Psychiatric Quarterly, Vol. 77, No. 1, Spring 2006 (

C

2006)

DOI: 10.1007/s11126-006-7962-x

COMPARISON OF ATTACHMENT STYLES

IN BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

AND OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE

PERSONALITY DISORDER

Cindy J. Aaronson, M.S.W., Ph.D., Donna S. Bender, Ph.D.,

Andrew E. Skodol, M.D., and John G. Gunderson, M.D.

The intense, unstable interpersonal relationships characteristic of patients

with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are thought to represent insecure at-

tachment. The Reciprocal Attachment Questionnaire was used to compare the

attachment styles of patients with BPD to the styles of patients with a contrast-

ing personality disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD).

The results showed that patients with BPD were more likely to exhibit angry

withdrawal and compulsive care-seeking attachment patterns. Patients with

BPD also scored higher on the dimensions of lack of availability of the attach-

ment figure, feared loss of the attachment figure, lack of use of the attachment

figure, and separation protest. The findings may be relevant for understanding

Cindy J. Aaronson, M.S.W., Ph.D., is affiliated with Department of Psychiatry, Mount

Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Donna S. Bender, Ph.D. and Andrew E. Skodol, M.D., are affiliated with Depart-

ment of Personality Studies, Columbia University, New York State Psychiatric Institute,

New York, NY.

John G. Gunderson, M.D., is affiliated with Personality and Psychosocial Research,

McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA.

Address correspondence to Cindy J. Aaronson, M.S.W., Ph.D., Mount Sinai School of

Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Place, Box 1230, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: cindy.

aaronson@mssm.edu.

69

0033-2720/06/0300-0069/0

C

2006 Springer Science

+Business Media, Inc.

70

PSYCHIATRY QUARTERLY

the core interpersonal psychopathology of BPD and for managing therapeutic

relationships with these patients.

KEY WORDS: attachment style; attachment patterns; borderline personality disorder;

obsessive compulsive personality disorder.

Attachment theory has increasingly been employed in the literature

to discriminate amongst different types of psychopathology, especially

personality disorders (1–4). The theory’s usefulness for understanding

personality disorders (PDs) lies in its focus on interpersonal function-

ing, which is typically impaired in individuals with PDs (5–6). This is

particularly the case in patients with borderline personality disorder

(BPD), whose interpersonal relationships are characteristically intense

and unstable. BPD has been “conceived as a condition of profound inse-

cure attachment, with extreme oscillations between attachment and de-

tachment, between a longing and yearning for secure affectional bonds

alternating with a dread and avoidance of such closeness (7).”

Attachment theory is primarily concerned with how personality de-

velops in the context of relationships with others. Attachment patterns,

unfolding from birth, are influenced by unique characteristics of the

infant, the parent, and the quality of their interactions (8). Children

develop a ‘secure base’ as toddlers when the attachment figure (usu-

ally the mother) provides stability and safety, which then allows the

child to explore and satisfy his/her curiosity (9). As the child’s devel-

opment proceeds, s/he creates a set of mental models of him/herself

and of others, based on repeated patterns of interactions with

significant others. These representations may influence many aspects

of future relationships, including expectations of acceptance and

rejection.

Securely attached infants perceive their caregivers as reliable and

protective when they are in distress; anxious-ambivalently attached

infants explore without confidence, alternately seek contact and re-

sist it, and are not easily comforted when distressed; and avoidant

infants “actively avoid contact with their caregivers (5).” Both anxious-

ambivalent and avoidant types of insecurely attached infants unsuc-

cessfully use their caregivers to gain security when distressed or to

provide the secure base needed for comfortable exploration.

The DSM-IV criterion for BPD “frantic efforts to avoid real or imag-

ined abandonment” (10) has proved to be a discriminating feature of

the disorder (11), confirming Masterson’s theory that fear of abandon-

ment is the central factor in the development of BPD (12). The fear and

intolerance of being alone may provoke behaviors such as proximity

CINDY J. AARONSON ET AL.

71

seeking and clinging, which parallel the behavior seen in the anxious-

ambivalent insecure attachment style described by Ainsworth (13).

