This article was downloaded by: [Uniwersytet Warszawski]

On: 24 January 2014, At: 05:37

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:

1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street,

London W1T 3JH, UK

Scandinavian Journal of

History

Publication details, including instructions

for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/shis20

Missionary Activity in

Early Medieval Norway.

Strategy, Organization

and the Course of Events

Dagfinn Skre

Published online: 05 Nov 2010.

To cite this article: Dagfinn Skre (1998) Missionary Activity in Early Medieval

Norway. Strategy, Organization and the Course of Events, Scandinavian

Journal of History, 23:1-2, 1-19, DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03468759850115990

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of

all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications

on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our

licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as

to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of

the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication

are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views

of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified

with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be

liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs,

expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever

caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to

or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study

purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,

reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in

any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of

access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/page/

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

Missionary Activity in Early Medieval Norway.

Strategy, Organization and the Course of Events

Dagfinn Skre

One of the most elusive topics in the study of Norwegian medieval history is its

Christianization.

1

Earlier research on the subject was often heavily ideologized by a

nationalistic bias, as well as by Lutheran and Marxist anti-Catholic attitudes. More

recent research is somewhat relieved from this ideological bias. However, present-

day scholars wrestle with the vast complexity of this topic, and the close

interrelationship between Christianization and the other major changes in

Norwegian society that took place around the turn of the millennium. In Norway,

Christianization took place at a crucial stage in the period of the fundamental

transition of tribal societies into a kingdom.

To get a better grasp of the problems associated with Christianization, it is best

first to subdivide the subject up into smaller themes, and then to deal with each

separately. This approach has been successfully applied, especially in the last

decade, by several scholars.

2

In this paper, I follow this line of research,

Dagfinn Skre, born 1954, DPhil. Førsteamanuensis, is presently doing research on the Christianization of Scandinavia

and trade and ports in the Viking Age in the Department of Nordic Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Numismatics and

H istory of Arts, University of Oslo. His important publications include “Herredømmet. Bosetning og besittelse paÊ

Romerike 200–1350 e. K r.”, Acta Humaniora, nr. 32 (Oslo, 1998).

Address: University of Oslo, Frederiksgt. 3, N-0164 Oslo, Norway.

1

Early versions of this paper were presented 22 April 1996 at Middelaldersenteret, University of

Oslo, and at a conference in Levanger 25 April 1996 . The latter is published as D. Skre,

“Misjonsvirksomhet i praksis – organisasjon og maÊl”, Kultursamanhengar i M idt-Norden, Det K ongelige

N orske Videnskabers Selskab Skrifter, nr 1 (Trondheim, 1997). The paper has been revised as a

result of comments received on both occasions, and as a result of further research. English revised by

Dr. Roger Grace, University of Oslo.

2

For example, H. von Achen, “Den tidlige middelalderens krusifikser i Skandinavia. Hvitekrist som

en ny og større O din”, M øtet mellom hedendom og kristendom i Norge, edited by H.-E. Lide´n (Oslo, 1995);

C . Krag, “Kirkens forkynnelse i tidlig middelalder og nordmennenes kristendom”, in the same

volume; D. Skre, “Kirken før sognet. Den tidligste kirkeordningen i N orge”, in the same volume; G.

Steinsland, “Hvordan ble hedendommen utfordret og paÊvirket av kristendommen?”, in the same

volume; G. Steinsland, “Religionsskiftet i Norden – et dramatisk ideologiskifte”, M edeltidens fo¨delse,

edited by A. Andre´n (Lund, 1989); H.-E. Lide´n, “From pagan sanctuary to C hristian C hurch. The

excavation of Mære Church in Trøndelag. Comments. Reply to comments”, Norwegian Archaeological

Review, Vol. 2 (1969); P. Meulengracht Sørensen, “HaÊkon den Gode og guderne. Nogle

bemærkninger om religion og centralmagt i det tiende aÊrhundre – og om religion og kildekritik”,

H øvdingesamfund og kongemagt. Fra stamme til stat i Danmark, bd. 2. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter

22:2, edited by P. Mortensen and B. M. Rasmussen (AÊrhus, 1991); I. H. V. Mu¨ller, “Fra

ættefellesskap til sognefellesskap. Om overgangen fra hedensk til kristen gravskikk”, Nordisk

H edendom. Et symposium, edited by G. Steinsland, U. Drobin, J. Pentika¨inen and P. Meulengracht

Sørensen (Odense, 1991).

Scand. J. H istory 23

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

investigating the missionary activity of the Church. I hope to demonstrate that

focusing on the activity of the Church itself will make it easier to distinguish several

other aspects of the complex process of Christianization.

In analysing this complex matter it is necessary to make a distinction between the

two concepts “Christianization” and “conversion”, and this is the subject which I

confront first, while also sketching the main characteristics of Christian influence in

the period before the missionaries arrived in Norway. The second subject treated is

the Church’s vast experience in missionary work in the centuries preceding its

establishment in Norway. The Church, which started its work in Norway in the

10th century, had for several centuries undertaken missionary ventures among the

Germanic tribes. Missionary work in Norway was based on this extensive

experience, both in its strategy and organization. The third section concentrates on

the period of conversion, examining the evidence indicating that missionary work

was taking place at that time, and reviewing the main events in the process of

conversion. The relative importance of the different participants in the conversion,

the missionaries, the kings, and the aristocracy, is assessed. So are two theories on

the political role of the conversion: that the kings used conversion strategically to

undermine the authority of the old aristocracy, and that their main motive for

facilitating the conversion was to overcome the problems of ruling a religiously

heterogeneous kingdom. In the final section I will focus upon the organization of

the missionaries and the early Church.

1. Christianization and conversion

For several hundred years before the men of the Church appeared among the

Norse, the nearest Christian societies were found 500–600 km either to the south or

west of the coast of southern Norway. Through travels to the Christianized areas,

the Nordic peoples had become acquainted with the Christian faith, and with the

religious practices of the Christians. In some smaller segments of the population,

this familiarity with Christianity must have started as early as the 5th century, as

military bands from the north raided and plundered the Christianized areas, and

occasionally served in the armies of Christian kings and nobles. Long-lasting

friendly contacts were established between aristocratic families, and both goods and

marriage partners were exchanged between the Norse and the Christianized

regions. The Viking Age is often portrayed as the period when the Nordic peoples

broke out of their cultural isolation, but this is inaccurate: the aristocratic segment

of the Norse population was well acquainted with the English and Continental

cultures from the days of the Roman Empire onwards.

3

One of the institutions they

had become acquainted with was the Christian Church.

3

See, for example, G. Rausing, “Barbarian mercenaries or Roman citizens?”, Fornva¨nnen, Vol. 82

(1987); M. Axboe, “Guld og guder i folkevandringstiden. Brakteaterne som kilde til politisk/religiøse

forhold”, Samfundsorganisation og Regional Variation. Norden i romersk jernalder og folkevandringstid, Jysk

Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter, Vol. 27, edited by C. Fabech and J. Ringtved (AÊrhus, 1991); L.

Hedeager and H. Tvarnø, Romerne og Germanerne, Det europæiske hus, Vol. 2 (København, 1991); B.

M yhre, “Rogaland forut for Hafrsfjordslaget”, Rikssamlingen og Harald HaÊrfagre. Historisk seminar paÊ

Karmøy 10 og 11 juni 1993 (Karmøy, 1994).

