2011 Oct;50(10):1179-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05029.x.

Treatment of acne scarring.

.

1

Department of General Practice, Monash University, South Yarra, Victoria, Australia.

gg@div.net.au

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Post-acne scarring remains a common entity despite advances in the treatment of acne. This represents

limitations in our quality of therapy and a failure of public education. The level of severe scarring remains

as much an ongoing challenge to prevent as well as manage.

METHODS:

This review will concentrate on the methods by which acne scarring may be improved and the available

evidence for their utility. It will also rely on a grading scale of disease burden to classify patients and their

ideal therapy. New therapies allowing treatment of scarring in areas other than the face will also be

highlighted.

RESULTS:

Tabulated treatment planning will present algorithms summarizing best practice in the treatment of post-

acne scarring.

CONCLUSION:

Post-acne scarring is being better managed. Grade 1 scars with flat red, white, or brown marks are best

treated with topical therapies, fractionated and pigment or vascular-specific lasers and, occasionally,

pigment transfer techniques. Grade 2 mild scarring as seen primarily in the mirror is now the territory of

non-ablative fractionated and non-fractionated lasers as well as skin rolling techniques. Grade 3 scarring,

visible at conversational distance but distensible, is best managed by traditional resurfacing techniques or

with fractional non-ablative or ablative devices, sometimes including preparatory surgical procedures.

Grade 4 scarring, where the scarring is at its most severe and non-distensible, is most in need of a

combined approach.

© 2011 The International Society of Dermatology

Retinoic acid and glycolic acid combination in the treatment of acne

scars.

.

1

Department of Dermatology, CUTIS, Academy of Cutaneous Sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka,

India.

Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Acne is a prevalent condition in society affecting nearly 80-90% of adolescents often resulting in

secondary damage in the form of scarring. Retinoic acid (RA) is said to improve acne scars and reduce

postinflammatory hyperpigmentation while glycolic acid (GA) is known for its keratolytic properties and its

ability to reduce atrophic acne scars. There are studies exploring the combined effect of retinaldehyde

and GA combination with positive results while the efficacy of retinoic acid and GA (RAGA) combination

remains unexplored.

AIM:

The aim of this study remains to retrospectively assess the efficacy of RAGA combination on acne scars

in patients previously treated for active acne.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A retrospective assessment of 35 patients using topical RAGA combination on acne scars was done. The

subjects were 17-34 years old and previously treated for active acne. Case records and photographs of

each patient were assessed and the acne scars were graded as per Goodman and Baron's global

scarring grading system (GSGS), before the start and after 12 weeks of RAGA treatment. The differences

in the scar grades were noted to assess the improvement.

RESULTS:

At the end of 12 weeks, significant improvement in acne scars was noticed in 91.4% of the patients.

CONCLUSION:

The RAGA combination shows efficacy in treating acne scars in the majority of patients, minimizing the

need of procedural treatment for acne scars.

KEYWORDS:

Acne scars; glycolic acid; retinoic acid; retinoic acid and glycolic acid

Hyaluronic acid inhibits the glial scar formation after brain damage

with tissue loss in rats.

1

Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei

110, Taiwan.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Brain tissue scarring (gliosis) was believed to be the major cause of epileptic focus after brain injury, and

prevention of scarring could reduce the incidence of seizure. We tried the HA coating onto the cortical

brain defect of Spraque-Dawley rats to reduce the marginal glial scarring.

METHODS:

A 4 x 2 x 2 mm(3) cortical defect was created in the brain of Spraque-Dawley rats. Three percent HA gel

was coated onto the lesion for the experimental groups and normal saline solutions for the control groups.

The brain was retrieved 4, 8, and 12 weeks after treatment. The brains were then sectioned and

processed for H&E and GFAP staining, and the thickness of the scarring and the number of GFAP+ cells

were analyzed.

RESULTS:

The thickness of cutting marginal gliosis was significantly decreased in the HA groups. The 12-week HA

group showed the smallest thickness of gliosis, whereas the 12-week control group exhibited the largest

thickness of gliosis. The significant difference in the thickness of gliosis was also noted between the HA

and the control groups 8 weeks after treatment. The number of GFAP+ cells was also significantly

decreased in the HA groups when compared to the respective control group 4, 8, and 12 weeks after the

surgery.