The Reciprocal Attachment Questionnaire (RAQ) was developed by

West and Sheldon-Keller in order to examine adult attachment style.

Using the RAQ, they found that a high level of feared loss of the attach-

ment figure and a low sense of a secure base were significantly related

to BPD (14–15). In another study, West, Rose, and Sheldon(16) found

that three dimensions of insecure attachment (feared loss of the at-

tachment figure, compulsive care-seeking, and angry withdrawal) were

related significantly to BPD.

Bender, Farber, and Geller (17) found that insecurely attached pa-

tients more frequently exhibited Cluster B personality traits (histrionic,

narcissistic, antisocial and borderline) than securely attached patients.

Using the dimensions of the RAQ (18), they found that subjects with

borderline traits exhibited proximity seeking wishes, yet perceived the

attachment figure as unavailable. The authors suggested that this was

consistent with Kernberg’s (19) view that those with BPD have not

achieved object constancy, that is, a consistent ability to feel connected

or attached to the loved caregiver through access to a stable internalized

representation of that figure.

There are few empirical studies comparing the attachment styles of

patients with BPD to those of patients with other PDs, or specifically

with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD). Theoretically,

one would expect OCPD to be at the opposite end of a spectrum from

BPD. Rather than being impulsive, those with OCPD “venerate logic, ra-

tionality, self-control, and loyalty to established values, and deride those

who may be emotionally expressive, behave impulsively, are pleasure

seeking, or hold unorthodox opinions (20).” Since OCPD is less impair-

ing than some of the other PDs (21), one might expect evidence of less

disturbed or different patterns of attachment in patients with OCPD

compared to those with BPD.

Using the RAQ, Bender (22) assessed the relationship of attachment

dimensions to various character pathology traits. Borderline charac-

teristics were significantly positively correlated with four dimensions—

perceived unavailability of the caregiver, feared loss, proximity seeking,

and separation protest—while compulsive traits were significantly neg-

atively correlated with these same four attachment dimensions. Fossati

and colleagues (23) compared 44 subjects with BPD to two other person-

ality disordered groups (98 subjects with cluster B PDs but not BPD and

39 subjects with mixed cluster A and C PDs) and to two groups with

no personality disorder (70 mentally ill subjects and 206 not ill com-

munity members) on attachment patterns using the Attachment Style

Questionnaire (ASQ) (24). The number of subjects who met criteria for

72

PSYCHIATRY QUARTERLY

OCPD in this sample was 9 (23%). The ASQ has five dimensions of

attachment including confidence that refers to self-esteem and confi-

dence in relationships with others (high score indicates secure attach-

ment), need for approval, discomfort with closeness, relationships as

secondary, and preoccupation with relationships (high score indicates

insecure attachment). The results showed no differences between the

BPD group and the two PD groups on any of the ASQ dimensions; the

not ill and no PD groups were significantly more confident, however.

In other words, both the BPD and other PD groups exhibited insecure

attachment while the non-PD groups exhibited secure attachment.

The present study sought to determine whether attachment style

would differentiate a group of patients with BPD from a comparison

group with OCPD, using measures of both patterns and dimensions

of attachment. This study differs from previous research in its use of

a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of personality disorders

rather than the use of self-report or chart/clinician diagnosis. Further,

the use of a homogeneous personality disordered comparison group

rather than a mixed PD group or a normal, college student group has

not been common in prior studies.

METHODS

Participants

Subjects were recruited from an existing multi-site longitudinal study

of personality disorders (25). Based on data from semi-structured in-

terviews (see below), 90 participants were assigned to two groups: 50

with DSM-IV BPD, and 40 with DSM-IV OCPD. The participants in-

cluded 74 women (82%) and 16 men (18%) between the ages of 21 and

50 (mean

= 31.73, SD = 8.30). Single participants (N = 61) comprised

67% of the total, while 17% (N

= 15) were married, 15% (N = 13) were

divorced and 1% (N

= 1) was widowed. The majority of the participants

were Caucasian (66%, N

= 59); 12% (N = 11) were African American;

23% (N

= 20) were Hispanic, Asian or Native American. No individuals

with organic mental disorder or mental retardation, current or active

psychosis or a history of schizophrenia, or current substance intoxica-

tion or withdrawal were included in the study.

