M E A N S O F S U B S T I T U T I O N.

T H E U S E O F F I G U R I N E S, A N I M A L S,

A N D H U M A N B E I N G S A S S U B S T I T U T E S

I N A S S Y R I A N R I T UA L S *

Lorenzo Verderame**

In the present article I propose an overview of substitution practices in rituals described

in Neo-Assyrian literary and documentary sources. From the most simple and diffused

means of substitution (figurines) to the most complex (animals and human beings) I

analyze the different use of substitution and of its syntagms as evolving according to

complexity. In particular, the main focus will be on the identity transmission and the

identification process. Two different ideas of counteracting the evil emerge. One aims

at annihilating the evil by directing it back to its source; the other realizes the fate of the

patient (death) by the means of a substitute. Three main groups of procedures involv-

ing substitution are hereby: anti/witchcraft rituals, healing rituals involving animals

(

Incantation of the piglet, A man’s substitute for Ereškigal), the “substitute king”.

Introduction: Aims and Sources

ubstitution in a broad sense constitutes one of the basic mechanisms of

cultural construction, and it has been widely discussed. In this paper, I will

not be considering the multiple aspects of substitution in the construction of

a ritual discourse, but rather I will focus on the specific use of objects, ani-

mals, and even human beings as substitutes for a person. The analysis will

commence with simple rituals involving the most affordable and so the

cheapest materials, and then move to elaborate rituals, showing the different

uses of substitution and the proportional increase in contingent factors.

Most of the sources I will discuss come from the Neo-Assyrian period. I

have chosen this period for several reasons. First of all, because this is the pe-

riod which provides the greatest number of documents, which result from

the excavation of cuneiform tablet collections generally called “libraries”.

1

Secondly, some of these rituals are already known from previous periods, and

an objection which may be raised is that the Neo-Assyrian material is consid-

* Abbreviations follow those used in the

Chicago Assyrian Dictionary and R. Borger, Handbuch der

Keilschriftliterature, Berlin, 1967-75; a complete and updated list is available from the CDLI (http://cdli.

ucla.edu/Tools/abbrev.html). The texts have been numbered (§1-13) for the sake of ease and discussion.

Where not otherwise stated, the translation as well as the paragraph, line and numbering arrangements

are those proposed by the authors quoted in the footnotes.

** “Sapienza”, Università di Roma.

1 The “Assurbanipal Library” in Nineveh, the “house of the exorcist” (N4) in Assur, Sultantepe/@uzi-

rina tablets, the temple of Nabû in Nimrud/Kalhu.

S

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 301

302

lorenzo verderame

[2]

ered “antiquarian”; that is to say that they are copies of ancient documents

that continue to be compiled within the flow of tradition.

2

Yet, documentary

sources, in the form of letters and administrative texts, not only testify to the

fact that most of these rituals were practised in the Neo-Assyrian period, but

they also provide clues about their performance.

3

These rituals attracted the

attention of Ebeling, who gathered together most of those known at the time

in the volume entitled

Tod und Leben (1931). A few years later Furlani, quoting

from Ebeling’s work,

4

devoted a chapter to this theme (“Riti babilonesi e as-

siri di sostituzione del malato”) in his book on Assyrian and Babylonian ritu-

als (Furlani, 1940: 285-305). Lastly, some of these rituals are available in excel-

lent editions of recent publication; thus permitting the focus to fall on the

ritual, rather than proceeding with a new translation and more philological

discussions.

In the following sections, I will analyse a series of substitution procedures,

grouped according to the nature of the substitute and the aim of the ritual.

From simple objects used as substitutes in different kinds of rituals to healing

procedures involving a substitution by the means of animals or humans, this

study focuses on the role of substitution and the increasing complexity in the

ritual performance and construction.

Substitute figurines

The use of figurines is one of the main means to operate a substitution.

5

The

following example demonstrates the basic mechanism of substitution in-

volving figurines:

§1. For undoing witchcraft which you do not know, you make figurines ((of wax)) of

the warlock and the witch, ((of a man and of a woman)). You convict them before Ša-

maš. You coat them with tallow; you put them in a disposable pot. You burn them: “Ša-

maš, may their sorcerous devices return to them who turned the evi[l] against me!” (or:

who stood as an evil sign against me”)((Thus)) you speak ((three times)), then [you

throw] the disposable pot together with the burnt mater[ia]l into the river. (

Ana pišerti

kišpi §1: 11’-19’)

6

This brief text describes a short ritual to cast out sorcery (

ana pišerti kišpi).

Wax figurines substitute the warlock and the witch, who harmed the patient.

2 The theme has been discussed in several articles in Radner and Robson (2011).

3 This is the case of the last of the rituals analysed here, that of the substitute king (šar puhi), whose

sources are limited to the Neo-Assyrian period and are mainly letters.

4 These practices are generally defined as “sacrifices”. This concept was already criticised by Furlani

(1940: 11 fn. 14), that is, the use of the term

Ersatzopfer by Ebeling (1931), together with the classification

of ritual killings as “human sacrifices” in Mesopotamia. Nevertheless, this precedent is still diffuse far be-

yond the limits of Assyriological studies; see Mayer and Sallaberger (2003-05: 101 §10).

5 The use of body secretions (hair, nail pairings, excrement, sperm, and so on) or objects (cloth and

so on) as means of substitution will be dealt with separately in this article; they will be discussed as a

means of identity transmission in more complex rituals (§8).

6 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 50).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 302

[3]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

303

As in a legal procedure, the charges against the evil-doers are imputed to the

figurines. Finally, these are first destroyed by fire and then, together with the

rest of the ritual

paraphernalia, thrown into the river. The text is concise and

offers no further details of the ritual, but it clearly states that the origin of the

witchcraft is unknown (

ša la tidû).

7

Apparently no intervention of a cultic op-

erator is prescribed

8

and the ritual instructions (“you will …”) are directed to

the patient who acts as the healer as well.

9

The following text is a little more complex. It is composed of a description

of symptoms and their interpretation (diagnosis), followed by instructions as

to how to annihilate the cause of the ailment.

§2. If a man’s body is afflicted with paralysis, he is constantly feverish, his [f]lesh is be-

ing ruined, and he cannot have intercourse with a woman, (then) f[igurines] of clay

representing him have been buried (in a grave). You go to the clay pit, and you put one

grain of silver (and) one grain of gold into the clay pit. You buy clay, (then) you make

figurines of the warlock and the witch. You then write their names on their sides. You

tie their arms with a rope on their back. You wrap them with combed-out hair. You

pour out tanning fluid (var.: rancid oil) over them. You lift them up in an unfired …-

bowl. Before Šamaš, you convict them. You wash your hands and your feet over them

with water from the holy water vessel. You rub his

epigastrium with dough made of

wheat flour (and) egg; then you put (the dough) on them. You make him recite before

Šamaš as follows: “Šamaš, lord of heaven and earth, you alone are the judge of god and

man! Šamaš, he (var.: the one who) performed, turned to, (and) sought witchcraft,

magic, sorcery, (and) wicked machinations against me – may they be dispelled from

me, may they be attached (to him) from the (very) day that I speak (this prayer) before

you, then I shall proclaim your glory!”. He recites (this) seven times, and it will be un-

done. (

Šumma amelu kašip A 38’-70’)

10

The ritual commences with the preparation of figurines of the evil-doers, on

which a series of operations are performed, and it closes with an invocation

to Šamaš. The figurine is firstly associated with either the sorceress or war-

lock, who harmed the patient by inscribing his name on it. Then, the per-

former operates on the figurine in order to annihilate the evil-doer. Firstly, the

part of the body on which the evil-doer operates is neutralised; in this case

his/her arms are tied with a rope behind his/her back.

11

Then he/she is im-

7 On the question of witch/sorcerer identity, see Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 5).

8 The ritual instructions are always addressed to an undefined subject, which must perform and

direct the ritual. Its identity is unknown, even though it is generally assumed that it is the

ašipu; an

assumption based on very vague evidence, see Couto-Ferreira (in press). An additional participant, the

patient himself or another cultic operator, may be involved.

9 This is the case of the text §4 and §5 as well. The conciseness of the instruction and the self-

performance of the ritual suggest that this might be a popular remedy. If it was, the origin of these

prescriptions and the aim of these ritual collections should be questioned.

10 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 77).

11 This is one of the most common actions carried out on (anti-)witchcraft figurines, as the texts and

the archeological documents as well as comparative material show. Other symbolical and functional

parts may be the target of this restraining attack, that is, the mouth and the feet; see §6 where the mouth

of the opponent is sealed.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 303

304

lorenzo verderame

[4]

mobilised by wrapping the figurine in combed hair and pouring tanning flu-

id over it.

