11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100213

Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2003. 29:1–21

doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100213

Copyright c

° 2003 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

First published online as a Review in Advance on June 4, 2003

B

EYOND

R

ATIONAL

C

HOICE

T

HEORY

Raymond Boudon

University of Paris-Sorbonne, Universit´e Paris IV, ISHA, 96 boulevard Raspail,

75006 Paris, France; email: rboudon@noos.fr

Key Words beliefs, cognitivism, epistemology, methodological individualism,

values

■ Abstract Skepticism toward sociology has grown over recent years. The atten-

tion granted to rational choice theory (RCT) is, to a large extent, a reaction against

this situation. Without doubt, RCT is a productive instrument, but it fails signally in

explaining positive nontrivial beliefs as well as normative nonconsequential beliefs.

RCT’s failures are due to its move to use too narrow a definition of rationality. A

model can be developed that combines the advantages of the RCT (mainly providing

self-sufficient explanations), without falling victim to its shortcomings. This model is

implicitly used in classical and modern sociological works that are considered to be

illuminating and valid.

RCT: A SOLUTION TO THE CRISIS OF SOCIOLOGY?

It is evident that sociology has not achieved triumphs comparable to those

of the several older and more heavily supported sciences. A variety of in-

terpretations have been offered to explain the difference—most frequently,

that the growth of knowledge in the science of sociology is more random

than cumulative. The true situation appears to be that in some parts of the

discipline

. . .there has in fact taken place a slow but accelerating accumula-

tion of organized and tested knowledge. In some other fields the expansion

of the volume of literature has not appeared to have had this property. Critics

have attributed the slow pace to a variety of factors.

Encyclopaedia Britannica

The evaluation is fair. Some evaluators are more critical: Horowitz (1994) evokes

the “decomposition of sociology,” whereas Dahrendorf (1995) wonders whether

social science is withering away. To many sociologists the state of the discipline

is unsatisfactory.

One reason for the peculiar state of sociology is that, while its main objective

might be to explain puzzling phenomena, just like other scientific disciplines, in

fact it follows other directions. As I have tried to show elsewhere (Boudon &

Cherkaoui 1999, Boudon 2001b), sociology has always pursued cameral, critical,

0360-0572/03/0811-0001$14.00

1

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

2

BOUDON

and expressive directions as well as its cognitive approach. While some sociological

works aim at explaining social phenomena, others produce data for the benefit of

public policy, critical analyses of society for the benefit of social movements, or

emotional descriptions of society in the spirit of realistic novels or movies for the

benefit of the general public.

Another source of this particularity is that the notion of theory has a much more

uncertain meaning in sociology than it does in the other sciences. Thus, labeling

theory, a theory often referred to over recent decades, does nothing more than label

familiar phenomena. Much is written about social capital theory today. But social

capital is just a word for well-known mechanisms. As Alejandro Portes (1998)

writes, “Current enthusiasm for the concept of social capital

. . .is not likely to

abate soon (

. . .) However, . . .the set of processes encompassed by the concept are

not new and have been studied under other labels in the past. Calling them social

capital is, to a large extent, just a means of presenting them in a more appealing

conceptual garb.”

So, explanation is not always the main aim that sociologists seem to pursue,

and they sometimes give the impression of taking the idea of explanation down a

particular path that has nothing to do with the meaning of the word in other, more

solidly established sciences.

I see the attention currently granted to rational choice theory (RCT) as being,

to a large extent, a reaction against this state of affairs.

RATIONAL ACTION IS ITS OWN EXPLANATION

The motivations of RCT contenders are reminiscent of the discussions about

physics that took place in the Vienna Circle in the early twentieth century. Physical

theories, Carnap contended, include obscure notions (such as force); a truly valid

theory should be able to eliminate such notions. Once expressed in an entirely

explicit fashion, it should have the property of constituting, in principle, a set of

uncontroversial statements.

Rational Choice theorists, along the same line of argument, contend that ex-

plaining a phenomenon means making it the consequence of a set of statements

that should all be easily acceptable. They assume that a good sociological theory

is one that interprets any social phenomenon as the outcome of rational individ-

ual actions. As Hollis (1977) puts it, “rational action is its own explanation.” To

Coleman (1986, p. 1), “Rational actions of individuals have a unique attractiveness

as the basis for social theory. If an institution or a social process can be accounted

for in terms of the rational actions of individuals, then and only then can we say

that it has been ‘explained.’ The very concept of rational action is a conception

of action that is ‘understandable,’ action that we need ask no more questions

about.” To Becker (1996), “The extension of the utility-maximizing approach to

include endogenous preferences is remarkably useful in unifying a wide class of

behavior, including habitual, social and political behavior. I do not believe that any

alternative approach—be it founded on ‘cultural,’ ‘biological,’ or ‘psychological’

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

3

forces—comes close to providing comparable insights and explanatory power.”

Briefly, as soon as a social phenomenon can be explained as the outcome of ra-

tional individual actions, the explanation invites no further question: It contains

no black boxes. By contrast, irrational explanations necessarily introduce various

types of forces that raise even further questions as to whether they are real and, if

so, which is their nature.

As Becker rightly maintains, a theory appears less convincing as soon as it

evokes psychological forces (as when cognitive psychologists explain that peo-

ple tend to give a wrong answer to a statistical problem because of the existence

of some “cognitive bias”), biological forces [as when sociobiologists, e.g., Ruse

(1993), claim that moral feelings are an effect of biological evolution], or cultural

forces (as when sociologists claim that a given collective belief is the product

of socialization). In contrast to rational explanations, all these explanations raise

further questions: They include black boxes. Moreover, these explanations leave

the feeling that it is easy to elicit data that are incompatible and/or that the further

questions they raise have little chance of ever being answered. Thus, once we have

explained that most Romans in the early Roman Empire believed in the traditional

Roman polytheistic religion because they had been socialized to it, we are con-

fronted with the question as to why Roman civil servants and centurions, although

they too had been socialized to the old polytheistic religion, tended rather to be

attracted by monotheistic religions such as the Mithra cult and then Christianity

[Weber 1988 (1922)]. Moreover, the notion of socialization generates a black box

that seems hard to open: Nobody has yet been able to discover the mechanisms

behind socialization in the way, say, that the mechanisms behind digestion have

been explored and disentangled. I am not saying that socialization is a worthless

notion, nor that there are no such things as socialization effects, but merely that the

notion is descriptive rather than explanatory. It identifies and christens the various

correlations that can be observed between the way people have been raised and

educated and their beliefs and behavior; it does not explain them.

THE SYSTEM OF AXIOMS DEFINING RCT

RCT can be described by a set of postulates. I will present them in a general way

in order to transcend the variants of the theory. The first postulate, P1, states that

any social phenomenon is the effect of individual decisions, actions, attitudes,

etc., (individualism). A second postulate, P2, states that, in principle at least, an

action can be understood (understanding). As some actions can be understood

without being rational, a third postulate, P3, states that any action is caused by

reasons in the mind of individuals (rationality). A fourth postulate, P4, assumes

that these reasons derive from consideration by the actor of the consequences of

his or her actions as he or she sees them (consequentialism, instrumentalism). A

fifth postulate, P5, states that actors are concerned mainly with the consequences

to themselves of their own action (egoism). A sixth postulate, P6, maintains that

actors are able to distinguish the costs and benefits of alternative lines of action and

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

4

BOUDON

that they choose the line of action with the most favorable balance (maximization,

optimization).