Recruitment Procedures

Participants were contacted for recruitment through a letter sent by

the study coordinator or by telephone. The first author (CJA) contacted

CINDY J. AARONSON ET AL.

73

sample subjects by telephone, explained what participation entailed,

received verbal informed consent and a telephone interview was then

scheduled and completed. Face-to-face interviews were offered, but al-

most all participants elected to conduct the interview over the tele-

phone. Written informed consent was acquired by mail for telephone

interviews and in person for face-to-face interviews.

Measures

Attachment variables were measured using the Reciprocal Attachment

Questionnaire (RAQ), a 43-item self–report instrument yielding five

insecure dimensions and four insecure pattern categories. The respon-

dent is asked to rate on a 5-point Likert-type rating scale the degree

to which each statement about a current attachment figure is true.

The five dimensions are 1) proximity seeking, 2) separation protest,

3) feared loss, 4) availability of the attachment figure and 5) use of

the attachment figure. The patterns of attachment include four cat-

egories of insecure/anxious attachment: 1) angry withdrawal, 2) com-

pulsive care-giving, 3) compulsive self-reliance, and 4) compulsive care-

seeking. These latter patterns of attachment represent Bowlby’s (26)

three patterns of insecure attachment: anxious attachment, compul-

sive self-reliance, and compulsive care-giving.

Personality disorder diagnoses were assessed using the Diagnostic

Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) (27) when sub-

jects were originally recruited for the longitudinal study. The DIPD-IV

is a semi-structured interview that assesses personality disorder symp-

toms allowing the clinician to make diagnoses of 11 personality disor-

ders. The DIPD, as employed in this study, showed good to excellent

reliability with kappas ranging from .68 to .91 for inter-rater and .65

to .74 for test-retest reliability (28).

Analyses

The sample subjects were compared by personality disorder diagno-

sis for demographic characteristics using one-way ANOVA for age; chi-

square for gender, marital status, and race; and a Mann-Whitney U test

for level of education and socioeconomic status, as measured by the

Hollingshead-Redlich Scale. RAQ patterns of attachment and the five

attachment dimensions were analyzed comparing means of each PD

group using Fisher’s t-test. While the patterns are generally used as

categorical variables, in this case, each of the three was analyzed as

74

PSYCHIATRY QUARTERLY

dimensions. RAQ reliability was tested on the subscales (see below for

results).

