Original article

doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu408

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of

venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and

meta-analysis

Patompong Ungprasert

1

, Narat Srivali

1

, Karn Wijarnpreecha

2,3

,

Prangthip Charoenpong

4

and Eric L. Knight

1

Abstract

Objective. The aim of this study was to integrate and examine the association between NSAID use and

venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Methods. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies that reported odds ratios,

relative risks, hazard ratios or standardized incidence ratios for VTE among NSAID users compared

with non-users. Pooled risk ratios and 95% CIs were calculated using a random effects generic inverse

variance model.

Results. Six studies with 21 401 VTE events were identified and included in the data analysis. The pooled

risk ratio of VTE in NSAID users was 1.80 (95% CI 1.28, 2.52).

Conclusion. Our study demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of VTE among NSAID users.

This finding has important public health implications given the prevalence of NSAID use in the general

population.

Key words: systematic review, epidemiology, meta-analysis, NSAIDs, respiratory.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep

venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE),

is a common illness with a reported annual incidence of

12 new cases per 1000 population [

]. Recognition of

its risk factors and appropriate preventive interventions

for this condition are crucial, as morbidity and mortality

from PE are high, with a reported 30-day case fatality

rate as high as 810% [

]. Several medical conditions,

including immobilization, surgery, pregnancy and cancer,

are recognized as risk factors for VTE.

NSAIDs, one of the most commonly used medications

around the world [

], are well known for their potential

adverse effects. For example, in the recent past, rofecoxib

was withdrawn from the market after a randomized pla-

cebo-controlled trial found an increased incidence of

myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death among

rofecoxib users [

]. A subsequent meta-analysis con-

firmed this finding and also found an increased incidence

among other non-specific cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor

users [

]. Since arterial and venous thrombosis share sev-

eral pathophysiological mechanisms [

], NSAIDs might

increase the risk of VTE. However, the epidemiological

data on VTE risk among NSAID users is limited and con-

flicting. Thus, to further investigate this association, we

conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of ob-

servational studies that compared the risk of VTE in

NSAID users vs non-users. We did not include rando-

mized controlled trials in this meta-analysis because

VTE is a less common adverse effect that generally re-

quires a larger sample size and a longer duration of

follow-up.

1

Department of Internal Medicine, Bassett Medical Center and

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons,

Cooperstown, NY, USA,

2

Cardiac Electrophysiology Unit, Department

of Physiology,

3

Cardiac Electrophysiology Research and Training

Center, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai,

Thailand and

4

Department of Internal Medicine, Advocate Illinois

Masonic Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA.

Correspondence to: Patompong Ungprasert, Department of Internal

Medicine, Bassett Medical Center and Columbia University College of

Physicians and Surgeons, 1 Atwell Road, Cooperstown 13326,

NY, USA. E-mail: p.ungprasert@gmail.com

Submitted 13 May 2014; revised version accepted 16 August 2014.

!

The Author 2014. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Society for Rheumatology. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

1

RHEUMATOLOGY

53

MET

A

-

ANALYSIS

Rheumatology Advance Access published September 24, 2014

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Two investigators (P.U. and N.S.) independently searched

published studies indexed in Medline, Embase and the

Cochrane database from inception to December 2013.

The search terms were compiled from the names of indi-

vidual drugs, the therapeutic class and the mode of action

in conjunction with the terms pulmonary embolism, deep

venous thrombosis and venous thromboembolism. The

detailed search strategy is provided as

, available at Rheumatology Online. A manual

search of the references of selected retrieved studies

was also performed. Abstract and unpublished studies

were not included.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) casecontrol or

cohort studies published as original studies to evaluate

the association between use of NSAIDs and risk of VTE;

(ii) odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RRs), hazard ratios

(HRs) or standardized incidence ratios with 95% CIs

were provided and (iii) random participants without VTE

were used as the reference group for casecontrol studies

and participants who did not use NSAIDs were used

as the reference group for cohort studies. Study eligibility

was independently determined by each investigator noted

above. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The quality of the included studies was independently

evaluated by each investigator using the Newcastle

Ottawa quality assessment scale [

].

