Understanding Business Group Performance in an

Emerging Economy: Acquiring Resources and

Capabilities in Order to Prosper*

Daphne Yiu, Garry D. Bruton and Yuan Lu

Chinese University of Hong Kong; Texas Christian University; Chinese University of Hong Kong

The prevalent organizational form in most emerging markets is business

groups. These groups have typically been viewed through a transaction cost

economics perspective where they are perceived as responses to inefficiencies in the

market. However, the evidence to date on what generates a positive business group-

performance relationship in such environments is not well understood. This study

expands the understanding of business groups by employing the resource-based and

institutional theoretical perspectives to examine how groups acquire resources and

capabilities to prosper. The empirical evidence is based on over 224 business groups

in the emerging economy context of China and shows that most of the endowed

government resources do not help business groups to create a competitive edge.

Instead, those business groups with strategic actions to develop a unique portfolio of

market-oriented resources and capabilities are most likely to prosper. The results

provide critical insights on the relationship between the initiation of institutional

transformation and the desired outcome to be realized by organizational

transformation, thus enriching our understanding of institutions and strategic choices

facilitated or constrained by organizational resources in emerging economies.

INTRODUCTION

A business group is a collection of legally independent firms that are bound by

economic (such as ownership, financial, and commercial) and social (such as family,

kinship, and friendship) ties. This unique organizational form has significant eco-

nomic impact on emerging economies. For example, 40 per cent of Korea’s total

output was contributed by the top 30 business groups (Chang and Hong, 2000).

In China, business groups contributed close to 60 per cent of the nation’s indus-

trial output (China Economic Yearbook, 2000; China Statistical Yearbook, 2000). Despite

Journal of Management Studies 42:1 January 2005

0022-2380

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ ,

UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

Address for reprints: Daphne Yiu, Department of Management, Chinese University of Hong Kong,

Shatin, N. T., Hong Kong (dyiu@cuhk.edu.hk).

their significant contribution to the wealth of emerging economies, to date the

understanding of business groups has remained insufficient. Prior researchers have

examined business groups describing their founding (Keister, 1998), or the level of

diversification of business group firms in emerging economies (Khanna and

Palepu, 2000). However, researchers have largely treated business groups as a

unified set of businesses. The different factors that impact how business groups

seek to create value have been ignored.

In part, this absence of examination is due to the prior reliance on institutional

economics, in particular transaction cost economics, as the key theoretical per-

spective. From an economics perspective, business groups substitute for imperfect

market institutions in the emerging economies (Caves and Uekusa, 1976; Chang

and Choi, 1988; Khanna and Palepu, 1997, 2000; Wright et al., 2005; Leff, 1978).

Such a theoretical underpinning largely assumes that there is a uniform answer

on strategic choices made by business groups as they seek to lower transaction

costs. The limits imposed by a narrow theoretical lens such as transaction cost

theory has led to other theoretical lens to emerge. The economic sociology per-

spective argues that resource scarcity in emerging economies forces organizations

to restrict activity to certain limited functions, which then requires exchange with

other organizations (Cook, 1977). As such, firms form into business groups through

repeated transactions and by factors such as geographic region, political party, eth-

nicity, kinship, or religion (Granovetter, 1994). The prevalent growth of business

groups in late economic development formed another view of business groups as

a way for the state to support, or secure support from, entrepreneurs (Amsden,

1989). Chang and Hong (2000) and Guillén (2000) examined business groups from

a resource based view, arguing that business groups add value to member firms by

pooling and distributing heterogeneous resources through related and unrelated

diversification. Taking an evolutionary perspective, recent studies have traced the

evolution of business groups in regard to pattern of diversification and organiza-

tional structure over time (Kim et al., 2004; Kock and Guillén, 2001).

While there have been a variety of theoretical perspectives of business groups,

institutional theory appears to be a relevant but under utilized theoretical lens for

the study of emerging economies, as does resource-based theory (Hoskisson et al.,

2000). Peng (2000a) advocated that research on emerging economies is conducive

for integration of institutional and resource-based theories. The use of other the-

oretical underpinnings for the examination of business groups has brought unique

insights, but there has been limited prior effort to examine these two theoretical

lenses together. Thus, we do not disagree with the transaction economics per-

spective that business groups serve to fill the institutional voids in emerging

economies and reduce transaction costs for member firms in the groups. However,

we believe a richer theoretical understanding that relates the development of firm’s

resource portfolio and the institutional transition process of the emerging

economies is needed.

184

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

In this study, we propose that the value-creating potential of a business group

is largely dependent on how business groups are able to acquire resources and gen-

erate capabilities necessary to prosper. Nonetheless, given the institutional reality

that the firms in transition economies are embedded in the old central controlled

economy, the value-creating potential of the business group will be constrained by

the endowed resources of that group. By integrating a resource-based view with

the institutional perspective, we argue that the values created by business groups

vary depending on the resources and capabilities the groups are able to obtain.

Specific research questions raised include: What is the role of the business group,

as an organizational form, in emerging economies undergoing institutional tran-

sition? And what factors account for the variations in business group performance?

By addressing these issues, we hope to provide a better understanding of busi-

ness groups in emerging economies. In particular, we offer several fresh insights

including a new perspective that views business groups as an instrument, instead

of a product, of institutional transition. Second, unlike past studies on business

groups that are anchored at the member firm level, this study analyses business

groups as wholes. Third, the study has captured the unique resource profile of

organizations at a stage of institutional transition, thus providing a deeper under-

standing on the complex structural reconfiguration process. Fourth, the empirical

evidence offers implications to managers and policy makers that business groups

can proactively seek to enhance their performance by developing a unique port-

folio through various strategic means.

To build this understanding, the manuscript will first provide the theoretical

foundations for the study from the institutional theory and resource-based per-

spectives. Next, our hypotheses are examined by both survey and archival data

from the largest 224 business groups in China. The manuscript concludes with a

discussion of the implications of the findings for the study of business groups and

businesses in emerging economies.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

Literature Review on Business Group Performance

Empirical evidence about the beneficial effects of business groups on economic

development via their effects on the member firm performance has remained

mixed (Aoki, 1982; Caves and Uekusa, 1976; Chang and Choi, 1988; Khanna and

Palepu, 2000; Leff, 1978; Stark, 1996). Some studies have shown that business

groups helped to create positive effects for member firms’ performance. For

example, Chang and Choi (1988) empirically showed that business groups with a

multidivisional structure that reduces transaction costs and provides economies of

scale and scope, for example, the Korean chaebols, result in superior performance.

Using panel data from 1988 to 1990 on China’s business groups, Keister (1998)

Business Group Performance

185

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

found that the presence and predominance of interlocking directorates and finance

companies in business groups improved the financial performance and productiv-

ity of member firms, and more centralized groups performed better than others.

Perotti and Gelfer (2001) also provided evidence that group members have higher

values of Tobin’s q than otherwise comparable independent firms in Russia.

On the other hand, there is also evidence that business groups result in a

negative impact on firm performance. Caves and Uekusa (1976) and Nakatani

(1984) both found a negative relationship between group membership and firm

performance in the Japanese keiretsu. The negative results may be due to the fact

that ‘interest payments passing to the banks may be a conduit for group-derived

rents’ (Caves and Uekusa, 1976, p. 78). Outside of Japan, Khanna and Yafeh

(1999) supported the negative relationship between group membership and firm

performance. In half of the ten emerging economies in their sample (e.g. Brazil,

India, Korea, Taiwan, Thailand), the inter-temporal variance of firm profitabil-

ity, measured by the ratio of operating returns to assets, was lower for group affil-

iates than non-group affiliates. These empirical results suggest that there is, indeed,

a cost of affiliating with business groups.