RESULTS

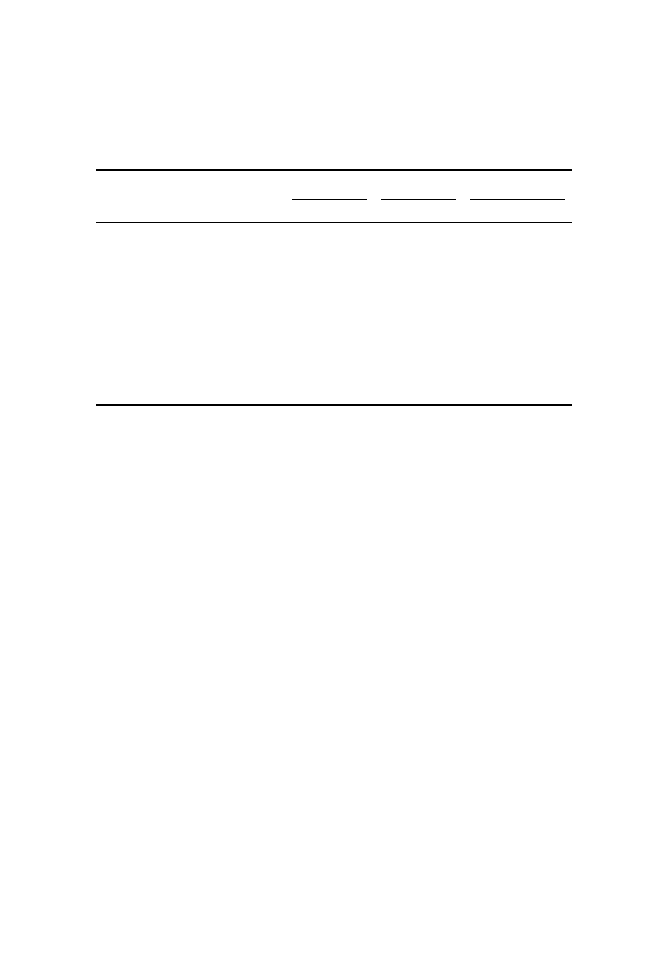

Participant Demographics

There were no significant differences between the groups for marital

status, race, or age. In both groups, most of the participants were single

(BPD: 70%, OCPD: 64%) (

χ

2

= 1.38, df = 3, p = .711). The predominant

race was Caucasian (BPD: 60%, OCPD: 72.5%) (

χ

2

= 2.22, df = 2, p =

.329). The mean age was 32.12 in the BPD group and was 31.25 in the

OCPD group (F

= .875, df = 2, p = .420). Females comprised 90% of the

BPD group and 72.5% of the OCPD group. The mean SES for the BPD

group was 2.16 (SD

= 0.96) and for the OCPD group was 1.80 (SD =

0

.99). The mean education level in the BPD group was 3.10 (SD = 1.33)

and 3.78 (SD

= 1.12) in the OCPD group where 1 = less than high

school, 3

= some college and 5 = graduate or professional degree. There

were significant differences between the groups for gender (

χ

2

= 4.66,

df

= 1, p = .031), education (U = 685.5, p = .008) and SES (U = 758.0,

p

= .036). Results are shown in Table 1.

Reliability

Reliability (ICC) was calculated for each of the four RAQ subscales

(angry withdrawal, compulsive care-giving, compulsive self-reliance,

and compulsive care-seeking). Each subscale or pattern consisted of

seven items and the reliability testing was based on a total of 117

RAQ questionnaires (from a larger sample used in a previous study)

(29). The results show that angry withdrawal (

α = .80), compulsive

care-giving (

α = .68) and compulsive care-seeking (α = .75) all had

acceptable alpha coefficients. The compulsive self-reliance subscale

had an unacceptable alpha coefficient (

α = .45) and was dropped from

further analysis.

Attachment Patterns

To test the hypothesis that attachment style would differentiate the

BPD group from the OCPD comparison group, the groups were

compared on the three reliable patterns of the RAQ (N

= 90). As seen in

CINDY J. AARONSON ET AL.

75

TABLE 1

Demographic Characteristics

BPD Group

OCPD Group

Analyses

N

%

N

%

χ

2

df

p

Race

Caucasian

30

60

29

72

.5

2

.22

2

.329

African American

6

12

5

12

.5

Hispanic/Asian/other

14

28

6

15

.0

Gender

Female

45

90

29

72

.5

4

.66

1

.031

Male

5

10

11

27

.5

Marital Status

Single

35

70

26

64

1

.38

3

.711

Married

7

14

8

21

Divorced

7

14

6

15

Widowed

1

2

0

0

U

p

Education level

<High School (H.S.)

5

10

1

2

.5

685

.5

.008

H.S. diploma/GED

10

20

5

12

.5

Partial college

19

38

9

22

.5

Bachelor’s degree

7

14

12

30

.0

Graduate/professional

9

18

13

32

.5

degree

SES levels

∗

1

13

26

19

47

.5

758

.0

.036

2

22

44

15

37

.5

3

9

18

1

2

.5

4

6

12

5

12

.5

Mean

2

.34

1

.70

SD

1

.04

0

.88

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

F

df

p

Age

32

.12

8

.19 31.25

8

.52

.242 1 .624

∗

Hollingshead-Redlich Socioeconomic Status: 1

= highest, 5 = lowest.

