Journal of World Prehistory, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2000

The Not So Peaceful Civilization:

A Review of Maya War

David Webster

1

The first Maya encountered by Europeans in the early sixteenth century were

exceedingly warlike, but by the 1940s the earlier Classic Maya (AD 250–1000)

were widely perceived as an inordinately peaceful civilization. Today, in

sharp contrast, conflict is seen as integral to Maya society throughout its

history. This paper defines war, reviews the evidence for it in the Maya

archaeological record, and shows how and why our ideas have changed so

profoundly. The main emphasis is on the Classic period, with patterns of

ethnohistorically documented war serving as a baseline. Topics include the

culture history of conflict, strategy and tactics, the scope and range of opera-

tions, war and the political economy, and the intense status rivalry war of

the eighth and ninth centuries AD that contributed to the collapse of Classic

civilization. Unresolved issues such as the motivations for war, its ritual vs.

territorial aims, and sociopolitical effects are discussed at length.

KEY WORDS: Maya civilization; war; Maya archaeology; political economy; status rivalry.

INTRODUCTION

Early in the sixteenth century the Spaniards, already well established

throughout the Caribbean, began systematically to explore the mainland

of what we now call Mesoamerica. The first people they encountered were

Maya speakers, and the earliest contacts were typically bellicose. When

1

Department of Anthropology, 409 Carpenter Building, The Pennsylvania State University,

University Park, Pennsylvania 16802.

65

0892-7537/00/0300-0065$18.00/0

2000 Plenum Publishing Corporation

66

Webster

they landed at the large town to Campeche on the east coast of Yucatan

(Fig. 1), the Spaniards of the 1517 de Co´rdoba expedition were initially

received in friendly fashion by the local lord, then forced to beat a hasty

retreat when numerous heavily armed men began to assemble. Farther

south, near the town of Champoton, where they were driven ashore by

lack of water, de Co´rdoba’s men were not so lucky. Apparently forewarned

of their approach, large number of Maya launched a morning attack. As

Bernal Diaz (1963, p. 23) reported,

Once it was daylight we could see many more warriors advancing along the coast

with banners raised and plumes and drums. . . . After forming up in squadrons

and surrounding us on all sides, they assailed us with such a shower of arrows and

darts and stones from their slings that more than eighty of our soldiers were

wounded. Then they attacked us hand to hand, some with lances and some shooting

arrows, and others with their two-handed cutting swords.

The unfortunate shore party suffered the loss of 50 men before they could

escape to their ships. Licking their wounds, the explorers sailed back to

Cuba, where they reported things never before seen in the New World—

dense populations of farmers who grew maize and other crops, large towns

with well-built masonry buildings, garishly decorated stone temples filled

with idols and other objects of fine workmanship (including tantalizing

traces of gold) where priests officiated at blood sacrifices and wrote in books,

and great lords who could quickly muster up thousands of fierce warriors.

Two years later Hernan Corte´s, on the first stage of his fateful expedi-

tion that resulted in the overthrow of the Aztec empire, made landfall on

the coast of Tabasco, a region of Chontal Maya speakers. Here, at a place

called Cintla where other Spaniards had been received peacefully the year

before, he found thousands of warriors concentrated in anticipation of his

arrival. The omnipresent Bernal Diaz (1963, p. 65) described the Maya

battle array this way:

All the men wore great feather crests, they carried drums and trumpets, their faces

were painted black and white, they were armed with large bows and arrows, spears

and shields, swords like our two-handed swords, and slings and stones and fire-

hardened darts, and all wore quilted cotton armor.

Fierce battles ensued with these Tabascan hosts, whose commanders sued

for peace only when Spanish cavalry charges proved irresistible. In subse-

quent parleys Corte´s discovered that the assembled forces represented eight

different ‘‘provinces’’ (large political units of some sort) and that their

leaders used painted books to keep track of their various contingents.

Newly victorious in Mexico, Corte´s in the mid-1520s dispatched his

lieutenants to subdue the Maya of highland Chiapas and Guatemala. There

they encountered impressive conquest states such as that of the Quiche´,

whose noble lineages ruled from well-fortified elite centers perched on

A Review of Maya War

67

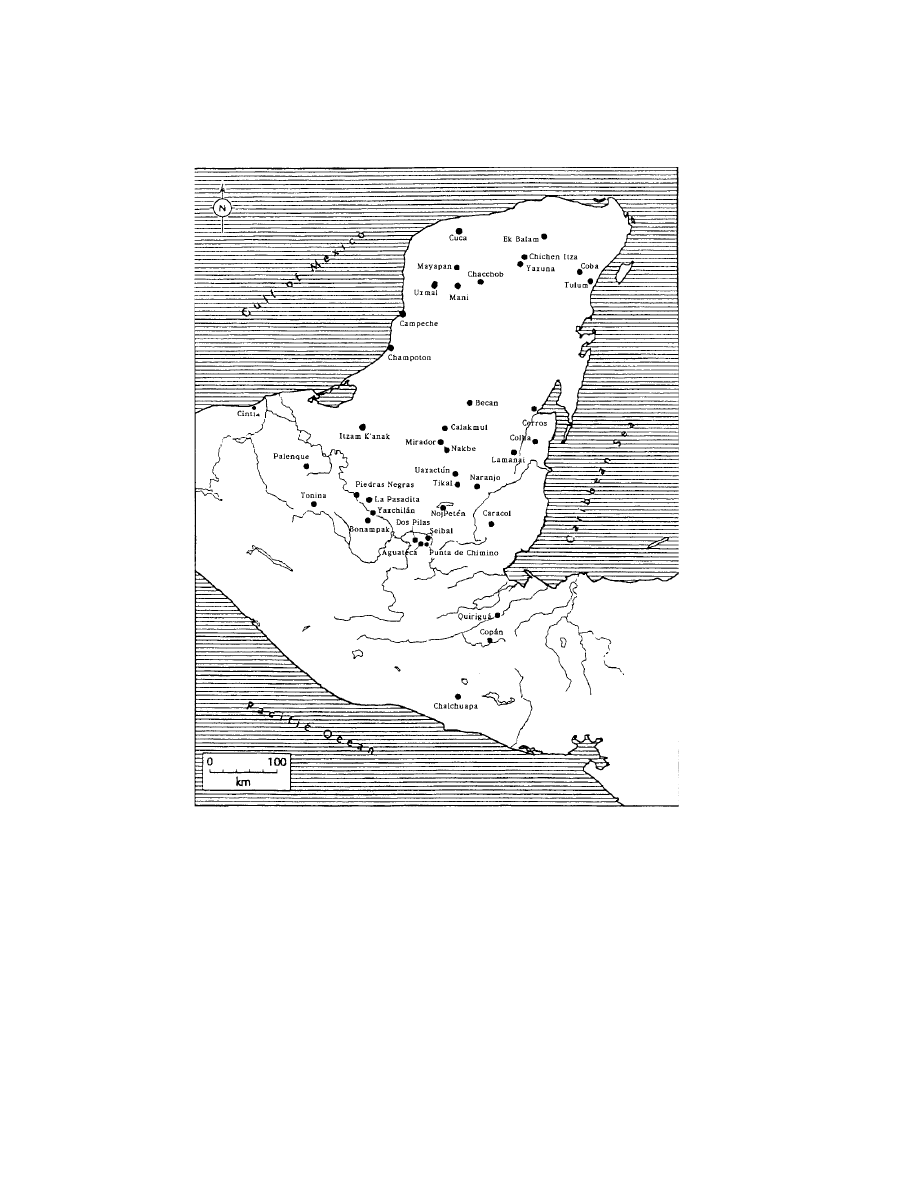

Fig. 1. Map of the Maya region of Mesoamerica showing the sites mentioned in the text.

68

Webster

ridges or escarpments, and who strongly resisted the invaders (Fox, 1978).

Apparently the sixteenth century Maya, while certainly not militarists on

a par with their highland Aztec contemporaries, were everywhere exceed-

ingly belligerent.

