Under the city centre, the ancient harbour.

Tyre and Sidon: heritages to preserve

Nick Marriner, Christophe Morhange *

CEREGE-CNRS UMR 6635, University of Aix-Marseille, 29, avenue R. Schuman, F-13621 Aix-en-Provence, France

Received 31 December 2004; accepted 3 February 2005

Abstract

The exact location and chronology of the ancient harbours of Phoenicia’s two most important city-states, Tyre and Sidon, is a longstanding

debate. New geoarchaeological research reveals that the early ports actually lie beneath the modern urban centres. During the Bronze Age,

Tyre and Sidon were characterised by semi-open marine coves. After the first millennium BC, our bio-sedimentological data attest to early

artificial harbour infrastructure, before the later apogees of the Roman and Byzantine periods. Post-1000 AD, silting-up and coastal progra-

dation led to burial of the ancient basins, lost until now, beneath the city centres. The outstanding preservation properties of such fine-grained

sedimentary contexts, coupled with the presence of the water table, means these two Levantine harbours are exceptionally preserved. This

work has far-reaching implications for our understanding of Phoenician maritime archaeology and calls for the protection of these unique

cultural heritages.

© 2005 Elsevier SAS. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Geoarchaeology; Ancient harbour; Coastal heritage; Antiquity; Holocene; Lebanon; Phoenicia

