A Comparison of Linear Versus Non-Linear Models of Aversive

Self-Awareness, Dissociation, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

Among Young Adults

Michael F. Armey and Janis H. Crowther

Kent State University

Research has identified a significant increase in both the incidence and prevalence of non-suicidal

self-injury (NSSI). The present study sought to test both linear and non-linear cusp catastrophe models

by using aversive self-awareness, which was operationalized as a composite of aversive self-relevant

affect and cognitions, and dissociation as predictors of NSSI. The cusp catastrophe model evidenced a

better fit to the data, accounting for 6 times the variance (66%) of a linear model (9%–10%). These results

support models of NSSI implicating emotion regulation deficits and experiential avoidance in the

occurrence of NSSI and provide preliminary support for the use of cusp catastrophe models to study

certain types of low base rate psychopathology such as NSSI. These findings suggest novel approaches

to prevention and treatment of NSSI as well.

Keywords: non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), dissociation, cusp catastrophe, non-linear analysis

Recent research (Favazza, 1998; Sansone & Levitt, 2002) has

identified a significant increase in both the incidence and preva-

lence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). NSSI, defined as the

deliberate destruction or alteration of body tissue without con-

scious suicidal intent that results in significant tissue damage or

scarring, has been frequently identified in college-aged samples

(Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002). Consistent with research dem-

onstrating associations between emotional reactivity, poor emotion

regulation, and NSSI (e.g., Gratz, 2003; Gratz & Roemer, 2004,

Chapman, Gratz, and Brown (2006) have introduced a model of

NSSI, referred to as “deliberate self-harm” by these researchers,

which proposes that when an event occurs that triggers an un-

wanted emotional response, individuals engage in NSSI to escape

from this unpleasant affective state. While their model focuses

predominantly on NSSI as a behavior of “emotional avoidance,”

they recognize that it also may function to reduce other unpleasant

internal states that may be associated with unwanted emotions.

Thus, individuals may engage in NSSI to escape from the negative

self-appraisal of a personally relevant stimulus or event. Taken

together, an emerging body of literature has suggested that aver-

sive self-awareness, defined here as the experience of aversive and

self-relevant emotions and cognitions, often in response to nega-

tive events, predicts the occurrence/frequency of NSSI (e.g., Chap-

man et al., 2006). Thus, to the extent that NSSI reduces or

eliminates aversive self-awareness, it is negatively reinforced as a

means of managing emotionally charged experiences.

As defined here, aversive self-awareness is composed of both

affective and cognitive elements. Consistent with Watson, Clark,

and Tellegen’s (1988) tripartite model of affect, it seems likely that

aversive self-awareness is characterized by high levels of negative

affect (e.g., shame, sadness, fear, and hostility) and low levels of

positive affect. Negative affect might include not only sadness,

fear, and hostility, but also shame. Shame involves the assumption

that a negative situational outcome is caused by personality char-

acteristics of the individual that are open to criticism by others

(Tangney & Fischer, 1995) and thus may be rich with aversive

self-awareness and self-loathing. The cognitive component of

aversive self-awareness might be conceptualized in terms of

Nolen-Hoeksema’s depressive rumination construct. Nolen-

Hoeksema defines rumination as the process of “focusing pas-

sively and repetitively on one’s symptoms of distress and the

meaning of those symptoms without taking action to correct the

problems one identifies” (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998, p. 216). Rumi-

native self-awareness has been linked to the onset (Just & Alloy,

1997), exacerbation (Kuehner & Weber, 1999), and increased

chronicity of dysphoric affect and depressed mood (Nolen-

Hoeksema, 2000). Taken together, rumination may function to

exacerbate negative affect in individuals who engage in NSSI.

