patriotic anniversary in Poland, marking the

return of the country to the ranks of independent states after more than a century of

non-existence—the partition era, 1771–95, when Poland was occupied by Russia,

Austria, and Prussia-Germany. Only the observance of May 3rd, the day the abortive

constitution of 1791 was signed, was its rival. Th

at day, redolent with paradoxical

memories of a momentary fl ash of victory in a sky of darkness, always had something

November 11th has never had: its own anthem, a lilting and nostalgic paean to lost

hopes.

5

Nonetheless, the importance of May 3rd, so symbolically important in the

nineteenth century, visibly faded after the re-establishment of independence.

6

In 1939, World War II interrupted this observation, and after 1945, the com-

munist authorities preferred to ignore the occasion. Indeed, they found the date

most unpleasant. Only since the re-establishment of a truly sovereign government

3

Some have speculated that national holidays in Poland have a diff erent psycho-social function

than is the case in the West. In the latter case such days are truly national celebrations and hence joy-

ful; in Poland they are really remembrances of national martyrology and hence restrained, even

somber. See “11 listopada, czyli zapomniana duma,” Gazeta Krakowska , November 11, 2008. “Brakuje

nam radośnych świat,” Rzeczpospolita , November 10, 2006. Th

ere is also the speculation that Novem-

ber 11th has traditionally lacked an enthusiastic following in Poland because the weather in that

month is often unpleasant; c.f. the comments of the cultural anthropologist Mariola Flis in “Smutni

w święto?,” Dziennik Polski , November 12, 1998; a meteorological exegesis is provided in Zdzisław

Kościelak, “Smuta narodowa,” Wprost , 1042, November 17, 2002.

4

Danuta Zamojska-Hutchins, “Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna: Th

e Poet as a Witness of History, and

of Double National Allegiance,” in Celia Hawkesworth, ed., Literature and Politics in Eastern Europe

(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 103 .

5

Witaj, majowa jutrzenko was written by Rajnold Sucholdolski in April 1831. Everything about

the song was—and is—sentimental. It appeared in the midst of an ill-fated uprising against the Rus-

sians (the November Rising, 1830–1831), it recalled the promise of the 1791 Constitution, and

whispered about the glories of old Poland, and the trials of the subsequent years.

6

See for example, Jerzy Kowecki, “Wstęp,” in his Sejm czteroletni i jego tradycje (Warsaw: Państwowe

Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1991) , 5ff . Even during the war, the Legion camp would note May 3rd in the

context of celebrating the Legions; see Barbara Wachowska, “Uroczystości trzeci majowe w sporach o

drogę do niepodległości w okresie I wojny światowej,” in Barszczewska-Krupa, Konstytucja 3 maja , 173.

May 3rd was already fading by 1918; see ibid., 178. For a devastating criticism of why the constitution

was a “conspicuous failure of imagination”, see Andrzej Walicki, “Intellectual Elites and the Vicissitudes

of “Imagined Nation” in Poland ,” East European Politics and Societies , 11 (1997), 239 .

Preface

xi

in Warsaw in 1989 has November 11th regained its pre-1939 importance. Indeed,

the restoration of November 11th, 1918 is part of a larger phenomenon of resus-

citating and reconceptualizing the Polish Second Republic that was born on that

day, or at least so it was assumed. Th

is project goes hand in hand with how the

Polish People’s Republic (PRL)—communist Poland—can be integrated into the

national narrative. Contemporary Poland is not the Second Republic reincarnated,

and November 11th is not what it was more than fi fty years earlier. What the func-

tion of November 11th is in today’s Poland is the question we shall consider in our

concluding remarks.

Indeed, Independence Day is really a history of responses to evolving historical

dilemmas confronting the modern Polish nation. In the initial years, 1918–26, it

provided an answer—but a controversial one—to the question of exactly when

and how Poland was re-created; which really asks which forces were responsible for

the state’s reappearance on the map and how they accomplished it. It is an inquiry

about whom or what deserves credit. Here Józef Piłsudski’s acolytes insisted that it

was their hero, and the legions he created and led, which were solely responsible

for the resurrection of the homeland. Others may have played a role, but they were

dispensable or at best incidental.

Th

is interpretation was not without its rivals in the fi rst years of independence.

Indeed, the political right off ered counter-narratives which competed with the

Piłsudski-legion symbol. Th

e success of these projects refl ected the power Piłsudski

exercised in the new Poland. When Piłsudski retired from an active role in public

aff airs after 1922, the celebration of November 11th became less important and

received no promotion from the government.

After 1926, however, Piłsudski returned to power, and in a far more dominating

way than ever before. As a result, Independence Day became synonymous with the

attempt to construct a new Poland—a project associated with Piłsudski and his

entourage, the so-called sanacja . Th

eir story was simple. Th

e authors of Poland were

Piłsudski and his followers in the World War I legions. It was this small but dedi-

cated group which, through sacrifi ce and in the face of obstacle and derision, had

brought Poland back to life. Th

ey represented a re-animation of forces in Polish

history—long dormant, yet very powerful—which galvanized the nation. No out-

side agencies deserved credit for Poland’s rebirth; it was an entirely national project.

Indeed, there was an eff ort to invent a modern Poland in 1926 complete with new

symbols and values, a project which proved radically challenging to conservative

forces—a phenomenon Eva Plach has referred to as the “clash of moral nations.”

7

November 11th was the initiation ritual of modern Poland. Th

e years following

1926 saw Independence Day become ever larger, and more ancillary projects were

associated with it. Greater credit was invested in Piłsudski, and the Piłsudskiite

explanation of how Poland was reborn crowded out all other narratives. New symbols,

or perhaps, charitably, newly discovered symbols, multiplied to broaden and deepen

the nexus between November 11th and Piłsudski. Th

ere was another process at

7

Eva Plach, Th

e Clash of Moral Nations: Cultural Politics in Piłsudski’s Poland, 1926–1935 (Athens:

Ohio University Press, 2006) .

xii

Preface

work: November 11th meant a retrospective reconstruction of what Poland was,

and a projection of what it should be. It was a national philosophy.

During World War II, Independence Day served a dual function. In occupied

Poland, it was substantially a symbol of hope and defi ance rather than a partisan

interpretation. To mark Independence Day meant to demonstrate the continued

existence of Poland despite German or Soviet domination. It was not necessarily a

celebration of the Piłsudski tradition—though the Piłsudskiites were its principal

acolytes—it was an assertion that the pre-invasion Poland endured. Hence, it was

a gesture of national unity.

However, amongst the Poles in exile, the day was radically divisive. To the

sanacja, in power when Poland was defeated in 1939, and now scattered about in

powerless and despondent exile, Independence Day meant the project they had

represented since 1918: it was Piłsudski and his faithful that had created and

shaped Poland.

Th

is understanding was resented by the Polish government-in-exile, espe-

cially its dominating fi gure, General Władysław Sikorski. It was they and not

the pre-1939 sanacja that created and led the exile government. Th

ey were

Poland’s future. Th

e Piłsudskiites were marginalized except in the army, where

they were a powerful force. To Sikorski, November 11th was unpleasantly,

unfortunately, and inextricably associated with his hated rival Piłsudski. It

could not be eliminated because that would leave Poland without a day to

celebrate its reappearance on the map. But the occasion could be ignored, or at

least obfuscated, and as far as possible purged of its Piłsudskiite connotations.

November 11th was a day of controversy: a nostalgic reminiscence for some,

an awkward problem for others.

No version of the pre-war or exile government returned to post-war Poland.

A new regime closely associated with the Soviet Union appeared instead. For them,

November 11th was a serious problem. It was indubitable that November 1918

marked the return of the Polish state to the map. But, in their eyes, the September

defeat inculpated the 1918–39 regime. It was a radically fl awed Poland, which

really gained a hollow victory in 1918 and failed to re-create itself as a socialist state

with the correct geopolitical orientation. At worst, it was a fascist opponent of the

Soviet Union, and therefore the enemy of the Polish people. For this new regime—

the PRL—November 11th was a birthday best forgotten, and its symbol, Piłsudski,

was an opponent of communism in Poland and a foe of the Soviets. He was thus

opposed to the true interests of the Polish people. He, too, was to be consigned to

the category of the unremembered.