1. Introduction

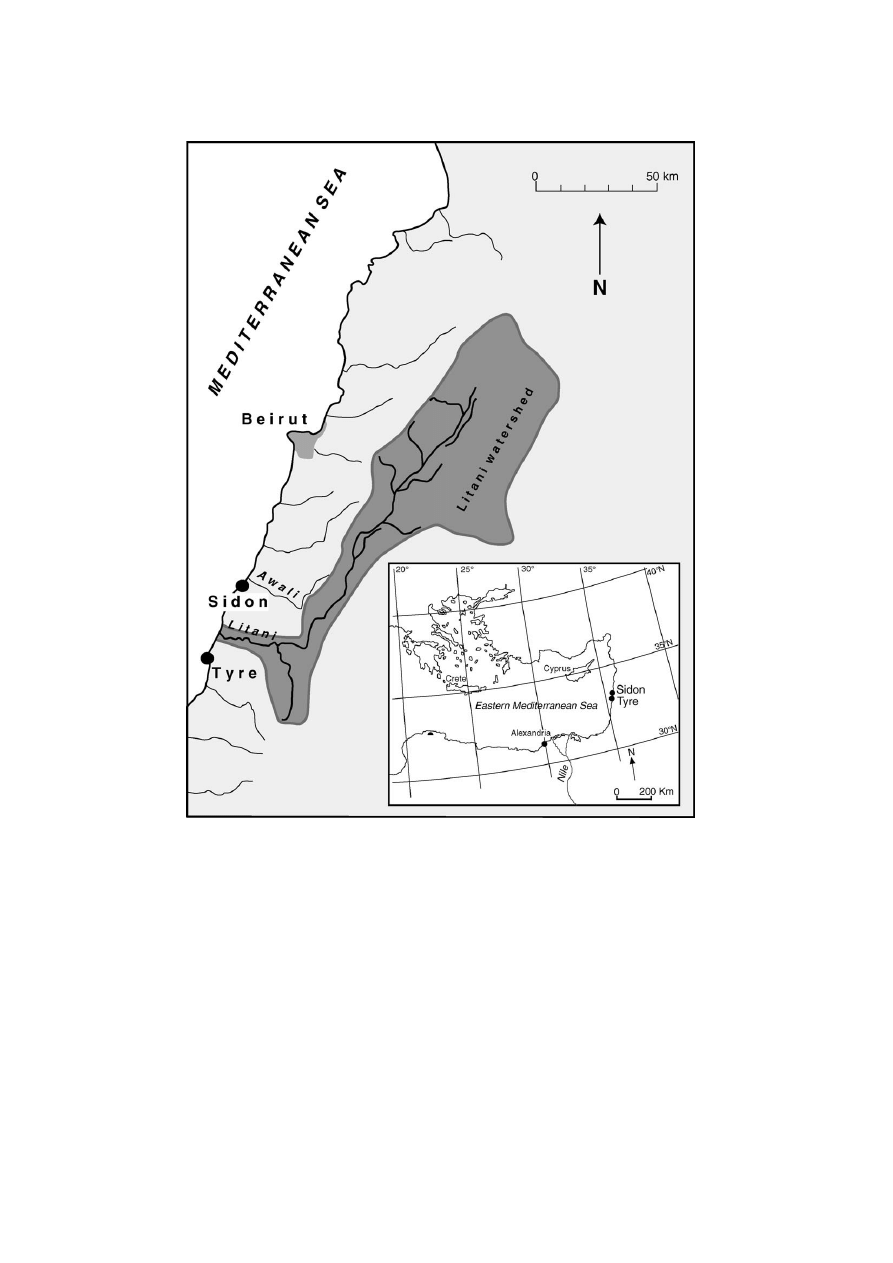

Since 1998, a multi-disciplinary team under the auspice of

the British Museum, UNESCO World Heritage and the

AIST/LBFNM has been undertaking research into the palae-

oenvironmental history of Tyre and Sidon, two famous ancient

cities of the Levantine coast (present-day Lebanon (

These celebrated sites have long attracted the attention of early

travellers and scholars, but paradoxically very little is known

about their ancient harbours

Geoarchaeological study of ancient Mediterranean har-

bours is a relatively new area of inquiry that has been devel-

oped and refined over the past decade

. In the absence

of often expensive and technically difficult marine and coastal

excavations, the multi-disciplinary study of sedimentary har-

bour sequences is important for a number of reasons: (1) it

enables the chronology of ancient harbours to be established

(2), it facilitates the spatial localisation of the basins and the

reconstruction of their palaeogeographies, and (3) it is an inno-

vative archaeological tool for the protection and manage-

ment of very sensitive coastal sites under urban pressure.

We have applied high-resolution palaeoenvironmental

proxy techniques to the cities’ harbour environments, drill-

ing 25 bore-holes in Tyre and 15 in Sidon. Laboratory studies

of the sediment cores have enabled us to rediscover the two

cities’ ancient harbours and reconstruct the former dimen-

sions of the basins.

Natural down-wind basins are located on the northern sides

of both the Tyrian and Sidonian promontories

. These are

the most attractive locations for the berthing of boats. Cores

have been essential in precisely reconstructing the palaeoen-

vironmental evolution, the maximum extension and shore-

line mobility of the ancient basins. Here we discuss the exact

spatial morphology and limits of the northern basins, and their

potential for future archaeological excavations.

2. Palaeogeography of Tyre’s ancient northern harbour

Since 7000 years, the Lebanese coast has been character-

ised by relative sea-level stability

except for small loca-

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: nick.marriner@wanadoo.fr (N. Marriner),

morhange@cerege.fr (C. Morhange).

Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

http://france.elsevier.com/direct/CULHER/

1296-2074/$ - see front matter © 2005 Elsevier SAS. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.culher.2005.02.002