The Importance of RCT

That RCT is the adequate framework of many successful explanations is incon-

trovertible. Why did the cold war last so many decades and why did it come to

a sudden conclusion? Why did the Soviet Union disappear? Why did the Soviet

Empire collapse suddenly in the early 1990s and not 20 years before or after? Such

general causes as low economic efficiency and the violation of human rights cannot

explain why it collapsed when it did or why it collapsed so abruptly. RCT can help

in answering these questions. The Western World and the Soviet Union became

involved in an arms race shortly after the end of World War II. Now, an arms

race presents a “prisoner’s dilemma” (PD) structure: If I (the U.S. government)

do not increase my military potential while the other party (the government of the

U.S.S.R.) does, I run a deadly risk. Thus, I have to increase military spending, even

though, as a government, I would prefer to spend less money on weapons and more

on, say, schools, hospitals, or welfare because these would be more appreciated

by the voters. In this situation, increasing one’s arsenal is a dominant strategy, al-

though its outcome is not optimal. The United States and the Soviet Union played

this game for decades and accumulated so many nuclear weapons that each could

destroy the planet several times over. This “foolish” outcome was the product

of “rational” strategies. The two superactors, the two governments, played their

dominant strategy and could not do any better than marginally reducing their ar-

senals through negotiations. The game stopped when the PD structure that had

characterized the decades-long interaction between the two powers was suddenly

destroyed. It was destroyed by the threat developed by then U.S. President Reagan

of reaching a new threshold in the arms race by developing the SDI project, the so-

called Star Wars. The initiative contained a certain measure of bluff. Technically,

the project was nowhere near ripe. Even today, the objective of devising defensive

missiles to intercept any missile launched against territories protected by the SDI

appears problematic at best. Economically, the project was so expensive that the

Soviet government saw that there was no way to follow without generating serious

internal economic problems. Hence, it did not follow and by not so doing, lost its

status of superpower, which had been uniquely grounded in its military strength.

Of course, there are other causes underlying the collapse of the Soviet Union, but

a fundamental one is that the PD game that had hitherto characterized relations

between the two superpowers was suddenly disrupted by Reagan’s move. Here,

an RCT approach helps identify one of the main causes of a major macroscopic

historical phenomenon. It provides an explanation as to why Gorbachev moved

in a new direction that would be fatal to the U.S.S.R., and why the U.S.S.R. col-

lapsed at precisely that point in time. In this case, we get an explanation without

black boxes as to why the “stupid” arms race was conducted, and why it sud-

denly stopped at a given point in time, leaving one of the protagonists in defeat.

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

5

Although the RCT game-theoretical approach uses a very simple representation of

the actors, it provides a convincing explanation. The explanation works because

the RCT axioms, though reductionist, are not unrealistic here: It is true that any

government has to be “egoist,” i.e., has to take care of its own national interests.

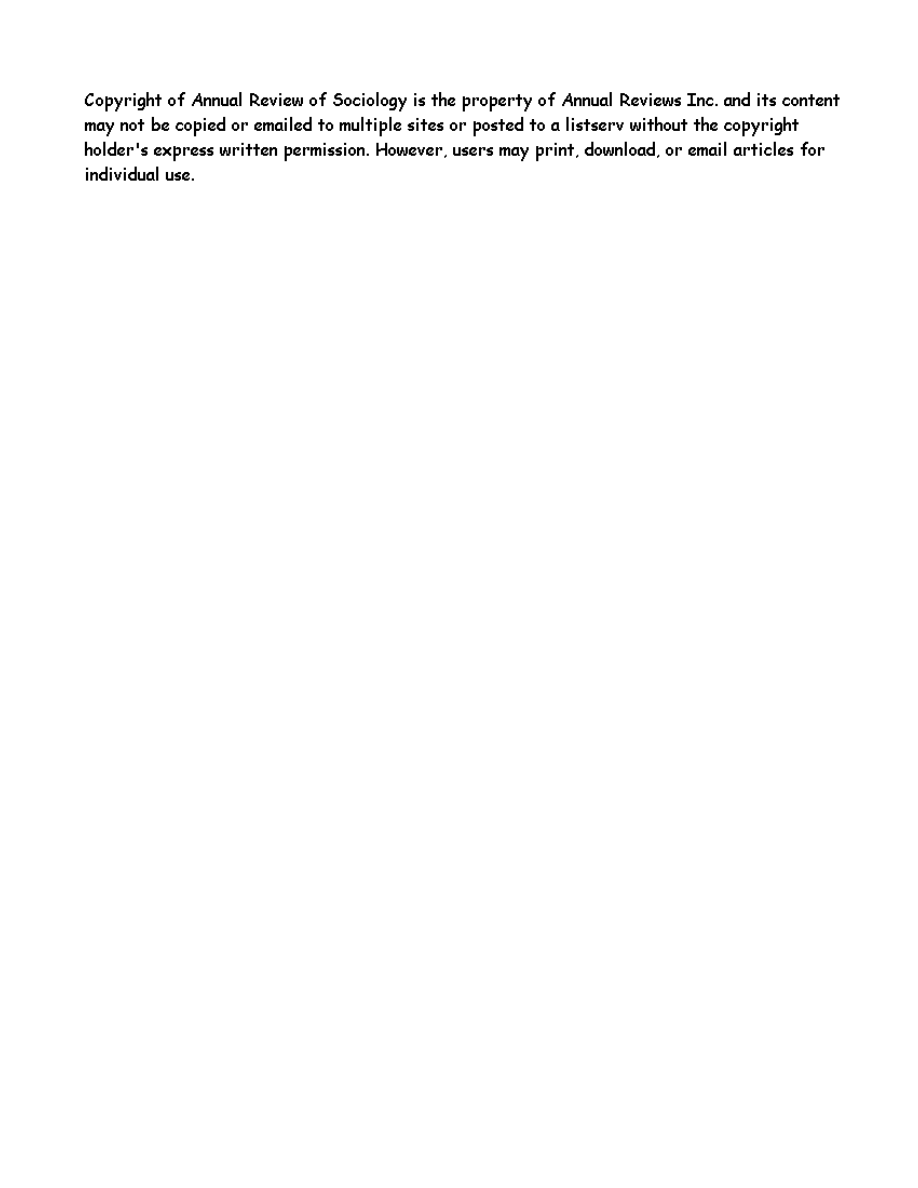

Consider as another example Tocqueville’s explanation of the stagnation of

French agriculture at the end of the eighteenth century [Tocqueville 1986 (1856)].

The “administrative centralization” characteristic of eighteenth century France

is the cause of the fact that there are many positions of civil servants available