Psychological dissociation is another construct often examined

within the context of NSSI (Allen, 1995; Gratz et al., 2002;

Herpertz, 1995; Suyemoto, 1998). Psychological dissociation is

defined as the failure to associate thoughts, memories, emotions,

perception of the environment, and personal identity into an inte-

grated whole (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). While the

association between psychological dissociation and NSSI has been

attributed to the high rate of past traumatic life experiences in

individuals who engage in NSSI (Gratz, 2003; Suyemoto, 1998),

the function of psychological dissociation for these individuals is

unclear. For example, some individuals who engage in NSSI

describe dissociation as an experience that occurs before and is

terminated by self-injury (Briere & Gil, 1998), while others de-

scribe it as a consequence of the self-injurious act (Suyemoto,

Michael F. Armey and Janis H. Crowther, Department of Psychology,

Kent State University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michael

F. Armey, Department of Psychology, Kent State University, Kent, OH

44242. E-mail: marmey@kent.edu

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

Copyright 2008 by the American Psychological Association

2008, Vol. 76, No. 1, 9 –14

0022-006X/08/$12.00

DOI: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.9

9

1998). Thus, at this point, the nature of the associations among

aversive self-awareness, dissociation, and NSSI is unclear.

Catastrophe Theory

Previous research has explored the phenomenon of NSSI

through traditional statistical procedures that assume linear rela-

tionships between variables. Although these procedures have pro-

vided a wealth of information about correlates and predictors of

NSSI, it has been argued that complex human behaviors may, at

times, be poorly represented by linear models (Ehlers, 1995). In

contrast to traditional linear models, non-linear dynamic systems

theory (NDST) provides a framework for exploring and evaluating

complex systems and behaviors wherein dependent variables such

as NSSI might be better characterized as dichotomous, present or

absent, state measures (Barton, 1994). NDST seeks to identify the

factors that lead to a shift from one behavioral state (i.e., no

self-injury) to another behavioral state (i.e., self-injury).

Catastrophe theory (Thom, 1972/1975) is one application of

NDST that can be used to describe the factors contributing to the

development of NSSI. Catastrophe theory allows for the modeling

of large, “catastrophic,” non-linear changes in behavior that result

from small changes in continuous predictor variables. This type of

catastrophe model is referred to as the “cusp catastrophe” model

(Gilmore, 1981), since a sudden behavioral change is exhibited

once predictor variables cross the “cusp” threshold. In this study,

we would predict that as aversive self-awareness and dissociation

gradually change, individuals exhibit a sudden shift from a state

absent of self-injury to a self-injuring state.

A predicted behavior must possess five qualities to be consid-

ered within the context of catastrophe theory (Zeeman, 1976). The

first is bimodality, defined as the binary presence or absence of the

behavior of interest. With respect to NSSI, although individuals

may self-injure at different rates, they either engage in NSSI or

they do not. The second quality is inaccessibility, a situation

conceptually related to bimodality in which a particular level of

behavior does not exist as a stable state. Within the cusp catastro-

phe model, the combined influence of predictor variables forces an

intermediate level of a behavior to transform itself into one of two

distinct, and binary, outcomes, in this case, either the absence of

self-injury or infrequent self-injury versus chronic and severe

self-injury. Intermediate values are theoretically impossible or, at

the very least, highly improbable and unstable. Third, NSSI has the

quality of divergence, defined as the tendency for relatively small

changes in predictor variables, that is, aversive self-awareness and

dissociation, to be related to large, state changes in the dependent

variable, that is, NSSI. The fourth quality is hysteresis, or the

tendency for the variables responsible for the occurrence of NSSI

to not be responsible for a return to a state free of NSSI. Finally,

although the last quality, abrupt transitions, is somewhat poorly

defined in NDST (Gilmore, 1981), the theory proposes that the

shift from the absence to the presence of a given behavior, such as

NSSI, occurs with a high probability given a set of predictors.

The Present Study

The major goal of this research was to compare two approaches

to the investigation of aversive self-awareness and dissociation as

predictors of NSSI. Initially, a linear structural equation model was

evaluated to investigate the hypothesis that aversive self-

awareness—which was operationally defined by (a) high levels of

negative affect, including sadness, fear, hostility, and shame; (b)

low levels of positive affect; and (c) high levels of rumination—

and dissociation would predict NSSI, with dissociation mediating

this relationship. Given the non-normal distribution of NSSI, we

then explored the suitability of a non-linear cusp catastrophe

model by using aversive self-awareness, dissociation, and NSSI as

defined above. Here, we hypothesized that subtle changes in

aversive self-awareness and dissociation would result in a dramatic

change from the absence to the presence of NSSI. We hypothe-

sized that a non-linear cusp catastrophe model would better predict

the presence of NSSI than would a linear model since the non-

linear model incorporates more effectively the characteristics of

NSSI as a state variable rather than as a continuous variable. The

optimal statistical approach was determined by comparing the

amount of variance in scores on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inven-

tory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) explained by both linear and non-linear

models.