CONCLUSION:

The results support the hypothesis that HA inhibits glial scarring not only by decreasing the thickness of

gliosis but also by reducing the number of the glial cells. Furthermore, our results suggest that HA might

be used to reduce glial scar formation in central nervous system surgery, which subsequently prevents

the post-operation or posttraumatic seizure incidence

2010 Sep;9(3):246-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00513.x.

Lactic acid peeling in superficial acne scarring in Indian skin.

Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Chemical peeling with both alpha and beta hydroxy acids has been used to improve acne scarring with

pigmentation. Lactic acid, a mild alpha hydroxy acid, has been used in the treatment of various

dermatological indications but no study is reported in acne scarring with pigmentation.

AIMS:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of full strength pure lactic acid 92% (pH 2.0) chemical peel in

superficial acne scarring in Indian skin.

MATERIAL AND METHODS:

Seven patients, Fitzpatrick skin type IV-V, in age group 20-30 years with superficial acne scarring were

enrolled in the study. Chemical peeling was done with lactic acid at an interval of 2 weeks to a maximum

of four peels. Pre- and post-peel clinical photographs were taken at every session. Patients were followed

every month for 3 months after the last peel to evaluate the effects.

RESULTS:

At the end of 3 months, there was definite improvement in the texture, pigmentation, and appearance of

the treated skin, with lightening of scars. Significant improvement (greater than 75% clearance of lesions)

occurred in one patient (14.28%), good improvement (51-75% clearance) in three patients (42.84%),

moderate improvement (26-50% clearance) in two patients (28.57%), and mild improvement (1-25%

clearance) in one patient (14.28%).

© 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Biweekly serial glycolic acid peels vs. long-term daily use of topical

low-strength glycolic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.

1

Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, Gaziantep University, Turkey.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

Treatment of atrophic acne scars is difficult and generally unsatisfactory. Although many clinical studies

have been performed to investigate the efficacy of glycolic acid in the treatment of acne vulgaris, to the

best of our knowledge no placebo-controlled study has been carried out to ascertain the effect of glycolic

acid on atrophic postacne scars.

DESIGN:

A single, blind, placebo-controlled, randomized comparative clinical study was conducted in 58 women

with atrophic acne scars. The subjects were randomly divided into three study groups. Glycolic acid peels

with 20%, 35%, 50%, and 70% concentrations were applied serially at 2-week intervals to 23 patients in

Group A. Twenty patients in Group B used a 15% glycolic acid cream once or twice daily for a period of

24 weeks. The remaining 15 patients in Group C applied a placebo cream twice daily during the same

period.

RESULTS:

The differences between the results in the different groups were statistically significant at week 24

(P<0.001). Home application of low-strength glycolic acid was better tolerated and had less side-effects

than glycolic acid peels; however, repeated short-contact 70% glycolic acid peels provided superior

results compared with the maintenance regimen (P<0.05), and apparently good responses were

observed only in the peel group (P<0.01).

CONCLUSIONS:

Glycolic acid peeling is an effective modality for the treatment of atrophic acne scars, but repetitive peels

(at least six times) with 70% concentration are necessary to obtain evident improvement. Long-term daily

use of low-strength products may also have some useful effects on scars and may be recommended for

patients who cannot tolerate the peeling procedure.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul-Dec; 2(2): 104–106.

doi:

PMCID: PMC2918339

The Efficacy of Silicone Gel for the

Treatment of Hypertrophic Scars and

Keloids

and

Copyright and License information ►

This article has been

Abstract

Topical self drying silicone gel is a relatively recent treatment modality promoted as an

alternative to topical silicone gel sheeting. Thirty patients with scars of different types including

superficial scars, hypertrophic scars, and keloids were treated with silicon gel application. The

results of the self-drying silicone gel have been satisfactory.

Keywords: Keloids, scars, silicone

INTRODUCTION

Scars vary greatly in quality, depending on individual and racial patient features, the nature of

the trauma, and the conditions of wound healing.[

] They frequently determine aesthetic

impairment and may be symptomatic, causing itching, tenderness, pain, sleep disturbance,

anxiety, depression and disruption of daily activities. Other psychological sequelae include

posttraumatic stress reactions, loss of self esteem and stigmatization leading to a diminished

quality of life. Scar contractures also can determine disabling physical deformities.[

] All these

problems are more troublesome to the individual patient, particularly when the scar cannot be

hidden by clothes. This study was undertaken to verify the efficacy of a new topical silicone

treatment; a self-drying spreadable gel that needs no means of fixation and cannot be seen

because of complete transparency.