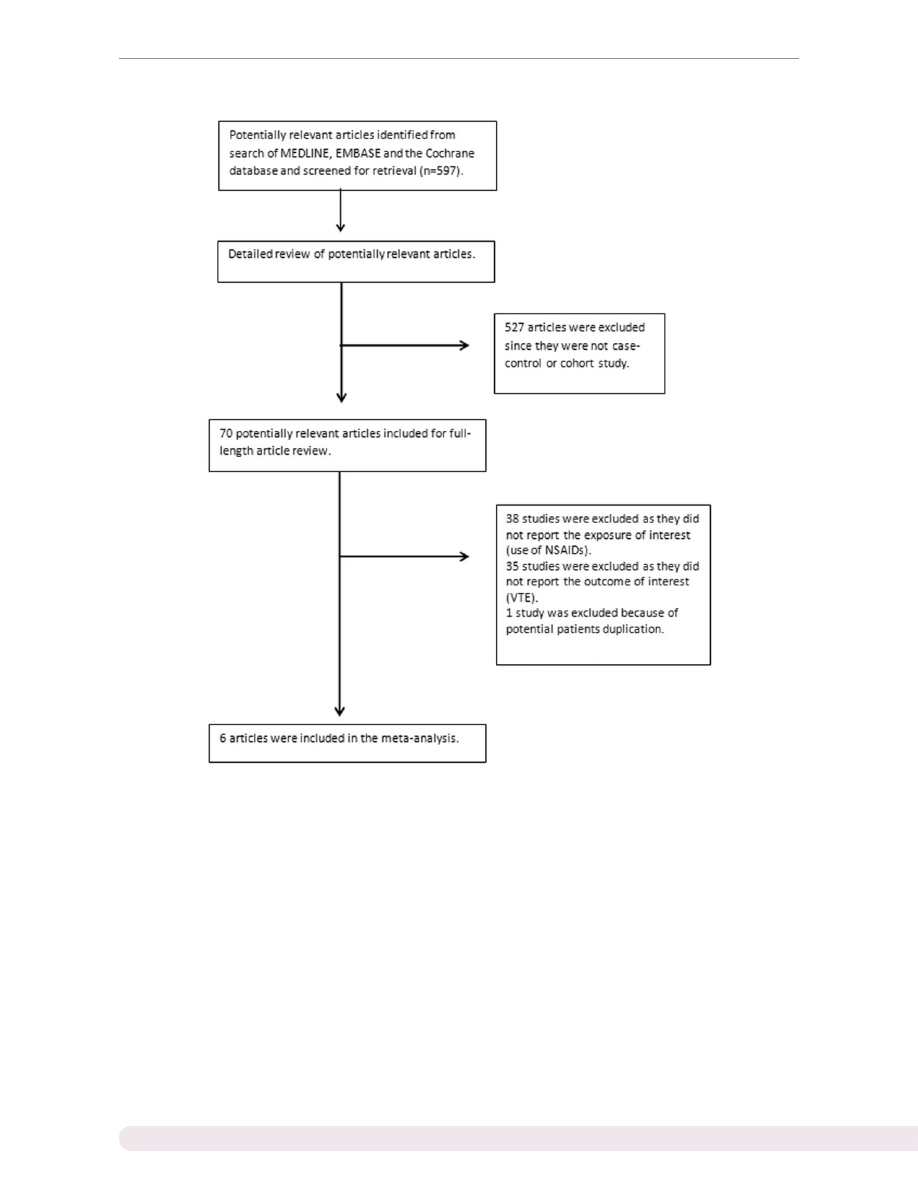

Our search strategy yielded 597 potentially relevant

articles. Five hundred and twenty-seven articles were

excluded because they were not casecontrol or cohort

studies. Seventy articles underwent full-length article

review. Thirty-eight of these were excluded because

they did not report the exposure of interest (use of

NSAIDs), 35 were excluded because they did not report

the outcome of interest (VTE) and 1 was excluded be-

cause it used the same database as was used by another

study. Six studies (one cohort study and five casecontrol

studies) with 21 401 VTE events met our eligibility criteria

and were included in the analysis [

].