Method

Participants

Participants (n

⫽ 225) were male (36.4%) and female (63.6%)

undergraduates (M age

⫽ 19.5, SD ⫽ 3.11) enrolled in general

psychology at a large public university. The ethnic composition

was 85% Caucasian, 10% African American, 2% Asian or Asian

American, 1% Hispanic, 1% of mixed racial heritage, and 1% who

described themselves as Other.

Measures

The Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Mor-

row, 1991) is a 71-item self-report questionnaire with good con-

struct validity (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Mor-

row, 1991) that assesses an individual’s characteristic tendency to

engage in rumination, distraction, problem solving, or dangerous

behavior when experiencing dysphoria. In this study, the 22-item

Ruminative Responses Subscale (

␣ ⬎ .90; Nolen-Hoeksema &

Morrow, 1991) was scored.

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form

(PANAS–X; Watson & Clark, 1994) is a 60-item, self-report

questionnaire that assesses affective states. There is substantial

evidence for the internal consistency and construct validity of the

PANAS and PANAS–X (Watson & Clark, 1994; Watson et al.,

1988). For this study, the Positive Affect (Watson et al., 1988),

Hostility, Sadness, and Fear subscales (

␣s exceeding .82, Watson

& Clark, 1994; Watson et al., 1988) were used. Given our interest

in assessing shame as one component of aversive self-awareness,

a composite SHAME variable was computed by summing the

scores of the “ashamed” and “disgusted with self” items from the

PANAS–X.

The Dissociative Experiences Scale—II (Carlson & Putnam,

1993) consists of 28 questions related to the occurrence of disso-

ciative experiences in everyday life, independent of situations

involving drugs or alcohol. Split-half reliability for the original

Dissociative Experiences Scale is .96 for clinical samples, .71 for

10

ARMEY AND CROWTHER

non-clinical samples, and .95 in college students (Bernstein &

Putnam, 1986).

The DSHI (Gratz, 2001) is a17-item inventory assessing delib-

erate forms of NSSI. The forms of NSSI assessed by the DSHI

(e.g., carving words into the skin) were drawn from clinical ob-

servation and interviews with individuals engaging in these behav-

iors. Individuals respond to each of the 17 questions, reporting

whether or not they have ever engaged in the described behavior.

Scores are summed across items to produce an aggregate measure

of NSSI, with higher scores reflecting greater numbers of endorsed

NSSI behaviors. The DSHI has been shown to identify NSSI in

college samples (Gratz, 2001) and to be significantly associated

with conceptually relevant measures, such as the Difficulties in

Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Procedure

Following informed consent, participants completed the ques-

tionnaires in small groups. No participants who signed up for the

study refused to participate or chose to discontinue the study. At

the conclusion, participants were verbally debriefed regarding the

true purpose of the study and provided with a listing of campus and

community resources offering psychological counseling or therapy

in case they desired assistance in dealing with dysphoria or NSSI.

Results

Of the initial sample of 225 participants, only 3 were found to

have incomplete data on at least one subscale and were excluded

from subsequent analyses. Bivariate correlations, using a Bonfer-

roni correction of

␣⬘ ⫽ .002 (␣⬘ ⫽ ␣/28) to correct for family-wise

error, were calculated between study variables. Internal consis-

tency for all variables exceeded

␣ ⫽ .70, with the exception of the

two-item SHAME variable, where the two items correlated at r

⫽

.42. Table 1 summarizes descriptive and correlational data.

Consistent with the relatively low base rate of NSSI in the

general population, the DSHI demonstrated positive skew and

kurtosis. Because the DSHI serves as the primary dependent

variable, the positive skew (3.12) exhibited by the DSHI would

likely hinder the fit of a structural model. For this reason, DSHI

scores were logarithmically

1

transformed to minimize the im-

pact of normality violations on linear analyses (Kline, 1998).

Transformed DSHI scores were used for all subsequent linear

models, although skew remained somewhat elevated (1.72).

The remaining variables met the necessary assumptions for

these analyses.

