Primary source

In the study of history as an academic discipline, a primary source (also called

original source or evidence) is an artifact, a document, diary, manuscript,

autobiography, a recording, or any other source of information that was created at

the time under study. It serves as an original source of information about the topic.

Similar definitions can be used in library science, and other areas of scholarship,

although different fields have somewhat different definitions. In journalism, a

primary source can be a person with direct knowledge of a situation, or a document

written by such a person.

Primary sources are distinguished from secondary sources, which cite, comment on,

or build upon primary sources. Generally, accounts written after the fact with the

benefit (and possible distortions) of hindsight are secondary.

may also be a primary source depending on how it is used.

would be considered a primary source in research concerning its author or about his

or her friends characterized within it, but the same memoir would be a secondary

source if it were used to examine the culture in which its author lived. "Primary" and

"secondary" should be understood as relative terms, with sources categorized

according to specific historical contexts and what is being studied.

The significance of source classification

In scholarly writing, an important objective of classifying sources is to determine their independence and reliability.

such as historical writing, it is almost always advisable to use primary sources and that "if none are available, it is only with great

caution that [the author] may proceed to make use of secondary sources."

Sreedharan believes that primary sources have the most

direct connection to the past and that they "speak for themselves" in ways that cannot be captured through the filter of secondary

sources.

This wall painting found in the

Roman city of Pompeii is an example

of a primary source about people in

Pompeii in Roman times. (Portrait of

Paquius Proculo)

Contents

The significance of source classification

History

In scholarly writing, the objective of classifying sources

is to determine the independence and reliability of

sources.

Though the terms primary source and

secondary source originated in historiography as a way to

trace the history of historical ideas, they have been

applied to many other fields. For example, these ideas

may be used to trace the history of scientific theories,

literary elements and other information that is passed

from one author to another.

In scientific literature, a primary source is the original publication of a scientist's new data, results and theories. In political history,

primary sources are documents such as official reports, speeches, pamphlets, posters, or letters by participants, official election

returns and eyewitness accounts. In the history of ideas or intellectual history, the main primary sources are books, essays and letters

written by intellectuals; these intellectuals may include historians, whose books and essays are therefore considered primary sources

for the intellectual historian, though they are secondary sources in their own topical fields. In religious history, the primary sources

are religious texts and descriptions of religious ceremonies and rituals.

A study of cultural history could include fictional sources such as novels or plays. In a broader sense primary sources also include

artifacts like photographs, newsreels, coins, paintings or buildings created at the time. Historians may also take archaeological

artifacts and oral reports and interviews into consideration. W

ritten sources may be divided into three types.

Narrative sources or literary sources tell a story or message. They are not limited to fictional sources (which can

be sources of information for contemporary attitudes) but include

diaries, films, biographies, leading philosophical

works and scientific works.

Diplomatic sources include charters and other legal documents which usually follow a set format.

Social documents are records created by organizations, such as registers of births and tax records.

In historiography, when the study of history is subject to historical scrutiny, a secondary source becomes a primary source. For a

biography of a historian, that historian's publications would be primary sources. Documentary films can be considered a secondary

source or primary source, depending on how much the filmmaker modifies the original sources.

The Lafayette College Library, provides a synopsis of primary sources in several areas of study:

"The definition of a primary source varies depending upon the academic discipline and the context in which it is used.

In the humanities, a primary source could be defined as something that was created either during the

time period being studied or afterward by individuals reflecting on their involvement in the events of

that time.

In the social sciences, the definition of a primary source would be expanded to include numerical data

that has been gathered to analyze relationships between people, events, and their environment.

In the natural sciences, a primary source could be defined as a report of original findings or ideas.

These sources often appear in the form of research articles with sections on methods and results."

Although many primary sources remain in private hands, others are located in archives, libraries, museums, historical societies, and

special collections. These can be public or private. Some are affiliated with universities and colleges, while others are government

entities. Materials relating to one area might be spread over a large number of different institutions. These can be distant from the

original source of the document. For example, the Huntington Library in California houses a large number of documents from the

United Kingdom.