12

After having disposed of the figurine in a bowl, it is convicted in

front of Šamaš. The cultic operator then cleans himself and, at the same time,

transfers the pollution

13

onto the figurine by way of letting the water he has

washed his hands and feet with flow over the figurine. Successively, the evil

affecting the patient is transferred back onto the evil-doer, by affixing the

paste used to rub the victim’s

epigrastrium on the figurine. The repetition sev-

en times of an invocation to Šamaš renders the ritual effective for the undo-

ing of the witchcraft.

The focus of both rituals is the annihilation of the origin of evil by means

of clay figurines, which substitute it. The use of figurines (s

almu) to operate

on a person, who is not physically present,

14

is widespread in Mesopotamian

rituals;

15

particularly in anti-witchcraft (

Maqlû). The use of substitute fig-

urines is also one of the main methods of witchcraft,

16

but it is only indirect-

ly documented in the anti-witchcraft instructions as the cause of illness and

suffering in the diagnostic section. The mechanics of substitution in the two

cases (witchcraft and anti-witchcraft) are the same; the figurine simply sub-

stitutes the person to be harmed. The only difference is that the substitute fig-

urine of the evil-doer has to be destroyed in order to destroy him/her and an-

nihilate his/her witchcraft. On the other hand, the sorcerer/warlock creates

the figurine of the victim and then hides it in specific places with the aim of

it not being discovered and/or destroyed.

17

In fact, the basic idea is that the

witchcraft endures for as long as the object exits. From this point of view, as

already observed by Gasche (1994: 100), while the aim of the anti-witchcraft

ritual is the annihilation of the evil-doer by destroying the figurine repre-

senting him/her, the few discoveries of this type are the ones produced by

witchcraft.

18

Substitute figurines are not limited in their use to witchcraft and anti-

witchcraft. Being an easy and versatile means to operate at a distance on oth-

12 The pouring of

kurru, interpreted as rancid oil or tanning fluid, into the mouth of the insolvent

party appears in the penalty clause of Neo-Assyrian contracts (Verderame, 2010a: 468).

13 The basic idea is that of transmission by contact: the cultic operator cleans only his body parts that

will touch the ritual

paraphernalia (the hands) and the ground (the feet). The term “pollution” is used

here to express the wide range of hazards to which the operator is exposed by performing the ritual.

14

kima šunu la izzazzu «since they are not present» (Abusch and Schwemer, 2011: 22).

15 Daxelmüller and Thomsen (1982).

16 In the text discussed here, the method used to neutralise evil-doers is the same as that used by them

against their victim. In fact, in the diagnostic section, the cause of suffering of the patient is a figurine of

himself buried in a grave; cf.

Maqlû IV, 27-47.

17 See §9 and §10 where the object of the witchcraft is found and the ritual is performed upon it.

18 The only known case from Mesopotamia is that from Tell ed-Der, published by Gasche (1994) and

discussed recently by Schwemer (2007: 212-214). Another example from the Near East is the collection of

metal figurines from Tell Sandahannah; see Gasche (1994: 100 fn. 7). Finds from the Classical world are

more diffuse. The Greek material has been the object of several studies by Faraone (1991, 1993). The re-

cent discovery of the cache of witchcraft objects in the cistern of Anna Perenna’s fountain in Rome has

been the subject of several articles collected together in

Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni 76/1 (2010).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 304

[5]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

305

er people, they might be used for other kinds of purposes; for example, the

divination or the enchantment of a desired woman, as the two following ex-

amples from the potency incantations series (šà.zi.ga) demonstrate:

§3. Its ritual: you mix together dough (made of ) emmer and potter’s clay; you make fig-

urines of the man and the woman, put them one upon the other, and place them at the

man’s head, then recite [the incantation] seven times; you remove (them) and [put them

near] a pig. If the pig approaches, (it means) “Hand-of-Ištar”; (if ) the pig does not ap-

proach [the figurines], (it means) that man has been affected by sorcery (

KAR 70: 6-10)

19

In this ritual related to the sexual potency, the patient and his partner are sub-

stituted by two figurines, which are arranged one on top of the other in the

act of having sexual intercourse. These figurines are then employed for div-

ination by the means of a pig.

The following ritual for the enchantment of a woman is performed when

others have failed: a figurine of the woman is fashioned and her name is in-

scribed on the hip; then the figurine is enchanted with an incantation recited

in front of Šamaš and buried in a symbolical and liminal place, one of the

gates of the town; while the desired woman passes over the figurine, the man

recites the incantation again and the enchantment succeeds.

§4. If that woman (still) does not come, you take

tappinnu-flour (and) throw (it) into

the river (banks), from the far side (of the Tigris) and the far side (of the Euphrates);

you make a figurine of that woman, you write her name on its left hip; facing Šamaš,

you recite the incantation “The beautiful woman” [over] it. At the outer gate of the

West Gate you bury it … During the hot part of the day(?) or during the evening(?) she

will walk over it. The incantation “The beautiful woman” you recite three times; that

woman will come to you (and) you can make love to her (

KAR 61: 11-21)

20

In this ritual a figurine is used to influence another person, thereby con-

straining her to act according to the performer’s will. This instance brings this

study to the problematic separation between witchcraft and anti-witch-

craft.

21

In fact, this ritual, even if not aimed to harm the desired woman,

obliges her to act against her own will. The

ušburruda rituals go further and

confirm the difficulties in adopting the strict dichotomy between witchcraft

and anti-witchcraft based on the idea of a counter-action.

§5. Its [ri]tual: You take an unfired potter’s pot (and) put bitumen (and) … inside. You

arrange it before Šamaš. You set up a censer with

burašu-juniper, you pour a libation of

19 Biggs (1967: 46).

20 Biggs (1967: 70).

21 This specific ritual, together with the one that follows, raises the problem of the nature of the

sources under investigation. In fact, on the one hand, most of these texts are collections of different rit-

uals to cure the same symptom / condition, often from the most simple to the more complex. The ritu-

al §4 is part of a collection of procedures to attract a woman and it has to be performed when others

have no success (diš ki.min be

-ma munus bi nu du-ku «if (you do this) and the woman does not come,

(then).»,

KAR 61: 11). On the other hand, these collections include rituals aimed at influencing or harm-

ing other people and could only in a broad sense be classified as anti-witchcraft.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 305

306

lorenzo verderame

[6]

beer. (You make) two figurines of cedar wood, two figurines of tamarisk wood, [two

figurines of d]ough, two figurines of clay, two figurines of tallow, two figurines of wax,

two figurines of bitum[en], [two figurines of p]omace. You recite the incantation “She

is evil, the witch”. [When] you have recited (it), you throw these figurines into the pot.

You stir (or: beat) them [with a stick] of e

ru-wood. When you have recited (it), you

break (her) [ne]ck, you tear her skin, you tear out her […]. [You say]: “My sorceress,

my enchantress, I calm your heart with water!” (Then) you throw (it) [into the ri]ver.

You recite the incantation “May the mountain cover you!” You bury […] either under

a (washer’s) mat or in a washroom (

Ušburruda §7.6.2: 24”-34”)

22

The ritual “I burn the opponent” (

nakra aqalli / kúr.kúr bíl) is directed

against an opponent, who has already performed a “cutting-of-the-throat”

(

zikurudû/zi.ku5.ru.da) incantation against the “patient”. The latter coun-

teracts the action of the sorceress, who has performed the witchcraft; as in

the ritual in §5 above. The kúr.kúr bíl incantation, however, is used to harm

an adversary in court (

bel dababi), even if the said adversary has not performed

any witchcraft against “the patient”:

§6. You recite the [incantation]; then you scatter sulphur into the crucible. As soon as

the reed fire has burnt down, you extinguish them (i.e., the figurines) with river water.

Afterwards you make a figurine representing his litigant of clay from the clay pit. You

twist its arms behind it. [You] se[al its] mouth with a seal of

šubû-stone and (a seal) of

šadânu-stone. You convict it before Šamaš. [He washes] his hands over (it). This incan-

tation [he recites] three times … (

Ušburruda §7.6.6: 33-39)

23

In this case, the person assisted by the cultic operator does not counteract a

spell cast by an opponent, and thus could not be called “patient”.

Substitution syntax

There are limitless examples of the use of figurines in rituals, but those cited

here offer a good sample in order to analyse the mechanics of substitution.

