Original Paper

.

Physical Education and Sport, 51, 20 - 22, 2007

DOI: 10.2478/v10030-007-0001-3

Authors’ contributions:

Achievement motivation and physical fitness of 15-

year old girls

A Study design

B Data collection

C Statistical analysis

D Data interpretation

E Literature search

F Manuscript preparation

G Funds collection

Monika Guszkowska

B - F

, Tadeusz Rychta

A B E G

Department of Psychology, Academy of Physical Education, Warsaw, Poland

Key words

Summary

Study aim: To determine the relations between the general and physical education-specific

achievement motivation, and physical fitness of adolescent girls.

Material and methods: A group of 52 girls aged 15 years were studied by applying two

questionnaires: P-O scale of Widerszal-Bazyl for evaluating the general achievement

motivation and Nishida’s AMPET for evaluating achievement motivation for learning in

physical education (PE), and the International Physical Fitness Test.

Results: Unlike the specific achievement motivation, the general one was uncorrelated

with physical fitness variables and had no predictive value for that fitness. Nishida’s

indices of achieving success in PE correlated positively with some fitness variables, and

the indices of avoiding failures – negatively. The only significant predictor for physical

fitness proved the variable “overcoming obstacles”.

Conclusions: Motivational factors ought to be considered as a determinant of fitness test

results attained by adolescent girls. The results confirmed the usefulness of Nishida’s

model in predicting physical education achievements.

Physical fitness – Achievement motivation – Physical education - Girls

Introduction

Physical activity was reported to be related to per-

sonality features, the relations being gender-dependent

[7]. It may be speculated that personality traits are re-

lated in boys to the “potential” and “ability” compo-

nents of motor activities, and in girls predominantly to

the “volitional” component [10]. That last component is

a motivational one and is the key to dedication in motor

performance. According to Przewęda [6], motivation

plays a fundamental role in performing prolonged, diffi-

cult and/or unpleasant motor tasks (e.g. long-distance

run).

Achievement motivation has been regarded as a re-

sultant of two opposing tendencies [1]: to achieve suc-

cess and to avoid failure. The intensity of motivation to

achieve success may depend on the hierarchy of values

and on the importance of the objectives being accom-

plished by given subject, therefore, individual outcomes

ought to be de-termined rather by the need of a specific

success than by the general motivation for successes.

The contemporary views on motivation in physical

education are often referred to discerning the motives to

achieve success and to avoid failure, although Elliot [5,6]

presented an integrated model containing both motives.

Nevertheless, the complexity of motivational processes

and their multiple conditioning [2,4,11].

Achievement motivation in physical education was

also presented by Nishida [8,9] and that particular model

was adapted to Polish conditions. In that model, motiva-

tion as a resultant of two opposing tendencies is regarded

as driven by interests, cognitive curiosity, perceived

motor potential, previous experiencing successes and

failures and, additionally, depends on subject’s diligence

and responsibility, his/her intellectual potential, compo-

sure and the will to follow good example. Those who

exhibit a strong achievement motivation in physical

education strive for perfection, have positive attitude

towards learning, formulate appropriate objectives, es-

pecially the long-range ones, plan their actions, employ

original learning approaches, effectively overcome ob-

stacles, their anxiety of stressful situations and failure

Author’s address

Prof. Monika Guszkowska, Department of Psychology, Academy of Physical Education, Marymoncka 34,

02-968 Warsaw, Poland

mguszkowska@wp.pl

Achievement motivation and physical fitness

21

being low. It may thus be assumed that this model takes

into account practically all achievement determinants in

physical education emphasised also by other researchers

[2,4,11,12].

The aim of the study was to determine the relations

between the general and physical education-specific

achievement motivation, and physical fitness of adoles-

cent girls. It was expected that the physical education-

specific achievement motivation would be stronger

correlated with the results of fitness tests.