Scand. J. History 23

2

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

The first phase of the long process of Christianization was familiarization with

the Church and Christian practices. At this early stage, Christianity was not

adopted by the Norse, but evidence indicates that their own cult was influenced by

it. In the 6th century, there was a new development in the pagan cult in

Scandinavia, as the cult no longer seems to have been a common affair for all free

men. It was now much more closely attached to the aristocratic families, their

farms, and the central occasions in an aristocrat’s life, like birth, marriage and

death.

4

This development may very well have been inspired by the close connection

between the nobles and the Church in the Christian Merovingian Empire. At this

time, several Merovingian nobles founded monasteries on their estates, and

established close personal ties to the clerics.

5

This development and the strength

gained from the alliance between worldly and secular power were, of course,

observed by their friends from the north. Their own cult seems to have changed as

a result of this influence.

On this basis, the earliest influences of Christianity on the Norse can be said to

have started in the later Migration Period, that is, the 6th century. However, at this

early stage, familiarity with Christianity was certainly confined to a small segment

of the population, and its influence to certain aspects of the pagan cult. Through

the centuries contact gradually increased, and in the Viking Age, that is, the 9th,

10th and early 11th centuries, most of the Norse population had heard of this

religion found in the south and the west, of their single God, and of their

magnificent churches and monasteries.

The process of Christianization continued until some time around the end of the

11th century, at which time the Christian faith and conception of man prevailed in

the cosmology and lives of the Norwegian population. By that time, a few

generations had been brought up in a society practising the Christian religion, they

knew the basic prayers, and they had learned to understand and participate in the

mass.

This 500-year-long process of Christianization was anything but a steady and

continuous process. There was a decisive change when groups within Norwegian

society actually began practising the new religion. As I will discuss in a moment, this

change seems to have started some time around the middle or in the first half of the

10th century, and continued through the first three decades of the 11th century.

There is, I will argue, a possibility that the process started as early as the late 9th

century.

This is the time of the conversion, when pagan practice was gradually abandoned,

and ultimately forbidden by law. In the Norse tongue the conversion is called

sidarskipti, or “the change of custom, or usage”. In this period, self-awareness in

Norse society changed from essentially pagan to predominantly Christian. The

Christian faith was no longer alien and vaguely familiar, but had become the very

fundament of religious practice for an increasingly large portion of Norwegian

society.

4

C . Fabech, “Samfundsorganisation, religiøse ceremonier og regional variation”, Samfundsorganisation

og Regional Variation. Norden i romersk jernalder og folkevandringstid, Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter, Vol.

27, edited by C. Fabech and J. Ringtved (AÊrhus, 1991).

5

J. M . W allace-Hadrill, The Frankish Church (Oxford, 1983), pp. 55–60.

Scand. J. H istory 23

Missionary Activity in E arly Medieval N orway

3

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

What then is the relationship between my main interest in this paper, missionary

activity, and these two processes, the long Christianization and the more rapid

conversion? Familiarity with the Christian religion gained before the conversion

was a component in a more general cultural exchange between Norse and

Christian societies. This early Christianization did not require the efforts of

missionaries to take place. But when groups in Norse society started abandoning

pagan practices, and instead began to baptise their children and bury their dead

according to the Christian rites, clerics had to be present. Their more or less regular

ministry is necessary for a population to be able to practice a Christian way of life.

This means that when the conversion of the Norse first began, when groups in

society first abandoned the pagan cult and acquired the Christian one, missionaries

were working more or less permanently among them. The efforts of the clerics must

be characterized as missionary work until the process of Christianization was

completed, which, as I mentioned, occurred by the end of the 11th century.

2. The missionary strategy of the Early Medieval Church

In Antiquity, the Church was an institution “of and for” the Romans. Missionary

work in an alien culture such as the Germanic tribes was unthinkable. Christianity

was for the civilized, and the civilized were the Romans. But when the Roman

Empire collapsed, and Germanic tribes invaded its territories, the Church had to

adapt to radically new conditions, and to cultural and political heterogeneity.

6

The dependence of the Church on Roman culture was replaced by the

conviction that all men, regardless of their culture and way of life, should be

Christian. Consequently, Christendom expanded to include the Germanic areas,

particularly in the Carolingian period. The overall strategy of the Church was

simple: to enable the missionaries to work in a secure environment, they needed the

support of sympathetic rulers. So, in the initial phase, priests and monks attempted

to convert the powerful, kings and noblemen. When this was accomplished, the

conversion of the whole society began, by introducing new laws and regulations,

and by teaching and caring for the population.

7

In some instances the powerful were made to accept the new faith by force. This

was, for instance, the case with the Avars and Saxons, who fell victims of the

Carolingian expansion, and were subsequently converted. Most Christian writers

applauded this approach, and held that paganism deserved no other treatment than

force by the sword. But it was also recognized that this kind of conversion did not

create the best situation for inner acceptance of the faith, which was the ultimate

goal of the missionaries.

8

6

J. M . W allace-Hadrill, op. cit., p. 143.

7

J. M . W allace-Hadrill, op. cit., p. 24.

8

R. E. Sullivan, “C arolingian missionary theories”, The Catholic H istorical Review, Vol. 42, (1956), pp.

277–278.

Scand. J. History 23

4

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

In cases of forced conversion, the missionaries started their work by teaching the

fundamental truths of the Christian faith.

9

But missionary ventures were also

undertaken by small groups of missionaries travelling into pagan lands. These

missionaries had to take a different approach. In order to persuade the powerful

kings and noblemen to accept the new religion, the Church had to present a God

and a faith which were acceptable to the kings and princes, to their warrior

aristocracy, and to the general population. Furthermore, the presentation of

Christianity had to be carried out in such a way as to ease the change, which had to

be as unnoticeable as possible. Neither the kings nor the aristocracy wanted an

overt change, and they were definitely not interested in any religious revolution.

This would only have reduced confidence in the aristocracy, and increased the

possibility of social upheaval. The Church had to present the new God as being

much the same as the old ones, only better.

One of the central elements in Germanic pagan religion was that the noblemen,

and in particular the king, were the descendants of the gods. They had a share in

the divinity, and the king was a mediator between the world of men and the world

of gods. This position was a central feature in the authority of the king and his men,

and in the pagan cosmology.

1 0

It would have been impossible for the Church to

present a faith where the aristocracy was robbed of this divine authority.

The Church adapted to these conditions by portraying the powerful, the

aristocracy and the kings, as God’s closest friends. As political leaders, they were in

the position to pay tribute to God by converting pagans, giving land to the Church,

building churches, and giving his men, the clerics, the opportunity to work for

God’s cause. This made them God’s friends, and therefore liable to receive the

most generous gifts in return. In the fully developed version of the Christian

ideology on kings, the king was given the position of rex iustus and God’s anointed.

He was king by the grace of God, the prime secular servant of God on earth. He

had a specific and exclusive task bestowed on him by God: to promote God’s cause

on earth through his power.

1 1

9

R. E. Sullivan, op. cit., p. 279.

10

See H. W olfram, Die Goten. Von den Anfa¨ngen bis zur M itte des sechsten Jahrhunderts. Entwurf einer historischen

Ethnographie, Dritte neubearbeitete Auflage (Mu¨nchen, 1990), p. 42 and pp. 114–116 on the Goths;

N . Staubach, “Germanisches K o¨nigtum und lateinische Literatur vom fu¨nften bis zum siebten

Jahrhundert”, Fru¨hmittelalterliche Studien, bd. 17 (1983), and J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, op. cit., p. 33 and

p. 35 on Merovingian kings and nobles; H. R. Loyn, Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest

(London, 1962), p. 230 and D. N. Dumville, “Kingship, genealogies and regnal lists”, Early M edieval

Kingship, edited by P. H. Sawyer and I. N . W ood (Leeds, 1977), pp. 77–79 on Anglo-Saxon kings

claiming descent from W oden; J. W erner, Das Aufkommen von Bild und Schrift im Nordeuropa, Bayerische

Akademie der W issenschaften. Sitzungsberichte. Philos.-hist. Kl. no. 4, (Mu¨nchen, 1966) and G.