During the long years of communist rule, November 11th and its associated

symbols—Piłsudski, his legions, members of his entourage, his victory over the

Russians in 1920—were used by the anti-communist opposition to remind the

population of another, former free Poland. November 11th was a project designed

to oppose the regime. It was not a blueprint for how to rebuild Poland. It was a

symbol of opposition.

When Poland regained its independence in 1989, it quickly replaced July 22nd,

1944—when the so-called Lublin government was created at the behest of the

Preface

xiii

Soviets—with November 11th as Poland’s Independence Day. But, what did this

mean? Was it a symbolic reversion to the Second Republic, a kind of conjuring of

the past by invoking its symbols; an attempt to obliterate the PRL from Poland’s

historic project? Or was it merely a gesture, perhaps arcane to the great majority of

Poles? November 11th is now back, but, so what?

This page intentionally left blank

AK

Armia Krajowa (Polish Underground Army)

BBWR

Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem (Non-Partisan Bloc for

Support of the Government)

BDMP

Biuletyn Dzienny Ministerswtwa Publicznego (Daily Bulletins of the

Ministry of Public Security)

DZS

Dokumenty Życia Społecznego

endecja

Narodowa Demokracja (National Democrats)

FJN

Front Jedności Narodowej (National Unity Front)

GGC

Grudzińska Gross Collection

IKC

Illustrowany Kurjer Codzienny (Illustrated Daily Courier)

KIK

Klub(y) Inteligencji Polskiej (Club(s) of the Catholic Intelligentsia)

KNP

Komitet Narodowy Polski (Polish NationalCommittee)

KOR

Komitet Obrony Robotników (Workers’ Defense Committee)

KOS

Komitet Oporu Społecznego (Committee of Social Resistance)

KPN

Konfederacja Polski Niepodległej (Confederation of Independent Poland)

KRN

Krajowa Rada Narodowa (National Home Council)

KTSSN

Komisja Tymczasowa Skonfederowanych Stronnictw

Niepodległościowych (Temporary Coordinating Commission of

Confederated Independence Parties)

LPR

Liga Polskich Rodzin (League of Polish Families)

NKN

Naczelny Komitet Narodowny (Supreme National Committee)

OWP

Obóz Wielkiej Polski (Camp of Great Poland)

OZON

Obóz Zjednoczenia Narodowego (Camp of National Unity)

PDP

Polish Dissident Publications

PDP

Polish Dissident Publications

PDS

Polskie Drużyny Strzeleckie (Polish Rifl e Brigades)

PiS

Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice)

PKWN

Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego (Committee of National

Liberation)

POW

Polska Organizacja Wojskowa (Polish Military Organization)

PPS

Polska Partia Socjalistyczna (Polish Socialist Party)

PRL

Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (Polish People’s Republic)

PUP

Polish Underground Publications

ROPCiO

Ruch Obrony Praw Człowieka i Obywatela (Movement for the

Defense of Human and Civic Rights)

SD

Stronnictwo Demokratyczne (Alliance of Democrats)

ZBOWiD Związek Bojowników o Wolność i Demokrację (Society of Fighters

for Freedom and Democracy)

ZPP

Związek Patriotów Polskich (Union of Polish Patriots)

ZSL

Zjednoczone Stronnictwo Ludowe (United Peasant Party)

ZWC

Związek Walki Czynnej (Union of Armed Struggle)

This page intentionally left blank

S O L D I E R S A N D M A RT Y R S

Henryk Abczyński trekked through the steamy jungles of Paraná in Brazil, often

lost, perpetually confused. Day laborers from Brooklyn gamboled about the

farmland of the Hudson valley wearing preposterously mismatched uniforms;

children of Siberian exiles, eking out a marginal existence in Manchuria, assem-

bled in Harbin; superannuated romantics brandishing antique swords paraded

through provincial towns in Russia. All were responding to the inchoate yet

almost universal conviction of Polish patriots in 1914 that the formation of armed

units was an effi

cacious, indeed necessary, means to the restoration of national

independence.

1

By the eve of World War I, this mania for military preparation, what we shall

call the legion movement, was so widespread that parties associated with both

the political Left and the nationalist Right, Poles supporting the war aims of the

Entente—England, France, and Russia—and those enrolling in the service of

the Central Powers, all regarded an army as a major element in their political

strategy. Several trends had coalesced to create this phenomenon, which had

deep roots in Polish political thought. Indeed, Tomasz Nałęcz has argued that

the basic division among Poles then was between those who accepted a reality

without a free Poland and those contemplating armed opposition, and that this

dichotomy had been implicit since the partition era of the late eighteenth cen-

tury when Poland was obliterated.

2

Th

e Poles had a famous precedent for the later legion movement in the anti-

Russian Kościuszko Rising of 1794 (which sought to oppose the fi nal annihilating

partition) and the immediately following Napoleonic era during which several

thousand Poles formed legions and joined the Corsican’s ranks—playing a distin-

guished, albeit minor, role in several of Napoleon’s military exploits. Of course,

Napoleon was defeated, and Polish eff orts tied to him suff ered accordingly. Th

e

military heroics of the Napoleonic years, along with the vain attempts to resist

the partitions associated with Kościuszko, and even the bloody and bitter failure of

1

Th

is chapter is, in part, a radically modifi ed version of my essay “Th

e Militarization of the Dis-

course of Polish Politics and the Legion Movement of the First World War,” in David Stefancic, ed.,

Armies in Exile (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 71–101.

2

See Tomasz Nałęcz, Irredenta polska (Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza, 1992), 10ff .

2

Independence Day

the November Rising of 1830–31 composed a chapter of paradoxical signifi cance

to the Poles. Th

e military eff orts failed, despite great devotion and sacrifi ce, and

brought the country no gain and much loss. However, since this generation of

martial bravado coincided with or immediately preceded the Polish Romantic

movement, with its exaltation of patriotic devotion, the result was the creation of

a cult of Polish patriotism that sanctifi ed such sacrifi ces. Th

e military exploits of

1794–1831 were quickly mythologized into a defi ning component of a national

tradition. Th

e fact that the Polish national anthem is essentially a song of the

legion movement of the Napoleonic era is only the best known refl ection of this.

It associates national liberation with legions, and equates patriotism with military

volunteerism.

3

“As history teaches,” notes a contemporary historian, “it is not dif-

fi cult to raise cavalry in Poland.”

4

Th

e Romantic tradition, in which things military bulked so large, produced no

solution to Poland’s dilemma and, in the course of the nineteenth century, was

abandoned. After the abortive risings in 1846, the seeming ineffi

cacy of the wide-

spread revolutionary eff orts of 1848, and especially following the failure of the

1863–64 January Insurrection against Russia, Polish political speculation came to

regard martial shibboleths as inappropriate if not suicidal. Th

e gradual integration

of Polish lands into the partitioning states, the revolutionary transformation of

Polish society with the rise of industry, the end of serfdom, the rapid growth of

urbanization, and the emergence of clamorous nationalisms among the minority

populations of the pre-partition Polish Commonwealth, all combined to make the

Romantic military tradition appear irrelevant to Polish realities. Whereas images

and motifs of Polish martial eff orts remained in the national memory, they had

become the stuff of lore and sentiment, not the basis for thought about Polish pos-

sibilities. In their stead, we see more practical programs, eschewing armed struggle,

or even politics altogether, in favor of prosaic socioeconomic improvement: what is

known as the “organic work” movement—a Polish version of positivism, a kind of

preservation of the national energy in the face of challenges. Th

is “Realism” specifi -

cally rejected the military-insurrectionary tradition as a pre-modern distraction.