lised tectonic movements, as, for example, in the Tyre sector

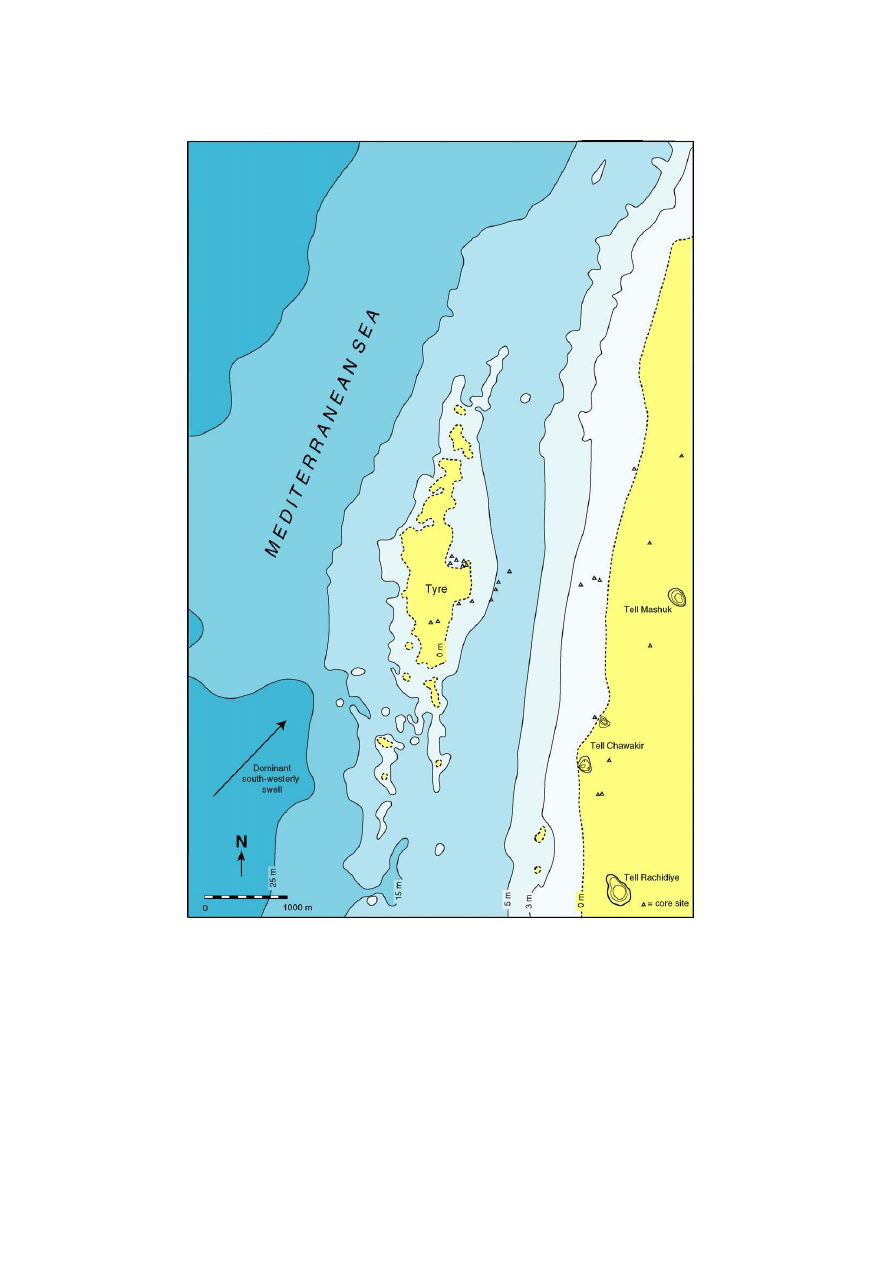

. In Tyre, ca. 7000 years ago, relative sea-level was around

–6 m below present and the ancient shoreline of the island

was therefore very different to nowadays. Quaternary aeo-

lianite ridges were exposed, protecting the later Bronze Age

harbour cove

). This natural protection explains

the location of the city and its harbour on the northern lee-

ward façade of the island. Bio-sedimentological proxies dem-

onstrate the presence of a relatively shallow, low-energy envi-

ronment, newly transgressed by the end of the post-glacial

sea-level rise. The palaeo-bathymetry indicates that the sub-

aerial extension of the sandstone ridge, forming Tyre island,

had a much greater northerly and southerly extent, sheltering

the leeward cove from the dominant onshore south-westerly

winds and swell.

Around 3500 BP, when the Middle Bronze Age (MBA)

harbour was founded, the environment was relatively less pro-

tected because of the marine transgression and erosion of these

natural sandstone ridges (

). The litho- and biostratigra-

phies indicate the beginning of strong anthropogenic modifi-

cation of the natural environment

. Geochemical analy-

ses of the harbour sediments attest to human occupation and

palaeo-metallurgy from the MBA onwards. From this period,

the harbour shoreline was characterised by rapid prograda-

tion linked to a positive sedimentary budget.

During the Roman and the Byzantine periods, the basin

was characterised by very rapid silting. The environment was

marked by a low energy, fine muddy-sand facies, indicative

of a sheltered harbour existing up until ca. 1000 AD. During

the Byzantine period, proxies suggest the presence of a shel-

tered leaky lagoon, concomitant with a very well-protected

harbour during the harbour’s apogee. This was the case in

other Phoenician harbours, such as Beirut and Akko.