Dume´zil, L’ideologie tripartie des Indo-Europe´ens (Brussels, 1959) more generally on the topic. C on-

cerning Scandinavia, see: F. Stro¨m, Diser, nornor, valkyrjor. Fruktbarhetskult och sakralt kungado¨me i Norden

(Stockholm, 1954); G. Steinsland, “De nordiske gullblekk med parmotiv og norrøn fyrsteideologi”,

Collegium M edievale, nr 3 (1990/1); G. Steinsland, Det hellige bryllup og norrøn kongeideologi. En analyse av

hierogami-myten i Sk

õ

´rnisma´l, Ynglingatal, H a´leygjatal og H yndluljo´d (Oslo, 1991); C. Fabech, op. cit.; J. P.

Schjødt, “Fyrsteideologi og religion i vikingetiden”, M ammen. Grav, kunst og samfund i vikingtid, Jysk

arkæologisk selskabs skrifter no. 28, edited by M. Iversen, U . Na¨sman and J. Vellev (AÊrhus, 1991); L.

Hedeager, “M yter og materiell kultur: Den nordiske oprindelsesmyte i det tidlige kristne Europa”,

TOR, Vol. 28 (1996).

11

J. M. W allace-Hadrill, op. cit., p. 33; S. Bagge, From Gangleader to the Lord’s Anointed (Odense, 1996).

Scand. J. H istory 23

Missionary Activity in E arly Medieval N orway

5

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

The road to conversion was smoothed by the missionaries’ giving the aristocracy

this privileged position in relation to God, a position almost identical to the one

they had previously held. But the clerics were also faced with the task of proving the

new faith to be better than the old one. The methods used to convince the kings

and magnates were to demonstrate the luck and good fortune enjoyed by followers

of Christ, and to point out the logical inconsistencies in the pagan faith. The priests

assured the powerful that God would protect his own, and that he would grant

victory on the battlefield to his powerful servants. This was demonstrated on several

occasions, such as when the still-pagan Merovingian king, Clovis, was close to losing

the battle against the Alamans at Tolbiac. He called upon the Christian God for

protection, and immediately, potential defeat turned into victory. Shortly

thereafter, Clovis was baptised.

The intellectual superiority of the Christian faith was demonstrated to the pagan

nobles in debates, some of which were recorded in the sources. The missionaries

were specifically taught how to conduct debates with the pagans on the power of

their gods and the consistency of their faith.

12

One example is the letter from

Bishop Daniel of Winchester, which advises Bonifatius on how to argue against the

pagan faith on his mission to Germany in 723–724. The bishop counsels him not to

question the descent of the pagan gods, nor the belief that they were born as a result

of mating between man and woman. Rather, he should argue that gods born in this

way could not be true gods. If the pagan gods were able to mate, they were men,

not gods, Daniel writes. And how could these gods, with their human disposition

and needs, exist before the world was made? And if the world has always been

there, who ruled the world before the gods were born, and from whose womb were

the first gods born? And if their gods are almighty, why do they not punish the

Christians, who argue against their existence and destroy their idols? And why are

the Christians in the possession of the most fertile and rich regions of the world,

plentiful in oil and wine, while the pagans live in the cold and hostile lands?

13

The priests and monks usually had an easy time in these intellectual battles. As

the main elements in the pagan Germanic religions were myths and rituals, they

lacked the developed theological understanding which is a hallmark of Christianity.

The Church housed a large corps of professionals who were familiar with the

extensive intellectual legacy from Antiquity, and solely occupied with the

intellectual refinement of the faith.

After the conversion of the powerful, the Church could start to establish itself in

the newly converted areas. This involved teaching and preaching to the masses,

with the intent of obtaining the inner acceptance of the Christian faith. At this

stage, when the pagan customs, which for centuries had satisfied the regular needs

of the population, were forbidden and abandoned, the new religion had to find

ways to satisfy the religious needs of the population. These needs included

12

R. E. Sullivan, op. cit., pp. 274–276.

13

The letter is printed in Briefe des Bonifatius. W ilibalds Leben des Bonifatius. Nebst einigen zeitgeno¨ssischen

Dokumenten, Ausgewa¨hlte Quellen zur deutschen Geschichte des Mittelalters, Vol. 4, edited by R.

Rau (Darmstadt, 1968), pp. 78–85 (Latin with a German translation); and in C . Krag, op. cit., pp.

51–57 (Latin with a Norwegian translation).

Scand. J. History 23

6

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

protecting against evil and illness and ensuring the well-being of descendants and

ancestors. These needs were fulfilled through the teachings and rituals of the

Church, through liturgy, sacraments, prayers, and pastoral work. The main

strategy in this phase was probably to avoid changes in the religious forms and,

whenever possible, to fill the old forms with new, Christian content. It was new wine

in old bottles, if the old ones could do the trick.

3. Conversion and m issionaries in Norway c. 900–1030 AD

This strategy was also applied in the conversion of Norway, which can be divided

into two phases. The first phase is the time of the brave and fearless monks. These

men may have followed converted magnates home from ventures in Christian

regions. Others may, like Ansgar on his venture to Birka in 829, have travelled into

the lands of the pagans, sought out their leaders, worked on their conversion, and

tried to gain their permission to set up churches and work in their territories. In

Norway, the missionary work was, over a substantial part of this period, supported

by the Christian king HaÊkon Adalsteinsfostre (c. 935–961). But his power was

limited, and he did not possess the political strength to bring about a general

conversion. Therefore, the success and survival of the missionaries throughout this

period depended on their success in converting the local aristocracy.

The general conversion of Norwegian society was completed in the second

phase. This was the time of the Christian kings who, in the sagas, are given the

credit for changing the society’s self-perception by implementing laws forbidding

pagan customs and enforcing Christian practices. In Norway, the two most

important of these kings were Olav Trygvasson and Olav Haraldsson. It is probably

justifiable to consider the return of Olav Trygvasson to Norway in the year 995 a

decisive event in the conversion of Norway.

But this was not the initial event. There is some written evidence of earlier

missionary activity in Norway, with the earliest recordings concerning the west

coast. Several sagas record that king HaÊkon Adalsteinsfostre, who returned from

England some time in the 930s, sent for priests once he had established himself as

king. He had churches erected and priests installed in the northwest. Later, these

churches were burned down and the priests were killed by the pagans.

1 4

Also

concerning the west coast, there are recordings of the legend of the Christian

princess Sunniva who died as a martyr as pagans approached the cave where she

hid. This may be a local version of an Irish legend, but the root of the legend may

also be in the fact that Irish hermits had found their way in small boats to the outer

Norwegian west coast, just as they found their way to other remote places to the

north and east of Ireland. Such hermits may have been working as missionaries in

the area.

There is also written evidence of missionaries working on the southeast coast in

the later half of the 10th century. Three bishops of the Danish town of Ribe are said

to have sent men of the cloth to Norway on several occasions in the second half of

14

W ritten sources describing this and the following incident are listed in P. S. Andersen, Samlingen av

Norge og kristningen av landet 800–1130 (Oslo, 1977), pp. 189–190.