Silicone gel contains long chain silicone polymer (polysiloxanes), silicone dioxide and volatile

component. Long chain silicone polymers cross link with silicone dioxide. It spreads as an ultra

thin sheet and works 24 hours per day.[

] It has a self drying technology and itself dries within

4-5 minutes. It has been reported to be effective and produce 86% reduction in texture, 84% in

color and 68% in height of scars.[

] Silicon gel exerts several actions which may explain this

benefit in scars:

a. It increases hydration of stratum corneum and thereby facilitates regulation of fibroblast

production and reduction in collagen production. It results into softer and flatter scar. It

allows skin to "breathe".

b. It protects the scarred tissue from bacterial invasion and prevents bacteria-induced

excessive collagen production in the scar tissue.

c. It modulates the expression of growth factors, fibroblast growth factor β (FGF β) and

tumor growth factor β (TGF β). TGF β stimulates fibroblasts to synthesize collagen and

fibronectin. FGF β normalizes the collagen synthesis in an abnormal scar and increases

the level of collagenases which breaks down the excess collagen. Balance of fibrogenesis

and fibrolysis is ultimately restored.

d. Silicone gel reduces itching and discomfort associated with scars.

The advantages of silicon gel include easy administration, even for sensitive skin and in children.

It can be applied for any irregular skin or scar surfaces, the face, moving parts (joints and

flexures) and any size of scars. A tube of 15 gram contains enough silicone gel to treat 3-4 inches

(7.5-10 cm) scar twice a day for over 90 days.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study enrolled 30 patients having scars. Written informed consent was taken from all the

patients before the study. Also, prior approval of hospital ethical committee was taken before the

study. The silicone gel was applied as a thin film twice a day. It was rubbed with fingertips for 2-

3 minutes. For fresh scars, treatment was started just days after wound closure or after 5-10 days.

The scars were evaluated at monthly intervals. The appearance of scar, including scar type, scar

size and scar color was assessed by the physician. We classified hypertrophic scar as a red or

dark pink, raised (elevated) sometimes itchy scar confined within the border of the original

surgical incision, with spontaneous regression after several months and a generally poor final

appearance. A keloid is instead classified as a scar red to brown in colour, very elevated, larger

than the wound margins very hard and sometimes painful or pruritic with no spontaneous

regression.

Patients were observed and the results were compared at monthly follow up examinations.

Follow up was done for 6 months. All scars were measured and photographed before treatment

