Constructing Identity with Dreamstones: Megalithic Sites and Contemporary Nature

Spirituality

Author(s): Phillip Charles Lucas

Source:

Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Vol. 11, No. 1

(August 2007), pp. 31-60

University of California Press

Stable URL:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/nr.2007.11.1.31

.

Accessed: 10/12/2013 06:29

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

.

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Nova

Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

Constructing Identity

with Dreamstones

Megalithic Sites and Contemporary

Nature Spirituality

Phillip Charles Lucas

ABSTRACT:

For growing numbers of people, the postmodern

construction of identity includes the search for a spirituality that reconnects

them with the natural world and fosters activity that protects the ecosystem

and its many forms of life. Practitioners of this “nature spirituality”

construct their identities using a large toolkit of symbols, myths, histories,

rituals, sacred places, and beliefs. The megalithic sites of Western Europe

constitute one element of this toolkit. This paper considers the ways these

sites are interpreted and experienced in the nature-spirituality subculture

and how these interpretations and experiences help individuals construct

empowering identities that tie together their spiritual and ecological

commitments. This interpretive process is occurring outside the control of

governing elites, ecclesiastical authorities, or dominant religious

institutions. It is at root an exercise in both individual and communal

identity construction, a movement of resistance to a world system that has

lost its secure moorings in the natural order.

INTRODUCTION

One might say that the fundamental human project, after physical

survival, is the construction of individual and collective identity. Identity

construction is an ongoing, fluid process that gives personal and collective

Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 11, Issue 1, pages

31–61, ISSN 1092-6690 (print), 1541-8480 (electronic). © 2007 by The Regents of the

University of California. All rights reserved. Please direct all requests for permission

to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s

Rights and Permissions website, at http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintinfo.asp.

DOI: 10.1525/nr.2007.11.1.31

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 31

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

life meaning, purpose, and security. In the postmodern world, identity

construction has become a more conscious, self-reflexive process than

it was in modern and pre-modern times. Identity construction, in other

words, is now both a choice and an imperative, since the identities

conferred upon us by social institutions, religious communities, and

nations have proven to be both unstable and unsatisfactory for increas-

ing numbers of people—particularly in the Western industrialized

democracies. This state of affairs has partly to do with a profound ques-

tioning of religious and national meta-narratives, the great truth-stories

that families and social institutions tell their members to socialize them

into the dominant culture’s values and norms.

1

A significant aspect of identity construction involves religious and

spiritual orientations. These orientations tell us where we have come

from, what we are here to do, how we should live together with others,

what our relationship with divinity—however conceived—should be,

and where we are heading in the future. They also give us a conception

of our totality as human beings, the physical, emotional, mental, and

spiritual dimensions of human existence.

For growing numbers of people, the postmodern construction of

identity includes the search for a spirituality that both reconnects them

with the natural world and fosters activity that protects the ecosystem

and its many forms of life.

2

These persons desire, in Adrian Ivakhiv’s

words, “to be part of a broader societal imperative—a refusal of the dis-

enchanting consequences of secular, scientific-industrial modernity . . .

and an attempt to develop a culture of reenchantment, a new planetary

culture that would dwell in harmony with the spirit of the Earth.”

3

I use

“nature spirituality” as an umbrella term that covers the diverse array of

individuals, groups, tribes, and communities joined by ritual practices

that embrace the natural world as a locus of sacred beings and/or ener-

gies and by a desire to protect and live in harmony with the natural envi-

ronment. As Ivakhiv observes, proponents of nature spirituality

“understand the divine or sacred to be immanent within the natural

world, not transcendent and separate from it, and speak of the Earth

itself as being an embodiment, if not the embodiment, of divinity.”

4

Among the many groups and communities included under the nature

spirituality tent are modern Pagans, various Druidic orders, Wiccans,

goddess worshippers, the women’s spirituality movement, neo-shamans,

New Agers, eco-feminists, eco-pagans, the neo-tribal “Rainbow family,”

Hedge Witches,

5

earth mysteries enthusiasts, Heathens,

6

adherents of

Celtic spirituality, and Green Christians and Jews.

7

Practitioners of nature spirituality construct their individual and col-

lective identities using a large toolkit of symbols, myths, histories, ritu-

als, sacred places, and beliefs, many of which were censored and

suppressed by dominant institutions in the past.

8

This paper examines

one element of this toolkit, the megalithic sites of Western Europe.

Nova Religio

32

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 32

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

These stone monuments date back to the Neolithic Age, which began

around 4500

B

.

C

.

E

. in Western Europe and continued to about 2200

B

.

C

.

E

. The monuments include passage tombs, gallery graves, simple

dolmens (called quoits in Cornwall), stone circles (sometimes called

cromlechs), stone rows, and standing stones (also called menhirs) that are

found in the thousands throughout Western Europe and the British

Isles. Practitioners of nature spirituality ascribe a wide range of mean-

ings to megalithic sites and these meanings in turn inform how practi-

tioners use the sites to construct and enhance their spiritual identities.

The various agendas and worldviews operating at megalithic sites are

sometimes competing discourses, but this does not necessarily result in

antagonism or hostility between different visitors. Rather, these “het-

erotopias”

9

are spaces of heterogeneity, “bringing together meanings

from incommensurable cultural worlds.”

10

They are spaces of resist-

ance, pluralistic, ever-changing, lacking an accepted identity, and

“linked by centerless flows of information.”

11

An awareness of the plurality of “readings” of the sites allows us to

perceive the many levels or textures of interpretation that surround

these relics from prehistory.

12

Shorn of their superficial idiosyncrasies,

all of these readings have a common root: a desire to reconnect with a

sacred earth. Proponents of nature spirituality see megalithic sites as

places where they can find solace and guidance, and reclaim an earthly

sanctuary from the exploitative intentions of modern global capitalism.

Once reclaimed, the sites are used for various rituals and ceremonies all

designed to enhance awareness of, and communion with, the sacred

earth.

13

It is important to stress that these sites are not some kind of

ontologically determined sacred spaces, but rather parts of a larger

activity of identity/place creation. As Nikki Bado-Fralick observes,

“Space has no ontological status independent of its relation to human

activity.” The nature spirituality religious landscape is “fluid and ever-

shifting, replete with themes of ‘becoming’ and transformation. Space

may assume either sacred or mundane status at any given moment in the

ritual process, its boundaries shifting according to the perspectives and

activities of the participants.”

14

In this paper, therefore, I want to consider in some depth the ways

these sites are interpreted and experienced, and how these interpreta-

tions and experiences help members of the nature-spirituality subculture

construct empowering identities that tie together their spiritual and eco-

logical commitments. Since interpretations of megalithic sites must deal

with the past, it is appropriate to discuss first the ways individuals and com-

munities create a “usable past” and how ancient monuments provide a

tangible connection with favored versions of the past.

15

As Marco Portales

reminds us, “the past changes not so much because the returns aren’t all

in, but because the living insist . . . on reshaping the past according to our

lights and the age’s needs. Why this need to redefine, to look and rewrite

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

33

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 33

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

history anew? Because histories legitimize the past, not the past, but our

ways of looking at the pasts that we would enshrine.”

16

The individuals and groups who interpret megalithic sites often con-

struct a pedigree for these monuments that supports their present ide-

ological commitments and agendas.

17

As monuments, they serve as

symbolic emblems of the distant past. Because relatively little is known

about why these sites were constructed and how they were used, they can

be enlisted in the service of readings of the past that support identity

construction and spiritual experience in a re-enchanted world distinct

from secularized, scientific-industrial culture.

18

As places connected to

the sacred, however defined, they encourage followers of nature spiri-

tuality to reclaim a pre-Christian past, and to draw on the forces and

beings connected to a site in myth and tradition for spiritual empower-

ment in the present.

19

The sites thus provide us with a case study in how human beings con-

struct worlds of religious and spiritual meaning using emblems, symbols,

and representations of the past. This process of construction exempli-

fies Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann’s sedimentation theory, which

they formulated to explain “why humans invent traditions and yet seri-

ously hold that they stem from time immemorial.”

20

Put briefly, this

theory elaborates a process by which human experiences congeal as

recollection sediments. These sediments in turn become objective sign

systems that can be incorporated into “a larger body of tradition”

through iteration as poetry, spiritual allegory, and moral instruction. In

time, the sediments become part of cohesive religious systems and the

original processes by which they took shape are lost in the mists of time.

Therefore, other myths of origin can be invented for these signs systems

in ways that further the present commitments of religious communi-

ties/social institutions. A version of this process may be occurring with

the elaboration and spread of nature spirituality, both as a means of

enlisting symbols and sacred sites of the past to validate spiritual expe-

riences that fall outside mainstream religious practice, and to promote

an ethic of ecology in a time of environmental crisis.

21

Let us now turn to the different ways contemporary individuals

and groups are using the megalithic sites of Western Europe to con-

struct spiritual identities and to practice their various forms of nature

spirituality.

MEGALITHS AS SYMBOLIC TOUCHSTONES

WITH PAGAN ANCESTRAL TRADITIONS

As Gabriel Cooney has observed, “One of the key ways of sustaining

links with the past is to perform rituals in defined, special places.”