The figurines have first to be fashioned. In anti-witchcraft, the most com-

mon material is clay or wax, which can be easily dissolved in water and melt-

ed by fire. A variety of other materials, particularly a paste made of flour and

other ingredients, are used, as §5 testifies. The archaeological remains from

other cultures testify to the wide use of figurines made of metal, mainly

bronze.

24

These objects are produced by witchcraft and, as stated above, their

aim is to last. The use of metals, in this sense, might be justified when con-

fronted with anti-witchcraft figurines made of perishable materials.

In the fashioning of the actual figure, no resemblances with the features of

the person to be harmed are required. Quoting the law of similarity of Hu-

22 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 140).

23 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 143).

24 See above.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 306

[7]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

307

bert and Mauss (1902-03: 66): «une simple figure est, en dehors de tout contact

et de toute communication directe, intégralement représentative … la seule

mention du nom ou même la pensée du nom, le moindre rudiment d’assim-

ilation mentale suffit pour faire d’un substitut arbitrairement choisi … L’im-

age n’est, en somme, définie que par sa fonction, qui est de rendre présente

une personne».

25

In the examples cited here, the identification of a figurine

with the person who has to be substituted is made by writing his/her name

on the side of the figurine (§2, §4). In §3, the identification is made by contact:

the figurine is placed at the man’s head. In §5 and §6, no reference to an iden-

tification method is mentioned, but one could suppose that this was fulfilled

orally. In fact, in §5 the fashioning and manipulation of the figurine is followed

by incantations addressed directly to the witch in the third and second person

(«She is evil, the witch», «My sorceress, my enchantress, I calm your heart

with water!»).

In §1, where the identity of the evil-doer is unknown, the association of the

figurine with the evil-doer is referred to by way of the conviction by Šamaš.

This section is present in almost all the rituals discussed

26

and has to be con-

sidered central in the identification process. The appeal to Šamaš, the sun,

who sees everything and reaches everyone, ensures the identification

27

and

the persecution of the evil-doer. Šamaš is recalled as supreme judge, who

evaluates the deeds of the witch and the sorceress,

28

establishing the inno-

cence of the petitioner and making effective, by his intervention, the action

against the evil-doer. The appeal to Šamaš may be strengthen by successive

prayers (§1, §2), where the god is requested to restore the evil back to the evil-

doer. Parallel to substitution, the appeal to Šamaš must be interpreted here

in a further sense. In fact, anti-witchcraft procedures in most cultures assume

the form of a process against the warlock or the sorceress. The standard

expression “you sue it/them in front of Šamaš” (

ana mahar Šamaš tadânšu/

šunuti), with the use of the verb dânu “to judge”, recalls the idea of this

procedure.

29

Transmission, as a form of substitution, is a basic element of the ritual

practice, so it is used in order to fulfil different purposes. Contact is the main

means of transmission. In §3, the identity of the patient is transmitted by con-

tact with the figurine, upon which divination will be performed. In §4, the de-

sired women, walking over the buried figurine, makes the identification with

25 Note that in the ritual involving the use of a reed effigy (see fn. 46), besides contact, the dimen-

sions of the effigy recall the identity of the patient. The different means and level of identification will

be treated below, when describing more complex rituals.

26 The only exception is §3 where the figurine, a substitute of the patient himself, is identified by

transmission (see above).

27 From this point of view, the appeal to Šamaš may by-pass (§1, §6) or reinforce the identification.

28 Schwemer (2007: 205-208) with previous bibliography.

29 Even if in a different way, this phase assumes the form of a real process in more complex rituals,

that is, the substitute king (see below).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 307

308

lorenzo verderame

[8]

the latter effective. In general, anti-witchcraft procedures use substitution in

order to operate on an absent person. In fact, a contact with the witch or sor-

ceress, if their identity is known,

30

is almost impossible. Transmission is then

used to transfer, not the identity of the substituted person, but the pollution

affecting the cultic operator and his client together with the evil of witchcraft,

to the warlock or the sorceress. Direct contact is avoided and a vector trans-

ferring the pollution and evil is adopted. In §2, paste, rubbed first on the pa-

tient’s

epigastrium and then applied on the figurine, fulfils this task. In the

same procedure, the cultic operator washes his hands and feet over the fig-

urines, transferring onto them the pollution he has came into contact with.

31

Water plays a prominent role in Mesopotamian rituals, being both a means

of purification and of transmission.

§7. I wash myself over her, I bat[he] with water over her. Just as the water (washing)

my body runs off and flows over her head and her body, (just as) I cast my guilt (and)

my sin upon her, let any evil, (([anything not good])), that is present in my body, my

flesh (and) my sinews, ((var.: [the evil of dreams, of evil, ba]d [sig]ns (and) omen[s, of

witch]craft, sorcery, magic (and) [evil] mach[inations])) run off like the water of my

body and go to her head and her body (

Prayer to Šamaš in the Bit rimki)

32

Furthermore, to the flow of water is assigned the task of carrying away for-

ever the

paraphernalia of the ritual. Therefore, the river has a prominent role

(§1, §5),

33

but the idea of flowing water carrying away pollution and evil is re-

called also in the ritual involving the washer’s mat or washroom in §5.

The operation carried out on the figurines depends on the aim of the ritu-

al. In §3, the figurine is used as a substitute in place of the patient. As his ill-

ness relates to sexual dysfunction, the figurine of the patient and another of

his partner are symbolically mated and then used in a divinatory process in

order to identify the origin of the evil. In §4, the figurine is the receiver/ob-

ject of the enchanting procedure addressed to the desired woman.

In anti-witchcraft rituals and procedures against opponents, the aim is to

harm or to restore the evil to the person substituted by the figurine. There-

fore, the operation on the figurine is two-fold. In the first stage, figurines are

30 Note that in most cultures anti-witchcraft procedures aim first at revealing the identity of the evil-

doer, rather than the immediate pursuance of him/her.

31 Laessoe (1955: 38,

passim); Abusch (1987: 25).

32 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 384 ll. 39-43).

33 The idea of the water of the river, flowing only in one direction and so therefore cannot return, is

diffuse world-wide. The passage of this incantation, from the text of childbirth procedures, exemplifies

the observation and use of what one would call in modern terms “physical laws” in the construction of

effective images «Like a raindrop (lit. a drop of heaven), may it not turn back, like someone falling off a

wall may it not turn back (lit. turns the breast), like a pipe that overflows, may her waters not remain»

(

BAM 248: ii 57-59). I am grateful to Erica Couto-Ferreira for this reference. She discussed the text exten-

sively at the workshop “Childbirth and women’s healthcare in pre-modern societies” held in Heidelberg

(4

th

to 5

th

of November, 2011) and whose proceedings are in preparation. This theme has been extensive-

ly discussed by Couto-Ferreira in her article in the present volume.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 308

[9]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

309

manipulated in order to neutralise the action of the substituted person. Then,

symbolic and functional parts (head/mouth, hands and feet) are turned back-

wards and impeded by the means of bonds. The mouth of the opponent in

§6 is sealed. Other operations aimed at isolating, impeding, and neutralising

the evil-doer are carried out; wrapping the figurine in cloth, coating it with

substances or placing it in a pot.

The ritual in some cases is limited to the neutralisation of the substituted

person. In other cases, particularly those pertaining to anti-witchcraft, the an-

nihilation of the evil is carried out through the ritual destruction of the sor-

ceress and the warlock. Burning with fire and dissolving in water are the com-

mon means of destroying the figurines. Other operations are more detailed

and perform the physical punishment symbolically on the figurine that would

have been imposed on the substitute-person («you break (her) [ne]ck, you tear

her skin, you tear out her […]», §5). Some of these operations are barely un-

derstandable, and they may be interpreted as symbolic acts of neutralisation

or part of the punitive action.

34

More complex anti-witchcraft procedures

The elements previously analysed are now developed into more complex pro-

cedures. The aim of these procedures is different. The following

ušburruda rit-

ual offers an initial example of a different concept of healing. While in previ-

ous anti-witchcraft procedures the goal is to annihilate the evil by directing it

back to its source or actually returning it to its source, in these healing rituals

the fate of the patient, that is, his/her death, is realised by the means of a sub-

stitute.