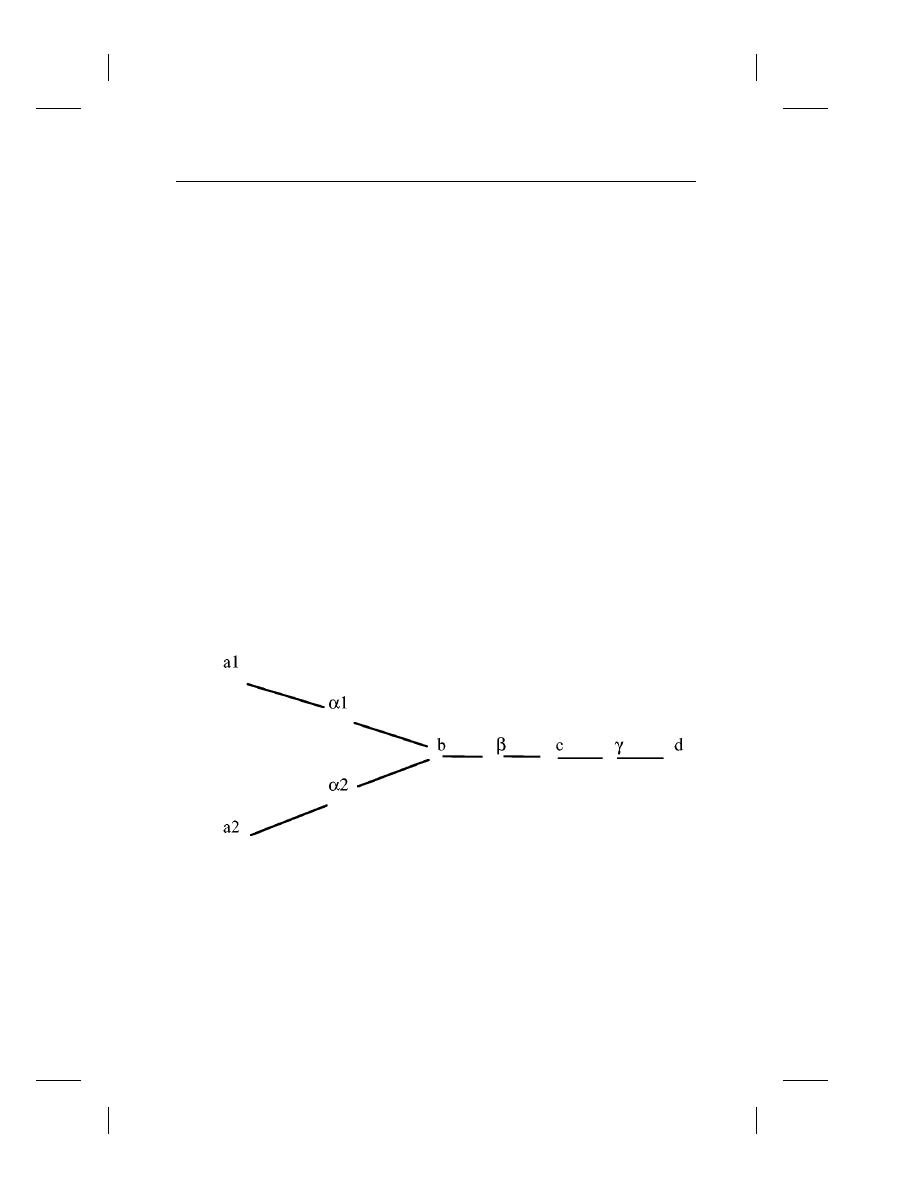

(statement a1) in France and that they are more prestigious than in England (a2); the

causes expressed by statements a1 and a2 provoke a rate of landlord absenteeism

much larger than in England (statement b); landlord absenteeism is the cause of a

low rate of innovation (c); the low rate of innovation is the cause of the stagnation

(d) (Figure 1).

To eliminate all black boxes from this explanation, one has to explain further

why a1 and a2 are causes of b, why b is the cause of c, and why c is the cause

of d. The answer takes the form of individualistic statements, namely, statements

explaining why the ideal-typical individuals belonging to relevant categories be-

haved the way they did. Why are a1 and a2 the causes of b? Because (

α1) landlords

see that they can easily buy a position of civil servant and that (

α2), by so doing,

they increase their power, prestige, and possibly income. In England, there are

fewer civil servants, and their positions are less accessible or rewarding, whereas

the gentleman-farmer is offered many opportunities for interesting social rewards

through local political life. Moreover, a good strategy for gentlemen farmers with

Figure 1

Tocqueville’s explanation of the stagnation of French agriculture at the end

of the eighteenth century. a1 (many positions of civil servants are available in France)

and a2 (being a civil servant is more prestigious in France than in England) cause b

(the rate of landlord absenteeism); b causes c (a low rate of innovation); c is the cause

of d (agricultural stagnation).

α1 (buying a position as a civil servant is easy) and α2

(increasing power and prestige) describes the French landlords’ reasons for leaving

their land;

β (landowners rent their land to farmers); γ (reasons for farmers to cultivate

the land in a noninnovative fashion).

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

6

BOUDON

national political ambitions to get elected to Westminster is to appear active and

innovative locally. Thus, French landlords have reasons (described by

α1 and α2)

to leave their land and serve the king that their English counterparts do not have

to the same degree. Such statements deal with the question as to why the relevant

category of landlords behaved the way they did. Why is b the cause of c? Why is

landlord absenteeism inimmical to innovation? Because landowners rent their land

to farmers (

β). Why is c the cause of d? Why do farmers not innovate? Because

they do not have the capacity to do so. Hence, they have reasons (

γ ) to cultivate the

land in a noninnovative fashion. The theory thus explains why the relevant social

categories, landlords and farmers, behaved the way they did. Tocqueville’s theory

gives the impression of being final; first, because its empirical statements appear

congruent with observational data, and second, because its statements (those de-

scribed by the Greek letters) on the reasons why farmers, landlords, etc., behaved

the way they did are evident, not in the logical but in the psychological sense.

It would be easy to list many modern works that owe their scientific value to

the fact that they use this RCT model. The works of economists and sociologists

such as Olson (1965), Oberschall (1973, 1994), Coleman (1990), Kuran (1995),

Hardin (1995), among others, come to mind, as well as historians such as Root

(1994) or political scientists such as Rothstein (2001). Without question, RCT has

indeed produced a substantial number of genuinely scientific contributions in the

past or more recently.

RCT: A POWERFUL OR A GENERAL THEORY?

Although RCT is a powerful theory, it appears powerless when confronted with

many phenomena. An impressive list can be compiled of all the familiar phenomena

it is unable to explain. This combination of success and failure is worth stressing

inasmuch as the social sciences community seems to be divided into two parties:

those who treat RCT as “a new Gospel” (Hoffman 2000) and those who do not

believe in this gospel. Furthermore, this mixture of success and failure raises the

important question as to its causes.

The Voting Paradox

The effect of a single vote on turnout for any election is so small, claims RCT, that

rational actors should actually refrain from voting: The costs of voting are always

higher than the benefits. As one of these voters, I should prefer resting, walking,

writing an article, or operating my vacuum cleaner to voting. Nevertheless, like

many people, I vote.

Many “solutions” to this paradox have been proposed, several of them even

brilliant, yet they fail to be really convincing. People like to vote, says a theory;

people would feel such strong regret if their ballot would have made the difference

that they vote even though they know that the probability of this event occurring is

infinitesimally small, says another (Ferejohn & Fiorina 1974). If I do not vote, I run

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

7

the risk of losing my reputation (Overbye 1995). Sometimes, RCT is made more

flexible by the notion of “cognitive frames.” Thus, Quattrone & Tversky (1987)

propose considering that voters vote because they see their motivation to vote as a

sign that their party is going to win, in the same way that the Calvinists, according

to Weber, are success-oriented because they think this attitude is a sign that they

are among the elected. Such a “frame” appears, however, not only as ad hoc, but

as introducing a black box. Schuessler (2000) starts from the idea that the voter

has an expressive rather than an instrumental interest in voting.

None of these “solutions” has been widely accepted. Some, like Ferejohn’s and

Fiorina’s, display a high intellectual virtuosity. However, they have not eliminated

the “paradox.”

Other Paradoxes

Other classical “paradoxes” beside voting can be mentioned. Allais’ “paradoxes”

show that, when they are proposed to bet in some types of lotteries, people do

not make choices in conformity with the principle of maximizing expected utility

(Allais & Hagen 1979, Hagen 1995). Frey (1997) has shown that people will

occasionally accept some disagreement more easily if there is no compensation

offered than when there is. As a case in point, a study conducted in Switzerland

and Germany showed that people accept the presence of nuclear waste on their

city’s land more easily when they are not offered compensation than when they

are.