CONCEPTIONS OF MAYA WAR

Given participant accounts such as those of Corte´s, Bernal Diaz, and

many others, Mayanists long ago might reasonably have made the uniformi-

tarian assumption that all this was just the tip of the iceberg—that, as in

virtually all other early complex societies, war was an integral part of the

larger Maya cultural tradition from its beginnings. Instead, our conceptions

of Maya warfare have undergone a series of sudden and rather perverse

shifts. Early nineteenth century explorers such as John Lloyd Stephens and

Frederic Catherwood speculated that the ancient people who had inhabited

the ruins of Guatemala and Mexico, like other great civilizations, were

dominated by kings and warriors (Stephens, 1949). By the 1940s, however,

the Classic Maya (AD 250–800) had achieved the singular reputation of

being the only nonindustrial civilization not plagued by war and conflict,

despite the fact that warriors, weapons, and captives or sacrificial victims

were prominently displayed in their art. At this time it was widely believed

that Classic Mesoamerica more generally enjoyed peaceful conditions and

that such warfare as occurred was devoted to the capture of sacrificial

victims (Means, 1977). For reasons not well specified, these peaceful Classic

theocracies were subverted or degraded by Postclassic peoples, leading to

the violence and conflict the Spaniards encountered.

This was still the orthodox perspective, with some important dissenters

such as Robert Rands (1952) and Michael Coe (1962, 1966), until the early

1970s, at least with regard to the Maya. When I wrote my dissertation on

Maya war (Webster, 1972) there was only a sparse, scattered, and mostly

desultory literature on the subject. Today, in a startling turnabout, warfare

is all the rage. The Maya are often portrayed as compulsively warlike, and

warfare is a ubiquitous theme in books and journals. The impetus for this

new interest comes mostly from decipherments, as we shall see shortly,

and only a few field projects have been specifically designed to investigate

Maya war. I carried out one of the first (Webster, 1979), and similar research

has since been undertaken in the Dos Pilas region on the basis of original

work by Stephen Houston (1987, 1993; Demarest et al., 1997; Inomata,

1997) and at Yaxuna´ in northern Yucatan (Freidel et al., 1998; Suhler and

Freidel, 1998).

A Review of Maya War

69

CHRONOLOGY OF MAYA CIVILIZATION

Maya culture history is conventionally broken down into the following

time periods (slight variations on this chronology are preferred by some

Mayanists).

Paleoindian period

Before 7000 BC

Archaic period

7000–2500 BC

Early Preclassic period

2500–1000 BC

Middle Preclassic period

1000–400 BC

Late Preclassic period

400 BC–AD 250

Early Classic period

AD 250–600

Late Classic period

AD 600–800

Terminal Classic period

AD 800–1000

Postclassic period

AD 1000–approximately 1517

Contact/Colonial periods

Begin approximately AD 1517

Overturning the conventional wisdom of only a few decades ago, ar-

chaeologists have documented warfare over much of this range, beginning

with destruction levels, mass burials, and fortifications from Middle and

Late Preclassic times. War-related imagery is found in Early Classic art,

but most significant for this paper are the Late and Terminal Classic periods,

during which the number of centers and polities multiplied rapidly, regional

populations peaked, art and inscriptions were most abundant and wide-

spread, and Long Count dates provide an extremely detailed chronology.

As just noted, the nature of Classic warfare has long been an extremely

controversial issue.

Widespread disruption of Classic polities and demographic decline

occurred in the central and southern Lowlands roughly between AD

790 and 900 AD (a process usually labeled the Classic Maya ‘‘collapse’’).

There followed a long Postclassic interval during which polities were

most numerous and vigorous in the northern Lowlands. Postclassic

warfare has long been acknowledged on the basis of archaeological

evidence (e.g., the walled centers of Tulum and Mayapa´n), art (e.g., the

murals at Chiche´n Itza´), and, finally, indigenous oral and written histories

that emphasize struggles for supremacy among great families and factions,

centered especially on the successive regional capitals of Chiche´n Itza´

and Mayapa´n (e.g., see Marcus, 1992a). Many older Mayanists blamed

destabilizing and degrading Mexican or Mexicanized Maya influences

for the character of Postclassic conflict. Finally, there is the abundant

Contact/Colonial ethnohistoric evidence that is generally seen to reflect

a continuation of earlier Postclassic behaviors and beliefs. Like Maya

civilization itself, warfare changed dramatically through time in its inten-

sity, purposes, and cultural manifestations.

70

Webster

GOALS OF THIS PAPER

My main purpose here is to provide a necessarily condensed overview

of what we presently know or can reasonably infer about Lowland Maya

warfare, and some of the reasons why there have been such pronounced

shifts in our perceptions of it. A second concern is to set Maya war in its

larger environmental, historical, social, and comparative contexts, so that

we can properly understand its significance. A final purpose is to address

unresolved issues concerning the motives, conduct, and effects of Maya war,

about which I express my own opinions. I make no pretense of providing a

complete bibliography. Much of the material presented is culled from my

own earlier writings on all these subjects (Webster, 1975, 1976a, b, 1977,

1979, 1993, 1998, 1999a). The main emphasis is on Late and Terminal Classic

war in the central and southern Maya Lowlands, a topic that pervades the

current literature. Well-described Contact and Colonial period war provides

a point of departure, and asides are directed to the Preclassic Maya and

the wider ethnographic and historic records.

LANDSCAPE AND ENVIRONMENT

For thousands of years Maya speakers have occupied a vast region of

eastern and southern Mesoamerica that altogether measures about 324,000

km

2

(Fig. 1). Although this homeland lies entirely in the tropics there is

great variation in topography, climate, and vegetation. On the south, in

parts of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, lie the Maya

Highlands, at elevations from 800 to over 4500 m. More important for our

purposes are the Maya Lowlands, which cover about 250,000 km

2

. Because

of their lower elevations these lowlands are typically hotter and often more

humid than the highlands. Precipitation is strongly seasonal, with a general

dry season extending roughly from January to May. Annual rainfall in the

western Lowlands or in parts of Belize, where there are typically no rainless

months, can be as high as 4000 mm. In stark contrast, northwestern Yucatan

receives only about 500 mm annually. All regions are prone to striking

yearly variations and droughts are common. Measurements reported by

Lundell (1937, p. 6) over a 10-year period for the ancient Maya heartland

of Guatemala’s northern Pete´n region averaged 1762 mm but ranged from

990 to 2369 mm.

Some parts of the northern Lowlands are habitable year-round only

where natural collapse features (cenotes) expose the subsurface water table

or where deep wells or artificial water storage facilities can be constructed.

Wherever rainfall is abundant, especially in the south, east, and west, dou-

A Review of Maya War

71

ble- or triple-canopy, semideciduous tropical forests dominate recently un-

disturbed upland zones (of course virtually all forest is a human artifact),

interspersed with lower-lying bajos (seasonal or permanent swamps) and

grassy savannas. Northern forests tend to be lower and more thorny and

scrubby than the more well-watered southern ones, and conifer forests are

found at some high elevations, as in the Copa´n Valley of Honduras.

Much of the northern Yucatan Peninsula is a vast limestone shelf

that lacks substantial surface drainage. Large rivers concentrated along its

eastern, southeastern, and western margins provide routes of communica-

tion, but only a few are navigable for great distances, especially those in

Belize and the lower and middle reaches of the Usumacinta, Grijalva, and

Candalaria systems. A chain of large lakes just south of Tikal in northern

Guatemala was at the core of the Itza´ kingdom in 1697.

Many people who visit archaeological sites in the Maya Lowlands

come away with the impression of an exceedingly flat landscape, but the

topography is actually quite variable. The Maya Mountains in Belize rise

to elevations of over 1100 m, and the landscape in the heartland of Classic

Maya civilization around Tikal is quite hilly. Copa´n, on the southeast, is

located in a well-defined river valley surrounded by peaks as high as 1400

m. Around Piedras Negras, where I have recently been working, the highest

elevations are only several hundred meters, but the landscape is broken

up by extremely rugged karst features, including escarpments and conical

hills with very steep slopes.

Despite their locally distinctive settings, almost all ancient Lowland

Maya centers and polities were at elevations below 600 m (Tonina´, at 900

m, is the highest), and all shared basically the same set of staple cultigens,

most notably maize, beans, and squash, along with a wide variety of less

important plant species. Well-drained upland soils were (and are) most

attractive to farmers using simple hand tools, but they are typically thin,

fragile, and prone to nutrient depletion and erosion when cleared of natural

vegetation. Soils can be quite diverse over very small areas, however, and

the history of land use in a region was often extremely complex and had

major demographic and political consequences [e.g., see Sanders (1977)

for a general overview and Wingard (1996) for a Copa´n example].