22

For

increasing numbers of Europeans and North Americans, megalithic

sites are tangible points of connection with idealized matriarchal,

Nova Religio

34

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 34

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

nature-friendly religions of the pre-Christian past. Modern Pagans, Neo-

Druids, Wiccans, and others have created myths of continuity with these

Pagan religions of Northern Europe. They speculate that megalithic

sites mark sacred places where their spiritual ancestors worshiped earth

goddesses and other nature deities, and practiced rituals that celebrated

seasonal cycles. Through repeated use, the sites are believed to have

built up a powerful spiritual atmosphere that enables easier access to

wise ancestral beings and nature spirits. As one respondent put it, “A

thick layer of spiritual usage lies over these sites already . . . We know that

a place may have been an ancient settlement or gravesite, and we can

use the ambience there to enhance our experience.”

23

Though most

modern Pagans are sophisticated enough to know that an “unbroken

transmission of ritual practices” from Neolithic times until now is

unlikely, they still visit megalithic monuments because they provide a

tangible symbolic connection to Pagan ancestors and their traditions.

24

The fact that very little is known about the worldviews and ritual sys-

tems of Neolithic peoples seems not to be an impediment. In some cases,

anthropological and archaeological research is used as a foundation for

informed speculation concerning prehistoric beliefs and practices; in

other cases, specific details about rituals performed at the sites is accessed

by means of psychometry or other visionary techniques. To cite one of

many possible examples of the latter, a famed psychometrist who visited

the Castlerigg stone circle in Cumbria reported a vision of a tall, bearded

figure clothed in a single white garment standing in the circle’s center.

Assisted by a group of priests, the figure performed a ceremony that

invoked a downflow of opalescent, rose-tinged sky energy; this energy

penetrated the earth, ensuring the land’s fertility for another planting

cycle. According to the vision, the stones making up the circle were

draped with flowing banners bearing arcane symbols. These visionary

reports are influential within the nature spirituality subculture (though

by no means universally accepted) and provide suggestive details for the

construction of present-day rites and beliefs. They also lend credence to

claims that megalithic sites were sacred centers for ancient Pagans.

25

Some sites have a more recent history that makes them attractive to

Wiccans and their fellow travelers. The Rollright Stones in Oxfordshire,

to cite one example, is associated with the coven of Gerald Gardner, an

important figure in the modern Witchcraft revival of the 1940s and

1950s. Gardner and his associates used the stone circle for ritual prac-

tice, and the site has become a much-visited venue for Pagan rites of pas-

sage, including handfastings,

26

the naming of children, initiatory rites,

and funerary memorials.

27

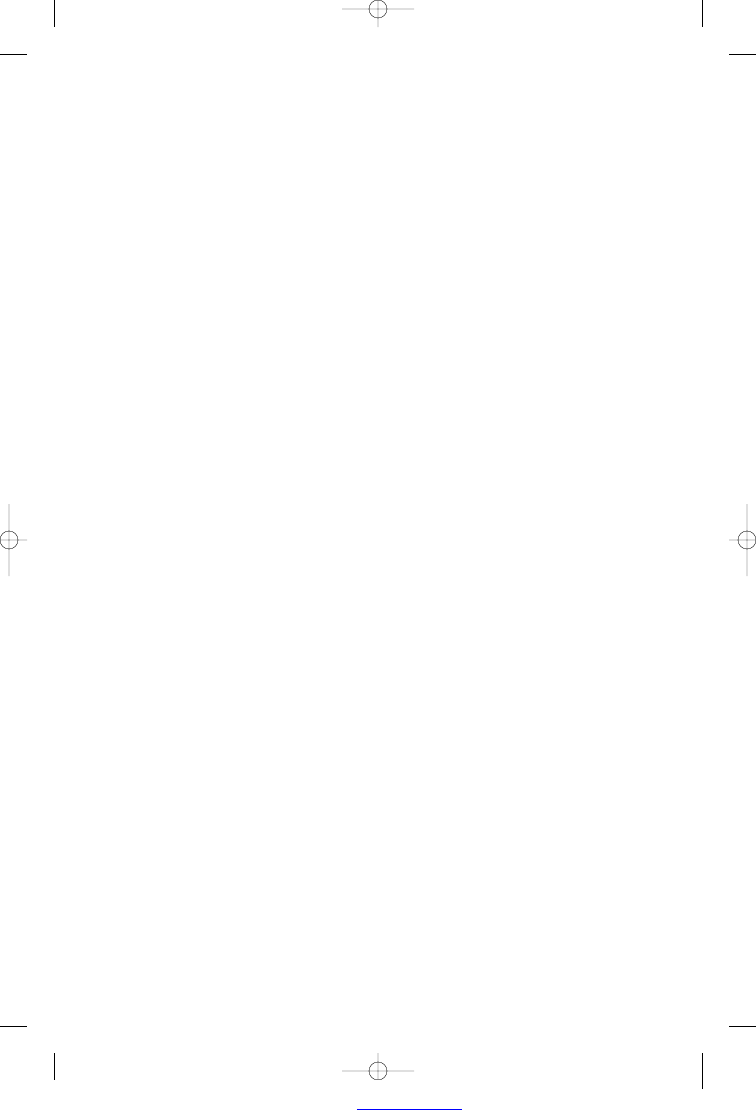

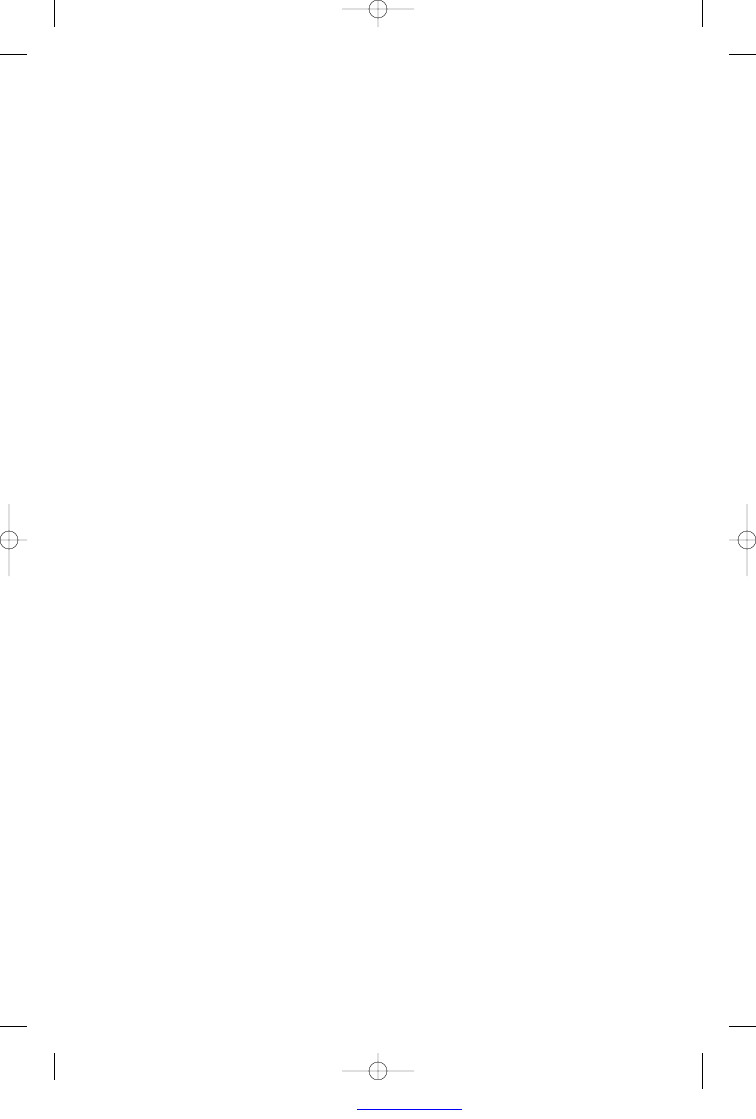

Another site, the Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb on the Welsh Isle of

Anglesey, is venerated by contemporary Druidic orders because the isle

was the last refuge of the Celtic Druids of Britain before their destruc-

tion by the Romans in 60

C

.

E

. Contemporary Druids leave offerings at

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

35

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 35

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

the site as a memorial to their spiritual ancestors, despite the lack of

solid evidence that the passage tomb was itself used by the Druids dur-

ing their final days.

Although modern day Druidism is rife with speculations and folklore

of questionable historical accuracy, the tradition’s emphasis on ancestral

spirits and spirits of place makes Druids frequent visitors to megalithic

sites, which they invest with deep reverence.

28

To quote Philip

“Greywolf” Shallcrass, former Joint-Chief of the British Druid Order,

“Many Druids like to make ritual at ancient stone circles since there is

a feeling that they are places where communion with our ancestors may

be made more readily than elsewhere. There is also a sense that making

ritual at such places energises and benefits both the sites themselves and

the land around.”

29

Contemporary Druids continue to forge connections with their

“ancestors” by becoming active participants in discussions concerning

the disposition of skeletal remains found at megalithic sites such as

Stonehenge. Shallcrass, for example, has been active in asking archae-

ologists and National Trust officials in England to treat any excavated

remains with respect and to return them to their original burial sites

when their examinations are completed. This is important, in his view,

as “our ancestors clearly didn’t select their burial places at random,”

and, he believes, “they should be returned to the Earth as close to the

original grave sites as possible.”

30

Druid Paul Davies takes issue with the

whole enterprise of disinterring skeletal remains from megalithic sites,

arguing “Guardians and ancestors still reside at ceremonial sites such as

Avebury and the West Kennet Long Barrow . . . [excavations] are disre-

spectful to our ancestors. These excavations are digging the heart out of

Druidic culture and belief.”

31

In an effort to find a workable solution to

these concerns, Shallcrass has offered his services as a Druid shaman to

perform rituals with the spirits of the ancestors when reburials take

place at sites such as Stonehenge.