Structural Equation Model and Model Fit

Initial model fit (EQS, Version 6.1; Multivariate Software

Inc., 2003) was assessed with a

2

procedure in which a

non-significant

2

statistic reflects an acceptable model fit

(Kline, 1998). Given the non-normal distribution of DSHI

1

There were no significant improvements in the skew or kurtosis of the

DSHI with the alternate use of either a square-root or natural log transfor-

mation.

Table 1

Bivariate Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations, and Cronbach’s Alpha

Measure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

45.65

1. DES–II

42.40

.97

18.52

2. RRS

.31

*

12.85

.95

31.41

3. PANAS–PA

⫺.16

⫺.35

*

7.52

.89

11.32

4. PANAS–Fear

.30

*

.47

*

⫺.28

*

4.14

.81

11.49

5. PANAS–Hostility

.36

*

.50

*

⫺.37

*

.63

*

4.26

.82

9.72

6. PANAS–Sadness

.29

*

.56

*

⫺.38

*

.62

*

.65

*

4.04

.84

3.41

7. SHAME

.28

*

.44

*

⫺.31

*

.66

*

.70

*

.63

*

1.56

.42

.69

8. DSHI

.17

.34

*

⫺.26

*

.12

.27

*

.19

.19

1.51

.71

Note.

Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha on the diagonal, with standard deviations in italics. DES–II

⫽ Dissociative Experiences

Scale—II; RRS

⫽ Ruminative Responses Subscale; PANAS ⫽ Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule, PA ⫽ Positive Affect Subscale, Fear ⫽ Fear

Subscale, Sadness

⫽ Sadness Subscale, Hostility ⫽ Positive Affect Hostility Subscale; SHAME ⫽ PANAS Composite Shame Variable; DSHI ⫽ Deliberate

Self-Harm Inventory.

*

p

⬍ .002.

11

SPECIAL SECTION; AVERSIVE SELF-AWARENESS, DISSOCIATION, AND SELF-INJURY

scores, the model was evaluated with fit indices derived from

robust variances, an estimation procedure which minimizes the

impact of non-normal data on model fit (Satorra & Bentler,

1994). Because the magnitude of this

2

statistic may be con-

flated with sample size and thus may overstate the poor fit of a

structural model (Bollen, 1989), a number of additional fit

indices were employed, such as the

2

/df statistic, whose ac-

ceptable value would be less than 3 (Kline, 1998). Additionally,

to minimize both Type I and Type II error rates, Hu and Bentler

(1999) recommended that a cutoff of 0.95 or above the com-

parative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) be combined with a

root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) “close to

0.06” (Hu & Bentler, 1999, p. 1) to assess the fit of observed

data to a given model.