Scand. J. H istory 23

Missionary Activity in E arly Medieval N orway

7

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

the 10th century. Snorre relates that king Harald BlaÊtann of Denmark sent

missionaries to the same area, called Viken, where he claimed authority. Snorre

writes that “many were baptised”. Furthermore, the German Emperor, Otto II, is

said to have sent two “earls” to this area in the 970s, where they worked as

missionaries.

It is difficult from the written record alone to assess the degree of success the

missionaries of the 10th century enjoyed in their proselytizing. The majority of the

sources were written long after the events took place. They mention the

missionaries only briefly, and lack reliable information about the duration and

results of the missionary work. We must turn to other forms of evidence to gain a

firmer understanding of this early phase in the missionaries’ efforts.

Some evidence can be derived from the archaeological record. I will consider this

evidence in light of the distinction made earlier between the general process of

Christianization and the conversion.

The Norse gained knowledge of Christian practice and faith during their travels,

and the impact of this influence can be observed in various changes in the form of

and equipment in pagan graves from the 9th and 10th centuries. During this

period, the number of cremations drops, and the number of inhumations increases.

Grave goods are often limited to personal equipment attached to the clothing, such

as weapons or brooches. Items like pots, pans and tools now appear less frequently

in the graves. This can be explained as a reflection of the influence of Christian

burial practices, especially as these changes are particularly evident in the ports of

trade from this period, like Birka in central Sweden, and Kaupang in Vestfold.

1 5

But this is not the type of evidence that can be used to deduce that conversion to

the Christian faith had taken place, or that missionaries were working in the

population. The changes observed in pagan burial practices are but one component

of a more general cultural influence, whereby Christian beliefs and customs may

have been transformed and included in pagan practices. Although they do not

necessarily indicate conversion, these changes are important elements in the history

of the Christianization, as they indicate a familiarity with Christian practises.

Indications of a fundamental conversion would be a total abandonment of pagan

burial practices, at least in a portion of the population. When changes of this kind

occur, the process of conversion has begun, and we may be certain that missionaries

were successfully working within the population, teaching and preaching, and

administering funerals according to Christian practices. I will now turn to the main

evidence indicating that such a change was in fact taking place.

In Trøndelag and in the hinterland of eastern Norway, pagan burial practices

were totally upheld until the very last decades of the 10th century, and in some

15

E. S. Engelstad, “Hedenskap og Kristendom I. Sen vikingtid i innlandsbygdene i Norge”, Bergen

M useums Aarbok, 1927. H istorisk-antikvarisk række, nr 1 (Bergen, 1928); E. S. Engelstad, “Hedenskap og

K ristendom II. Trekk av vikingetidens kultur i Østnorge”, Universitetets Oldsaksamlings Skrifter, Vol. 2

(Oslo, 1929); A.-S. Gra¨slund, “Den tidiga missionen i arkeologisk belysning – problem och

synpunkter”, TOR, Vol. 20 (1980), pp. 83–85; A.-S. Gra¨slund, Birka IV. The Burial Customs

(Stockholm, 1985), p. 301; C . Blindheim and B. Heyerdahl-Larsen, Kaupang-funnene, Vol. 2.

Gravplassene i Bikjholbergene/Lamøya. Undersøkelsene 1950–1957. Del A. Gravskikk, Norske Oldfunn, Vol.

16 (Oslo, 1995), p. 134.

Scand. J. History 23

8

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

areas into the 11th.

1 6

But on the southeastern coast of Norway, in Agder, Vestfold

and Østfold, there is a dramatic fall in the number of pagan graves in the last half of

the 10th century compared to the preceding decades.

17

This reduction may very

well be due to a large portion of the population in these coastal areas being put to

rest in accordance with Christian practices. Further indications as to early

conversions in large numbers in the Oslo fjord area comes from the discovery of a

Christian graveyard dating back to the last part of the 10th century, which was

excavated beneath the Church of St. Clement in Oslo.

18

In some regions on the west coast, such as Rogaland and Sunnmøre, the number

of pagan graves also drops dramatically around the middle of the 10th century,

indicating a conversion to Christian burial practice.

19

This evidence is supported by

the recent discovery of a Christian graveyard from this period at Veøy on the

northwest coast of Norway. Radiocarbon dating from the coffins indicates that the

oldest graves were no younger than the mid-10th century, and that they may even

be from the beginning of the century.

2 0

The archaeological and written evidence indicating successful missionary activity

from the middle of the 10th century, and on the west coast perhaps even earlier, is

further supported by the existence of stone crosses. In total, there are 60 raised

stones shaped as a cross or marked with one, the vast majority of which are found

on the west coast. Half of them were probably erected during the 11th century, but

the rest date from the 10th and the very latest part of the 9th century. Many of

these crosses were erected in pagan graveyards, probably to consecrate them.

Consecration of the graveyard, from the point of view of the monks and priests,

must have been a precondition for the performance of Christian burials there.

Furthermore, it can be suggested that consecration also eased conversion by

including the graves of pagan ancestors in the new Christian community.

21

One should also consider the possibility of substantial Christian influence in

western Norway in the late 9th century. Norse settlement in Christian areas in

Ireland, Scotland and northern England started around the mid-9th century. These

areas were mainly settled from western Norway. The sources on the conversion of

the settlers indicate that some kept their pagan customs well into the 10th century,

while others converted within a generation or so. The Vikings were involved in

internal politics in the settled areas, and their interaction with the local population

16

J. Schreiner, Saga og Oldfunn. Studier i Norges eldste historie, Skrifter utgitt av Det N orske Videnskaps-

Akademi i Oslo, 1927, Historisk-Filosofisk klasse, no. 4 (Oslo, 1928), tables II, III, IV, V, XIV, X V;

E. S. Engelstad, op. cit., “Hedenskap og Kristendom I”, p. 85, and “Hedenskap og K ristendom II”,

p. 380.

17

P. Rolfsen, “Den siste hedning i Agder”, Viking bd. 44, 1980 (Oslo, 1981); J. H. Larsen, Utskyldsriket.

Arkeologisk drøfting av en historisk hypotese, unpublished thesis, U niversity of Oslo (1978); L. Forseth,

Vikingtiden i Østfold og Vestfold. En kildekritisk gransking av regionale forskjeller i gravfunnene, unpublished

thesis, University of Oslo (1993), pp. 120–128.

18

O. E. Eide, De toskipede kirker i Oslo. Et forsøk paÊ redatering og opphavsbestemmelse med utgangspunkt i de siste

utgravninger i Clemenskirken, unpublished thesis, University of Bergen (1974).

19

J. H. Larsen, op. cit.; B. Solberg, Jernalder paÊ nordre Sunnmøre. Bosetning, ressursutnyttelse og sosial struktur,

unpublished thesis, University of Bergen (1976).

20

B. Solli, Narratives of Veøy. An Investigation into the Poetics and Scientifics of Archaeology, Universitetets

Oldsaksamlings Skrifter, Ny rekke, nr 19 (Oslo, 1996), pp. 152–155.

21

F. Birkeli, Norske steinkors i tidlig middelalder. Et bidrag til belysning av overgangen fra norrøn religion til

kristendom, Skrifter utgitt av Det N orske Videnskaps-Akademi i Oslo II. Hist-Filos. K lasse. Ny serie nr

10 (Oslo, 1973).