32

Archaeologists have reconstructed many prominent megalithic sites

over the past 150 years. They attempt to match their reconstruction

with what they believe was the site’s original form, but inevitably

anachronisms creep in, such as the transparent blocks built into the roof

of passage tombs and long barrows to allow for illumination of the inte-

rior. The West Kennet Long Barrow in Wiltshire is one such recon-

structed monument, but it has not lessened the site’s popularity within

the nature spirituality subculture. As one respondent put it, “Even

though I know it is reconstructed, I also know that the whole Avebury

landscape, of which West Kennet is a part, was of national spiritual

importance in the Neolithic era and I gain a great deal of satisfaction

from performing ritual there.”

33

Ultimately, this first reading of megalithic sites represents a desire by

the nature spirituality community to reconnect with a lost tradition that

Nova Religio

36

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 36

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

venerated the natural order and sought harmony with its deities and

forces. They see this lost tradition as an antidote to the exploitative atti-

tude toward the environment that has characterized conventional

Christian churches and Western civilization in general since the

Protestant Reformation and the Industrial Revolution. As one respon-

dent from Cornwall reflected, the attraction of megalithic sites for

Pagans has to do with “a wish to hearken back and reclaim and re-find

what we might have lost from the past. We don’t know for certain exactly

what ritual and religious significance most of these sites had . . . but it

seems reasonable that they might have been [used to practice Pagan rit-

uals].”

34

Thus, megalithic sites provide practitioners of nature spiritu-

ality with tangible connections to an idealized past era of harmony

between the natural and human orders. They serve as potent symbolic

37

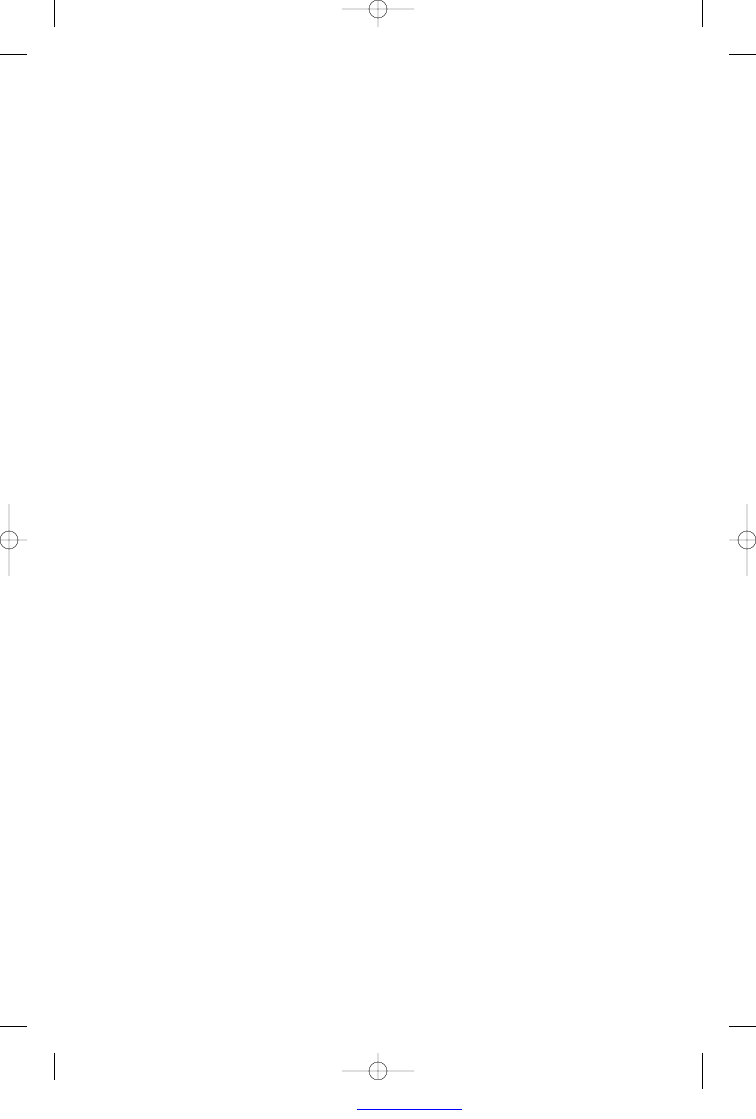

Image A:

Stonehenge

“Contemporary Druids and other participants celebrate sunrise at

Stonehenge on the morning of the Summer Solstice.”

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 37

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

centers around which to construct empowered spiritual identities that

resist the secularized and disenchanted (dominant) culture of late

modernity, and to practice a reinvented religion of nature.

MEGALITHS AS SITES OF COMMUNITY BUILDING

A second interpretation of megalithic sites sees them as places where

community building can occur for various participants in the nature

spirituality subculture. In many ways nature spirituality communities

share characteristics of postmodern “neo-tribalism” as theorized by

Zygmunt Bauman. For Bauman the postmodern world is characterized

by complexity, unpredictability, and the absence of a supreme goal-set-

ting power center. Individual identity in this state of affairs is fluid and

in a state of continuous refinement and reconstruction. In search of a

usable social identity, individuals seek out “new tribes” or communities

that often lead a distinctive existence on the periphery of mainstream

culture. These “new tribes” provide a home for postmodern wanderers

who share religious, political, and/or ethical orientations.

35

The nature

spirituality “tribes” are dynamic, ephemeral, and bio-degradable; they

often form spontaneously around various identity discourses that are

themselves in a state of elaboration and development. Some last only for

a time and a season, such as, for example, when groups form to protect

a megalithic site from commercial development or a new roadway. As

Jenny Blain and Robert Wallis observe, groups within the Pagan sub-

culture have fluid or unclear boundaries, and many modern Pagans

belong to more than one coven, environmental group, or site protection

association.

36

Nature spirituality participants are also known for their

independence, aversion to hierarchies, and distrust of authority. Some

prefer to visit megalithic sites on their own, and find themselves pursu-

ing a solitary path.

37

Given all this, many in the nature spirituality subculture have come

to view megalithic sites as places where they can meet and communicate

with kindred spirits whose ideals and values they share. For these par-

ticipants, the sites resemble the ancient gorsedds or meeting places where

chieftains, elders, shamans, and bards conferred on important tribal

matters. Covens, Druidic orders, neo-shamanic workshops, scholarly

gatherings, goddess groups, and Celtic spirituality groups choose to

hold meetings and rituals at the sites, in recognition of their historical

association with tribal events. One such place, the Boscawen Un stone

circle in Cornwall, is believed by local Pagans to have been one of the

principle gorsedds of ancient Britain. Sites like these provide a public

sacred space—a sanctuary—where isolated individuals can come to feel

part of a broader movement of spiritual and ecological awakening.

For New Age Travelers

38

and groups like the anarchic dance collec-

tive Mutant Dance, sites such as Stonehenge and Avebury have served as

Nova Religio

38

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 38

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

gathering places where like-minded nomadic tribes could meet for free

festivals during seasonal celebrations such as Midsummer. These groups

interpret the sites as prehistoric meeting places where people gathered

to feast, trade goods, make music, and celebrate tribal solidarity. They

come to the sites for similar community-building reasons, and the all-

night revelry, musical improvisations, handfastings, naming ceremonies,

and ritual magic they participate in builds a strong sense of neo-tribal

identity and solidarity. As one Pagan activist observed, “There’s a strong

sense of there being a tribe at Stonehenge, and one of the problems was

that people couldn’t meet each other anymore, when the gatherings

here were banned [in the 1980s and 1990s] . . . [For] the blessings of

children and the marriages in some sections of the community . . . it was

very important to come here.”