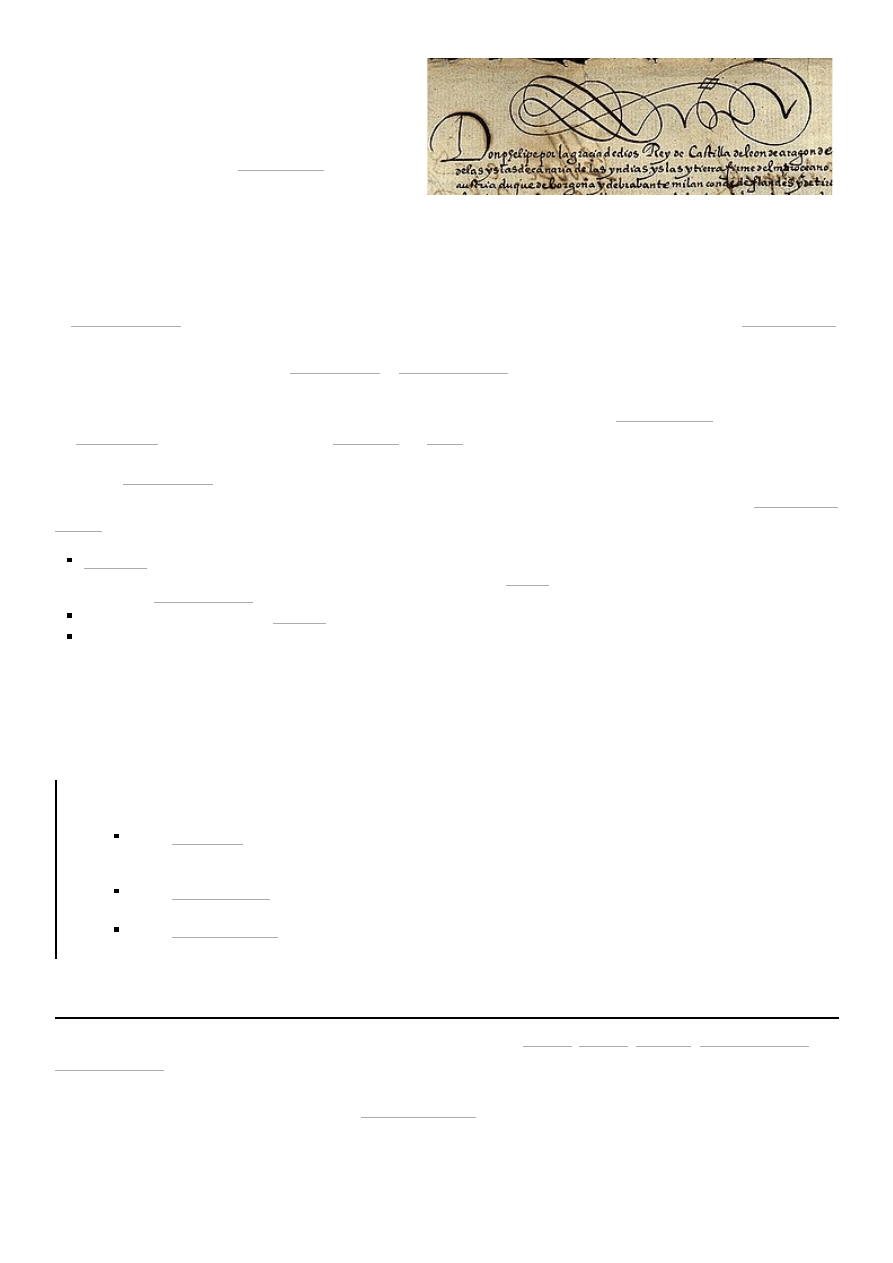

From a letter of Philip II, King of Spain, 16th century

Other fields

Finding primary sources

In the US, digital copies of primary sources can be retrieved from a number of places. The Library of Congress maintains several

digital collections where they can be retrieved. Some examples are American Memory and Chronicling America. The National

Archives and Records Administration also has digital collections in Digital Vaults. The Digital Public Library of America searches

across the digitized primary source collections of many libraries, archives, and museums. The Internet Archive also has primary

source materials in many formats.

In the UK, the National Archives provides a consolidated search of its own catalogue and a wide variety of other archives listed on

the Access to Archives index. Digital copies of various classes of documents at the National Archives (including wills) are available

from DocumentsOnline. Most of the available documents relate to England and Wales. Some digital copies of primary sources are

available from the National Archives of Scotland. Many County Record Offices collections are included in Access to Archives, while

others have their own on-line catalogues. Many County Record Of

fices will supply digital copies of documents.

In other regions, Europeana has digitized materials from across Europe while the World Digital Library and Flickr Commons have

items from all over the world. Trove has primary sources from Australia.

Most primary source materials are not digitized and may only be represented online with a record or finding aid. Both digitized and

not digitized materials can be found through catalogs such as WorldCat, the Library of Congress catalog, the National Archives

catalog, and so on.