Scand. J. H istory 23

Missionary Activity in E arly Medieval N orway

9

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

must have made them very familiar with Christian practices and beliefs. The large

number of insular objects in pagan graves in Norway in the 9th century,

particularly on the northern part of the west coast,

2 2

indicates that the settlers

maintained communication with their homeland in the northeast. A culturally and

religiously very heterogeneous climate must have developed in the affected areas of

Britain and across the North Sea. The possible late 9th century dating of some of

the stone crosses on the Norwegian west coast may indicate that in this period,

there may have been opportunities for missionaries to follow their newly converted

Norse friends back to their old homelands.

As demonstrated, several types of evidence indicate that in the mid-10th century,

and maybe even in the first half, burials according to Christian rituals were

performed in some regions in the western part of Norway. Thus we can be

reasonably certain that priests and monks were working with some success on the

west coast of Norway during this period. The same applies for the southeast coast,

but the evidence in this region does not indicate conversions in any great number

before the second half of the 10th century. The possibility of missionary ventures on

the west coast in the late 9th century must also be considered, but at the present

stage of research no conclusive evidence exists.

Just before the turn of the millennium, a decided swing occurred in the

conversion of the Norse. To highlight certain dates as fundamentally important in

an historic process as long as the conversion is of dubious worth. However, as

mentioned earlier, an event which must be considered decisive was the arrival of

King Olav Trygvasson on the island of Moster in the year 995. According to the

sagas, the king brought priests with him, and during his five-year reign, he used

force to convert the magnates of most of Norway. He called local thing-meetings and

persuaded the participants to be baptised and accept Christian customs.

2 3

Another decisive incident occurred in the early 1020s, when, according to the

sagas, King Olav Haraldsson forced the population to accept Christian laws at a

thing-meeting, also on the island of Moster. The new regulations were composed

with the advice of Grimkjell, the king’s bishop. For contemporary society, the thing-

meeting at Moster was probably considered the definitive breakthrough in the

conversion of western Norway. The runic inscription on the Kuli stone states that

Christianity had been in Norway for 12 years when the stone was carved. Recent

dendrochronological dating from excavations near the stone indicates that it was

raised in the year 1034, some 12 years after the thing-meeting at Moster.

24

According to the sagas, Olav Haraldsson forced most regions to convert to

Christianity and made efforts to consolidate and organize the Church. By the end

of his regime, in the year 1030, Norwegian society can be considered to have

converted to Christianity.

This image of the kings being instrumental in the conversion is, as earlier stated,

solely based on the sagas. When one considers that their purpose is to tell the stories

2 2

E . W am ers, Insularer M etallscmuck in wikingerzeitlichen Gra¨bern Nordeuropas. Untersuchungen zur

skandinavischen Westexpansions (Neumu¨nster, 1985), Karte 3 and 6.

23

P. S. Andersen, op. cit., p. 103.

24

P. S. Andersen, op. cit., pp. 125–127; K. Pettersen, “Nordmøres forhistorie i landskapet”, AÊrbok for

Nordmøre 1990, (Kristiansund, 1990); J. R. Hagland, “Kulisteinen – endaÊ ein gong”, Heidersskrift til

Nils H allan paÊ 65-aÊrsdagen 13. desember 1991, edited by G . Alhaug et al. (Oslo, 1991), pp. 161–162.

Scand. J. History 23

10

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

of the kings, it becomes evident that there is a strong possibility of these sagas

putting too much emphasis on the royal contribution to the general conversion.

The sagas also have a strong tendency to focus on dramatic and violent incidents,

leaving everyday occurrences and gradual development unmentioned. Conflicts are

the main focus, and consequently their importance may very well have been

exaggerated. The opposition against the kings at the thing-meetings was probably

less united than is portrayed in the sagas.

Although many scholars have realized this problem, there is little evidence which

could correct the saga accounts. Certainly, from the sagas one may conclude that

not all of the king’s men were Christians, neither were all his opponents pagans. But

the main scheme in the sagas, especially in Snorre Sturlasson’s Heimskringla, is that

Christianity was the king’s main token, and that he expected his men to be baptised.

From the saga evidence, scholars have developed a theory that conversion was one

of the main strategies the kings used to undermine the authority of the old

aristocracy, which to a large degree rested on their central role in the pagan cult.

This may have been one of the kings’ strategies, but one must not oversimplify

the matter. One of Olav Haraldsson’s main and most powerful opponents, Erling

Skjalgsson, was a Christian who housed a priest, probably on his farm at Sola. This

is verified by a runic inscription on a stone cross, stating that the cross was erected

by the priest Alfgeirr after his lord Erling. From the saga account, it is clear that

Erling’s conversion certainly did not undermine his authority. Nor did it create any

barrier between him and other chieftains and warlords opposed to the king, for

instance, Asbjørn Selsbane.

The notion that the kings used conversion strategically presents problems of

another kind as well. Kristin Gellein has analysed evidence concerning the time of

conversion in the districts surrounding four royal farms in Hordaland, western

Norway. These farms are mentioned in the sagas as belonging to the king in the

early 10th century. If conversion was a central political strategy for Kings HaÊkon

Adalsteinsfostre, Olav Trygvasson and Olav Haraldsson, these districts should have

been influenced at an early stage, and the pagan burial custom should have come to

an early end. This does not seem to have been the case. W hen working on this very

detailed level, the rather imprecise dating of graves becomes a major obstacle.

Nevertheless, some indications may be found. On four of the farms immediately

surrounding the royal farm at Seim in Alversund parish, three out of four grave

finds from the Late Iron Age date from the 10th century. In the whole parish, there

are nine more graves from the same period, of which five can be dated to the 10th

century and one to the period 950–1030.

25

From Gellein’s data one may deduce

that the areas surrounding the four royal farms do not deviate from the general

picture in Hordaland, neither concerning the frequency of pagan graves nor the

end of the pagan burial practice.

26

It is also notable that none of the eleven stone

crosses in Hordaland has been erected on or in the vicinity of these farms.

27

25

K . Gellein, Kristen innflytelse i hedensk tid? En analyse med utgangspunkt i graver fra yngre jernalder i H ordaland,

unpublished thesis in Archaeology, U niversity of Bergen (1997), p. 74.

26

K . Gellein, op. cit., pp. 35–41.

27

K . Gellein, op. cit., pp. 77–86.

Scand. J. H istory 23

M issionary Activity in Early M edieval N orway

11

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

No definite conclusions can be drawn from this material. But the existing

evidence is sufficient to warn against simplistic interpretations about the relation-

ship between the conversion and the political efforts of the early kings to strengthen

their power. There was no clearly consistent pattern between conversion and

political attitudes towards the kings.

Definite conclusions about a close relationship between conversion and the

strengthening of royal authority should not be drawn from the contemporaneity of

the two processes. The parallelism in time certainly meant that the two processes

were intertwined. But it is worth remembering that in Denmark, a kingdom existed

for several centuries before the conversion took place, and Iceland was converted

several centuries before royal authority was introduced. In Norway, royal authority

existed more than a hundred years before Olav Trygvasson went ashore at the

island of Moster in 995. And the gradual strengthening of royal authority continued

until the 13th century. Even though weakening of local chieftains’ power and

strengthening of royal power seem to be the result of the long process of conversion,

they were not necessarily the result of a conscious strategy applied by the kings.

KaÊre Lunden has recently presented the view that political and social problems

resulting from religious plurality provided the main motive for the kings’ promoting

Christianity.

28

He emphasizes that the competition between the two religions

resulted in armed conflict, and that the doubts and anxieties which people,

including the kings, must have felt in a religiously divided population had a

disintegrating effect on society.