Material and Methods

A group of 52 girls aged 15 years were studied. Two

questionnaires were applied: P-O scale of Widerszal-

Bazyl [13] for evaluating the general achievement moti-

vation and Nishida’s Achievement Motivation in Physi-

cal Education Test (AMPET [8]) for evaluating achieve-

ment motivation for learning in physical education. The

girls were also subjected to the International Physical

Fitness Test [4]. The data were processed by using the

step-down regression analysis, the level of p

≤0.05 being

considered significant.

Results

Pearson’s coefficients of correlation between the

achievement motivation and fitness test variables are

presented in Table 1. No significant correlations were

found between the general achievement motivation and

fitness variables and the same was true for two variables

(diligence and seriousness and competence of motor

activity) of AMPET. Most significant or nearly signifi-

cant correlations with fitness variables were found for

the “overcoming obstacles” variable, the next one being

value of learning. Anxiety about stress-causing situa-

tions and failure anxiety negatively correlated with some

fitness variables. Among the latter ones, most significant

or nearly significant correlations with the achievement

motivation variables were found for sit-ups, handgrip

and shuttle run.

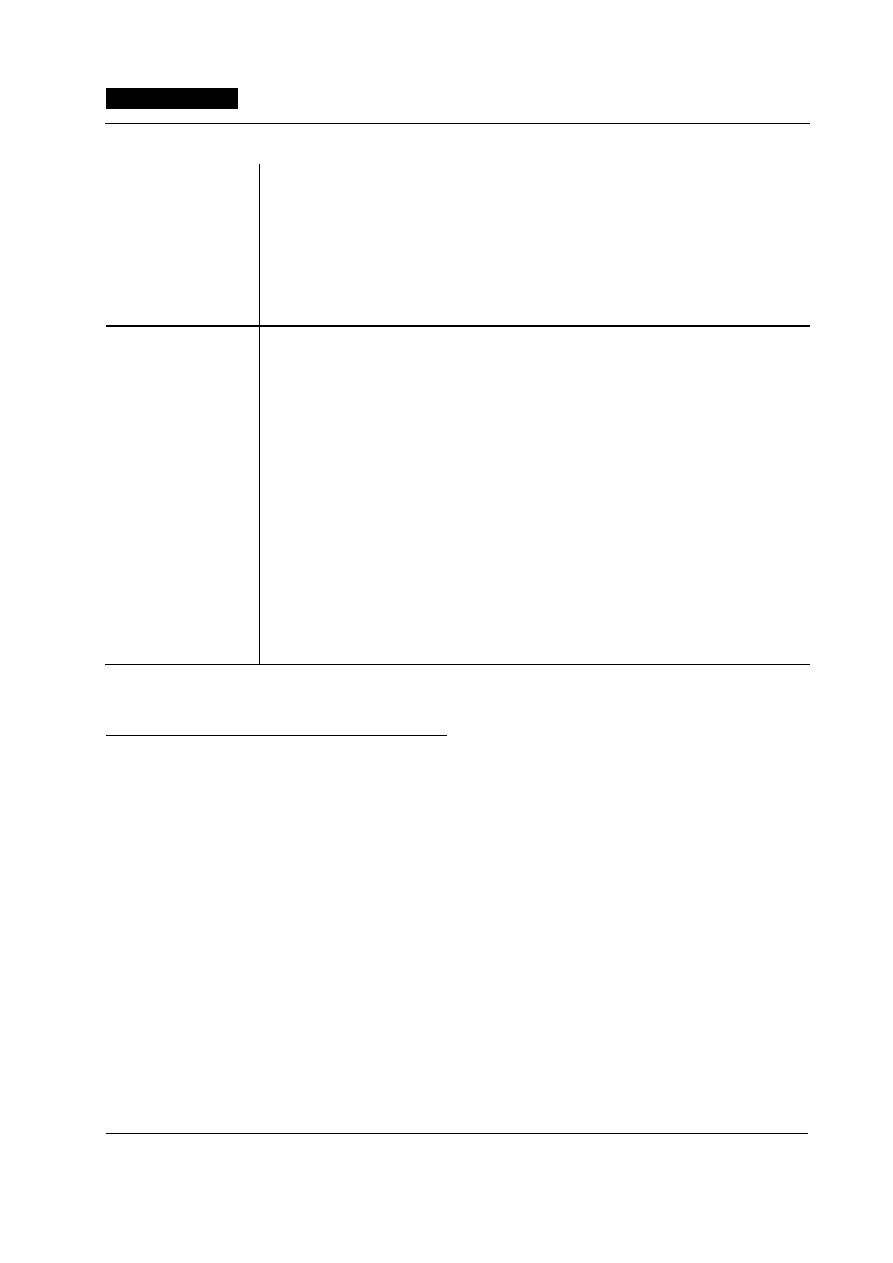

Table 1. Coefficients of correlations between the results of the International Physical Fitness Test and achievement

motivation dimensions in physical education determined in girls aged 15 years (n = 52)

50 m run

Standing

broad

jump

800 m

run Handgrip

Bent-arm

hang

Shuttle

run 4

×10

m

Sit-ups Sit-and-

reach

Total

Achievement motiv.

0.092

0.129

0.033

0.017

0.015

-0.034

0.014

-0.202

-0.023

Learning strategies

-0.159 -0.426** -0.202 0.307*

0.089 -0.063 0.007 -0.060 -0.057

Overcoming obstacles

0.255º 0.049

0.271º

0.241º

0.334*

0.424**

0.268º

0.150

0.399**

Pilność i od-

powiedzialność

-0.024 -0.163 0.140 0.214 0.229 0.159 0.200 -0.029 0.156

Perceived

competence

0.051 0.162 0.031 -0.025 0.106 0.150 0.008 -0.063 0.076

Wartość uczenia się 0.044 -0.057 0.089 0.255º

0.181 0.313* 0.304* 0.180 0.265

Lęk przed stresem

-0.058

0.021

-0.136

0.061

-0.182

0.147

-0.321*

0.115

-0.052