Several features of this Lowland environment are closely related to

the conduct and motivations of war. There were strong seasonal constraints

on certain kinds of conflicts. Comparatively few physical barriers impeded

movement across the landscape, nor is it highly compartmentalized. Re-

source zones were fairly redundant compared to the highland regions of

Mesoamerica, and because there was no effective vertical zonation of ag-

ricultural production, there were few incentives to conquer or control zones

of different altitudes. Nor, as in the Highlands, were there concentrated

72

Webster

mineral resources such as obsidian or metals that were objects of competi-

tion (exceptions include the salt-producing locales in the coastal lagoons

of northern Yucatan). Agricultural production, fundamental to agrarian

economies, was and is today locally prone to shortfalls due to uncontrollable

risks such as fires, droughts, storms, and insect infestations and is also

threatened in the long term by human-induced deforestation, soil depletion,

and erosion. Local soil variation creates ‘‘patchy’’ production and risk

effects, thus inviting local competition. Poor harvests, as we will see, were

linked to ethnohistorically documented wars. Finally, on the ideological

level, the dramatic seasonal transformations, along with unpredictable ag-

ricultural crises, profoundly influenced the Classic Maya worldview, in

which death, regeneration, and the control of disorder and chaos were

major themes.

DEFINING WAR

Before going on I should make clear exactly what I think constitutes

war, which tends to be an underspecified category of human behavior

in the anthropological literature. I define war as planned confrontations

between organized groups of combatants who share, or believe they share,

common interests. Such groups represent political communities or factions

that are prepared to pursue these interests through armed and violent

confrontations that might involve deliberate killing of opponents. Such

killing is seen as socially acceptable and even desirable (i.e., it is not murder).

Conflict may be initiated in many ways, but one of the participating groups,

usually the attacker, seeks to maintain the status quo or, more often, to

achieve an advantage in power relations. War so defined is not limited to

any particular kind of polity or society and may occur on any scale.

Two important things about this definition are the variety of behaviors

that it encompasses and that it grades into forms of violence that are not

socially sanctioned. Factions involved might be family members engaged

in an intracommunity feud, ambitious warriors and their personal followers

raiding for loot, or forces representing an entire community or polity (or

alliances of these). Acts of war may be directed against external enemies

but also can include civil wars, usurpations, and acts of lethal treachery

aimed at creating new political conditions. Illicit behaviors such as murder

may escalate into socially sanctioned feuding or rebellion. Two or more

political communities may be involved in protracted antagonism (warre in

Hobbes’s sense), or, as is frequently the case in nonindustrial societies, war

may coincide with a single campaign. In its more large-scale and conven-

A Review of Maya War

73

tional manifestations most participants are anonymous to one another and

combat is highly impersonal.

As we shall see, many of these considerations apply to the Maya.

WAR IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD

Despite its ubiquity among complex societies, war is difficult to docu-

ment archaeologically. We fortunately have many lines of evidence for the

ancient Maya, some very strong, others less so. Art (which most clearly

shows weaponry) and inscriptions are two obvious ones, and these are

discussed separately in a later section.

Fortifications

A few Postclassic fortifications such as the walls at Mayapa´n (Shook,

1952) and Tulum (Lothrop, 1924) have long been recognized (see also

Armillas, 1951). Subsequent research has documented more than 20 other

defensive systems, or at least defensible constructions, at large Maya centers

dating from Preclassic through Postclassic times. These typically consist of

one or multiple lines of barriers created by ditches, earthworks, and stone

walls, often originally strengthened with parapets and palisades of timber

or other perishable materials. In some cases fortifications were integral

to the original layout of a center [Mayapa´n and Chacchob (Pollock and

Stromsvik, 1935; Webster, 1979)], while elsewhere they were later additions

[Becan (Webster, 1976) and Cuca (Webster, 1979)]. The most fundamental

consideration seems to have been to defend the civic and elite residential

cores of centers [Uxmal (Kowalsk and Dunning, 1999) and Ek Balam (Bey

and Ringle, 1997)], although occasionally large, nucleated residential zones

and populations were protected, as at Mayapa´n. Extensive boundary de-

fenses were sometimes built to incorporate considerable amounts of hinter-

land [Tikal (Puleston and Callender, 1967)]. Naturally strong positions [e.g.,

the Punta de Chimino peninsula (Demarest et al., 1997) and the escarpments

at Aguateca (Inomata, 1997)] were improved by artificial constructions.

Under extreme threat ramshackle barriers were sometimes quickly erected

around previously undefended site cores, as at Dos Pilas (Houston, 1987,

1993; Demarest, 1993; Demarest et al., 1997).

Where they exist, fortifications tell us that particular centers were

threatened (if not actually attacked) and also hint at the scale of hostilities.

For example, the huge earthworks at Becan presented very impressive

vertical barriers and are 1.8 km in circumference. Obviously they were

74

Webster

designed to withstand determined assaults or sieges by large forces and

they served this purpose for hundreds of years after their initial construc-

tion, which most likely occurred at the end of the Late Preclassic. Some

archaeologists believe that the Punta de Chimino ditch and earthwork,

which protect a community with heavy Preclassic occupation, are equally

early (Houston, S., personal communication, 2000).

A little reflection shows, however, that no conclusions about war can

be drawn on the basis of the lack of fortifications for two reasons. First,

such an absence may be more apparent than real. Very flimsy defenses

were highly effective given Maya military capabilities, and few traces of

such constructions might survive or be initially recognized. The Petexbatu´n

region around Dos Pilas provides a case in point. In 1978 Arthur Demarest

(1978) cited the absence of fortifications there as indicative of a syndrome

of very constrained forms of warfare. Much earlier Ian Graham had ob-

served wall-like features at both Aguateca and Dos Pilas in the early 1960s

but apparently did not recognize their significance. Their full implications

finally became clear in the mid-1980s when Stephen Houston (1987, 1993)

mapped Dos Pilas and other walled sites in the region and made plans to

carry out a war-focused project there (never realized because permission

was not forthcoming). Ultimately and ironically, Demarest’s projects docu-

mented these defenses more fully and revealed episodes of very severe

warfare (Demarest et al., 1997; Inomata, 1997).

A second reason is that in many cultural traditions communities com-

monly are not formally fortified even where warfare is rampant; the Basin

of Mexico is a good Mesoamerican example (Hassig, 1999).

Settlement Distributions

Dispersed settlement in the form of small residential sites is found

around many Classic Maya centers and has often been singled out as

incompatible with patterns of intense warfare (e.g., see Rand’s comments

below). This is a weak argument, not only because the Maya clearly main-

tained such patterns in the face of serious conflicts, but also because it

occurred elsewhere as well [e.g., Japan (Farris, 1999) and Hawai’i (Kirch,

1984, 1990)].

At some centers where settlement is well documented there were

shifts in construction activity and occupation apparently related to unsettled

political conditions. For example, Mock (1998, pp. 114–115) notes that the

Colha population seems to have crowded around the central major groups

in the Terminal Classic, shortly before the center was briefly abandoned.

I know of no examples from Classic times (except when polities ultimately

A Review of Maya War

75

collapsed) of wholesale abandonment of dispersed sites and extreme nucle-

ation in the face of attacks. This is not to say that such evidence will not

appear. With better settlement samples and finer control of site chronolo-

gies I think we might detect situational establishment of boundary zones

or large-scale abandonment of small sites that relate to intense hostilities.

In some cases small outlying sites around major centers were walled, as in

the Dos Pilas region, or refuges were established, as at Aguateca.

Settlement research also sometimes reveals sudden shifts in ceramic

or other artifact forms. To continue the Colha example, after a brief hiatus

the center was reoccupied by Postclassic people using new artifact assem-

blages. Sabloff and Willey (1967) long ago maintained that similar data,

along with ‘‘foreign’’ iconographic elements, indicated invasions of foreign

invaders on the western peripheries of the Lowlands. Other Mayanists such

as Stuart (1995, p. 316) doubt that such invasions occurred.