However, late in the nineteenth century we may note a transformation: the mili-

tarization of the discourse of Polish politics.

5

Gradually, Polish political thought

began to adopt a number of characteristics of which the following are particularly

noteworthy: an emphasis on the possibility of armed action which, in turn, refl ected

the increasing conviction that war was likely in Europe and the Poles must antici-

pate its consequences; a reconsideration of the January Insurrection, not as a

3

Th

e “legion myth” in Polish political and literary discourse begins with the national anthem; see

Jacek Kolbuszewski, “Rola literatury w kształtowaniu polskich mitów politycznych XIX i XX wieku,”

in Wojciech Wrzesiński, ed., Polskie mity polityczne XIX i XX wieku ( Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1994), 54

n. 62.

4

Witold Dworzyński, Wieniawa: Poeta, żołnierz, dyplomata (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa szkolne i

pedagogiczne, 1993), 91.

5

I have argued for this terminology in “Th

e Militarization of the Discourse.” Stanisław Czerep claims

that the fi rst re-appearance of the military-insurrectionist motif in Polish politics after the failed Janu-

ary Rising was in the 1886 work by Zygmunt Miłkowski, Rzecz o obronie czynnej i skarbie narodowym;

see Stanislaw Czerep’s II Brygada Legionów Polskich (Warsaw: Bellona, 1991), 11.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

3

national disaster but as a source for practical lessons in mass mobilization and mili-

tary tactics; and a conscious eff ort to fi nd a solution to the disintegrating eff ect of

modern political programs whose class basis stressed themes that split Poles along

socioeconomic lines.

6

Th

ese changes in theme and emphasis refl ected—and were stimulated by—the

larger changes in Polish culture, the late-nineteenth-century’s “neo-Romanticism,”

including the renewed emphasis on Poland’s martial glories. Th

e latter can be seen

in everything from the battle canvases of Jan Matejko— Batory at Psków, Prussian

Homage, Kościuszko’s Oath —to Wojciech Kossak, Józef Chełmoński, Jan Styka, and

the mystical Jan Grottger. In belles-lettres , positivism was in decline, being eclipsed

by the derring-do of the Sienkiewicz “Trilogy,” the stories of Wacław Gąsiorowski,

the defi ant chant-like Rota of Maria Konopnicka, and the revival of interest in the

poet Juliusz Słowacki. Th

ere were also manifestations of popular culture, such as

the widespread circulation of the “Polish Catechism” which, in childish language,

encouraged Polish youth to regard sacrifi ce and death in the Polish cause as enno-

bling. Even in historiography, the “optimistic” Warsaw school of Polish historical

analysis emerged in opposition to the Kraków school’s critical pessimism.

Inextricably associated with the military tradition is the martyrological under-

standing of Polish history: Poland as victim of the cruelty of history and Polish

patriots as sacrifi cial suff erers. Poland became a perfect lost cause, and its propo-

nents martyrs. Th

is conception is best illustrated by the canvases of Jacek Malczewski

with his many representations of Polish soldiers juxtaposed with religious symbol-

ism.

7

In one canvas, historic fi gures and symbols in Polish history are drawn into a

consuming vortex. Th

e military tradition thus was to be understood as a legion of

martyrs: always appearing, always suff ering defeat, yet reappearing once again. Th

e

solution to this pathos is a providential fi gure that will restore Poland to its rightful

place by ending the tragic circle of sacrifi ce. Th

is hero legend introduces an ele-

ment of charisma into the lexicon of Polish politics: a fi gure that will transcend the

present and represent tradition, a messianic politics that Tadeusz Biernat refers to

as “mythic sacralization” [sakralizacja mityczna].

8

Th

rough legend, paraphrasing

Biernat, that fi gure is rendered into concrete form, “personalized.” In the form of

political leadership, it is sacralized, separating it from reality which, by comparison,

is “profane.”

9

Particularly signifi cant is the commemoration movement in which great fi gures

and events in Polish history served as moments of national celebration and solidarity.

10

Of these perhaps the most signifi cant is the appearance of the Kościuszko cult,

6

Roman Wapiński, Pokolenia Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej (Wroclaw: Ossolineum, 1991), 101.

7

An example is “Nike Legionów,” which Małczewski painted in 1916. It portrays a Legionnaire

dead at the feet of Nike whose wings appear to resemble those of the Polish eagle. Her expression is

benefi cent. Th

is work hangs in the National Museum [Muzeum narodowe] in Kraków. Nike is the

goddess of victory, and death in the Polish cause is portrayed as triumph.

8

Th

e charismatic element in Polish politics is discussed in Tadeusz Biernat, Józef Piłsudski–Lech

Wałęsa: Paradoks charyzmaycznego przywodztwa . (Toruń: Adam Marszałek, 2000), 103 et passim.

9

Ibid. , 119.

10

A valuable discussion of this theme is Patrice M. Dabrowski, Commemorations and the Shaping

of Modern Poland (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004).

4

Independence Day

which many regarded as a symbol of the very notion of armed insurrection, a kind

of insurrectionary talisman, which began to appear in the late nineteenth century.

Kościuszko, whose military exploits were closely associated with a radical demo-

cratic program, was an ideal symbol of a new—or rather re-emergent—political

tradition which combines the mobilization of the masses and the emphasis on

armed action. In other words, Kościuszko became the perfect symbol for a new

military politics, a charismatic fi gure.

J Ó Z E F P I Ł S U D S K I A N D T H E M I L I TA R I Z AT I O N

O F P O L I S H P O L I T I C S

For reasons both symbolic and practical, we may consider the evolution of the

career of Józef Piłsudski (1867–1935) in this context. Indeed, Piłsudski so epito-

mized the militarization of Polish politics in the era that it is tempting to regard

him as having caused the process rather than merely refl ecting it: he “personally

revived the insurrectionary myth.”

11

Piłsudski, one of the founders of the Polish

Socialist Party [ Polska Partia Socjalistyczna , PPS, spent his early life as a publicist,

labor agitator, and conspirator. However, in the early years of the twentieth cen-

tury, he began a transformation into an essentially military fi gure, stressing organ-

ization and careful preparation for what were insurrectionary goals. With this shift

from underground socialist to military politics, Piłsudski perforce adopted a diff er-

ent set of referents in his political writings. Because of the centrality of the gentry

[ szlachta ] to the Polish military tradition—Piłsudski himself was a nobleman—his

evocation of Poland’s military past increasingly dropped the theme of class antago-

nism characteristic of socialist discourse, and emphasized supra-class, all-national

goals. He essentially appropriated the gentry tradition of acting for the nation,

along with its martial features. Th

e military replaced the working classes as the

engine of history, the battle replaced the strike, the trained offi

cer the conspirator,

and eventually the Polish legions replaced the Polish Socialist Party as the fulcrum

to reassert Poland’s case for independence.

12

Piłsudski became fascinated with military problems, particularly the January

Rising, which he studied intensively and to which he devoted a number of works.

He regarded the insurgents of 1863 as the “last soldiers of Poland,” whose sacrifi ce

and devotion, in impossible circumstances, he regarded as the ideal model for the

Polish army.

13

By his own words, Piłsudski became a self-taught soldier. Th

at he

11

Andrew A. Michta credits Piłsudski’s “military vision” with the very creation of a free Poland in

1918; see his Th

e Soldier-Citizen: Th

e Politics of the Polish Army after Communism (New York: Palgrave

Macmillan, 1997), 24–5.

12

Piłsudski in fact reverted to his origins in this transformation. He was the scion of a gentry family

deeply involved in the insurrectionary tradition. His youthful socialism substituted the proletariat for

the gentry, and the strike for the battle. By the end of the nineteenth century Piłsudski essentially

reverted to the traditional nomenclature.