§8. If a man becomes increasingly depressed, (and) his heart ponders foolish[ness], you

mix ‘hair-of-the-wayside’-plant (and) dust of a (dried) mole cricket in water. You make

two figurines embracing each other. On the shoulder of the first you write thus:

De[se]rter, runaway, who does not keep to his u[n]it. On the shoulder of the second

you write thus: Clamour, wailer, who does not … […]. Afterwards you call them by

their name. – You wipe the man’ s body off with dough made of wheat flour and …

flour. Then you form a figurine (out of this dough) and mount it on both of their arms

turning the heads of both of them, (one) to the right and (one) to the left. (([In the

even]ing, before sunset,)) you sweep the ground near the wall, in a secluded place. You

sprinkle pure water. You set up a portable altar, you strew date(s) (and)

sasqû-flour on

top of the altar. You place a censer with burašu-juniper (next to it). You pour beer. Lift-

ing these figurines you speak thus before Šamaš: – Incantation: “Šamaš, king of heav-

en and earth, you are the judge of god and man, pay attention to my prayer to le[arn]

of my condition! Foolishness, depression, fear (and) fright which I constantly experi-

ence and suffer in my body, in my flesh (and) in [my] sinews: Šamaš, before you this

one replaces me, this one receives (my suffering) from me. (My suffering) is entrusted

34 This is the case of pouring tanning fluid on (§2, cf. fn. 13) or beating the figurines with a stick (§5).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 309

310

lorenzo verderame

[10]

to the figurine of the Deserter, it is driven away to the west, it is removed from my

body!” – You say this. Then, you string seven loaves on a cord; you hang it around his

neck (var.: on their arms). You smear the face of the figurine (made) of dough with the

discharge under his foreskin. You bind nail (parings) from both <his feet> (and) hair

(from) his (head) in a black cloth. You hang it around the neck of the figurine (made)

of dough. You put them into a sewage opening in the wall directing their faces to the

west. You close the sewage opening. Next to the sewage opening you set out crushed

((‘horned’)) salt-plant like (apotropaic) ritual flour heaps. This man washes his hands

with river water and gypsum. You clear away the ritual arrangement. Then he goes

straight home without looking back. The exorcist must not ent[er] (var.: go to) the

house of the sick man before dawn (

Ušburruda against depression 1-37)

35

The procedure begins with a description of symptoms, followed by what ini-

tially seems to be a simple plant-based remedy.

36

Two figurines embracing

each other are then fashioned, and then identified with two mythical figures,

Deserter and Clamor, both by written and oral means. In fact the names of

the two are inscribed on the figurines and then they are spoken. The trans-

mission of the evil from the person to be healed to a third substitute figurine

takes place in two phases.

37

Firstly, figurines are made from the paste previ-

ously rubbed on the body of that person; these figurines are then mounted

on the figurines of Deserter and Clamor. Secondly, secretions from the body

of the sick man are smeared (discharge from under the foreskin) or attached

(nail parings, hair) to the figurines. In the meantime, the place for the ritual

is prepared and an invocation to Šamaš is pronounced. The operation on the

figurines is concluded by placing them in sewage, their faces directed to the

West; the sewer itself is then physically and ritually closed in order to block

the “return” of the figurines, together with their burden of evil and pollution.

Finally, the sick man is cleansed and dismissed from the place of the ritual.

The complexity of the procedure involves the performance of the ritual by a

cultic operator, here identified as the

mašmaššu.

The ritual is built around the idea of a journey of no return, whose final des-

tination is possibly the Netherworld (the West). The figurine of the sick man

is entrusted to the two mythical figures whose features (the running away and

deserting) strengthen the idea of moving away from one particular place. Fur-

thermore, the idea of separation and removal is suggested not only by the ep-

ithet of Deserter, and the negation of a term that suggests the idea of insepa-

rableness (

mukillu), but also by the turning of Deserter’s and Clamor’s heads

away (towards the left and right) from the sick man (figurine). In parallel, the

35 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 156).

36 The relationship of this remedy with the rest of the procedure is unclear.

37 Another interpretation is that the transmission takes place twice, that is to say that it does not take

place in successive steps, but is a repetition or reiteration. This process, by which redundancy in a sort

of aim for completeness may strengthen the effect of the ritual, characterises the performance of the

“substitute king” ritual (see below).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 310

[11]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

311

sick man leaves the place without turning back. The figurines are then placed

in a sewer, a place that recalls the uni-directional flowing of the water.

38

The ritual of §8 is preserved in a text collection of

ušburruda procedures

against

depression (hip(i) libbi). For the same ailment different remedies are

proposed, with substitution figurines as well as with herbs. This raises the

question of the texts being dealt with in this paper, their sources as well as

their goals.

39

Healing rituals involving the use of a substitute and the nature

of the latter will be extensively treated in the remainder of the paper and

some conclusions will be drawn at the end. Now, a final example of the anti-

witchcraft procedure will be discussed, not only for its different nature, but

also as a further example of the means used to carry evil away, and so will

pave the way to the next chapter.

Normally witchcraft objects are buried in secret and symbolic places, with

the aim of the evil-doer being to keep them secret and hidden from the vic-

tim. Therefore, as seen above, the anti-witchcraft procedure is directed

against the origin of the witchcraft, that is, the sorceress or the warlock. A

different type of witchcraft is that of leaving an enchanted object in or near-

by the victim’s house.

40

In Mesopotamia, these procedures are described as

the “cutting-of-the-throat” (

zikurudû / zi.ku5.ru.dè) and the counteracting

procedures focus on the enchanted object.

§9. If ‘cutting-of-the-throat’ magic using an

arrabu-mouse [has been performed]

against a man, and a slaughtered (lit.: “cut”)

arrabu-mouse has appeared in the man’s

house, in [that] house door (and) bolt are bewitched. You ta[ke] this

arrabu-mouse, you

place it [before Sîn]. You clothe it in a pure garment, cover it with a linen cloth, [anoint

it] with fine oint[ment]. The man against whom ‘cutting-of-the-throat’ has been per-

formed you have kneel before Sîn; then [you have him say] thus: “My lord, let me not

die before my time, [undo] the sorcerous devices that have been made against me, un-

tie these knots that have surrounded me!” This you have him say seven times before

Sîn, then you have him bow down. You place his offering ration before Sîn during that

night. On the fifteenth day let him tell Sîn everything that worries him. Let him pray

fervently every day. You take this

arrabu-mouse and pack it into the hide of a mouse.

You pack small pieces of silver, gold, iron, lapis lazuli, steatite (and) (nir)

pappardilû-

stone into it. You then pour oil, fine oil, fine ointment, cedar oil, syrup, ghee, milk,

wine, (and) vinegar into it. You tie up the front (opening), cover it with a linen cloth.

You pack (it) into a tomb. You make a funerary offering, you praise (it), you honour

(it), you perform its rites (fully) up to the seventh day. Then the ‘cutting-of-the-throat’

that has been performed against the man will not approach his body as long as he lives.

(

Rituals against zikurudû 20’-35’)

41

38 See fn. 34.

39 See fn. 22. All these aspects could not be discussed here, but it is worthwhile noting that these

procedures are gathered together according to the cause (the ailment), and not according to the manner

of its cure.

40 In this case, the object of the witchcraft does not substitute the victim; rather it works by being in

constant “contact” with him/her.

41 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 412f.).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 311

312

lorenzo verderame

[12]

A slaughtered

arrabu-mouse has been used to bewitch the door and the bolt

42

of the victim’s house. The dead animal is placed before the moon-god Sîn,

finely dressed and anointed. The victim then invokes the moon-god and

makes offerings to him. The prayers to Sîn last for fifteen days, after which

the animal is prepared and buried according to the funerary customs. The

arrabu-mouse is packed in a mouse skin with precious stones and metals, to-

gether with oil, milk, and other products. The skin is closed and covered with

linen cloth. Finally, it is buried in a tomb and receives regular funerary offer-

ings, praise, and mourning rites for seven days.

The procedure could be divided into two parts. The first one involves a se-

ries of operations before the moon-god, mostly performed by the victim at

night. The second one is the funeral of the

Arrabu-mouse. The combination

of the two releases the man from the evil. From the first part, it should be not-

ed that the appeal is to Sîn, rather than Šamaš, as well as the nightly context

of the procedure. Furthermore, the victim has a performative role only in the

first phase and, subsequently disappears in the second part. This is a central

feature of the identification process in more complex rituals that I will discuss

further on.

Regarding the treatment of the enchanted object, that is, the

Arrabu-

mouse, two things must be noted; firstly that it is packed in a mouse skin and

then ritually buried. With regard to this first point, another procedure used

against

zikurudû may offer further clues.

§10. If ‘cutting-of-the-throat’ magic has been perform[ed] against a man [a]nd was

seen: You take these sorcerous devices that were seen and place them before Šamaš.