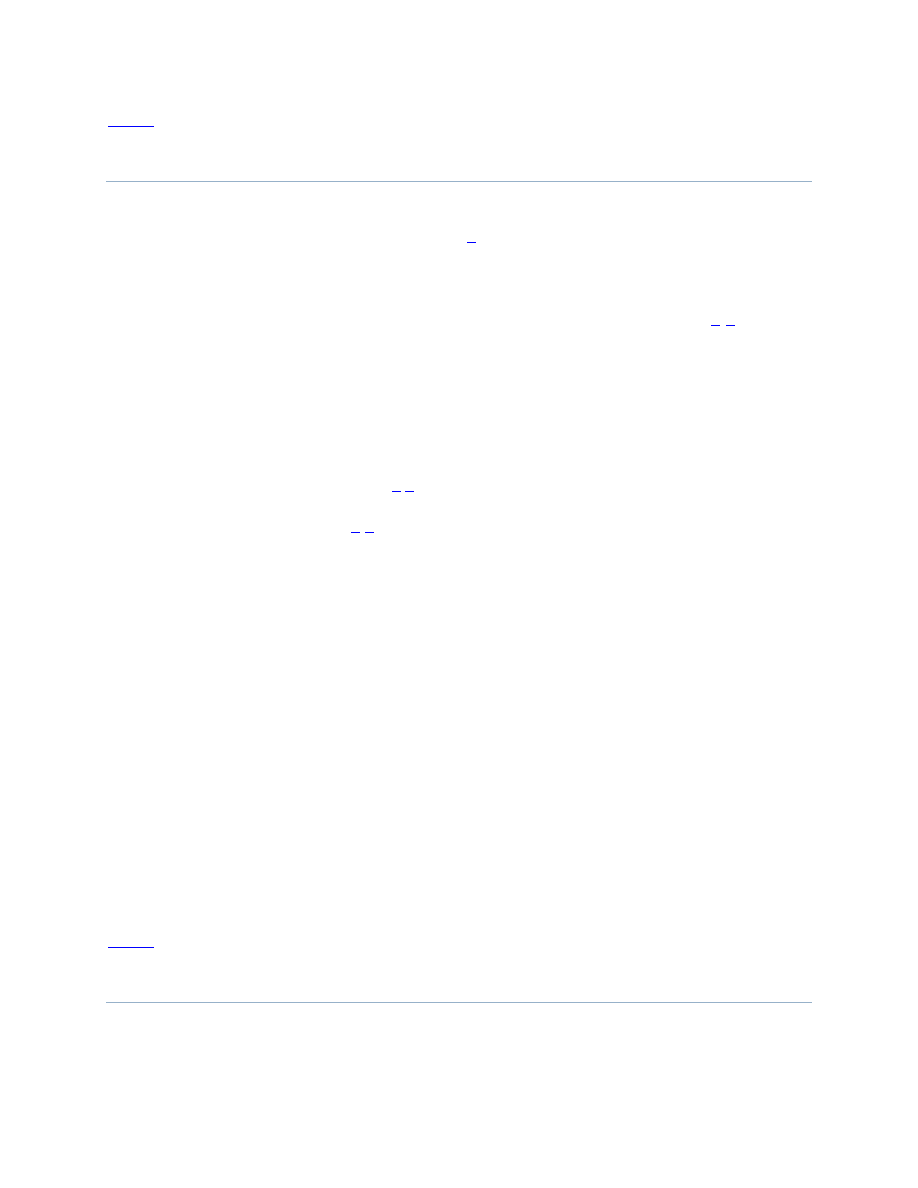

onset. Scars were graded 1 to 4 on the basis of criteria in

. Final photographs were taken

at this time.

Classification of scars according to morphologic features

RESULTS

Eleven cases (36.66%) were in the age groups of 30-40 years, 8 (26.66%) cases between 20-30

years, 5 (16.66%) cases between 40-50 years, 2 (6.610%) cases between 10-20 years and 50-60

years of age each and 1 (3.33%) case of > 60 years of age and between 5 and 10 years of age

each. Male:Female ratio was 2:1. It was also seen that most (40%) of the scars were between 1

and 3 months duration, 26.6% of scars were of less than 1 month duration, 20% of scars were

between 3 and 6 months and 13.33% scars were of more than 6 months duration. The commonest

type of scars were hypertrophic scars (Grade III, 50%) followed by mildly hypertrophic scars

(Grade II, 26.6%) and keloids (Grade IV, 23.33%). Most of the scars were between 1 and 3

months duration (40%), 26.6% of scars were of less than 1 month duration, 20% of scars were

