Diverted Total Synthesis in

Medicinal Chemistry Research

Luke Zuccarello

December 14, 2005

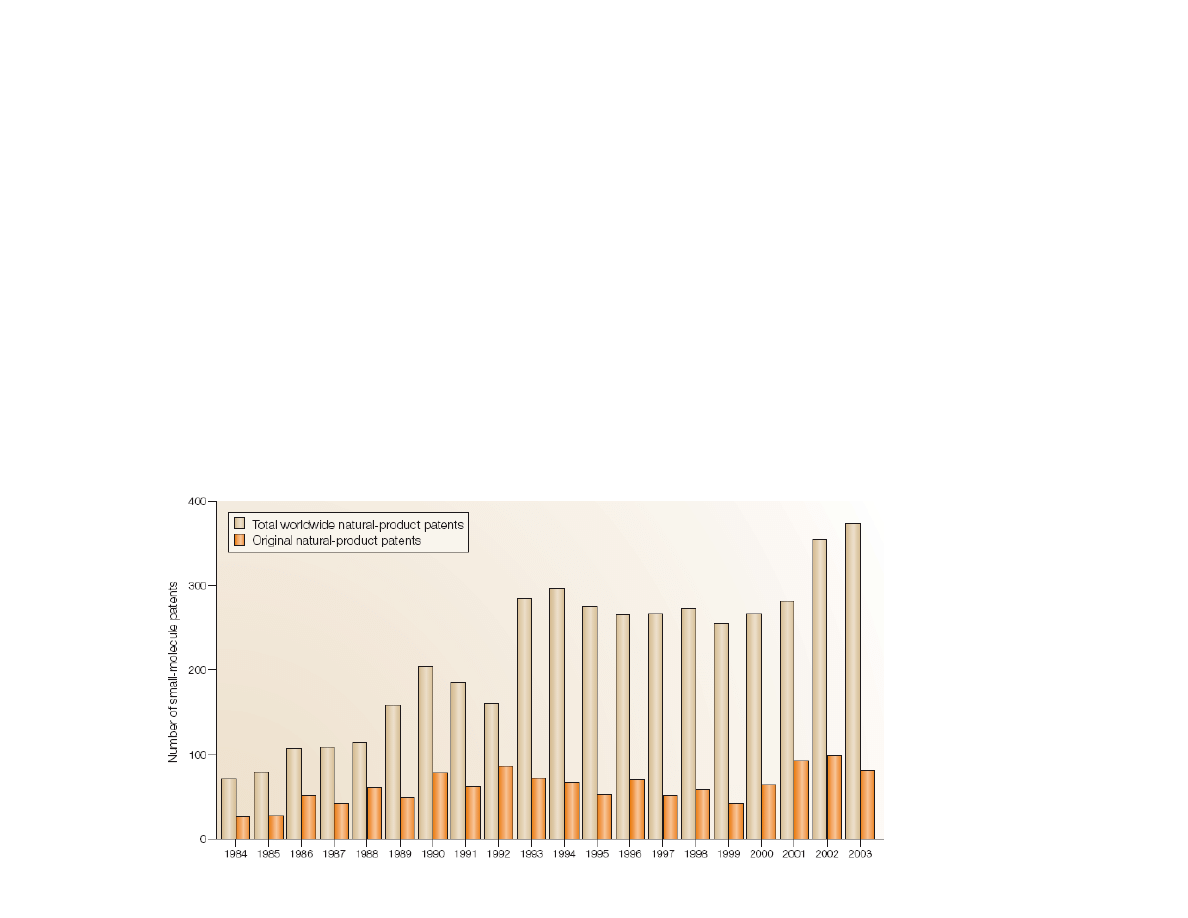

Natural Products in Drug Therapy

• About 50% of drugs in clinical use today are natural

products, or chemically modified natural products

• Sources for natural product-derived drugs: (a) directly

from plant/animal, (b) genetic engineering, (c) semi-

synthesis (d) total synthesis

• Pharmaceutical research involving natural products was

stagnant/declining in 1990s, but increasing again in the

current decade

Koehn, F. E.; Carter, G. T.

Nat. Rev. Drug Disc.

2005, 4, 206.

Why the Decline Natural Products Research

in the Pharmaceutical Industry?

• Advent of high-throughput screening (HTS) allows more compounds

to be assessed for hits

• Natural products are typically extracted as mixtures (10-100s) of

compounds with largely varying concentrations, which can (a) make

identifying actual active compound more difficult; (b) add more work

in additional purification; (b) give poor results with catalysis/binding

assays

• Combinatorial chemistry/synthetic libraries are better suited for HTS

than natural product extract libraries, leading to an industrial trend

toward purely synthetic libraries

• Major decline in “big pharma” research on infectious disease

therapy

Koehn, F. E.; Carter, G. T. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2005, 4, 206.

Problems with Combinatorial Libraries in

Drug Screening

• Libraries designed to maximize number of compounds

screened (10

6

) may yield no hits due to lack of

biochemically relevant structure

• Compounds that are hits are often unselective in their

binding/activity

• Overall, R&D expectations have not been realized

Koehn, F. E.; Carter, G. T. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2005, 4, 206.

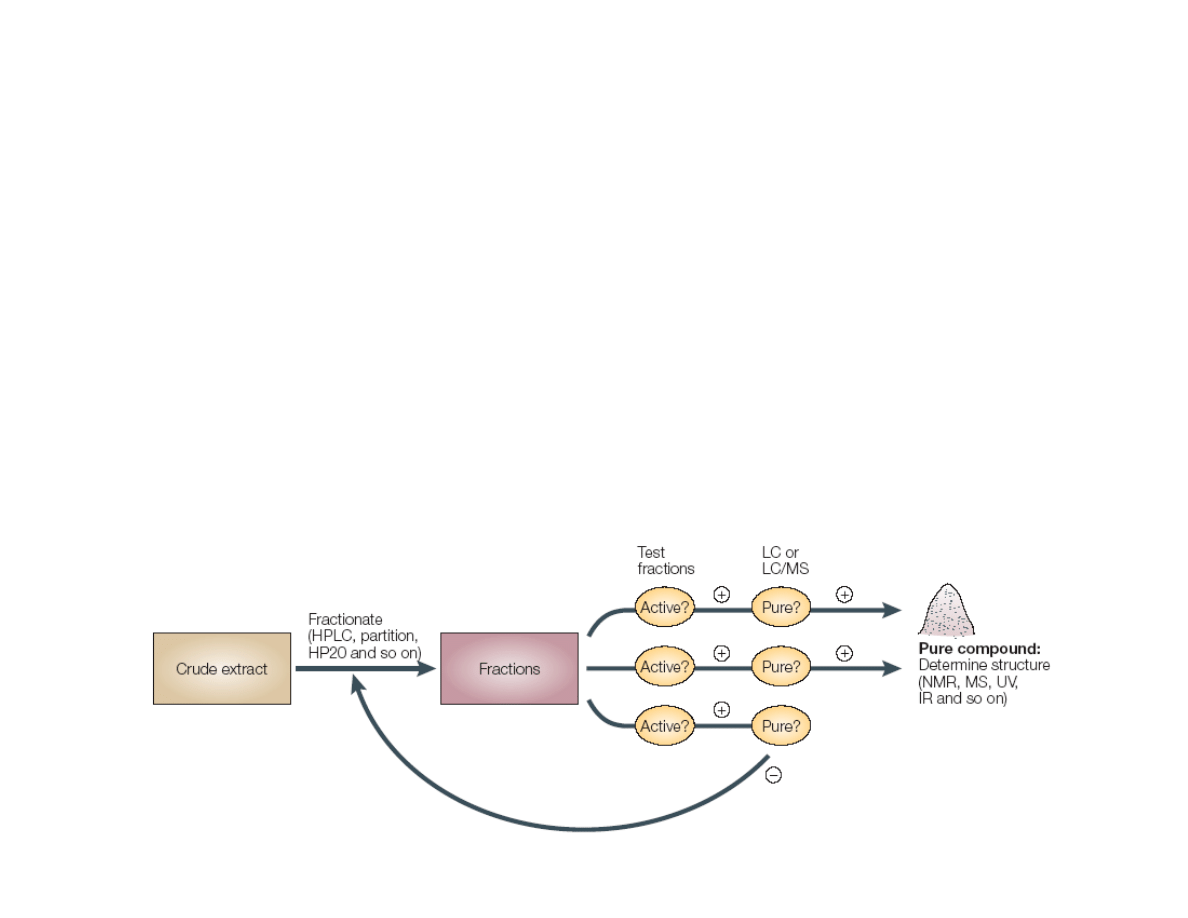

Advantages of Natural Product Libraries in

Drug Screening

•

Recent advances in purification and analysis technology allows for natural

product library HTS

•

Natural products have been selected through evolution to interact with

macromolecules (eg proteins)

•

This includes natural selection of 3D structures and pharmacophores

•

Many natural products are “priveleged structures,” allowing them to interact

with multiple biological targets in various types of organisms

•

This is reinforced by research in the last 5-10 years which shows that the

protein fold space found in nature is smaller than previously predicted

•

At the same time, natural products are typically specific in their ability to

modulate protein-protein interactions (signal transduction, immune

response, mitosis, apoptosis)

•

Natural products typically do not violate Lapinski’s “Rule of Five”

Koehn, F. E.; Carter, G. T. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2005, 4, 206.

Zhang, C.; DeLisi, C. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 284, 1301.

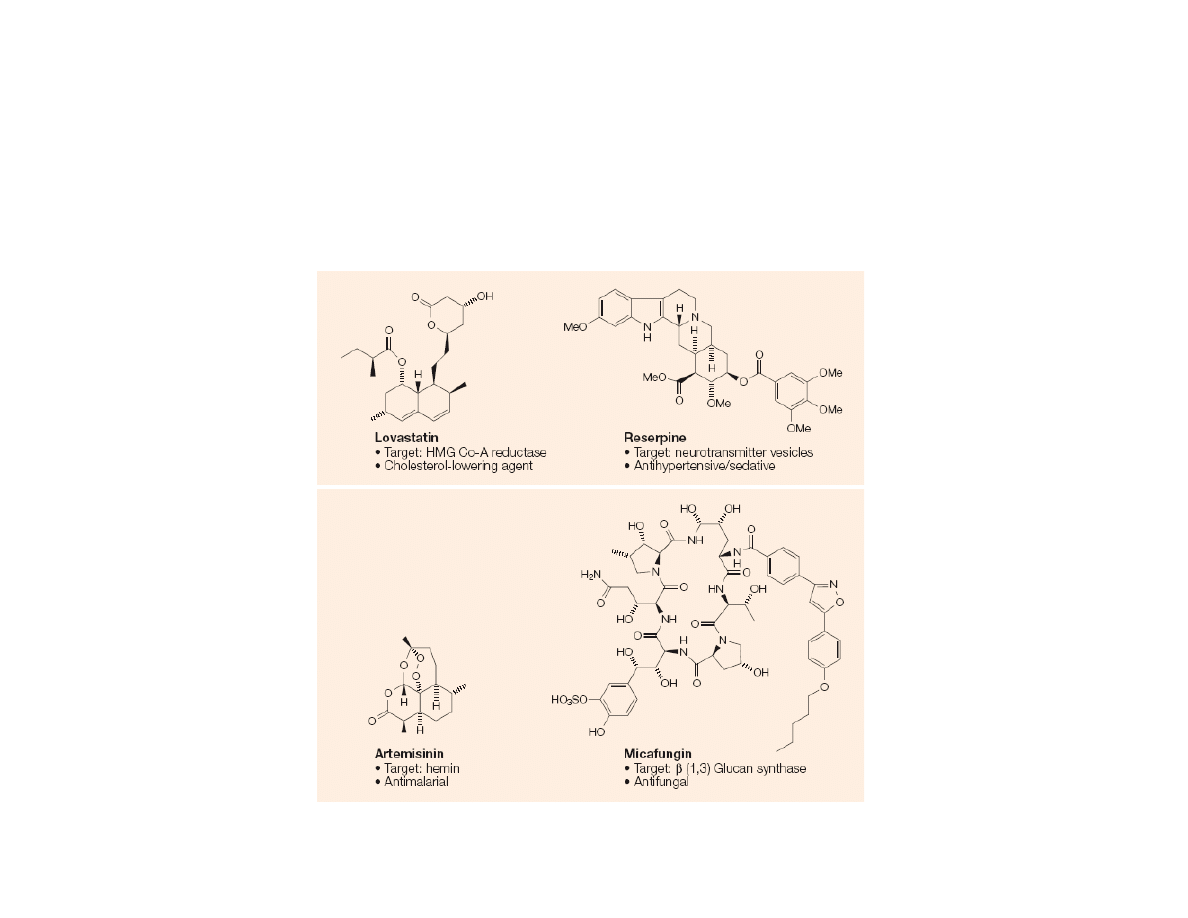

Types of Natural Product Derived

Therapeutics

1) Unaltered natural product as a drug

Koehn, F. E.; Carter, G. T. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 2005, 4, 206.

Types of Natural Product Derived

Therapeutics

2) Semi-synthetic analog: chemical manipulation

(typically functional group interconversion) of a natural

product

Example: exchanging a sugar on a natural product

Possible disadvantages: supply of natural product,

limitations to available analogues due to native

functionality

Paterson, I.; Anderson, E. Science 2005, 310, 451.

Njardarson, J. T. ; Gaul, C.; Shan, D.; Huang, X.-Y.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1038.

.