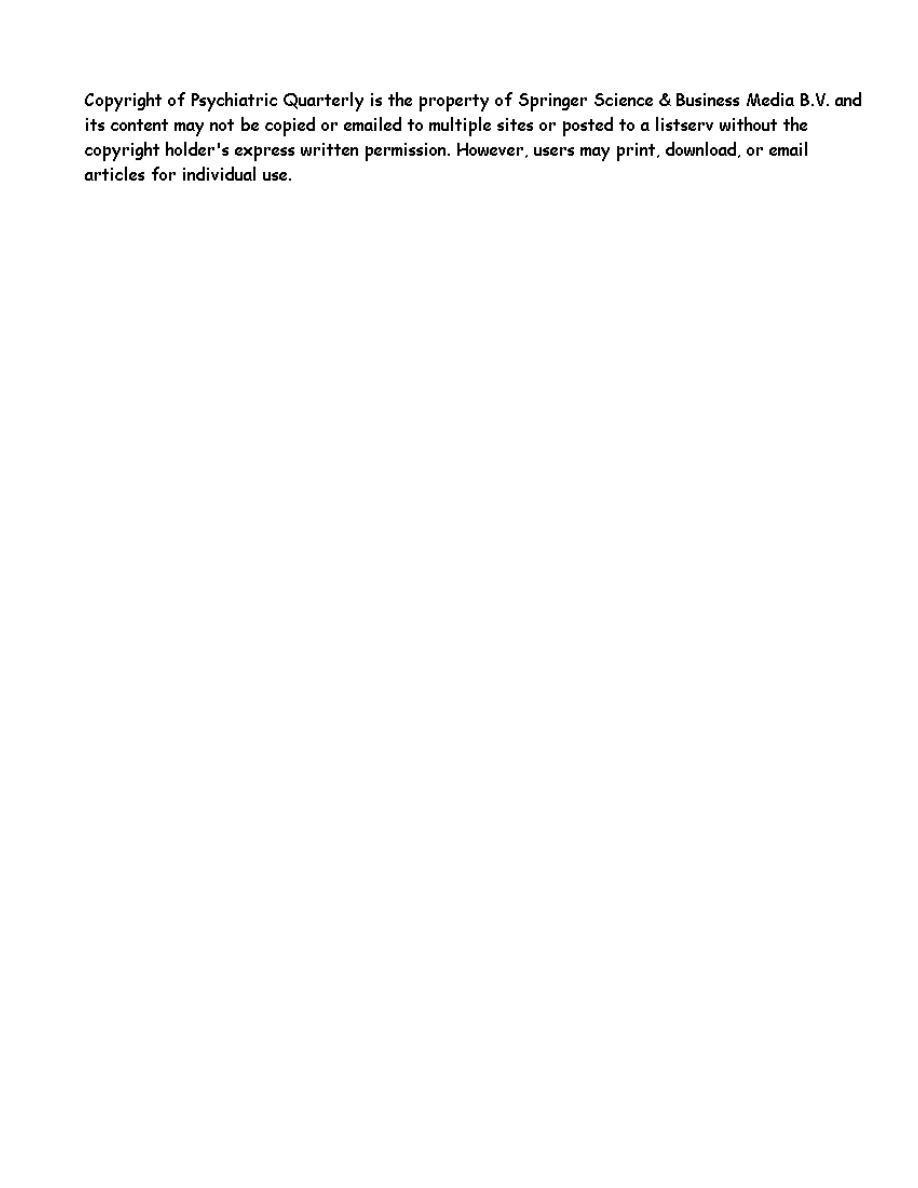

Table 2, the BPD group had significantly higher means than the OCPD

group for the angry withdrawal pattern (t

= 2.42, df = 88, p = .017)

and the compulsive care-seeking pattern (t

= 2.67, df = 88, p = .009).

There were no significant differences between the groups in compulsive

care-giving (t

= .484, df = 88, p = .630).