History as an academic discipline is based on primary sources, as evaluated by the community of scholars, who report their findings

in books, articles and papers. Arthur Marwick says "Primary sources are absolutely fundamental to history."

Ideally, a historian

will use all available primary sources that were created by the people involved at the time being studied. In practice some sources

have been destroyed, while others are not available for research. Perhaps the only eyewitness reports of an event may be memoirs,

autobiographies, or oral interviews taken years later. Sometimes the only evidence relating to an event or person in the distant past

was written or copied decades or centuries later. Manuscripts that are sources for classical texts can be copies of documents, or

fragments of copies of documents. This is a common problem in classical studies, where sometimes only a summary of a book or

letter has survived. Potential difficulties with primary sources have the result that history is usually taught in schools using secondary

sources.

Historians studying the modern period with the intention of publishing an academic article prefer to go back to available primary

sources and to seek new (in other words, forgotten or lost) ones. Primary sources, whether accurate or not, offer new input into

historical questions and most modern history revolves around heavy use of archives and special collections for the purpose of finding

useful primary sources. A work on history is not likely to be taken seriously as scholarship if it only cites secondary sources, as it

does not indicate that original research has been done.

However, primary sources – particularly those from before the 20th century – may have hidden challenges. "Primary sources, in fact,

are usually fragmentary, ambiguous and very difficult to analyse and interpret."

Obsolete meanings of familiar words and social

context are among the traps that await the newcomer to historical studies. For this reason, the interpretation of primary texts is

typically taught as part of an advanced college or postgraduate history course, although advanced self-study or informal training is

also possible.

The following questions are asked about primary sources:

What is the tone?

Who is the intended audience?

What is the purpose of the publication?

What assumptions does the author make?

What are the bases of the author's conclusions?

Does the author agree or disagree with other authors of the subject?

Does the content agree with what you know or have learned about the issue?

Where was the source made? (questions of systemic bias)

Using primary sources

In many fields and contexts, such as historical writing, it is almost always advisable to use primary sources if possible, and "if none

are available, it is only with great caution that [the author] may proceed to make use of secondary sources."

sources avoid the problem inherent in secondary sources in which each new author may distort and put a new spin on the findings of

prior cited authors.

"A history, whose author draws conclusions from other than primary sources or secondary sources actually based on

primary sources, is by definition fiction and not history at all."

— Kameron Searle

However, a primary source is not necessarily more of an authority or better than a secondary source. There can be bias and tacit

unconscious views which twist historical information.

"Original material may be... prejudiced, or at least not exactly what it claims to be."

— David Iredale[13]

The errors may be corrected in secondary sources, which are often subjected to peer review, can be well documented, and are often

written by historians working in institutions where methodological accuracy is important to the future of the author's career and

reputation. Historians consider the accuracy and objectiveness of the primary sources that they are using and historians subject both

primary and secondary sources to a high level of scrutiny. A primary source such as a journal entry (or the online version, a blog), at

best, may only reflect one individual's opinion on events, which may or may not be truthful, accurate, or complete.

Participants and eyewitnesses may misunderstand events or distort their reports, deliberately or not, to enhance their own image or

importance. Such effects can increase over time, as people create a narrative that may not be accurate.

For any source, primary or

secondary, it is important for the researcher to evaluate the amount and direction of bias.

As an example, a government report may

be an accurate and unbiased description of events, but it may be censored or altered for propaganda or cover-up purposes. The facts

can be distorted to present the opposing sides in a negative light. Barristers are taught that evidence in a court case may be truthful

but may still be distorted to support or oppose the position of one of the parties.

Many sources can be considered either primary or secondary, depending on the context in which they are examined.

Moreover, the

distinction between primary and secondary sources is subjective and contextual,

so that precise definitions are difficult to

A book review, when it contains the opinion of the reviewer about the book rather than a summary of the book, becomes a

If a historical text discusses old documents to derive a new historical conclusion, it is considered to be a primary source for the new

conclusion. Examples in which a source can be both primary and secondary include an obituary

or a survey of several volumes of

a journal counting the frequency of articles on a certain topic.

Whether a source is regarded as primary or secondary in a given context may change, depending upon the present state of knowledge

within the field.

For example, if a document refers to the contents of a previous but undiscovered letter, that document may be

considered "primary", since it is the closest known thing to an original source; but if the letter is later found, it may then be

considered "secondary"

In some instances, the reason for identifying a text as the "primary source" may devolve from the fact that no copy of the original

source material exists, or that it is the oldest extant source for the information cited.