You tell Šamaš your distress. Before Šamaš you slaughter (lit.: “cut”) a pig over these

sorcerous devices. You pack these sorcerous devices into the pig’ s skin. You have the

man against whom ‘cutting-of-the-throat’ has been performed speak thus before Ša-

maš: “Šamaš, the one who has performed ‘cutting-of-the-throat’ against me: let him

not

come to see (well-being); let me come to see [well-bein]g.” You have him say (it) sev-

en times before Šamaš; daily [he

will tell] Šamaš his distress. [You …] these sorcerous

devices that are inside the pig’s skin … […]. This ‘cutting-of-the-throat’ magic

will n[ot

approach] that man [(…)] (Rituals against zikurudû 1-10)

43

In this ritual,

44

the unspecified enchanted object is packed in pigskin. It is not

known how the procedure ends; however, from the similarities with §9 it can

be concluded that in some way the pigskin was sent to the Netherworld. It is

noteworthy that the enchanted object is not destroyed or sent directly to the

Netherworld, but it is first identified with the animal that contains it (the

42 On these two liminal places, as well as the way demons found access, see Verderame (in press).

43 Abusch and Schwemer (2011: 412).

44 Further relevant differences with the previous procedure should be noted (§10 is more general and

the object and the place where it is found are not specified; the appeal is addressed to Šamaš), but they

can’t be discussed here.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 312

[13]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

313

mouse in §9, the pig in §10). This animal(-container) is the object of the suc-

cessive operations. In §9, the stuffed mouse is not treated according to its na-

ture, but like a human being. It/he is dressed, anointed, and then buried with

offerings. What remains to be discussed is how to interpret this final act. Does

the animal(-container) with its precious load represent an appealing offering

to the Netherworld, or is it a substitute of the victim? The procedure in-

structions provide no clues; perhaps, this need to clearly differentiate among

the interpretations was not perceived in the Mesopotamian mind, and so in

the ritual constructions generally. On the other hand, the ambiguity and mul-

tiplicity of the interpretative layers may strengthen the effectiveness of the

procedure. This ambiguity, however, is resolved in the successive examples

where animals are employed as substitutes of the victim.

Animals as substitutes

In the previous paragraph two elements were introduced: the use of a sub-

stitute that fulfils the sick man’s destiny; and animals as substitutes. These two

elements are brought together in the next rituals analysed. The basic idea of

a substitute, who by dying instead of the person substituted, realises the sick

man’s destiny and re-establishes the latter’s health, is fulfilled by the means of

an animal in this instance.

Different healing procedures involving the use of clay figurines (§8) or

more simple means as substitutes are known,

45

and it is not clear what are the

differences between these and the rituals involving animal substitutes devot-

ed to the same purpose.

46

One difference may be the seriousness of the ill-

ness, but this is speculation without any foundation. Another reason might

be the cost of the operation; a “simple” ritual on a raw clay model versus a

long sophisticated ritual involving an animal.

47

It should also be taken into

consideration the involvement of one or more cultic operators as a relevant

factor in the complexity and cost of the ritual. In the most simple procedures,

the role of the cultic operator may be limited to giving instructions to the sick

man, who is the main and perhaps, sometimes, the only performer of the rit-

ual. All these factors (complexity, cultic operator and cost) are developed in

the series of rituals hereby analysed.

The first of the two procedures involving animals as substitutes is the

In-

cantation of the piglet. The instructions are provided bilingually (Sumerian/

45 An example is the use of a simple reed effigy reproducing the dimension of the person being

substituted, accompanied by a spell and the breaking of the effigy: «Take a pure reed and measure the

man. Fashion a reed effigy, cast the spell of Eridu upon it, wipe this man, son of his god, break (the reed

effigy) over him and it shall be a substitute for him! May the evil

udug and the evil ala stay away from him,

may the good

šedu and the good lama be present at his side! Incantation: a reed effigy (serving as a)

substitute»,

CT 17, 15: 20’-29’, see Schramm (2008: 50s. ll. 24’-40’); partly quoted in CAD D 149. Cf. the

discussion of §8.

46 Cf. fn. 22.

47 A parallel is the substitution of the lamb with a bird in extispicy.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 313

314

lorenzo verderame

[14]

Akkadian), and describe the procedure when using a piglet as a substitute of

a man attacked by the

asag.

§11. Incantation: evil

asag, who rises like the deluge,

he is clad in splendour, he fills the vast earth,

covered by awe-inspiring aura, endowed with awesomeness.

He roams in the streets, infiltrates the alleys,

he places himself at the side of the man, but no one can see him,

he stays at the side of the man, but no one […].

When he enters the house, his mark can’t be recognised,

when he comes out from the house, he is not noticed,

like a wave is removed, like a wave is posed.

Like in front of a sweeping dust storm that no one can resist,

he don’t retreat, he sheds blood like drizzle,

he constantly cause deaths of livestock.

The living beings, as many as they have a name and are in the country,

from East to West they are in his power.

A man, without his god, […]

he has ensnared this man and then confused his mind,

he has smitten his head and […] his skull,

he has smitten his face and he

make him drop his gaze,

the evil disease stays in his limbs,

hardship […].

Asalluhi sees […] «Go, my son!».

48

Take a piglet, [bandage] the head of the sick man, tear its insides out and [place]

them on the sick man’s

epigastrium. [Smear with] its blood the sides of [his] bed. Dis-

member the piglet at its limbs

49

and spread (its parts) over the sick man. You purify and

clean this man by the means of the pure holy water vessel of the Abzu. You move a

censer and a torch along him, then you scatter at the outer gate twice seven breads

baked on embers.

Give the piglet as a substitute for him! Give the flesh as his flesh, the blood as his

blood, and may (the

asag) take it! Give the insides that you have placed on his epigas-

trium as they are his insides, and may (the asag) take it! The evil […] which is in his body,

the evil […] which is attached to his body, may the piglet be his substitute, may the

piglet be his replacement!

May the evil

udug and evil alu stay apart! May the good šedu and the good lamassu be

firmly at his side!

Incantation of the piglet.

50

The text begins with a mythological introduction describing the

asag

51

and his

deeds, as well as the symptoms of the victim. After the standard formula

48 This formula is quoted only in Sumerian.

49 Or, according to CAD M2 sub mešrêtu p. 40, «dismember the piglet (to correspond to) his (the sick

man’s) limbs».

50 The text has been recently edited by Schramm (2008: §3), see also Tsukimoto (1985: 131-133); the

provisional translation of the Akkadian version is by the present writer.

51 For the class of beings generally called “demons” and their relation with illnesses, see Capomac-

chia and Verderame (2011).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 314

[15]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

315

referring to Asalluhi, the instructions begin. The entire procedure focuses on

the identification process of the substitute and the substituted. The identifica-

tion proceeds through contact and correspondence: the piglet is slaughtered

and his body parts are placed over the sick man’s body to strengthen the iden-

tification of the two; and the piglet’s entrails are torn out and placed on the sick

man’s

epigastrium. In this ritual, as in §2, the epigastrium is conceived as the

symbolical centre of the body.

52

The blood of the animal is smeared on the

sides of the sick man’s bed. Then the piglet is dismembered and its body parts

are scattered over the sick man, identifying the single body parts of the substi-

tute with the body of the substituted. Finally the man is purified and the body

parts of the piglet are given to the

asag in substitute for those of the sick man.

Most of the elements found in the piglet incantation are at the base of the

procedure

A man’s substitute for Ereškigal.

53

The ritual involves the use of a she-

goat that is to be sent to the queen of the Netherworld instead of the patient.

§12. A man’s substitute for Ereškigal.

At sunset, the sick man’s […] the she-goat, in the bed chamber with him […] before

night, at dawn you make it stay firmly […] you lift the she-goat

across the sick man from

his lap.

You enter the house where the earth is dug up. On the soil the sick man and she-goat

you make them lay. You will touch the sick man’s throat with a tamarisk knife; you will

cut the she-goat’s throat with a bronze knife. You wash the

dead’s insides with water

and anoint them with oil; you fill its insides with aromatic plants, you dress it with a

garment, you put sandals at its feet, smear its eyes with kohl, you spill fine oil on its

head. You take the turban off the sick man’s head and you wrap it around its head. You

arrange and dispose of it as if it were the

dead man.

The sick man gets up and goes out through the centre of the door.

The

mašmaš recite thrice the incantation: «The touch of the god touched him». The

sick man

removes … the mašmaš … the mašmaš says: «… NN, the sick man, is gone to his

destiny» and then performs the lamentation.

[x] times you make a funerary offering to Ereškigal, you place s

erpetu-soup while still

hot, you honour and pay respect. You pour water, beer, roasted barley, milk, syrup,

ghee, oil. You make a funerary offering to your family ghost(s), you make a funerary

offering to the she-goat. You recite the incantation «The big brother, my brother» in

front of Ereškigal. You arrange the she-goat as it were alive and you bury it. You pour

[…] barley for Ereškigal and your family’s ghost(s), you perform the lamentation […]

and make a funerary offering.