Psychologists have devised many other experiments, for example, the classical

“ultimatum game” (Wilson 1993, pp. 62–63; Hoffman & Spitzer 1985), that resist

the RCT. Sociology also has produced many observations that can be read as

challenges to the RCT. Thus, the negative reaction of social subjects against some

given state of affairs has often nothing to do with the costs they are exposed to

by this particular state of affairs. On the other hand, actions can frequently be

observed where the benefit to the actor is zero or even negative. In White Collar,

C.W. Mills (1951) identified what could be called the “overreaction paradox.”

He describes women clerks working in a firm where they all sit in a large room

doing the same tasks, at the same kind of desk, in the same work environment.

Violent conflicts frequently break out over minor issues such as being seated closer

to a source of heat or light. An outside observer would normally consider such

conflicts as irrational because he or she would implicitly use RCT: Why such a

violent reaction? As the behavior of the women would appear to be strange in

terms of this model, he or she would turn to an irrational interpretation: childish

behavior. By so doing, he or she would be confessing that RCT cannot easily

explain the overreaction paradox observed by Mills.

Many observations would lead to the same conclusion: They can be inter-

preted satisfactorily in neither an irrational nor an RCT fashion. To mention just

a few of them, corruption in “normal” conditions—by which I mean the condi-

tions prevailing in most Western countries—is invisible to the common man or

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

8

BOUDON

woman; he or she does not see or feel its effects. He or she nevertheless con-

siders corruption to be unacceptable. Plagiarism is, in most instances, without

consequences. Indeed, in some circumstances it may even serve the interests of

the person being plagiarized since it attracts public attention. It is looked on with

approbrium, however. On some issues like the death penalty, I can have strong

opinions even though the likelihood that I might be personally affected is zero. In

other words, in many circumstances, people are guided by considerations that have

nothing to do with their own interests, nor with the consequences of their actions or

reactions.

On the whole, psychologists, sociologists, and economists have produced a

huge number of observations which cannot easily be explained within the RCT

frame. This situation raises two questions. Why does the RCT fail so often? Is

there a model that would satisfy the scientific ambition underlying RCT, namely

trying to provide explanations without black boxes, and at the same time get rid

of its defects?

The Sources of the Weaknesses of the RCT

It is not very hard to determine the reasons for RCT’s failures. The social phe-

nomena that RCT is incapable of accounting for share many features in common.

Three types of phenomena that slip RCT’s jurisdiction can be identified.

The first type includes phenomena characterized by the fact that actors base their

choices on noncommonplace beliefs. All behavior involves beliefs. To maximize

my chances of survival, in accordance with RCT, I will look both ways before

crossing the street. This behavior is dictated by a belief: I believe that if I don’t look

both ways I’m taking a serious chance. Here, the belief involved is commonplace,

not worth the analyst’s while to look at more closely. To account for other items of

behavior, however, it is crucial to explain the beliefs upon which they rest. Now,

RCT has nothing to tell us about beliefs, a weakness that is one of the main reasons

for its failures.

We can postulate that an actor holds a given belief because that belief is a conse-

quence of a theory he or she endorses. We can postulate furthermore that endorsing

the theory is a rational act. But here the rationality is cognitive, not instrumental:

It consists of preferring the theory that allows one to account for given phenomena

in the most satisfying possible way (in accordance with certain criteria). The actor

endorses a theory because he or she believes that the theory is true. Conversely,

it is precisely because RCT reduces rationality to instrumental rationality that it

runs into trouble when confronted with a whole variety of paradoxes.

Some sociologists have sought to reduce cognitive rationality to instrumental

reality. Radnitzky (1987) proposes that endorsing a scientific theory results from

a cost-benefit analysis. A scientist stops believing in a theory, writes Radnitzky,

as soon as the objections raised against it make defending it too “costly.” It is

indeed difficult to explain why a boat hull disappears from the horizon before the

mast, why the moon takes the shape of a crescent, why a navigator who maintains

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

9

constant direction returns to his starting point if we accept the theory that the earth

is flat. But what does it get us to replace the word difficult with the word costly?

Defending a given theory is more costly precisely because it is more difficult. We

must then explain why this is so; and from instrumental rationality we come back

to cognitive rationality.

RCT is powerless before a second category of phenomena: those characterized

by the fact that actors are following nonconsequentialist prescriptive beliefs. RCT

is comfortable with prescriptive beliefs as long as they are consequentialist. RCT

has no trouble explaining, for example, why most people believe that traffic lights

are a good thing: Despite the inconvenience they represent to me, I accept them

because they have consequences that I judge beneficial. Here, RCT effectively

accounts for both the belief and the attitudes and behavior inspired by that be-

lief. But RCT is mute when it comes to normative beliefs that cannot readily be

explained in consequentialist terms (Boudon 2001a). The subject in the classical

socio-psychological experiment “ultimatum game” acts against his or her own in-

terest. The voter votes, even though that vote will have virtually no effect on the

election result. The citizen vehemently disapproves of corruption even though not

affected personally. The plagiarist gives rise to a feeling of disdain, even when

no one is hurt and the plagiarized writer’s renown is actually enhanced. We point

an accusing finger at imposters, though their machinations create problems for no

one but themselves.

RCT is powerless before a third category of phenomena, that involving behavior

by individuals whom we cannot in any sensible way assume to be dictated by

self-interest. Regardless of whether Sophocles’ Antigone is being acted in Paris,

Beijing, or Algiers, the viewer of the tragedy unhesitatingly condemns Creon

and supports Antigone. The reason RCT cannot explain this universal reaction is

simple: The spectators’ interests are in no way affected by the matter before them.

We therefore cannot explain that reaction by any possible consequences on them

personally; nor by any consequences at all because there are no such consequences.

The spectator is not directly involved in the fate of Thebes; that fate belongs in the

past, and no one has any control over it anymore. Thus the consequentialism and

self-interest postulates are disqualified ipso facto.

Sociologists often find themselves confronted with this kind of phenomenon,

inasmuch as the social actors are regularly called upon to evaluate situations in

which they are not personally implicated at all. Most people are not personally

implicated in the death penalty; it “touches” neither them, their families, or friends.

This hardly means they cannot have a strong opinion on the issue. How can a set

of postulates that assumes them to be self-interested account for their reactions in

situations where their interests are not at stake and there is no chance that they

ever will be? These remarks lead to a crucial conclusion for the social sciences as

a whole; namely, RCT has little if anything to tell us about opinion phenomena,

which are a major social force and hence a crucial subject for sociologists.

In sum, RCT is disarmed when it comes to (a) phenomena involving non-

commonplace beliefs, (b) phenomena involving nonconsequentialist prescriptive

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

10

BOUDON

beliefs, and (c) phenomena that bring into play reactions that do not, by the very

nature of things, spring from any consideration based on self-interest.

OPENING THE RCT AXIOMS

These considerations suggest that axioms P4, P5, and P6 are welcome in some cases

but not in all. Reciprocally, the set of axioms P1, P2, and P3 appear to be more

general than the set P1 to P6. Now, P1 defines what is usually called methodologi-

cal individualism (MI), whereas the set of postulates made up of P1 and P2 defines

interpretive sociology (in Weber’s sense). As to the set P1 to P3, it defines a version

of interpretive sociology where actions are supposed to be rational in the sense that

they are grounded on reasons in the actor’s mind. I identify the paradigm defined by

postulates P1 to P3 as the cognitivist theory of action (CTA). It assumes that any col-

lective phenomenon is the effect of individual human actions (individualism); that,

in principle, provided the observer has sufficient information, the action of an ob-

served actor is always understandable (understanding); that the causes of the actor’s

action are the reasons for him or her to undertake it (rationality) (Boudon 1996).

RCT’s failures are due to its move to reduce all rationality to the instrumental

variety and neglect cognitive rationality as it applies not only to descriptive but

also to prescriptive problems (axiological rationality). Conversely, it is essential for

sociology as a discipline to be aware that many classical and modern sociological

studies owe their explanatory efficacy to the use of a cognitive version of MI, as

opposed to the instrumental one, primarily represented by RCT.