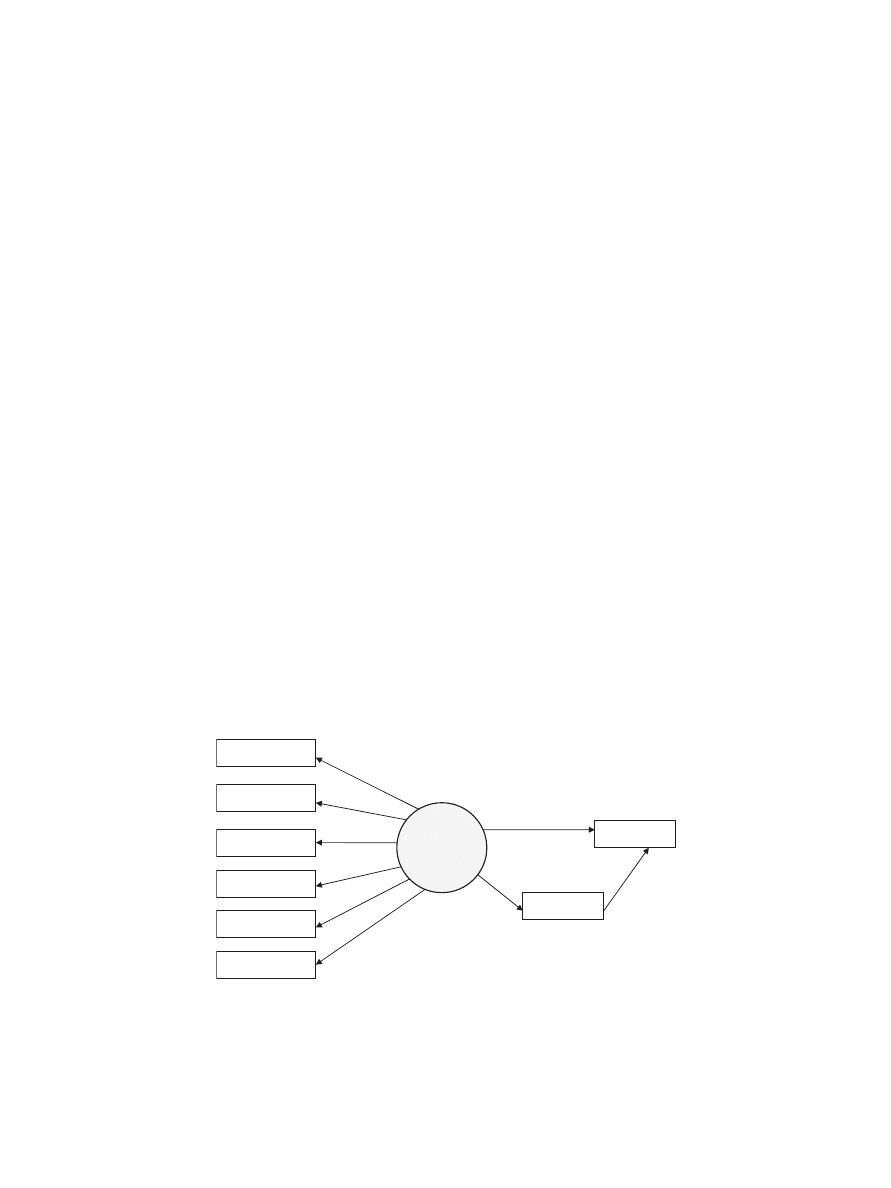

An over-identified structural model explored the relationship

between aversive self-awareness and dissociation with NSSI (Fig-

ure 1). Although the assumption of multivariate normality was

violated due to the positive skew of DSHI scores (Mardia’s coef-

ficient

⫽ 22.70), the structural model provided an acceptable fit to

the data, Satorra–Bentler

2

(19)

⫽ 34.42, p ⫽ .02 (

2

/df

⫽ 1.81;

CFI

⫽ 0.97; RMSEA ⫽ 0.06; 90% confidence interval (CI) ⫽

0.03, 0.09), but accounted for only 9% of the total variance in

DSHI scores. With respect to indirect effects (Baron & Kenny,

1986; Ullman, 2006), dissociation did not mediate the relationship

between aversive self-awareness and NSSI (standardized coeffi-

cient for indirect effect

⫽ .025, p ⬎ .05).

Cusp Catastrophe Model

The cusp catastrophe model was fit by using Hartelman’s

(1996) Cuspfit program, which permits the assignment of mul-

tiple independent predictor variables and a single dependent

criterion variable. Within the framework of cusp catastrophe

theory, variations in the predictor (or “control”) variables lead

to catastrophic changes in the dependent (or “state”) variable

(Gilmore, 1981). Consequently, although the dependent vari-

able is initially specified as a continuous variable, cusp catas-

trophe theory assumes that the variable is, essentially, bimod-

ally distributed and that the two modes represent distinct

behavioral states.

All variables were standardized to convert measures to a

common metric and to permit the creation of an aggregate

aversive self-awareness variable. Given the planned aggrega-

tion of predictor variables constituting aversive self-awareness

following standardization, the PANAS–Positive Affect was

multiplied by –1 to convert its negative association with the

proposed latent variable of aversive self-awareness to a positive

association. Finally, an aggregate aversive self-awareness vari-

able was computed by summing the standardized versions of the

Ruminative Responses Subscale, PANAS–Fear, PANAS–

Hostility, PANAS–Sadness, PANAS–Positive Affect, and

SHAME subscales. This aversive self-awareness composite

variable and the standardized version of the Dissociative Ex-

periences Scale—II were used as predictor variables for the

cusp catastrophe model. Standardized DSHI scores served as

the state variables.

Model fit for the cusp catastrophe model was assessed by using

a set of indices appropriate for non-normal data. Cuspfit fits linear,

logistic, and cusp models to the data. The appropriateness of a cusp

catastrophe model is evaluated on the basis of its comparison with

both linear and logistic models by using an R

2

value, the Akaike

information criterion (AIC), and the Bayesian information crite-

rion (BIC) statistics (Browne, 2000; Zucchini, 2000). The model

with the highest R

2

and the lowest AIC and BIC values is consid-

ered to provide the best fit to the data.