39

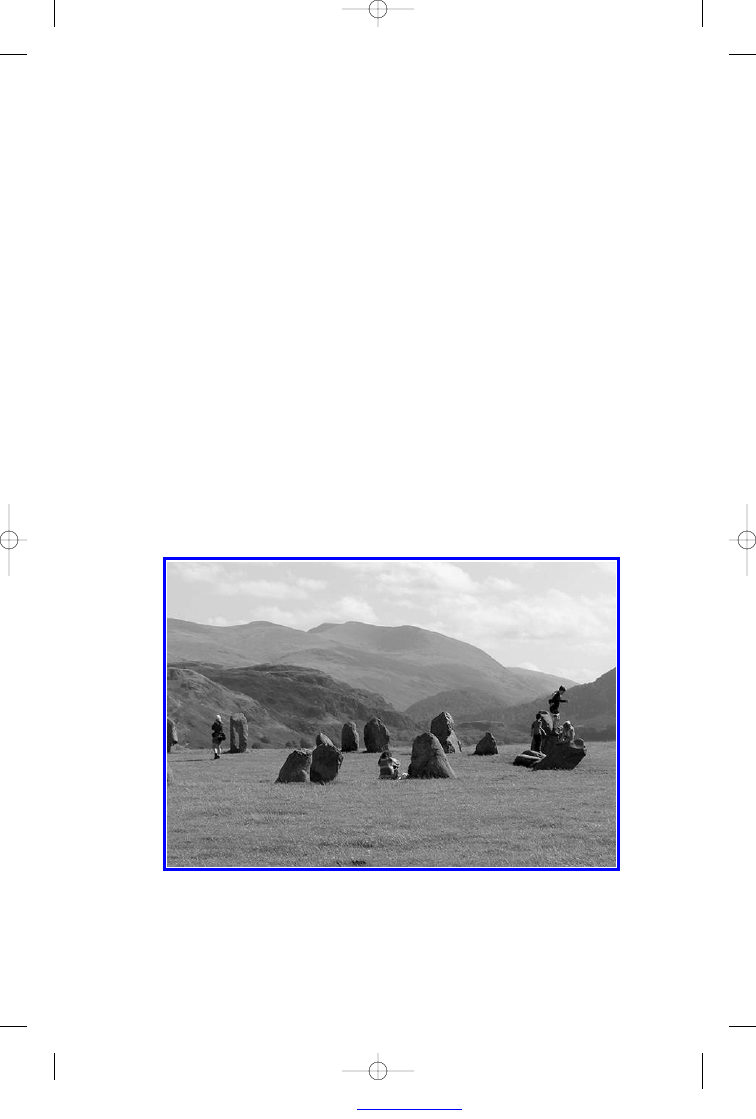

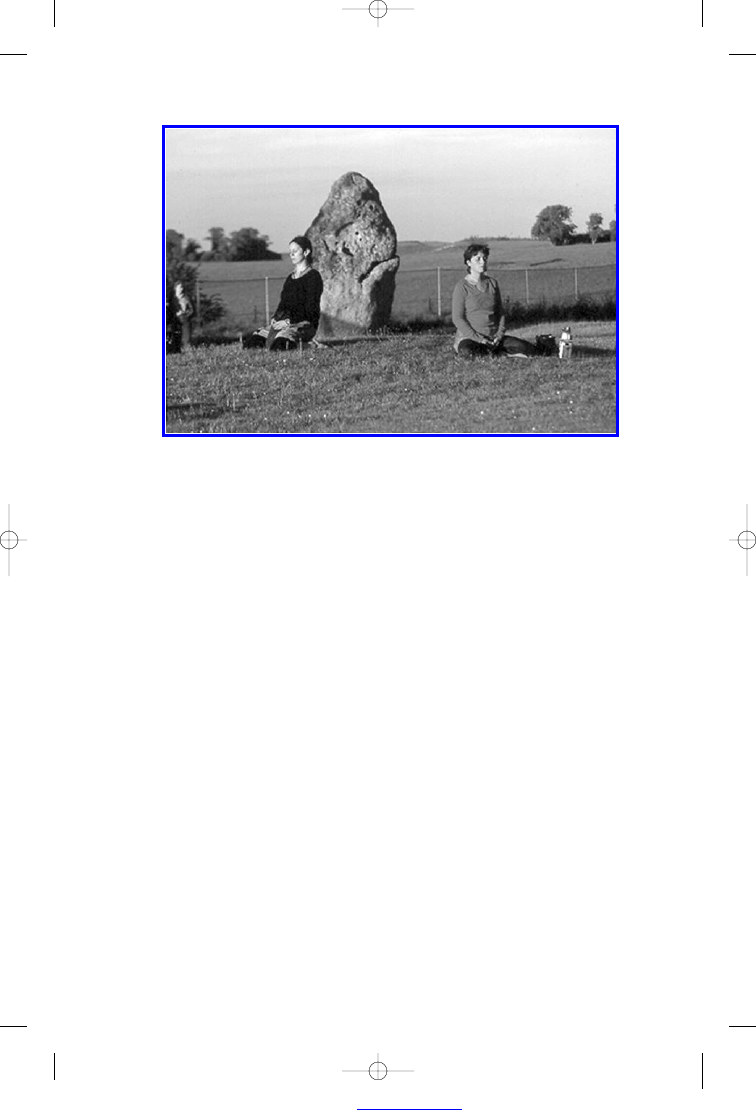

My own fieldwork confirms this community-building aspect of mega-

lithic sites. During one summer solstice celebration at Castlerigg stone

circle in 2000, an independent group of witches spontaneously gathered

together the various visitors to the site and performed a collective ritual

for world peace that included incantations, songs, dancing, and other

forms of merriment. The ritual broke down social barriers among the

participants, who included elderly mountain hikers, teenagers, mothers

and fathers, Wiccans, neo-shamans, and New Age Travelers. The inter-

actions after the ritual had a warmth and intimacy that was missing in

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

39

Image B:

Castlerigg

“Pilgrims at the Castlerigg Stone Circle in Cumbria, Northern

England, soak up the natural beauty of the site.”

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 39

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

the hours previous to this communal enactment.

40

On numerous other

occasions, I witnessed serendipitous meetings between both individuals

and small groups at remote sites throughout Western Europe.

Oftentimes friendships were formed, insights and ideas communicated,

food and drink shared, and rituals improvised. For seekers exploring the

world of nature spirituality, the megaliths were indeed sites of commu-

nity building, identity reinforcement, and ideological solidarity. Many of

my respondents spoke of “coming home,” and had an expectation that

they would meet their spiritual kindred at the sites.

Those who experience megalithic sites as community-building ven-

ues can also be understood as engaging in a postmodern rite of pil-

grimage. The anthropologists Victor and Edith Turner theorized that

pilgrimage was akin to the liminal phase in a classic rite of passage.

They maintained that the diverse individuals who come together at a

pilgrimage site experience a temporary erasure of their normative

identity markers and are fused into a powerful communal conscious-

ness by their focus on a common purpose. In the creative and trans-

formative space of the pilgrimage precincts, new bonds are forged

and new visions are born.

41

This experience of “communitas”—

although often ad hoc and spontaneous—is a significant aspect of the

magnetism that draws people to megalithic monuments. The sites

have become part of a sacred landscape visited by, among others,

Druidic orders (who celebrate the summer solstice at Stonehenge and

the winter solstice—and other Pagan festivals—at Avebury), New Age

tourists (such as those who ride the “Astral Bus” to megaliths in

Wiltshire), adherents of Celtic spirituality from North America (who

go on pricey tours to stone monuments in Ireland, Scotland, Wales,

and Brittany), and worshippers of the Mother Goddess (who travel to

Malta to experience the mysterious Neolithic Hypogeum at Hal

Safieni). By visiting these sacred geographies, pilgrims find a spatial

anchor for the creation of their alternative spiritual identities. As we

shall see in the next section, the megaliths are also sites of personal

transformation, where pilgrims journey on a quest for powerful expe-

riences that connect them with interior realms of spirit, spirit beings,

and an authentic “Self.”

42

SITES OF PRESENT SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE

A third way of interpreting megalithic sites sees them as places where

present spiritual experiences can occur. In this view stone circles and

other monuments are spaces whose atmosphere fosters entry into

altered states of consciousness; where it is easier to “step between the

worlds” and contact spirit beings; where developing spiritual identities

are reinforced and grounded in profound experiences of non-ordinary

dimensions.

43

In this sense they are similar to Shinto shrines in Japan,

Nova Religio

40

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 40

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

which are set up in places where people have experienced powerful con-

tact with kami, a word connoting spirit, deity, aesthetic awe, and the

numinous.

44

Many megalithic sites have legends attached to them in

which people who visit suddenly find themselves ushered into a hidden

world of subtle energies and spirit beings. One finds this theme articu-

lated in traditional folklore as well as in contemporary fiction.

45

Proponents of Celtic and neo-shamanic spirituality elaborate on this

theme by fostering a subjective interaction with the land and its

guardian beings. What emerges is a spiritual topography in which strik-

ing natural features of the landscape—for example, rivers, mountains,

and caves—become points of contact with the magical Otherworld.

These places include megalithic monuments, which are believed to

mark sacred places in the landscape where the “accumulated energies

of centuries of ritual activity” make the sites reservoirs of spiritual power

that can be accessed for vision quests, shamanic journeys, and medita-

tive focus in the present.

46

In my fieldwork I have often encountered

people meditating or vision questing while leaning against a standing

stone within a circle. Often these visionary journeys occur at sunrise or

sunset, moonrise or moonset, times traditionally associated with “open-

ings” between the ordinary and sacred worlds.

Earth mysteries author Paul Devereux elaborates on this third inter-

pretation by suggesting that megalithic monuments may have been used

as sites for divination, oracles, or as dream chambers in the distant past.

He speculates, for example, that in Druidic times—much later than the

Neolithic period—worshippers spent the night inside sacred sites in

order to experience dream revelations. Something about these sites,

Devereux contends, facilitates contact with the deep subconscious or

with other states of being, however understood.

47

Throughout his writ-

ings he promotes a way of seeing the landscape as ancient shamans may

have done, of listening to rather than reading preformed ideas into the

sites. In an interview with the author, Devereux said,

The idea is how to change your mental viewpoint when you are there to

allow in unconscious material . . . A product of the prehistoric place is a

product of another level of consciousness. If you can get into that level

of consciousness yourself you’ll get information that you can’t get using

an analytical approach.

48

From this perspective, Devereux has learned to appreciate ancient

megaliths as “dreamstones” that foster visions of power animals, ances-

tor beings, and guardian spirits in the stones themselves.

49

Some of my respondents reported experiencing prophetic or pro-

tective dreams and visions at the sites, while others reported oracular

phenomena. Jo May, a therapist connected with the Rosemerryn fogou

(a subterranean chamber usually from the Iron Age) in Cornwall,

observes,

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

41

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 41

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

The kind of phenomena experienced in the fogou . . . include inner

voices giving . . . pertinent guidance, sometimes forecasting events

before they happen; subjective perceptions of powers and presences—

usually of female figures, frequently described as “women in white” or

priestesses; visions involving the laying-out of the dead in preparation for

the soul’s journey to another realm; [and] visions of enforced

entombment for the purpose of confronting the dark side of the soul in

order to re-emerge reborn.