Destruction Episodes

Maya centers as early as Middle Preclassic times show evidence of

large-scale, deliberate destruction of major architecture. As long ago as

the 1930s archaeologists uncovered palace contexts, as at Piedras Negras

(Holley, 1983), that seem to have been abruptly abandoned and destroyed,

but until recently these were not interpreted as war-related events. Current

research is turning up many such examples. At Aguateca the whole commu-

nity seems to have suffered from a violent attack by external enemies

(Inomata, 1997; Inomata and Stiver, 1998), while the destruction detected

at the recently excavated royal compound at Copa´n (Andrews and Fash,

1992) appears more likely to me to be the result of internal power struggles.

The Maya commonly ‘‘decommissioned’’ or ‘‘killed’’ important struc-

tures by wholly or partially destroying them, especially when they were to

be covered with later buildings, and such episodes have no implications

for war. Many so-called ‘‘termination’’ rituals, however, especially seen in

light of other evidence, such as associated mass burials, were apparently

the result of violent desecration of temples, elite residences, and other

buildings and monuments by enemies [e.g., at Yaxuna´ during the Early

Classic (Freidel et al., 1998; Suhler and Freidel, 1998)].

Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish ritual termination from outright

violence. For example, William Fash (1989) determined that fac¸ade sculp-

ture on elite Str. 9N-82C at Copa´n was deliberately burned, but the building

stood long after this event. E. Wyllys Andrews and his colleagues discovered

that the lintel of a major structure in the nearby royal compound had been

76

Webster

purposefully burned to collapse the building. These seem like two very

different acts to me.

Skeletal Remains

From very early times the Maya kept human remains for various

reasons, including as trophies of dead enemies (as well as ancestors), a

practice that is shown in Classic art and documented ethnohistorically (see

below). Tombs and caches commonly yield disarticulated heads or other

body parts or central burials lacking such parts. Mass burials of men of

military age, plausibly related to warfare or subsequent sacrificial ceremon-

ies, have been recovered from Late Preclassic contexts, as at Chalchuapa

(Fowler, 1984), and the practice continued in Classic times as well. Even

more interesting are the multiple burials of men, women, and children

found at Tikal (Laporte and Fialko, 1990), Yaxuna´ (Suhler and Freidel,

1998), and elsewhere that are interpreted as the remains of royal/elite

families deposed and massacred by external or internal enemies. A dramatic

example is the ‘‘Skull Pit’’ at Colha, which yielded the severed heads of

20 adults and 10 children of both sexes (Mock, 1998). Skulls had still-

articulated vertebrae and apparently the skin was flayed from the faces of

some victims. Following this event the building in which the skulls were

interred was destroyed, as apparently was much of the rest of Colha.

Unfortunately no large skeletal series exists that exhibits more broadly-

distributed patterns of possible war-related trauma. One of the best-ana-

lyzed ones, from Copa´n, in fact shows few or no such injuries (Story, 1992,

1997; Whittington, 1989), although given the paucity of war references in

the inscriptions of that center and its comparatively isolation far from the

major arenas of conflict, this is not surprising.

Most of the kinds of evidence cited above, of course, relate primarily

to the intense, destructive, and violent phases of war. The family feud, the

small-scale raid, or the elimination of political enemies by treachery all

would leave very few and probably ambiguous traces, and we would be

very lucky to detect them. Indirect evidence, such as the regionalization of

ceramic complexes in the Late Classic (Ball, 1993), reflects the fragmenta-

tion of the political landscape and, by implication, both the background

conditions for conflict and the effects of it.

Fortunately, Contact period war is richly documented and serves as a

convenient benchmark from which to interpret patterns of earlier Classic

warfare.

A Review of Maya War

77

WARFARE AND SOCIETY IN THE CONTACT PERIOD

Various Spaniards left eyewitness or second-hand accounts of conflict

in Yucatan for the period from 1517 to 1546, when the colonial capital of

Merida was finally established. The most famous of these is Landa’s Rela-

cio´n de Las Cosas de Yucatan, based heavily on information provided by

three Maya informants of high rank. Indigenous Maya scribes produced

post-Conquest documents of various kinds that recounted wars fought both

before and after the Spaniards arrived. Worth noting is that the last indepen-

dent Maya kingdom—that of the Itza´ in northern Guatemala—was con-

quered only in 1697, so we have records of intermittent campaigns and

protracted animosities over almost two centuries (Jones, 1998).

Sociopolitical Background

Northern Yucatan, which we know best, was populated by a population

variously estimated as between 600,000 and 2,300,000 Maya just prior to

the conquest (I prefer the lower range). Overall population densities were

quite low (less than 20 people per km

2

), consistent with ethnohistoric ac-

counts of extensive systems of agriculture (but see McAnany, 1995; Fedick,

1996). The most basic political unit prior to the Spanish conquest consisted

of a small segment of territory ruled by a noble called a batab, assisted by

various lesser officials and priests. Households of batabs (for simplicity’s

sake I use the English plural form throughout this paper, rather than the

Maya -ob, etc.) and other nobles and rich families formed the central

community of the polity, with dispersed households of commoners scattered

over the surrounding countryside. Spatial delimitation of the batabship was

probably not strictly territorial in the modern sense but, rather, extended

to the most distant plots of lands (themselves often very carefully marked)

habitually cultivated by members of the polity, land being the principal re-

source.

Details concerning the precolumbian batabship are sparse, but ac-

cording to Matthew Restall (1997) it was the direct antecedent of the

abundantly documented post-Conquest cah, which retained many facets of

earlier organization. The cah was a territorial, political, and social unit

essential to Maya identity. Within the cah some resources were held in

common and families were organized into patrilineages (chibal). In any

given region or batabship there were families of distinguished lineage who

collectively formed a noble class and dominated the highest offices. Nobles

set much store by their lineage name and history, and maintained ties with

high-raking maternal relatives, as Landa also reports for preconquest times.

78

Webster

The elaborate households of Conquest period nobles were supported

by labor and goods produced by commoners, who formed the vast majority

of the population. Nobles also owned cacao plantations and engaged in

long-distance trade, both enterprises partly underwritten by the labor of

slaves. Some nobles also asserted separate descent from commoners and

were hedged about with an elaborate etiquette that emphasized their privi-

leged rank. About 30 great families, most notably the Xiu, the Cocom, the

Chel, and the Pech, dominated events in various locales, and some of them

were traditional enemies for centuries, their great power struggles central

to Yucatecan historical narratives.

More controversial is political organization above the level of the

batabship in the early sixteenth century. The ethnohistorian Ralph Roys

(1943, 1957) identified 16 ‘‘provinces’’ of three basic kinds (see also Marcus,

1992a, 1993). The simplest consisted of loose alliances of batabships whose

leaders were generally not related to one another and whose cooperation

was based on mutual self-interest. A more cohesive arrangement involved

batabships whose rulers were members of the same lineage. The most

centralized provinces were dominated by an individual called a halach uinic

(‘‘true man’’) who was a batab in his own right and to whom other batabs

were subject. An example is Mani, which probably had a population of

about 60,000 people and which was ruled from a central capital of that

name by a halach uinic of the Xiu lineage. In token of his supremacy the

halach uinic also used the title ajaw (‘‘lord’’ or ‘‘king’’—also frequently

spelled ahav).

Restall believes, in contrast to Roys, that ‘‘provinces’’ are largely illu-

sory, that there was little effective centralization above the level of the

batabship, and that halach uinic was an honorific title conferred on a particu-

larly dominant batab who wielded comparatively little unilateral authority.

To the extent that provinces existed, their boundaries, like those of the

constituent batabships, were fluid and frequently contested. Supporting

Restall’s argument is the fact that the Spaniards did not describe royal

palaces among the sixteenth century Maya (i.e., residential establishments

much more impressive than those of ordinary nobles or rich people). In

any case, it is clear that some halach uinics were powerful men who enjoyed

wide support and who could mobilize many followers, and a central theme

of Maya books and oral traditions is the great precolumbian confederations

dominated by the centers of Chiche´n Itza´ and Mayapa´n. My opinion is

that the Contact period Maya present us with a reasonable approximation

of what Freid (1967) called a ‘‘stratified society’’—i.e., one characterized

by stratification but without effective development of political centralization

or those institutions that strongly reinforce this kind of social order (see

also Sanders, 1989, 1992).