A BROADER NOTION OF RATIONALITY

CTA has the main advantage of RCT (i.e., offering explanations without black

boxes), but not its disadvantages, thanks to a broader notion of rationality that

is commonly accepted not only by philosophers but also by prominent social

scientists, such as Adam Smith indirectly or Max Weber directly.

I do not see why sociologists should not pay attention to distinctions repeat-

edly recognized by philosophers as well as by classical sociologists. Thus, Rescher

(1995, p. 26) states, “rationality is in its very nature teleological and ends-oriented,”

making immediately clear that “teleological” should not be made synonymous with

“instrumental” or “consequential.” He goes on, “Cognitive rationality is concerned

with achieving true beliefs. Evaluative rationality is concerned with making correct

evaluation. Practical rationality is concerned with the effective pursuit of appro-

priate objectives.” All these forms of rationality are goal-oriented, but the nature

of the goals can be diverse.

By creating his notion of “axiological rationality” or “evaluative rationality”

(Wertrationalit¨at) as complementary to, but essentially different from “instru-

mental rationality” (Zweckrationalit¨at), Max Weber clearly supported the the-

sis that rationality can be noninstrumental, in other words, that rationality is a

broader concept than instrumental rationality and a fortiori than the special form of

instrumental rationality (P1 to P6) postulated by RCT. As to Adam Smith’s notion

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

11

of the “impartial spectator,” it invites us to pay attention to the fact that on many

issues people may be unconcerned about their own interests, but can nevertheless

have strong opinions on these very same issues. Individual opinions can also be

inspired by impersonal reasons.

Theorists have recognized that instrumental rationality is only one form of

rationality. Moreover, many classical and modern compelling sociological analyses

implicitly (as with Tocqueville) or explicitly (as with Weber) use the generalized

conception of rationality that characterizes the CTA model. A few examples will

illustrate this point.

COGNITIVE RATIONALITY

Belief in Constructivism in France

An example, again taken from Tocqueville [1986 (1856)], illustrates how the rea-

sons for actors’ beliefs and behavior are currently “cognitive.” He wondered why

French intellectuals on the eve of the Revolution firmly believed in the idea of

Reason with a capital R, and why that notion had spread like wildfire among the

public. It was an enigmatic phenomenon, not to be seen at the time in Britain,

the United States, or the German states. And one with enormous macroscopic

consequences.

Tocqueville’s explanation consists in showing that Frenchmen at the end of

the eighteenth century had strong reasons to believe in Reason. In France at that

time, many traditional institutions seemed illegitimate. One was the idea that the

nobility was superior to the third estate. Nobles did not participate either in local

political affairs or economic life; rather they spent their time at Versailles. Those

who remained in the country held on all the more tightly to their privileges the

poorer they were. This explains why they were given the name of an unsightly little

bird of prey, the hobereau, a metaphor that spread quickly because it was perceived

to be so fitting. The following equation was established in many individual minds:

Tradition

= Dysfunction = Illegitimacy; and, by opposition, Reason = Progress =

Legitimacy. It was because this line of argument was latent in people’s minds that

the call by the philosophes to construct a society founded on Reason enjoyed such

immediate success.

The English, on the other hand, had good reasons not to believe in those ideas.

In England, the nobles played a crucial role: They ran local social, political, and

economic life. The superiority attributed to them in customary thinking and by

English institutions was perceived as functional and therefore legitimate. In

general, traditional English institutions were not perceived as dysfunctional.

Can False Beliefs Be Rational?

An objection to CTA is that action is often grounded on false ideas and therefore

it cannot be held to be rational. But to counter this received idea, false beliefs can

be grounded on strong reasons, and in that sense are rational, as familiar examples

show.

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

12

BOUDON

Pareto has said, with reason, that the history of science is the graveyard of all the

false ideas that once were endorsed under the authority of scientists. In other words,

science produces false ideas beside true ones. Now, nobody would accept the notion

that these false ideas are endorsed by scientists under the effect of irrational causes,

because their brains would have to have been wired in an inadequate fashion, or

because their minds would have to have been obscured by inadequate “cognitive

biases,” “frames,” “habitus,” by class interests or by affective causes—in other

words, by the “biological,” “psychological,” or “cultural forces” evoked by Becker

(1996). Scientists believe in statements that often turn out to be false because they

have strong reasons for believing in them, given the cognitive context.

The believers in phlogiston, in ether, or in the many other entities and mecha-

nisms that now appear purely imaginary to us had in their day, given the cognitive

context, strong reasons to believe in them. It was not immediately recognized as

important that when a piece of oxide of mercury is heated under an empty bell-

glass, the drop of water that appears on the bell’s wall should be taken into account:

That this drop of water appears regularly escaped immediate attention, nor was it

clearly perceived that this result contradicts phlogiston theory.

Why should the false beliefs produced by ordinary knowledge not be explained

in the same fashion as false scientific statements, namely based in the minds of

the social subjects on reasons that they perceive to be strong, given the cognitive

context in which they move?

I am not saying that false beliefs should always be explained in this fashion.

Even scientists can hold false beliefs through passion or other irrational causes.

What I am saying is that belief in false ideas can be caused by reasons in the mind

of the actors, and that they are often caused by reasons in situations of interest to

sociologists. Even though these reasons appear false to us, they may be perceived

to be right and strong by the actors themselves. To explain that what they perceive

as right is wrong, we do not have to assume that their minds are obscured by

some hypothetical mechanisms of the kind Marx (“false consciousness”), Freud

(“the unconscious”), L´evy-Bruhl (the mentalit´e primitive), and their many heirs

imagined, nor by the more prosaic “frames” evoked by RCT. In most cases, expla-

nations are more acceptable if we make the assumption that, given the cognitive

context in which they move, actors have strong reasons for believing in false

ideas.

I have produced elsewhere several examples showing that the rational explana-

tion of beliefs that we consider normal in the case of false scientific beliefs can also

be applied to ordinary knowledge. I have explored intensively instances of belief in

magic (Boudon 1998–2000) and false beliefs observed by cognitive psychologists

(Boudon 1996).

Here I limit myself to one example (inspired from Kahneman & Tversky, 1973)

from the second category. When psychiatrists are asked whether depression is a

cause of attempted suicide, they agree. When asked why, they answer that they have

frequently observed patients with both features: Many of their patients appeared

to be depressed and they have attempted suicide. Of course, the answer indicates

that the psychiatrists are using one piece of information in the contingency table

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

13

TABLE 1

A causal presumption can be derived from the single piece of information a if a is

much larger than exg/i

Suicide attempted

Suicide not attempted

Total

Depression symptoms

a

b

e

= a + b

No depression symptoms

c

d

f

= c + d

Total

g

= a + c

h

= b + d

i

= a + b + c + d

above (Table 1): Their argument runs, “a is high, hence depression is a cause of

attempted suicide.”

Now, any freshman in statistics would know that such an argument is wrong:

To conclude that there is a correlation between depression and suicide attempts,

one has to consider not one, but four pieces of information, not only a, but the

difference a/e

−c/f.

The psychiatrists’ answer shows that statistical intuition seems to follow rules

that have nothing to do with the valid rules of statistical inference. But it does not

prove that we should assume, in a L´evy-bruhlian fashion, that the physicians’ brains

are ill-wired. The physicians may very well have strong reasons for believing what

they do. Their answers may even suggest that statistical intuition is less deficient

than it seems. Suppose, for instance, that e in the table below equals 20%, in other

words that 20% of the patients of the physicians have depression symptoms, and

that g also equals 20% (20% of the patients have attempted suicide). Admittedly,

higher figures would be unrealistic. With these assumptions, in the case where the

percentage a of people presenting the two characters is greater than 4, the two

variables would be correlated, and thus causality could plausibly be presumed. A

physician who has seen, say, 10 people out of 100 presenting with the two characters

would have good reason to believe in the existence of a causal relationship between

the two features.