Lęk przed porażką -0.238º

-0.168

-0.293*

0.005

-0.239º

-0.105 -0.163 0.173

-0.190

º p<0.10; * p<0.05; ** p<0.01

The regression analysis revealed only one significant

(p = 0.03) predictor of general fitness, namely the “over-

coming obstacles” variable, which explained about 15%

of the total variance of physical fitness.

Discussion

As expected, significant or nearly significant relations

with fitness variables were revealed only for achievement

motivation for learning in physical education while the

general achievement motivation seemed to be useful only

to predict school- or job-related achievements but not

the fitness-related ones. Specific motivation components

(the need to compete and competition-related anxiety)

were detected in the sport area [3] and the significance

of striving for success, especially for the self-defined

objectives, was emphasised by those who studied moti-

vation during physical education classes [2,5,13,14].

In general, our results confirm the reliability of Ni-

shida’s model [10], as follows from the positive correla-

tions between the results of fitness tests and the indices

of success achievement, overcoming obstacles and value

of learning and from negative correlations with failure

avoidance indices (anxiety about stress-causing situations

and failure anxiety). The only exception was the index

of learning strategy, which correlated positively with the

results of handgrip and negatively with those of stand-

ing broad jump. This may suggest that that the learning

strategy mentioned in the questionnaire may promote

the outcomes of various motor tasks to a different degree.

22

M. Guszkowska, T. Rychta

The results of long-distance run, presumed to depend

on motivational factors [11] commonly regarded as an

indicator of endurance, proved uncorrelated with the

achievement motivation for learning in physical educa-

tion. The latter was rather associated with the results of

shuttle run and sit-ups, i.e. strength and agility skills,

although they contained also an endurance component.

The same was true for handgrip, a strength variable. All

these findings ought to be confirmed in studies involv-

ing a larger number of subjects as well as boys, in order

to detect possible gender-related differences in the re-

ported relationships.