In my opinion, there is little evidence for any actual competition, not to mention

armed conflict, between the two religions. I would further underline the practical

rather than the psychological and metaphysical problems following from religious

plurality. A strong coherent force in the political and social life of the aristocracy

was participation in the cultic feasts held in the chieftain or king’s hall. In converted

society, these feasts continued in a somewhat altered form, with beer drunk in

honour of Christ and the Virgin, as prescribed in the law Gulatingsloven, chapters 6

and 7. The Christian mass, with the Eucharist as the central rite uniting all

Christians, made the common cult all the more important. In religiously divided

society, the cultic meal would have been greatly weakened as an arena for building

and maintaining friendships and alliances, since it would have been very difficult for

Christians to participate in the pagan feasts, and for pagans to be allowed into the

Christian feasts and masses. For the kings, as well as for other converted aristocrats,

all of whom built their power on alliances with other chieftains, this difficulty in

participating in communal dining would have been a major obstacle, which they

may have tried to overcome by bringing about conversion.

Rather than seeing conversion as mainly a political strategy applied by the kings,

we should see it as the result of two different but closely connected processes. On

the one hand, there was the expansive Church which, in the 10th and early 11th

centuries, worked towards the conversion of the Norse; a Church which had

forceful teachings, a developed missionary strategy, devoted and well-educated

28

K . Lunden, “Overcoming religious and political pluralism”, Scandinavian Journal of History, Vol. 22

(1997).

Scand. J. History 23

12

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

missionaries, and a close relationship with worldly power. On the other hand, there

was, in the 10th and early 11th centuries, a definite movement within the

Norwegian aristocracy, within which the kings were important, towards further

integration into the larger European culture. The forerunners in this development

were the kings and chieftains who had spent years of their lives ensconced in a

Christian culture, either having been brought up in the houses of foreign kings or

noblemen, having more or less settled in the Viking territories on the Continent or

in Britain, or having served in the armies of Christian kings. Those who returned to

Norway brought their ways with them, including their Christian practises. The

political aspects of this movement are obvious; the kings may have brought about

conversion in order to establish their Christian feasts and rites as a common arena

for building and maintaining friendships within the aristocracy. But the cultural

side of it, the identification of the homecomers with the Christian culture and the

desire to be a part of “the new time”, were perhaps even stronger driving forces in

the decades of conversion.

4. The organization of the early Church in Norway until 1100 AD

As has been demonstrated, the missionary strategy of the Church was to seek out

the worldly leaders, the kings and noblemen, to focus on their conversion, and

afterwards to work under their protection. The Christian God was depicted as

stronger than the old gods. The kings and noblemen were the close friends of God,

by virtue of the task assigned to them: to promote the cause of God on earth. Old

customs and rituals were, when possible, maintained, but they were pervaded with

Christian content. The inherently pagan rituals were forbidden.

The establishment of an ecclesiastical organization was an integral part of the

missionary venture,

29

and this early organization of the Church was infused with

the missionary strategy. The missionary bishops followed the king, travelling under

the protection of his hird. When they grew more numerous, some of them travelled

independently, but probably still under the protection of the king’s local allies and

their armed men. As the Church grew wealthier in the 11th century, the bishops

were protected by their own armed men, as is described in the oldest laws.

30

This loose organization of bishops, without fixed dioceses and sees, was

maintained for a long period after the conversion. As late as the early 1070s, Adam

of Bremen relates that the Norwegian bishops travelled constantly around the

country.

The local organization of the Church, below the level of bishop, was also closely

connected to the missionary strategy. The early Church was clearly aristocratic in

character, relying on worldly power. This was the case in the whole of

Christendom, but the support of the powerful was especially necessary in the

period of conversion, when the unarmed men of the Church could easily become

victims of hatred and violence. A priest most likely became a member of the

household of a friendly magnate, serving him by singing masses and administering

29

R. E. Sullivan, op. cit., pp. 292–295.

30

P. S. Andersen, op. cit., pp. 311–314.

Scand. J. H istory 23

M issionary Activity in Early M edieval N orway

13

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

the sacraments, probably mainly to the members of his family, his body of armed

men, and to his friends in the region.

3 1

Following the conversion of Norwegian society as a whole, the status of the

Church changed dramatically. A consequence of the acceptance of Christian laws

was that the entire population required the attentions provided by the clerics. These

included having their children baptised, their dead buried in the proper manner,

and so on. When need arose, priests had to be close at hand. A dense network of

priests had to be created throughout the country, graveyards had to be consecrated,

and in time, churches had to be built.

The contemporary evidence concerning this settling of the Church in Norway is

scant indeed. Obviously this expansion of the ecclesiastical organization had to

follow much the same line as before the general conversion. This is evident in the

sources concerning the missionary strategy in the Carolingian period. The

missionaries seem to have entered the newly converted areas in small groups,

settling as a unit at a place where they could be economically self-sufficient by

cultivating the land they acquired and setting up buildings for living quarters. Land

and buildings were supplied by sympathetic landowners, either the king, his allies,

or other local aristocrats. From these relatively few and scattered centres, the

missionaries travelled around the countryside, preaching, teaching and caring for

the population.

32

To get a firmer grip on how this general strategy was applied in Norway, we will

have to make use of more recent sources. From this evidence, we must work

backwards in time to uncover the organization of the Church in the missionary

period of the 11th century. I have carried out research on this topic in Romerike,

one of the main settlement regions in central eastern Norway.

3 3

Romerike is situated just northeast of Oslo, south of Lake Mjøsa, and north of

Lake Øyeren. The region measures approximately 35 km east to west and 60 km

north to south. The topography is relatively flat, and the region is surrounded by

rocky hills covered by forest. The interior is composed of fertile soils, although

habitation areas are separated by hills, and by areas with poor sandy soil or

marshes.

In the 14th century, 37 churches were located in this region. In the medieval

ecclesiastical cadaster from the diocese of Oslo, the rights to the tithe are recorded

for most of these churches, and in several instances the actual income from the tithe

is also recorded.

3 4

Investigation of this information reveals an interesting pattern.

Normally the tithe from a parish was divided into four equal portions, one for the

bishop, one for the parish priest, one for maintaining the parish church, and one for

the poor in the parish. In only a few of the 37 parishes does the normal division

appear to have been implemented. The medieval cadaster reveals that in half of the

parishes, the priest and the church buildings had rights to considerably less than

31

D. Skre, “Kirken før sognet”; Achen, op. cit..

32

R. E. Sullivan, “The C arolingian missionary and the pagan”, Speculum. A Journal of M edieval Studies,

Vol. 28, pp. 706–707.

33

The following is based on D. Skre, “Kirken før sognet”, and D. Skre, H erredømmet. Bosetning og besittelse

paÊ Romerike 200–1350 e. Kr., Acta Humaniora, nr. 32, U niversitetsforlaget, (Oslo, 1998).

34

The medieval cadaster, which dates from 1390–1394 and is called Biskop Eysteins Jordebok, was

published from 1873–1880 by H. J. Huitfeldt.

Scand. J. History 23

14

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

their normal share, while four of the churches had the rights to considerably more

than the shares which they received from their own parishes. Further investigation

indicates that the extra tithe these four churches received was balanced by the

shares of which the neighbouring churches were deprived.