50

Devereux’s Dragon Project recorded thirty-five volunteers’ dreams at

four outdoor sites in England and Wales, including a Neolithic dolmen

and a fogou in Cornwall. The subjects were awakened during rapid eye

movement periods and asked to give oral dream reports to a research

assistant. An equal number of dreams recorded at the subjects’ homes

constituted a control group. Two judges then evaluated the dream

reports using the Strauch Scale to measure “magical” and “paranor-

mal” themes. About 45 percent of the dreams at the outdoor sites fell

into these thematic categories, while only 30 percent of the home

dreams did. Although no definitive explanation has been given for this

difference, the results do suggest that some anomalous properties of the

sacred sites themselves could be involved.

51

In this vein it is important to note that the neo-shamanic movement

has increasingly embraced megalithic sites as part of its toolkit for soli-

tary vision quests and group initiatory rituals. Practitioners are drawn to

the sites for various reasons, but a particular attraction is the sites’ puta-

tive use by tribal shamans in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Another

attraction is the shape of passage tombs. Many of these monuments

resemble a womb-like cave with a passageway to a central chamber that

mirrors the birth canal. In many cultures caves have been regarded as

entrances to the underworld or symbolic wombs of rebirth. Some neo-

shamans see passage tombs as ancient sites of initiation into the mys-

teries of life and death. The interior of a passage tomb, they maintain,

can be read as a microcosm of the cosmos, with the dome of the tomb

representing the upper world, and its echo under the earth represent-

ing the lower world. Within this microcosm, the shamans acted out

their role as mediators between the three realms (upper world, middle

world, and underworld).

52

Evidence from my fieldwork indicates that

many passage tombs are used for this kind of shamanic journeying by

contemporary neo-shamans.

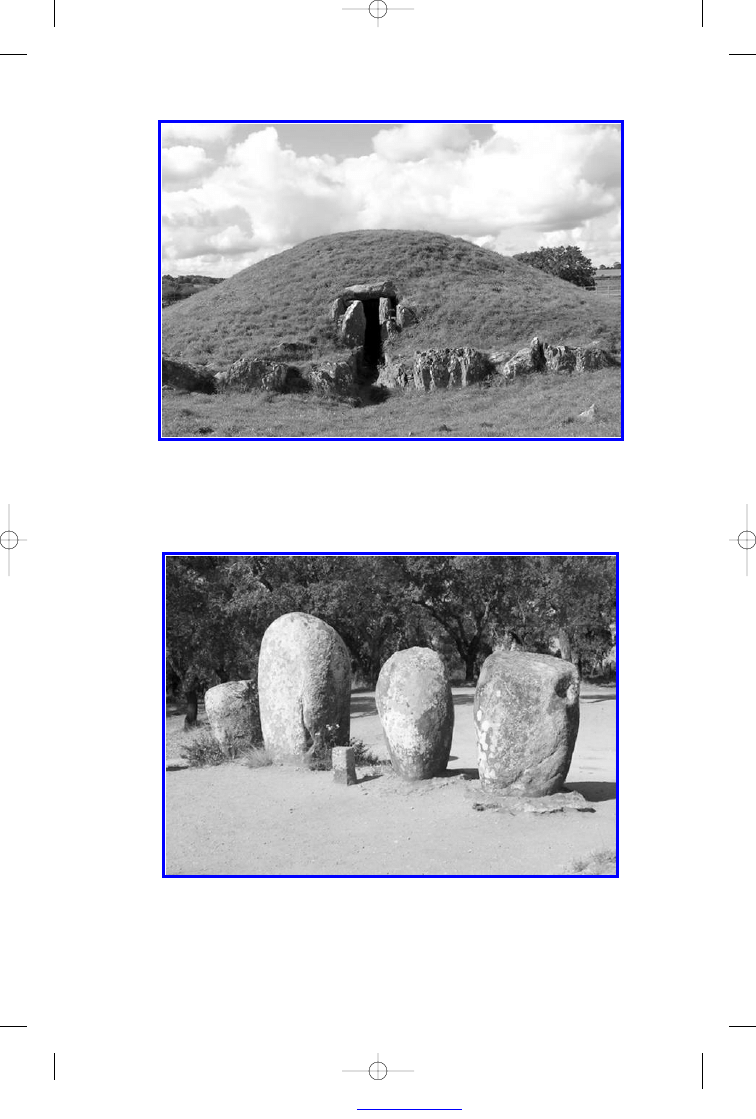

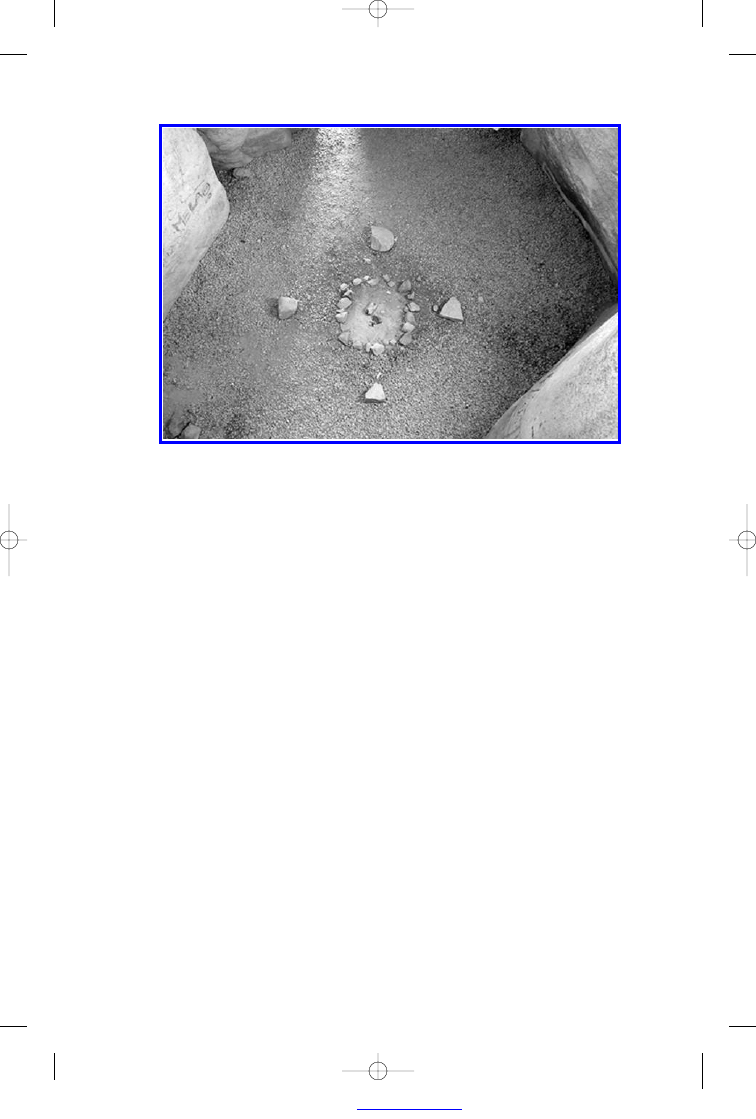

Sometimes the rituals of neo-shamanism include actual physical con-

tact with the stones, either by touching with the hands, the forehead, or

the spine. One respondent in Portugal, a German neo-shaman, takes

her students to the Almendres stone circle near Evora. This massive

cromlech has one stone with a large cup-like indentation. The respondent

related how—shortly after moving to the area—she had been drawn to

place her forehead in the indentation. The depth of the altered state of

Nova Religio

42

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 42

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

43

Image C:

Brykelidhu

“Contemporary Druids consider the Passage Tomb of Bryn Celli

Ddu on the Isle of Anglesey a sacred site and often leave

offerings.”

Image D:

Almendres

“These four stones from the Almendres Cromlech in Portugal

include one stone used for Neoshamanic vision questing.”

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 43

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

consciousness she experienced convinced her to use the stone as a site

for student vision quests. At propitious moments during the annual sea-

sonal and lunar cycles, she takes students to place their foreheads

against the stone as a means of inducing shamanic journeying.

53

Devereux’s research into acoustical resonances at megalithic mounds

revealed that all the sites in the study yielded resonance frequencies in

a narrow band that lies squarely within the vocal range of adult males.

He speculates that Neolithic ritualists likely used singing or chanting at

propitious moments such as sunrise on the winter solstice to create “an

alchemical exchange of light and sound: regenerating solar light for the

ritualists and the ancestral spirits within, awesome sounds announcing

the cosmic moment for the congregation outside.”

54

The resonance

frequency of the inner chambers would have enhanced the volume and

reverberation of the human voice, “creating the commanding sense of

the presence of supernatural agencies, whether gods or ancestral spir-

its.”

55

My own fieldwork has uncovered evidence of group rituals in pas-

sage tombs from Ireland to Denmark; these neo-shamanic rituals

include singing, chanting, and drumming as well as the use of hallu-

cinogens to amplify the influence of these sounds and thus to induce

altered states of consciousness.

Another of the present spiritual experiences reported by respondents

is contact with spirit beings, however conceived. For some, these are

guardian spirits attached to specific sites. One respondent reported

encountering such a spirit while preparing a megalithic site for a group

ritual during the 1999 solar eclipse in Cornwall. After reassuring the spirit

of his benevolent intentions, he reported that the atmosphere changed

completely and he felt he had been granted permission to use the site.