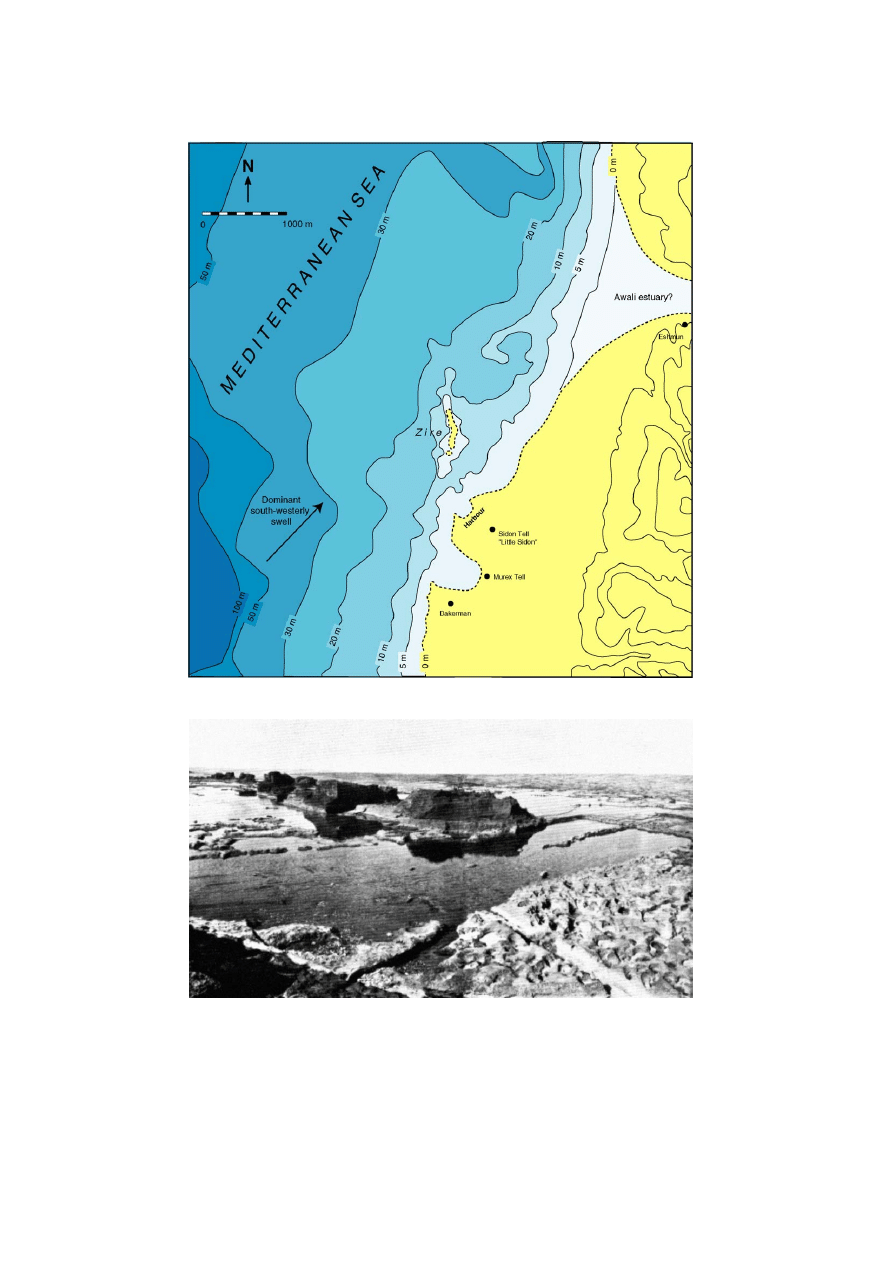

Fig. 1

.

Location of the studied sites.