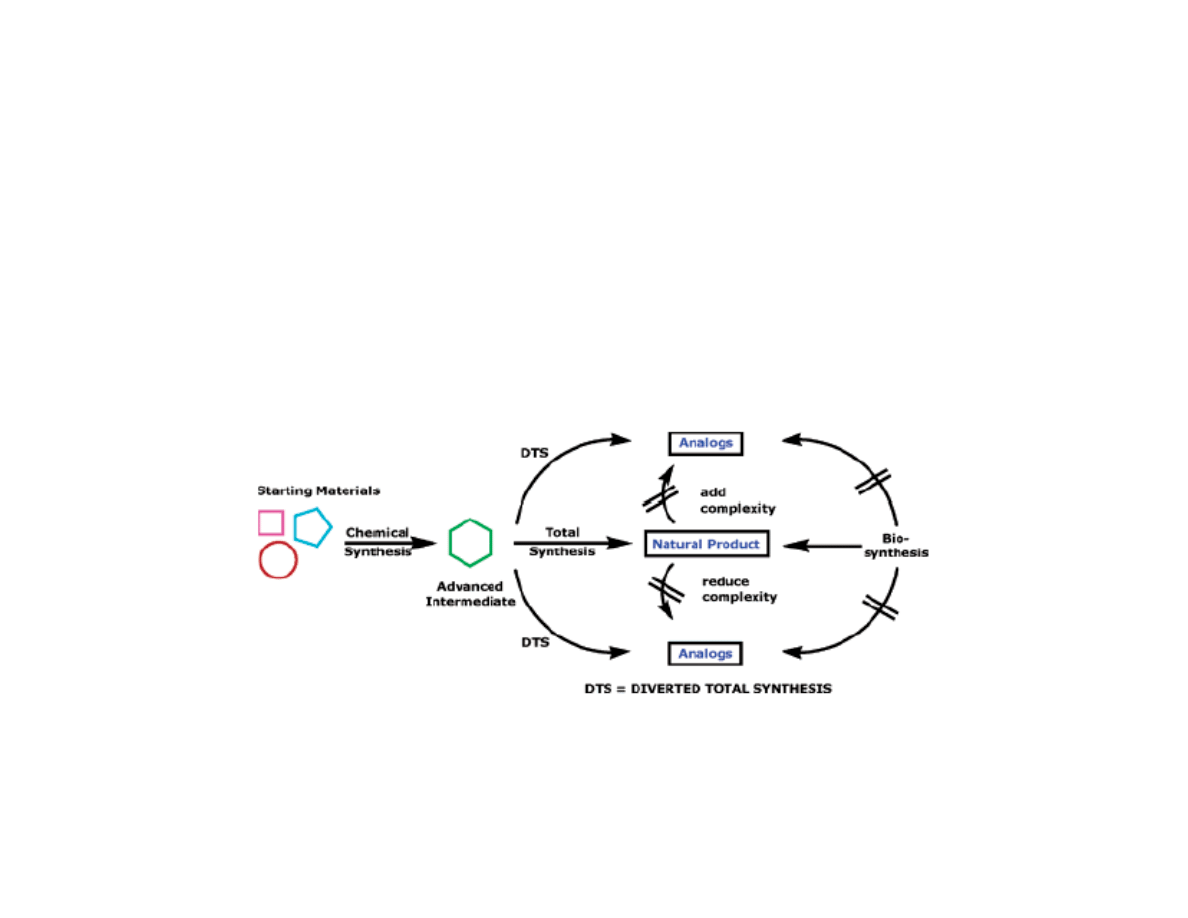

Types of Natural Product Derived

Therapeutics

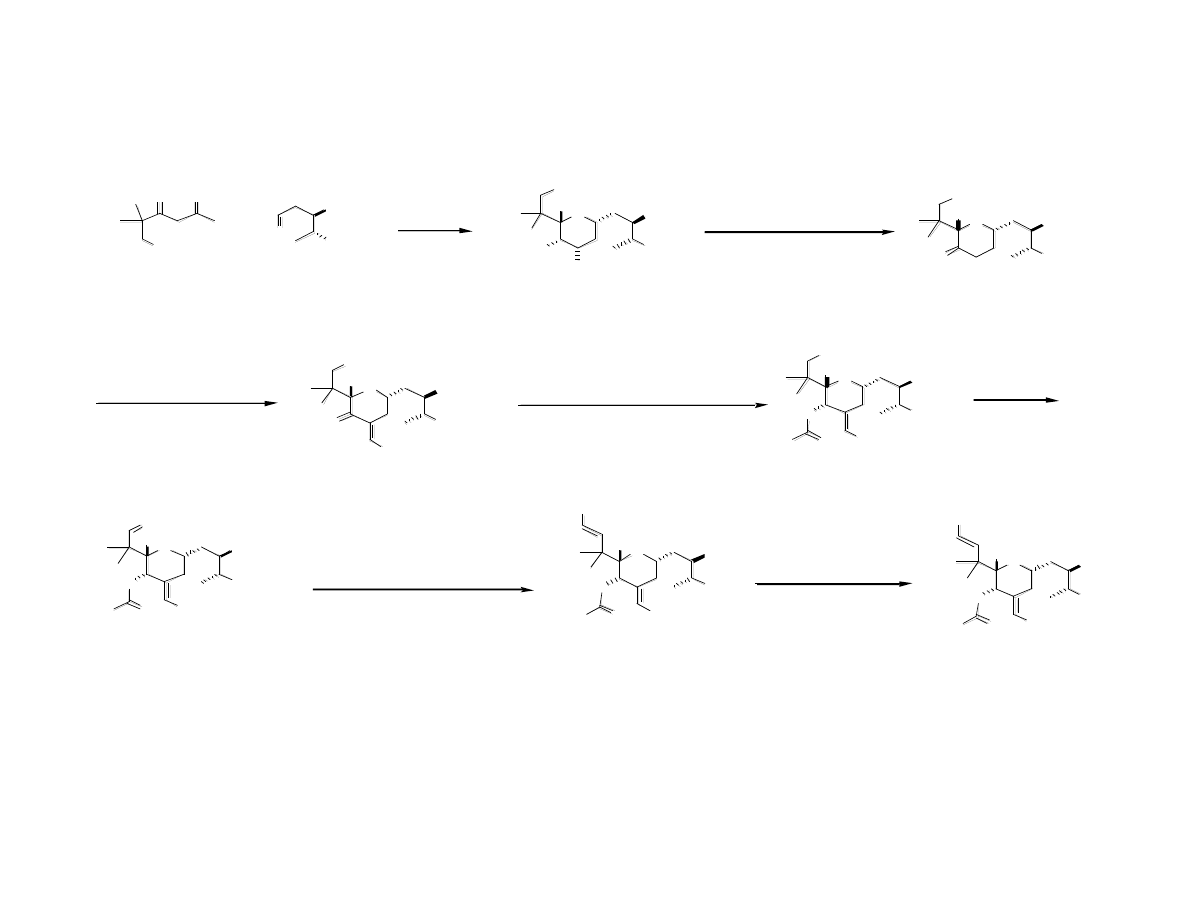

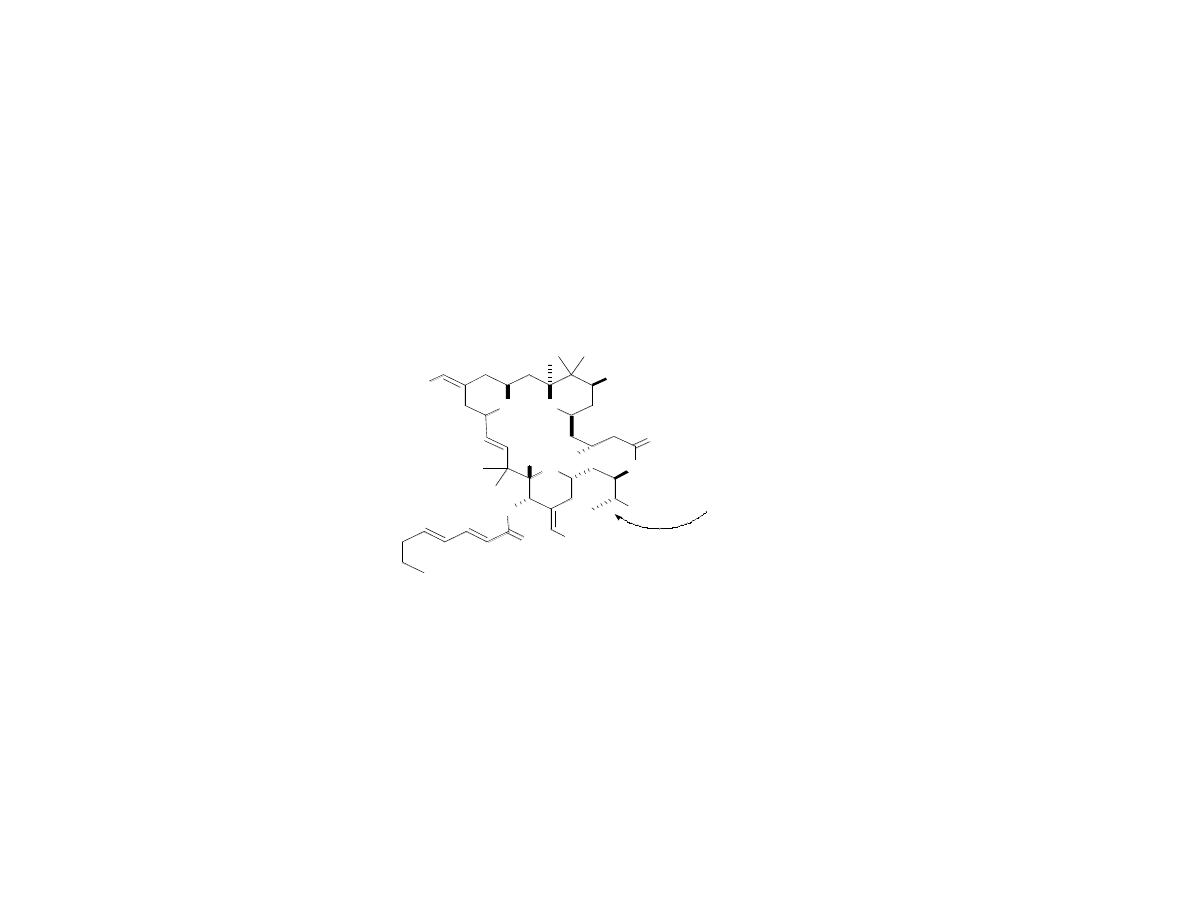

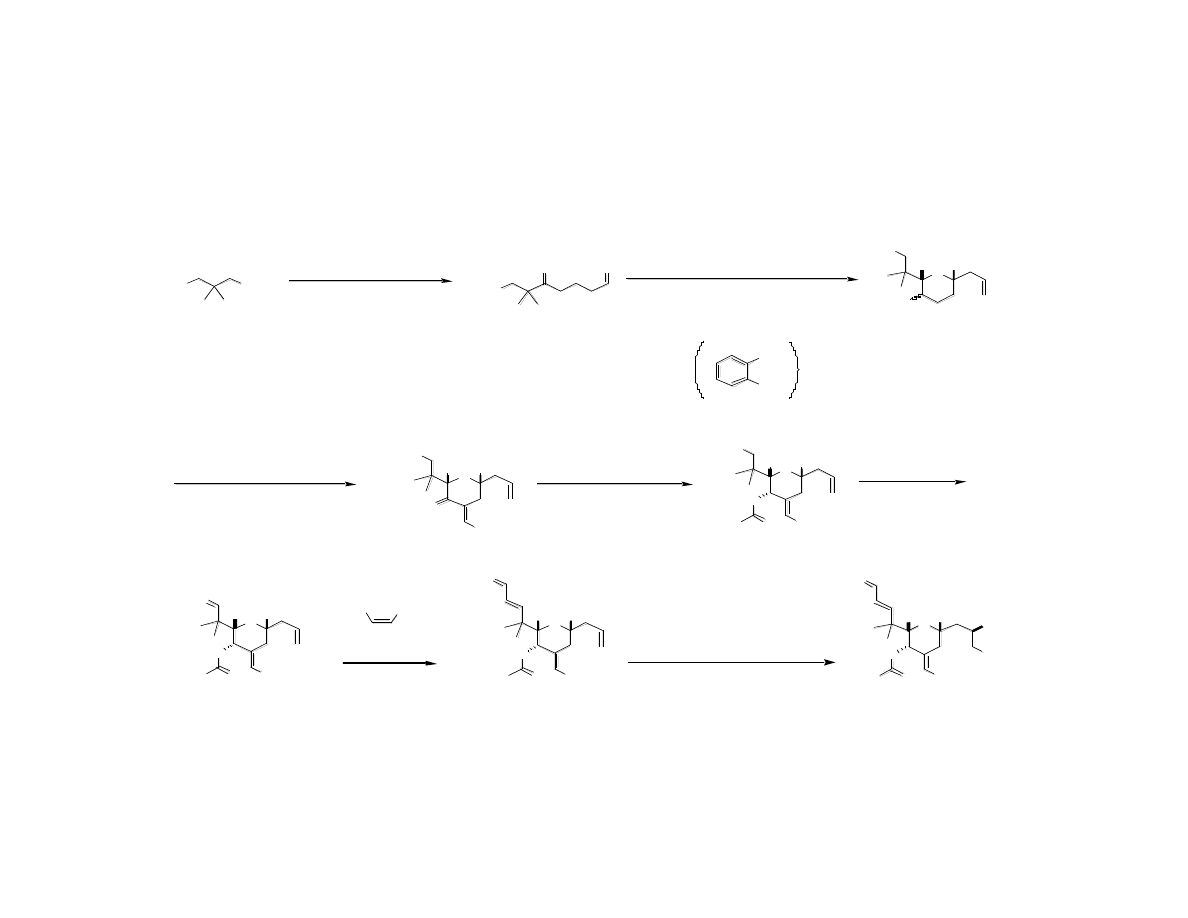

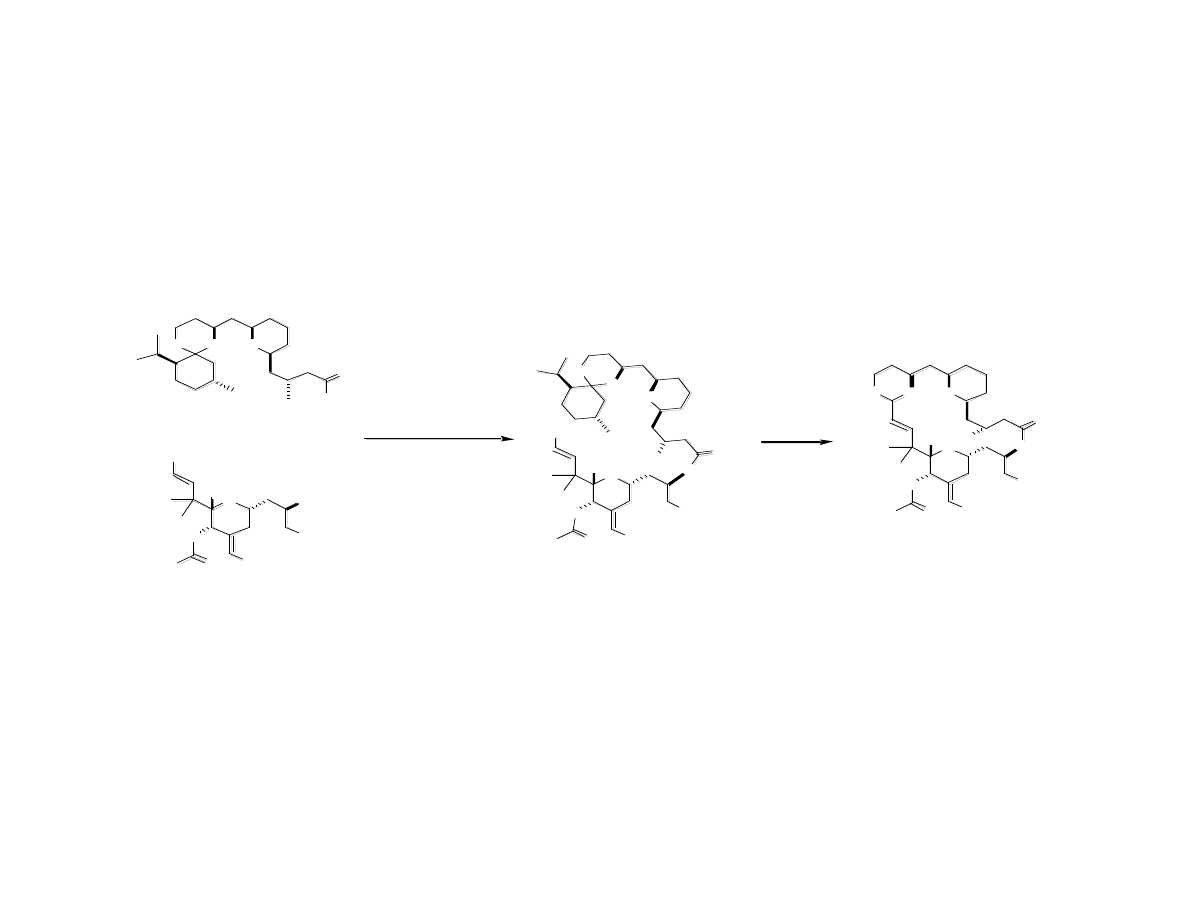

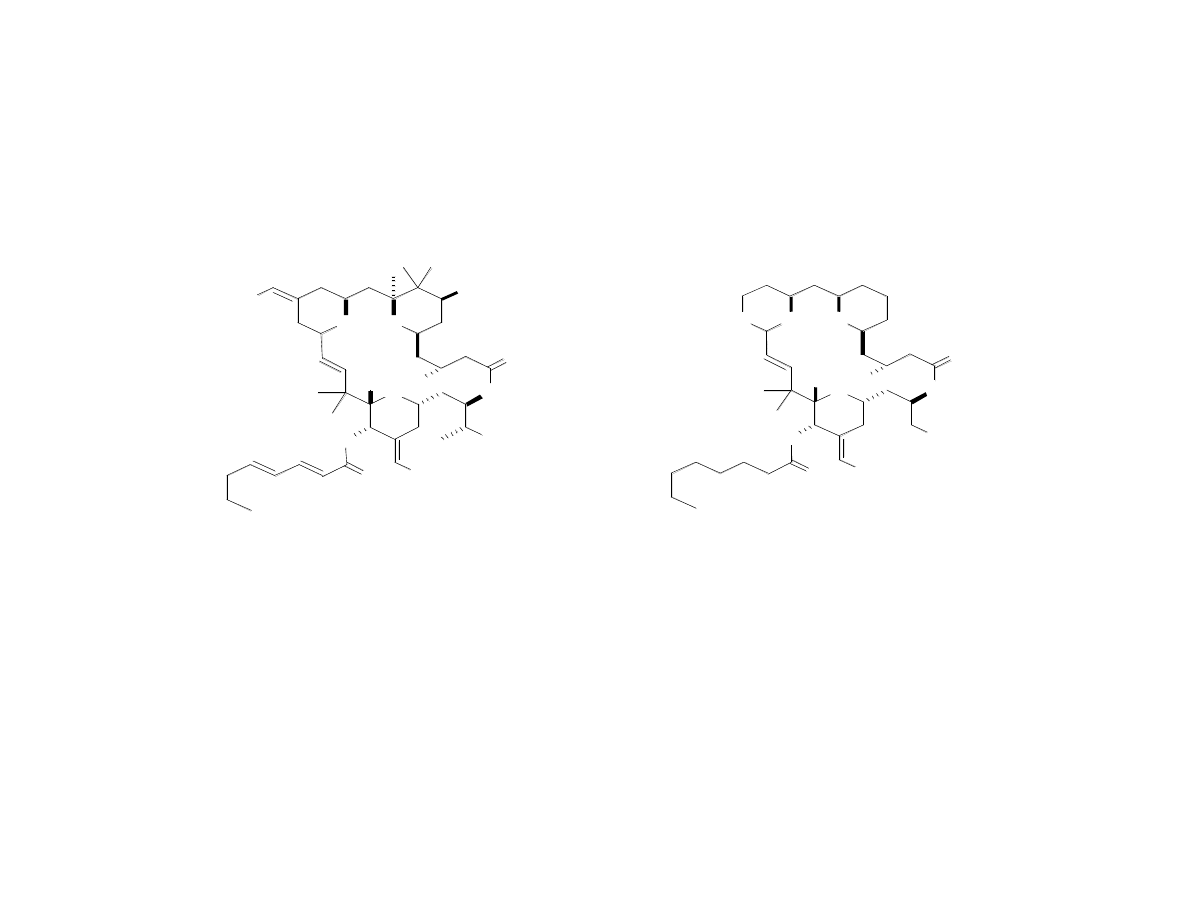

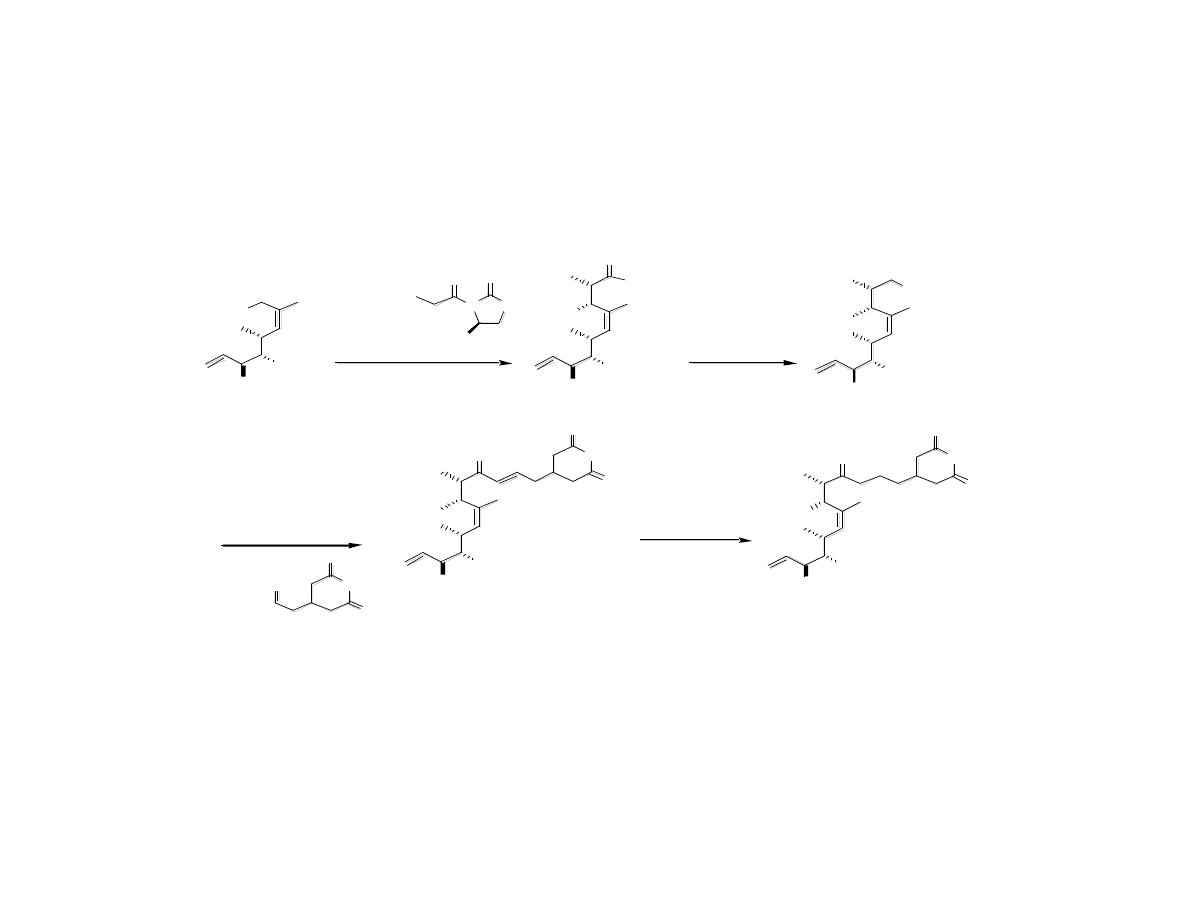

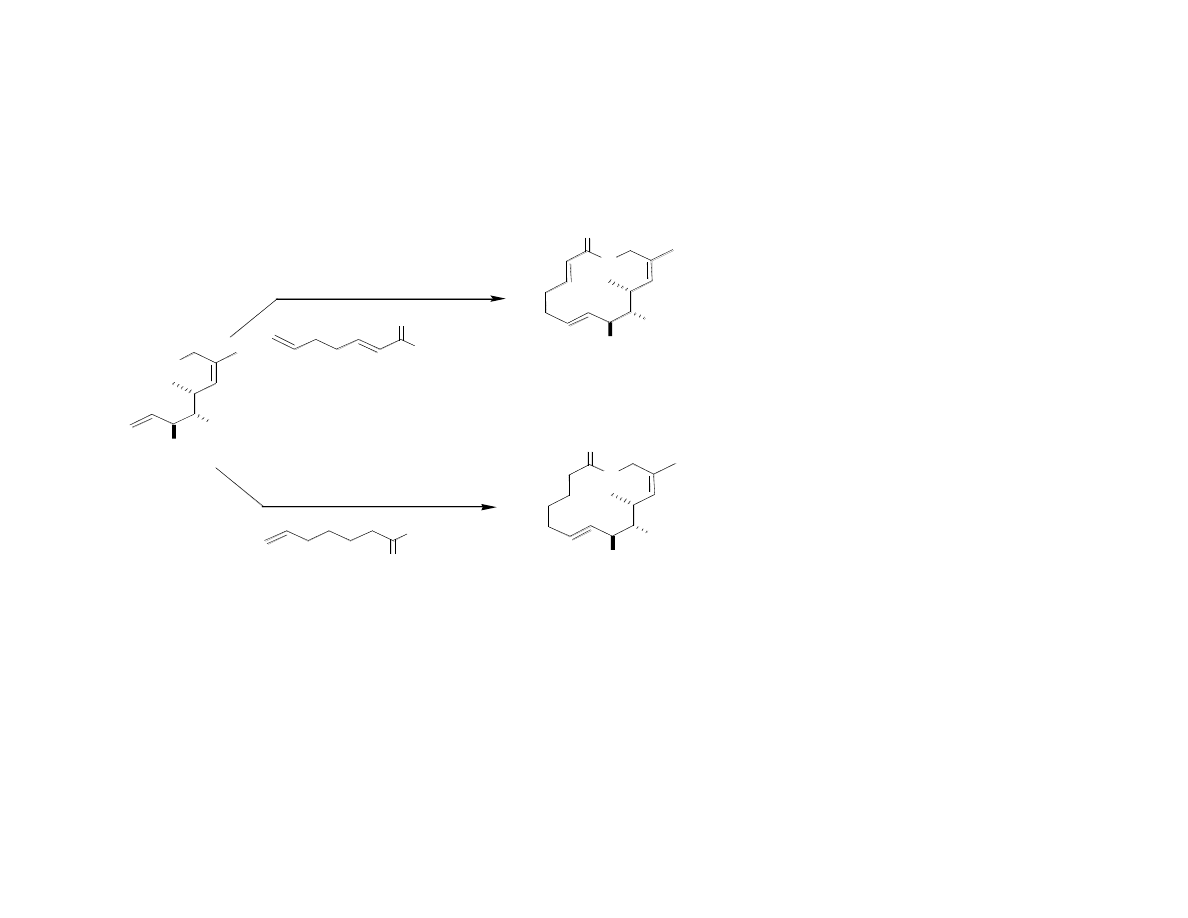

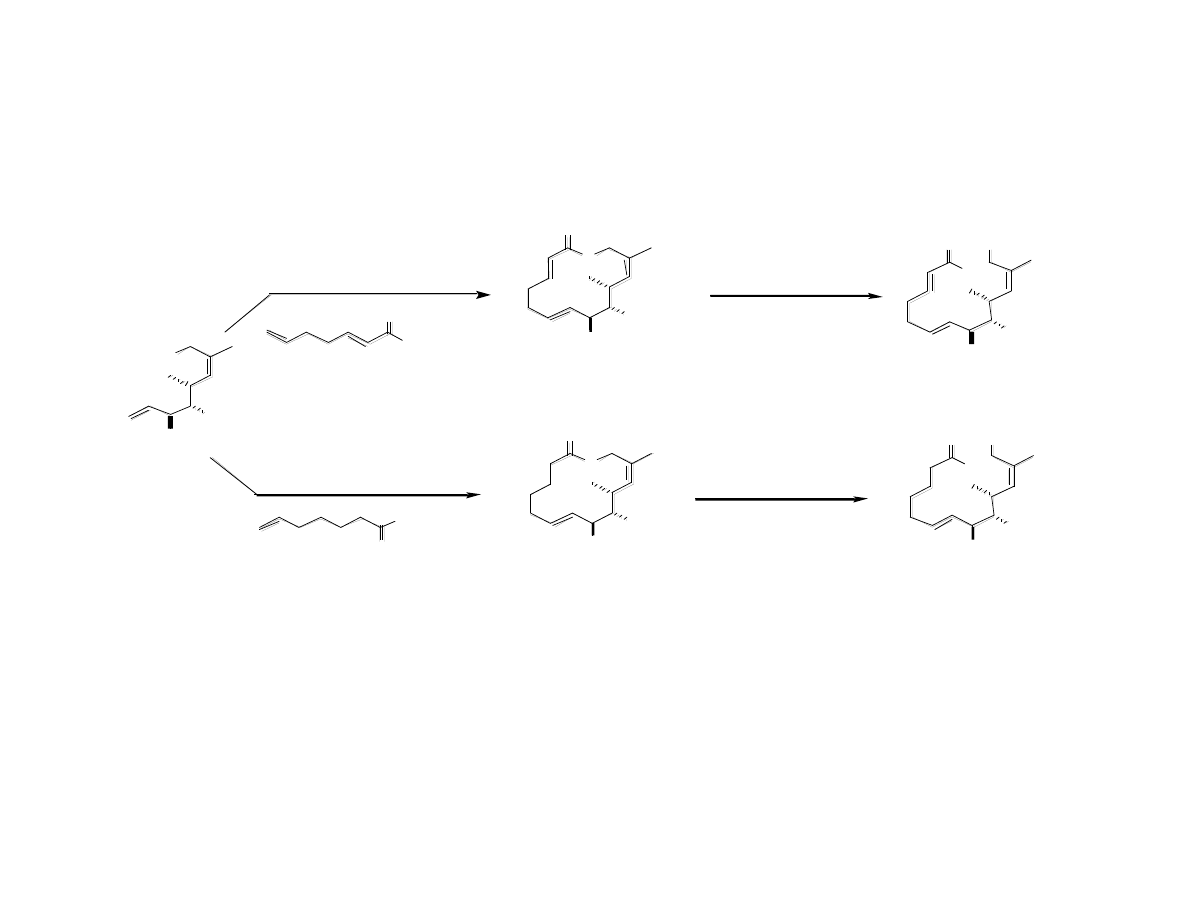

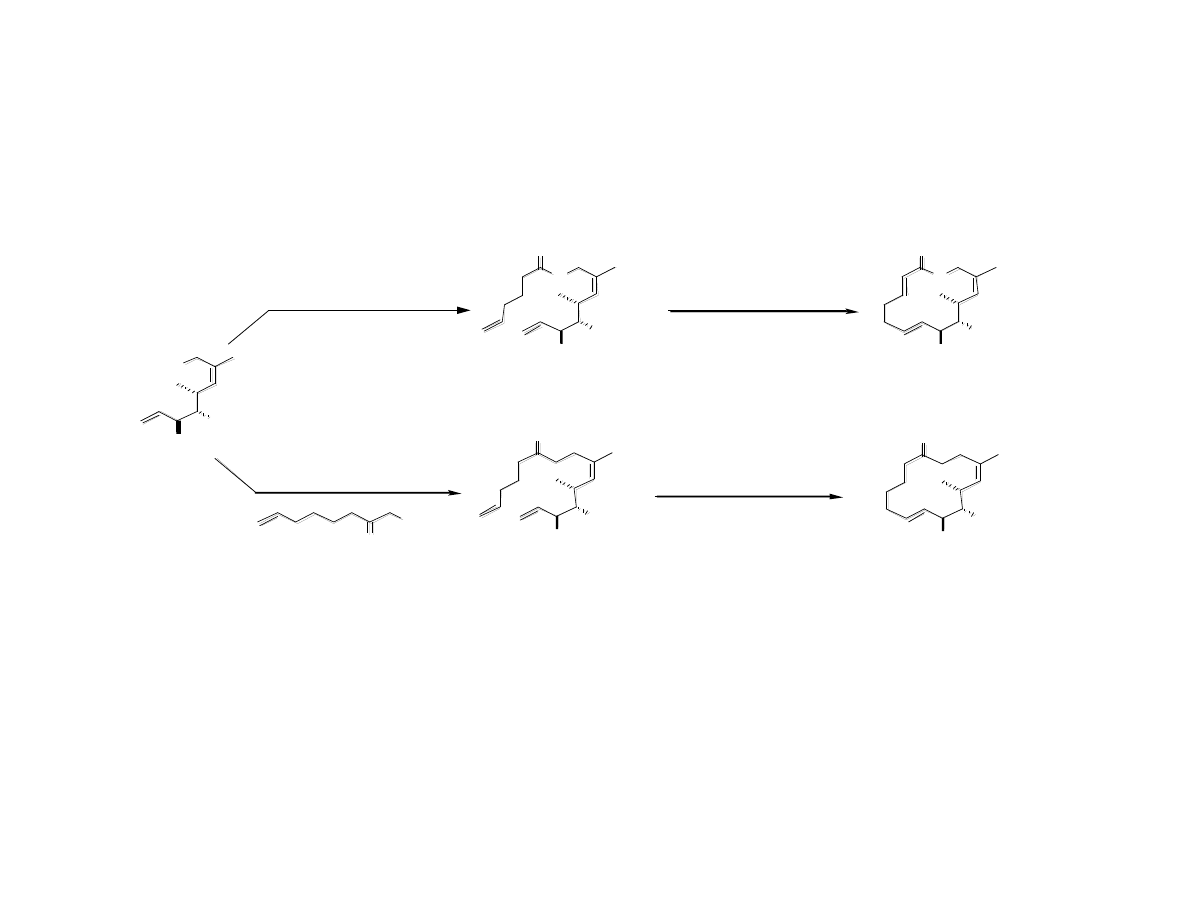

3) Analogs from diverted total synthesis

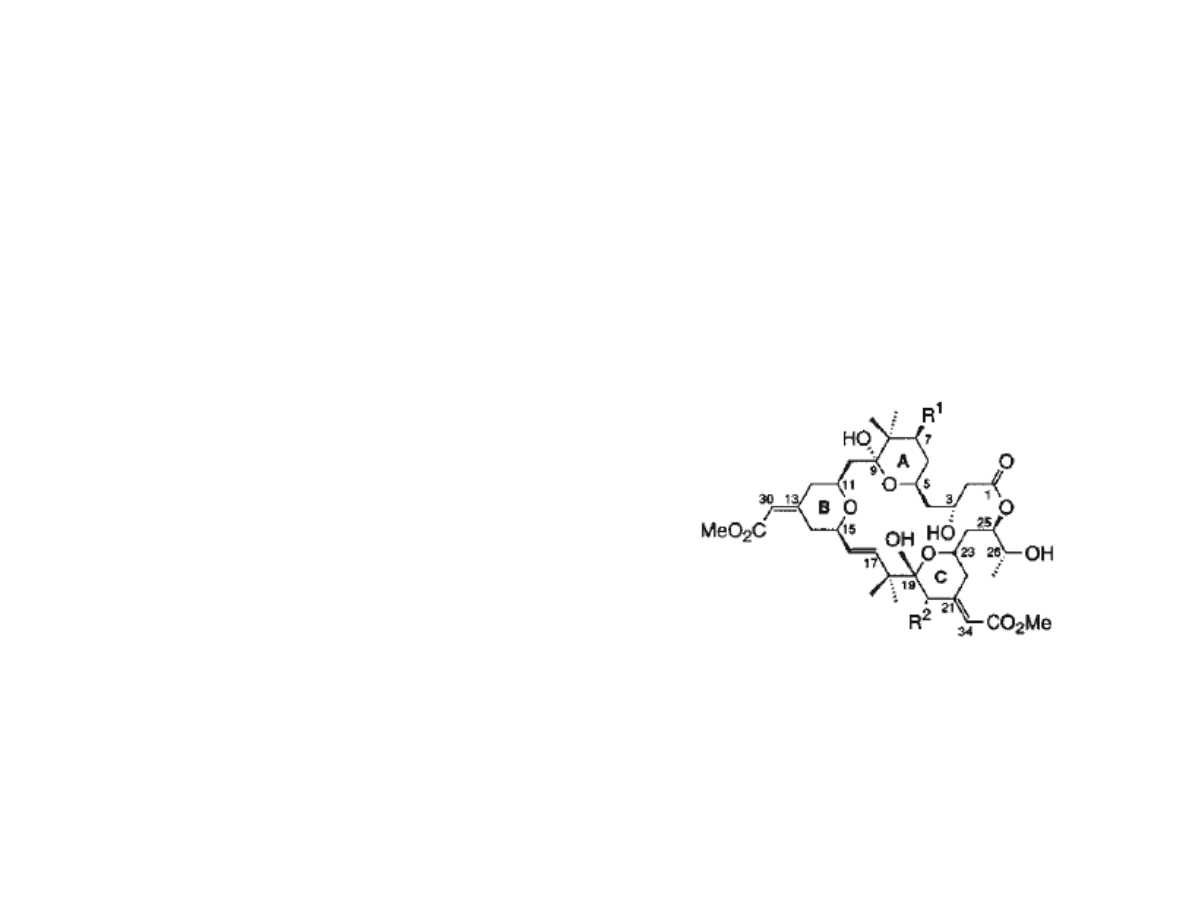

Bryostatin: Potent Anti-cancer Natural

Product

•Macrocyclic lactones from the marine invertebrate bugula neritina, first

isolated in 1968; fully characterized in 1982

•Bryostatins consist of at least 20 members, which vary at R

1

and R

2

•Isolated yields have varied between 10

-3

% to 10

-8

%

•Anti-cancer properties: apoptosis induction,