35

The obvious conclusion is that in the 14th century, each of these four churches

had the right to receive large shares of the tithe from the closest surrounding

parishes, whereas in the peripheral parishes, full shares were allotted to the priest

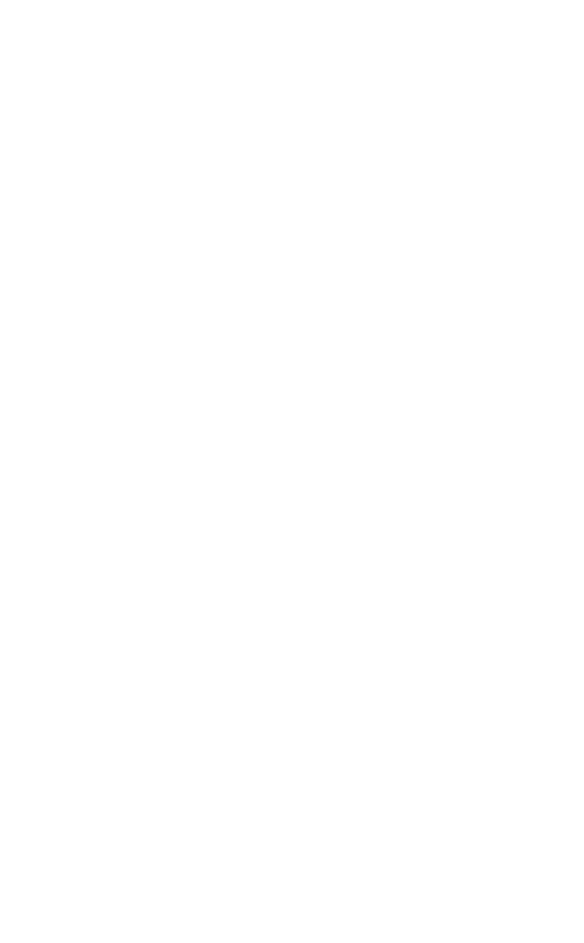

and to the church buildings (Fig. 1). This system of re-allotment of tithes can not be

explained by contemporary circumstances, and the origin for this arrangement,

therefore, must be sought in the early organization of the Church.

In the early medieval laws from this region, the Eidsivatingsloven, the main

churches are called hovedkirker. The four churches receiving portions of the tithe

from neighbouring parishes must have been the hovedkirker of Romerike.

Unfortunately, Norwegian sources are rather silent as to the nature and tasks of

a hovedkirke, which literally means “main church”. We must turn to evidence as to

how the Church was organized on a local level in England and the northern part of

the Continent, the areas from which the missionaries came. This evidence reveals,

not surprisingly, close parallels to the Church’s organization in the missionary fields

in Norway.

During the last decade, the organization of the local Church in the period before

the parish system has received much scholarly attention, starting with a conference

report edited by John Blair.

3 6

Since then the “minster hypothesis” has been heavily

debated, but it would be fair to say that it has survived in a refined form, the main

points being that prior to the division into parishes, most priests were living in

central institutions. In some areas these were called minsters, in others baptismal

churches.

37

Their work was partially conducted in the minster and its immediate

surroundings. But the territory of each minster was often so extensive that the

priests had to journey long distances within the territory, to conduct masses in

homes, churches and chapels. From the 9th to 12th centuries, many private

churches were built, and an increasing number of church owners in England and

on the Continent installed priests in their own churches. As the number of priests

increased, the tasks of the journeying minster-priests were transferred to these local

priests. Simultaneously, though reluctantly, most of the economic privileges of the

minsters were locally allocated as well. During the 12th century, the minster system,

in which a few central churches were surrounded by several secondary churches,

was replaced by the parish system, which was composed of churches with fairly

equal rights. However, in many regions, the old minsters succeeded in retaining

some of their former privileges, for instance, their right to a share in the tithe from

the parishes in what was once their territory.

35

D. Skre, H erredømmet, pp. 72–89.

36

J. Blair, M insters and Parish Churches. The Local Church in Transition 950–1200, Oxford University

C ommittee for Archaeology, M onograph nr 17 (Oxford, 1988).

37

The following is based on G. W . O. Addleshaw, “The early parochial system and the Divine

Office”, Alcuin Club Prayer Book Revision Pamphlets, nr 15 (London, 1957); G. W . O. Addleshaw, “The

development of the parochial system from Charlemagne (768–814) to U rban II (1088–1099)”, St.

Anthony’s H all Publications, nr 6, 2nd edition (York, 1970); F. Barlow, The English Church 1000–1066 . A

H istory of the Later Anglo-Saxon Church. (London, 1979); J. Blair, op. cit.; J. Blair and R. Sharpe, Pastoral

Care Before the Parish (Leicester, London, N ew York, 1992).

Scand. J. H istory 23

M issionary Activity in Early M edieval N orway

15

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

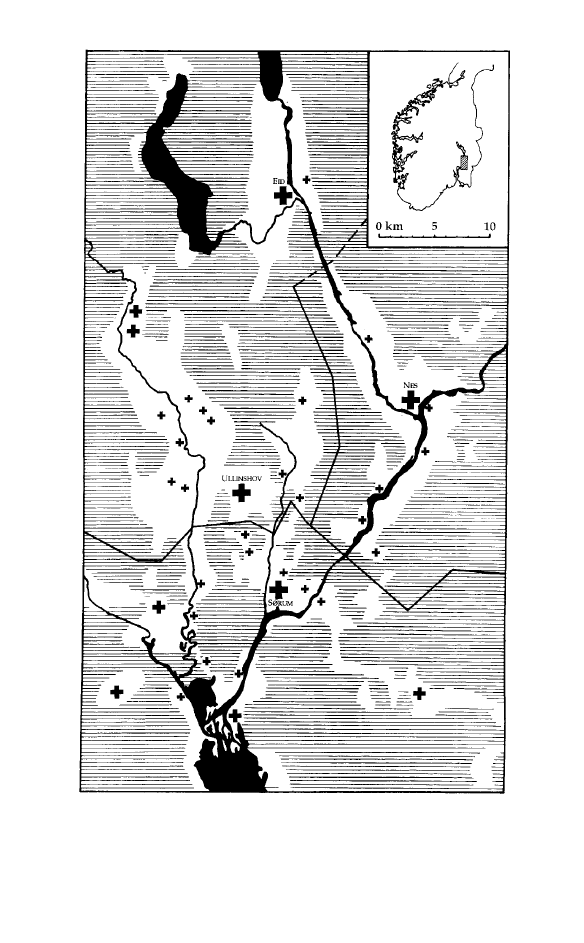

Fig. 1. This map of Romerike shows the different churches’ rights to tithe in the late 14th century. The

four hovedkirker at Romerike, Eid, Nes, Ullinshov and Sørum (large crosses) had the full right to tithe from

their own parish, plus a substantial share in the tithe from the parishes in the vicinity (small crosses). The

more distant churches had full rights to tithe from their own parish (medium-sized crosses). The probable

borders of the tridjung, which is mentioned in the 12th century in connection with the hovedkirker, are

indicated. Shading indicates inhabited areas.

Scand. J. History 23

16

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

The tithe arrangements of 14th century Romerike accord very well with this

development. Except for the differences caused by the late establishment of the

Church in Norway, meaning that we should not expect the large and costly

churches, the well-established institutions, and the large number of priests found in

Britain, the parallels between the Norwegian hovedkirker

3 8

and the British minsters

are obvious. Early on, priests from the four main churches took care of the pastoral

work in the entire region. As the number of churches grew, local priests were

installed. The more distant churches would have been the first to have their own

priests, as the populations there must have suffered when there was an acute need

for the service of the priest, for instance, when someone was ill and the

administering of the Extreme Unction was needed. It must have been easier for the

minster priests to maintain their rights to income from the parishes that were closer

to the main church. As has been demonstrated, they still kept a share of this income

in the 14th century.