A Review of Maya War

79

Contact Period War

During early battles with the Spaniards Maya warriors exhorted one

another to kill or capture the enemy ‘‘calachuni’’ (as Bernal Diaz wrote

it). It seems safe to assume, therefore, that halach uinics commonly led

native contingents in the field, an interpretation consistent with Corte´s’s

assertion that he fought warriors from eight provinces. Batobs were military

leaders as well, but the most specialized commanders were nacoms, war

chiefs elected for 3-year terms from among the accomplished warriors of

the most important towns. Landa reports that nacoms were expected to

withdraw from normal life and remain celibate for the duration of their

terms and that, during an important annual festival called Pacum Chac,

they were carried like idols to prominent temples, where offerings were

made to them and war dances were performed. Notable braves called

holcans were recruited and subsidized as a core military force, and these

men often caused trouble even in the communities that paid them, especially

after hostilities ceased.

Even allowing for expectable Spanish exaggeration of enemy numbers,

it is clear that very large contingents of troops, certainly numbering in the

thousands, could be quickly mobilized. I believe that this indicates a militia

pattern of recruitment—i.e., adult men in general were prepared to serve

as warriors and kept their own weapons in their homes. The ‘‘squadrons’’

observed by Bernal Diaz probably represented contingents drawn from

particular batabships or cahs. Such militias, of course, would be most effec-

tively mustered for defensive rather than offensive purposes. None of the

first-hand accounts tells us much about how, or even whether, warriors

acted as disciplined formations in battle, but a standard tactic seems to

have been to try to eliminate enemy captains as noted above.

Although warriors were often gorgeously attired, their arms were made

of wood, stone, bone, hide, and fiber and, so, were primitive by European

standards (Landa mentions copper ‘‘hatchets’’ but I find no descriptions

of their actual use). Long-distance weapons included atlatls, slings, and

bows, and these were supplemented by various close-quarter weapons such

as thrusting spears and sword-like wooden implements edged with sharp

stone blades. Shields, padded cotton armor, and helmets of wood or other

materials provided protection.

Historically documented battles usually took place in the open, but

the Maya were also adept at throwing up stockades, barricades, and other

field defenses. Although many settlements were undefended, the Maya

had a long tradition of fortifications, many of which are archaeologically

detectable. Hernan Corte´s (1986, p. 371) described one he saw in 1525

this way:

80

Webster

This town stands upon a high rock: one side of it is skirted by a great lake and the

other by a deep stream which runs into the lake. There is only one level entrance,

the whole town being surrounded by a deep moat behind which is a wooden palisade

as high as a man’s breast. Behind this palisade lies a wall of very heavy boards,

some twelve feet tall, with embrasures through which to shoot their arrows; the

lookout posts rise another eight feet above the wall, which likewise has large towers

with many stones to hurl down on the enemy . . . indeed, it was so well planned

with regard to the manner of weapons they use, they could not be better defended.

Although primitive by European standards, such constructions as Corte´s

notes were quite effective given the ‘‘paleotechnic’’ level of Maya arma-

ment, especially the lack of artillery, and were particularly useful against

surprise raids, a favorite form of attack.

Landa several times asserts that wars (he might better have said cam-

paigns) were of short duration, particularly because of the resistance of

the noncombatant men and women who necessarily had to haul provisions

on their backs, given the lack of beasts of burden or wheeled vehicles.

Human porters had to eat as well as warriors, so such a transport strategy

was quite inefficient. Only where water transport was available, particularly

along the coasts, could what Hassig (1992) calls the ‘‘friction of distance’’

of Precolumbian warfare be overcome, but even canoes lacked sails and

had to be paddled. While operating in enemy territory there were only two

options for war parties: carry your own food or live off the land—i.e., the

crops or food stores of your opponent. This same restriction made pro-

longed sieges difficult. Protracted campaigns involving sizable forces were

probably most feasible when mature crops of the enemy either were still

in the fields or had just been harvested.

Battles themselves were to some degree ritualized and choreographed,

as no doubt were the preparations for them. If Spanish descriptions can

be trusted, ritual paraphernalia found in a camp hastily abandoned by an

Itza war party in 1631 included an ‘‘altar,’’ priestly clothing, incense burners

along with the copal incense burned in them, wooden images, and three

‘‘idols’’ in the form of animals (Jones, 1998, p. 50).

Most war captives were enslaved, but distinguished male captives were

usually sacrificed and body parts such as mandibles were kept as trophies.

In Mesoamerican cultures generally there was a meritocratic dimension to

success in war, most comprehensively documented for the Mexica. Nacoms

and holcans apart, we do not know whether ordinary Maya warriors who

distinguished themselves on the battlefield could rise much in social rank,

but they were honored and feasted, and boasted of their accomplishments.

Postconquest documents reveal frequent antagonisms between cahs,

and most conflicts were probably fought between batabships, including

those putatively included in the same ‘‘provinces.’’ If halach uinics were

really as powerful as Roys suggests, then suppression of conflict among

A Review of Maya War

81

their batab constituents must have been one of their most important respon-

sibilities. As in highland Mexico, the northern Maya did not present a

common front against the European invaders. Jealousies among great fami-

lies and desire to preserve their prerogatives led some Maya factions to

ally themselves opportunistically with the Spaniards (Restall, 1998).

Pretexts for war included revenge, capture of slaves, and control of

trade routes and the sources of valued materials, especially salt, which was

obtained from many sites along the northern coast. Land was a major cause

of friction in postconquest cah documents, and quarrels over land incited

many pre-Spanish conflicts as well. Recurrent agricultural shortfalls due to

drought and other crises stimulated theft and trespass, which in turn trig-

gered hostilities between polities. To the extent that martial feats and

warlike personae were culturally valued, these in themselves encouraged

conflict.

We may safely attribute some features of Contact period warfare to

the earlier Classic Maya as well. Weapons were at all times sufficiently

simple that any handy Maya artisan could manufacture them from cheap,

commonly available materials, and learn to wield them, although elite

fighters probably possessed particularly handsome or symbolically charged

arms and were more adept in their use than the situational common soldier.

The one exception to this rule is large war canoes, which certainly were

used in Postclassic times and possibly also by the Classic Maya. Presumably

only leaders of high rank could afford to commission such vessels.

Other constants include the logistical limitations on the range and

duration of operations and the close relationship between ritual and conflict.

As in all complex agrarian societies, rulers and elites in both Contact period

and Classic societies made up only a tiny proportion of the population, so

any sizable contingents necessarily included commoners [see Webster (1985,

1998) and Hassig (1992) for extended discussions of these points]. Finally,

with very few exceptions, Maya war was carried out between culturally

similar, if not identical, antagonists. Despite such continuities, the ethnohis-

toric record must be used carefully as a guide to Classic Maya war, which

in many ways was highly distinctive.

CLASSIC MAYA WAR AND SOCIETY

Given all the Contact period evidence, we might well marvel at the

widespread consensus developed by the 1940s that the Classic Maya were

inordinately peaceful. Actually, the attitude among Mayanists was not so

much outright denial as embarrassed confusion. Sylvanus G. Morley, the

dean of Maya archaeology of the time, provides a good example. His

82

Webster

immensely popular and influential book The Ancient Maya (Morley, 1946)

contains a handful of short references to war. At one point he remarks

that there are no archaeological indications of wars or conquests associated

with the Maya collapse and that

Old Empire (i.e., Classic period) sculpture is conspicuously lacking in the representa-

tion of warlike scenes, battles, strife, and violence. True, bound captives are occasion-

ally portrayed, but the groups in which they appear are susceptible of religious, even

astronomical interpretation, and warfare as such is almost certainly not implicated.

(Morley, 1946, p. 70)

This comment strikes one today as rather odd because many of the monu-

ments now featured as evidence for Maya war were known at the time,

and earlier scholars such as the art historian Herbert Spinden (1913) had

identified images of weapons and ‘‘memorials’’ to ‘‘success in war’’ (Stephen

Houston has also pointed out to me that in the 1930s M. Jean Genet made

several decipherments related to warfare).