The sick man returns […] (

LKA 79: 1-33)

54

52 Cf. «you make a clay image of the sorceress and place the

mountain stone on its (the figurine’s) epi-

gastrium», Maqlû IX: 179. Another interpretation could be that the part on which the manipulation focuses

is the part affected by the illness.

53

Ana puhi ameli Ereškigal, better known simply as A substitute for Ereškigal. The ritual is known from

three texts from Assur (

LKA 79-80, KAR 245), which are all similar and overlap each other, see Ebeling

(1931: 65-69), Tsukimoto (1985: 125-130). It is mentioned in two Neo-Assyrian letters,

SAA X 89 and 193. In

the latter, the patient is a prince, possibly Assurbanipal; see Verderame (2004: 22).

54 See Ebeling (1931: 65-69); the provisional translation is by the present writer.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 315

316

lorenzo verderame

[16]

The identification process is emphasised in successive steps here. The first one

is the contact between the substitute and the substituted; they spend the night

together. Successively, a symbolical action involving the placement of the she-

goat on the man’s lap occurs; the lap (

sunu) being strictly related to the act of

recognition or adoption of a child. Thus, the she-goat is associated with the

sick man’s kin.

55

The two, together with the performer, enter a structure

called «the house where the earth is dug up» (

ina biti ašar erseta herû, l. 6); pos-

sibly a periphrasis for the burial. The ritual killing takes place. The sick man’s

throat is symbolically cut by a wooden knife, while the she-goat is killed by

cutting its throat with a metal knife. The she-goat is than prepared for burial.

Firstly, its insides are washed and anointed and the corpse is completely

dressed.

56

Then, another identification element is performed with the turban

of the sick man being wrapped around the head of the she-goat. The identi-

fication process is now completed and the sick man leaves the scene, exiting

by «the centre of the door» (

ina birit babi ussi, l. 16).

Twice the text uses the term “dead” referring to the she-goat. At the end

of the laying out of the substitute corpse, the performer is instructed to

arrange its disposal «as the

dead man» (kima ameli miti

?

(úš), l. 15). The other

evidence is somewhat feeble, but may involve an interesting aspect fully de-

veloped in the “substitute king” procedure. In fact, at the beginning of the

treatment of the corpse, the insides of the she-goat are qualified as those of

the dead (

šá mit-ti, l. 10), a phrase that may refer to those of the sick man. If

the interpretation of the passage is correct, this provides traces of a lexical

layer in the identification process. In fact, on the one hand, the substitution

of the sick man with the she-goat is completed, and the she-goat is called “the

dead”. On the other hand, the sick man is separated by the scene of the pro-

cedure and the actions. Not only does he move away through “the centre of

the door”, but his name is never to be mentioned again. This would be the

first step in a process of tabooing the name, which attains its full meaning in

the “substitute king” procedure, by the adoption of the title of “farmer” by

the substituted king.

After the exit of the sick man, the

mašmaš announces his death by speak-

ing the name over the she-goat corpse and then he performs the lamentation.

The rest of the procedure takes the form of a burial, whose main traits may

reflect the usual funerary customs.

57

Some elements may, instead, be specifi-

cally devoted to avoid the wrath of the Netherworld queen and the family an-

cestors and to facilitate the inclusion of the she-goat among the latter. In fact,

55 See below.

56 Whether this is part of the normal process of corpse treatment in Mesopotamia, or a specific

element of this procedure, is hard to say.

57 It is worthwhile remembering that references to funerals in the Mesopotamian written sources are

rare.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 316

[17]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

317

complex substitution procedures, such as the “substitute king”, involve the

assumption of the substitute’s ghost among the substituted family’s ances-

tors.

In the piglet incantation (§11), the animal is given to the

asag instead of the

victim. It is difficult to say if the piglet is intended as bait for the

asag, or sim-

ply realises the logical consequence of the illness, that is to say “it goes to its

fate” instead of the sick man and so reaches the Netherworld.

58

The two in-

terpretations of course are not mutually exclusive and different interpretative

layers may overlap. References to the Netherworld, on the other hand, are

vaguely expressed in the substitution rituals involving figurines, as in §8. Yet,

this connection is clearly stated in the ritual, which provides a substitute for

Ereškigal (§12), the Netherworld queen. The mythological ground for this

substitution can be found in the story of Tammuz, in particular in the

Descent

of Ištar. Besides, the substitution of a dying person by the means of objects

or animals is known throughout the world.

59

The “substitute king” ritual

At the apex of this pyramidal structure of substitution is the use of a human

being as a substitute. The only case documented by the Mesopotamian writ-

ten sources is the “substitute king” procedure,

60

a complex of rituals involv-

ing the use of a man, and perhaps a woman as well, to fulfil the cursed

destiny of the Assyrian king.

61

The latter, as the leader and representative of

the Assyrian state, might be considered guilty by the gods of a certain sin.

The divine Assembly establishes a verdict of guilt and so condemns him to

death. The verdict is communicated through a lunar eclipse. Instead of

counter-acting the prophecy, this is realised by the means of the “king of

substitution” (

šar puhi). The documents show that, rather than a fixed ritual,

the “king of substitution” is an idea or a plot around which a series of meas-

ures and rites are clustered in order to face different situations. The basic idea

is that of a substitution. The person of the king is separated from the iden-

tity of the king and he takes the identity of the “farmer” (

ikkaru / engar).

Meanwhile, a substitute, the

šar puhi, is elected and identified as the king. His

58 Cf. above the discussion of §10.

59 The same sacrifice is interpreted by some scholars as an offering substituting the worshipper; see

Smith and Doniger (1989).

60 Archaeological sources offer more cases for investigation. Most of them, however, must be in the

first instance interpreted as ritual killings in absence of further evidences. This is the case of the multi-

ple burials in the Ur cemetery or the representations of killed enemy. None of these are related to the

“substitute king”, nor any archaeological evidence of this practice is known up until now, see Verderame

(2010b).

61 The “substitute king” practice is only documented in Neo-Assyrian sources, even though it had a

great impact on contemporary cultures and an echo of this practice can be found in late Babylonian,

Classical, and Biblical sources. See Parpola (1983: xxii-xxxii), Verderame (2004: §II.1.4.1), and Ambos arti-

cle in this volume; a monograph on this topic is in preparation by the present writer.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 317

318

lorenzo verderame

[18]

kingdom lasts one hundred days, after which he goes to his destiny, fulfilling

the prophecy. The king’s original identity is then restored to him. He is king

once more.

The fragment of the lower part of a tablet has been identified as the “sub-

stitute king ‘ritual’”.

62

While some elements point to a similarity with this

procedure, no colophon is preserved and no substitute king is clearly men-

tioned. Furthermore, the preserved part of the text describes a secondary

phase of the terminal process, after the substitute death,

63

which has no clear

meaning in the interpretation of the entire ritual.

The major source of information for the reconstruction of the “substitute

king” procedure is the letters sent to the Neo-Assyrian kings by the

um-

mânus.

64

In a period of almost thirteen years, from 679 to 666 B.C. (covering

the end of Esarhaddon’s reign and the beginning of Assurbanipal’s), five dif-

ferent performances of the substitute king ritual can be identified.

65

The procedure implies a series of rituals and cultic performances, which,

however, are not fixed. The signs, in particular the eclipse of the moon, need

to be interpreted and their exegesis determines the development of the “sub-

stitute king” performance.

66

Both are always a matter of discussion between

the king and his

ummânus and, in general, one can say that there is no one per-

formance of the “substitute king” completely similar to another. Many or

even all the

ummânus are involved, directly or indirectly, in the direction and

performance of the different phases and operations of the procedure. In a

broad sense, the entire Assyrian state is conditioned by the performance.

The “substitute king” plot is centred on the king’s identity or in the essence

of kingship. Two symbolic as well as spatial directions move towards or away

from this focus. On the one hand, the Assyrian king alienates himself from

the identity of the “king” through a series of purification rites (

bit rimki, bit

62 Lambert (1957, 1959); Wiggermann (1992: 141).

63 The preserved text describes the burial of a substitute and of some apotropaic figurines, see Wig-

germann (1992).