The precise chronology of this development is difficult to ascertain, but some

indications may be deduced from the archaeological record. To date, the remains

of ten early wooden churches have been excavated in Norway. None of these

churches can be demonstrated to be older than the second half of the 11th

century.

39

This would imply that the building of churches did not gain momentum

until this period, and that the number of churches was still small in the 10th century

and the first half of the 11th. However, it should be noted that several of the

churches were built on Christian graveyards which were established in the first half

of the 11th century, and, in some cases, even in the 10th century.

This chronology in the building of churches may correspond to the early

developmental stages in the organization of the local Church in Norway. In the

missionary period, that is, until the later part of the 11th century, the religious

needs of the population were dealt with by clerics situated in central churches, the

hovedkirker. Some of the sacraments were probably only administered in these central

churches, for instance, baptism. But several clerical duties, like singing mass and

conducting funerals, were probably performed locally by priests travelling in the

districts surrounding their hovedkirker. The main task of these priests was probably to

teach the fundamental truths, the essential prayers, and the meanings of the mass

and the sacraments to a population as yet only vaguely familiar with them.

In the later part of the 11th century, the more widespread building of churches

occurred and continued into the 12th century. The building of churches and the

installation of local priests eventually led to fragmentation of the territories of the

hovedkirker and the advent of the parish system in the High Middle Ages.

The intense church-building beginning in the second half of the 11th century can

be interpreted as an indication of the ultimate acceptance of the Christian

cosmology by the population. The teachings of the Church were no longer alien to

the minds of the Norse, and the missionary period in Norway was over.

Evidence from throughout the country indicates that the building of churches in

the later part of the 11th century and onwards was mainly conducted by the king

38

In laws other then the Eidsivatingsloven they are called fylkeskirker, literally, “county churches”.

39

D. Skre, “Kirken før sognet”, pp. 215–216.

Scand. J. H istory 23

M issionary Activity in Early M edieval N orway

17

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

and the local aristocracy. The evidence from Romerike certainly confirms this

belief. Thirty-five out of the 37 churches are located on large farms. But what about

the hovedkirker, which probably originate from the 10th and early 11th centuries?

Who opened their houses to the first priests working permanently in the region,

who gave them shelter, protection and supplied the other necessities of life? To

begin to answer these questions, we will return to the evidence from Romerike, and

investigate two of the four hovedkirker, the churches at Eid and Sørum.

The sagas tell us that the king founded some of the earliest churches. The

hovedkirke at Eid is an example of this. Snorre relates that king Olav Haraldsson

stayed for some days at Eid. He went to church there, and he established Eid as the

location for the yearly meeting of the Eidsivating. One should not rely too heavily on

this kind of detailed information, written 200 years after the events took place. But

the impression left by Snorre’s writing, that the king was instrumental in

establishing the hovedkirke at Eid, is supported by evidence concerning the ownership

of land around the church. From examination of medieval documents, it appears

that the king in the 11th century owned the eight farms surrounding the church at

Eid. A small local estate like this is just the place one would expect the king to

establish a hovedkirke. Here he had buildings, supplies, men and land, all of which

was necessary to protect and feed the clerics.

From the sagas and from runic inscriptions, we know of several instances of local

aristocrats receiving priests and building churches. But were these churches meant

for the private use of the magnate, or could the local aristocracy also establish

hovedkirker that would serve the whole region?

The southernmost of the four hovedkirker at Romerike, the one at Sørum, is

illuminating in this respect. In the High Middle Ages, this farm was the residence of

the owner of the estate called Sørumsgodset, which at this time consisted of farms

distributed throughout Romerike. The history of the estate may be traced back to

the mid-12th century, but it is probably considerably older. The main part of the

estate was located in the immediate surroundings of the farm at Sørum where the

minster was founded, probably in the first half of the 11th century. The

establishment of the minster at Sørum in this core area of the Sørum estate must

have been implemented by one of the Sørum magnates.

Evidence from other parts of the country indicates that the picture from

Romerike is a common one. The king in particular, but also prominent magnates

offered the men of the Church shelter, protection and the opportunity to work in

the region. Furthermore, the practice of installing priests on the estates of kings and

magnates, in institutions resembling the minsters, probably goes back to the middle

or even the first half of the 10th century, to the days of King HaÊkon

Adalsteinsfostre.

5. Epilogue

The conversion of Norway is often portrayed as a violent process, with the king

forcing a new faith on a reluctant population. It is also considered a fundamental

religious change which caused social disruption. But this picture is based on the

sagas, which often concentrate on the dramatic and violent incidents. It must be

balanced against other types of evidence regarding the conversion, and against the

Scand. J. History 23

18

Dagfinn Skre

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

general character of Christian missions in northern Europe around the end of the

first millennium.

Although missionaries sometimes followed in the tracks of armies invading pagan

lands and took part in forced conversions, the Church’s main strategy in pagan

areas was to convert the powerful, to fill the pagan religious forms with Christian

content, and to avoid overt change which could undermine the authority of the

aristocracy.

The role of the missionaries working directly on the conversion of the aristocracy,

both in Norway and, while the Vikings remained, more or less temporarily in

Christian areas, should not be underestimated. The Christian graveyards and stone

crosses dating to the 10th century, and perhaps the late 9th, and the gradual

abandonment of pagan burial practices in the 10th, indicate that the missionaries

met with considerable success in the coastal areas of southern Norway, even though

support from the Christian kings of Denmark and Norway appears to have been

weak and frail.

The role of the kings in the conversion of Norwegian society was certainly

decisive. The political motive behind these campaigns was probably to establish the

Christian equivalent of the cultic feasts as a common arena for the aristocracy to

create and maintain friendly relations with the king and its members. However, the

kings’ efforts should mainly be seen as part of a stronger orientation within the

Norwegian aristocracy towards Christian culture. This close connection to

Continental and British cultures is also mirrored in the early organization of the

Church, which has close parallels to the minster pattern in these areas.

In my opinion, the picture from the sagas of violent conversion and dramatic

religious changes must be supplemented and partly replaced by the image of the

aristocracy identifying itself more strongly with the larger European aristocratic

culture, and by the clerics working peacefully towards the conversion of the

aristocracy, preaching about the new God: a God whom they claimed to be much

the same as the old ones, only stronger and better.

Scand. J. H istory 23

M issionary Activity in Early M edieval N orway

19

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:37 24 January 2014

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Intrinsic Brain Activity in ASC

Foreign Archaeological Missions Working in Cyprus

Economics is the social science that studies economic activity in a situation

Gabriel s Oboe (Mission) inst in C

Increased osteoclastic activity in acute Charcot s osteoarthropathy the role of receptor activator

Taylor, Functional Uses of Reading and Shared Literacy Activities in Icelandic Homes

Sexual Attitudes and Activities in Women with Borderline Personality Disorder Involved in Romantic R

Gabriel s Oboe (Mission) inst in B

Haisch TOWARD AN INTERSTELLAR MISSION ZEROING IN ON THE ZERO POINT FIELD INERTIA RESONANCE (1996)

activities in city & country

antinoceptive activity of the novel fentanyl analogue iso carfentanil in rats jpn j pharmacol 84 188

Antibacterial Activity of Isothiocyanates, Active Principles in Armoracia Rusticana Roots

Magiczne przygody kubusia puchatka 31 MISSION IN IRAQ

In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Ethanolic Extract

Evaluation of in vitro anticancer activities

Chemical Composition and in Vitro Antifungal Activity Screening

Apoptosis Induction, Cell Cycle Arrest and in Vitro Anticancer Activity

więcej podobnych podstron