13

See Piłsudski’s order to the army on January 21st, 1919 in Z. Zygmuntowicz, ed., Józef Piłsudski

o sobie (Warsaw-Lwów: Panteon Polski, [1929] 1989), 107.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

5

increasingly viewed Polish politics in military terms is clear, but why he did so

requires closer consideration.

Piłsudski had always been sensitive to the divisive nature of socialism, which

pitted the Polish proletariat against other classes. Th

e eff ort, by the so-called patri-

otic wing of the socialist movement to which Piłsudski belonged, to combine

national independence as a co-equal goal with socialist transformation was ideo-

logically awkward—a fact underscored by their more logically consistent rivals on

the Marxist Left. Hence, Piłsudski was long in search of a solution to his dilemma,

something that would rally rather than divide Polish ranks whilst maintaining a

vigorous attack against tsarist oppression, economic and otherwise. Th

is he found

in a military discourse rooted in re-application of the martial-insurrectionary tradi-

tion. Th

is would not so much solve the class struggle as transcend it, or at least

ignore it, by postponing it to a later issue after national independence had been

achieved.

Piłsudski made minimal changes in the structure of his program: a tightly knit

conspiratorial band became a disciplined military cadre, and the revolutionaries’

combat against tsarist gendarmerie became the soldier’s tactical exercise; but what

most remained the same was the leadership structure: hierarchy, loyalty, and discre-

tionary authority in the hands of the leader—merely transformed from party

chairman to commander. Th

e soldier was to be an example of sacrifi ce for Poland,

just as the earlier Piłsudski had regarded socialists as “a group of apostles” bearing

witness to a larger good.

14

Religious references in the service of political programs

had a long tradition in Poland, and would later become intertwined with the cult

of Piłsudski and his devotees.

15

Piłsudski reifi ed a larger reality of Polish life that was essentially a reconsidera-

tion of the effi

cacy of military struggle and a reconsideration of the essential value

of armed action. Th

e former was prompted by the widespread conviction that war

was imminent in Europe; the latter by the re-emergence of a new generation of

Poles, impatient with the prosaic passivity of organic work and no longer crushed

by the realization of the sacrifi ces implied in armed action—a generation that had

forgotten the depression of post-1864 but retained the nostalgic aff ection for the

traditions of an earlier age.

16

Th

ose who reached maturity in the fi rst decade of the

twentieth century constituted what Roman Wapiński has called the “turning-point

generation.”

17

14

Andrzej Chwałba , Sacrum i rewolucja: Socjaliści polscy wobec praktyk i symboli religijnych

(1870–1918) (Kraków: Universitas, 1992), 128–30.

15

Regarding the combining of independence politics and religious symbol and tradition, see Jan

Prokop, “Polak cierpiący (z dziejów sterotypu),” in Maria Bobrownicka, ed., Mity narodowe w literatu-

rach słowiańskich (Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 1992), 83. Th

ere is a lengthy discussion of the

Piłsudski “cult” tracing its origins to World War I in Heidi Hein-Kircher, Kult Piłsudskiego i jego zna-

czenie dla państwa polskiego 1926–1939 (Warsaw: Neriton, 2008), 11–24.

16

Th

is generational element and its relationship to the January Rising are noted in Stanislaw Jan

Rostworowski’s introductory remarks to Nie tylko Pierwsza Brygada , 3 vols. (Warsaw: P. W. Egross,

1993), I, 9.

17

Wapiński, Pokolenia Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej , 179.

6

Independence Day

Th

e new cultural and political motifs also refl ected the democratization of Polish

politics in the late nineteenth century, resting on the emancipation of the serfs and

their gradual evolution into conscious citizens, rapid industrialization and urban-

ization, an increasing politically conscious proletariat, and even a quickening pace

amongst the notoriously inert peasantry.

18

Th

is fundamental transformation of

Polish realities brought potentially new forces—the masses—into Polish post-1864

politics, which made new strategies not only possible but necessary. Th

e response

was a movement among the intelligentsia—largely of gentry origin—to choose a

martial option to express their political hopes: so-called “irredentism.” It is signifi -

cant that the Polish legions of World War I were reckoned “the most intelligentsia

army in the world.”

19

It is not an exaggeration to say that the offi

cer corps of the

future Polish army was essentially the gentry-intelligentsia playing soldier.

20

Th

e increasing militarization of Polish politics eff ected far more than the irreden-

tists of Piłsudskiite camp, but as well was visible amongst the nationalist Right—the

intellectual heirs of Realism—the so-called endecja (a term derived from the fi rst let-

ters of its Polish name Narodowa Demokracja ). Moreover, military eff orts, however

broadly defi ned, were characteristic of Polish politics worldwide. Indeed, the fact

that, by World War I, virtually all Polish factions tried to create some military force,

refl ects the degree to which the notion of military formations as political means had

spread throughout Polish thought in the preceding decades. Memoir literature rep-

resenting all political views notes the extraordinary appeal of military symbols,

motifs, and lore among the Polish youth at the turn of the twentieth century.

21

Th

e Russo-Japanese war of 1904–05, and the revolution within the Russian

Empire, including Russian Poland, furnished both the opportunity and the neces-

sity for Piłsudski to transform himself from revolutionary socialist to military com-

mander. In a well-known episode, Piłsudski traveled to Japan to try and convince

the Imperial General Staff to create, from amongst Russian POWs of Polish nation-

ality, a military force—which Piłsudski referred to specifi cally as a “legion”—to be

used against Russia.

22

Th

is was the fi rst time that he attempted to address the

“Polish Question” in essentially military terms.

23

18

Michał Śliwa, Polska myśl polityczna w I połowie XX wieku (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1993), 56ff .

19

Th

is is a problematical translation of the Polish “najinteligentniejsza armia świata”; see

Dworzyński, Wieniawa , 38.

20

Th

e offi

cer corps of inter-war Poland were overwhelmingly drawn from the intelligentsia of

gentry origin: see M. B. B. Biskupski, “Th

e Military Elite of the Polish Second Republic, 1918–1945:

A Historiographical Survey,” War & Society , 14(2) (October, 1996), 53ff . We should note Rothschild’s

reference to the legionnaires being sociologically “uniformed members of the intelligentsia”; see Joseph

Rothschild, Piłsudski’s Coup d’Etat (New York: Columbia University Press, 1966) , 101–2.

21

For example, Marian Żegota-Januszajtis, an opponent of Piłsudski on the political right, remembers

his youthful classmates in Częstochowa as extraordinarily martial; fi ve of his classmates eventually became

generals: see his Życie moje tak burzliwe . . . : Wspomnienia i dokumenty (Warsaw: BIS Press, 1993), 68.

22

Regarding this episode, see Janusz Wojtasik, Idea walki zbrojnej o niepodległość Polski 1864–1907

(Warsaw: MON, 1986), 162ff . A copy of the memorandum Piłsudski prepared for the Japanese

can be found in Wacław Jędrzejewicz, Sprawa “Wieczoru”: Józef Piłsudski a wojna rosyjsko-japońska,

1904–1905 (Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1974), 46.

23

Piłsudski’s career as a military historian—in which he showed considerable talent—began in

1904; see Andrzej Chwałba, Józef Piłsudski historyk wojskowości (Kraków: Universitas, 1993), 186 ; cf.

the remarks of Marceli Handelsman in “Józef Piłsudski jako historyk,” in Idea i czyn Józefa Piłsudskiego

(Warsaw: Bibljoteka dzieł naukowych, [1934] 1991), 205–19. Handelsman credits Piłsudski with

demonstrating an interest in “social-psychology,” which characterized his own writings.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

7

C R E AT I N G A P O L I S H A R M Y

Th

e failure of the revolution of 1905 to bring independence to Poland had a pro-

found eff ect on Piłsudski. His “Fighting Organization”—described as “the fi rst

attempt by Polish socialists to introduce armed force in their activities and

tactics”—was extraordinarily active in 1905–06, its more than 5,000 members car-

rying out hundreds of armed actions against the tsarist authorities.