This respondent also reports doing magical work involving spriggans, a

term derived from the Cornish sperysyan, meaning spirit beings. He notes

that spriggans are fierce protective spirits that live only in Penwith in West

Cornwall: “Spriggans haunt all the sacred sites, the weird and wonderful

cairns, the hilltop castles, the stone circles, quoits, and standing stones and

what they hate more than anything, and will attack without quarter, are

those who are miserly, mean-spirited and who threaten their homes.”

56

The respondent organized rituals to awaken “slowly, gently, carefully all

the wild elemental spirits in which Cornwall abounds” as a way to protect

sites during the expected eclipse celebrations.

57

Jo May, in his accounts of spiritual experiences at his fogou, mentions

his summoning of nature spirits with a Druidic-inspired silver ball with

chimes, which he rolls in the palm of his hand. After participants for-

mulate questions, he becomes the conduit for communications from

these spirit beings, speaking like an oracle in riddles and gnomic utter-

ances.

58

Graham King, the current proprietor of the Museum of

Witchcraft in Boscastle, Cornwall, considers megalithic sites particularly

auspicious places for contacting various spirit beings and nature deities.

Nova Religio

44

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 44

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

He also recommends labyrinths inscribed in stone monuments as places

where contact with spirit worlds can occur with greater ease.

59

I have

come across contemporary labyrinths constructed in stone circles and

passage tombs in Southern France, Ireland, and Denmark. It is possible

these labyrinths are used as sites of communication with various spiritual

realms.

60

Jenny Blain’s research into contemporary Heathens has uncovered

putative interactions between adherents and Norse deities, ancestral

spirits, house-wights, and land-wights connected with specific landscapes

and megalithic sites. This ties into Heathenry’s sense that the landscape

is alive and that sacred sites have guardian spirits (wights).

61

Each of

these examples supports the notion that practitioners of nature spiritu-

ality are using megalithic sites to facilitate entry into altered states of

consciousness and to construct spiritual identities grounded in per-

ceived contact with sacred dimensions and beings.

SACRED SPACES FOR SEASONAL RITES,

RITES OF PASSAGE, AND OFFERINGS

A fourth interpretation of megalithic sites treats them as ritual centers

where practitioners of nature spirituality can celebrate seasonal festivals

and various rites of passage. Pagans, Wiccans, Neo-Druids, and others

tend to celebrate the primary cycle of the solar year as well as monthly

lunar cycles, and eclipses.

62

Their annual seasonal cycle mimics the

accepted Celtic ritual calendar and includes Samhain, the Celtic New

Year feast on November 1; the winter solstice on December 21; Imbolc,

the midwinter festival on February 1; the vernal equinox on March 21;

Beltane on May 1; the summer solstice on June 21; Lughnasadh on

August 1; and the autumnal equinox on September 23. The most impor-

tant lunar festivals are the new moon, celebrated when the first sliver of

waxing crescent appears in the western sky at dusk, and the full moon.

Solar and lunar eclipses each occur twice a year, although generally the

solar eclipses that approach totality are the most celebrated of these

phenomena. Over the past twenty-five years, the celebration of these

cyclical events at megalithic sites has increased “exponentially,” accord-

ing to one respondent.

63

As stated earlier, megalithic sites have become

significant ritual centers because of their association with pre-Christian,

Pagan religions that many followers of nature spirituality believe were

matrifocal, nonviolent, and goddess worshipping.

64

The popular Samhain rites occur in early November and are often cel-

ebrated in megalithic passage tombs, long barrows, or fogous. The festival

marks the close of the agricultural year and the beginning of a new annual

cycle. It is a time of the return of the darkness, symbolic of the Cauldron

of the Goddess, the Otherworld womb from which all life springs.

Practitioners of Celtic spirituality believe that this three-day celebration

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

45

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 45

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

breaks down the space-time barriers that keep the Otherworld hidden

from the ordinary realm. It is a time to celebrate ancestors, wise elders,

and supernatural beings who can pass over the space-time continuum to

commune with the “tribe.” Rituals celebrated at this time include the

casting of sacrificial objects onto a bonfire; an invitation to the ancestral

spirits to join the circle and receive offerings; the holding of a torch or

candle by the ritual leader while facing the southwest (the most auspicious

direction for contact with Otherworld beings); circumambulation of the

ritual area three times to create a bridge to the otherworld; communion

with spirit beings; lustrations from the ritual cauldron; divination; and

feasting.

65

The Winter Solstice rites celebrate the return of light at the darkest

point of the year. The timing of these rites is arguably on more solid his-

torical ground, in that it is supported by archaeological evidence at

many megalithic sites throughout Western Europe. At the Newgrange

passage tomb in County Meath, Ireland, for example, an aperture con-

structed above the entryway allows light to enter the passageway as the

sun rises over the eastern horizon on the winter solstice. This light

slowly illuminates the passageway until the entire central chamber is set

ablaze. A similar phenomenon occurs at sunset on the winter solstice at

the Maes Howe passage tomb in the Orkney Islands. Clearly, winter sol-

stice was a significant event for Neolithic peoples. I found numerous

instances of celebration of this festival during my field research. At

Lough Gur stone circle in Ireland, for example, the rites include prayers

welcoming the sunshine, a bonfire lit in the center of the circle, silent

meditation around the circumference of the stone circle, the voicing of

wishes for the New Year, and a feast with wine and cakes.

66

The tone of

rites at this time is introverted, intense, somber, and connected to work-

ing with ancestors. Black robes are favored over the white robes of sum-

mer festivals.

67

Another popular seasonal festival is summer solstice, which is

widely celebrated because of its connection to Stonehenge. The

Midsummer festival at Stonehenge attracted an estimated 14,500 par-

ticipants in 2001, 23,500 in 2002, 31,000 in 2003, and 17,000 in 2006.

68

While conducting field research at the site in 2001, I noticed several

rituals that took place from sunset on June 20 to the late morning of

June 21. One Pagan festival troupe marched into the circle from the

west at sunset playing pipes, drums, and a long trumpet. They then

conducted a group invocation to celebrate sunset and played festive

music while bystanders danced and feasted. Another Pagan group car-

ried a “green woman,” a fertility symbol constructed of leaves and

branches, around the circumference of the circle at sunset before

placing the emblem against one of the sarsen standing stones. A soli-

tary Druid priest, clad in white and carrying a staff, approached the cir-

cle from each of the four cardinal directions in silence before entering

Nova Religio

46

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 46

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

the circle itself. At dusk, many visitors meditated in solitude at various

locations around the circle’s periphery. The entire site had a carnival

atmosphere throughout the night, with drumming, singing, acrobat-

ics, dancing, and general merrymaking celebrating the seasonal apex

of the earth’s forces of fertility and life.

69

At dawn during the 2000 and 2001 Midsummer celebrations at

Stonehenge, thousands of people faced the Heelstone at the site’s

northeast quadrant “waiting as sky, mist, stones and celebrants became

part of an experience that was deeply moving.”

70

They joyously “cele-

brated the growing brightness in the sky, each in their own way: those

inside the circle of stones drumming and cheering, druids conducting

ceremonies on the north side of the circle, and many others standing to

the south, watching the daybreak.”

71

As the sun rose over the Heelstone

the general buzzing rose to a roar as thousands of participants shouted,

chanted, and cheered. After this event, I observed several handfasting

ceremonies under the ceremonial direction of Pagan priests.

72

While attending the Midsummer celebrations at Castlerigg stone cir-

cle in 2000 I also witnessed a diverse array of ritual practices. These

included salutes to the spirits of the four directions, circumambulation

of the circle’s periphery, music-making with drums and didgeridoos, a

group ritual that built a cone of psychic power, silent meditations while

touching the stones, divination, dancing, and feasting. The celebrations

at both Castlerigg and Stonehenge included children, teens, young

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

47

Image E:

Pagans

“Two Stonehenge pilgrims meditate near the Heel Stone on the

evening before Summer Solstice sunrise, 2001.”

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 47

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

adults, and senior citizens.

73

These celebratory rites reinforce the spiri-

tual identities of participants by affording social confirmation for pri-

vately held beliefs and practices. They support the budding “plausibility

structures” that are forming within the contemporary nature spiritual-

ity movement.

74

One of the more influential books guiding nature spirituality ritual

is Michael Dames’ The Avebury Cycle, published in 1977, which used

archaeological speculations from the 1950s and Marija Gimbutas’ writ-

ings from the 1970s to posit the existence of Neolithic Mother

Goddesses. Dames proposed that the Avebury prehistoric landscape,

including Avebury stone circle, the processional avenues leading to it,

the Sanctuary, West Kennet Long Barrow, and Silbury Hill, was the stage

for an annual ritual cycle that honored the Mother Goddess and her

mysteries. Each monument was used in turn to celebrate a particular

event in the agricultural calendar. Silbury Hill, to cite one example, was

seen by Dames as an “effigy of the Great Goddess, the All Mother,

Mother Earth.”

75

It resembled a pregnant goddess from the air and was

associated with pregnancy, the lunar cycle, and the harvest festival of

Lammas. Within a short time of The Avebury Cycle’s publication, nature

spirituality adherents were celebrating Dames’ speculative rituals in the

Avebury landscape. Various goddess rites continue today at these sites,

including, for example, an annual women’s full moon dance on Silbury

Hill. Gimbutas’ theme of a matriarchal Neolithic culture that was

destroyed by a violent patriarchal culture during the Bronze Age was

picked up and used as a significant interpretive frame by musician Julian

Cope, the author of two popular guides to megalithic sites in Western

Europe, The Megalithic European (2004) and The Modern Antiquarian

(1999).