The mixed empirical findings on group-performance indicate that richer theo-

retical examinations that investigate other variables are needed to understand what

impacts business group performance. We approach this examination with a strate-

gic perspective that such groups have the ability to make strategic choices that

will impact their performance. Thus, rather than treating business groups being

uniform sets of firms with given characteristics, we view business groups as col-

lections of resources. It is the ability of business groups to configure different types

of resources to fit the emerging competitive environment that contributes to their

success.

Business Groups: A Resource-Based Perspective

One of the unique characteristics of the institutional change in emerging

economies is the simultaneous operation of market mechanisms and the presence

of the remaining state governance mechanisms (Stark, 1996). Child (1993) high-

lighted this issue when he argued that the key factor that delineates a market-based

system from that of a hierarchical system that characterized central planning is

the importance of strategic context. The emerging strategic context in the new

institutional environment implies that a firm’s resource portfolio and capabilities

derived from it will impose significant impacts on its strategic competitiveness.

From the resource-based perspective, it has been argued that a firm’s competitive

advantage is derived from unique bundles of resources that are difficult for com-

petitors to duplicate – either through imitation or substitution (Barney, 1991).

There have been prior examinations of business groups from a resource-based

view. Conceptualizing business group as a portfolio of heterogeneous resources,

186

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Chang and Hong (2000) pointed out that member firms not only enjoy the natural

benefits resulting from a multidivisional structure, but they can also benefit from

internal business transactions for the purpose of cross-subsidization. Guillén (2000)

suggested that firms and entrepreneurs, by having access to business groups, could

accumulate an inimitable capability to combine domestic and foreign resources to

enter industries more quickly and cost-effectively in emerging economies. While

finding support for the resource-based view, these studies did not examine a rich

set of potential resources and capabilities that could be acquired in order to

prosper. Also, these studies have not looked into the endowed resource condition

of a business group.

The initial formation of business groups have typically been induced by the gov-

ernment where they are located as a tool of fostering economic development, not

only as a product of those economic efforts. To illustrate, Guillén (1997) pointed

out that the growth of Korean business groups (chaebols) was in line with the gov-

ernment’s industrial policy and export-led growth strategy. Literature suggests that

government involvement has been particularly pertinent in the formation of busi-

ness groups in most emerging economies: Pakistan (White, 1974), Latin America

(Strachan, 1976), Indonesia (Schwartz, 1992), Korea (Chang and Choi, 1988;

Guillén, 2000), and China (Keister, 1998; Peng, 2001). Building on the close linkage

between business groups and government, we conceptualize business groups as an

instrument to facilitate organizational transformation – corporatization and legiti-

mization – during the institutional transition process in emergent economies.

Building on this theoretical conceptualization, we propose that there are two

different sources of the potential resources and capabilities that a business group

could acquire. The first type is endowed resources, which has not been extensively

studied. Many business groups in emergent markets were formed from formerly

state-owned enterprises and government bureaus that are already endowed with

a pool of government resources when they were transformed into business groups.

As such, administrative and ownership history of business groups that results from

their status as former government enterprises impacts group development (Keister,

1998). Once the business groups are formed, they have autonomy in pursuing dif-

ferent strategies to acquire resources and develop market capabilities in order to

enhance their strategic competitiveness. We call this second type of resources

‘acquired/developed resources’. Which source of resources would have the great-

est impact on group performance is not clear from the prior research. Therefore,

our focus in this study is to examine how these two types of resources impose

heterogeneous effects on group performance.

Business Groups: China

A key aspect of the Economic Reform in China that has been generating this

nation’s growth is the establishment of business groups. Over the last 15 years

Business Group Performance

187

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

business groups in China have grown from being non-existent to a point where

they contribute approximately 60 per cent of the nation’s industrial output (China

Economic Yearbook, 2000; China Statistical Yearbook, 2000). Business groups serve as the

primary economic engine for the development of the national and local economies

in China (Keister, 1998; Nolan, 2001). The reason that business groups have been

used by the government as a tool of economic reform is that China has needed

to move from a hierarchical system that typifies central planning to a market-based

system (Child, 1993). The Chinese government knew that without making sys-

tematic choices in this transition it could end up with the chaos as reflected in the

Russian transition. Therefore, the nation needed an intermediary institution that

would facilitate the enterprise reform and, thereby, the economic transition. The

solution was the encouragement of business group formation that would facilitate

the movement towards the market based system.

Consistent with their use as transitional institutions, today business groups in

China commonly include both publicly traded and government owned firms in

their portfolio of affiliated firms. Illustrative of the complexity of business groups

in China is Desay, a business group founded in 1983 that includes 25 affiliated

firms. Some of the affiliated firms have publicly traded stock and some do not.

These various business units compete in ten industries including electronics, tele-

phone equipment, audio and visual products, construction materials, and real

estate, and employ approximately 11,000 employees. Some of these business units

were assigned to the business group while the parent firm itself invested in, and

took control of, other member firms within the group. In summary, the gradual

institutional transition of China provides a natural experiment for us to examine

how bundles of endowed and newly developed resources in a business group affect

the group’s performance.

HYPOTHESES

As noted before, resources for the business group can be endowed or

acquired/developed. Those resources that are endowed are present in the group

from its initial founding, while those resources that are acquired/created come

from the business group’s efforts to create or obtain the resources. Each source of

resources will be reviewed in turn.

Endowed Resources

Group age. From an evolutionary perspective, the history of a firm reflects a dis-

tinctive bundle of critical resource, organizational skills and capabilities that have

been accumulated over time, which in turn, exerts significant influence on a firm’s

choice of growth strategies and organizational structure (Nelson and Winter, 1982;

Penrose, 1959). Thus, the longer the history of the group the greater will be the

188

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

member firm’s embeddedness in its institutional environment. This embeddedness

is particularly important in an emergent market where organizational legitimacy

comes with age (Ahlstrom and Bruton, 2001). Increased legitimacy can lead to

increased performance since the high levels of volatility that characterize emer-

gent markets can result in firms that do not have such legitimacy receiving less

consideration by many key stakeholders. However, the institutional transition that

characterizes emergent markets means that legitimacy gained in the previous insti-

tutional period may no longer be valid as the institutional context moves to a

market focus. As such, the specific bundle of core resources that were developed

in the past may transform themselves into organizational inertia when the exter-

nal environment is changing (Hannan and Freeman, 1984). Business groups that

have been developed for a longer time will accumulate more obsolete resources

that inhibit a firm’s strategic flexibility. In an emerging economy like China, older

groups are more likely to have inherited an attitude conforming to the socialist

mentality, thus having a lower level of risk taking and profit focus. The reform of

most emergent markets has been in place close to 15 years and the institutional

transition from a hierarchy focus to a market focus is in full force. Thus, we expect

that business groups that are older will perform worse than those that have formed

more recently.

Hypothesis 1: The age of a business group is negatively related to the perfor-

mance of the business group.

Government ownership. Due to a lack of exit mechanisms for the full ownership in

the external capital market, governments usually retain a large proportion of own-

ership shares in business groups. However, government, as an owner, tends to place

more emphasis on allocating the financial resources for non-profit goals such as

provisions for social welfare and employment opportunities, than for shareholder

value and profit maximization (Boycko et al., 1995). For example, one of the great

issues facing China today is the unemployment among workers as the economy is

restructured. Thus, government entities commonly wish to maximize employment

in those businesses in which they have control in an effort to limit the potential

negative effects of unemployment on its citizens while other shareholders want to

maximize shareholder value and firm profits. This setting is illustrative of the

simultaneous operation of the emerging market mechanisms and the presence of

the remaining state governance mechanisms (Stark, 1996).