184

N. Marriner, C. Morhange / Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

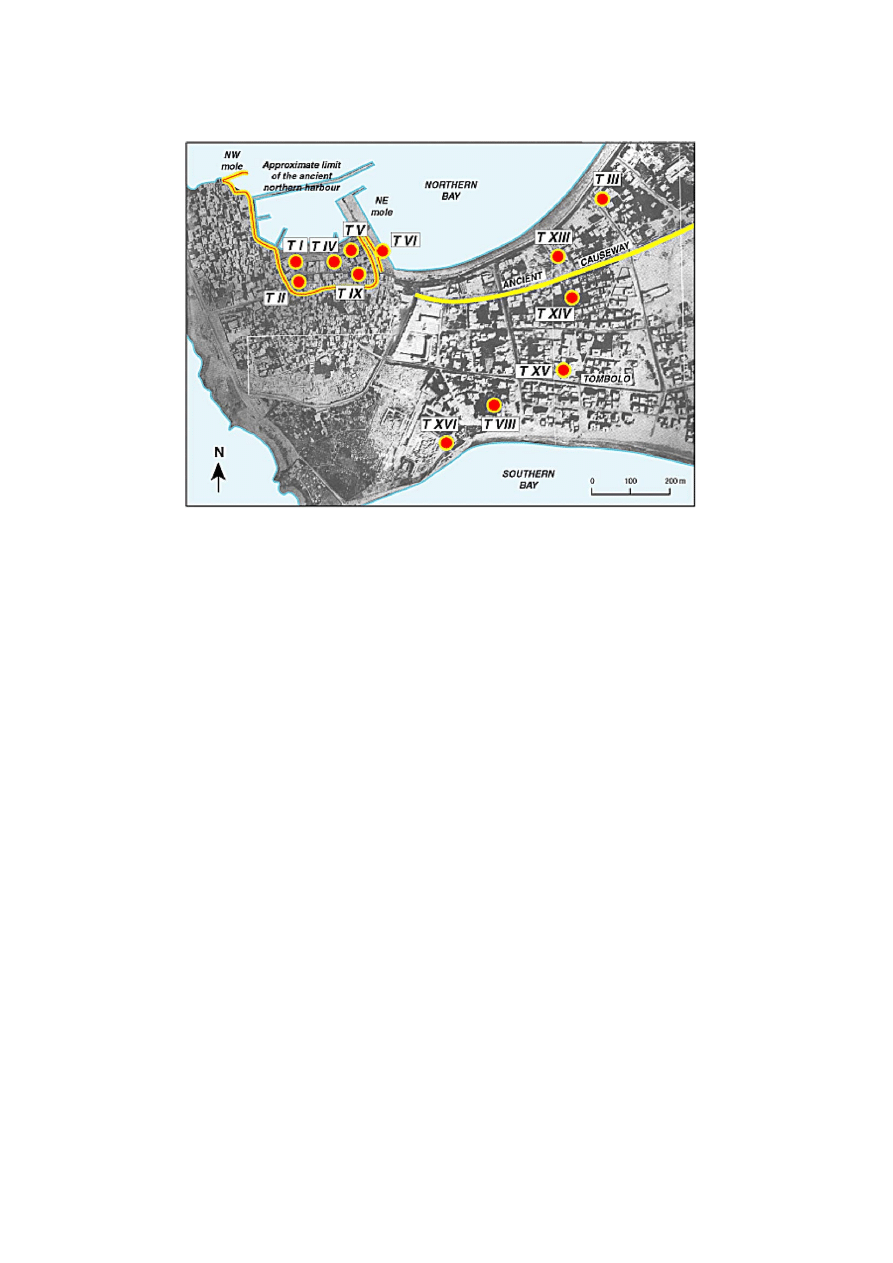

The immersion and coastal erosion of the natural sand-

stone ridges forced ancient societies to build offshore break-

waters. An ancient mole, discovered by Poidebard

, pro-

tected the northern harbour. Currently –2.5 m underwater, this

structure is ca. 3 m high and composed of at least five stone

layers

. In order to effectively shelter the ancient basin

this implies a subsidence of at least 3.5 m. Absence of under-

water excavations means this structure is yet to be precisely

dated.

High-resolution topographical surveying, urban morphol-

ogy, coastal stratigraphy, old photographs, gravures

and

archaeological diving allow us to precisely determine the

maximum extension of the MBA northern harbour (

). It

was twice as large relative to present, with a large portion of

the former basin lying beneath the modern market. On the

seaward side, an important portion of the former basin is today

located between the present-day breakwater and its ancient

submerged counterpart. This zone presently holds very strong

Fig. 2

.

Reconstructed palaeo-bathymetry of Tyre around 6000 years BP. Coastline reconstructed using stratigraphy, present bathymetry and geochronology.

185

N. Marriner, C. Morhange / Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

potential in terms of its coastal heritage, which must be pro-

tected by politicians, urban planners and architects, in addi-

tion to being studied by archaeologists.

3. Palaeogeography of Sidon’s ancient northern

harbour

In contrast to Tyre, relative sea-level in Sidon has been

more stable during the late Holocene and its geomorphologi-

cal context is different

. Raised shoreline markers are scat-

tered and their elevation is low. On the offshore harbour island

of Zire, 500 m off Sidon, the bottom of an ancient quarry is

sealed by a beach-rock at ca. +50 cm. It contains quarried

blocks mixed with well preserved marine shells and attests to

Zire island undergoing a minor ‘yo–yo’ movement around

ca. 2000 BP. Therefore, the Sidonian coastal landscapes were

more stable than Tyre during the mid-Holocene, with the

exception of the Awali estuary which formed a drowned val-

ley or ria (

The northern harbour of Sidon is naturally better pro-

tected than Tyre, by a long coastal ridge, which has never

been completely immersed (

). As in Tyre, our core analy-

ses allow us to identify three main sedimentary units corre-

sponding to three harbour environments.

(1) A MBA semi-open harbour.

Appearance, for the first time, of fine-grained material and

muddy-sand biocenoses represents a sheltering of the har-

bour bay around 1700–1450 cal. BC. This protection corre-

sponds to a great deal of activity in the harbour. Current Brit-

ish Museum excavations have demonstrated the importance

of this period

(2) Important scouring and dredging practices during

Roman and Byzantine periods explain why first millennium

BC strata (i.e. Phoenician harbour sediments) are often absent.