outlines

our search methodology and selection process. The de-

tailed characteristics and quality assessment of these six

studies are described in

and

.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract

the following information: last name of the first author, title

of the article, year of publication, country where the study

was conducted, study size, study population, definition of

NSAID exposure, verification of NSAID use, verification of

VTE, confounder assessed and adjusted effect estimates

with 95% CIs. The two investigators independently per-

formed this data extraction.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.2 software (Cochrane Collaboration,

Oxford, UK) was used for the data analysis. We reported

the pooled effect estimate of VTE using the combination

of data from casecontrol and cohort analyses to increase

the precision of our estimates. We used the ORs of

casecontrol studies as an estimate of the RRs to pool

these data with the RR of the cohort study, as the out-

come of interest was relatively uncommon [

]. If the

cohort study provided a HR, the HR was used as an es-

timate of the RR. Adjusted point estimates and standard

errors were extracted from individual studies and were

combined by the generic inverse variance method of

DerSimonian and Laird [

]. Given the high likelihood of

between-study variance with the different study designs,

definitions of NSAID use and populations, we used a

random effects model rather than a fixed effects model.

All of the studies reported the VTE risk of all NSAID (non-

selective and selective COX-2 inhibitors) use while three

studies also provided data on the VTE risk of selective

COX-2 inhibitors [

]. Pooled RRs were calculated

for all NSAIDs and for selective COX-2 inhibitors.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s

Q test. This statistic was complemented with the I

2

stat-

istic, which quantifies the proportion of total variation

across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than

chance. A value of I

2

of 025% represents insignificant

heterogeneity, 2550% low heterogeneity, 5075% mod-

erate heterogeneity and 75100% high heterogeneity [

].

This study was exempted from ethical approval by the

institutional review board of the Bassett Medical Center,

Cooperstown, NY, USA.