The expectation that governments want to maintain employment levels rather

than create new resources and capabilities in the firm is consistent with the evi-

dence found by Andrews and Dowling (1998). Their research found that post-

privatization gains did not materialize for firms where the government held sig-

nificant shares after the privatization process. The focus on goals other than share-

holder value and profit maximization is in contrast to what is expected of business

Business Group Performance

189

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

groups with a purer market orientation that come from limited or no government

ownership. As a result, it could be expected that higher levels of government stock

ownership leads to lower performance in the business group since resources will

not be spent on developing new resources or capabilities as the group’s business

environment changes.

Hypothesis 2: The share of government ownership held in a business group is

negatively related to the performance of the business group.

Top management background. One of the key resources, which competitors cannot

duplicate, is the human resources of the group, particularly the leadership. It is

the recognition of the value of human resources, particularly that of the individ-

ual that leads a business, that inspired the upper-echelons perspective of man-

agement (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1990). The firm’s leadership, the theory

argues, pattern their strategic choices to match their view of the world, which in

turn determines firm performance (Hambrick and Mason, 1984).

Deciding whether and how to enact to the environment is determined by the

decision makers’ understanding of the situation and their motivation (Ocasio,

1997). When making such decisions in novel situations, decision makers apply the

repertoire of available issues and answers and relate areas of commonality with

past situations in the firm. Therefore, the background of the top management is

expected to significantly impact the strategic actions pursued and the resulting per-

formance of the business groups. During institutional upheavals, managers may

lack an understanding of what is needed to be successful since the environment

has changed and the transitioning environment is full of uncertainty (Roth and

Kostova, 2003). In the case of business groups, the top management of the group

often comes from the government unit that established the business group. Thus,

the pool of managers who previously worked in the government setting is lacking

the corporate mindsets and incentives to engage in market-oriented activities

and/or create the resources and capabilities for their changing environment. These

top managers may even lack the knowledge and skills necessary to employ cor-

rectly those resources and capabilities even if they are developed (Zahra et al.,

2000). As such, it could be expected that those business groups, where there is

greater dominance by the top management coming from government units, will

result in lower group performance.

Hypothesis 3: The number of top management who previously worked for the

government is negatively related to the performance of the business group.

Founding via transfer from industrial bureau. Group founding can have a similar

‘imprinting effect’ on the group’s approach to resource and capability develop-

ment (Stinchcombe, 1965). One of the focused efforts made by the government

190

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

to facilitate the institutional transition process is transforming state-owned enter-

prises or industrial bureaus into business groups with the goal of corporatization,

or market oriented firms like Western corporations.

There are two fundamentally different approaches used to form business groups

in China. The first occurred when a variety of firms, typically from a single gov-

ernment bureau, were transferred into a business group. In this setting member

firms that came together were often from very different industries with the only

consistent factor being the bureau that controlled them. In this setting, which

member was dominant typically was not clear. Instead, it was the founding bureau

that was the dominant power in the arrangement. As a result there could be a lack

of clear strategic direction, and in turn, a lack of clear focus on which resources

and capabilities to develop. The other means by which business groups are created

occurred when there was one dominant firm as the core of the business group.

This firm was typically a large firm, which other firms were assigned. A single firm

that is the foundation for the business group results in that firm having the

dominant role in deciding the strategic direction of the group.

There is relative greater difficulty in choosing, and then reconfiguring strategic

resources and capabilities, in a situation where the business group was founded by

transfers from government industrial bureaus. This is due to the fact that the split

leadership and highly unrelated diversification of the resulting group makes clear

strategic decision making and coordination more difficult. Also, such a ‘forced mar-

riage’ of firms into the business group may suggest a non-economic rationale for

resource combinations, resulting in a heavy social and financial burden on the

groups. This leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: Business groups that originated by transfers of businesses from gov-

ernment industrial bureaus will have lower performance.

Acquired/Developed Resources

Acquisition strategy. With the market being liberalized and developed, business

groups can act in a market fashion by identifying potential firms for the group and

pursing mergers and acquisitions of those firms. Alternatively, a business group

can found the desired businesses in a greenfield fashion where the desired firms

are created entrepreneurially by the business group themselves. Acquisition is the

quickest means for firms to acquire resources and capabilities available in the

market. Also, compared to groups that are transferred from government industrial

bureaus, acquisitions are likely to result in fewer integration difficulties and greater

synergies since acquisitions are undertaken voluntarily, and the business group is

clearly in a controlling position in selecting its member firms strategically.

Therefore, it is expected that acquisition strategy has a positive effect on group

performance.

Business Group Performance

191

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Hypothesis 5: Business groups that pursue more acquisitions will have higher

performance.

Internal capability development. According to Peng (2003), the capability needs of a

firm to have a competitive advantage will differ over the period of institutional

transition since the strategy choices and organizational constraints will vary as the

institutions change. The need for strategic fit for organizational success would indi-

cate that an organization that does not appreciate this need for changes as the

institutions change will eventually find itself obsolete (Zajac et al., 2000). One of

the advantages given to business groups is support from the government (Keister,

2000), which can initially be a source of success for business groups in emerging

economies. However, as the economy moves towards a market-based economy,

more transparent rules will be introduced, and the normative and cognitive pres-

sures for market-based competition given by start-up firms and foreign firms in

domestic and international markets will also increase (Peng, 2003). The result of

these changes is a significantly changed environment in which the strategic choices

and organizational constraints have changed. A business group that is relying on

institutional support by the government may find that it no longer fits with its new

environment.

Organizational change is typically very difficult for all organizations. This situa-

tion is accented in environments such as emergent economies where change occurs

in a very short period and the firms that relied on governmental support often

have dated physical equipment and uncompetitive product portfolio (Kornai,

1980). As a result, it could be expected that the better the fit the incumbent firms

have with the pre-transition institutional context, the more difficult it is for them

to successfully transform themselves (Peng, 2003) and reconfigure their resource

portfolio (Uhlenbruck et al., 2003). In contrast, those firms that did not rely on

government support, but instead focused on the development of market based

capabilities would be expected to prosper as the institutional transition proceeds.

Therefore, we propose that business groups that are able to develop strengths

in market-based capabilities will sustain competitiveness in the new environment.

These capabilities include technological capabilities to enhance efficiency and

continuous product development. Additionally, marketing capabilities that help

protect domestic firms in an emerging economy against entry by foreign firms will

also be critical (Hoskisson et al., 2000).

Hypothesis 6: Business groups that engage in more internal capability develop-

ment will have higher performance.

International diversification. Even when a business group acquires or develops

resources internally, sustainable competitive advantages may still not be guaran-

teed due to the fact that the strategic factor markets are, as yet, underdeveloped

192

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

in emerging economies. To create a bundle of unique resources and capabilities,

business groups may need to acquire resources outside their domestic boundary.