76

Dames’ influence on nature spirituality rituals is an example

of the constructed status of many elements of this movement as well as

evidence to support Berger and Luckmann’s sedimentation theory in

practice.

Another example of the cyclical rituals performed at megalithic sites

occurred during the total solar eclipse that darkened Cornwall in 1999.

According to one of the event’s chief organizers, inclusive rituals

attended by people from Western Europe and North America were per-

formed at the Hurlers stone circles, Men an Tol stone row, and

Boscawen Un stone circle, all of which are located in Cornwall. The rit-

ual at Boscawen Un began with participants circumambulating the cir-

cle and invoking the spirits of the four directions. Oberon

Zell-Ravenheart of the Church of All Worlds called upon the god and

goddess after which drums, flutes, didgeridoo, clapping, and chanting

were used to raise the cone of power around the great leaning center or

“King” stone. As the sky darkened and the temperature dropped, par-

ticipants fell silent and joined in a moment of awe and wonder at the

strange light and atmosphere that descended.

77

Nova Religio

48

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 48

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

Seasonal and astronomical celebrations are not the only kinds of

rites that occur at megalithic monuments. The sites are increasingly

used to celebrate various rites of passage, including conception, the

naming of newborns, handfastings, bereavement rituals such as ash scat-

tering, and esoteric initiation. The Rollright Stones, which is now owned

and operated by the Rollright Trust, takes bookings for various cere-

monies and events. These include public Pagan festivals, handfastings,

child-namings, family gatherings, annual Shakespeare performances,

and plays based on local Rollright’s folklore.

78

Other rites are more solitary in nature. One Pagan activist reports

that whenever she visits a local stone circle she walks around it with the

intention of honoring it and participating in its energy field. She goes

to alternating sides of the stones as a way to interweave a web of ener-

gies that connects her to the whole. She also honors a great stone at the

middle of the circle to celebrate the union of male and female energies.

In her vision the circle itself is female and the central stone is male.

Honoring both polarities constitutes a positive interaction with the spirit

of the site and what it symbolizes.

79

A final rite that is commonly observed at megalithic sites is the leav-

ing of various offerings. This practice has become somewhat controver-

sial because well-meaning visitors often leave ritual litter that can become

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

49

Image F:

Ritual Circle

“This Fire Circle honoring the four directions lies within the

Zambujeiro Dolmen, near Évora, Portugal.”

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 49

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

piles of trash over time. The most common offerings are organic in

nature, i.e., fruits, vegetables, flowers, grass wreaths, pinecones, shells,

wooden staffs, and stones. Each offering is a symbol that has either per-

sonal or generally accepted meanings. For example, seashells symbolize

the water element, stones or gems the earth element, a feather air and

spirit communication, while incense sticks and smudge sticks symbolize

fire and purification. Sweetgrass braids attract strength and guidance

from nature spirits, godseyes

80

symbolize the oneness of all life, cowrie

shells are symbols of the Goddess, and pomegranates are a traditional

offering for Samhain. At many sites goddess figurines are inserted into

corners or even left in plain sight as offerings to the Mother Goddess. At

a site in Cornwall I found polished stones, quartz crystals, coins, angel

cards, egg-shaped stones, a ritual staff, and photographs. At Long Meg

standing stone in Cumbria (shortly after Midsummer 2000) I discovered

cards inscribed with poems, flower wreaths, candles, and a purple ribbon

wrapped around the huge menhir at the level that an ancient spiral had

been inscribed. At Wayland’s Smithy long barrow near Marlborough, a

visitor had left a poem to the ancestral spirits of the site. Some visitors

leave cards or photos as memorials to deceased loved ones. Perhaps the

most common offerings I have observed are symbols of the four ele-

ments, often found together: a black feather (air), a stick of incense

(fire), a shell (water), and a sprig of grass or flower (earth).

Popular books on Celtic spirituality and shamanism advise visitors to

megalithic sites to make offerings as tokens of gratitude and exchanges

of energy. One author explains:

It should never be forgotten that the indiscriminate use of ancient sites

is a major contribution to their demise. The constant draining of power

by individuals and groups has stripped many of these places of their

inherent power. Thus you should always give back something in

exchange for what you take. The simple laying of a hand on one of the

stones, or on the Earth itself, is generally enough. Returning something

of what has been received, as a freely given gift, is always a good thing.

81

A neo-shamanic teacher gives specific directions to his students on

how to leave offerings at megalithic sites:

To make an offering, gently hold whatever you wish to give in your hand

and present it up to the sky. Lower your hand and present your offering

to the Earth to show appreciation to the Mother. Hold it out to each of

four directions, north, south, east and west, keeping in your mind the

connection between all things. As you leave the offering in your chosen

place, voice your thanks.

82

A third example describes an “intuitive offering” that includes

pouring water or whiskey into cupmarks (human-made indentations)

Nova Religio

50

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 50

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

on ancient megaliths and “watching it stream down the grooves.”

83

Pouring and lustration rituals are generally associated with fertility and

good luck in European folklore.

This last type of offering crosses a line for some Pagan writers. It is

similar to inserting coins, stones, and other offerings into cracks in

stones, decorating ancient stone engravings with white chalk to make

them more visible, drawings spirals or pentacles using chalk or paint,

lighting ritual fires near standing stones, or lighting votive candles

inside passage tombs for illumination. All of these acts threatens the

integrity of stone monuments and can deface or erode surfaces, and

split stones apart. These practices have fostered a preservation ethic

within the nature spirituality subculture that includes etiquette for

those leaving offerings at the sites. In its essentials, it admonishes visi-

tors to bring only organic offerings—preferably from the immediate

environment—and to take away whatever was brought when one

leaves.

84

The leaving of offerings encourages a subjective participation with

the perceived sacred presences at megalithic sites. It is akin to rites of

offering found in many religious traditions and reinforces the sense of

being part of an authentic tradition of earth spirituality that has roots in

the deep past.

POINTS OF CONTACT WITH ENERGIES OF HEALING

AND SELF-EMPOWERMENT

A fifth reading of sacred sites sees them as places where powerful

natural energies can be accessed for healing, magic, ecological

activism, and personal empowerment. This interpretation of the sites

has its roots in an unorthodox view of human prehistory, a view most

clearly articulated by earth mysteries authors such as John Michell,

Robin Heath, Francis Hitching, Hamish Miller, and Paul Broadhurst.

These writers speculate that Neolithic peoples practiced an advanced

spiritual science that harmonized body and mind with powerful ter-

restrial and celestial forces. According to these authors, these ancient

cultures saw the earth as a living grid of subtle forces, and marked spe-

cial “nodes” and “vortices” in this vast web of energy by building mega-

lithic monuments on them. This allowed these cultures to harness

terrestrial and celestial energies for healing, fertility, self-defense, and

spiritual journeying.

85

The writings of Iris Campbell and John Foster Forbes provided sup-

port for these views by arguing that survivors from Atlantis had built the

great megalithic monuments and used then for “elemental magic.”

They claimed that the quartz stones that are a regular component of

megalithic monuments could draw “telluric” currents and focus stellar

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

51

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 51

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

influences during particular seasons and cosmic cycles. The stones at the

sites “picked up earth vibrations” and transmitted messages from long

distances to those who pressed their hands against certain stones.

Campbell believed that the Mayborough Henge monument near

Penrith in Cumbria was built to gather magnetism from the four direc-

tions; this energy was then used to enhance etheric centers in the

human body.

86

Another researcher whose views became influential for this fifth

interpretation is Alfred Watkins, an antiquarian who studied old

straight tracks within the British countryside. Watkins is credited with

coining the term “leys” for straight lines between significant landscape

features and hill forts, megaliths, churches, and other human con-

structions. Over a period of forty years, Watkins’ observations mor-

phed into the idea of “ley lines,” putative energy pathways that

connected megalithic monuments and natural landscape features.

Believers in ley lines and subtle energies called, among other terms, tel-

lurgic energy, chi, and dragon force use psychic, intuitive, and occult

methods—such as dowsing—to both measure and harness these ener-

gies at megalithic sites.

87

A good example of this way of reading megalithic sites can be found

in the writings of Jo May, who envisions his fogou at Rosemerryn,

Cornwall, as part of a local energy complex (the “Lamorna Temple”)

that includes other megaliths in Penwith. May sees this complex as an

analogue to the Hindu chakra system that distributes subtle energies in

the human body.

88

My field research has observed numerous instances of this “energies”

reading of ancient megaliths. Several examples will have to suffice.

While walking along the Druids’ Way stone row in Brittany, I met a man

who practiced alternative healing using crystals. He did this by placing

the crystals at different points on a patient’s body as a way to release

blockages that were affecting the body’s subtle energy system. When I

encountered the man, he had placed about 20 large crystals on a promi-

nent stone in the row. He told me that his teacher had awakened the

stone in an esoteric ritual, and that it was now a powerful source of heal-

ing energy. Every month he came down from Paris to “recharge” his

crystals by placing them on the “awakened” stone.

89

At numerous sites I saw New Agers using a pendulum to measure

subtle forces in stone circles and dolmens. In one instance, I encoun-

tered a retired electrical engineer at a chambered cairn near

Inverness, Scotland, who was using a pendulum to determine which

stones belonged in the cairn and which stones had been thrown there

by the local farmer. He told me he was removing the dissonant stones

so that the entire site could be returned to its original function as part

of Britain’s primordial energy grid. The engineer was a resident of

Findhorn and explained that he was part of a project to “retune” the

Nova Religio

52

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 52

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

ancient megaliths of Great Britain so that the land could once again

receive beneficial terrestrial and celestial currents. These currents had

been blocked by modern industrial and commercial developments, as

well as by the gradual decay of megalithic sites over the past 4,000

years. Part of the “retuning” at this site included the placing of crystals

and precious stones at the base or top of uprights in the cairn’s sur-

rounding stone circle.