immune system booster, reverses multiple

drug resistance, synergistic with other drugs

•Currently in phase I and II clinical trials

Wender, P. A.; Hinkle, K. W.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B. Med. Res. Rev. 1999, 19, 388.

Suffness M, Newman DJ, Snader K. In: Scheuer PJ, editor. Bioorganic marine chemistry 3. New York: Springer-

Verlag Publishers. pp. 131–168.

Pettit, G.R.; Herald, C.L.; Doubek, D.L.; Herald, D.L.; Arnold, E.; Clardy, J. J Am Chem Soc 1982, 104, 6846.

Pettit, G.R. J Nat Prod 1996, 59, 812.

Pettit GR. Fortschritte 1991, 57, 153.

Bryostatin: Binding to PKC

Paul A. Wender, P. A.; De Brabander, J.; Harran, P. G.; Jimenez, J.-M.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B.;

Park, C.-M.; Shiozaki, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 4534.

Wender, P. A.; Cribbs, C. M.; Koehler, K. F.; Sharkey, N. A.; Herald, C. L.; Kamano, Y.; Pettit, G. R.;

Blumberg, P. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988, 85, 7197.

http://www.stanford.edu/group/pawender/html/synth.html

•Protein Kinase C (PKC) family of serine/threonine kinases is involved in signal

transduction, and is important in the biochemistry of cancer

•Bryostatin binds to PKC w/ high affinity

Bryostatin: Previous Total Synthesis

•Bryostatin 7 (R

1

=R

2

= OAc) : Masamune, 1990

•Bryostatin 2 (R

1

= OH, R

2

= O

2

CC

7

H

11

) : Evans, 1998

•Both total synthesis require >60 steps, making them untenable in process

Kageyama, M.; Tamura, T.; Nantz, M. H.; Roberts, J. C.; Somfai, P.; Whritenour, D. C.; Masamune, S.

J. Am. Chem. Soc.1990, 112, 7407.

Evans, D. A.; Carter, P. H.; Carreira, E. M.; Prunet, J. A.; Charette, A. B.; Lautens, M. Angew Chem Int.

Ed. 1998, 37, 2354.