Ironically, just before Morley’s book went to press the famous murals

of Bonampak (Miller, 1986) were discovered; these more than any other

images contributed to the breakdown the ‘‘peaceful Maya’’ perspective. In

fairness to Morely, he went on to speculate that there were ‘‘civil wars’’

among Classic Maya polities and that captives pictured on monuments at

Tikal were slaves taken in warfare. In doing so he was not reasoning

primarily from the archaeological evidence but, rather, projecting ethnohis-

torically known patterns back into the past.

Sometime later J. E. S. Thompson (1954, p. 81) ventured that

I think one can assume fairly constant friction over boundaries sometimes leading

to a little fighting, and occasional raids on outlying parts of a neighboring city state

to assure a constant supply of sacrificial victims, but I think the evidence is against

the assumption of regular warfare on a considerable scale.

Thompson believed that Maya docility was deeply rooted in ‘‘character’’

or ‘‘personality traits.’’ He admired the living Maya as ‘‘. . . exceptionally

honest, good-natured, clean, tidy, and socially inclined’’—perfect exemplars

of ‘‘live and let live’’ except when provoked beyond endurance (Thompson,

1954, p. 131). Thus oppressive elite demands for too much labor and tax

at the end of the Classic period provoked a particular kind of warfare—

peasant revolts—that ultimately overthrew them.

Of course at this time neither Morely nor Thompson nor anyone else

could read noncalendrical Classic Maya hieroglyphs despite decades of

determined attempts at decipherment (Coe, 1992). Morley (1946, p. 262)

was originally convinced, like John Lloyd Stephens, that the inscriptions

recorded history, but later reversed his opinion:

The Maya inscriptions treat primarily of chronology, astronomy—perhaps one

might better say astrology—and religious matters. They are in no sense records of

A Review of Maya War

83

personal glorification and self-laudation, like the inscriptions of Egypt, Assyria, and

Babylon. They tell no story of kingly conquests, recount no deeds of imperial

achievement; they neither praise or exalt, glorify nor aggrandize, indeed they are

so utterly impersonal, so completely nonindividualistic, that it is even probable

that the name-glyphs of specific men and women were never recorded upon the

Maya monument.

More than anything else this presumed esoteric, ahistorical content of

the hieroglyphs, as the quote indicates, made the Maya seem unique, unlike

other civilizations. It heavily contributed to the then prevalent idea that

Maya polities were peaceful theocracies, dominated by priest-rulers who

presided over centers that were essentially vacant ceremonial places, built

and maintained by the devotion of common people (Becker, 1976)—a

charming and utopian vision to which much of the general public is still at-

tracted.

Not everyone neglected the topic of Classic period warfare, however.

Robert Rand’s (1952) dissertation was one of the very few lengthy consider-

ations of the topic. Rands (1952, pp. 5–6) observed that

some half dozen major types of evidence have been brought forward to support

the belief that the Classic Maya were non-militaristic. These include their art,

supposedly free of warlike motifs; their architecture and settlement patterning,

supposedly vulnerable to attack; their cultural homogeneity, supposedly incompati-

ble with intertribal warfare of the sort rampant in northern Yucatan a the time of

the Spanish Conquest; and the supposed existence of their religiously-oriented

culture and their national character or ethos dominated by strong tendencies to

moderation and orderliness.

Rands (1952, p. 64) believed instead that ‘‘evidences are strong for the

existence of fairly intensive patterns of warfare in the Classic Period,’’

especially when segments of polities ‘‘revolted’’ to establish their indepen-

dence. Even he, however, did not seriously buck the prevailing wisdom,

and took the position that insofar as their art suggested, Classic Maya

war was not, like that of the Inka and Aztecs, motivated by acquisition

of ‘‘tribute or territorial gain’’ (Rands, 1952, p. 188). Only when convincing

evidence of early fortifications emerged did some Mayanists begin to

think that something more serious might be going on, and even so, not

until the inscriptions began to be comprehensible did the tide of opinion

finally turn.

The Sociopolitical Context of Classic Maya War

Despite the continuities already discussed between the Contact period

Maya and their Classic predecessors, we must also take into account many

differences, as well as acknowledge serious gaps in our understanding of

Classic society. Here I provide only a brief overview, stressing those features

84

Webster

most relevant for war; for more extensive discussions see Sabloff and Hen-

derson (1993) and Lucero (1999). The principal concern is the Late Classic

and Terminal Classic periods, during which evidence for war is very compel-

ling. But first we must backtrack for a moment.

Preclassic Background

We now know that large centers and extensive polities, along with

many other features of the Lowland Maya Great Tradition previously

attributed to Classic times, were actually present much earlier. By 300 BC

Komchen in northeastern Yucatan, El Mirador and Nakbe in the northern

Pete´n of Guatemala, and Cerros in northern Belize were all thriving places

(Ringle and Andrews, 1990; Matheny, 1986; Hansen, 1998; Freidel, 1986a).

Unfortunately we have no comprehensible texts for this early period, nor

do we yet have a good grasp of settlement distributions, economic patterns,

or regional demographic scales. Although Mayanists debate whether these

early polities had social and political institutions comparable to those of

Classic times, there was obviously a considerable degree of political central-

ization, massive use of labor for construction projects, and rituals and

associated symbols that generally prefigure later royal ones.

Interestingly, many of these large centers were abandoned at the end

of the Late Preclassic period and never substantially reoccupied. Presum-

ably their former inhabitants contributed to the growth of Tikal, Calakmul,

and other great capitals that were dominant during the Early Classic.

Whether warfare was associated with this upheaval and population disloca-

tion is unknown, but as we have already seen, destruction episodes, mass

graves of probable war victims, and very large fortifications do clearly date

to Late Preclassic times.

The Classic Period Political Landscape

In the late 1950s epigraphers first identified ‘‘emblem glyphs,’’ and

some 40 or more are now known (Mathews, 1991; Marcus, 1992b). These

glyphs are not toponyms but, rather, occur as parts of titles that are also

associated with personal names. The referent is not a place per se, but a

‘‘holy lord,’’ or king, presumably associated with a political unit designated

by the emblem glyph, and by extension they probably refer to a whole

polity and/or its dynastic line (Culbert, 1991, pp. 140–144; Stuart, 1993, pp.

325–326, 1995, p. 257). Early emblem glyphs appeared in the fifth century

but they are most numerous after AD 650. Unfortunately not all major

A Review of Maya War

85

centers can be associated with an emblem glyph, some have more than

one, and some glyphs are shared by more than one center. Nevertheless,

emblem glyphs have proved invaluable in understanding the Maya political

landscape, especially the war texts to which we will turn shortly.

By the seventh century there were hundreds of large and small Maya

centers, most concentrated in the central and southern Lowlands. Some of

these, in regions such as northeastern Guatemala or northern Belize, were

within a day’s walk of one another. Elsewhere distances were greater, but

even Copa´n, perhaps the most isolated of first-rank centers, is only a 3-

day walk from its closest neighbor, Quirigua´.

Centers and Polities

Mayanists long ago recognized that Classic Maya centers differed from

urban places in other parts of the ancient world, and also from Mesoameri-

can cities such as Teotihuaca´n and Tenochtitlan. At their cores lie impres-

sive masonry temples, ball courts, royal palaces, ceremonial causeways,

great plazas containing carved and inscribed altars and stelae, and some-

times artificial reservoirs (Houston, 1998). Such conglomerations of large

architecture may cover as much as several square kilometers, as in the

case of Tikal, but most are much smaller—typically less than one square

kilometer. Considerable numbers of people inhabited these site cores, but

not in anything like the urban densities found in highland Mexico or at

the Postclassic Maya city of Mayapa´n. Instead, residences of elites and

commoners radiate out from the central precincts, with settlement usually

becoming more dispersed with distance. Around a few centers such as

Copa´n there are impressive residential precincts that approach urban densi-

ties over very small areas (Webster et al., 2000), and the same appears true

for the newly mapped peripheries of Palenque.

Most Mayanists agree that centers were essentially the establishments

of rulers and their immediate families and retainers, less differentiated

from their rural hinterlands than many Old World cities, particularly in

terms of their economic functions. Sanders and Webster (1988), following

the urban anthropologist Richard Fox (1977) call them regal-ritual centers

and envision them as the hyptertrophied household and court facilities of

hereditary kings, many of which acquired their forms over centuries (see

also Ball and Tasheck, 1991). Rule emanated from these centers, at which

was concentrated all of the necessary apparatus of royal display and sym-

bolic presentation. Lesser elite people often lived in elaborate households

of their own, as most clearly seen at Copa´n.