Makino et al. (2002) empirically supported that firms from less developed coun-

tries pursued strategic asset-seeking foreign direct investment with the intent to

acquire technology-based resources and skills in countries that are superior, or not

available in their home countries, will perform best. The international diversifica-

tion strategy allows firms to develop capabilities that assist them to compete more

successfully both internationally and domestically. Kobrin (1991) pointed out that

international diversification allows firms to get access to more diverse resources for

the development of innovation capabilities which is conducive to sustain com-

petitive advantages. This view is consistent with Hitt et al. (1997) who argued that

the complementarities between product diversification and international diversifi-

cation help a firm achieve economies of scale and scope to degrees unavailable

from either form of diversification alone. Given the diversified nature of business

groups, it is expected that international diversification leads to greater group

performance.

Hypothesis 7: Business groups that pursue more international diversification will

have higher performance.

METHODOLOGY

Sample and Data

Since there is a lack of consensus of what constitutes business groups in different

nations of the world, a single-country study appears to be a sensible first step to

understanding the more general issue of the business group’s nature worldwide

(Khanna and Rivkin, 2000). In this study, China was chosen as the empirical

setting. According to the official definition by the Chinese government, a business

group consists of legally independent entities that are partly or wholly owned by

a parent firm and registered as affiliated firms of that parent firm. One of the

biggest challenges of conducting empirical studies in China is data availability and

data validity. As such, we collected data with the help of China’s National Statis-

tics Bureau (CNSB) that is comparable to the Securities and Exchange Commis-

sion in the United States. Firms in China report a variety of information to the

CNSB annually and so participation and accuracy of the information provided by

the business group to the CNSB is required.

The accounting and financial information of this study, including the dependent

variable, is gathered from the official studies conducted by the CNSB annually. In

addition to this, we conducted two surveys which are independent of the CNSB’s

annual data collection efforts mentioned above. The archival survey data includes

mainly business group demographic variables such as the group characteristics and

Business Group Performance

193

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

degree of diversification. The chief accountants of the business groups reported

this data. The perceptual survey data concern qualitative evaluation of topics by

the chief executives in the sample business groups. The use of data from different

surveys filled out by different individuals lessened the possibility the common

method variance problem and reduced potential respondents’ bias. To further

ensure that common method variance did not pose significant inflation on the

results, we conducted Harman’s one-factor test as suggested by Podsakoff and

Organ (1986). The factor analysis showed that no single factor accounted for the

majority of the covariance in the independent and dependent variables.

In addition, the questionnaires were translated and back translated to eliminate

measurement errors due to language differences. Also, before launching the large-

scale distribution of the survey, a pilot study in which questionnaires tested by a

group of Chinese managers was conducted. Finally, during the full-scale data col-

lection, the local branches of the CNSB were in charge of distributing and col-

lecting the survey data while the Beijing headquarters was in charge of auditing

the data collection process and conducting follow-up phone interviews to validate

the information reported by the business groups. The surveys were distributed in

December 1998 and collected by February 1999.

We selected the largest 250 business groups in our study. The larger-sized busi-

ness groups are selected because they are most likely the engines for economic

growth while having greater government involvement according to Chinese gov-

ernment policy of ‘grasping the big enterprises and letting go of smaller ones’.

Also, larger-sized business groups are likely to have member firms that are restruc-

tured state-owned enterprises. To allow for effects of our independent variables to

be evident, we dropped business groups founded less than a year ago. After delet-

ing cases with missing information, the final sample size is 224.

Measures

Dependent Variable

Business group’s performance. The performance of business groups is measured by

return of assets (ROA) as of 1998. The performance measure is taken from a

separate source, the Business Group Enterprise Survey, which the business groups

are required to report to the State Statistics Bureau annually.

Independent Variables

Age of business group. The age of business group refers to the length of years since

the founding of the business group.

Government ownership. Government ownership is defined by the percentage of shares

owned by the government in the business groups.

194

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Number of previous government officials. This is measured by the total number of man-

agers, including CEO and divisional managers at the group headquarters, who

worked in the government before. This number is then weighted by number of

employees to indicate the level of intensity.

Founding dummy – transfer from industrial bureau. Taken from the perceptual survey,

this is a dummy variable such that a value of 1 indicates the business group was

transferred from a previous government industrial bureau and 0 indicates

otherwise.

Acquisition intensity. Acquisition intensity is measured by the percentage of acquisi-

tion expenditure on total sales.

Internal capability development. As mentioned previously, three types of firm capabil-

ities – technological, product, and marketing capabilities – are critical to meet the

emerging competitive environment in an emerging economy. Investment in equip-

ment serves as a vehicle for technological improvements, as new ideas would lie

fallow without the embodiment in new equipment. This is also important for

greater efficiency and capacity utilization rate. R&D expenditure is a major pre-

dictor of a firm’s involvement in innovative activities, which is a key factor for

sustaining competitiveness. Finally, marketing expenditures are important in an

emerging economy where distribution and market channels are not well estab-

lished. Therefore, the internal capability development scale consists of three items:

(1) investments on equipment; (2) R&D expenditures; and (3) marketing expendi-

tures. The three items were measured by a seven-point scale ranging from 1

(decreased) to 7 (increased) over the past three years in the perceptual survey. The

three items were loaded on the same factor in the factor analysis with factor load-

ings ranging from 0.80 to 0.91. The Cronbach’s alpha of the measure was 0.81.

International diversification. This is measured by the number of countries in which

the business groups have foreign direct investment. The scope measure is a

measure of the breadth or scope of international operations, and this is a better

measure of the amount of location-specific advantages resulted from international

diversification (Tallman and Li, 1996).

Control Variables

Four control variables are included. According to the resource-based literature

(Penrose, 1959), the growth and expansion decision of a firm is determined by

internal factors that define the constraints and opportunities placed on the firm.

Therefore, we include size and current ratio to control for slack resources avail-

able for firm’s acquisition, product innovations, and diversification (Chang, 1996;

Business Group Performance

195

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Chatterjee and Singh, 1999; Hitt et al., 1996; Schoenecker and Cooper, 1998).

Firm size is measured by the logarithms of number of employees. Current ratio

is measured by total assets divided by total equity. Besides, group diversification is

controlled. Group diversification is measured by the four-digit entropy measure.

The entropy measure is computed according to Palepu (1985):

where Pi stands for the percentage of a member firm’s sales revenue in i industry.

Finally, the context of an emerging economy is characterized by gradual market

liberation. That means, some industries are still fully protected by government

while others are gradually opened for market competition. As a result, industry

competitiveness is controlled for. We created an industry competitiveness index of

a business group, which indicates the extent of market competitiveness of the

industries where the member firms are located. This is computed as follows. First,

following the China Industry Development Report (1999), we measured the extent of

market competitiveness of the industry in which each of the member firms is

located. A value of 1 indicates that the industry is having state monopoly, a value

of 2 refers to an industry that is semi-opened, and 3 for industry that is fully

opened. Then, the industry competitiveness index of a business group is computed

by summing up the market competitiveness score of each member firm weighted

by its total sales.

RESULTS

Table I presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables

included in this study. We checked the variance inflation factors (VIFs) to assess if

multicollinearity is a problem and the results indicated that multicollinearity does

not pose a problem to our results. To mitigate the potential threat of heterokes-

dascity, we estimated the OLS regressions using Huber-White’s robust standard

error which has been previously used in extant research on business groups (Chang,

2003; Khanna and Palepu, 2000). To test our hypotheses, control variables were

first entered in Model 1, with independent variables regarding the sets of endowed

resources and developed resources inserted in Model 2 and Model 3 respectively.