24

All were in

vain: a revolutionary conspiracy, without some connection with international poli-

tics, could not restore Polish freedom. Piłsudski realized the political strategy he

had pursued for a generation was ultimately bootless.

25

We may regard the “Fight-

ing Organization,” in both form and conception, as a transition stage from revolu-

tionary to military politics.

26

After 1905, Piłsudski’s closest colleagues noted that in his thinking, his manner,

even his vocabulary, war and soldiering dominated. In 1906, the PPS split and

Piłsudski along with his adherents in the “Revolutionary Fraction” re-centered

their activities from Russian Poland to more indulgent Austrian Poland. Almost

immediately Piłsudski made contact with the Austrian authorities to gain their

approval for Polish paramilitary activities on Habsburg territory. Th

e foundations

for the legions were being laid.

27

In 1908 the secret Union of Armed Struggle

[Związek Walki Czynnej, or ZWC], the nucleus of a future Polish army, was estab-

lished.

28

Th

e staff of this Lilliputian force were the socialist agitators of a few years

earlier now re-clad in military tunics.

29

Th

e ZWC represented two trends in Piłsudski’s thought. Th

e fi rst was the evolu-

tion from the sporadic revolutionary actions characteristic of the PPS years in favor

of careful preparation for a larger armed action, a true insurrection.

30

Th

e second

was Piłsudski’s insistence that Polish political strategy must be all-national, and not

class or ideologically specifi c.

31

In 1912, Piłsudski created a central repository to

24

Zygmunt Zygmuntowicz, Józef Piłsudski we Lwowie (Lwów: Tow. Miłośników Przeszłości, 1934),

10 n. 3.

25

Th

e consequences of the failed revolution of 1905 on Piłsudski’s political strategy are well pre-

sented in Andrzej Friszke, O kształt niepodległej (Warsaw: Biblioteka Więzi, 1989), 44–8.

26

Regarding the combination of the revolutionary events of 1904–06 and the failure of his Japa-

nese mission on the formulation of Piłsudski’s thought in favor of preparation for a mass military

eff ort, see Mieczysław Wrzosek, “Problem zbrojnego powstania Polskiego w 1914 r. w świetle doku-

mentów austro-węgierskiego Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych,” in Studia i Materiały do Historii

Wojskowości , 32 (1990), 273–4.

27

Leon Wasilewski, Józef Piłsudski jakim go znałem (Warsaw: Rój, 1935), 90.

28

For the evolution from the ZWC to the legions see the memoir account in Bogusław Kunc, “Od

Związku Walki Czynnej do Strzełca (1909–1914),” Niepodległość , 3(1) (1930), 118ff .

29

Signifi cantly, the Organizacja Bojowa disbanded shortly after the creation of the ZWC which, in

large part, was the next stage in its evolution. Th

e ZWC represented a break with the socialist past,

which was characterized by anti-militarism; see

Stanisław Skwarczyński, “Twórca awangardy:

Dzialałność Józefa Piłsudskiego, 1893–1918,” Niepodległość, 7 (1962), 160 ; cf. Nałęcz, Irredenta pol-

ska , 132–9, 162.

30

Piłsudski’s movement away from support for continuous revolutionary activities in favor of

preparation, husbanding of resources, and training of cadres is succinctly traced in Władysław Pobóg-

Malinowski, “W ogniu rewolucji (1904–1908),” in Wacław Sieroszewski et al, eds., Idea i czyn Józefa

Piłsudskiego (Warsaw: Bibljoteka Dzieł Naukowych, 1934), 154–69 ; Nałęcz , Irredenta , 191–3.

31

See the arguments of Michał Sokolnicki, referenced in Nałęcz, Irredenta , 192–3; cf. Andrzej

Garlicki, “Spóry o niepodległość,” in Andrzej Garlicki, ed., Rok 1918: tradycje i oczekiwania (Warsaw:

8

Independence Day

collect money for Polish political eff orts. Signifi cantly, this “Polish Military Treas-

ury” ( Polski Skarb Wojskowy ) was essentially a fund for the preparation of large-

scale military eff orts.

32

By 1912, the ZWC had gained control over a number of legal so-called rifl emen’s

associations [ Związki Strzeleckie ], which had formed throughout Austrian Poland

as well as within Polish colonies in Western Europe, which, in aggregate, had about

7,500 members.

33

It was not the only organization of its type. Th

e Right had its

own paramilitary force, of which the Falcons—the international Polish gymnastics

and paramilitary society, where endecja views were dominant—had almost 7,000

adherents in about 150 detachments. Th

ese men were drilled by Poles who had

served in the Austrian army, like Zygmunt Zieliński and Józef Haller, both of

whom were later generals in Polish service.

34

Supposedly non-party, but also eff ec-

tively under endecja infl uence, were the peasant-based military formations called

the Bartosz’s Brigades [ Drużyny Bartoszowe] , which also numbered about 7,000

men in a few hundred scattered units.

35

Feliks Młynarski was the central fi gure in yet another series of paramilitary for-

mations associated with students, the Polish Rifl e Brigades [ Polskie Drużyny

Strzeleckie , or PDS]. Th

e PDS, which numbered perhaps 6,000 and had about

4,000 additional members in auxiliary scouting detachments, was independent of

both the Piłsudskiite ZWC coalition and the political Right. Indeed, virtually

every Polish political faction had its military wing, and voices that rejected at least

the potential effi

cacy of armed struggle were conspicuous by their absence. In 1912

a rudimentary eff ort to unite this complicated assortment of paramilitary organiza-

tions was the formation of the Temporary Coordinating Commission of Confed-

erated Independence Parties [ Komisja Tymczasowa Skonfederowanych Stronnictw

Niepodległościowych, or KTSSN], but the Falcons and the peasant units, essentially

the armed forces of the endecja, refused to cooperate, and the KTSSN never really

consolidated itself.

36

Nonetheless, the fact that Piłsudski was named commandant

Czytelnik, 1978), 14 . Similarly, the right also attempted to fi nd formulae to unite the national com-

munity for renewed struggle. National unity as the essential project of national democracy after 1895

is discussed in Władysław Koniczny, “Formowanie i umacnianie świadomości narodowej jako elemen-

tarne zadanie polityczne Narodowej Demokracji na przełomie XIX i XX wieku,” in Studia Historyczne ,

32(4) (1989), 545–58. It is characteristic of the evolution of Piłsudski’s thought that the ZWC,

though at fi rst dominated by members of the “Organizacja Bojowa,” quickly transformed itself by

opening its membership to non-socialist refl ection, the supra-factional basis of its goals; see Julian

Woyszwiłło, Józef Piłsudski: Życie, idee i czyny: 1867–1935 (Warsaw: Biblioteka Polska, 1937), 60–1 .

Nałęcz writes that the Piłsudskiites adopted “patriotic-national phraseology,” the “God–fatherland”

vocabulary; see Nałęcz, Irredenta , 327.

32

Wanda Kiędrzyńska, “Wpływy i zasoby Polskiego Skarbu Wojskowego,” Niepodległość , 13(3)

(1936), 383.

33

Th

is fi gure does not include members in Russian Poland; Czerep, II Brygada , 14.

34

Ibid., 12–13.

35

Ibid. , 13–14. Th

e name “Bartosz” recalls the peasant of that name who distinguished himself at

the famous Polish victory over the Russians at Racławice in 1794. Kościuszko ennobled Bartosz on the

fi eld for his service, thus symbolically including the peasantry in the forefront of the national cause.

36

Andrzej Garlicki’s, Geneza legionów: Zarys dziejów Komisji Tymczasowej Skonfederowanych Stron-

nictw Niepodległościowych (Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza, 1964) is the standard history of the organization

but, like all his works, it is marred by inveterate hostility to Piłsudski.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

9

of the combined KTSSN forces indicates clearly that he had become the dominant

fi gure in Polish military politics by the eve of the war.