Results

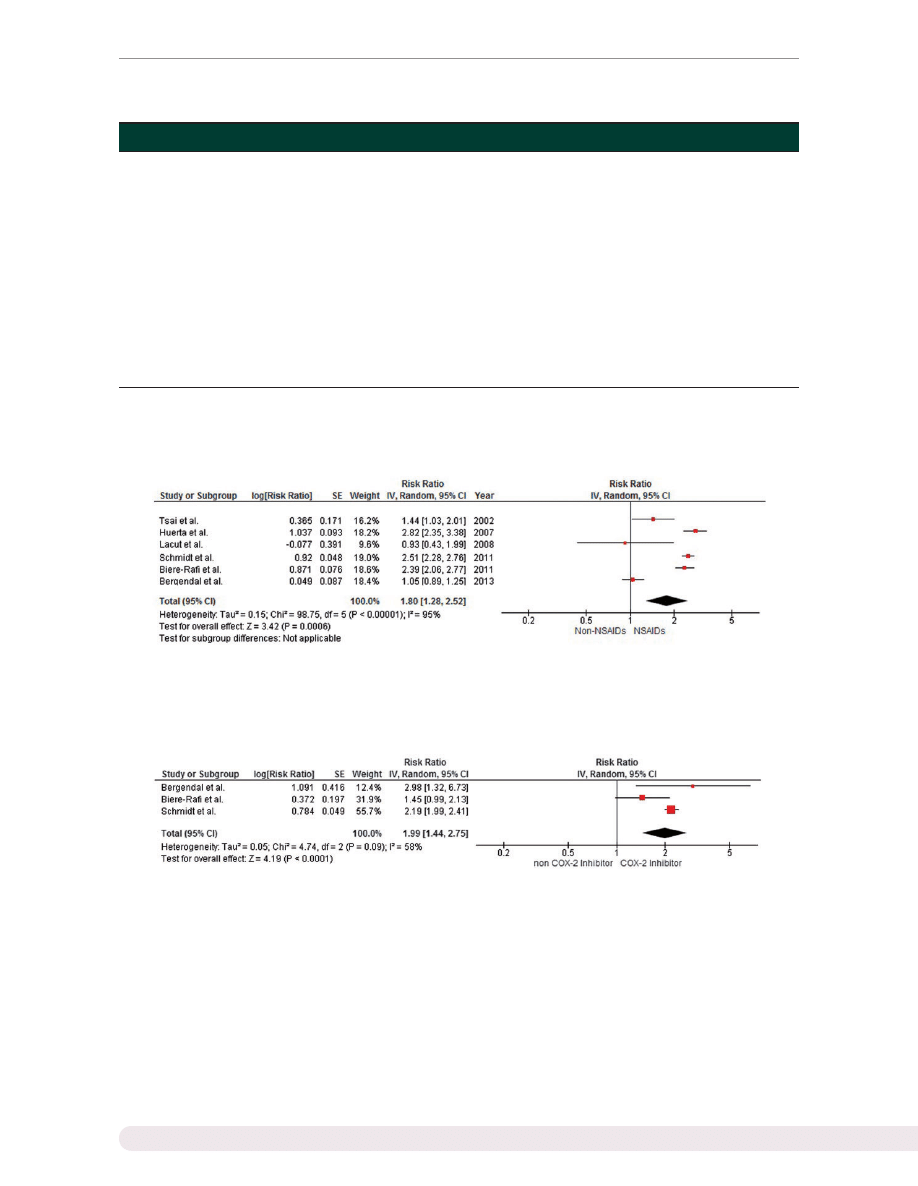

Our meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically signifi-

cantly increased VTE risk among subjects who used

NSAIDs with a pooled risk ratio of 1.80 (95% CI 1.28,

2.52). The statistical heterogeneity was high, with an I

2

of 95%. Three studies reported a risk ratio for participants

who used selective COX-2 inhibitors. The VTE risk among

selective COX-2 inhibitor users was also significantly ele-

vated, with a pooled risk ratio of 1.99 (95% CI 1.442.75).

and

present the forest plots of our findings.

Sensitivity analysis

With the concern over high heterogeneity, we performed

jackknife sensitivity analysis by excluding one study at a

time. The results of this sensitivity analysis suggested that

our results were robust, as the pooled risk ratios remained

significantly elevated, ranging from 1.62 to 2.21, while the

corresponding 95% CI bounds remained >1.