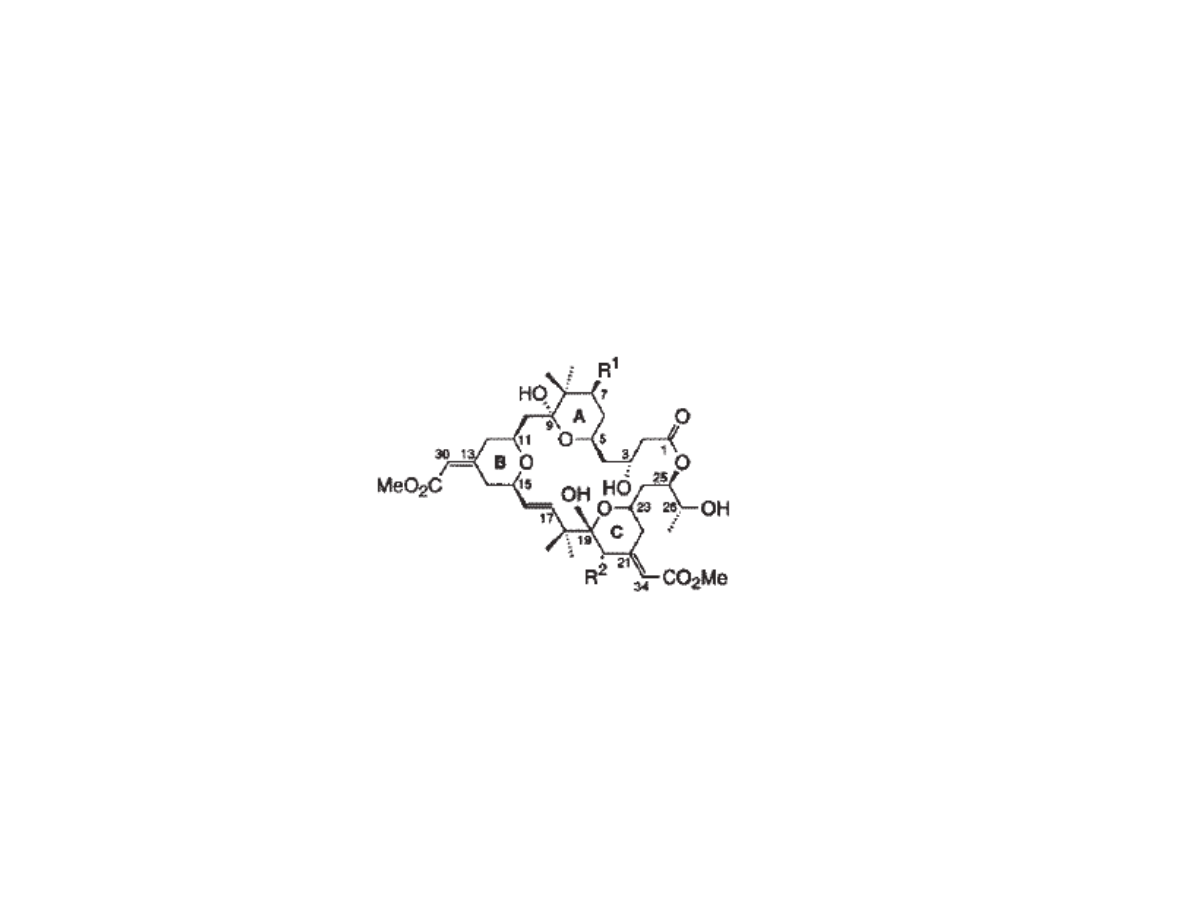

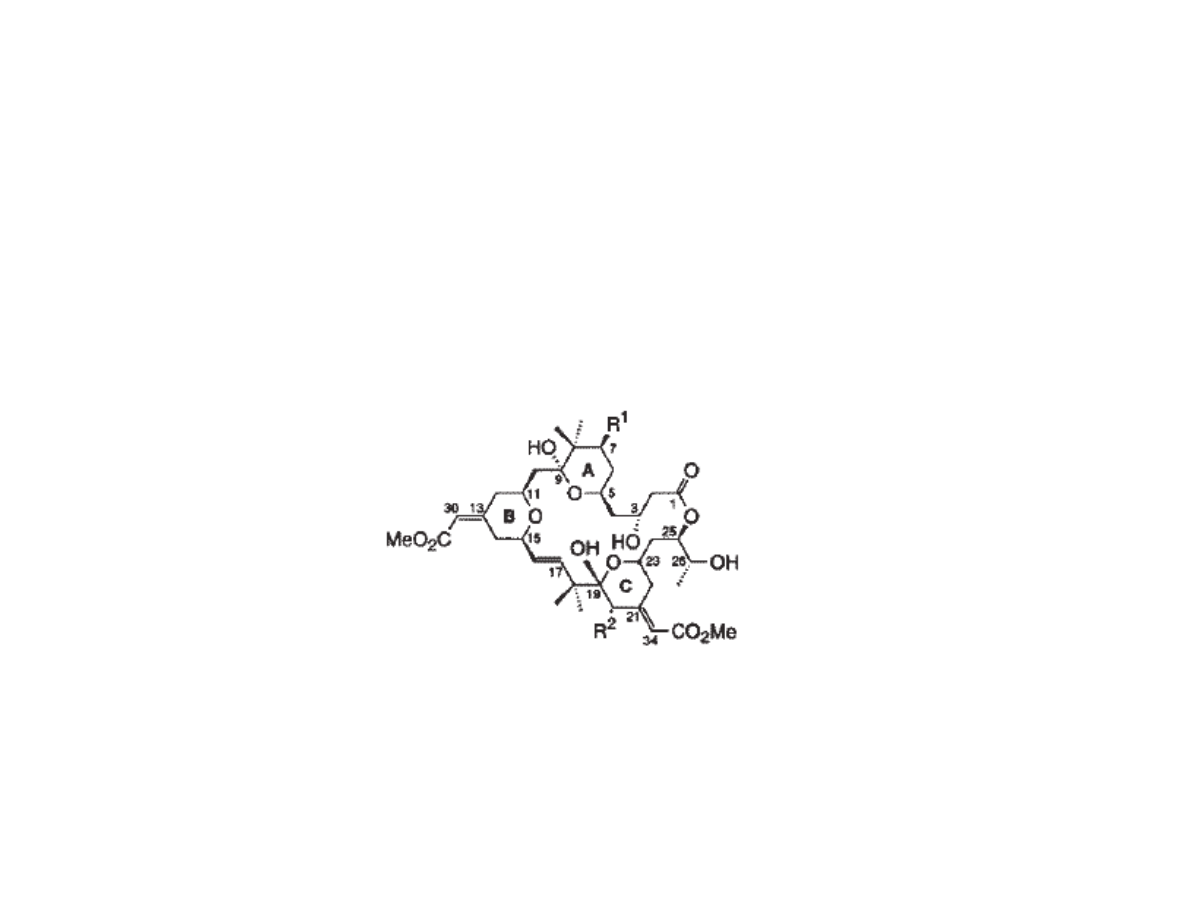

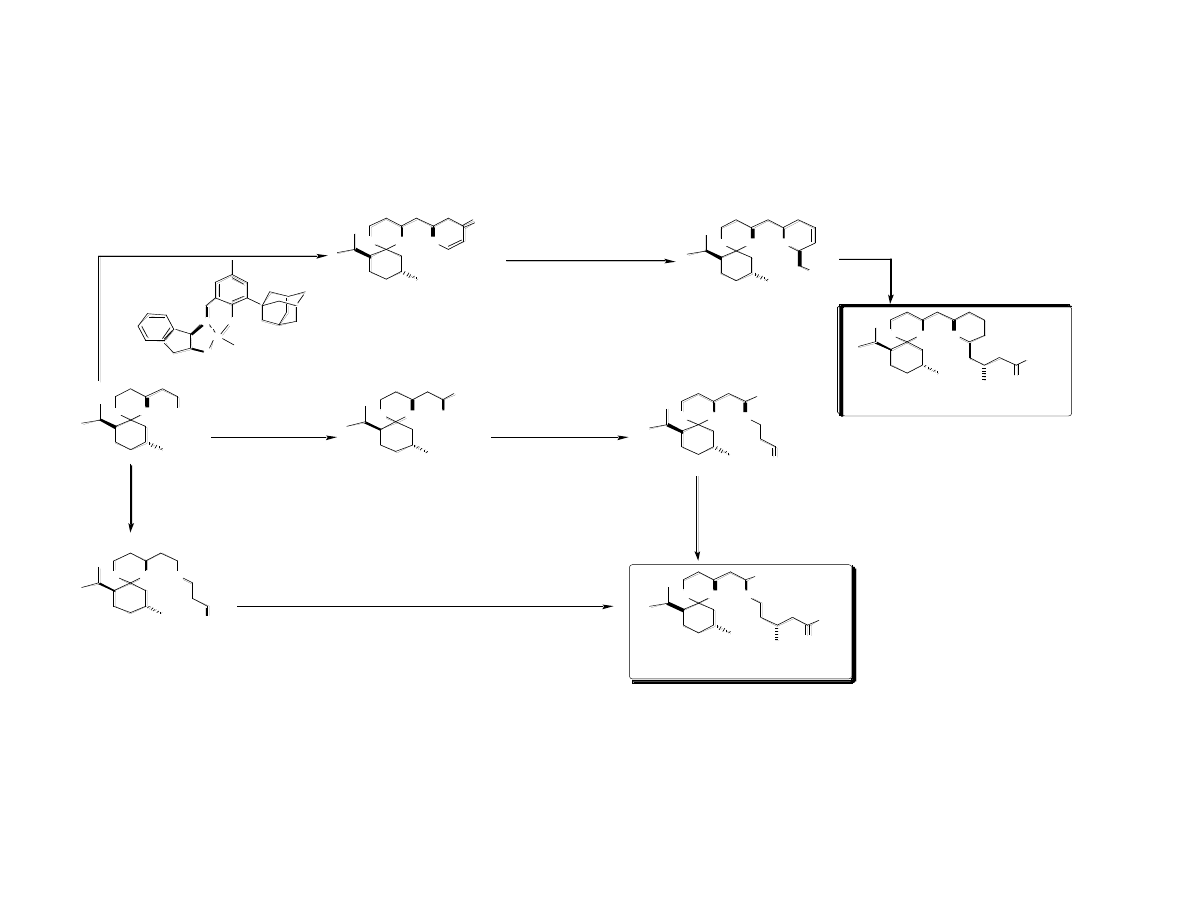

Wender’s Bryolog Targets

Wender, P. A.; Hinkle, K. W.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B. Med. Res. Rev. 1999, 19, 388.

Paul A. Wender, P. A.; De Brabander, J.; Harran, P. G.; Jimenez, J.-M.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B.;

Park, C.-M.; Shiozaki, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 4534.

http://www.stanford.edu/group/pawender/html/synth.html

•Hypothesis by Wender et al. (1988): pharmacophore region of byrostatin include

C1, C19, and C26 oxygen atoms (bryostatin 1 K

i

= 1.35 nM)

O

O

O

H

H

H

H

O

O

O

O H

O

R

3

R

1

C

7

H

1 5

O

C O

2

Me

A) R

1

= OH , R

2

= H, R

3

= OH

B) R

1

= OH , R

2

= H, R

3

= OA c

C) R

1

= H, R

2

=OH , R

3

= O H

D) R

1

= H, R

2

= H , R

3

= OH

R

2

Sp ec ific A na log Ta rge ts

B

A

C

O

O

O

R

4

H

H

H

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

HO

C

7

H

1 5

O

C O

2

Me

B

C

E) R

4

= H

F) R

4

= t-B u

First Generation Sythesis of C Ring

O TBS

O

O

O

OP MB

OB n

+

4 ste ps

2 9%

fro m R -m e th y l la cta te

from me th yl i -p ro py l

ke ton e

O

OBn

OTB S

O H

H O

OM e

OPM B

1 ) Ph C OC l, D MA P; D MP

9 0 %

2 ) Sm I

2

9 0 %

O

OBn

OTB S

O

OM e

OPM B

1 ) L DA , CH OC O

2

M e

2 ) M sC l, TEA

3 ) D BU

7 0 %

O

OB n

OTBS

O

OMe

OP MB

C O

2

M e

1 ) Na B H

4

, C eC l

3 ,

-2 0 de g . C

2 ) C

7

H

1 5

CO

2

H , Ya m ag u ch i co n d' ns

9 3%

O

O Bn

OTB S

O

OM e

O PM B

CO

2

M e

C

7

H

15

O

1) H F/p yr.

2) D M P

86 %

O

OB n

O

O

OMe

OP MB

C O

2

M e

C

7

H

1 5

O

1 ) a ll yl -BE t

2

, E t

2

O, -1 0 de g . C

2 ) A c

2

O, DM AP

3 ) Os O

4

, N M O

4 ) P b( OAc )

4

, TE A; the n DB U

7 6 %

O

OB n

O

O Me

OP MB

C O

2

M e

C

7

H

1 5

O

C H O

1 ) D D Q

2 ) H F, CH

3

C N , H

2

O

7 5 %

O

OBn

O

OH

OH

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

1 5

O

C H O

Paul A. Wender, P. A.; De Brabander, J.; Harran, P. G.; Jimenez, J.-M.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B.;

Park, C.-M.; Shiozaki, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 4534.

First Generation Sythesis of “Spacer”

Region

Wender, P. A.; Hinkle, K. W.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B. Med. Res. Rev. 1999, 19, 388.

Wender, P. A.; Baryza, J. L.; Bennett, C. E.; Bi, F. C.;. Brenner, S. E.; Clarke, M. O.; Horan, J. C.; Kan, C.; Lacôte, E.;

Lippa, B.; Nell, P. G.; Turner, T. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13648.

O

OH

O

1 ) S we rn

2 ) t-B uL i

3 ) D M P

4 ) L u ch e re d u ctio n

d r = 6 :1, 4 6%

O

OH

O

t-B u

1 ) t-Bu OK , a ll yl Br

2 ) 9- BBN ; H

2

O

2

, N a OH

3 )D MP

7 2%

O

O

O

t-Bu

O

1 ) (- )-Ip c

2

B-C H

2

C H=C H

2

2 ) TB SC l, i mi d.

3 ) ca t. KM nO

4

, N a IO

4

4 2 %

1 ) N a H, a ll yl Br 7 6%

2 ) 2 ) 9 -BB N ; H

2

O

2

, N a OH

3 )D M P

7 2 %

1 ) (-)- Ipc

2

B -C H

2

C H =C H

2

2 ) TBS Cl , im id .

3 ) ca t. K Mn O

4

, N aIO

4

4 2%

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

R

O

OH

TB SO

R = H , t-B u

6 0% fro m p e nta n etri o l

1 ) Sw e rn

2 ) D an is he fsk y's d i en e

O

O

N

Cr

Cl

O

O

O

O

th e n TFA

1 ) Lu ch e re du cti on

2 ) i-B uO CH =C H

2

, H g (OA c)

2

3 ) De ca n e , 1 5 0 d e g. C

7 6%

O

O

O

1 ) H

2

, Pd (OH )

2

2 ) (-)- Ip c

2

B -C H

2

C H =C H

2

3 ) TBS Cl , im id .

4 ) KM nO

4

, N a IO

4

4 9%

O

O

O

C H O

O

OH

TBS O

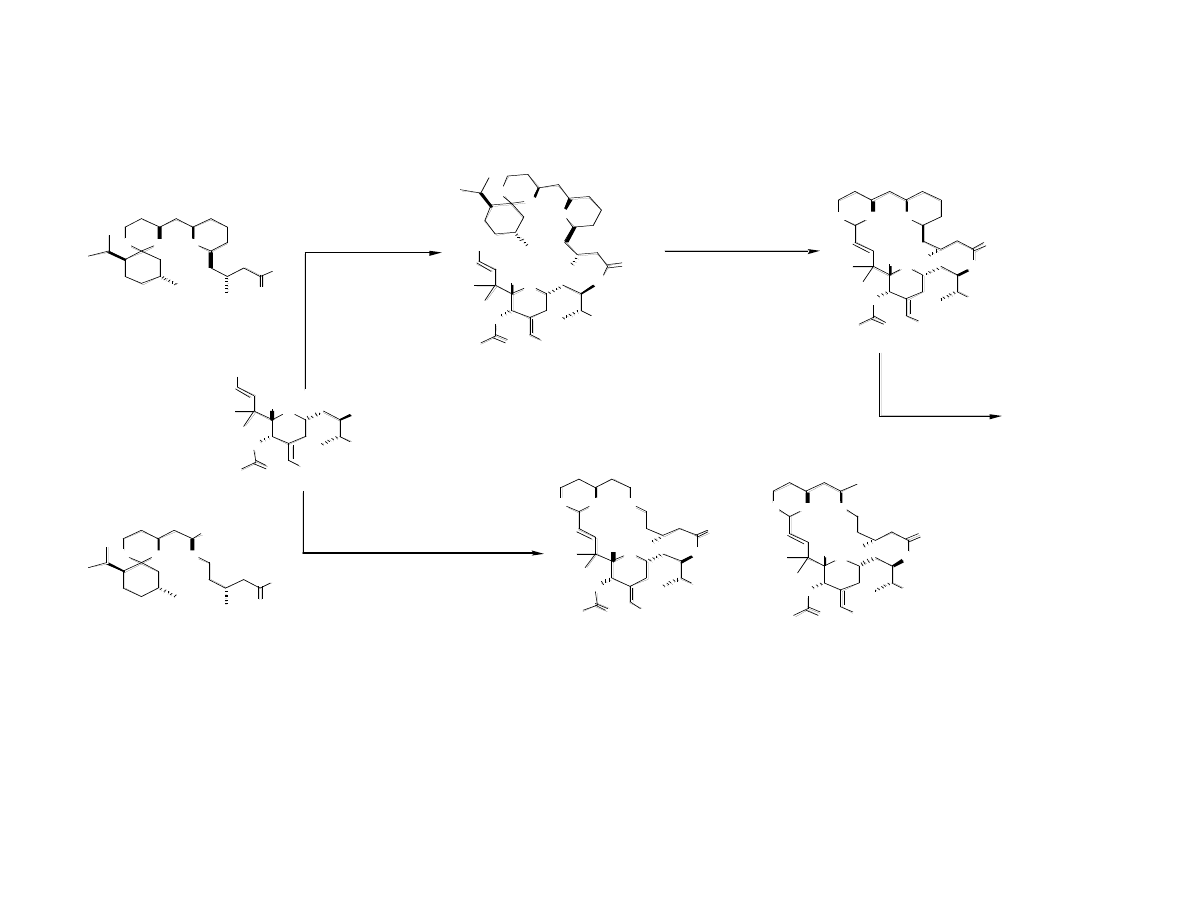

Completion of Analogs

O

O

O

O

OH

TB SO

O

OBn

O

OH

OH

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

1 5

O

CH O

1 ) Ya ma g uc hi 81 %

2 ) HF -py r. 81 %

O

O

O

H O

O

O

O

OB n

O

OH

CO

2

M e

C

7

H

1 5

O

C H O

1) Am be rl ist- 15 , rt, d i lu te

2) Pd (OH )

2

, H

2

88 %

O

O

O

H O

O

O

O

OR

O

OH

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

1 5

O

A c

2

O, DM AP

8 5 %

Bry ol o g A

R = H

K

i

= 3 .4 n M

Bry ol o g B

R = A c

K

i

= 2 9 7 n M

O

O

O

R

O

OH

TBS O

1 ) Y am a gu ch i

2 ) H F-p yr .

3 ) A mb e rli st-1 5 , r t, d il ute

4 ) P d( OH )

2

, H

2

R = H , t-Bu

O

O

O

H O

O

O

O

OH

O

O H

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

1 5

O

t-Bu

O

O

O

H O

O

O

O

O H

O

OH

CO

2

M e

C

7

H

1 5

O

Bry ol o g F

K

i

= 8 .3 nM

B ryo lo g E

K

i

= 4 7 n M

Wender, P. A.; Hinkle, K. W.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B. Med. Res. Rev. 1999, 19, 388.

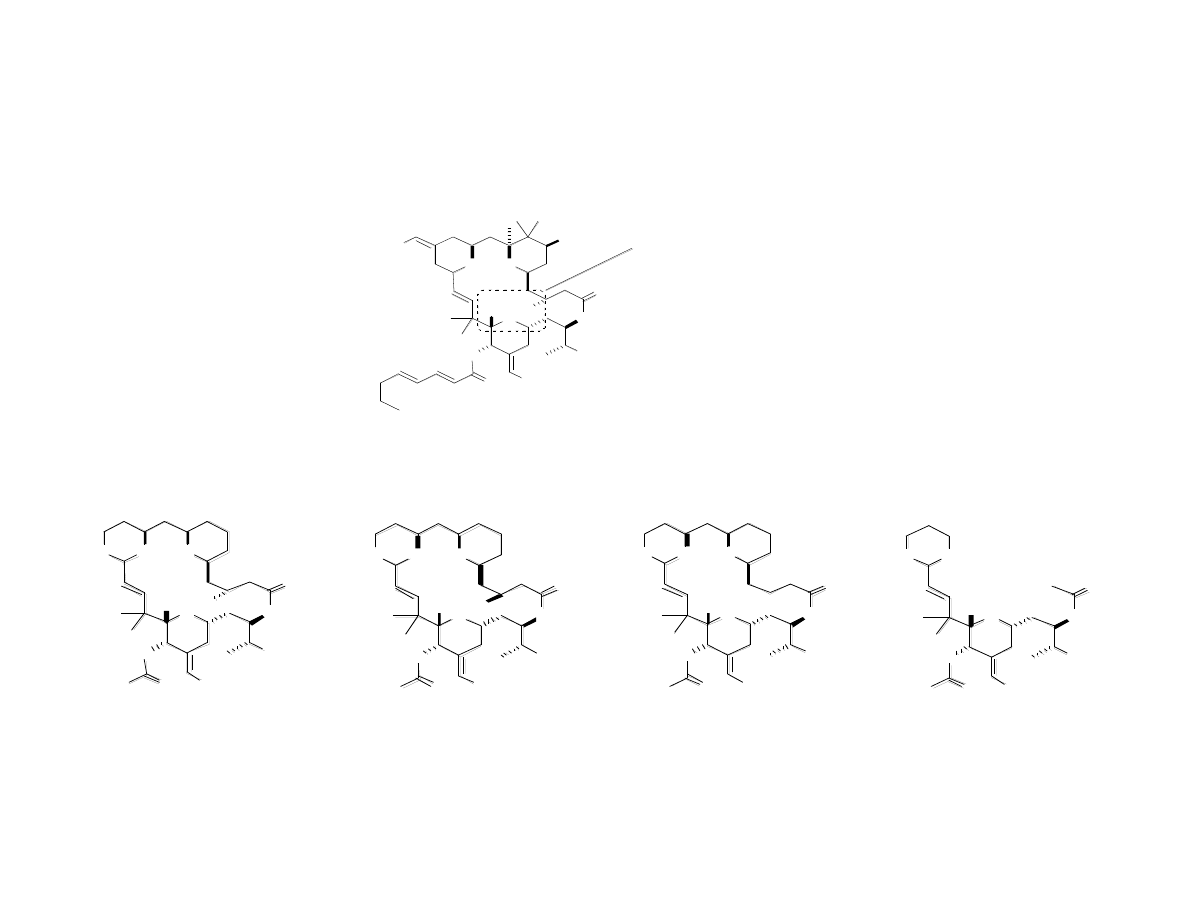

Role of C3 Hydroxyl

O

O

HO

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

CO

2

Me

O

MeO

2

C

HO

OAc

Hydrogen bonding

stabilizing a conformation?