76

PSYCHIATRY QUARTERLY

TABLE 2

Patterns and Dimensions of Attachment for Two Personality

Disorder Groups

BPD

OCPD

Fisher’s t test

Attachment

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

t

df

p

Pattern

Angry withdrawal

17.93

5.63

15.15

5.10

2.42

88

.017

Compulsive care-giving

21.02

4.12

20.60

4.11

0.48

88

.630

Compulsive care-seeking

20.58

4.03

18.45

3.38

2.67

88

.009

Dimensions

Proximity seeking

7.75

2.50

6.96

2.75

1.44

88

.155

Separation protest

7.24

2.46

6.10

2.95

1.99

88

.050

Availability

8.14

2.61

6.53

2.20

3.13

88

.002

Feared loss

8.85

2.06

7.68

1.82

2.84

88

.006

Use of figure

7.69

2.54

5.95

2.48

3.26

88

.002

Note. BPD

= borderline personality disorder; OCPD = obsessive-compulsive personality

disorder.

Attachment Dimensions

Using RAQ total score, the two groups were compared on the five dimen-

sions of attachment using Fisher’s t-test. The results (also in Table 2)

show that there was a significant difference between the groups for four

of the dimensions. The BPD group had higher levels of lack of availabil-

ity (t

= 3.13, df = 88, p = .002), feared loss (t = 2.84, df = 88, p = .006),

lack of use of the figure (t

= 3.26, df = 88, p = .002), and separation

protest (t

= 1.99, df = 88, p = .05) compared to the OCPD group.

DISCUSSION

As expected, there were significant differences in the patterns of attach-

ment between the BPD group and the OCPD group. The BPD group had

higher mean total scores on the RAQ for the patterns angry withdrawal

and compulsive care-seeking, indicative of an anxious-ambivalent at-

tachment style, according to West and Sheldon-Keller (26). Thus, there

is a clear indication of the utility of attachment measures in distin-

guishing these two PD types.

This finding confirms other studies of attachment difficulties of pa-

tients with BPD (4). Melges and Swartz (30) found that borderlines’

high level of attachment insecurity leads to enmeshed dependence on

CINDY J. AARONSON ET AL.

77

the attachment figure. When anything interferes with that dependence,

a pattern of angry withdrawal is seen. West and colleagues (14) sug-

gest that the borderline individual vacillates between compulsive care-

seeking and angry withdrawal. The individual “yearns” or greatly de-

sires closeness and security from the attachment figure, thus becoming

enmeshed. This security seeking is often frustrated and gives rise to

the rage seen in the angry withdrawal pattern.

The dimensional scales for attachment also showed significant dif-

ferences between the BPD group and the OCPD group for lack of avail-

ability of the attachment figure, feared loss of the attachment figure,

lack of use of the attachment figure, and separation protest. This is

consistent with other studies demonstrating that those with BPD score

high on RAQ dimensions of feared loss, lack of availability, and prox-

imity seeking (4,17,22). The results also confirm that feared loss is a

discriminating feature of BPD, as demonstrated by West, Keller, Links,

& Patrick (14).

The significance of this study is that it confirms previous findings

that patients with BPD have disturbed attachment patterns, but also

that their insecure attachment differentiates them from a comparison

group that also has a personality disorder. In this study, the comparison

group was not expected to have secure attachment, yet attachment style

differentiated those with BPD from those with OCPD. The strength of

this study is in the use of both patterns and dimensions of attachment,

since attachment is complex and individuals may not easily fall into

one category because the boundaries between categories are not rigid

or distinct (5).

A limitation of this research may be the use of the RAQ for the mea-

surement of attachment patterns. There are no normative data to de-

termine what score constitutes secure attachment for the patterns. In

addition, self-report measures are dependent on the accuracy of self-

observations (31). The use of the Attachment Assessment Interview

(AAI) (32) might increase the quality of the data, but cost and time

of administration can be prohibitive. Another limitation of self-report

questionnaires is that they measure different domains of attachment,

such that results are not easily comparable between studies. There is

conceptual overlap between the categories in the RAQ and other mea-

sures of secure, dismissing, preoccupied and fearful attachment styles,

however. And, several studies have also shown an association between

BPD and the preoccupied attachment style (33–35), as well as the fear-

ful attachment style (34).

Although this study found significant differences between the BPD

and OCPD groups, little information about the specific nature of

78

PSYCHIATRY QUARTERLY

attachment in OCPD has been gleaned. Further research is needed to

determine what type of attachment style patients with OCPD do have,

whether insecure or secure, by comparison to personality disordered

groups other than BPD, as well as to not ill groups.