Strengths and weaknesses

Classifying sources

Historians must occasionally contend with forged documents that purport to be primary sources. These forgeries have usually been

constructed with a fraudulent purpose, such as promulgating legal rights, supporting false pedigrees, or promoting particular

interpretations of historic events. The investigation of documents to determine their authenticity is called

For centuries, Popes used the forged Donation of Constantine to bolster the Papacy's secular power. Among the earliest forgeries are

false Anglo-Saxon charters, a number of 11th- and 12th-century forgeries produced by monasteries and abbeys to support a claim to

land where the original document had been lost or never existed. One particularly unusual forgery of a primary source was

perpetrated by Sir Edward Dering, who placed false monumental brasses in a parish church.

In 1986, Hugh Trevor-Roper

"authenticated" the Hitler Diaries, which were later proved to be forgeries. Recently, forged documents have been placed within the

UK National Archives in the hope of establishing a false provenance.

However, historians dealing with recent centuries rarely

encounter forgeries of any importance.

[3]:22–25

Examples

Others

Archival research

Historiography

Source criticism

Source literature

Source text

Historical document

Secondary source

Tertiary source

Original research

UNISIST model

Scientific journalism

Scholarly method

1. "

Primary, secondary and tertiary sources (https://web.archive.org/web/20130726061349/http://www

". University Libraries, University of Maryland.

2. "

Primary and secondary sources (http://www.ithacalibrary.com/sp/subjects/primary)

3.

, Harvard Guide to American History (1954)

An Introduction to the Historiography of Science (https://books.google.com/books?id=d2zy_QS

q2b0C&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121&dq=%22secondary+source%22+historiography)

. "[T]he distinction is not a sharp one. Since a source is only a source in a specific

historical context, the same source object can be both a primary or secondary source according to what it is used

for."

Between Two Cultures:An Introduction to Economic History (https://books.google.com/?id=

GIqRTlepwmoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=cipolla)

A Textbook of Historiography, 500 B.C. to A.D. 2000 (https://books.google.com/books?id=AI

Gq85RVvdoC&pg=PA302&dq=historiography+%22primary+source%22+%22secondary+source%22)

. "[I]t is through the primary sources that the past indisputably imposes its

reality on the historian. That this imposition is basic in any understanding of the past is clear from the rules that

documents should not be altered, or that any material damaging to a historian's argument or purpose should not be

left out or suppressed. These rules mean that the sources or the texts of the past have an integrity and that they do

indeed 'speak for themselves', and that they are necessary constraints through which past reality imposes itself on

the historian."

7.

. Research

Guides at Tufts University. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

Forgeries

See also

References

Benjamin, Jules R (2004). A Student's Guide to History. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

8. Howell, Martha C.; Prevenier, Walter. (2001). From reliable sources : an introduction to historical method

. Ithaca,

N.Y.: Cornell University Press. pp. 20–22.

9. Cripps, Thomas (1995). "Historical Truth: An Interview with Ken Burns". American Historical Review. The American

Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 3. 100 (3): 741–764.

10.2307/2168603 (https://doi.org/10.2307%2F2168603)

2168603 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/2168603)

.

10.

"Primary Sources: what are they?" (http://library.lafayette.edu/help/primary/definitions)

11. Marwick, Arthur. "Primary Sources: Handle with Care". In Sources and Methods for Family and Community

Historians: A Handbook edited by Michael Drake and Ruth Finnegan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1997.

12. Ross, Jeffrey Ian (2004). "Taking Stock of Research Methods and Analysis on Oppositional Political T

errorism". The

American Sociologist. 35 (2): 26–37.

10.1007/BF02692395 (https://doi.org/10.1007%2FBF02692395)

. "The

analysis of secondary source information is problematic. The further an investigator is from the primary source, the

more distorted the information may be. Again, each new person may put his or her spin on the findings.

"

13. Iredale, David (1973). Enjoying archives: what they are, where to find them, how to use them

. Newton Abbot, David

14. Barbara W. Sommer and Mary Kay Quinlan, The Oral History Manual (2002)

15. Library of Congress, " Analysis of Primary Sources"

online 2007 (http://memory.loc.gov/learn/lessons/psources/analy

16. Dalton, Margaret Stieg; Charnigo, Laurie (September 2004).

"Historians and Their Information Sources" (http://crl.acr

l.org/content/65/5/400.full.pdf+html)

. College & Research Libraries. 65 (5): 419.

10.5860/crl.65.5.400 (https://doi.

17. Delgadillo, Roberto; Lynch, Beverly (May 1999).

"Future Historians: Their Quest for Information" (http://crl.acrl.org/co

. College & Research Libraries. 60 (3): 245–259, at 253. "[T]he same document can be a

primary or a secondary source depending on the particular analysis the historian is doing.