Model 4 represents the full model. Finally, recent literature on product diversifi-

cation has highlighted that diversification is a choice variable that is endogenous

and self-selected (see Campa and Kedia, 2002 for details) and the endogeneity

issue may apply in the relationship between international diversification and per-

formance. To control for the endogeneity of the international diversification deci-

sion, we performed a two-step Heckman test and the results are shown in Model

5. Table II presents the regression results.

DT

Pi

Pi

i

i

N

=

Ê

Ë

ˆ

¯

=

=

Â

ln

1

1, 2, 3,

M

1

,

. . . ,

196

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Business Gr

oup P

erf

or

mance

197

© Blackw

ell Pub

lishing Ltd 2005

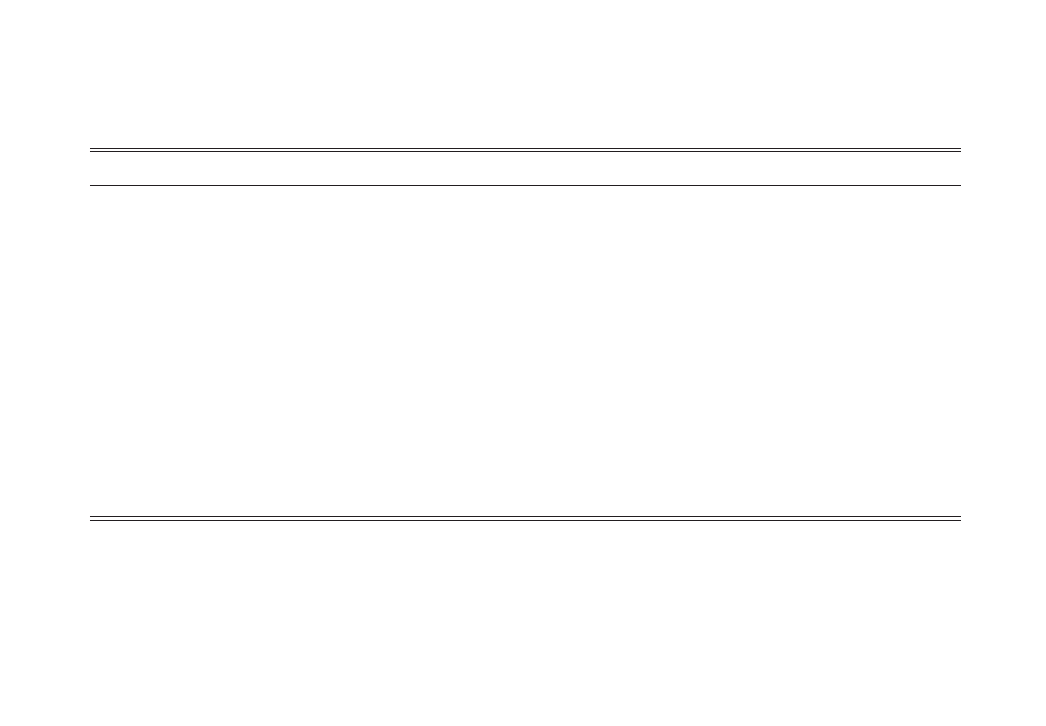

Table I. Descriptive statistics and correlations

Variables

Mean

S.D.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

1. Performance: ROA

0.018

0.0349

2. Group age

5.370

3.559

-0.079

3. Top management

0.037

0.084

-0.080

0.029

background

4. Government 0.738

0.322

-0.300**

-0.223**

-0.069

ownership

5. Group transferred

0.170

0.376

-0.047

0.107

-0.055

-0.001

from govt bureau

6. Acquisition to

4.851

12.766

0.147*

-0.088

-0.067

-0.110

-0.144*

sales (%)

7. Internal capability

5.149

1.323

0.324**

-0.075

-0.138*

-0.077

-0.006

0.041

development

8. International 4.660

13.459

0.019

0.073

0.016

0.087

0.013

-0.084

-0.097

diversification

9. Log of employees

9.534

1.276

-0.140*

0.045

-0.487**

0.127

0.322**

-0.047

-0.087

0.164*

10. Current ratio

1.879

0.898

0.291**

-0.004

-0.086

-0.256**

-0.092

-0.006

0.128

-0.094

-0.046

11. Group entropy

0.820

0.489

-0.021

0.223**

0.010

-0.112

0.195**

-0.058

-0.027

0.040

0.142*

-0.031

12. Industry 1.905

0.677

0.110

0.016

-0.201**

0.068

-0.100

0.016

0.063

0.026

0.152*

-0.063

0.025

competitiveness

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

N = 224.

198

D

.

Y

iu et al.

© Blackw

ell Pub

lishing Ltd 2005

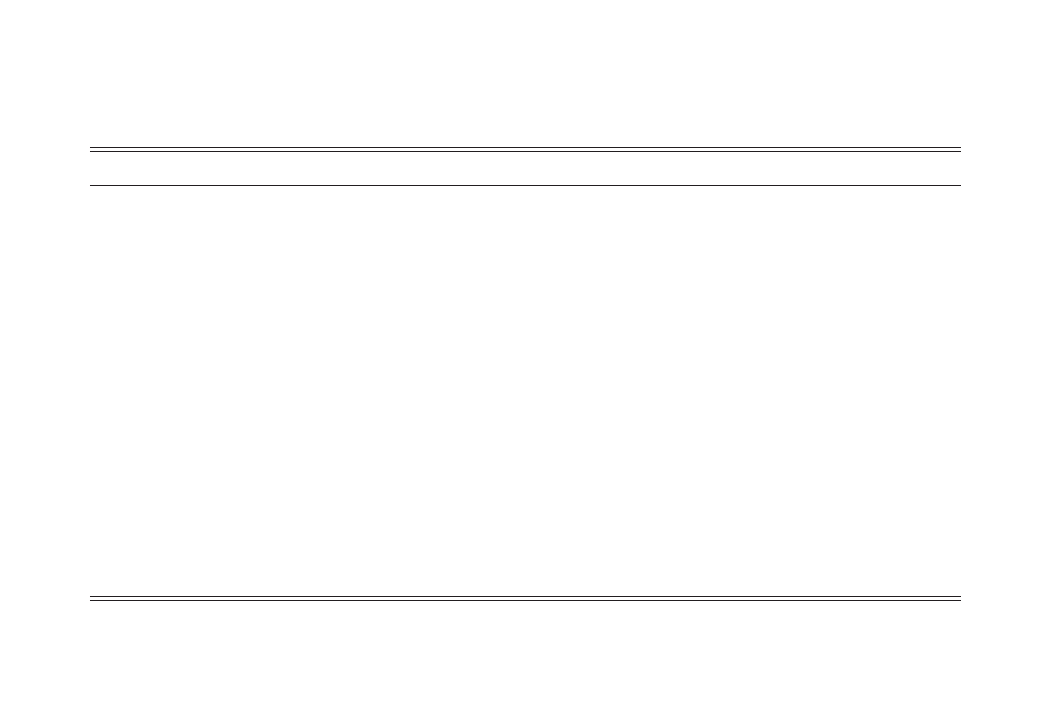

Table II. Regression results on business group resources and group performance

Dependent variable: Return on assets

Predicted sign

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

Model 4

Model 5

Control variables

Number of employees (ln)

-0.151* (0.002)

-0.201** (0.002)

-0.130* (0.002)

-0.176** (0.002)

-0.331***

Current ratio

0.294*** (0.003)

0.215** (0.003)

0.270*** (0.003)

0.207** (0.003)

-0.221**

Group diversification

0.006 (0.005)

0.000 (0.004)

0.013 (0.004)

0.001 (0.004)

-0.010

Industry competitiveness

0.151* (0.003)

0.152** (0.003)