In this example, the belief of the physicians is not really false. In other instances,

the beliefs produced by cognitive psychology appear to be unambiguously false.

In most cases, however, I found that these beliefs could be explained as being

grounded in reasons perceived by the subjects as strong, which the observer can

easily understand.

Obviously, these reasons are not of the “benefit minus cost” type. They are rather

of the cognitive type. The aim pursued by the actor is not to maximize utility, but

rather credibility, to determine whether something is likely, true, etc. In addition

to its instrumental dimension, therefore, rationality has a cognitive dimension.

CAN RELIGIOUS BELIEFS BE ANALYZED AS RATIONAL?

Weber defined his “Verstehende sociology” as founded on MI: “Interpretive so-

ciology (as I conceive it) considers the isolated individual and his activity as its

basic unit, I would say its ‘atom’ ” (Weber 1922). In his view, sociology, like any

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

14

BOUDON

science, has to bring the macroscopic phenomena it is interested in down to their

microscopic causes. He believed that the cause of an actor’s actions and beliefs

consists in the meaning they had for that actor. And he rejected the idea of reducing

rationality to instrumental rationality. His whole sociology of religion is founded

on the methodological principle that the causes of religious beliefs and of the ac-

tions inspired by these beliefs reside in the meaning attributed to them by their

social subjects, and more exactly, that the reasons those subjects had for adher-

ing to those beliefs could not be reduced to RCT reasons. In other words, whereas

Weber’s “interpretive sociology” is, strictly speaking, defined by postulates P1–P2,

in practice, Weber uses the set of postulates P1 to P3: the CTA. It excludes the sup-

plementary postulates P4–P6 that define RCT. On this point Weber’s theoretical

texts are perfectly consistent with his empirical analyses.

Why were functionaries, military personnel, and politicians in Ancient Rome

and modern Prussia attracted to such cults as Mithraism and Freemasonry, each

characterized by a vision of disembodied transcendence subject to superior laws

and a conception of the community of the faithful as a group to be organized hier-

archically through initiation rituals? Because the articles of faith in such religions

were consistent with the social and political philosophy of these social categories.

Their members believed that a social system could function only if under the con-

trol of a legitimate central authority and that that authority must be moved by

impersonal rules. Their vision was of a functional, hierarchically organized soci-

ety, and that hierarchy had to be founded on abilities and skills to be determined

in accordance with formalized procedures—as was the case in the Roman and

Prussian states. Taken together, these principles for the political organization of

a “bureaucratic” state were, in their eyes, the reflection of a valid political phi-

losophy. And they perceived the initiation rituals of Mithraism, in the case of

the Roman officers and civil servants, or Freemasonry, in the case of Prussian

civil servants, as expressing those same principles in a metaphysical-religious

mode.

To cite another example, Weber explained that peasants had difficulty accepting

monotheism because the uncertainty characteristic of natural phenomena did not

seem to them to be at all compatible with the idea that the order of things could be

subject to a single will, a notion that in and of itself implied a minimal degree of

coherence and predictability.

Axiological Rationality

Weber’s “axiological rationality” is often understood as synonymous with “value

conformity.” I would propose rather that the expression identifies the case where

prescriptive beliefs are grounded in the mind of social actors on systems of rea-

sons perceived by them as strong, in exactly the same way as descriptive beliefs

(Boudon 2001a). This important intuition contained in Weber’s notion (though

implicitly rather than explicitly) was apparently already present in Adam Smith’s

mind.

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

15

An Illustration from Adam Smith

Although it is recognized that Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments does not rest

on RCT, it is sometimes held that his better-known work on the Wealth of Nations

does. The following example shows, however, that this is not the case. Even in this

book, which had a tremendous influence on economic theory, Smith does not use

RCT, but rather the cognitive version of MI: CTA.

Why, asks Smith, do we (i.e., eighteenth century Englishmen) consider it normal

that soldiers are paid less than miners? Smith’s methodology in his answer could

be applied to many similar questions today: Why do we feel it fair that such and

such occupation is paid more or less than another [Smith 1976 (1776), book 1,

chapter 10]? His answer is as follows:

(a) A salary is the retribution of a contribution. (b) To equal contributions

should correspond equal retributions. (c) Several components enter into the value

of a contribution: the investment required to produce a given type of competence,

the risks involved in the realization of the contribution, etc. (d ) The investment time

is comparable in the case of the miner and of the soldier. It takes about as much time

and effort to train a soldier as to produce a miner. The two jobs are characterized by

similar risks. Both include the risk of death. (e) Nonetheless, there are important

differences between the two types of jobs. ( f ) The soldier serves a central function

in society. This function preserves the identity and the very existence of the nation.

The miner fulfills an economic activity among others. He is not more central to

the society than, say, the textile worker. (g) Consequently, the death of the two

men has a different social meaning. The death of the miner will be identified as

an accident, the death of the soldier on the battlefield as a sacrifice. (h) Because

of this difference in the social meaning of their respective activities, the soldier

will be entitled to symbolic rewards, prestige, symbolic distinctions, including

funeral honors in case of death on the battlefield. (i) The miner is not entitled to

the same symbolic rewards. ( j) As the contribution of the two categories in terms

notably of risk and investment is the same, the equilibrium between contribution

and retribution can only be restored by making the salary of the mineworkers

higher. (k) This system of reasons is responsible for our feeling that the miner

should be paid a higher wage than the soldier.

First, Smith’s analysis does not use RCT. People do not believe what they

believe because this would maximize some difference between benefits and costs.

They have strong reasons for believing what they believe, but these reasons are not

of the cost-benefit type. They are not even of the consequential type. At no point

in the argument are the consequences that would eventually result from the miners

not being paid more than the soldiers evoked. Smith’s argument takes rather the

form of a deduction from principles. People have the feeling that it is fair to pay

higher salaries to miners than soldiers because the feeling is grounded on strong

reasons derived from strong principles, claims Smith. He does not say that these

reasons are explicitly present in everyone’s head, but clearly assumes that they are

in an intuitive fashion responsible for their beliefs. If miners were not paid more

than soldiers this would perhaps generate consequences (a strike by miners, say);

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

16

BOUDON

but these eventual consequences are not the reason why most people think the

miners should be paid more; people do not believe in this statement out of fear of

these eventual consequences.

Weber probably had such cases in mind when he introduced his distinction

between “instrumental” and “axiological” rationality.

A contemporary theorist of ethics proposes analyses of some of our moral

sentiments that are similar to Smith’s (Walzer 1983). Why, for instance, do we

consider conscription to be a legitimate recruitment method for soldiers but not

for miners, he asks? The answer again is that the function of the former is vital

whereas that of the latter is not. If conscription were to be applied to miners, it could

be applied to any and eventually to all kinds of occupations, hence it would lead

to a regime incompatible with the principles of democracy. In the same fashion,

it is readily accepted for soldiers to be used as garbage collectors in emergencies,

although it would be considered illegitimate to use them for such tasks in normal

situations. In all these examples, as in Smith’s example, collective moral feelings

are grounded on solid reasons, but not on reasons of the type considered in RCT.