"

"Book reviews" (http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=book%20review)

. Scholarly

definition document. Princeton. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

19. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (2011).

"Book reviews" (http://www.lib.vt.edu/find/byformat/bookrev

. Scholarly definition document. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Retrieved

22 September 2011.

History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction

(https://books.google.com/?id=__oDQ

6yDO7kC&pg=PA366&dq=%22secondary+source%22+historiography)

. University of Toronto Press. p. 366.

21. Henige, David (1986). "Primary Source by Primary Source? On the Role of Epidemics in New W

orld Depopulation".

Ethnohistory. Ethnohistory, Vol. 33, No. 3. 33 (3): 292–312, at 292.

10.2307/481816 (https://doi.org/10.2307%2F

481816 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/481816)

. "[T]he term 'primary' inevitably carries a relative

meaning insofar as it defines those pieces of information that stand in closest relationship to an event or process

in

the present state of our knowledge. Indeed, in most instances the very nature of a primary source tells us that it is

actually derivative.…[H]istorians have no choice but to regard certain of the available sources as 'primary' since they

are as near to truly original sources as they can now secure

"

22.

, p. 292.

23. Ambraseys, Nicholas; Melville, Charles Peter; Adams, Robin Dartrey (1994).

The Seismicity of Egypt, Arabia, and

the Red Sea (https://books.google.com/?id=dtVqdSKnBq4C&pg=P

A7&dq=historiography+%22primary+source%22

. Cambridge University Press. p. 7.

a primary source for the period contemporary with the author

, a secondary source for earlier material derived from

previous works, but also a primary source when these earlier works have not survived

"

24. Everyone has Roots: An Introduction to English Genealogy by Anthony J. Camp, published by Genealogical Pub.

Co., 1978

25.

"Introduction to record class R4" (http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C16525)

Retrieved 8 March 2015.

26. Leppard, David (4 May 2008).

"Forgeries revealed in the National Archives – T

imes Online" (http://www.timesonline.c

Craver, Kathleen W (1999). Using Internet Primary Sources to Teach Critical Thinking Skills in History. Westwood,

CT: Greenwood Press.

Wood Gray (1991) [1964]. Historian's Handbook: A Key to the Study and Writing of History

. 2nd ed. Waveland

.

Marius, Richard; Page, Melvin Eugene (2005). A short guide to writing about history. New York: Pearson Longman.

.

Sebastian Olden-Jørgensen (2005). Til kilderne!: introduktion til historisk kildekritik (in Danish). [To the sources:

Introduction to historical source criticism]. København: Gads Forlag.

Primary sources repositories

Primary Sources from World War One and Two: War-letters.com

Database of mailed letters to and from soldiers

during major world conflicts from the Napoleonic W

ars to World War Two.

Fold3.com – Over 60,000,000 Primary Source Documents

A listing of over 5000 websites

describing holdings of manuscripts, archives, rare books, historical photographs, and

other primary sources from the

.

in the collections of major research libraries using

Digitalized Primary Sources and Historical Artifacts from 1786 – present

A collection of religious texts and books from the

All sources repositories

– The Free Library – the

project that collects, edits, and catalogs all

Essays and descriptions of primary, secondary and other sources

"Research Using Primary Sources"

University of Maryland Libraries

"How to distinguish between primary and secondary sources"

University of California, Santa Cruz

Library

Joan of Arc: Primary Sources Series

– Example of a publication focusing on primary source documents- the

Historical Association of Joan of Arc Studies

Finding Historical Primary Sources

University of California, Berkeley

"Primary versus secondary sources"

Bowling Green State University

Finding primary sources in world history

from the Center for History and New Media,

used when describing archival and other primary source materials on

Links to many online history archival sources.

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Primary_source&oldid=813612208

"

This page was last edited on 4 December 2017, at 09:27.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this

site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia

Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

External links

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

3 Primary Sources Vol 3

System open source NauDoc (1)

Power Source Current Flow Chart

Paralleling Arc Welding Power Sources

Ando Correlation Factors Describing Primaryand

Lößner, Marten Geography education in Hesse – from primary school to university (2014)

Apple ImageWriter II Service Source

Migracja do Open Source

kipling trois troupiers source

Primary I CAN

PrimaryAS

Czytanie kodu Punkt widzenia tworcow oprogramowania open source czytko

DragonQuest Open Source

Improvised Primary Explosives

13 Starke und schwache Seiten der Lerner in der Primarstufeid 14500

Primary Games

więcej podobnych podstron