O

O

O

O

O

OR

O

OH

CO

2

M e

C

7

H

1 5

O

O

O

O

H O

O

O

O

OR

O

O H

C O

2

M e

C

7

H

15

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

OR

O

O H

C O

2

M e

C

7

H

15

O

O

O

O

HO

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

1 5

O

Br yo lo g A

K

i

= 3.4 nM

Br yo lo g C

K

i

= 28 5 nM

B ryo lo g D

K

i

= 2 97 n M

K

i

> 10 ,0 00 n M

Wender, P. A.; Hinkle, K. W.; Koehler, M. F. T.; Lippa, B. Med. Res. Rev. 1999, 19, 388.

Fine-Tuning the Structure: Second

Generation Sythesis of C Ring

O

O

HO

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

CO

2

Me

O

MeO

2

C

HO

OAc

Are the methyl group

and the C26 stereocenter

needed for activity?

Fine-Tuning the Structure: Second

Generation Sythesis of C Ring

H O

OH

1 ) N aH , TBS C l

2 ) SO

3

- py r., T EA, D M SO

3 ) M gC l CH

2

C H

2

C H

2

OMg C l

4 ) Sw e rn

5 4 %

3 k g = $ 34 .8 0

TB SO

O

O

1 ) R -BIN OL , 4 A . M S, a ll ylS n Bu

3

T i(Oi Pr )

4

, B (OM e)

3

7 7%

2 ) ca t pTS A, 4 A . MS , P h Me 8 5 %

3 ) MM PP , Na H C O

3

M e OH /CH

2

C l

2

78 % , dr =4 :1

O

H O

OM e

T BSO

H

C O

3

-

C O

2

H

2

M g

2 +

M MP P

1 ) TP AP, N MO 7 8%

2 ) K

2

C O

3

, C HOC O

2

M e

Me OH 7 2%

O

O

OMe

TB SO

H

CO

2

M e

O

O

OM e

TBSO

H

C O

2

Me

1) L u ch e r ed u ctio n

2) C

7

H

1 5

C O

2

H , DIC , D MA P

93 %

O

C

7

H

1 5

1 ) 3 H F-TE A

2 ) D M P, N aH C O

3

8 7 %

O

O

OM e

O

H

CO

2

M e

O

C

7

H

1 5

t- Bu L i, Me

2

Zn ;

th e n 1 M HC l

90 %

O

O

OMe H

C O

2

M e

O

C

7

H

1 5

1 ) (D H QD )

2

PYR , K

2

Os O

2

(OH )

4

,

K

3

Fe( C N)

6

, K

2

C O

3

dr=2 .5 :1

2 ) p TSA

3 ) TBS C l, im id .

4 6%

Br

OE t

O

O

O

OH

H

C O

2

Me

O

C

7

H

1 5

O

OTBS

OH

Wender, P. A.; Baryza, J. L.; Bennett, C. E.; Bi, F. C.;. Brenner, S. E.; Clarke, M. O.; Horan, J. C.; Kan, C.; Lacôte, E.;

Lippa, B.; Nell, P. G.; Turner, T. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13648.

Completion of Bryolog G

O

O

O

O H

O

TBS O

O

OTB S

O

O H

OH

C O

2

M e

C

7

H

15

O

C H O

Y a ma g uc hi 8 7 %

O

O

O

TB SO

O

O

O

OTBS

O

OH

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

1 5

O

C HO

O

O

O

H O

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

C O

2

Me

C

7

H

15

O

H F-p yr

82 %

Bry ol o g G

K

i

= 0 .2 5 nM

Wender, P. A.; Baryza, J. L.; Bennett, C. E.; Bi, F. C.;. Brenner, S. E.; Clarke, M. O.; Horan, J. C.; Kan, C.; Lacôte, E.;

Lippa, B.; Nell, P. G.; Turner, T. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13648.

Comparison of Bryolog G to

Bryostatin 1

O

O

O

HO

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

CO

2

Me

O

Bryolog G

K

i

= 0.25 nM

O

O

HO

O

O

O

OH

O

OH

CO

2

Me

O

MeO

2

C

HO

OAc

Bryostatin 1

K

i

= 1.35 nM

•Over 60 steps in previous syntheses

of bryostatins

•In phase I and II clinical trials

•Cost (per previous synthesis): $2.3 million / g

•32 steps (longest linear = 20)

•As effective or more effective than byrostatin 1

as an anti-cancer agent in most cases

•Cost: $1400 / g

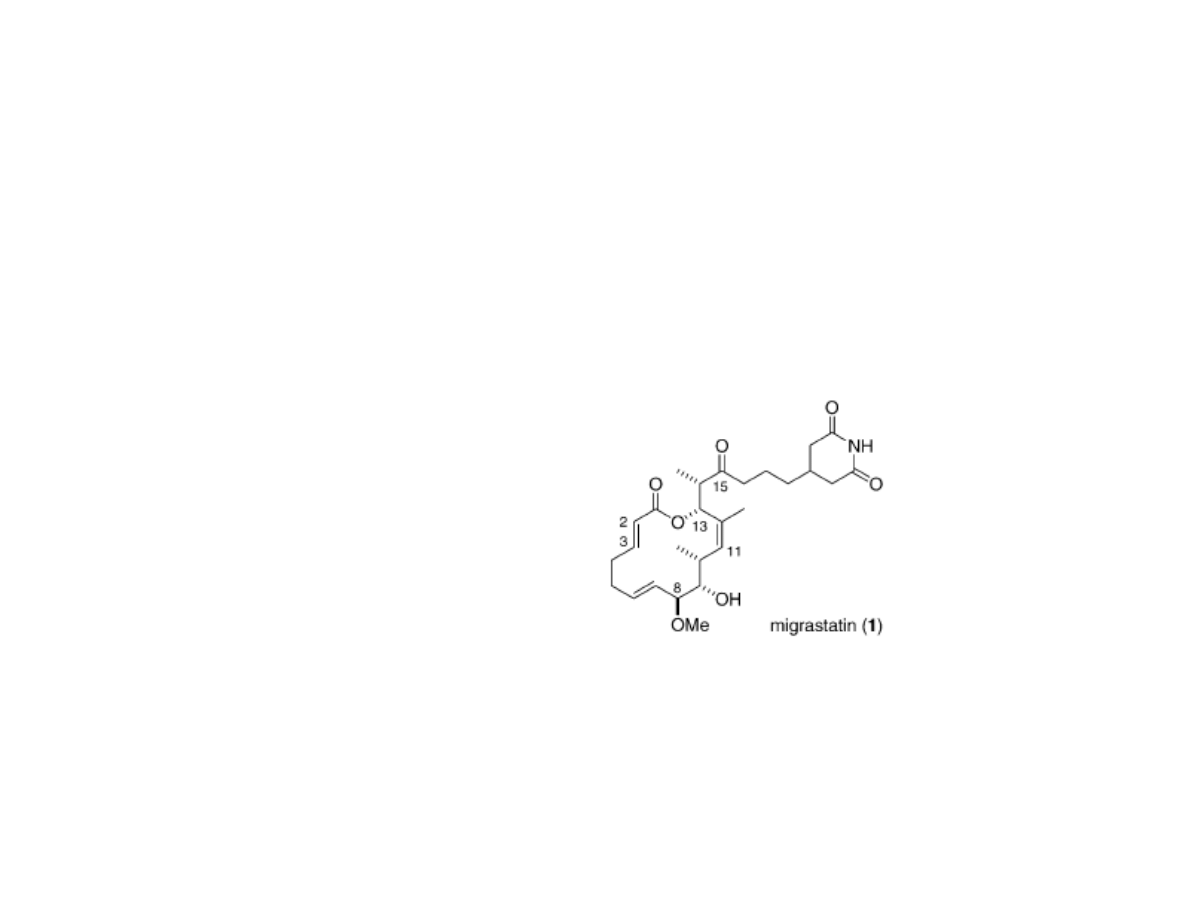

Migrastatin and Cell Migration

•Anti-cancer agents mode of action is typically cell death

•An alternative cancer therapy could rely on inhibition of cell migration

•Cell migration is observed in a number of normal physiological processes

(ovulation, wound healing, inflammation, embryonic development)

•Cell migration also observed in tumor angiogenesis, cancer

cell invasion, and metastasis

•Migrastatin was isolated by Imoto and Kosan bioscience researchers in 2000

from Streptomyces bacteria

•Migrastatin has an IC

50

of 29 µM in wound healing assays

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang, X.-Y.;

Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

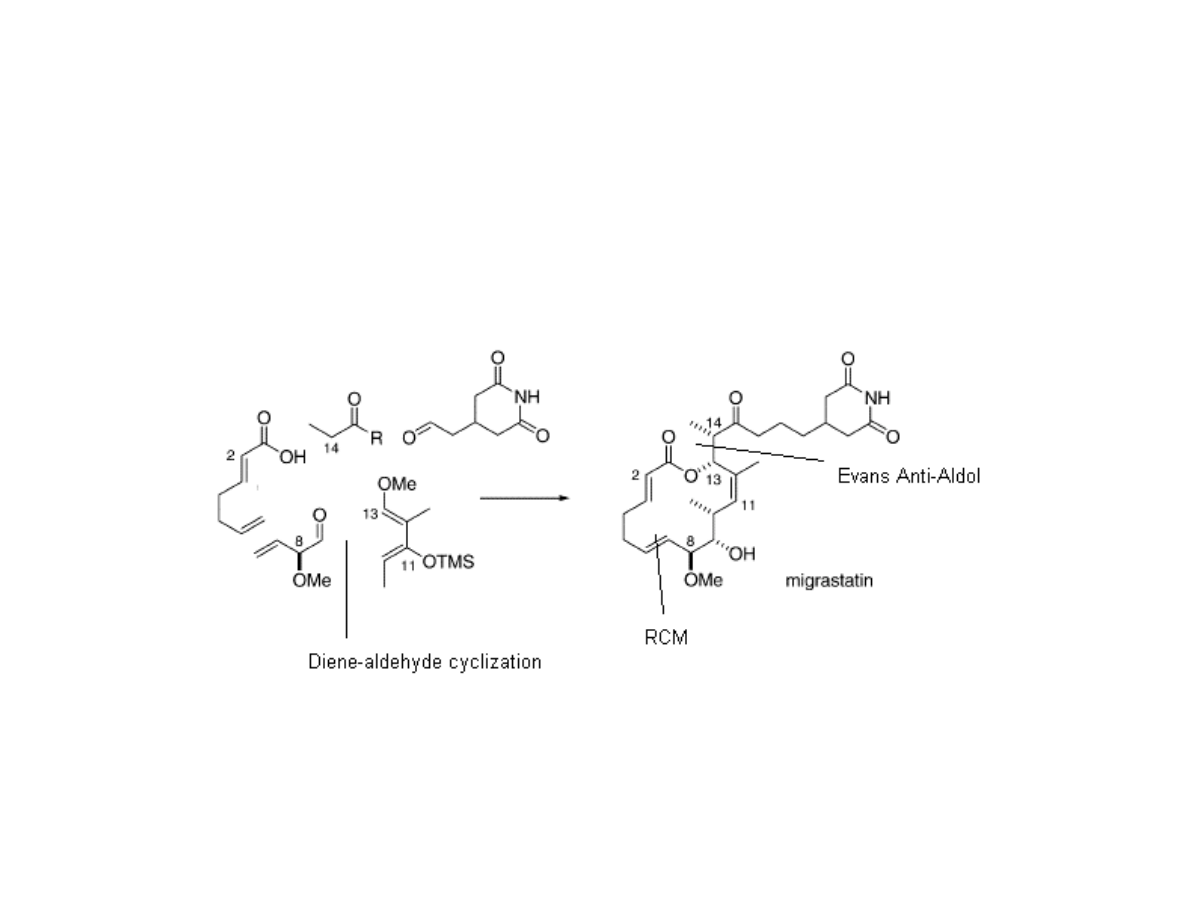

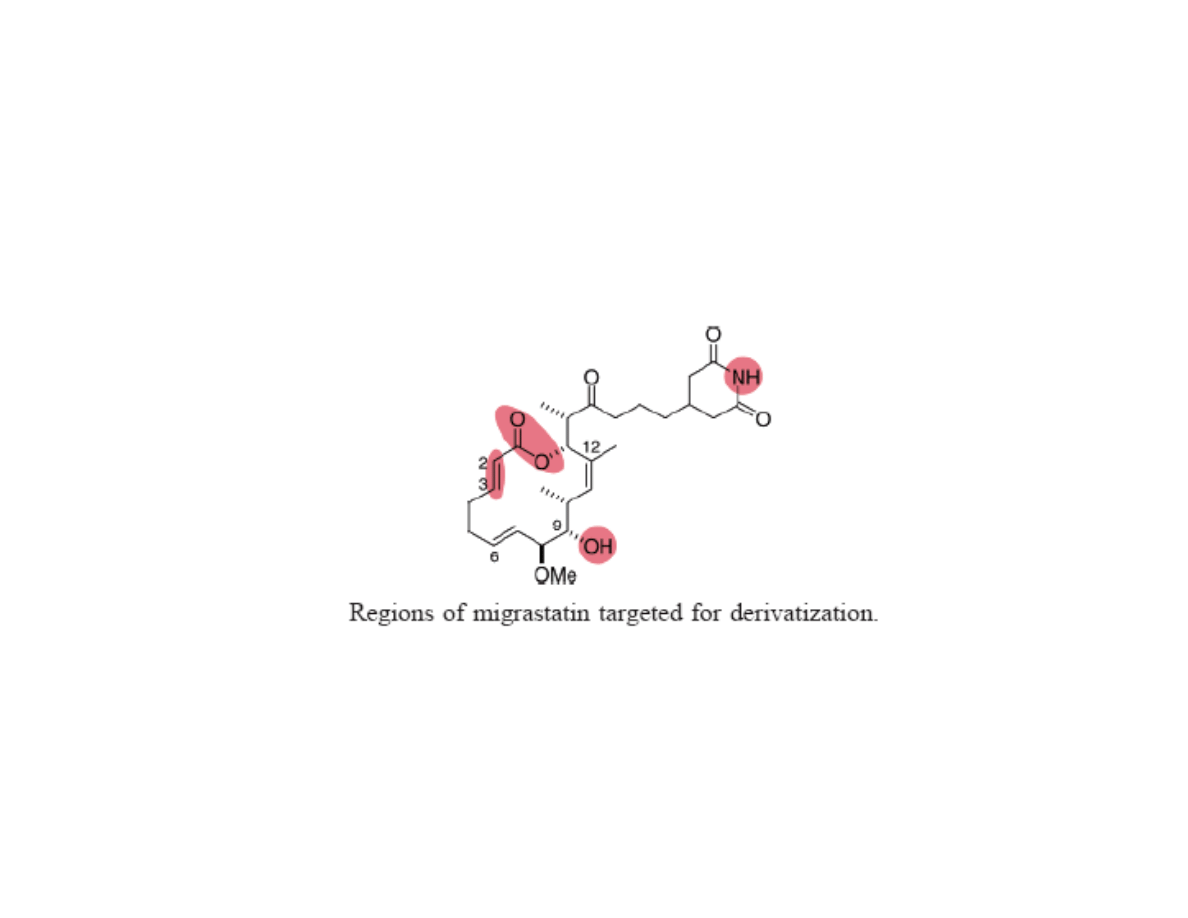

Retrosynthetic Analysis of

Migrastatin

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

M eO

M eO

O

O

O

O

1 ) D IBAL -H , th en

ZnC l

2

, H

2

C CH M gB r 7 5 % , dr >9 :1

2 ) M eI, N aH ; the n

2M H Cl , Me OH 8 0 %

OMe

OMe

OH

OH

Pb (OA c)