Results indicated that the cusp model (R

2

⫽ .66; AIC ⫽

415.50; BIC

⫽ 442.70) provided a superior fit to the data than

could either the logistic (R

2

⫽ .10; AIC ⫽ 616.00; BIC ⫽

633.00) or linear models (R

2

⫽ .10; AIC ⫽ 661.30; BIC ⫽

674.90). These results suggest that linear and logistic models

greatly underestimate the fit of the data to the model, account-

.76*

.06*

.39*

.27*

.84*

-.45*

.80*

.62*

DSHI

DES-II

RRS

PANAS Sadness

PANAS PA

PANAS Host.

PANAS Fear

.80*

Aversive

Self-

Awareness

Shame

Figure 1.

Structural model with dissociation mediating the association between aversive self-awareness and

non-suicidal self-injury. * indicates standardized path coefficient statistically significant at p

⬍ .05. RRS ⫽

Ruminative Responses Subscale; PANAS

⫽ Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule, Sadness ⫽ Sadness

Subscale, PA

⫽ Positive Affect Subscale, Host. ⫽ Hostility Subscale, Fear ⫽ Fear Subscale; Shame ⫽ PANAS

Composite SHAME Variable; DSHI

⫽ Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; DES–II ⫽ Dissociative Experiences

Scale—II.

12

ARMEY AND CROWTHER

ing for less than one-sixth of the variance explained by a cusp

catastrophe model.

2

Discussion

These results suggest the superiority of a cusp catastrophe

model over a traditional linear model when investigating aversive

self-awareness and dissociation as predictors of NSSI in an under-

graduate sample. Although NSSI has never been observed as a

normally distributed variable in community or college-aged sam-

ples, this is, to our knowledge, the first study to employ non-linear

modeling techniques to the prediction of self-injurious behavior.

Given that a cusp catastrophe model explains a greater proportion

of the variance in NSSI than does a more traditional linear model,

even when the latter used estimation procedures that minimize the

impact of non-normal data on model fit, non-linear modeling

techniques may represent a more appropriate match of the statis-

tical technique to the characteristics of the data in question. De-

spite such a benefit, non-linear modeling techniques have some

limitations. For example, structural equation modeling may be

used to test mediation and moderation, while cusp catastrophe

modeling cannot. Moreover, cusp models should be tested only

when the criterion variable of interest can be conceptualized as a

“state” variable, such as the presence or absence of NSSI, and

possesses the characteristics of bimodality, divergence, hysteresis,

inaccessibility, and abrupt transitions (Gilmore, 1981; Zeeman,

1976). Even so, future research should consider the use of non-

linear modeling to understand the development and occurrence of

other low base rate behaviors, such as suicide, or of diagnoses,

such as PTSD, in order to ultimately identify individuals who may

be at risk for such forms of psychopathology.

Consistent with past theory and research (e.g., Chapman et al.,

2006; Gratz, 2003), findings from both models suggest that indi-

viduals experiencing aversive self-awareness are more susceptible

to NSSI. Interestingly, the results of the structural equation model

may help refine our understanding of dissociation, as it was asso-

ciated with both aversive self-awareness and its constituent ele-

ments but was poorly associated with NSSI and did not emerge as

a mediator. While additional research is needed regarding the

nature and timing of the dissociative experience in relation to

NSSI, it may be that both dissociation and NSSI function to

regulate aversive experiences, but consistent with the experiential

avoidance model described by Chapman et al. (2006), dissociation

and NSSI interact to do so.

Of potential clinical significance is the application of the un-

derlying theoretical assumptions of catastrophe theory to our un-

derstanding of how psychopathology such as NSSI may develop.