I am not saying of course that a notion such as fairness cannot be affected by

contextual parameters. Thus, it has been shown that in the ultimatum game the

50/50 proposal is more frequent in societies where cooperation with one’s neigh-

bors is essential to current economic activity than in societies where competition

between neighbors prevails (Henrich et al. 2001). Such findings are not incompat-

ible with a rational interpretation of moral beliefs. They rather show that a system

of reasons is more easily evoked in one context than in another. In summary,

whereas contextual variation in moral beliefs is generally interpreted as validating

a cultural-irrational view of axiological feelings, the contextual-rational paradigm

illustrated by the previous examples appears to be more satisfactory: offering self-

sufficient explanations, i.e., explanations without black boxes.

The Validity of Reasons

Why does an actor consider a system of reasons to be good? Kant wrote that

looking for general criteria of truth amounts to trying to milk a billy goat. We

should recognize with Popper that there are no general criteria of truth, but also,

against Popper’s theory of science, that there are not even general criteria of falsity.

A theory is considered false only from the moment when an alternative theory

is found that is definitely better. Priestley had strong reasons for believing the

phlogiston theory was true. It became difficult to follow him only after Lavoisier

showed that all the phenomena that Priestley had explained in accordance with

his phlogiston could also be explained without it and with his own theory. In

other circumstances, the relative strength of alternative systems of reasons will

correspond to other types of criteria. In other words, we hold a theory to be true

or false because we have strong reasons of considering it as such, but there are

no general criteria of the strength of a system of reasons. More generally, let us

assume for a moment that we would have been able to identify the general criteria

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

17

of truth or rationality, then the next question would be: On which principles do

you ground the criteria, and so on ad infinitum.

To sum up, a system of reasons can be stronger or weaker than another and we

can explain why; but it cannot be said to be strong or weak in an absolute sense. Like

all evaluative notions, truth and rationality are comparative, not absolute notions.

A theory is never true or false, but truer or falser than another, if I may say so. We

consider it true from the moment when we find it hard to imagine a better theory.

The criteria used to decide that one system of reasons is stronger than another are

drawn from a huge reservoir and vary from one question to another.

Borrowing examples from the history of science has the advantage of clarifying

the discussion about the criteria of rationality. But the conclusion to be drawn from

the above example (that there are no general criteria of rationality) applies not only

to scientific, but to ordinary beliefs as well. And they apply not only to descriptive,

but also to prescriptive beliefs.

This latter point often meets some resistance because of a wrong interpretation

of Hume’s uncontroversial theorem that “no conclusion of the prescriptive type

can be drawn from a set of statements of the descriptive type.” But a prescriptive

or normative conclusion can be derived from a set of descriptive statements that

are all descriptive, except one, so that the real formulation of Hume’s theorem

should be “

. . .a set of statements all of the descriptive type.” I have developed this

point more fully in Boudon (2003). It is an essential point since it shows that the

gap between prescriptive and descriptive beliefs is not as wide as many people

think. It gives a clear meaning to Weber’s assertion that axiological rationality and

instrumental rationality are currently combined in social action, though they are

entirely distinct from one another. As implied by the CTA model, cognitive reasons

ground prescriptive as well as descriptive beliefs in the mind of individuals.

CONCLUSION

I have tried to make some crucial points: that social action generally depends on

beliefs; that as far as possible, beliefs, actions, and attitudes should be treated as

rational, or more precisely, as the effect of reasons perceived by social actors as

strong; and that reasons dealing with costs and benefits should not be given more

attention than they deserve. Rationality is one thing, expected utility another.

Why should we introduce this rationality postulate? Because social actors try

to act in congruence with strong reasons. This explains why their own behavior

is normally meaningful to them. In some cases, the context demands that these

reasons are of the “cost-benefit” type. In other cases, they are not: Even if we

accept that the notions of cost and benefit are interpreted in the most extensive

fashion, what are the costs and benefits to me of miners being better paid than

soldiers if I have no chance of ever becoming either a soldier or a miner?

On the whole, to get a satisfactory theory of rationality, one has to accept the

idea that rationality is not exclusively instrumental. In other words, the reasons

motivating an actor do not necessarily belong to the instrumental type. In the cases

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

18

BOUDON

of interest to sociologists, people’s actions are understandable because they are

moved by reasons. But these reasons can be of several types. Action can rest on

beliefs or not; the beliefs can be commonplace or not; they can be descriptive or

prescriptive. In all cases, the CTA model assumes that action has to be explained

by its meaning to the actor; it supposes hence that it is meaningful to the actor, or,

in other words, that it is grounded in the actor’s eyes on a system of reasons that

he or she perceives to be strong.

The CTA model is also more promising than the “program-based behavior”

model (PBBM) proposed by evolutionary epistemologists, notably Vanberg (2002),

for the latter model unavoidably generates black boxes. As the generalized ver-

sion of RCT obtained by supposing that actors are guided by “frames” loses the

main advantage of RCT itself (providing self-sufficient explanations), the PBBM

generates further questions of the type “where does the program come from? Why

do some actors endorse it while others do not?” Because the CTA model has an

answer to such questions, it is capable of generating self-sufficient explanations.

Considering RCT to be a special case of MI has the advantage of allowing the

main advantage of RCT (producing black-box-free explanations) to be extended

to a much wider set of social phenomena. But I must stress again that, if the CTA is

more general than RCT, it cannot be applied to all phenomena. Irrationality should

be given its right place. Traditional and affective actions also exist. Moreover, all

actions rest on the basis of instincts. I look to my right and left before crossing a

street because I want to stay alive. Reason is the servant of passions, as Hume said.

But passions need Reason: the magician’s customers are motivated by the passion

to survive, to see their crops grow; but nobody would consider that this passion in

itself is an adequate explanation for their magical beliefs.

The theory of rationality that I have sketched raises some important questions

that I will content myself with mentioning. Does the fact that behavior and beliefs

are normally inspired by strong reasons, even though these reasons might be false,

mean that any behavior or belief can be justified? Certainly not. Priestley believed

in phlogiston; Lavoisier did not. The two had strong reasons for believing what

they believed, and they both saw their reasons as valid. The latter was right, the

former wrong, however. The strength of reasons is thus a function of the context.

Today, our cognitive context is such that Priestley’s reasons are now weak for us

because we know that Lavoisier’s reasons were stronger. But Lavoisier’s reasons

had to be thought up and publicized before there could be any conclusion that he

was right. Then he became irreversibly right as opposed to Priestley. No relativism

follows from the contextuality of reasons.

Just as with cognitive reasons, axiological reasons can become stronger or

weaker over time, mainly because new reasons are expounded. When it was shown

that the abolition of capital punishment could not be held responsible for any sig-

nificant increase in crime rates, the argument “capital punishment is good because

it is an effective threat against crime” became weaker. This provoked a change—an

irreversible one—in our moral sensibility toward capital punishment. There are no

mechanically applicable general criteria of the strength of the reasons on which

either prescriptive or descriptive beliefs are grounded. Still, irreversible changes

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

19

in prescriptive as well as descriptive beliefs are frequently observed because in

the normal course of events, a system of reasons R’ eventually appeared to be

better than the system R, as in the descriptive case of Lavoisier and Priestley or

as in the prescriptive case of Montesquieu (who defended the idea that political

power would be more efficient if it is not concentrated) and Bodin (who could not

imagine that political power would be efficient without its being concentrated).

Montesquieu’s and Bodin’s beliefs as to what a good political organization should

be were grounded on reasons that the two of them perceived to be strong. Clearly,

Montesquieu was right.

Finally, the “paradoxes” mentioned above can be easily solved. They have

no RCT solution but do have an easy CTA solution: plagiarism and corruption

provoke a negative reaction not because of their consequences, but because they

are incompatible with systems of reasons that most people think of as strong.