between 3 and 6 months and 13.33% scars were of more than 6 months duration,

After treatment, improvement was noted in the scars [Figures

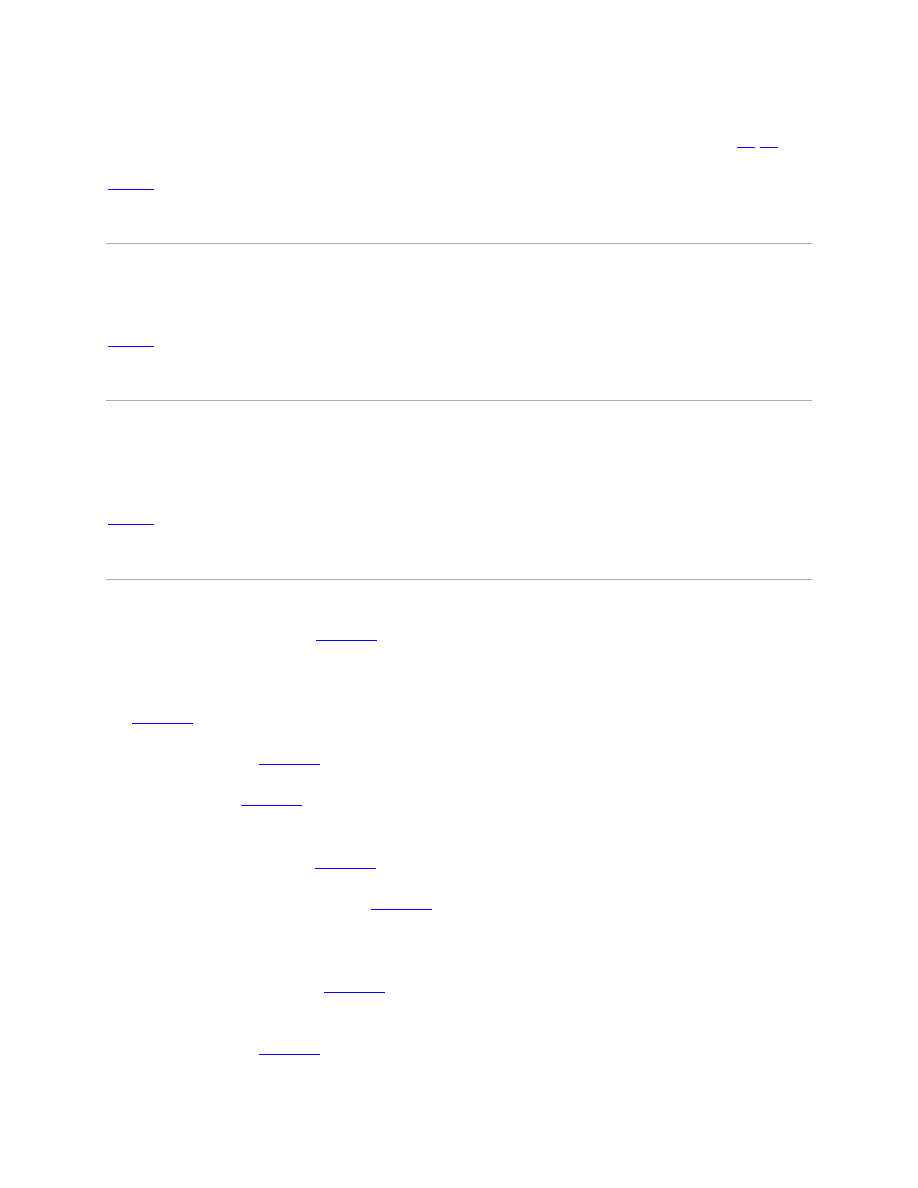

]. Sixty percent scars

were graded as normal (Grade I), while 20% were graded as mildly hypertrophic (Grade II).

Twenty percent of scars were of Grade III and IV at the end of study;10% in each grade [

]. Side effects were few. Allergic reaction to silicone gel was seen in one case and mild

desquamation was seen in 2 cases.

A patient with hypertrophic scar before and after treatment

A patient with minor keloid before and after treatment

Grading of scars after treatment

A patient with burn scar before and after treatment

DISCUSSION

Since the early 1980s, silicone gel sheeting has been widely used in the treatment of hypertrophic

scars and keloids. Several clinical studies and reviews have confirmed its efficacy.[

While many treatments have been suggested in the past for scars, only a few of them have been

supported by prospective studies with adequate control group. Only two treatments can be said to

have sufficient evidence for scar management; topical application of silicone gel sheeting and the

intralesional injection of corticosteroids.[

] The former generally is indicated as both a

preventive and the therapeutic device, the latter as a therapeutic agent only.[

] Topical silicone

gel sheeting is cumbersome to keep on the scar, and the patient compliance often is low for

lesions in visible areas.[

] Tapes or bandaging frequently is not accepted. It may also lead to

skin irritation, which can require discontinuation of treatment, especially in hot climates. Gel

sheeting is effective for scar control, but patient compliance with the method is not always

satisfactory.[

] Steroid injections are painful and may lead to skin atrophy and dyschromies.

They usually are contraindicated for large areas and for children.

Topical silicon gel application can overcome some of these limitations.

Self drying silicone gel is appealing because it is effective, no fixation is required; it is invisible

when dry; and sun blocks, makeup or both can be applied in combination.

However, on areas of the body covered by clothes, it must be perfectly dry before the patient

dresses, and this may not be always practical. All the patients felt the gel was easy to apply, but

some complained of prolonged drying time. The use of a hair dryer was recommended to

overcome this problem. When the scars are located in visible areas, especially on the face,

patients can experience psychological discomfort with the visibility of the treatment. In warm

climates, skin reactions are relatively common, often leading to treatment interruption.[

CONCLUSIONS

Topical silicon gel is safe and effective treatment for hypertrophic and keloidal scars. It is easy to

apply and cosmetically acceptable.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Tuan TL, Nichter LS. The molecular basis of keloid and hypertrophic scar formation. Mol

Med Today. 1998;4:19–24. [

2. Dyakov R, Hadjiiski O. Complex treatment and prophylaxis of post-burn cicatrization in

childhood. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2000;13:238–42.