(3) During the Roman period, the bio-sedimentological

indicators reveal an environment well-protected from the

open-sea. The macrofauna are typical of a confined lagoonal

environment. This unit corresponds to a closed harbour in

which significant low-energy sedimentation processes are at

work. Silting intensified until the end of the Byzantine period.

This confinement of the harbour resulted from protective

structures far more effective than any previously built, and

similar to the interior quay and anthropogenic modification

of the sandstone ridge studied by Poidebard and Lauffray

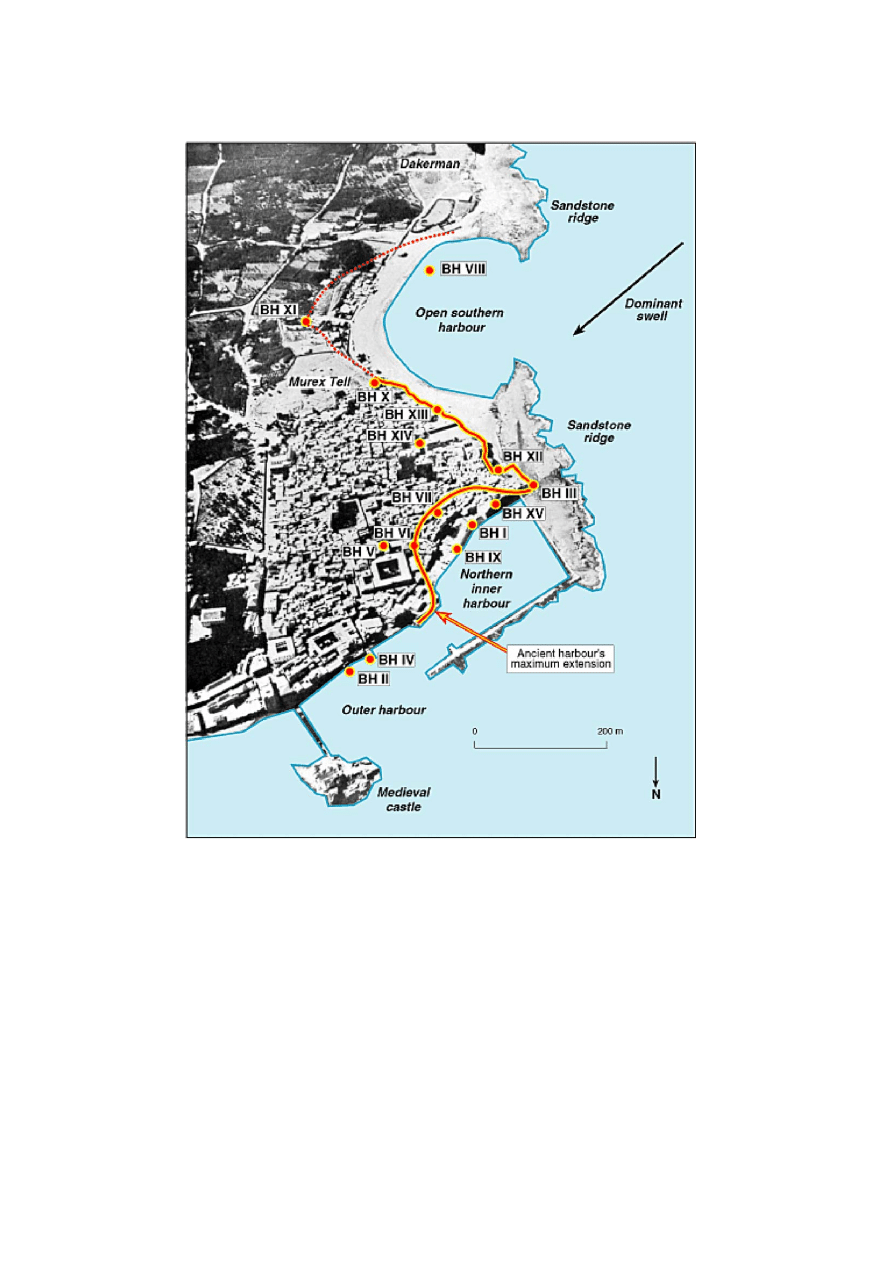

As in Tyre, nearly half of the northern port of Sidon lies

beneath the Medieval and Modern city (

). This coastal

progradation is linked to a positive sediment budget, associ-

ated with three main factors: (a) At the scale of the Litani and

Awali watersheds, accelerated soil erosion resulted from agri-

cultural development and forest clearance. Evidence for large-

scale deforestation in the Levant is dated to around 4500–

3500 BP

. On a smaller scale, runoff and now-

artificialised small streams converging inside the harbours also

played a role in the silting-up processes.