Instead of conceptualizing the development of NSSI in terms of a

linear combination of predictors, it may be beneficial to examine

how small changes in multiple predictors interact to render an

individual at risk for engaging in NSSI. Possible future avenues of

clinical research include the development and refinement of inter-

ventions targeted at helping individuals at risk for engaging in

NSSI to remain below the cusp catastrophe threshold, in line with

many of the strategies integral to Dialectical Behavior Therapy

(Linehan, 1993). Moreover, assuming that hysteresis represents a

core feature of NSSI, we might consider the notion that changes in

the factors contributing to the occurrence of NSSI may not be

directly responsible for the termination of NSSI behaviors. Thus,

although increases in negative affect, rumination, and dissociation

may combine to trigger NSSI, the simple reduction of these factors

may be insufficient to provide complete relief from NSSI behav-

ior; this possibility may necessitate the development of additional

interventions, used to augment current treatments, that may not be

directly related to the risk factors involved in the development of

NSSI. However, given the preliminary nature of these findings,

additional research is needed to support these conclusions.

Despite these findings, several factors limit the generalizability

of these results. First, the present study utilized a sample of college

students with limited ethnic diversity. While dissociative experi-

ences (Bernstein & Putnam, 1986) and NSSI (Gratz et al., 2002)

are prevalent in college student samples, these findings should be

considered preliminary until they are replicated in a more diverse

clinical sample of individuals who engage in NSSI. Moreover, this

sample included both individuals who do and do not engage in

NSSI; clearly, further investigations of this statistical model are

warranted in clinical samples in order to more fully understand the

potential clinical utility of this theoretical approach. However, the

observed lifetime prevalence rate of NSSI in our sample (30%) is

comparable with the rates of other studies (37%) using the DSHI

in samples of college students (Gratz, 2006). Second, data collec-

tion relied on a retrospective, cross-sectional, methodology that is

unable to assess changes over time inherent to the underlying

catastrophe theory. Consequently, although the present study ex-

amines a potentially useful statistical technique for the analysis of

these NSSI data, these findings would be significantly strength-

ened through replication in a study using a longitudinal design,

such as ecological momentary assessment. Third, the data were

aggregated prior to the cusp analysis, which may limit our ability

to directly relate those findings to the structural-equation-modeling

(SEM) model; however, it should also be noted that the linear SEM

model fit using EQS accounted for a similar amount of variance

(9%) as did the linear model fit through Cuspfit (10%). While this

study represents an important step toward understanding the nature

of the associations between aversive self-awareness, dissociation,

and NSSI within the context of both linear and non-linear models,

future studies of NSSI would benefit from research methodologies

assessing individuals’ in vivo experiences of emotion, cognition,

and NSSI.

2

Although the linear model in the SEM analysis and the linear model in

the Cuspfit analysis accounted for approximately the same percentage of

variance in DSHI scores (9% and 10%, respectively), it is possible that the

different ways that the data were handled (the Cuspfit analysis used

standardized scores, while the SEM analysis did not) may have impacted

the findings. Thus, we reran the SEM analysis by using standardized scores

on all measures. This reanalysis yielded virtually identical findings,

Satorra–Bentler

2

(19)

⫽ 33.26, p ⫽ .02 (

2

/df

⫽ 1.75; CFI ⫽ .97;

RMSEA

⫽ .06; 90% CI ⫽ .02, .09). This model accounted for 8% of the

variance.

References

Allen, C. (1995). Helping with deliberate self-harm: Some practical guide-

lines. Journal of Mental Health, 4, 243–250.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical man-

ual of mental disorders. (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC:

Author.

13

SPECIAL SECTION; AVERSIVE SELF-AWARENESS, DISSOCIATION, AND SELF-INJURY

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable

distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and

statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

51, 1173–1182.

Barton, S. (1994). Chaos, self-organization, and psychology. American

Psychologist, 49, 5–14.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psy-

chological Bulletin, 107, 238 –246.

Bernstein, E., & Putnam, F. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity

of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174,

727–735.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New

York: Wiley.

Briere, J., & Gil, E. (1998). Self-mutilation in clinical and general popu-

lation samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal

of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 609 – 620.

Browne, M. W. (2000). Cross-validation methods. Journal of Mathemati-

cal Psychology, 44, 108 –132.

Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, W. (1993). An update on the Dissociative

Experiences Scale. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disor-

ders, 6, 16 –27.

Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle

of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behavior

Research and Therapy, 44, 371–394.

Ehlers, C. L. (1995). Chaos and complexity: Can it help us understand

mood and behavior? Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 960 –964.

Favazza, A. R. (1998). The coming of age of self-mutilation. Journal of

Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 259 –268.