The same is true of the other paradoxes, to which it is unnecessary to come back

in detail: People make their decisions because of a more or less conscious set

of arguments that they feel strong reason to believe in. Thus, in the “ultimatum

game,” they pick the 50/50 solution because they wonder which solution is fair, and

they do their best to define fairness in this case. They do not ask what is good for

themselves. People reject corruption though its effect on them is neutral because

they endorse a theory from which they conclude that it is unacceptable. In all these

cases, they display teleological behavior: They want to reach a goal. But only in

particular cases is the goal to maximize one’s interests or the satisfaction of one’s

preferences; the goal may also be finding the true or fair answer to a question.

Given these various goals, they are rational in the sense that they look for the best

or at least for a satisfactory system of reasons capable of grounding their answer.

The reader may be puzzled by the fact that I have used many examples from

classical sociology in this paper. By so doing I wanted to suggest a thesis that I

can formulate but not demonstrate in a short space: that from the beginning of our

discipline, the most solid sociological explanations implicitly use the CTA model

or, when adequate, its restricted version: RCT.

The Annual Review of Sociology is online at http://soc.annualreviews.org

LITERATURE CITED

Allais M, Hagen O, eds. 1979. Expected Utility

Hypotheses and the Allais Paradox: Contem-

porary Discussions of Decisions Under Un-

certainty With Allais’ Rejoinder. Dordrecht:

Reidel

Becker G. 1996. Accounting for Tastes. Cam-

bridge: Harvard Univ. Press

Boudon R. 1996. The ‘Rational Choice Model’:

a particular case of the ‘Cognitivist Model.’

Ration. Soc. 8(2):123–50

Boudon R. 1998–2000. ´

Etudes sur Les So-

ciologues Classiques. I and II. Paris:

PUF

Boudon R. 2001a. The Origin of Values. New

Brunswick: Transaction

Boudon R. 2001b. Sociology. International En-

cyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sci-

ences. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Boudon R. 2003. Raison, bonnes raisons. Paris:

PUF

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

20

BOUDON

Boudon R, Cherkaoui M. 1999. Central Cur-

rents in Social Theory. London: Sage

Coleman J. 1986. Individual Interests and Col-

lective Action: Selected Essays. Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press

Coleman J. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory.

Cambridge/London: Harvard Univ. Press

Dahrendorf R. 1995. Whither social sciences?

Econ. Soc. Res. Counc. Annu. Lect., 6th,

Swindon, UK

Ferejohn FJ, Fiorina M. 1974. The paradox of

not voting: a decision theoretic analysis. Am.

Polit. Sci. Rev. 68(2):525–36

Frey BS. 1997. Not Just for the Money: an Eco-

nomic Theory of Personal Motivation. Chel-

tenham: Edward Elgar

Hagen O. 1995. Risk in utility theory, in busi-

ness and in the world of fear and hope.

In Revolutionary Changes in Understand-

ing Man and Society, Scopes and Limits, ed.

J. G¨otschl, pp. 191–210. Dordrecht/London:

Kluwer

Hardin R. 1995. One for All: The Logic of

Group Conflict. Princeton: Princeton Univ.

Press

Henrich J, Boyd R, Bowles S, Camerer C, Fehr

E, et al. 2001. In search of Homo economi-

cus: behavioral experiments in 15 small-

scale societies. Am. Econ. Rev. 91(2):73–

78

Hoffman E, Spitzer ML. 1985. Entitlements,

rights and fairness. An experimental exam-

ination of subjects’ concepts of distributive

justice. J. Legal Stud. 14:259–97

Hoffman S. 2000. Le ‘choix rationnel’, nouvel

´evangile. Interview. Le Monde des D´ebats,

May 25

Hollis M. 1977. Models of Man: Philosophi-

cal Thoughts on Social Action. Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press

Horowitz I. 1994. The Decomposition of Soci-

ology. New York: Oxford Univ. Press

Kahneman D, Tversky A. 1973. Availability: a

heuristic for judging frequency and probabil-

ity. Cogn. Psychol. 5:207–32

Kuran T. 1995. Private Truths, Public Lies. The

Social Consequences of Preference Falsifi-

cation. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press

Mills CW. 1951. White Collar. The American

Middle Classes. New York: Oxford Univ.

Press

Oberschall A. 1973. Social Conflict and Social

Movements. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall

Oberschall A. 1994. R`egles, normes, morale:

´emergence et sanction. L’Ann´ee Sociol.

44:357–84

Olson M. 1965. The Logic of Collective Ac-

tion; Public Goods and the Theory of Groups.

Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press

Overbye E. 1995. Making a case for the rational,

self-regarding, ‘ethical’ voter

. . . and solving

the “paradox of not voting” in the process.

Eur. J. Polit. Res. 27:369–96

Portes A. 1998. Social capital: its origins and

applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev.

Sociol. 24:1–24

Quattrone GA, Tversky A. 1987. Self-decep-

tion and the voter’s illusion. In The Multi-

ple Self, ed. J Elster, pp. 35–58. Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press

Radnitzky G. 1987. La perspective ´economique

sur le progr`es scientifique: application en

philosophie de la science de l’analyse coˆut-

b´en´efice. Arch. Philos. 50:177–98

Rescher N. 1995. Satisfying Reason. Studies in

the Theory of Knowledge. Dordrecht: Kluwer

Rothstein B. 2001. The universal welfare state

as a social dilemma. Ration. Soc. 13(2):213–

33

Root HL. 1994. The Fountain of Privilege: Po-

litical Foundations of Economic Markets in

Old Regime France and England. Berkeley:

Univ. Calif. Press

Ruse M. 1993. Une d´efense de l’´ethique ´evolu-

tionniste. In Fondements Naturels de L’ ´

Ethi-

que, ed. JP Changeux, pp. 35–64. Paris: Odile

Jacob

Smith A. 1976 (1776). An Inquiry into the Na-

ture and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

Oxford: Clarendon

Schuessler AA. 2000. Expressive voting. Ra-

tion. Soc. 12(1):87–119

Tocqueville A de. 1986 (1856). L’Ancien R´eg-

ime et la R´evolution. In Tocqueville. Paris:

Laffont

Vanberg

VJ.

2002.

Rational

choice

vs.

11 Jun 2003

19:32

AR

AR190-SO29-01.tex

AR190-SO29-01.sgm

LaTeX2e(2002/01/18)

P1: IBC

BEYOND RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY

21

program-based behavior: alternative theoret-

ical approaches and their relevance for the

study of institutions. Ration. Soc. 14(1):7–54

Walzer M. 1983. Spheres of Justice. A Defence

of Pluralism and Equality. Oxford: Martin

Robertson

Weber M. 1922. Aufs¨atze zur Wissenschaft-

slehre. T¨ubingen: Mohr

Weber M. 1988 [1922]. Gesammelte Aufs¨atze

zur Religionssoziologie. T¨ubingen: Mohr

Wilson JQ. 1993. The Moral Sense. New York:

Free Press

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Boudon Limitations of rational choice theory

Hechter Sociological rational choice theory

Max Weber s Interpretive Sociology and Rational Choice Approach

Rational choice and the framing decisions

Theory of Varied Consumer Choice?haviour and Its Implicati

Is Addiction Rational Theory and Evidence

(ebook PDF)Shannon A Mathematical Theory Of Communication RXK2WIS2ZEJTDZ75G7VI3OC6ZO2P57GO3E27QNQ

Goertzel Theory

Optimistic Rationalist in Euripides Theseus, Jocasta, Teiresias

Hawking Theory Of Everything

Maslow (1943) Theory of Human Motivation

jones rationale for LT tx

Habermas, Jurgen The theory of communicative action Vol 1

Consilium rationis?llicae tezy strategiczne (notatka)

The Big?ng Theory

Psychology and Cognitive Science A H Maslow A Theory of Human Motivation

Pohlers Infinitary Proof Theory (1999)

więcej podobnych podstron