(b) Fusion of mud-clay structures from the respective

nearby cities. With the exception of public buildings, urban

constructions were characterised by mud-brick walls

Runoff of small particles, via streets converging on the har-

bour, explains part of the harbour infilling

(c) The basins were also used as huge base-level waste

deposits. For example, the coarse harbour sediment fractions

consist of numerous species of wood, leather, ceramics and

reworked macrofauna.

Fig. 3

.

Maximum extension of Tyre’s MBA northern harbour.

186

N. Marriner, C. Morhange / Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

4. Conclusion

To summarise, we strongly recommend that the ancient

harbours of Tyre and Sidon be protected. As a counter-

example, the recent construction of a coastal road along

Sidon’s northern harbour destroyed most of the remnants of

its ancient sea-wall and covered part of the ancient basin, com-

pletely disregarding its archaeological and touristic poten-

tial. For the development of Phoenicia’s ancient coastal heri-

tage, it would be advisable to begin terrestrial excavations of

Fig. 4

.

Reconstructed palaeo-bathymetry of Sidon around 6000 years BP. Coastline reconstructed using stratigraphy, present bathymetry and geochronology.

Fig. 5

.

The ancient breakwater from Sidon’s northern harbour, in Poidebard and Lauffray

, pl. 51. These remains have since been destroyed, following the

construction of a new breakwater.

187

N. Marriner, C. Morhange / Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

these two famous harbours, as in Marseilles, France

Naples, Italy or Caesarea, Israel

The nature of Tyre and Sidon’s coastal landscape evolu-

tion over the past 6000 years means that the heart of the

Bronze Age, Phoenician, Greek, Roman and Byzantine ports

could be excavated on land, in much the same way as a clas-

sic terrestrial dig. Given the outstanding preservation proper-

ties of the fine-grained sedimentary contexts, coupled with

the presence of the water table, these two Levantine harbours

are excellent historical archives. The originality of ‘the ancient

harbour under the city centre’ is very promising in terms of

future harbour excavations. Any construction works, for foun-

dations, basements, underground car parks or the like, should

imperatively be preceded by an archaeological rescue exca-

vation. Indeed, it is perfectly conceivable that wooden arte-

facts, such as wrecks and piers, be found. The creation of

coastal ‘maritime archaeological parks’ is a feasible possibil-

ity and offers good opportunities for the future durable devel-

opment of tourism and the Lebanon’s world image

Acknowledgements

The authors warmly thank the AIST, notably M. Chalabi,

for generously funding the radiocarbon dates (Tyre). The

research was undertaken within the framework of the pro-

grammes CEDRE F60/L58 and UNESCO CPM 700.893.1.

This work has benefited from an Entente Cordiale student-

ship.

Fig. 6

.

Maximum extension of Sidon’s MBA harbours.

188

N. Marriner, C. Morhange / Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

References

[1]

E. Renan, La Mission de Phénicie, Imprimerie Nationale, Paris, 1864.

[2]

A. Poidebard, Un grand port disparu, Tyr. Recherches aériennes et

sous-marines, 1934–1936, Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, Paris,

1939.

[3]

A. Poidebard, J. Lauffray, Sidon, aménagements antiques du port de

Saïda, étude aérienne, au sol et sous-marine (1946–1950), République

libaniase, ministère de Travaux Publics, Beyrouth, 1951 (pp. 95).

[4]

H. Frost, Recent observations on the submerged harbourworks at

Tyre, Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth XXIV (1971) 103–111.

[5]

H. Frost, The offshore island harbour at Sidon and other Phoenician

sites in the light of new dating evidence, The International Journal of

Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration 2 (1973) 75–94.

[6]

P. Bikai, The Pottery of Tyre (Ancient Near East), Aris and Phillips,

Oxford, 1979 (208).

[7]

H.J. Katzenstein, The History of Tyre, Goldberg Press, Jerusalem,

1997 (373).

[8]

E.G. Reinhardt, A. Raban, Destruction of Herod the Great’s harbor

Caesarea Maritima, Israel, geoarchaeological evidence, Geology 27

(1999) 811–814.

[9]

J.C. Kraft, G.R. Rapp, I. Kayan, J.V. Luce, Harbor areas at ancient

Troy: sedimentology and geomorphology complement Homer’s Iliad,

Geology 31 (2003) 163–166.

[10] J.-P. Goiran, C. Morhange, Géoarchéologie des ports antiques de

méditerranée, Topoi 11 (2003) 645–667.

[11] V. Goldsmith, S. Sofer, Wave climatology of the southeastern Medi-

terranean, Israel Journal of Earth Science 32 (1983) 1–51.