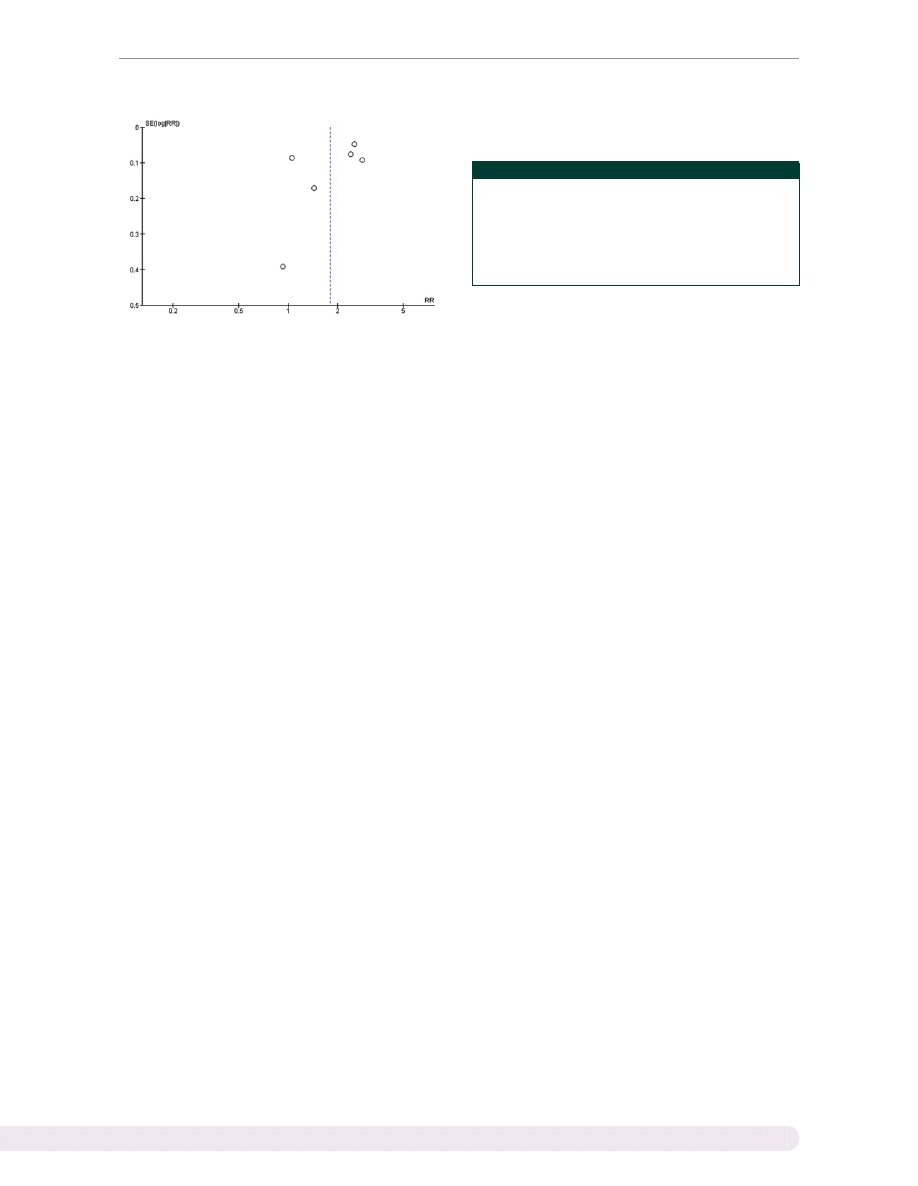

Publication bias

Funnel plots to evaluate publication bias are shown in

. The graph is asymmetric, suggesting that publica-

tion bias in favour of positive studies may be present.

2

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Patompong Ungprasert et al.

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of

published observational studies assessing the risk of

VTE among NSAID users. Our study demonstrates a sig-

nificant association between NSAID use and VTE, with an

overall 1.80-fold increased risk compared with subjects

who did not use NSAIDs. VTE risk appears to be even

higher among selective COX-2 inhibitor users, with a

1.99-fold increased risk, although the CI overlaps. The

VTE risk found in this study is slightly higher than the cor-

onary artery thrombosis risk seen in another meta-

analysis (ranging from 0.96 to 1.36) [

]. With the

widespread use of these medicines, this increased risk

may have important public health implications.

Heterogeneity between studies was present in this

meta-analysis. We suspect that differences in study

design, definitions of NSAID exposure and population

were the main source of heterogeneity. Three studies

were done in hospitalized subjects [

] and three

studies included both ambulatory and hospitalized sub-

jects [

,

]. One study included only patients with

PE [

], whereas the rest of the studies included patients

with DVT and/or PE. The definition and method of verifi-

cation for NSAID exposure also varied from study to

study, with some studies using a pharmacology-linked

F

IG

. 1

Identification of studies

VTE: venous thromboembolism.

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

3

NSAIDs and risk of VTE

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

T

ABLE

1

Main

characteristics

of

case

control

studies

included

in

the

meta-analysis

Huerta

et

al.

[1

Lacut

et

al.

[12]

Biere-Rafi

et

al.

[13]

Schmidt

et

al.

[14]

Bergendal

et

al.

[1

]