90

Such alterations in megalithic sites, it should

be added, are strongly condemned by archaeologists and many mod-

ern Pagans, who believe in leaving sites the way they are for the most

part.

The efforts of participants in the nature spirituality subculture

(whether New Agers or Pagans) to “retune” or “work ritual” within

megalithic sites fits into an overall conception of the sites that is akin

to how acupuncturists view the human body. When an acupuncturist

inserts a needle into a “meridian” on the body, it is believed to affect

a circuit that conducts subtle energies to other parts of the body.

Inserting the needle relieves blocked energies and encourages proper

flow. This in turn brings needed vital forces to organs that are depleted

or undernourished. The effort to retune megalithic sites—again, a

highly controversial activity—is often conceived by New Agers as a

kind of acupuncture treatment designed to unblock energies and

restore overall health to the body of Gaia, the living being of the

earth.

91

The energies believed to be present at the sites are often used for

healing activities of various kinds. I observed one such treatment at the

Rollright Stones in 2001. A man was moving his hands in slow passes

over the body of a woman who was reclining on her back in the center

of the circle. In a subsequent interview, the man identified himself as

a Reiki practitioner from London. He said that his teacher had often

brought students to Rollright because the healing energies of a treat-

ment were greatly intensified within the circle. The Reiki practitioner

now brought his own clients to the circle to access its special energies

for his treatments. In my field research I met numerous other alterna-

tive health practitioners who brought staffs, wands, pendulums, crystals,

and other paraphernalia with similar notions about the healing ener-

gies that could be tapped at megalithic sites.

92

The practices associated with accessing the “energies” of megalithic

sites can be understood as ways to construct spiritual identities that are

empowered by communion with perceived celestial and terrestrial

forces. Through dowsing, energizing ritual implements, and “retuning”

or reawakening the monuments, nature spirituality adherents believe

that they are harmonizing themselves with subtle energies with which

modern scientism and rationalism have lost contact. They can use their

attunement to these perceived forces for healing work in both the

human and other-than-human realms.

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

53

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 53

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

SITES OF POETIC, ARTISTIC,

AND MUSICAL INSPIRATION

A sixth and final interpretation of megalithic monuments views them

as places of poetic, artistic, and musical inspiration. This more aesthetic

reading begins with the etchings of megaliths by antiquarians William

Stukeley, William Borlase, and William Cotton in the eighteenth and

early nineteenth centuries. It continues with landscape painters like

John Constable and J. M. W. Turner, who were enchanted with

Stonehenge and produced watercolors and paintings that dramatized

the site’s mystery, antiquity, and grandeur.

93

Poets like Wordsworth and

novelists like Thomas Hardy were also inspired by megalithic monu-

ments during the Victorian Era. This aesthetic reflex has continued in

the present era with “Land Art” visual artists like Richard Long, whose

paintings are famous for their stone-row-inspired lines in remote land-

scapes, and Robert Morris and Herbert Bayer, whose earthworks echo

ancient henge monuments, barrows, and passage tombs. An “Earth

Mysteries” exhibition toured the British Isles during the late 1970s and

brought large crowds to view prints, drawings, paintings, photography,

sculpture, and installation art inspired by the forms and geometry of

megalithic monuments. Two Cornwall artists, Sarah Vivianne and Ian

McNeill Cooke, continue in this tradition in the twenty-first century, pro-

ducing paintings and other artwork depicting idealized visions of local

stone circles, standing stones, and quoits. Vivianne describes her artistic

inspiration as

part of my response to the Earth’s energies in the sacred sites . . . It’s part

of my spirituality. The two are very closely connected. I go to sacred sites.

I experience the sensations, the feelings, the energies. Because I’m

trained as a painter a lot of that is a very visual experience. And so when

I’m painting its part of the process of honoring and celebrating the

sacred sites.

94

During my fieldwork I have met solitary writers, painters, and musi-

cians who regularly visited the sites to soak up their atmosphere and

await inspiration. In one instance, I encountered a professional musi-

cian at a recumbent stone circle in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, who came

to the circle whenever his creative muse was blocked. The day I visited

the site he was busy scribbling away in a notebook under a sunny sky

while lying prone on the huge recumbent stone.

95

This aesthetic reading of the sites influences a large number of visi-

tors, many of whom have no connection with nature spirituality as such.

Nevertheless, this aesthetic response augments the sense of mystery,

ambience, and sacrality that informs the five other readings of the sites

we have discussed.

Nova Religio

54

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 54

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

CONCLUSION

Each of these six interpretations of megalithic sites is an exercise in

identity construction that mixes myth and history, vision and memory,

imagination and ritual. For contemporary people in search of a spiri-

tual identity that is body- and nature-friendly and that addresses press-

ing ecological commitments, the sites serve as potent symbols of a time

when humanity was believed to have lived more gently and harmo-

niously on the earth. For some the sites foster transformative spiritual

experiences by facilitating contact with alternative realities and states of

consciousness. Contemporary Druids reaffirm their identity with the

earth and the “Celtic tradition” by practicing rituals constructed from

bits of folklore, myth, local history, and oral traditions at the megaliths.

Neo-shamans reinforce their self-identified role as bridges between the

worlds by journeying to the realms of nature spirits and power animals

at the sites. During their solitary pilgrimages to the sites, other seekers

craft spiritual identities from the ancient voices they hear, the inspira-

tions and revelations they receive, and the healing dreams and visions

they experience. For many the sites serve as ritual centers where they

can celebrate terrestrial and celestial cycles and build communities of

kindred spirits. The megaliths serve as touchstones from deep antiquity

for those who wish to re-enchant a world left disenchanted by scientism

and industrialization. For yet others the megaliths offer connection to

powerful natural energies that can be used for healing and self-empow-

erment. Their various rites of touching and circumambulation allow

them to recharge their ritual tools and reenergize spiritual commit-

ments and orientations. Finally, the sites can serve simply as places of

aesthetic, artistic, musical, and poetic inspiration; places removed from

the ambient strains and stresses of urban life where the creative imag-

ination can be re-stimulated and where visions, both ancient and mod-

ern, can foster wholeness and integration.

The interpretations of megalithic sites are in a continual process of

refinement and change. In a freewheeling, egalitarian, and grassroots

manner, individuals and groups have cobbled together eclectic readings

of these sites using a vast array of historical information, myths, folklore,

esoteric traditions, archaeological research, and ritual imaginaries. This

interpretive process is occurring outside the control of governing elites,

ecclesiastical authorities, or dominant religious institutions.

96

It is at

root an exercise in both individual and communal identity construction;

a movement of resistance to a world system that has lost its secure moor-

ings in the natural order.

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers who generously

offered their expertise during the revision process. This paper is stronger

in both style and substance because of their suggestions and critiques.

Lucas: Constructing Identity with Dreamstones

55

NR1101_02.qxd 6/8/07 2:22 PM Page 55

This content downloaded from 156.17.98.171 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 06:29:50 AM

All use subject to

ENDNOTES

1

For a further discussion of postmodern identity issues, see Peter Berger, The

Heretical Imperative: Contemporary Possibilities of Religious Affirmation (Garden City:

Anchor Books, 1980); Kenneth Gergen, The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in

Contemporary Life (New York: Basic Books, 1991); and Anthony Giddens,

Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Cambridge:

Polity Press, 1991). For a discussion of identity construction and national meta-

narratives, see Karen A. Cerulo, Identity Designs: The Sights and Sounds of a Nation

(New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1995).

2

Jenny Blain and Robert J. Wallis, “Sacred Sites, Contested Rites/Rights:

Contemporary Pagan Engagements with the Past,” Journal of Material Culture 9,

no. 3 (2004): 240–41. Jenny Blain, email communication with author, 25 January

2000.

3

Adrian J. Ivakhiv, Claiming Sacred Ground: Pilgrims and Politics at Glastonbury and

Sedona (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 2001), 4.

4

Ivakhiv, Claiming Sacred Ground, 8.

5

This term denotes a witch who works alone and who practices wildwood

mysticism, a hidden knowledge believed to be at the root of witchcraft. See Rae

Beth, The Hedge Witch’s Way: Magical Spirituality for the Lone Spellcaster (London:

Robert Hale, 2003).

6

Heathenry denotes a modern revival of Germanic/Norse Paganism and is

frequently used as a self-designation by followers of Germanic Neopaganism in

the United Kingdom. Heathens seek to re-create Pagan belief and practice

using literary sources—specifically the Eddas and Sagas—and archaeological

sites such as stone circles. Adherents seek a deeper connectedness to local

landscapes and communication with the wights, ancestors, and other spirit

beings tied to these landscapes. The tradition is polytheistic, animist, and

employs shamanism in its rituals and magic. See also Jenny Blain, Nine Worlds of

Seid-Magic: Ecstasy and Neo-shamanism in Northern European Paganism (London:

Routledge, 2002).

7

Ivakhiv, Claiming Sacred Ground, 7–8. My designation “nature spirituality” is

coterminous with Ivakhiv’s conception of “earth spirituality” or “ecospirituality.”

My term has a greater European flavor than Ivakhiv’s conception, which has a