4

Na

2

C O

3

OMe

O

1) T iC l

4

, -7 8 d e g. C ;

the n T FA, rt 8 7% (3 ste ps )

2) L i BH

4

3) C S A, H

2

O

4) L i BH

4

5 3% (3 ste p s)

Me O

OTM S

H O

OMe

OH

TB SOTf, 2 ,6-l u t.;

th en H OAc , H

2

O, TH F

8 0 %

H O

OM e

OTBS

Synthesis of C7 to C13 Fragment

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang, X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.;

Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

Jorgensen, M.; Iversen, E. H.; Paulsen, A. L.; Madsen, R. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 4630.

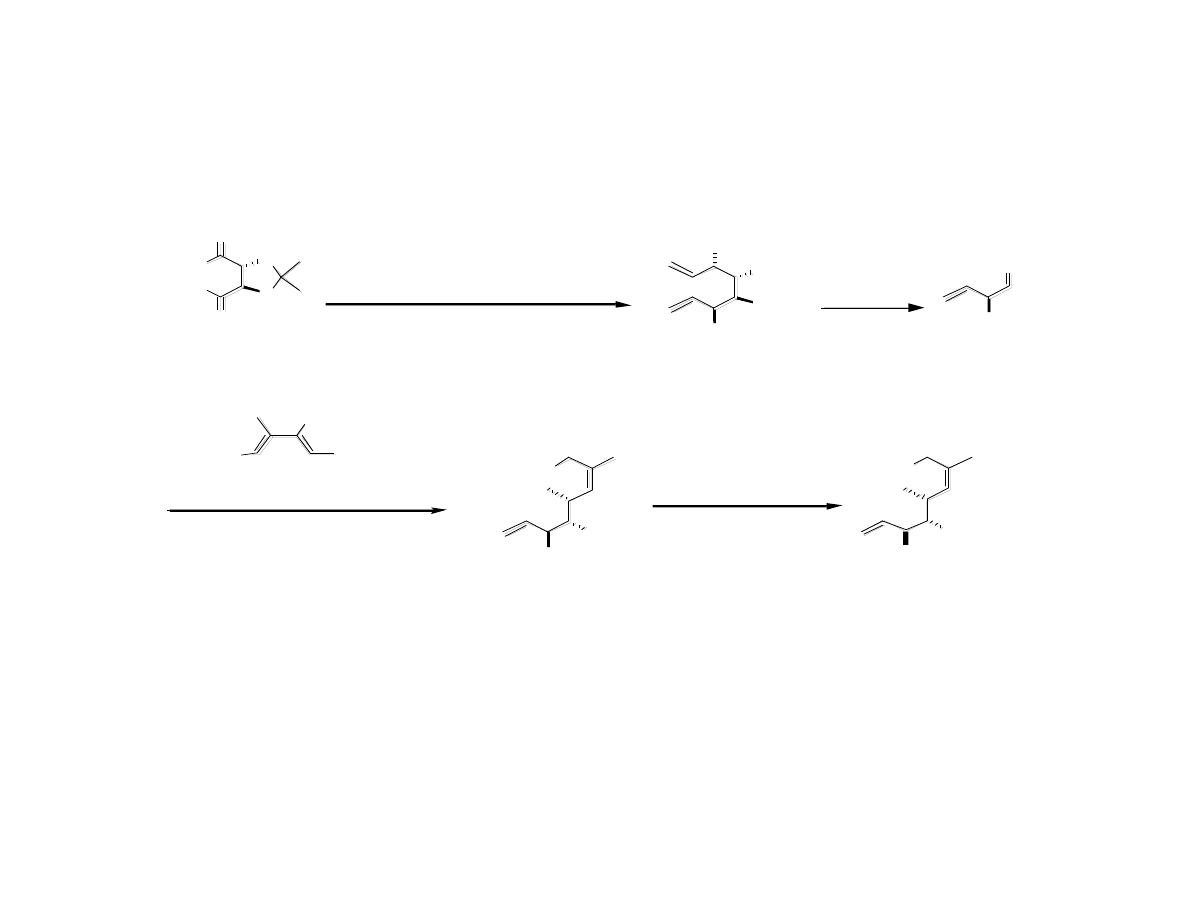

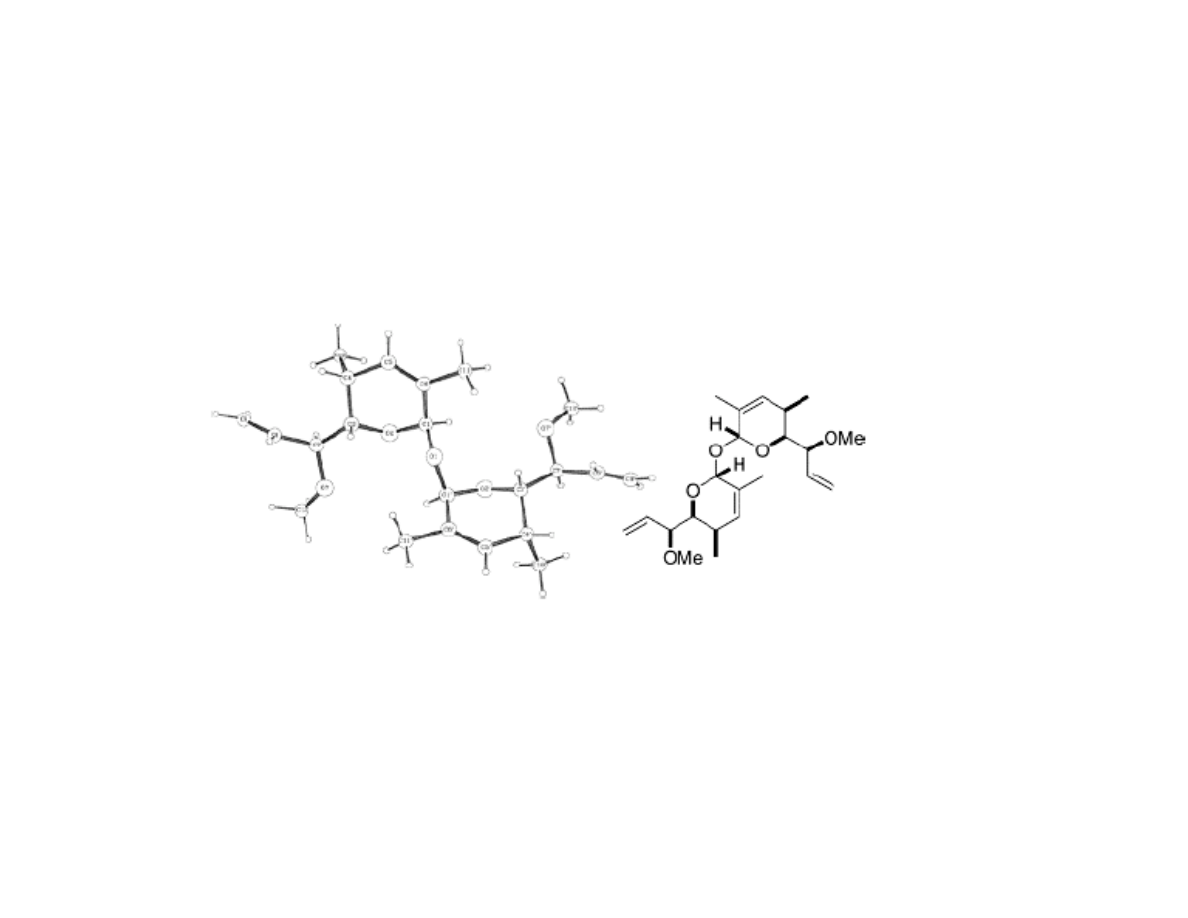

Serendipitous Biproduct

•15% yield of this dimer biproduct obtained during Ferrier rearrangement

when run at 0.3 M (scale-up conditions), though not significantly

observed at 0.1 M (small scale conditions)

•On the bright side, biproduct is crystalline

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

Attaching the Glutarimide Group

H O

OM e

O TBS

1) D M P

2) M g C l

2

TE A, TMS C l;

th en TFA , M e OH

67 %

N

O

O

Bn

O

H O

OM e

O TBS

X c

O

1) T ESC l , i mi d .

2) L i BH

4

83 %

OM e

OTB S

OH

TE SO

OM e

O TBS

TES O

1 ) D MP ; th e n

Li C H

2

P (O)(O Me )

2

;

th e n D M P

2 ) L iC l, D BU , Me C N

5 7 %

NH

O

O

O

O

NH

O

O

Stry ke r Rg t; the n

HO Ac, H

2

O, THF

82 %

H O

OM e

O TBS

O

N H

O

O

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

Completion of Migrastatin

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

H O

OM e

OTBS

O

NH

O

O

Ya m ag u ch i (u si ng p yr.

in ste a d o f DM AP )

67 %

OH

O

O

O

N H

O

O

O

OTB S

OMe

G2 (2 0% ), 0 .5 m M

Ph Me , re flu x

69 %

O

O

N H

O

O

O

OT BS

OM e

H F-p y r.

8 5 %

O

O

N H

O

O

O

OH

OM e

m igra s ta tin

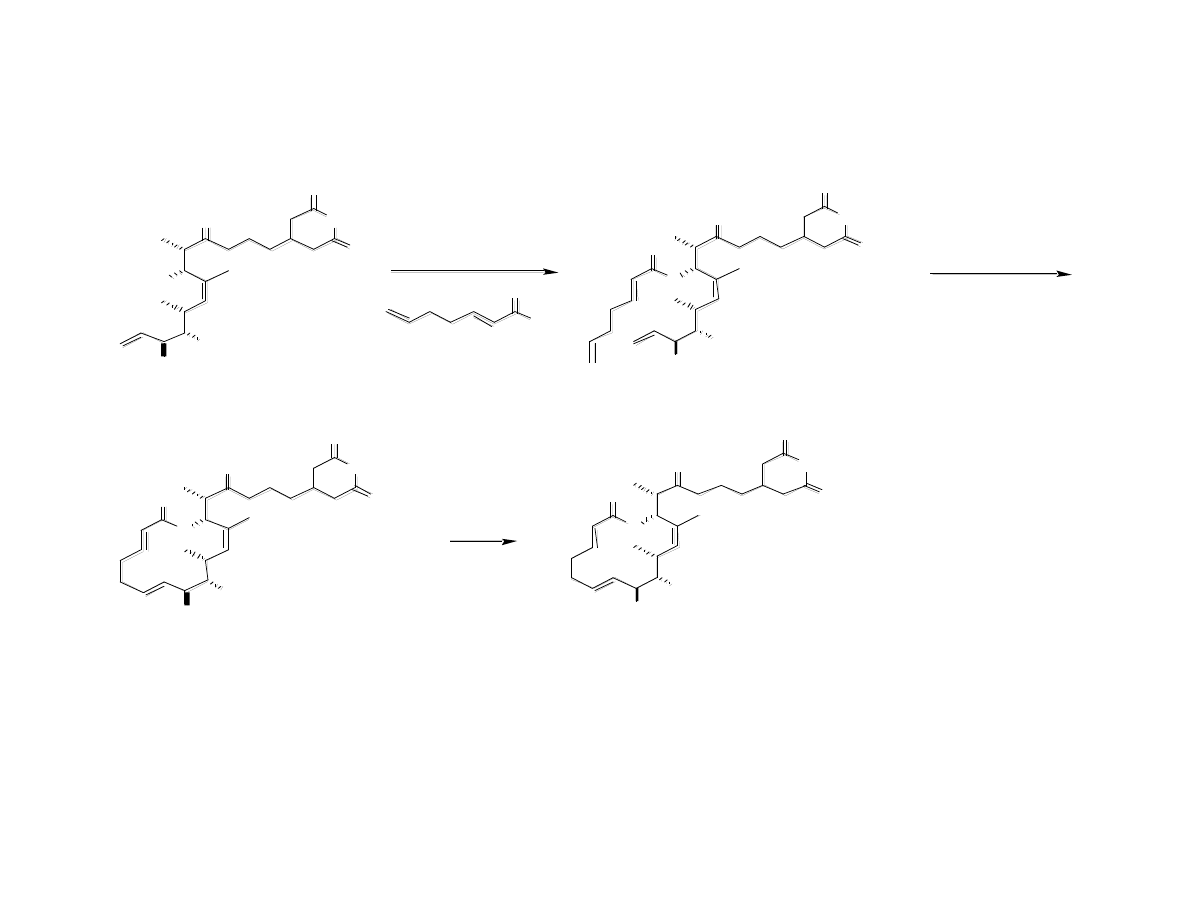

Derivitization of Migrastatin through

Diverted Total Synthesis

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

Synthesis/Evaluation (Cell Migration

Assay) of Migralogs A and B

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

O

O

NH

O

O

O

OTB S

O Me

H F-p yr.