This report may be regarded as a warning of regard-

ing the results of fitness tests attained by youths as sim-

ple indicators of their motor abilities. The results of all

fitness tests (also in the intellectual field) are condi-

tioned by various factors, the motivational ones playing

a significant role, as confirmed by the determination

coefficients recorded in this study. The coefficients of

correlation suggest that the predictive power of the di-

mensions of achievement motivation for learning in

physical education might be even higher when related

specific fitness tests.

References

1. Atkinson J. (1957) Motivational determinants of risk-

taking behavior. Psychol.Rev. 64:359-372.

2. Biddle S.J.H (2001) Enhancing motivation in physical

education. In: G.C.Roberts (ed.) Advances in Sport and Exer-

cise Motivation. Human Kinetics, Champaign IL, pp. 101-128.

3. Blecharz J. (2004) Motywacja jako podstawa sukcesu w

sporcie. In: M.Krawczyński, D.Nowicki (eds.) Psychologia Spor-

tu wTreningu Dzieci i Młodzieży. COS, Warszawa, pp. 59-72.

4. Bronikowski M., J. Maciaszek (2003) Test sprawności

fizycznej jako narzędzie kontroli i oceny w szkolnym procesie

dydaktycznym. Wychowanie Fizyczne i Zdrowotne 3:18-22.

5. Duda J.L., N.Ntoumanis (2003) Correlates of achieve-

ment goal orientations in physical education. Int.J.Educ.Res.

39:415-436.

6. Elliot A.J., D.E.Conroy (2005) Beyond the dichotomous

model of achievement goals in sport and exercise psychology.

Sport Exerc.Psychol.Rev. 1:17-25.

7. Elliot A., M.Covington (2001) Approach and avoidance

motivation. Educat.Psychol.Rev. 13:73-92.

8. Guszkowska M., T.Rychta (in press) Związki między

sprawnością fizyczną i cechami osobowości młodzieży.

9. Mroczyński Z. (1993) Sport i motywacja osiągnięć w

akademickiej edukacji wychowania fizycznego. AWF, Gdańsk.

10. Nishida T. (1988) Reliability and factor structure of the

Achievement Motivation in Physical Education Test. J.Sport

Exerc.Psychol. 10:418-430.

11. Przewęda R., J.Dobosz (2003) Kondycja fizyczna pol-

skiej młodzieży. AWF, Warszawa.

12. Spray C.M., C.K.J.Wang (2001) Goal orientations, self-

determination and pupils’ discipline in physical education.

J.Sports Sci. 19:903-913.

13. Standage M., J.L.Duda, J.Ntoumanis (2003) Predicting

motivational regulations in physical education: the interplay

between dispositional goal orientations, motivational climate,

and perceived competence. J.Sport Sci. 21:631-647.

14. Widerszal-Bazyl M. (1978) Kwestionariusz do mierzenia

motywu osiągnięć. Przegląd Psychologiczny. 31:355-353.

Received 16.01.2007

Accepted 16.02.2007

The study was supported by grant No. AWF-IV.81 of the

Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education

© Academy of Physical Education, Warsaw, Poland

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow(1)

2009 12 Metaprogramowanie algorytmy wykonywane w czasie kompilacji [Programowanie C C ]

Motywacja, metaprogramy

metaprogramy

Jezyk C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow cppmet

Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer

Toksykologia, egzamin pyt, - synteza metaproterenolu, sotalolu, chloramfenikolu (kilka pytań o różne

C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow(1)

Jezyk Cpp Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonów

Jezyk C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow cppmet

metaprogramy

C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow(1)

Jezyk C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow cppmet

Jezyk C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow

metaprogramy

Programming and Metaprogramming in THE HUMAN BIOCOMPUTER

Jezyk C Metaprogramowanie za pomoca szablonow 2

więcej podobnych podstron