Attachment theory can be effectively employed in clinical work with

both adults and children. In working with adults with BPD, the ther-

apeutic relationship may mirror the attachment pattern of the client

with the attachment figure. The clinician should be aware of the vacil-

lation between care-seeking and angry withdrawal in the therapeutic

relationship. By providing a “secure base” in the therapeutic relation-

ship, the clinician fosters safety for exploration of the client’s feelings.

According to Dozier and Tyrrell (36), the secure environment provided

by the therapist allows for more effective work on changing maladap-

tive working models. Dozier (37) found that insecurely attached pa-

tients were less receptive to treatment. The perception that caregivers

and therapists are disappointing or rejecting decreases the likelihood

of engagement in treatment. This observation, when applied to border-

line personality, explains some of the instability observed in treatment

relationships of patients with BPD, who may change therapists repeat-

edly. The results of this study show that attachment is another means

of differentiating among character pathology types, and it may provide

guidance for engaging patients in the therapeutic process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by NIMH grants R01 MH 50839 and MH 50840. This publi-

cation has been reviewed and approved by the Publications Committee

of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study.

REFERENCES

1. Brennan KA, Shaver PR: Attachment styles and personality disorders: Their con-

nections to each other and to parental divorce, parental death, and perceptions of

parental caregiving. Journal of Personality Disorders 66:835–878, 1998.

2. Nickell AD, Waudby CJ, Trull TJ: Attachment, parental bonding and borderline per-

sonality disorder features in young adults. Journal of Personality Disorders 16:148–

159, 2002.

3. Rosenstein DS, Horowitz HA: Adolescent attachment and psychopathology. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:244–253, 1996.

4. Sack A, Sperling MB, Fagen G, et al.: Attachment style, history, and behavioral con-

trasts for a borderline and normal sample. Journal of Personality Disorders 10:88–

102, 1996.

CINDY J. AARONSON ET AL.

79

5. Bartholomew K, Kwong MJ, Hart SD: Attachment, in Handbook of personality dis-

orders: Theory, research and treatment. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford

Press, 2001.

6. Meyer B, Pilkonis PA, Proietti JM, et al.: Attachment styles and personality disorders

as predictors of symptom course. Journal of Personality Disorders 15:371–389, 2001.

7. Sable P: Attachment, detachment and borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy

34:171–181, 1997.

8. Lieberman AF, Pawl JH: Clinical applications of attachment theory, in Clinical Im-

plications of Attachment. Edited by Belsky J, Nezworski T. Hillsdale, New Jersey,

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

9. Bowlby J: Attachment and Loss, vol. 2, Separation-anxiety and Anger. New York,

Basic Books, 1973.

10. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Dis-

orders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, Author, 1994:652.

11. Gunderson JG, Kolb JE: Discriminating features of borderline patients. American

Journal of Psychiatry 135:792–796, 1978.

12. Masterson JF, Rinsley DB: The borderline syndrome: The role of the mother in the

genesis and psychic structure of the borderline personality. International Journal of

Psychoanalysis 56:163–177, 1975.

13. Gunderson JG: The borderline patient’s intolerance of aloneness: Insecure attach-

ments and therapist availability. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:752–758, 1996.

14. West M, Keller A, Links P, et al: Borderline disorder and attachment pathology.

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38: S16–S21, 1993.

15. West M, Sheldon-Keller A: The assessment of dimensions relevant to adult reciprocal

attachment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 37:600–606, 1992.

16. West M, Rose MS, Sheldon A: Anxious attachment as a determinant of adult psy-

chopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:422–427, 1993.

17. Bender DS, Farber BA, Geller JD: Cluster B personality traits and attachment. Jour-

nal of American Academy of Psychoanalysis 29:551–563, 2001.

18. West M, Sheldon AER, Reiffer L: An approach to the delineation of adult attachment:

Scale development and reliability. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 175:738–

741, 1987.