0.124* (0.003)

0.135* (0.003)

0.106

†

Independent variables

Endowed resources via

Group history (age)

-

-0.134* (0.001)

-0.114* (0.001)

-0.134**

Government ownership

-

-0.270*** (0.009)

-0.247** (0.009)

-0.234***

Number of previous government

-

-0.141* (0.021)

-0.093

†

(0.019)

-0.125**

officials in top management

Groups transferred from

-

0.059 (0.006)

0.064 (0.006)

0.063

industrial bureau

Acquired resources via

Acquisition

+

0.137

†

(0.000)

0.105

†

(0.000)

0.086

†

Internal capability development

+

0.273*** (0.002)

0.241** (0.002)

0.224***

International diversification

+

0.099* (0.000)

0.126* (0.000)

1.497*

Correction for self-selection (

l)

-0.846**

R-square

0.12

0.21

0.22

0.28

c

2

(df ) = 82.82 (13)

Adjusted R-square

0.11

0.18

0.20

0.25

R-square change

0.12

0.09

0.10

0.16

Model F statistics

7.68***

7.04***

8.73***

7.61***

F statistics for change

7.68***

5.74***

7.09***

6.77***

N = 224. Standardized coefficients, and robust standard errors in parentheses, are reported. Robust standard errors were not presented with the two-step option.

†

p < 0.10, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Overall, all the models had strong model significance (p < 0.001 for the F-

statistics) and the R

2

s showed that the models explained a significant amount of

the dependent variable. Also, the change in R

2

of the hierarchical regression

models indicated that group’s developed resources had slightly greater incremen-

tal variance explained, compared to the endowed resources. This indicated the

increasing importance of self-developed market oriented resources in emerging

economies compared to the historical resources endowed from the pre-transition

period.

Results of the hypotheses tests include support for the fact that the age of a

business group is negatively related to its overall group performance (Hypothesis

1). In Model 2 of Table II, the coefficient of group age is negative and statistically

significant (p < 0.05). Hypothesis 2 predicts that there is a negative relationship

between government ownership and group performance. The findings show that

the coefficient is negative and statistically significant (p < 0.001). Hypothesis 2 is

strongly supported. Hypothesis 3 predicts that business groups with more CEO

and managers who previously worked in government have lower performance. As

shown in Model 2, the coefficient of CEO and managers with government expe-

rience is statistically significant at the 0.05 level, but it becomes weaker in the full

model (p < 0.10). As such, Hypothesis 3 is moderately supported. The last hypoth-

esis on endowed resources is that business groups that are transferred from gov-

ernment industrial bureaus perform worse than business groups that are not.

However, the coefficient is not statistically significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is

not supported.

With regard to the set of hypotheses on group’s acquired/developed resources,

Hypothesis 5 predicts that business groups that pursue more acquisitions will

perform better. As shown in Model 3, acquisition intensity has a positive relation-

ship with group performance (p < 0.10). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is marginally

supported. Hypothesis 6 predicts that internal capability development is positively

related to performance of a business group. There is strong support for this hypoth-

esis as the coefficient is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001). Finally,

Hypothesis 7 predicts that there is a positive relationship between international

diversification and business group performance. The findings show that the coef-

ficient of international diversification is statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

Thus, Hypothesis 7 is supported.

Model 5 presents the results with the correction of the endogenous effects of

international diversification on performance. Following Heckman (1979), we

employed a two-stage estimation of the endogenous self-selection model, also

referred to as the treatment model (Greene, 1993). This approach for accounting

for endogeneity is adopted in previous studies such as Campa and Kedia (2002)

and Shaver (1998). We first recoded the international diversification into a binary

choice variable and regressed it by firm attributes including firm size and current

ratio, and industry competitiveness. Then, we ran the full model (Model 4) again

Business Group Performance

199

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

by replacing the international diversification variable with the probit estimates of

the probability to enter foreign countries obtained in the first step. As shown in

Model 5, the endogeneity problem is evidenced as the coefficient of

l, the self-

selection parameter, is negative and statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The

coefficient of international diversification, after correcting for the selection bias,

still has a positive and significant effect on group performance (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we conceptualized business groups as the instrument, not only the

product, of institutional transition. Organizations are assigned the role of being

the agents of transformation. By taking this approach and building on the insti-

tutional and resource-based theories, the present study provides an opportunity to

examine the relationship between organizational resource portfolio and institu-

tional transition.

Endowed Resources

Business groups have a pool of mixed resources at a stage of institutional transi-

tion as old transitions fade away and new market institutions come into place. In

such settings, the endowed resources from the pre-transition period may become

a burden for business groups. The significance of the age variable in a negative

direction indicates that the more embedded the group is in the planned economy

the more likely that its performance will go down. It is easier and quicker for

younger groups to configure a new portfolio of resources that allows them greater

strategic flexibility to pursue different strategies for the new environment.

Frequently it is assumed that the key resource with which a business group needs

to be endowed is relations with key government authorities. The extensive writ-

ings on guanxi, or connections, in business in China are consistent with this per-

spective (cf. Tsang and Walls, 1998). Also, past literature stressed the importance

of the government as a resource provider to business groups. Granovetter (1994)

stated that the relations between governments and business groups are central in

shaping the business group’s ownership, authority structure, and relations of

groups to financial institutions. However, the evidence presented here calls these

beliefs into question.

Government ownership has great governance implications on group perfor-

mance. As the dominant owner of the group, government can control the use of

resources of a business group. For example, the association with the government

introduces forces into the strategic decision making of the firm that may not be

focused on profit maximization (Zhu, 1998). Also, the persistent dominance of gov-

ernment ownership in large firms such as business groups may indicate that the

200

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

accumulated unproductive resources in government-owned firms make them

difficult to attract alternative owners. This, again, highlights the urgency for

government-owned firms to reconfigure their resource portfolios as what is called

in this study. Diffused ownership may come after a competitive resource pool is

created in a firm.

Top management positions held by previous government officials can be a lia-

bility. A great challenge faced by former socialist managers and government offi-

cials is to understand and accept a new cognitive framework for doing business

and management (Child, 1993). Paradoxically, it is the uncertainty of the institu-

tional transition process itself that made managers incline to stick to the old rules

with which they are familiar. The environment has changed but the cognitive

mindsets of top management have not. Thus, it appears that ‘cognitive processes

must be put in place that are the reverse of those that led to institutionalization

in the first place’ (Johnson et al., 2000, p. 576).

However, the relationship between business groups that are transferred from

previous government industrial bureau and group performance was not statisti-

cally significant. The insignificance may be due to the strong normative pressure

of the previous institutional environment that gave rise to isomorphic organiza-

tional patterns under the hierarchical system (Child, 1993). As such, whether

groups are transferred from the government bureaus may not impose significant

heterogonous imprinting effects on firms. Alternatively, the insignificant relation-

ship may be because such a relationship is not a direct relationship but one medi-

ated by other factors such as restructuring efforts made after group formation. For

instance, the Shougang Group, one of the four core players in China’s steel indus-

try, was merged from 13 industrial ministries and became one of the largest

business groups in China. After the group formation, the Shougang Group

implemented a series of ‘catch-up’ actions, including divesting loss-making non-

core businesses, downsizing the core business slowly, raising capital in the stock

market, and generating resources for upgrading technology (Nolan and Yeung,

2001). Thus, restructuring efforts made by the group may be a mediating factor

on the relationship between group founding and performance. Future research

may explore this mediating relationship.

Acquired/Developed Resources

Prior research has tended to view business groups as uniform groups of entities.