If centers, at least the largest ones, were capitals, how extensive were

86

Webster

their polities? Most Mayanists would probably agree that the most durable

political unit was a single center with its resident dynasty surrounded by a

small hinterland—say, on average, 2000–3000 km

2

in area. Some Mayanists

have called such small polities ‘‘city-states,’’ but most of them were probably

neither very urban nor very state-like in organization. A few ancient centers,

especially Tikal, might have been considerably larger even early on, and

dominated nearby neighbors of considerable size. What Mayanists argue

about is the ability of ambitious rulers to create what Martin and Grube

(1995) call Maya ‘‘superstates’’—polities in which one powerful ruler con-

trolled, especially through successful warfare—many subordinate polities

and kings.

As we shall see below such attempts were clearly made. There is no

question that during the sixth and seventh century Tikal and Calakmul

were centers of enormous political and military gravity which attracted or

otherwise drew other dynasties into larger contending coalitions. Some of

their struggles are reviewed below, but no single ruler or dynasty seems to

have been able to impose central control and effective administration over

a territorially large, multicenter polity for any appreciable time. It is also

possible that rulers of small polities actively sought associations with large

ones for reasons of their own, so we need not see hierarchical political

relationships as always imposed from the top down.

Like northern Yucatan in the early sixteenth century, the central and

southern Classic Maya Lowlands were politically fragmented, and individ-

ual polities probably had varied internal political arrangements. Uniting

them all was a shared (but by no means monolithic) Great Tradition of

art, architecture, literacy, religion, ritual, worldview, and etiquette, commu-

nicated among and maintained by mainly elites. Writing was a basic element

of this tradition, and very recent linguistic research (Houston et al., 2000)

strongly supports the idea that all Classic inscriptions were recorded in a

single prestige language ancestral to modern Ch’olti and Ch’orti.

Kings, Elites, and Commoners

Central to Classic Maya political organization was kingship, the institu-

tion that we know best because of the propensity of Maya archaeologists

to dig in royal places and because most monuments and texts were commis-

sioned by kings. From these texts and associated images epigraphers have

reconstructed local dynastic sequences. Some of these are only a few genera-

tions deep, but others extend back through more than 31 successive reigns

(with some breaks), as at Tikal, where the founding dynasty seems to have

been established sometime around the beginning of the third century AD

A Review of Maya War

87

[see Harrison (1999) for the most recent review]. Kings styled themselves

as K’uhul Ajaw, or ‘‘holy lords,’’ and inherited their positions (mostly in

the male line), but not according to rigid rules of primogeniture and, as

we shall see below, not without political dissention and even violence.

Houston and Stuart (1996) have recently summarized what we know

about Classic rulership. Kings were closely associated with divinities when

they lived. They took god-names and personified gods in rituals, and their

centers and dynasties were identified with particular sets of patron deities.

Kings commissioned images in which gods were thought to reside (at least

periodically), erected houses for deities, and in some sense personally

owned or cared for god-bundles. Kings also owned specific buildings, whose

construction they presumably oversaw. Destroying or defiling such power-

fully charged places or sacred objects of an enemy ruler was a major

symbolic goal of Late Classic war.

During their lives rulers were personally responsible for maintaining

cosmic order and the well-being of their realms and subjects, particularly

through communication with gods and royal ancestors, aided by wayob

[spiritual companions or coessences (see Houston and Stuart, 1989)]. Living

kings were highly sacred individuals, and when they died some of them

appear to have been apotheosized as gods. Rulership thus had a pronounced

theocratic dimension that reflected a basic postulate of Classic Maya culture:

the moral order, the political order, and the natural order were one. Inscrip-

tions reveal that some kings were ‘‘possessed’’ by other kings and carried

out rituals under the aegis of their patrons or overlords.

Maya kings initiated war and portrayed themselves as participating

personally in battles, presiding over ceremonies of political significance

such as heir designation, and visiting and entertaining one another, as

well as lesser elites, at impressive feasts. They certainly consumed and

redistributed elite status items that were widely exchanged among polities,

although it is unclear how much rulers were involved in their production

or acquisition. People of very high rank, including the sons of rulers, were

artists who engaged in the production of polychrome pottery and other

status objects. Powerful cultural influences emanated from royal courts,

setting aesthetic and behavioral standards for people of lower rank.

Kings were surrounded by lesser hereditary nobles, officials, and court-

iers, many of whom held titles and displayed carved benches, altars, and

fac¸ade sculpture in their own impressive households. Maya nobles below

the rank of king participated in very important rituals such as deity imper-

sonation. Like kings, these great lords had direct or indirect access to the

labor and taxes of commoners. Although the ajaw title was restricted to

kings and their very close relatives (Stuart and Houston, 1996, p. 295), it

is possible that all high nobles were (or claimed to be) descended from living

88

Webster

or dead kings. Both kings and subroyal nobles were probably polygynous,

although this is not certain.

Most people in any polity—probably upwards of 90%—were farmers

who produced the standard range of Mesoamerican crops on the agricultural

landscape. There is no direct evidence for the slaves described in the ethno-

historic literature. Upland swidden agriculture was a major cultivation strat-

egy, but more intensive forms of production involved terracing and wetland

drainage in some areas, although their contribution to the Maya economy

and even their chronology is debated (for a review see Fedick, 1996). In

any case, by the late eighth century overall population densities for large

regions were very high—at least 100 people per km

2

and, according to

some estimates, even higher (Culbert and Rice, 1990).

What We Do Not Know About the Classic Maya

Unfortunately art and inscriptions are mute about many important

features of Classic society central to a detailed understanding of warfare.

Maya kings and associated elites had leadership roles in negotiating foreign

relations, waging war, levying taxes or tribute, conducting rituals, and initiat-

ing royal building projects. We know almost nothing, however, about their

more fundamental leadership roles. My own suspicion is that Maya rulers

and elites had few managerial functions in terms of the all-important subsis-

tence economy, apart from extracting that proportion of it necessary to

underwrite their own activities. I also believe that the Classic Maya lacked

anything we might consider well-developed bureaucracies, but other Maya-

nists would disagree.

The most important things we do not know are how kings and elites

related to commoners and how people of any rank asserted claims to the

agricultural landscape. If effective commoner organization existed only at

the nuclear or extended family household level and lacked kin connections

with elites, most people must have been attached as clients to royal or

noble families and were comparatively powerless to resist their decisions.

This was the system in Hawai’i (Webster, 1998). In these circumstances

ordinary people might, however, have had considerable ability to move

about the landscape and attach themselves opportunistically to specific

elites or even polities precisely because they lacked local, corporate organi-

zation.

Alternatively, commoner households might have been organized into

larger corporate lineages, with their own resources and communities and

with kin attachments to elite leaders, along the lines of the postconquest

cah reviewed above or the Mexica calpulli (Hopkins, 1988; Sanders, 1989,

A Review of Maya War

89

1992; McAnany, 1995). Such lineages comprised natural political factions.

Although I do not have space to develop the theme, I think that the ‘‘house

society’’ concept propounded by Le´vi-Strauss has considerable utility here

(for a review see Carsten and Hugh-Jones, 1995).

High-born individuals would have formed a kind of elite network with

responsibilities to their lesser kinspeople, but also its own collective elite

self-interest. Common people in this case would have been more tied to

specific parts of the landscape, and hence more vulnerable to political

control, but also more capable of resisting royal demands and competing

with other similarly constituted factions. These two models cloud the issues

of to whom Maya divine kings were responsible and over whom they had

some sort of jurisdiction. Were such relations defined in territorial or kinship

terms? Did kings have impeded or unimpeded rights over the labor and

products of commoners? We simply do not know.

Even this short review shows that the Classic Maya differed in many

important ways from the Contact period Maya. Those differences most

germane to the issue of war include much stronger Classic political central-

ization, more powerful royal institutions, larger, more numerous, and more

closely packed polities, and much higher population densities.