[12] K. Fleming, P. Johnston, D. Zwartz, Y. Yokoyama, K. Lambeck,

J. Chappell, Refining the eustatic sea-level curve since the Last Gla-

cial Maximum using far- and intermediate-field sites, Earth and Plan-

etary Letters 163 (1998) 327–342.

[13] C. Morhange, P.A. Pirazzoli, D. Chardon, N. Marriner, L.F. Montag-

gioni, T. Nammour, Late Holocene relative sea-level changes and

coastal tectonics in Lebanon, Earth and Planetary Science Letters

2005 (submitted).

[14] N. Marriner, C. Morhange, I. Rycx, M. Boudagher-Fadel,

M. Bourcier, P. Carbonel, et al., Holocene coastal dynamics along the

Tyrian peninsula, south Lebanon; the palaeo-geographical evolution

of the northern harbour, Bulletin d’Archéologie et d’Architecture

Libanaises (2005) (in press).

[15] N. Marriner, C. Morhange, M. Boudagher-Fadel, M. Bourcier, C. Car-

bonel, A. Marroune, Geoarchaeological evidence for the palaeoenvi-

ronmental evolution of Tyre’s ancient northern harbour, Phoenicia,

Journal of Archaeological Science (2005) (in press).

[16] I. Noureddine, M. Helou, Underwater archaeological survey in the

northern harbour at Tyre, Bulletin d’Archéologie et d’Architecture

Libanaises (2005) (in press).

[17] C. Descamps, personal communication.

[18] M. Chalabi, Rapports Occident-Orient analysés à travers les récits de

voyageurs à Tyr du XVIe au XIXe siècle, Publications de l’université

libanaise, Section des études historiques 44, Beyrouth, 1998 (294).

[19] in: C. Doumet-Serhal (Ed.), Sidon-British Museum excavations

1998–2003, Archaeology and History in Lebanon 18, 2003, pp. 144.

[20] S. Bottema, H. Woldring, Anthropogenic Indicators in the Pollen

Record of the Eastern Mediterranena, in: Bottema, Entjes-Nieberg,

Van Zeist (Eds.), Man’s Role in the Shaping of the Eastern Mediter-

ranean, 1990, pp. 231–264.

[21] Y. Yasuda, H. Kitagawa, T. Nakagawa, The earliest record of major

anthropogenic deforestation in the Ghab Valley, northwest Syria: a

palynological study, Quaternary International 73 (/74) (2000) 127–

136.

[22] E. Ribes, D. Borschneck, C. Morhange, A. Sandler, Recherche de

l’origine des argiles du bassin portuaire antique de Sidon, Archaeol-

ogy and History in Lebanon 18 (2003) 82–94.

[23] A. Hesnard, Les ports antiques de Marseille, Place Jules-Verne, Jour-

nal of Roman Archaeology 8 (1995) 65–77.

[24] A. Raban, K.G. Hollum, Caesarea Maritima: a Retrospective After

Two Millennia, Brill, Leiden, 1996 (pp. 694).

[25] A. Raban, Archaeological park for divers at Sebastos and other sub-

merged remnants in Caesarea Maritima, Israel, International Journal

of Nautical Archaeology Underwater Exploration 21 (1992) 27–35.

[26] L. Franco, Ancient Mediterranean harbours: a heritage to preserve,

Ocean Coastal Management 30 (1996) 115–151.

189

N. Marriner, C. Morhange / Journal of Cultural Heritage 6 (2005) 183–189

Document Outline

- Under the city centre, the ancient harbour. Tyre and Sidon: heritages to preserve

- Acknowledgements

- References

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

The use of additives and fuel blending to reduce

Dark Sun City under the Sands Jeff Mariotte v1 rtf

Valerie M Hope Death and Disease in the Ancient City (2004)

A Chymicall treatise of the Ancient and highly illuminated Philosopher

Under the files

Maps of the Ancient World Ortelius A Selection of 30 Maps from The Osher and Smith Collections

Redhot chilli peppers Under The Bridge

Everburing Lamps of the Ancients

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Analysis of the?ginning

Under the full Moon

Amon Amarth Under the Northern Star

Under The Wings of?ath (I)

A Chymicall treatise of the Ancient and highly illuminated Philosopher

ebook The Ancient World (4 of 7)

PORTER, SCHWARTZ Sacred Killing the archeology of sacrifice in the ancient near east

RECHTE Human sacrifice in the ancient near east

Forward, Robert L Rocheworld 3 Ocean Under the Ice

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

więcej podobnych podstron