19. Kernberg OF: A psychoanalytic classification of character pathology, in Essential

papers of character neurosis and treatment. Edited by Lax T. New York, New York,

University Press, 1989.

20. Pollak, J: Obsessive-compulsive personality: Theoretical and clinical perspectives

and recent research findings. Journal of Personality Disorders 1:248–262, 1987.

21. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, et al: Functional impairment in patients

with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

American Journal of Psychiatry 159:276–283, 2002.

22. Bender DS: The relationship of psychopathology and attachment to patients’ rep-

resentations of self, parents, and therapist in the early phase of psychodynamic

psychotherapy. (Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 1996). Dissertation Ab-

stracts International, vol. 57(5-B), November, 1996.

23. Fossati A, Donati D, Donini M, et al: Temperament, character, and attachment pat-

terns in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 15:390–402,

2001.

24. Feeney JA, Noller P, Hanrahan M: Assessing adult attachment, in Attachment in

Adults: Clinical and Developmental Perspectives. Edited by Sperling MB, Berman

WH. New York, Guilford Press, 1994.

80

PSYCHIATRY QUARTERLY

25. Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, et al: The Collaborative Longitudinal Personal-

ity Disorders Study: Development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. Journal

of Personality Disorders 14:300–315, 2000.

26. West M, Sheldon-Keller AE: Patterns of Relating. An Adult Attachment Perspective.

New York, Guilford Press, 1994.

27. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, et al: Diagnostic interview for DSM-IV

personality disorders. McLean Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical

School, 1996.

28. Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, et al: The collaborative longitudinal personality

disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders

14:291–299, 2000.

29. Aaronson CJ: Separation anxiety disorder in adults with borderline personality dis-

order (Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, 2001). Dissertation Abstracts In-

ternational, vol. 62(10-A), May, 2002.

30. Megeles FT, Swartz MO: Oscillations of attachment in borderline personality disor-

der. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1115–1120, 1989.

31. Bartholomew K, Shaver PR: Methods of assessing adult attachment: Do they con-

verge? Edited by Simpson JS, Rholes WS. Attachment theory and close relationships.

New York, Guilford Press, 25–45, 1998.

32. George C, Kaplan N, Main M: Attachment interview for adults. Unpublished

manuscript. University of California, Berkeley, 1996.

33. Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, Kennedy R, Mattoon G, Target M, et al: The relation of

attachment status, psychiatric classification, and response to psychotherapy. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:22–31, 1996.

34. Patrick P, Hobson RH, Castle D, Howard R, Maughn B: Personality disorder and the

mental representation of early social experience. Development and Psychopathology

6:375–388. 1994.

35. Stalker CA, Davies F: Attachment organization and adaptation in sexually-abused

women. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 40:234–240, 1995.

36. Dozier M, Tyrrell C: The role of attachment in therapeutic relationships. Edited

by Simpson JA, Rholes WS. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York,

Guilford Press, 221–248, 1998.

37. Dozier M: Attachment organization and treatment use for adults with serious psy-

chopathological disorders. Developmental Psychopathology 2:47–60, 1990.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

A Behavioral Genetic Study of the Overlap Between Personality and Parenting

A Behavioral Genetic Study of the Overlap Between Personality and Parenting

China the whys of the conflict between church and state Vatican Insider

Comparison of epidemiology, drug resistance machanism and virulence of Candida sp

An Empirical Comparison of C C Java Perl Python Rexx and Tcl for a Search String Processing Pro

Ebsco Garnefski Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety a comparison be

Rahmani, Lavasani (2011) The comparison of sensation seeking and five big factors of personality bet

Combined Therapy of Major Depression With Concomitant BPD Comparison of Interpersonal and Cognitive

Comparison of Human Language and Animal Communication

Comparison of the Russians and Bosnians

52 737 754 Relationship Between Microstructure and Mechanical Properts of a 5%Cr Hot Works

15 Multi annual variability of cloudiness and sunshine duration in Cracow between 1826 and 2005

A Comparison of Plato and Aristotle

A Comparison of the Status of Women in Classical Athens and E

Comparison of the U S Japan and German British Trade Rivalr

więcej podobnych podstron