Classic Maya War as History

Uniquely among New World peoples, the Classic Maya created a

logosyllabic writing system so sophisticated that by the eighth century AD

it could accurately replicate speech. No readable codices (screen-fold, bark-

paper books) of the period have survived, although archaeologists have

recovered fragments of several, but many artistic representations of them

are known. Fortunately, thousands of hieroglyphic inscriptions were more

durably carved, modeled, or painted on monumental altars, stelae, thrones,

building fac¸ades, lintels, and walls, tomb chambers, ceramic vessels, and

objects of bone and wood, forming an invaluable resource for epigraphers.

Until the late 1950s inscriptions could not be deciphered, and the conven-

tional wisdom among Mayanists, as Morley’s quote shows, was that they

referred mainly to calendrical, astronomical, ritual, and religious themes.

Compounding the problem was that there is a great deal of regional varia-

tion in Maya texts and the art which accompanies them. Copa´n’s many

inscriptions, which contributed so powerfully to early concepts of the Classic

Maya, are associated with few overt references to war.

Effective decipherment of hieroglyphs began only in the late 1950s

(Proskouriakoff, 1961) and, along with associated archaeological discover-

ies such as imposing royal tombs (Ruz, 1973), revealed that the Classic

90

Webster

Maya had dynasties of hereditary kings, that centers were royal capitals,

and that warfare was commonplace. Since about 1980 a veritable flood of

new data has emerged. As Schele and Miller (1986, pp. 14–15) state,

‘‘Among the most common events recorded on Maya monuments are war

and capture. . . . Warfare . . . gave rise to more varied depictions than

any other theme.’’ Epigraphic studies are now driving our understanding

of Maya war more than archaeological research—a development with both

good and bad consequences.

Inscriptions, coupled with iconography and highly accurate Long Count

dates, provide us with a sort of warfare history based on the emblem glyphs

associated with the rulers of contending centers, names of kings, noble

warriors, captives, and other participants in conflicts or their ritual sequels,

and information about associated behaviors such as tribute presentation.

Remarkable insights are being derived from this record, and when I first

started studying Maya war I never imagined that we would ever possess

anything like it.

Before examining this historical trove, however, we should admit some

of its current limitations. First, all known inscriptions referring to war were

written only after the sixth century AD. Here I mean dated inscriptions that

refer to roughly contemporaneous events. Some wars are known through

retrospective inscriptions; for example, one of the earliest securely docu-

mented Classic Maya wars occurred between Tikal and Caracol in AD 562

but is first mentioned in a Caracol inscription made 70 years later. Such

deeply retrospective texts obviously present their own problems of interpre-

tation. The initial two and a half centuries of the Classic period are thus

still prehistoric with regard to conflict, although there are early artistic

depictions of sacrificial victims and other war-related images (see Dixon,

1982). How to explain this rather sudden enthusiasm for explicit war state-

ments is an important issue briefly addressed below.

Second, inscriptions of all kinds are short and caption-like, so there are

no narratives comparable, say, to the Iliad. Third, war-related inscriptions

almost always present the perspectives and intentions of the royal (and

occasionally other high ranking) individuals who commissioned them (al-

though, interestingly, not always of the winners). Recorded events must

thus be understood in the context of their elite motivations, which are not

always clear, and of course are susceptible to self-serving distortion or

at least omission. For example, confrontations between two centers are

sometimes only recorded at one of them, usually the ostensible victor.

Thus the sacrifice of the thirteenth ruler of Copa´n at Quirigua´ in AD 738,

probably during a dynastic squabble, is recorded only at Quirigua´. Such

inconsistencies clearly show elite concern with putting the best face on

military or political reverses.

A Review of Maya War

91

A related difficulty is that this top-down perspective does not tell us

directly about the motives, purposes, and functions of war, which leaders

were actually present in the field, or any details concerning the numbers

of combatants, who they were, and how they were recruited, where battles

took place, how contingents were organized, or what kinds of strategies

and tactics were employed. Some war-related events appear to take place in

supernatural contexts and might have had mainly mythical or metaphorical

significance (Stuart, 1995, p. 300).

There is also much regional variation in war texts. They are abundant

at some centers, such as Yaxchila´n, Piedras Negras, and Caracol, sparse

elsewhere, as at Copa´n, and absent at others. Classic texts of any kind are

comparatively rare or lacking entirely in sites in the northern Lowlands.

Compelling evidence for war in the form of fortifications, as at Becan, or

destruction episodes, as at Yaxuna´, must consequently be interpreted in

the absence of texts, or even much art. Finally, some war-related glyphs

remain undeciphered, others are poorly understood, and inscriptions are

often damaged or incomplete, leading to premature claims and disputes.

For example, Schele and Freidel (1990) postulated an extremely important

war early war between Tikal and Uaxactun in AD 378, while Stuart (1995,

pp. 326) maintains that the evidence they cite has no such implication.

Bearing in mind these lacunae and uncertainties, let us turn to some

glyphic expressions of war, relying heavily on David Stuart’s (1995, pp.

291–329) summary, which I think is the best available and which itself

benefits from the work of many other scholars.

War-Related Glyphs

Stuart notes, interestingly, that there is no glyph that literally means

‘‘to wage war.’’ About a dozen others, however, have direct war-related

meanings or commonly occur as parts of longer war statements; these are

rendered phonetically in the list below [Stuart (1995, p. 311) is adamant

that meanings of glyphs must be derived from their phonetic values, and

not from interpretations of the pictorial elements that make them up]. The

orthography of the listed terms varies according to specific epigraphers and

date of publication; here I follow Stuart. Stephen Houston offered his own

comments while reading a draft of this paper, and I have included them

alongside Stuart’s interpretations.

(1) Chuk:

‘‘To capture’’ or ‘‘to tie up’’; the most common

glyph (or, according to Stephen Houston, ‘‘to

grab’’ or ‘‘to seize’’).

92

Webster

(2) Bate’el:

‘‘Warrior’’ (Houston thinks that this is a prob-

lematical interpretation).

(3) Bak, or baak:

‘‘Prisoner’’ or ‘‘captive’’; often used in a posses-

sive form, as ‘‘his captive,’’ with numbers spec-

ified.

(4) Ch’ak:

‘‘To chop’’; probably referring to sacrifice after

war events.

(5) Pul:

‘‘To burn’’; this glyph is often found in connec-

tion with captives and might sometimes also re-

fer to particular places that were burned (delib-

erate destruction?).

(6) Tok’ pakal:

‘‘Flint shield’’; a term that somehow refers gen-

erally to the essence of war as a royal endeavor

and/or an object used in war-related ceremonies

(Houston thinks that this glyph has a more spe-

cific reference).

(7) Hub:

To ‘‘fall,’’ ‘‘collapse,’’ or ‘‘fail’’ (as in the failure

of a military campaign).

(8) Patan:

‘‘Tribute’’ or ‘‘service/work’’; this is a fairly rare

term often attached to numbers and sometimes

seems to refer to tribute exacted or being of-

fered after war events.

(9) Ikats:

‘‘Burden’’ or ‘‘load’’; sometimes used with ex-

pressions for ‘‘payment,’’ as possibly in payment

of tribute. Sometimes used in the possessed

form (yikats).

(10) Yubte:

A very rare classical Yucatecan glyph for ‘‘trib-

ute mantle’’ identified on a Pete´n polychrome

vessel by Stephen Houston.

To this list we should add two others. Sajal is one of the few apparently

hereditary titles we know for Classic Maya officials or courtiers who are

in some way subordinates of kings. Particularly common on the western

peripheries of the Maya Lowlands, the title is usually held by men, and royal

inscriptions sometimes associate individual kings with numerous sajals, as

at Yaxchila´n. Sajals commonly appear in war statements (e.g., as captives

or captors) and are often assumed to have had military functions (Stuart,

1993, pp. 330–331).

Perhaps most significant of all is the frequently occurring but controver-

sial ‘‘shell-star’’ or ‘‘earth-star’’ glyph, usually taken to indicate a war event

of unusual consequence, as in Caracol’s apparent conquest of Tikal in AD

562 (the earliest known example). Some epigraphers (Schele and Freidel,

1990; Schele and Matthews, 1991) think that ‘‘earth-star’’ events were major

A Review of Maya War

93

territorial wars timed with regard to particular points in the cycle of the

planet Venus (often associated with war in Mesoamerica) and signaled the

defeat of one polity by another. Stuart cautions that we do not yet under-