37

When hostilities erupted in 1914, these several paramilitary units were com-

bined, including a ceremonial amalgamation of the Związki Strzelecki and the

Drużyny —into the “Polish Legions” which fought under the overall Austrian com-

mand. In order to bring the legions into being, the myriad and mutually antago-

nistic Polish political factions in Austrian Poland had to agree to a unifi ed

eff ort, which was epitomized by the creation of the Supreme National Committee

[ Naczelny Komitet Narodowy , or NKN]. Indeed, we may say that the legions created

Polish political unity, however short-lived.

38

Piłsudski, who had led the largest fac-

tion, was regarded as the commander presumptive of a future Polish army. Signifi -

cantly, Piłsudski created another, secret army, alongside the legions—the “Polish

Military Organization” [ Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, or POW]—which began

with a mere few hundred, but gave him another military card to play, and, in the

increasingly complex world of Polish politics, a surreptitious one under his exclu-

sive control.

On August 6th, 1914, the fi rst elements of the 1st Brigade of the Legions

marched out of Kraków in Galicia, crossed the partition frontier into Russian

Poland, and became the fi rst Polish army in generations to take the fi eld. August

6th, 1914 was the birth of the legions: the origin of the modern Polish army. It

would not be forgotten.

Piłsudski quickly became synonymous with the martial approach to the Polish

Question, a kind of re-animated General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski of Napoleonic

fame, picking up the fallen banner unfurled against the hated Muscovite.

39

An

eff ort was made to link Piłsudski with Kościuszko as the noble democrat leading

the common people, united and armed, thus re-knitting the continuity of the

irredentist tradition.

40

Janusz Pajewski argued that Piłsudski’s historical resonance

was even deeper: he was the “last nobleman in the history of Poland” again taking

the fi eld.

41

Th

e socialist politician, Ignacy Daszyński, grasped this early in the war

when he noted that:

the sympathy of the Polish masses for Piłsudski grew more and more. He became a

national hero far above all other Polish politicians of whatever camp, and his renown

obscured the names of all other Poles.

Piłsudski’s popularity derived from the appropriateness of this metaphor at a cer-

tain moment in Polish history. He remarked, quite dispassionately, in late 1915:

37

Nałęcz, Irredenta , 239.

38

Józef Buszko, “Sytuacja polityczna w Galicji (1914–1918),” in Michał Pułaski, ed., W 70-lecie

odzyskania niepodległości przez Polskę, 1918–1988 (Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 1991), 51–2.

39

Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, 1755–1818, fought with distinction in the Kościuszko Rising and later

became famous as the organizer of the Polish legions who fought with Napoleon. His name is promi-

nently featured in the Polish national anthem.

40

As Wieniawa-Długoszowski remarked, “the Commandant [Piłsudski] is the personifi cation of

the Kościuszko tradition”; see Roman Loth, ed., Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski, Wymarsz i inne

wspomnienia (Warsaw: Biblioteka Więzi, 1992), 88.

41

Quoted in Biernat, Paradoks , 158.

10

Independence Day

“I shall be the model of a patriot and the spiritual leader of the nation.”

42

In an

important letter of 1908, Piłsudski summarized his political credo: “I want to

win.”

43

Piłsudski was always impatient with Poland’s fascination with defeat and

sacrifi ce, which he wanted to replace by confi dence. Piłsudski’s brooding over the

damage done to the Polish psyche by long years of subjugation had as its antidote

a new tradition: he would be the providential fi gure who would furnish it the

symbol of victory.

44

Writing in 1985, Piotr Wierzbicki noted that Piłsudski was

the “last Pole of whom it might be said he won all his battles.” He became the

model of Poland triumphant.

45

Here we see Piłsudski as the fulfi llment of the writ-

ings of the neo-Romantic “Young Poland” movement—Piłsudski was the “charis-

matic leader.”

46

As Nałęcz aptly phrased it, “all of Young Poland prepared the basis

under the myth of the Commandant.

47

Piłsudski was profi ting from the “messianic

myth” in Polish Romantic thought. He was the salvational personage.

48

Th

e legions never exceeded 25–30,000 men. However, their exploits gave them

iconic status to Poles both during the war and later during the years of independ-

ence. What the legions were is far less important than what they symbolized. Th

e

legions were in essence a specifi c response to Poland’s historic dilemma and a para-

digm for the future Polish army and, indeed, state. Th

ey were, or were purported

to be, a founding myth for the creation of modern Poland. Th

ey were part of the

“mythic sacrilization” of Polish politics.

49

Th

e legions had a brief career. In the fi rst two years of the war they fought a

number of successful actions against the Russians and became famous for their

bravado and military eff ectiveness. Th

ey suff ered stupendous casualties. Th

e fi rst

action of the legions in Russian Poland confronted little resistance and resulted in

the capture of Kielce. Th

ey later participated in the Austrian thrust toward War-

saw, which met with a reverse and they were forced to withdraw to Kraków under

very diffi

cult conditions in the fall of the year. Th

e largest battle of 1914 was that

of Łowczówek near Nowy Sącz in December, covering competently the Austrian

withdrawal. Th

ey suff ered 50 percent casualties in a series of bloody encounters but

won considerable praise for their eff orts at screening Austrian maneuvers.

42

Quoted in Loth, Wymarsz, 89.

43

Biernat quotes from a September 1908 letter from Piłsudski to Feliks Perl., in Paradoks , 84.

44

Włodzimierz Suleja, “Myśl polityczna Piłsudczykow a tworczość Juliusza Kadena-Bandrowskiego,” in

Henryk Zieliński, ed., W kręgu tworców myśli politycznej (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1983), 286–7 285. Th

is

made Piłsudski a fascinating exception to what Miciński described as the Poles’ “eternal loyalty to the lost

cause.” See Miciński quoted in Rett R. Ludwikowski, Continuity and Change in Poland: Conservatism in

Polish Political Th

ought (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University Press, 1991), 177 . Piłsudski represented a tradi-

tion not of the defeated insurrection over which one broods, but an incipient insurrection that is approached

with hope. Cf. Waldemar Paruch, “Kreowanie legendy Józefa Piłsudskiego w Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej—

wybrane aspekty,” in Marek Jabłonowski and Elżbieta Kossewska, eds., Piłsudski na łamach i w opiniach prasy

polskiej, 1918–1989 (Warsaw: Instytut Dziennikarstwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2005), 59.

45

Piotr Wierzbicki, Myśli staroświeckiego Polaka

(London: Puls, 1985), 83.

An underground

Piłsudskiite journal in occupied Warsaw commented in 1943: “In the last era we Poles have had only

one victorious leader. It was Józef Piłsudski.” See Marek Gałęzowski, Wierni Polsce; Ludzie konspiracji

piłsudczykowskiej 1939–1947 (Warsaw: LTW: 2005), Vol. II: piłsudczykowska w kraju 1940–1946.

(Warsaw: LTW, 2007), 568–9. By contrast, Micewski labels all Piłsudski’s political actions “fi ascos”;

see Andrzej Micewski, W cieniu Marszałka Piłsudskiego (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1969) , 33.

46

Biernat, Paradoks , 114.

47

Nałęcz, Irredenta , 225.

48

Biernat, Paradoks , 103.

49

Nałęcz, Irredenta , 260.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

11

In 1915, the legions participated in the large Austro-German off ensive on Warsaw.

On May 16th, they fought an action at Konary against far superior Russian forces,

and another celebrated action at Kostiuchnówka in Wołyń, where 5,000 legion-

naires defended an exposed position against 13,000 Russians. Th

is one encounter

resulted in 40 percent casualties but allowed the Austrians to escape. It was the

most famous legion battle. Later actions included signifi cant battles at Krechowce

and Rarańcza. All in all, the legions gained a reputation as soldiers unusually able

to hold diffi

cult positions, full of courage in off ensive actions, and suicidally self-

sacrifi cing.