The evidence here is that business groups can take significant steps to help their

performance after their initial formation. Those business groups that have proac-

tively sought to develop capabilities through acquisitions, internal development, or

international diversification result in better group performance. Among the three

means of resource acquisition, the findings showed that self-developed resources

have the strongest effect while the effect of acquisition is marginal.

Business Group Performance

201

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

The prominence of self-developed resources rather than acquired resources may

be due to the fact that the market for acquisition is still developing in an emergent

economy like China, and so the best potential acquisition firms do not come onto

the market. Second, back to the core argument of the resource-based view, capa-

bilities cannot be acquired. Compared to acquisition, longer-term horizon strate-

gies such as internal development and international diversification allow for a

greater depth and breadth of organizational learning and the generation of firm-

specific core competencies. The findings echo recent studies by Peng (2003) which

demonstrated that the pressures for firms to build competitive-based capabilities

are increasing when the economy is transitioning towards a more transactional

type economy.

Comparing the results of developed resources to those of endowed resources,

the present study supports the belief that the benefits given by networks are grad-

ually eclipsed by the growing importance of organizational capabilities as the

economy transits towards a market-based economy (Hoskisson et al., 2000; Peng,

2003). Besides, an implication drawn from the empirical findings of this study is

that a key constraint of institutional transition in emerging economies is that strate-

gic change may be hindered by the structural properties and the resource port-

folio of the firms. Thus, firms that adapt and build strategic capacity will perform

the best.

Future Research Agenda

Future research should seek to expand the understanding of how business groups

manage their resources to create value. One specific area of potential investiga-

tion about such management of interdependencies is the nature of the coordina-

tion between the business group and its affiliated firms. The two levels of the

organization likely have very different perceptions of resources and the necessary

management of those resources. Future researchers should explore the interaction

between those two levels of the organization.

An alternative area of potential investigation is how business groups restructure

themselves. For example, in China business groups found that success in the

domestic market was very easy. However, now there are large numbers of both

domestic and international competitors. The entry of China into the WTO will

only further intensify these competitive pressures. Thus, many business groups in

China today face the prospect of needing to restructure their businesses. The

ability to restructure those business groups that are performing poorly will become

a more critical issue in the future and merits investigation.

The evidence here is that relationships with government authorities are not a

positive, but a negative, impact on group performance. The most widely exam-

ined topic in China by researchers is the topic of guanxi, or connections among

parties. The evidence here calls into question the relevance of much of the prior

202

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

writings on guanxi without noting the changes in the institutional environment.

The development of greater transparency of accounting standards, advances in

the legal environment, and more consistent government regulation would be

expected to lead to lower needs for relationship based markets. Future research

should revisit how the importance of guanxi may be changing in this evolving

institutional environment.

The present findings are limited to a particular stage of the institutional tran-

sition process due to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Previously, Khanna

and Palepu (2000) found that the relationship between group diversification and

firm performance is curvilinear. In other words, the evolution of the institutional

context will alter the value-creating potential of business groups. Our results are

consistent with this finding. A longitudinal examination will allow a fuller picture

of business groups to be developed at different stages of the institutional transi-

tion process, and help to demonstrate that the institutional economics and

resource-based perspectives of business groups are complimentary with each other.

Also, the generalizability of our findings may be limited by the inclusion of busi-

ness groups in the sample only. Nonetheless, given that almost all major businesses

are part of a business group in the empirical context, China, it is debatable that

a comparable sample of independent firms could be located. Therefore, prospec-

tive research can analyse a broader sample consisting of independent firms and

business groups in other emerging economies.

Finally, the present findings provide insightful implications to policy makers in

emerging economies as business groups continue to be the focus of government’s

economic policies in these countries. It has been recognized in other settings that

the government in China does not have efficient control of its agents (Peng, 2000b).

Thus, effort by the government to encourage employment would not be expected

to produce the desired result. The political goal of maintaining employment is a

short-term benefit. The society will benefit more if, in the long run, business groups

become stronger and able to compete both domestically and internationally. Thus,

rather than focusing on political goals, it can be helpful for business groups to

develop resources and capabilities necessary to compete in a market economy.

NOTE

*The work described in this article was supported by research grants from the Earmarked Research

Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project No. CUHK4092/98H).

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, D. and Bruton, G. D. (2001). ‘Learning from successful local private firms in China: estab-

lishing legitimacy’. Academy of Management Executive, 15, 72–83.

Amsden, A. H. (1989). Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Business Group Performance

203

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Andrews, W. A. and Dowling, M. J. (1998). ‘Explaining performance changes in newly privatized

firms’. Journal of Management Studies, 35, 601–17.

Aoki, M. (1982). ‘Business groups in a market economy’. European Economic Review, 19, 53–70.

Barney, J. (1991). ‘Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage’. Journal of Management, 17,

99–120.

Boycko, M., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R. (1995). A Theory of Privatization. Mimeo. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University.

Campa, J. M. and Kedia, S. (2002). ‘Explaining the diversification discount’. Journal of Finance, 57,

1731–62.

Caves, R. and Uekusa, M. (1976). Industrial Organization in Japan. Washington, DC: Brookings

Institution.

Chang, S. J. (1996). ‘An evolutionary perspective on diversification and corporate restructuring: entry,

exit, and economic performance during 1981–89’. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 587–611.

Chang, S. J. (2003). ‘Ownership structure, expropriation, and performance of group-affiliated com-

panies in Korea’. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 238–53.

Chang, S. J. and Choi, U. (1988). ‘Strategy, structure, and performance of Korean business groups:

a transactions cost approach’. Journal of Industrial Economics, 37, 141–59.

Chang, S. J. and Hong, J. (2000). ‘Economic performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea:

intragroup resource sharing and internal business transactions’. Academy of Management Journal,

43, 429–48.

Chatterjee, S. and Singh, H. (1999). ‘Are tradeoffs inherent in diversification moves? A simultane-

ous model for type of diversification and mode of expansion decisions’. Management Science, 45,

25–41.

Child, J. (1993). ‘Society and enterprise between hierarchy and market’. In Child, J., Crozier, M.

and Mayntz, R. (Eds), Societal Change Between Market and Organization. Aldershot: Averbury,

203–26.

China Economic Yearbook (2000). Beijing: China Economic Yearbook Press.

China Industrial Development Report (1999). Beijing: Economics and Management Publishing.

China Statistical Yearbook (2000). Beijing: China Statistical Press.

Cook, K. S. (1977). ‘Exchange and power in networks of interorganizational relationships’. Sociologi-

cal Quarterly, 18, 62–82.

Finkelstein, S. and Hambrick, D. C. (1990). ‘Top management team tenure and organizational out-

comes: the moderating effect of managerial discretion’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35,

484–503.

Granovetter, M. (1994). ‘Business groups’. In Smelser, N. J. and Swedberg, R. (Eds), The Handbook of

Economic Sociology. New York: Russell Sage, 453–75.

Greene, W. H. (1993). Econometric Analysis, 2nd edition. New York: Macmillan.

Guillén, M. F. (1997). ‘Business groups in economic development’. Academy of Management Best Paper

Proceedings, Academy of Management Annual Meeting at Boston, USA, 170–4.

Guillén, M. F. (2000). ‘Business groups in emerging economies: a resource-based view’. Academy of

Management Journal, 43, 362–80.

Hambrick, D. C. and Mason, P. (1984). ‘Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top

managers’. Academy of Management Review, 9, 193–206.