Gilmore, R. (1981). Catastrophe theory for scientists and engineers. New

York: Wiley.

Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data

on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology &

Behavioral Assessment, 23, 253–263.

Gratz, K. L. (2003). Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm:

An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psychology: Science and

Practice, 10, 192–205.

Gratz, K. L. (2006). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among female

college students: The role and interaction of childhood maltreatment,

emotional inexpressivity, and affect intensity/reactivity. American Jour-

nal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 238 –250.

Gratz, K. L., Conrad, S. D., & Roemer, L. (2002). Risk factors for

deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Or-

thopsychiatry, 72, 128 –140.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emo-

tion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and

initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation scale. Journal

of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54.

Hartelman, P. (1996). Cuspfit program. [Computer software]. Retrieved

October 24, 2007, from http://users.fmg.uva.nl/hvandermaas/cata.html

Herpertz, S. (1995). Self-injurious behavior: Psychopathological and noso-

logical characteristics in subtypes of self-injurers. Acta Psychiatrica

Scandinavica, 91, 57– 68.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance

structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struc-

tural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Just, N., & Alloy, L. B. (1997). The response styles theory of depression:

Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

106, 221–229.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation mod-

eling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kuehner, C., & Weber, I. (1999). Responses to depression in unipolar

depressed patients: An investigation of Nolen-Hoeksema’s response

styles theory. Psychological Medicine, 29, 1323–1333.

Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline person-

ality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Multivariate Software Inc. (1998). EQS 6.1 [Computer software]. Encino,

CA: Author.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1998). The other end of the continuum: The costs of

rumination. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 216 –219.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). Further evidence for the role of psychosocial

factors in depression chronicity. Clinical Psychology: Science and Prac-

tice, 7, 224 –227.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depres-

sion and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The

1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psy-

chology, 61, 115–121.

Sansone, R. A., & Levitt, J. L. (2002). Self-harm behaviors among those

with eating disorders: An overview. Eating Disorders: The Journal of

Treatment and Prevention, 10, 205–213.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and

standard errors on covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C. C.

Clogg (Eds.), Latent variable analysis (pp. 399 – 419). Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Suyemoto, K. L. (1998). The functions of self-mutilation. Clinical Psy-

chology Review, 18, 531–554.

Tangney, J. P., & Fischer, K. W. (1995). Self-conscious emotions: The

psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride. New York:

Guilford Press.

Thom, R. (1972/1975). Stabilite´ structurelle et morphogene`se [Structural

stability and morphogenesis] (H. Fowler, Trans.). Reading, England:

Benjamin.

Ullman, J. B. (2006). Structural equation modeling. In B. G. Tabachnick &

L. S. Fidell (Eds.), Using multivariate statistics (pp. 607– 675). Boston:

Pearson.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. (1994). The PANAS–X: Manual for the positive

and negative affect schedule—Expanded form. Unpublished manuscript.

Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation

of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Zeeman, E. C. (1976). Catastrophe theory. Scientific American, 23, 65– 83.

Zucchini, W. (2000). An introduction to model selection. Journal of

Mathematical Psychology, 44, 41– 61.

Received January 31, 2007

Revision received September 5, 2007

Accepted September 11, 2007

䡲

14

ARMEY AND CROWTHER

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Retrospective Analysis of Social Factors and Nonsuicidal Self Injury Among Young Adults

COMPARISON OF ATTACHMENT STYLES between bpd and ocd

Comparison of epidemiology, drug resistance machanism and virulence of Candida sp

An Empirical Comparison of C C Java Perl Python Rexx and Tcl for a Search String Processing Pro

Identifying Clinically Distinct Subgroups of Self Injurers Among Young

Crisci, Morrone, A Comparison of Biogeographic Models (1992)

An Empirical Comparison of Discretization Models

comparison of PRINCE2 against PMBOK

Comparison of Human Language and Animal Communication

A Comparison of two Poems?out Soldiers Leaving Britain

A Comparison of the Fight Scene in?t 3 of Shakespeare's Pl (2)

Comparison of the Russians and Bosnians

43 597 609 Comparison of Thermal Fatique Behaviour of Plasma Nitriding

Comparision of vp;atile composition of cooperage oak wood

1 3 16 Comparison of Different Characteristics of Modern Hot Work Tool Steels

więcej podobnych podstron