Country

UK

France

The

Netherlands

Denmark

Sweden

Year

2007

2008

2011

2

011

2013

Cases

Hospitalized

or

non-

hospitalized

patients

who

were

diagnosed

with

DVT

and/or

PE

identified

from

the

G

eneral

Practice

Research

Database,

covering

3

million

p

eople

Patients

who

were

admitted

at

the

Brest

University

Hospital

with

a

d

iagnosis

of

DVT

and/or

PE

Hospitalized

patients

who

were

diagnosed

with

PE

identified

from

the

PHARMO

record

linkage

system,

covering

2

m

illion

people

Hospitalized

or

non-

hospitalized

patients

who

were

diagnosed

with

DVT

and/or

PE

identified

from

the

Danish

National

Patient

Registry

Female

patients

who

were

admitted

at

one

o

f

the

participating

hospitals

with

a

diagnosis

of

DVT

and/or

PE

Case

verification

P

atients

needed

to

receive

anticoagulant

NA

Confirmed

by

CT

or

V/Q

scan

NA

Radiological

evidence

of

VTE

+

patient

n

eeded

to

receive

anticoagulants

Controls

Sex-

and

age-matched

subjects

randomly

selected

from

same

database

Sex-

and

age-matched

hos-

pitalized

patients

ran-

domly

selected

from

the

same

hospital

Sex-,

age-

and

region-

matched

subjects

ran-

domly

selected

from

the

same

database

Sex-

and

age-matched

sub-

jects

randomly

s

elected

from

the

same

database

Sex-

and

age-matched

hospitalized

patients

randomly

selected

from

the

Swedish

population

register

Period

of

inclusion

1994

2000

2000

2004

1990

2006

1999

2006

2003

2009

Age

range,

years

20

79

18

96

18

96

NA

18

64

Female,

%

N

A

58.5

57.0

53.7

100

Cases,

n

6550

402

4433

8

368

1433

Controls,

n

10

000

402

16

802

8

2

2

18

1402

Definition

of

NSAID

exposure

Most

recent

p

rescription

lasted

until

the

index

d

ate

or

ended

in

the

30

days

before

the

index

date

Current

use

of

NSAIDs

at

the

time

o

f

admission

Most

recent

prescription

lasted

until

the

index

date

or

ended

in

the

90

days

before

the

index

date

Most

recent

prescription

lasted

until

the

index

date

or

ended

in

the

60

days

before

the

index

date

Use

of

NSAIDs

during

the

90

days

before

the

index

date

Verification

o

f

NSAIDs

use

Pharmacy

record

from

the

same

database

Structured

interview

and

validation

from

information

provided

by

the

National

Health

Service

of

France

Pharmacy

record

from

the

same

database

Pharmacy

record

from

the

same

database

Structured

phone

interview

Confounder

assessed

Sex,

age,

BMI,

s

moking,

fracture,

surgery,

cancer,

visits

to

the

family

phys-

ician

last

year

None

Hospitalization

Hospitalization,

pregnancy,

fracture,

surgery,

cancer,

diabetes,

CAD,

stroke,

PVD,

diabetes

mellitus,

RA,

COPD,

CHF,

OA,

obesity,

medication,

liver

disease,

renal

failure,

osteoporosis

Age

Quality

assessment

(Newcastle

Ottawa

scale)

Selection:

4

stars;

compar-

ability:

1

star;

exposure:

2

stars

Selection:

2

stars;

compar-

ability:

1

star;

exposure:

2

stars

Selection:

4

stars;

compar-

ability:

2

stars;

exposure:

2

stars

Selection:

3

s

tars;

compar-

ability:

2

star;

exposure:

2

stars

Selection:

3

stars;

com-

parability:

1

star;

expos-

ure:

2

stars

CAD:

coronary

artery

disease;

CHF;

congestive

heart

failure;

COPD:

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease;

DVT;

deep

venous

thrombosis;

NA:

not

ava

ilable;

PE:

pulmonary

embolism;

PHARMO:

PHARMO

Institute,

Utrecht,

The

Netherlands;

PVD:

peripheral

vascular

disease;

V/Q

scan:

ventilation-perfusion

scan;

VTE:

veno

us

thromboembolism.

4

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Patompong Ungprasert et al.

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

database [

,

], while other studies used a struc-

tured or phone interview [

,

]. Controlling for confoun-

ders might also contribute to this heterogeneity, as it was

done differently between studies, from virtually no correc-

tion to control for a large number of confounders. It should

be noted that, from our sensitivity analysis, exclusion of

the study by Bergendal et al. [

], the only study that

exclusively included only female participants, noticeably

decreased the statistical heterogeneity, with a reduction in

I

2

from 95% to 78%.

Why NSAIDs may increase the risk of VTE is unclear.