However, Piłsudski became increasingly frustrated at what he regarded as

Vienna’s unwillingness to respond to Polish political aims in return for military

eff orts. As a result, he opposed the numerical expansion of the legions without

concrete political concessions, and decided to resign in protest. His Polish political

opponents—notably Władysław Sikorski—who later led Poland’s government in

exile during World War II—held a rather more optimistic view of Polish capacities

to leverage concessions from the Central Powers. Th

is factional fi ghting paralyzed

the legions.

50

By 1916, the German-Austrian victories forced the Russians out of much of

historic Poland, and the Central Powers proclaimed the existence of a restored

Polish Kingdom (the Two Emperors’ Manifesto of November 5th, 1916). Although

Piłsudski emerged as the most signifi cant fi gure in the Polish pseudo-government

created by the Central Powers, this did not result in a resuscitation of the legions.

Again Piłsudski concluded that no signifi cant gains were to be had from Polish

manpower contributions.

51

In the summer of 1917, Piłsudski was arrested in War-

saw by the Germans, and incarcerated at Magdeburg. Th

e bulk of the legionnaires,

at his orders, refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Central Powers.

52

Th

ey

spent the rest of the war interned or dispersed to other fronts. Th

is was the sudden

end to the three-year history of the legion movement.

From their inception, the legions were an elite formation, deemed by more than

one analyst as “the most thoroughly educated and sophisticated army in the history

of warfare”

53

: 40 percent were members of the intelligentsia.

54

Th

e First Brigade

especially was noted for the high percentage in the ranks.

55

Youth spent in immer-

sion in Polish neo-Romanticism, especially the swashbuckling novels of Sienkie-

wicz—“our generation was raised on reading Sienkiewicz”

56

—gave the legionnaires

50

Włodzimierz Suleja, “Spór o kształt aktywizmu: Piłsudski a Sikorski w latach I wojny światowej,”

in Zieliński, ed., W kręgu , 141–99.

51

Signifi cantly, one of his central goals was to transform the legions into a Polish army, but this

he thought impossible in the circumstances; see Władysław Baranowski, Rozmowy z Piłsudskim,

1916–1931 (Warsaw: Zebra, [1938] 1990), 25.

52

Regarding the circumstances, see Stanisław Biegański, “Zaplecze przysięgi legionów w 1917

roku,” Niepodległość , 9 (1974), 218–28.

53

Th

e original passage is: “najgruntowniej i najbardziej światowo wykstałcona armia w całej historii

wojskowości”; see

Mariusz Urbanek,

Wieniawa: Szwoleżer na pegazie (Wrocław: Wydawnictwo

Dolnośląskie, 1991), 35.

54

Adam Roliński, ed. A gdy na wojenkę szli Ojczyźnie służyć: Pieśni i piosenki żołnierskie z lat

1914–1918 (Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 1989), 9.

55

Dworzyński, Wieniawa. 38.

56

Kornel Krzeczunowicz, Ostatnia kampania konna (London: Veritas, 1971), 23.

12

Independence Day

a remarkable cultural similarity.

57

It is noteworthy that many Polish legionnaires of

the 1914–18 era chose as their noms de guerre characters from Sienkiewicz’s nov-

els.

58

Th

e novelist “taught [a generation] how to love the Fatherland.”

59

Kornel

Krzeczunowicz, a cavalry offi

cer, remarked that it was the Sienkiewiczian neo-

Romanticism that united his contemporaries:

Our generation, all the offi

cers from the commander of the squadron on down to the

last enlisted man capable of reading, was raised on reading Sienkiewicz’s Trilogy. . . . It

is no wonder that the language of Sienkiewicz was the common language of these

units previously strange to one another.

60

Franciszek Skibiński and Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski both became cavalry

generals in the army of the Second Republic. During World War I, Wieniawa, a

Piłsudskiite, served in the legions under Austrian command; Skibiński, politically

to the Right, fought in Russian ranks. Both recollected teenage years molded by

patriotic military tales: “the models to emulate were [Sienkiewicz’s heroes] Skrze-

tuski, Kmicić, Wołodyjowski . . . because from my earliest youth we were nourished

by such patriotic and battlefi eld literature,” wrote Skibiński in words virtually

repeating Wieniawa’s own reminiscences.

61

Th

e political creeds were diff erent, but

both were products of the same martial ethos. In their hero-cult and military devotion,

the legions were the rebirth of the Romantic tradition.

62

Educated and literate, the legionnaires were remarkable for their tendency to

create song, poem, and story about their exploits, acting, as it were, as their own

press department. Th

e eccentric artist Jacek Malczewski’s drawings of dying legion-

naires with angels hovering nearby, or legionnaires dining with Christ, give some

idea of the apotheosization of the legions.

63

Bolesław Leśmian’s 1916 poem “Th

e

Legend of the Polish Soldier” is perhaps the ultimate example: a Polish soldier

meets St. George, and we witness the “the uncertainty of the Saint in his eff ort to

diff erentiate the soldier’s blood from that of Christ”—a clear evocation of the

“Christ among nations” trope of Polish lore.

64

Th

e legions should not be understood solely as a military caste. Quite the con-

trary, we may profi t from a remark by Joseph Rothschild some years ago that lik-

ened the legionnaires in social pedigree more to the gentry-intelligentsia than to

57

Many legionnaires adopted pseudonyms drawn from Sienkiewicz’s oeuvre. See Jacek M. Majchrowski,

Ulubieniec cezara: Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski: Zarys biografi i (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1990), 64–5 ;

cf. Piotr Stawecki, Słownik biografi czny generałów wojska polskiego, 1918–1939 (Warsaw: Wojskowy Instytut

Historyczny, 1994), 22–3, quoting Jacek Majchrowski’s characterization of legion senior offi

cers.

58

Majchrowski, Ulubieniec cezara , 64.

59

Ibid.

60

Krzeczunowicz, Ostatnia kampania konna , 23.

61

Skibiński’s remarks are in Franciszek Skibiński, Ułańska młodość, 1917–1939 (Warsaw: MON,

1989), 7 ; for Wieniawa’s parallel recollections, see Loth, Wymarsz, 70–1. Th

e three names mentioned

are all characters in the Trilogy.

62

Jacek Kolbuszewski, “Romantyczne sny o wolności. Od Adama Mickiewicza do Stefana

Żeromskiego,” in Wojciech Wrzesiński, Do niepodległości: 1918, 1944/45, 1989: Wizje-drogi-spełnienie

(Warsaw: Wydawnictwo sejmowe, 1998), 258–60.

63

See e.g. Józef Szaniawski , Marszałek Piłsudski w obronie Polski i Europy (Warsaw: Ex Libris, 2008), 126–7.

64

Andrzej Z. Makowski, “Literatura wobec Niepodległości,” in Salon Niepodległości [no editor]

(Warsaw: PWN, 2008), 107.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

13

hereditary praetorians.

65

Here we may descry the strong traditional element

represented by the legions. It was the age-old function of the gentry to defi ne

themselves as both defending Poland against foreign invasion and epitomizing vir-

tues of the Polish past: representatives of all Poland in symbol. It combined the

Romantic and Noble tradition.

66

Szalai has argued that a characteristic function of an elite is the “setting of imi-

table patters of social behavior.”

67

Th

e transmission of these “imitable” values is

accomplished “fi rst and foremost” via “the media.”

68

Given the circumstances of

the time the media is represented by literary popularizations of legionnaire exploits,

circulation of artistic renderings and postcards of legionnaires, and, most strik-

ingly, the legionnaire repertoire of song which extended beyond military ranks to

a wide audience. Th

us the legions had a means of transmitting values via the media

characteristic of the era. According to Kowalczykowa, the legions:

had not only to fi ght, but to fulfi ll higher expectations—to become the model of cour-

age and bravery [bojowość]. Without that they would destroy the very sense of their

existence. . . . It must sink into everyone’s memory that this is a formation qualitatively

something apart, whose goal is not just to summon [Poles] to play a role in the parti-

tioning powers’ confl icts but for the struggle for independence of the Fatherland.