64 For a definition of this term, which indicates artisans and “scholars” who have reached a superior

level of expertise, see Nadali - Verderame (in press). In the Neo-Assyrian period, among the personnel re-

lated to cultic, mantic, and healing and prophylactic techniques, it seems that the title of

ummânu was

attributed to people mastering one or more disciplines, including that of the scribe and/or the “as-

trologer” (t

upšarru), the diviner (barû), the ritual operator (ašipu), the healer (asû), and the lamentation

priest (

kalû); see Parpola (1983), Verderame (2004). These are the senders of the letters and reports dis-

cussed here.

65 The letters written during the ritual are easily identifiable, because they are not addressed to the

king, whose name is banned, but rather to the “farmer”, the fake identity assumed by the king. For the

different occurrences of the substitute king, see Parpola (1983: xxii-xxxii) and Verderame (2004:

passim).

66 For example, a series of quadripartite variables determines if the eclipse affects the Assyrian king

or not. Among these variables is the division of the world, as well as of the moon’s circumference, in

four quadrants according to the cardinal points and four major areas: Subartu (= Assyria; N); Babylonia

(S); Elam (E); Amurru (W); see Parpola (1983: Appendix 3C). During the reigns of Esarhaddon and As-

surbanipal, the king of Assyria is king of Babylonia as well, or an Assyria crown prince is appointed in

Babylonia (Šamaš-šumu-ukin). This continually changing situation created exegetical problems, as for

example, where to enthrone the substitute. Consequently the solution or counter-action to the events

occurring in each case are reflected in the different performances of the “substitute king” procedure.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 318

[19]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

319

sala’ mê), which involves a spatial progression. He lives in seclusion, separat-

ed from the court, and mention of his name is banned. In fact, he takes the

identity of the “farmer”. On the other hand, the substitute moves towards the

king’s identity. Each action during the entire procedure is aimed at strength-

ening his association with the kingship and his assimilation of the king’s iden-

tity. In first instance, the substitute king is provided with royal

insignia (the

throne, the table, the weapon and the sceptre), which will be successively

burned and their ashes buried with the substitute. More importantly in the

identification process is the role played by the signs observed before and after

the eclipse.

67

The letter sent by Nabû-zeru-lešir,

ummânu of Esarhaddon, to

the latter describes some of these operations:

68

§13. To the ‘farmer,’ my lord: your servant Nabû-zeru-lešir. Good health to my lord!

May Nabû and Marduk bless my lord for many years!

I wrote down whatever signs there were, be they celestial, terrestrial or of mal-

formed births, and had them recited in front of Šamaš, one after the other. They (the

substitute king and queen) were treated with wine, washed with water and anointed

with oil; I had those birds cooked and made them eat them. The substitute king of the

land of Akkad took the signs on himself.

He cried out: “Because of what ominous sign have you enthroned a substitute

king?” And he claims: “Say [in] the presence of the ‘farmer’: on the eve[ning of the xth,

we were drinking w]ine. £allaja gave b[ribes] to his servant Nabû-[usalli] and meanwhile

he inquired about Nikkal-iddina, Šamaš-ibni, and Naiid-Marduk, speaking about up-

heaval of the country: ‘Seize the fortified places one after another!’ He is to be watched

(carefully); he should no (longer) belong to the entourage of the ‘farmer.’ His servant

Nabû-usalli should be questioned – he will spill everything. (

SAA X, 2)

The signs are considered charges of the divine assembly against the king. The

relevant omens observed before and during the performance of the “substi-

tute king” are consulted in the divinatory series and transcribed on separate

tablets. These omens are then recited by the substitute in front of Šamaš, the

sun, lord of justice and divination, as an act of self-accusation.

69

Then the “signs” are physically assumed, through the identity and fate of

the king, by the substitute. The very same tablets with the omens, taken from

the series, are woven into the substitute’s dress,

70

which is symbolically con-

sidered like a second skin. In the above-mentioned case, birds portending evil

67 In fact, while a specific moon eclipse was considered as forecasting the death of the king, all the

other signs in Earth and Heaven, being related, had to confirm this curse.

68 The letter is part of a group describing the oldest case (679 or 674 a.C.) of the “substitute king” in

the letter corpus, see Verderame (2004: §V.1)

69 The appeal for Šamaš’ judgement and the fictitious process of the accusation, as already seen, is

very typical of the anti-witchcraft incantations, see above.

70 «[

Concerning the s]igns [about which my lord w]rote to me, [after] we had enthroned him, we had

him hear them in front of Šamaš. Furthermore, yesterday I had him hear them again, and I bent down

and bound them in his hem. Now I shall again do as my lord wrote to me» ([… gis]kim.meš [

ša be-li iš]-

pur-an-ni [ina é] n[ú-š]e-ši-bu-šu-ni [ina] ma-har du[tu n]u-sa-áš-me-šú ù it-ti ma-li us-sa-áš-me-šú-ma aq-ta-da-

ad ina qa-an-ni-šú ar-ta-kas ú-ma-a tu-ra ki-i ša be-li iš-pur-an-ni ep-pa-[áš]; SAA X, 12: r. 1-11).

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 319

320

lorenzo verderame

[20]

omens have been observed and caught, then cooked and eaten by the substi-

tute and his “queen”.

The latter case brings forth a further element of identification, that is, the

substitute queen. Nothing at all is known about the “real” queen throughout

the entire substitute king procedure. In a few cases, a substitute queen or, bet-

ter, a woman accompanying the substitute as his partner in the ritual and to

his fate, is mentioned.

71

This woman is called

batussu (or batultu), which is a

general term for young girl rather than virgin, as has often been the transla-

tion. It is known that the king probably meets the girl before the ritual

72

and

this may point to an interpretation of the role of this figure in the dynamic

of the ritual. In fact, contact is the most powerful means of the transmission.

Yet, considering the relevance of the substituted, no contact of this type with

the substitute is recorded. Instead, indirect vectors aiming to transmit the

identity to the substitute are used and the

batussu may be one of these.

Among the means of transmission, contact by sexual means is deemed by far

the most powerful.

73

It is only a suggestion, but one could assume that the

contact of the real king with the

batussu, possibly of sexual nature, is assumed

to be a further bond for the substitute; although the

batussu acts as an ulteri-

or and powerful vector of the king’s identity.

Finally, the letter quoted herewith (§13) records an exceptional event. In

fact, the substitute king, besides questioning the

ummânus on the reason for

his enthronement, assists the king by denouncing a conspiracy plotted

against the king by £allaja.

74

This event opens up several questions as to the

fidelity of the substitute and his relation with the substituted, as well as the

71 In the “ritual tablet” (see above) the substitute is accompanied by an unmentioned person, as the

use of a plural pronominal suffix proves, «you shall bury their ashes at their head» (

di-[i]k-me-na-šú-nu ina

re-še-šú-nu te-qeb-ber), see Lambert (1957-58: 110 B 7).

72 Parpola (1983: 125).

73 For sperm as a means of transmission, see Mayer (1988: 154s.) and Maul (1994: 78).

74 See Verderame (2004: §V.1).

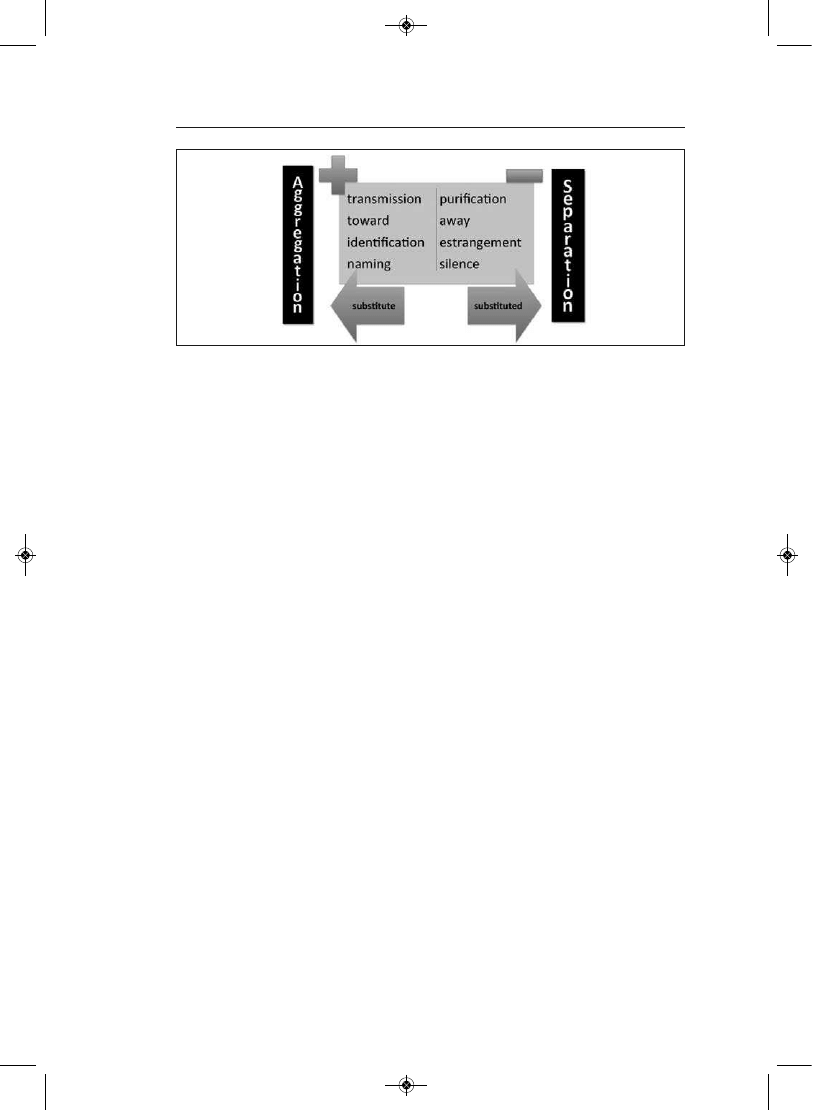

Fig. 1.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 320

[21]