The pathophysiology of increased arterial thrombosis risk

(and thus coronary artery events) is explained by a

thromboxaneprostacyclin imbalance. Inhibition of the

T

ABLE

2

Main characteristics of the cohort study included in the meta-analysis

Tsai et al. [10]

Country

USA

Study design

Prospective cohort

Year

2002

Cohort

Residents of four US communities. Follow-up included semi-annual

contacts, alternating between phone calls and clinic visits

Definition of NSAID use

NA

Event verification

Duplex US scan or venography or CT angiography or autopsy

Follow-up

From 1987 until death, migration from the system or 31 December 1999

Age, mean, years

59.0

Female, %

55.0

Cohort, n

19 293

Events, n

215

Average follow-up, years

7.8

Confounder assessed

Sex, age, race

Quality assessment (NewcastleOttawa scale)

Selection: 3 stars; comparability: 1 star; outcome: 3 stars

F

IG

. 2

Forest plot of all NSAIDs

IV: inverse variance; SE: standard error.

F

IG

. 3

Forest plot of selective COX-2 inhibitors

COX: cyclooxygenase; IV: inverse variance; SE: standard error.

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

5

NSAIDs and risk of VTE

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

COX-2 enzyme has been shown to inhibit the synthesis of

prostacyclins, potent platelet activation inhibitors, while

stimulating the release of thromboxane, a potent platelet

aggregation facilitator, from the activated platelets. The

activation and aggregation of platelets might, in turn,

induce a coagulation cascade and clotting [

,

,

This mechanism might explain the increased risk of

venous thrombosis we observed in this study. In fact,

the VTE risk of selective COX-2 inhibitors appears to be

higher than overall NSAIDs, although without statistical

significance, as the CI overlaps.

Also, aspirin, a specific and irreversible COX-1 inhibitor,

has proved effective for VTE prevention [

]. This

might provide further evidence that the increased VTE

risk comes primarily from COX-2 inhibition.

Even though the six studies included in this meta-

analysis were of high quality, there are some limitations

and thus our results should be interpreted with caution.

First, we cannot exclude the possibility of publication bias

in favour of positive studies, as the funnel plot is asym-

metric. Second, the statistical heterogeneity in this study

is high and thus the data from individual studies might

be too heterogeneous to combine. Third, most of the

included studies were conducted using a medical regis-

trybased database, raising the possibility of coding

inaccuracy. Fourth, this is a meta-analysis of observa-

tional studies and thus can only demonstrate an associ-

ation, not establish cause and effect, so we cannot be

certain that NSAIDs themselves or other potential con-

founders increase the risk of VTE. For example, patients

may have been prescribed NSAIDs for underlying ill-

nesses causing pain and immobility or for chronic inflam-

matory disorders, which are linked to a higher VTE risk

compared with the general population [

]. We could

not perform a meta-regression to adjust for these poten-

tial confounders as the primary studies do not provide

sufficient data to do so. Furthermore, all NSAIDs were

evaluated as one group in this study, but not all individual

NSAIDs may increase VTE risk.

In conclusion, the results of our meta-analysis demon-

strate a statistically significantly increased VTE risk among

NSAID users. Physician should be aware of this associ-

ation and NSAIDs should be prescribed with caution,

especially in patients at high baseline risk of VTE.

Rheumatology key messages

.

This

is

the

first

meta-analysis

to

investigate

the

association

between

NSAIDs

and

venous

thromboembolism.

.

This study demonstrated a statistically significant

increased risk of venous thromboembolism among

NSAID users.

Funding: No specific funding was received from any fund-

ing bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit

sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no

conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

are available at Rheumatology

Online.

References

1

Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P et al. Incidence

and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based

study. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:6929.

2

Cushman M, Tsai AW, White RH et al. Deep venous

thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the

longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology.

Am J Med 2004;117:1925.

3

Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Estimated case fatality rate

of pulmonary embolism, 19791998. Am J Card 2004;93:

11979.

4

Ungprasert P, Kittanamongkolchai W, Price CD et al. What

is the ‘‘safest’’ non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? Am

Med J 2012;3:11523.

5

Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H et al. Cardiovascular

events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma

chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1092102.

6

McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition

of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observa-

tional studies of selective and nonselective of cyclooxy-

genase 2. JAMA 2006;296:163344.

7

Franchini M, Mannucci PM. Venous and arterial throm-

bosis: different sides of the same coin? Eur J Intern Med

2008;19:47681.