8 1%

M eI, C s

2

C O

3

a ce to ne

85 %

O

O

NH

O

O

O

OH

O Me

O

O

N Me

O

O

O

O H

OM e

O

O

NH

O

O

O

OH

O Me

mi gr as ta ti n

IC

5 0

= 2 9 µM

Sta bl e i n m o us e

b l oo d pl as ma

X

S tr yke r R g t

M ig ra lo g A

IC

5 0

= 1 0 µM

Sta b le in mo u se

b lo od p la sm a

M i gra l og B

IC

5 0

= 7 µM

S tab l e i n m ou se

b l oo d p l as ma

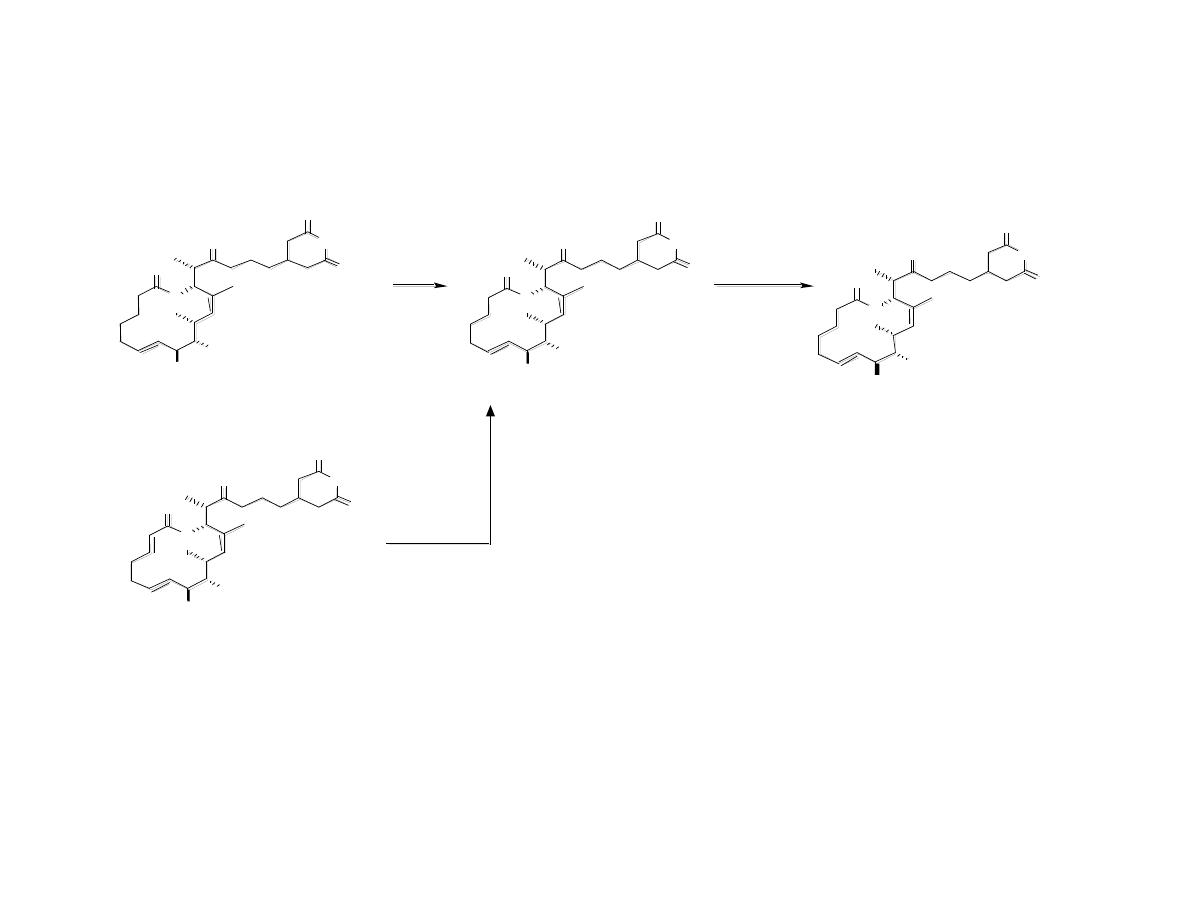

Simplified Migralogs C and D

Have Improved Activity…

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

HO

Me

OTBS

Cl

O

1) DMAP

82%

2) G2 (20%), 0.5 mM

PhMe, reflux 76%

3) HF-pyr. 94%

1) Yamaguchi (using pyr.

instead of DMAP)

48%

2) G2 (20%), 0.5 mM

PhMe, reflux 55%

3) HF-pyr. 66%

OH

O

O

O

OH

OMe

Migralog C

IC

50

= 0.022 µM

Migralog D

IC

50

= 0.024 µM

O

O

OH

OMe

…But Are Quickly Hydrolyzed In Vivo

H O

Me

OTBS

C l

O

1 ) D MA P

8 2%

2 ) G2 (2 0% ), 0 .5 m M

Ph Me , re fl u x 7 6%

3 ) H F-p yr. 9 4 %

1 ) Ya m ag u ch i (u si ng p yr.

i n stea d of D M AP)

4 8 %

2 ) G2 (2 0% ), 0 .5 m M

Ph Me , re flu x 5 5 %

3 ) H F-p yr. 6 6 %

OH

O

O

O

OH

O Me

Mi gr al og C

IC

5 0

= 0 .0 22 µM

Mi gr al og D

IC

5 0

= 0 .0 24 µM

O

O

OH

OM e

20 mi n . i nc ub a tio n

in mo u se b l oo d pl as ma

5 m in . in cu ba tio n

in mo u se b l oo d pl as ma

O H

O

O H

OMe

M ig ra lo g E

IC

50

n ot re p or ted

M ig ra lo g F

IC

50

= 0.3 7 8 µM

O H

O

OH

OM e

OH

OH

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

Stabilizing the Cyclic Core

H O

Me

O TBS

O

1 ) C Br

4

, P h

3

P ( so lid su p p.)

2 ) D BU

the n N a/H g ,

N a

2

H PO

4

, M eO H 6 1 %

N

O

OTBS

OM e

Mi g ra lo g G

IC

50

= 0.2 5 5 µM

Sta b le in mo u se

bl o od p la sm a

O

OT BS

OMe

1 ) (Ph O)

2

P (O)N

3

D B U, P hM e 8 7%

2 ) Ph

3

P, H

2

O ; th e n E DC ,

DIE A, 6 -h ep te no ic ac id 9 2 %

1 ) G2 (2 0 % ), 0.5 mM

Ph M e, re flu x 8 1 %

2 ) H F-p yr . 9 0 %

SO

2

P h

1 ) G2 (2 0 %) , 0 .5 mM

Ph M e, re flu x 6 0 %

2 ) H F-p yr . 81 %

N

O

OH

OMe

O

OH

OMe

M ig ra lo g H

IC

5 0

= 0 .1 00 µM

S tab l e i n m ou se

b lo o d p l as ma

Gaul, C.; Njardarson, J. T.; Shan, D.; Dorn, D. C.; Wu, K.-D.; Tong, W. P.; Huang,

X.-Y.; Moore, M. A. S.; Danishefsky, S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11326.

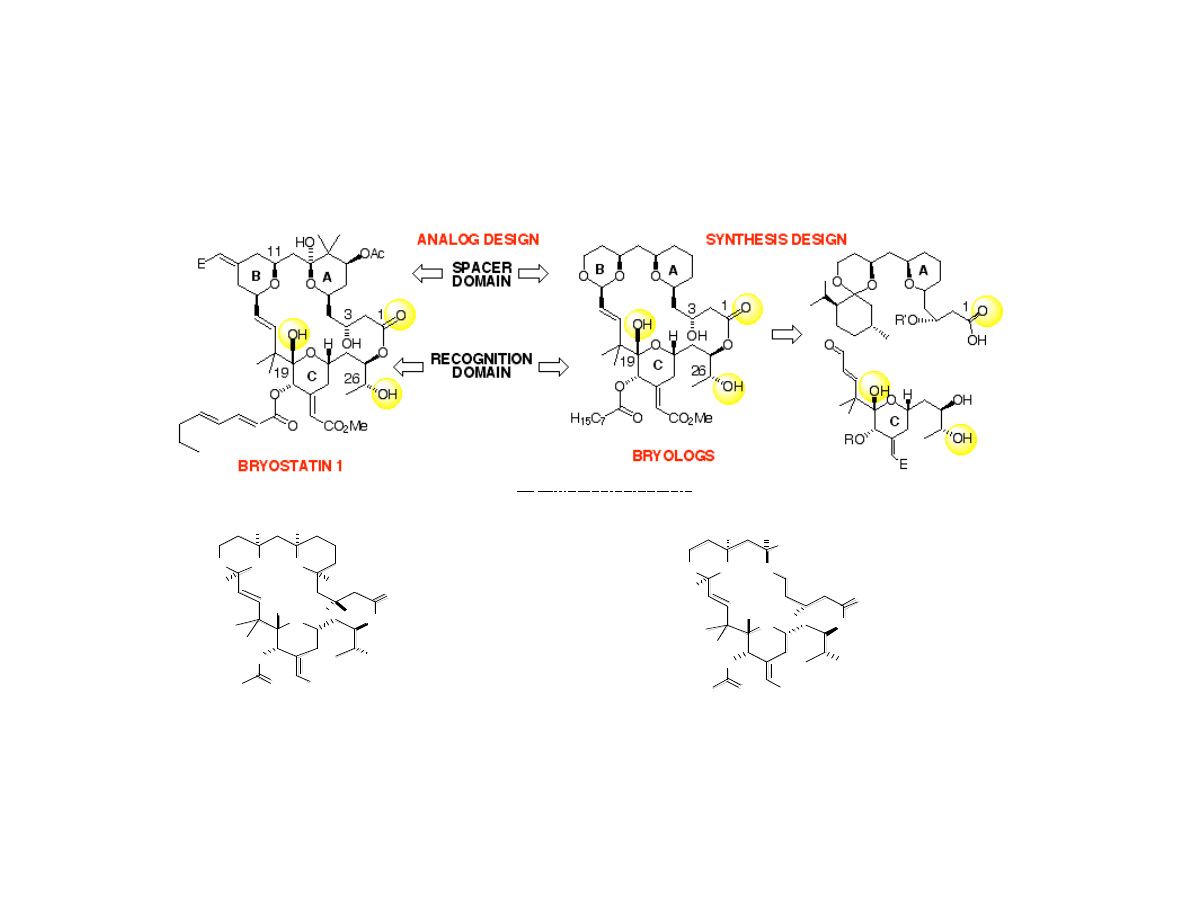

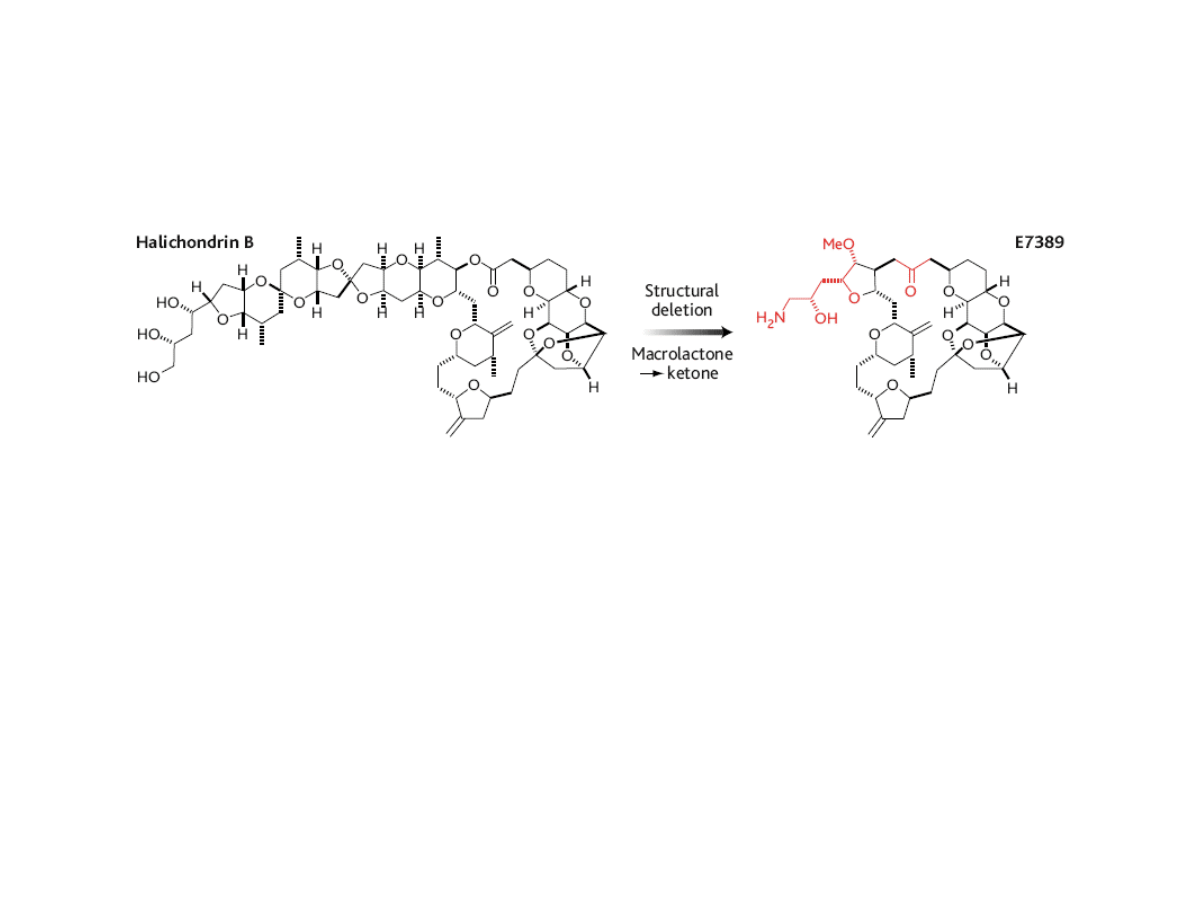

Additional Reading:

Halichondrin B and E7389

Aicher, T. D.; Buszek, K. R.; Fang, F. G.; Forsyth, C. J.; Jung, S. H.; Kishi, Y.; Matelich, M. C.;

Scola, P. M.; Spero, D. M.; Yoon, S. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 3163.

Zheng, W. J.; Seletsky, B. M.; Palme, M. H.; Lydon, P .J.; Singer, L .A.; Chase, C. E.; Lemelin, C.

A.; Shen, Y. C.; Davis, H.; Tremblay, L.; Towle, M. J.; Salvato, K. A.; Wels, B. F.; Aalfs, K. K.;

Kishi ,Y.; Littlefield, B. A.; Yu, M. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 5551.

Paterson, I.; Anderson, E. Science 2005, 310, 451.

•Halichondrin B is a highly cytotoxic (antimitotic) marine natural product.

Total synthesis: Kishi, 1992

• Recent diverted total synthesis has led to simplified analog E7389 with

similar antimitotic activity. Also, replacement of lactone with ketone

has made E7389 more robust in vivo

•E7389 currently in phase I clinical trials

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

2002 3 MAY Lasers in Medicine and Surgery

In vivo MR spectroscopy in diagnosis and research of

Introduction to multivariate calibration in analytical chemistry

Ethics in Global Internet Research

Our World In Medicine

2002 3 MAY Lasers in Medicine and Surgery

In vivo MR spectroscopy in diagnosis and research of

Titanium in medicine

Total synthesis of batrachotoxinin A

Current Clinical Strategies, History and Physical Exam in Medicine (2005) 10Ed; BM OCR 7 0 2 5

Reedy&Reedy Statistical Analysis in Art Conservation Research

optimization in organic chemistry

Total syntheses of ( ) terpestacin

Open Problems in Computer Virus Research

Instruments used in medicine

the silence in medicine

więcej podobnych podstron