the use of figurines, animals, and human beings

321

politically risky situation created by the performance of the “substitute king”

ritual. In a more theoretical plan, it indicates the complexity and the problem

related to agency in a ritual involving a human being as substitute.

75

Conclusion

This review of rituals shows the wide and different uses of substitutes. The

common role is that of a replacement of the person upon whom the action

of the rituals should have effect. Thus, the substituted could be a person to

be harmed or influenced, while in healing rituals the substitute fulfils the role

and fate of the sick man. The patterns and means of substitution are com-

mon and could be found in the different types of rituals.

While being one of the syntagms of the procedure in the simplest rituals,

in more complex rituals substitution and its elements are the focus of the pro-

cedure and are then amplified. In particular, the process of identification, by

which the identity of a person is transferred to the substitute through differ-

ent associative means, becomes more elaborated. At the apex of the pyramid,

the “substitute king” ritual could be considered the peak of substitution, with

a redundancy of identification actions.

In the latter rituals, substitution has a focus, the identity of the substituted,

and two main opposite forces moving towards (aggregation) or away (sepa-

ration) from this focus. While the substituted is alienated from his identity

and moves away from the ritual scene up to the point before annihilation, the

substitute moves toward the identity and plays the main role of the ritual. The

scheme in Fig. 1 shows how the opposing forces work.

The relevance of the substitute, and the substituted, is reflected in the pro-

portional increase in the following factors:

75 This is a theme that will be treated etensively in the forthcoming monograph, see fn. 62.

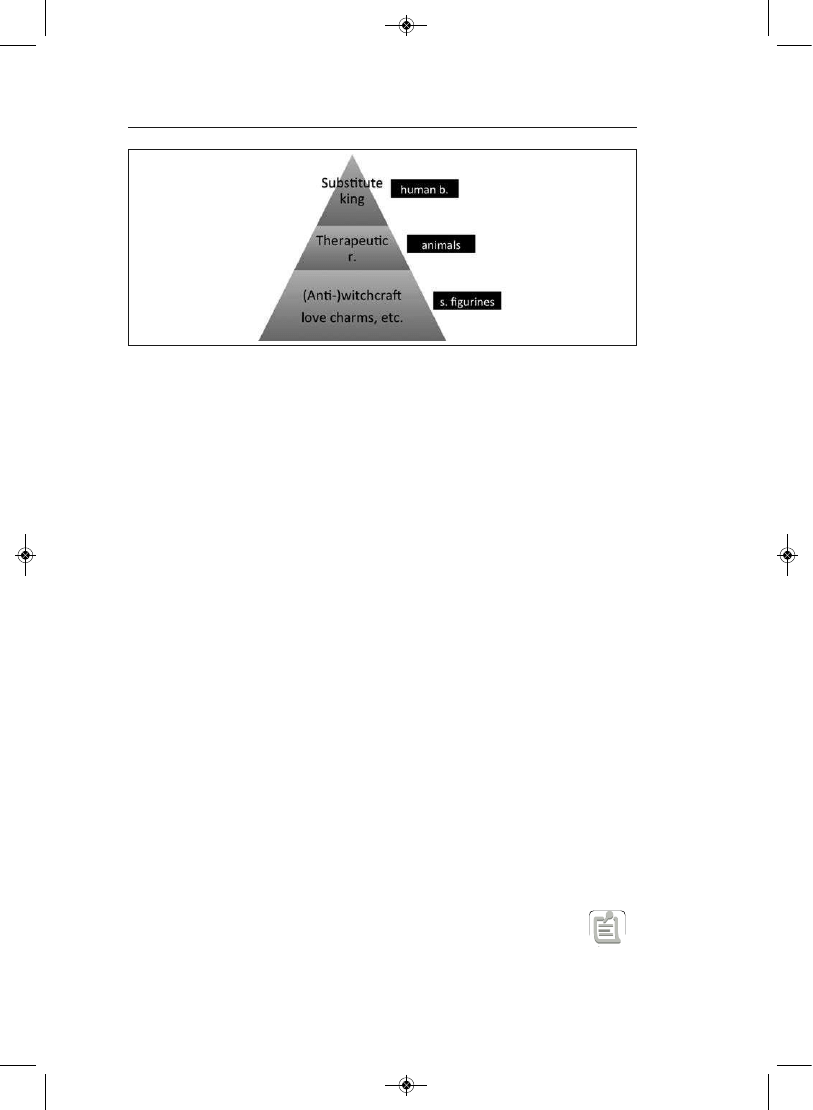

Fig. 2.

Rivista Studi Orientali Supplemento 2 2013_Impaginato 21/05/13 09:26 Pagina 321

322

lorenzo verderame

[22]

1. complexity of the procedure, which determines the participation and

coordination of

2. one or more cultic operators, which has an effect on

3. the cost of the ritual and the consequent

4. accessibility to these rituals, and

5. the symbolic power.

At the base of the pyramid are common, standard, cheap, and perhaps pop-

ular remedies. At the apex, there is an elaborate and flexible ritual, adapted to

circumstances by a group of learned experts, reserved for the head of the

state (the king), involving the killing of a human being.

Bibliografia

Abusch, T. (1987).

Babylonian Witchcraft Literature, Atlanta.

Abusch, T. - Schwemer, D. (2011).

Corpus of Mesopotamian Anti-witchcraft Rituals.

Ancient Magic and Divination 8/1. Leiden - Boston.

Biggs, R. D. (1967).

SÀ.ZI.GA. Ancient Mesopotamian Potency Incantations. Texts from

Cuneiform Sources 2. Locust Valley.

Capomacchia, A. M. G. - Verderame, L. (2011).

Some Considerations about Demons in

Mesopotamia. SMSR - Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni 77(2): 291-297.

Couto-Ferreira, M.E. (in press).

Agency, Performance and Recitation as Textual Tradition

in Mesopotamia. An Akkadian Text of the Late Babylonian Period to Make a Woman

Conceive, in M. de Haro Sanchez, Écrire la magie dans l’Antiquité – Scrivere la magia

nell’antichità. Proceedings of the International Workshop (Liège, October 13-15, 2011), Liège.

Daxelmüller, C. - Thomsen, M. L. (1982).

Bildzauber im alten Mesopotamien. Anthropos

77(1/2): 27-64.

Ebeling, E. (1931).

Tod und Leben nach den Vorstellungen der Babylonier. Berlin.

Faraone, C. (1991).

Binding and Burying the Forces of Evil: The Defensive Use of ‘Voodoo

Dolls’ in Ancient Greece. Classical Antiquity 10: 165-205.

Faraone, C. (1993).

Molten Wax, Spilt Wine and Mtilated Animals: Sympathetic Magic in

Early Greek and Near Eastern Oath Ceremonies. Journal of Hellenic Studies 113: 60-80.

Gasche, H. (1994).

Une figurine d’envoûtement paléo-babylonienne, in P. Calmeyer et al.,

Beiträge zur Altorientalischen Archäologie und Altertumskunde. Festschrift für Barthel

Hrouda zum 65. Geburtstag, Wiesbaden: 97-101, pl. XIII.

Furlani, G. (1940).

Riti Assiri e Babilonesi, Udine.

Haas, V. (1971).

Ein hethitisches Beschwörungsmotiv aus Kizzuwatna–seine Herkunft und

Wanderung. Orientalia 40: 410-430.

Hubert, H. - Mauss, M. (1902-03).