8

Prandoni P. Link between arterial and venous disease.

J Intern Med 2007;262:34150.

9

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa

scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized

studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:6035.

10 Tsai AW, Cushman M, Rosamond WD et al.

Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism

incidence: the longitudinal investigation of thrombo-

embolism etiology. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:11829.

F

IG

. 4

Funnel plot of all included studies

RR: risk ratio; SE: standard error.

6

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

Patompong Ungprasert et al.

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

11 Huerta C, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Garcia-

Rodriguez LA. Risk factors and short-term mortality of

venous thromboembolism diagnosed in primary care set-

ting in the United Kingdom. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:

93543.

12 Lacut K, van der Maaten J, Le Gal G et al. Antiplatelet

drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: result from

the EDITH case-control study. Haematologica 2008;93:

11178.

13 Biere-Rafi S, Di Nisio M, Gerdes V et al. Non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs and risk of pulmonary embolism.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:63542.

14 Schmidt M, Christiansen CF, Horvath-Puho E et al. Non-

steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of venous

thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 2011;9:132633.

15 Bergendal A, Adami J, Bahmanyar S et al. Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drug use and venous thromboembolism

in women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:65866.

16 Davies HT, Crombie IK, Tavakoli M. When can odds ratio

mislead? BMJ 1998;316:98991.

17 DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials.

Control Clin Trial 1986;7:17788.

18 Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG.

Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;

327:55760.

19 Graff J, Skarke C, Klinkhardt U et al. Effect of selective

COX-2 inhibition on prostanoids and platelet physiology in

young healthy volunteers. J Thromb Haemost 2007;12:

237685.

20 McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition

of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observa-

tional studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of

cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA 2006;296:163344.

21 Anderson DR, Dunbar MJ, Bohm ER et al. Aspirin

versus low-molecular-weight heparin for extended

venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip

arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:

8006.

22 Larocca A, Cavallo F, Bringhen S et al. Aspirin or

enoxaprarin thromboprophylaxis for patients with newly

diagnosed multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide.

Blood 2012;119:9339.

23 Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Spanuchart I, Thongprayoon C,

Knight EL. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients

with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:297304.

24 Johannesdottir SA, Schmidt M, Horvath-Puho.,

Sorensen HT. Autoimmune skin and connective tissue

diseases and risk of venous thromboembolism: a popu-

lation-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost 2012;

10:81521.

25 Ungprasert P, Sanguankeo A. Risk of venous thrombo-

embolism in patients with idiopathic inflammatory

myositis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Rheumatol Int 2014. [Epub ahead of print].

www.rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org

7

NSAIDs and risk of VTE

at Warszawski Uniwersytet Medyczny on November 7, 2014

http://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org/

Downloaded from

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Consumption of cocoa, tea and coffee and risk of cardiovascular disease

J L Allen Jr Foreign priests and risk of plunder

Effect of Drugs and Alcohol on Teenagers

Describe the role of the dental nurse in minimising the risk of cross infection during and after the

Encyclopedia of Mind Enhancing Foods, Drugs and Nutritional Substances ~ [TSG]

FALLS, INJURIES DUE TO FALLS, AND THE RISK OF ADMISSION

Psychedelic Drugs And The Awakening Of Kundalini Donald J

(Ebook) Charles Tart Sex, Drugs And Altered States Of Consciousness

The Risk of Debug Codes in Batch what are debug codes and why they are dangerous

MENDOZA LINE, THE Full of Light and Full of Fire CD (Misra) MSR37 , Non Exportable to UK, Europe an

Study Flavanoid Intake and the Risk of Chronic Disease

Assessment of balance and risk for falls in a sample of community dwelling adults aged 65 and older

Harris, Sam Drugs and the Meaning of Life

Congressional Budget Office Federal Debt and the Risk of a Fiscal Crisis

6 6 Detection and Identification of Drugs; Summary

Cancer Risk According to Type and Location of ATM Mutation in Ataxia Telangiectasia Families

05 DFC 4 1 Sequence and Interation of Key QMS Processes Rev 3 1 03

więcej podobnych podstron