69

Th

ey were men “redeemed by blood,” whom Piłsudski deemed the “cadres of the

future Polish army.”

70

T H E KO Ś C I U S Z KO P I Ł S U D S K I S Y M B O L

Th

e legions appropriated the Kościuszko tradition or, better, shared his charisma.

He was not just a national hero but a multiform symbol. He was a nobleman who

championed the cause of the peasantry; a scion of northeastern Poland identifi ed

with the southwest, and hence not a regional fi gure; a Pole of mixed ethnic descent

(he was, at least partially, a Lithuanian and Belarusian) thus refl ecting the ethnic

heterogeneity of historic Poland; a soldier who encouraged the levée en masse and

broad participation in the national cause, hence a democratic fi gure. He was also

the selfl ess hero (above faction) to whom the nation entrusted complete authority,

believing in his noble spirit and disinterested patriotism.

65

See Joseph Rothschild, “Marshal Józef Piłsudski on State/Society Dialectics in Restored Interwar

Poland,” in Timothy Wiles, ed., Poland between the Wars: 1918–1939 (Bloomington: Indiana Univer-

sity, 1989), 30.

66

Biernat, Paradoks, 125. We may note the characterization of the legionnaires as “anachronistic,”

“post-noble, from the eastern borderlands.” Th

e same could be said about Piłsudski; see Andrzej

Micewski, Z geografii politycznej II Rzeczpospolitej: Szkice (Warsaw: Znak, 1966), 135 ; cf. Paruch,

“Kreowanie,” 64–5.

67

Erzebet Szalai, “System Change and the Conversion of Power in Hungary,” 1. Online at <http://

www.szociologia.hu/dynamic/RevSoc_1999_SzalaiE_System_change.pdf>.

68

Ibid.

69

Alina Kowalczykowa, Piłsudski i tradycja (Chotomów: Wydawnictwo Verba, 1991), 76.

70

Ibid.

14

Independence Day

Th

e legions had their Kościuszko in Piłsudski.

71

Piłsudski was quite conscious of

the appropriation of the Kościuszko myth for him. Legion songs—and they were

striking in their number—often spoke of Piłsudski as Kościuszko reborn, and

compared the two as national heroes.

72

Kościuszko tropes became Piłsudski tropes,

and graphic images displayed them in juxtaposition: “eff ective political market-

ing,” according to Andrzej Chwałba.

73

Th

e Piłsudski symbol should be regarded as sub-theme in the legion symbolism.

Piłsudski was well aware of certain requirement to posit himself as the leader of

Poland in 1914. He had to link himself to the Kościuszko tradition of insurrection,

epitomize military action and sacrifi ce, remove himself from any taint of factional-

ism, and suggest a providential historic mission for himself. All the while he had to

eschew personal aggrandizement. He had to be the essence of Polish Romanticism

reincarnated.

74

In the propaganda generated by the legions in 1914–16, much of it in the form

of song and poetry, Piłsudski lives only to symbolize Poland. He is modest, dis-

daining of ornament and decoration, oblivious to faction, a former socialist who

does not seek a socialist agenda—an ethnic Lithuanian from the mixed eastern

borderlands, who is associated with Galicia (here the comparison with Kościuszko

is perfect). He is the leader who is obeyed because he represents Poland tout court ,

not because he has achieved certain successes or occupies a certain position.

75

He

fulfi lls what Karol Modzelewski refers to as the “leadership syndrome” in Polish

political mythology.

76

In the legions, Piłsudski remarked, there are now no regional

diff erences, only Poles.

77

Th

e legions were soldiers without a fatherland; hence, in

Piłsudski, they had the personifi cation of an ideal.

78

Although utterly without military training, Piłsudski was foremost a political

soldier, a symbol of the armed patriotic defense of the Polish tradition. As Carlo

Sforza noted, Piłsudski was an anachronism: never a revolutionary but a son of the

71

See the remarks entitled “Kościuszko-Piłsudski” in Krzysztof Stępnik, Legenda Legionów (Lublin:

Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej, 1995), 154–60. Wieniawa-Długoszowski put it simply: “Th

e

Commandant [Piłsudski] is the incarnation of the Kościuszko tradition,” see Loth, Wymarsz , 88.

72

Th

e Germans remarked that the legionnaires sang continuously; that it was part of their charac-

teristic features; see Loth, Wymarsz, 177 .

73

“Gdyby Piłsudskiego nie było, należałoby go wymyślić,” Gazeta Krakowska , November 11,

2008.

74

We should note, however, that Kościuszko and Piłsudski had somewhat diff erent geopolitical

visions. Piłsudski dreamed of a federal version of the old multinational Jagiellonian state; Kościuszko

also wanted the pre-partition territory, but was a proponent of polonization. In this particular, at least,

he approached the endecja paradigm; see Andrzej Walicki, Th

e Enlightenment and the Birth of Modern

Nationhood: Polish Political Th

ought from Noble Republicanism to Tadeusz Kościuszko (Notre Dame, IN:

University of Notre Dame Press: 1989), 125–6.

75

Here we may note the well-known songs of tribute to Piłsudski sung by the legionnaires: “Jedzie,

jedzie na kasztance,” or “Pieśń o Józefi e Piłsudskim,” “Komendancie,” or “Brygadier Piłsudski,” popu-

lar since the fi rst year of the war. For the text, see Roliński, A gdy na wojenkę, 311–19 and the invalu-

able analytic comments in ibid . 457–9.

76

Karol Modzelewski, quoted in Mariusz Urbanek , Piłsudski bis (Warsaw: Most, 1995) , 65.

77

Józef Piłsudski, Korespondencja, 1914–1917 (London: Instytut Józefa Piłsudskiego, 1984), 256.

78

Th

is is a paraphrase of the idea presented in Tomasz Nałęcz, “W służbie Rzeczypospolitej i w

dyspozycji Wodza (obóz legionowy od Oleandrów do zamachu majowego)” in Życie polityczne w Polsce

1918–1939 (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1985), 209.

Introduction: Myths and Symbols

15

Polish nobility.

79

He had taken up arms to rise above faction. His abandonment of

socialism was not an ideological transformation but a disdaining of political

sordidness for larger goals. By passing from socialist revolutionary to soldier-

commander Piłsudski had been transformed from the principal socialist of Poland,

to a supra-political fi gure replete with all the trappings of tradition.

Piłsudski became a legend in the poetry of the war era of multiform dimension.

In Makowski’s words, a legend that persisted throughout the inter-war period

among his devotees, culminating in Wierzyński’s 1936 poems “Wolność tragiczna,”

a mystical biography of Piłsudski in a series of verses that interpret his transcenden-

tal meaning for Poland.

80

Poet and ardent Piłsudskiite Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna

doubtless had her hero in mind when she beseeched her countrymen to “Learn, oh

my nation, our list of symbols.”

Piłsudski stepped down from the canvas of Matejko, his greatness announced by the

ringing of Zygmunt [the great bell of the Wawel] and the prophesy of Wernyhora,

[the reference is to a mythic fi gure in Wyspiański’s Wesele ] he is the Polish Prometheus,

the commander of the sleeping knights, the personifi cation of the dream of the sword,

the avenger and the giant.

81

Th

e simultaneous function of the legions as the petty gentry reborn and an ele-

ment for social equalization should not be seen as contradictory. As Aleksander

Gella pointed out some years ago, the notion of upward leveling of the population

had strong roots in the Polish political traditions, and creating gentry from the

lower orders was a well-established practice by the nineteenth century. Kowal-

czykowa refers to it as the “nobilitation of the workers.”

82

Th

is phenomenon was

aided by the impoverished status of much of the gentry, which was therefore not

socially distanced from the petty bourgeoisie, or even the prosperous farming

class.

After the war, many legionnaires moved freely in the literary and artistic milieux