Hannan, M. T. and Freeman, J. (1984). ‘Structural inertia and organizational change’. American

Sociological Review, 49, 149–64.

Heckman, J. (1979). ‘Sample selection bias as a specification error’. Econometrica, 47, 133–9.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., Johnson, R. A. and Moesel, D. (1996). ‘The market for corporate

control and firm innovation’. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 1084–109.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E. and Kim, H. (1997). ‘International diversification: effects on innovations

and firm performance on product-diversified firms’. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 767–98.

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M. and Wright, M. (2000). ‘Strategy in emerging economies’.

Academy of Management Journal, 43, 249–67.

Johnson, G., Smith, S. and Codling, B. (2000). ‘Microprocesses of institutional change in the context

of privatization’. Academy of Management Review, 25, 572–80.

Keister, L. A. (1998). ‘Engineering growth: business group structure and firm performance in China’s

transition economy’. American Journal of Sociology, 104, 404–40.

Keister, L. A. (2000). Chinese Business Groups: The Structure and Impact of Interfirm Relations During Eco-

nomic Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

204

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Khanna, T. and Palepu, K. (1997). ‘Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets’.

Harvard Business Review, 75, 41–51.

Khanna T. and Palepu, K. (2000). ‘The future of business groups in emerging markets: long-run

evidence from Chile’. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 268–85.

Khanna, T. and Rivkin, J. W. (2000). Ties That Bind Business Groups: Evidence from an Emerging Economy.

Mimeo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Khanna, T. and Yafeh, Y. (1999). Business Groups and Risk Sharing Around the World. Mimeo. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University.

Kim, H., Hoskisson, R. E., Tihanyi, L. and Hong, J. (2004). ‘The evolution and restructuring of

diversified business groups in emerging markets: the lessons from chaebols in Korea’. Asia Pacific

Journal of Management, 21, 25–48.

Kobrin, S. J. (1991). ‘An empirical analysis of the determinants of global integration’. Strategic Man-

agement Journal, 12, Special issue, 17–37.

Kock, C. J. and Guillén, M. (2001). ‘Strategy and structure in developing countries: business groups

as an evolutionary response to opportunities for unrelated diversification’. Industrial and Corpo-

rate Change, 10, 77–113.

Kornai, J. (1980). Economics of Shortage. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Leff, N. (1978). ‘Industrial organization and entrepreneurship in the developing countries: the eco-

nomic groups’. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 26, 661–75.

Makino, S., Lau, C. M. and Yeh, R. S. (2002). ‘Asset-exploitation versus asset-seeking: implications

for location choice of foreign direct investment from newly industrialized economies’. Journal of

International Business Studies, 33, 403–21.

Nakatani, I. (1984). ‘The role of financial corporate grouping’. In Aoki, M. (Ed.), Economic Analysis

of the Japanese Firm. New York: North-Holland.

Nelson, R. R. and Winter, S. G. (1982). En Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University.

Nolan, P. (2001). China and the Global Business Revolution. New York: Palgrave.

Nolan, P. and Yeung, G. (2001). ‘Large firms and catch up in a transition economy: the case of

Shougang Group in China’. Economics of Planning, 34, 159–78.

Ocasio, W. (1997). ‘Towards an attention-based view of the firm’. Strategic Management Journal,

Summer Special Issue, 18, 187–206.

Palepu, K. (1985). ‘Diversification strategy, profit performance, and the entropy measure’. Strategic

Management Journal, 6, 239–55.

Peng, M. W. (2000a). Business Strategies in Transition Economies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Peng, M. W. (2000b). ‘Controlling the foreign agent: how governments deal with multinationals in

a transition economy’. Management International Review, 40, 141–66.

Peng, M. W. (2001). ‘How entrepreneurs create wealth in transition economies’. Academy of Manage-

ment Executive, 15, 95–110.

Peng, M. W. (2003). ‘Institutional transition and strategic choices’. Academy of Management Review, 28,

275–96.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. New York: Wiley.

Perotti, E. C. and Gelfer, S. (2001). ‘Red barons or robber barons? Governance and investment in

Russian financial-industrial groups’. European Economic Review, 45, 1601–17.

Podsakoff, P. M. and Organ, D. W. (1986). ‘Self-reports in organizational research: problems and

prospects’. Journal of Management, 12, 531–44.

Roth, K. and Kostova, T. (2003). ‘Organizational coping with institutional upheaval in transition

economies’. Journal of World Business, 38, 314–30.

Schoenecker, T. S. and Cooper, A. C. (1998). ‘The role of firm resources and organizational attributes

in determining entry timing: a cross-industry study’. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 1127–2243.

Schwartz, A. (1992). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Shaver, J. M. (1998). ‘Accounting for endogeneity when assessing strategy performance: does entry

mode choice affect FDI survival?’. Management Science, 44, 571–85.

Stark, D. (1996). ‘Recombinant property in East European capitalism’. American Journal of Sociology,

101, 993–1027.

Strachan, H. W. (1976). Family and Other Business Groups in Economic Development: The Case of Nicaragua.

New York: Praeger.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). ‘Social structure and organizations’. In March, J. G. (Ed.), Handbook of

Organizations. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally, 142–93.

Business Group Performance

205

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Tallman, S. and Li, J. (1996). ‘Effects of international diversity and product diversity on the perfor-

mance of multinational firms’. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 179–96.

Tsang E. and Walls W. K. (1998). ‘Can guanxi be a source of competitive advantage for doing busi-

ness in China’. Academy of Management Executive, 12, 64–73.

Uhlenbruck, K., Meyer, K. and Hitt, M. A. (2003). ‘Organizational transformation in transition

economies: resource-based and organizational learning perspectives’. Journal of Management

Studies, 40, 257–82.

White, L. J. (1974). Industrial Concentration and Economic Power in Pakistan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., Hoskisson, R. E. and Peng, M. W. (2005). ‘Guest editor’s introduction:

Strategy research in emerging economies: Challenging the conventional wisdom’. Journal of

Management Studies, 42, 1, 1–33.

Zahra, S. A., Ireland, D. R., Gutierrez, I. and Hitt, M. A. (2000). ‘Privatization and entrepreneur-

ial transformation: emerging issues and a future research agenda’. Academy of Management Review,

25, 509–24.

Zajac, E., Kraatz, M. and Bresser, R. (2000). ‘Modeling the dynamics of strategic fit’. Strategic Man-

agement Journal, 21, 429–54.

Zhu, T. (1998). ‘Theory of contract and ownership choice in public enterprises under reformed

socialism: the case of China’s TVEs’. China Economic Review, 9, 59–72.

206

D. Yiu et al.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

business group affiliiation and firm performance in a transition economy a focus on ownership voids

business group structure and firm performance in china s transition economy

Iannace, Ianniello, Romano Room Acoustic Conditions Of Performers In An Old Opera House

Vinay B Kothari Executive Greed, Examining Business Failures that Contributed to the Economic Crisi

An agro economic analysis of willow cultivation in Poland 2006

capability creation and internationalization with business group embeddedness

Angielski tematy Performance appraisal and its role in business 1

business groups and social welfae in emerging markets

alesinassrn Ethnic diversity and economic performance

How to be an Effective Group Leader

Economics 5 BUSINESS ORGANISATION

Towards an understanding of the distinctive nature of translation studies

Performance Improvements in an arc welding power supply based on resonant inverters (1)

Augmented?M for an undersea virtual world

#0739 – Performing an Intervention

Sociology The Economy Of Power An Analytical Reading Of Michel Foucault I Al Amoudi

więcej podobnych podstron