3. Ahn ST. Topical silicone gel: A new treatment for hypertrophic scars. Surgery. 1989;106:781–

7. [

4. Ahn ST. Topical silicone gel for the prevention and treatment of hypertrophic scar. Arch Surg.

1991;126:499–504. [

5. Beranek JT. Why does topical silicone gel improve hypertrophic scars? A hypothesis. Surgery.

1990;108:12–18. [

6. Quinn KJ. Silicone gel in the scar treatment. Burns. 1987;13:833–5.

7. Sawada Y, Sone K. Treatment of scars and keloids with a cream containing silicone oil. Br J

Plast Surg. 1990;43:683–6. [

8. Poston J. The use of the silicone gel sheeting in the management of hypertrophic and keloids

scars. J Wound Care. 2000;9:10–2. [

9. Suetake T, Sasai S, Zhen YX, Tagami H. Effects of silicone gel sheet on the stratum corneum

hydration. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;13:157–9.

10. Baum TM, Busuito MJ. Use of glycerine-based gel sheeting in scar management. Adv

Wound Care. 1998;11:40–3. [

11. Niessen FB. The use of silicone occlusive sheeting (Sil-K) and silicone occlusive gel

(Epiderm) in the prevention of hypertrophic scar formation. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1998;102:1962–72. [

12. Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, Hobbs FD, Ramelet AA, Shakespeare PG, et al.

International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstruc Surg.

2002;110:560–3. [

13. Berman B, Flores F. Comparison of a silicone gel filled cushion and silicone gel sheeting for

the treatment of hypertrophic or keloid scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:484–90. [

14. Carney SA, Cason CG, Gowar JP. Cica care gel sheeting in the management of hypertrophic

scarring. Burns. 1994;20:163–7. [

15. Perkins K, Davey RB, Wallis KS. Silicone gel: A new treatment for burn scars contractures.

Burns Incl Therm Inj. 1983;9:201–6. [

16. Mercer NS. Silicone gel in the treatment of keloid scars. Br J Plast Surg. 1989;42:83–8.

[

17. Dockery GL. Treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars with silastic gel sheeting. J Foot

Ankle Surg. 1994;33:110–9. [

18. Cruz-Korchin NI. Effectiveness of silicone sheets in the prevention of hypertrophic breast

scars. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:345–8. [

19. Gibbons M, Zuker R, Brown M, Candlish S, Snider L, Zimmer P. Experience with silastic

gel sheeting in pediatric scarring. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1994;15:69–73. [

20. Borgognoni L, Martini L, Chiarugi C, Gelli R, Reali UM. Hypertrophic scars and keloids:

Immunophenotypic features and silicone sheets to prevent recurrences. Ann Burns Fire

Disasters. 2000;8:164–6.

21. Nikkonen MM, Pitkanen JM, Al Qattan MM. Problems associated with the use of silicone

gel sheeting for hypertrophic scars in the hot climate of Saudi Arabia. Burns. 2001;27:498–500.

[

Articles from Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery are provided here courtesy of

Medknow Publications

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

A review of the use of adapalene for the treatment of acne vulgaris

Atrophic Acne Scarring A Review of Treatment Options

Effective Treatments of Atrophic Acne Scars

Magnetic Treatment of Water and its application to agriculture

Kinesio taping compared to physical therapy modalities for the treatment of shoulder impingement syn

Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Hepatitis

Introduction to the Magnetic Treatment of Fuel

65 935 946 Laser Surface Treatment of The High Nitrogen Steel X30CrMoN15 1

APA practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder

Flashback to the 1960s LSD in the treatment of autism

The term therapeutic relates to the treatment of disease or physical disorder

Friday's Treatment of Social Issues

Treatments of Alcoholism

Presentation 5 Psychological Aspects of Treatment of the S

7 77 93 Heat and Surface Treatment of Hot Works for Optimum Performance

Drugs for treatment of malaria

Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of dysplastic hip with Perthes like deformities

14 Treatment of Strokes

więcej podobnych podstron